Professional Documents

Culture Documents

18.ali - Fragmentation Gender Iraq

Uploaded by

Abdoukadirr SambouOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

18.ali - Fragmentation Gender Iraq

Uploaded by

Abdoukadirr SambouCopyright:

Available Formats

The Fragmentation of Gender in Post-Invasion Iraq

Oxford Handbooks Online

The Fragmentation of Gender in Post-Invasion Iraq

Zahra Ali

The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Middle-Eastern and North African

History

Edited by Amal Ghazal and Jens Hanssen

Subject: History, Gender and Sexuality Online Publication Date: May 2017

DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199672530.013.42

Abstract and Keywords

This chapter explores the evolution of gender and women’s rights struggles in Iraq since

the establishment of the Personal Status Code in 1959 and shed light on the

ethnosectarian fragmentation of women’s legal rights in post-invasion Iraq. The chapter

argues that in order to explore women’s rights and conditions of lives in Iraq it is

essential to explore the evolution of women’s rights and gender issues historically and

through a complex lens of analysis rather than applying a predefined argument involving

an undifferentiated “Islam” or age-old gender-based violence. It seeks to show that

gender issues have been entangled with issues of nationhood, religion, and with the

nature of the political regime since the very foundation of the Iraqi Republic in 1958.

First, the chapter examines the debates and mobilizations around women’s legal rights in

Iraq. Secondly, it highlights the development of political, economic, and military violence

since the 1980s and its impact on gender norms and relations. Finally, it analyzes the

specific context of ethnosectarian fragmentation in which Iraqi women have lived and

mobilized since 2003.

Keywords: Iraqi women, women’s rights and gender issues, war, Ba‘th regime, US-led invasion and occupation.

Page 1 of 21

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: University of Arizona Library; date: 28 July 2018

The Fragmentation of Gender in Post-Invasion Iraq

Since the invasion by ISIS in June 2014 of parts of northern and western Iraq, images of

women brutalized by the terrorist group, especially from minority communities such as

Yazidis, were spread across the global media and social networks. The systematic use of

enslavement and rape of women and girls from ethnic and religious minorities by ISIS

soldiers characterized one of the most horrific forms of sexual violence. These terrible

images can easily lead to a simplistic reading of women’s rights and gender issues in Iraq

that would reduce gender-based violence to issues of religious fundamentalism. However,

instead of limiting the reading of the Iraqi context to the rise of ISIS, it is essential to look

carefully at the structural social, economic, and political dimensions that allowed this

extreme version of religious fundamentalism to exist. Gender and women’s rights issues

in Iraq need to be looked at through a complex lens and a historical analysis that goes

back, for the purpose of this discussion, to at least the establishment of the first Iraqi

Republic in 1958. The fact that gender and ethnic issues intersected with one another in

the enslavement of Yazidi women by ISIS reveal deep social, economic, and political

dynamics that have evolved historically and therefore demand further analysis.

Considering Islamic fundamentalism in Iraq or elsewhere in Muslim majority countries as

the main root of women’s oppression and gender-based violence is perhaps another way

of stating that “Islamic culture” is patriarchal in essence and to blame for women’s

oppression. It also means considering one variable—religion—as the unique medium of

gender-based violence. In line with robust postcolonial feminist literature, the first point

to be made is that “Islamic culture” does not exist as a homogeneous reality and in a

vacuum, neither does “Islamic fundamentalism.”1 Furthermore, “Islam”—if we want to

use this word to refer to a very diverse religious and cultural frame—has been practiced

and interpreted very differently throughout time and space, as well as in diverse social

and economic contexts.2 By now, it is clear that religion does not exist as an essence

outside social, political, and economic transformations but rather in complex relations

with these. In this regard, Iraq is an instructive case that shows how much “Islam” has

been interpellated and turned into jurisprudence in the context of postcolonial state-

building processes. My research on women and gender issues in Iraq shows how religion

has long been imbricated with matters of nationhood and that this overlapping has been

very much gendered. Thus, taking a more historical and intersectional approach to this

matter will provide a better understanding of women and gender issues in Iraq today.

This chapter takes a reflexive approach as I explore women’s rights and activism

ethnographically, relying on fieldwork conducted within women’s rights groups in Iraq3,

and historically through a study of the evolution of women’s social, political and economic

experiences since 1958. I argue that when looking at the social and political mobilizations

around women’s rights in post-2003 Iraq, it is essential to explore the very concrete

realities in which Iraqi women live and the broader social, political and economic

contexts that shape their experiences, rather than applying a priori argumentation

involving an undifferentiated “Islam”. In this chapter, I outline three essential dimensions

to consider when looking at this matter. First, looking at the evolution of the struggles

around women’s legal rights in Iraq, I show the importance of going beyond a simplistic

analytical frame involving gender issues to religion. Secondly, I highlight the importance

Page 2 of 21

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: University of Arizona Library; date: 28 July 2018

The Fragmentation of Gender in Post-Invasion Iraq

of considering violence, especially the development of political, economic, and military

violence in Iraq since the 1980s and its impact on gender norms and relations. Then,

looking at the specific context in which Iraqi women lived and mobilized since 2003 will

provide key elements for understanding the general social and political fragmentation of

the country and its gender dimensions.

Page 3 of 21

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: University of Arizona Library; date: 28 July 2018

The Fragmentation of Gender in Post-Invasion Iraq

Beyond “Gender in Islam”: The Evolution of

Women’s Legal Rights in Iraq

The Personal Status Code (PSC) also known as the Family Law is the main legal frame

based on Muslim jurisprudence and adopted by many Muslim majority states at the time

of their independence from European imperial powers. This code gathered legislation

regarding private matters such as marriage, divorce, child custody, inheritance,

effectively most of women’s legal rights.4 The PSC represents a field of struggle between

different social and political groups: the state, the ‘ulemas, the tribal leaders and social

and political movements including the women’s movement.5 In Iraq, the adoption of an

openly pro-women’s rights PSC in 1959 (in the form of Law no. 188) was not only due to

the political culture of the revolutionary elite that came to power through ‘Abd al-Karim

Qasim (1914–1963)’s 1959 coup, but also signaled the questioning of ‘ulemas’ and tribal

leaders’ dictates over private matters. Crucially, the adoption of this code marked the

beginning of women activists’ inclusion in the process of negotiating for their rights. As

an example, Naziha al-Dulaymi (1923–2007) gynecologist by trade, a prominent figure of

the League for the Defense of Women’s Rights,6 the first Iraqi and Arab female minister,

and prominent communist activist participated to the drafting of the PSC. The PSC

adopted in 1959 put certain intestate inheritance rights for male and female heirs under

Civil Code and thus granted through an undirect mechanism gender equality in certain

cases in that matter.7 This one of the most sensitive and sacrosanct issues within both

Sunni and Shia fiqh (Muslim jurisprudence), along with the severe limitations placed on

polygamy, and the adoption of 18 years old as the minimum legal age for marriage for

both sex, represented a strong political statement by the new Iraq Republic, that directly

challenged the power of ‘ulemas in urban areas. As for rural areas, the abolition of the

Tribal Law, which had given tribal sheikhs the power to decide over personal matters,

constituted an essential part of the new state’s modernization project. The text of Law no.

188 was clearly inspired by different schools of fiqh and operated within sharia, thus

eliminating the differential treatment of Sunnis and Shi’as and allowing state-trained and

appointed judges to rule on personal matters without consulting the ‘ulemas. Thus, the

new PSC gathering both Sunni and Shi’a jurisprudences provided a legal frame

applicable equally to all Muslim Iraqis. This makes the Law no. 188 a symbol of both the

new nation’s unity beyond ethno-sectarian lines and the inclusion of women’s rights

activists’ demands through their participation in the legislative process itself.8 This shows

the strong relationship between issues of nationhood and gender in postcolonial Iraq: at a

time when the political culture was marked by the anti-imperalist left both ethno-

sectarian unity and pro-women’s rights aspirations were linked to one another. The

revolutionary regime aspired to provide, and even more importantly determine the rights

of its citizens in linking issues of nationhood with issues of gender.

Page 4 of 21

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: University of Arizona Library; date: 28 July 2018

The Fragmentation of Gender in Post-Invasion Iraq

In comparison with most Muslim majority contexts, it is crucial to understand the PSC as

a field of struggle between newly independent states, political elites, and social and

political movements, especially when considered within the political context of contesting

European imperialism, which resulted in the discursive claim of authenticity and

resistance to Western models. During early independence the landed Iraqi nationalist

elite attempted to build a strong state that would be the arbitrator of all matters

pertaining to civil law undermining its direct competitors—tribal leaders and ‘ulemas-.

However in this postcolonial context marked by the western/indigenous modern debate in

which women were deemed as “bearer of the nation” and through which issues of

“cultural authenticity” were played, the field of family and women’s legal rights remained

the only field submitted to the so-called “authentic” authority of sharia in the frame of the

PSC. The “authenticity” and “indigeneity” of the emerging “nation” relied on the

compliance of women and family issues to “Islam”.

Women activists, therefore, were forced to operate in the spaces between state-building

and nation-building projects. They were, and are still, caught between these two separate

but entwined projects that together reinscribed or reproduced patriarchal structures and

practices legitimized by a so-called “Islam” used as symbol of an “authentic” culture. As

Suad Joseph’s research has demonstrated, from the 1970s to the end of the 1980s, the

centralized Iraqi political power—unified around the authoritarian Baath Party and

supported by oil revenues—came to impose state authority at every level of society,

including at the community and family level.9 Joseph contrasted the situation of Iraq with

that of Lebanon which is a country as religiously and ethnically diverse but whose elite

was even more heterogeneous, factionalized, and supported by fewer resources and thus

with a weaker state. The Lebanese republic had passed a community-based PSC, as the

non-interventionist state deferred to religious institutions matters regarding women and

the family. In Iraq in contrast, the Baath regime attempted to subordinate family to the

state by taking over family functions—child socialization, healthcare, and social control—

and to transform the family from a unit of production to a unit of consumption. Until the

mid-1980s, the Baath regime subsidized the nuclear family in order to shift tribal,

religious and sectarian allegiances to the state.10

In the 1970s, women activists who mobilized for their legal rights in the very limited

political pluralism of the increasingly authoritarian Baath regime, were able to push for

even more progressive reforms. Their efforts were supported by full employment and the

regime ideological narrative promoting a pro-women secular socialism. However, by the

mid-1980s, with the country at war with Iran, the women’s movement was reduced to the

General Federation of Iraqi Women (GFIW), which became a mouthpiece for Baathist

ideological turn into a more conservative discourse regarding family and gender issues.

In this period of economic weakening of the regime that concentrated its budget to the

war effort, women were invited to go back to their houses and give birth to the “future

soldiers of the nation”.11 After the 1991 Gulf War, the politics of “state feminism”

witnessed a dramatic reversal, as this period was marked by the political and economic

weakening of the Baath Party; six weeks of devastating US-led bombings; the regime’s

brutal crackdown on the northern and southern uprisings; and a decade of severe, UN-

Page 5 of 21

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: University of Arizona Library; date: 28 July 2018

The Fragmentation of Gender in Post-Invasion Iraq

imposed economic sanctions. All of these factors signaled the end of Iraq’s reign as a

regional power, plunging its middle class into poverty, destroying its infrastructure, and

ruining its social, educational, and health systems. Once reputed as the country with the

most educated women and home to one of the most developed and effective higher

education systems in the region, Iraq in the 2000s had one of the highest rates of

illiteracy and infant mortality. The dismantling of the education system, the public sector,

and state services as a result of sanctions, therefore, had a direct impact on the everyday

lives of Iraqi women.12 In her research on the gender impact of the UN sanctions, Al-

Jawaheri noted the emergence of new forms of patriarchy in extremely impoverished

contexts.13 The Baath Party aligned itself with the rise of political Islam in the region,

forging anew the Islamic and tribal nature of the Iraqi identity. Under the banner of the

al-hamlay al-imanyah (“the Faith Campaign”), President Saddam Hussein added “Allahu

Akbar” to the Iraqi flag, portrayed himself as a pious Muslim, Islamized public discourse

and funded the construction of huge mosques. In addition, measures were imposed

regarding women’s legal rights. Now a mahram (a male relative) was required in order

for women to travel abroad; severe punishments for prostitution were imposed; and the

legislation tolerating crimes committed “in the name of honor” was reinforced.14

The US-led invasion and occupation of Iraq in 2003 has exacerbated the social, economic

and political crisis in which the country has been plunged since 1991, and framed it in

ethno-sectarian lines. In this context marked by the institutionalization of communal—

ethnosectarian and ethnoreligious—identities by the US-led administration and the

extreme weakening of the state, the PSC has once again taken a central role in debates

about issues of nationhood and statehood. The US-led administration put in power

ethnosectarian political groups that were at the marge of power under the Baath regime,

Shia Islamist parties and Kurdish nationalists. In Arab Iraq, the US-led politics through

the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) marked by the institutionalization of a

communal based political system, a marginalization of the Sunni population alongside

with the destruction of the old state’s institutions, in addition to the contestation of the

occupation itself by most Iraqis, plunged the country into a sectarian war. The post-2003

context is characterized by an extremely weak state, a largely contested political regime

and the very fragmentation of Iraqi nationhood through the separation of the Kurds and

the Arabs, and the Sunni-Shi’a political divide. While Kurdish nationalists dealt with the

PSC on nationalist terms in the separate territory of Iraqi Kurdistan. Shi’a Islamists,

driven by the defense of their politico-sectarian identity, pushed for a questioning of the

unified PSC on sectarian grounds through different propositions that all introduce the

possibility of a sectarian based PSC: Decree 137 proposed in 2003, Article 41 of the new

Iraqi Constitution adopted in 2005 and more recently in 2014 the Ja’fari Law proposition.

The latter, based on the Ja’fari school -main Shi’a religious school in Iraq- could allow the

marriage of girls since the age of 9 years old considered by the Ja’afari school as sin al-

balagha (the age of maturity), and allow precarious forms of marriage in which women

and girls loose legal protection. Activists of the Iraqi Women Network (IWN) the main

independent women’s rights platform in Iraq since 2003, were firmly opposed to all these

measures, defending the Law no 188 for its inclusion of all Muslim Iraqis. According to

Page 6 of 21

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: University of Arizona Library; date: 28 July 2018

The Fragmentation of Gender in Post-Invasion Iraq

IWN activists, Decree 137, Article 41 and the Ja‘fari Law proposition brought the very

notion of the comparatively progressive and unifying PSC into question on both religious

and sectarian grounds. In turn, many civil society activists expressed fears over both the

adoption of a system based on a regressive and conservative reading of Muslim

jurisprudence and the sectarianization of women and family issues. Significantly, Sunni

Islamists also opposed these propositions, siding instead with the preservation of a

unified code that facilitates intercommunal marriage. Conversely, most Shi’a Islamist

women activists supported the Ja‘fari Law, considering it to be an affirmation of the

freedom to practice Shia Islam after decades of repression under the Baath regime.

According to a survey conducted by a women’s organization in southern Iraq which

confirmed my own research, even the majority of the Shia population (70%) considered

Article 41 to threaten the unity of Iraq.15 Most Shia clerics also opposed the Ja‘fari Law,

or example, Hussein al-Sadr—a prominent Shi’a cleric—stated that it was better for the

state to adopt civil legislation in line with international conventions and leave issues of

sharia to the clerics: “We want Iraq to be a civilian [madani] and civilized [mutahadhar]

state.”16 The fact that most of the Shi’a population and clerics also oppose the

sectarianization of the PSC shows how much this issue does not divide Sunnis and Shi’as

on strictly religious-sectarian lines, but rather on political-sectarian lines. Shi’a Islamists

who are in power push for a sectarianization of the PSC which is synonymous for them of

more power, while Sunni Islamists who are on the marge of power defend a unified PSC

to make sure that Sunnis would be treated as equal citizens.

This brief history of the challenges to women’s legal rights highlights the extent to which

gender issues are entangled with ideas of nationhood, and increasingly with sectarian

issues, as well as the nature of political regimes and the way it framed women’s activism.

Gender issues were continually raised throughout the Baathist project, oscillating

between Arab-Socialist nationalism and a tribalism colored by Islam. Subsequently,

conflicting gender politics can be seen to have economic, political, ideological, and

sociodemographic triggers. Such ambivalent legacies partly defined the ways in which

the PSC has been debated in the post-2003 context.

So far, my analysis of the formation and deformation of women’s legal rights in Iraq has

shown that the question cannot be reduced to the static perspective of “gender in Islam.”

If the interpretation of “Islam” was in favor of more egalitarian conceptions of women’s

rights between the 1950s and the 1970s, it was the product of a particular social,

economic, and political conjecture in which a gendered secular leftist nationalist

narrative dominated Iraqi political culture. The same “Islam” was interpreted in a more

conservative way in the 1980s and 1990s owing to militarization and general

impoverishment. Since 2003, the violent fragmentation of the country negatively affected

the very existence of a unified frame of women’s legal rights, and “Islam” is interpreted

through conservative sectarian lines.

Page 7 of 21

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: University of Arizona Library; date: 28 July 2018

The Fragmentation of Gender in Post-Invasion Iraq

The Military, Political, and Economic

Genealogy of Gender-Based Violence in Iraq

Iraq has become one of the most brutalized countries in the world. In addition of having

experienced one of the most authoritarian regimes in the region, its population has been

plunged into several devastating wars starting in the early 1980s with the war with Iran.

Iraq seems to have been in a “state of war” since then as military violence has

characterized its everyday reality until today. The devastating impact of the UN sanctions

after the invasion of Kuwait in 1990 is still palpable today. Each of these forms of violence

has brought about the militarization and thus celebration of masculinization of Iraqi

society which, in turn, also carry ethnic and sectarian dimensions.17 Thus, this violence is

both gendered and ethnosectarian, and the imbrication of both created the fragmentation

of Iraq since the US-led invasion and even more since the invasion of ISIS.

Even before these wars and occupations, the authoritarian Baath regime had normalized

violence and turned it into a particular sense of Iraqi political identity. From 1975, the

cultural identity and very existence of the four million Iraqi Kurds was under threat:

between 250,000 and 300,000 Kurds were deported from Kirkuk to the south in order to

“Arabize the population.” The Baath Party also undertook a campaign of “internal

population redistribution,” deporting thousands of Yazidis from Sulaymaniyah and Sinjar.

From the 1970s to the 1990s, the repression of both the Shi’a movement and the Kurdish

nationalist movement made the Baath regime one of the most violent dictatorship in the

world. Under the banners of Arab nationalism and the struggle against Iranian influence,

the regime undertook massive campaigns of repression. The war with Iran lasted more

than eight years and caused the deaths of many thousands of individuals, mostly male

soldiers. This is coupled with the Tasfirat politics in which hundreds of thousands of Iraqi

families deemed to be of Iranian origin were taken from their homes and expelled across

the Iranian borders.18

As a consequence of these atrocities, the regime’s gender rhetoric shifted radically

towards the reinforcement of normative conceptions of masculinity and femininity.19 The

rhetoric of the “good Iraqi man and woman, educating and participating in the labor

force” changed radically. During the 1980s, the state engaged in a glorification of

militarized masculinity and emphasized Iraqi women’s reproductive responsibilities.

Being a good Iraqi woman became synonymous with being the mother of future

soldiers.20 In several speeches, Saddam Hussein insisted that “a woman who does not

bring at least five children is a traitor to the nation.”21 The regime pressured women to

raise the fertility rate by banning contraception, making abortion illegal, and enhancing

maternity benefits, including free infant food. Men were pictured as battle-ready soldiers:

the protectors of the nation’s women and children. As national agency was masculinized

and the land was presented as female, gendered obligations were denoted in poems and

propaganda literature. In the war’s last stages, reproductive representations encouraged

Page 8 of 21

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: University of Arizona Library; date: 28 July 2018

The Fragmentation of Gender in Post-Invasion Iraq

an Islamic discourse, presenting women as “mothers”. Even children’s literature was

militarized and in it, Iranians dehumanized.22

The Baath regime’s discriminatory notion of Iraqiness was also very gendered in the

sense that it affected very concretely the legislation regarding who could marry whom

and how the ideal Iraqi family conducted its life.23 The regime implemented specific

legislation in the early 1980s to push mixed couples to divorce. Dima M., born in Baghdad

in 1955, was victim of the taba‘iyya campaign against Iraqis considered of Iranian

descent, and in 1980 her husband was jailed for leaving the war front. She recounted to

me how he was forced to “divorce her” in order to obtain his freedom, as the law

rewarded those who divorced “Iranian” Iraqis:

It was when Saddam was giving 2000 dinars to those who divorce a taba‘iyya

person. At the time, 2000 dinars was something huge. We earned around 100

dinars per month, so you can imagine how important this amount of money was.

Saddam tried to destroy families from the inside, pushing people to betray their

own families. My husband obtained his release after he divorced me. He was

released in 1984 and I saw him again for the first time in 1991.24

The years of the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait marked two of the most brutal episodes of state

violence against Iraq’s northern and southern populations in the history of Iraqi society.

Between 1988 and 1989, chemical attacks on Halabja—known as the al-Anfal campaign—

killed more than 180,000 Kurds, mostly civilians.25 The 1991 uprising of the Kurdish

nationalists in the north gained international attention, and in April 1991 Operation Safe

Haven was undertaken in the Kurdish region in order to protect the population from the

Baath army. The spontaneous uprising by communists, Shias, and disaffected regional

Baathists in southern Iraq, on the other hand, did not gain as much attention after the US

regime abandoned them. Saddam Hussein’s praetorian guards launched a merciless

attack on the insurgents. Hundreds of thousands were killed, tortured, imprisoned, and

declared missing. The memories of these atrocities represented a turning point in the

country’s sectarian relations and fueled the sectarian war of 2006–2007.26

The US-led coalition’s six-week bombing campaign in January–February 1991 destroyed

the functionality of the Iraqi economy and state. A UN special report from March 1991

indicated that after the bombing campaign, Iraq moved from a modern, highly urbanized,

and mechanized economy to a pre-industrial one.27 The UN’s imposition of drastic

economic sanctions perpetuated the war’s destruction of state infrastructure. Hardest hit

were the sectors on which women relied: the public services, and social, education, and

health systems. The regime in Baghdad responded by imposing austerity measures: it

reduced the number of government employees, demobilized thousands of military and

civilian personnel, and curbed women’s work in the public sector. It pushed the

population into a “survival economy” as people were forced to work several jobs, selling

personal belongings, and sewing their own clothes.28

Page 9 of 21

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: University of Arizona Library; date: 28 July 2018

The Fragmentation of Gender in Post-Invasion Iraq

The dismantling of the education system, public sector, and state services impacted

women’s everyday lives. The effects were especially felt by female teachers and public

employees, who saw their salaries plummet to such a degree that they could not even

afford to pay for weekly transport.29 Women could not work alternative jobs; men, on the

other hand, could work as engineers in the morning and as a taxi driver or shopkeepers

in the afternoon. This limited women’s financial contributions to the household, and

pushed many into domestic life. Iman A. was in her twenties at the time, employed in the

production sector, and married with two children. She spoke about the drop in her salary,

as well as the fact that most of her female friends quit their jobs. Iman A. also spoke

about how her sector managed to carry on despite the lack of staples:

The sanctions taught us a lot. How to face difficulties, how to be autonomous? I

decided to carry on working, although my salary was 6000 dinars (around 20

dollars), so almost nothing. It was not enough to buy the monthly bus ticket to go

to my place of work. I chose to carry on with my job despite the fact that all the

women around me were quitting their jobs, because it was a waste of time for

almost no salary. I did not work for the salary, I worked in order to have something

to do, to morally and psychologically handle the terrible situation of the 1990s.

Most of the women around me who quit their jobs ended up at home, they did not

find another job. It morally and psychologically destroyed so many women.30

More generally, women bore the burden of household survival, as many men were

involved in the military. Many women found alternative, informal ways to provide for their

family’s basic necessities, selling ready-made meals, personal objects, and homemade

sweets; giving tutorials for teachers; nursing; or cleaning.31

In the context of extreme poverty, new forms of patriarchy emerged that were marked by

conservatism and the idea that women “needed protection.”32 On the one hand, the

regime’s Faith Campaign espoused moral propriety of Iraqi women and, on the other,

women were forced to make degrading life-saving choices.33 Female and child

prostitution became rampant, men spent fortunes on pornography, kidnapping of girls for

ransom occurred, young women were forced into marriages with old wealthy men, all

practices that the PSC had sought to eradicate. Proportionate to this deterioration,

general poverty decimated the marriage rate. Informal unions—‘urfi marriages—and

temporary marriages—mut‘a for Shias, misyar for Sunnis filled the gap.34 More generally,

the spread of corruption, communal and neighborhood relations degenerated into

individualistic economic survival and mafia-type racketeering. This period restructured

the social and cultural fabric of Iraq, fundamentally altering the values of sociability and

morality.35

This sketch of political, economic, and military violence in Baath Iraq shows how much

these forms of violence are both gendered and carry ethnic and sectarian dimensions. It

is precisely the imbrication between gender, ethnicity, and sectarianism that is at the core

of the post-invasion condition of severe fragmentation of the country. Bearing this gloomy

Page 10 of 21

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: University of Arizona Library; date: 28 July 2018

The Fragmentation of Gender in Post-Invasion Iraq

reality in mind is essential when considering the resurgence of Islamic fundamentalism

since 2014.

Living and Mobilizing in an Occupied and

Fragmented Country

The invasion of Iraq, coupled with the bombing and fighting that occurred between

March and May 2003, led to around 150,000 civilian deaths.36 After the establishment of

the occupation through the CPA, and the establishment of Iraqi governing councils based

on communal quotas, Iraqis’ daily lives began to be characterized by violence. The

sectarian civil war that continues to haunt the country was the direct result of the CPA

de-Baathification campaign which decommissioned 400,000 Iraqi soldiers and lowly

Baath Party members undermining the state, the political marginalization of the Sunni

population and the establishment of communal identities as the basis of the Iraqi political

system.37 The US army’s repression of uprisings against the occupation—especially in

Fallujah—and the rise of political and party-associated militias benefiting from the power

vacuum, all took a sectarian shape.38 The exacerbation of sectarian conflict reached its

extreme during the 2006–2007 sectarian war.39 This civil war and all the associated

events represented the second turning point after 1991 in Iraqi sectarian relations, and

reorganized society and territory according to sectarian lines.40 Such a fracturing is

visible in the division of Baghdad into homogeneously Sunni and Shi’a neighborhoods,

each separated by checkpoints and concrete walls.41

The sectarian dimension of the social retribalization started under the Baath in the 1990s

was pushed even further in the chaos that followed the invasion. Sectarian violence is

gendered. Most of the women activists I interviewed, especially public and media figures,

have received death threats or been directly targeted by violence, including car bomb

attacks in front of their offices or homes. Some had to flee the country, but the majority

remain in Baghdad. Some moved into areas controlled by their sect, as their

neighborhoods were “cleansed” by sectarian militias. Ibtihal I., in her early forties, very

active women’s rights activist of the Iraqi Women’s League recounted to me how, in an

attempt to kill her in 2007, a group of men placed explosives in the front of her house,

and made it explode. The event occurred after she had received several death threats

from conservative Islamist militia groups in the form of phone calls and messages.

Fortunately, no one was in the house at the time. Ibtihal recalled the police incompetence

and lack of will to help her find the perpetrators of the attack and provide her with

protection. She described the atmosphere of Baghdad in 2006–2007 and her feelings

about it:

Page 11 of 21

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: University of Arizona Library; date: 28 July 2018

The Fragmentation of Gender in Post-Invasion Iraq

You know in 2006 and 2007, after 2 p.m., the streets of Baghdad were empty.

There was no life in Baghdad. The next day, everything opened at 8 a.m. But

people were scared to go out very early or later than 2 p.m. Violence was

everywhere. Armed groups, death threats, militias, the everyday reality was

terrible, frightful. Until today you know, the value of life is lost in Iraq. Any

disagreement between political leaders, ends up by violence in the streets. We

face death every single day, every Iraqi that goes out of his house is not certain

that he will come back alive. Iraq transformed into a scene of death. Even when

we have moments of joy, we feel that we are stealing these moments, and we then

refrain ourselves saying Allah yesterna [May God protect us]. The worse is that we

do not even have a state, a government towards whom we could seek for

protection or complain.42

In addition to the overall insecurity that led the deaths of many Iraqi women activists,

most of the women I interviewed noticed how the rise of conservative gender norms

impacted their dress and ability to move freely in specific neighborhoods of Baghdad. As

many neighborhoods are controled by militias and armed groups backed by conservative,

sectarian Islamist parties, many women have witnessed or experienced incidents

regarding clothes or behavior when crossing checkpoints. Christian women activists, too,

prefer to wear a loose shawl over their head when moving between the capital’s different

neighborhoods. Gender norms are imbricated with sectarian division: in Sunni-dominated

cities women often wear a jubbah consisting of a hijab and a long mantle while in Shia-

dominated cities, particularly in southern Iraq, women now wear a black ‘abayah43 over

their hijab and cover their feet with black socks. Many of the women I interviewed

described incidents such as the closing of hair salons or car bomb attacks to forbid

women from driving.

More generally, an overwhelming sense of tension has been created by the violence, and

the dominance of competing armed militias in the streets. This feeling was expressed

repeatedly to me: “Before we had one Saddam, today we have a Saddam at every street

corner.” Moreover, my ethnographic research showed that the militarization of the Iraqi

public spaces has turned Baghdad to a “city of men”: checkpoints, walls, and soldiers in

the streets everywhere. Many places are now inaccessible for women and some places

such as cafés, once the pride of riverside Baghdad are forbidden for women from five

p.m. even in al-Karrada neighborhood known for its openness.

In 2007, over half of the Iraqi population lived on less than one dollar a day. Acute

malnutrition has more than doubled since 2003, affecting no less than 43% of all children

between the ages of six months and five years. Almost 50% of all households have been

deprived of healthy sanitation facilities. There is a critical lack of medical drugs and

equipment, and more than 15,000 doctors have been killed, kidnapped, or fled the

country. Even in Baghdad, the state provides a maximum of five hours of electricity per

day.44 In addition, the lack of control and stability since 2003, as well as the privatization

and liberalization of the economy, has provoked a drastic increase in the price of staple

goods and basic necessities. As a result, the majority of Iraqis are poor while living in an

Page 12 of 21

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: University of Arizona Library; date: 28 July 2018

The Fragmentation of Gender in Post-Invasion Iraq

oil-rich country. No major plan or policies have been undertaken by the new regime to

deal with these issues. The new state’s weakness, its inability to provide security and

respond to basic needs such as access to running water, electricity, housing, and

employment, mismanagement and corruption pushed Iraqis to rely on alternative sources

of protection and service.45

Alongside mobilizations around women’s legal rights, women civil society activists were

at the forefront of the struggle for welfare and social protection laws, against corruption,

advocating freedom of expression, criticizing governmental salaries and “institutionalized

corruption.” Most of the independent women civil society activists I met participated in

the Civil Initiative to Preserve the Constitution, which was launched in 2010 to apply

pressure on the government, as well as mobilizations denouncing armed violence,

sectarianism, and state incompetence in providing basic public services. The IWN took a

strong stand with regard to Iraq’s independence from foreign interference; it supported

federalism and denounced human rights abuses in Iraq.46 Activists also raised the issue of

the disappeared and prisoners of the anti-terrorism campaign, who are still detained

without judgment, as well as the police and security forces’ use of violence.47

The situation is so chaotic and fragmented that even female parliamentarians face

considerable challenges that makes their work on the ground almost impossible. Betoul

M.—a prominent Shi’a Islamist activist—believes the sectarian quota system is the root of

state and government dysfunction. She represented Tayar al-Islah, a Shi'a political group

founded by Ibrahim al-Ja‘fari, at the Baghdad Provincial Council and faced much

difficulty:

Page 13 of 21

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: University of Arizona Library; date: 28 July 2018

The Fragmentation of Gender in Post-Invasion Iraq

We face a lot of problems at the Baghdad Provincial Council. The greater problem,

in reality, is the communal quota system. […] I had to struggle to get the

Committee of Civil Society Organizations, because I felt that as a civil society and

women’s activist, it was my place to be on this committee. But once I joined this

committee, I faced a lot of conflicts with the head of the committee. This man,

once he became the head of a committee, he thought he became the King of

Baghdad. We are both elected representatives; he has his position and I have

mine. I proposed him to divide Baghdad into different zones in order to operate

more efficiently. He imposed the areas where he wanted to work, and he refused

to work on certain areas. Let’s be honest here, the problem is sectarianism. He

told me: “You take al-Sadr, al-Kazmyah, al-Istiqlal, al-Kerrada and Tesa’ Nisan etc.

[all Shia areas] and I take Abu Ghraib, Tarmyah, Mayadeen and al-A‘dhamyah etc.

[all Sunni areas].” I finally told him that I agreed, because I cannot go to these

places with my ID card and my ‘abayah. The ‘abayah is the most visible sign, as

you know. And at the time, after 2005, it was dangerous. But even today, I do not

know these areas or trust going there. Anyway, I cannot access these areas. […]

Before the fall, didn’t we live all together, Sunnis and Shi'as, all neighbors?

[…]However, in the context where the state is so weak, when people are in such

need, it is normal that the citizen turns to its representatives to complain, or even

hurt them sometimes. […] It is easier now to work and ask for funds from NGOs

than the government. If I want to deal with basic services in a neighborhood, it is

easier for me to ask for funding from an NGO than from the government, because

of corruption the administrative process and control makes it take years to obtain

anything. It will be so complicated and so long, and I need to fix some very urgent

problems. It is a pragmatic approach. We have so many emergency issues: water,

electricity and basic needs. We cannot wait until the government builds social

housing, we have to find concrete solutions.48

In a context characterized by violence and a weak state, where individuals are pushed to

rely on alternative sources of protection and security, tribal leadership gained

significance and took a sectarian shape. It is not surprising, therefore, that a large

number of tribesmen and political leaders chose to join ISIS in June 2014, during its

capture of Mosul. In response to the invasion of ISIS, Grand Ayatollah Sistani—the most

important marja‘ in Iraq—called for a “jihad to preserve Iraq,” which incited thousands of

civilians mainly Shi’as to join the military operations against ISIS.

More recently in the context of the invasion of ISIS, ordinary citizens, civil society, and

women’s rights activists launched a strong grassroots movement that started last summer

(2015). From Baghdad’s Tahrir Square across Iraq, this movement has expressed citizens’

general exasperation at the corruption and mismanagement of the post-2003

government; corruption and mismanagement epitomized by electricity cuts and a lack of

public services. These protests quickly turned into a massive popular movement—

supported even by the prominent religious figure Ayatollah Sistani—vilifying Iraq’s post-

invasion regime and demanding radical reforms. Every Friday since, demonstrators have

gathered in the main public squares of Iraq’s big cities including Najaf, Nasrya, Basra,

Page 14 of 21

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: University of Arizona Library; date: 28 July 2018

The Fragmentation of Gender in Post-Invasion Iraq

and echoed the slogans of the protestors in central Baghdad: “Bi-ism il-din bagunah al-

haramiyya” (“in the name of religion we have been robbed by looters”) and “Khubz,

Huriyya, Dawla Medeniya” (“Bread, Freedom, and a Civil State”). Demonstrators consider

the new regime’s corruption and sectarian politics as directly responsible for the

formation and spread of ISIS.

The Shi'a Islamist Sadrist movement joined the protest, as its leader Moqtada al-Sadr met

the sit-in—that started on March 18, 2016—in front of the concrete T-walls that

encompass the Green Zone in the capital, where the main central government building,

foreign embassies, and Iraq’s new political leadership all reside. If many civil society and

women’s rights activists are critical of the involvement and possible hijacking of the

popular movement by the Sadrist, others were far more nuanced. Henaa Edwar, head of

the Al-Amel organization and a prominent figure of the IWN was very hopeful regarding

the developments of the popular protests when I met her in the Al-Amel offices in al-

Kerrada, central Baghdad, the day she visited the sit-ins with a delegation of IWN

activists on March 22, 2016. Despite remaining critical of the Sadrists’ populism and

conservatism, especially regarding gender matters, Edwar expressed her support for the

protesters and a positive view of the Sadrists’ involvement. She believes that Moqtada al-

Sadr’s presence pushed the Sadrists’ wide grassroots proletarian base onto the streets in

a show of unified nationhood and citizenship, especially at a stage when after weeks of

mobilizations, some protesters, tired of being in the streets every Friday, were starting to

go home. Many women’s rights activists who participated actively in this movement of

protest emphasized the importance of linking gender equality advocacy with the

struggles for religious and class equality. The IWN activists insist on the preservation of

equal citizenship for Iraqis from all ethnic and religious backgrounds as a cornerstone of

the preservation of women’s legal rights.

Conclusion

As eloquently shown by Al-Ali and Pratt,49 the neocolonial use of women’s rights rhetoric

to justify imperialist and geopolitical agendas is well known in Iraq. The reality of Iraq

today shows that there is a great contradiction between the US government’s advocacy of

women’s rights and its actual neocolonial and neoliberal politics. The ethnosectarian form

of government the US occupation force ordained has resulted in generalized violence and

a fragmented citizenship. In the context of the ISIS invasion and the terrible violence it

unleashed, this discourse justifying military actions in order to “save women” has been

used again not only by political leaders in the West, especially the US administration, but

also very strongly by the Iraqi political leadership. The new regime describes ISIS as the

“main enemy” of Iraq and the Shi'a-dominated central government intensifies its

sectarian discourse legitimizing military violence and arbitrary executions in the name of

“security.” Since 2014, the central government has launched a huge media campaign

showing video clips more than ten times a day on Iraqi TV in which male Iraqi soldiers kill

Page 15 of 21

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: University of Arizona Library; date: 28 July 2018

The Fragmentation of Gender in Post-Invasion Iraq

a “terrorist.” They celebrate both a violent model of masculinity and an exclusive

definition of nationhood in which the figure of the Sunni tribesman is depicted as either

an ISIS supporter or a former Baathist.

As demonstrated in this chapter, militarization and political violence that started under

the Baath regime are the central factor of everyday gender-based violence and in Iraq

today, the entanglement of gender and ethnosectarian enmity create a highly fragmented

reality. The very basis of the early republic’s women’s legal rights are delegitimized by

the central government dominated by conservative Shi’a Islamists which either seeks a

sectarianization of the PSC. Meanwhile in the areas occupied by ISIS, women are deemed

minors or inferiors. It is clear that the situation women are facing in Iraq today is not the

simple product of a misreading of “Islam,” but it is rather the direct consequences of a

series of wars and invasions that have led to social and political fragmentation coupled

with the rise of conservative forces, the foremost victims of which have been Iraqi

women.

And still, Iraqi women’s rights and civil society activists have rallied in Tahrir Square

every Friday since the summer of 2016 and insisted that only an inclusive, socially,

religiously, and ethnically egalitarian society could bring about an environment in which

Iraq can rebuild itself. The US-led invasion and occupation exacerbated the

ethnosectarian divisions as well as the social and economic crisis that characterized Iraq

since at least 1991. As Iraqi women and men demonstrators articulate very clearly, ISIS is

the product of sectarian oppression and corruption of this new regime produced by the

imperialist US-led invasion and occupation.

Zahra Ali

Rutgers University, Newark.

References

Abu-Lughod, Lila (2013). Do Muslim Women Need Saving? (Cambridge, MA/London:

Harvard University Press).

Abu-Lughod, Lila (ed) (1998). Remaking Women: Feminism and modernity in the Middle

East (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press).

Ahmed, Leila (1992). Women and Gender in Islam. Historical roots of a modern debate

(New Haven/London: Yale University Press).

Ahmed, Leila (1982). “Feminism and Feminist Movements in the Middle East, a

preliminary exploration: Turkey, Egypt, Algeria, People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen,”

Women’s Studies International Forum 5, 2: 153–168.

Al-Ali, Nadje (2007). Iraqi Women. Untold Stories from 1948 to the Present (London/New

York: Zed Books).

Page 16 of 21

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: University of Arizona Library; date: 28 July 2018

The Fragmentation of Gender in Post-Invasion Iraq

Al-Ali, Nadje and Pratt, Nicola (2009). What kind of liberation? Women and the

occupation of Iraq (Berkeley: University of California Press).

Al-Jawaheri, H. Yasmine (2008). Women in Iraq. The Gender Impact of International

Sanctions (London: I. B. Tauris).

Ali, Zahra (forthcoming). Women and Gender in Iraq: between Nation-building and

Fragmentation (Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press).

Arato, Andrew (2009). Constitution Making Under Occupation. The Politics of Imposed

Revolution in Iraq (New York/Chichester: Columbia University Press).

Bint al-Rafidain/UNIFEM (2006). ﺩﺭﺍﺳﺔ ﻗﺎﻧﻮﻧﻴﺔ ﻟﻮﺍﻗﻊ ﺍﻻﺧﻮﺍﻝ ﺍﻟﺸﺨﺼﻴﺔ ﻓﻲ ﻣﻨﺎﻃﻖ ﺍﻟﻔﺮﺍﺕ ﺍﻷﻭﺳﻂBabel/

Kerbala/Najaf/Diwanyah/Waset.

Bozarslan, Hamit (2009). Conflit kurde (Paris: Autrement).

Bozarslan, Hamit (2008). Une histoire de la violence au Moyen-Orient. De la fin de

l’Empire ottoman à Al-Qaida (Paris: La Découverte).

Charrad, M. Mounira (2011). “Central and Local Patrimonialism: State-Building in Kin-

Based Societies,” ANNALS, AAPSS 636, July 2011: 49–68.

Charrad, M. Mounira (2001). States and Women’s Rights: The Making of Postcolonial

Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco (Berkeley: University of California Press).

Damluji, Mona (2010). “Securing democracy in Iraq: Sectarian politics and segregation in

Baghdad, 2003–2007,” Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review 21, 2: 71–87.

Dawisha, Adeed (2009). Iraq: A political history from independence to occupation

(Princeton, NJ: Princeton).

Dodge, Toby (2013). Iraq—from war to a new authoritarianism, Adelphi series (London:

Routledge Taylor and Francis).

Dodge, Toby (2005). Iraq’s future: the aftermath of regime change. Adelphi Papers, 372.

(Abingdon: Routledge for the International Institute for Strategic Studies).

Efrati, Noga (2012). Women in Iraq. Past meets Present (New York: Columbia University

Press).

Efrati, Noga (2005). “Negotiating rights in Iraq: Women and the Personal Statuts Law,”

Middle East Journal 59, 4: 575–595.

Efrati, Noga (1999). “Productive or Reproductive? The Roles of Iraqi Women during the

Iraq–Iran War,” Middle Eastern Studies 35, 2: 27–44.

Haddad, Fanar (2014). “A Sectarian Awakening: Reinventing Sunni Identity in Iraq After

2003,” Current Trends in Islamist Ideology 14: 70.

Page 17 of 21

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: University of Arizona Library; date: 28 July 2018

The Fragmentation of Gender in Post-Invasion Iraq

Haddad, Fanar (2010). Sectarian Relations in Arab Iraq: Competing Mythologies of

History, People and State. Thesis submitted to University of Exeter for a DPhil in

Research in Arab and Islamic Studies, March 2010.

Ismael, Tareq Y. and Ismael, Jacqueline S. (2015). Iraq in the Twenty-First Century.

Regime Change and the Making of a Failed State (London & New York: Routledge).

Ismael, Jacqueline S. and Ismael Shereen T. (2000). “Gender and State in Iraq,” in Suad

Joseph (ed.) Gender and Citizenship in the Middle East (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse

University Press) pp. 185–213.

Ismael, Jacqueline S. and Ismael, Shereen T. (2008). “Living through war, sanctions and

occupation: the voices of Iraqi women,” International Journal of Contemporary Iraqi

Studies 2, 3: 409–424.

Joseph, Suad (ed.) (2000). Gender and Citizenship in the Middle East (Syracuse, NY:

Syracuse University Press).

Joseph, Suad (1991). “Elite Strategies for State Building: Women, Family, Religion and the

State in Iraq and Lebanon,” in Deniz Kandiyoti (ed.). Women, Islam, and the State

(London: Macmillan Press) pp. 176–200.

Kandiyoti, Deniz (ed.) (1996). Gendering the Middle East (London/New York: I. B. Tauris).

Kandiyoti, Deniz (1991). Women, Islam and the State (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University

Press).

Kern, Karen (2011). Imperial Citizen: Marriage and Citizenship in the Ottoman Frontier

Provinces of Iraq (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press).

Khoury, R. Dina (2013). Iraq in Wartime. Soldiering, Martyrdom, and Remembrance

(Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press).

Kutschera, Chris (2005). Le Livre Noir de Saddam Hussein (Paris: Oh editions).

Mohanty, T. Chandra (2003). Feminism without border. Decolonizing Theory, Practicing

Solidarity (Durham, NC/London: Duke University Press).

Mohanty, T. Chandra (1988). “Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial

Discourses,” Feminist Review 30: 61–88.

Pieri, Caecilia (2014). “Can T-Wall Murals Really Beautify the Fragmented Baghdad,”

Jadaliyya 18 mai 2014 http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/17704/can-t-wall-

murals-really-beautify-the-fragmented-b (last access december 4 2016).

Rohde, Achim (2010). “Gender Policies in Baathist Iraq,” in State-Society Relations in

Baathist Iraq (London/New York: SOAS Routledge Studies on the Middle East) pp. 75–

118.

Page 18 of 21

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: University of Arizona Library; date: 28 July 2018

The Fragmentation of Gender in Post-Invasion Iraq

Rohde, Achim (2006). “Opportunities for Masculinity and Love: Cultural Production in

Baathist Iraq during the 1980s,” in Ouzgane Lahoucine (ed). Islamic Masculinities

(London/New York: Zed Books).

Zubaida, Sami (2011). Beyond Islam: a new understanding of the Middle East (London/

New York: I. B. Tauris).

Zubaida, Sami (1989). Islam, the people and the state (London: Routledge).

Notes:

(1) See for example Abu-Lughod (2013, 1998); Kandiyoti (1996, 1991); Joseph (2000);

Ahmed, (1992, 1982); Mohanty (2003; 1988).

(2) See for example Zubaida (2011, 1989).

(3) I have conducted an indepth fieldwork mainly in Baghdad, and in Erbil and

Sulaymaniyah in Iraqi Kurdistan between October 2010 and June 2012. Throughout this

ethnography of women’s political activism in Iraq I conducted eighty semi-structured

interviews (most of them consisting in life-stories) of Iraqi women political activists from

across the political, ethnic and religious spectrum—leftists, secular, Islamists, Arabs,

Kurds, Christians, Sunnis, Shi’as etc. and have been a participant observer of Iraqi

women’s political mobilizations and gatherings. I have also conducted fieldwork among

women and civil society groups in Baghdad, Najaf-Koufa, Karbala an Nasriyah in March-

April 2016 and May 2017.

(4) For the studies on pre-republican legal frameworks for women, see Kern (2011) and

Noga Efrati (2012).

(5) Charrad (2011; 2001).

(6) That will become few years later the Iraqi Women’s League.

(7) Straight after the first Baath coup in 1963, this measure was abolished.

(8) Efrati (2005; 2012).

(9) Joseph (1991).

(10) Joseph (1991); Ismael J. and Ismael S. (2000).

(11) Efrati (1999) and Rohde (2010).

(12) Al-Jawaheri (2008); Al-Ali (2007); Ali (forthcoming).

(13) Al-Jawaheri (2008).

(14) Al-Jawaheri (2008); Efrati (2005).

Page 19 of 21

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: University of Arizona Library; date: 28 July 2018

The Fragmentation of Gender in Post-Invasion Iraq

(15) Bint al-Rafidain/UNIFEM (2006).

(16) Al-hewar al-mutamaden, March 2, 2014.

(17) Khoury (2013).

(18) Kutschera (2005); Bozarslan (2009; 2008).

(19) Khoury (2013), Rohde (2010; 2006).

(20) Al-Ali (2007), Efrati (1999).

(21) Rohde (2010).

(22) Khoury (2013), Rohde (2010).

(23) Ali (forthcoming).

(24) Interview conducted in Baghdad in 2012.

(25) Kutschera (2005); Bozarslan (2009; 2008).

(26) Haddad (2014; 2010).

(27) Ahtissaari, M, “Report to the Secretary-General on Humanitarian Needs in Kuwait

and Iraq in the Immediate Post-Crisis Environment”, New York, UN Report no. S122366,

March 1991.

(28) Al-Jawaheri (2008).

(29) Al-Jawaheri (2008); Ali (forthcoming).

(30) Interview conducted in Baghdad in 2010.

(31) Ismael J. and Ismael S (2008).

(32) Al-Ali (2007); Al-Jawaheri (2008); Ali (forthcoming).

(33) Al-Ali (2007); Rohde (2010).

(34) Rohde (2010); Ali (forthcoming).

(35) Al-Ali (2007); Al-Jawaheri (2008).

(36) Estimated according to the Lancet (2004), Iraq Body Count: www.iraqbodycount.org,

(last access February 3 2017) and Iraq: the Human Cost: http://web.mit.edu/

humancostiraq/ (last access February 3 2017).

(37) Ismael Y. and Ismael S. (2015); Arato (2009); Dodge (2005, 2013).

(38) Dodge (2013).

Page 20 of 21

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: University of Arizona Library; date: 28 July 2018

The Fragmentation of Gender in Post-Invasion Iraq

(39) Between 2006 and 2007, the sectarian civil war claimed at least 1,000 lives per week,

mostly civilian, and both internally and externally displaced around 2,500,000 according

to the UNHCR.

(40) Haddad (2014; 2010).

(41) Damluji (2010); Pieri (2014).

(42) Interview conducted in Baghdad in 2011.

(43) Long and large black tissue covering the whole body excluding the face.

(44) Dawisha (2009).

(45) Dawisha (2009).

(46) Ali (forthcoming).

(47) Ali (forthcoming).

(48) Interview conducted in Baghdad in 2010.

(49) Al-Ali and Pratt (2009).

Zahra Ali

Rutgers University, Newark.

Page 21 of 21

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: University of Arizona Library; date: 28 July 2018

You might also like

- After Jihad: America and the Struggle for Islamic DemocracyFrom EverandAfter Jihad: America and the Struggle for Islamic DemocracyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (5)

- Muslim Women's Quest For Equality Between Islamic Law and Feminism - Ziba Mir Hosseini - ChicagoDocument18 pagesMuslim Women's Quest For Equality Between Islamic Law and Feminism - Ziba Mir Hosseini - Chicagooohdeem oohdeemNo ratings yet

- Islam in Iran and WomenDocument18 pagesIslam in Iran and WomenYasmiin MansooriNo ratings yet

- Muslim Women S Quest For EqualityDocument18 pagesMuslim Women S Quest For EqualityFer MaríaNo ratings yet

- Hodood OrdananceDocument23 pagesHodood OrdananceAsghar Mohammad Khan HotiNo ratings yet

- Civil Society in IranDocument20 pagesCivil Society in IranMoghset KamalNo ratings yet

- University of Arkansas Press Philosophical TopicsDocument21 pagesUniversity of Arkansas Press Philosophical TopicsFaizan HaiderNo ratings yet

- Copyright 2005 Northwestern University School of LawDocument52 pagesCopyright 2005 Northwestern University School of LawrehmathazaraNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Womens Rights in IranDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Womens Rights in Iranxcjfderif100% (1)

- Law of Desire: Temporary Marriage in Shi’i Iran, Revised EditionFrom EverandLaw of Desire: Temporary Marriage in Shi’i Iran, Revised EditionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Reclaiming The Nation Muslim Women and TDocument12 pagesReclaiming The Nation Muslim Women and TYashica HargunaniNo ratings yet

- American OrientalismDocument19 pagesAmerican OrientalismElHabibLouaiNo ratings yet

- Daughters of The Nile - The Evolutionof Feminism in EgyptDocument29 pagesDaughters of The Nile - The Evolutionof Feminism in EgyptLara BelalNo ratings yet

- Attack On Human RightsDocument16 pagesAttack On Human RightsjazzeryNo ratings yet

- HOLOCAUST OF IRAQ: A Theory about the Crimes of the Members of Agent Parties in IraqFrom EverandHOLOCAUST OF IRAQ: A Theory about the Crimes of the Members of Agent Parties in IraqNo ratings yet

- Islam and Women's Sexuality Report From Turkey by Pinar IlkkaracanDocument11 pagesIslam and Women's Sexuality Report From Turkey by Pinar IlkkaracanLCLibraryNo ratings yet

- Research Paper - Feminist Movement & Legal Framework in Pakistan by Arshad Hussain Siddiqui - 2021Document17 pagesResearch Paper - Feminist Movement & Legal Framework in Pakistan by Arshad Hussain Siddiqui - 2021Qazi ArshadNo ratings yet

- 1 Genesis of The "Woman Question"Document33 pages1 Genesis of The "Woman Question"Istebreq YehyaNo ratings yet

- Islam and Gender: The Religious Debate in Contemporary IranFrom EverandIslam and Gender: The Religious Debate in Contemporary IranRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (5)

- Women and Constitutional Debate in SomaliaDocument27 pagesWomen and Constitutional Debate in SomaliaDr. Abdurahman M. Abdullahi ( baadiyow)100% (1)

- Triple Talaq Bill in India Muslim WomenDocument9 pagesTriple Talaq Bill in India Muslim WomenShaiq ShabbirNo ratings yet

- 2 Bayat 2013 - CH 1 Post-Islamism at LargeDocument41 pages2 Bayat 2013 - CH 1 Post-Islamism at LargeRobie KholilurrahmanNo ratings yet

- Triple Talaq Bill in India: Muslim Women As Political Subjects or Victims?Document8 pagesTriple Talaq Bill in India: Muslim Women As Political Subjects or Victims?sugandhaNo ratings yet

- Inconsistencies in Constitution Rights Iraqi Constitution As A Case StudyDocument6 pagesInconsistencies in Constitution Rights Iraqi Constitution As A Case StudyPoonam KilaniyaNo ratings yet

- History Matters: Past As Prologue in Building Democracy in Iraq - Eric DavisDocument16 pagesHistory Matters: Past As Prologue in Building Democracy in Iraq - Eric DavisSamir Al-HamedNo ratings yet

- Of Marriage, Divorce and CrimiDocument26 pagesOf Marriage, Divorce and Crimiadvocate.karimaNo ratings yet

- ME Pol F09 SyllabusDocument13 pagesME Pol F09 SyllabusCailingNo ratings yet

- Broken Taboos in Post-Election Iran - Middle East Research and Information ProjectDocument3 pagesBroken Taboos in Post-Election Iran - Middle East Research and Information ProjectAnkitaSanyalNo ratings yet

- Turkey: The I Slamist-Secularist Divide.Document10 pagesTurkey: The I Slamist-Secularist Divide.Institute for the Study of Secularism in Society and Culture100% (2)

- IraqDocument35 pagesIraqi9495176No ratings yet

- Moudawana - HAWWADocument25 pagesMoudawana - HAWWAMardhiah ZawawiNo ratings yet

- Legal Injustices - The Zina Hudood OrdinanceDocument24 pagesLegal Injustices - The Zina Hudood OrdinanceShabana SajjadNo ratings yet

- "Muslim Women's Rights PDFDocument46 pages"Muslim Women's Rights PDFMuhammad Naeem Virk100% (1)

- Review Islamic Law and Gender Equality - 222 LibreDocument12 pagesReview Islamic Law and Gender Equality - 222 Librerahmattemitope18No ratings yet

- Pakistan: Status of Women & The Women's MovementDocument4 pagesPakistan: Status of Women & The Women's MovementmainbroNo ratings yet

- Hruger,+campbell 2021Document18 pagesHruger,+campbell 2021panorma view 360 viewNo ratings yet

- Religion Revisited Lecture Kandiyoti June2009Document7 pagesReligion Revisited Lecture Kandiyoti June2009Lou JukićNo ratings yet

- Feminism in PakistanDocument7 pagesFeminism in Pakistananum ijazNo ratings yet

- 10.18574 Nyu 9780814773031.003.0003Document26 pages10.18574 Nyu 9780814773031.003.0003Alfi SyahriyatiNo ratings yet

- Feminism and Modern Islamic Politics The Fact andDocument16 pagesFeminism and Modern Islamic Politics The Fact andtimiwg14No ratings yet

- Gender View in Transitional Justice IraqDocument21 pagesGender View in Transitional Justice IraqMohamed SamiNo ratings yet

- Women's Rights in The Middle East: Lahlou 1Document8 pagesWomen's Rights in The Middle East: Lahlou 1Anonymous xLiOTudUPtNo ratings yet

- The Myth of Middle East Exceptionalism: Unfinished Social MovementsFrom EverandThe Myth of Middle East Exceptionalism: Unfinished Social MovementsNo ratings yet

- Ci Feminism Iran Se RPDocument13 pagesCi Feminism Iran Se RPtuguimadaNo ratings yet

- Law, Authority Uthority, and Gender in P, and Gender in Post-Revolutionar Olutionary IranDocument55 pagesLaw, Authority Uthority, and Gender in P, and Gender in Post-Revolutionar Olutionary IranSamsun GalaxNo ratings yet

- Hassim Shireen Decolonising EqualityDocument18 pagesHassim Shireen Decolonising EqualityNabeelahNo ratings yet

- Kandiyoti. Women, Islam and The StateDocument8 pagesKandiyoti. Women, Islam and The StateArticulación ProvincialNo ratings yet

- Home AssignmentDocument10 pagesHome AssignmentAnkur Protim MahantaNo ratings yet

- A Revolution Under AttackDocument4 pagesA Revolution Under AttackNikos PapadakisNo ratings yet

- Algerian WomenDocument17 pagesAlgerian WomenStudij2011No ratings yet

- Social Difference Online Vol.1 2011Document86 pagesSocial Difference Online Vol.1 2011Man JianNo ratings yet

- The Struggle For Women Rights: A Study of Emergence of Feminism in Pakistan, (1947 To 2010)Document11 pagesThe Struggle For Women Rights: A Study of Emergence of Feminism in Pakistan, (1947 To 2010)Abdul AzizNo ratings yet

- The Past Present and Future of Feminist Activism in Pakistan - HeraldDocument31 pagesThe Past Present and Future of Feminist Activism in Pakistan - HeraldAhmadNo ratings yet

- LynchinDocument11 pagesLynchinwaheed tariqNo ratings yet

- Feminist JurisprudenceDocument7 pagesFeminist JurisprudenceParth TiwariNo ratings yet

- Feminist JurisprudenceDocument7 pagesFeminist JurisprudenceParth TiwariNo ratings yet

- Legalization of Prostitution in India: An Open Access Journal From The Law Brigade (Publishing) GroupDocument13 pagesLegalization of Prostitution in India: An Open Access Journal From The Law Brigade (Publishing) GroupPrashant SharmaNo ratings yet

- Rubina Decades of DisasterDocument3 pagesRubina Decades of DisasterHaseeb HassanNo ratings yet

- Women'S Right: HistoryDocument4 pagesWomen'S Right: HistoryRabeya KhawajaNo ratings yet

- IS-LM ModelDocument31 pagesIS-LM ModelAbdoukadirr SambouNo ratings yet

- Research Methods For Business Students: 8 EditionDocument19 pagesResearch Methods For Business Students: 8 EditionAbdoukadirr SambouNo ratings yet

- Overheated Economy and SolutionsDocument13 pagesOverheated Economy and SolutionsAbdoukadirr SambouNo ratings yet

- Lect 2 - POLS304 - 19.03.21-BDocument5 pagesLect 2 - POLS304 - 19.03.21-BAbdoukadirr SambouNo ratings yet

- Recovering For A Recession and Some Possible ProblemsDocument10 pagesRecovering For A Recession and Some Possible ProblemsAbdoukadirr SambouNo ratings yet

- Com351-Mbeg203-Nmj206-Research Methods - 2020-2021-Spring-SyllabusDocument1 pageCom351-Mbeg203-Nmj206-Research Methods - 2020-2021-Spring-SyllabusAbdoukadirr SambouNo ratings yet

- Lect 6Document16 pagesLect 6Abdoukadirr SambouNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomic Policy Instruments - IDocument35 pagesMacroeconomic Policy Instruments - IAbdoukadirr SambouNo ratings yet

- Balance of Payments (Bop)Document37 pagesBalance of Payments (Bop)Abdoukadirr SambouNo ratings yet

- POLS 417 Lect 1Document15 pagesPOLS 417 Lect 1Abdoukadirr SambouNo ratings yet

- GDP With Chain Weighted MethodDocument15 pagesGDP With Chain Weighted MethodAbdoukadirr SambouNo ratings yet

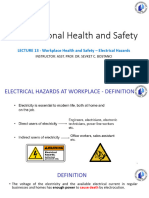

- Week 11 - Lecture 13 - Workplace Health and Safety - Electrical HazardsDocument41 pagesWeek 11 - Lecture 13 - Workplace Health and Safety - Electrical HazardsAbdoukadirr SambouNo ratings yet

- IntroductionDocument52 pagesIntroductionAbdoukadirr SambouNo ratings yet

- Lect 5Document4 pagesLect 5Abdoukadirr SambouNo ratings yet

- Political Structure Lecture 3Document17 pagesPolitical Structure Lecture 3Abdoukadirr SambouNo ratings yet

- Political Structure Lecture 8Document22 pagesPolitical Structure Lecture 8Abdoukadirr SambouNo ratings yet

- POLS 417 Lect 11Document13 pagesPOLS 417 Lect 11Abdoukadirr SambouNo ratings yet

- Political Structure Lecture 2Document16 pagesPolitical Structure Lecture 2Abdoukadirr SambouNo ratings yet

- Political Structure Lecture 6Document19 pagesPolitical Structure Lecture 6Abdoukadirr SambouNo ratings yet

- POLS 409 Lect 5Document8 pagesPOLS 409 Lect 5Abdoukadirr SambouNo ratings yet