Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Insert

Insert

Uploaded by

Ahmad Shafiq ZiaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Insert

Insert

Uploaded by

Ahmad Shafiq ZiaCopyright:

Available Formats

Passage 2

This passage is about how a young mother reacts to her baby’s illness.

1 The warm summer wore away, and a cold autumn set in, with rain, damp and an unseasonal

frost at night. When I put gloves on the baby she chewed them and had to sit in her pram

with cold, wet hands. I did not mind for myself, but I did not know how to keep her warm.

She dribbled too and her chest was always damp. She resisted for some time but in the end

she caught a cold. 5

2 I did not know what to do with her, as I hated going to the doctor. I had expected I would be

finished with doctors once she was born, though I subsequently discovered there was an

unending succession of health checks and vaccinations yet to be endured. Now, hearing

Octavia’s heavy spluttering, I knew I would have to take her, much as I would hate it. I

felt I was bothering the busy doctor unnecessarily. But it was not a simple choice between 10

comfort and duty, and moreover it was not even my own health that was in question, but

Octavia’s, and so I tried to dismiss the thought of sitting in a freezing cold waiting room with

her. Had it been my own health, I would never have gone.

3 After I had made up my mind to see the doctor, I consulted my friend Lydia, who suggested

that I should ring up the doctor and ask him to come and see me at home, instead of going 15

to him; I immediately thought how nice it would be if only I dared. ‘Of course you dare,’ said

Lydia. ‘You can’t take a sick baby out in weather like this.’ Then, with sudden illumination,

she said, ‘Anyway, look how flushed she is! Why don’t you take her temperature?’

4 Astounded, I stared at her, for truly the thought of doing such a thing had never crossed my

mind. Looking back now, after months with the thermometer as necessary as a spoon or a 20

saucepan, I can hardly believe this to be possible, but so it was; my life had not yet changed

for ever. I took Octavia’s temperature and it was high enough to justify ringing for the doctor.

To my surprise, the doctor’s secretary did not sound at all annoyed when I asked if the

doctor could visit; I think I had half expected her to lecture me.

5 When the doctor arrived, he took Octavia’s pulse and temperature, and told me it was 25

nothing serious, in fact nothing at all. Then he said he ought to listen to her chest; I pulled

up her vest and she smiled and wriggled with delight as he put the stethoscope on her fat

ribs. He listened for a long time and I, who was beginning to think that perhaps I should not

have bothered him after all, sat there calmly aware of how innocent she was, how sweet

she looked and that her vest could do with a wash. Had I known, I would have enjoyed that 30

moment more, or perhaps I mean that I did enjoy that moment but have enjoyed none since.

For he said, ‘Well, I don’t think there’s anything very much to worry about there.’ But I could

see that he had not finished, and did not mean what he said. ‘Just the same,’ he added,

‘perhaps I ought to book you an appointment to take her along to the hospital.’

6 I suppose most people would have asked him what was wrong. I think that the truth was the 35

last thing I wanted to hear. When I heard his voice coming at me, saying that the hospital

appointment would probably be for the next Thursday, I was relieved a little; he could not be

expecting her to die before next Thursday. I even mustered the strength to ask what I should

do about her cold, and he said, ‘Nothing, nothing at all.’

7 When he had gone, I went back and picked Octavia up and sat her on my knee and gazed at 40

her, paralysed by fear, aware that my happy state had changed in ten minutes to undefined

anguish. I wept, and Octavia put her fingers in the tears on my cheek, as though they were

raindrops on a window pane. It seemed that, in comparison with this moment, the whole of

my former life had been a lovely summer afternoon.

You might also like

- Soal Us Bahasa Inggris Kelas 9 Dida JubaedahDocument5 pagesSoal Us Bahasa Inggris Kelas 9 Dida JubaedahAna Yuliana100% (3)

- Choose FreedomDocument24 pagesChoose FreedomAnanda Satya80% (5)

- Gender Swap in the Family (Taboo Gender Swap Medical Exam and Femdom Humiliation Erotica)From EverandGender Swap in the Family (Taboo Gender Swap Medical Exam and Femdom Humiliation Erotica)No ratings yet

- MOUNTAIN RANGES OF PAKISTAN PresentationDocument7 pagesMOUNTAIN RANGES OF PAKISTAN PresentationAhmad Shafiq Zia0% (1)

- Ce Correl Ports and Harbor (B)Document5 pagesCe Correl Ports and Harbor (B)Glenn Frey Layug0% (1)

- Read Passage About How A Young Mother Reacts To Her Baby's Illness and Answer All The Questions Below: PassageDocument5 pagesRead Passage About How A Young Mother Reacts To Her Baby's Illness and Answer All The Questions Below: PassageMuhammadd YaqoobNo ratings yet

- The Slutty Farm Cow (Part 1): BDSM Hucow Milking Lactation Menage EroticaFrom EverandThe Slutty Farm Cow (Part 1): BDSM Hucow Milking Lactation Menage EroticaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- You Don’t Take A Temperature Like That, Doc! : Anal Lovers 28 (Medical Erotica Virgin Anal Sex Erotica): Anal Lovers, #28From EverandYou Don’t Take A Temperature Like That, Doc! : Anal Lovers 28 (Medical Erotica Virgin Anal Sex Erotica): Anal Lovers, #28No ratings yet

- Three Men in A BoatDocument9 pagesThree Men in A BoatDulguun OtgNo ratings yet

- Blood TextDocument2 pagesBlood Textbambieyes1112No ratings yet

- Elemental Tears: The Eldritch Files, #8From EverandElemental Tears: The Eldritch Files, #8Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Her Milk, His Desire (Swells, Lacey) (Z-Library)Document52 pagesHer Milk, His Desire (Swells, Lacey) (Z-Library)VaninaNo ratings yet

- SherwinDocument3 pagesSherwinhellofrom theothersideNo ratings yet

- Fevers: Savage7289Document5 pagesFevers: Savage7289Shivani MalikNo ratings yet

- Accommodating the Doctor (BBW First Time Medical Exam Fertile Erotica)From EverandAccommodating the Doctor (BBW First Time Medical Exam Fertile Erotica)No ratings yet

- Amanda's Tale: A Very Personal Journey Through Suicide and BeyondFrom EverandAmanda's Tale: A Very Personal Journey Through Suicide and BeyondNo ratings yet

- Days WaitDocument2 pagesDays WaitKarim MoundirNo ratings yet

- Gender Swap at the Doctor's (Gender Swap Medical Exam and Femdom Humiliation Erotica)From EverandGender Swap at the Doctor's (Gender Swap Medical Exam and Femdom Humiliation Erotica)No ratings yet

- Cancer, Cancelled: Taking on 4th stage cancer, and coming out alive.From EverandCancer, Cancelled: Taking on 4th stage cancer, and coming out alive.No ratings yet

- Thank God I Got Cancer...I'm Not a Hypochondriac Anymore!From EverandThank God I Got Cancer...I'm Not a Hypochondriac Anymore!Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- And Then I Peed My Pants...: My Misadventures in New MotherhoodFrom EverandAnd Then I Peed My Pants...: My Misadventures in New MotherhoodNo ratings yet

- Forget Me NotDocument218 pagesForget Me NotVanessa Cruz100% (1)

- FP1 MatricesDocument3 pagesFP1 MatricesAhmad Shafiq ZiaNo ratings yet

- CamScanner 10-08-2023 18.04Document5 pagesCamScanner 10-08-2023 18.04Ahmad Shafiq ZiaNo ratings yet

- CamScanner 10-07-2023 13.16Document5 pagesCamScanner 10-07-2023 13.16Ahmad Shafiq ZiaNo ratings yet

- 1 Term Assessment July, 2020: Class:-O1 Time: - 45 Minutes Subject: - Biology Marks: - 25Document3 pages1 Term Assessment July, 2020: Class:-O1 Time: - 45 Minutes Subject: - Biology Marks: - 25Ahmad Shafiq ZiaNo ratings yet

- Physics Assignment (O2-2)Document8 pagesPhysics Assignment (O2-2)Ahmad Shafiq ZiaNo ratings yet

- Img 1450Document14 pagesImg 1450Ahmad Shafiq ZiaNo ratings yet

- 9231 Matrices and Solution of Linear EquationsDocument5 pages9231 Matrices and Solution of Linear EquationsAhmad Shafiq ZiaNo ratings yet

- Pressure Questions.Document2 pagesPressure Questions.Ahmad Shafiq ZiaNo ratings yet

- QuaidDocument15 pagesQuaidAhmad Shafiq ZiaNo ratings yet

- 3c732d PDFDocument1 page3c732d PDFAhmad Shafiq ZiaNo ratings yet

- Eigen Values and Vector Further Maths AlevelDocument8 pagesEigen Values and Vector Further Maths AlevelAhmad Shafiq ZiaNo ratings yet

- Equivalent Fractions Worksheet PDFDocument2 pagesEquivalent Fractions Worksheet PDFAhmad Shafiq ZiaNo ratings yet

- Mountain RangesDocument7 pagesMountain RangesAhmad Shafiq ZiaNo ratings yet

- Eng 506 CompleteDocument167 pagesEng 506 CompleteAhmad Shafiq Zia50% (4)

- Kestine Tablet Information and DosageDocument2 pagesKestine Tablet Information and DosageAhmad Shafiq ZiaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1: Sana Minatotaxi Cutie: Global Warming and Climate ChangeDocument13 pagesLesson 1: Sana Minatotaxi Cutie: Global Warming and Climate ChangeMicaella GuintoNo ratings yet

- G D Goenka Public School, Sector-22, Rohini Class-Ix Subject-Geography Chapter-4-ClimateDocument8 pagesG D Goenka Public School, Sector-22, Rohini Class-Ix Subject-Geography Chapter-4-Climatevikas aggarwalNo ratings yet

- Actividad Modulo 5 InglesDocument6 pagesActividad Modulo 5 InglesOliver Alvarez MariñezNo ratings yet

- Weather DisturbancesDocument5 pagesWeather DisturbancescyriaaNo ratings yet

- Basic Concept of Disaster and Disaster Risk Activity 1Document1 pageBasic Concept of Disaster and Disaster Risk Activity 1anon_145781083No ratings yet

- V965F and V966FDocument2 pagesV965F and V966FZeckNo ratings yet

- Utilization of Artificial Rain Gauge For Hydro Meteorological Study (Field Report)Document11 pagesUtilization of Artificial Rain Gauge For Hydro Meteorological Study (Field Report)Yustinus AdityawanNo ratings yet

- Greenwood - Updatess - 2020-10-23-04-22-Am09 - Class-10 NOTES First Flight + PoemDocument160 pagesGreenwood - Updatess - 2020-10-23-04-22-Am09 - Class-10 NOTES First Flight + PoemPritam Jyoti biswalNo ratings yet

- Project 2a Group Ari 2 Compressed Compressed Compressed 1 - Min-CompressedDocument115 pagesProject 2a Group Ari 2 Compressed Compressed Compressed 1 - Min-Compressedapi-678752329No ratings yet

- Big Check.: Tense FormDocument3 pagesBig Check.: Tense FormThùy DươngNo ratings yet

- Water Cycle Quiz Year 7Document5 pagesWater Cycle Quiz Year 7FennyNo ratings yet

- FASID Table MET 1BDocument9 pagesFASID Table MET 1Bdenys galvanNo ratings yet

- QCVN 02-2009-BXD Vietnam Building Code Natural Physical and Climatic Data For Construction (Eng)Document324 pagesQCVN 02-2009-BXD Vietnam Building Code Natural Physical and Climatic Data For Construction (Eng)lwin_oo2435100% (1)

- Crop Water Requirement (FAO)Document60 pagesCrop Water Requirement (FAO)Fairuz ZahiraNo ratings yet

- Flood Mitigation PlanningDocument14 pagesFlood Mitigation PlanningJingNo ratings yet

- Exercised AtacDocument418 pagesExercised AtacBrandon AllenNo ratings yet

- Unlicensed-A Letter To God PDFDocument11 pagesUnlicensed-A Letter To God PDFBernadette MausisaNo ratings yet

- Geography ClimatologyDocument33 pagesGeography ClimatologyChinmay JenaNo ratings yet

- SQA Theory Questions Chief MatesDocument10 pagesSQA Theory Questions Chief Matesnisha aggar0% (1)

- Body Temperature MeasurementDocument29 pagesBody Temperature MeasurementSyafira ZolaNo ratings yet

- Atmosphere Study GuideDocument2 pagesAtmosphere Study GuideKeyton OwensNo ratings yet

- Alyssa Woolcott - 63L Weather & Climate 2023 - .PDF - KamiDocument2 pagesAlyssa Woolcott - 63L Weather & Climate 2023 - .PDF - KamiAlyssa WoolcottNo ratings yet

- Meteorology Specific Objectives ActivityDocument3 pagesMeteorology Specific Objectives ActivityRhyza Labrada Balgos - CoEdNo ratings yet

- Slide DRP Amirah v1Document30 pagesSlide DRP Amirah v1Dr Nurul Amirah IsaNo ratings yet

- BS-22 Flood-FloodplainDocument18 pagesBS-22 Flood-FloodplainSmh BrintoNo ratings yet

- 2022 KwaZulu-Natal FloodsDocument6 pages2022 KwaZulu-Natal FloodsVillaErnestNo ratings yet

- Science8 Q2 Module5 TrackingATyphoon V4-1Document24 pagesScience8 Q2 Module5 TrackingATyphoon V4-1Nathan Masilungan100% (7)

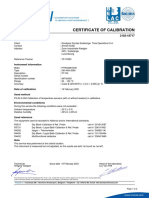

- Certificate of Calibration: Customer InformationDocument2 pagesCertificate of Calibration: Customer InformationSazzath HossainNo ratings yet