Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Representative Democracy - Wikipedia

Uploaded by

baponcsarkar2004Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Representative Democracy - Wikipedia

Uploaded by

baponcsarkar2004Copyright:

Available Formats

Search Wikipedia Search Create account Log in

Representative democracy 62 languages

Contents hide Article Talk Read Edit View history Tools

(Top) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

History

Representative democracy (also electoral democracy or indirect democracy) is a type of democracy

Part of the Politics series

Research on representation per se where representatives are elected by the public.[1] Nearly all modern Western-style democracies function

Democracy

Criticisms as some type of representative democracy: for example, the United Kingdom (a unitary parliamentary

History · Theory · Indices

constitutional monarchy), Germany (a federal parliamentary republic), France (a unitary semi-presidential

Proposed solutions

republic), and the United States (a federal presidential republic).[2] This is different from direct democracy.[3] Types [show]

See also [show]

Related topics

Political parties often become prominent to this form of democracy if electoral systems require or

References

encourage voters to vote for political parties or for candidates associated with political parties (as opposed Politics portal

External links to voting for individual representatives).[4] Some political theorists (including Robert Dahl, Gregory Houston, · ·

and Ian Liebenberg) have described representative democracy as polyarchy.[5][6]

Part of the Politics series

Representative democracy can be organized in different ways, including both parliamentary and

Basic forms of government

presidential systems of government. Elected representatives typically form a legislature (such as a

parliament or congress), which may be composed of a single chamber or two chambers. Where two List of forms of government

chambers exist, their members are often elected in different ways. The power of representatives is usually

List of countries by system of government

curtailed by a constitution (as in a constitutional democracy or a constitutional monarchy) or other

Source of power [show]

measures to balance representative power:[7]

Power ideology [show]

An independent judiciary, which may have the power to declare legislative acts unconstitutional (e.g.

Power structure [show]

constitutional court, supreme court).

Related [show]

The constitution may also provide for some deliberative democracy (e.g., Royal Commissions) or direct

Politics portal

popular measures (e.g., initiative, referendum, recall elections). However, these are not always binding

and usually require some legislative action—legal power usually remains firmly with representatives. · ·

[where?]

In some cases, a bicameral legislature may have an "upper house" that is not directly elected, such as the Senate of Canada, which was in turn

modeled on the British House of Lords.

Theorists such as Edmund Burke believe that part of the duty of a representative was not simply to communicate the wishes of the electorate but also to

use their own judgment in the exercise of their powers, even if their views are not reflective of those of a majority of voters:[8]

Certainly, Gentlemen, it ought to be the happiness and glory of a Representative, to live in the strictest union, the closest correspondence, and

the most unreserved communication with his constituents. Their wishes ought to have great weight with him; their opinion, high respect; their

business, unremitted attention. It is his duty to sacrifice his repose, his pleasures, his satisfactions, to theirs; and above all, ever, and in all

cases, to prefer their interest to his own. But his unbiassed opinion, his mature judgment, his enlightened conscience, he ought not to sacrifice

to you, to any man, or to any set of men living. These he does not derive from your pleasure; no, nor from the Law and the Constitution. They

are a trust from Providence, for the abuse of which he is deeply answerable. Your representative owes you, not his industry only, but his

judgment; and he betrays, instead of serving you, if he sacrifices it to your opinion.

History [ edit ]

See also: Democratization

The Roman Republic was the first known state in the Western world to have a representative government, despite taking the form of a direct government

in the Roman assemblies. The Roman model of governance would inspire many political thinkers over the centuries,[9] and today's modern

representative democracies imitate more the Roman than the Greek model, because it was a state in which supreme power was held by the people and

their elected representatives, and which had an elected or nominated leader.[10] Representative democracy is a form of democracy in which people vote

for representatives who then vote on policy initiatives; as opposed to direct democracy, a form of democracy in which people vote on policy initiatives

directly.[11] A European medieval tradition of selecting representatives from the various estates (classes, but not as we know them today) to

advise/control monarchs led to relatively wide familiarity with representative systems inspired by Roman systems.

In Britain, Simon de Montfort is remembered as one of the fathers of representative government for holding two famous parliaments.[12][13] The first, in

1258, stripped the king of unlimited authority and the second, in 1265, included ordinary citizens from the towns.[14] Later, in the 17th century, the

Parliament of England implemented some of the ideas and systems of liberal democracy, culminating in the Glorious Revolution and passage of the Bill

of Rights 1689.[15][16] Widening of the voting franchise took place through a series of Reform Acts in the 19th and 20th centuries.

The American Revolution led to the creation of a new Constitution of the United States in 1787, with a national legislature based partly on direct elections

of representatives every two years, and thus responsible to the electorate for continuance in office. Senators were not directly elected by the people until

the adoption of the Seventeenth Amendment in 1913. Women, men who owned no property, and Black people, and others not originally given voting

rights, in most states eventually gained the vote through changes in state and federal law in the course of the 19th and 20th centuries. Until it was

repealed by the Fourteenth Amendment following the Civil War, the Three-Fifths Compromise gave a disproportionate representation of slave states in

the House of Representatives relative to the voters in free states.[17][18]

In 1789, Revolutionary France adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and, although short-lived, the National Convention was

elected by all males in 1792.[19] Universal male suffrage was re-established in France in the wake of the French Revolution of 1848.[20]

Representative democracy came into general favour particularly in post-industrial revolution nation states where large numbers of citizens evinced

interest in politics, but where technology and population figures remained unsuited to direct democracy.[citation needed] Many historians credit the Reform

Act 1832 with launching modern representative democracy in the United Kingdom.[21][22]

Globally, a majority of governments in the world are representative democracies, including constitutional

monarchies and republics with strong representative branches.[23]

Research on representation per se [ edit ]

Further information: Representation (politics)

Separate but related, and very large, bodies of research in political philosophy and social science investigate The U.S. House of

how and how well elected representatives, such as legislators, represent the interests or preferences of one or Representatives, one example of

representative democracy

another constituency. The empirical research shows that representative systems tend to be biased towards the

representation of more affluent classes to the detriment of the population at large.[24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31]

Criticisms [ edit ]

In his book Political Parties, written in 1911, Robert Michels argues that most representative systems deteriorate towards an oligarchy or particracy. This

is known as the iron law of oligarchy.[32] Representative democracies which are stable have been analysed by Adolf Gasser and compared to the

unstable representative democracies in his book Gemeindefreiheit als Rettung Europas which was published in 1943 and a second edition in 1947.[33]

Adolf Gasser stated the following requirements for a representative democracy in order to remain stable, unaffected by the iron law of oligarchy:

Society has to be built up from bottom to top. As a consequence, society is built up by people, who are free and have the power to defend themselves

with weapons.

These free people join or form local communities. These local communities are independent, which includes financial independence, and they are

free to determine their own rules.

Local communities join into a higher unit, e.g. a canton.

There is no hierarchical bureaucracy.

There is competition between these local communities, e.g. on services delivered or on taxes.

A drawback to this type of government is that elected officials are not required to fulfill promises made before their election and are able to promote their

own self-interests once elected, providing an incohesive system of governance.[34] Legislators are also under scrutiny as the system of majority-won

legislators voting for issues for the large group of people fosters inequality among the marginalized.[35]

Proponents of direct democracy criticize representative democracy due to its inherent structure. As the fundamental basis of representative democracy is

non inclusive system, in which representatives turn into an elite class that works behind closed doors, as well as the criticizing the elector system as

being driven by a capitalistic and authoritarian system.[36][37]

Proposed solutions [ edit ]

The system of stochocracy has been proposed as an improved system compared to the system of representative democracy, where representatives are

elected. Stochocracy aims to at least reduce this degradation by having all representatives appointed by lottery instead of by voting. Therefore, this

system is also called lottocracy. The system was proposed by the writer Roger de Sizif in 1998 in his book La Stochocratie. Choosing officeholders by lot

was also the standard practice in ancient Athenian democracy[38] and in ancient India. The rationale behind this practice was to avoid lobbying and

electioneering by economic oligarchs.

The system of deliberative democracy is a mix between a majority-ruled system and a consensus-based system. It allows for representative democracies

or direct democracies to coexist with its system of governance, providing an initial advantage.[39]

See also [ edit ]

Democracy

Political representation

Proportional Representation

References [ edit ]

1. ^ Black, Jeremy; Brewer, Paul; Shaw, Anthony; Chandler, Malcolm; 20. ^ French National Assembly. "1848 " Désormais le bulletin de vote doit

Cheshire, Gerard; Cranfield, Ingrid; Ralph Lewis, Brenda; Sutherland, Joe; remplacer le fusil " " (in French). Retrieved 26 September 2009.

Vint, Robert (2003). World History. Bath, Somerset: Parragon Books. p. 341. 21. ^ A. Ricardo López; Barbara Weinstein (2012). The Making of the Middle

ISBN 0-75258-227-5. Class: Toward a Transnational History . Duke UP. p. 58. ISBN 978-

2. ^ Loeper, Antoine (2016). "Cross-border externalities and cooperation 0822351290.

among representative democracies". European Economic Review. 91: 180– 22. ^ Eric J. Evans, The Forging of the Modern State: Early Industrial Britain,

208. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2016.10.003 . hdl:10016/25180 . 1783–1870 (2nd ed. 1996) p. 229

3. ^ "Victorian Electronic Democracy, Final Report – Glossary" . 28 July 23. ^ Roser, Max (15 March 2013). "Democracy" . Our World in Data.

2005. Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. Retrieved 24. ^ Jacobs, Lawrence R.; Page, Benjamin I. (February 2005). "Who Influences

14 December 2007. U.S. Foreign Policy?". American Political Science Review. 99 (1): 107–123.

4. ^ De Vos et al (2014) South African Constitutional Law – In Context: Oxford doi:10.1017/S000305540505152X . S2CID 154481971 .

University Press. 25. ^ Bernauer, Julian; Giger, Nathalie; Rosset, Jan (January 2015). "Mind the

5. ^ Houston, G F (2001) Public Participation in Democratic Governance in gap: Do proportional electoral systems foster a more equal representation of

South Africa, Pretoria: Human Sciences Research Council HSRC Press women and men, poor and rich?". International Political Science Review. 36

6. ^ Dahl, R A (2005) "Is international democracy possible? A critical view", in (1): 78–98. doi:10.1177/0192512113498830 . S2CID 145633250 .

Sergio Fabbrini (editor): Democracy and Federalism in the European Union 26. ^ Gilens, Martin; Page, Benjamin I. (September 2014). "Testing Theories of

and the United States: Exploring post-national governance: 195 to 204 American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens" .

(Chapter 13), Abingdon on the Thames: Routledge. Perspectives on Politics. 12 (3): 564–581.

7. ^ "CONSTITUTIONAL DEMOCRACY" . www.civiced.org. Retrieved doi:10.1017/S1537592714001595 .

18 November 2019. 27. ^ Carnes, Nicholas (2013). White-Collar Government: The Hidden Role of

8. ^ The Works of the Right Honourable Edmund Burke. Volume I. London: Class in Economic Policy Making. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-

Henry G. Bohn. 1854. pp. 446–8. 226-08728-3.[page needed]

9. ^ Livy; De Sélincourt, A.; Ogilvie, R. M.; Oakley, S. P. (2002). The early 28. ^ Carnes, Nicholas; Lupu, Noam (January 2015). "Rethinking the

history of Rome: books I-V of The history of Rome from its foundations . Comparative Perspective on Class and Representation: Evidence from Latin

Penguin Classics. p. 34. ISBN 0-14-044809-8. America". American Journal of Political Science. 59 (1): 1–18.

10. ^ Watson, 2005, p. 271 doi:10.1111/ajps.12112 .

11. ^ Budge, Ian (2001). "Direct democracy" . In Clarke, Paul A.B.; Foweraker, 29. ^ Giger, Nathalie; Rosset, Jan; Bernauer, Julian (April 2012). "The Poor

Joe (eds.). Encyclopedia of Political Thought. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0- Political Representation of the Poor in a Comparative Perspective".

415-19396-2. Representation. 48 (1): 47–61. doi:10.1080/00344893.2012.653238 .

12. ^ Jobson, Adrian (2012). The First English Revolution: Simon de Montfort, S2CID 154081733 .

Henry III and the Barons' War . Bloomsbury. pp. 173–4. ISBN 978-1- 30. ^ Peters, Yvette; Ensink, Sander J. (4 May 2015). "Differential

84725-226-5. Responsiveness in Europe: The Effects of Preference Difference and

13. ^ "Simon de Montfort: The turning point for democracy that gets Electoral Participation" . West European Politics. 38 (3): 577–600.

overlooked" . BBC. 19 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015; "The doi:10.1080/01402382.2014.973260 . S2CID 153452076 .

January Parliament and how it defined Britain" . The Telegraph. 20 31. ^ Schakel, Wouter; Burgoon, Brian; Hakhverdian, Armen (March 2020).

January 2015. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved "Real but Unequal Representation in Welfare State Reform" . Politics &

28 January 2015. Society. 48 (1): 131–163. doi:10.1177/0032329219897984 .

14. ^ Norgate, Kate (1894). "Montfort, Simon of (1208?-1265)" . In Lee, hdl:1887/138869 . S2CID 214235967 .

Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 38. London: Smith, Elder 32. ^ Zur Soziologie des Parteiwesens in der modernen Demokratie.

& Co. Untersuchungen über die oligarchischen Tendenzen des Gruppenlebens

15. ^ Kopstein, Jeffrey; Lichbach, Mark; Hanson, Stephen E., eds. (2014). (1911, 1925; 1970). Translated as Sociologia del partito politico nella

Comparative Politics: Interests, Identities, and Institutions in a Changing democrazia moderna : studi sulle tendenze oligarchiche degli aggregati

Global Order (4, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 37–9. politici, from the German original by Dr. Alfredo Polledro, revised and

ISBN 978-1139991384. "Britain pioneered the system of liberal democracy expanded (1912). Translated, from the Italian, by Eden and Cedar Paul as

that has now spread in one form or another to most of the world's countries" Political Parties: A Sociological Study of the Oligarchical Tendencies of

16. ^ "Constitutionalism: America & Beyond" . Bureau of International Modern Democracy'" (Hearst's International Library Co., 1915; Free Press,

Information Programs (IIP), U.S. Department of State. Archived from the 1949; Dover Publications, 1959); republished with an introduction by

original on 24 October 2014. Retrieved 30 October 2014. "The earliest, Seymour Martin Lipset (Crowell-Collier, 1962; Transaction Publishers, 1999,

and perhaps greatest, victory for liberalism was achieved in England. The ISBN 0-7658-0469-7); translated in French by S. Jankélévitch, Les partis

rising commercial class that had supported the Tudor monarchy in the 16th politiques. Essai sur les tendances oligarchiques des démocraties, Brussels,

century led the revolutionary battle in the 17th and succeeded in establishing Editions de l'Université de Bruxelles, 2009 (ISBN 978-2-8004-1443-0).

the supremacy of Parliament and, eventually, of the House of Commons. 33. ^ Gemeindefreiheit als Rettung Europas. Grundlinien einer ethischen

What emerged as the distinctive feature of modern constitutionalism was not Geschichtsauffassung. Verlag Bücherfreunde, Basel 1947. In 1983

the insistence on the idea that the king is subject to the law (although this republished under: "Gemeindefreiheit – kommunale Selbstverwaltung"

concept is an essential attribute of all constitutionalism). This notion was (Adolf Gasser/Franz-Ludwig Knemeyer), in de reeks "Studien zur

already well established in the Middle Ages. What was distinctive was the Soziologie", Nymphenburger, München, 1983.

establishment of effective means of political control whereby the rule of law 34. ^ Sørensen, Eva (25 April 2016). "Enhancing policy innovation by

might be enforced. Modern constitutionalism was born with the political redesigning representative democracy" . Policy & Politics. 44 (2): 155–170.

requirement that representative government depended upon the consent of doi:10.1332/030557315X14399997475941 . S2CID 156556922 .

citizen subjects... However, as can be seen through provisions in the 1689 ProQuest 1948833814 .

Bill of Rights, the English Revolution was fought not just to protect the rights 35. ^ Thaa, Winfried (3 May 2016). "Issues and images – new sources of

of property (in the narrow sense) but to establish those liberties which inequality in current representative democracy". Critical Review of

liberals believed essential to human dignity and moral worth. The "rights of International Social and Political Philosophy. 19 (3): 357–375.

man" enumerated in the English Bill of Rights gradually were proclaimed doi:10.1080/13698230.2016.1144859 . S2CID 147669709 .

beyond the boundaries of England, notably in the American Declaration of 36. ^ Razsa, Maple; Kurnik, Andrej (May 2012). "The Occupy Movement in

Independence of 1776 and in the French Declaration of the Rights of Man in Žižek's hometown: Direct democracy and a politics of becoming: The

1789." Occupy Movement in Žižek's hometown". American Ethnologist. 39 (2):

17. ^ "We Hold These Truths to be Self-evident;" An Interdisciplinary Analysis of 238–258. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1425.2012.01361.x .

the Roots of Racism & slavery in America Kenneth N. Addison; Introduction 37. ^ Heckert, Jamie (2010). "Anarchist roots & routes" (PDF). European

P. xxii Journal of Ecopsychology. 1: 19–36.

18. ^ "Expansion of Rights and Liberties" . National Archives. 30 October 38. ^ "1,5". Origins of Democracy in Ancient Greece. Josiah Ober , Robert

2015. Retrieved 27 December 2015. Wallace , Paul Cartledge , Cynthia Farrar (1st ed.). 15 October 2008. pp. 17,

19. ^ "The French Revolution II" . Mars.wnec.edu. Archived from the original 105. ISBN 978-0520258099.

on 27 August 2008. Retrieved 22 August 2010. 39. ^ Bohman, James (1997). Deliberative Democracy (PDF). MIT Press.

External links [ edit ]

Representative democracy at Curlie

Politics portal

Representative democracy at Wikipedia's sister projects: Definitions from Wiktionary Media from Commons Quotations from Wikiquote

Texts from Wikisource

Authority control databases: National France · BnF data · Germany · Israel · United States · Latvia

Categories: Elections Types of democracy Democracy

This page was last edited on 13 February 2024, at 17:19 (UTC).

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License 4.0; additional terms may apply. By using this site, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. Wikipedia® is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit

organization.

Privacy policy About Wikipedia Disclaimers Contact Wikipedia Code of Conduct Developers Statistics Cookie statement Mobile view

You might also like

- List of Forms of GovernmentDocument20 pagesList of Forms of GovernmentMohammed Ali MelhemNo ratings yet

- Different Forms of GovernmentDocument10 pagesDifferent Forms of GovernmentMarivic PuddunanNo ratings yet

- Electoral Engineering PDFDocument291 pagesElectoral Engineering PDFFabrício CarvalhoNo ratings yet

- SPG ELECTION Narrative Report 2022-2023Document7 pagesSPG ELECTION Narrative Report 2022-2023Paul Ivan L. PazNo ratings yet

- GovernmentDocument2 pagesGovernmentJedidiah BetitaNo ratings yet

- Civil Society and Democratic ChangeDocument17 pagesCivil Society and Democratic ChangenandinisundarNo ratings yet

- Government: Basic Forms of GovernmentDocument6 pagesGovernment: Basic Forms of Governmentsuruth242No ratings yet

- What Is DemocracyDocument1 pageWhat Is DemocracyJoseph WelockNo ratings yet

- AmendmentDocument56 pagesAmendmentknajmul430No ratings yet

- Module 2 Political Theory (Eng)Document11 pagesModule 2 Political Theory (Eng)oo7 BondNo ratings yet

- DemocracyDocument45 pagesDemocracyLisa PhillipsNo ratings yet

- Discussion On PoliticsDocument4 pagesDiscussion On PoliticsLani Bernardo CuadraNo ratings yet

- PoliticDocument3 pagesPoliticDika SmileNo ratings yet

- Forms of Government: List of Forms of Governmet:-Part of TheDocument15 pagesForms of Government: List of Forms of Governmet:-Part of TheDaing IrshadNo ratings yet

- Political Philosophy - WikipediaDocument1 pagePolitical Philosophy - Wikipediabaponcsarkar2004No ratings yet

- Political SystemDocument16 pagesPolitical SystemIvybabe PetallarNo ratings yet

- D SystemDocument4 pagesD SystemSchiop CristianNo ratings yet

- Political MovementDocument10 pagesPolitical Movementbvg07No ratings yet

- Political SystemDocument3 pagesPolitical SystemShivanshiKhandelwal100% (1)

- Democracy 2Document7 pagesDemocracy 2nicola maniponNo ratings yet

- LESSON 1: Introduction: The Concepts of Politics and GovernanceDocument28 pagesLESSON 1: Introduction: The Concepts of Politics and GovernanceJohn Dave RacuyaNo ratings yet

- DemocracyDocument46 pagesDemocracyNirmal BhowmickNo ratings yet

- What Is Democracy?: Types of DemocraciesDocument9 pagesWhat Is Democracy?: Types of DemocraciesKong Shi HaoNo ratings yet

- Görkem Tatli 1201190078 Sbky-İşletme Political Parties and Party SystemsDocument3 pagesGörkem Tatli 1201190078 Sbky-İşletme Political Parties and Party SystemsGörkem TatlııNo ratings yet

- Democracy in MalaysiaDocument22 pagesDemocracy in Malaysiashahdhuan89% (9)

- A Short Essay On Political SystemDocument2 pagesA Short Essay On Political SystemSandeepan Banerjee0% (1)

- Political-economic-and-cultural-Aspects (Leigh Teneros)Document10 pagesPolitical-economic-and-cultural-Aspects (Leigh Teneros)Leigh TenerosNo ratings yet

- Party Systems, Electoral Systems and Social Movements ...Document21 pagesParty Systems, Electoral Systems and Social Movements ...miadjafar463No ratings yet

- Class 2 Political Parties, Pressure Groups and DemocratizationDocument5 pagesClass 2 Political Parties, Pressure Groups and Democratizationasifmshai9No ratings yet

- Republicanism, or Representative DemocracyDocument12 pagesRepublicanism, or Representative DemocracyMirceaMariusPetcuNo ratings yet

- Lesson 23 PDFDocument27 pagesLesson 23 PDFanjali9myneniNo ratings yet

- GovernmentDocument2 pagesGovernmentDawn BellNo ratings yet

- Organizational CultureDocument9 pagesOrganizational CultureAshish KumarNo ratings yet

- Parliamentary SystemDocument9 pagesParliamentary SystemJoy GomezNo ratings yet

- Government Systems - Week IIDocument26 pagesGovernment Systems - Week IIsimgenazbingol89No ratings yet

- Democracy - WikipediaDocument72 pagesDemocracy - WikipediaPrimrose NoluthandoNo ratings yet

- Political System: Concept and TypesDocument10 pagesPolitical System: Concept and TypesEnd gameNo ratings yet

- Major Types of Democracy Listening 2Document2 pagesMajor Types of Democracy Listening 2Ellen PatatNo ratings yet

- Comparatve Government Module 3Document12 pagesComparatve Government Module 3Aiza C. Abungan-GalzoteNo ratings yet

- Unit Three: Democracy and Good GovernanceDocument47 pagesUnit Three: Democracy and Good GovernanceAddisu AyeleNo ratings yet

- Consociational Democracy - The Curious Case of India: Submitted By: Pooja SinghDocument3 pagesConsociational Democracy - The Curious Case of India: Submitted By: Pooja SinghPreet SharmaNo ratings yet

- Delegative Democracy: O'Donell, Guillermo ADocument17 pagesDelegative Democracy: O'Donell, Guillermo ABruno Daniel TravailNo ratings yet

- Democracy: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchDocument13 pagesDemocracy: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchVanellope VonschweettzNo ratings yet

- Segundoparcial: 4 HomeworkDocument7 pagesSegundoparcial: 4 Homeworksamed brionesNo ratings yet

- Seminar Paper On Political Party SystemsDocument9 pagesSeminar Paper On Political Party SystemsChike EmeruehNo ratings yet

- PH Politics and GovernanceDocument5 pagesPH Politics and GovernanceCho Madronero LagrosaNo ratings yet

- Abbasa R., Asim M. - What Is Theocratic Democracy - A Case Study of Iranian Political System SyedDocument14 pagesAbbasa R., Asim M. - What Is Theocratic Democracy - A Case Study of Iranian Political System SyedjojoNo ratings yet

- DEMOCRACY Text 2Document3 pagesDEMOCRACY Text 2Jaunur SiharNo ratings yet

- Odonnell Democracy DelegativeDocument17 pagesOdonnell Democracy DelegativeojomuertoNo ratings yet

- Election Law - WikipediaDocument1 pageElection Law - Wikipediabaponcsarkar2004No ratings yet

- Classifying Government: Citation NeededDocument2 pagesClassifying Government: Citation Neededankitabhat93No ratings yet

- CC13 Unit 6 NotesDocument9 pagesCC13 Unit 6 NotesEuphoriaNo ratings yet

- Democracy and DemocratizationDocument22 pagesDemocracy and Democratizationdiosdado estimadaNo ratings yet

- Participatory Democracy in Theory and Practice ADocument21 pagesParticipatory Democracy in Theory and Practice AStanleyNo ratings yet

- The Rise of New Political Parties A Nice Story or A Strong FutureDocument8 pagesThe Rise of New Political Parties A Nice Story or A Strong FutureNordsci ConferenceNo ratings yet

- Public Policy 1st Lect PDFDocument8 pagesPublic Policy 1st Lect PDFAhsan Ali Ahsan AliNo ratings yet

- POL303Document6 pagesPOL303Leng ChhunNo ratings yet

- Political ScienceDocument62 pagesPolitical ScienceJashanpreet KaurNo ratings yet

- Democracy - WikipediaDocument74 pagesDemocracy - WikipediaAbuzar Khan SU 21 O2 OO1 OO4No ratings yet

- MODULE 2 PolGovDocument12 pagesMODULE 2 PolGovEugene TongolNo ratings yet

- Kannur Kotta Rape Case - WikipediaDocument1 pageKannur Kotta Rape Case - Wikipediabaponcsarkar2004No ratings yet

- Jhabua Nuns Rape Case - WikipediaDocument1 pageJhabua Nuns Rape Case - Wikipediabaponcsarkar2004No ratings yet

- 2020 Hathras Gang Rape and Murder - WikipediaDocument1 page2020 Hathras Gang Rape and Murder - Wikipediabaponcsarkar2004No ratings yet

- English Unjust Enrichment Law - WikipediaDocument1 pageEnglish Unjust Enrichment Law - Wikipediabaponcsarkar2004No ratings yet

- Political Philosophy - WikipediaDocument1 pagePolitical Philosophy - Wikipediabaponcsarkar2004No ratings yet

- Law of Obligations - WikipediaDocument1 pageLaw of Obligations - Wikipediabaponcsarkar2004No ratings yet

- Article 365 of The Sri Lankan Penal Code - WikipediaDocument1 pageArticle 365 of The Sri Lankan Penal Code - Wikipediabaponcsarkar2004No ratings yet

- Mathura Rape Case - WikipediaDocument1 pageMathura Rape Case - Wikipediabaponcsarkar2004No ratings yet

- Auto Shankar - WikipediaDocument1 pageAuto Shankar - Wikipediabaponcsarkar2004No ratings yet

- Rape in India - WikipediaDocument1 pageRape in India - Wikipediabaponcsarkar2004No ratings yet

- 1990 Bantala Rape Case - WikipediaDocument1 page1990 Bantala Rape Case - Wikipediabaponcsarkar2004No ratings yet

- Merger of Kanyakumari With Madras State - WikipediaDocument3 pagesMerger of Kanyakumari With Madras State - WikipediaARIF AHAMEDNo ratings yet

- Visualizing The Environment Canadian 1st Edition Berg Test BankDocument35 pagesVisualizing The Environment Canadian 1st Edition Berg Test Bankbrakemancullet.qzp7100% (22)

- Problem - Solving OrganizerDocument2 pagesProblem - Solving OrganizerannaallagaNo ratings yet

- Statistics For The Behavioral Sciences 4th Edition Nolan Test BankDocument35 pagesStatistics For The Behavioral Sciences 4th Edition Nolan Test Banksurgicalyttriumj52b100% (22)

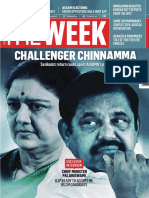

- Challenger Chinnamma: Sasikala's Return Could Upset AIADMK's PlansDocument39 pagesChallenger Chinnamma: Sasikala's Return Could Upset AIADMK's PlansTrinetra AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Iowa Caucus ExplainedDocument2 pagesIowa Caucus ExplainedSagar ShahNo ratings yet

- Reconstruction Interactive NotebookDocument9 pagesReconstruction Interactive Notebookshelidelmoral24No ratings yet

- Martial Law During and PostDocument6 pagesMartial Law During and PostLeoncio BocoNo ratings yet

- Election of The PresidentDocument10 pagesElection of The PresidentShambhavi ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- The Nubian News & El Latino News - Septiembre 2023Document12 pagesThe Nubian News & El Latino News - Septiembre 2023Marcos Tamayo CabreraNo ratings yet

- SSG FormsDocument2 pagesSSG Formssir jjNo ratings yet

- Congressional WebquestDocument8 pagesCongressional Webquestsamocamo 123No ratings yet

- Pura VillanuevaDocument3 pagesPura VillanuevaMaria AngeliNo ratings yet

- Compare Contrast American Ancient Greece Democracy J SerafinDocument11 pagesCompare Contrast American Ancient Greece Democracy J Serafinapi-213888247No ratings yet

- Comparative Government and Politics 3Document3 pagesComparative Government and Politics 3ROsemarie JimenezNo ratings yet

- Civics: Give Short Answers of The Following QuestionsDocument3 pagesCivics: Give Short Answers of The Following QuestionsPrince GangwarNo ratings yet

- Case DigestsDocument5 pagesCase DigestsChristina AureNo ratings yet

- 2023 Cve g10 Updated Notes LatestDocument49 pages2023 Cve g10 Updated Notes LatestElizabeth MunthaliNo ratings yet

- Revised List of Candidates: Election Rachna Club Toba Tek Singh Sr. No. Name of Candidate Father's NameDocument2 pagesRevised List of Candidates: Election Rachna Club Toba Tek Singh Sr. No. Name of Candidate Father's NameMuhammad ShahzadNo ratings yet

- WHQR Interview Transcript: Congressman David RouzerDocument15 pagesWHQR Interview Transcript: Congressman David RouzerBen SchachtmanNo ratings yet

- Alexei Anatolievich Navalny (Russian: АлексейDocument62 pagesAlexei Anatolievich Navalny (Russian: АлексейStojan SavicNo ratings yet

- Certificate of Candidacy For The School Level Supreme Student GovernmentDocument2 pagesCertificate of Candidacy For The School Level Supreme Student Governmentjonelle villarizaNo ratings yet

- CCES Guide 2016 PDFDocument182 pagesCCES Guide 2016 PDFTimon WapenaarNo ratings yet

- The Week UK - 03 November 2019Document66 pagesThe Week UK - 03 November 2019Pere-Ferran Andúgar LópezNo ratings yet

- The Newly Elected Purok Offcials 2013-2015 of Barangay Labangal.Document43 pagesThe Newly Elected Purok Offcials 2013-2015 of Barangay Labangal.Barangay Labangal Lgu100% (2)

- ISC Political Science Question Paper 2012 Solved For Class 12Document9 pagesISC Political Science Question Paper 2012 Solved For Class 12AVNISH PRAKASHNo ratings yet

- Bantay Republic Act vs. COMELEC GR No. 177271 May 4, 2007Document5 pagesBantay Republic Act vs. COMELEC GR No. 177271 May 4, 2007Krisleen AbrenicaNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of Complaint: Page 3 1 VI. Certification Page 6Document12 pagesAffidavit of Complaint: Page 3 1 VI. Certification Page 6Trevor BallantyneNo ratings yet