Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Major Depressive Disorder - Wikipedia

Uploaded by

Badhon Chandra SarkarCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Major Depressive Disorder - Wikipedia

Uploaded by

Badhon Chandra SarkarCopyright:

Available Formats

Search Wikipedia Search Create account Log in

Major depressive disorder 88 languages

Contents hide Article Talk Read View source View history Tools

(Top) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Symptoms and signs (Redirected from Clinical depression)

Cause

For other types of depression, see Mood disorder.

Pathophysiology Not to be confused with Depression (mood).

Diagnosis Major depressive disorder (MDD), also known as clinical depression, is a mental disorder[9]

Major depressive disorder

Screening and prevention characterized by at least two weeks of pervasive low mood, low self-esteem, and loss of interest or

Other names Clinical depression, major

pleasure in normally enjoyable activities. Introduced by a group of US clinicians in the mid-1970s,[10] the

Management depression, unipolar

term was adopted by the American Psychiatric Association for this symptom cluster under mood disorders depression, unipolar disorder,

Prognosis in the 1980 version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III), and has become recurrent depression

Epidemiology widely used since.

History The diagnosis of major depressive disorder is based on the person's reported experiences, behavior

Society and culture reported by relatives or friends, and a mental status examination.[11] There is no laboratory test for the

disorder, but testing may be done to rule out physical conditions that can cause similar symptoms.[11] The

References

most common time of onset is in a person's 20s,[3][4] with females affected about twice as often as males.[4]

The course of the disorder varies widely, from one episode lasting months to a lifelong disorder with

recurrent major depressive episodes.

Those with major depressive disorder are typically treated with psychotherapy and antidepressant

medication.[1] Medication appears to be effective, but the effect may be significant only in the most severely

depressed.[12][13] Hospitalization (which may be involuntary) may be necessary in cases with associated

self-neglect or a significant risk of harm to self or others. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) may be

considered if other measures are not effective.[1]

Sorrowing Old Man (At Eternity's Gate)

Major depressive disorder is believed to be caused by a combination of genetic, environmental, and

by Vincent van Gogh (1890)

psychological factors,[1] with about 40% of the risk being genetic.[5] Risk factors include a family history of

Specialty Psychiatry, clinical psychology

the condition, major life changes, certain medications, chronic health problems, and substance use

Symptoms Low mood, low self-esteem,

disorders.[1][5] It can negatively affect a person's personal life, work life, or education, and cause issues loss of interest in normally

with a person's sleeping habits, eating habits, and general health.[1][5] Major depressive disorder affected enjoyable activities, low

approximately 163 million people (2% of the world's population) in 2017.[8] The percentage of people who energy, pain without a clear

are affected at one point in their life varies from 7% in Japan to 21% in France.[4] Lifetime rates are higher cause,[1] disturbed sleep

pattern (insomnia or

in the developed world (15%) compared to the developing world (11%).[4] The disorder causes the second-

hypersomnia)

most years lived with disability, after lower back pain.[14]

Complications Self-harm, suicide[2]

Usual onset Age 20s[3][4]

Symptoms and signs Duration > 2 weeks[1]

Major depression significantly affects a person's family and personal relationships, work or school life, Causes Environmental (e.g. adverse

life experiences), genetic

sleeping and eating habits, and general health.[15] A person having a major depressive episode usually

predisposition, psychological

exhibits a low mood, which pervades all aspects of life, and an inability to experience pleasure in previously factors such as stress[5]

enjoyable activities.[16] Depressed people may be preoccupied with—or ruminate over—thoughts and

Risk factors Family history, major life

feelings of worthlessness, inappropriate guilt or regret, helplessness or hopelessness.[17] changes, certain medications,

chronic health problems,

Other symptoms of depression include poor concentration and memory,[18] withdrawal from social substance use disorder[1][5]

situations and activities, reduced sex drive, irritability, and thoughts of death or suicide. Insomnia is Differential Bipolar disorder, ADHD,

common; in the typical pattern, a person wakes very early and cannot get back to sleep. Hypersomnia, or diagnosis sadness[6]

oversleeping, can also happen,[19] as well as day-night rhythm disturbances, such as diurnal mood Treatment Psychotherapy,

variation.[20] Some antidepressants may also cause insomnia due to their stimulating effect.[21] In severe antidepressant medication,

cases, depressed people may have psychotic symptoms. These symptoms include delusions or, less electroconvulsive therapy,

transcranial magnetic

commonly, hallucinations, usually unpleasant.[22] People who have had previous episodes with psychotic

stimulation, exercise[1][7]

symptoms are more likely to have them with future episodes.[23]

Medication Antidepressants

A depressed person may report multiple physical symptoms such as fatigue, headaches, or digestive Frequency 163 million (2017)[8]

problems; physical complaints are the most common presenting problem in developing countries,

according to the World Health Organization's criteria for depression.[24] Appetite often decreases, resulting in

weight loss, although increased appetite and weight gain occasionally occur.[25] Family and friends may notice

agitation or lethargy.[19] Older depressed people may have cognitive symptoms of recent onset, such as

forgetfulness,[26] and a more noticeable slowing of movements.[27]

Depressed children may often display an irritable rather than a depressed mood;[19] most lose interest in school

and show a steep decline in academic performance.[28] Diagnosis may be delayed or missed when symptoms

are interpreted as "normal moodiness."[25] Elderly people may not present with classical depressive

symptoms.[29] Diagnosis and treatment is further complicated in that the elderly are often simultaneously treated

with a number of other drugs, and often have other concurrent diseases.[29]

Cause

Further information: Biology of depression and Epigenetics of depression

The etiology of depression is not yet fully understood.[31][32][33][34] The biopsychosocial model proposes that An 1892 lithograph of a woman

biological, psychological, and social factors all play a role in causing depression.[5][35] The diathesis–stress diagnosed with melancholia

model specifies that depression results when a preexisting vulnerability, or diathesis, is activated by stressful life

events. The preexisting vulnerability can be either genetic,[36][37] implying an interaction between nature and

nurture, or schematic, resulting from views of the world learned in childhood.[38] American psychiatrist Aaron

Beck suggested that a triad of automatic and spontaneous negative thoughts about the self, the world or

environment, and the future may lead to other depressive signs and symptoms.[39][40]

Genetics

Genes play a major role in the development of depression.[41] Family and twin studies find that nearly 40% of

individual differences in risk for major depressive disorder can be explained by genetic factors.[42] Like most A cup analogy demonstrating the

diathesis–stress model that under the

psychiatric disorders, major depressive disorder is likely influenced by many individual genetic changes.[43] In

same amount of stressors, person 2 is

2018, a genome-wide association study discovered 44 genetic variants linked to risk for major depression;[44] a more vulnerable than person 1,

2019 study found 102 variants in the genome linked to depression.[45] However, it appears that major depression because of their predisposition[30]

is less heritable compared to bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.[46][47] Research focusing on specific candidate

genes has been criticized for its tendency to generate false positive findings.[48] There are also other efforts to

examine interactions between life stress and polygenic risk for depression.[49]

Other health problems

Depression can also arise after a chronic or terminal medical condition, such as HIV/AIDS or asthma, and may be labeled "secondary depression."[50][51]

It is unknown whether the underlying diseases induce depression through effect on quality of life, or through shared etiologies (such as degeneration of

the basal ganglia in Parkinson's disease or immune dysregulation in asthma).[52] Depression may also be iatrogenic (the result of healthcare), such as

drug-induced depression. Therapies associated with depression include interferons, beta-blockers, isotretinoin, contraceptives,[53] cardiac agents,

anticonvulsants, antimigraine drugs, antipsychotics, and hormonal agents such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist (GnRH agonist).[54] Celiac

disease is another possible contributing factor.[55]

Substance use in early age is associated with increased risk of developing depression later in life.[56] Depression occurring after giving birth is called

postpartum depression and is thought to be the result of hormonal changes associated with pregnancy.[57] Seasonal affective disorder, a type of

depression associated with seasonal changes in sunlight, is thought to be triggered by decreased sunlight.[58] Vitamin B2, B6 and B12 deficiency may

cause depression in females.[59]

Environmental

Adverse childhood experiences (incorporating childhood abuse, neglect and family dysfunction) markedly increase the risk of major depression,

especially if more than one type.[5] Childhood trauma also correlates with severity of depression, poor responsiveness to treatment and length of illness.

Some are more susceptible than others to developing mental illness such as depression after trauma, and various genes have been suggested to control

susceptibility.[60] Couples in unhappy marriages have a higher risk of developing clinical depression.[61]

There appears to be a link between air pollution and depression and suicide. There may be an association between long-term PM2.5 exposure and

depression, and a possible association between short-term PM10 exposure and suicide.[62]

Pathophysiology

Further information: Biology of depression and Epigenetics of depression

The pathophysiology of depression is not completely understood, but current theories center around monoaminergic systems, the circadian rhythm,

immunological dysfunction, HPA-axis dysfunction and structural or functional abnormalities of emotional circuits.

Derived from the effectiveness of monoaminergic drugs in treating depression, the monoamine theory posits that insufficient activity of monoamine

neurotransmitters is the primary cause of depression. Evidence for the monoamine theory comes from multiple areas. First, acute depletion of tryptophan

—a necessary precursor of serotonin and a monoamine—can cause depression in those in remission or relatives of people who are depressed,

suggesting that decreased serotonergic neurotransmission is important in depression.[63] Second, the correlation between depression risk and

polymorphisms in the 5-HTTLPR gene, which codes for serotonin receptors, suggests a link. Third, decreased size of the locus coeruleus, decreased

activity of tyrosine hydroxylase, increased density of alpha-2 adrenergic receptor, and evidence from rat models suggest decreased adrenergic

neurotransmission in depression.[64] Furthermore, decreased levels of homovanillic acid, altered response to dextroamphetamine, responses of

depressive symptoms to dopamine receptor agonists, decreased dopamine receptor D1 binding in the striatum,[65] and polymorphism of dopamine

receptor genes implicate dopamine, another monoamine, in depression.[66][67] Lastly, increased activity of monoamine oxidase, which degrades

monoamines, has been associated with depression.[68] However, the monoamine theory is inconsistent with observations that serotonin depletion does

not cause depression in healthy persons, that antidepressants instantly increase levels of monoamines but take weeks to work, and the existence of

atypical antidepressants which can be effective despite not targeting this pathway.[69]

One proposed explanation for the therapeutic lag, and further support for the deficiency of monoamines, is a desensitization of self-inhibition in raphe

nuclei by the increased serotonin mediated by antidepressants.[70] However, disinhibition of the dorsal raphe has been proposed to occur as a result of

decreased serotonergic activity in tryptophan depletion, resulting in a depressed state mediated by increased serotonin. Further countering the

monoamine hypothesis is the fact that rats with lesions of the dorsal raphe are not more depressive than controls, the finding of increased jugular 5-HIAA

in people who are depressed that normalized with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) treatment, and the preference for carbohydrates in people

who are depressed.[71] Already limited, the monoamine hypothesis has been further oversimplified when presented to the general public.[72] A 2022

review found no consistent evidence supporting the serotonin hypothesis, linking serotonin levels and depression.[73]

Immune system abnormalities have been observed, including increased levels of cytokines involved in generating sickness behavior (which shares

overlap with depression).[74][75][76] The effectiveness of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and cytokine inhibitors in treating depression,[77]

and normalization of cytokine levels after successful treatment further suggest immune system abnormalities in depression.[78]

HPA-axis abnormalities have been suggested in depression given the association of CRHR1 with depression and the increased frequency of

dexamethasone test non-suppression in people who are depressed. However, this abnormality is not adequate as a diagnosis tool, because its sensitivity

is only 44%.[79] These stress-related abnormalities are thought to be the cause of hippocampal volume reductions seen in people who are depressed.[80]

Furthermore, a meta-analysis yielded decreased dexamethasone suppression, and increased response to psychological stressors.[81] Further abnormal

results have been obscured with the cortisol awakening response, with increased response being associated with depression.[82]

Theories unifying neuroimaging findings have been proposed. The first model proposed is the limbic-cortical model, which involves hyperactivity of the

ventral paralimbic regions and hypoactivity of frontal regulatory regions in emotional processing.[83] Another model, the cortico-striatal model, suggests

that abnormalities of the prefrontal cortex in regulating striatal and subcortical structures result in depression.[84] Another model proposes hyperactivity of

salience structures in identifying negative stimuli, and hypoactivity of cortical regulatory structures resulting in a negative emotional bias and depression,

consistent with emotional bias studies.[85]

Diagnosis

Clinical assessment

Further information: Rating scales for depression

A diagnostic assessment may be conducted by a suitably trained general practitioner, or by a psychiatrist or

psychologist,[15] who records the person's current circumstances, biographical history, current symptoms, family

history, and alcohol and drug use. The assessment also includes a mental state examination, which is an

assessment of the person's current mood and thought content, in particular the presence of themes of

hopelessness or pessimism, self-harm or suicide, and an absence of positive thoughts or plans.[15] Specialist

mental health services are rare in rural areas, and thus diagnosis and management is left largely to primary-care

clinicians.[86] This issue is even more marked in developing countries.[87] Rating scales are not used to diagnose

depression, but they provide an indication of the severity of symptoms for a time period, so a person who scores

above a given cut-off point can be more thoroughly evaluated for a depressive disorder diagnosis. Several rating

scales are used for this purpose;[88] these include the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression,[89] the Beck

Depression Inventory[90] or the Suicide Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised.[91]

Primary-care physicians have more difficulty with underrecognition and undertreatment of depression compared

to psychiatrists. These cases may be missed because for some people with depression, physical symptoms

often accompany depression. In addition, there may also be barriers related to the person, provider, and/or the

medical system. Non-psychiatrist physicians have been shown to miss about two-thirds of cases, although there

Caricature of a man with is some evidence of improvement in the number of missed cases.[92]

depression

A doctor generally performs a medical examination and selected investigations to rule out other causes of

depressive symptoms. These include blood tests measuring TSH and thyroxine to exclude hypothyroidism; basic

electrolytes and serum calcium to rule out a metabolic disturbance; and a full blood count including ESR to rule out a systemic infection or chronic

disease.[93] Adverse affective reactions to medications or alcohol misuse may be ruled out, as well. Testosterone levels may be evaluated to diagnose

hypogonadism, a cause of depression in men.[94] Vitamin D levels might be evaluated, as low levels of vitamin D have been associated with greater risk

for depression.[95] Subjective cognitive complaints appear in older depressed people, but they can also be indicative of the onset of a dementing

disorder, such as Alzheimer's disease.[96][97] Cognitive testing and brain imaging can help distinguish depression from dementia.[98] A CT scan can

exclude brain pathology in those with psychotic, rapid-onset or otherwise unusual symptoms.[99] No biological tests confirm major depression.[100] In

general, investigations are not repeated for a subsequent episode unless there is a medical indication.

DSM and ICD criteria

The most widely used criteria for diagnosing depressive conditions are found in the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

of Mental Disorders (DSM) and the World Health Organization's International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD).

The latter system is typically used in European countries, while the former is used in the US and many other non-European nations,[101] and the authors

of both have worked towards conforming one with the other.[102] Both DSM and ICD mark out typical (main) depressive symptoms.[103] The most recent

edition of the DSM is the Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR),[104] and the most recent edition of the ICD is the Eleventh Edition (ICD-11).[105]

Under mood disorders, ICD-11 classifies major depressive disorder as either single episode depressive disorder (where there is no history of depressive

episodes, or of mania) or recurrent depressive disorder (where there is a history of prior episodes, with no history of mania).[106] ICD-11 symptoms,

present nearly every day for at least two weeks, are a depressed mood or anhedonia, accompanied by other symptoms such as "difficulty concentrating,

feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt, hopelessness, recurrent thoughts of death or suicide, changes in appetite or sleep,

psychomotor agitation or retardation, and reduced energy or fatigue."[106] These symptoms must affect work, social, or domestic activities. The ICD-11

system allows further specifiers for the current depressive episode: the severity (mild, moderate, severe, unspecified); the presence of psychotic

symptoms (with or without psychotic symptoms); and the degree of remission if relevant (currently in partial remission, currently in full remission).[106]

These two disorders are classified as "Depressive disorders", in the category of "Mood disorders".[106]

According to DSM-5, there are two main depressive symptoms: a depressed mood, and loss of interest/pleasure in activities (anhedonia). These

symptoms, as well as five out of the nine more specific symptoms listed, must frequently occur for more than two weeks (to the extent in which it impairs

functioning) for the diagnosis.[107][failed verification] Major depressive disorder is classified as a mood disorder in the DSM-5.[108] The diagnosis hinges on

the presence of single or recurrent major depressive episodes.[109] Further qualifiers are used to classify both the episode itself and the course of the

disorder. The category Unspecified Depressive Disorder is diagnosed if the depressive episode's manifestation does not meet the criteria for a major

depressive episode.[108]

Major depressive episode

Main article: Major depressive episode

A major depressive episode is characterized by the presence of a severely depressed mood that persists for at least two weeks.[25] Episodes may be

isolated or recurrent and are categorized as mild (few symptoms in excess of minimum criteria), moderate, or severe (marked impact on social or

occupational functioning). An episode with psychotic features—commonly referred to as psychotic depression—is automatically rated as severe.[108] If

the person has had an episode of mania or markedly elevated mood, a diagnosis of bipolar disorder is made instead. Depression without mania is

sometimes referred to as unipolar because the mood remains at one emotional state or "pole".[110]

Bereavement is not an exclusion criterion in the DSM-5, and it is up to the clinician to distinguish between normal reactions to a loss and MDD. Excluded

are a range of related diagnoses, including dysthymia, which involves a chronic but milder mood disturbance;[111] recurrent brief depression, consisting of

briefer depressive episodes;[112][113] minor depressive disorder, whereby only some symptoms of major depression are present;[114] and adjustment

disorder with depressed mood, which denotes low mood resulting from a psychological response to an identifiable event or stressor.[115]

Subtypes

The DSM-5 recognizes six further subtypes of MDD, called specifiers, in addition to noting the length, severity and presence of psychotic features:

"Melancholic depression" is characterized by a loss of pleasure in most or all activities, a failure of reactivity to pleasurable stimuli, a quality of

depressed mood more pronounced than that of grief or loss, a worsening of symptoms in the morning hours, early-morning waking, psychomotor

retardation, excessive weight loss (not to be confused with anorexia nervosa), or excessive guilt.[116]

"Atypical depression" is characterized by mood reactivity (paradoxical anhedonia) and positivity, significant weight gain or increased appetite (comfort

eating), excessive sleep or sleepiness (hypersomnia), a sensation of heaviness in limbs known as leaden paralysis, and significant long-term social

impairment as a consequence of hypersensitivity to perceived interpersonal rejection.[117]

"Catatonic depression" is a rare and severe form of major depression involving disturbances of motor behavior and other symptoms. Here, the person

is mute and almost stuporous, and either remains immobile or exhibits purposeless or even bizarre movements. Catatonic symptoms also occur in

schizophrenia or in manic episodes, or may be caused by neuroleptic malignant syndrome.[118]

"Depression with anxious distress" was added into the DSM-5 as a means to emphasize the common co-occurrence between depression or mania

and anxiety, as well as the risk of suicide of depressed individuals with anxiety. Specifying in such a way can also help with the prognosis of those

diagnosed with a depressive or bipolar disorder.[108]

"Depression with peri-partum onset" refers to the intense, sustained and sometimes disabling depression experienced by women after giving birth or

while a woman is pregnant. DSM-IV-TR used the classification "postpartum depression," but this was changed to not exclude cases of depressed

woman during pregnancy. Depression with peripartum onset has an incidence rate of 3–6% among new mothers. The DSM-5 mandates that to

qualify as depression with peripartum onset, onset occurs during pregnancy or within one month of delivery.[119]

"Seasonal affective disorder" (SAD) is a form of depression in which depressive episodes come on in the autumn or winter, and resolve in spring. The

diagnosis is made if at least two episodes have occurred in colder months with none at other times, over a two-year period or longer.[120]

Differential diagnoses

Main article: Differential diagnoses of depression

To confirm major depressive disorder as the most likely diagnosis, other potential diagnoses must be considered, including dysthymia, adjustment

disorder with depressed mood, or bipolar disorder. Dysthymia is a chronic, milder mood disturbance in which a person reports a low mood almost daily

over a span of at least two years. The symptoms are not as severe as those for major depression, although people with dysthymia are vulnerable to

secondary episodes of major depression (sometimes referred to as double depression).[111] Adjustment disorder with depressed mood is a mood

disturbance appearing as a psychological response to an identifiable event or stressor, in which the resulting emotional or behavioral symptoms are

significant but do not meet the criteria for a major depressive episode.[115]

Other disorders need to be ruled out before diagnosing major depressive disorder. They include depressions due to physical illness, medications, and

substance use disorders. Depression due to physical illness is diagnosed as a mood disorder due to a general medical condition. This condition is

determined based on history, laboratory findings, or physical examination. When the depression is caused by a medication, non-medical use of a

psychoactive substance, or exposure to a toxin, it is then diagnosed as a specific mood disorder (previously called substance-induced mood

disorder).[121]

Screening and prevention

Preventive efforts may result in decreases in rates of the condition of between 22 and 38%.[122] Since 2016, the United States Preventive Services Task

Force (USPSTF) has recommended screening for depression among those over the age 12;[123][124] though a 2005 Cochrane review found that the

routine use of screening questionnaires has little effect on detection or treatment.[125] Screening the general population is not recommended by

authorities in the UK or Canada.[126]

Behavioral interventions, such as interpersonal therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy, are effective at preventing new onset depression.[122][127][128]

Because such interventions appear to be most effective when delivered to individuals or small groups, it has been suggested that they may be able to

reach their large target audience most efficiently through the Internet.[129]

The Netherlands mental health care system provides preventive interventions, such as the "Coping with Depression" course (CWD) for people with sub-

threshold depression. The course is claimed to be the most successful of psychoeducational interventions for the treatment and prevention of depression

(both for its adaptability to various populations and its results), with a risk reduction of 38% in major depression and an efficacy as a treatment comparing

favorably to other psychotherapies.[127][130]

Management

Main article: Management of depression

The most common and effective treatments for depression are psychotherapy, medication, and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT); a combination of

treatments is the most effective approach when depression is resistant to treatment.[131] American Psychiatric Association treatment guidelines

recommend that initial treatment should be individually tailored based on factors including severity of symptoms, co-existing disorders, prior treatment

experience, and personal preference. Options may include pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, exercise, ECT, transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) or

light therapy. Antidepressant medication is recommended as an initial treatment choice in people with mild, moderate, or severe major depression, and

should be given to all people with severe depression unless ECT is planned.[132] There is evidence that collaborative care by a team of health care

practitioners produces better results than routine single-practitioner care.[133]

Psychotherapy is the treatment of choice (over medication) for people under 18,[134] and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), third wave CBT and

interpersonal therapy may help prevent depression.[135] The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) 2004 guidelines indicate that

antidepressants should not be used for the initial treatment of mild depression because the risk-benefit ratio is poor. The guidelines recommend that

antidepressants treatment in combination with psychosocial interventions should be considered for:[134]

People with a history of moderate or severe depression

Those with mild depression that has been present for a long period

As a second line treatment for mild depression that persists after other interventions

As a first line treatment for moderate or severe depression.

The guidelines further note that antidepressant treatment should be continued for at least six months to reduce the risk of relapse, and that SSRIs are

better tolerated than tricyclic antidepressants.[134]

Treatment options are more limited in developing countries, where access to mental health staff, medication, and psychotherapy is often difficult.

Development of mental health services is minimal in many countries; depression is viewed as a phenomenon of the developed world despite evidence to

the contrary, and not as an inherently life-threatening condition.[136] There is insufficient evidence to determine the effectiveness of psychological versus

medical therapy in children.[137]

Lifestyle

Further information: Neurobiological effects of physical exercise § Major depressive disorder

Physical exercise has been found to be effective for major depression, and may be recommended to people who

are willing, motivated, and healthy enough to participate in an exercise program as treatment.[138] It is equivalent

to the use of medications or psychological therapies in most people.[7] In older people it does appear to decrease

depression.[139] Sleep and diet may also play a role in depression, and interventions in these areas may be an

effective add-on to conventional methods.[140] In observational studies, smoking cessation has benefits in

depression as large as or larger than those of medications.[141]

Talking therapies

See also: Behavioral theories of depression Physical exercise is one

recommended way to manage mild

Talking therapy (psychotherapy) can be delivered to individuals, groups, or families by mental health depression.

professionals, including psychotherapists, psychiatrists, psychologists, clinical social workers, counselors, and

psychiatric nurses. A 2012 review found psychotherapy to be better than no treatment but not other

treatments.[142] With more complex and chronic forms of depression, a combination of medication and psychotherapy may be used.[143][144] There is

moderate-quality evidence that psychological therapies are a useful addition to standard antidepressant treatment of treatment-resistant depression in

the short term.[145] Psychotherapy has been shown to be effective in older people.[146][147] Successful psychotherapy appears to reduce the recurrence

of depression even after it has been stopped or replaced by occasional booster sessions.

The most-studied form of psychotherapy for depression is CBT, which teaches clients to challenge self-defeating, but enduring ways of thinking

(cognitions) and change counter-productive behaviors. CBT can perform as well as antidepressants in people with major depression.[148] CBT has the

most research evidence for the treatment of depression in children and adolescents, and CBT and interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) are preferred

therapies for adolescent depression.[149] In people under 18, according to the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, medication should be

offered only in conjunction with a psychological therapy, such as CBT, interpersonal therapy, or family therapy.[150] Several variables predict success for

cognitive behavioral therapy in adolescents: higher levels of rational thoughts, less hopelessness, fewer negative thoughts, and fewer cognitive

distortions.[151] CBT is particularly beneficial in preventing relapse.[152][153] Cognitive behavioral therapy and occupational programs (including

modification of work activities and assistance) have been shown to be effective in reducing sick days taken by workers with depression.[154] Several

variants of cognitive behavior therapy have been used in those with depression, the most notable being rational emotive behavior therapy,[155] and

mindfulness-based cognitive therapy.[156] Mindfulness-based stress reduction programs may reduce depression symptoms.[157][158] Mindfulness

programs also appear to be a promising intervention in youth.[159] Problem solving therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and interpersonal therapy are

effective interventions in the elderly.[160]

Psychoanalysis is a school of thought, founded by Sigmund Freud, which emphasizes the resolution of unconscious mental conflicts.[161] Psychoanalytic

techniques are used by some practitioners to treat clients presenting with major depression.[162] A more widely practiced therapy, called psychodynamic

psychotherapy, is in the tradition of psychoanalysis but less intensive, meeting once or twice a week. It also tends to focus more on the person's

immediate problems, and has an additional social and interpersonal focus.[163] In a meta-analysis of three controlled trials of Short Psychodynamic

Supportive Psychotherapy, this modification was found to be as effective as medication for mild to moderate depression.[164]

Antidepressants

Conflicting results have arisen from studies that look at the effectiveness of antidepressants in people with acute,

mild to moderate depression.[165] A review commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care

Excellence (UK) concluded that there is strong evidence that SSRIs, such as escitalopram, paroxetine, and

sertraline, have greater efficacy than placebo on achieving a 50% reduction in depression scores in moderate

and severe major depression, and that there is some evidence for a similar effect in mild depression.[166]

Similarly, a Cochrane systematic review of clinical trials of the generic tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline

concluded that there is strong evidence that its efficacy is superior to placebo.[167] Antidepressants work less

well for the elderly than for younger individuals with depression.[160]

To find the most effective antidepressant medication with minimal side-effects, the dosages can be adjusted, and

if necessary, combinations of different classes of antidepressants can be tried. Response rates to the first Sertraline (Zoloft) is used primarily

to treat major depression in adults.

antidepressant administered range from 50 to 75%, and it can take at least six to eight weeks from the start of

medication to improvement.[132][168] Antidepressant medication treatment is usually continued for 16 to 20 weeks

after remission, to minimize the chance of recurrence,[132] and even up to one year of continuation is recommended.[169] People with chronic depression

may need to take medication indefinitely to avoid relapse.[15]

SSRIs are the primary medications prescribed, owing to their relatively mild side-effects, and because they are less toxic in overdose than other

antidepressants.[170] People who do not respond to one SSRI can be switched to another antidepressant, and this results in improvement in almost 50%

of cases.[171] Another option is to augment the atypical antidepressant bupropion to the SSRI as an adjunctive treatment.[172] Venlafaxine, an

antidepressant with a different mechanism of action, may be modestly more effective than SSRIs.[173] However, venlafaxine is not recommended in the

UK as a first-line treatment because of evidence suggesting its risks may outweigh benefits,[174] and it is specifically discouraged in children and

adolescents as it increases the risk of suicidal thoughts or attempts.[175][176][177][178][179][180][181]

For children and adolescents with moderate-to-severe depressive disorder, fluoxetine seems to be the best treatment (either with or without cognitive

behavioural therapy) but more research is needed to be certain.[182][176][183][177] Sertraline, escitalopram, duloxetine might also help in reducing

symptoms. Some antidepressants have not been shown to be effective.[184][176] Medications are not recommended in children with mild disease.[185]

There is also insufficient evidence to determine effectiveness in those with depression complicated by dementia.[186] Any antidepressant can cause low

blood sodium levels;[187] nevertheless, it has been reported more often with SSRIs.[170] It is not uncommon for SSRIs to cause or worsen insomnia; the

sedating atypical antidepressant mirtazapine can be used in such cases.[188][189]

Irreversible monoamine oxidase inhibitors, an older class of antidepressants, have been plagued by potentially life-threatening dietary and drug

interactions. They are still used only rarely, although newer and better-tolerated agents of this class have been developed.[190] The safety profile is

different with reversible monoamine oxidase inhibitors, such as moclobemide, where the risk of serious dietary interactions is negligible and dietary

restrictions are less strict.[191]

It is unclear whether antidepressants affect a person's risk of suicide.[192] For children, adolescents, and probably young adults between 18 and 24 years

old, there is a higher risk of both suicidal ideations and suicidal behavior in those treated with SSRIs.[193][194] For adults, it is unclear whether SSRIs

affect the risk of suicidality. One review found no connection;[195] another an increased risk;[196] and a third no risk in those 25–65 years old and a

decreased risk in those more than 65.[197] A black box warning was introduced in the United States in 2007 on SSRIs and other antidepressant

medications due to the increased risk of suicide in people younger than 24 years old.[198] Similar precautionary notice revisions were implemented by the

Japanese Ministry of Health.[199]

Other medications and supplements

The combined use of antidepressants plus benzodiazepines demonstrates improved effectiveness when compared to antidepressants alone, but these

effects may not endure. The addition of a benzodiazepine is balanced against possible harms and other alternative treatment strategies when

antidepressant mono-therapy is considered inadequate.[200]

For treatment-resistant depression, adding on the atypical antipsychotic brexpiprazole for short-term or acute management may be considered.[201]

Brexpiprazole may be effective for some people, however, the evidence as of 2023 supporting its use is weak and this medication has potential adverse

effects including weight gain and akathisia.[201] Brexpiprazole has not been sufficiently studied in older people or children and the use and effectiveness

of this adjunctive therapy for longer term management is not clear.[201]

Ketamine may have a rapid antidepressant effect lasting less than two weeks; there is limited evidence of any effect after that, common acute side

effects, and longer-term studies of safety and adverse effects are needed.[202][203] A nasal spray form of esketamine was approved by the FDA in March

2019 for use in treatment-resistant depression when combined with an oral antidepressant; risk of substance use disorder and concerns about its safety,

serious adverse effects, tolerability, effect on suicidality, lack of information about dosage, whether the studies on it adequately represent broad

populations, and escalating use of the product have been raised by an international panel of experts.[204][205]

There is insufficient high quality evidence to suggest omega-3 fatty acids are effective in depression.[206] There is limited evidence that vitamin D

supplementation is of value in alleviating the symptoms of depression in individuals who are vitamin D-deficient.[95] Lithium appears effective at lowering

the risk of suicide in those with bipolar disorder and unipolar depression to nearly the same levels as the general population.[207] There is a narrow range

of effective and safe dosages of lithium thus close monitoring may be needed.[208] Low-dose thyroid hormone may be added to existing antidepressants

to treat persistent depression symptoms in people who have tried multiple courses of medication.[209] Limited evidence suggests stimulants, such as

amphetamine and modafinil, may be effective in the short term, or as adjuvant therapy.[210][211] Also, it is suggested that folate supplements may have a

role in depression management.[212] There is tentative evidence for benefit from testosterone in males.[213]

Electroconvulsive therapy

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a standard psychiatric treatment in which seizures are electrically induced in a person with depression to provide

relief from psychiatric illnesses.[214]: 1880 ECT is used with informed consent[215] as a last line of intervention for major depressive disorder.[216] A round of

ECT is effective for about 50% of people with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder, whether it is unipolar or bipolar.[217] Follow-up treatment is

still poorly studied, but about half of people who respond relapse within twelve months.[218] Aside from effects in the brain, the general physical risks of

ECT are similar to those of brief general anesthesia.[219]: 259 Immediately following treatment, the most common adverse effects are confusion and

memory loss.[216][220] ECT is considered one of the least harmful treatment options available for severely depressed pregnant women.[221]

A usual course of ECT involves multiple administrations, typically given two or three times per week, until the person no longer has symptoms. ECT is

administered under anesthesia with a muscle relaxant.[222] Electroconvulsive therapy can differ in its application in three ways: electrode placement,

frequency of treatments, and the electrical waveform of the stimulus. These three forms of application have significant differences in both adverse side

effects and symptom remission. After treatment, drug therapy is usually continued, and some people receive maintenance ECT.[216]

ECT appears to work in the short term via an anticonvulsant effect mostly in the frontal lobes, and longer term via neurotrophic effects primarily in the

medial temporal lobe.[223]

Other

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) or deep transcranial magnetic stimulation is a noninvasive method used to stimulate small regions of the

brain.[224] TMS was approved by the FDA for treatment-resistant major depressive disorder (trMDD) in 2008[225] and as of 2014 evidence supports that it

is probably effective.[226] The American Psychiatric Association,[227] the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Disorders,[228] and the Royal Australia

and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists have endorsed TMS for trMDD.[229] Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is another noninvasive

method used to stimulate small regions of the brain with a weak electric current. Several meta-analyses have concluded that active tDCS was useful for

treating depression.[230][231]

There is a small amount of evidence that sleep deprivation may improve depressive symptoms in some individuals,[232] with the effects usually showing

up within a day. This effect is usually temporary. Besides sleepiness, this method can cause a side effect of mania or hypomania.[233] There is insufficient

evidence for Reiki[234] and dance movement therapy in depression.[235] Cannabis is specifically not recommended as a treatment.[236]

Prognosis

Studies have shown that 80% of those with a first major depressive episode will have at least one more during their life,[237] with a lifetime average of

four episodes.[238] Other general population studies indicate that around half those who have an episode recover (whether treated or not) and remain

well, while the other half will have at least one more, and around 15% of those experience chronic recurrence.[239] Studies recruiting from selective

inpatient sources suggest lower recovery and higher chronicity, while studies of mostly outpatients show that nearly all recover, with a median episode

duration of 11 months. Around 90% of those with severe or psychotic depression, most of whom also meet criteria for other mental disorders, experience

recurrence.[240][241] Cases when outcome is poor are associated with inappropriate treatment, severe initial symptoms including psychosis, early age of

onset, previous episodes, incomplete recovery after one year of treatment, pre-existing severe mental or medical disorder, and family dysfunction.[242]

A high proportion of people who experience full symptomatic remission still have at least one not fully resolved symptom after treatment.[243] Recurrence

or chronicity is more likely if symptoms have not fully resolved with treatment.[243] Current guidelines recommend continuing antidepressants for four to

six months after remission to prevent relapse. Evidence from many randomized controlled trials indicates continuing antidepressant medications after

recovery can reduce the chance of relapse by 70% (41% on placebo vs. 18% on antidepressant). The preventive effect probably lasts for at least the first

36 months of use.[244]

Major depressive episodes often resolve over time, whether or not they are treated. Outpatients on a waiting list show a 10–15% reduction in symptoms

within a few months, with approximately 20% no longer meeting the full criteria for a depressive disorder.[245] The median duration of an episode has

been estimated to be 23 weeks, with the highest rate of recovery in the first three months.[246] According to a 2013 review, 23% of untreated adults with

mild to moderate depression will remit within 3 months, 32% within 6 months and 53% within 12 months.[247]

Ability to work

Depression may affect people's ability to work. The combination of usual clinical care and support with return to work (like working less hours or changing

tasks) probably reduces sick leave by 15%, and leads to fewer depressive symptoms and improved work capacity, reducing sick leave by an annual

average of 25 days per year.[154] Helping depressed people return to work without a connection to clinical care has not been shown to have an effect on

sick leave days. Additional psychological interventions (such as online cognitive behavioral therapy) lead to fewer sick days compared to standard

management only. Streamlining care or adding specific providers for depression care may help to reduce sick leave.[154]

Life expectancy and the risk of suicide

Depressed individuals have a shorter life expectancy than those without depression, in part because people who are depressed are at risk of dying of

suicide.[248] About 50% of people who die of suicide have a mood disorder such as major depression, and the risk is especially high if a person has a

marked sense of hopelessness or has both depression and borderline personality disorder.[249][250] About 2–8% of adults with major depression die by

suicide.[2][251] In the US, the lifetime risk of suicide associated with a diagnosis of major depression is estimated at 7% for men and 1% for women,[252]

even though suicide attempts are more frequent in women.[253]

Depressed people have a higher rate of dying from other causes.[254] There is a 1.5- to 2-fold increased risk of cardiovascular disease, independent of

other known risk factors, and is itself linked directly or indirectly to risk factors such as smoking and obesity. People with major depression are less likely

to follow medical recommendations for treating and preventing cardiovascular disorders, further increasing their risk of medical complications.[255]

Cardiologists may not recognize underlying depression that complicates a cardiovascular problem under their care.[256]

Epidemiology

Main article: Epidemiology of depression

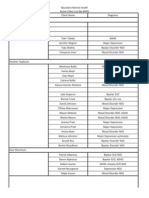

Major depressive disorder affected approximately 163 million people in 2017 (2% of the global

population).[8] The percentage of people who are affected at one point in their life varies from 7% in Japan

to 21% in France.[4] In most countries the number of people who have depression during their lives falls

within an 8–18% range.[4]

In the United States, 8.4% of adults (21 million individuals) have at least one episode within a year-long

period; the probability of having a major depressive episode is higher for females than males (10.5% to Disability-adjusted life year for unipolar

6.2%), and highest for those aged 18 to 25 (17%).[258] Among adolescents between the ages of 12 and 17, depressive disorders per 100,000

inhabitants in 2004:[257]

17% of the U.S. population (4.1 million individuals) had a major depressive episode in 2020 (females

no data

25.2%, males 9.2%).[258] Among individuals reporting two or more races, the US prevalence is highest.[258]

<700

700–775

Major depression is about twice as common in women as in men, although it is unclear why this is so, and

775–850

whether factors unaccounted for are contributing to this.[259] The relative increase in occurrence is related to

850–925

pubertal development rather than chronological age, reaches adult ratios between the ages of 15 and 18, 925–1,000

and appears associated with psychosocial more than hormonal factors.[259] In 2019, major depressive 1,000–1,075

disorder was identified (using either the DSM-IV-TR or ICD-10) in the Global Burden of Disease Study as 1,075–1,150

the fifth most common cause of years lived with disability and the 18th most common for disability-adjusted 1,150–1,225

1,225–1,300

life years.[260]

1,300–1,375

People are most likely to develop their first depressive episode between the ages of 30 and 40, and there is 1,375–1,450

>1,450

a second, smaller peak of incidence between ages 50 and 60.[261] The risk of major depression is increased

with neurological conditions such as stroke, Parkinson's disease, or multiple sclerosis, and during the first

year after childbirth.[262] It is also more common after cardiovascular illnesses, and is related more to those with a poor cardiac disease outcome than to

a better one.[263][264] Depressive disorders are more common in urban populations than in rural ones and the prevalence is increased in groups with

poorer socioeconomic factors, e.g., homelessness.[265] Depression is common among those over 65 years of age and increases in frequency beyond

this age.[29] The risk of depression increases in relation to the frailty of the individual.[266] Depression is one of the most important factors which

negatively impact quality of life in adults, as well as the elderly.[29] Both symptoms and treatment among the elderly differ from those of the rest of the

population.[29]

Major depression was the leading cause of disease burden in North America and other high-income countries, and the fourth-leading cause worldwide as

of 2006. In the year 2030, it is predicted to be the second-leading cause of disease burden worldwide after HIV, according to the WHO.[267] Delay or

failure in seeking treatment after relapse and the failure of health professionals to provide treatment are two barriers to reducing disability.[268]

Comorbidity

Major depression frequently co-occurs with other psychiatric problems. The 1990–92 National Comorbidity Survey (US) reported that half of those with

major depression also have lifetime anxiety and its associated disorders, such as generalized anxiety disorder.[269] Anxiety symptoms can have a major

impact on the course of a depressive illness, with delayed recovery, increased risk of relapse, greater disability and increased suicidal behavior.[270]

Depressed people have increased rates of alcohol and substance use, particularly dependence,[271][272] and around a third of individuals diagnosed with

attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) develop comorbid depression.[273] Post-traumatic stress disorder and depression often co-occur.[15]

Depression may also coexist with ADHD, complicating the diagnosis and treatment of both.[274] Depression is also frequently comorbid with alcohol use

disorder and personality disorders.[275] Depression can also be exacerbated during particular months (usually winter) in those with seasonal affective

disorder. While overuse of digital media has been associated with depressive symptoms, using digital media may also improve mood in some

situations.[276][277]

Depression and pain often co-occur. One or more pain symptoms are present in 65% of people who have depression, and anywhere from 5 to 85% of

people who are experiencing pain will also have depression, depending on the setting—a lower prevalence in general practice, and higher in specialty

clinics. Depression is often underrecognized, and therefore undertreated, in patients presenting with pain.[278] Depression often coexists with physical

disorders common among the elderly, such as stroke, other cardiovascular diseases, Parkinson's disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease.[279]

History

Main article: History of depression

The Ancient Greek physician Hippocrates described a syndrome of melancholia (μελαγχολία, melankholía) as a distinct disease with particular mental

and physical symptoms; he characterized all "fears and despondencies, if they last a long time" as being symptomatic of the ailment.[280] It was a similar

but far broader concept than today's depression; prominence was given to a clustering of the symptoms of sadness, dejection, and despondency, and

often fear, anger, delusions and obsessions were included.[281]

The term depression itself was derived from the Latin verb deprimere, meaning "to press down".[282] From the

14th century, "to depress" meant to subjugate or to bring down in spirits. It was used in 1665 in English author

Richard Baker's Chronicle to refer to someone having "a great depression of spirit", and by English author

Samuel Johnson in a similar sense in 1753.[283] The term also came into use in physiology and economics. An

early usage referring to a psychiatric symptom was by French psychiatrist Louis Delasiauve in 1856, and by the

1860s it was appearing in medical dictionaries to refer to a physiological and metaphorical lowering of emotional

function.[284] Since Aristotle, melancholia had been associated with men of learning and intellectual brilliance, a

hazard of contemplation and creativity. However, by the 19th century, this association has largely shifted and

melancholia became more commonly linked with women.[281]

Although melancholia remained the dominant diagnostic term, depression gained increasing currency in medical

treatises and was a synonym by the end of the century; German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin may have been the

first to use it as the overarching term, referring to different kinds of melancholia as depressive states.[285] Freud

likened the state of melancholia to mourning in his 1917 paper Mourning and Melancholia. He theorized that

Diagnoses of depression go back at objective loss, such as the loss of a valued relationship through death or a romantic break-up, results in

least as far as Hippocrates. subjective loss as well; the depressed individual has identified with the object of affection through an

unconscious, narcissistic process called the libidinal cathexis of the ego. Such loss results in severe melancholic

symptoms more profound than mourning; not only is the outside world viewed negatively but the ego itself is compromised.[286] The person's decline of

self-perception is revealed in his belief of his own blame, inferiority, and unworthiness.[287] He also emphasized early life experiences as a predisposing

factor.[281] Adolf Meyer put forward a mixed social and biological framework emphasizing reactions in the context of an individual's life, and argued that

the term depression should be used instead of melancholia.[288] The first version of the DSM (DSM-I, 1952) contained depressive reaction and the DSM-

II (1968) depressive neurosis, defined as an excessive reaction to internal conflict or an identifiable event, and also included a depressive type of manic-

depressive psychosis within Major affective disorders.[289]

The term unipolar (along with the related term bipolar) was coined by the neurologist and psychiatrist Karl Kleist, and subsequently used by his disciples

Edda Neele and Karl Leonhard.[290]

The term Major depressive disorder was introduced by a group of US clinicians in the mid-1970s as part of proposals for diagnostic criteria based on

patterns of symptoms (called the "Research Diagnostic Criteria", building on earlier Feighner Criteria),[10] and was incorporated into the DSM-III in

1980.[291] The American Psychiatric Association added "major depressive disorder" to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-

III),[292] as a split of the previous depressive neurosis in the DSM-II, which also encompassed the conditions now known as dysthymia and adjustment

disorder with depressed mood.[292] To maintain consistency the ICD-10 used the same criteria, with only minor alterations, but using the DSM diagnostic

threshold to mark a mild depressive episode, adding higher threshold categories for moderate and severe episodes.[103][291] The ancient idea of

melancholia still survives in the notion of a melancholic subtype.

The new definitions of depression were widely accepted, albeit with some conflicting findings and views. There have been some continued empirically

based arguments for a return to the diagnosis of melancholia.[293][294] There has been some criticism of the expansion of coverage of the diagnosis,

related to the development and promotion of antidepressants and the biological model since the late 1950s.[295]

Society and culture

Further information: Depression and culture

Terminology

The term "depression" is used in a number of different ways. It is often used to mean this syndrome but may

refer to other mood disorders or simply to a low mood. People's conceptualizations of depression vary widely,

both within and among cultures. "Because of the lack of scientific certainty," one commentator has observed,

"the debate over depression turns on questions of language. What we call it—'disease,' 'disorder,' 'state of

mind'—affects how we view, diagnose, and treat it."[297] There are cultural differences in the extent to which

serious depression is considered an illness requiring personal professional treatment, or an indicator of

something else, such as the need to address social or moral problems, the result of biological imbalances, or a

reflection of individual differences in the understanding of distress that may reinforce feelings of powerlessness,

and emotional struggle.[298][299]

Stigma

Historical figures were often reluctant to discuss or seek treatment for depression due to social stigma about the

condition, or due to ignorance of diagnosis or treatments. Nevertheless, analysis or interpretation of letters,

journals, artwork, writings, or statements of family and friends of some historical personalities has led to the

presumption that they may have had some form of depression. People who may have had depression include

English author Mary Shelley,[300] American-British writer Henry James,[301] and American president Abraham The 16th American president,

Lincoln.[302] Some well-known contemporary people with possible depression include Canadian songwriter Abraham Lincoln, had "melancholy", a

Leonard Cohen[303] and American playwright and novelist Tennessee Williams.[304] Some pioneering condition that now may be referred to

as clinical depression.[296]

psychologists, such as Americans William James[305][306] and John B. Watson,[307] dealt with their own

depression.

There has been a continuing discussion of whether neurological disorders and mood disorders may be linked to creativity, a discussion that goes back to

Aristotelian times.[308][309] British literature gives many examples of reflections on depression.[310] English philosopher John Stuart Mill experienced a

several-months-long period of what he called "a dull state of nerves", when one is "unsusceptible to enjoyment or pleasurable excitement; one of those

moods when what is pleasure at other times, becomes insipid or indifferent". He quoted English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge's "Dejection" as a perfect

description of his case: "A grief without a pang, void, dark and drear, / A drowsy, stifled, unimpassioned grief, / Which finds no natural outlet or relief / In

word, or sigh, or tear."[311][312] English writer Samuel Johnson used the term "the black dog" in the 1780s to describe his own depression,[313] and it was

subsequently popularized by British Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill, who also had the disorder.[313] Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in his Faust, Part

I, published in 1808, has Mephistopheles assume the form of a black dog, specifically a poodle.

Social stigma of major depression is widespread, and contact with mental health services reduces this only slightly. Public

opinions on treatment differ markedly to those of health professionals; alternative treatments are held to be more helpful

than pharmacological ones, which are viewed poorly.[314] In the UK, the Royal College of Psychiatrists and the Royal

College of General Practitioners conducted a joint Five-year Defeat Depression campaign to educate and reduce stigma

from 1992 to 1996;[315] a MORI study conducted afterwards showed a small positive change in public attitudes to

depression and treatment.[316]

While serving his first term as Prime Minister of Norway, Kjell Magne Bondevik attracted international attention in August

1998 when he announced that he was suffering from a depressive episode, becoming the highest ranking world leader to

admit to suffering from a mental illness while in office. Upon this revelation, Anne Enger became acting Prime Minister for

three weeks, from 30 August to 23 September, while he recovered from the depressive episode. Bondevik then returned to

office. Bondevik received thousands of supportive letters, and said that the experience had been positive overall, both for In 1998, the

Norwegian PM Kjell

himself and because it made mental illness more publicly acceptable.[317][318]

Magne Bondevik publicly

announced he will take a

References break in order to recover

from a depressive

1. ^ a b c d e f g h i "Depression" . U.S. National Institute of 164. ^ de Maat S, Dekker J, Schoevers R, et al. (2007). "Short episode.

Mental Health (NIMH). May 2016. Archived from the psychodynamic supportive psychotherapy, antidepressants,

original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016. and their combination in the treatment of major depression:

2. ^ a b Richards CS, O'Hara MW (2014). The Oxford a mega-analysis based on three randomized clinical

Handbook of Depression and Comorbidity . Oxford trials" . Depression and Anxiety. 25 (7): 565–74.

University Press. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-19-979704-2. doi:10.1002/da.20305 . PMID 17557313 .

3. ^ a b American Psychiatric Association 2013, p. 165. S2CID 20373635 .

4. ^ a b c d e f g Kessler RC, Bromet EJ (2013). "The 165. ^ Iglesias-González M, Aznar-Lou I, Gil-Girbau M, et al.

epidemiology of depression across cultures" . Annual (November 2017). "Comparing watchful waiting with

Review of Public Health. 34: 119–38. doi:10.1146/annurev- antidepressants for the management of subclinical

publhealth-031912-114409 . PMC 4100461 . depression symptoms to mild-moderate depression in

PMID 23514317 . primary care: a systematic review" . Family Practice. 34

5. ^ a b c d e f g American Psychiatric Association 2013, p. 166. (6): 639–48. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmx054 .

6. ^ American Psychiatric Association 2013, pp. 167–168. PMID 28985309 .

7. ^ a b Cooney GM, Dwan K, Greig CA, Lawlor DA, Rimer J, 166. ^ "The treatment and management of depression in

Waugh FR, McMurdo M, Mead GE (September 2013). Mead adults" . NICE. October 2009. Archived from the original

GE (ed.). "Exercise for depression" . The Cochrane on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013 (9): CD004366. 167. ^ Leucht C, Huhn M, Leucht S (December 2012). Leucht C

doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub6 . PMC 9721454 . (ed.). "Amitriptyline versus placebo for major depressive

PMID 24026850 . disorder". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

8. ^ a b c GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and 12: CD009138. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009138.pub2 .

Prevalence Collaborators (10 November 2018). "Global, PMID 23235671 .

regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived 168. ^ de Vries YA, Roest AM, Bos EH, et al. (January 2019).

with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries "Predicting antidepressant response by monitoring early

and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the improvement of individual symptoms of depression:

Global Burden of Disease Study 2017" . Lancet. 392 individual patient data meta-analysis" . The British Journal

(10159): 1789–1858. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279- of Psychiatry. 214 (1): 4–10. doi:10.1192/bjp.2018.122 .

7 . PMC 6227754 . PMID 30496104 . PMC 7557872 . PMID 29952277 .

9. ^ Sartorius N, Henderson AS, Strotzka H, et al. "The ICD-10 169. ^ Thase ME (December 2006). "Preventing relapse and

Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Clinical recurrence of depression: a brief review of therapeutic

descriptions and diagnostic guidelines" (PDF). World options". CNS Spectrums. 11 (12 Suppl 15): 12–21.

Health Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on doi:10.1017/S1092852900015212 . PMID 17146414 .

5 February 2022. Retrieved 23 June 2021. S2CID 2347144 .

10. ^ a b Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E (1975). "The 170. ^ a b Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain 2008,

development of diagnostic criteria in psychiatry" (PDF). p. 204

Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 December 2005. 171. ^ Whooley MA, Simon GE (December 2000). "Managing

Retrieved 8 November 2008. depression in medical outpatients". The New England

11. ^ a b Patton LL (2015). The ADA Practical Guide to Patients Journal of Medicine. 343 (26): 1942–50.

with Medical Conditions (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1056/NEJM200012283432607 . PMID 11136266 .

p. 339. ISBN 978-1-118-92928-5. 172. ^ Zisook S, Rush AJ, Haight BR, Clines DC, Rockett CB

12. ^ Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Dimidjian S, (February 2006). "Use of bupropion in combination with

Amsterdam JD, Shelton RC, Fawcett J (January 2010). serotonin reuptake inhibitors". Biological Psychiatry. 59 (3):

"Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a 203–10. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.027 .

patient-level meta-analysis" . JAMA. 303 (1): 47–53. PMID 16165100 . S2CID 20997303 .

doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1943 . PMC 3712503 . 173. ^ Papakostas GI, Thase ME, Fava M, Nelson JC, Shelton

PMID 20051569 . RC (December 2007). "Are antidepressant drugs that

13. ^ Kirsch I, Deacon BJ, Huedo-Medina TB, Scoboria A, combine serotonergic and noradrenergic mechanisms of

Moore TJ, Johnson BT (February 2008). "Initial severity and action more effective than the selective serotonin reuptake

antidepressant benefits: a meta-analysis of data submitted inhibitors in treating major depressive disorder? A meta-

to the Food and Drug Administration" . PLOS Medicine. 5 analysis of studies of newer agents". Biological Psychiatry.

(2): e45. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050045 . 62 (11): 1217–27. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.027 .

PMC 2253608 . PMID 18303940 . PMID 17588546 . S2CID 45621773 .

14. ^ Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators 174. ^ Duff G (31 May 2006). "Updated prescribing advice for

(August 2015). "Global, regional, and national incidence, venlafaxine (Efexor/Efexor XL)" . Medicines and

prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). Archived

chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: from the original on 13 November 2008.

a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease 175. ^ "Antidepressants for children and teenagers: what works

Study 2013" . Lancet. 386 (9995): 743–800. for anxiety and depression?" . NIHR Evidence (Plain

doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4 . PMC 4561509 . English summary). National Institute for Health and Care

PMID 26063472 . Research. 3 November 2022.

15. ^ a b c d e Depression (PDF). National Institute of Mental doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_53342 . S2CID 253347210 .

Health (NIMH). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 176. ^ a b c Zhou X, Teng T, Zhang Y, Del Giovane C, Furukawa

August 2021. Retrieved 13 October 2021. TA, Weisz JR, et al. (July 2020). "Comparative efficacy and

16. ^ American Psychiatric Association 2013, p. 160. acceptability of antidepressants, psychotherapies, and their

17. ^ American_Psychiatric_Association 2013, p. 161. combination for acute treatment of children and adolescents

with depressive disorder: a systematic review and network

18. ^ Everaert J, Vrijsen JN, Martin-Willett R, van de Kraats L,

meta-analysis" . The Lancet. Psychiatry. 7 (7): 581–601.

Joormann J (2022). "A meta-analytic review of the

relationship between explicit memory bias and depression: doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30137-1 . PMC 7303954 .

PMID 32563306 .

Depression features an explicit memory bias that persists

beyond a depressive episode" . Psychological Bulletin. 177. ^ a b Hetrick SE, McKenzie JE, Bailey AP, Sharma V, Moller

148 (5–6): 435–463. doi:10.1037/bul0000367 . ISSN 1939- CI, Badcock PB, et al. (Cochrane Common Mental

1455 . S2CID 253306482 . Disorders Group) (May 2021). "New generation

antidepressants for depression in children and adolescents:

19. ^ a b c American Psychiatric Association 2013, p. 163.

a network meta-analysis" . The Cochrane Database of

20. ^ Murray G (September 2007). "Diurnal mood variation in

Systematic Reviews. 2021 (5): CD013674.

depression: a signal of disturbed circadian function?".

doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013674.pub2 . PMC 8143444 .

Journal of Affective Disorders. 102 (1–3): 47–53.

PMID 34029378 .

doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.12.001 . PMID 17239958 .

178. ^ Solmi M, Fornaro M, Ostinelli EG, Zangani C, Croatto G,

21. ^ "Insomnia: Assessment and Management in Primary

Monaco F, et al. (June 2020). "Safety of 80 antidepressants,

Care" . American Family Physician. 59 (11): 3029–3038.

antipsychotics, anti-attention-deficit/hyperactivity

1999. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011.

medications and mood stabilizers in children and

Retrieved 12 November 2014.

adolescents with psychiatric disorders: a large scale

22. ^ American Psychiatric Association 2000a, p. 412

systematic meta-review of 78 adverse effects" . World

23. ^ Nelson JC, Bickford D, Delucchi K, Fiedorowicz JG,

Psychiatry. 19 (2): 214–232. doi:10.1002/wps.20765 .

Coryell WH (September 2018). "Risk of Psychosis in

PMC 7215080 . PMID 32394557 .

Recurrent Episodes of Psychotic and Nonpsychotic Major

179. ^ Boaden K, Tomlinson A, Cortese S, Cipriani A (2

Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-

September 2020). "Antidepressants in Children and

Analysis" . The American Journal of Psychiatry. 175 (9):

Adolescents: Meta-Review of Efficacy, Tolerability and

897–904. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17101138 .

Suicidality in Acute Treatment" . Frontiers in Psychiatry. 11:

PMID 29792050 . S2CID 43951278 .

717. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00717 . PMC 7493620 .

24. ^ Fisher JC, Powers WE, Tuerk DB, Edgerton MT (March

PMID 32982805 .

1975). "Development of a plastic surgical teaching service in

180. ^ Correll CU, Cortese S, Croatto G, Monaco F, Krinitski D,

a women's correctional institution" . American Journal of

Arrondo G, et al. (June 2021). "Efficacy and acceptability of

Surgery. 129 (3): 269–72. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7284.482 .

pharmacological, psychosocial, and brain stimulation

PMC 1119689 . PMID 11222428 .

interventions in children and adolescents with mental

25. ^ a b c American Psychiatric Association 2000a, p. 349

disorders: an umbrella review" . World Psychiatry. 20 (2):

26. ^ Delgado PL, Schillerstrom J (2009). "Cognitive Difficulties

244–275. doi:10.1002/wps.20881 . PMC 8129843 .

Associated With Depression: What Are the Implications for

PMID 34002501 .

Treatment?" . Psychiatric Times. 26 (3). Archived from

181. ^ "Depression in children and young people: Identification

the original on 22 July 2009.

and management in primary, community and secondary

27. ^ Faculty of Psychiatry of Old Age, NSW Branch, RANZCP,

care" . NICE Clinical Guidelines. NHS National Institute for

Kitching D, Raphael B (2001). Consensus Guidelines for

Health and Clinical Excellence (28). 2005. Archived from the

Assessment and Management of Depression in the

original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 12 November

Elderly (PDF). North Sydney, New South Wales: NSW

2014.

Health Department. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-7347-3341-2.

182. ^ "Prozac may be the best treatment for young people with

Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 April 2015.

depression – but more research is needed" . NIHR

28. ^ American Psychiatric Association 2013, p. 164.

Evidence (Plain English summary). National Institute for

29. ^ abcde Swedish Agency for Health Technology

Health and Care Research. 12 October 2020.

Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (SBU) (27

doi:10.3310/alert_41917 . S2CID 242952585 .

January 2015). "Depression treatment for the elderly" .

183. ^ Boaden K, Tomlinson A, Cortese S, Cipriani A (2

sbu.se. Archived from the original on 18 June 2016.

September 2020). "Antidepressants in Children and

Retrieved 16 June 2016.

Adolescents: Meta-Review of Efficacy, Tolerability and

30. ^ Hankin BL, Abela JR (2005). Development of

Suicidality in Acute Treatment" . Frontiers in Psychiatry. 11:

Psychopathology: A Vulnerability-Stress Perspective .

717. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00717 . PMC 7493620 .

SAGE Publications. pp. 32–34. ISBN 9781412904902.

PMID 32982805 .

31. ^ Otte C, Gold SM, Penninx BW, Pariante CM, Etkin A, Fava

184. ^ Cipriani A, Zhou X, Del Giovane C, Hetrick SE, Qin B,

M, et al. (September 2016). "Major depressive disorder"

Whittington C, et al. (August 2016). "Comparative efficacy

(PDF). Nature Reviews. Disease Primers. Springer Nature

and tolerability of antidepressants for major depressive

(published 15 September 2016). 2 (1): 16065.

disorder in children and adolescents: a network meta-

doi:10.1038/nrdp.2016.65 . PMID 27629598 .

analysis" . Lancet. 388 (10047): 881–890.