Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Tan HumanCapitalTheory 2014

Uploaded by

JOSUE ISMAEL GUZMAN ROJASOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Tan HumanCapitalTheory 2014

Uploaded by

JOSUE ISMAEL GUZMAN ROJASCopyright:

Available Formats

Human Capital Theory: A Holistic Criticism

Author(s): Emrullah Tan

Source: Review of Educational Research , September 2014, Vol. 84, No. 3 (September

2014), pp. 411-445

Published by: American Educational Research Association

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24434243

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

American Educational Research Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to Review of Educational Research

This content downloaded from

54.189.126.232 on Sat, 30 Mar 2024 01:07:19 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Review of Educational Research

September 2014, Vol. 84, No. 3, pp. 411-445

DOI: 10.3102/0034654314532696

© 2014 AERA, http://rer.aera.net

Human Capital Theory: A Holistic Criticism

Emrullah Tan

University of Exeter Business School

Human capital theory has had a profound impact on a range of disciplines

from economics to education and sociology. The theory has always been the

subject of bitter criticisms from the very beginning, but it has comfortably

survived and expanded its influence over other research disciplines. Not sur

prisingly, a considerable number of criticisms have been made as a reaction

to this expansion. However, it seems that these criticisms are rather frag

mented and disorganized. To bridge this gap and organize them in a system

atic way, the present article takes a holistic approach and reviews human

capital theoryfrom four comprehensive perspectives focusing on the method

ological, empirical, practical, and moral aspects of the theory.

Keywords: human capital, neoclassical economics, rational choice theory

Human capital theory (HCT) is not a mere theory in economics. It is a compre

hensive approach to analyze a wide spectrum of human affairs in light of a par

ticular mindset and propose policies accordingly. Education, in this approach, is

placed at the center and considered the source of economic development. For this

reason, it has been sharply criticized by educators, economists, sociologists, and

philosophers. There is a great deal of criticisms about it; however, they are rather

dispersed and disorganized. To organize these diverse criticisms systematically

will enable us to see the bigger picture as well as the impact of HCT on education

and politics. Therefore, the article reviews the major criticisms of HCT from four

different perspectives. To our best knowledge, this is the first attempt to unify a

variety of criticisms of the theory in a single article. It is also worth noting that

half a century has passed from the first publication of the book Human Capital by

Gary Becker in 1964. In that sense, it would also be timely to review HCT and its

outcomes in this long period.

The aims of this article are twofold. The first aim is to provide a clear under

standing of HCT and its roots. To achieve this, we will go back to the philosophi

cal origin of the theory and discuss the school of thought from which HCT takes

its intellectual nutrition. To understand the roles of education in HCT, it is neces

sary to trace back the basic assumptions of this intellectual tradition on human

beings. The second aim is to provide a comprehensive and accessible road map to

those who wish to have a broad understanding of the theory and its impacts. With

411

This content downloaded from

54.189.126.232 on Sat, 30 Mar 2024 01:07:19 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Tan

this article, it is hoped that the readers will have the opportunity to review the

major criticisms and different dimensions of the theory in a single article.

In accordance with these goals, the article is divided into six parts. First, HCT

is briefly outlined. Second, the methodological criticism of this school of thought

will be made in reference to its core paradigms. Third, the theory is examined in

the lights of empirical studies and competing theories to explore whether the the

ory and empirical data are in tune with each other. Fourth, the practical conse

quences of this theory regarding education policies will be evaluated. Fifth, the

moral criticism of the theory will be made. Finally, a number of conclusions will

be drawn based on these critiques.

The Theory Outlined

Human capital is defined as "productive wealth embodied in labor, skills and

knowledge" (OECD, 2001) and it refers to any stock of knowledge or the innate/

acquired characteristics a person has that contributes to his or her economic pro

ductivity (Garibaldi, 2006). In essence, HCT suggests that education increases the

productivity and earnings of individuals; therefore, education is an investment. In

fact, this investment is not only crucial for individuals but it is also the key to the

economic growth of a country. As Alfred Marshall (1920) put it, "The most valu

able of all capital is that invested in human beings" (p. 564).

The term human capital has a long but discontinuous history (Kiker, 1966). It,

however, was formally introduced in the 1950s and its analytical framework was

developed mostly by academicians at Chicago School of Economics such as

Theodore Schultz and Gary Becker. At that time, the term human capital was

severely criticized by some liberal academicians due to its negative connotations

with slavery. In fact, even before the 20th century, the liberal philosopher J. S Mill

(1806-1873) criticized it and noted that "the human being himself. ... I do not

class as wealth. He is the purpose for which wealth exists" (Mill, 1909, p. 47). The

human capital theorist Schultz (1959) referred to these liberals as sentimentalists:

those who argued that treating human beings as if they were a commodity or

machinery could lead to the justification for slavery. At that period of time, this

issue was so sensitive in the United States that even Becker (1993a) himself later

acknowledged that he was rather hesitant for the title of his book, Human Capital,

when he was about to publish it because he was afraid of the potential severe criti

cisms by the liberals. To his surprise, the once bitterly criticized concept has

become one of the most popular topics in economics and even led him to the

Nobel Prize in 1992. Furthermore, the concept has been widely used as an instru

ment to shape educational policies in many countries. It should be noted that

human capital is not only limited to education and training, it is an extensive

concept and covers many areas from health to migration. But the scope of this

article is confined to education.

HCT derives from the neoclassical school of thought in economics. Therefore,

to have a clear and complete picture of it, we need to understand the neoclassical

economic model and its basic assumptions about human behaviors. In this model,

individuals are assumed to seek to maximize their own economic interests.

Accordingly, HCT postulates that individuals invest in education and training in

the hope of getting a higher income in the future. These investments, as Blaug

412

This content downloaded from

54.189.126.232 on Sat, 30 Mar 2024 01:07:19 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Human Capital Theory

(1992) put it, are not only "for the sake of present enjoyments but for the sake of

pecuniary and non-pecuniary returns in the future" (p. 207). This approach is

closely associated with methodological individualism. It is the doctrine that the

roots of all social phenomena could be found in the individual's behaviors. This

conforms to the assumption that human capital formation is typically undertaken

primarily by those individuals who seek to maximize their interests (Blaug, 1992).

Having said that, the human capital economists do not necessarily disregard the

nonmonetary contributions of education to the individual and society. They also

acknowledge the social, cultural, intellectual, and aesthetic benefits of education

but these are called positive externalities.

As Marginson (1989, 1993) described, the line of assumptions in HCT goes as

follows: the individual acquires knowledge and skills through education and

training, that is, human capital. These knowledge and skills will increase his or

her productivity in the workplace. This increased productivity will bring a higher

salary to the individual since the wage of a person, in the ideal labor market, is

determined by the person's productivity. Therefore, people would invest in educa

tion up to the point where the private benefits from education are equal to the

private costs. In light of this set of assumptions, the logic of HCT becomes clear

that education and training increase human capital and this leads to a higher pro

ductivity rate, which in turn brings a higher wage for the individual. Based on this

train of reasoning, it can be claimed that education and earnings are positively

correlated and thus education/training should be promoted. In the subsequent sec

tions, the origin and accuracy of this line of reasoning will be investigated.

Methodological Criticisms

The neoclassical economic model focuses on two core paradigms by which it

attempts to explain social/economic phenomena: methodological individualism

and rational choice theory. These paradigms are going to be reviewed respectively

in this section.

Methodological Individualism

Methodological individualism (MI) is a doctrine that takes the individual as a

point of departure. It places the individual at the center and emphasizes the human

agent over social structures (Hodgson, 2004). This approach maintains that to

comprehend social phenomena, we need to comprehend individuals and their

motives. In Bentham's (1789) words,

The community is a fictitious body, composed of the individual persons. . . . The

interest of the community [is] the sum of the interests of the several members who

compose it. It is in vain to talk of the interest of the community, without understanding

what the interest of the individual is. (p. 2)

Similarly, the German economist Carl Menger (1985) suggests that to under

stand a national economy, it is essential to understand "the singular economies in

the nation" (p. 93). To this view, a collective action is a product of individual

desires that aim to promote individual interests. After all, the members of

413

This content downloaded from

54.189.126.232 on Sat, 30 Mar 2024 01:07:19 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Tan

associations or unions believe that their individual interests are more effectively

protected and promoted if they act together (Scott, 2000). The establishments

such as trade unions are just instruments or mechanisms that enable individuals to

reach their goals effectively (Buchanan & Tullock, 1962).

To avoid any possible confusion, it is important to remind that political indi

vidualism (PI) has almost nothing to do with MI. Schumpeter (1980) underlines

that the former (PI) starts from the general assumption that freedom, more than

anything else, contributes to the development of individuals and the well-being of

society, whereas the latter suggests that the individual is the basic unit of a social/

economic analysis. Therefore, to the methodological individualists, a scientific

inquiry in social studies should start from individuals, their beliefs, and desires to

account for social phenomena. Hence, it is perfectly possible that a person can be

collectivist in politics and methodological individualist in his or her scientific

approach because MI is not incompatible with the statement that individuals often

desire and promote the welfare of other individuals (Elster, 1982).

MI attempts to make sense of the whole through the knowledge of the most

basic unit in the whole. This reductionist view is in sharp contrast with method

ological collectivism/holism, which suggests that to make sense of a phenomenon

we need to understand the context in which it takes place. To this school of

thought, a profound understanding of the society and its dynamics are the key to

explain social phenomena. A social phenomenon is not a product of individual

behaviors; on the contrary, individual behaviors are the products of social, cul

tural, and environmental factors. That is, there is a set of ideas and values that are

above our individual consciousness (Szelényi, 2011). They affect and shape our

consciousness and create a new set of ideas and values that are different from our

own. Methodological collectivists conclude that social phenomena cannot be

reducible to the individual alone as the whole is different from the sum of the

individual constituents.

In response to it, the methodological individualists (Arrow, 1994) argue that

social interactions are, after all, the products of countless interactions among indi

viduals. It is true that individuals do not act on their own, they reciprocate each

other but each individual acts in a certain range limited by their individual con

straints such as their ability, wealth, and time. Furthermore, the social and institu

tional rules themselves change as a result of individuals' actions. Social institutions

like the family, state, and law emerged from dynamic relationships between the

members of the society. In the process of the emergence of these social institu

tions, each step was often intentional and rational, but the ultimate outcomes were

typically the unintended consequences of a series of rational actions. To clarify

this point, Menger (1985) refers to the origin of money and how it came into exis

tence over a long period of time by replacing barter. This replacement was not

intended at the beginning but gradually took place. In each step, people tried to

find a better way to replace barter and finally, it was recognized that money was

the most convenient medium of exchange. Hence, the institution of money is an

outcome of a sequence of rational individual actions (Udehn, 2002). That is to say,

money came about as the unintended result of individual human efforts without a

common will directed toward its establishment (Menger, 1985). Likewise, in

social studies, whoever wants to investigate a phenomenon theoretically needs to

414

This content downloaded from

54.189.126.232 on Sat, 30 Mar 2024 01:07:19 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Human Capital Theory

go back its true elements, the individuals (Menger, 1985). That is, before we

attempt to examine the functions of an institution such as the money, family, or

state, we need to analyze what were the primary motives of individuals when they

formed these establishments.

What are the implications of MI in the neoclassical economic model? First, in

order to understand an action or a social/economic phenomenon, it is necessary to

assume the existence of individual preference orderings and individual choices as

the basic theoretical building blocks of a scientific inquiry. Second, social out

comes are the by-products of choices made by individuals who rationally pursue to

maximize their own interests. Hence, rational choice explanations are formulated

along these lines by reference to individuals' intentions and motivations (Green &

Shapiro, 1994). The importance of MI may not be adequately appreciated at first

glance but MI is the very foundation that rational choice theory built on.

Rational Choice Theory

The second paradigm which HCT rests on is rational choice theory (RCT). In

this section, the origin, principles, and limitations of RCT will be discussed. It

will be argued that RCT itself is not immune from imperfections; therefore, HCT,

which is rooted from RCT, is bound to be imperfect as well.

The Origin of the Theory

Rational choice theory provides a model to understand and predict human

behaviors.1 Simply, it seeks an answer to the question of what is the most efficient

way to reach a goal in a given condition. It is a normative theory and tells us what

we ought to do in order to reach our goals. It does not tell us, however, what our

goals ought to be. It implies that RCT is interested in the means rather than the

ends. That is, unlike moral theory, RCT proposes conditional imperatives, what an

agent ought to do in order to achieve his or her aims in a given set of constrains

(Elster, 1986).

Rational choice theory suggests that individuals seek to maximize their own

interests by making optimal decisions in the entire domains of their lives. The

word entire should be highlighted because the adamant proponent of this approach

Gary Becker (1976) states,

Subsequently, I applied the economic approach to fertility, education, the uses of

time, crime, marriage, social interactions, and other sociological, legal, and political

problems. Only after long reflection.... I conclude that the economic approach was

applicable to all human behavior, (p. 8)

In fact, this economic approach or economization of human behaviors goes

back as early as the 18th century. It was largely developed by the utilitarian econo

mists who advocated the measurability and interpersonal comparability of utility.

The utilitarians believed that the maximization of utility is an ethically desirable

social goal (Buchanan, 1959). Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832), the founder of utili

tarianism, reduced the ultimate motives of all human actions into two: pleasure and

pain. To Bentham (1789), pleasure and pain are two sovereign masters of our

415

This content downloaded from

54.189.126.232 on Sat, 30 Mar 2024 01:07:19 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Tan

conducts that govern us in all we do, in all we say, and in all we think. Bentham

frequently cited the concept of efficacy and he devised the hedonistic calculus

system to measure the likely pleasure/pain of a specific act. This was a type of cost/

benefit analysis of an act to determine whether the act in question would be desir

able or not. In this system, a hedon = a standard unit of pleasure and a dolor = a

standard unit of pain. However vague it may seem, based on this quantification, if

the pleasure exceeds the pain, it is possible to say that the act is ethical (Hinman,

2008). It is also worth noting that Bentham (1789) was so passionate about the

power of numbers and mathematics that he thought mathematics could guide

humanity even in moral and political affairs let alone in positive sciences.2

This scientificization or mathematization later on became the dominant feature

of the neoclassical economic school. In this way, the rhetoric of successful science

was linked to the neoclassical theory. Whether this linkage was planned before

hand or not, for once the neoclassical economics was associated with scientific

economics, to challenge the neoclassical model was to seem to challenge science,

progress, and modernity (Weintraub, 1993). However, for some, the idea of math

ematization was seriously flawed. For instance, Paul Krugman (2009), a Nobel

laureate, regretfully noted that "the economics profession went astray because

economists, as a group, mistook beauty, clad in impressive-looking mathematics,

for truth" (para. 4).

The Basic Principles of RCT

The most elementary principle of RCT is that individuals do their best to maxi

mize their utility under prevailing circumstances. As Green (2002) put it, "The

choices made by persons are the choices that best help them achieve their objec

tives, given all relevant [constraints]" (p. 5). Despite some disagreements among

the RCT scholars, the widely recognized axioms of RCT are transitivity, invari

ance, and continuity.3

Transitivity: If A is preferred to B, and Β to C, then A must be preferred to C. The

choices should be internally consistent and capable of being ordered.

Invariance: The different representations of the same problem should generate the

same result even when shown separately.

Continuity : If A is preferred to B, then the option suitably close to A needs to be

preferred to Β as well. (Ayton, 2012, p. 339; Sue, 2004, p. 6)

Human behaviors are considered rational if they are in coherence with these

axioms, which were supposed to be the assumptions that no rational person could

violate (Anand, 1993, cited in Sue, 2004). Although it is still controversial even

within the supporters of this theory, RCT is known to be a universalist theory and

its proponents believe that the model applies equally to all persons (for a detailed

discussion, see Green & Shapiro, 1994). To the RCT scholars, "Rules and tastes are

stable over time and similar among people" (Becker & Stigler, 1977, p. 76). This

homogeneity assumption provides both theoretical parsimony and tractability

416

This content downloaded from

54.189.126.232 on Sat, 30 Mar 2024 01:07:19 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Human Capital Theory

while eliminating a frustrating number of interpersonal variations that otherwise

would need to be taken into consideration (Green & Shapiro, 1994).

Stigler (1987) clarifies it further and says that there are three characteristics of

rational consumers (a) their tastes are consistent, (b) their cost calculations are

correct, and (c) they maximize their utility. A rational individual behaves in accor

dance with these assumptions while he or she makes decision. This rational agent

is called homo economicus, who is purposeful, labor-averse, self-interested, and

a utility-maximizer. Homo economicus is the representative figure by which the

mainstream economists try to explain human behaviors. The rationale behind this

representative figure is twofold: first to form a framework which enables to sim

plify the complexity of the real world in which the amount of information is

ample; second, to create an artificial world in order to compensate the absence of

laboratory experiments to apply the theory to the real world. In this way, it

becomes easy to find a representative agent through which human behaviors in

the market can be evaluated and predicted. However, does such a person, who is

obsessed with a specific rule (utility maximization) really exist in a supposedly

determinist environment (Bentata, 2009)?

Is it possible to say that average individuals in the street know the meanings of

optimal decision, price equilibrium, marginal utility curve, and so on? If the

answer can hardly be yes, how can the fully rational homo economicus be an ideal

representative of laypersons while they have almost no clue about economics and

its basic terms? Does this make them less homo economicus?

Milton Friedman (1953) provides an example to clarify it. Let us think of an

expert billiard player. Although the player is not familiar with mathematical or

physical formulas, the player hits the ball in a way that

as if he knew the complicated mathematical formulas that would give the optimum

directions of travel . . . could make lightning calculations from the formulas, and

could then make the balls travel in the direction indicated by the formulas. Our

confidence in this hypothesis is not based on the belief that billiard players, even

expert ones, can or do go through the process described; it derives rather from the

belief that, unless in some way or other they were capable of reaching essentially the

same result, they would not in fact be expert billiard players, (p. 12)

The expert players have no knowledge about physics, but when they play they act

as if they compute the Newtonian physics of ball movement on the table surface

(Glimcher, 2011). But if the expert players are asked that how is it possible to hit

the ball with that perfect speed and precision, the reply is simply that I just figure

it out (Friedman, 1953). Thus, having no information about physics does not

impede the players from executing physical laws. Similarly, individuals act in the

market as if they know the relevant demand functions, price equilibrium, marginal

utility curve, and so on. As such, under a wide range of circumstances individuals

rationally seek to maximize their profits although they may fail to express it ver

bally in the language of economics (Glimcher, 2011).

Friedman's example may seemingly lead to the conclusion that homo eco

nomicus is a fair representation of laypersons. For the sake of argument, let us

417

This content downloaded from

54.189.126.232 on Sat, 30 Mar 2024 01:07:19 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Tan

accept that the regular individuals know how to maximize their own interests in

the way described by Friedman. Their decisions are meticulously calculated and

finely consistent with their past and future decisions. But do these rational indi

viduals have any weakness at all?

The Limitations of RCT

Jolis, Sunstein, and Thaler (1998) point out three limitations in RCT, thus with

homo economicus. These are bounded rationality, bounded willpower, and

bounded self-interest. Each will be explained in turn.

Bounded rationality, coined by Herbert Simon (1956), indicates the obvious fact

that human cognitive abilities are not infinite. Human beings have limited computa

tional skills and weak memories. To overcome this, when we face a problem with a

huge quantity of information, we tend to satisfice on options rather than optimizing

them. The word satisfice is a portmanteau: satisfy and suffice. Accordingly, if you

are a satisficer, you are happy with something that is good enough and once you find

it, you stop searching rather than pursuing the best (optimal) alternative (Manktelow,

2000). In addition to that, we make list and use mental shortcuts and rules of thumbs

to avoid dealing with an ample quantity of information again and again. These

shortcuts themselves may turn into obstacles and produce various human behaviors

that systematically differ from those predicted by RCT.

Numerous empirical works in behavioral economics show that the actual

behaviors of people may not be coherent with the RCT axioms. Kahneman (2003)

illustrated that our decisions can be constrained by many factors such as intuition,

perception, and optical illusions. Moreover, marketing and presentation tech

niques may distract our attention and we may focus on one part while ignoring

another. Even the different wording of the same statements may lead to different

conclusions. For instance, people may give an affirmative answer to a question.

However, if the same question is asked in the negative form, their answers may

completely differ from their initial responses. This is called the framing effect:

different reactions to the same problem depending on the way the problem is

framed and presented. Kahneman and Tversky (1981) provided a solid example

for this phenomenon. In their study, a group of respondents were asked to evaluate

a disease which could kill 600 people in a town and they had to choose one of the

two options in two separate evaluations as shown in Table 1.

In the first evaluation the majority of respondents preferred A to B. However,

in the second evaluation, the majority of the same respondents favored B' over A'.

What is striking is that there is hardly any difference between Program A and

Program A', and Program Β and Program B'. After all, 200 people will be saved

means 400 people will die. Similarly, a one-third probability that 600 people will

be saved means a two-third probability that everybody will die. But participants

changed their responses diametrically in the different presentations of the same

problem. The reason is the certainty of saving people seemed more attractive,

whereas accepting the certain death of people was considered disproportionately

aversive. It can be attributed to the fact that the different presentations of the same

problem may highlight one point and mask another (Kahneman, 2003). This

clearly violates the invariance axiom, the different representations of the same

problem should lead to the same conclusion, and the transitivity axiom,

418

This content downloaded from

54.189.126.232 on Sat, 30 Mar 2024 01:07:19 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

TABLE 1

The Framing Effect

First

First evaluation

evaluation Second evaluation

If Program

If Program A

A is

is adopted,

adopted, 200

200people

peoplewill

willIf

IfP

be saved. die.

If Program Β

B is adopted,

one-third probability tha

will be saved and a two-th

ity that no people will be saved. people will die.

Source. Adapted from Kahneman and Tversky (1981, p. 453).

preferences should be internally consistent. That is, human decisions can be too

sensitive to manipulations including to the irrelevant ones, unlike homo eco

nomicus who always behaves and decides consistently.

It should be noted that the behavioral economics literature provides an abun

dant number of empirical cases in which respondents behave rather inconsistently.

These cases pose a serious challenge to RCT (for notable examples, see Hsee,

Lowenstein, Blount, & Bazerman, 1999; Kahneman, 2012; Tversky, Slovic, &

Kahneman, 1990).

The second concept that Jolis et al. (1998) introduce is bounded willpower. It

refers to the fact that individuals may display a set of behaviors that are inconsistent

with their long-term interests, even though they are acutely aware of the adverse

impacts of these behaviors. Simple examples would be that most smokers say that

they would prefer not to smoke. Drug users as well as alcoholics fail to resist the

temptations of these addictive materials. More interestingly, senior figures like pres

idents and top intelligence officials may succumb to their momentary desires and

destroy their own careers to which they have dedicated almost their entire life.

Furthermore, people may not work hard although they are required to do so, they

may not show sufficient patience, and they tend to gratify their immediate desires

while renouncing their long-term interests. In these circumstances, individuals sig

nificantly deviate from the standard economic model and act in discord with RCT.

The third concept that Jolis et al. (1998) propose is bounded self-interest. It

suggests that most people care or act as if they care about others. In many market

settings, people care about being treated fairly and want to treat others fairly.

Individuals can be both nicer and more spiteful (if they are not treated fairly) than

the agent postulated by RCT. Of course, bounded self-interest does never imply

that people are not motivated by their own self-interests, but rather it reminds that

the goal of individuals is not solely to promote their own interests. As humans, we

are pluralistic, navigating between our own interests and the interests of others

(Brown, Brown, & Preston, 2011).

Reconsidering Friedman's Billiard Player Example

In light of these criticisms, it is worth reexamining the example given by

Friedman. Kahneman and Tversky (2000) ask that the mathematical model of RCT

419

This content downloaded from

54.189.126.232 on Sat, 30 Mar 2024 01:07:19 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Tan

can be a good predictor to estimate the behaviors of an expert player, but is this

model also sufficient to predict the behavior of nonexperts, such as a novice or

intermediate player? Obviously, there will be a noticeable disparity between the

billiard performances of the expert player and nonexpert ones. However, RCT

takes the expert player as a normative figure and he or she consistently makes the

best shot out of all the shots available. But, the novice and intermediate players do

not have the same degree of competency in the play. Thus, they perform poorly,

make inconsistent shots and as a result violate the normative model. Clearly, homo

economicus is not an accurate representation for the novice and intermediate play

ers. Kahneman and Tversky (2000) conclude that the orthodox model of consumer

behavior is based on a model of robot-like experts. For this reason, it makes poor

predictions of the behaviors of the average consumers. It is not because the average

consumers are irrational or dumb. But rather they are not robot-like beings who

consistently make the best shots in a given set of condition. Moreover, even they

do not always seek the best and are content with the reasonably good ones.

The Relevance

After delving into RCT, the reader may not see any straightforward connection

between the limitations of RCT and HCT. The simple connection is that the neo

classical approach places homo economicus at the center and it attempts to make

sense of social and economic phenomena through the lenses of this rational per

son. However, a considerable number of experimental studies demonstrate that

this hypothetical rational and utility-maximizing person does not fully correspond

to real human beings in actual life. Thus, homo economicus is not a good model

to explain a variety of social and economic phenomena. But HCT is built on this

weak model. Therefore, HCT will have the same defects and limitations when it

attempts to explain educational phenomena because its basic assumptions on

human motives, goals, and decisions are not well-grounded. For instance, HCT

assumes that individuals are rational and they will invest in education so long as

the marginal benefits exceed or equal the marginal costs. That is to say, like an

entrepreneur, individuals will estimate the future benefits of education and the

costs of it. If the rate of return to education is positive, the benefits outweigh the

costs, then individuals will make that investment. If it is not positive, they will not

continue their education (Johnes, 1993). This presumption is in full conformity

with the homo economicus model. However, it has been illustrated that human

decisions and preferences are affected and limited by many other factors such as

individuals' cognitive abilities, perceptions, and habits. Consequently, individu

als' decisions about their education careers are also affected and limited by social,

cultural, and other factors whereas homo economicus in the neoclassical approach

seems to be immune from these limitations.

It is also well documented by empirical studies that individuals undertake an

educational program for a variety of reasons including peer pressure, parents'

expectations, even the desire to leave home (Jenkins, Jones, & Ward, 2001), and

the social class of parents can also be a decisive factor (Bowles & Gintis, 2002).

That means every individual is influenced by a unique set of factors and motiva

tions when they plan their education careers (Marks, Turner, & Osborne, 2003).

It is particularly the case in post-compulsory education since it has the

420

This content downloaded from

54.189.126.232 on Sat, 30 Mar 2024 01:07:19 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Human Capital Theory

characteristics of positional goods, which provide relative advantage in the

competition for the job, social status, and so on (Hirsch, 1976). For instance,

Purcell and Pitcher (1996) highlighted three broad categories for the reasons to

go to university: hedonistic (enjoyment), pragmatic (employment), and fatalis

tic (passive reasons such as parental pressure). This indicates that unlike HCT

proposes, decisions about giving up or carrying on education is not a completely

rational process based on a painstakingly calculated cost-benefit analysis.

Therefore, the main paradigm of the neoclassical model is seriously flawed.

That is why HCT, established on these flawed premises, is bound to fail to

explain a significant number of cases taking place in real life.

Why Is RCT So Popular?

It calls into question that if RCT suffers from serious limitations, why it is still

so popular and why the mainstream economists do not abandon this theory. First of

all, rational choice theorists are also well aware of these limitations. Even Becker

himself describes his attitude as "an irrational passion for dispassionate rational

ity" (cited in Herfeld 2012, p. 77). Nevertheless, the proponents of this theory

argue that a theory should be evaluated on the basis of its ability to predict human

behaviors rather than its descriptive accuracy (Friedman, 1953). In plain English,

this means that RCT may not always work but it will usually work in many

instances since its predictive power to explain human behaviors is sufficiently

strong. For this reason, despite a substantial number of the contrary examples, RCT

is considered to be the best approximation of human behavior, based on the reason

ably simple assumptions that generate fairly accurate predictions (Arley, 1998,

cited in Luth, 2010). More important, RCT provided a model which is easy to chal

lenge but difficult to replace. Amartya Sen (1990) highlighted this point:

Even though the inadequacies of the [RCT]... have become hard to deny. It will not

be an easy task to find replacements for the standard assumptions of rational

behavior . .. both because the identified deficiencies have been seen as calling for

rather divergent remedies, and also because there is little hope of finding an

alternative assumption structure that will be as simple and usable as the traditional

assumptions of self-interest maximization, or of consistency of choice, (p. 206)

The next section will focus on the areas that HCT does not make good

predictions.

Empirical Criticisms

In the previous section, the theoretical premises of HCT have been examined.

In this part, the empirical consistency of HCT will be questioned in light of the

competing theories and empirical studies. The article will start with a rival thesis:

signaling theory.

Signaling

Human capital theorists claim that education enhances a person's skills and it

leads to a higher productivity level in the workplace, which in turn will bring a

higher wage to the person. The signaling theory, coined by Spence in 1973,

421

This content downloaded from

54.189.126.232 on Sat, 30 Mar 2024 01:07:19 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Tan

provided another explanation for this higher wage. The theory suggests that the

education levels of individuals indicate their certain innate characters such as

their propensity to be intelligent, their dedication, time management skills, and

ability to follow instructions. Signaling theorists argue that what the school does

is to classify students according to their intelligence and commitment through the

processes of admission requirements and grading (Soldatos, 1999). By doing that,

it establishes a supposed hierarchy of students based on their academic successes,

by which the potential productivity level of an individual, more or less, can be

predicted. In practice, it enables employers to sort out and reassess job applicants

once more before their recruitments. In this assessment and selection process, the

applicants signal their desirable, but unobservable skills via their academic cre

dentials whereas the firms screen and identify them by the help of the same aca

demic credentials (Brown & Sessions, 2005). Therefore, the firms require a

minimum level of schooling from the applicants to screen them out (Weiss, 1995).

In this connection, signaling theorists emphasize two points. The first is that

schooling may reflect higher productivity without causing it, because education is

not the source but the signal of higher productivity of educated people since

schools identify the able and committed individuals and eliminates the less able

ones in the process. The second is that due to imperfect information in the labor

market, the education level of a person is simply taken as a proof of his or her

higher ability to produce whereas in fact there is not necessarily a correlation

between education and productivity (Mankiw, Gans, King, & Stonecash, 2012). It

follows the conclusion that education may increase a person's wage without

increasing his or her productivity per se (Blaug, 1976).

Psacharopoulos (1979) aptly distinguished two forms of signaling: strong sig

naling hypothesis (SSH) and weak signaling hypothesis (WSH). The difference

between the two is that SSH suggests that education has little or no impact on

productivity, but it just reveals individuals' innate ability to work, whereas WSH

suggests that education has two functions: to foster productivity and to signal indi

viduals' innate abilities. SSH has been empirically refuted to a great extent whereas

WSH has some empirical supports (see Clark, 2000; Jaeger & Page, 1996).

Regarding the signaling effect, three points need to be highlighted. In these

particular cases, the impact of sorting mechanisms can be more salient and thus

the signaling hypothesis can obtain some empirical support from them, whereas

HCT fails to explain these instances plausibly.

First of all, since signaling theory stems from the theory of decision making

under uncertainty, the primary example of the signaling effect can be found in

initial hiring, for the obvious reason that the firm does not have sufficient infor

mation about the productivity of the applicant apart from his or her educational

qualifications. There are a substantial number of studies that confirm that initial

wages can be higher for educated persons because of imperfect information on the

expected productivity level of the applicants (Soldatos, 1999). However, once this

initial period is over, the wage is primarily determined by productivity rather than

by academic qualifications. Namely, the employer no longer pays to the individ

ual on the basis of his or her academic credentials once his or her work perfor

mance has become clear. As a result, the worker's wage may not follow the

expected return pattern predicted by HCT when his or her tenure increases. This

422

This content downloaded from

54.189.126.232 on Sat, 30 Mar 2024 01:07:19 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Human Capital Theory

is called the tenure effect, which also substantiates signaling hypothesis (Liu &

Wong, 1982). Fang (2001) reminded of these formal and informal signaling pro

cedures in initial hiring:

If workers' productivities are in fact not perfectly observed (which is particularly

tme for newly hired workers), then the firms would have to infer the productivities

from noisy signals such as interviews, tryouts, and reference letters together with

their education levels, (p. 3)

Second, to test the signaling hypothesis empirically, the difference between

self-employed and salaried employees is thought to be a good measure to contrast.

Since the self-employed are assumed to be the unscreened group, they do not have

to signal their innate abilities to the employer, although some self-employed may

want to attract customers with their academic qualifications (Castagnetti, Chelli,

& Rosti, 2005). Moreover, there is a more visible relationship between productiv

ity of a person and his or her wage when he or she is self-employed. If signaling

hypothesis is true, there should be a noticeable difference between paid employ

ees and self-employed. That is to say, self-employed persons should have lower

monetary returns to education.

The overwhelming majority of the empirical studies reject the strong version

of signaling in terms of self-employment and they found positive returns to educa

tion for self-employed workers with middle- or high-level education (see Brown

& Sessions, 1999; Garcia-Mainar & Montuenga-Gomez, 2005; van der Sluis &

van Praag, 2004). However, even the strong version of signaling enjoyed some

empirical supports. For instance, Castagnetti et al. (2005) found that there is a

significant positive return to education for salaried employees whereas an insig

nificant return to education for self-employed in Italy. This result is in congruence

with the strong signaling hypothesis which states that education does not increase

productivity. Similarly, Heywood and Wei (2004) found a significant signaling

effect in Hong Kong where competition is rather tense in the labor market.

Heywood and Wei discovered considerably smaller returns to education for self

employed persons comparing with those of salaried employees, which strength

ens the validity of signaling theory.

Third, the degree of signaling may substantially vary from one country to

another. For example, supporting empirical evidence for the screening effect has

been found in Israel, Japan, Australia, Hong Kong, and Singapore but not in

Greece, Malaysia, Netherlands, Sweden, and Egypt. Mixed results have been

found in the United Kingdom and the United States (Brown & Sessions, 1999).

This can be attributed to the distinct nature of each country's education system

and labor market. Institutional factors, trade unions, and general perceptions

about the quality and the quantity of educated workforce can also be pivotal in

determining the magnitude of the signaling effect.

Signaling theory appears to propose more plausible explanations than HCT

does regarding a number of particular instances. These cases provide an empirical

support for signaling theory. It is also well documented that meritocracy is not

always the case in the labor market (see Cawley et al., 2001). Titles, degrees, and

university reputation can sometimes be more valued than their actual values in the

423

This content downloaded from

54.189.126.232 on Sat, 30 Mar 2024 01:07:19 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Tan

labor market. Having said that, despite all the counterarguments to HCT, the

recent literature tend to see the signaling theory as an extension of HCT rather

than competitive to it (Weiss, 1995). As Machlup (1984) noted that the discussion

on screening is not whether education has a sorting function—as it must have—

but rather whether it serves merely and solely as a screening device (cited in Cohn,

Kiker, & De Oliveira, 1987).

Some may not find this debate interesting and ask that as long as an educated

person finds a good job, does it really matter whether education enhances produc

tivity or it just sorts out job applicants? According to the human capital theorist

Gary Becker (1993a) no, it does not because "even if schooling also works in this

way [as a sorting device], the significance of private rates of return to education is

not affected at all" (p. 8). Here is the focal point of the discussion. HCT postulates

that education increases a person's productivity in the workplace and it, in turn,

leads to a higher wage for the person. It means that all sides, the individual, firm,

and country, will benefit from this higher productivity stemming from education.

However, signaling theory suggests that education may bring a higher income to

the individual without bringing any higher productivity to the firm and the coun

try. Hence, there is no direct correlation between education and the productivity

level of a country. That is, more investment in education does not mean more

economic growth for the country or mass education does not lead to mass produc

tion. This conclusion runs against HCT, which assumes that more education will

bring more economic growth to the country. However, this is not always the case.

The reason is that education may have a high private rate of return but low, even

negative, social returns (will be discussed in next section). In this connection,

Spence (1973) argues that "private and social returns to education diverge.

Sometimes everyone loses as a result of the existence of signaling. In other situa

tions some gain, while others lose" (p. 368). This simply means that the overin

vestment in education by the government is economically inefficient and this kind

of investment is a typical example of Pareto inefficiency, scarce resources are not

exploited in the best way and no one can be made better off without making at

least one individual worse off. Put it another way, it means that society is squan

dering its resources in the production of education. The signaling theorist Spence

points out that this is a possibility (Bonanno, 2012) and there is some empirical

data in congruence with it.

Education and Growth

Another tenet of HCT is related to the impact of education on national eco

nomic growth. To the theory, education will not only increase the wages of edu

cated employees but also it will generate higher productivity, lower unemployment,

and greater social mobility, what are called positive externalities: the impact of

education on aggregate output is greater than the aggregation of the individual

impacts. In other words, the average incomes of educated persons will rise, how

ever, if there are positive externalities to education, national average incomes

should rise even more than the sum of individual incomes (Pritchett, 2001).

However, contrary to this assumption, it is well documented that education can

increase private returns but not social returns. Therefore, the impacts of education

may differ at the individual level and the national level, what is called the

424

This content downloaded from

54.189.126.232 on Sat, 30 Mar 2024 01:07:19 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

6.5

6.5

2>

2>5.5 5.5

•R

•S 4.5

4.5

>.

ο

a

S1

S1 3.5

3.5

>

Average years of total

< schooling, age 15+, total

2.5 GDP per capita (Constant

price 1996 PPP)

1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000

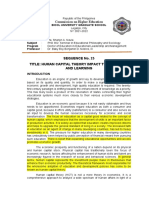

FIGURE 1. Schooling and GDP per person in Venezuela

Source. Ortega, D., & Pritchett, L. (2014). Much higher

wages: Human capital and economic collapse in Venezue

Chavez: Anatomy of an Economic Collapse, edited by Ri

Francisco Rodriguez, p. 189, Copyright © 2014 by The Pe

Press. Reprinted by permission of The Pennsylvania Stat

micro-macro paradox (Pritchett, 2001). There is no sho

paradox. In that regard, Caselli, Esquivel, and Lefort

and Weil (1992) do not find a strong evidence for th

human capital necessarily produces economic growth.

Benhabib and Spiegel (1994) discovered that "human c

to enter significantly in the determination of econom

with a negative point estimate" (p. 166). Nazrul Islam

correlation between schooling and growth in some co

though schooling rates substantially increased in sever

El Salvador, Bolivia, Jamaica, Peru, and Jordan from

improvement or even negative growth took place in t

els of these countries (Pritchett, 2009).

As a striking example, Venezuela presents a shar

higher schooling and much lower wages between

Pritchett, 2014). Unlike HCT predicts, an unprecedent

not generate a rapid increase in production at the m

proportionately high return at the individual level. On

relation was observed between schooling and the n

Venezuela. Figure 1 illustrates this contradiction.

425

This content downloaded from

54.189.126.232 on Sat, 30 Mar 2024 01:07:19 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Tan

As shown, despite a rising schooling rate, the GDP per capita has decreased

between 1960 and 2000. In fact, there should have been more than a 50% increase

in wages instead almost a 40% decrease has taken place in this period. Now, it

prompts the question that what can be the source of this contradiction? Pritchett

(2001) proposed possible explanations for it. First, the education system in

Venezuela appears to have failed. Massive enrolments in schools have been detri

mental to the quality of education and resulted in unequal distribution of educa

tional services (Dessus, 1999). Furthermore, this massive enrollment created a

gap between the supply and demand in the Venezuelan labor market. Since human

capital supply grew faster than human capital demand, the labor market failed to

absorb the sharply increased number of educated individuals (Gonzalez &

Oyelere, 2011; Patrinos & Sakellariou, 2006). The second possible explanation is

that political and social establishments did not provide the educated Venezuelans

with the environment in which they can make use of their skills in the best way.

In that regard, one of the much debated issues in Venezuela has been rent seeking

jobs; making money without creating wealth such as political lobbying, govern

ment bureaucracy, lawyering, policing, and army (Ffammond, 2011; Karl, 1997;

Rodriguez, Morales, & Monaldi,). These rent-seeking activities can be individu

ally remunerative although socially unproductive (Di John, 2009; Tullock, 1967).

As Torvik (2002) noted that the use of human capital is adversely affected by

rent-seeking activities. The reason is that if the payoff is high in unproductive but

lucrative jobs, human capital skills are diverted away from entrepreneurial jobs

and put into rent-seeking ones since individuals are not necessarily driven by

productivity but rather by profit (Acemoglu, 1995). Consequently, the micro

macro paradox occurs due to the fact that potential entrepreneurs with significant

human capital endowments become rent-seekers rather than wealth creators

(Mehlum, Moene, & Torvik, 2006). Thus, the social and private rates of return to

education diverge as a result of distortions in the economy. Surely a slow or nega

tive growth, despite a considerable schooling in a country, is not sufficient to

dismiss the claim that human capital accumulation has a positive impact on eco

nomic growth. But this rather suggests that social, political, institutional, and cul

tural factors need to be considered when the impacts of education is predicted

(Pritchett, 2001). For that reason, in some countries, the linear relationship

between education and economic growth does not seem to exist unlike HCT

postulates.

There is also a sizable disparity regarding the impacts of education between

poor and rich countries. It leads to the question that why education has not paid

off at aggregate level in these poor countries? Jones ( 1996) argued that the increase

in schooling was in relative rather than in absolute terms. Several poor countries

with very low levels of education have increased their average educational attain

ments by a high percentage: for example, from 1 year to 2 years, a 100% increase.

On the other hand, developed countries have increased their average levels by 1

or 2 years as well, but starting from a higher initial base. This relative increase in

developing countries may highlight a part of the contradiction between a high

increase in schooling and little growth in national economy. It is clear that each

country has its own unique historical background, not only in politics but also in

education. Thus, when the impacts of education and the future economic growth

426

This content downloaded from

54.189.126.232 on Sat, 30 Mar 2024 01:07:19 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Human Capital Theory

rate of a country is predicted, historical factors need to be considered as well

because the institutions like the education system or labor market in a country

cannot be isolated from their past. Therefore, the same year of schooling in differ

ent countries may lead to different economic outcomes due to the historical

factors.

Finally, a question needs to be asked. If there are a significant number of coun

ter examples, why international organizations such as World Bank or OECD pas

sionately support the concept of human capital? First of all, they also acknowledge

that just education is not enough for economic growth. Rampant corruption, rent

seeking, nepotism, and so on are also major obstacles to economic development.

Therefore, countries with corrupt government officials, ponderous bureaucracy,

poor law enforcement, and unequal opportunities poorly perform in terms of

human capital formation and outcomes (see the OECD report by Mejia & Pierre,

2008; Pissarides, 2000). That is, what is called social infrastructure, the institu

tions and government policies that determine the economic environment, plays a

key role in the effective use of potential human capital (Hall & Jones, 1999). As a

result, state establishments and bureaucratic regulations should create the habitat

in which human capital accumulation is encouraged and rewarded. Second, some

OECD researchers suggest that "data quality and econometrics do matter in

explaining the often disappointing results on the link between human capital and

growth" (Bassanini & Scarpetta, 2001, p. 24). They contend that if improved data

set and different econometric methodologies are used, there will be more coherent

results between schooling outcomes and the predictions of HCT. Since the data

collection and its analyses are quite sophisticated, different measurement tech

niques may yield a different set of outcomes in favor of HCT. Third, for instance,

the World Bank report for Africa (2010) blamed teachers and civil servants in

Africa and accused some of the teachers of quiet corruption: various types of

malpractices of frontline providers (teachers and inspectors) that do not involve

monetary exchange. For example, there is a high level of absenteeism and low

performance on the job among teachers in some African countries. This leads to

lower human capital and lower productivity in the labor market, resulting in the

noninvestment in the human capital of children because of beliefs about the low

quality of education. Thus, institutional factors and individuals' commitments to

their own professions need to be taken into account since these elements affect the

overall quality of human capital and may lead to a high or low economic growth.

To conclude, there are empirical results both at individual and aggregate levels

that are incoherent with the predictions of HCT. Now we turn to another dimen

sion of HCT: its impact on education and politics.

Practical Criticisms

In this section, the impacts of HCT on other academic disciplines will be dis

cussed and the consequences of the neoclassical approach in practice, particularly

in the fields of education and politics will be examined.

The first criticism against HCT is related to the scope of the discipline of

economics. Namely, what are the boundaries of economics and what should its

boundaries be? It is true that there are some multidisciplinary aspects in any

subject. For instance, historians may need a chemist to pin down the date of a

427

This content downloaded from

54.189.126.232 on Sat, 30 Mar 2024 01:07:19 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Tan

skull. In that sense, the exchange of information and experiences at a cross-dis

ciplinary level are not only possible but also desirable. In this case, however, the

complexion of the story is different because it is not a symbiotic relationship

based on mutual benefits in which both disciplines have something to offer. But

rather it is becoming a top-down relationship, and economics is gradually domi

nating other disciplines hoping to compose a hierarchy based on the superiority

of economics.

In this relationship, economics has gained new fronts with the help of the neo

classical school in general and HCT in particular. The intrusion of economics into

the realms of sociology, education, law, and political sciences has several names

such as economic imperialism, neoliberal hegemony, economic rationalism, and

new managerialism. The desire to influence and dominate other academic disci

plines goes to the extent to reshape and redesign other disciplines according to its

own needs. Surely, the idea of economic imperialism is not new. For instance, in

the 1930s Ralph Souter suggested that

the salvation of economic science in the twentieth century lies in an enlightened and

democratic economic imperialism, which invades the territories of its neighbors, not

to enslave them or swallow them up but to aid and enrich them and promote their

autonomous growth in the very process of aiding and enriching itself. (Cited in

Swedberg 1990, p. 14)

Although the trace of this understanding can be found in the early literature,

the idea of economic imperialism has gained momentum in a new form at an

unprecedented speed after the introduction of HCT around the 1950s. Interestingly

enough, Becker does not deny economic imperialism and maintains that econo

mists can talk not only about demand and supply but also about family, crime,

prejudice, guilt, and love. Becker (1993b) says that "it is true. I am an economic

imperialist. I believe good techniques have a wide application" (para. 1).

Economic imperialism has solidified its position by the help of HCT. The hall

mark of this understanding can be seen on many disciplines, but particularly on

the political discourse. It has so profoundly permeated in politics that education is

being perceived by politicians as a survival tool to cope with economic uncertain

ties (Stuart, 2005). To some politicians, education is the engine of economic

growth. For instance, Tony Blair said that "education is the best economic policy

that we have" (Department for Education & Employment, 1998). This under

standing has led to the criticisms that education/training is regarded by policy

makers as an economic instrument for social control and as a stick to move benefit

claimants into the labor market (Coffield, 1999; Darmon, Frade, & Hadjivassiliou,

1999). The British PM David Cameron provided an example to justify that criti

cism. In his speech on the earn or learn programs for unemployed people,

Cameron (BBC, 2013) said that the government would "nag and push and guide"

benefit claimants away from a life on the dole. This attitude is called responsibili

zation by the Foucauldian school, which is an adaptive strategy in which individu

als and communities are urged to play their own part (Rose, 1999). The language

in the quote below is a clear example of the responsibilization phenomenon:

428

This content downloaded from

54.189.126.232 on Sat, 30 Mar 2024 01:07:19 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Human Capital Theory

All people, young and old, are firstly and naturally responsible for themselves. You

have to learn how to take care of yourself, and therefore you must want to acquire

the knowledge and skills to do that. Those who do not take part will be reminded of

their responsibilities. (Netherland Ministry of Culture, Education and Science,

1998, cited in Coffield, 1999, p. 9)

Second, though inextricably linked to the first point, it is argued that education

has been relegated to a mere supplementary component of business and industry.

Education is no longer conceived as an integrated strategy to promote freedom,

self-enrichment, and human development, but rather it is a business activity

driven by profit (Nussbaum, 2010) or a commodity in the market (Ball, 2010).

Thus, students and parents are consumers, teachers are producers, and education

administrators become entrepreneurs and managers whose goal is to meet the

rapidly changing needs of industry (Marginson, 1997). The trace of this approach

can be seen in some official papers:

We expect new courses to offer increased value for money, as they will be delivered

by a range of providers with different business model. . . . Higher education

institution and representatives of an industry sector can [collaborate and] set

standards for course content.... Graduates are more likely to be equipped with the

skills that employers want if there is genuine collaboration between institutions and

employers in the design and delivery of courses. (Department for Business

Innovation and Skills, 2011, pp. 7, 39)

It is true that, at least in theory, education will increase the skills, adaptability,

and mobility of individuals, which in turn will reduce unemployment. This will

eventually contribute to the well-being of individuals and society. However, to the

critics (Coffield, 1999; Field, 2000), unlike welfare state policy goals, the main

objective of the economy-driven education policies is to put the burden on peo

ple's shoulders and expect them to take action for themselves, by themselves.

Namely, the ultimate objective is to reduce the government's financial burden

(Field, 2000). This approach stems from the neoliberal understanding which tends

to see individuals as economic actors and focuses on enabling citizens to contrib

ute to production rather than relying on social welfare state. To that end, the neo

liberal approach moves resources away from social welfare functions toward

production functions (Slaughter & Rhoades, 2004).

One of the ways to positively intervene production functions is to increase

labor quality. This brings the question as to what is the most efficient way to

increase labor quality and productivity. Education is the most appealing answer to

this question for many. This answer is vehemently supported by human capital

theorists and readily accepted by policy makers. In his speech, while talking about

unemployment and the needs of the 21th century, Blair (1999) said that "so today

I set a target of 50 per cent of young adults going into higher education in the next

century." This target was not met by the specified time, which was 2010. However,

what is obvious is that now there are a considerable number of university gradu

ates with overeducation or employed in a low job (Groot & Maassen van den

429

This content downloaded from

54.189.126.232 on Sat, 30 Mar 2024 01:07:19 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Tan

Brink, 2000). The inflation in the academic degrees has not brought the predicted

economic outcomes while churning out overeducated but underskilled or over

educated but underutilized individuals who can barely find a job. This 50% target

has "driven down standards and devalued the currency of a degree and damaged

the quality of the university experience" according to the Association of Graduate

Recruiters report (BBC, 2010). Consequently, the abundance of educated work

force has led to an increase in the number of graduates getting nongraduate jobs

(Walker & Zhu, 2005).

Not only in United Kingdom but also in many other countries including the

United States, Germany, Holland, Spain, and Hong Kong, a considerable number

of studies provided strong evidence for the overeducation phenomenon (see

McGuinness, 2006, for a concise literature review of 33 studies).

However, HCT economists insisted that educational attainments may not pro

duce expected outcomes in the short-run but a convergence between academic

qualification and the predicted wage will gradually take place. In other words,

overeducation is a temporary phenomenon and education will pay off in the long

term once the transition period is over. But this argument is not substantiated by

empirical studies. For instance, Battu, Belfield, and Sloane (2000) examined

whether overeducation is a transitional occurrence or not and their findings did

not support the argument that overeducated graduates can upgrade themselves in

the long run. On the contrary, overeducation appears to be a substantive and dura

ble phenomenon. In addition to that, there are empirical studies which discovered

that overeducation is associated with low productivity and high propensity to quit

due to dissatisfaction with the job. A number of studies (Quintini, 2011; Tsang,

1987; Verhofstadt, De Witte, & Omey, 2007) found that there is a significantly

negative correlation between overeducated employees and their productivity

since unused academic skills affect the outputs adversely. Therefore, overeduca

tion is a matter of concern not only for the individual and the firm but also for the

government itself in terms of effective allocation of public money.

It calls into question that why is the human capital approach so popular among

politicians and bureaucrats if it has not yielded the predicted outcomes in many

examples. Coffield (1999) contended that the anticipations are so high that educa

tion is expected to function in multiple ways. For example, education is viewed as

an instrument which will bring a real transformation to individuals and society

(European Parliament, 2000). It is seen as a means of innovation which will

increase economic competitiveness and will lead to a knowledge-based economy.

Education is a social policy designed to terminate social exclusion. It is expected

to make individuals more flexible and adaptable to the needs of ever-changing

world of work. But what is the source of these high anticipations from education?

Coffield (1999) provides four reasons for that. First, it deflects attention from the

need for economic and social reform. As Schuller and Burns (1999) reminded that

"investment in human capital by an employer or by society requires the appropri

ate social context in order to be realised effectively" (cited in Coffield, 1999,

p. 483). Second, it provides politicians with the pretext for action so that they can

justify their education and social policies with this appealing pretext. Third, it

legitimizes increased expenditure on education. Karabel and Halsey (1997) note

that positioning education at the root of economic and social problems justifies for

430

This content downloaded from

54.189.126.232 on Sat, 30 Mar 2024 01:07:19 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Human Capital Theory

the necessity of a substantial amount of public expenditure on education. This

enables education ministers to secure resources from treasuries. Last, it offers the

comforting illusion that for every complex social and economic problem there is

one simple solution (Hodkinson, Sparkes, & Hodkinson, 1996).

In conclusion, HCT has been criticized on the grounds of economic imperial

ism since it has penetrated into the territory of other disciplines and attempted to

lead them. Another criticism is that it has centered education around the needs of

business and viewed education as a survival tool to cope with economic uncer

tainties. Furthermore, it has created the illusion that education can solve any kind

of problems on its own.

What is the role of HCT in creating this illusion? It is worth remembering that

the basic assumption of HCT is that education is good. However, the practical

question that needs to be asked is not whether education is good or not. The real

question is that is more education always good (Wolf, 2002)? Or it is just self

evidently true that knowledge is preferable to ignorance in the same way health is

preferable to illness, freedom to slavery, and peace to war. HCT has strongly

given the impression that governmental expenditures directed toward the realiza

tion of these preferences have a linear relationship to their economic profitability

(Shaffer, 1961). It has been shown that this linear relationship in theory does not

always exist in practice. Second, another important question to ask is "not that

education contributes to growth, but that more education would contribute more

to growth at the margin than more health, more housing, more roads, etc" (Blaug,

1987, p. 231). Finally, HCT has provided rather accessible and palatable intellec

tual ammunitions to politicians by which policy makers can form an educational

policy placing economic concerns at the very center of it.

The neoclassical approach, economy-driven education or more interestingly

economy-driven life, has also raised some moral questions that will be discussed

in the next part.

Moral Criticisms

The moral aspect of HCT is rather controversial and the controversy comes

from the meaning that the neoclassical school of thought attributes to human

beings and the referential framework by which this intellectual tradition analyzes

human actions and goals. In that regard, the idea of human capital has been bit

terly criticized and sometimes sarcastically referred as human cattle. This section

will look into the moral criticisms of HCT and is organized mostly around

Foucault's account of human capital.

First of all, it would be appropriate to dissect HCT into its basic components.

Foucault (1979) argues that human capital represents two interrelated processes:

"one that we could call the extension of economic analysis into a previously unex

plored domain, and second, on the basis of this, the possibility of giving a strictly

economic interpretation of a whole domain previously thought to be non-eco

nomic" (p. 219). Traditionally, the inputs of production, in the classical analysis,

were land, capital, and labor referring to the number of workers and hours. A

laborer was simply seen as a person of exchange who sells his or her labor power

and renounces a specified amount of his or her time in exchange of a wage deter

mined by the market at a given time. However, in HCT, the individual is

431

This content downloaded from

54.189.126.232 on Sat, 30 Mar 2024 01:07:19 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Tan

considered an enterprise who allocates his or her scarce means (time, labor) to the

maximization of utility. Thus, HCT views human beings as active economic sub

jects as opposed to the traditional view that saw human beings as objects—the

objects of supply and demand in the form of labor power (Foucault, 1979). This

is the first novelty that HCT introduced: a shift from labor power to an active