Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Shott 1997

Uploaded by

Aly OuedryOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Shott 1997

Uploaded by

Aly OuedryCopyright:

Available Formats

Society for American Archaeology

Stones and Shafts Redux: The Metric Discrimination of Chipped-Stone Dart and Arrow Points

Author(s): Michael J. Shott

Source: American Antiquity, Vol. 62, No. 1 (Jan., 1997), pp. 86-101

Published by: Society for American Archaeology

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/282380 .

Accessed: 20/06/2014 16:50

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Society for American Archaeology is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

American Antiquity.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 16:50:06 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

STONES AND SHAFTS REDUX: THE METRIC DISCRIMINATION OF

CHIPPED-STONE DART AND ARROW POINTS

Michael J. Shott

MAany of the chipped-stonebifaces so common in the archaeological recordfunctioned as the haftedpoints of darts or arrows.

For archaeologists, these artifacts possess two salient properties: (1) theyformed only part of a larger apparatus, but, (2)

because perishables decompose, they ordinarily are the only part preserved. Consequently,the identity of that apparatus-

i.e., whetherdart or arrow-is not readily apparent. For various reasons, we may wish to know if stone bifacesfunctioned as

dart or arrow points. Often we rely on reasonable assumptions, but Thomass (1978) discriminantanalysis isis a more reliable

way to distinguish the possibilities. This study extends Thomass approach by increasing the dart sample and the rate of suc-

cessful classification. Shoulder width is the most importantdiscriminating variable.An independenttest on a set of arrows

,lso strengthensconfidence in the results.

AJuchosde los bifaces liticos encontradosen el registro arqueologicofuncionaron como puntas enmangadas de dardos ofle-

chas. Talesartefactos poseen dos propiedades salientes: (1) conformaronsolamenteparte del instrumentomds grande; pero,

(2) porque lo perecedero se descompone, a menudoson la iunicaparte preservada. Por lo tanto, la identidad del instrumento,

ya sea dardo oflecha, no se puede precisar. Por varias razones, quisieramossaber si los bifaces funcionaron como dardos o

flechas. A menudo, contamos con suposiciones justas, pero el andlisis discriminante de Thomas (1978) es un modo mds

seguro para distinguir las opciones. Este estudio amplifica su estrategia mediante una muestraperteneciente de dardos mds

grande y una tasa de su clasificacion mds alta. El ancho del hombrosurge como variable mds importante.Una prueba inde-

pendente en una colecion deflechas procedente de la Gran Cuenca de los Estados Unidos tambienfortalece la confianza en

los resultados.

From the earliest accounts in New Spain to plete and wholesale? Although such questions

Hollywood's Golden Age, few items are as may seem unenlightening(Larralde1990:100) or

central to their tradition-bound popular even tiresome (Corliss 1980), they bear on

image as Native Americans'bows and arrows.Yet important theoretical issues. Conventional

archaeologistsbelieve thatthe earliestAmericans assumptionsof the bow and arrow'ssuperioreffi-

did not use them, the bow and arrow being a ciency in hunting are doubtful (Larralde 1990;

comparatively recent innovation that replaced Shott 1993:435-438); other explanations invoke

earlier dart technology and spread across North political incentives and consequences (Blitz

America from an arctic source. Most locate the 1988; Maschner 1991; Shott 1996) or, from Old

replacement in the first millennium A.D. (Beck Worldperspectives,the social dimensions of dart

i995; Blitz 1988; Christenson 1986; Hall 1977; (Cundy 1989:17-18; Rose 1960:238-242; Testart

Shott 1993; Troeng 1993). Everyone knows what 1988:11) and arrow technology (Edmonds and

bows and arrows are; darts are weapons with Thomas 1987; Vinnicombe 1972:201-202).

longer shafts, usually with foreshafts as well, Darts may not have been abandoned at once

propelledby a device known as an atlatl, sling, or when the bow and arrowappeared(Chatterset al.

spear-thrower.The last term in particular is a 1995; Heizer 1938; Larralde 1990:6; Massey

misnomer (Perkins 1992:65), and "atlatl"is used 1961; Shott 1996), but the timing of their proba-

here for consistency. The broad archaeological bly gradual abandonmentbears on the persis-

consensus begs importantquestions: how, why, tence of atlatls in ritual contexts and the rate at

and exactly when did the bow and arrow replace which their formalattributeswere alteredin sym-

earliertechnology,and was the replacementcom- bolic representation(Hall 1977).

Michael J. Shott * Departmentof Sociology and Anthropology,Universityof NorthernIowa,CedarFalls, IA 50614-0513

AmericanAntiquity,62(1), 1997, pp. 86-101.

Copyright? by the Society for AmericanArchaeology

86

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 16:50:06 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Shott] METRICDISCRIMINATION

OF CHIPPED-STONEPOINTS 87

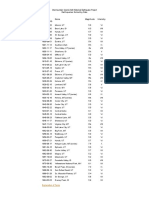

Table 1. PreviouslyUnanalyzedDartPoints Used in the Study.

mm

Max. Thick- Neck Published

CatalogNo.a Length Width ness Width Provenience Source Museum

349188 41.1 17.4 3.4 8.3 White Dog Cave,Arizona Guernsey & Kidder 1921 SI

11/7254 35.8 24.2 7.2 15.3 Allred Shelter,Missouri Harrington1960 NMAI

D2429 81.7 20.1 6.4 21.9 Kimberley,NW Australia PM

97179 21.8 14.0 2.9 9.8 SteamboatCave, New Mexico Cosgrove 1947 PM

97179 39.5 20.5 4.3 11.2 SteamboatCave, New Mexico Cosgrove 1947 PM

A4515-1/6 55.8 22.6 4.2 13.6 Cave 2, San JuanCounty,Utah Woodward1930 LACMNH

A4515-1/7 70.4 20.0 4.2 14.9 Cave 2, San JuanCounty,Utah Woodward1930 LACMNH

A4515-1/8 60.4 20.2 4.0 13.9 Cave 2, San JuanCounty,Utah Woodward1930 LACMNH

A4515-1/9 54.1 20.3 4.9 15.3 Cave 2, San JuanCounty,Utah Woodward1930 LACMNH

A4515-1/10 60.4 20.5 4.6 10.4 Cave 2, San JuanCounty,Utah Woodward1930 LACMNH

A4515-1/11 60.7 24.9 4.5 18.8 Cave 2, San JuanCounty,Utah Woodward1930 LACMNH

A4515.30-47 34.3 20.4 4.8 13.4 Cave 2, San JuanCounty,Utah Woodward1930 LACMNH

A4515.30-48 26.5 23.7 5.2 16.7 Cave 2, San JuanCounty,Utah Woodward1930 LACMNH

NA-7031 42.3 16.2 5.4 11.4 Point Barrow,Alaska UMUP

SA-3758 38.0 18.0 5.0 16.5 Nazca vicinity, Peru UMUP

P29-30.4G1 44.1 24.0 5.2 17.5 Sand Dune Cave, Utah Lindsayet al. 1968 MNA

P29-30.4G2 54.6 27.5 4.8 15.6 Sand Dune Cave, Utah Lindsayet al. 1968 MNA

P29-30.4G3 49.2 24.6 5.7 19.1 Sand Dune Cave, Utah Lindsayet al. 1968 MNA

P29-30.4G4 48.5 17.4 4.6 13.3 Sand Dune Cave, Utah Lindsayet al. 1968 MNA

P29-30.4G5 57.4 23.4 5.4 17.7 Sand Dune Cave, Utah Lindsayet al. 1968 MNA

P29-30.4G6 63.0 23.1 5.1 19.1 Sand Dune Cave, Utah Lindsayet al. 1968 MNA

66.56.3.3 57.2 27.4 4.0 17.9 San JuanCounty,Utah Montgomery1894 BYUb

66.55.3.3 58.8 28.0 5.5 18.2 San JuanCounty,Utah Montgomery1894 BYU

66.56.5.1 60.4 30.0 5.8 19.2 San JuanCounty,Utah Montgomery1894 BYU

66.55.3.1 52.8 27.5 5.1 17.4 San JuanCounty,Utah Montgomery1894 BYU

66.56.3.1 85.3 32.0 5.8 19.3 San JuanCounty,Utah Montgomery1894 BYU

66.55.3.2 66.5 28.4 5.0 13.8 San JuanCounty,Utah Montgomery1894 BYU

66.56.5.2 67.1 29.7 5.5 19.9 San JuanCounty,Utah Montgomery1894 BYU

95.2.147.1 48.9 22.5 5.5 12.5 San JuanCounty,Utah Montgomery1894 BYU

95.2.115.1 61.3 24.6 6.0 16.8 San JuanCounty,Utah Montgomery1894 BYU

BYU=BrighamYoungUniversityMuseum of Peoples and Culture LACMNH=LosAngeles CountyMuseumof NaturalHistory

MNA-Museum of NorthernArizona NMAI=NationalMuseum of the American Indian PM=PeabodyMuseum SBCM=San

BernardinoCountyMuseum SI=SmithsonianInstitution UMUP=UniversityMuseum,Universityof Pennsylvania.

aSee Thomas (1978:Table3) for additionaldata.

bSpecimenswere taken in the 1890s from one or more caves located between Moab and Bluff City (Montgomery 1894:227).

Montgomery(1894:227--230)reportedspecimens from several caves, including "a number"from one burial in Cave No. 1 and

six from anotherburial there. He (1894:227) identified all as "crude,stone arrow-pointswith short, wooden . . . handles,"but

Pepper's(1905) account and direct examinationleave no doubt that the specimens were dart points. Pepper (1905:127-129)

described 13 specimens from Cave No. 1 or "CaveDwelling," only nine of which were received by BYU from the Deseret

Museum,where the collection originallywas housed.

Poor preservation often forces us to seek Nusbaum (1922:126) long ago proposed such

answers from the only remaining component of a method,but Thomas (1978) was the first to use

prehistoric weapons, their stone points. Under it. He summarized earlier attempts (see also

these circumstances, we can distinguish darts Chatterset al. 1995, Christenson1986) to distin-

from arrowsonly by the size and form of the pre- guish dartsfrom arrowson the basis of attributes

served stone point. Too often the distinction is such as weight and neck width (Thomas

made by assumption (Christenson 1986; Shott 1978:461). Thomas also noted experiments

1993), which can be reasonabledependingon cir- demonstratingthat arrowspossessing large points

cumstances. But there are better ways to distin- and dartspossessing small ones could fly. But he

guish dart from arrow,and therebyto addressthe recognized that the more importantquestion was

importantquestionsposed above. an empirical one: "what existentially is, rather

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 16:50:06 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

88 AMERICAN ANTIQUITY [Vol. 62, No. 1, 1997

than what theoretically could be" (Thomas filled with specimens acquiredbefore the advent

1978:466 [emphasisin original];see also Fenenga of rigorous standardsregardingthe provenience

1953:319). He then examinedmuseumspecimens and documentation of collections. The market

known to be dart or arrow points because they spawnedby avid collectors may have encouraged

still were hafted to dartor arrow(fore)shafts.His the fabricationof specimens not necessarilytypi-

discriminant analysis produced encouraging cal-in manufacture,size and form, decoration,

results; good metric discrimination of the two manner of use-of those in common use by the

point types was obtained, and virtually all 132 cultureto which specimens are attributed(Cundy

arrowswere identified correctlyby the resulting 1989:76; see DeBoer 1985 for examples in pot-

classification functions (Thomas 1978). In addi- tery). For instance, several University of

tion, seven of 10 dartswere identified correctly. Pennsylvaniaspecimens may consist of archaeo-

Thomas's study was a valuable start marred logical bifaces hafted to then-modem shafts or

only by the "painfully small" (1978:468) dart foreshafts (J. Cotter, personal communication

sample of 10 specimens. Fortunately,various 1994). Second, authentic archaeological speci-

museums hold darts with hafted stone points. mens can be of unknownfunction. Several from

Visits to 11 of them between 1990 and 1995 PgHb at the CanadianMuseum of Civilization,

increasedthe sample from 10 to 39. Even this fig- for example,bore stemmedchertbifaces haftedto

ure is modest, but stone points hafted to dart crude short split shafts roughlythe length of fore-

shafts or foreshafts are comparatively rare. shafts.These certainlyresembledartpoints found

Althoughmany museumshold one or a few spec- elsewhere but, unlike other specimens, their

imens, it is unlikely that the compiled data could shafts were flatterin cross section than the circu-

be substantiallyincreasedby visits to more North lar to slightly elliptical form found on virtuallyall

Americanmuseums. Metric attributesand prove- demonstrabledart shafts elsewhere. In one case

nience of these specimens are listed by museum (cat. no. 14474c) a flake was hafted laterallyin a

in Table 1.1 slot at the end opposite the biface, while another

No point and foreshaftwas found haftedto the (cat. no. 14112a) bore bifaces at both ends of the

largerdartshaft on which it presumablywas used. handle. These specimens could in fact be darts,

Strictly speaking, then, I assume that they func- althoughit is hardto imagine how they were used

tioned on dartsas opposed, for instance, to being as such. They were not included in the analysis.

used handheld as knives. But ethnographic Third, authentic projectiles can be launched by

sources (e.g., Nelson 1899) routinely report the atlatls (i.e., genuine darts), be launchedby hand

use of points hafted to foreshafts as detachable (i.e., spears), or be held in the hand and used by

elements of darts, and no known source reports thrusting(i.e., lances or hand-held spears). Most

tools of this natureused as handheldknives. The ethnographicspecimens lack the associateddocu-

dart foreshafts found on Table 1 specimens usu- mentation that could distinguish these alterna-

ally are tapered,have circularor slightly elliptical tives, althoughSmithsonianInstitutionspecimens

cross sections, and always are more finely made in particularoften are well documented ethno-

than the broader handles, often flatter in cross graphically (e.g., Nelson 1899). Lacking docu-

section, found on knife handles (e.g., Fowler and mentation, specimens cannot be identified

Matley 1979; Nelson 1899; note also the speci- reliablyby function,and the performancerequire-

mens from Canada'sPgHbl site describedin the ments of the variousalternativescan differ signif-

following paragraph). Also, knives rarely are icantly in ways that register in size and form of

found in sets of four or more, while dartshafted the point (Cundy 1989). Fourth, even weapons

to foreshafts often are. General cutting purposes launchedby atlatl may differ in context and man-

rarelyrequiredthe use of severalspecimensat one ner of use in ways that bear on the size and form

time, whereas dart points routinely were carried of their points. Thomas (1978:468), for instance,

in sets for the rapidrearmingof a single shaft. cautionedagainstthe facile equationof dartsused

Forseveralreasons,even the expandeddataset in terrestrialvs. marinesettings.The diversityand

demands critical treatment.First, museums are complexity of marine hunting equipmentindeed

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 16:50:06 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Shott] METRICDISCRIMINATION

OF CHIPPED-STONEPOINTS 89

are remarkable(e.g., Nelson 1899). Harpoonsare authentic; and (4) they were not known to be

used commonly in marinehabitats,and handheld designed for use in marine hunting.Table 1 lists

spears and lances also seem to be more common the specimens that satisfy these conditions.

there than elsewhere. Especially in the North This data set is less than ideally representative

Americanarctic, coastal settings also were popu- of the complete time and space range of dartuse.

lar among ethnographic collectors, such that Most specimens are archaeological, which is

museum collections like those in Washingtonand unavoidableconsideringthe limiteduse of dartsin

Ottawa disproportionately contain marine the ethnographicpast (Massey 1961). Most are

weapons. Thomas's point is well taken, and from the American Southwest, equally unavoid-

weapons used in marinesettings can be used only able consideringthe vagariesof organicpreserva-

with care. (For this reason, 11 Field Museum of tion; southeastern Utah is especially well

Natural History archaeological specimens from represented.But perfect representativenessis a

coastal Peruwere omittedbecause they are hafted chimera,and we must, for reasons set forth else-

as harpoon, not dart, points.) Fifth, many speci- where (Shott 1993:430-431), use all the evidence

mens are tightly bound in sinew lashing or mastic thatprudentbut criticaltreatmentmakesavailable.

(e.g., sizable collections of AustralianKimberley Not surprisingly,arrow points generally are

darts at the Field Museum and the Harvard's smaller than dartpoints. It is temptingto remove

Peabody Museum), making it difficult if not large outliers from the arrow data set, and there

impossible to measure attributes of the stem are good reasons to consider such a move.

because it is obscured by hafting. The sole "Unlocalized"stone-tippedarrows, for instance,

Kimberley point included in the study (Table 1) may not be authentic. The Menomini arrows

could be measuredin its entirety only because it reported by Skinner (1921 :Figure 57) are con-

had come loose from its mastic haft, although it spicuous metric outliers (cases 12 and 38 in

fit snugly when reinserted.In his study,Thomas Figure 1). Thomas'sMenomini specimens appar-

(1978:467) avoided this problem by x-raying ently are ethnographic,perhaps acquired for the

specimens, a measurethat, if used systematically, AmericanMuseum of NaturalHistoryby Skinner

would add many specimens to the database.2 himself (1921:19), although not necessarily the

Sixth, some specimens were found that were not ones illustratedin Skinner'smonograph.Yet the

hafted to shafts or foreshafts, but retained sinew Menomini abandonedstoneworkinglong before

lashing and/or resin adhesive on their haft ele- ethnographic study (Hoffman 1896:256, 274,

ments, e.g., Newberry Cave specimens housed at 281; Skinner 1921:323), which suggests that the

California's San Bernardino County Museum tools were fashioned for donation or sale to col-

(Davis and Smith 1981:Figures 6g,f, and 7d), lectors. Indeed, Skinner describedthe making of

Shinner Site C cache (Hattori 1982:Figure then-modem arrows using stone points retrieved

44c-f,i). These archaeological specimens were from archaeologicaldeposits and hafted to mod-

found in dry caves that also yielded abundantper- ern shafts using "instructions received in a

ishable remains of atlatls (e.g., Davis and Smith dream" (1921:323). Doubts can be entertained

1981:38-53). Unfortunately, the stone points aboutthe authenticityof such arrows,but they are

were not found attached to dart shafts or fore- provisionallyretainedfor analysis.

shafts; although perishable remains of bow and

arroware rareif not absent at these sites, the dis- Metric Analysis

embodiedpoints can be identified as dartsonly by This study uses Thomas's arrow-pointdata, so

an assumptionthatthis and an earlierstudy (Shott thereis no need to repeathis analysiswhere it per-

1993) are at pains to avoid. tained to arrows only. For completeness,

An uncritical approach easily could increase Thomas's analysis of darts alone is reproduced

the possible dart sample to 75 or more. But this below using the newly expanded data set,

analysis includes specimens only if: (1) they were althoughThomas's arrow statistics differ slightly

hafted to a shaft or foreshaft; (2) all attributes from those reported here. Thomas (1978:469)

could be measured; (3) they were undoubtedly reporteda significant differencein dartand arrow

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 16:50:06 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

90 AMERICAN ANTIQUITY [Vol. 62, No. 1, 1997

S

H

80U *80.? 0 *38

.12 U 30 20812 i

L L

E 60 D

E 53, 67

N

G R 20

T 40

H W

I

D 10-

T

H

20

0-

132 39 132 39

la ARROW DART lb ARROW DART

112 30

110 *12

T 038 N

H 8 E o12

020 C 20 038

I

C 055 K

K 6

N W

E I I

S 4 D

S T 10

H I l

2- I

OA' 0

132 39 132 39

1c ARROW DART 1d ARROW DART

Figure 1. Boxplots of arrow and dart variables.

foreshaftdiameters,and thatdifferencepersists in Thomas's very small dart sample probably

this data set. explains his results. On available evidence, there

n Mean S.D. are modest positive correlations between dart-

Arrow foreshaft 132 7.30 mm 1.45 point attributesand foreshaftdiameter.

Dart foreshaft 32 10.89 mm 1.56

Discriminant Analysis

t = 12.39,df= 162,p = .00

Thomas'smost significant contributionwas a dis-

Thomasalso calculatedthe correlationbetween criminant analysis that used length, width

dart-pointmetrics and dart-foreshaftlength and (assumed to be shoulder width in this study),

diameter.The expandeddata set does not include thickness, and neck width to distinguish arrow

foreshaftlength, but the curious if small negative and dartpoints. The newly expandeddata set fur-

correlationsfoundin Thomas'soriginaldatavanish nishes an opportunity to repeat that analysis.

on reanalysis,as Pearson'sr coefficients demon- Other variables also may help distinguish dart

strate (there are equally significant correlations from arrow(Hughes 1995), and their significance

betweenthese variablesin the arrowdata): will be studied in futureresearch.

Point ForeshaftDiameter Discriminant analysis assumes: (1) the exis-

Length .44 (p =.01) tence of discrete classes; (2) multivariatenormal

Shoulder width .40 (p= .02) distributionsof variables within classes; and (3)

Thickness .45 (p .01) equal covariance matrices between groups

Neck width .38 (p = .03) (Baxter 1993:185-191; Klecka 1975:9-16). In

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 16:50:06 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Shott] METRIC DISCRIMINATION OF CHIPPED-STONE POINTS 91

ARROWS DARTS

50-

Std. Dev = 3.91

Mean = 14.7

40 * N =132

30.

20

10

.. . . . .

10 14 18 22 26 30

2a WIDTH 2b WIDTH

Figure 2. Histograms of shoulder width.

this case, the first assumptionis completely valid. 1.0 for most arrowvariables(Table 2, Figure 1).

The second is unimportantif analysis is descrip- Removal of the two Menomini extreme outliers

tive only (Baxter 1993:188) but must be evaluated noted above reduces arrowskewness to below 1.0

when results are extended beyond the analyzed except for shoulder width. Normal plots and

cases. Results are robust under "mild skewness" Lilliefors tests (Norusis 1993:190) also demon-

(Baxter 1993:197; see also Klecka 1975:10) but stratethe normalityof dartvariables.Only length

can be sensitive to highly skewed distributions. among arrow variables tests as normal; again,

Technically,multivariatenormality requires nor- removing Menomini outliers produces normality

mal distributionsfor each variable around fixed in arrow variables except for shoulder width.

values of all others (Klecka 1975:10). The Thus, the assumptionof multivariatenormalityis

assumptionis evaluatedhere instead by examin- validated for darts and validated for arrow vari-

ing each variable's separate distribution. ables except shoulderwidth only with the removal

Skewness is modest for dart points, but exceeds of outliers. Figure 2 shows the distribution of

shoulderwidth for arrowsand darts.Box's M tests

Table2. Mean MetricAttributesof the for the violation of the thirdassumption,although

Arrow and Dart Samples.

it can exaggerate the probability of significant

Attribute Mean S.D. S.E. Skewness Kurtosis inequalityat large sample sizes and is sensitive to

Arrows(n = 132) skewed data (Baxter 1993:199).

Length 31.1 9.3 .8 1.0 3.1 It is importantthat any difference in results

Shoulderwidth 14.7 3.9 .3 1.7 4.4 fromThomas'sowes to the additionaldata,not the

Thickness 4.0 1.3 .1 1.4 4.1

Neck width 10.0 .2

analyticalmethods used. To ensure close similar-

2.9 .9 1.5

ity to Thomas's methods, therefore, his results

Arrows (less Menominioutliers)(n = 130) first were reproduced in relevant particulars.

Length 30.6 8.3 .7 .3 -.2 Thomas (1978:469) apparently used stepwise

Shoulderwidth 14.4 3.4 .3 1.2 2.3 variable entry, a practice that Baxter (1994)

Thickness 3.9 1.1 .1 .7 1.0

Neck width 9.8

recently suggested could bias results. Using the

2.6 .2 .5 -.2

same method, Thomas's result was indeed repli-

Darts(n = 39) cated in most particularsincluding Box's M sta-

Length 51.7 14.0 2.2 .1 .0 tistic, discriminant-function and

Shoulderwidth 23.1 4.6 .7 .0 -.9 classification-function coefficients, and classifi-

Thickness 5.0 1.0 .2 .1 .1 cation results.Functionconstantsdifferedslightly

Neck width 15.2 3.3 .5 -.2 -.8

from Thomas (1978:470), each being approxi-

Note. All dimensions in mm.

mately .7 higher in value. This difference did not

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 16:50:06 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

0

92 AMERICAN ANTIQUITY [Vol. 62, No. 1, 1997

LENGTHVS. SHOULDER WIDTH NECK WIDTHVS. SHOULDER WIDTH

FOUR -VARIABLESECTION THREE-VARIABLESOLUTION

30-

* DART * DART

o ARROW o ARROW

80

8 I 20. ' S%,

- 60 % I.

a mg S* *

*

z * * * a ,b * i0 &

w

-i a00 *

40

0 6 zz

03 0

20 0 00

Or f * _ __

V"

10S 20 3o 40 10 20 30 40

3a SHOULDER

WIDTH 3b SHOULDER WIDTH

THICKNESS

VS. SHOULDERWIDTH

TWO-VARIABLESECTION

u)

z

'i

I-

3c SHOULDER WIDTH

Figure 3. Cross-plots of most important variable pairs in discriminant analysis.

alterany classification results. Simultaneousvari- actual rate of correct classification (Baxter

able entryproducednearlyidenticalresults in rel- 1993:187).

evant particulars, including exactly the same

classification results. Results

Consequently, analysis in this study was by All variablesenteredin analysis are important,to

simultaneousvariableentry,to avoid the interpre- judge from the attained significance of Wilk's

tive problems that attend stepwise entry (Baxter lambdastatistics(Table3). Box's M indicatesviola-

1994). Prior probabilitieswere set at .5 for both tion of the assumptionof equalcovariancematrices.

dartand arrow,and analysis was performedusing Baxter (1993) suggested the inspection of cross-

within-groupcovariancematrices. Unfortunately, plots of the most significant discriminant-analysis

classification was carried out without cross-vali- variablesto evaluatethe equal-covarianceassump-

dation, which is unavailable in the version of tion. When valid, the "groupsmay have different

SPSS (StatisticalPackagefor the Social Sciences) meansbut areotherwiseof similargeometricalsize

used (Norusis 1993), and so may exaggerate the andshapein multivariatespace"(Baxter1993:197).

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 16:50:06 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Shott] METRICDISCRIMINATION

OF CHIPPED-STONEPOINTS 93

Table3. Summaryof AnalyticalResults.

ClassificationResults

Shoulder Thick- Neck Arrows Darts

Length Width ness Width Correct Incorrect Correct Incorrect

Four-variablesolution (Box's M=47.3, p=.000)

Coefficient .51 .67 -.30 .09 118 14 30 9

Wilk'sX .59 .57 .89 .64

(.00) (.00) (.00) (.00)

Three-variablesolution (Box's M=21.1, p=.002)

Coefficient .85 -.05 .21 118 12 33 6

Wilk'sX .50 .85 .59

(.00) (.00) (.00)

Two-variablesolution (Box's M=8.4, p=.04)

Coefficient -1.00 -.003 -116 14 33 6

Wilk'sX -.50 .85

(.00) (.00)

Note: Coefficient is the discriminant-functioncoefficient

Four-Variable Solution William Farabeeexpedition.Farabee'snotes iden-

tify it as the sole intactpoint in a set of "8 or 10"

The four-variablesolution is dominatedby shoul- arrow points. There is no doubt, however, of its

der width and length; Figure 3a shows modest status as a dartpoint; SA-3758 was found with a

separationbetween dart and arrow and the sepa- "throwingstick" or atlatl, and its main shaft is

rate distributionsare roughly similar in size and recessedat the unfletchedproximalend for seating

shape (admittedly, dart length is more variable on the atlatl spur. The foreshaft is wooden. The

than arrowlength) despite the Box's M value. main shaft, however, is composed of reed rather

Overall, the analysis successfully classifies than solid wood, much more common in arrows

86.5 percentof cases, but only 76.9 percent(30 of than darts, and the assembled piece measures

39) of darts. The latter figure only slightly roughly 400 mm in length, more in the range of

exceeds Thomas's (1978) 70 percent rate. (The arrows than darts. SA-3758 unquestionablyis a

same results are obtainedusing Thomas'soriginal dart point, but its size and design imply strong

function to classify the darts in this sample.) The continuitiesbetween dartand arrowtechnologies,

nine misclassified dart points include three from an observation consistent with other studies

Arizona'sWhite Dog Cave. Their identity as dart (Cundy 1989; Hughes 1995; Perkins1992).

points is beyond question (Guernsey and Kidder Classification functions from this analysis are

1921:Plate 34). Interestingly, Guernsey and Dart:.18(length)+ .87(shoulder width)+ .72(thick-

Kidder (1921:86) noted that White Dog Cave ness) + .21(neck width) - 18.79

specimens are smaller than those from San Juan Arrow: .07(length) + .49(shoulder width) +

County, Utah, reported by Montgomery (1894) 1.28(thickness)+ .14(neckwidth)- 8.60

and Pepper (1905) and also analyzed here. At From standardized function coefficients,

least one White Dog Cave specimen is only a par- shoulder width is the most significant discrimi-

tially worked flake ratherthan a complete biface nating variable followed by length, thickness

(Guernseyand Kidder 1921:Plate34g). (sign of the coefficient is irrelevantto its signifi-

Specimen SA-3758 from Pennsylvania's cance [Klecka 1975:30]), and neck width (Table

UniversityMuseum also is misclassified. It bears 3). The D-score histogram(Figure4a) shows that

an obsidian point and is among the smallest dart arrowpoints form a reasonablydiscrete class but

points in the sample. SA-3758 was recoverednear that darts are somewhatmore dispersed.There is

Nazca, Peru, in the University Museum's 1922 considerableoverlapbetween the classes.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 16:50:06 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

94 AMERICAN ANTIQUITY [Vol. 62, No. 1, 1997

Three-VariableSolution tool use. Its higher rate of successful classifica-

tion, especially of darts, makes it more suitable

All else equal, the ideal solution uses the fewest than the first analysis and Thomas'soriginal one.

significantvariables(Baxter 1993:209).The four-

Two-VariableSolution

variablesolution producesadequateresults,but it

is worth considering the possibility that fewer Neck width is unlikely to be affected by resharp-

variablesalso produceacceptableresults. ening but can be problematicfor a differentrea-

Length undeniablyis importantbut it is prob- son. All the arrowpoints used in Thomas'sstudy

lematic as well because points often experienced are side-notched,a form common to most ethno-

resharpeningduringtheir use lives. This practice graphic collections (e.g., Fowler and Matley

could reducemetricattributeslike shoulderwidth, 1979) and archaeological ones from western

but length is by far the most susceptibleto reduc- North America. In eastern North America and

tion (Larralde1990:62-65;Lorentzen1989:14-17; elsewhere, by contrast, what we commonly

Shott 1993:434; Thomas 1981:14-15). Also, assume to be arrow points often are unnotched.

archaeologicalspecimensoften arebrokenbut oth- Many such specimens bear inflections on their

erwise retainmeasurableattributes.With due cau- marginsas design attributesor thatmarkthe prox-

tion, they can be classifiedjust as intactspecimens imal extent of resharpening (e.g., Shott

can. Therefore,analysis was conducteda second 1993:Figure2), but some do not. Classification

time using only shoulder width, thickness, and functions are package deals; one cannot obtain

neck width as discriminatingvariables. valid resultssimply by failing to insertneck width

All three variables are importantcontributors values in them. This quality makes it difficult to

to the result, although thickness has a low stan- apply Thomas's classification functions to

dardized coefficient (Table 3). Again, Box's M unnotchedspecimens.

indicates violation of the equal-covariance Therefore,analysiswas performeda thirdtime

assumption,yet there is good separationbetween using only shoulder width and thickness (Table

classes in the cross-plot of shoulder width and 3). Again, the Menomini outliers were omitted.

neck width, and they are similarin size and shape Wilk's X values show that both variables con-

(Figure 3b). The successful classification rate, tribute significantly to the solution, although

89.4 percent,is slightly higher overall than in the shoulder width is much more important. The

first analysis, and the rate for darts, 84.6 percent Box's M value does not unequivocally indicate

(33 of 39), is considerablyhigher. Five of the six violation of the equal-covarianceassumption;the

misclassified dart points are similarly misclassi- two variablesare modestly separatedand roughly

fied in the four-variablesolution; the sixth is the similar in size and shape (Figure 3c). As in the

smallest, especially the narrowest, of the Sand three-variablesolution, 84.6 percent of darts are

Dune Cave specimens (Table 1; Lindsay et al. classified accurately,althoughthe overall success

1968:Figure42e). rate of 88.2 percentis slightly lower.The same six

Using these results,classification functionsare darts are misclassified as in the three-variable

Dart: 1.24(shoulderwidth) + 1.94(thickness)+ solution. Classification functionsare

.38(neck width) - 22.7 Dart: 1.42(shoulder width) + 2.16(thickness) -

Arrow: .69(shoulder width) + 2.05(thickness) + 22.50

.19(neck width) - 10.7 Arrow:.79(shoulderwidth) + 2.17(thickness)-

Standardized function coefficients identify 10.60

shoulderwidth as by far the strongestcontributor The D-score histogram(Figure4c) is similarto

to results, followed distantly by neck width and those for the four-andthree-variablesolutions but

thickness (Table3). A D-score histogram(Figure suggests greater separation between darts and

4b) resemblesthatproducedin the first analysis. arrows.

This solution is especially significant because

One- Variable Solution

it omitted extreme outliers among arrowsas well

as the variablemost susceptibleto change during Standardized coefficients in the two-variable

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 16:50:06 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Shott] METRICDISCRIMINATION

OF CHIPPED-STONEPOINTS 95

solution clearly identify shoulderwidth as much width, and 81 of the 83 Numa points (97.6 per-

more importantthan thickness. When it alone is cent) are correctlyclassified by them. One of the

entered in analysis using the same data as in the two misclassified specimens (Fowler and Matley

three- and two-variablesolutions, similar results 1979:Appendix Table 1, Figure 51e [cat. no.

occur. 14540/5]) bears a strong resemblance to Ohio

Box's M yields insignificant results. Valley bifaces identified as dartpoints in an ear-

Classificationresults by specimen and overall are lier study (Shott 1993:433).

identicalto the three-variablesolution.The classi- As a very inadequatetest for dart points, the

fication functions are: partial metrics for a hafted dart from southern

Dart: 1.40(shoulderwidth) - 16.85 Nevada (Tuohy1982:85, Figure2) can be inserted

Arrow:.89(shoulder width)- 7.22. in the one- and two-variablesolutions. Both cor-

The D-score histogram resembles those for rectly classify the specimen as a dart point.

other solutions (Figure4d). Gunnerson (1969:101) reported width for two

The two- and one-variable solutions may be hafted darts;insertedin the one-variablesolution,

the most importantfor prediction. They include these too are classified correctly.

shoulder width, which consistently is the most

important contributor to results as it was in Problematics of Distinguishing Dart from

Thomas'sanalysis.The equal-covarianceassump- Arrow Points

tion is more reasonablein these cases, and their As Thomas (1978) noted, the size difference

successful classification rate matches the three- between dart and arrow points is an empirical

variable solution and exceeds the four-variable more than a theoreticalmatter.Small points could

one. Moreover,these solutions remove length and be used on darts,large ones on arrows.The possi-

neck width and so apply to many more archaeo- bility is exemplified in an earlier study (Shott

logical specimens. They can be applied to 1993:433) and in the persistentmisclassification

unnotched specimens and to broken ones that of some darts and arrows.It also is illustratedin

retain attributesexcept for length. Together,these GreatPlains data (Larralde1990) and a hafted

by

qualities make the solutions applicable to many dart point from Danger Cave (Jennings

more archaeological specimens than do the oth- 1957:Figure163e) examinedat the Utah Museum

ers. The only reservation is that arrow-point of NaturalHistory.This specimenbearsa massive

shoulder width is not distributed normally, an impact fractureoriginatingat the tip, so neither

inconvenient fact that must be assumed not to original length nor shoulder width can be mea-

prejudiceresults. sured. However, its neck and base width- 11.6

and 16.1 mm, respectively-are relativelynarrow.

Independent Tests Indeed, Jennings (1957:182-183) would have

Cross-validationof classification resultsis prefer- classified the point as an arrow had it not been

able to the resubstitution used in this study hafted to a dartforeshaft.

(Baxter 1993:201). In partialredressof this defi- Specimen SA-3758 is one of the misclassified

ciency, an independentsample of arrowpoints is darts.Besides its point, SA-3758's shaft composi-

classified to test the results. Even this measureis tion, size, and design strongly

suggest continu-

less than ideal, because arrowpoints are success- ities betweendartand arrow

technology remarked

fully classified at consistentlyhigh rates;it would on in other studies (Cundy 1989; Perkins 1992).

be betterto classify an independentdartsample if With such continuity, discriminant

analysis will

such existed. supplyhigh probabilitiesin identification,but not

Nevertheless, ethnographicGreatBasin Numa certainty.

arrowshoused at the SmithsonianInstitutionfur- Dartpoints may be similarin size to the points

nish the test. Fowler and Matley (1979:Appendix of harpoons and thrown and handheld

spears. A

Table 1) reportedlength, width, and thickness,but logical next step in

analysis is to compile suffi-

not neck width, for 83 stone arrow points. The cient data on these latter classes to

attempttheir

one- and two-variablesolutions do not use neck metric discriminationfrom both arrowsand darts.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 16:50:06 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

96 AMERICAN ANTIQUITY [Vol. 62, No. 1, 1997

20

F 111

r 15 111

e 1111

q 11111

u 11111

e 10o 11211

n 11111

c 1111111

y 11111111 1

1 1111111111

11111111111111 11 1

Iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiill 11 1 1 I

---7 Ix .. I

tI

/I/ ouI

out -4X

-4.0 -2.0 .0 2.0 4.0 out

Class 1111111111111111111111111111111111222222222222222222222222222

Centroids 1

4a

4- +

F

r 3 + 22 2 222

e 22 2 222

q 22 2 222

u 22 2 222

e 2 - 22222 2222 222 2

n 22222 2222 222 2

c 22222 2222 222 2

y 22222 2222 222 2

1 - 22 22222 2222222222222 2

2 22222 2222222222222 2

2 22222 2222222222222 2

2 22222 2222222222222 2

X .- x----- + --

out -4.0 -2.0 .0 2.0 4.0 out

Class 111111111111111111111111111111111222222222222222222222222222

Centroids 2

20 1

1

1

F 1

r 15 1

e 11

q 111

u 1 111

e 10o 11111

n 111111 1

c 111111 1 1

y 111111 11 1

5 111111111 11

1111111111111

111111111111111 1 1

I 111111111111111111 1 1 I

x i~ i I11111211

I

--- I

71 Class

out -4.0

-

-2.0

I

.0 2.0

-I.....x

1111111111111111111111111111111111222222222222222222222222222

4.0

I

out

Centroids 1

4b

4 - 2

2

2

F 2

r 3 - 222 22 2

e 222 22 2

q 222 22 2

u 222 22 2

e 2 222 2 222 2 22

n 2 222 2 222 2 22

c 2 2 222 2 222 2 22

y 2 2 222 2 222 2 22

1 2 22 2222222 222222222 2

2 22 2222222 222222222 2

2 22 2222222 222222222 2

2 22 2222222 222222222 2

iI

out -4.0 -2.0 .0 2.0 4.0 out

Class 1111111111111111111111111111111111222222222222222222222222222

Centroids 2

Figure. 4. Histograms of Arrow and Dart D-scores (l=arrow, 2=dart).

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 16:50:06 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Shott] METRIC DISCRIMINATION OF CHIPPED-STONE POINTS 97

20 -

1

1

F 11

r 15 - 111

e 111

q 111

u 111

e 10 - 1111

n 1111 1

c 111111 111

y 1111111 111

5 - 11111111111

111111111111

-TI7~~~ ~1111111111111111111 1

/\z~~ 1111~111111111111111 1 1 1

X | i | i - ! X

out -4.0 -2.0 .0 2.0 4.0 out

Class 1111111111111111111111111111111111222222222222222222222222222

4c Centroids 1

2

F 2

r 6- 2

e 2

q 2

u 2

e 4 2 2

n 2 2

c 2 2 2 2

y 2 2 22

2 - 2 22 2222 22 2

2 22 2222 22 2

2 22222222 222222 2222 2

2 22222222 222222 2222 2

X I I I X

out -4.0 -2.0 .0 2.0 4.0 out

Class 111111111111111111111111111111111222222222222222222222222222

Centroids 2

20 -

1

F 11

r 15 111

e 111

q 111

u 111

e 10- 1111

n 1111 1

c 11111 1 1 1

y 1111111 111

5 - 111111111111

111111111111

11111111111111111 1

7I1 x I

11111111111111111

I i

1 1

I

1

x

out -4.0 -2.0 .0 2.0 4.0 out

Class 111111111 111111111

1111111111111111 222222222222222222222222222

Centroids

4d 1

8- 2

2

2

F 2

r 6- 2

e 2

q 2

u 2

e 4 -2 2 2

n 2 2 2

c 2 2 22

y 2 2 2 2

2 - 2 22 22 2 22 2

2 22 22 2 22 2

2 2222222 222222 2222 2

2 2222222 222222 2222 2

X I I x

out -4.0 -2.0 .0 2.0 4.0 out

Class 1111111111111111111111111111111111222222222222222222222222222

Centroids 2

Figure 4. Continued.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 16:50:06 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

98 AMERICAN ANTIQUITY [Vol. 62, No. 1, 1997

Only such research can determine if dart points adequate discriminatorbetween dart and arrow

are distinguishableon metric grounds from these points. Although reasonable, their studies were

other classes of points. confined to archaeological specimens of

unknown status. Van Buren (1974:24) also

Single-VariableAnalysis reported length and weight for several undocu-

Shoulder width emerges in all solutions as the mented dart points. Weighing hafted dart and

most significant discriminatorbetween dart and arrowpoints would requiretheirremovalfromthe

arrowpoints, to the extent that using a discrimi- haft, damaging the larger specimen; it is not a

nation function alone produces similar results to practicalprocedurefor the samples used here.

multiple-variablesolutions.Figure2 suggests that Corliss (1972) proposed a metric distinction

the shoulder-widththreshold between dart and between dart and arrow points based solely on

arrow lies near a value of 20 mm. Using this neck width. He did not explicitly specify a thresh-

value, 122 of 132 arrows (92.4 percent)but only old value, but his Figure 3 showed a gap between

30 of 39 darts (76.9 percent) are correctlyclassi- the classes ca. 8.5-9 mm. Beck (1995) and

fied. These results are identical to the relatively Chatterset al. (1995) adoptedsimilarapproaches,

poor four-variablesolution for darts, but better Beck explicitly using a thresholdvalue of 9 mm.

than any multivariatesolution for arrows. Darts Fawcett and Kornfeld (1980:72) located the

are the more difficult class to identify,which jus- thresholdat 10 mm.

tifies use of the one-variable function over the Unfortunately,data do not validate such an

threshold value because of the function's higher approach (cf. Corliss 1980:352). A neck width

dart-classificationrate. threshold of 9 mm correctly classifies 38 of 39

It bears emphasizing that Thomas's original dart points, but misclassifies as darts 82 of 132

data yield similar results, althoughthe following arrowpoints (62.1 percent).A thresholdvalue of

was not reportedin his study. The three-variable 8.5 mm produces identical results for darts but

solutionusing Thomas'sdatayields the same clas- misclassifies 89 arrow points (67.4 percent).

sification results as the four-variableone using Even a thresholdvalue of 10.4 mm, one standard

his data. The two-variable solution (shoulder deviation lower than Chatterset al.'s (1995:757)

width and thickness) correctly classifies eight of mean for inferred dart points, misclassifies 57

10 darts, and the one-variablesolution (shoulder arrows(43.2 percent).

width alone) correctlyclassifies nine of 10 darts, These studies were reasonable attempts to

the lone exceptionbeing the narrowestWhite Dog infer the status of archaeologicalunknowns.But

Cave specimen. width at the shoulder,not the neck, is the best sep-

Thus, shoulderwidth is by far the most signif- aratorof dartand arrowand then, contraCorliss's

icant discriminator of dart and arrow points. (1980) claim, especially in a discriminantanaly-

However, best classification results occur when sis. This study shows that other approachesare

shoulderwidth is used in a one-variablediscrimi- prone to a higher risk of error.

nant analysis, not as a simple threshold value.

Flake Points and the Antiquity of the North

Also, results closely resemble those obtained

American Arrow

using Thomas's original data. In both data sets,

classification success improves as length, neck Odell (1988) arguedthat flakes and bifaces were

width, and thicknessareremovedin order,leaving used as arrow points as early as the Archaic

only shoulder width in the solution. A carefully period,obviouslyproposinga much earlieradvent

chosen single variable can distinguish dart from for bow and arrowtechnology than most archae-

arrow,but does it best when used in a discrimi- ologists would accept. Museum collections of

nant analysis. North American materials include few flake

Otherstudies also stressed single variablesbut points to supportone partof Odell'sview andper-

did not use discriminant analysis or shoulder haps none dating to the time periods he proposed

width as the key variable.Fenenga(1953) andVan for the arrow'sintroduction.Odell (personalcom-

Buren (1974:21-22, 34) proposed weight as an munication1996) legitimatelystressedthe contin-

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 16:50:06 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Shott] METRICDISCRIMINATION

OF CHIPPED-STONEPOINTS 99

uum that links unmodified flakes to marginally variablelength,susceptibleto reductionduringuse

retouched ones to completely modified bifaces. andprohibitingthe studyof brokenspecimens,and

There are reasons to question Odell's conclusion the not-universalvariableneck width areremoved.

that unmodified or marginally retouched flakes Shoulderwidth alone yields resultsas satisfactory

functioned as arrow points and that both bifaces as any multiple-variablemodel. An independent

and such flakes were used as arrow points well test of classification, practicallylimited to arrow

before the first millennium A.D. (Seeman points, strengthensconfidence in results.

1992:42; Shott 1993:435), but it is plausible and Leaving aside other possible uses of chipped-

deserves serious regard. stone bifaces, we cannot with certainty classify

Amick (1994) and Patterson (1994) would archaeologicalunknownsas dart or arrowpoints,

push back the bow and arrow'sNorth American and we will never attainsuch an impossible goal.

introductionto the first colonizers.Thomas'sclas- The technologies to producedartsand arrowsare

sification functions identify some Folsom bifaces not as dramaticallydifferent as often supposed;

as arrow, not dart, points (Amick 1994:24), an therefore, dart and arrow points are not as dra-

intriguingfinding that Amick carefully qualified matically differentin size and form as often sup-

and that also deserves closer study. It is not posed. Similarity,however,is not identity,and the

implausible; small Early Archaic types such as classes are different enough that we can reason-

LeCroys probably would be classified as arrow ably distinguish them in 85 percent or more of

points. Yet no direct evidence for bow and arrow cases. Considering the problematicsof archaeo-

technology has been found in a Paleoindiancon- logical inference, that is not a bad average.

text, while atlatl equipmenthas been found there

(Heite and Blume 1995:53; Judge 1973:84) Acknowledgments.Thanks are due to Elaine Hughes and

Debbie Fenichel of the Museum of NorthernArizona, Robin

The Siberian evidence that Pattersonadduced

Laska and Carol Rector of the San Bernardino County

(Chard 1974:37) involves tanged points that do Museum, Charles Stanish and Christine Gross of the Field

not resemble the North American archaeological Museumof NaturalHistory,Jane Ketchamof Beloit College's

specimens with which he identifies them. Logan Museum of Anthropology,MargaretHardinand Chris

Patterson's (1994:20) criteria for flake arrow Coleman of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles

County, James Krakkerof the SmithsonianInstitution,Lucy

points-deliberate retouch, "appropriateshape to Fowler Williams and John Cotter of the UniversityMuseum,

function as an arrowpoint,"symmetricaltip, and

University of Pennsylvania,Mark Clark and Kathleen Ash-

basal retouch-are not sufficiently rigorous or Milby of the NationalMuseumof the AmericanIndian,Margot

uniquely characteristicof use as arrowsto accept Reid and Rachel Perkins of the Canadian Museum of

his argument.Pattersonmay be right, but more Civilization, Joel Janetski of Brigham Young University's

evidence is needed to supporthis view. Museumof Peoples and Cultures,and DuncanMetcalfe of the

Utah Museum of NaturalHistory.Reid, Perkins,Krakker,and

In the strictest sense, Odell's and Patterson's Janetski deserve special thanks for their kindnesses. I also

argumentsare not relevantto this study despite receivedassistancefromthe PeabodyMuseum.CharlotteBeck,

their possible merit because they concern flake Andrew Christenson,George Odell, and David Thomas pro-

points as well as bifaces. Amick's argumentcan vided wise counsel.The Universityof NorthernIowasupported

be tested furtherwith the functionsreportedhere. the research with a 1992 College of Social and Behavioral

Sciences grantand a 1995 summerresearchfellowship.

Only when we shift focus to the timing and nature

of the transition from dart to arrow (e.g., Blitz References Cited

1988; Shott 1993, 1996) do the arguments

Amick, D. S.

become relevant, a shift in focus beyond this 1994 Technological Organization and the Structure of

study's scope. Inferencein Lithic Analysis: An Examinationof Folsom

Hunting Behavior in the American Southwest. In The

Conclusion Organization of North American Prehistoric Chipped

Stone Tool Technologies, edited by P. Carr, pp. 9-34.

A dart sample substantiallylargerthan Thomas's Archaeological Series No. 7. InternationalMonographs

in Prehistory,Ann Arbor,Michigan.

(1978) improvesthe ability of discriminantanaly-

Baxter,M. J.

sis to distinguish dart from arrow points. 1993 ExploratoryMultivariateData AnalysisinArchaeology.

Separationis especiallygood when the problematic EdinburghUniversityPress,Edinburgh,Scotland.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 16:50:06 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

100 AMERICAN ANTIQUITY [Vol. 62, No. 1, 1997

1994 Stepwise DiscriminantAnalysis in Archaeometry:A EthnologyVol. 8 No. 2. HarvardUniversity,Cambridge,

Critique.Journal ofArchaeological Science 21:659-666. Massachusetts.

Beck, C. Gunnerson,J. H.

1995 Projectile Point Types as Valid Chronological Units. 1969 TheFremontCulture.A Studyin CulturalDvnamicson

Manuscript on file, Department of Anthropology, the NorthernAnasazi Frontier Papers of the Peabody

HamiltonCollege, Clinton, New York. Museumof AmericanArchaeologyand EthnologyVol. 59

Blitz, J. H. No. 2. HarvardUniversity,Cambridge,Massachusetts.

1988 Adoption of the Bow in PrehistoricNorth America. Hall, R. L.

NorthAmericanArchaeologist9:123-145. 1977 An AnthropocentricPerspective for Eastern United

Chard,C. S. States Prehistory.AmericanAntiquity42:499-518.

1974 NortheastAsia in Prehistory.Universityof Wisconsin Harrington,M. R.

Press, Madison. 1960 The Ozar/k Bluff-Dwellers. Indian Notes and

Chatters,J. C., S. K. Campbell,G. D. Smith, and P. Minthorn, MonographsVol. 12. Museum of the American Indian,

Jr. New York.

1995 Bison Procurementin the FarWest:A 2,100-Year-Old Hattori,E. M.

Kill on the Columbia Plateau. American Antiquity 1982 TheArchaeology of Falcon Hill, WinnemuccaLake,

60:751-763. WashoeCounty,Nevada. AnthropologicalPapersNo. 18.

Christenson,A. L. Nevada State Museum,CarsonCity.

1986 ProjectilePoint Size and ProjectileAerodynamics:An Heite, E. E, and C. L. Blume

ExploratoryStudy.Plains Anthropologist31:109-128. 1995 Data Recovery Excavations at the Blueberrn Hill

Corliss, D. W. Prehistoric Site (7K-C- 07). Archaeological Series No.

1972 Neck Widthof Projectile Points. An Index of Culture 130. Department of Transportation, Wilmington,

Continuitvand Change.OccasionalPapersNo. 29. Idaho Delaware.

State UniversityMuseum, Pocatello. Heizer, R. F.

1980 Arrowpointor Dart Point:An UninterestingAnswer to a 1938 An Inquiryinto the Statusof the SantaBarbaraSpear-

TiresomeQuestion.AmericanAntiquity45:351-352. Thrower.AmericanAntiquity4:137-141.

Cosgrove, C. B. Hoffman,W.J.

1947 Caves of the Upper Gila and Hueco Areas in Nei' 1896 The Menomini Indians. In Annual Report of the

Mexico and Texas. Papers of the Peabody Museum of Burealuof American Ethnology, vol. 14, pp. 11-328.

American Archaeology and Ethnology Vol. 24 No. 2. SmithsonianInstitution,Washington,D.C.

HarvardUniversity,Cambridge,Massachusetts. Hughes, S. S.

Cundy,B. J. 1995 Gettingto the Point:EvolutionaryChangein Prehistoric

1989 Formal Variation in Australian Spear and Weaponry.Unpublishedmanuscripton file, Departmentof

SpearthrowerTechnolog).BAR InternationalSeries 546. Anthropology,Universityof Washington,Seattle.

BritishArchaeologicalReports,Oxford. Jennings,J.

Davis, C. A., and G. A. Smith 1957 Danger Cave. Anthropological Papers No. 27.

1981 NewhberriCave. San Bernardino County Museum Universityof Utah, Salt Lake City.

Association, Redlands,California. Judge, W. J.

DeBoer, W. R. 1973 Paleoindian Occupation of the Central Rio Grande

1985 Pots and Pans Do Not Speak, Nor Do They Lie: The Vallel in New Mexico. Universityof New Mexico Press,

Case for Occasional Reducationism. In Decoding Albuquerque.

Prehistoric Ceramics, edited by Ben Nelson, pp. Klecka, W. R.

347-357. SouthernIllinois UniversityPress, Carbondale. 1975 Discriminant Analysis. Sage Publications, Beverly

Edmonds,M., and J. Thomas Hills, California.

1987 The Archers:An EverydayStory of CountryFolk. In Larralde,S. L.

Lithic Analysis and Later British Prehistor.y Some 1990 The Design of Hunting Weapons. Archaeological

Problems and Approaches, edited by A. Brown and M. Evidence from Southwestern Wyoming. Unpublished

Edmonds,pp. 187-199. BAR British Series 162. British Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology,

ArchaeologicalReports,Oxford. Universityof New Mexico, Albuquerque.

Fawcett,W. B., and M. Kornfeld Lindsay,A. J., R. A. Ambler,M. A. Stein, and P. M. Hobler

1980 Projectile Point Neck-Width Variability and 1968 Survey'and Excavation North and East of Navajo

Chronology on the Plains. WyomingContributionsto Mountain, Utah, 1959-1962. Bulletin 45. Museum of

Anthropology? 2:66-79. NorthernArizona, Flagstaff.

Fenenga,F. Lorentzen,L. H.

1953 The Weightsof ChippedStone Points:A Clue to Their 1989 Form and Function of the Chodistaas and

Functions. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology GrasshopperSpringProjectilePoints. Unpublishedman-

9:309-323. uscripton file, Departmentof Anthropology,University

Fowler,D., and J. Matley of Arizona,Tucson.

1979 Material Culture of the Numa. The John Wesley Maschner,H. D.

Powell Collection, 1867-1880. Smithsonian 1991 The Emergence of Cultural Complexity on the

Contributions to Anthropology No. 26. Smithsonian NorthernNorthwestCoast. Antiquity65:924-934.

Institution,Washington,D.C. Massey,W. C.

Guernsey,S. J., and A. V Kidder 1961 The Survivalof the Dart-Throweron the Peninsulaof

1921 Basket-MakerCaves of NortheasternArizona. Papers Baja California. SouthwesternJournal of Anthropology

of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and 17:81-92.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 16:50:06 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Shott] METRICDISCRIMINATION

OF CHIPPED-STONEPOINTS 101

Montgomery,H. Valley, Nevada. Journal of California and Great Basin

1894 Pre-Historic Man in Utah. The Archaeologist Anthropology3:7-43.

2(8):227-234. Waterloo,Indiana. Troeng,J.

Nelson, E. W. 1993 Worldwide Chronology of Fifty-Three Prehistoric

1899 The Eskimo about Bering Strait.In Annual Report of Innovations. Acta Archaeologica Lundensia, Series 8,

the Bureau ofAmerican Ethnology, vol. 18, pp. 19-518. No. 21. Almqvist and Wiksell, Stockholm.

SmithsonianInstitution,Washington,D.C. Tuohy,D. R.

Norusis, M. J. 1982 Another Great Basin Atlatl with Dart Foreshaftsand

1993 SPSSfor WindowsBase System User s Guide,Release OtherArtifacts:Implicationsand Ramifications.Journal

6.0. SPSS Inc., Chicago. of Californiaand Great Basin Anthropology4:80-106.

Nusbaum,J. L. Van Buren, G. E.

1922 A Basket-MakerCave in Kane County, Utah. Indian 1974 Arrowheads and Projectile Points with a

Notes and MonographsNo. 29. Museumof the American Classification Guide for Lithic Artifacts. Arrowhead

Indian,New York. Publishing,GardenGrove, California.

Odell, G. H. Vinnicombe,P.

1988 Addressing Prehistoric Hunting Practices through 1972 Myth, Motive, and Selection in Southern African

Stone Tool Analysis. American Anthropologist Cave Art. Africa 42:192-204.

90:335-356. Woodward,A. J.

Palter,J. L. 1930 Reportof the Activities of the Van Buren-LosAngeles

1977 Design and Constructionof AustralianSpear-Thrower Museum Field Party on Archaeological Sites in the

Projectiles and Hand-ThrownSpears. Archaeology and Vicinity of Navajo Mountain, San Juan County, Utah.

Physical Anthropologyin Oceania 12:161-172. Manuscripton file, Los Angeles County Museum of

Patterson,L. W. NaturalHistory,Los Angeles.

1994 Identification of Unifacial Arrow Points. Journal of

the HoustonArchaeologicalSociety 108:19-24. Notes

Pepper,G. H.

1905 The Throwing-Stick of a Prehistoric People of the 1. By no means is Table 1 exhaustive.Travel was limited to

Southwest. Proceedings of the 13th International North American museums easily reached incidentalto other

Congress ofAmericanists:107-130. traveland to one tripto majormuseumsthatpossess relatively

Perkins,W. large holdings. Several other North American museums hold

1992 The Weighted Atlatl and Dart: A Deceptively one or more darts. Several British museums hold nearly 300

Complicated Mechanical System. Archaeology in darts(Palter1977), althoughnot all may have stone points. No

Montana33:65-77.

doubt the sample could be increased even more by visiting

Rose, F. G. G.

1960 Classification of Kin, Age Structure and Marriage othermajormuseums in Europeand elsewhere.

amongst the Groole Eylandt Aborigines: A Study in Reluctantly,Thomas'sspecimen 97179 was removed. Several

Method and a Theory of Australian Kinship. Akademie PeabodyMuseum specimens bear that number,including two

Verlag,Berlin. intact ones. But the metric values Thomas (1978:Table 3)

Seeman, M. F. reportedresemble each in some attributes,the other in other

1992 The Bow and Arrow,the IntrusiveMound Complex, attributes.Thus, Thomas's specimen could not be identified

and a Late WoodlandJack's Reef Horizon in the Mid-

reliablywith eitherexaminedduringthis study,so his entrywas

Ohio Valley.In CulturalVariabilityin Context:Woodland

removedin favorof those two.

Settlementsof the Mid-OhioValley,editedby M. Seeman,

2. Specimens at Brigham Young University were thickly

pp. 41-51. MCJA Special Paper No. 7. Kent State

University,Kent, Ohio. wrappedin sinew lashing that made it impossible to measure

Shott, M. J. neck width and, in a few cases, otherattributes.Thicknesswas

1993 Spears, Darts, and Arrows: Late WoodlandHunting measuredon all specimens. However,the specimens were x-

Techniquesin the UpperOhio Valley.AmericanAntiquity rayedthroughthe kind offices of Joel Janetski,and the result-

58:425-443. ing image clearly distinguishedthe stone points from foreshaft

1996 Innovation in Prehistory: A Case Study from the and lashing. Plan-view metrics were measureda second time

American Bottom. In Stone Tools. Theoretical Insights from the image, neck width includedon this occasion. Results

Into HumanPrehistory,edited by G. Odell, pp. 279-309. then were comparedto originalmeasurements.Averagediffer-

Plenum, New York.

ences were less than 1 mm and no statisticallysignificant dif-

Skinner,A.

1921 Material Cultureof the Menomini. IndianNotes and ferences were found (2-tailed p values for length, shoulder

MonographsVol. 20. Museum of the American Indian, width, and base width were .88, .55, and .84, respectively).

New York. Thomas (1978:467) reached a similar conclusion about the

Testart,A. accuracyof measurementsfrom X-ray images. Because neck

1988 Some Major Problemsin the Social Anthropologyof width could be measuredonly fromthe X-ray,all reportedmet-

Hunter-Gatherers.CurrentAnthropology29:1-31. ric values are taken from that image.

Thomas, D. H.

1978 ArrowheadsandAtlatl Darts:How the Stones Got the

Shaft. AmericanAntiquity43:461-472. Received May 13, 1996; accepted July 10, 1996; revised

1981 How to Classify the Projectile Points from Monitor August 6, 1996.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.223 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 16:50:06 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Ringmakers of Saturn by Norman R. BergrunDocument149 pagesRingmakers of Saturn by Norman R. BergrunPEDRONo ratings yet

- Ring Makers of Saturn - Norman Bergrun 1986Document125 pagesRing Makers of Saturn - Norman Bergrun 1986Excaliburka100% (5)

- Rings of SaturnDocument116 pagesRings of Saturnclasic100% (1)

- Technomad Global Raving CounterculturesDocument325 pagesTechnomad Global Raving CounterculturesSonnenschein100% (1)

- Underground Structures: Design and InstrumentationFrom EverandUnderground Structures: Design and InstrumentationRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- (Bernard Bourdon) Uranium-Series Geochemistry PDFDocument683 pages(Bernard Bourdon) Uranium-Series Geochemistry PDFHJKB1975100% (1)

- mp-95-4 WilsonDocument156 pagesmp-95-4 WilsonRussell Hartill100% (1)

- Business Moments Graphic AssignmebtDocument11 pagesBusiness Moments Graphic AssignmebtAnakha PrasadNo ratings yet

- The Geometrical Foundation of Natural Structure A Source Book o PDFDocument292 pagesThe Geometrical Foundation of Natural Structure A Source Book o PDFGuillermo Aparicio GomezNo ratings yet

- Genesis Porphyry Moybdenum DepositsDocument34 pagesGenesis Porphyry Moybdenum DepositsEber Gamboa100% (1)

- Dinosaurs: The Myth-busting Guide to Prehistoric BeastsFrom EverandDinosaurs: The Myth-busting Guide to Prehistoric BeastsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Topographic Map of Riverland CemeteryDocument1 pageTopographic Map of Riverland CemeteryHistoricalMaps100% (1)

- Planetary Geology in The 1980sDocument203 pagesPlanetary Geology in The 1980sBob AndrepontNo ratings yet

- Geothermics in Basin Analysis - Forster - 1999Document250 pagesGeothermics in Basin Analysis - Forster - 1999lovingckw100% (1)

- Elementary Statistics 6th Edition Allan Bluman Solutions ManualDocument18 pagesElementary Statistics 6th Edition Allan Bluman Solutions ManualDanielleDaviscedjo100% (19)

- Zivot - Introduction To Computational Finance and Financial EconometricsDocument188 pagesZivot - Introduction To Computational Finance and Financial Econometricsjrodasch50% (2)

- CHAPTER 4 Measures of Dispersion (Variation)Document17 pagesCHAPTER 4 Measures of Dispersion (Variation)yonas100% (1)

- Measures of Central TendencyDocument11 pagesMeasures of Central TendencyHimraj BachooNo ratings yet

- Atlatl Final 3Document14 pagesAtlatl Final 3Adolfo OkuyamaNo ratings yet

- Churchite From The MT Weld Carbonatite Laterite, Western AustraliaDocument3 pagesChurchite From The MT Weld Carbonatite Laterite, Western AustraliaMuchlis NurdiyantoNo ratings yet

- Cob - Evolution CordilleraDocument7 pagesCob - Evolution CordilleraCarlos Yomona PerezNo ratings yet

- Stone Artifacts and Hominins in Island Southeast Asia: New Insights From Flores, Eastern IndonesiaDocument19 pagesStone Artifacts and Hominins in Island Southeast Asia: New Insights From Flores, Eastern Indonesiajuana2000No ratings yet

- Walthall RocksheltersHunterGathererAdaptation 1998Document17 pagesWalthall RocksheltersHunterGathererAdaptation 1998jesuszarco2021No ratings yet

- 1996 - Debris Avalanche-Harry GlickenDocument98 pages1996 - Debris Avalanche-Harry GlickenI Nyoman SutyawanNo ratings yet

- Ol 006Document9 pagesOl 006KbrNo ratings yet

- Nyame Akuma Issue 029Document65 pagesNyame Akuma Issue 029Jac StrijbosNo ratings yet

- Experiments in Ceramic Technology The Effects of Various Tempering Materials On Impact and Thermal Shock Resistamce Bronitsky 1986Document14 pagesExperiments in Ceramic Technology The Effects of Various Tempering Materials On Impact and Thermal Shock Resistamce Bronitsky 1986Rigel AldebaránNo ratings yet

- Crystallography 333Document613 pagesCrystallography 333Biciin MarianNo ratings yet

- Ringmakers of SaturnDocument120 pagesRingmakers of SaturnJorge Osinaga ParedesNo ratings yet

- New Light Shed On The Oldest Insect: Letters To NatureDocument4 pagesNew Light Shed On The Oldest Insect: Letters To NatureDaniel Machado de OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Global Circulation of Radiocerium Isotopes From The May 14, 1965, Nuclear ExplosioDocument8 pagesGlobal Circulation of Radiocerium Isotopes From The May 14, 1965, Nuclear ExplosioAnonymous d1CGjMTiNo ratings yet

- Massive Sulphides PDFDocument8 pagesMassive Sulphides PDFNmd NuzulNo ratings yet

- Nasa Technical Memorandum NASA TMX-58073 December 1971Document16 pagesNasa Technical Memorandum NASA TMX-58073 December 1971RobSchenckNo ratings yet

- Lottermoser B.G. - Churchite From The MT Weld Carbonatite Laterite, Western AustraliaDocument2 pagesLottermoser B.G. - Churchite From The MT Weld Carbonatite Laterite, Western AustraliaMuchlis NurdiyantoNo ratings yet

- Underwood 2003 Nankai Slopebasin JSRDocument15 pagesUnderwood 2003 Nankai Slopebasin JSRWilmer CuicasNo ratings yet

- Sandstones PDFDocument18 pagesSandstones PDFJavi CaicedoNo ratings yet

- Stein 1987 (Deposits For Archaeology)Document60 pagesStein 1987 (Deposits For Archaeology)Robert Ponce VargasNo ratings yet

- The Formation of FlakesDocument36 pagesThe Formation of FlakesMurat özturanNo ratings yet

- EQ List Date 2Document2 pagesEQ List Date 2McKenzie StaufferNo ratings yet

- Experiments in Ceramic TechnologyDocument14 pagesExperiments in Ceramic TechnologyjbsingletonNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Redeposited Artifacts McFaddin Beach TexasDocument321 pagesAnalysis of Redeposited Artifacts McFaddin Beach TexasetchplainNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0267726199000123 MainDocument22 pages1 s2.0 S0267726199000123 MainBeta IwanNo ratings yet

- Hartman 1966 Polychaeta Sedentaria Antarctica LiteDocument166 pagesHartman 1966 Polychaeta Sedentaria Antarctica LiteValentina Sandoval ParraNo ratings yet

- 2006 Nickel SulfideDocument66 pages2006 Nickel SulfidebagustrisetiaajiNo ratings yet

- (Oscar R. López-Gamundí, Luis A. Buatois) Late P PDFDocument218 pages(Oscar R. López-Gamundí, Luis A. Buatois) Late P PDFRaíd André MerinoNo ratings yet

- Tate-1896-Palaeont Horn Exped C AustraliaDocument45 pagesTate-1896-Palaeont Horn Exped C AustraliaVerónica BerteroNo ratings yet

- Fission-Trackdating of Southamerican Natural Glasses: An OverviewDocument10 pagesFission-Trackdating of Southamerican Natural Glasses: An OverviewPaúl CabezasNo ratings yet

- Intermineral Intrusions and Their Bearing and The Origin of Porphyry CopperDocument6 pagesIntermineral Intrusions and Their Bearing and The Origin of Porphyry CopperGuillermo Hermoza MedinaNo ratings yet

- Report PDFDocument398 pagesReport PDFBroadsageNo ratings yet

- Bold Endeavors: Lessons from Polar and Space ExplorationFrom EverandBold Endeavors: Lessons from Polar and Space ExplorationRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Society For American ArchaeologyDocument17 pagesSociety For American Archaeologymoni_ayalauahNo ratings yet

- 6922 - Woodman - Overmyer Mastodon (Mammut Americanum)Document22 pages6922 - Woodman - Overmyer Mastodon (Mammut Americanum)KanekoNo ratings yet

- Animales ZoooMegaDocument19 pagesAnimales ZoooMegaClaudia TRNo ratings yet

- 2020 JAHHvol 23 No 1 CompleteDocument230 pages2020 JAHHvol 23 No 1 CompletekowunnakoNo ratings yet

- Sismología: Maestría en Ingeniería Estructural y SísmicaDocument10 pagesSismología: Maestría en Ingeniería Estructural y SísmicaJhosemarCcamaNo ratings yet

- The Production Step Measure An Ordinal Index of Labor Input in Ceramic Manufacture Feinman 1981Document15 pagesThe Production Step Measure An Ordinal Index of Labor Input in Ceramic Manufacture Feinman 1981Luis Miguel SotoNo ratings yet

- Bruhn Etal 2005Document21 pagesBruhn Etal 2005ilham ferdiNo ratings yet

- d2 Men Alltime Top10Document14 pagesd2 Men Alltime Top10Jeff BakerNo ratings yet

- Index of Generic Names of Fossil Plants 1974-1978 by Arthur D. WattDocument67 pagesIndex of Generic Names of Fossil Plants 1974-1978 by Arthur D. WattJiguur BayasgalanNo ratings yet

- Predictive Geology: With Emphasis on Nuclear-Waste DisposalFrom EverandPredictive Geology: With Emphasis on Nuclear-Waste DisposalNo ratings yet

- Stone Artifacts and Hominins in Island SDocument18 pagesStone Artifacts and Hominins in Island SRaditya BagoosNo ratings yet

- Survey Notes, September 2015Document16 pagesSurvey Notes, September 2015State of UtahNo ratings yet

- Centipede Site Phase Three Report 12-6-06Document71 pagesCentipede Site Phase Three Report 12-6-06Phillip MendenhallNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Mathematical StatisticsDocument23 pagesFundamentals of Mathematical StatisticsSudeep MazumdarNo ratings yet

- Descriptive Statistics: Example 2.1Document31 pagesDescriptive Statistics: Example 2.1Melvin Earl AgdaNo ratings yet

- Adv Stats LessonsDocument36 pagesAdv Stats LessonsIRISH REEM LINAOTANo ratings yet

- KTE Pudu Jaya 2022 QDocument3 pagesKTE Pudu Jaya 2022 QQianyee WendyNo ratings yet

- Data Mining For Fraud DetectionDocument12 pagesData Mining For Fraud DetectionMahadevan VenkatesanNo ratings yet

- Basic Business Statistics: 12 EditionDocument51 pagesBasic Business Statistics: 12 EditionMustakim Mehmud TohaNo ratings yet

- Q ManualDocument39 pagesQ ManualDavid HumphreyNo ratings yet

- SB Quiz 3Document16 pagesSB Quiz 3Tran Pham Quoc Thuy100% (1)

- Tutorial 3 PMC 500 Vigneswery ThangarajDocument6 pagesTutorial 3 PMC 500 Vigneswery ThangarajVigneswery ThangarajNo ratings yet

- I10064664-E1 - Statistics Study Guide PDFDocument81 pagesI10064664-E1 - Statistics Study Guide PDFGift SimauNo ratings yet

- Cultural Tourism An Analysis of Engagement, Cultural Contact, MemorableDocument11 pagesCultural Tourism An Analysis of Engagement, Cultural Contact, MemorableirfanNo ratings yet

- Determining The Probability of Project Cost OverrunsDocument10 pagesDetermining The Probability of Project Cost OverrunsStevanus FebriantoNo ratings yet

- Engineering StructuresDocument13 pagesEngineering StructuresAnonymous sQGjGjo7oNo ratings yet

- Bcom Business StatisticsDocument22 pagesBcom Business StatisticsManishKumar100% (1)

- Research Methodology Research Design Comprehensive Exam Study GuideDocument3 pagesResearch Methodology Research Design Comprehensive Exam Study GuideMukhtaar CaseNo ratings yet

- Text Book of Maths and StatsDocument378 pagesText Book of Maths and StatsPrasad ApartmentsNo ratings yet

- PRPY 121A Psychological Statistics - 7Document12 pagesPRPY 121A Psychological Statistics - 7Lea Sapphira SuronNo ratings yet

- 5 Assignment5Document10 pages5 Assignment5Shubham Goel67% (3)

- BIO Central Tendency Distributions and SpreadDocument30 pagesBIO Central Tendency Distributions and SpreadAhmed AhmedNo ratings yet

- MBA503A Statistical Techniques v2.1Document5 pagesMBA503A Statistical Techniques v2.1Ayush SatyamNo ratings yet

- Chapter3 Julie Riise KolstadDocument28 pagesChapter3 Julie Riise KolstaddatateamNo ratings yet

- Planning Fatigue Tests For Polymer CompositesDocument33 pagesPlanning Fatigue Tests For Polymer CompositesAstro EspejosNo ratings yet

- Liquidity and Financial Performance A Correlational Analysis of Quoted Non Financial Firms in GhanaDocument11 pagesLiquidity and Financial Performance A Correlational Analysis of Quoted Non Financial Firms in GhanaEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 Skewness and Kurtosis: StructureDocument10 pagesUnit 4 Skewness and Kurtosis: StructurePranav ViswanathanNo ratings yet

- Nama: Ketut Dian Caturini NIM: 1813011007 Kelas: 7B Tugas 2Document3 pagesNama: Ketut Dian Caturini NIM: 1813011007 Kelas: 7B Tugas 2Sri AgustiniNo ratings yet