Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Curtis CaseIdentity 1996

Uploaded by

guo.rian2205Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Curtis CaseIdentity 1996

Uploaded by

guo.rian2205Copyright:

Available Formats

A Case of Identity

Author(s): Liane Curtis

Source: The Musical Times , May, 1996, Vol. 137, No. 1839 (May, 1996), pp. 15-21

Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd.

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1003935

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Musical Times Publications Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to The Musical Times

This content downloaded from

123.20.234.109 on Thu, 29 Feb 2024 20:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

A case of identity

Artur Rubinstein called her 'the glorious Rebecca Clarke'.

LIANE CURTIS argues the cause of a composer neglected

by the British and American musical establishment.

Suite for Viola as the winner. The viola sonata, elo-

Liane Curtis

teaches at

quent testimony to Clarke's power as a composer, Bowdoin

the early decades of this century, it is only

recently that Rebecca Clarke (1886-1979) speaks with directness and authority. In College,

the Maine,

USA. She is

has emerged as a prominent British com- Coolidge competition of 1921, Clarke was again

currently writing

poser. A steady stream of recordings (including eight runner-up with her Trio for violin, cello anda piano.

book on

of one work alone, the viola sonata of 1919), the re- Finally Mrs Coolidge awarded her a $1000 commis-

Rebecca Clarke.

publication of her powerful Piano Trio of 1921 and sion for the 1923 festival, resulting in her lengthy

two collections of songs,' and the recently published Rhapsody for cello and piano. In all of Mrs

New Grove dictionary of women composers, (valuable Coolidge's years as a patron of music, this was her1. Boosey &

Hawkes obtained

for the near-complete list of her works, a thorough one instance of supporting a woman. Clarke's suc-

the rights to

bibliography, and an informative article by Stephen cess in the Coolidge festivals came amidst an exten-Clarke's music

Banfield which draws largely on materials previous- sive period of giving concerts (including a touroriginally published

ly published in diverse and obscure places)2 have all around the world in 1922 and 1923) and compos- by Winthrop

assisted in making available an important part of her ing. The Viola Sonata was one of her first publica-Rogers Ltd. The

previously inaccessible output. Yet despite this tions, in 1921, along with some songs, and these reprintings, with an

growing swirl of interest, Clarke remains an enig- were followed by some shorter instrumental works.introduction by

Calum MacDonald,

matic figure: not only does a large part of her output In 1924, Clarke returned to England, and settled. include the Piano

remain unpublished, accessible only with permis- While her career as a composer was by no means Trio (originally

sion of her heirs, but what we know about Clarke over, the brief highpoint had past. published in 1928);

herself is sketchy. Although a few stories, like that of Almost 60 years later, Clarke recalled the 1919 a song album for

the Viola Sonata are well known, there has as yet Coolidge Festival in an interview with Robert Sher- medium high voice

man (of New York's WQXR Radio) conducted in and piano, contain-

been little inquiry into the details of her life: my own

ing nine works

research (although still in its early stages), reveals honour of her 90th birthday, in August 1976.

(originally pub-

her as a fascinating composer, an influential per- lished in the

And when I had that one little whiff of success that

former, and a warm but complicated personality. 1920s); and Three

Rebecca Clarke's story, one to inspire us with its I've had in my life, with the Viola Sonata, the ru- Old English songs

mour went around, I hear, that I hadn't written the arranged for voice

heroic achievement, is notable for a number of firsts.

stuff myself, that somebody had done it for me. And and violin (first

From 1907 to 1910 she studied composition in Lon-

I even got one or two little bits of... press clippings published in 1925).

don at the Royal College of Music. While women

saying that it was impossible, that I couldn't have 2. The New Grove

had been admitted as students from the college's in-

written it myself. And the funniest of all was that I

ception, it was rare for them to specialise in compo- dictionary of women

had a clipping once which said that I didn't exist, composers, edited by

sition, and Clarke was the first woman to study with

there wasn't any such person as Rebecca Clarke, that Julie Anne Sadie

Stanford. Her musical education ended when she

it was a pseudonym... for Ernest Bloch! Now these and Rhian Samuel

quarrelled with her father, who threw her out of the

people have got it most beautifully mixed - I (London, 1994;

house, forcing her to earn her own way as a violist.

thought to myself what a funny idea that when he New York, 1995)

She again made history when, in 1912, as one of 'six reinstates Clarke

writes his very much lesser works that he should

lady musicians chosen by Sir Henry J. Wood to aug-take a pseudonym of a girl, that anyone should con- after an unpardon-

able omission from

ment the Queen's Hall Orchestra', she became one sider

of this possible!4

the New Grove

the first women to play professionally in an orches-

dictionary of 1980

tra.3 Before World War 1, she was also a member of this is an amusing anecdote, it also reveals (Clarke was

While

a successful all-female string quartet, headed bysome

vio-important aspects of Clarke's self-image. She included in earlier

linist Nora Clench, and in the late-1920s, of theresponds

En- to allegations that she didn't exist, not with Groves). Clarke's

glish Ensemble, a female piano quartet. anger or contempt, but rather with good humour, works list was

During the highpoint of her career, her viola

and even turns this humour into a vehicle for de- previously pub-

lished in an article

sonata tied for first place in the 1919 competition

meaning her own creation, incredulous that some-

by Michael Ponder

sponsored by Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge as part

oneof

would confuse her 'very much lesser work' inwith

the British Music

her Berkshire Festival of Chamber music. Mrs that of the great Bloch. This stereotypically feminine

Society Journal no.5

type of modesty can also be seen as an indicator

Coolidge herself broke the tie, naming Ernest Bloch's of pp.82-88.

(1983),

THE MUSICAL TIMES / MAY 1996 15

This content downloaded from

123.20.234.109 on Thu, 29 Feb 2024 20:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Both versions of the Rebecca Clarke c.1917-18

the fragility of her own belief in her creative powers,

works list are

and of her right to employ those powers. And in-

apparently based on

deed, in what may be viewed as a case-study of

an unpublished cat-

women's low self-esteem,5 many of the achievements

alogue compiled in

1977 by Christo- that I have mentioned were spoken of by Clarke in

pher Johnson (of deprecatory ways. Clarke attributes her success to

New York City) in luck and accident, while failure or negative response

conjunction with is what she felt she deserved. This conflicted identi-

Clarke. most of

ty, of Clarke's desire to compose and her difficulty in

Clarke's manu-

believing in herself as a composer, tells us much, I

scripts are in the

private possession think, about the shape of her career and the pattern

of heirs in New of her musical output.

York City. No Given the impressive quality of Clarke's music,

manuscripts are how then are we to understand her obscurity? The

owned by the New answer to this question is obviously a complex one.

York Public Library,

Marcia Citron's recent pathbreaking book, Gender

and the Library of

Congress (Washing-

and the musical canon (Cambridge University Press,

ton DC) owns only 1993), addresses many of the relevant issues, and in

those manuscripts my forthcoming book, I shall discuss some of the

associated with forces that were obstacles and discouragements to

Elizabeth Sprague Clarke - patriarchal structures of educational sys-

Coolidge: Viola tems and family organisation, and biased attitudes of

Sonata, Piano Trio

critics and patrons.6 Here I wish to focus specifically

and Rhapsody). The

Library of Congress on her concept of self: how she internalised the val-

owns a copy of ues presented by these outside influences; how ob-

Clarke's Prelude, stacles or events influenced her own attitude about

allegro and pastorale her place in the world.

of 1941 but it is not

in Clarke's hand.

3. Arthur Jacobs: M UCH OFful what it uptakes

composer is bound in the abilityto be a success-

Henry J. Wood: to sensitively read one's surroundings was doomed to another session with the... steel

maker of the Proms and to respond to them inventively,7 a slapper, while Mama waited helplessly outside the

(London, 1994),

negotiation with the public sphere that, as a com- door and cried.8

p.142.

poser, Clarke shrank from. Her readiness to mini-

4. I would like to malise her own achievement - the opposite of self- Growing up in a household where the act of nail

thank Mr Sherman promotion, conceding to a view of society that ren- biting brought a brutal beating, we can understan

for generously shar- dered women culturally invisible - meant that that Clarke would learn to hesitate at any form o

ing the tapes of Clarke's fame in her own lifetime was shortlived. going against the grain - as defined by her father, o

these interviews

Clues to the origins of her chronic self-effacing later, mod- by the norms of conventional society. Thu

with me, both the

material that was

esty can be found in the amazing memoir throughout that Clarke's life we find a conflict - she con

used in the broad- Clarke wrote while in her 80s, a coming-of-age structed

doc- her identity as a woman in a mainstream

cast and the leftover ument reflecting on the authoritarian power struc- way, internalising the widely held views of the lim

portions. tures within her family in the Victorian era. Even tations

at of women's role and capabilities, rather tha

this late stage in her life she is still trying to effect battling

a against them. So this identity, then, was a

5. For instance, odds with her sense of self as a composer. She onc

reconciliation with her tyrannical and cruel father,

Women and

who had dominated her childhood, and whose love said 'I always feel that each thing I do is going to b

self-esteem (New

and acceptance she had so desperately wanted the

and last thing I'm capable of doing, it always seem

York, 1984) by

Linda Tschirhart needed but never attained. sort of a little bit accidental'.9 This surprise at he

Sandford and Mary 'accidental' creativity seems a way of minimalisin

Ellen Donovan; and We were all of us whipped, sometimes really her own agency and adopting instead what she per

Peggy Orenstein in painfully. As a rule I well deserved any punishment

ceived as a more feminine passivity. While Clark

association with the I got... Bathed in tears, my drawers let down, I had

spoke often of the intense pleasure of composing

American Associa- to lean across the hated red Paisley quilt on Papa's

her desire to compose was frequently repressed be

tion of University bed while he applied the 'steel slapper' - an archi-

Women: Schoolgirls:

cause of her doubts in the appropriateness of thi

tect's two foot rule... Hans and Eric [her brothers] of

drive in a woman. And I think this led to doubt her

young women, self- course had their share, but... Eric, even when quite

esteem, and the con- own talents; a doubt that seems incredible to those

small, seemed able to shrug things off in a way I nev-

fidence gap (New

er could. And being the oldest - as well as the of us who know any of her music.

York, 1994). We might contrast Clarke with Ethel Smyth,

naughtiest - I was punished more often... For years

my nails were examined every Sunday morning by Clarke's senior by 28 years, who, as a proud suf-

Papa; I had started the habit of biting them. And if fragette, carried the banner of 'woman composer'

they were not satisfactory (and they never were) I high. While Clarke sympathised with the suffragette

16 THE MUSICAL TIMES / MAY 1996

This content downloaded from

123.20.234.109 on Thu, 29 Feb 2024 20:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

cause - she played in a number of benefit concerts text. In these two pieces she stepped outside her

6. Exploring the inti-

on its behalflo - she did not become directly in- mate voice: the life

usual feminine identity, adopting a sweeping author-

and music of Rebecca

volved herself. With no wish to struggle to forge an itative stance, a grand public voice, perhaps in order

Clarke (1886-1979),

identity, she shunned militancy and stridency. As a to be competitive or bolstered by the anonymous

in progress.

woman her self-image was shaped by Victorian no- format. Truly monumental in scope, these are her

tions of restricted spheres and Edwardian gentility only mature works to employ sonata form; the indi-

7. As Philip Brett

and decorativeness. As a composer her identity was has recently empha-

vidual movements are linked through a cyclic treat-

ment of motives. sised. See 'Musicali-

highly conflicted and, for extended periods, com-

ty, essentialism, and

pletely closeted. Yet Smyth, with her more vocal ap- In their breadth of conception and rich expan-

the closet', in

proach, has fared no better in posterity than Clarke, sive, post-romantic idiom Clarke would never write

Queering the pitch:

remembered more as a figure of curiosity and even anything else to equal them, and following Clarke'sthe new gay and

ridicule than as the inventor of modern British opera third Coolidge festival in 1923, her output slowed, lesbian musicology

(although perhaps the recent performance and and by the 1930s was intermittent, partly perhaps(New York & Lon-

recording of her opera The wreckers" will allow her because a happy accident, such as that of the don, 1994), p.19.

some much deserved recognition). Coolidge festival, never again occurred, but more

8. 'I had a Father,

Clarke, however, wanted to fit into society, thus likely because, of her decision in 1924, following the

Too (or the Mustard

valuing her femininity and conforming to an ideolo- death of her father four years earlier and because of Spoon)', unpub-

gy that applied rigid stereotypes to the identity of her devotion to her mother (who died in 1935), to lished typescript

woman. Again and again we find her minimising her settle in London. Clarke's years of travel, much of (1969-73) in

own achievement: them in the US, had offered her a certain freedomClarke's estate, p.26.

Publication of the

from conventions; a freedom that may have been re-

I loved the Royal College... It was extremely memoir is planned,

inforced by the necessity of supporting herself.

stimulating to think of all the well-known com- These years released her from her desire for socialedited by myself,

with an introduc-

posers who had passed through Stanford's hands: acceptability that, back in England and with a com-

tion by Louise De

Holst, Vaughan Williams, Bridge, Butterworth, and a

fortable inheritance, both ordered her life but grad- Salvo. De Salvo is

host of others all of whom I ultimately came to

ually eroded her drive to compose. While she saw the author of nu-

know. That I was the only woman student he had ac-

the glamourous career of a performer as acceptablemerous books, most

cepted was a source of great pride to me, though I notably Virginia

within her desired identity as an upper-middle class

know full well that I never fully deserved it. Woolf: the impact of

lady of society, being a composer - which demanded childhood sexual

Memoir, p.154

control, power, and devotion to one's own creativityabuse on her life and

In the 1976 interview, Clarke recounts how she - was not (at least as Clarke defined it to herself). work (New York,

used a pseudonym - Anthony Trent. She was giving Clarke performed intensively as a chamber musician1989), which have

a recital (see illustration on p.18) in 1918 featuringthroughout these years; but as a composer, her out-provided me with

innumerable

a number of her own works, and felt embarrassed atput declined. Although much of her music from this

insights into the late

having her name mentioned numerous times on the period remains unpublished and thus almost entire-Victorian era.

programme: 'I thought how silly to have my namely unknown, its quality is impressive.

9. 1976 interview

on the programme yet again' (I can't think of many

with Robert

male composers who would be capable of making EN SHE returned she found Eng-

Sherman.

that statement!). Although, she wanted to avoid ac- land in a period of backlash.14 The

cepting the attention the piece would bring her, the suffrage movement and the First 10. Votes for women

piece by 'Anthony Trent' actually attracted more no- World War had been a time of

(London, 1911). I

tice than the pieces under her real name - somethingprogress for women, as they won many thank Elizabeth

opportuni-

for which she had not planned. By 1976 Clarke wasties and played active roles in a wide Wood, who is But in

sphere.

ready to think that she had been treated unfairly;the mid-1920s, retrenchment and awriting a book on of

reassertion

Smyth, for this

what she thought in 1918 is more difficult to know.12 traditional roles took place, a situation reflected in

reference.

Clarke's whole involvement in the Coolidge festi-many of the reviews of an all-Clarke concert of Oc-

tober 1925.

vals was, in fact, an accident, the result of a visit in 11. The wreckers

1917 to friends vacationing in Pittsfield Mass- was given a concert

Rebecca Clarke, whose recital of compositions took performance in the

achusetts, where she became acquainted with the

place at Wigmore Hall, is, as all women composers, 1994 BBC Proms. A

great music patron, Mrs Coolidge, herself summer-

largely reflective of preceding masculine creations. recording has been

ing in Pittsfield. Clarke attended the first chamber

She has, however, real feminine personality in such released on the

music festival, held in September of 1918, and Mrs Conifer label

things as her 'Lullaby' for viola and piano, and a tru-

Coolidge personally encouraged her to enter the (51250-2), with the

ly feminine bent towards the grotesque and intricate BBC Philharmonic

1919 competition for a new work featuring the vio-

in 'Grotesque' and 'Chinese Puzzle'. Orchestra and the

la.13 The context of a competition was an unusual Western Mail, Cardiff Huddersfield Choral

one for Clarke. After leaving the Royal College, she

Society directed by

had concentrated mainly on writing short instru- How remarkable it is that our women composers are Odaline de la

mental pieces or songs, self-contained single move- so much more virile in style than some of our young Martinez.

ment works with poetic titles for herself or her men. Miss Rebecca Clarke has a strong right arm

friends to play. In contrast, the Viola Sonata and the (We speak figuratively, of course). She can lay down

1921 Piano Trio stand completely outside this con- the foundation of a big chamber work like her piano

THE MUSICAL TIMES / MAY 1996 17

This content downloaded from

123.20.234.109 on Thu, 29 Feb 2024 20:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Aeolian Hall programme 13, February 1918

lA M+,, as o!i fl~ i ........................ . . . . .

Men,, Al litito ala F hi: w eth Pmaa1 ( ed A g H r 1 NIP.t

M At~ly4JP, w Edla td t edwae-

ta' iOhtHarp. ."kad

t(' i uwilD i

t htaaah

....... . .... .. .. . yi

Xnh Fr .......... . to .'..i{.i. . ...it .itI...

aeta aa.aOa'~~

G -IFTED AR IS S JO

INUNIQEgRECITALt at att3.00 a t, wail

N............-----

ahetoRhth l.RCa'Ll.t ' e..... ......a.'

th}1#i o e, A Ye-1

M la akl'o,

wyM k eviola".n

a C, Wi;nt, ++

J'?.tI,

ithl

::++:++++++ ++i++; +ii++

,.,,R.N~i

a"dad a it u'a~-'aa

F it ARWtilii'wi t

hionlaatatatwaOn agia a a'8awiaaiial I'

... ,..+ + - , :, ...... oEB E, .... ?

it.ialga. .ttttaa ii Alapiiaiaataal Pat atit'

Phi atata tt tiurf t ,i Tit .(4aaali.i''t i

at,'ttti "alataniw

r~e~s f hr, .Both

i it Ruth .,le.:ais

(cant? aay ' .<.ai ,-

ittatattat r<,.i~t+d iaia""?Aeo it" wilt W na-l idu: a-d:,.a .:+.,-,

Cla iarkeCa Vla , iii tt S'it Gfos Pam:id1-rat11ta~kato'alv

a wtttlt a rm pal i seaataa laa

II at klatt ard atti tasplayed in aet, Chines a'o Ia tI , "a../<<:

o'iaay faa: lta hi:ltta[ a rto [o t [-aoo . Vataa. t'> a 1 h:h e]] It. Ill4 !i'taa: at.aaaadaaaaa.taal -gaita.it': tai tta}i:

? "yta " "tt

pieeh ka att

Mist fti lae,

' taiat .atat

o tsh:telta

ti{L a~ra'{

t a:ii

a'a'ata't"{;:

l and ,! aataia}'::d:iaa

ri aaata tat:}:::ii~

.t..t

a la i W g..t He n -a t

larry' "otno tonu :haida' latla ye. w att

laarO ltati aigar i h ::yg . :waa n lkewse .

'itt

? 5it:,!kteit

ilat.laa , a. a, igat

aatdtaatai'alaai . ..a ha ta .. :it

12. A brief review in trio heard last night, with all the emphasis of a Liszt tainted with sentimentality) and that women who

Vogue (15 April and carry on with the sturdiness of a John Ireland or strove to go beyond this limited sphere were unnat-

1918) first consid- Frank Bridge. ural (they were trying to be men, usurping a mascu-

ers Anthony Trent [London] Star line vocabulary that they could only possibly use in-

and Frank Bridge, authentically) and were condemned or at best treat-

mentioning Clarke The reviewer who remarks on Clarke's strength re- ed with curiosity. It is this curiosity - a polite, dis-

as a composer only

alises that this complement casts her femininity into tancing, patronising inquisitiveness - that permeates

as an afterthought:

'One should not, question. Thus the writer must qualify the remark - a 1926 review in the Musical Times of Clarke's Mid-

too, overlook Miss humorously, of course - to emphasise that if Clarke summer moon for violin and piano. Rather than con-

Clarke's own is unladylike in her creative efforts, at least she is sider the aesthetic value of this piece, the critic takes

picturesque compo- still within the bounds of propriety as far as her the opportunity to weigh the virtues of an abstracted

sitions, the 'Lullaby' physical attributes are concerned. 'new "woman-composer" ' against the 'old'.

and 'Grotesque' for

viola and cello.' The conservative turn of post-World War I Britain

has been memorably described in a recent book, The In reading Miss Rebecca Clarke's 'Midsummer

Moon' our first impression is one of relief and grati-

13. Cyrilla Barr female malady: women, madness and English culture,

presents a broad tude: for the new "woman-composer" is at least free

1830-1980, by Elaine Showalter, who notes 'the shift

perspective of from the cloying sentimentality of the old. ... May

of feminist interests away from questions of women's

Coolidge's influence nights and moonlight are no longer the source of

independence to questions of women's relationships

in 'A style of her gushing platitudes. The modern woman looks upon

own: reflections on with men.' She considers the emergence of what psy-

these things with the detachment of a scientist .

the patronage of choanalysts dubbed the 'masculinity complex',

She has an eye for the picturesque, but it is an eye

Elizabeth Sprague which saw feminists as women who sublimate their

undimmed by a rising tear. She is too keen, too de-

Coolidge', forth- desire to be men by 'following masculine pursuits of termined and too interested to be easily moved; her

coming in Cultivat- an intellectual and professional nature', and the in-ecstasy is of the mind rather than of the emotions.

ing music in Ameri-

fluence of Sigmund Freud, whose theories were re-This is all so much pure gain. At worst she can only

ca: women patrons

and activists since ceived enthusiastically in Britain.'1 This backlash toleave us cold; the others, when they really tried

1860, edited by first-wave feminism brought with it, then, the Victo- could be loathsome. With the instinct for change

Ralph P. Locke and rian double bind: that women who worked within and variety, with the flair for fashions which is wom-

Cyrilla Barr the acceptably feminine sphere were considered to an's own gift, she reaches the goal while the more

(Berkeley & Los cautious male hesitates and counts the cost. In the

be of little value (insignificant, in the lesser genres,

18 THE MUSICAL TIMES / MAY 1996

This content downloaded from

123.20.234.109 on Thu, 29 Feb 2024 20:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

end, perhaps, some males may strike deeper, but know that Clarke was an avid sewer, the metaphor Angeles, 1996). I

there is surely a good deal to be said for dashing bril- thank Professor Barr

can be identified as one of quilting. In fact, 'compos-

liance and frank unconventionality. for sharing her

ing, sewing, etc.' (24 February 1925) is a frequent

research with me in

Musical Times, 1 September 1926 entry, as is 'shopping, composing, etc.' Composing,

advance of publica-

then, while always important to Clarke, was seldom tion.

While this reviewer believes he is being progressive her primary activity

in his recognition and praise of the 'new "woman- This attempt to be a composer in a way that

14. Susan Faludi's

composer" ' he is actually restating the restrictions of would conform to her identity as a woman, was Backlash:

of- the unde-

the traditional double bind - the older type of wom- clared

ten difficult. For Clarke, the act of composing in- war against

American women

an composer wrote music of loathsome sentimental- volved complete self-absorption - a devotion to one's

(New York, 1991)

ity; the new woman instead provides scientific de- own creative worth, which meant some loss of iden-

convincingly de-

tachment and superficial brilliance; it is still only the tity, a giving up of everyday order in deference toscribes

an how wom-

male composer who is capable of depth. Uncon- unmeasurable internal power. Clarke writes of this

en's efforts to win

sciously conforming to this ideology, Clarke, then, experience in her memoir: equal treatment

avoided the masculine pinnacle of musical achieve- have always pro-

ment: she wrote no orchestral music, focusing in- duced cycles, with

... especially as a child, [I] often had the sensation advance followed

stead on the so-called 'lesser' genres of chamber mu- for no particular reason of being jolted right out of

by reactionary

sic and songs. Her largest works, as I have noted, my identity, to return almost instantaneously with a

repression.

were written as part of competitions to which works sort of bump and a sense of surprise at finding my-

were submitted anonymously, which perhaps en- self the same person as before. Even when grown

couraged her to ignore the confines of her feminini- up, a period of intense concentration - such as com-15. The female

ty. That Clarke felt more psychologically comfort- posing, lovemaking or anger - could bring on a re-malady: women,

turn of the same feeling. madness and English

able working with smaller scale pieces is, however,

culture, 1830-1980

demonstrated by her return to single-movement (London & New

works after the Coolidge festivals. I point this out as And, of studying at the Royal College:

York, 1985).

a pattern, and not to minimise the artistic achieve- pp.195-203.

It was a happy, ecstatic time. My work was improv-

ments of her creations. Clarke, I suggest, tried to re-

solve her conflict with the masculine associations of ing - slowly, but improving ... Every now and then,16. Christine Bat-

in the middle of struggling with some problem, ev-tersby's Gender and

composing by giving feminine attributes to her iden-

erything would fall into place with a suddenness al-genius (Blooming-

tity as a composer, rather than by trying to fit into

most like switching on an electric light. It may ton & Indianapolis

the masculine world of composing - the male-de-

sound pretentious, ... but at these moments, though 1989; London,

fined ethos of what a composer and what genius I had no illusions whatever about the value of my 1989) examines the

was.16 Indeed, her diary entry of 16 January 1924 il- work, I was flooded with a wonderful feeling of po- gendered status of

lustrates this feminising context and her view of genius.

tential power - a miracle made anything seem pos-

composition as an ornamental part of her identity: sible. Every composer, or writer, or painter too for

17. The letters of

that matter, however obscure, is surely familiar with

Fanny Hensel to

Had rather fun ... going with [her sister] Dora to buy this sensation. It is a glorious one. I know of almostFelix Mendelssohn,

some pearls! I am adding a few to the middle of my nothing to equal it. edited by Marcia

necklace with the money I have just got as royalties Citron (Stuyvesant,

from my songs. My pearls are to be all out of my 1987), p.xl.

N 1933, the same year that Freud completed his

compositions!

final essay on penis envy, Clarke completed a

song, a setting of Blake's 'The tiger', her darkest

While on the one hand we might simply say Clarke and only truly frightening work, bordering on

is buying the pearls to celebrate the success of herthe expressionist. For the previous five years, the

compositions, on the other, its use for a luxury em- obsessive reworking of that song had been almost

phasises what she is not doing as a composer - she is her only compositional effort. Perhaps in the wake

not earning a living. Clarke's words bring to mind of the preoccupations of feminists and psychiatrists,

what Fanny Mendelssohn's father wrote her in 1820 as well as the overall social climate of retrenchment

- 'for you it [music] can and must only be an orna-of traditional values concerning women, Clarke's in-

ment, never the root of your being and doing','7 aterests had been drawn to questions of relationships

quote which, whilst without equating the values ofwith men. More precisely, Clarke had an unhealthy

1820s Berlin with those of 1920s London, remindssecret relationship with a married man, the baritone

us of the long tradition of music as an ornament, John a Goss. Eight years younger than Clarke, Goss

decorative hobby for women. A viewpoint for Clarkewas well-known in London, and closely associated

as she strove to create an identity as a composer thatwith the composer Philip Heseltine, better known as

would be compatible with her feminine sensibilities Peter Warlock. Clarke wrote 'The tiger' for Goss, and

was thus readily available. Indeed, the act of com-many of her songs of the 1920s were premiered by

posing itself is, in her diary, often found among dis-and dedicated to him. The kindling of this romance

tinctly ladylike activities. In 1924, she wrote of com-in 1927, however, coincided with a drop in Clarke's

posing Midsummer moon: 'Started a fiddle piece us- output. (Her diaries end in 1933 so it is impossible

ing some old scraps'. (16 February 1924) Once we to know the conclusion of the affair.)

THE MUSICAL TIMES / MAY 1996 19

This content downloaded from

123.20.234.109 on Thu, 29 Feb 2024 20:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

18. As some writers

Clarke had first dedicated a song to Goss in 1922. ternational Society for Contemporary Music (held in

have generalised, This was 'The seal man', a long prose text by John Berkeley, California). Its acceptance by the Society

for instance, Citron:

Gender and the mu-

Masefield, based upon Celtic legend, the narrativecheered of Clarke; it was the only work by a woman,

sical canon, p.92;

which strikes me as an eerie prediction of what and one of only three by British composers. The re-

and Diane Peacock would happen to Clarke in her later romantic entan- views of this piece were positive, yet Clarke never

Jezic: Women com- glement with Goss. The story is a gender reversalshowed of it to any publishers.

posers: the lost tradi- the Greek legend of the Siren: a maiden of the Scot-This period of productivity was ended, not by her

tion found (New tish highlands falls in love with a seal (disguisedmarriageas to James Friskin,18 but rather by her taking

York, 1988), p.159. a man), and follows him out onto the sea, where 'she on a position as a governess in Connecticut in early

19. Letter from

was drowned of course, drowned, drowned'. Read 1942.19 in The job was gesture of independence to her

Eric's wife Beryl conjunction with Clarke's diary from later in the brothers, but in her writings she expressed surprise

stating that Rebecca decade and the early 30s, with its relentless series- of and despair - at finding herself, nearing the age of

was not going to rendezvous, recriminations, break-ups and make- 60, in exhausting, non-musical employment for the

spend the summer ups, it is easy to sense that some part of Clarke her- first time in her life. Her writings from this time are

with them (Spring self is drowning in these years; certainly the com- not the meticulous diaries of earlier years, but

1942).

poser part seems deeply submerged. rather, long undated lists of observations, written in

20. Interview with In her 1976 interview, she is asked why she didn't a large hand with blunt pencil on legal pad. She is

Christopher John- continue to compose. clearly struggling to keep up her spirits, as a few

son (January 1994). poignant quotations attest. These writings, labelled

I wanted to, but I couldn't. I had lots of sketches of 'Observations', are numbered but not dated:

21. He taught there things. I know and I miss it, because there's nothing

for 52 years. in the world more thrilling - or practically noth- 53

ing... But you can't do it - at least I can't - maybe Funny to have to use the back door instead of the

22. For instance, that's where a woman's different - I can't do it unless front.

her diary, 18 Febru- it's the first thing I think of every morning when I

ary 1920: 'Went up

to the Mannes

wake and the last thing I think of every night before 58

School at 4:30 to I go to sleep - I've got to have it in my mind all the I can understand Hitler when I see boys playing in

hear trios played by time and if one allows too many other things to take sand-box: 'It's mine' 'No, it's mine.' I fear war will al-

Mr and Mrs over one is liable not to be able to do it, that's been ways exist.

M[annes] and my experience.

Casals. Casals, who 69

played very badly So Clarke's impulse to compose was submerged but My fingers are puckered from all the washing I have

indeed last night, not gone. In 1939 came another accident - not a to do - self, children, bedding, dishes. Hard to play

played most happy one for Clarke or for anyone, but it did effec- well that way.

beautifully today. tively separate her from the distractions that kept

Sat with Friskin and

her from composing - World War II. 102

talked a lot with

As relatives tell the story, Clarke was visiting her Difficult to realise that the sun still shines in London

him, queer, shy

brothers in the US during the summer of 1939 when as much as it ever does.

thing that he is.

Nothing in the Britain declared war. Since London was being evacu-

152

evening.' ated, she decided to remain with her brothers and

their families. These years, 1939-42, were a remark- Unreal experiences seem quite natural while they

23. These letters are are present. But one sometimes thinks even at the

able compositional efflorescence, and Clarke's final

among the few that time: I shall not believe I have ever done this. We are

survive in Clarke's period of musical creativity. There was ultimately

friction in both families as the wives saw Rebecca as adaptable creatures.

estate. They remain

in the 'Tall Gals' attempting to usurp roles of leadership within the 172

shoe box (size 11) family, and she saw her brothers as taking on the

Letter from England - mirage-like effect switching

that she stored cruelty of their father. It was a very unhappy time for

them in. me away from this hour's failure.

Clarke, but unlike her unhappy involvement with

24. Clarke and John Goss, it was musically productive. In this way, 188

Friskin were with Clarke living within the confines of her family, I compose them [the children] to sleep

married on 23 there might be some parallels to the years when, as

September 1944 a teenager still cowering before her father, Clarke 214

(marriage certificate had first started to compose. Strange that an absent-minded moody musician

in Clarke's estate).

The ten pieces from this period include a broad should be doing this!

Joseph Clarke died

on 23 September range of styles - particularly striking is the Prelude,

1920, as document- allegro, and pastorale. Here the lyrical breadth and Clarke's chance meeting on a Manhattan street

ed in Rebecca's rich, developmental thematic treatment of her earli- with pianist James Friskin in early 1944 was de-

diary and er music is replaced by a tautness, contrapuntalscribed as 'rain in the desert'.20 They had been stu-

Stammtafeln der agility, crisp melodic style, and an energetic use ofdents together at the Royal College, with Friskin

Familie Ranke

asymmetrical rhythms that suggests comparison studying composition and piano. He had given up

(Cologne, 1976),

p.20. with the neo-classical Stravinsky. This piece was onecomposition on accepting a position at the Juilliard

of 35 works included in the 1942 meeting of the In-School.21 They had also known each other during

20 THE MUSICAL TIMES / MAY 1996

This content downloaded from

123.20.234.109 on Thu, 29 Feb 2024 20:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Clarke's American visits of the early 1920s22 but they Dumka for violin, viola and piano

had not seen each other for a considerable period,

and their meeting came at a time when it made them

both particularly happy. Their surviving courtship

letters brim with intense warmth and enthusiasm.23

Clarke to Friskin:

N CO P h: .. ....... ......

Did I tell you,James, that I love you?! Do you know

that, more and more, I feel - just as you told me you

it1 )j,1 - A-4

did - that all my life has been a kind of preparation

for you?

4 . ...........

24 August 1944

Friskin to Clarke:

I want to tell you again, specially for your birthday,

that I love you as I had thought it had not been giv-

en to me to love any woman. I knew there was such

love, but I had made up my mind that I must be con-

tent without it. So perhaps you can imagine what iai

these recent weeks have meant to me.

25 August 1944

Friskin can be cleared of any notion that he played a

Gustav Mahler role towards Clarke's composing. Her

next-to-last composition was written for him, a set- >- 47I

ting of a Scottish melody, and he reacts to it posi-

tively, suggesting they show it to publishers.

After looking again at the last twelve bars for your

-1?_- 4i F

little viola piece, which I find very moving, it seems

to me that you ought to start off again on something

larger - I'd almost be willing to bet it's there if you'ld

only let it come out. What about another viola

sonata? Please try. r I hi.iifil~iliiiili~ii

24 July IT,

Ai"iii:i U1.

iii:i'ii ii

Clarke does not respond to this directly (or at least iLt.i- iJ,

none survives). Instead, her letter of 20 August in-

cludes a traditionally feminine token of devotion:

'Will you someday let me knit something for you?' Artur Rubinstein summed up the

25. Letter opinion

from Ru- o

Surely some part of her conscious or unconscious the luminaries that she, before World War II, binstein to Clarke

mind was aware that her wedding took place on the worked with on a regular basis, when he called her(10 February 1966),

anniversary of her father's death.24 At last Clarke had 'The glorious Rebecca Clarke'!25 quoted by Christo-

pher Johnson in

found a man who gave her a sense of deep satisfac- By recognising that Clarke's identity as a composer

notes to the North-

tion and equilibrium. Clarke and Friskin were both clashed with her identity as a woman, I do not mean eastern recording of

58 when they married. Apart from one last song, and to portray Clarke as weak or as victimised but simplyClarke's viola music

some revisions of earlier works, Clarke would not to recognise some of the forces that shaped her - we all(LP 1985,

compose for the rest of her life, 35 more years. have to balance the tensions that pull our lives in dif-CD 1989).

Rebecca Clarke remained active and mentally ag- ferent directions. This is certainly part of her appeal as

ile until her death at 93. Documents such as her fas- a figure - her self-doubt makes her a figure of empa-

cinating memoir, which she started writing after her thy, giving her a human warmth that so many of her

husband's death, reveal her reflections and revela- male contemporaries in the panoply of 'great' com-

tions on events decades earlier. Thus writing in the posers lack. Her entire mature life, Clarke held onto to

1960s, she contemplates that she grew up in a sexu- her identity as a composer but she also constantly

I gratefully ac-

ally repressive age, and in her memoir and in the in- struggled with this identity. Our century has seen

knowledge the

terviews finally observes that, as a woman compos- many changes, great upheavals in the nature and defi- generosity of

er, she was occasionally treated unfairly. During the nition of music, and with them changes in the identi- Clarke's heirs, in

course of her long life, Clarke touched a great many ty of what a composer is; the roles defined for women particular

lives with her deep love of chamber music, the com- have changed as well. While today obstacles remain Christopher

it John-

son and Daniel C.

pelling voice of her compositions, and also her is encouraging and uplifting that Clarke lived into an

Braden, for access

warmth and charm. She taught extensively, but, to age in which women could be more honestly accepted

to and permission

my knowledge, entirely privately, viola, violin, theo- as composers. She lived to see that the artistic worth to

of quote from un-

ry and composition. Even those who knew her only her music was being rediscovered, a process that con- published material

late in life speak of her energy and lively wit. And tinues today in Clarke's estate.

THE MUSICAL TIMES / MAY 1996 21

This content downloaded from

123.20.234.109 on Thu, 29 Feb 2024 20:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- The Cello Suites: J. S. Bach, Pablo Casals, and the Search for a Baroque MasterpieceFrom EverandThe Cello Suites: J. S. Bach, Pablo Casals, and the Search for a Baroque MasterpieceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (97)

- Rebecca ClarkeDocument6 pagesRebecca ClarkeKevie YuNo ratings yet

- Women Composers by Diane Jezic (Overview)Document1 pageWomen Composers by Diane Jezic (Overview)Helios KnoxNo ratings yet

- Passacaglia CelloDocument3 pagesPassacaglia CelloJorge Junior100% (1)

- Yasmin Fainstein, Program NotesDocument3 pagesYasmin Fainstein, Program NotesYasmin FainsteinNo ratings yet

- AMIS RainierDocument5 pagesAMIS Rainierharald0No ratings yet

- CasellaDocument5 pagesCasellaMatteo QuerellaNo ratings yet

- Walter de La Mare SchooldaysDocument36 pagesWalter de La Mare SchooldaysNigel Edmund-JonesNo ratings yet

- Arnold BaxDocument18 pagesArnold BaxBob LablaNo ratings yet

- Underrated Women ComposersDocument6 pagesUnderrated Women Composersapi-510675698No ratings yet

- Vincent Duckles - The "Curious" Art of John WilsonDocument21 pagesVincent Duckles - The "Curious" Art of John WilsonFelipeNo ratings yet

- The New London Orchestra Ronald Corp: IncludingDocument17 pagesThe New London Orchestra Ronald Corp: IncludingAnonymous qZY4l1aCEu0% (1)

- The World of ChaucerDocument225 pagesThe World of ChaucertiagomluizzNo ratings yet

- Arts Edu RoadMap EsDocument90 pagesArts Edu RoadMap EsJorge BirruetaNo ratings yet

- Phoenix Redivivus Beachs Posthumous ReputationDocument12 pagesPhoenix Redivivus Beachs Posthumous ReputationJulia MillerNo ratings yet

- Woman's Art Inc. Woman's Art Journal: This Content Downloaded From 52.31.199.201 On Mon, 13 May 2019 10:23:03 UTCDocument8 pagesWoman's Art Inc. Woman's Art Journal: This Content Downloaded From 52.31.199.201 On Mon, 13 May 2019 10:23:03 UTCMaria CarrerasNo ratings yet

- Kellogg MemoirsDocument496 pagesKellogg MemoirsYBNo ratings yet

- CA21192 Moondog Album BookletDocument16 pagesCA21192 Moondog Album BookletcantaloupemusicNo ratings yet

- F - Composer BiosDocument5 pagesF - Composer BiosCameron Biles-LiddellNo ratings yet

- Ives The Unanswered QuestionDocument3 pagesIves The Unanswered QuestionVictoria Hao100% (1)

- Renaissance: MotetsDocument2 pagesRenaissance: Motetsjhark1729No ratings yet

- 100 Records That Set The World On Fire (While No One Was Listening)Document23 pages100 Records That Set The World On Fire (While No One Was Listening)Manuel Alfredo Ayulo RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Mapa Conceptual Ingles Musica PDFDocument2 pagesMapa Conceptual Ingles Musica PDFAstrid ValderramaNo ratings yet

- York Bowen Viola Concerto FinalDocument7 pagesYork Bowen Viola Concerto FinalThe Land of Lost Content33% (3)

- Current - Musicology.55.macdonald.24 55Document32 pagesCurrent - Musicology.55.macdonald.24 55Yang Yang CaiNo ratings yet

- THE TEACHING OF SAXOPHONE OVER TIME: From Adolphe Sax to the present dayFrom EverandTHE TEACHING OF SAXOPHONE OVER TIME: From Adolphe Sax to the present dayNo ratings yet

- Dance Index 1Document16 pagesDance Index 1mordidacampestreNo ratings yet

- Rosalyn TureckDocument3 pagesRosalyn TureckPerez Zarate Gabriel MarianoNo ratings yet

- Amphitheatrvm Sapientiae AeternaeDocument550 pagesAmphitheatrvm Sapientiae AeternaeConst VassNo ratings yet

- The New English Keyboard SchoolDocument7 pagesThe New English Keyboard SchoolHeoel GreopNo ratings yet

- Elgar and HolstDocument18 pagesElgar and HolstIvarNicholas FojasNo ratings yet

- Copland Sonata AnilisiDocument3 pagesCopland Sonata AnilisiFabio CastielloNo ratings yet

- Williams Chamber Players: Souvenirs: Program NotesDocument4 pagesWilliams Chamber Players: Souvenirs: Program NotesDima MusicianNo ratings yet

- The Story of ViolinDocument376 pagesThe Story of Violinchircu100% (3)

- Uneventful Music in Eventful TimesDocument4 pagesUneventful Music in Eventful TimesRaymond DeaneNo ratings yet

- Lennox BerkeleyDocument9 pagesLennox BerkeleySergio Miguel MiguelNo ratings yet

- Gramophone - January 2023Document140 pagesGramophone - January 2023ipromesisposiNo ratings yet

- Music On ShakespeareDocument140 pagesMusic On Shakespearedanielll17No ratings yet

- Freitas Singing Herself 2019Document83 pagesFreitas Singing Herself 2019Nicholas TranNo ratings yet

- BBC Music 12 2023Document106 pagesBBC Music 12 2023Oscar Jose UnamunoNo ratings yet

- This World Is Not Conclusion - Dickinson, Amherst, and - The Local Conditions of The SoulDocument19 pagesThis World Is Not Conclusion - Dickinson, Amherst, and - The Local Conditions of The SoulTako ChanNo ratings yet

- Performing Sergei Rachmaninoff's All-Night VigilDocument13 pagesPerforming Sergei Rachmaninoff's All-Night VigilAlejadro Morel CoronadoNo ratings yet

- Clarke: StanleyDocument1 pageClarke: StanleyАлександр ВитюкNo ratings yet

- History of Music PDFDocument474 pagesHistory of Music PDFAndres Barrios Moreno100% (3)

- The Standard OratoriosTheir Stories, Their Music, and Their Composers by Upton, George P. (George Putnam), 1834-1919Document135 pagesThe Standard OratoriosTheir Stories, Their Music, and Their Composers by Upton, George P. (George Putnam), 1834-1919Gutenberg.org100% (2)

- St. Louis Symphony Program - Oct. 5-6, 2013Document16 pagesSt. Louis Symphony Program - Oct. 5-6, 2013St. Louis Public RadioNo ratings yet

- Clara SchumannDocument103 pagesClara Schumannfrb100% (1)

- Britten - Saint Nicolas Hymn To Saint CeciliaDocument17 pagesBritten - Saint Nicolas Hymn To Saint CeciliaMihailo JovisevicNo ratings yet

- John Cage's "The Wonderful Widow of Eighteen Springs": Lauriejean ReinhardtDocument8 pagesJohn Cage's "The Wonderful Widow of Eighteen Springs": Lauriejean ReinhardtMoxi BeideneglNo ratings yet

- BookletDocument16 pagesBookletStefanoMolendiNo ratings yet

- John Corigliano The Red Violin PDFDocument5 pagesJohn Corigliano The Red Violin PDFSendiOrysalAltoNo ratings yet

- BerkeleyDocument5 pagesBerkeleyPaolo BrosioNo ratings yet

- The History of JazzDocument4 pagesThe History of JazzRomina Neagu100% (2)

- Barber 2 Obra y EstiloDocument7 pagesBarber 2 Obra y EstiloEliasNo ratings yet

- The Appearance of The Electric Bass Guitar: A Rockabilly PerspectiveDocument18 pagesThe Appearance of The Electric Bass Guitar: A Rockabilly Perspectivesonus.ensambleNo ratings yet

- The "Curious" Art of John WilsonDocument20 pagesThe "Curious" Art of John WilsonZappo22100% (1)

- Cdma 450Document31 pagesCdma 450Arsalan Badar Wasti100% (1)

- 2015 Boom! Box Owner's Manual: I NF or Mat I On PR Ovi Ded byDocument244 pages2015 Boom! Box Owner's Manual: I NF or Mat I On PR Ovi Ded byBabita NayakNo ratings yet

- Man S22a Plus EngDocument47 pagesMan S22a Plus EngNastasoiu NeluNo ratings yet

- Freak TestDocument3 pagesFreak TestDaniel Peter100% (3)

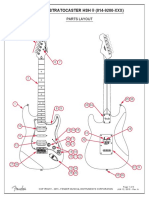

- Fender STD Stratocaster HSH 0149200XXX Service ManualDocument4 pagesFender STD Stratocaster HSH 0149200XXX Service ManualzencubiNo ratings yet

- Examen Final Ingles 3 CorregidoDocument10 pagesExamen Final Ingles 3 CorregidoHalber vargasNo ratings yet

- Catalogo 4-AbrilDocument70 pagesCatalogo 4-AbrilLuis Alberto GrandeNo ratings yet

- Background DesignDocument26 pagesBackground DesignJosias NogueiraNo ratings yet

- Prueba de Diagnóstico 6th REVISADODocument3 pagesPrueba de Diagnóstico 6th REVISADODenisse RojasNo ratings yet

- GS65 BJ - User Manual R3 FINAL PDFDocument11 pagesGS65 BJ - User Manual R3 FINAL PDFrmendoza85No ratings yet

- Quiz Grade 6 PH 3Document5 pagesQuiz Grade 6 PH 3Citraandewi NugrahaningtyasNo ratings yet

- Hospital UniformDocument36 pagesHospital UniformitskartheeNo ratings yet

- Arcanist SheetDocument28 pagesArcanist SheetfiggyballNo ratings yet

- MakatoDocument3 pagesMakatoJanine SalanioNo ratings yet

- Contemp. Arts Module 3Document19 pagesContemp. Arts Module 3ibganraffy22No ratings yet

- Travel To BrazilDocument7 pagesTravel To BrazilfishfishNo ratings yet

- Harmonic Minor ChordsDocument3 pagesHarmonic Minor ChordsRoy Verges67% (3)

- EEDIDguide V1Document18 pagesEEDIDguide V1giorgioviNo ratings yet

- Dungeon Siege ManualDocument48 pagesDungeon Siege Manualtime wizardNo ratings yet

- Somewhere Only We KnowDocument5 pagesSomewhere Only We KnowYanina GarridoNo ratings yet

- BUDocument20 pagesBUHarriet Cong-o GayaoNo ratings yet

- Lenovo Y70-70 Touch/ Y70-80 Touch: User Guide User GuideDocument31 pagesLenovo Y70-70 Touch/ Y70-80 Touch: User Guide User GuideYote MeNo ratings yet

- SCRIPTDocument2 pagesSCRIPTArchie Gabuyo Jr.No ratings yet

- Homework - U1 Vocabulary Review - American English File Starter - Unit 1Document11 pagesHomework - U1 Vocabulary Review - American English File Starter - Unit 1BarbaraNo ratings yet

- Bài Tập Tiếng Anh 9 -Mai Lan Hương - Hà Thanh Uyên Unit 7Document19 pagesBài Tập Tiếng Anh 9 -Mai Lan Hương - Hà Thanh Uyên Unit 7giahungsr74No ratings yet

- Can Humor Ever Be SeriousDocument2 pagesCan Humor Ever Be SeriousHanazonoSakuraNo ratings yet

- Tom Jones SummaryDocument1 pageTom Jones SummarypanparasNo ratings yet

- Breathing Exercises For VoiceDocument2 pagesBreathing Exercises For Voiceapi-3829725No ratings yet

- Camarines SurDocument5 pagesCamarines SurMike SemanaNo ratings yet

- Going Places 2Document8 pagesGoing Places 2Om KanaujiaNo ratings yet