Professional Documents

Culture Documents

19 Myth by Tolkien by Joe Mandala (October, 1999)

Uploaded by

Valentin TapataCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

19 Myth by Tolkien by Joe Mandala (October, 1999)

Uploaded by

Valentin TapataCopyright:

Available Formats

Myth, by Tolkien

© Joe Mandala 1999

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien had an unremarkable birth. He was born in South

Africa, and lived his first few uneventful years there. He then took an unexciting

trip back to England where he was to stay. As a man, Tolkien was quite

unremarkable in appearance, wore generally unremarkable clothes, and led what

some would suspect was an unremarkable life. He in fact seemed to be the

archtypical Oxford don - gazing off into nothingness and mumbling about this or

that. There are a few things about this man, however, that are quite remarkable.

Somewhere along the way he developed an intense sense of perfectionism. This

was perhaps the single most important trait that Tolkien held in relation to his work

and writing.

It would not be right to say that Tolkien led an uneventful life. His mother and

father died when he was quite young, his mother's death being quite a blow. He

served in the Great War, and many of his friends were killed. He saw much of what

is wrong with us during the war. He married and had children, certainly an

important aspect in Tolkien's life. And, of course, he wrote one of the most popular

and acclaimed series of books that has ever been written.

It was Tolkien's perfectionism that whittled and worked at a great mass of

manuscript to produce The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, though this

perfectionism also showed in his exhaustive treatises on philology that was his

chosen life's work. His avowed love, however, lay with what became published as

The Silmarillion. So why did not Tolkien work first and foremost on this great

volume? It seems that his perfectionism would not allow it to go to press with any

misconceptions, mistakes, or malapropisms.

It is easier to understand Tolkien's obsession with perfecting this body of myth (for

myth it is) when one considers his goal. He wanted a mythology "for England;" one

with the scope of human emotion and thought that would rival and surpass the

fragments of any earlier mythology such as the Kalevala or the Eddas. Tolkien felt

that mythology is very much tied up in the identity of a culture, and that the loss of

such a cultural trait can only bring disillusionment and a kind of cultural identity

crisis that would result in the loss of any "national spirit." He saw myth as a way to

defend, perhaps, his beloved trees and countryside, for if everyone read myth and

knew myth as he did, would they not grow to love the countryside as reminiscent of

the great stories?

The Silmarillion was an attempt to create a secondary world in which truths

Tolkien believed and lived by could be couched in a universal manner. That is to

say, Tolkien believed that his myths must be imbued with a Christian ethic, though

any obvious or direct intrusion from this world would destroy the "willing

suspension of disbelief" that was necessary for the effect. The Myth, then, must be

comprehensive in its morals and very, very internally consistent. This is what held

up the creation of this volume. Tolkien reworked it, rewrote it, rephrased it, and did

everything he could, constantly, to perfect his epic. He was such a perfectionist that

it never was published in his lifetime (though he thought he would live longer than

he did).

The Silmarillion became a fluid, changing group of stories that represented the core

ideals of Tolkien's mythology. Perhaps this is the crux of the matter. The earlier

fragments of the ancient mythologies Tolkien used as references to a more

complete one were simply written down forms of an oral tradition. A tradition that

changed constantly as one poet would interpret the same story in his own unique

way. So Tolkien constantly changed his own stories, never satisfied with any one

"version" as the "correct" one, for in truth there could not be a single "correct"

version. Rather, the ideals and morals involved were what was central, and any

"fixing" of the stories into one form would take something from this - for then you

leave it open to examination on baser levels.

Like his own literary creation Mr. Niggle, Tolkien started by creating a story

around a moral - a myth, his "leaf." He then began to trace this myth back to

imaginary origins and created a few more on the way. As this work continued, the

myths grew into a mythology, but a static one, without the motion and verve that

was desired, without the bending limbs and rustling leaves. So he kept at it,

changing and amending so that in his own mind the stories had some motion - a

changing from earlier to later and back again. The mythology evolved within his

own creative aura. It could not, however, be written down this way, and so the

work of choosing the best of a line of stories began, but was not finished by him.

This is the perfectionism that stalled The Silmarillion and kept The Lord of the

Rings for seventeen years in the making. The written word cannot convey, perhaps,

the spoken and translated myth.

Luckily for us, our Niggle had a son that could complete his work. The entire

vision, of course, is left for Tolkien to contemplate in heaven as his creation Mr.

Niggle does, and for us to yearn toward as we catch our glimpses here and there.

"Before him stood the Tree, his Tree, finished. If you could say that of a Tree that

was alive, its leaves opening, its branches growing and bending in the wind that

Niggle had so often felt and guessed, and had so often failed to catch. He gazed at

the Tree, and slowly he lifted his arms and opened them wide. 'It's a gift!' he said."

You might also like

- War of The Fantasy Worlds - C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien On Art and Imagination-Praeger (2009)Document257 pagesWar of The Fantasy Worlds - C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien On Art and Imagination-Praeger (2009)Fco Gonzalez Lopez100% (1)

- J.R.R. Tolkien's Take On The TruthDocument3 pagesJ.R.R. Tolkien's Take On The TruthDaniel ANo ratings yet

- How To Read The SilmarillionDocument32 pagesHow To Read The Silmarilliontox1n100% (4)

- J R R Tolkien Artist Illustrator PDFDocument318 pagesJ R R Tolkien Artist Illustrator PDFBreezy Daniel87% (15)

- Guide to Middle Earth: Tolkien and The Lord of the RingsFrom EverandGuide to Middle Earth: Tolkien and The Lord of the RingsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (9)

- J. R. R. Tolkien Bibliography RareDocument5 pagesJ. R. R. Tolkien Bibliography RareRafael SousaNo ratings yet

- Defending Middle-Earth: Tolkien: Myth and ModernityFrom EverandDefending Middle-Earth: Tolkien: Myth and ModernityRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (20)

- Essays On Music in TolkienDocument217 pagesEssays On Music in TolkienPedroNo ratings yet

- Tolkien in the Twenty-First Century: The Meaning of Middle-Earth TodayFrom EverandTolkien in the Twenty-First Century: The Meaning of Middle-Earth TodayNo ratings yet

- The Essential J.R.R. Tolkien Sourcebook A Fans Guide To Middle-Earth and BeyondDocument250 pagesThe Essential J.R.R. Tolkien Sourcebook A Fans Guide To Middle-Earth and BeyondAlexandra Maria Neagu100% (9)

- Other Minds Magazine, Issue - Com9leteDocument87 pagesOther Minds Magazine, Issue - Com9leteJayHermannNo ratings yet

- Elves NamesDocument73 pagesElves NamesGeorgePinteaNo ratings yet

- True Myth Tolkiens Catholic ImaginationDocument13 pagesTrue Myth Tolkiens Catholic Imaginationγιωργος βαμβουκαςNo ratings yet

- The Lord of the Rings - 101 Amazing Facts You Didn't Know: 101BookFacts.comFrom EverandThe Lord of the Rings - 101 Amazing Facts You Didn't Know: 101BookFacts.comNo ratings yet

- The Song of Middle-Earth J. R. R. Tolkiens Themes, Symbols and Myths (Harvey, DavidTolkien, J. R. R.Tolkien Etc.)Document190 pagesThe Song of Middle-Earth J. R. R. Tolkiens Themes, Symbols and Myths (Harvey, DavidTolkien, J. R. R.Tolkien Etc.)Ratte 999100% (1)

- The Legend of Sigurd & Gudrún by J.R.R. TolkienDocument13 pagesThe Legend of Sigurd & Gudrún by J.R.R. TolkienKit CushionNo ratings yet

- Lord of The RingsDocument18 pagesLord of The RingsLavu DianaNo ratings yet

- What Tolkien Officially Said About Elf SexDocument5 pagesWhat Tolkien Officially Said About Elf Sexthe_doom_dudeNo ratings yet

- Sindarin-English Dictionary - 3rd EditionDocument165 pagesSindarin-English Dictionary - 3rd EditionIoanaNo ratings yet

- J.R.R. Tolkien, The History of Middle-Earth, Harpercollins, London, 12 VolumesDocument14 pagesJ.R.R. Tolkien, The History of Middle-Earth, Harpercollins, London, 12 Volumesthe_tigdraNo ratings yet

- J. R. R. Tolkien's Influence in English LiteratureDocument5 pagesJ. R. R. Tolkien's Influence in English LiteratureSteph_8D100% (4)

- The Spiritual World of The HobbitDocument26 pagesThe Spiritual World of The HobbitBethany House Publishers83% (6)

- Numenor Tolkiens Literary UtopiaDocument6 pagesNumenor Tolkiens Literary UtopiaCadmilosNo ratings yet

- The HobbitDocument27 pagesThe HobbitMehwish MalikNo ratings yet

- Satan and The Silmarillion John MiltonsDocument6 pagesSatan and The Silmarillion John MiltonsDelano BorgesNo ratings yet

- Gale Researcher Guide for: J. R. R. Tolkien: Architect of Modern FantasyFrom EverandGale Researcher Guide for: J. R. R. Tolkien: Architect of Modern FantasyNo ratings yet

- Creation and Beauty in Tolkien’s Catholic Vision: A Study in the Influence of Neoplatonism in J. R. R. Tolkien’s Philosophy of Life as “Being and Gift”From EverandCreation and Beauty in Tolkien’s Catholic Vision: A Study in the Influence of Neoplatonism in J. R. R. Tolkien’s Philosophy of Life as “Being and Gift”No ratings yet

- Verbum Caro Factum Est - JRR Tolkien's Philosophy of LanguageDocument5 pagesVerbum Caro Factum Est - JRR Tolkien's Philosophy of LanguageKyaxavierNo ratings yet

- Frodo Lives: The Enduring Applicability of J.R.R. TolkienDocument14 pagesFrodo Lives: The Enduring Applicability of J.R.R. TolkienbadboigabNo ratings yet

- Deep Magic October 2003Document145 pagesDeep Magic October 2003Deep Magic100% (2)

- Folklore 117-2 (Fimi)Document15 pagesFolklore 117-2 (Fimi)trivialpursuitNo ratings yet

- mc28 Hammond and Scull Ad1 PiDocument12 pagesmc28 Hammond and Scull Ad1 Piapi-330408224No ratings yet

- Deep Magic May 2003Document170 pagesDeep Magic May 2003Deep Magic100% (1)

- KeithseniorpaperDocument8 pagesKeithseniorpaperapi-357955838No ratings yet

- The Battle for Middle-earth: Tolkien's Divine Design in The Lord of the RingsFrom EverandThe Battle for Middle-earth: Tolkien's Divine Design in The Lord of the RingsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (19)

- Chronological Middle-Earth Reading ListDocument3 pagesChronological Middle-Earth Reading ListNick Senger100% (15)

- Imagenes Del Tolkien Libro PDFDocument65 pagesImagenes Del Tolkien Libro PDFErick Chalco100% (1)

- Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle-earthFrom EverandTolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle-earthRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (100)

- Tolkien On PrayerDocument7 pagesTolkien On Prayerapi-309267003No ratings yet

- Middle Earth Meets Middle England - China MievilleDocument5 pagesMiddle Earth Meets Middle England - China MievilleJames DouglasNo ratings yet

- One Bucket List to Rule Them All: 250 Ideas for Tolkien Fans to Celebrate Their Favorite Books, TV Shows, Movies, and MoreFrom EverandOne Bucket List to Rule Them All: 250 Ideas for Tolkien Fans to Celebrate Their Favorite Books, TV Shows, Movies, and MoreNo ratings yet

- JRR Tolkein On The Problem of EvilDocument14 pagesJRR Tolkein On The Problem of EvilmarkworthingNo ratings yet

- Study Guide to The Fellowship of the Ring by JRR TolkienFrom EverandStudy Guide to The Fellowship of the Ring by JRR TolkienNo ratings yet

- Beren and Lúthien by J.R.R. TolkienDocument7 pagesBeren and Lúthien by J.R.R. TolkienJoseph SuezoNo ratings yet

- Beren and Lúthien by J.R.R. TolkienDocument7 pagesBeren and Lúthien by J.R.R. TolkienJoseph SuezoNo ratings yet

- Ensayos de JRR TolkienDocument8 pagesEnsayos de JRR Tolkieng672wmjj100% (1)

- Bakalarska Prace - Final Version PDFDocument34 pagesBakalarska Prace - Final Version PDFАлександра ТошеваNo ratings yet

- J. R. R. Tolkien - Quotes Collection: Biography, Achievements And Life LessonsFrom EverandJ. R. R. Tolkien - Quotes Collection: Biography, Achievements And Life LessonsNo ratings yet

- Tolkien S Fantasy World: Haifeng PuDocument4 pagesTolkien S Fantasy World: Haifeng PuSunAlfiNo ratings yet

- JRR Tolkien Research PaperDocument5 pagesJRR Tolkien Research Paperfvgh9ept100% (1)

- Tosolt FantasyeducationarticleDocument4 pagesTosolt Fantasyeducationarticleapi-741180266No ratings yet

- Research Paper JRR TolkienDocument8 pagesResearch Paper JRR Tolkienwftvsutlg100% (1)

- On Eagles' Wings: An Exploration of Eucatastrophe in Tolkien's FantasyFrom EverandOn Eagles' Wings: An Exploration of Eucatastrophe in Tolkien's FantasyNo ratings yet

- Against The Cult of Travel - The Art of ManlinessDocument18 pagesAgainst The Cult of Travel - The Art of Manlinessthehoa229No ratings yet

- Tolkien & IrelandDocument10 pagesTolkien & IrelandZenryokuNo ratings yet

- J. R. R. Tolkien: Rings Trilogy. The Works Have Had A Devoted International Fan Base and Been AdaptedDocument2 pagesJ. R. R. Tolkien: Rings Trilogy. The Works Have Had A Devoted International Fan Base and Been AdaptedguachupinaNo ratings yet

- The Tridimensionality of Myth in TolkienDocument5 pagesThe Tridimensionality of Myth in TolkienJorge RodriguezNo ratings yet

- J. R. R. Tolkien: Nostalgia and Longing For An Impossible PastDocument8 pagesJ. R. R. Tolkien: Nostalgia and Longing For An Impossible PastsergioNo ratings yet

- A Companion To J R R Tolkien Edited by SDocument10 pagesA Companion To J R R Tolkien Edited by SyahyaNo ratings yet

- Essay - JRR Tolkien BiographyDocument8 pagesEssay - JRR Tolkien BiographyVictor MartinsNo ratings yet

- An Essay of The Lord of The RingsDocument6 pagesAn Essay of The Lord of The RingsLord HawreghiNo ratings yet

- EbookDocument10 pagesEbookapi-347875564No ratings yet

- TolkienDocument8 pagesTolkienarminvandexterNo ratings yet

- J. R. R. Tolkien: South AfricaDocument1 pageJ. R. R. Tolkien: South Africasonya26No ratings yet

- Thesis On JRR TolkienDocument5 pagesThesis On JRR Tolkienlaurawilliamslittlerock100% (2)

- Revised Editions of Tolkien ScholarshipDocument4 pagesRevised Editions of Tolkien Scholarshipflaming4321No ratings yet

- Alex Crim - Annotated Bibliography - Dr. Vaccaro - Senior EnglishDocument8 pagesAlex Crim - Annotated Bibliography - Dr. Vaccaro - Senior EnglishVote Crim 2020No ratings yet

- 08.1 Fire and Ice Part II - The Watcher of Carn Dûm - Locations by Craig Pay (February, 2001)Document14 pages08.1 Fire and Ice Part II - The Watcher of Carn Dûm - Locations by Craig Pay (February, 2001)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

- 01 A Comprehensive Calendar For Middle-Earth by Malcolm Wolter (January, 2001)Document1 page01 A Comprehensive Calendar For Middle-Earth by Malcolm Wolter (January, 2001)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

- 02 MERP The Simple Rulez - Introduction by George Chatzipetros (February, 2001)Document2 pages02 MERP The Simple Rulez - Introduction by George Chatzipetros (February, 2001)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

- 07 MERP The Simple Rulez - MERP Character Record Sheet by George Chatzipetros (February, 2001)Document1 page07 MERP The Simple Rulez - MERP Character Record Sheet by George Chatzipetros (February, 2001)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

- 05 MERP The Simple Rulez - Character Creation by George Chatzipetros (February, 2001)Document2 pages05 MERP The Simple Rulez - Character Creation by George Chatzipetros (February, 2001)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

- 04 MERP The Simple Rulez - Magic by George Chatzipetros (February, 2001)Document11 pages04 MERP The Simple Rulez - Magic by George Chatzipetros (February, 2001)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

- 08.3 Expedition To The Haunted Vale - The Hillman Camp by Phillip Gladney (October, 2000)Document3 pages08.3 Expedition To The Haunted Vale - The Hillman Camp by Phillip Gladney (October, 2000)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

- 07.8 The Horn of Nimraug - Part 1 Fire and Ice, Suggested Experience Points by Craig Pay (August, 2000)Document2 pages07.8 The Horn of Nimraug - Part 1 Fire and Ice, Suggested Experience Points by Craig Pay (August, 2000)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

- 12 A Review of Other Hands Issue 29-30 by Joe Mandala (December, 2000)Document6 pages12 A Review of Other Hands Issue 29-30 by Joe Mandala (December, 2000)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

- 09 A Review of Other Hands Issue 28 - Nathan Jaworski (October, 2000)Document2 pages09 A Review of Other Hands Issue 28 - Nathan Jaworski (October, 2000)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

- 08 A Ready-To-Run Adventure Expedition To The Haunted Vale by Phillip Gladney (October, 2000)Document5 pages08 A Ready-To-Run Adventure Expedition To The Haunted Vale by Phillip Gladney (October, 2000)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

- 07.6 The Horn of Nimraug - Part 1 Fire and Ice, NPC Descriptions by Craig Pay (August, 2000)Document11 pages07.6 The Horn of Nimraug - Part 1 Fire and Ice, NPC Descriptions by Craig Pay (August, 2000)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

- 08.4 Expedition To The Haunted Vale - Master NPC and Military Forces Tables by Phillip Gladney (October, 2000)Document2 pages08.4 Expedition To The Haunted Vale - Master NPC and Military Forces Tables by Phillip Gladney (October, 2000)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

- 20.6 The Siege of Harnalda - The Angle Forces and Military Stats by Phillip Gladney (October, 1999)Document6 pages20.6 The Siege of Harnalda - The Angle Forces and Military Stats by Phillip Gladney (October, 1999)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

- 07.3 The Horn of Nimraug - Part 1 Fire and Ice, Conclusion by Craig Pay (August, 2000)Document1 page07.3 The Horn of Nimraug - Part 1 Fire and Ice, Conclusion by Craig Pay (August, 2000)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

- 06 Quenta Roqueni Chapter 17 by Vincent Roiron and Lowell R. Matthews (May, 2000)Document15 pages06 Quenta Roqueni Chapter 17 by Vincent Roiron and Lowell R. Matthews (May, 2000)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

- 07.2 The Horn of Nimraug - Part 1 Fire and Ice, The Journey North by Craig Pay (August, 2000)Document3 pages07.2 The Horn of Nimraug - Part 1 Fire and Ice, The Journey North by Craig Pay (August, 2000)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

- 20.5 The Siege of Harnalda - Encounters in The Northern Angle by Phillip Gladney (October, 1999)Document6 pages20.5 The Siege of Harnalda - Encounters in The Northern Angle by Phillip Gladney (October, 1999)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

- 03 Quenta Roqueni Chapters 6 To 10 by Vincent Roiron and Lowell R. Mattews (February, 2000)Document17 pages03 Quenta Roqueni Chapters 6 To 10 by Vincent Roiron and Lowell R. Mattews (February, 2000)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

- 20.1 A Ready-To-Run Adventure The Siege of Harnalda - Thuin Boid Map and Description by Phillip Gladney (October, 1999)Document5 pages20.1 A Ready-To-Run Adventure The Siege of Harnalda - Thuin Boid Map and Description by Phillip Gladney (October, 1999)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

- 20.2 The Siege of Harnalda - Rhudaurim Camp Map and Description by Phillip Gladney (October, 1999)Document4 pages20.2 The Siege of Harnalda - Rhudaurim Camp Map and Description by Phillip Gladney (October, 1999)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

- 07 A Ready-To-Run Adventure The Horn of Nimraug - Part 1 Fire and Ice, Introduction by Craig Pay (August, 2000)Document2 pages07 A Ready-To-Run Adventure The Horn of Nimraug - Part 1 Fire and Ice, Introduction by Craig Pay (August, 2000)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

- 12 A Ready-To-Run Adventure The Marauders by Phillip Gladney (July, 1999)Document8 pages12 A Ready-To-Run Adventure The Marauders by Phillip Gladney (July, 1999)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

- 17 Peoples of Middle-Earth Men of Arthedain - Rangers of The North by Joe Mandala (September, 1999)Document1 page17 Peoples of Middle-Earth Men of Arthedain - Rangers of The North by Joe Mandala (September, 1999)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

- 15 Quenta Roqueni Prologue by Vincent Roiron, Trevor Sanders, and Lowell R. Matthews (September, 1999) - FictionDocument20 pages15 Quenta Roqueni Prologue by Vincent Roiron, Trevor Sanders, and Lowell R. Matthews (September, 1999) - FictionValentin TapataNo ratings yet

- 20 A Ready-To-Run Adventure The Siege of Harnalda by Phillip Gladney (October, 1999)Document7 pages20 A Ready-To-Run Adventure The Siege of Harnalda by Phillip Gladney (October, 1999)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

- 16 Peoples of Middle-Earth Men of Arthedain - Faradrim Aran by Joe Mandala (September, 1999)Document1 page16 Peoples of Middle-Earth Men of Arthedain - Faradrim Aran by Joe Mandala (September, 1999)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

- 11 Peoples of Middle-Earth Men of Gondor - Estehildi by Joe Mandala (June, 1999)Document2 pages11 Peoples of Middle-Earth Men of Gondor - Estehildi by Joe Mandala (June, 1999)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

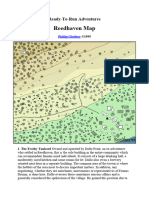

- 07.1 The Scourge of Smallforge - Reedhaven Map and Village Description by Phillip Gladney (May, 1999)Document2 pages07.1 The Scourge of Smallforge - Reedhaven Map and Village Description by Phillip Gladney (May, 1999)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

- 08 Aldern A Lord of Middle-Earth by Joe Mandala (May, 1999)Document3 pages08 Aldern A Lord of Middle-Earth by Joe Mandala (May, 1999)Valentin TapataNo ratings yet

- Codya 0.6Document155 pagesCodya 0.6alec taylorNo ratings yet

- Sindarin-English Dictionary - 4th EditionDocument175 pagesSindarin-English Dictionary - 4th EditionZenier HerreraNo ratings yet

- JRR Tolkien Book Beren and Lúthien Published After 100 YearsDocument5 pagesJRR Tolkien Book Beren and Lúthien Published After 100 Yearskam-sergiusNo ratings yet

- Names For A Dark Lord by Helge FauskangerDocument6 pagesNames For A Dark Lord by Helge FauskangerFernanda LopesNo ratings yet

- AtanamiliDocument18 pagesAtanamilidynamo923No ratings yet

- 1Document5 pages1Maja MajaNo ratings yet

- The Silmarillion (Document8 pagesThe Silmarillion (Dharmesh patelNo ratings yet

- The Evolution From Primitive Elvish To QuenyaDocument60 pagesThe Evolution From Primitive Elvish To QuenyaGloringil BregorionNo ratings yet

- Earendil The MarinerDocument9 pagesEarendil The MarinerVucas LermillionNo ratings yet

- When JRR Tolkien Bet CS Lewis - The Wager That Gave Birth To The Lord of The RingsDocument22 pagesWhen JRR Tolkien Bet CS Lewis - The Wager That Gave Birth To The Lord of The RingsFrancisco Elías Pereira MacielNo ratings yet

- The ValarDocument6 pagesThe ValarRegie Rey AgustinNo ratings yet