Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Wilcocks 1931 Intelligence Environment and Heredity

Uploaded by

Divya Dewangi0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views14 pagesOriginal Title

wilcocks-1931-intelligence-environment-and-heredity

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views14 pagesWilcocks 1931 Intelligence Environment and Heredity

Uploaded by

Divya DewangiCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 14

63

SOUTH AFRICAN JOURNAL OF SCIENCE, Vol. XXVIII, pp. 6.'3-76,

November, 1931.

INTELLIGENCE, ENVIRONMENT AND HEREDITY.

BY

R. W. WILCOCKS, B.A., PH.D.,

Professor of Psychology, University of Sfellenbosch.

Presidential Addresil to Section F, delivered 9 July, 1931.

Ordinary experience and the results obtained by the applica-

tion of int,elligence tests clearly show that wide differences of

intelligence, or intellectual efficiency, exist between individuals.

On the whole there is a tendency for the impression to be created

that such differences are still to be found between individuals

when environmental influences acting on them before and after

birth have been, at least apparently, in the main the same.

The theory is thus suggested that these differences must, wholly

or very largely, be due to differences in the germplasm itself

when unaffected by what are to be looked upon as abnormal

circumstances. That is, the differences are, in the first place,

due to differences of heredity. This theory undoubtedly receives

support from the fact that, as Weintrob and Weintrob G4 have

Reproduced by Sabinet Gateway under licence granted by the Publisher (dated 2010).

shown, unfavourable environmental conditions may be accom-

panied by a relatively high degree of intellectual efficiency as

measured by intelligence tests, and that more favourable environ-

mental conditions may be accompanied by relatively low degrees

of such int.ellectual efficiency. It is hardly necessary to state

that this also is in agreement with ordinary experience. On

the other hand, it may be urged that ordinary experience also

shows t.hat environmental influences bring about marked differ-

ences in intellectual efficiency, that our attempts at education

are based on this very observation, and that individual differ-

ences which we may, at first sight, be inclined to ascribe to

heredity may largely be due to differences in environment which

have been overlooked. Various Jines of research have been

followed in attempting to answer the question which is thus set

us, and the present paper is intended as a statement of the

advances which have been made towards obtaining an answer in

the case of human beings. A great mass of evidence has been

collected which makes it impossible to doubt that positive cor-

relations exist between blood relations with regard to intellectual

efficiency. We cannot do more than indicate shortly, by way of

examples, the main types of researches and :findings in this

connection. The work of Dugdale l l forms an illustration of one

type of research. His study of the " Jukes " was carried on

later by Esterbrook14 to cover more than 1200 individuals belong-

ing to the same family and then living. Of these it was found

that some 40 per cent. possessed only a relatively low degree of

intelligence and another 16 to 17 per cent. are classified as of the

64 SOUTH AFRICAN JOURNAL OF SCIENCE.

feeble-minded type. Similar results were obtained by Goddard

in his study of the " Kallikak " family23, and further corrobo-

rative findings were reported by him in his study of feeble-

mindedness,u tl~ough the question may safely be left in abeyance

at present as to the degree of success with which Mendelian

concepts are applied by. him to his findings. The study of the

" Hill-folk" by Danielson and Davenport 8 gives further proof,

if any were needed, of the tendency towards resemblances

between blood relations in cases of 19W intelligence. Similar

evidence is available with regard to the opposite pole of ability.

We shall refer to the work of Galton on this point in another

connection. According to Kretschmer38 Rath has traced the

close blood relationship which existed between a number of

famous Swabian poets and philosophers, and Sommer 51 has

shown, in his study of Goethe's genealogy, the presence of a

number of gifted ancestors. In this connect,ion too the works of

Candolle5 and Mobius"" have to be mentioned with regard to the

occurrence of great mathematical ability in the Bernoulli family.

Following a different method of research, and making use of

the estimate of the intelligence of pupils by their teachers,

Pearson"'''' obtained correlations of ·44 to ·45 in the case of

siblings. Schuster and Elderton,58 making use of material col-

lected by Heymans and Wiersma'" by the questionnaire method,

obtained a correlation between fathers and sons with regard to

school performance of ,35. Burris" obtained somewhat smaller

Reproduced by Sabinet Gateway under licence granted by the Publisher (dated 2010).

correlations between siblings with regard to school performance

in different subjects, but, still, the correlations were positive,

and the same holds true for the findings of Thorndike 62 in, for

example, arithmetic. Pintner"'8 found positive correlations in

intelligence test performances between siblings, though these

were decidedly smaller than those obtained by later and mor~

reliable researches, and Cobb's8 data showed the presence of

positive correlations between the performances in arithmetic of

parents and children. Downey9 making use of intelligence tests

found that 80 per cent. of children with parents of more than

average intelligence also show more than average intelligence,

whereas in another group, where both parents were of only aver-

age intelligence, or where only one parent was of more than

average intelligence, only 33 per cent. of the children showed

more than average intelligence. Gese1l 20 making use of intelli-

gence tests found, for a pair of like·sex twins, practically the

same high LQ. for them at the ages of seven and eight.

Recently .Tones and Burks 12 find a correlation with regard to

intelligence of ·55 between parents and offspring living in the

same house.

Occasionally, in some of the earlier work (8 and 48) the

authors seem inclined to consider their positive correlations

between blood relations as evidence speaking strongly in favour

of the presence of a hereditary factor. It is, however, clear that

the positive correlations obtained in these and similar researches,

PRESIDENTIAJ. ADDRESS-SECTION F. 65

while indicating the possibility of heredity as a causal factor

determining the degree and nature of mental efficiency, cannot,

by themselves, be taken as proof positive that such is actually

t.he case. Neither do the limitations in the size of the correla-

tions found exclude the possibility that heredity may be much

more important in determining intellectual efficiency than would

be indicated by the size of the correlations found among blood

relatives. 29 It can hardly be doubted that agreement with regard

to blood relationship tends to be accompanied by agreement with

regard to environmental factors, and, pending further evidence,

these latter might be looked upon as the cause of any positive

correlations in intellectual efficiency which are found to exist

among blood relatives. So, for example, the American Army

results 68 with intelligence tests, have established the fact that a

clear association exists between the socio-economic status of

adult males and their intellectual efficiency 'as measured by

intelligence tests. A large number of researches leave no room

for doubt that children of parents of different socio-economic

levels tend to differ in a similar way with regard to their intel-

lectual efficiency. The most important studies to be mentioned

in this connection are those of Duff and Thomson,1° Collins 7 and

Haggerty and Nash. 32 It may be added that the results obtained

by the present writer from the application in the Union of the

South African Group Intelligence Tests to 3281 " poor white ..

childr~n of the ages 120 to 150 months show their average LQ.

Reproduced by Sabinet Gateway under licence granted by the Publisher (dated 2010).

to be 93·3. A number of researches (~arried out on a smaller

scale have shown similar results, both with regard to intelligence

tests and school performance, for example, those of MacDonald u ,

Hartnacke,33 others summarised by S'tern,59 Kornhauser,37

MusterS' and others. While, undoubtedly, these findings would

agree well with the theory that a poorer innate equipment is a

predominant factor in determining the parents' socio-economic

status, and that this poorer equipment tends to be produced in

his offspring, the possibility of the opposite view can, on such

data taken alone, not be gainsaid. Aecording to this opposing

view unfavourable environment would, in the main, have deter-

mined both the intellectual effi,ciency and the socio-economic

status of t.he parent, his child would live under similarly unfav-

ourable circumstances, and would thug also tend to show rela-

tively poor intellectual performance.

In another type of procedure which appears to offer some-

what more conclusive results, the attempt is made to follow the

method of concomitant variations. The main fact which has

been established is that the degree of correlation in intellectual

efficiency between blood relatives tends to vary with the degree

of blood relationship. In his pioneer work GaIton17 already

found, as is well known, that men of great ability tend to have

a much larger number of blood relatives of great ability than

ean possibly be explained by chance, and that this number tends

clearly on the average to be greater according to the degree of

66 SOUTH AFRICAN JOURNAL OF SCIENCE.

closeness of the blood relationship. Schuster and Elderton 55

found that the agreement with regard to scholastic and academic

success was greater in the case of brothers than in the case of

fathers and sons. Peters 47 in comparing the school performance

of blood relat.ives found a greater resemblance between siblings

than bet\\'een children and parents or sons and fathers. The

correlation between grandchild and grfudparent was still smaller.

Assembling the data from various authors with regard to the

concomitanpe in the variations of closeness of blood relationship

and the size of the correlations of intelligence quotients between

such relatives, Wingfield and Sandigold 66 are able to show that

this concomitance is a very dose and regular one, varying from

·90 in the ease of physically identical twins to ·16 in the case of

grandparent and grandchild. These authors conclude that there

is an increasing degree of resemblance in general intelligence

among human beings with an increasing degree of blood relation-

ship among them, and that general intelligence is, in conse-

quence, an inherited trait.

Strictly speaking, however, the method of concomitant varia-

tions must demand that only one of the antecedents shall vary

concomitantly with the effect to which the antecedent is ascribed

as cause. Hence we are at a loss as soon as two or more ante-

cedents show similar concomitance with the effect in question.

It is reasonable to accept that, on the whole, there will be some

tendency for environment to vary in a concomitant way with

Reproduced by Sabinet Gateway under licence granted by the Publisher (dated 2010).

blood relationship. Notwithstanding exceptions, the socio-

economic status of the pRrent tends, on the whole, to be repeated

in the offspring. So also, as, e.g., 1~errin46 and Thurnwald 63

have shown, there is some tendency for sons to follow the calling

of the father and we cannot avoid accepting that such factors as

family tradition and parental example are important environ-

mental influences bringing about correspondence in this respect.

The question thus arises as to the degree of concomitance between

environment and intellectual efficiency. To this question we

return at a later stage.

The results of the study of the correlations between blood

relatives do, however, obtain a new significance for our problem

if they can be combined with a successful attempt to eliminate

environment as a differentiating fnctor. Before proceeding to

the discussion of attempts which have been made in this direc-

tion, we find it convenient to pass on, first of all, to iPearson'sH 45

comparison between the amount of correlation he found between

the intelligence of siblings and that found between various physi-

cal characteristics. He collected data for a large population of

siblings, making use of teachers' estimates of intelligence. Con-

siderable differences of socio-economic level were present between

the different groups of siblings. The correlation between the

intelligence of the siblings was dosely in the neighbourhood of

'50, which agreed closely also with his findings in the case of a

number of physical characteristics of siblings. Pearson argue!"

PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS-SECTION F. 67

that at least some of the resemblances, e.g_, in hair and eye

colour, in the case of physical characteristics cannot possibly be

dUt? to home influences and must be due to common heredity.

Moreover, he concludes we are forced to the conclusion that the

correlation between the intelligence of siblings, being so closely

the same as that found for physical characteristics, must also be

due to a common heredity _ Other later resellrches, carried out

by more objective methods of determining intelligence, have,

however, sometimes given markedly higher correlations than that

found by Pearson when environment was present as differentiat-

ing factor between different groups of siblings. Thus Thorndike u

recently obtained a correlation of -60 in this case.

In continuing the researches on the correlation between the

intelligence of blood relatives, Schuster and Elderton,5' in their

work to which we have previously referred, limited their popula-

tion groups to, broadly speaking, the same socio-economic levels.

The correlations between the intelligence of brothers was in the

neighbourhood of '4, but it is pointed out that the relative small-

ness of these correlations should reasonably be ascribed to limita-

tion of the range of lalent, in which case the difference between

the results obtained by Schuster and Elderton on the one hand

and Pearson on the other cannot be ascribed to the differentiating

influence of environment. Pearson,H further, making use of

the results of intelligence tests obtained by Gordon 30 with orphan-

Reproduced by Sabinet Gateway under licence granted by the Publisher (dated 2010).

age children, i.e., children living in a highly uniform environ-

ment, obtains a correlation of ·51 between the intelligence of

siblings. This clearly agrees closely with his own findings,

already mentioned above, where differences of environment were

present as possible differentiating factors. This result is looked

on by Pearson a.s a further very strong corroboration of the view

that intelligence is inherited. It may be mentioned, in this

connection, that the present writer 65 also found a correlation of

·5 between the intelligence of siblings as measured by the South

African Group Intelligence Tests where considerable differences

o~ socio-economic status were present between different groups of

siblings. Further data, obtained by means of intelligence tests

by Gordon 31 with sibling orphanage children, give a correlation

of ·540 according to the method of statistical treatment given to

Gordon's data by EldertonY Data collected by Drinkwater on

the intelligence of siblings, both by means of the estimate of

teachers and by means of intelligence tests, are also treated

statistically by Elderton. 13 While at least a portion of the data,

as Elderton clearly shows, present anomalies, the attempt is

made to sum up the results. Where there are clearly wide

environmental differences between different groups of siblings,

the eorrelations obtained bv Elderton varv from -384 in the case

of the relation sister-sister (by teacher's estimate of intelligence),

to . 552 for the brother-sister relationship (by intelligence test

measurement) .

68 SOUTH AFRICAN JOURNAL O}<' SCIENCE.

Summing up the results of this group of researches we may

say, in general, that while there is a good deal of variation in the

size of the coefficients of correlation, they do certainly remain

approximately of the same order of size, and, more particularly,

that this is the case when correlations, with environment as

possible differentiating factor, are compared with those obtained

when this diffel'entiating factor is largely eliminated or, at least,

somewhat decreased. On the whole, then, it may safely be said

that they strongly tend to show that heredity is an important

factor in determining the level of intellectual efficiency.

Studies of twins have undoubtedly thrown further light on

the problem at issue. 'l'horndike 62 comparing, in the mail\,

scholastic performance of twins as determined by tests, did no't

find that, on the whole, older twins show greater resemblance

than younger twins. He holds that older twins should show a

greater amount of resemblance than younger twins, if environ-

ment is important, since the older twins would have been sub-

jected to the same environment for a longer time. He also points

out that siblings not differing much in age show much greater

differences than twins. His interpretation of these findings is

that by far the greatest amount of the resemblance between

twins must be due to their original nature, this being in agree-

ment with an earlier finding of Galton, using less objective

methods. 16 Merriman,.u in a study of twine by means of intelli-

gence tests, obtains a result agreeing with that of Thorndike,

Reproduced by Sabinet Gateway under licence granted by the Publisher (dated 2010).

although valid objections have been made 52 to some aspects of

the statistical treatment of his data. Similar objections have

been raised by Wingfield and Sandigold 68 to the work of Lauter-

bach 39 on twins. But Lauterbach's results do still agree in

principle with those of Thorndike. Wingfield and Sandigold's

own data clearly support those of Thorndike, since they find

that a group of twins from 12 to 15 years old do not, on the

whole, resemble each other more in mental efficiency than a

group of twins from 8 to 11 years old. As in the case of Thorn-

L. dike's research, they also found that twins do not show more

likeness in subjects where the school has concentrated its training

than in respects in which this is less the case, namely, in intelli-

gence test performances. Their conclusion is that environment

is inadequate to explain the mental resemblances between twins.

One objection to their work that may be raised arises from the

fact that the correlation for unlike-sex twins is approximately of

the same size as that for siblings. This finding is explicitly

drawn attention to by the authors and is found in their own

results. We have, however, not been able to find in how far

this finding has been taken into account by them in comparing

the older and younger groups of twins. It is clear that a com-

parative preponderance of either identical or non-identical twins

in either the younger or older groups would seriously affect the

size of the correlations obtained. However. Wingfield and

Sandigold, as also Tallman,12 also find that identical twins show

PRESIDEXTIAL ADDRESS-SECTION F. 69

a higher degree of resemblance than fraternal twins, the correla-

tion in the one case being ·90 and in the other ·70 as measured

by intelligence tests. Should we be justified in a.ssuming that

environmental, and especially pre-natal environmental condi-

tions, are practically the same on the average, for pairs of like

twins on the one hand and pairs of fraternal twins on the other

hand, then the difference between these correlations must be

due to heredity. It is not, however, clear to what extent this

assumption is justified. Tallman finds that the difference

between like and unlike twins is smaller than that between

unlike twins and siblings. On the assumption that the heredi,

tary similarity between unlike twins and siblings is the same,

we should have to explain the increased resemblance in the case

of unlike twins, as compared with siblings, to environmental

influences. Here again the question arises as to the extent to

which our assumption is correct. Koch12 finds in the case of

a pair of Siamese twins that the divergence shown by them on

intelligence test results is just about the same as that found in

the case of ordinary like twins. Here we ha.ve a case of a prac-

tical maximum of uniformity of environment. Should the dif-

ference between these Siamese twins have been markedly

less than that found in the case of ordinary identical twins, the

case examined by Koch would tend to show, as far as one case

can do so, that environmental circumstances are of importance

in bringing about similarities in intelligence. It is possible, on

Reproduced by Sabinet Gateway under licence granted by the Publisher (dated 2010).

the other hand, to interpret Koch's actual findings in the sense

that the environmental conditions, under which Siamese twins

live, are, comparatively, not much more similar than those

usually present in the case of ordinary identical twins. If so,

then Koch's findings would be inconclusive with rega.rd to the

importance, or otherwise, of environment.

Summing up our account of the work with twins we would

say that none of the findings give positive support to a theory

according to which similarities of environment would be the

chief factor in determining the similarity of twins. On the

other hand, if we take the data on twins alone, or in conjunction

with other data already discussed, they by no means exclude

the possibility of more marked differences of environment (than

were present as possibly differentiating factors in the cases of

the twins studied) bringing about marked differences in'intel-

lectual efficiency. The findings do, however, agree with those

mentioned earlier in showing that there is a concomitance of

variation between intellectual efficiency and heredity.

A further line of attack on the main problem consists in

attempting more specifically to get the correlations between

environmental fadors and intellectual efficiencv. Heron 34 found

only very small or insignificant correlations between the intelli-

gence of school children and cleanliness, nutrition, glands,

tonsils and condition of teeth. None are nearly comparable in

size with those found for the resemblance between siblings in

70 SOUTH AFRICAN JOURNAL OF SCIENCE.

the case of in~elligence. Elderton!3 adduces further data show-

ing similarly small or insigniffcant correlations between intelli-

gence of children and intelligence and drinking of father, or

mother, morality of parents, physical condition of parents, eco-

nomic condition of home and overcrowding. The fact that Ia.ter

researches have clearly established an association between socio-

economic status of parents and the intelligence of their children,

make it impossible to accept these data as conclusive proof of

the unimportanee of environment. It may, in addition, justly

be urged that isolated aspects of the environment might give

no or small correlations with the intelligence of children, and

that, at the very least, such data should be subjected to treat-

ment by multiple correlation meth.9ds. So, for example, in the

Stanford studyl2 of foster children, the multiple correlation

between the foster children's 1.Q. and various features of the

environment had a value of ·42. Terman"! does indeed state

that tonsil and adenoid troubles seem to have little effect on

the 1.Q., but recently Matthew and Luckey!2 studied some cases

in which changes of some points in LQ. were readily explicable

us caused by medical complications. On the other hand, Hoefer

and Hardyl2 did not find clear improvement in either I.Q. or

E.Q. in the case of several hundred children as result of steps

taken to improve their physical condition. The results of an

investigation reported by Fick!5 agree with these findings. lsser-

lis,3s making use of data collected by Wood, found compuratively

Reproduced by Sabinet Gateway under licence granted by the Publisher (dated 2010).

large correlations on the one hand between teachers' estimate of

intelligence, standurd in school, und intelligence as measured by

tests, and, on the other hand, clothing of children, economic con-

dition of home and care of home. These correlations certainly

seem to open up the possibility of improvement in environmental

circumstances improving the intelligence of children. Hildreth,!2

Goodenough l2 and Heilman!2 do not appear to have found statis-

tically significant differences in the 1. Q. between groups of young

children some of whom hud, and some of whom had not, attended

nursery or kindergarten schools before proceeding to what we

should call the primary school. Gowen and Gooch 29 also did not

find that college students who had attended a better class of high

school showed better performance in their studies at college than

those who had attended a poorer class of high school. They also

found that performance in college is correlated with the perform-

ance of the individual in high school, and from this they conclude

that the largest element in subsequent college performance is the

individual's innate capacity and not the environment into which

he may have been thrown previously. Their sweeping conclusion

is by no meuns .i ustified by their data. At most, their data

would show that the differences between the high schools in ques-

tion were too small to have an uppreciable effect on later college

performance. Schmitt 54 in a publication on the subject, stutes

that he found that children, from the poorer classes, who had

been placed in institutions (Fiirsorge-Anstalten) i.e., under

PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS-SECTION F. 71

improved environmental conditions for some years, showed no

better intelligence test performances on the average than the

relatively low ones ordinarily found with children belonging to

the lower soeio-economic levels of society. His conclusion is

that heredity must, at bottom, be responsible for the low I.Q.

found on the average with this class of child. Sehmitt did not,

however, have thoroughly standardised intelligence tests at his

disposal and his results do not exclude that the possibilities of

larger numbers ilnd more dellcate instruments of measurement

might show a differenee in I.Q. accompanying improvement of

environment. It must, however, be added that Rogers12 also

found that transference of children from a distinctly unfavour-

able environment to the favourable one of an excellent institution

did not, at least aftet· a year of the new environment, bring about

an improvement in their I.Q.

In summing up the results of the researches just discussed

it is clear that apparently marked changes and differences of

environment do not affect the 1.Q. of children to any great

extent; indeed we may say that they do so, at m08t, to only a

small extent. We have, however, also to take into consideration

how large these environmental differences are in comparison with

the amount of environment which is present but non-differentiat-

ing, because common to all. The question then becomes how big

an apparently marked change or difference in environment really

Reproduced by Sabinet Gateway under licence granted by the Publisher (dated 2010).

is It cannot reasonably be doubted that very big changes in

environment must affect mental efficiency and so also perform-

ance on a mental test. Our mental asylums offer plenty of cases

where intelligence is radically and permanently affected by infec-

tious disease, and it would be unreasonable to doubt that long

continued and extreme malnutrition will have a very deleterious

effect. Or, to take another type of case, the South African Group

Intelligence Tests presuppose the ability to read, and a child who

has, through laek of educational facilities, lagged behind in this

ability will, for this reason alone, make a poor showing on the

test. Findings such as those of Murdock and Maddow 12 and

Petersen,12 indicating an absence of the so-called language handi-

cap ])ave, thus, only limited validity. We have, then, to fisk

what data are available on the constancy of the I.Q. when

environmental changes of an undoubtedly major charader are

introduced. The fact that the I.Q. remains at least relatively

constant under ordinary circumstances has been shown by such

work as that of Terman,S" Rugg,'l Rugg and Col1oton,'" Garri-

son," Rogers, Durling und MacBride" and is to-day, of ('ourse, a

\\'pl1-known fact.

An illusory attempt to determine the influence of major dif-

ferences of environment on the I.Q. and thus, by implication, on

its constancy, has recently been published by Sims.53 He finds

that siblings reared in the same home show a correlation of ·45

between their] .Q.s as determined by an intelligence test. Unre-

lated pairs equnted with the siblings on the basis of age and

5

72 SOUTH AFRICAN JOURNAL OF SCIENCE.

home background, and attending the same school as the siblings,

show a correlation between their I.Q.s of something in the neigh-

oourhood of ·30. His conclusion is that out of the total correla-

tion of ·45 found between siblings, ·30 must be ascribed to simi-

larity of environment and ·15 to heredity. It is, however, obvious

that Sims has overlooked that, while in this way eliminating

identity of parentage, he has by no means eliminated similarity

of heredity, since it can hardly be denied that, on the whole, the

different levels of socia-economic status of the parents may cor-

relate in a positive way with hereditary fact.ors making for higher

intelligence not only in their own case but also in the case of

their children.

In the recent so-called Stanford and Chicago investigations l2

with foster children, the procedure followed consisted of attempt-

ing to determine what changes in the I.Q. of foster children took

place in connection with their placement in the new foster

environment. In the Stanford investigation Burks finds in

respect of intelligence, a correlation in the case of foster children,

adopted in the first few months of life, with the adopting fat,her

of ·09 and with the adopting mother of ,23. If we could be quite

certain that no selective influences were at work tending to let

the more intelligent class of parent get the more intelligent

foster children, these ~orrelatiolls, in so far as they are statistic-

ally reliable, would have to be ascribed to environmental influ-

Reproduced by Sabinet Gateway under licence granted by the Publisher (dated 2010).

ences; Terman;"1 in discussing the question of selection, admits

that extraneous factors were so carefully controlled that the data

is about as crucial as it is humanly possible to secure, number of

cases considered, but holds that there is a bare possibility of even

the small correlations found being due to selective placement.

The average I.Q. of the Stanford group of foster children is 107·4.

Since a reasonable estimate of the intelligence of the parents

would· put their I.Q. at, say, approximately 100, it would appear

that the more favourable environment of the foster homes had

effected an improvement of some 6 to 8 points. Unfortunately,

the estimate of the intelligence of the parents is a rather specu-

lative one. Freeman, Holzinger and Mitchel\12 obtained results

in the case of the Chicago investigations which, in the main,

agree with those obtained in the Stanford invcst,igation. The

average I.Q. of the foster children in thifl 'case is 97'5, but they

were adopted later in life than those of the Stanford group, and

it is estimated that the avernge intelligenee of t,heir parents is

also considerably lower than in the case of the Stanford group.

Unfortunately. here, too, the estimate of the parents' intelligence

is of a somewhat speculative nature It WI1S further found in the

Chicago investigation that, where 130 sib pairs had been sepa-

rated, one being placed in a superior home and one in an inferior

home, those placed in the superior homes averaged 9 point,s

higher than those placed in the inferior homes. There can hardly

be any doubt that selective plaeement has played a role in givinll

this result, since, as Terrnan 61 points out, there was a correlation

PRESIDENTTAL ADDRESS-SECTION F. 73

of ·34 between foster parents and foster children at the time of

adoption. Selective placement may possibly also account suffi-

ciently for the fact that correlations of from ·25 to ·34 are found

between unrelated foster and" own " children living in the same

home. This remark also applies to the fact that the correlation

between foster and own children in the same home was found to

be ·37. There are, however, other findings in the Chicago study

which cannot be explained in this way and which, on our view,

must be interpreted as showing that improved environment appre-

ciably affects the I.Q. Thus, in the case of 74 children placed

in foster homes at the age of eight years, the average I.Q. at the

time of adoption was 95 and after four years it was 102·5. Those

going to better homes improved up to 105. In the less favourable

homes the I.Q. rose to 100·5. Moreover, siblings who had been

separated and brought up in different homes showed less resem-

blance than siblings in general do. This indicates that the

resemblance of siblings is due in part to similar environment. In

agreement with this, it, was found that siblings who had been

separated late diffend less than those who had been sepamted

early, and corresponding findings were obtained for those who had

been separated a longer and a shorter time respectively. In addi-

tion, those who had been placed in similar homes differed less

than those who had been placed in homes which were dissimilar.

On the whole, then, we have to conclude, from the data before us,

Reproduced by Sabinet Gateway under licence granted by the Publisher (dated 2010).

that major, even though not extreme changes in environmental

circumstances do have an apprJ')ciable effect on the size of the

T.Q. The size of such changes in I.Q. is, however, quite limited

for major changes of the order under discussion. That this

should be so is indicated by the general trend of other researches

that have been discussed, and a further corroboration is obtained

from the work of Goodenough. 25 It has already been pointed

out, for the case of children of school age, that their general

level of I.Q. tends to vary with the socio-economic status of the

parents. Should this, in the main, be the effect of environmental

factors, we might reasonably expect younger children from dif-

ferent socio-economic levels to show less difference. The work

of Goodenough shows that, for children of from two to four years

of age, the differences are quite of the same general size as in

the case of school children.

Finally, we wish to refer shortly to the result obtained by

the present writer in South Africa. Use was made of the South

African Group Intelligence Tests, the norms for which have been

worked out on the basis of the tests results of nearly 17,000

European children in t,he Union, care being taken to make the

norms as nearly as possible repre$entative of the European popu-

lation. It was found that the average I.Q. of 3,281 .. poor

white" children, from the ages 120 to 155 mont.hs shows clear

tendency to sink with increase of chronological age. The follow-

ing table gives the main facts:-

74 SOUTH AFRICAN ,JOURNAL OF SCIENCE.

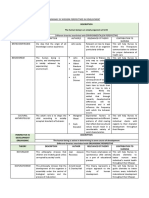

Age. No. tested. Aver. I.Q. SD of Dist.

120-123 356 95'4 II'4

124-127 341 95'4 11'8

128-131 351 95'1 12'2

132-135 357 92'6 12'6

136-139 328 93'5 II'4

140-143 338 94'0 II'3

144-147 404 92'7 12'25

148-151 395 91'4 12'3

152-155 411 90'6 12'0

A straight line fitted to the points given by the different

. avenlges by the method of least squares gives an average fall

from one average I.Q. to the next of '5765, that is, a total

fall of about 4'6 points in some three years. Three times the

standard error of the angle of fall is ·195, since<Jt= v'6/k(4k 2 -1)0

= '065. It may then be easily calculated that at the very

least we can be certain, for the three years' time with which

we are hera concerned, of a fall of over 4 points. The most

:r.oasonable interpretation to give to this finding is that the fall

is due to un£avourable environmental conditions und·er which the

poor white child lives.

REFERENCES.

1 AMBROS, R. Die Vererbung psychischer Eigenschaften. .4nJliv.

Reproduced by Sabinet Gateway under licence granted by the Publisher (dated 2010).

f. d. Ges. Psych. ~8, 1913.

• BETZ, W. Untersuchungen von F. Galton K. Pearson u. ihrer Schule

tiber Begabung und VererbUlig. zt. Ano. Psych. 3, 1910.

• BRIDGES, J. W. and COLER, L. E. The Relation of Intelligence to

Social Status. Psych. Review, ~4, 1917 .

• BURRIS, W. P. Heredity, Correlation and Sex Differences in

School Abilities. Edited by E. L. Thorndike. Columbia Univ.

Publications in Philosophy, PsycholoOY and Education, ~, 103.

• CANDOLLE, A. Histoire des Sciences et des Savants depuis deux

Siec!e. 1813.

• COBB, M. V. A preliminary study of the Inheritance of Mental

Abilities. Journ. Educ. Psyc.h. 8, 1917.

7 COLLINS, J. E. Journ. of Ed11C. Research, 17, 1928.

• DANIEI.SON, F. H. and DAVENPORT, C. B. The Hill Folk. Eugenics

Record Office, Memoir No.1, 1912.

• DOWNEY, J. E. Standardised Tests and Mental Heredity. J01l1'nal

of Heredity, 8, 1918 .

.. DUFF, J. F. and THousoN, G. H. The Social and Geographical Dis-

tribution of Intelligence in Northumberland. Brit. Jow'n, of

Psych. 14, 1923.

I I DUGDAI.E, R. L. The Jukes. 1877.

,. Education, Twenty-seventh Yearbook of the National Society for the

Study of. 1928.

" EI,nERToN, E. M. A summary of the Present Position with regard

to the Inheritance of Intelligenl'c. Biometrika, XIV, 1923.

J4. ES'r~RBRooK, A. H. The .Tukes in 1915. 1916.

l5 FWK, M. L. Social and Indust-rial Review (South Africa). 1929.

,. G~L1'OS, F. Hereditary Genil18. 1869.

PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS-SECTION F. 75

17 GALTON, F. Iilquiry into the Human Faculty and its Development.

1883.

,. GARRISON, S. C. Additional Retests by menns of the Stanford Revi-

sion of the Binet Tests. Journ. Educ. PSl/Ch .. XIII, 1922.

" GATKS, A. J. Inheritance of Mental Traits. Psych%yicol Bulletin,

18, 1921.

20· GESELL, A. A psvchological compluison of superior duplicate rwins.

J>.~)/ch. Bulletin, 10, 1922.

" GODDARD, H. H. The Kallikak Family. 19J2.

,. GODDARD, H. H. Feeblemindedness. 1914.

25 GOODENOU('H, F. L. The Kuhlman-Binet Tests for Children of Pre-

school age. 1928.

29 GOWAN, J. 'V. and GOOCH, M. Mental attainments of college

etlldents in relation to preparatory school and lIeredity. Journ.

Educ. Psych. 17, 1926.

30 GORDON., K. P8ychological tests of orphan children. Journ. 0/

DelLllquellcy, XIV, 1919.

" GORDON, K. 'fhe Influence of Heredity on mental ability. 1918-20.

" HAGGKRTY, M. E. and NASH, H. B. Mental capacity and paternal

occupation. Journ. Educ. Psych. 15, 1924.

" HAHTNACKE, W. Zur Verteilung der Schultuchtigsten auf die sozialen

Schichten. Zt. Pad. Psych. 18, 1917.

a. HERON, D. InOuence of defective physique and unfavourable

environment on the Intelligence of school children. Eu(}enic.~

Lab. Memoirs, VITI, 1910.

a. HEYllANS und "'IERSMA. Beitrag zur spes. Psychologie auf Grund

einer Massenuntersuchung. Zt. /. Psych. 4~·48. 1906-7.

Reproduced by Sabinet Gateway under licence granted by the Publisher (dated 2010).

as ISSERLIS, L. (and WOOD, F.) The Relation hetween Home Conditions

and the Intelligence of School Children. Medical Research

Oouncil, Special Report Sene.1. No. 74. 1923.

,. KEU,EY, T. L. The Influence of Nurture upon Native Differences.

1926.

., KORNHAtJSER, A. W. The economic standing of parents and the

intelligence of their children. Jonr1l. RlI1IC. P.~!lch. IX. 1918.

U KUETSCHMER, E. Geniale MenRcheu. 1929.

89 LAUTERBACH, C. E. Studies in Twins Resemblance. (}enet·ics, X,

1925 .

•• MCCOMAS, H. C. Heredity of Mental Abilities. P.'ych. Bulletin. ~.

114 .

.. MACDoNAI.D, A. Eine Schulstatistiek liber Geistige Begab,lDg.

Zt. / Pad. Psych, 14, 1913 .

.. MERRUIAN, C. The Intellectual resemblance of Twins. Psych.

MonOal·aph.~, XXXIII, 1925 .

•, MOBil'S, D. J. Ueber die Anlage zur Mathematik. ~A. 1907 .

.. PEARSON, K. On the Laws of Inheritance in Man. Biometrika, 3,

1904 .

•, PEARSO~. K. Inheritance of Psychical characters. Biomehiko, 1'1,

1918-9.

4d PJo~ltltIN, E. On the Contingency hetween Occupat.ion in the case of

Fathers and Sons. Biometrika, 3, 1904.

• 7 PETEIlS, 'V Ueber Vererbung Psychischer I"iihigkeiten. Fo1"f-

sdu-itte dr.T l's1lr:h%aie. It. litre AnlCellliulta€11. 3, 1915 .

., P~~TEIIR, W. Vererhung Geistiger Eigenschaften u. Psychische Kon-

stitution. 1925 .

.. PINTJl:ER, R. Mental Indices of Sihlings. PIJ"th. Hr.1,ir.1I'. ~5. 1918.

49 ROGEUR, A. }"., DUItI~ING., D. and MACBRIDR! K. The Constancvof

the J.O. and the training of Examiners. ,'ourn. Educ. Ps·ych.

19, ]928.

76 SOUTH A.'RICAN JOURNAL OF SCIENCE.

" Ruaa, H. and COI.LOTON, C. Constancy of the Stanford-Binet I.Q.

as shown by Retests. Journ. Edt/c. Psych. 11, 1921.

51 RUGo, L. S. Retests and the Constancy of the I.Q. Journ. Educ.

Psych. 1', 1925.

52 SHIIN, E. The Intellectual Resemblance of Twins. School and

Sod ely, 11, 1925.

., SIMS V. M. The Inftuence of Blood relationship and Common

·Environment on Measured Intelligence. Journ Educ. Psych.

tt, 1931.

" SCHMITT, M. Der EillftUSS des Milieus u. anderer Faktoren auf daa

Intelligenzalter. Fortschritte dl'.r Psyc1lQloyie u. Ihrer Anwen-

dungen, 5, ]922 .

., SCHUSTER, E. and ELDERTON, E. M. The Inheritance of Ability,

1907 .

•• SCHUSTER, E. and EJ.DERTON, E. M. On the Inheritance of Physical

Characters. Biometrika,S, 1906-7 •

., SO\l'MER, R. Goethe im Lichte der Vererbungslehre. 1908 .

•• SOlI MER, R. Geistige Veranlagung u. Verebung (Aus Natur- und

Geisteswelt). 1919.

•• STERN, W. De Intelligenz tlE'r Kindel' \I. JugE'ndlichen. 1920.

•• TERMAN, L. M. The Intelligence of School Children. 1921.

61 TERMAN, L. M. and OTHERS. Discllssion of the 27th Yearbook .

.!ourn. IMuc. Psych. 1928.

., THORNDIKE, E. L. Measurement of Twins. Archives 01 Philos ••

Psych. and Sci.p.nti/ic Method.~. 1, 1905.

'.1 'J'HURN\\,M.n, R. Vater u. 80hne im Unh'ersitat~studium Preussens.

A.1·chi1,. I. lfm.<w 11. Gcse1/srhalt.5biolo(Jie, t, 1905.

.. 'VEINTROR, J. and 'VEINTROR, R. The Inftuence of Environment on

Reproduced by Sabinet Gateway under licence granted by the Publisher (dated 2010).

Mentl\l. Ability as shown by Binet-Simon Tests. JOUrTl. Educ.

PS'Ych. 3, ]912.

" WIT.COCKS, R. 'V. On the Correlation of Intelligence Scores of Sib-

lings. S. At. Journal 01 Science. 28, 881, 1929.

tG 'VINGPIKLD, A. H. and SANDIGOLD, P. Twins and Orphans. Journ.

Educ. PS'Ych. 19, 1928 .

• 7 WOODWORTH, R. S. Psychology, 1930.

• 0 YOAKUM, C. S. lind YERKES, R. M. Mental Tests In the American

Army, 1920.

You might also like

- 10 1038@35044558 PDFDocument8 pages10 1038@35044558 PDFJ.J.No ratings yet

- Cap 2 IS EN DIVERSAS POBLACIONESDocument11 pagesCap 2 IS EN DIVERSAS POBLACIONESNeuralbaNo ratings yet

- Plomin, R. & Daniels, D. (1987) - Why Are Children in The Same Family So Different From OneDocument20 pagesPlomin, R. & Daniels, D. (1987) - Why Are Children in The Same Family So Different From OneAnahi CopatiNo ratings yet

- Innate and AcquireDocument15 pagesInnate and AcquireSissiNo ratings yet

- Cognitive StimulationDocument11 pagesCognitive StimulationAdriana LeãoNo ratings yet

- Harlow59 PDFDocument12 pagesHarlow59 PDFJuan Carcausto100% (1)

- Expectation (And Attention) in Visual Cognition: Christopher Summerfield and Tobias EgnerDocument7 pagesExpectation (And Attention) in Visual Cognition: Christopher Summerfield and Tobias Egnerju juNo ratings yet

- 12 - Gelfo2019CFDocument9 pages12 - Gelfo2019CFFrancisco Ahumada MéndezNo ratings yet

- Neural Reorganization Following Sensory Loss The Opportunity of ChangeDocument20 pagesNeural Reorganization Following Sensory Loss The Opportunity of ChangeAngelesNo ratings yet

- The Recording Methods.: Form (Chapter 9)Document2 pagesThe Recording Methods.: Form (Chapter 9)Juan David Rojas GomezNo ratings yet

- Brain Size Evolution: How Fish Pay For Being Smart: Dispatch R63Document3 pagesBrain Size Evolution: How Fish Pay For Being Smart: Dispatch R63Nika AbashidzeNo ratings yet

- Nature vs. NurtureDocument19 pagesNature vs. NurtureAshleighNo ratings yet

- Biol Embed Epi RR21Document9 pagesBiol Embed Epi RR21Melek YaverNo ratings yet

- Adolescence What Do Transmission, Transition, and Translation Have To Do With ItDocument23 pagesAdolescence What Do Transmission, Transition, and Translation Have To Do With ItAsish DasNo ratings yet

- Summary of Modern Perspectives in Development PDFDocument2 pagesSummary of Modern Perspectives in Development PDFDiana Lyka ManaloNo ratings yet

- Beyond The Grand Illusion What Change BlindnessDocument16 pagesBeyond The Grand Illusion What Change Blindnesscino kayaNo ratings yet

- Solloway Journalof Applied Measurement ArticleDocument15 pagesSolloway Journalof Applied Measurement ArticleMonserrat LoyoNo ratings yet

- Develop Med Child Neuro - 2017 - Kolb - Principles of Plasticity in The Developing BrainDocument6 pagesDevelop Med Child Neuro - 2017 - Kolb - Principles of Plasticity in The Developing BrainrenatoNo ratings yet

- ED188074Document10 pagesED188074Joanna LeeNo ratings yet

- Settling The Debate On Birth Order and PersonalityDocument2 pagesSettling The Debate On Birth Order and PersonalityAimanNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Quantitative Research: Activity 1A: True or FalseDocument5 pagesIntroduction To Quantitative Research: Activity 1A: True or FalseGwenn ColantroNo ratings yet

- Roberts Retirementinfluencecognitive 2011Document7 pagesRoberts Retirementinfluencecognitive 2011zh.suihan02No ratings yet

- Society For Research in Child Development, Wiley Child DevelopmentDocument9 pagesSociety For Research in Child Development, Wiley Child DevelopmentVíctor FuentesNo ratings yet

- Environmental Education: A Natural Way To Nurture Children's Development and LearningDocument5 pagesEnvironmental Education: A Natural Way To Nurture Children's Development and LearningNour ShaffouniNo ratings yet

- Fnhum 10 00694Document14 pagesFnhum 10 00694Nelson Alex Lavandero PeñaNo ratings yet

- Genetic HypingDocument4 pagesGenetic Hypingcaetano.infoNo ratings yet

- Comment: What Is Environmental Research?Document1 pageComment: What Is Environmental Research?Terrence GwararembitiNo ratings yet

- Developmental Science - 2022 - VogelsangDocument9 pagesDevelopmental Science - 2022 - VogelsangLihui TanNo ratings yet

- Hand Outs Module 4 2Document10 pagesHand Outs Module 4 2Diane Hamor100% (1)

- Skinner, B. F. (1935) - The Generic Nature of The Concepts of Stimulus and Response PDFDocument28 pagesSkinner, B. F. (1935) - The Generic Nature of The Concepts of Stimulus and Response PDFJota S. FernandesNo ratings yet

- Nature Nurture and Human Behavior An Endless Debate 2375 4494 1000e107Document5 pagesNature Nurture and Human Behavior An Endless Debate 2375 4494 1000e107Rohit SharmaNo ratings yet

- Memory - Bruck Ceci (1999)Document22 pagesMemory - Bruck Ceci (1999)time masterNo ratings yet

- 2017 Antinori MixedBR-and-PersonalityDocument8 pages2017 Antinori MixedBR-and-Personalitymary grace bialenNo ratings yet

- The Consuming Instinct What Darwinian Consumption Reveals About Human NatureDocument16 pagesThe Consuming Instinct What Darwinian Consumption Reveals About Human Naturechung yvonneNo ratings yet

- To Cite This Article: (1888) A Manual of Zoology For The Use of StudentsDocument5 pagesTo Cite This Article: (1888) A Manual of Zoology For The Use of StudentsRicardinho1987No ratings yet

- (Macaulay, M. & Macmillan, M.) The Concept of Mental Age and MaturationDocument4 pages(Macaulay, M. & Macmillan, M.) The Concept of Mental Age and MaturationLuis GómezNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Analysis of Biophilic Approach in Building DesignDocument6 pagesA Comparative Analysis of Biophilic Approach in Building DesignIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Annurev Psych 50 1 419Document22 pagesAnnurev Psych 50 1 419Maye VásquezNo ratings yet

- A Balancing Act: Physical Balance, Through Arousal, in Uences Size PerceptionDocument28 pagesA Balancing Act: Physical Balance, Through Arousal, in Uences Size Perceptionعلي عباسNo ratings yet

- Witmer and Singer - Measuring Presence in Virtual1998 PDFDocument17 pagesWitmer and Singer - Measuring Presence in Virtual1998 PDFKarl MickeiNo ratings yet

- Roger Walsh M.D., Ph.D. (Auth.) - Towards An Ecology of Brain-Springer Netherlands (1981) PDFDocument194 pagesRoger Walsh M.D., Ph.D. (Auth.) - Towards An Ecology of Brain-Springer Netherlands (1981) PDFLeo RuilovaNo ratings yet

- Ethics Report Group 4Document23 pagesEthics Report Group 4Papa, JeriemarNo ratings yet

- Gallup Contagious Yawning Systematic ReviewDocument13 pagesGallup Contagious Yawning Systematic ReviewShaelynNo ratings yet

- Extended Cognition in PlantsDocument6 pagesExtended Cognition in PlantsAlan Rodrigo Montes de Oca GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Nature Vs NurtureDocument8 pagesNature Vs NurtureBarbaraNo ratings yet

- Adult Age Differences inDocument6 pagesAdult Age Differences inNelson BrunoNo ratings yet

- Inductive Reasoning: Brett K. Hayes, Evan Heit and Haruka SwendsenDocument15 pagesInductive Reasoning: Brett K. Hayes, Evan Heit and Haruka SwendsenNicolás GómezNo ratings yet

- Module 4: Research in Child and Adolescent DevelopmentDocument10 pagesModule 4: Research in Child and Adolescent DevelopmentRachel Joy SaldoNo ratings yet

- Module 2 Envi SciDocument8 pagesModule 2 Envi SciJu X MilNo ratings yet

- EpigeneticsDocument3 pagesEpigeneticsandrea-fioreNo ratings yet

- The Review of Economic Studies, LTD.: Oxford University PressDocument33 pagesThe Review of Economic Studies, LTD.: Oxford University PressghcghNo ratings yet

- Breathing and EmotionDocument25 pagesBreathing and EmotionsebaNo ratings yet

- A Case of Impared Knowledge For Fruit and VegetablesDocument30 pagesA Case of Impared Knowledge For Fruit and VegetablesboivinNo ratings yet

- Development of AdaptationsDocument9 pagesDevelopment of AdaptationssgjrstujtiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Nature, Nurture, and Human Diversity, Myers 8e PsychologyDocument24 pagesChapter 3 Nature, Nurture, and Human Diversity, Myers 8e Psychologymrchubs100% (11)

- Natural BeautyDocument9 pagesNatural BeautyKarina LanderosNo ratings yet

- Psychological Science and The Law - (5. Eyewitness Memory)Document26 pagesPsychological Science and The Law - (5. Eyewitness Memory)Alba ParísNo ratings yet

- Nature as She Is: A Science and Philosophy for the 21st CenturyFrom EverandNature as She Is: A Science and Philosophy for the 21st CenturyNo ratings yet

- Adenoids and Diseased Tonsils Their Effect on General IntelligenceFrom EverandAdenoids and Diseased Tonsils Their Effect on General IntelligenceNo ratings yet

- Do We Have Free Will? - Based On The Teachings Of Dr. Andrew Huberman: Exploring The Boundaries Of Human ChoiceFrom EverandDo We Have Free Will? - Based On The Teachings Of Dr. Andrew Huberman: Exploring The Boundaries Of Human ChoiceNo ratings yet

- Obligatoire: Connectez-Vous Pour ContinuerDocument2 pagesObligatoire: Connectez-Vous Pour ContinuerRaja Shekhar ChinnaNo ratings yet

- National Anthems of Selected Countries: Country: United States of America Country: CanadaDocument6 pagesNational Anthems of Selected Countries: Country: United States of America Country: CanadaHappyNo ratings yet

- Progressive Muscle RelaxationDocument4 pagesProgressive Muscle RelaxationEstéphany Rodrigues ZanonatoNo ratings yet

- Design of Combinational Circuit For Code ConversionDocument5 pagesDesign of Combinational Circuit For Code ConversionMani BharathiNo ratings yet

- Cloud Comp PPT 1Document12 pagesCloud Comp PPT 1Kanishk MehtaNo ratings yet

- Government College of Nursing Jodhpur: Practice Teaching On-Probability Sampling TechniqueDocument11 pagesGovernment College of Nursing Jodhpur: Practice Teaching On-Probability Sampling TechniquepriyankaNo ratings yet

- JIS G 3141: Cold-Reduced Carbon Steel Sheet and StripDocument6 pagesJIS G 3141: Cold-Reduced Carbon Steel Sheet and StripHari0% (2)

- 16783Document51 pages16783uddinnadeemNo ratings yet

- SSP 237 d1Document32 pagesSSP 237 d1leullNo ratings yet

- DeliciousDoughnuts Eguide PDFDocument35 pagesDeliciousDoughnuts Eguide PDFSofi Cherny83% (6)

- Fds-Ofite Edta 0,1MDocument7 pagesFds-Ofite Edta 0,1MVeinte Años Sin VosNo ratings yet

- 40 People vs. Rafanan, Jr.Document10 pages40 People vs. Rafanan, Jr.Simeon TutaanNo ratings yet

- UltimateBeginnerHandbookPigeonRacing PDFDocument21 pagesUltimateBeginnerHandbookPigeonRacing PDFMartinPalmNo ratings yet

- Activity On Noli Me TangereDocument5 pagesActivity On Noli Me TangereKKKNo ratings yet

- Umwd 06516 XD PDFDocument3 pagesUmwd 06516 XD PDFceca89No ratings yet

- PC Model Answer Paper Winter 2016Document27 pagesPC Model Answer Paper Winter 2016Deepak VermaNo ratings yet

- Lecture2 GranulopoiesisDocument9 pagesLecture2 GranulopoiesisAfifa Prima GittaNo ratings yet

- 1 in 8.5 60KG PSC Sleepers TurnoutDocument9 pages1 in 8.5 60KG PSC Sleepers Turnoutrailway maintenanceNo ratings yet

- Nadee 3Document1 pageNadee 3api-595436597No ratings yet

- Sample - SOFTWARE REQUIREMENT SPECIFICATIONDocument20 pagesSample - SOFTWARE REQUIREMENT SPECIFICATIONMandula AbeyrathnaNo ratings yet

- Application Form InnofundDocument13 pagesApplication Form InnofundharavinthanNo ratings yet

- Fire Protection in BuildingsDocument2 pagesFire Protection in BuildingsJames Carl AriesNo ratings yet

- Sem4 Complete FileDocument42 pagesSem4 Complete Fileghufra baqiNo ratings yet

- Deep Hole Drilling Tools: BotekDocument32 pagesDeep Hole Drilling Tools: BotekDANIEL MANRIQUEZ FAVILANo ratings yet

- 2022 WR Extended VersionDocument71 pages2022 WR Extended Versionpavankawade63No ratings yet

- Business Plan in BDDocument48 pagesBusiness Plan in BDNasir Hossen100% (1)

- Radon-222 Exhalation From Danish Building Material PDFDocument63 pagesRadon-222 Exhalation From Danish Building Material PDFdanpalaciosNo ratings yet

- Test 51Document7 pagesTest 51Nguyễn Hiền Giang AnhNo ratings yet

- Assistant Cook Learner Manual EnglishDocument152 pagesAssistant Cook Learner Manual EnglishSang Putu Arsana67% (3)

- Configuring BGP On Cisco Routers Lab Guide 3.2Document106 pagesConfiguring BGP On Cisco Routers Lab Guide 3.2skuzurov67% (3)