Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Kidney Preop

Uploaded by

juanpbagurOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Kidney Preop

Uploaded by

juanpbagurCopyright:

Available Formats

In Practice

Preoperative Risk Assessment and

Management in Adults Receiving

Maintenance Dialysis and Those With

Earlier Stages of CKD

Jehan Z. Bahrainwala, Samantha L. Gelfand, Ankur Shah, Blaise Abramovitz,

Brenda Hoffman, and Amanda K. Leonberg-Yoo

With an increasingly aging population and improved mortality in individuals with end-stage kidney Complete author and article

disease, more surgeries are being performed on patients with all stages of chronic kidney disease information provided before

references.

(CKD). This high-risk population carries unique risk factors that have been associated with increased

adverse perioperative outcomes, including acute kidney injury, cardiovascular events, and mortality. In Am J Kidney Dis. XX(XX):1-

this article, we review the literature describing absolute risks associated with common surgeries 11. Published online Month

X, XXXX.

performed in patients with CKD and patients receiving maintenance dialysis. We also review peri-

operative optimization with special risk assessment including evaluation of cardiovascular and bleeding doi: 10.1053/

risk evaluation, hypertension management, and timing of dialysis. Predictive model scores are reviewed j.ajkd.2019.07.008

as a method to stratify risk for acute kidney injury, major adverse cardiac events, or other serious © 2019 by the National

complications with elective surgeries. A multidisciplinary approach with individualized counseling is Kidney Foundation, Inc.

necessary to counsel the patient with advanced CKD or patients treated with maintenance dialysis

considering elective surgery.

Clinical Vignette conditions (Table 1).1 Even patients with FEATURE EDITOR:

A 56-year-old man with diabetes mellitus type earlier stages of chronic kidney disease (CKD) Holly Kramer

2 (for which he used insulin), hypertension, than kidney failure are at increased risk for

dyslipidemia, and kidney failure treated by postoperative cardiac events and mortality.2 ADVISORY BOARD:

Information on the incidence of elective Linda Fried

maintenance hemodialysis is referred to an Ana Ricardo

orthopedic surgeon for persistent left hip pain. surgery in a population with CKD remains

Roger Rodby

Tricompartmental osteoarthritis of the left limited and we lack research-informed guid- Robert Toto

knee was diagnosed 10 years ago. Unable to ance for appropriate preoperative testing for

use nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, he these patients. Nephrologists are likely to be In Practice is a

has been using topical analgesic agents asked to assist both patients and surgeons to focused review

assess and minimize the risks associated with providing in-depth

without relief. He has become more sedentary guidance on a clinical

due to chronic pain. The orthopedic surgeon elective operations. Doing so requires not only

topic that nephrolo-

recommends a total knee arthroplasty. The an understanding of the absolute risks related gists commonly

patient asks about his ability to safely undergo to a surgical procedure, but also specific risk encounter. Using

this procedure, and the surgeon informs the factors related to the patient with kidney clinical vignettes,

disease. these articles illus-

patient that these procedures are commonly trate a complex prob-

performed in patients undergoing dialysis. In this In Practice, we aim to review sur-

lem for which optimal

Before deciding, the patient wishes to discuss gical risks related to elective surgeries in in- diagnostic and/or

the surgery with his nephrologist. dividuals with CKD, including special therapeutic ap-

consideration for patients treated with main- proaches are

tenance dialysis. We also summarize recom- uncertain.

Introduction mendations for preoperative testing and other

Elective surgeries, or operations planned in surgical considerations that should be

advance, as opposed to an urgent or emergent reviewed in a preoperative visit.

procedure, can range from minor low-risk

procedures such as cataract surgery to

high-risk cardiovascular operations such as Surgical Morbidity in Patients With

coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). It is CKD

known that patients treated with dialysis To understand surgical risk in an elective

have increased mortality and higher risk for surgery, it is important to assess the absolute

perioperative complications than those risks of surgery for individuals with CKD,

not receiving dialysis, in part due to a higher including postoperative complications and

prevalence of cardiovascular comorbid mortality risk (Table 2).

AJKD Vol XX | Iss XX | Month 2019 1

In Practice

Table 1. Comorbid Cardiovascular Conditions in Prevalent Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting

Hemodialysis Patients The incidence of CABG in patients receiving maintenance

Comorbid Conditions Percentage dialysis has increased from 2.5 to 5 per 1,000 patient-years

Atherosclerotic coronary artery disease 42.3% during the past 15 years.10 Surgical mortality remains

Acute myocardial infarction 14.0% higher compared with patients not receiving dialysis.

Congestive heart failure 40.4% Studies have shown both non–kidney failure CKD and

Valvular heart disease 14.1% maintenance dialysis to be independent risk factors for

Cerebrovascular accident/transient 16.3% surgical and in-hospital mortality in patients undergoing

ischemic attack CABG.11 In a Japanese cohort of patients undergoing iso-

Peripheral artery disease 37.4% lated CABG, 30-day surgical mortality (7.8% vs 2.1%; P <

Venous thromboembolism and 6.2% 0.001) and 30-day mortality (4.8% vs 1.4%; P < 0.001)

pulmonary embolism

were significantly higher among the 1,300 patients

Based on data in Saran et al.1

receiving maintenance dialysis compared with the 18,000

patients without CKD.12 Differences in mortality were

Cardiac Surgeries largely driven by higher baseline comorbid conditions in

Aortic Valve Replacement patients receiving maintenance dialysis.13

Calcified aortic stenosis is a common valvular disease Alternative revascularization using percutaneous coro-

requiring surgical intervention in patients treated with nary intervention (PCI) is available for the treatment of

dialysis. Surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) is asso- multivessel disease. A recent meta-analysis compared

ciated with increased morbidity and mortality among pa- outcomes in patients with CKD undergoing CABG versus

tients receiving maintenance dialysis. Recent data from the PCI with a drug-eluting stent. The PCI group had higher

US Nationwide Inpatient Sample show that patients rates of all-cause and cardiac mortality, myocardial in-

receiving maintenance dialysis who undergo SAVR have farctions, revascularization procedures, and major adverse

higher inpatient mortality, as well as hospitalization costs cardiac and cerebrovascular events.14 PCIs can involve a

and lengths of stay, compared with those undergoing staged approach for multivessel interventions to minimize

transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR; 13.7% vs contrast exposure, although guidelines do not provide

6.1%; P < 0.02).3 Similar results were found when specific recommendations for use in individuals with

studying patients with non–kidney failure CKD.4 CKD.15,16 A retrospective study of patients undergoing

Although TAVR may have improved outcomes nonemergent multivessel PCI by either staged or ad hoc

compared with SAVR, this procedure is also not without (same session) procedures showed increased cumulative

adverse outcomes in patients with CKD. Among patients radiocontrast with staged procedures.

who undergo TAVR, those with CKD have higher odds of In a subgroup analysis evaluating only individuals with

in-hospital mortality than those without CKD (odds ratios CKD ascertained as an estimated glomerular filtration rate

[ORs] of 1.39 [95% CI, 1.24-1.55] and 2.58 [95% CI, (eGFR) < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, patients had a significant

2.09-3.13] for non–kidney failure CKD and maintenance decline in eGFR at 4 to 12 weeks after staged PCI

dialysis, respectively).5 One study of patients who un- compared with those who underwent ad hoc PCI.17

derwent TAVR reported higher mortality at 30 days and There are no randomized controlled trials comparing

after 1 year among those with CKD stages 4 to 5 compared CABG to PCI in patients with advanced CKD or receiving

with those without CKD.6 However, both groups noted maintenance dialysis. In patients with advanced CKD or

symptom improvement with TAVR. Thus, in patients with receiving maintenance dialysis who have multivessel

CKD who require aortic valve replacement, TAVR should cardiac disease, joint decision making should proceed

be considered over SAVR due to lower mortality risk in this between cardiologists, nephrologists, and cardiac sur-

population. geons to determine optimal treatment strategies for the

Controversy exists regarding the preferred valve mate- individual patient.

rial for patients receiving maintenance dialysis. A bio-

prosthetic valve may be problematic due to accelerated Vascular Surgery

calcification of an already time-limited valve, whereas a It is well known that there is a high burden of vascular

mechanical valve requires systemic anticoagulation in a disease in patients with CKD, and this population repre-

population already at risk for bleeding.7 In both a retro- sents a group with reduced longevity and also higher

spective review and a meta-analysis of data pooled from surgical risk. Elective vascular surgery in this group is

patients receiving maintenance dialysis who underwent usually not without risk. Perioperative morbidity and

aortic valve replacement, there was no difference in sur- mortality risks after elective vascular surgeries for

vival with either a bioprosthetic valve or mechanical abdominal aortic aneurysm, carotid artery stenosis, and

valve.8,9 Thus, surgeons may consider other factors when peripheral vascular disease are available in the National

selecting valve material, such as valve-related complica- Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) data-

tions and patient bleeding risk. base. Risk for 30-day postoperative complications (16.5%

2 AJKD Vol XX | Iss XX | Month 2019

In Practice

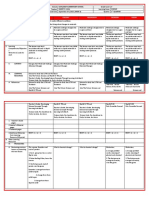

Table 2. Surgical Morbidity Data in Patients With CKDa

Surgery Mortality Data Predictor of Poor Outcome Postoperative Complicationsb

Cardiac Surgery

TAVR5 In-hospital mortalityc Age MACE (9%-11.8%)

• No CKD: 3.8% HLD Major bleeding complication (16.8%-

• CKD: 4.5% Prior PCI 21.6%)

• Dialysis: 8.3% Coagulopathy Requirement for PPM (13.2%-15.2%)

Transapical TAVR Longer LOS

Nonhome discharge

AKI on CKD (34%)

AKI needing dialysis (2.4%)

CABG11,12 In-hospital mortalityc,11 Patient-specific characteristics: Sepsis (2.1%-4.9%)

• No CKD: 1.4% • Age Respiratory complications (4.4%-13.1%)

• CKD: 9.8% Surgery-specific characteristics: GI complication (1%-4.9%)

• Dialysis: 7.3% • Urgent vs nonurgent Longer LOS

30-d mortalityc,12 • Preoperative inotropy Nonhome discharge

• No CKD: 1.4% Comorbid conditions:

• Dialysis: 4.8% • COPD

Surgical mortalityc,12 • Heart disease (CHF, EF < 30%)

• No CKD: 2.1% • Arrhythmias

• Dialysis: 7.8% • Valvular heart disease

• PAD

Elective Vascular Surgery18

AAA repair, CEA, 30-d mortalityc Age > 65 y STI (8%)

PVD repair • No CKD: 1.4% Respiratory complications (1.7%-4.8%)

• Dialysis: 7.2% Return to OR (23.8%)

Joint Arthroplasty25,26

Total knee arthroplasty25 In-hospital mortalityc Liver disease SSTI (1.0%-1.2%)

• No CKD: 0.1% CHF Wound hematoma (2.0%-3.8%)

• Dialysis: 0.92% Cardiac arrythmias Transfusion (36.7%-43.7%)

Total hip arthroplasty26 In-hospital mortalityc PVD Cardiac complication (1.9%-2.1%)

• No CKD: 0.13% Respiratory complication (1.8%-2.3%)

• Dialysis: 1.88% Urinary complication (1.9%-5.2%)

Longer LOS

Elective General Surgery31

Abdominal (94%), 30-d mortalityc Age > 65 y STI (10%)

thoracic, skin, node • No CKD: 1.5% Respiratory complications (7.4%-21.6%)

dissections, • Dialysis: 12.7% Return to OR (18.5%)

head & neck MACCE (0.6%-1.3%)

Longer LOS

Abbreviations: AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm; AKI, acute kidney injury; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CEA, carotid endarterectomy; CHF, congestive heart

failure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; EF, ejection fraction; HLD, hyperlipidemia; GI, gastrointestinal; LOS, length of stay;

MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MACCE, major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events; OR, operating room; PAD, peripheral arterial disease;

PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PPM, permanent pacemaker; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; SSTI, skin and soft-tissue infection; STI, soft-tissue infection;

TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

a

Excluding kidney transplant recipients.

b

Complications are listed only for significant complications in non–kidney failure CKD and/or maintenance dialysis patients, compared with patients without CKD.

c

P < 0.001.

vs 8.4%; P < 0.001) and 30-day mortality (7.2% vs 1.4%; Hemodialysis Access Surgery

P < 0.001) are significantly higher among patients Information for hemodialysis patient outcomes following

receiving maintenance dialysis compared with all other vascular access surgery remains very limited. In a retro-

patients.18 Differences in postoperative complications are spective single-center study, 30-day mortality was 1.1% in

more pronounced with dialysis dependence in patients a cohort of nearly 1,400 patients undergoing vascular ac-

older than 65 years regardless of procedure type. Among cess surgeries. Risk for 30-day mortality was significantly

patients receiving maintenance dialysis who undergo higher with graft versus fistula in the upper arm (2.9% vs

surgery for peripheral vascular disease, the presence of 0.8%; P < 0.005) and with lower-limb access versus

preoperative pain at rest and gangrene were both asso- upper-arm fistula (3.9% vs 0.8%; P < 0.007). There was

ciated with higher mortality risk and postoperative also 6-fold higher risk for 30-day mortality (95% CI, 2.09-

complications.18 Thus, offering elective surgery for 18.8) when using general versus local anesthesia.19

asymptomatic vascular disease in a high-risk older pop- Other studies have evaluated temporal trends of out-

ulation receiving maintenance dialysis requires multidis- comes following fistula surgeries. A large study using the

ciplinary discussion of postoperative complication risks, NSQIP database found that arteriovenous fistula surgeries

including mortality. occurred more frequently in the outpatient setting during

AJKD Vol XX | Iss XX | Month 2019 3

In Practice

the study interval (2005-2008).20 Comparing surgeries worse outcomes than hepatobiliary, splenic, and hernia

performed in an inpatient versus outpatient setting, procedures.

there was higher postoperative morbidity (adjusted OR,

1.93; 95% CI, 1.41-2.60) and higher 30-day mortality Considerations for Preoperative Testing

(adjusted OR, 3.32; 95% CI, 1.70-6.49) for inpatient

No formal guidelines specifically address preoperative

compared with outpatient arteriovenous fistula creation.

evaluation for individuals with advanced CKD, and existing

Importantly, the group that received surgery as inpatients

risk prediction tools are not tailored toward this popula-

had a higher burden of comorbid conditions and lower

tion. We recommend a preoperative assessment that in-

functional status compared with patients with outpatient

cludes GFR, cardiopulmonary fitness, hypertension and

access creation.

anemia management, and bleeding risk for patients with

We recommend timely referral to vascular surgery to

CKD (Box 1).

facilitate access placement in the outpatient setting when

patients are clinically stable. Inpatient access surgeries

should be reserved for patients who need urgent inpatient Acute Kidney Injury Risk Assessment

hemodialysis initiation or have demonstrated poor Postoperative acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common

outpatient follow-up. complication, ranging from 10% after orthopedic pro-

cedures to up to 28% following cardiovascular sur-

Total Joint Arthroplasty

geries.29-30 In one study in a heterogeneous cohort of

The cumulative incidence of total hip arthroplasty is high patients who underwent surgery at Veterans Affairs (VA)

in the dialysis-dependent population (35 episodes/ hospitals, 11.8% of cases had incident postoperative AKI.30

100,000 person-years) compared to 5.3 episodes/10,000 Risk factors for AKI included older age, male sex, African

person-years in the general population.21 In the National American race, and body mass index > 25 kg/m2. In pa-

Inpatient Sample, patients with CKD who underwent total tients with CKD (ascertained as eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73

joint arthroplasty (TJA) had significantly higher in- m2), each 10–mL/min/1.73 m2 greater eGFR was asso-

hospital mortality, longer lengths of stay, and higher ciated with a 20% reduction in risk for AKI incidence.

complication rates overall compared with patients Although this study was limited to a VA population un-

without CKD.22-23 Advanced CKD is associated with 2- dergoing major surgery, the data demonstrate the magni-

fold higher risk for inpatient mortality after TJA as tude of AKI seen postsurgically, as well as the risk

compared with patients without CKD who undergo TJA. associated with a lower eGFR preoperatively.

However, TJA in patients receiving maintenance dialysis To identify those at risk for postsurgical AKI, several risk

is associated with 10-fold higher risk for inpatient mor- prediction tools have been developed for perioperative use

tality compared with patients without CKD.23 Thus, (Table 3). These risk scores share 4 common variables:

complication rates after TJA increase with advancing preoperative kidney function, diabetes mellitus, cardiac

stages of CKD. Because complication rates after TJA are surgery characteristics, and preoperative hemodynamic

lower among kidney transplant recipients as compared status. Model performance comparison found that the

with patients treated by dialysis,22-24 delaying total hip Cleveland Clinic Score and the Society of Thoracic Sur-

arthroplasty until after kidney transplantation may be geons score were consistently better at predicting severe

prudent when possible. Despite the higher rate of com- postoperative AKI and the need for kidney replacement

plications with TJA among patients with CKD, reported therapy, although bedside clinical usability decreases with

survival rates are as high as 98% at 5 to 10 years and 64% an increased number of variables included.31 Although

at 20 years.25-27 both serum creatinine level and eGFR are strong predictors

of postoperative AKI, risk models that use GFR estimators

Abdominal Surgery

demonstrate superior predictive power than models using

Few studies have assessed surgical risks in patients serum creatinine level as a dichotomous single-dimension

receiving maintenance dialysis after noncardiovascular surrogate of kidney function.32-33 Depending on baseline

procedures. In one study, risk for perioperative morbidity CKD status, the risk for AKI requiring kidney replacement

and mortality in patients receiving maintenance dialysis therapy and CKD progression should be discussed with

who undergo undergoing elective general surgeries patients.30,34

(abdominal surgery in 94%) was compared with risk

among patients with non–kidney failure CKD using the

NSQIP database.28 Patients receiving maintenance dialysis Cardiopulmonary Risk Assessment

had higher odds of soft-tissue infections (OR, 1.55; 95% CKD is an independent risk factor for adverse cardiovas-

CI, 1.37-1.75), death (OR, 2.57; 95% CI, 2.15-3.08), and cular events in the general population.35 However, it is

need for reoperation (OR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.68-2.25) challenging to assess cardiovascular fitness in a population

compared with those with earlier stages of CKD. Among with CKD, and risk stratification may differ compared with

patients receiving maintenance dialysis, gastric, small- a general population. Variables to consider include sur-

bowel, and colorectal procedures were associated with gery- and patient-specific risk factors. The American

4 AJKD Vol XX | Iss XX | Month 2019

In Practice

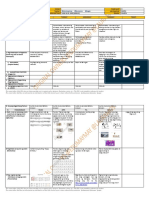

Box 1. Summary of Pre- and Perioperative Evaluation Recommendations

Preoperative Evaluation

Acute Kidney Injury Risk

• Assess baseline kidney function using eGFR within 1 mo of surgery

• Consider use of risk prediction tools (Cleveland Clinic Score vs STS score)74,75

Cardiopulmonary Risk

• Suggest baseline electrocardiogram and Doppler echocardiogram

• Assess functional capacity using METs criteria

• For maintenance dialysis patients, consider noninvasive cardiac testing, such as dobutamine stress echocardiography

• If considered high risk or noninvasive testing is not adequate, consult cardiology expert

Hypertension Management

• Recommend adequate BP and volume control

• Ideal BP < 140/90 mm Hg

Anemia Management

• Recommend optimizing hemoglobin to KDIGO target (10-11.5 g/dL)

• Discuss risk of transfusion for transplantation-eligible patients

Dialysis Management

• Ensure adequate dialysis using national target Kt/V of 1.2 for thrice-weekly dialysis

• Avoid elective surgery if active infection

• Optimize nutritional status using oral nutritional supplementation

Perioperative Evaluation

Hypertension Management

• Recommend antihypertensive therapies to be continued up to the morning of surgery

• Elective surgery can proceed if BP is <180/110 mm Hg, unless end-organ damage is present

• Consider holding renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockade agents and diuretics

Bleeding Risk

• Use desmopressin (intravenous or subcutaneous) if history of excessive bleeding

• Hold anticoagulation based on medication, bleeding risk, procedural risk, baseline eGFR69

• Check INR (warfarin), thrombin time (dabigatran), or anti-Xa levels (Xa inhibitors) if high risk

eGFR 30-60 eGFR < 30 Maintenance Dialysis

Warfarin Hold 3-5 d before surgery; check INR 24 h preoperatively

Dabigatran 2-4 d 3-5 d Not recommended

Factor Xa inhibitora 24-48 h 36-72 h 48-72 h

Dialysis Management

• Avoid scheduling surgeries over long interdialytic period

• Avoid hyperkalemia by ensuring adequate dialysis or evaluating perioperative electrolytes

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate (in mL/min/1.73 m2); INR, international normalized ratio; KDIGO, Kidney Disease:

Improving Global Outcomes; MET, metabolic equialent; STS, Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

a

Apixaban, edoxaban, or rivaroxaban.

College of Surgeons NSQIP Surgical Risk Calculator in- further testing is recommended; if unknown or <4 METs,

cludes a specific Current Procedural Terminology code to allow this is considered indeterminate cardiac risk.

for procedure-specific risk assessment to be included in an Depending on risk markers, these individuals are strat-

individual’s surgical risk assessment.36,37 ified to determine whether further testing is indicated. Risk

The American College of Cardiology/American Heart markers for coronary artery disease include ischemic heart

Association (ACC/AHA) joint guidelines identify clinical disease compensated or prior heart failure, diabetes mel-

risk for major adverse cardiac events in the general pop- litus, “renal insufficiency,” and cerebrovascular disease.

ulation as unstable coronary syndrome, decompensated Using these risk markers, one can increase the pretest

heart failure, significant arrhythmia, and severe valvular probability and thus improve the diagnostic yield of

heart disease.38,39 If these clinical risks are not present, risk noninvasive testing. However, these guidelines have been

stratification should be performed on the basis of func- designed for a general population and do not specifically

tional capacity, estimated using metabolic equivalents consider CKD or dialysis dependence. It is difficult to assess

(METs; Table 4). If functional capacity is ≥4 METs, no functional status in patients receiving maintenance dialysis.

AJKD Vol XX | Iss XX | Month 2019 5

In Practice

Table 3. Risk Prediction Tools Evaluating Risk for Kidney Injury Postoperatively

Model Prediction and Performance36 Variables

Name of Model Surgery/Procedure Postop AKI Postop KRT Kidney Nonkidney

Cleveland Clinic Open-heart surgery AUROC = 0.81 AUROC = 0.86 Preop Scr (<1.2, 1.2- Female sex

Foundation Risk Score74 (95% CI, 0.79- (95% CI, 0.84- <2.1, or ≥2.1 mg/dL) Heart failurea

0.83) 0.88) COPD

DM

Cardiac surgery

characteristicsb

Society of Thoracic CABG, valvular surgery, AUROC = 0.81 AUROC = 0.76 Preop Scr Age

Surgeons (STS) Risk CABG + valve (95% CI, 0.78- (95% CI, 0.73- Nonwhite race

Model75 0.86) 0.80) DM

Prior CV surgery

Hemodynamic

stabilityc

COPD

Simplified Renal Index Cardiac surgery with AUROC = 0.79 AUROC = 0.75 Preop eGFR (>60, DM

Score76 cardiopulmonary (95% CI, 0.77- (95% CI, 0.72- 30-60, or ≤30 Heart failurea

bypass 0.82) 0.77) mL/min) Cardiac surgery

characteristicsb

General Surgery AKI Noncardiovascular C statistic = 0.80 Preop Scr > 1.2 Age

Risk Index77 surgeries mg/dL Sex

DM

Surgical

urgency

CHF

HTN

Note: Utility of model defines AKI severity. Validation by an external cohort for discrimination between scores.

Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; AUROC, area under receiver operator characteristic curve; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CHF, congestive heart failure;

CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CV, cardiovascular; DM, diabetes mellitus; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HTN, hy-

pertension; KRT, kidney replacement therapy; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; Preop, preoperative; Scr, serum creatinine.

a

Heart failure defined as LVEF < 35%, preoperative intra-aortic balloon pump use. In the Simplified Renal Index Score, LVEF cutoff was < 40%.

b

Prior cardiac surgery, urgency of surgery, type of surgery, defined as valve only vs CABG vs CABG + valve vs other.

c

Hemodynamic stability assessed by cardiogenic shock, New York Heart Association class IV symptoms, recent myocardial infarction.

This, coupled with higher baseline risk for cardiac disease, name a few, and diagnostic capabilities may differ based

suggests that noninvasive methods for cardiovascular on the noninvasive test.41,42 In these cases, engagement of

fitness be used more judiciously in this population. In a cardiologist for risk assessment may be preferred.

transplantation-eligible individuals, guidelines have rec- Pulmonary hypertension is also highly prevalent in

ommended noninvasive stress testing regardless of func- patients with CKD, ranging from 10% to 25% in stage 5

tional status, given the presence of cardiovascular disease CKD to 8% to 68% among maintenance dialysis patients.43

risk factors.40 Noninvasive imaging in individuals with Pulmonary hypertension is associated with significantly

CKD can be less accurate due to limited exercise tolerance, increased risk for death and cardiovascular events in pa-

arrhythmias, and abnormal baseline electrocardiograms, to tients with CKD regardless of dialysis dependence.44 Pul-

monary hypertension is also associated with increased

Table 4. Estimates of Metabolic Expenditure of Common perioperative mortality and morbidity, including hemo-

Activities dynamic instability, hypoxia, and respiratory fail-

Metabolic Expenditure

ure.38,45,46 Given the increased prevalence of pulmonary

(METs)a Activity hypertension among patients with CKD, it is reasonable to

1 MET Self-care assess using noninvasive means in a preoperative setting.

Dressing This may influence intraoperative management, including

Walking indoors optimizing fluid balance and use of intraoperative hemo-

Walking 1 block on level ground at dynamic monitoring.

2-3 mph

4 METs Climbing a flight of stairs

Although no specific guidelines exist for perioperative

Walking up a hill cardiovascular risk assessment before an elective surgery in

Walking on level ground at 4 mph a kidney disease population, the NKF-KDOQI (National

Golf (without a cart) Kidney Foundation–Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality

Dancing

Running a short distance Initiative) guideline suggests “stress imaging is appropriate

>10 METs Strenuous sports (baseball, football, (at the discretion of the patient’s physician) in selected

skiing) high-risk dialysis for risk stratification even in patients who

Abbreviation: MET, metabolic equivalent. are not renal transplant candidates.”47(p S18) Combination

a

One MET is defined as the basal oxygen consumption of a 40-year-old 70-kg man. of both the ACC/AHA and KDOQI recommendations

6 AJKD Vol XX | Iss XX | Month 2019

In Practice

should be individualized based on surgical and patient risk. continuation or withdrawal of renin-angiotensin-

Additional research in this area is encouraged to provide aldosterone system blockade, although hemodynamic

more accurate risk assessment for this high-risk group. instability with anesthesia exposure and risk for hyper-

kalemia should be considered if continuing.54

Management of Hypertension

Hypertension is associated with increased risk for adverse Management of Anemia and Bleeding Risk

outcomes in a perioperative setting, including AKI, car- Assessment

diovascular outcomes, and end-organ damage.30 Key fac- Patients with advanced CKD or who are receiving main-

tors to consider in hypertensive patients in the tenance dialysis are at increased risk for perioperative

perioperative setting include the degree of hypertension bleeding.55 Perioperative bleeding contributes to both

that is considered safe for an elective surgery, blood mortality and morbidity, including the need for blood

pressure lability in an surgical setting, and optimal blood transfusion and reoperations.56 In a population that may

pressure medical treatment. Attention to blood pressure be eligible for transplantation, risk for sensitization with

management in populations with advanced CKD and blood transfusions becomes an important consideration in

dialysis-dependent CKD is necessary due to risks for AKI, preoperative risk assessment.

CKD progression, and loss of residual kidney function. Anemia and platelet dysfunction contribute to periop-

In a general population, the risk for perioperative erative bleeding and transfusion needs in patients with

complications in individuals with hypertension is higher CKD. Anemia is common in CKD due to relative erythro-

than that in normotensive individuals. In a meta-analysis, poietin deficiency and iron deficiency anemia.57 Relative

the pooled OR of risk for perioperative cardiovascular platelet dysfunction results from defects in activation, ag-

complications in a pre-existing hypertensive population gregation, and adhesion caused by uremic toxins. Addi-

was found to be 1.35 (95% CI, 1.17-1.56), although tionally, anemia may disrupt usual blood rheology; under

methodological limitations, including heterogeneity in normal conditions, red blood cells usually flow through

patient populations and definitions of pre-existing hyper- the center of the vessel lumen while platelets tend to travel

tension, make these risk estimates less reliable.48 Another along the periphery. In anemic conditions, laminar platelet

study found that severely uncontrolled hypertension flow is disrupted, further impairing their function in pri-

(blood pressure > 180/110 mm Hg) has been associated mary hemostasis following endovascular injury.58

with increased risk for cardiovascular and kidney adverse There are several ways to mitigate perioperative

outcomes.49 It has been suggested that surgery may be bleeding risk. First, optimization of anemia preoperatively

deferred or delayed for individuals with severely uncon- with the use of recombinant human erythropoietin and

trolled hypertension, especially if there is evidence of end- treatment of iron deficiency anemia may minimize the risk

organ damage (eg, electrocardiogram changes concerning for postoperative transfusions. The use of erythropoiesis-

for ischemia or CKD). There is a paucity of data regarding stimulating agents can also help reduce bleeding time

perioperative blood pressure control in individuals with and enhance platelet aggregation independent of anemia

CKD. treatment.59

The presence of hypertension can also influence Second, it is essential that patients receiving mainte-

response to anesthesia.49 Prior studies have shown that nance dialysis are dialyzed adequately before surgery. It

anesthesia-induced vasodilation is associated with a has been shown that adequate dialysis improves functional

decrease in arterial pressure to a similar degree in both platelet abnormalities.60 It is unknown whether increasing

hypertensive and normotensive individuals. However, the preoperative dialysis dose reduces bleeding events or im-

absolute reduction in blood pressure in the hypertensive proves surgical outcomes.

subgroup was found to be greater given the higher pre- Third, the knowledge of increased bleeding risk in

anesthesia blood pressure.49,50 Although not directly maintenance dialysis patients can be taken into account by

studied, it may be inferred that individuals with impair- the surgical team to reduce the risk for symptomatic

ment in renal autoregulation may be more susceptible to postoperative bleeding (eg, selection of surgical approach,

changes in blood pressure in an anesthesia setting.51 For placement of drains, and more vigilant postoperative

individuals with hypertension, aggressive reduction in monitoring).

preoperative blood pressure may be more harmful. For patients maintained on anticoagulation therapy,

It is recommended that elective surgery can proceed if temporary interruption of the anticoagulant is usually

blood pressure is <180/110 mm Hg unless evidence of required before elective surgery to mitigate bleeding risk.

end-organ damage is present. Ideally, blood pressure Contemporary use of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs)

should be controlled before surgery to a goal of <140/90 has increased among patients with CKD despite the

mm Hg. However, the risk for abrupt reduction in blood exclusion of patients with advanced CKD (estimated

pressure to achieve this target immediately preoperatively creatinine clearance less than 25-30 mL/min) in safety and

may confer additional risk.52 We recommend that anti- efficacy trials.61-63 All DOACs undergo renal clearance, but

hypertensive therapies be continued up to the morning of these agents vary distinctly in their pharmacokinetics

surgery.53 There is insufficient evidence to guide either and therefore have different requirements for dose

AJKD Vol XX | Iss XX | Month 2019 7

In Practice

adjustment in CKD. For patients using a DOAC who protein-energy wasting. Little can be done to affect these

require treatment interruption before surgery, the with- conditions in an acute setting, although if an elective

holding duration will depend on procedural bleeding risk, surgery can be postponed to improve these comorbid

the specific DOAC agent, and kidney function (Box 1).64 conditions, there may be a theoretical benefit.

Few data exist for the perioperative management of

DOACs in patients receiving maintenance dialysis, and

Case Review and Conclusions

monitoring of coagulation parameters is a consideration in

these and other high-risk patients. All DOACs carry a black The clinical vignette involves a patient with a perioperative

box warning to avoid use in patients undergoing spinal/ risk for a serious complication of 2.8% using the NSQIP

epidural anesthesia. Surgical Risk Calculator.37 Because pain was limiting his

exertion, his metabolic capacity cannot be evaluated, so we

Additional Risk Assessment in the Dialysis recommended that he undergo noninvasive testing for

Population coronary artery disease. Before surgery, anemia and hy-

An important consideration for elective surgery is the pertension management were optimized. Surgery was

timing of hemodialysis preoperatively. In a retrospective scheduled for a midweek nondialysis day to avoid

analysis using Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns increased morbidity and mortality from the long dialysis-

Study (DOPPS) data, Zhang et al showed increased all- free interval.

cause mortality following the longest interval without Despite the limited data and retrospective study designs,

dialysis (hazard ratios of 1.40 [United States], 1.30 elective surgery in CKD is associated with significant

[Europe], and 1.34 [Japan]; all P < 0.05).65 Risk for morbidity and mortality that is higher than in the non-

sudden cardiac death and arrhythmias is also greatest CKD population. We describe a clinical scenario in

during the prolonged interdialytic period.66,67 Proposed which a patient receiving maintenance dialysis is consid-

mechanisms include alterations in volume status and blood ering an elective surgery. By reviewing surgery-specific

pressure, electrolyte imbalances, and changes in arterial risk factors, including risk estimates of mortality, as well

wall parameters.68 Avoidance of the long interdialytic as perioperative risk factors, nephrologists should counsel

period for elective surgeries should be recommended a patient on his or her individual risk for postsurgical

when appropriate. complications.

In the perioperative setting, both hypo- and hyper-

kalemia contribute to arrhythmias and major adverse car- Article Information

diac events.69,70 In a large cohort study using a VA Authors’ Full Names and Academic Degrees: Jehan Z.

population undergoing surgical procedures, individuals Bahrainwala, MD, Samantha L. Gelfand, MD, Ankur Shah, MD,

with a serum potassium level > 5.5 mmol/L had increased Blaise Abramovitz, DO, Brenda Hoffman, MD, and Amanda K.

Leonberg-Yoo, MD, MS.

hazard of major adverse cardiac events (hazard ratio, 2.17;

Authors’ Affiliations: Renal-Electrolyte and Hypertension Division,

95% CI, 1.75-2.70) compared with those with normoka- Department of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia,

lemia (defined as serum potassium of 4-5.5 mmol/L).69 PA (JZB, SLG, BH, AKL-Y); Division of Kidney Disease &

Serious hyperkalemia (defined as serum potassium > 6.0 Hypertension, Department of Medicine, Brown University (AS);

mmol/L) has been described in 10% of maintenance Division of Nephrology, Medical Service, Providence Veterans

dialysis patients, even if adequate dialysis is being per- Affairs Medical Center Providence, RI (AS); and Division of Renal-

Electrolyte, Department of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh,

formed.71,72 In a prospective study evaluating preproce- Pittsburgh, PA (BA).

dural whole-blood potassium levels before vascular access

Address for Correspondence: Jehan Z. Bahrainwala, MD, Renal

procedures in hemodialysis patients, 14.3% had moderate Electrolyte and Hypertension Division, Penn Presbyterian Medical

or severe hyperkalemia (defined as venous blood gas po- Center, 240 Medical Office Bldg, 51 N 39th St, Philadelphia, PA

tassium > 5.7 mEq/L).73 These findings overestimate 19104. E-mail: jehan.bahrainwala@uphs.upenn.edu

hyperkalemia due to malfunctioning dialysis access or Authors’ Contributions: All authors contributed equally to the

inadequate dialysis. However, the collective literature writing of this article.

showing increased adverse outcomes with higher potas- Support: None.

sium levels, alongside the higher prevalence of hyper- Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no

kalemia in this population, should prompt routine relevant financial interests.

assessment of perioperative electrolytes as close to the time Other Disclosures: Dr Gelfand was a member of the 2018 class of

of surgery as possible, unless proof of adequate dialysis is AJKD Editorial Interns; she was fully recused from any involvement

established preoperatively. in the manuscript consideration process.

Additional preoperative characteristics in patients Disclaimer: The case presentation, although based on a typical

dialysis patient, is not based on a specific patient case.

receiving maintenance dialysis may influence adverse

outcomes, including infectious complications and malnu- Peer Review: Received November 12, 2018, in response to an

invitation from the journal. Evaluated by 3 external peer reviewers

trition. There are numerous risk factors that predispose and a member of the Feature Advisory Board, with direct editorial

individuals receiving dialysis to infection, including a input from the Feature Editor and a Deputy Editor. Accepted in

high burden of comorbid conditions, uremia, and revised form July 1, 2019.

8 AJKD Vol XX | Iss XX | Month 2019

In Practice

intervention for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction:

References

an update of the 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percu-

1. Saran R, Robinson B, Abbott KC, et al. US Renal Data System taneous coronary intervention and the 2013 ACCF/AHA

2017 Annual Data Report: epidemiology of kidney disease in guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial

the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;71(3)(suppl 1):S1- infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(10):1235-1250.

S676. 17. Shah M, Gajanana D, Wheeler DS, et al. Effects of staged

2. Mathew A, Devereaux PJ, O’Hare A, et al. Chronic kidney dis- versus ad hoc percutaneous coronary interventions on renal

ease and postoperative mortality: a systematic review and function-is there a benefit to staging? Cardiovasc Revasc Med

meta-analysis. Kidney Int. 2008;73(9):1069-1081. Mol Interv. 2017;18(5):344-348.

3. Alqahtani F, Aljohani S, Boobes K, et al. Outcomes of trans- 18. Gajdos C, Hawn MT, Kile D, et al. The risk of major elective

catheter and surgical aortic valve replacement in patients on vascular surgical procedures in patients with end-stage renal

maintenance dialysis. Am J Med. 2017;130(12):1464.e1- disease. Ann Surg. 2013;257(4):766-773.

1464.e11. 19. Jorna T, Methven S, Ravanan R, Weale AR, Mouton R. 30-Day

4. Doshi R, Shah J, Patel V, Jauhar V, Meraj P. Transcatheter or mortality after haemodialysis vascular access surgery: a retro-

surgical aortic valve replacement in patients with advanced spective observational study. J Vasc Access. 2016;17(3):215-

kidney disease: a propensity score-matched analysis. Clin 219.

Cardiol. 2017;40(11):1156-1162. 20. Hicks CW, Bronsert M, Hammermeister KE, et al. Temporal

5. Gupta T, Goel K, Kolte D, et al. Association of chronic kidney trends, determinants, and outcomes of inpatient versus

disease with in-hospital outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve outpatient arteriovenous fistula operations. Ann Vasc Surg.

replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10(20):2050- 2018;46:65-74.e61.

2060. 21. Abbott KC, Bucci JR, Agodoa LY. Total hip arthroplasty in

6. Allende R, Webb JG, Munoz-Garcia AJ, et al. Advanced chronic chronic dialysis patients in the United States. J Nephrol.

kidney disease in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve 2003;16(1):34-39.

implantation: insights on clinical outcomes and prognostic 22. Ponnusamy KE, Jain A, Thakkar SC, Sterling RS, Skolasky RL,

markers from a large cohort of patients. Eur Heart J. Khanuja HS. Inpatient mortality and morbidity for

2014;35(38):2685-2696. dialysis-dependent patients undergoing primary total hip or

7. Phan K, Zhao DF, Zhou JJ, Karagaratnam A, Phan S, Yan TD. knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(16):1326-

Bioprosthetic versus mechanical prostheses for valve replace- 1332.

ment in end-stage renal disease patients: systematic review 23. Cavanaugh PK, Chen AF, Rasouli MR, Post ZD, Orozco FR,

and meta-analysis. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8(5):769-777. Ong AC. Complications and mortality in chronic renal failure

8. Thourani VH, Sarin EL, Keeling WB, et al. Long-term survival for patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty: a comparison be-

patients with preoperative renal failure undergoing bio- tween dialysis and renal transplant patients. J Arthroplast.

prosthetic or mechanical valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;31(2):465-472.

2011;91(4):1127-1134. 24. Lieu D, Harris IA, Naylor JM, Mittal R. Review article: total hip

9. Chan V, Chen L, Mesana L, Mesana TG, Ruel M. Heart valve replacement in haemodialysis or renal transplant patients.

prosthesis selection in patients with end-stage renal disease J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2014;22(3):393-398.

requiring dialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 25. Sakalkale DP, Hozack WJ, Rothman RH. Total hip arthroplasty

2011;97(24):2033-2037. in patients on long-term renal dialysis. J Arthroplast.

10. Parikh DS, Swaminathan M, Archer LE, et al. Perioperative 1999;14(5):571-575.

outcomes among patients with end-stage renal disease 26. Chang JS, Han DJ, Park SK, Sung JH, Ha YC. Cementless total

following coronary artery bypass surgery in the USA. Nephrol hip arthroplasty in patients with osteonecrosis after kidney

Dial Transplant. 2010;25(7):2275-2283. transplantation. J Arthroplast. 2013;28(5):824-827.

11. Chikwe J, Castillo JG, Rahmanian PB, Akujuo A, Adams DH, 27. Goffin E, Baertz G, Rombouts JJ. Long-term survivorship

Filsoufi F. The impact of moderate-to-end-stage renal failure on analysis of cemented total hip replacement (THR) after avas-

outcomes after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. cular necrosis of the femoral head in renal transplant recipients.

J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2010;24(4):574-579. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21(3):784-788.

12. Yamauchi T, Miyata H, Sakaguchi T, et al. Coronary artery 28. Gajdos C, Hawn MT, Kile D, Robinson TN, Henderson WG.

bypass grafting in hemodialysis-dependent patients: analysis of Risk of major nonemergent inpatient general surgical proced-

Japan Adult Cardiovascular Surgery Database. Circ J. ures in patients on long-term dialysis. JAMA Surg.

2012;76(5):1115-1120. 2013;148(2):137-143.

13. Kutner NG, Zhang R, Huang Y, Herzog CA. Cardiac rehabili- 29. Corredor C, Thomson R, Al-Subaie N. Long-term conse-

tation and survival of dialysis patients after coronary bypass. quences of acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery: a sys-

J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(4):1175-1180. tematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth.

14. Wang Y, Zhu S, Gao P, Zhang Q. Comparison of coronary 2016;30(1):69-75.

artery bypass grafting and drug-eluting stents in patients with 30. Grams ME, Sang Y, Coresh J, et al. Acute kidney injury after

chronic kidney disease and multivessel disease: a meta- major surgery: a retrospective analysis of Veterans Health

analysis. Eur J Intern Med. 2017;43:28-35. Administration data. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67(6):872-880.

15. Blankenship JC, Moussa ID, Chambers CC, et al. Staging of 31. Englberger L, Suri RM, Li Z, et al. Validation of clinical scores

multivessel percutaneous coronary interventions: an expert predicting severe acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery. Am

consensus statement from the Society for Cardiovascular J Kidney Dis. 2010;56(4):623-631.

Angiography and Interventions. Cathet Cardiovasc Interv. 32. Kertai MD, Boersma E, Bax JJ, et al. Comparison between

2012;79(7):1138-1152. serum creatinine and creatinine clearance for the prediction of

16. Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2015 ACC/AHA/ postoperative mortality in patients undergoing major vascular

SCAI focused update on primary percutaneous coronary surgery. Clin Nephrol. 2003;59(1):17-23.

AJKD Vol XX | Iss XX | Month 2019 9

In Practice

33. Walter J, Mortasawi A, Arnrich B, et al. Creatinine clearance 48. Howell SJ, Sear JW, Foex P. Hypertension, hypertensive heart

versus serum creatinine as a risk factor in cardiac surgery. disease and perioperative cardiac risk. Br J Anaesth.

BMC Surg. 2003;3:4. 2004;92(4):570-583.

34. Bell S, Lim M. Optimizing peri-operative care to prevent acute 49. Prys-Roberts C, Meloche R, Foex P. Studies of anaesthesia in

kidney injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018 Sep 11; https:// relation to hypertension. I. Cardiovascular responses of treated

doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfy269. and untreated patients. Br J Anaesth. 1971;43(2):122-137.

35. Weiner DE. Chronic kidney disease as a risk factor for car- 50. Goldman L, Caldera DL. Risks of general anesthesia and

diovascular disease and all-cause mortality: a pooled analysis elective operation in the hypertensive patient. Anesthesiology.

of community-based studies. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(5): 1979;50(4):285-292.

1307-1315. 51. Palmer BF. Renal dysfunction complicating the treatment of

36. Cohen ME, Ko CY, Bilimoria KY, et al. Optimizing ACS NSQIP hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(16):1256-1261.

modeling for evaluation of surgical quality and risk: patient risk 52. Sear JW. Perioperative control of hypertension: when will it

adjustment, procedure mix adjustment, shrinkage adjustment, adversely affect perioperative outcome? Curr Hypertens Rep.

and surgical focus. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217(2):336-346.e331. 2008;10(6):480-487.

37. American College of Surgeons. ACS NSQIP Surgical 53. Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, et al. ACC/AHA 2006

Risk Calculator. https://riskcalculator.facs.org/RiskCalculator/ guideline update on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation for

PatientInfo.jsp. Accessed May 1, 2019. noncardiac surgery: focused update on perioperative beta-

38. Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al. 2014 ACC/ blocker therapy: a report of the American College of Cardiol-

AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and ogy/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice

management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2002 Guidelines

executive summary: a report of the American College of on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation for Noncardiac

Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice Surgery) developed in collaboration with the American Society

guidelines. Developed in collaboration with the American of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology,

College of Surgeons, American Society of Anesthesiologists, Heart Rhythm Society, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiol-

American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of ogists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and In-

Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for terventions, and Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology.

Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(11):2343-2355.

Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, and Society of Vascular 54. Hollmann C, Fernandes NL, Biccard BM. A systematic review

Medicine Endorsed by the Society of Hospital Medicine. J Nucl of outcomes associated with withholding or continuing

Cardiol. 2015;22(1):162-215. angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin re-

39. Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al. 2014 ACC/ ceptor blockers before noncardiac surgery. Anesth Analg.

AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and 2018;127(3):678-687.

management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a 55. Winkelmayer WC, Levin R, Avorn J. Chronic kidney disease as

report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart a risk factor for bleeding complications after coronary artery

Association Task Force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll bypass surgery. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41(1):84-89.

Cardiol. 2014;64(22):e77-e137. 56. Acedillo RR, Shah M, Devereaux PJ, et al. The risk of periop-

40. Lentine KL, Costa SP, Weir MR, et al. Cardiac disease evalu- erative bleeding in patients with chronic kidney disease: a

ation and management among kidney and liver transplantation systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2013;258(6):

candidates: a scientific statement from the American Heart 901-913.

Association and the American College of Cardiology Founda- 57. Bahrainwala J, Berns JS. Diagnosis of iron-deficiency anemia in

tion: endorsed by the American Society of Transplant chronic kidney disease. Semin Nephrol. 2016;36(2):94-98.

Surgeons, American Society of Transplantation, and National 58. Galbusera M, Remuzzi G, Boccardo P. Treatment of bleeding in

Kidney Foundation. Circulation. 2012;126(5):617-663. dialysis patients. Semin Dial. 2009;22(3):279-286.

41. Shroff GR, Herzog CA. Coronary revascularization in patients 59. Cases A, Escolar G, Reverter JC, et al. Recombinant human

with CKD stage 5D: pragmatic considerations. J Am Soc erythropoietin treatment improves platelet function in uremic

Nephrol. 2016;27(12):3521-3529. patients. Kidney Int. 1992;42(3):668-672.

42. Wang LW, Fahim MA, Hayen A, et al. Cardiac testing for cor- 60. Hedges SJ, Dehoney SB, Hooper JS, Amanzadeh J, Busti AJ.

onary artery disease in potential kidney transplant recipients. Evidence-based treatment recommendations for uremic

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:CD008691. bleeding. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2007;3(3):138-153.

43. Bolignano D, Rastelli S, Agarwal R, et al. Pulmonary hyper- 61. Weber J, Olyaei A, Shatzel J. The efficacy and safety of direct

tension in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(4):612-622. oral anticoagulants in patients with chronic renal insufficiency: a

44. Tang M, Batty JA, Lin C, Fan X, Chan KE, Kalim S. Pulmonary review of the literature. Eur J Haematol. 2019;102(4):312-318.

hypertension, mortality, and cardiovascular disease in CKD and 62. Turakhia MP, Blankestijn PJ, Carrero JJ, et al. Chronic kidney

ESRD patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J disease and arrhythmias: conclusions from a Kidney Disease:

Kidney Dis. 2018;72(1):75-83. Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Confer-

45. Kaw R, Pasupuleti V, Deshpande A, Hamieh T, Walker E, ence. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(24):2314-2325.

Minai OA. Pulmonary hypertension: an important predictor of 63. January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS

outcomes in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. Respir focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the

Med. 2011;105(4):619-624. management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the

46. Minai OA, Yared JP, Kaw R, Subramaniam K, Hill NS. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association

Perioperative risk and management in patients with pulmonary Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart

hypertension. Chest. 2013;144(1):329-340. Rhythm Society. Heart Rhythm. 2019;16(8):e66-e93.

47. National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guide- 64. Doherty JU, Gluckman TJ, Hucker WJ, et al. 2017 ACC expert

lines for cardiovascular disease in dialysis patients. Am J Kid- consensus decision pathway for periprocedural management

ney Dis. 2005;45(4)(suppl 3):S1-S153. of anticoagulation in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: a

10 AJKD Vol XX | Iss XX | Month 2019

In Practice

report of the American College of Cardiology Clinical Expert surgery patients. Multicenter Study of Perioperative Ischemia

Consensus Document Task Force. J Am Coll Cardiol. Research Group. JAMA. 1999;281(23):2203-2210.

2017;69(7):871-898. 71. Tzamaloukas AH, Avasthi PS. Temporal profile of serum po-

65. Zhang H, Schaubel DE, Kalbfleisch JD, et al. Dialysis outcomes tassium concentration in nondiabetic and diabetic outpatients

and analysis of practice patterns suggests the dialysis schedule on chronic dialysis. Am J Nephrol. 1987;7(2):101-109.

affects day-of-week mortality. Kidney Int. 2012;81(11):1108- 72. Ahmed J, Weisberg LS. Hyperkalemia in dialysis patients.

1115. Semin Dial. 2001;14(5):348-356.

66. Brunelli SM, Du Mond C, Oestreicher N, Rakov V, Spiegel DM. 73. Ross J, DeatherageHand D. Evaluation of potassium levels

Serum potassium and short-term clinical outcomes among before hemodialysis access procedures. Semin Dial. 2015;

hemodialysis patients: impact of the long interdialytic interval. 28(1):90-93.

Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70(1):21-29. 74. Thakar CV, Arrigain S, Worley S, Yared JP, Paganini EP.

67. Wong MC, Kalman JM, Pedagogos E, et al. Temporal distri- A clinical score to predict acute renal failure after cardiac

bution of arrhythmic events in chronic kidney disease: highest surgery. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(1):162-168.

incidence in the long interdialytic period. Heart Rhythm. 75. Mehta RH, Grab JD, O’Brien SM, et al. Bedside tool for pre-

2015;12(10):2047-2055. dicting the risk of postoperative dialysis in patients undergoing

68. Georgianos PI, Sarafidis PA, Sinha AD, Agarwal R. Adverse cardiac surgery. Circulation. 2006;114(21):2208-2216; quiz

effects of conventional thrice-weekly hemodialysis: is it time to 2208.

avoid 3-day interdialytic intervals? Am J Nephrol. 2015;41(4- 76. Wijeysundera DN, Karkouti K, Dupuis JY, et al. Derivation and

5):400-408. validation of a simplified predictive index for renal replacement

69. Arora P, Pourafkari L, Visnjevac O, Anand EJ, Porhomayon J, therapy after cardiac surgery. JAMA. 2007;297(16):1801-

Nader ND. Preoperative serum potassium predicts the clinical 1809.

outcome after non-cardiac surgery. Clin Chem Lab Med. 77. Kheterpal S, Tremper KK, Heung M, et al. Development and

2017;55(1):145-153. validation of an acute kidney injury risk index for patients un-

70. Wahr JA, Parks R, Boisvert D, et al. Preoperative serum dergoing general surgery: results from a national data set.

potassium levels and perioperative outcomes in cardiac Anesthesiology. 2009;110(3):505-515.

AJKD Vol XX | Iss XX | Month 2019 11

You might also like

- BLS Acls Aha 2020Document103 pagesBLS Acls Aha 2020Nicholas PetrovskiNo ratings yet

- The Secret of Eternal Youth PDFDocument36 pagesThe Secret of Eternal Youth PDFArunesh A Chand100% (4)

- BX10/BX10 MB: Weighing Terminals Technical ManualDocument60 pagesBX10/BX10 MB: Weighing Terminals Technical Manualfelipezambrano50% (2)

- SKF Frecuently Questions With AnswersDocument16 pagesSKF Frecuently Questions With AnswersCarlos AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- Alkaline Phosphatase TestDocument6 pagesAlkaline Phosphatase TestShameema shami100% (1)

- 2014 Perioperative Slide SetDocument50 pages2014 Perioperative Slide SetAnonymous PcYFgC0YkNo ratings yet

- Jsa-0002 - CCTV Pipe Inspection RapidDocument8 pagesJsa-0002 - CCTV Pipe Inspection RapidMohamad AfifNo ratings yet

- Chapter III Pharmacokinetics: Durge Raj GhalanDocument64 pagesChapter III Pharmacokinetics: Durge Raj GhalanDurge Raj Ghalan100% (3)

- Engineering ManualDocument27 pagesEngineering ManualThousif Rahman67% (3)

- Renal Transplant SeminarDocument37 pagesRenal Transplant SeminarAnusha Verghese0% (1)

- Status Epilepticus, Refractory Status Epilepticus, and Super-Refractory Status EpilepticusDocument25 pagesStatus Epilepticus, Refractory Status Epilepticus, and Super-Refractory Status EpilepticusAlvaro EstupiñanNo ratings yet

- Euro TRDocument7 pagesEuro TRVianey GarciaVillegasNo ratings yet

- Bernard D. Prendergast and Pilar Tornos: Surgery For Infective Endocarditis: Who and When?Document26 pagesBernard D. Prendergast and Pilar Tornos: Surgery For Infective Endocarditis: Who and When?om mkNo ratings yet

- Perioperative Management of Patients With End-Stage Renal DiseaseDocument17 pagesPerioperative Management of Patients With End-Stage Renal DiseaseAn JNo ratings yet

- Anesthetic Challenges of Patients With Cardiac Comorbidities Undergoing Major Urologic SurgeryDocument6 pagesAnesthetic Challenges of Patients With Cardiac Comorbidities Undergoing Major Urologic Surgerysatria wibawaNo ratings yet

- Management of Common PostoperativeComplicationsDocument15 pagesManagement of Common PostoperativeComplicationsjamalNo ratings yet

- PCI or CABG, That Is The Question!: Jong Shin Woo, MD, and Weon Kim, MDDocument2 pagesPCI or CABG, That Is The Question!: Jong Shin Woo, MD, and Weon Kim, MDHeńřÿ ŁøĵæńNo ratings yet

- Postoperative Care for Patients with Cardiovascular and Renal IssuesDocument6 pagesPostoperative Care for Patients with Cardiovascular and Renal IssuesAziil LiizaNo ratings yet

- Dialysis After CABG Ejcts 2013ddDocument6 pagesDialysis After CABG Ejcts 2013ddDumitru GrozaNo ratings yet

- 37855786 Onconephrology Core Curriculum 2023Document19 pages37855786 Onconephrology Core Curriculum 2023jogutiro01No ratings yet

- 35 5 854 PDFDocument10 pages35 5 854 PDFRoni ArmandaNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 1015958415000494Document7 pagesPi Is 1015958415000494benefits35No ratings yet

- Circulation 2014 Silvain 918 22Document6 pagesCirculation 2014 Silvain 918 22aninNo ratings yet

- Ivz035Document8 pagesIvz035BEATRIZ CUBILLONo ratings yet

- The Evolving Clinical Use of Dexmedetomidine: CommentDocument3 pagesThe Evolving Clinical Use of Dexmedetomidine: CommentSerque777No ratings yet

- Risk Model DialysiddssssDocument7 pagesRisk Model DialysiddssssDumitru GrozaNo ratings yet

- Perioperative Acute Kidney Injury: Charuhas V. ThakarDocument9 pagesPerioperative Acute Kidney Injury: Charuhas V. ThakarjessicaNo ratings yet

- AKI and CRRT RelationDocument10 pagesAKI and CRRT RelationZainab MotiwalaNo ratings yet

- Paper Ar QXDocument7 pagesPaper Ar QXCristobal UrreaNo ratings yet

- The Challenge of Kidney Damage During Interventional Cardiology ProceduresDocument6 pagesThe Challenge of Kidney Damage During Interventional Cardiology ProceduresIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Renal Replacement Therapy in Acute Kidney Injury 2017Document14 pagesRenal Replacement Therapy in Acute Kidney Injury 2017piero reyes100% (1)

- TDR1Document7 pagesTDR1Santanico De CVT deozaNo ratings yet

- Antiagregação em Sca RevisãoDocument9 pagesAntiagregação em Sca RevisãoAdriana Lessa Ventura FonsecaNo ratings yet

- Renal TransplantDocument15 pagesRenal TransplantMaru LértoraNo ratings yet

- Onconephrology Kidney Disease and CancerDocument32 pagesOnconephrology Kidney Disease and CancerFreddy Shanner Chávez VásquezNo ratings yet

- 2015 Manejo Postquirurgico Del Paciente Con Cirugia Cardiaca Parte IIDocument20 pages2015 Manejo Postquirurgico Del Paciente Con Cirugia Cardiaca Parte IIAdiel OjedaNo ratings yet

- Nej MR A 1607714Document9 pagesNej MR A 1607714bagholderNo ratings yet

- Perioperative Evaluation and Management of Patients With Cirrhosis - Risk Assessment, Surgical Outcomes, and Future Directions (Newman, 2020)Document20 pagesPerioperative Evaluation and Management of Patients With Cirrhosis - Risk Assessment, Surgical Outcomes, and Future Directions (Newman, 2020)maria muñozNo ratings yet

- CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY IN THE ELDERLYDocument19 pagesCARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY IN THE ELDERLYThanh BinhNo ratings yet

- Preoperative and Postoperative Care of The Thoracic Surgery PatientDocument10 pagesPreoperative and Postoperative Care of The Thoracic Surgery PatientfebriNo ratings yet

- 828 FullDocument7 pages828 FullMayra LoeraNo ratings yet

- CKD5 HDDocument10 pagesCKD5 HDsari murnaniNo ratings yet

- Perioperative Management of Heart Transplantation A Clinical ReviewDocument18 pagesPerioperative Management of Heart Transplantation A Clinical ReviewMichael PimentelNo ratings yet

- Ehab 898Document9 pagesEhab 898Angelica Gaitan PalenciaNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument9 pagesPDFRam JeevanNo ratings yet

- Guia CIRSEDocument14 pagesGuia CIRSEjfayalaNo ratings yet

- Surgical Intervention For Peripheral Arterial DiseaseDocument15 pagesSurgical Intervention For Peripheral Arterial DiseaseDewi NurNo ratings yet

- Review Articles: Medical ProgressDocument10 pagesReview Articles: Medical ProgressMiko AkmarozaNo ratings yet

- Addendum of Newer Anticoagulants To The SIR Consensus GuidelineDocument5 pagesAddendum of Newer Anticoagulants To The SIR Consensus GuidelineCenith De Los ReyesNo ratings yet

- High Lactate Levels Are Predictors of Major Complications After Cardiac SurgeryDocument6 pagesHigh Lactate Levels Are Predictors of Major Complications After Cardiac SurgeryMuhammad RizqiNo ratings yet

- Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy - Who When WHDocument14 pagesContinuous Renal Replacement Therapy - Who When WHKrisztinaNo ratings yet

- Grant2014 PDFDocument10 pagesGrant2014 PDFRalucaNo ratings yet

- Pharmacotherapy Chap048 PDFDocument15 pagesPharmacotherapy Chap048 PDFJilani Sk UpparaNo ratings yet

- Preoperative Care of Patients With Kidney DiseaseDocument13 pagesPreoperative Care of Patients With Kidney Disease84ghmynprvNo ratings yet

- AGA Sirosis PreopDocument12 pagesAGA Sirosis PreopAlvy SyukrieNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0007091217540015Document10 pagesPi Is 0007091217540015Yoga WibowoNo ratings yet

- Articulo 1Document8 pagesArticulo 1Julio Cosme CastorenaNo ratings yet

- Case Report Peripheral Arterial Disease Vaskular 2015Document8 pagesCase Report Peripheral Arterial Disease Vaskular 2015NovrizaL SaifulNo ratings yet

- Circulationaha 107 739094Document3 pagesCirculationaha 107 739094Pruthvi RajNo ratings yet

- Detection, Evaluation, and Management of Preoperative Anaemia in The Elective Orthopaedic Surgical Patient: NATA GuidelinesDocument10 pagesDetection, Evaluation, and Management of Preoperative Anaemia in The Elective Orthopaedic Surgical Patient: NATA GuidelinesDiego Martin RabasedasNo ratings yet

- Perioperative management of patients with coronary artery disease undergoing non cardiac surgery summary of the french society of anaesthesia and intensive care medicine 2017 convention AnestCriCarePainMed 2017Document8 pagesPerioperative management of patients with coronary artery disease undergoing non cardiac surgery summary of the french society of anaesthesia and intensive care medicine 2017 convention AnestCriCarePainMed 2017RicardoNo ratings yet

- Medical Evaluation of Surgical Patient 2015049Document39 pagesMedical Evaluation of Surgical Patient 2015049Kanneaufii KaramelNo ratings yet

- IraposopemidososDocument9 pagesIraposopemidososjoseNo ratings yet

- Fifteen-Year Experience: Open Heart Surgery in Patients With End-Stage Renal FailureDocument6 pagesFifteen-Year Experience: Open Heart Surgery in Patients With End-Stage Renal FailureDavid RamirezNo ratings yet

- Clinical Review: Management of Weaning From Cardiopulmonary Bypass After Cardiac SurgeryDocument18 pagesClinical Review: Management of Weaning From Cardiopulmonary Bypass After Cardiac SurgeryAdilZyaniNo ratings yet

- J CPM 2019 02 010Document13 pagesJ CPM 2019 02 010Mohamed GoudaNo ratings yet

- Managing Coronary Artery Disease in CKD PatientsDocument4 pagesManaging Coronary Artery Disease in CKD Patientsopi neanNo ratings yet

- Perioperative β-Adrenergic Blockade in Noncardiac and Cardiac Surgery - A Clinical UpdateDocument16 pagesPerioperative β-Adrenergic Blockade in Noncardiac and Cardiac Surgery - A Clinical UpdateYelka TenelemaNo ratings yet

- Critical Care for Potential Liver Transplant CandidatesFrom EverandCritical Care for Potential Liver Transplant CandidatesDmitri BezinoverNo ratings yet

- 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS) The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Document61 pages2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS) The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)AdelaNo ratings yet

- Ehab 484Document111 pagesEhab 484aslinNo ratings yet

- Standards of Care in Diabetes - 2024: 9. Pharmacologic Approaches To Glycemic TreatmentDocument21 pagesStandards of Care in Diabetes - 2024: 9. Pharmacologic Approaches To Glycemic Treatmentm.albajilioaldin nNo ratings yet

- Delirium: Continuum Lifelong Learning Neurol 2010 16 (2) :120-134Document15 pagesDelirium: Continuum Lifelong Learning Neurol 2010 16 (2) :120-134Maria Isabel Montañez RestrepoNo ratings yet

- Ehad 195Document13 pagesEhad 195Tài LêNo ratings yet

- Management of Newly Diagnosed HIV InfectionDocument16 pagesManagement of Newly Diagnosed HIV InfectionRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- American Society of Hematology 2018 Guidelines for Management of Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis for Hospitalized and Nonhospitalized Medical PatientsDocument28 pagesAmerican Society of Hematology 2018 Guidelines for Management of Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis for Hospitalized and Nonhospitalized Medical PatientsjuanpbagurNo ratings yet

- Guias ESC para Insuficiencia Cardiaca CronicaDocument128 pagesGuias ESC para Insuficiencia Cardiaca CronicaKarla HernandezNo ratings yet

- VM in BpocDocument19 pagesVM in BpocAndreea Livia DumitrescuNo ratings yet

- DC 24 SrevDocument6 pagesDC 24 Srevm.albajilioaldin nNo ratings yet

- Exercise Stress Testing: Indications and Common QuestionsDocument8 pagesExercise Stress Testing: Indications and Common QuestionsjuanpbagurNo ratings yet

- Ehac270 PDFDocument99 pagesEhac270 PDFSandu Cristina MarilenaNo ratings yet

- Distúrbios Ácido Básicos Revisão NEJM 2014-1Document12 pagesDistúrbios Ácido Básicos Revisão NEJM 2014-1sabrinamgrNo ratings yet

- Diabetic Ketoacidosis and Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic Syndrome Review of Acute DecompensadosDocument15 pagesDiabetic Ketoacidosis and Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic Syndrome Review of Acute DecompensadosPaola Fernanda Dávila DíazNo ratings yet

- Clostridium Difficile Infection. Review. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases.Document11 pagesClostridium Difficile Infection. Review. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases.LibrosNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Compartment SyndromeDocument15 pagesAbdominal Compartment SyndromejuanpbagurNo ratings yet

- Perioperative Hyperglycemia Management: An UpdateDocument14 pagesPerioperative Hyperglycemia Management: An UpdateArif Setyo WibowoNo ratings yet

- Documento Sobre MedicinaDocument14 pagesDocumento Sobre MedicinaJuan David AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Electrocardiographic Criteria For The Diagnosis of Left Ventricular HypertrophyDocument10 pagesElectrocardiographic Criteria For The Diagnosis of Left Ventricular HypertrophyHendri SaputraNo ratings yet

- Clase Hepatitis AlcohólicaDocument10 pagesClase Hepatitis AlcohólicajuanpbagurNo ratings yet

- Clase MiocarditisDocument13 pagesClase MiocarditisjuanpbagurNo ratings yet

- Syncope Guideline ESC 2018Document69 pagesSyncope Guideline ESC 2018ddantoniusgmailNo ratings yet

- Clase 23. Neutropenia FebrilDocument17 pagesClase 23. Neutropenia FebriljuanpbagurNo ratings yet

- Clase Disección AórticaDocument149 pagesClase Disección AórticajuanpbagurNo ratings yet

- Braga Et Al 2019 Clinical Implications of Febrile Neutropenia Guidelines in The Cancer Patient PopulationDocument3 pagesBraga Et Al 2019 Clinical Implications of Febrile Neutropenia Guidelines in The Cancer Patient PopulationRafael SuzukiNo ratings yet

- Supraventricular Tachycardia: An Overview of Diagnosis and ManagementDocument5 pagesSupraventricular Tachycardia: An Overview of Diagnosis and Managementanggit23No ratings yet

- Personal LetterDocument4 pagesPersonal LetterAskme AzmyNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Dermatitis AtopikDocument20 pagesJurnal Dermatitis AtopikchintyaNo ratings yet

- Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Laboratory: Lab Session 3 Absorption Refrigeration Demonstrator 816 ObjectivesDocument10 pagesRefrigeration and Air Conditioning Laboratory: Lab Session 3 Absorption Refrigeration Demonstrator 816 Objectivesjhon milliNo ratings yet

- Jadwal Oral Presentation Peserta FIT-VIIIDocument26 pagesJadwal Oral Presentation Peserta FIT-VIIIKlinik FellitaNo ratings yet

- A Study On Satisfaction Level of Employees With Special Reference Textile IndustryDocument12 pagesA Study On Satisfaction Level of Employees With Special Reference Textile Industrysai kiran bade100% (1)

- Rakovic Dejan - Arandjelovic Slavica - Micovic Mirjana - Quantum-Informational Medicine QIM 2011 PDFDocument150 pagesRakovic Dejan - Arandjelovic Slavica - Micovic Mirjana - Quantum-Informational Medicine QIM 2011 PDFPrahovoNo ratings yet

- Exxonmobil High Density Polyethylene Product Guide: Extrusion MoldingDocument6 pagesExxonmobil High Density Polyethylene Product Guide: Extrusion MoldingDaikinllcNo ratings yet

- Formula 1480 Rub Off Mask PDFDocument1 pageFormula 1480 Rub Off Mask PDFAbdul WasayNo ratings yet

- Arthur Kleinman The Illness Narratives Suffering Healing and The Human ConditionDocument46 pagesArthur Kleinman The Illness Narratives Suffering Healing and The Human Conditionperdidalma62% (13)

- The Suitcase ProjectDocument27 pagesThe Suitcase Projectshubhamkumar9211No ratings yet

- With Reference To Relief, Drainage and Economic Importance, Explain The Differences Between The Northern Mountains and Western MountainsDocument3 pagesWith Reference To Relief, Drainage and Economic Importance, Explain The Differences Between The Northern Mountains and Western Mountainshajra chatthaNo ratings yet

- "Fish" From Gourmet RhapsodyDocument4 pages"Fish" From Gourmet RhapsodySean MattioNo ratings yet

- Volcanic Eruption Types and ProcessDocument18 pagesVolcanic Eruption Types and ProcessRosemarie Joy TanioNo ratings yet

- Product Brochure-Electronically Controlled Air Dryer-ECA PDFDocument4 pagesProduct Brochure-Electronically Controlled Air Dryer-ECA PDFAnonymous O0T8aZZNo ratings yet

- DLL G5 Q1 Week 3 All SubjectsDocument64 pagesDLL G5 Q1 Week 3 All SubjectsMary Eilleen CabralNo ratings yet

- Listing of Equipment For Network DesignDocument3 pagesListing of Equipment For Network DesignJake D La MadridNo ratings yet

- Aftercooler - Test: Shutdown SIS Previous ScreenDocument7 pagesAftercooler - Test: Shutdown SIS Previous ScreenKeron Trotz100% (1)

- Laporan FaalDocument25 pagesLaporan FaalAgnes NathaniaNo ratings yet

- Edc Power Plant FacilitiesDocument32 pagesEdc Power Plant FacilitiesMichael TayactacNo ratings yet

- Moisture Sorption Isotherms Characteristics of Food ProductsDocument10 pagesMoisture Sorption Isotherms Characteristics of Food ProductsMustapha Bello50% (2)

- Site Comp End 02Document66 pagesSite Comp End 02Parameswararao BillaNo ratings yet

- DLL - MAPEH 4 - Q4 - W8 - New@edumaymay@lauramos@angieDocument8 pagesDLL - MAPEH 4 - Q4 - W8 - New@edumaymay@lauramos@angieDonna Lyn Domdom PadriqueNo ratings yet