Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Antibiótico

Uploaded by

Iago RamirezCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Antibiótico

Uploaded by

Iago RamirezCopyright:

Available Formats

110 Alan E.

Gross et al

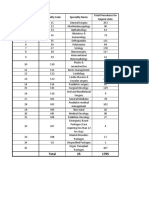

Table 1. Multivariate Poisson Regression Analysis of the Association Between content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/publications/healthy-living/

Healthcare Worker Influenza Immunization Rates and Hospital Acquired canadian-immunization-guide-statement-seasonal-influenza-vaccine-2019-

Influenza in Patients 2020/NACI_Stmt_on_Seasonal_Influenza_Vaccine_2019-2020_v12.

3_EN.pdf. Published 2019. Accessed January 20, 2020.

HCW Influenza Immunization Rate, % IRR 95% CI P Value

2. Grohskopf LA, Alyanak E, Broder KR, Walter EB, Fry AM, Jernigan DB.

≥65 1.09 0.77–1.54 .64 Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommenda-

≥70 0.72 0.47–1.11 .14 tions of the advisory committee on immunization practices—United States,

2019–20 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep 2019;68(No. RR-3):

≥75 0.65 0.39–1.08 .09 1–21.

≥80 0.28 0.089–0.89 .03 3. Carman WF, Elder AG, Wallace LA, et al. Effects of influenza vaccination of

health-care workers on mortality of elderly people in long-term care: a

Note. HCW, healthcare worker; IRR, incidence rate ratio; CI, confidence interval.

randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2000;355:93–97.

4. Potter J, Stott DJ, Roberts MA, et al. Influenza vaccination of healthcare

workers in long-term care hospitals reduces the mortality of elderly patients.

Our study suggests that acute-care hospitals must target influ- J Infect Dis 1997;175:1–6.

enza immunization rates >75% to see appreciable reductions in 5. Lemaitre M, Meret T, Rothan-Tondeur M, et al. Effect of influenza vacci-

HAI. In the context of a COVID-19 pandemic, it will be even more nation of nursing home staff on mortality of residents: a cluster-randomized

important for hospitals to augment their immunization programs trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:1580–1586.

beyond educational initiatives to achieve this minimum threshold. 6. Shugarman LR, Hales C, Setodji CM, Bardenheier B, Lynn J. The influence

of staff and resident immunization rates on influenza-like illness outbreaks

Acknowledgments. We thank members of Occupational Health and Safety at in nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2006;7:562–567.

both participating hospitals, for their support in data collection of healthcare 7. Salgado CD, Giannetta ET, Hayden FG, Farr BM. Preventing nosocomial

worker influenza immunization rates. influenza by improving the vaccine acceptance rate of clinicians. Infect

Control Hosp Epidemiol 2004;25:923–928.

Financial support. No financial support was provided relevant to this article. 8. van den Dool C, Bonten MJ, Hak E, Wallinga J. Modeling the effects of influ-

enza vaccination of health care workers in hospital departments. Vaccine

Conflicts of interest. All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this

2009;27:6261–6267.

article.

9. Frenzel E, Chemaly RF, Ariza-Heredia E, et al. Association of increased

influenza vaccination in health care workers with a reduction in nosoco-

References mial influenza infections in cancer patients. Am J Infect Control

1. An Advisory Committee Statement (ACS) National Advisory Committee 2016;44:1016–1021.

on Immunization (NACI) Canadian Immunization Guide Chapter on 10. Pitts SI, Maruthur NM, Millar KR, Perl TM, Segal J. A systematic review of

Influenza and Statement on Seasonal Influenza Vaccine for 2019–2020. mandatory influenza vaccination in healthcare personnel. Am J Prev Med

Public Health Agency of Canada website. https://www.canada.ca/ 2014;47:330–340.

Serious antibiotic-related adverse effects following unnecessary

dental prophylaxis in the United States

Alan E. Gross PharmD, BCPS, BCIDP, FCCP1,2 , Katie J. Suda PharmD, MS, FCCP3,4, Jifang Zhou MD, MPH, PhD5,

Gregory S. Calip PharmD, MPH, PhD6, Susan A. Rowan DDS, MS7, Ronald C. Hershow MD8, Rose Perez BS9,

Charlesnika T. Evans MPH, PhD10,11 and Jessina C. McGregor PhD12

1

Department of Pharmacy Practice, College of Pharmacy, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, United States, 2Pharmacy Services, University of

Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System, Chicago, Illinois, United States, 3Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion, Veterans’ Affairs Pittsburgh

Health Care System, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States, 4University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States, 5School of

International Pharmaceutical Business, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China, 6Department of Pharmacy Systems, Outcomes and Policy,

College of Pharmacy, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, United States, 7Department of Restorative Dentistry, College of Dentistry, University of

Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, United States, 8School of Public Health, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, United States, 9College of Medicine,

University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, United States, 10Department of Preventive Medicine, Institute for Public Health and Medicine, Northwestern

University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois, United States, 11Center of Innovation for Complex Chronic Healthcare, Edward Hines, Jr VA Hospital,

Hines, Illinois, United States and 12College of Pharmacy, Oregon State University, Portland, Oregon, United States

Dentists prescribe 10% of outpatient antibiotics; a significant por-

tion of these are for infection prophylaxis following dental proce-

dures.1,2 Current guidelines primarily recommend antibiotic

Author for correspondence: Katie J. Suda, E-mail: ksuda@pitt.edu

PREVIOUS PRESENTATION. These data were presented in part as the SHEA featured

prophylaxis prior to dental procedures that manipulate the gingi-

oral abstract # 1895 Presentation date, October 4, 2019, in Washington, DC. val tissue or the periapical region of teeth or that perforate the oral

Cite this article: Gross AE, et al. (2021). Serious antibiotic-related adverse effects mucosa in patients at high risk of an adverse outcome should they

following unnecessary dental prophylaxis in the United States. Infection Control & develop infective endocarditis.3 Recent data show that 80.9% of

Hospital Epidemiology, 42: 110–112, https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2020.1261

© The Author(s), 2020. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of The Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America.

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use.

Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology 111

Table 1. Occurrence of Adverse Effects Within 14 Days of Unnecessary Antibiotic Prophylaxis

Total Follow-Up Time,a Person Incidence rate

Variable No. of Events Years Per 1,000 Person Days 95% CI

Overall

Any allergy 319 5,213.46 0.168 0.150–0.185

Anaphylaxis only 5 5,219.57 0.003 0.0003–0.005

C. difficile infection 14 5,219.43 0.007 0.004–0.011

ED visit 1,629 5,188.93 0.860 0.825–0.894

Visits associated with any 1,916 5,183.39 1.012 0.976–1.048

adverse effectb

By antibiotic agent

Total Follow-Up Incidence Rate Risk Difference

Time,2 Per 1,000 Per 1,000

No. of Adverse Events Person Years Person Days 95% CI Person Days 95% CI

Amoxicillin 1,220 3,486.74 0.958 0.915–1.001 Reference Reference

Clindamycin 356 835.06 1.167 1.075–1.259 0.209 0.108–0.311

Others 340 861.60 1.080 0.991–1.170 0.122 0.023–0.222

Note. CI, confidence interval; ED, emergency department.

a

Subjects were censored at the occurrence of event of interest, loss-to-follow-up and at end of enrollment.

b

Primary end point defined as 14 days after prescription (composite endpoint of allergy, anaphylaxis, C. difficile infection, or ED visit).

antibiotic prophylaxis was unnecessary prior to dental proce- stratified by amoxicillin and clindamycin; corresponding 95% con-

dures.2 The objective of this study was to assess the harms of fidence intervals were calculated. Secondary end points included the

unnecessary antibiotic prophylaxis prior to dental procedures. risk difference of the primary end point between amoxicillin and

clindamycin per 1,000 PD, the incidence of CDI 30 days after the

Methods antibiotic, and the corresponding 95% CI for each. All analyses were

performed using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC)

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients prescribed and R version 3.3.1 (fmsb package) version 0.7.0 software

unnecessary antibiotic prophylaxis for a dental visit between 2011 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

and 2015 using the IBM Watson Health Marketscan Commercial

Claims/Encounters, Medicare Supplemental, Coordination of

Results

Benefits Research databases.2 Patients were included if they were

enrolled in commercial dental insurance and received unnecessary Of the 168,420 dental visits with antibiotic prophylaxis, 136,177

antibiotic prophylaxis. Antibiotic prophylaxis was defined as a ≤2 (80.9%) were unnecessary and were included for analysis (median

day supply of antibiotics dispensed within 7 days prior to a dental patient age, 62 years; interquartile range [IQR], 55–71; 58%

visit. Patients with a hospitalization or extra-oral infection 14 days women). Antibiotics prescribed included amoxicillin (67.9%), clin-

prior to antibiotic prophylaxis were excluded. Unnecessary antibi- damycin (15.5%), cephalexin (8.6%), azithromycin (2.8%), penicillin

otic prophylaxis was defined as prophylaxis in patients who did not (1.5%), and others (3%). For the primary endpoint, 1.4% of unnec-

undergo a procedure that manipulated the gingiva or tooth peri- essary prescriptions were associated with an AAE within 14 days; the

apex and did not have an appropriate cardiac diagnosis. Patients incidence of AAE was 1.01 per 1,000 PD, and ED visits (83%) and

with prosthetic joints were categorized as unnecessary (without allergies (16%) were the most frequent AAEs (Table 1).

a cardiac condition).2 Patients with multiple eligible visits were Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) incidence was 0.009 per

allowed to re-enter the cohort if visits were >7 days apart. 1,000 PD (95% CI, 0.006–0.012). Overall, AAEs were more common

The primary end point was any antibiotic adverse effect (AAE) with clindamycin (1.167 per 1,000 PD) than amoxicillin (0.958 per

within 14 days after prescription: composite of allergy, anaphy- 1,000 PD; risk difference, 0.209 per 1,000 PD; 95% CI, 0.108–0.33),

laxis, C. difficile infection (CDI), or emergency department (ED) including a higher risk of ED visit and allergy (Table 1 and

visit. Allergies and CDI were defined based on previously validated Supplemental Table 2 online).

International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) and

ICD-10 codes and ED visits were identified by provider and place Discussion

of service codes (Supplemental Table 1 online). Patients were cen-

sored at the occurrence of event, loss-to-follow-up, and end of This study is the first to characterize adverse effects related to

enrollment. unnecessary dental prophylaxis. Although the occurrence of an

AAE was rare (1.4%), serious AAEs (anaphylaxis, CDI) did occur.

A limited number of studies and case reports describe the adverse

Statistical analysis

effects of dental prophylaxis regardless of appropriateness.4-8 A

The primary end point of composite AAE incidence rate was mea- French database of voluntarily reported adverse effects contained

sured as events per 1,000 patient days (PD) in the overall cohort and 17 reports of anaphylaxis due to amoxicillin prophylaxis prior to

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use.

112 Alan E. Gross et al

dental procedures.4 Another study using a UK database assessed Acknowledgments. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do

adverse reactions following single doses of amoxicillin or clinda- not represent those of AHRQ, the Department of Veterans’ Affairs or the

mycin.5 Of 2.7 million amoxicillin prescriptions, 67 adverse reac- US government.

tions were reported: 16 anaphylaxis and 38 other allergies. Of 1.2

Financial support. Research was funded by Agency for Healthcare Research

million clindamycin prescriptions, 193 adverse reactions were and Quality (AHRQ no. R01 HS025177; principal investigator, Suda).

reported: 15 were fatal (12 due to CDI) and the remainder were

primarily gastrointestinal or allergy-related skin disorders. The Conflicts of interest. No authors report potential conflicts of interest relevant

only study in the United States, outside the current report, was to this article.

an evaluation of community-acquired CDI cases in Minnesota

which reported that 136 of 1,626 CDI cases (8%) were related to References

antibiotic prophylaxis for dental procedures.6 Consistent with 1. King LM, Bartoces M, Fleming-Dutra KE, Roberts RM, Hicks LA. Changes

the study by Thornhill et al,5 we observed a significantly greater in US outpatient antibiotic prescriptions from 2011–2016. Clin Infect Dis

rate of AAEs with clindamycin than with amoxicillin. Also consis- 2020;70:370–377.

tent with our findings, a previous study found that clindamycin 2. Suda KJ, Calip GS, Zhou J, et al. Assessment of the appropriateness of anti-

was associated with a greater rate of ED visits than amoxicillin.9 biotic prescriptions for infection prophylaxis before dental procedures,

Collectively, these studies show that even short courses used for 2011–2015. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e193909.

antibiotic prophylaxis, regardless of appropriateness of use, are 3. Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocar-

associated with patient harm. ditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guideline from the

American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki

Our study has some limitations. Comparisons were not per-

Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and

formed with patients unexposed to antibiotics; thus, the risk asso- the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and

ciated with inappropriate antibiotic prophylaxis could not be Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary

ascertained. Only patients with commercial dental insurance Working Group. Circulation 2007;116:1736–1754.

were included. ED visits could not be definitively attributed 4. Cloitre A, Duval X, Tubiana S, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for the preven-

to AAEs. Patients with adverse reactions but who did not seek tion of infective endocarditis for dental procedures is not associated with

medical care were not captured in this study because our end fatal adverse drug reactions in France. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal

point was based on medical coding. However, our study did 2019;24:e296–e304.

not rely on voluntary reporting by medical professionals to 5. Thornhill MH, Dayer MJ, Prendergast B, Baddour LM, Jones S, Lockhart

ascertain outcomes. Therefore, we may have been able to PB. Incidence and nature of adverse reactions to antibiotics used as endo-

carditis prophylaxis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015;70:2382–2388.

identify and more comprehensively characterize AAE rates than

6. Bye M. Antibiotic prescribing for dental procedures in community-associ-

previous investigations. ated Clostridium difficile cases, Minnesota, 2009–2015. Open Forum Infect

In conclusion, the risk of harm with unnecessary antibiotic Dis 2017;4. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofx162.001.

prophylaxis is not trivial. Because most AAEs are diagnosed in 7. Lochmann O, Kohout P, Vymola F. Anaphylactic shock following the ad-

medical settings, dentists may not be aware of these adverse ministration of clindamycin. J Hyg Epidemiol Microbiol Immunol

effects. These data provide further impetus to optimize prescrib- 1977;21:441–447.

ing of antibiotic prophylaxis prior to dental procedures, and 8. Bombassaro AM, Wetmore SJ, John MA. Clostridium difficile colitis following

improved prescribing may be facilitated via comprehensive, antibiotic prophylaxis for dental procedures. J Can Dent Assoc 2001;67:20–22.

multidisciplinary antimicrobial stewardship programs in dental 9. Shehab N, Patel PR, Srinivasan A, Budnitz DS. Emergency department

clinics.10 visits for antibiotic-associated adverse events. Clin Infect Dis 2008;47:

735–743.

10. Gross AE, Hanna D, Rowan SA, Bleasdale SC, Suda KJ. Successful imple-

Supplementary material. To view supplementary material for this article, mentation of an antibiotic stewardship program in an academic dental prac-

please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2020.1261 tice. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019;6:ofz067.

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use.

You might also like

- Pathfinder 2nd Edition House Rules Compendium - GM BinderDocument119 pagesPathfinder 2nd Edition House Rules Compendium - GM BinderBrandon PaulNo ratings yet

- The Miraculous Healing Properties of Oak BarkDocument4 pagesThe Miraculous Healing Properties of Oak BarkabbajieNo ratings yet

- Protective Effectiveness of Previous SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Hybrid ImmunityDocument12 pagesProtective Effectiveness of Previous SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Hybrid ImmunityCTV CalgaryNo ratings yet

- Anatomy & Physiology Unit 1Document29 pagesAnatomy & Physiology Unit 1Priyanjali SainiNo ratings yet

- All Cocci Are Gram Positive ExceptDocument7 pagesAll Cocci Are Gram Positive ExceptMariel Abatayo100% (1)

- The History of Immunology and VaccinesDocument32 pagesThe History of Immunology and VaccinesClement del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Review of Electron Beam Therapy PhysicsDocument36 pagesReview of Electron Beam Therapy PhysicsMaría José Sánchez LovellNo ratings yet

- Pneumonia Case StudyDocument21 pagesPneumonia Case StudyEmel Brant Jallores0% (1)

- CHP 11 Moderate Nonskeletal Problems in Preadolescent ChildrenDocument6 pagesCHP 11 Moderate Nonskeletal Problems in Preadolescent ChildrenJack Pai33% (3)

- Sample ExamDocument13 pagesSample ExamJenny Mendoza VillagonzaNo ratings yet

- Sonani2021 Article COVID-19VaccinationInImmunocompromisedDocument2 pagesSonani2021 Article COVID-19VaccinationInImmunocompromisedfmarialaura684No ratings yet

- Risk Assessment in Infection Control Which RisksDocument2 pagesRisk Assessment in Infection Control Which RiskspedroaorNo ratings yet

- Adult ImmunizationsDocument12 pagesAdult ImmunizationsredroseeeeeeNo ratings yet

- Influenza Vaccination Compliance Among Health Care Workers in A German University HospitalDocument6 pagesInfluenza Vaccination Compliance Among Health Care Workers in A German University HospitalWinatta SariiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 RRLDocument15 pagesChapter 2 RRLJohn Patrick AbeledaNo ratings yet

- The University of Chicago Press The Society For Healthcare Epidemiology of AmericaDocument11 pagesThe University of Chicago Press The Society For Healthcare Epidemiology of Americaزينب محمد عبدNo ratings yet

- Jis 334Document7 pagesJis 334vinicius.klabunde1001No ratings yet

- Logistical and Structural Challenges Are The Major Obstacles For Family Medicine Physicians' Ability To Administer Adult VaccinesDocument7 pagesLogistical and Structural Challenges Are The Major Obstacles For Family Medicine Physicians' Ability To Administer Adult Vaccinescarla laureanoNo ratings yet

- Journal Pone 0249531Document16 pagesJournal Pone 0249531Integração da Assistência à Saúde Militar (INASMIL)No ratings yet

- Association of Schools of Public HealthDocument11 pagesAssociation of Schools of Public HealthDarwinso AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness and Statin Use Among Adults in The United States, 2011-2017Document7 pagesInfluenza Vaccine Effectiveness and Statin Use Among Adults in The United States, 2011-2017ullyfatmalaNo ratings yet

- Comment: The Lancet Infectious Diseases, Frank Sandmann andDocument2 pagesComment: The Lancet Infectious Diseases, Frank Sandmann andAbdón Guerra FariasNo ratings yet

- Nejm VaricellaDocument9 pagesNejm VaricellaadityailhamNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0195670117300919 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S0195670117300919 Mainzezo.3kxNo ratings yet

- Otitis Media-Principles of Judicious Use of Antimicrobial AgentsDocument9 pagesOtitis Media-Principles of Judicious Use of Antimicrobial AgentsYogie Rinaldi HutasoitNo ratings yet

- Robert - Califf@fda - Hhs.gov Peter - Marks@fda - Hhs.govDocument10 pagesRobert - Califf@fda - Hhs.gov Peter - Marks@fda - Hhs.govJoanaNo ratings yet

- Golden Hour CCM Arthur Van Zanten IC1Document3 pagesGolden Hour CCM Arthur Van Zanten IC1Sara NicholsNo ratings yet

- Quantifying Risk For SARS CoV 2 Infection Among Nur 2022 Journal of The AmerDocument6 pagesQuantifying Risk For SARS CoV 2 Infection Among Nur 2022 Journal of The AmerPuttryNo ratings yet

- Multidrug-Resistant Bacterial Infections in U.S. Hospitalized Patients, 2012-2017Document11 pagesMultidrug-Resistant Bacterial Infections in U.S. Hospitalized Patients, 2012-2017sebastianNo ratings yet

- PR - 03 Evaluation of The Effectiveness of Two Vaccination Programs On The Zootechnical Parameters of BroilersDocument1 pagePR - 03 Evaluation of The Effectiveness of Two Vaccination Programs On The Zootechnical Parameters of BroilersJosias VogtNo ratings yet

- EgyptJInternMed313326-8034788 221907Document6 pagesEgyptJInternMed313326-8034788 221907Na NisNo ratings yet

- Nosocomial Infections: The Definition Criteria: Ijms Vol 37, No 2, June 2012Document2 pagesNosocomial Infections: The Definition Criteria: Ijms Vol 37, No 2, June 2012fathimzahroNo ratings yet

- Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2021Document15 pagesMayo Clinic Proceedings 2021cdsaludNo ratings yet

- Ppe 14Document11 pagesPpe 14Sajin AlexanderNo ratings yet

- Jamainternal - Edelman - 2019 - Oi - 180103 2Document8 pagesJamainternal - Edelman - 2019 - Oi - 180103 2Asti Sauna MentariNo ratings yet

- Mathematical Modeling To Inform Vaccination Strategies and Testing Approaches ForDocument19 pagesMathematical Modeling To Inform Vaccination Strategies and Testing Approaches ForLuckyVenNo ratings yet

- Bmjebm 2021 111901.fullDocument6 pagesBmjebm 2021 111901.fullMonika Diaz KristyanindaNo ratings yet

- A Framework For Nosocomial Transmission of Emerging CoronavirusesDocument3 pagesA Framework For Nosocomial Transmission of Emerging Coronavirusesyuvanshi jainNo ratings yet

- Prevention Strategy of Infectious Diseases For Health Care WorkersDocument31 pagesPrevention Strategy of Infectious Diseases For Health Care WorkersarinNo ratings yet

- Fitzpatricks Dermatology 9th Edition 3124Document1 pageFitzpatricks Dermatology 9th Edition 3124DennisSujayaNo ratings yet

- Level of ComplianceDocument18 pagesLevel of Compliancecarl jason talanNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 1Document9 pagesJurnal 1Riyan TrequartistaNo ratings yet

- Journal Gerontik 1Document11 pagesJournal Gerontik 1AgUnk MancuNianNo ratings yet

- Pleasants - Ethics PaperDocument15 pagesPleasants - Ethics Paperapi-380115954No ratings yet

- Journal Pre-Proof: International Journal of Infectious DiseasesDocument27 pagesJournal Pre-Proof: International Journal of Infectious DiseasesMohammed Shuaib AhmedNo ratings yet

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 and Vaccination of Children and Adolescents - Prospects and Challenges - (ENG)Document6 pagesCoronavirus Disease 2019 and Vaccination of Children and Adolescents - Prospects and Challenges - (ENG)Handoko MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Food and Chemical Toxicology: Stephanie Seneff, Greg Nigh, Anthony M. Kyriakopoulos, Peter A. McculloughDocument19 pagesFood and Chemical Toxicology: Stephanie Seneff, Greg Nigh, Anthony M. Kyriakopoulos, Peter A. McculloughBeto CuevasNo ratings yet

- Jamainternal Gupta 2024 Oi 240004 1710785795.21061Document9 pagesJamainternal Gupta 2024 Oi 240004 1710785795.21061Jose Artur AlbuquerqueNo ratings yet

- PDF Jurding FikriDocument10 pagesPDF Jurding FikriAssifa RidzkiNo ratings yet

- Key Steps in Vaccine Development: Peter L. Stern, PHDDocument11 pagesKey Steps in Vaccine Development: Peter L. Stern, PHDAndreaSánchezdelRioNo ratings yet

- PR - 04 Impact On The Cost of Production and Zootechnical Performance of Broilers Submitted To Two Different Vaccination ProgramsDocument1 pagePR - 04 Impact On The Cost of Production and Zootechnical Performance of Broilers Submitted To Two Different Vaccination ProgramsJosias VogtNo ratings yet

- Herd Immunity: A Realistic Target?: Mini Review Open AccessDocument5 pagesHerd Immunity: A Realistic Target?: Mini Review Open AccessAshwinee KadelNo ratings yet

- The Prevention of InfectionDocument7 pagesThe Prevention of InfectionWilton Wylie IskandarNo ratings yet

- Oseltamivir Use To Prevent Hospitalization in Influenza - JAMA INT MED - 2023Document10 pagesOseltamivir Use To Prevent Hospitalization in Influenza - JAMA INT MED - 2023Matheus BissaNo ratings yet

- Funding: Tracheal Intubation in COVID-19 Patients: Update On Recommendations. Response To BR J Anaesth 2020 125: E28e37Document3 pagesFunding: Tracheal Intubation in COVID-19 Patients: Update On Recommendations. Response To BR J Anaesth 2020 125: E28e37Muhammad RenaldiNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors For Ventilator-Associated Events - Liu 2019Document6 pagesRisk Factors For Ventilator-Associated Events - Liu 2019Maxi BoniniNo ratings yet

- Seguridad Vacunal: Precauciones y Contraindicaciones de Las Vacunas. Reacciones Adversas. FarmacovigilanciaDocument25 pagesSeguridad Vacunal: Precauciones y Contraindicaciones de Las Vacunas. Reacciones Adversas. FarmacovigilanciaMaribel Catalan HabasNo ratings yet

- Vaccine Epidemiology Efficacy EffectivenessDocument5 pagesVaccine Epidemiology Efficacy EffectivenessCesar Augusto Hernandez GualdronNo ratings yet

- Management of Newly Diagnosed HIV InfectionDocument16 pagesManagement of Newly Diagnosed HIV InfectionRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- Piis258953702200061x PDFDocument11 pagesPiis258953702200061x PDFRong LiuNo ratings yet

- Right To Refuse Flu ShotsDocument4 pagesRight To Refuse Flu ShotsBZ Riger100% (2)

- TreatmentOIGESIDA 2008, NoDocument24 pagesTreatmentOIGESIDA 2008, NoDra Carolina Escalante Neurologa de AdultosNo ratings yet

- Garner 1511222Document17 pagesGarner 1511222Bj LongNo ratings yet

- IK Wang - Diabetes Vaccine Cost EffectivenessDocument7 pagesIK Wang - Diabetes Vaccine Cost Effectivenessreza_adrian_2No ratings yet

- Uncorrected Manuscript: Efficacy and Safety of COVID-19 Vaccines in Older PeopleDocument9 pagesUncorrected Manuscript: Efficacy and Safety of COVID-19 Vaccines in Older PeopleKiky HaryantariNo ratings yet

- 40 JMSCRDocument8 pages40 JMSCRVani Junior LoverzNo ratings yet

- MeningoencephalitisDocument2 pagesMeningoencephalitisGaluh Kresna BayuNo ratings yet

- Nej Mo A 1306801Document11 pagesNej Mo A 1306801Anonymous 8w9QEGNo ratings yet

- Primary and Secondary Immunodeficiency: A Case-Based Guide to Evaluation and ManagementFrom EverandPrimary and Secondary Immunodeficiency: A Case-Based Guide to Evaluation and ManagementNo ratings yet

- HR PWDDocument13 pagesHR PWDDiane UyNo ratings yet

- Post-Cardiac Arrest Therapeutic Hypothermia Targeted Temperature Manangement (TTM) Quick SheetDocument3 pagesPost-Cardiac Arrest Therapeutic Hypothermia Targeted Temperature Manangement (TTM) Quick SheetkimberlyNo ratings yet

- Application Form (Pledge Form) For Whole Body DonationDocument1 pageApplication Form (Pledge Form) For Whole Body DonationVasanthakumar BasavaNo ratings yet

- Table 1. Diagnostic Criteria For Kawasaki DiseaseDocument2 pagesTable 1. Diagnostic Criteria For Kawasaki DiseasenasibdinNo ratings yet

- Malaria Treatment 2013Document75 pagesMalaria Treatment 2013Rheinny IndrieNo ratings yet

- Consulta de MedicamentosDocument39 pagesConsulta de MedicamentosJhonWainerLopezNo ratings yet

- 3-Gmc Claim Form HDFC ErgoDocument3 pages3-Gmc Claim Form HDFC ErgoDT worldNo ratings yet

- Teknik SAB Ideal-1Document31 pagesTeknik SAB Ideal-1Buatlogin DoangNo ratings yet

- All PackageRates (ABPMJAY) PDFDocument300 pagesAll PackageRates (ABPMJAY) PDFSumit Soni0% (1)

- Bell's Palsy Treatments & Medications - SingleCareDocument11 pagesBell's Palsy Treatments & Medications - SingleCareRoxan PacsayNo ratings yet

- Psych 2012123115115620Document6 pagesPsych 2012123115115620Rara QamaraNo ratings yet

- United States v. Algon Chemical Inc., A Corporation, and Edward Latinsky, An Individual, 879 F.2d 1154, 3rd Cir. (1989)Document18 pagesUnited States v. Algon Chemical Inc., A Corporation, and Edward Latinsky, An Individual, 879 F.2d 1154, 3rd Cir. (1989)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Interaksi DadahDocument36 pagesInteraksi Dadahnorish7100% (2)

- 9000 One Liner GK PDF in Hindi (For More Book - WWW - Gktrickhindi.com)Document25 pages9000 One Liner GK PDF in Hindi (For More Book - WWW - Gktrickhindi.com)Ashish gautam100% (1)

- Biofeedback 2000x-Pert Hardware ManualDocument45 pagesBiofeedback 2000x-Pert Hardware ManualNery BorgesNo ratings yet

- 수산부산물에 대한 해양바이오산업 활용 의향 조사 연구Document15 pages수산부산물에 대한 해양바이오산업 활용 의향 조사 연구이수하1118No ratings yet

- Stratification in The Cox Model: Patrick BrehenyDocument20 pagesStratification in The Cox Model: Patrick BrehenyRaiJúniorNo ratings yet

- ALP Crestline PDFDocument2 pagesALP Crestline PDFJashmyn JagonapNo ratings yet

- Act 1 Urinary SystemDocument20 pagesAct 1 Urinary Systemisabellamarie.castillo.crsNo ratings yet

- Case Study Discretion Advised PDFDocument12 pagesCase Study Discretion Advised PDFGustavo MooriNo ratings yet

- Csa Z32 - Testing Guideline and Procedures: PO Box 20020 Red Deer, AB T4N 6X5 Phone: 403.986.2939Document8 pagesCsa Z32 - Testing Guideline and Procedures: PO Box 20020 Red Deer, AB T4N 6X5 Phone: 403.986.2939tim4109No ratings yet