Professional Documents

Culture Documents

PEO Modelo

Uploaded by

Sofia Ibarra GonzalezOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

PEO Modelo

Uploaded by

Sofia Ibarra GonzalezCopyright:

Available Formats

Understanding parenting occupations in

Critical review

neonatal intensive care: application of the

Person-Environment-Occupation Model

Deanna Gibbs,1 Kobie Boshoff 2 and Alison Lane 3

Key words: The adoption of family-centred care principles within neonatal intensive care,

Neonatology, parenting, including support for the development of the parental role, has been increasing

occupation. in profile over the past decade. During this period, occupational therapy has also

had an emerging role in the provision of services within neonatal intensive care.

However, there has been limited exploration of the concept of parenting as an

occupation as a means of supporting parental role development within the neonatal

intensive care unit (NICU). In accordance with the philosophy of family-centred

care, opportunities exist to determine how the occupational efforts of parents

and preterm infants can best be supported.

This paper provides a review of the current literature and its application to the

Person-Environment-Occupation (PEO) Model as a framework for illuminating the

acquisition of parenting occupations in the NICU. Illustration is provided of how

the application of the PEO Model can be used to direct occupational therapy

practice to incorporate a focus on family-centred care and the development of an

occupation-based approach through which practice can be enhanced, ensuring

that both the infant’s and the family’s needs are recognised and addressed.

Introduction

Increasing survival rates for infants born preterm and recognition of the

importance of parent-infant attachment in this vulnerable client group has

1 Bartsand the London NHS Trust, London. resulted in a growing profile of the benefits of adopting family-centred

2 University of South Australia, Adelaide,

care principles in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). However, a

Australia.

3 The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, range of barriers continues to have an impact on the uptake of family-centred

United States. care in this highly complex setting. The aim of this literature review was

to consider this ongoing issue from an occupational performance

Corresponding author: Deanna Gibbs, perspective, through a description of the application of the Person-

Research Consultant – Nursing, Midwifery Environment-Occupation (PEO) Model (Law et al 1996) to support the

and AHP, Healthcare Governance,

provision of family-centred care in the NICU. A significant amount of

Barts and the London NHS Trust, 4th Floor,

John Harrison House, Royal London Hospital, neonatal intensive care research and practice literature is focused on the

London E11BB. viability and survival of the premature infant and on decreasing the

Email: Deanna.Gibbs@bartsandthelondon.nhs.uk potential for neurodevelopmental sequelae. This paper considers the

issues surrounding the admission of an infant to an NICU from a new

Reference: Gibbs D, Boshoff K, Lane A (2010)

occupation-based context and seeks to promote improved understanding of

Understanding parenting occupations in

neonatal intensive care: application of the parental involvement in neonatal intensive care through the consideration

Person-Environment-Occupation Model. of parenting occupations.

British Journal of Occupational Therapy,

73(2), 55-63.

DOI: 10.4276/030802210X12658062793762

Background context

Occupational therapy services in NICU

© The College of Occupational Therapists Ltd.

Occupational therapy has had an emerging role in service provision to

Submitted: 3 December 2008.

premature infants and their families for over 10 years (American Occupational

Accepted: 15 September 2009.

Therapy Association [AOTA] 1993, Gorga 1994, Vergara et al 2006). However,

British Journal of Occupational Therapy February 2010 73(2) 55

Downloaded from bjo.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITE LAVAL on May 4, 2016

Understanding parenting occupations in neonatal intensive care: application of the Person-Environment-Occupation Model

the specific role attributes of occupational therapists working their families. This period has also seen an increasing

within NICUs often differ between facilities and also differ focus on understanding the implications for parents of

between countries. These geographical and facility-based preterm infants during the intensive care admission

inconsistencies in service delivery make this an area of (Lawhon 2002, Browne 2003, Gavey 2007, Howland 2007,

practice within which the occupational therapy role and Thomas 2008), which has served to give more prominence

unique contributions are difficult to articulate to other to the consideration of parental role and support require-

professions in this highly complex setting. ments. Therefore, in addition to knowledge of application

Over the past decade, occupational therapy services and theory regarding infant neurodevelopment, there is

within NICUs in the United States and parts of the United also an opportunity to consider occupational performance

Kingdom have become increasingly established, with as a means of identifying how both parents’ and infants’

clearly defined roles and competencies forming part of the occupational efforts can be supported.

professional literature (Vergara et al 2006). The specific To date, there has been limited exploration of the concept

occupational therapy role attributes within NICUs vary, but of parenting as an occupation as a means of supporting

service provision may include: parental role development within the NICU. Although the

■ Guidance on positioning of infants to support neuro- birth of a preterm infant that requires admission to an NICU

behavioural regulation (for example, habituation to represents a major crisis for parents that may influence the

external stimuli, motor responses and consolidation of acquisition of their parental role and engagement in parent-

and transition between sleep/wake states) and prevent ing occupations, only one study from within the field of

postural sequelae. Supportive positioning helps to occupational therapy has specifically investigated parental

promote infants’ self-regulation of their autonomic and stress within the NICU and the potential influence on

motor systems and reduces the risk of muscle imbalance parent and infant characteristics (Dudek-Shriber 2004).

leading to, for example, shoulder retraction and hip With the study results indicating that the most stressful

external rotation. aspect of having an infant in an NICU is related to altered

■ Assessment and guidance regarding the infant’s neuro- parental role and relationship with their infant, recommen-

behavioural state – this includes key working with parents dations were made for an ongoing focus of the occupational

in understanding their infant’s neurobehavioural cues therapy profession in facilitating a positive parent-infant

and preparing parents for interaction with their infant relationship and providing intervention that focuses on

■ Early identification and implementation of supportive supporting the parents’ occupational role (Dudek-Shriber

practice and /or intervention for infants identified as 2004). Although this research highlights the contribution

at risk of significant neurodevelopmental sequelae (for that supporting parental occupational role performance may

example, intraventricular haemorrhage and periven- have in reducing stress, and facilitating engagement in

tricular leukomalacia, which may lead to motor, sensory their infant’s care, there is still limited understanding and

and cognitive dysfunction) research on how the concept of occupation may be used to

■ Assessment and support of feeding development (within explore and understand parental experiences in the NICU

North America) and what implications this may have for occupational

■ Follow-up assessment and /or intervention for infants therapy practice in this setting.

born below 1000 grams birth weight, before 29 weeks’

gestation or the presence of other risk factors for neuro- Family-centred care

developmental sequelae. In recognition of the importance of parent-infant attachment,

The type and frequency of services provided is often dependent there has been increasing advocacy for the adoption of

on the multidisciplinary team structure within individual principles of family-centred care in the NICU environment

NICUs and on historical role delineation for individual (Harrison 1993, McGrath and Conliffe-Torres 1996, Sweeney

professions within the team. 1997, Hurst 2001, Moore et al 2003). Many neonatal units

During this period, there has also been ongoing discus- have adopted a family-centred approach to caregiving, in

sion in the literature regarding the skills and competencies which promotion of the parent-infant relationship and family

required by therapists working in this area (AOTA 1993, involvement in the infant’s care are of central importance

Hyde and Jonkey 1994, Dewire et al 1996, Hunter 1996, (Franck and Spencer 2003). Johnson et al (1992) have defined

Gorga et al 2000, Vergara et al 2006), resulting in the family-centred care as a philosophy of care, which:

publication of position papers detailing the knowledge and ■ Recognises and respects the crucial role of the family

skills requirements for occupational therapists in neonatal in relation to the infant’s care

intensive care (Vergara et al 2006). For occupational therapists ■ Supports families by building on their strengths and

providing services in an NICU, this suggests the need to encouraging them to make the best choices

establish a balance between acquiring detailed knowledge ■ Promotes normal patterns of living during a child’s

and skills regarding specific assessment and intervention illness and recovery.

practices, gaining an understanding of neonatal health The philosophy of family-centred care provides a contextual

issues and their required management, and consideration base to the increasing focus within the NICU on supporting

of the underlying occupational issues for these infants and the acquisition of parental occupations.

56 British Journal of Occupational Therapy February 2010 73(2)

Downloaded from bjo.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITE LAVAL on May 4, 2016

Deanna Gibbs, Kobie Boshoff and Alison Lane

To facilitate the implementation of family-centred family-centred care principles in the provision of neonatal

care within the NICU, a number of principles have been care. While the barriers to family-centred care provision

identified (Harrison 1993, Hurst 2001). First, family-centred exist, it remains difficult for all NICU-based staff to support

care promotes the encouragement of families to participate parents adequately in the acquisition of the role of parent-

as fully as possible in caring for and making decisions ing. Consideration of this issue through a means that allows

about their hospitalised infants. Second, it ensures respect the multifactorial components to be considered in relation

for the diversity of families and their values and beliefs. to each other is required given the complexity of the factors,

This aims to facilitate the development of supportive care which may constrain or enable the provision of family-centred

partnerships in the NICU and beyond (Hurst 2001, care. Occupational therapists, with their understanding of

Malusky 2005, Griffin 2006). core philosophies regarding occupational performance, are

Despite the adoption of care philosophies that recommend in a key position to explore these multifactorial barriers

the use of family-centred care within the NICU, however, and consider how parental occupational performance can

there are still barriers that limit its uptake. Peterson et al be maximised within this setting.

(2004), in a survey of nurses working in NICUs and pae-

diatric intensive care units (PICUs), identified a discrepancy

between the elements of family-centred care that have Understanding parenting

been acknowledged as essential and the reality of what is

executed in practice. The respondents to this survey

occupations: the Person-

employed in PICUs rated the importance and implemen- Environment-Occupation

tation of elements of family-centred care more highly than

those working in NICUs. However, it was also acknowl-

(PEO) Model

edged that this response is influenced by the realisation The consideration of parenting as an occupational role

that infants are typically admitted to an NICU shortly acquired by the parents of preterm infants within an NICU

after birth and there is a perception that there is, provides a context for exploring the complexities of the

therefore, limited time for them to be integrated into the implementation of family-centred care in this environment.

family structure (Peterson et al 2004). Further, the study Occupation is a core domain for the occupational therapy

recognised that the amount of time that NICU nurses profession. As a result, a number of theoretical paradigms

spend with these fragile infants and the relationships that and frames of reference are in use within the profession to

develop over prolonged lengths of hospitalisation may delineate the complex processes that exist between individuals,

pose a conflict to the implementation of family-centred their roles and occupations, and the environments in which

care (Peterson et al 2004). they take place. The Person-Environment-Occupation (PEO)

Qualitative studies that have explored parental percep- Model (Law et al 1996) was developed as a framework

tions of NICU have also served to identify the inconsistencies within which to examine person-environment processes in

in the adoption of family-centred care practices. Cescuti- the context of occupational therapy practice.

Butler and Galvin (2003), in a grounded theory study, The PEO Model has been used as a tool to examine

determined that parents felt that they had failed to integrate complex occupational performance issues in hospital,

into the NICU during their infant’s admission. They were community, academic and research settings (Strong et al

conscious of an implied burden on staff, identifying feel- 1999). Because of the significant impact that the physical

ings of not belonging in the unit and being especially and social NICU environment has had on the provision

careful of staff and staff routines (Cescuti-Butler and Galvin of family-centred care, the PEO Model was selected for

2003). Sweeney (1997), in a personal reflection on an NICU use to explore parental occupational performance in this

and PICU experience, identified factors through which the environment. Strong et al (1999) described the PEO Model

presence or absence of a family-centred care approach had as providing therapists with a practical, analytical tool to

a significant impact on the family experience. Issues such assist in the analysis of problems in occupational perfor-

as involvement in decision making, the provision of infor- mance, to guide intervention planning and evaluation and

mation to orient families to new environments, experiences to communicate clearly occupational therapy practice.

or available supports, the necessity of a two-way information The PEO Model (Law et al 1996) considers human

exchange, consistency of caregiving (both caregivers and care functioning and learning as a product of complex person,

plans) and basic courtesy were experienced as either enabling environment and occupation interactions. The model is

or constraining, based on the attitudes and actions of the conceptualised as the person and his or her environments

health professionals involved (Sweeney 1997). and occupations interacting dynamically over time (Fig. 1,

There has been significant research on and industry Law et al 1996). Law et al (1996) defined occupations as

acknowledgement of the barriers to the implementation clusters of activities in which individuals engage in order

of family-centred care, and subsequently the support of to meet their intrinsic needs for self-maintenance,

the acquisition of the parental role. However, it remains expression and fulfilment. Occupations are then carried

a multifaceted problem that needs to be addressed in order out within the context of individual roles and capacities,

to ensure greater consistency in the implementation of and multiple environments (Law et al 1996). Occupational

British Journal of Occupational Therapy February 2010 73(2) 57

Downloaded from bjo.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITE LAVAL on May 4, 2016

Understanding parenting occupations in neonatal intensive care: application of the Person-Environment-Occupation Model

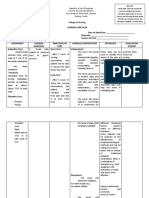

Fig. 1. Person-Environment-Occupation (PEO) Model.* when considering the parents of

preterm infants experiencing care

in an NICU. Person in this context

may relate to both the infant and

the family caregivers, which can

include the mother and father of

the preterm infant, both individ-

ually and as a dyad, in addition

to wider extended family contexts

(for example, the involvement of

siblings or grandparents).

In general terms, preterm

infants have limited capabilities

to tolerate stressful or overstimu-

lating environments and they

typically respond in a disorganised

manner (McGrath and Conliffe-

Torres 1996). In infancy, Whitfield

(2003) described preterm infants

as being generally more difficult

to settle, more irritable, and

having less predictable sleep

patterns and poorer emotional

regulation. They have difficulty

*Source: Law M, Cooper B, Strong S, Stewart D, Rigby P, Letts L (1996) The Person-Environment-Occupation in focusing attention selectively

Model: a transactive approach to occupational performance. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63(1), and are less likely to orient to or

9-23. Reprinted with kind permission of CAOT Publications ACE. spend time exploring novel

stimuli, habituate less efficiently

to visual stimuli, and encode

performance is the outcome of the transaction between the information less efficiently when compared with term-born

person, the environment and the occupation. The extent infants (Whitfield 2003). Therefore, the NICU experience

of the congruence of this transaction is represented by the may be a significant factor disrupting the development of

degree of overlap between the three spheres of the model the infant’s ability to self-regulate his or her autonomic, motor

(Strong et al 1999). and state systems. For example, preterm infants may exhibit

The PEO Model can therefore provide a framework physiological disorganisation (for example, colour change,

within which to consider the acquisition of parenting increased respiratory effort, poor temperature regulation and

occupations in the NICU by understanding the person- disturbed visceral and digestive functioning), difficulties

environment congruence (Law et al 1996). There are a with sustaining relaxed tone and posture, and difficulties

number of interrelated barriers identified in the literature in habituating to their environment (Brazelton and Nugent

that can influence the uptake of family-centred care within 1995). The disruption of self-regulation may result in

the NICU. From these it can be determined that varying subsequent difficulties for parents when trying to establish

factors within an NICU admission may have a constraining opportunities for engaging with their infant.

effect on occupational performance, resulting instead in a Previous studies have also indicated that an infant’s

person-environment incongruence. admission to an NICU can be a period of intense stress for

parents arising from the premature birth and medical

sequelae. Hughes et al (1994), in a phenomenological study,

Occupational analysis of identified common stressors for parents of preterm infants,

including infant appearance, health and course of hospital-

parenting occupations isation, separation from their infant and not feeling like a

From a review of the literature that has explored the uptake of parent, and communication with staff. A qualitative study

family-centred care in NICU, it is apparent that the issues iden- by Wereszczak et al (1997) enabled further identification that

tified within the current body of knowledge can be attributed stress experienced by parents during an NICU admission is

to either a person, environment or occupation factor. attributed to varying sources. These included environmental

stressors such as the infant’s appearance and behaviour,

Person staff behaviour and communication, the sights and sounds

The grounding of the PEO Model in the tenets of client- of the environment and alteration in parental role. Situational

centred care (Strong et al 1999) supports its applicability stressors such as uncertainty, the perception of severity of

58 British Journal of Occupational Therapy February 2010 73(2)

Downloaded from bjo.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITE LAVAL on May 4, 2016

Deanna Gibbs, Kobie Boshoff and Alison Lane

their infant’s illness and prenatal events also contributed Beginning shortly after conception and continuing into

to parent-identified stress within the NICU. childhood, the brain and nervous system experiences a

Dudek-Shriber (2004), in a quantitative study using a period of rapid growth and maturation between 25 and

parental self-report instrument with 162 parents, confirmed 40 weeks’ gestation. For preterm infants, this period of

that the stress experienced by parents during their infant’s development coincides with a time when the infant is

NICU admission may often be diffuse, with a range of factors likely to be exposed to various environmental stressors

contributing to it. However, the results also indicated that that are developmentally inappropriate and potentially

the subscale in which they reported the greatest stress was harmful to the infant’s sensory systems (McGrath and

related to an altered parental role and relationship with Conliffe-Torres 1996).

their baby. In addition, the degree of stress experienced Families also experience the stress of the highly tech-

by parents needs to be considered. For some parents, their nological environment. They encounter life-sustaining

response in the NICU situation has been aligned with post- equipment, monitors, multiple tubes and intravenous lines,

traumatic stress reactions (Holditch-Davis et al 2003). intrusions by multiple caregivers and an overwhelming

Contributing to experiences of parental stress are the limita- fear of the unknown, which can serve to create physical and

tions to the development of situational control, with parents emotional barriers between a preterm infant and his or

wanting and needing to be given opportunities to experience her family (McGrath and Conliffe-Torres 1996, Miles and

a sense of ownership and control within the intensive care Holditch-Davis 1997, Byers 2003). These environmental

unit in relation to their infant rather than remaining on stressors can prove an immediate barrier in enabling

the periphery of his or her care (Fenwick et al 2001). parents to engage readily with their infants.

The parents of preterm infants all present with individ- Supporting parental involvement and promoting family-

ualised experiences, which bring them to a common point centred care approaches can also be significantly influenced

of their infant’s admission to an NICU. So, although by the social environment that exists within the NICU,

guidelines for the implementation of family-centred care particularly in consideration of the relationships between

have been developed, they may not take into account the parents and health care providers in the NICU. Fenwick

journey that these individuals have experienced in becoming et al (2001), in their study involving 28 mothers of pre-

the parent of a preterm infant and, therefore, the need for term infants, described parent-staff interactions as either

the implementation of a care model that supports their facilitative or inhibitive. Staff that provided facilitative

individualised needs as parents and a family. interaction were perceived by mothers as collaborators in

their infant’s care, who provided enhanced opportunities

Environment for them to be with their infants in a meaningful way,

The PEO Model considers the environment as the context such as through participation in routine caregiving and

within which the occupational performance of an individual opportunities for holding their infant; however, staff who

takes place. Environmental contexts are not static and can were perceived as inhibitive displayed behaviours that

have an enabling or constraining effect on occupational restricted maternal efforts to achieve a sense of physical

performance (Law et al 1996). Therefore, the addition of closeness with their infants (Fenwick et al 2001). Conflict

an unanticipated technological environment such as the between parents and staff can result in a variety of parental

NICU, in which occupational role development occurs behaviours as they attempt to regain some control over

may have a significant influence on how the occupation of parenting their infant. These may include vigilance in

parenting is acquired and performed. In this context, the watching over their baby, safeguarding him or her from

environment may include not only the physical aspects of harm, feelings of disaffection as a result of the communi-

the environment, including the design of the unit, lighting cation with staff, a guarding of communication style and a

and medical equipment, but also the staff with which parents fear of reprisals or recrimination if they speak out about

may interact as a key component of that environment. their infant’s care (Lasby et al 1994, Fenwick et al 2001).

The physical environment of the NICU is a significant These studies have begun to explore and articulate commu-

source of stress for preterm infants and their families. The nication styles that facilitate the development of parent-

NICU is a milieu in which infants consistently encounter infant attachment. However, the strategies and recommen-

overwhelming stimuli, including bright lights, loud noises, dations aimed at increasing facilitative interaction are

excessive handling by multiple caregivers and intrusive reported in generalist terms. The transfer of these recom-

and uncomfortable treatment interventions (McGrath and mendations into clear guidelines for practice is not yet

Conliffe-Torres 1996). It involves a barrage of factors for evident (Beveridge et al 2001, Peterson et al 2004).

which the preterm infant is not developmentally prepared. Although research to date has focused predominantly

Factors influencing the infant’s status include illness on parental perceptions of their communication with staff,

severity, noise, light, repetitive pain, exposure to analgesia, a study has also been conducted which investigated health

sedation and other drugs, and separation from normal care staff’s perceptions of the dyadic relationships that are

maternal interaction, including touch, smell, sucking and formed between staff and parents in the NICU. Walker

voice (Whitfield 2003). Prematurity disrupts the normal (1998), in a survey of 298 neonatal nurses, determined that

growth and development of the brain and nervous system. 90% of respondents did not believe that any of the care

British Journal of Occupational Therapy February 2010 73(2) 59

Downloaded from bjo.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITE LAVAL on May 4, 2016

Understanding parenting occupations in neonatal intensive care: application of the Person-Environment-Occupation Model

practices or policies/procedures of the NICU contributed Christiansen (1999) supported the facilitatory influence

to the barriers that confronted parents in the acquisition of occupation on the person, with the suggestion that the

of parenting roles and skills. This indicates that there is performance of occupations is a means of creating and

potential for limitations in understanding the implications maintaining identities. This, therefore, is an important

of staff caregiving practices on parental role acquisition, component to consider in relation to parenting within an

since the aforementioned studies have indicated clearly that NICU. Difficulties exist for parents attempting to consolidate

such an influence exists from the perspective of parents. their self-identity, resulting from limitations in access to

Given that health care staff act as gatekeepers in parents’ their infant and the restrictions that they encounter in

access to their infants in the NICU, the development of a engaging in activities that they anticipated and identified

positive collaborative relationship between parents and as being a parent. Christiansen (1999) introduced the

staff is important in supporting family-centred care. concept of ‘possible selves’. Possible selves are imagined

views of our future identities and give meaning and

Occupation structure to an individual’s thoughts about the future.

Occupation is defined as ‘groups of self-directed, functional This is congruent with parental perceptions of their

tasks and activities in which a person engages over the NICU experience, where they identify the loss of their

lifespan … clusters of activities as tasks in which the person anticipated parenting role (Wereszczak et al 1997); that is,

engages in order to meet his/ her intrinsic needs for self- activities such as feeding, bathing and dressing their

maintenance, expression and fulfilment’ (Law et al 1996, infant that they identified throughout their pregnancy,

p16). The ability to engage in a cluster of activities that are which supported their imagined identity of being a parent,

identifiable as parenting occupations in the NICU may be were not available to them. Hammell (2004) suggested

necessarily limited due to the infant’s fragility and the nature that the loss of the ability to participate in occupations

of the highly intensive care support that he or she is receiving. that are important to individuals can erase perceptions of

The contrast between actual and anticipated parenting capability and competence.

experiences is an additional constraining factor to parental

involvement in the care of an infant. The parents of pre-

term infants have lost many of the usual rituals that are Person-environment-occupation

associated with the birth of a new baby, such as leaving

hospital with the baby and receiving congratulations on transactions in an NICU:

the baby’s birth. Lasby et al (1994) identified that the loss implications for practice

of these expected maternal events make it difficult to gain

acknowledgement of motherhood, which creates difficulty In considering the rich information currently available

in the establishment of meaningful moments between that delineates the person, environment and occupation

parent and infant. Findlay (1997), in her discussion of aspects of the NICU experience for preterm infants and

the adaptation process experienced by parents of preterm their families, the PEO Model can be used to consider

infants, includes descriptions of parental experience of how the development of occupational performance can

pregnancies ending prematurely and the commencement of be facilitated. By exploring the transactions that may

a process of adjusting to unanticipated situations. Parents of occur between each aspect of the model, focusing on the

preterm infants are subsequently required to develop their person-occupation, occupation-environment and person-

parenting skills in the very public domain of the NICU. This, environment relationships (Strong et al 1999), it may be

in itself, may be problematic due to the acknowledged possible for occupational therapists to identify strategies

barriers that exist to parenting in the NICU, such as the that could serve to overcome the barriers and support

physical environment, the mismatch between parents and optimal occupational performance when working with

their infant in terms of readiness for interaction, the individual families.

inability to provide all of their infant’s caregiving, and Occupational therapy as a profession is concerned with

the support of staff regarding parental competence in assisting individuals to participate in the chosen occupations

caregiving (Gale and Franck 1998). that are necessary for health, development and quality of

Miles and Holditch-Davis (1997), in their development life (Parham and Primeau 1997). In the critical care

of a conceptual framework relating to the needs of parents context of an NICU, this perspective can be diminished in

in an NICU, identified that the loss of the anticipated importance owing to the primary focus on components of

parental or caregiving role can leave parents with feelings infant functioning and survival. Opportunities exist to

of helplessness, struggling for opportunities in which to determine how both the infants’ and parents’ occupational

exert their parental role. This framework was confirmed efforts can be enabled and supported (Holloway 1998).

in a subsequent study, in which 25 of 31 mothers who The areas of PEO transactions would serve as a starting

participated in the study reported that their loss of the point for exploring how parental occupational performance

anticipated role contributed to difficulties in developing within the NICU context may be enabled.

positions as advocates and decision makers on behalf of The application of the PEO Model in relation to the

their children (Holditch-Davis and Miles 2000). context of parenting in the NICU is illustrated in Fig. 2.

60 British Journal of Occupational Therapy February 2010 73(2)

Downloaded from bjo.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITE LAVAL on May 4, 2016

Deanna Gibbs, Kobie Boshoff and Alison Lane

Fig. 2. Analysis of the potential person-environment-occupation transactions in NICU.* can be a significant barrier to

occupational engagement. When

planning care, consideration

also needs to be given to:

■ The availability of opportuni-

ties for parents to be engaged

in caregiving activities

■ Parents’ fear about being

involved in the care of their

infant and not wishing to

harm their baby

■ Parents’ previous experience

and confidence in the perfor-

mance of caregiving activities,

such as bathing and feeding,

and how these can be best

enabled.

Supporting parental

occupational adaptation

Within each of the elements of

person, environment and occupa-

tion, barriers exist that are diffi-

cult to remediate. For example,

NICU = neonatal intensive care unit. depending on the structure and

*Source: Adapted from: Strong S, Rigby P, Stewart D, Law M, Letts L, Cooper B (1999) Application of operational functioning of an

the Person-Environment-Occupation Model: a practical tool. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, NICU, the moderation of some

66(3), 122-33. Adapted and reprinted with kind permission from CAOT Publications ACE. environment factors, such as

unit design and lighting policies,

may be limited. However, bedside

Occupation-environment transactions factors, such as the management of incubator covers, alarms

Within the NICU, occupation-environment transactions are and voice level, are able to be moderated through collaborative

clearly evident. As a result of the intensive medical support staff efforts. Similarly, the types of medical and technological

required by the infant, occupational engagement will be intervention required to support the infant are beyond the

limited by the physical barriers of medical equipment in control of the occupational therapist. However, what can

the unit, such as the infant being ventilated or nursed in be considered is how best to support parents’ occupational

an incubator. As outlined earlier, the social environment adaptation to this environment. Providing an intervention

of the NICU may also have an impact on the fluency of approach that includes consistent and understandable

occupation-environment transactions. explanations regarding equipment function, clearly identifying

and making available opportunities for parents to participate

Person-environment transactions in safe but meaningful contact with their infants, and

Person-environment transactions can also be present. equipping parents to interpret their infants’ state regulation

These can include the local visiting hours and regulations in relation to timeliness of interaction can all have a positive

for the unit that may inhibit parents’ participation in care- effect on the person-environment transaction and, ultimately,

giving activities. Owing to the tertiary nature of NICUs, the parents’ occupational role development.

many infants are admitted to units that are geographically The development of evidence-based neonatal care

distant to their parents’ home, making regular visiting approaches, such as the Newborn Individualised Develop-

difficult. Within the social environment, consideration mental Care and Assessment Programme (NIDCAP) (Lawhon

needs to be given to the support provided by NICU staff 2002, Als 2008), has been key in supporting multidiscipli-

for parents to assume a caregiving role for their infants. nary NICU-based staff in the provision of a highly individ-

This includes the communication style undertaken by ualised developmentally supportive care approach for

health care providers and whether this is perceived by preterm infants. The aim of individualised developmentally

parents as facilitative or inhibitive. supportive care models, such as NIDCAP, is to alter the

focus of neonatal care from the traditional task-oriented or

Person-occupation transactions procedure-oriented approach to a focus on processes and

Within the person-occupation transactional area, the manage- relationships, including the increased involvement of

ment of the infant’s fragile medical status during caregiving families (Westrup 2007). The NIDCAP approach is based

British Journal of Occupational Therapy February 2010 73(2) 61

Downloaded from bjo.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITE LAVAL on May 4, 2016

Understanding parenting occupations in neonatal intensive care: application of the Person-Environment-Occupation Model

on the premise that infants’ own behaviour provides the

necessary information in order to determine their current Key findings

capabilities. It is a comprehensive programme, involving ■ The PEO Model provides a structure for considering parenting

structured behavioural observation of the infant and the occupations in the NICU.

provision of individualised caregiving support of the infant’s ■ The use of an occupation-focused approach in the NICU ensures that

developmental goals (VandenBerg 2007). The ongoing both the preterm infant and his or her family’s needs are recognised

process of NIDCAP supports continual adjustment of the and addressed.

environment and caregiving practices in light of the infant’s

and parents’ developmental needs (VandenBerg 2007). What the study has added

NICUs that have adopted a NIDCAP approach are more This review provides an understanding of parental occupations in NICUs

able not only to be truly responsive to the needs of infants and supports occupational therapists in their promotion of family-centred

with a resulting impact on developmental outcome but also care in this setting.

to centralise the role of an infant’s family and address the

PEO transactions inherent in the NICU admission. Successful

implementation of individualised developmental care requires AOTA. Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Taskforce (1993) Knowledge and skills

the full commitment of NICU staff at all levels and provides for occupational therapy practice in the neonatal intensive care unit.

a significant shift in how health services address the needs of American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 47(12), 1100-05.

this client group (VandenBerg 2007, Westrup 2007). However, Beveridge J, Bodnaryk K, Ramahandran C (2001) Family-centred care in

like family-centred care, the uptake of NIDCAP and other the NICU. Canadian Nurse, 97(3), 14-18.

developmental care approaches has remained inconsistent. Brazelton TB, Nugent JK (1995) The Neonatal Behavioural Assessment Scale.

The PEO Model provides a structure through which an 3rd ed. Clinics in Developmental Medicine No. 137. London: Mac Keith Press.

understanding of how each infant and his or her family Browne JV (2003) New perspectives on premature infants and their parents.

accommodates to the NICU experience can be achieved Zero to Three, November, 4-12.

and, more specifically, can be used to direct occupational Byers JF (2003) Components of developmental care and the evidence for their

therapy practice in focusing on family-centred care and use in the NICU. American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing, 28(3), 174-82.

the development of occupational performance. Therefore, Cescuti-Butler L, Galvin K (2003) Parents’ perceptions of staff competency in

although the types of occupational therapy intervention a neonatal intensive care unit. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 12, 752-61.

outlined at the beginning of this paper are a key element of Christiansen C (1999) Defining lives: occupation as identity: an essay on

neonatal service provision, the use of an occupation-based competence, coherence and the creation of meaning. American Journal

approach can provide a means through which practice can of Occupational Therapy, 53(6), 547-58.

be enhanced by ensuring that both the infant’s and the Dewire A, White D, Kanny E, Glass R (1996) Education and training of

family’s needs are recognised and addressed. occupational therapists for neonatal intensive care units. American

Journal of Occupational Therrapy, 50(7), 486-94.

Dudek-Shriber L (2004) Parent stress in the neonatal intensive care unit

and the influence of parent and infant characteristics. American Journal

Conclusion of Occupational Therapy, 58(5), 509-20.

The consideration of parenting as an occupational role for Fenwick J, Barclay L, Schmied V (2001) Struggling to mother: a consequence

the parents of preterm infants within an NICU would appear of inhibitive nursing interactions in the neonatal nursery. Journal of

to allow the emergence of an understanding of the person- Perinatal and Neonatal Nursing, 15(2), 49-64.

environment influences on occupational performance. By Findlay MP (1997) Parenting a hospitalised preterm infant: a phenomenological

improving understanding of the parental occupations in study. (Unpublished PhD thesis.) Birmingham, AL: University of Alabama

the NICU, the provision of facilitatory or enabling service at Birmingham.

frameworks may be considered. As outlined, the PEO Model Franck LS, Spencer C (2003) Parent visiting and participation in infant

may therefore provide a new and systematic means of caregiving activities in a neonatal unit. Birth, 30(1), 31-35.

addressing an ongoing issue in the care of preterm infants Gale G, Franck LS (1998) Toward a standard of care for parents of infants

and their families. Through the use of this approach, in the neonatal intensive care unit. Critical Care Nurse, 18(5), 62-74.

occupational therapists working within NICU environments Gavey N (2007) Parental perceptions of neonatal care. Journal of Neonatal

have the potential both to support significantly the use of Nursing, 13, 199-206.

family-centred care approaches and to promote occupational Gorga D (1994) The evolution of occupational therapy practice for infants

adaptation with the parents of preterm infants. in the neonatal intensive care unit. American Journal of Occupational

Therapy, 48(6), 487-89.

References Gorga D, Anzalone M, Holloway E, Bigsby R, Hunter J, Strzyzewski S,

Als H (2008) Assessing preterm infants’ behaviour and providing individualised Vergara E (2000) Specialised knowledge and skills for occupational

developmental care: introduction to APIB and NIDCAP. In: Contemporary therapy practice in the neonatal intensive care unit. American Journal

Forums. Developmental Interventions in Neonatal Care. 24th annual of Occupational Therapy, 54(6), 641-48.

conference. 2-4 October 2008, Denver, USA. Conference Guide. Dublin, Griffin T (2006) Family-centred care in the NICU. Journal of Perinatal and

CA: Contemporary Forums, 54. Neonatal Nursing, 20(1), 98-102.

62 British Journal of Occupational Therapy February 2010 73(2)

Downloaded from bjo.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITE LAVAL on May 4, 2016

Deanna Gibbs, Kobie Boshoff and Alison Lane

Hammell KW (2004) Dimensions of meaning in the occupations of daily life. Malusky SK (2005) A concept analysis of family-centred care in the NICU.

Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71(5), 296-305. Neonatal Network, 24(6), 25-32.

Harrison H (1993) The principles of family-centred neonatal care. Pediatrics, McGrath JM, Conliffe-Torres S (1996) Integrating family-centred developmental

92(5), 643-50. assessment and intervention into routine care in the neonatal intensive

Holditch-Davis D, Miles MS (2000) Mothers’ stories about their experiences care unit. Nursing Clinics of North America, 31(2), 367-86.

in the neonatal intensive care unit. Neonatal Network, 19(3), 13-21. Miles MS, Holditch-Davis D (1997) Parenting the prematurely born infant:

Holditch-Davis D, Bartlett R, Blickman AK, Miles MS (2003) Post-traumatic pathways of influence. Seminars in Perinatology, 21(3), 254-66.

stress symptoms on mothers of premature infants. Journal of Obstetric, Moore KAC, Coker K, DuBuisson AB, Swett B, Edwards WH (2003) Implementing

Gynaecological and Neonatal Nursing, 32(2), 161-71. potentially better practices for improving family-centred care in neonatal

Holloway E (1998) Relationship-based occupational therapy in the neonatal intensive care units: successes and challenges. Pediatrics, 111(4), 450-60.

intensive care unit. In: J Case-Smith, ed. Paediatric occupational therapy Parham LD, Primeau L (1997) Play and occupational therapy. In: LD Parham,

and early intervention. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann, 111-26. LS Fazio, eds. Play in occupational therapy. New York: Mosby, 2-21.

Howland LC (2007) Preterm birth: implications for family stress and coping. Peterson MF, Cohen J, Parsons V (2004) Family-centred care: do we practice

Newborn and Infant Nursing Reviews, 7(1), 14-19. what we preach? Journal of Obstetric, Gynaecological and Neonatal

Hughes M, McCollum J, Sheftel D, Sanchez G (1994) How parents cope Nursing, 33, 421-27.

with the experience of neonatal intensive care. Children’s Health Care, Strong S, Rigby P, Stewart D, Law M, Letts L, Cooper B (1999) Application

23(1), 1-14. of the Person-Environment-Occupation Model: a practical tool. Canadian

Hunter J (1996) Clinical interpretation of ‘education and training of Journal of Occupational Therapy, 66(3), 122-33.

occupational therapists for neonatal intensive care units’. American Sweeney MM (1997) The value of a family-centred approach in the NICU

Journal of Occupational Therapy, 50(7), 495-503. and PICU: one family’s perspective. Pediatric Nursing, 23(1), 64-66.

Hurst I (2001) Vigilant watching over: mother’s actions to safeguard their Thomas LM (2008) The changing role of parents in neonatal care: a historical

premature babies in the newborn intensive care nursery. Journal of review. Neonatal Network, 27(2), 91-100.

Perinatal and Neonatal Nursing, 15(3), 39-57. VandenBerg KA (2007) Individualised developmental care for high risk

Hyde AS, Jonkey BW (1994) Developing competency in the neonatal intensive newborns in the NICU: a practice guideline. Early Human Development,

care unit: a hospital training program. American Journal of Occupational 83(7), 433-42.

Therapy, 48(6), 539-45. Vergara E, Anzalone M, Bigsby R, Gorga D, Holloway E, Hunter J, Laadt G,

Johnson BH, Jeppson ES, Redburn L (1992) Caring for children and families: Strzyewski S, 2005 Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Taskforce (2006) Specialized

guidelines for hospitals. Bethesda, MD: Association for the Care of knowledge and skills for occupational therapy practice in the neonatal

Children’s Health. intensive care unit. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 60(6), 659-68.

Lasby K, Newton S, Sherrow T, Stainton MC, McNeill D (1994) Maternal work Walker SB (1998) Neonatal nurses’ views on the barriers to parenting in the

in the NICU: a case-study of an ‘NICU-experienced’ mother. Issues in intensive care nursery – a national study. Australian Critical Care, 11(3),

Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 17, 147-60. 86-91.

Law M, Cooper B, Strong S, Stewart D, Rigby P, Letts L (1996) The Wereszczak J, Miles MS, Holditch-Davis D (1997) Maternal recall of the

Person-Environment-Occupation Model: a transactive approach to neonatal intensive care unit. Neonatal Network, 16(4), 33-40.

occupational performance. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, Westrup B (2007) Newborn Individualised Developmental Care and

63(1), 9-23. Assessment Program (NIDCAP) – family-centered developmentally

Lawhon G (2002) Facilitation of parenting the premature infant within the supportive care. Early Human Development, 83(7), 443-49.

newborn intensive care unit. Journal of Perinatal and Neonatal Nursing, Whitfield MF (2003) Psychosocial effects of intensive care on infants and

16(1), 71-82. families after discharge. Seminars in Neonatology, 8, 185-93.

British Journal of Occupational Therapy February 2010 73(2) 63

Downloaded from bjo.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITE LAVAL on May 4, 2016

You might also like

- Drench .Psychosocial Aspects of Health Care - Meredith E. Drench, Ann Noonan, Nancy Sharby, Susan Hallenborg Ventura.2003Document361 pagesDrench .Psychosocial Aspects of Health Care - Meredith E. Drench, Ann Noonan, Nancy Sharby, Susan Hallenborg Ventura.2003편임백75% (4)

- Early Childhood DevelopmentDocument57 pagesEarly Childhood DevelopmentSurayaEksteenNo ratings yet

- Theory Parent-Child InterectionDocument19 pagesTheory Parent-Child InterectionBheru LalNo ratings yet

- Vergara, J. - T.O. in The Neonatal Intensive Care UnitDocument11 pagesVergara, J. - T.O. in The Neonatal Intensive Care UnitFedora Margarita Santander CeronNo ratings yet

- AOTA Statement On Role of OT in NICUDocument9 pagesAOTA Statement On Role of OT in NICUMapi RuizNo ratings yet

- Health and Social Care UkDocument5 pagesHealth and Social Care UkAkular AyramNo ratings yet

- Focal Paper Jimenez 1Document9 pagesFocal Paper Jimenez 1Lea BahioNo ratings yet

- Expert Intrapartum Maternity Care: A Meta-Synthesis: ReviewpaperDocument14 pagesExpert Intrapartum Maternity Care: A Meta-Synthesis: ReviewpaperNines RíosNo ratings yet

- The Congruence of Nurses' Performance With Developmental Care Standards in Neonatal Intensive Care UnitsDocument11 pagesThe Congruence of Nurses' Performance With Developmental Care Standards in Neonatal Intensive Care UnitsWiwit ClimberNo ratings yet

- A Call To Reexamine Quality of Life Through Relationship-Based FeedingDocument7 pagesA Call To Reexamine Quality of Life Through Relationship-Based FeedingLauraNo ratings yet

- Children: Nursing Perspective of The Humanized Care of The Neonate and Family: A Systematic ReviewDocument19 pagesChildren: Nursing Perspective of The Humanized Care of The Neonate and Family: A Systematic ReviewMacarena Cortes CarvalloNo ratings yet

- Family Centere Care Di NICUDocument11 pagesFamily Centere Care Di NICUNeni SiraitNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1355184121001769 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S1355184121001769 MainIrene RubioNo ratings yet

- Supporting Children With SEN An Introduction To A 3 Tiered School Based OT Model of Service Delivery in WFOT Bulletin 2017Document11 pagesSupporting Children With SEN An Introduction To A 3 Tiered School Based OT Model of Service Delivery in WFOT Bulletin 2017Shan Shan LuiNo ratings yet

- Nyqvist 2009Document11 pagesNyqvist 2009VanessaNo ratings yet

- The Neonatal Intensive Parenting Unit: An Introduction: State-Of-The-ArtDocument6 pagesThe Neonatal Intensive Parenting Unit: An Introduction: State-Of-The-ArtathayafebNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Parent Delivered Therapy Interventions in Children With Cerebral Palsy: A Qualitative Synthesis and ChecklistDocument11 pagesDeterminants of Parent Delivered Therapy Interventions in Children With Cerebral Palsy: A Qualitative Synthesis and Checklistying reenNo ratings yet

- Benefícios Da Massagem Pados2019Document7 pagesBenefícios Da Massagem Pados2019Adlla JamilyNo ratings yet

- In The: Evidence ForDocument7 pagesIn The: Evidence FormustafasacarNo ratings yet

- Learning To Nurse ChildrenDocument11 pagesLearning To Nurse ChildrenBeatrizNo ratings yet

- Jones PUB729Document24 pagesJones PUB729Patrick SanchezNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0266613813002192 MainDocument11 pages1 s2.0 S0266613813002192 Mainnengsi susantiNo ratings yet

- Anwarsiani2017 ReviewDocument9 pagesAnwarsiani2017 Reviewmariasol63No ratings yet

- 2 Nursing TheoriesDocument1 page2 Nursing TheoriesJhenjo KangNo ratings yet

- Exploring The Impact of A Dual Occupancy Neonatal Intensive Care Unit On Staff Work Ow, Activity, and Their PerceptionsDocument12 pagesExploring The Impact of A Dual Occupancy Neonatal Intensive Care Unit On Staff Work Ow, Activity, and Their PerceptionsManahel IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Thesis Katya Kirkland Most Up To DateDocument31 pagesThesis Katya Kirkland Most Up To Dateapi-643862582No ratings yet

- Supporting The Transition To Parenthood: Development of A Group Health-Promoting ProgrammeDocument11 pagesSupporting The Transition To Parenthood: Development of A Group Health-Promoting ProgrammeIonela BogdanNo ratings yet

- Rustin 1998Document21 pagesRustin 1998Miguel EspinosaNo ratings yet

- 2013NCCWeisEnhancingperson CentredcommunicationDocument13 pages2013NCCWeisEnhancingperson CentredcommunicationDiulia SantanaNo ratings yet

- Assignment No. 1: Module 1: Framework For Maternal and Child Health NursingDocument11 pagesAssignment No. 1: Module 1: Framework For Maternal and Child Health NursingAna LuisaNo ratings yet

- A Clinical CareographyDocument11 pagesA Clinical CareographyPAULA ANDREA VARGAS MONCADANo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: Implementing Evidence-Based Practice in Residential Care - How Far Have We Come?Document19 pagesHHS Public Access: Implementing Evidence-Based Practice in Residential Care - How Far Have We Come?André MatosNo ratings yet

- Recommendations For Involving The Family in Developmental Care of The NICU BabyDocument4 pagesRecommendations For Involving The Family in Developmental Care of The NICU BabyAgus SuNo ratings yet

- The Theory-Practice Gap - Impact of Professional-Bureaucratic Work Conflict On Newly Qualified NursesDocument13 pagesThe Theory-Practice Gap - Impact of Professional-Bureaucratic Work Conflict On Newly Qualified Nursesapi-3701957100% (1)

- Article 5 (Module1researchact)Document13 pagesArticle 5 (Module1researchact)Clint NavarroNo ratings yet

- The Guidelines Regarding PuerpDocument8 pagesThe Guidelines Regarding Puerpdyah ayu noer fadilaNo ratings yet

- A Qualitative Study: Implementation of Neonatal Developmental CareDocument7 pagesA Qualitative Study: Implementation of Neonatal Developmental Careputri wahyuningtyasNo ratings yet

- Funciones Actuales y Necesidades Continuas de Los Patólogos Del Habla y El Lenguaje Que Trabajan en Unidades de Cuidados Intensivos NeonatalesDocument13 pagesFunciones Actuales y Necesidades Continuas de Los Patólogos Del Habla y El Lenguaje Que Trabajan en Unidades de Cuidados Intensivos NeonatalesingridspulerNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Halimahtun SaadiahDocument7 pagesJurnal Halimahtun SaadiahRosy OktaridaNo ratings yet

- Stress and Social Support Among Registered Nurses in A Level II NICUDocument5 pagesStress and Social Support Among Registered Nurses in A Level II NICUAdrian KmeťNo ratings yet

- Care Planning in Children and Young People's Nursing: John Wiley & Sons, IncorporatedDocument5 pagesCare Planning in Children and Young People's Nursing: John Wiley & Sons, IncorporatedArnie Dela cruzNo ratings yet

- Introduction EditedDocument5 pagesIntroduction EditedCj HufanaNo ratings yet

- Building Midwifery Educator Capacity Using International Partnerships - Findings From A Qualitative StudyDocument8 pagesBuilding Midwifery Educator Capacity Using International Partnerships - Findings From A Qualitative StudyAlvina FelishaNo ratings yet

- Artigo 14 - Copca PDFDocument9 pagesArtigo 14 - Copca PDFAna paula CamargoNo ratings yet

- Articulo Cuidado de Enfermeria. ParcialDocument5 pagesArticulo Cuidado de Enfermeria. ParcialSara Muñoz MartínezNo ratings yet

- A Review of The Breastfeeding Literature Relevant To Osteopathic PracticeDocument6 pagesA Review of The Breastfeeding Literature Relevant To Osteopathic PracticeYesenia PaisNo ratings yet

- 9010-Article Text-27725-1-10-20200225Document12 pages9010-Article Text-27725-1-10-20200225cukana ditaNo ratings yet

- The Effect and Implication of Developmental Supportive Care Practices in Preterm BabiesDocument23 pagesThe Effect and Implication of Developmental Supportive Care Practices in Preterm BabiesInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology100% (1)

- A Qualitative Interpretive Study Exploring Parents' Perception of The Parental Role in The Paediatric Intensive Care UnitDocument8 pagesA Qualitative Interpretive Study Exploring Parents' Perception of The Parental Role in The Paediatric Intensive Care UnitCoolNo ratings yet

- Family Centred Care Literature ReviewDocument6 pagesFamily Centred Care Literature Reviewc5pgcqzv100% (1)

- Browne 2011Document11 pagesBrowne 2011Gisele Elise MeninNo ratings yet

- Mother and Child Integrative Developmental Care Model - A Simple Approach To A Complex PopulationDocument4 pagesMother and Child Integrative Developmental Care Model - A Simple Approach To A Complex PopulationMaria Del Mar Marulanda GrizalesNo ratings yet

- Article Text 399927 1 10 20170308 1Document6 pagesArticle Text 399927 1 10 20170308 1Claire De VeraNo ratings yet

- Journal of Family Nursing-2002-Bruce-408-29Document23 pagesJournal of Family Nursing-2002-Bruce-408-29Meris dawatiNo ratings yet

- A New Model of Father Support To PromoteDocument5 pagesA New Model of Father Support To PromotejesikaNo ratings yet

- Care of Mother, Child, AdolescentsDocument38 pagesCare of Mother, Child, AdolescentsAN1 M3No ratings yet

- Literature Evaluation Table: Student Name Lecturers Name Institution Course DateDocument7 pagesLiterature Evaluation Table: Student Name Lecturers Name Institution Course DateTony MutisyaNo ratings yet

- JNL 51 Final Midwiferypracticearrangementswhichsustain Article 2Document7 pagesJNL 51 Final Midwiferypracticearrangementswhichsustain Article 2Delsy NurrizmaNo ratings yet

- Articulo YBlanchard 2015Document6 pagesArticulo YBlanchard 2015Mariana MurciaNo ratings yet

- Apply A Conceptual Framework Focused On Advanced Nursing RolesDocument7 pagesApply A Conceptual Framework Focused On Advanced Nursing RolesBrian MaingiNo ratings yet

- Children and Youth Services Review: Mairead Furlong, Fergal Mcloughlin, Sinead McgillowayDocument11 pagesChildren and Youth Services Review: Mairead Furlong, Fergal Mcloughlin, Sinead McgillowayTere OliverosNo ratings yet

- MCN MidtermsDocument48 pagesMCN MidtermsAng, Rico GabrielNo ratings yet

- Perinatal Palliative Care: A Clinical GuideFrom EverandPerinatal Palliative Care: A Clinical GuideErin M. Denney-KoelschNo ratings yet

- Primary Admissions Brochure 201112Document76 pagesPrimary Admissions Brochure 201112robcannonNo ratings yet

- Telligence Nurse Call BrochureDocument6 pagesTelligence Nurse Call BrochureCarlos Fernando TixiNo ratings yet

- Coping With Chronic Illness FinalDocument24 pagesCoping With Chronic Illness FinalNadiaNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of Problem Solving Therapy For Spouses of Men With Prostate Cancer - A Randomized Controlled Trial-2018Document9 pagesEfficacy of Problem Solving Therapy For Spouses of Men With Prostate Cancer - A Randomized Controlled Trial-2018Juan ParedesNo ratings yet

- C and F SW ArticleDocument12 pagesC and F SW ArticleRadu DanielaNo ratings yet

- National Patient Safety GoalsDocument5 pagesNational Patient Safety GoalsMariam AbedNo ratings yet

- Editorial Writing Sample (English)Document3 pagesEditorial Writing Sample (English)Rey Bryan BiongNo ratings yet

- CV - Sangeeta BhatiaDocument9 pagesCV - Sangeeta BhatiaMadhu DatarNo ratings yet

- Men's Essential Roles in The Management of Sickle Cell AnemiaDocument10 pagesMen's Essential Roles in The Management of Sickle Cell AnemiaKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNo ratings yet

- Obesity Obesity Management in AdultsDocument11 pagesObesity Obesity Management in AdultsKuroo HazamaNo ratings yet

- Nursing Diagnoses Arranged by GordonDocument9 pagesNursing Diagnoses Arranged by GordonJoedeson Aroco BungubungNo ratings yet

- Tle 10 Module Q3 Sy 2021-22 PDFDocument20 pagesTle 10 Module Q3 Sy 2021-22 PDFEdgar RazonaNo ratings yet

- TimelineDocument40 pagesTimelineangsana mNo ratings yet

- SP2 Child Full Assessment and Planning Report SampleDocument8 pagesSP2 Child Full Assessment and Planning Report SampleBelen SorianoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Mental Health PowerpointDocument11 pagesIntroduction To Mental Health PowerpointWinner GirlNo ratings yet

- Bahan Conduct 3Document9 pagesBahan Conduct 3Duvi Ahmad Duvi DekanNo ratings yet

- IMCI Session 2 - An Overview of The IMCIDocument37 pagesIMCI Session 2 - An Overview of The IMCIsarguss14100% (3)

- St. John The Baptist Parochial School: Taytay, RizalDocument37 pagesSt. John The Baptist Parochial School: Taytay, RizalHannah Francesca Sarajan EstrellaNo ratings yet

- Nurturing Care Components 2Document1 pageNurturing Care Components 2Jeff WigginsNo ratings yet

- Equal Opportunities DocumentDocument4 pagesEqual Opportunities DocumentGareth CotterNo ratings yet

- Subra's PortfolioDocument3 pagesSubra's PortfolioSubra SeNo ratings yet

- RMO Orientation AIRMEDDocument130 pagesRMO Orientation AIRMEDqueenartemisNo ratings yet

- No Health Without Mental HealthDocument103 pagesNo Health Without Mental HealthJon BeechNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Cavite State University Don Severino Delas Alas Campus Indang, CaviteDocument6 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Cavite State University Don Severino Delas Alas Campus Indang, CaviteYellowNo ratings yet

- CMS MLN Cognitive Assessment and Care Plan Services CPT Code 99483Document4 pagesCMS MLN Cognitive Assessment and Care Plan Services CPT Code 99483Salomon GreenNo ratings yet

- ECD Checklist ManualDocument22 pagesECD Checklist ManualRussel BrondialNo ratings yet

- IWA Draft For Review at Tokyo MeetingDocument47 pagesIWA Draft For Review at Tokyo MeetingParrex ParraNo ratings yet