Professional Documents

Culture Documents

RezaviStateShiasShiismSPH4 1

Uploaded by

Faisal Ali Haider LahotiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

RezaviStateShiasShiismSPH4 1

Uploaded by

Faisal Ali Haider LahotiCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/325458630

The state, Shia‘s and Shi‘ism in medieval India

Article in Studies in People’s History · June 2017

DOI: 10.1177/2348448917693738

CITATIONS READS

3 2,745

1 author:

Nadeem Rezavi

Aligarh Muslim University

20 PUBLICATIONS 28 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Nadeem Rezavi on 22 August 2019.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

The state, Shia‘s and

Shi‘ism in medieval India

Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi

Professor of History, Aligarh Muslim University

The major schism in the history of Islam in India, as in some other countries with Muslim popu-

lations, has been between Sunnism and Shi‘ism. Since Shias have formed a minority in India,

it is of some interest to trace how they were treated by the Sunni majority (and the state) and

follow the progress of theological controversies that ensued between the two sects. The present

paper reconstructs the story of the co-existence and disputation between the two sects in India

from about the thirteenth century to the early nineteenth century, when the onset of colonialism

created an entirely changed political and cultural atmosphere.

Keywords: Shi‘ism, Sunnis, Akhbårðs, Us[ølðs, Nørullåh Shøshtarð, Shåh Walðullåh, Awadh

Since its very early days schism has existed in Islam, and the two major sects,

the Sunni and the Shi‘a*, have had their contestations over beliefs and practices.

Further, since the beginning, the possession of political power or the lack of it, has

exercised a major influence on the playing out of these differences. The majoritarian

Sunni Islam has flourished under the patronage of various regimes like those of the

‘Ummayids, ‘Abbåsids and the Ottomans. The Shi‘a sects, notably the is]nå‘asharð

(the Twelvers) and the Ismå‘ilðs, flourished when political support was provided

to them under the Fåt]imids and the S[afavids. Developments elsewhere also show

that political changes have kept on influencing the religious scene.

Indeed, one finds that the Shi‘a response to the challenges thrown by Sunni ortho-

doxy used to be quite muted at moments when they lacked political patronage. On

the other hand, during the periods when they were free from political pressure, or had

the active support of the government, their response tended to be quite bold and vehe-

ment. We also see that Shi‘a activism became quite strong at points when a spirit of

tolerance prevailed in Mughal India, and Shi‘aism received even official patronage

in some principalities of the time. On the other hand, there has been practically no

Sunni voice raised in Iran ever since the onset of the Shi‘ite S[afavid dynasty—a

period of 400.

After the Arabs conquered Sind and Multan (712–14), Shi‘ite influence first

manifested itself under the designation of Qaråmit]a (Carmathians), who owed

*Shð‘a means ‘party, faction’, so, properly speaking, the designation should be Shð‘ð,‘people of the

party or faction’. But usage has made Shð‘a the common appellation at least in India for members of

the sect.

Studies in People’s History, 4, 1 (2017): 32–45

SAGE Los Angeles/London/New Delhi/Singapore/Washington DC/Melbourne

DOI: 10.1177/2348448917693738

The state, Shia‘s and Shi‘ism in medieval India / 33

allegiance to the Fat]imids of Egypt (909–1171). In the tenth century, under their

leader Jalam ibn Shaibån, they seized Multan where they destroyed the famous

Sun-temple, killing its priests, and closed down the town’s old mosque, as a foun-

dation of the hated Umayyids. Their rule was put an end to by Ma°mød of Ghazni

(999–1030), with his usual cruelties, which included lying waste the Qarmat]ian

mosque1

We cease to hear of any Shi‘ite sects until we come to the account of the murder

of Sultan Mu‘izzuddðn of Ghor in 1206 on his way to Ghazni from India in 1206

at the ‘hands of a fidåð (devotee) of the heretics (mulåh[ida)’, a reference obvi-

ously to an Ismå‘ilð agent.2 A curious incident occurred at Delhi during the reign

of Sultan Raziyya (1236–40), when, according to a contemporary account, a

crowd of ‘Carmathians and heretics’, to the number of a thousand gathered under

a ‘pretended scholar Nør Turk’, on 5 March 1237, to attack the Madrasa-i Mu‘izzð

at Delhi, attacking the conventional Sunnðs as Nås[ibðs/(enemies of ‘Ali) and

murjðs (unfaithful). They were duly suppressed.3 The curious fact is that Nør Turk

is mentioned with much respect in Shaikh Niz]åmuddðn’s conversations early in

the next century, and he seems to have retired peaceably to Mecca.4

It is possible that by now the ‘twelver’ Shiå‘s had also made their appearance,

first, amongst the Iranian and Central Asia immigrants who flocked to Delhi. Ibn

Battøta, who visited Delhi in the reign of Mu°mamad Tughluq (1324–51) reports

that Sharðf Abø Ghurra of Najaf coming to India spent eight years in Daulatabåd,

with a royal grant of two villages, and then went to Delhi where he received a large

amount from the Sultan. He dying within a short while of receiving this gift, the

amount was distributed ‘in alms to a community of Shi‘ites from the Hijåz and

al-Iråq living in Delhi’.5 There was similarly a settlement of Rafiz[ðs (pejorative

for Shi‘as) at Quilon in Kerala, where they ‘proclaim’ their affiliation openly’.6

The apparently peaceable existence of Shias must have been greatly disturbed at

least in the Delhi Sultanate by the measures of persecution adopted by Sultan Fðroz

Shåh (1351–88). His edict reportedly inscribed on the Firozshah Kotla Mosque,

recites that ‘men of the Shð‘ð faith (Shð‘ð-mazhabån), who are called Råfðzðs used

to invite people to join the Rðfz[ and Shð‘ð faith, had written tracts and books on this

faith, and engaged in the profession of teaching and instructing (people) in the faith’.

He accused them of reviling ‘Åyisha, wife of the Prophet, and the entire body of

1

Shams al-Dðn Maqdðsð, A°san al-Taqåsðm fð Ma‘årifat al - ‘Aqålðm, 2nd ed., Lieden, 1967, pp. 281,

485; Edward C. Sachau, tr., Alberuni’s India, London, 1910, Vol. I, pp. 116–17.

2

Minhåj Siråj, T]abaqåt-i Nås[irð, ed. Nassau Lees, Calcutta, 1864, Vol. I, p. 403.

3

Ibid., Vol. I, p. 461.

4

Amðr ¡asan Sijzð, Fawå’idu’l Fawåd, ed. Muhammad Latif Malik, Lahore, 1966, pp. 334–35:

conversation, 9 October 1318. Niz]amuddðn here specifically denied the allegations made of Shi‘ite

heresy agsinst Nør Turk in the T]abaqåt-i Nasðrð, and claimed that nås[ibð meant råfiz[ð or Shi‘a, an epithet

which Nør Turk himself used against the conventional theologians.

5

H.A.R. Gibb, tr., Travels of Ibn Battuta, Indian reprint, New Delhi, 1993, Vol. I, p. 263.

6

C.F. Beckingham, tr., The Travels of Ibn Battuta, London, 1994, Vol. IV, p. 817.

Studies in People’s History, 4, 1 (2017): 32–45

34 / Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi

søfðs, and calling the Qurån ‘Us]mån’s additions (mul°iqåt-i ‘Us]månð). He claimed

that he had seized all such Shð‘a preachers, executed the rabid ones (ghålðån), and

chastised the others, while burning their books—‘so that by the grace of God, the

mischief of this sect was entirely suppressed’.7 The anonymous Sðrat-i Fðrozshåhð

(completed, 1370–71) goes on to refer to one Imåm Abø Shakør Sålamð and repro-

duces his list of the beliefs of the Shi‘a sect (Farq-i Råfðziya), each of which in his

opinion amounted to kufr (infidelity). The long list may deserve scrutiny from the

point of view of what the critic’s sources were. Superficially, it shows the usual

polemicist’s desire to attribute extreme view to the opponent, for example, that

‘Alð was an emanation of God, or couple two divergent positions together, for

example, practice of temporary marriage (mut‘a) with rejection of instant divorce,

even if pronounced thrice by the husband.8 A polemical text Siråjiyya against

the Shi‘as attributed to Jalål Makhdøm-i Jahånðån (1308–84) is preserved in the

Riza Library, Rampur.9

After the establishment of Mughal rule, there was initially little change as far

as the official attitude to Shi‘a theology was concerned. The tradition went that

Humåyøn dismissed the im[åm who had led prayers at the court for two years, when

he heard a person say that he had seen the im[åm in company with Shi‘as (ahl-i rifz[)

one day. Not only that, he held the two years’ prayers to stand cancelled, having

to be offered again!10 On the other hand, no act of persecution of Shi‘as by Båbur

(1526–30) or Humåyøn in the first phase of his reign (1526–40) is reported.

On Humåyøn’s return, from Iran, he brought with him a number of Iranian

soldiers and officers (then mostly Shi‘a).11 In the more open atmosphere that this

situation created, Saiyid Råjø bin Saiyid ¡åmid al-¡usaini al-Bukhårð proposed a

departure from the practice of taqðya (dissimulation) that Shi‘as had so far appar-

ently followed and exhorted them to openly declare their faith and busy themselves

in the pursuit of the mazhab-i °aq (the true path).12

During this period, a major churning in the Shi‘i exegesis was taking place. It

is true that this had actually started when the Buwaihids had ruled western Iran

and Iraq from the middle of the eleventh to the middle of the twelfth century. But

it got a new life with the establishment of Safavid rule in Iran during the sixteenth

7

Firuzshåh Tughluq, Futū°āt-i Fīrūzshāhi, ed. Abdur Rashid, Aligarh, 1954, p. 6. The text of the

edict is partly summarised in the Sðrat-i Fðrozshåhð, facsimile ed. of Patna MS, 1999, pp. 117–22, so

that since the latter was compiled in 1370–71, the edict must have been issued at an earlier date.

8

Sðrat-i Fðrozshåhð, pp. 122–35. Its claim that the Shia sect was totally destroyed through Sultan

Firoz’s measures (p. 140) is, of course, likely to be an exaggeration.

9

On the author, see Muhammad Ghaus]ð Shattårð, Gulzår-i Abrår, ed. M. Zaki, Patna, 1994,

pp. 101–02, where, however, no work against the Shi‘as is attributed to him.

10

Rizqullah Mushtaqi, Wåqi’at-i Mushtåqi, ed. I.H. Siddiqui and W.H. Siddiqui, Rampur, 2002, p. 113.

11

See ‘Abdu’l Qådir Badåønð, Muntakhabu’tawārīkh, ed. Ahmad and Lees, Calcutta, 1864–1869,

Vol. I, p. 468, where a protest at this by a theologian before Humayan at Kabul is related.

12

Qåzð Nørullåh Shøshtarð, Majālisu’l Møminīn, Teheran, 1882, pp. 52, 230.

Studies in People’s History, 4, 1 (2017): 32–45

The state, Shia‘s and Shi‘ism in medieval India / 35

century. From the period of the Occultation of the Twelfth Im[åm in AD 873,13 up to

the establishment of Safavid rule in 1501, the majority of Shi‘a ‘ulamå had held that

the state-related functions could not be performed in the absence of the Imām. Only

the Imām could collect and distribute religious taxes, lead Friday congregational

prayers and order jihåd.14 Such literalist interpreters under the Buwaihids had

come to be known as akhbārī. This school of thought was further strengthened by

the beginning of the seventeenth century by Muhammad Amðn al-Astaråbådð (d.

1626–27) through his book al-Fawā’id al-Madaniyya.15 Another group of ‘ulamā,

led by Nøru’ddðn ‘Alð ibn ¡usain al-Karakð (d. 1534) and Mīr Dåmåd (d. 1631–32),

developed the us[ūlī fiqh. Al-Karakð’s theology was a response to the needs of Safavid

rulers to establish the Shi‘a faith on firm foundation. He emphasised the role of the

‘ālim as guardian of the Sharð’a and as successor of the Imām and gave authority

to the competent ‘ulamå to practise ijtihād (‘elaboration’). Al-Karakð claimed

that the mujtahid (jurisconsult) was the deputy (nā’ib) of the Hidden Imām.16

The us[ūlīs partially trusted human intellect, and applied Greek philosophical tools to

discover the will of the Hidden Imām. Since they insisted that laymen must follow

their rulings, they gradually assumed the position of a clergy. The akhbārīs, on the

other hand, forbade the use of rationalist tools both in kalām (study of the Divine

Word) and fiqh (jurisprudence) and depended only on the literal interpretation

of oral reports (akhbār) transmitted to them from the Imāms. The us[ūlīs con-

sidered the consensus of jurisconsults—ijmå‘—as a source of legal judgement and

divided the believers into two categories: the jurisconsults (mujtahid) and the laymen.

The latter were to follow the mujtahid in matters of law.17 In fact, under the Safavids,

al-Karaki in the very first year of the reign of Shåh Tahmåsp, had ordered the

appointment of a prayer leader in every town and village.18 Thus in Safavid Iran

the influence of the us[ūlī fiqh went on growing during this period.

13

The Shi‘a concept of occultation is extensively dealt with in Abdulazizv Sachedina, Islamic

Messianism, The Idea of Mahdi in Twelver Shi’ism, Albany, 1980.

14

Norman Calder, ‘The Structure of Authority in Imami Shi‘i Jurisprudence,’ PhD Disserta-

tion, SOAS, London, 1980, devotes his entire dissertation to this theme; Hamid Mavani, Religious

Authority and Political Thought in Twelver Shi’ism From Ali to Post-Khomeini, New York, 2013,

p. 130; also J.R.I. Cole, Roots of North Indian Shi’ism in Iran and Iraq: Religion and State in Awadh,

1722-1856, Delhi, 1989, p. 5.

15

Hossein Modarressi, ‘Rationalism and Traditionalism in Shi‘i Jurisprudence: A Preliminary Survey’,

Studia Islamica (59) (1984), pp. 141–58.

16

Albert Hourani, ‘From Jabal to Persia’, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies

49(1), In Honour of Ann K.S. Lambton (1986), pp. 133–40.

17

See Hossein Modarressi, ‘Rationalism and Traditionalism’, op. cit., pp.141–50; Andrew J.

Newman, ‘The Nature of Akhbari/Usuli Dispute in Late Safawid Iran. Part I: ‘Abdullåh al-Samāhiji’s

Munyal al-Mumārisðn’, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 55(1) (1992), pp. 22–51;

idem, ‘The Nature of Akhbari/Usuli Dispute in Late Safawid Iran. Part 2: The Conflict Reassessed’,

Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 55(2) (1992), pp. 250–61.

18

Said Amir Arjomand, The Shadow of God and the Hidden Imam: Religion, Political Order, and

Societal Change in Shi’ite Iran from the Beginning to 1890, Chicago, 1984, pp. 133–34.

Studies in People’s History, 4, 1 (2017): 32–45

36 / Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi

The Mughal Empire too could not remain untouched by what was happening in

Iran. Since the establishment of the Mughal rule, there had been friendly relations

between them and the Safavids. We know that Humåyøn could get back his lost

throne only with the help of the Persians, and thus with his return, there began a

steady influx of the Iranians into India. Large number of Iranian Shi‘a emigrants

came to India during Akbar’s reign as well. Amongst these were scholars, many

of them rationalists, like the famous scientist Fat°ullåh Shðråzð, ¡akðm ‘Abø’l

Fat° Gðlånð, ¡akim Humåm, ¡akðm Lut]fullah and ¡akðm ‘Alð, the last becoming

Akbar’s favourite physician.

In the initial stages, however, even Akbar’s reign saw a few possible instances

of bigotry and possibly persecution. In 1566–67 in an incident decried even by

Badåønð, no friend of Shi‘as, the body of Mir Murtuz[å Shðråzð, a native of Iran

who had recently died, was transferred to a different place from his original grave

near that of Amðr Khusrau, on the allegation that he was a Shi‘a.19 In 1569–70, an

official of Shi‘a beliefs, Mir Muqðm, was executed on Akbar’s orders, but on the

basis of a complex case in which he had got three or four Sunni muftðs murdered

in Kashmir.20 Shaikh ‘Addu’n Nabð, the Chief S[adr of Akbar, was accused, around

1578, by Makhdømu’l Mulk, of having unjustly imprisoned and executed Mðr

¡absh on the charge of being a Shia (ba-tuhmat-i rifz[[).21

This period also witnessed the production of a large number of Sunni polemi-

cal works. For example, Makhdømu’l Mulk ‘Abdullåh Sultånpørð himself wrote

Minhāj al-dīn wa Mi’rāj al-Muslimīn. In 1579–80 Mirzå Makhdøm Sharðfð wrote

al-Nawāqiz fi’l radd ‘alā’l rawāfiz in Baghdad which was soon brought and cir-

culated in India. The al-Sawāiq al-Muhriqafi’l radd ‘alāl rafz wa’l zandaqa of Ibn

Hajar al-Haithamð (d. 1566–67) was also in circulation. Another such work which

was becoming quite popular amongst the Sunnis was that of Fazlullåh Ruzbihan,

who in his Ibt]āl-i nahj al-bāt]il wa ih[māl kashf al-‘āt]il (1503) sought to prove that

the Shi‘a were almost infidels.

A shift seems to have occurred with the initiation of the ‘ibādatkhāna debates

in 1575,22 in which owing to their mutual jealousies, the Emperor began to lose his

confidence in the orthodox theologians. In such a situation among other critics of

the orthodox, Mullå Yazdð a recent arrival from Iran, is said to have begun openly

to revile the first three Caliphs, and denounce as infidels the great men of the faith

and their progeny, while he strove to bring into contempt the Sunnðs (ahl-i sunnat

o jamå‘at) and prove every belief other than that of the Shi‘a faith (mazhab) to be

19

Badåønð, Muntakhabu’t Tawårðkh, Vol. III, p. 99.

20

Ibid., Vol. II, pp. 124–25.

21

Ibid., Vol. II, p. 255.

22

S.A.A. Rizvi, Religious and Intellectual History of the Muslims in Akbar’s Reign, With Special

Reference to Abu’l Fazl (1556-1605), New Delhi, 1975, pp. 125–28; For the concept and purpose of the

‘ibādat khāna see S Ali Nadeem Rezavi, ‘Religious Disputations and Imperial Ideology: The Purpose

and Location of Akbar’s Ibadat khana’, Studies in History 24(2) (2008), pp. 195–209.

Studies in People’s History, 4, 1 (2017): 32–45

The state, Shia‘s and Shi‘ism in medieval India / 37

a deviation and an error.23 It is, however, to be borne in mind that there is no proof

that Akbar was drawn towards Shi‘ism, and Mullå Yazdð himself was to lose his life

in 1581 when he supported the rebel cause against Akbar. In 1579, the leading Sunnð

theologians themselves issued a ma°z[ar or declaration entitling Akbar to interpret

the Muslim law with certain limitations.24 This was not a sufficient concession to

Akbar’s quest for authority, but if he turned away from the theologians, it was not

to enter the Shi‘a camp, but to strike a new path under the umbrella of Pantheism.25

From 1581 Akbar initiated the policy based on the principle of Sul°-i kul (abso-

lute peace): a policy which tried to maintain equidistance between various religions

and tolerance of all.26 The author of Dabistān-i Mazāhib insightfully remarks that

this policy of religious tolerance reveals a high degree of political ‘foresight’ and

was aimed at accommodating diverse religious groups.27 Fr. Monserrate, a Jesuit

priest who visited the court of Akbar between 1580 and 1582, and also took part

in the disputations with Muslim scholars in the presence of Akbar, had a very

insightful remark to make:

He [Akbar] cared little that in allowing everyone to follow his own religion he

was in reality violating all religions.28

What is often not fully taken into account is the possibility that Akbar in his

espousal of S[ul°-i Kul was also influenced by what was happening in Iran. In

Safavid Iran in its first century under Shah Ismå‘il (1501–24), Tahmåsp (1524–76)

and ‘Abbås I (1587–1629) not only was there a suppression of Sunnism (all mosques

were called upon to include execration of the first three Caliphs in prayers), but there

was also a forcible suppression of sufic schools as well as of pre-Safavid sects that

had accepted the Shi‘ite fold, with executions of their leaders. The Iranian scholars

who flocked to Akbar’s court—a few of whom we have just mentioned—partly

came because of expectation of generous patronage, but partly also because of the

increasing intolerance in Iran. A letter survives that Akbar wrote in 1589 to the

leader of the Nuqtavi sect in Iran, S[afðuddðn A°mad Kåshð inviting him to come to

India, saying how he had already received one disciple of his and was expecting to

23

Badåønð, op.cit., Vol. II, p. 259.

24

The text with names of signatories is given in Niz]åmuddðn Ahmad, T]abaqat-i Akbarð, ed. B. De,

Calcutta, 1927, Vol. II, pp. 344–46.

25

Cf. Shireen Moosvi, ‘The Road to Sulh-i Kul: Akbar’s Alienation from Theological Islam’, in

Religion in Indian History, ed. Irfan Habib, New Delhi, 2007, pp. 167–76.

26

M. Athar Ali, ‘Sulh-i Kul and the Religious Ideas of Akbar’, in Mughal India: Studies in Polity,

Ideas, Society and Culture, New Delhi, 2006, pp. 158–72.

27

Kaikhusrau Isfandyån, Dabistān-iMazāhib, ed. Ra°ðmzåda Malik, Tehran, AH 1362 (solar),

Vol. I, p. 314.

28

Fr. Monserrate, Commentary of Father Monserrate S.J. on His Journey to the Court of Akbar, tr.

J.S. Hoyland, annotated by S. N. Banerjee, Cuttack, 1922, p. 142.

Studies in People’s History, 4, 1 (2017): 32–45

38 / Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi

welcome yet another.29 This divine, however, remained in Iran and was executed

by ‘Abbås I, in the slaughter of Nuqtavðs that he carried out in instalments.30 How

much Akbar was affected by this is shown by a long passage in the letter he sent to

Abbås I in November 1594. After discoursing on political matters, Akbar refers to

the disturbing news of persecution that kept arriving through emigrants from Iran.

The result had been that ‘in the land of Iran there has been a great reduction in the

number of experienced and farsighted wise men’. He points to the large numbers

of killings having taken place there and calls upon ‘Abbås to follow the principle of

S[ul°-i Kul. He advances two reasons for it: first, God sets the example by favour-

ing all people of whatever religion through his natural bounties. And, secondly, if

it is thought that some people hold wrong religious views which will affect them

adversely in afterlife, they are to be pitied, rather than to be persecuted!31

It could be argued that behind the slogan of Sul°-i Kul Akbar and Abø’l Faz[l

were furthering the patronage of rational sciences at the expense of orthodox

Muslim theology.32 We have the testimony (though admittedly late) of Åzåd

Bilgråmð that it was Fat°ullåh Shðråzð at Akbar’s court, who introduced the works

of Iranian rationalist thinkers like Muh[aqqiq Dawwånð, Mðr S[adruddðn, Mðr

Ghiyås]uddðn Mans[ør and Mirzå Jån in India.33 Abu’l Faz[l tells us that under

Akbar the rational sciences like mathematics, agriculture, household manage-

ment, rules of governance, medicine, etc., were added to the educational curricu-

lum.34 There was a stress on ‘aql (reason) which was to be given precedence over

traditionalism (taqlīd).35

If space was thus opened for reason, it also became open for Shi‘ism. A scholar

at the court, Mullå Ahmad Tattavð, ‘unlike the generality of Shi‘a mujtahids did not

observe taqiya (dissimulation)’. In 1587–88 hot words ensued between him and a

Sunnð, Mirzå Faulåd, at the house of ¡akðm Abu’l Fat° at Lahore, and the Mirza

then killed him, for which offence the murderer was publicly paraded and executed.36

29

This letter has been published in Khaliq Ahmad Nizami, Akbar and Religion, Delhi, 1989,

pp. 379–80. The date is given as 8 Āzur 94: the figure of the Ilåhð year 94 must be a mistake for 34,

and the date should then correspond to 30 November 1589.

30

Cf. S.A. Arjomand, The Shadow of God and the Hidden Imam, Chicago, 1984, pp. 198–99. Also

Kaikhusrau Isfandyår, Dabistan-i Mazåhib, op. cit., pp. 276–77.

31

The text of this letter is reproduced in Abu’l Fazl, Akbarnåma, Calcutta, 1864–69, Vol. III,

pp. 659–60 (for the passage of it discussed by us). H. Beveridege’s, tr., Akbar Nåma, Bib. Ind., Calcutta,

1897–1921, Vol. III, pp. 1011–13, misses important nuances in the passage.

32

See Irfan Habib, ‘Two Indian Theorists of the State’, in Mind Over Matter: Essays on Mentalities

in Medieval India, ed. D.N. Jha and Eugenia Vanina, New Delhi, 2009, pp. 37–38.

33

Mðr Ghulåm ‘Alð Åzåd Bilgråmð, Ma’ās]ir al-Kirām, Agra, 1910, pp. 236–37. The famous S[adraddðn

(Mullå S[adrå) (1571–1640) could have hardly been known to Fathullåh Shðråzð.

34

Abø’l Faz[l, Ᾱ’īn-i Akbarð, ed. H. Blochmann, Calcutta, 1872, Vol. I, pp. 201–02.

35

Ibid., Vol. II, p. 229. See also Badåønð, op. cit., Vol. II, p. 306 on subjects favoured at the court.

36

Mu‘tamid Khån, Iqbålnåma-i Jahångðrð, Nawal Kishor, Lucknow, 1870, Vol. II, pp. 407–08, for

the most detailed account. See also Badåønð, Muntakhabu’t Tawårðkh, op. cit., Vol. II, pp. 364–65.

Studies in People’s History, 4, 1 (2017): 32–45

The state, Shia‘s and Shi‘ism in medieval India / 39

Qåz[ð Nørullåh Shushtarð, a Shi‘a scholar of some repute and a scion of a family

of theologians of Iran arrived in India, reaching Fathpur Sikri in or before 1585.

On arrival, he was introduced to Akbar by ¡akðm Abøl Fat° Gðlånð.37 Having been

a student of Maulånå ‘Abd al-Wå°id at Mashhad, who had taught him °adðs][, fiqh

and us[ūl-i fiqh, Qåz[ð Nørullåh appears to have been exposed to the us[ūlī doctrine

which had gained ground under the Safavids. It is fortunate that Badåønð has left to

us, perhaps, the earliest notice we have of him. It begins with the words, ‘although

he is of the Shð‘ð dispensation (maz]hab)’, showing that Nørullåh did not hide his

religious affiliation. These words are followed by a series of adjectives in praise of

his character. We are further told that when Akbar shifted his capital to Lahore in

1585, he appointed Nørullåh as qåzð of that city, in which office he showed great

probity, stamping out corruption among his underlings as well.38 Clearly, Qåzð

Nørullåh’s open Shi‘ite beliefs were no bar to his appointment to a post which was

of a quasi-religious character.

Badåønð also praises Nørullåh’s writings, especially his critique of Faiz[ð’s com-

mentary (tafsðr) on the Qurån. Perhaps by then his principal Shi‘ite works had not

seen the light: his major work Majålisu’l Mø’minðn (in Persian) was completed

only in 1602.39

Obviously taking advantage of the political atmosphere and the tolerant attitude

of the state, Qåz[ð Nørullåh seems to have assigned two tasks to himself. Firstly, he

came out openly against the observation of taqiya (dissimulation),40 and, secondly,

he took up the task of writing replies to the anti-Shi‘a polemical literature then

current in India.

Qåz[ð Nørullåh argued that taqiya was hampering the growth and propagation

of the Shia faith in India.41 His open stand was opposed by the Indian Akhbārīs,

who appear to have been then in a majority in India among the Shi‘as. Mðr Yøsuf

‘Ali Astaråbådð, an akhbārī of Agra, warned the Qåz[ð against such an approach.

The Qåz[ð’s reply gave not only arguments in his defence, but also provided

Badåønð adds that some time later, despite his grave being guarded, Ahmad Tattavi’s body was disin-

terred and burnt by Sunnis.

37

Badåønð, op. cit., Vol. III, p. 137. For a biography of Nørullåh Shustari see Saiyyid Sibtul Hasan,

Tazkira-i Majīd (Urdu) 5th ed, Karachi, 1984, S.A.A. Rizvi, A Socio-Intellectual History of Isna ‘Ashari

Shi’is in India (2 vols), Delhi, 1986, Vol. I, pp. 346–47, also Wayn Rollen Husted, ‘Shahðd-i S]ålis]

Qåzð Nørullåh Shushtari: A Historical Figure in Shi‘ite Piety’, PhD thesis submitted at University of

Wisconsin-Madison, 1992 (mimeographed)

38

Badåønð, op. cit., Vol. III, pp. 137–38. Niz]åmuddðn Ahmad, T]abaqåt-i Akbarð, op. cit., Vol. II,

p. 468, praises Nørullåh’s ‘honesty and probity and learning and capacity in dispensing justice’ as the

qåz[ð of Lahore.

39

Cf. C.A. Storey, Persian Literature: A Biobibliographical Survey, I (Part 2), London, 1953, p. 1129.

40

Hiding of one’s actual faith in the face of danger to life and property was deemed permissible

amongst the Shias.

41

Qåzð Nørullåh Shøshtarð, Majālis al-Mø’minīn, op.cit., pp. 2–3; Cf. Bakhtåwar Khan, Mirātu’l‘ālam,

ed. Sajida Alvi, Lahore, 1979, Vol. II, p. 439. See also Saiyyid Sibtul Hasan, op. cit.

Studies in People’s History, 4, 1 (2017): 32–45

40 / Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi

an indication of the akhbārī-us[ūlī schism which had now become established.

He wrote

Perhaps it is better for you to search the Shi’i houses in Agra and take away

any books on the Shi‘i faith and burn them…I believe that there is a just ruler

in India, and there is no justification for performing taqiya. In any case it is

not imperative for men like me who believe that death glorifies the faith of the

martyr. The shari‘a has indeed forbidden such persons to perform taqiya. Only

those who are not steadfast in their faith and do not care to strengthen it, should

have recourse to it.42

In yet another letter, this time sent to Mullå Qausi Shushtarð, the Qåz[ð wrote in a

qasīda:

Blessed be the Emperor whose patronage in Hind

Has not made my faith dependent on taqiya!43

In another of his letters which survives he gives his views on ijtihād and mujtahid:

The Shi’i mujtahidīn (jurisconsults), who draw upon the knowledge of Prophet

Muhammad and Im[åm ‘Alð, are inspired by their Imāms when forming ijmå‘

and can differ only in their respective understanding of the Imåms’ rulings.44

Hinting towards his second task while performing his first, Qåz[ð Nørullåh in yet

another letter writes:

I came to the conclusion that in India, taqðya was a great calamity: It would

expel our children from the Imāmiyya faith and make them embrace the false

Ash‘arð or Maturidi faiths. Reinforced by the kindness and bounty of the

Sultan, I threw away the scarf of taqðya from my shoulders and, taking with me

an army of arguments, I plunged myself into jihåd against the scholars (‘ulamå)

of this country.45

In 1587 Qåz[ð Nørullåh wrote his Mas[ā’ib un Nawās[ib which was a reply to Mirzå

Makhdøm Sharðf’s al-Nawāqiz. From the Qåz[ð’s letters it is clear that this defence

was undertaken in view of Mullå Mu°ammad Amðn’s interventions on the Sunni

42

Qåzð Nørullåh Shushtarð, al-Sawārim al-Mu°riqa, Buhar MS. 12, National Library, Kolkata,

Introduction.

43

Nawab ‘Inåyat Khån ‘Råsikh’, Bayāz[ Ms., Habibganj Collection, Maulana Azad Library, AMU,

Aligarh, f. 92(b). The volume contains a number of letters written by Qåzð Nørullåh Shushtarð.

44

Qåzð Nørullåh Shøshtarð, Majālis al-Mø’minīn, op.cit., pp. 230–31. Reproduced in Urdu translation

in Saiyyid Sibtul Hasan, Tazkira-i Majīd, op. cit., pp. 127–40.

45

Letter to Bahåuddðn Åmulð, Bayāz[, op. cit., ff. 95(a)–96(a).

Studies in People’s History, 4, 1 (2017): 32–45

The state, Shia‘s and Shi‘ism in medieval India / 41

side in Shi‘a-Sunni polemics raging in Kashmir during this period.46 The Mas[ā’ibu’n

Nawās[ib was the first major Shi‘a rejoinder in India to Sunni indictments.

Soon afterwards the Qåz[ð wrote al-Sawārim al-Mu°riqa which was a reply to

the Sawāiq al-Mu°riqa of Ibn Hajar al-Haithamð, and which, in his own words,

‘reduced the Sawāiq, which claimed to be lightning, to ashes’.47

All this would not have endeared him to the society in which he was function-

ing. Things were probably complicated further by the task he was entrusted with

in 1596, of carrying enquiries into tax-free grants in Agra province.48 In 1602

after the death of Abu’l Fazl, who appeared to have given him constant support,

one finds the Qåz[ð a dis-illussioned man. In one of his letters he describes the

country as ‘Hind’, the wife of Abø Sufyån who is said to have eaten the liver of

the Prophet’s uncle Hamza.49 At another place he compared it with a ‘doomed and

accursed old woman’.50

He, however, wrote I°qåqul ¡aq (in Arabic) in August 1605 (two months prior to

Akbar’s death) which was a comprehensive refutation of Ibt]āl-i Bāt]il of Faz[lu’llåh

Ruzbihan. This work is a compendium of the Shi‘a-Sunni controversies over the

Ash‘arite theories of Godhood, prophethood and imāmat. It also deals with the

problems of Quranic exegesis, °adðs] and fiqh.

During the same year (1587) that Qåz[ð Nørullåh wrote his Masā’ib un Nawāsib,

the theologian (later Naqshbandð) Shaikh A°mad Sirhindð, wrote a short anti-Shi‘ð

treatise, Radd-i Rawāfiz, in Persian.51

As far as the Shi‘as were concerned, Jahångðr’s accession in 1605 should have

meant no change in their situation. In his early years as emperor his closest adviser

seems to have been Amðru’l Umarå Sharðf, an Iranian. In his memoirs in its very

early pages Jahångðr praises his father Akbar’s policy of tolerance under which

‘Sunnis and Shias prayed in one mosque’.52 It is, then, an enigma why Qåz[ð Nørullåh

should have been executed by him in 1610. Jahångir is himself the first to mention

the incident—in a newly discovered record of his conversations. He denies in as

early a conversation as of 8 July 1610 that the punishment given to Qåz[ð Nørul-

låh had been out of any religious motive, though ‘the people now think of me as

an intolerant and rabid Sunnð’. He went on to assert that he was least interested

in converting any Shia to the Sunni sect.53 And yet the precise reason why Qåz[ð

Nørullåh was awarded capital punishment is neither given here by Jahångðr nor

46

For details, see S.A.A. Rizvi, History of Isna ‘asharis in India, op. cit., Vol. I. pp. 350–51.

47

Letter to Bahuddðn Åmuli, Bayāz[, op. cit., f. 96 (a).

48

Abu’l Fazl, Akbarnåma, op.cit., Vol. III, p. 713.

49

Bayāz, op.cit., f. 97 (b).

50

Ih[qāq-ul H[aq, Ms.Maulana Azad Central Library, AMU, Aligarh, ff. 4–5.

51

This has been usually published as an appendix to Sirhindi’s collection of letters, the Maktøbāt-i

Imām Rabbāni, Nawal Kishore, Lucknow, n.d.

52

Jahångðrnåma or Tuzuk-i Jahangðrð, ed. Saiyid Ahamd, Aligarh, 1864, p. 16.

53

‘Abdu’s Sattår (recorder), Majålis-i Jahångðrð, eds Asif Naushåhð and Muðn Niz]åmð, Tehran, 2006,

p. 78. Jahångðr went on to exclaim: ‘May God preserve all His servants from the disease of intolerance’!

Studies in People’s History, 4, 1 (2017): 32–45

42 / Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi

by the author of Zakhðratu’l Khawånðn, which provides the next mention, chrono-

logically, of the incident.54 It is natural that Qåz[ð Nørullåh should have come to be

revered as a great Shia martyr.

It is possible, whatever the real nature of the tragedy, that the action against Qåz[ð

Nørullåh did not herald the onset of any official campaign against Shias, as Jahångðr

himself speaking so soon after the event made clear in such plain words. One might

even say that action spoke louder than words, when the rabid critic of Shi‘ism, the

author of Radd-i Rawåfiz, was put in prison in 1619 for over a year, within a short

while of his inflammatory (first) volume of letters being set into circulation by him

in 1617. He was put into prison and then released but kept at the court to ensure his

good conduct.55 Irfan Habib notes that Vol. III of Ahmad Sirhindi’s letters written

during and after his imprisonment indicate that he had now had to adopt ‘a more

temperate language, and the Hindus and Shias are not abused’.56

A positive evidence of the public displays of Shi‘ite fervour, far from the

practice of taqiya, as far as the common people were concerned, is provided by

the eye-witness account of Ma°mød Balkhð, who arrived at Lahore on the first of

Mu°arram 1035ah (3 October 1625). The whole city was observing Mu°arram,

with tåzias taken out on the 10th, the shops closed and so much action and frenzy

that 50 Shi‘as and 25 Hindus lost their lives in the tumult.57

From a chapter on the Is]nå ‘Ashriya or Twelver Shi‘ism that the author of the

remarkable work on religions, the Dabistån-i Mazåhib (1653), provides, it would

seem that the Shi‘as in India yet belonged mainly to the Akhbårð tradition, since it

is with that school that the author was familiar with.58 It also does well to remind us

that Shi‘ism had found patronage in some of the Deccan courts: it holds the major

authority of the akhbårð school ‘during these times’ to be Mullå Mu°ammad Amðr

Astaråbådð, author of Fawa’id-i Madanð and the Dånishnåma-i Qut]bshåhð, written

during the reign of Mu°ammad Qulð Qut]bshåh (1611–25).59

Another interesting feature of the treatment of the Shia–Sunni question in the

Dabistån-i Maz[åhib is the record of disputation which allegedly took place between

the Sunnis and Shias before Akbar on a series of topics such as the question of

precedence between ‘Alð and Abø Bakr and ‘Umar; the cursing of the Prophet’s

companions; the tradition of ‘Umar denying the ailing Prophet’s wish for pen and

54

‘Qåzð Nørullåh, qåzð of the army, was a great champion of the imåmiya (Shi‘a) dispensation

(mazhab). For some cause, he was executed owing to the wrath of Jahångðr’ (Farid Bhakkarð, Zikhðratul

Khawånðn, ed. S. Moinul Haq, Karachi, 1970, Vol. II, p. 373).

55

Jahångðrnåma, op.cit., pp. 272–73, 308, 370.

56

Irfan Habib, ‘The Political Role of Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi and Shah Waliullah’, Proceedings of

Indian History Congress, 23rd session (Aligarh, 1960), Part I, pp. 209–23, quote on p. 215.

57

Ma°mød Balkhð, Ba°ru’l Asrår, ed. Riazul Islam, Karachi, 1980, pp. 7–10.

58

The chapter on Is]nå‘ashriya occupies in Dabistan-i Mazåhib, ed. Ra°ðm Razåzada Malik, op.

cit., Vol. I, pp. 244–53, of which the major part (pp. 247–54) is devoted to the Akhbårð school and its

rejection of ijtihåd.

59

Ibid., Vol. I, p. 227.

Studies in People’s History, 4, 1 (2017): 32–45

The state, Shia‘s and Shi‘ism in medieval India / 43

paper; the many marriages of ‘Alð, the question of fidak and the role of Abø Bakr

and ‘Umar in that issue; the judiciousness of ‘Alð, etc. What is interesting in these

confrontations and arguments is that the narrator (the author) appears to be neutral:

at times he depicts both the rival sides as becoming speechless or exasperated.60

Aurangzeb during his long reign (1659–1707) altered the religious policy of

his predecessors, and this affected Shi‘as as well. But, on the whole, his aversion

to Shi‘ism was confined to a play with titles and names. In 1688 when Faz[l ‘Alð,

son of Murshid Qulð Khån petitioned that ‘Fazl ‘Alð Khån’ be given to him as a

title, Aurangzeb amended it to Faz[l Qulð Khån, deleting ‘Alð. The historian who

records this recollected an incident where an ‘Indian person’ brought two of his

sons before the Emperor after they had memorised the Qurån. Their names turned

out to be ¡asan ‘Alð and H[usain ‘Alð. The Emperor exclaimed, ‘I and my mother

and father have been dedicated to ‘Alð (qurbån-i ‘Alð). But for Hindustanis where

is the appropriateness of such names—for purpose that they should fall into the

evil company of Shias (råfiz[[a), and so, leaving the right path, go astray’?61

On the other hand, Aurangzeb’s son Bahådur Shah (1707–12) became so inclined

towards Shi‘ism that in 1711 he ordered the title Was[ð (heir) to be added to the epi-

thets for ‘Alð in sermons in mosques, a measure that almost ignited riots provoked

by Sunni theologians at Lahore and other places, and had therefore to be modified.62

Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries the main text of refutation of the Shi‘i

positions appears to have been Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi’s Radd-i Rawāfiz[. During

the eighteenth century, when the Mughal empire entered its period of decline Shåh

Waliøllah Muh[addis Dehlavi translated this treatise (1731–32) into Arabic and

added his own preface to it. In his other writings as well he took up polemical issues

and tried to prove the superiority of Abø Bakr and ‘Umar over Us]mån and ‘Alð.63

He also argued that the true period of khilāfat-i khās[s[a was during the tenure of

only Abø Bakr and ‘Umar.64 He identified Islam with Sunnism and stated that the

Shi‘ite doctrine of the impeccability of Imāms (Imām-i ma’s[ūm) amounted to the

denial of the doctrine of the Prophet Muhammad as the seal of the prophets (khatm

al-mursalīn), and therefore made the Shias’ faith bātil (false).65

Further light on this issue is thrown by the contents of a letter written by Shah

Waliullah to the king, wazīr and nobles which has been reproduced by Rizvi in his book:

Strict orders should be issued in all Islamic towns (shahr-i Islåm) forbidding

religious ceremonies publicly practiced by Hindus (rusūm-i kufr) such as the

60

Ibid., Vol. I, pp. 288–91.

61

Såqð Musta‘idd Khån, Ma’as]ir-i ‘Alamgðrð, ed. Agha Ahmad Ali, Bib. Ind., Calcutta, 1873, p. 313.

62

This incident is fully described with references in W. Irvine, The Later Mughals, Indian reprint,

Delhi, 1995, Vol. I, pp. 130–31, with a long n., pp. 131–32.

63

S.A.A. Rizvi, Shah Waliullah and His Times, Canberra, 1980, op. cit., pp. 251, 256.

64

Ibid., p. 252.

65

Ibid., p. 229.

Studies in People’s History, 4, 1 (2017): 32–45

44 / Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi

performance of Holi and ritual bathing in the Ganges (raftan-i Ganga). On the

tenth of Mu°arram, the Shias (rawāfiz) should not be allowed to go beyond

the bounds of moderation, neither should they be rude nor repeat stupid things

[i.e., recite tabarra, or condemn the first three successors of the Prophet] in the

streets or bazars.66

This was followed by the writing of Tu°fa-i Is]nå ‘Ashariyya which was com-

pleted by Shah ‘Abdu’l ‘Azðz in 1789–90.67 Divided into 12 chapters—the same

number as the Shi‘i Imāms, the work aims at a comprehensive rebuttal of Shi‘a

beliefs and practices. In addition to the origin of the Shi‘a movement, and con-

cepts of divinity, prophethood and fiqh, it takes up themes of the kind set out in

the Dabistān-i Mazāhib.

In certain respects these were voices in the wilderness. The Mughal empire

had collapsed, and the Marathas, who were in control of Delhi, when the Tuh[fa

was completed, were hardly likely to be keen to take sides in the controversy.

The Shi‘a reply came in a similarly politically constructed sphere: the Awadh state,

whose rulers were Shias.

In 1775 Nawab Ās[af ud Daulah shifted his capital from Faizabad to Lucknow

and commenced the building of a number of Shi‘a religious structures like the

Ās[afð Imåmbåæa and the Jami’ Masjid there. He also invited a large number of

Shi’i‘ulamā to the Awadh court. Many distinguished Iranian-trained ‘ulamā were

employed and a number of seminaries were opened.68 It was during this time in

1781 that Sayyid Dildår ‘Alð (d. 1856), later known as Ghufrān Ma’āb, joined state

service, obtaining the title mujtahid al-‘as[r. As the chief theologian he crowned

Nawab Ghåziuddðn ¡aidar as the first ‘king’ of Awadh in 1819.69 Having studied

in the seminaries in Iraq and Iran, he was responsible for introducing Usūlð fiqh in

India on a permanent basis. (His very title showed his us[ølð affiliation.) His work

Asås-ul us[ūl heavily criticised Akhbārī traditions.70

An initial Shia response to Tu°fa-i Is[n[a ‘ashariyya of Shåh ‘Abdul ‘Azðz was

attempted by Mirzå Mu°ammad Akhbårð (d. 1816–17), but the most comprehensive

rebuttal came again from Dildår ‘Alð who wrote more than two dozen books, the

most important of which was ‘Imād al-Islām. He and his students wrote a series of

treatises in response to the Tu°fa, each of which was devoted to some individual

chapter of that book. Thus, we have Sawārim-i Ilāhiyāt (a refutation of the 6th

66

Ibid., p. 227.

67

S.A.A. Rizvi, Shah Abd al-Aziz: Puritanism, Sectarian Polemics and Jihad, Canberra, 1982.

68

J.R.I. Cole, Roots of North Indian Shi’ism in Iran and Iraq, op. cit., pp. 59–60. See also Madhu

Trivedi, The Making of Awadh Culture, Delhi, 2015, pp. 180–87.

69

Michael Fisher, A Clash of Cultures: Awadh, the British and the Mughals, New Delhi, 1988,

pp. 136–38; Sajjad Rizvi, ‘Faith Deployed for a New Shi’i Polity in India: The Theology of Sayyid

Dildar Ali Nasirabadi’, in The Shia in Modern South Asia: Religion, History and Politics, ed. Justin

Jones and Ali Usman Qasmi, Delhi, 2015, pp. 12–35.

70

Sajjad Rizvi, ‘Faith Deployed for a New Shi’i Polity in India,’ op. cit., pp. 12–35.

Studies in People’s History, 4, 1 (2017): 32–45

The state, Shia‘s and Shi‘ism in medieval India / 45

chapter of the Tu°fa); ¡usām al-Islām (a rebuttal of the 5th chapter); Khātima-i

Sawārim (against 7th chapter); Ih[yā al-Sunna (defence against 8th chapter) and

Risāla-i Zu’l fiqār (response to the 12th chapter).71

Whether Shåh ‘Abdu’l ‘Azðz’s critique really deserved the turning out of so much

heavy armour may well puzzle one. But apparently this was not still considered

enough: Sayyid ¡amid ¡usain (1830–88), a student of Dildar Ali, turned out 18

volumes under the title Abaqåt al-Anwår fð Imåmat Aimat al-At ]hår, rebutting not

only ‘Abdu’l ‘Aziz but also other Sunni criticisms of Shi‘ite positions. With this

visibly weighty work the story of the medieval debate may be taken to have closed.

71

S.A.A. Rizvi, Shah Abd al-Aziz, op.cit., p. 358; Sajjad Rizvi, ‘Faith Deployed for a New Shi’i

Polity in India,’ op.cit., p. 33.

Studies in People’s History, 4, 1 (2017): 32–45

View publication stats

You might also like

- Hasan-I-Sabbah: His Life and ThoughtFrom EverandHasan-I-Sabbah: His Life and ThoughtRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Orthodoxy and SyncretismDocument4 pagesOrthodoxy and SyncretismbpareecheraNo ratings yet

- Nasir Al-Din Tusi and His Socio-Political RoleDocument24 pagesNasir Al-Din Tusi and His Socio-Political Roleangurp2575No ratings yet

- 1-Religious Trends of The Mughal Age PDFDocument19 pages1-Religious Trends of The Mughal Age PDFJuragan TamvanNo ratings yet

- The Theology of Sayyid DIldar AliDocument19 pagesThe Theology of Sayyid DIldar Alithehealer7No ratings yet

- Ahlul Bayt Digital Islamic Library - Nasir Al-Din Tusi and His Socio-Political Role in The Thirteenth CenturyDocument17 pagesAhlul Bayt Digital Islamic Library - Nasir Al-Din Tusi and His Socio-Political Role in The Thirteenth CenturyNaldo Hillel HelmysNo ratings yet

- 5.2impact of Islam On Indian Culture - Bhakti and Sufi MovementsDocument13 pages5.2impact of Islam On Indian Culture - Bhakti and Sufi MovementsAnonymous pFCSdqNo ratings yet

- Brill - ChishtiyyaDocument7 pagesBrill - ChishtiyyaSaarthak SinghNo ratings yet

- Sufism Rough NotesDocument4 pagesSufism Rough NotesAnam MalikNo ratings yet

- Shii Polemics at The Mughal Court The CDocument15 pagesShii Polemics at The Mughal Court The CfaisalnamahNo ratings yet

- Shah Waliullah: The Pioneer Thinker of The Modern WorldDocument5 pagesShah Waliullah: The Pioneer Thinker of The Modern WorldUsman AhmadNo ratings yet

- History: (For Under Graduate Student)Document16 pagesHistory: (For Under Graduate Student)Azizuddin KhanNo ratings yet

- Temple Descration - EatonDocument37 pagesTemple Descration - EatonramanxsehgalNo ratings yet

- The Rise and Spread of Islam in Indian SDocument10 pagesThe Rise and Spread of Islam in Indian SAhmed ShaikhNo ratings yet

- 13 Nawab Siddique Hasan Khan PDFDocument13 pages13 Nawab Siddique Hasan Khan PDFSyedkashan RazaNo ratings yet

- Abdullah Shattari and Sstablishmsnt of TheDocument16 pagesAbdullah Shattari and Sstablishmsnt of TheAhmad QutbiNo ratings yet

- Siddiqui - Book ReviewDocument6 pagesSiddiqui - Book Reviewtushar vermaNo ratings yet

- Sufism in India - A Bloodied HistoryDocument7 pagesSufism in India - A Bloodied HistorynayasNo ratings yet

- Shaikh Ahmad Shah SirhindiDocument12 pagesShaikh Ahmad Shah Sirhindidhaarna ojhaNo ratings yet

- The Myth of The Clerical Migration To Safawid Iran: Arab Shiite Opposition To Alī Al-Karakī and Safawid ShiismDocument48 pagesThe Myth of The Clerical Migration To Safawid Iran: Arab Shiite Opposition To Alī Al-Karakī and Safawid ShiismMohamed H Rajmohamed100% (1)

- This Content Downloaded From 195.43.22.136 On Wed, 01 Jul 2020 14:04:50 UTCDocument38 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 195.43.22.136 On Wed, 01 Jul 2020 14:04:50 UTCsaleh fatheNo ratings yet

- Role of Ulema in Organizing Muslim SocietyDocument12 pagesRole of Ulema in Organizing Muslim SocietyJunaid khan.No ratings yet

- Shaykh Qasim NanotwiDocument9 pagesShaykh Qasim Nanotwispeedy.maestro7842No ratings yet

- Shi'ism in Kashmir, 1477-1885Document7 pagesShi'ism in Kashmir, 1477-1885Karim QaiserNo ratings yet

- Eaton Richard - Temple Desecration in Pre-Modern IndiaDocument17 pagesEaton Richard - Temple Desecration in Pre-Modern Indiavoila306100% (1)

- Chishti Article No 2 Tanveer FaridiDocument10 pagesChishti Article No 2 Tanveer FariditanvirNo ratings yet

- Vol48 2 4 AKBiswasDocument20 pagesVol48 2 4 AKBiswasRajendraNo ratings yet

- Chapter TwoDocument35 pagesChapter TwoBawaNo ratings yet

- Shahrastani IdolDocument14 pagesShahrastani Idolbo soNo ratings yet

- Ashraf Ali Thanvi PDFDocument26 pagesAshraf Ali Thanvi PDFaditya_2kNo ratings yet

- Re KubrawiaDocument40 pagesRe Kubrawiaalb 3480% (1)

- Striving For Divine UnionDocument4 pagesStriving For Divine UnionmetfightclubNo ratings yet

- ShahWaliAllahtheMughalsandtheByzantines20141 PDFDocument49 pagesShahWaliAllahtheMughalsandtheByzantines20141 PDFZīshān FārūqNo ratings yet

- Scholars, Saints and Sultans: Some Aspects of Religion and Politics in The Delhi SultanateDocument11 pagesScholars, Saints and Sultans: Some Aspects of Religion and Politics in The Delhi SultanateCallsmetNo ratings yet

- Hatina Religious Culture Sufi Ritual of Dawsa in 19th EgyptDocument30 pagesHatina Religious Culture Sufi Ritual of Dawsa in 19th Egyptdln2510No ratings yet

- Music in Chishti SufismDocument17 pagesMusic in Chishti SufismkhadijaNo ratings yet

- 13 - Chapter 6Document19 pages13 - Chapter 6mali27a7670% (1)

- Sejarah Islam 5Document27 pagesSejarah Islam 5nurulNo ratings yet

- Rizvi - Mir Damad in IndiaDocument16 pagesRizvi - Mir Damad in IndiacalfrancescoNo ratings yet

- Pakistan and Islamiat Studies: Name: Muhammad FawadDocument21 pagesPakistan and Islamiat Studies: Name: Muhammad FawadFawadajmalNo ratings yet

- Ibn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya in The "Lands Below The Wind" - Syamsudin ArifDocument31 pagesIbn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya in The "Lands Below The Wind" - Syamsudin ArifDimas WichaksonoNo ratings yet

- CC-7: HISTORY OF INDIA (c.1206-1526) : Iv. Religion and CultureDocument6 pagesCC-7: HISTORY OF INDIA (c.1206-1526) : Iv. Religion and CultureDurgesh Nandan SrivastavNo ratings yet

- Islamisation of India by SufisDocument23 pagesIslamisation of India by SufisSharad Ghule100% (2)

- Ibn Taymiyyah On The Hadith of The 73 Sects: Institute of Education, International Islamic University Malaysia. HeDocument27 pagesIbn Taymiyyah On The Hadith of The 73 Sects: Institute of Education, International Islamic University Malaysia. HemukhlisinNo ratings yet

- Islam in Hunza, Gilgit and NagarDocument21 pagesIslam in Hunza, Gilgit and Nagarhunzaking100% (7)

- Pages From AJISS 1-1-6 Article 6 Rashid Rida's Struggle To Establish Assad N. BusoolDocument19 pagesPages From AJISS 1-1-6 Article 6 Rashid Rida's Struggle To Establish Assad N. BusoolEisha MunawarNo ratings yet

- Evolution and Role of UlemasDocument9 pagesEvolution and Role of UlemasSaleemAhmadMalik100% (1)

- Chishti Order in DeccanDocument39 pagesChishti Order in DeccanAbuhafsaNo ratings yet

- 864 2438 1 PBDocument36 pages864 2438 1 PBAhmad qiramNo ratings yet

- The Revitalizing Aspect of The Tatar RefDocument10 pagesThe Revitalizing Aspect of The Tatar ReftariqsoasNo ratings yet

- Brill Islamic Law and Society: This Content Downloaded From 152.118.24.10 On Thu, 29 Sep 2016 03:52:25 UTCDocument45 pagesBrill Islamic Law and Society: This Content Downloaded From 152.118.24.10 On Thu, 29 Sep 2016 03:52:25 UTCfauzanrasipNo ratings yet

- Written Works of Zoroastrian Priests After The Arrival of Islam To Iran "In 9 10 Centuries"Document19 pagesWritten Works of Zoroastrian Priests After The Arrival of Islam To Iran "In 9 10 Centuries"Iole Di SimoneNo ratings yet

- The Wilayah of Ali in The Shia Adhan - Liyakat A TakimDocument13 pagesThe Wilayah of Ali in The Shia Adhan - Liyakat A TakimIbrahima SakhoNo ratings yet

- The Intersection Between Sufism and PoweDocument9 pagesThe Intersection Between Sufism and PoweSamita RoyNo ratings yet

- Muslims Destroying Hindu TemplesDocument9 pagesMuslims Destroying Hindu TemplesMarco Passavanti100% (1)

- A Poplular Dictionary of SikhismDocument100 pagesA Poplular Dictionary of SikhismdekovicandresNo ratings yet

- Potter, Lawrence, Sufis and Sultans in Post-Mongol IranDocument27 pagesPotter, Lawrence, Sufis and Sultans in Post-Mongol IranhulegukhanNo ratings yet

- Sirhindi 2Document16 pagesSirhindi 2Sergio Montana100% (1)

- The History of India-Vol IIIDocument403 pagesThe History of India-Vol IIIseadog422789% (9)

- Dalail Al-Khayrat Hizb MondayDocument3 pagesDalail Al-Khayrat Hizb MondayShaiful BahariNo ratings yet

- Kuiz Alkitab (For Kid)Document647 pagesKuiz Alkitab (For Kid)Raymoozer FreddielNo ratings yet

- Bentley CH 14 - The Expansive Realm of IslamDocument6 pagesBentley CH 14 - The Expansive Realm of Islamapi-242081192No ratings yet

- Answer To An Enemy of Islam (English)Document128 pagesAnswer To An Enemy of Islam (English)Dar Haqq (Ahl'al-Sunnah Wa'l-Jama'ah)0% (1)

- Ruling On ItikaafDocument3 pagesRuling On Itikaafdervish2No ratings yet

- Siti Dedeh Widiasih, Amd - KebDocument3 pagesSiti Dedeh Widiasih, Amd - KebEhaaNo ratings yet

- Shah Jahan PresentationDocument30 pagesShah Jahan PresentationjyothibellaryvNo ratings yet

- Robson - Tradition 1 MW 1951Document12 pagesRobson - Tradition 1 MW 1951Arputharaj SamuelNo ratings yet

- Diploma in Islamic StudiesDocument9 pagesDiploma in Islamic StudiesIsa SiddiqueeNo ratings yet

- Islam - Questions and Answers - Islamic Politics (PDFDrive)Document133 pagesIslam - Questions and Answers - Islamic Politics (PDFDrive)Sham khamNo ratings yet

- Rituals of HajjDocument103 pagesRituals of HajjNazim KapadiaNo ratings yet

- Fatwa On InsuranceDocument8 pagesFatwa On InsuranceZishanHyderRajput100% (1)

- Hasan Al-BanaDocument3 pagesHasan Al-BanaShah DrshannNo ratings yet

- The Hamzeviye A Deviant Movement in Bosnian SufismDocument20 pagesThe Hamzeviye A Deviant Movement in Bosnian SufismHusein-Amra Al-BaldawiNo ratings yet

- Safar Academy Textbook 7 Exam Paper 18 - FINALDocument12 pagesSafar Academy Textbook 7 Exam Paper 18 - FINALaaleahmad.hussainNo ratings yet

- Science of HadheesDocument11 pagesScience of HadheesMohamed HussainNo ratings yet

- Minuts of Meeting - 1Document5 pagesMinuts of Meeting - 1hamid aliNo ratings yet

- Biography of Hazrat Mirza Sardar Baig Saheb HyderabadDocument2 pagesBiography of Hazrat Mirza Sardar Baig Saheb HyderabadMohammed Abdul Hafeez, B.Com., Hyderabad, IndiaNo ratings yet

- Ashari SufisDocument2 pagesAshari SufisIbn SadiqNo ratings yet

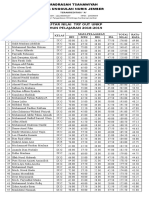

- Daftar Nilai Try Out Unkp TAHUN PELAJARAN 2018-2019Document28 pagesDaftar Nilai Try Out Unkp TAHUN PELAJARAN 2018-2019A'yuni Sa'adahNo ratings yet

- Ibrahim Ismail of JohorDocument10 pagesIbrahim Ismail of JohorWak MilNo ratings yet

- An Najah 2021Document6 pagesAn Najah 2021danishlazy1010No ratings yet

- The Delhi Sultanate Peter Jackson Cambridge University Press 1999Document307 pagesThe Delhi Sultanate Peter Jackson Cambridge University Press 1999MaryamSaddiqua100% (10)

- Tajweed RulesDocument6 pagesTajweed Rulesgulzar72No ratings yet

- Feedbooks Book 29147Document114 pagesFeedbooks Book 29147nadeem5476No ratings yet

- Maths Preschool Activity BookDocument33 pagesMaths Preschool Activity Bookmagnumquest50% (2)

- Universal Brotherhood by Dr. Zakir NaikDocument42 pagesUniversal Brotherhood by Dr. Zakir NaikeminnpNo ratings yet

- QsO IntroDocument5 pagesQsO IntroYasir KhanNo ratings yet

- Islamic Golden AgeDocument17 pagesIslamic Golden AgeMohamed H0% (1)