Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Wright 2015

Wright 2015

Uploaded by

Lia PuspitasariCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Wright 2015

Wright 2015

Uploaded by

Lia PuspitasariCopyright:

Available Formats

Page 1 of 6 Review Article

The impact of solar ultraviolet radiation on human

health in sub-Saharan Africa

Authors: Photoprotection messages and ‘SunSmart’ programmes exist mainly to prevent skin cancers

Caradee Y. Wright1 and, more recently, to encourage adequate personal sun exposure to elicit a vitamin D

Mary Norval2

Beverley Summers3 response for healthy bone and immune systems. Several developed countries maintain

Lester Davids4 intensive research networks and monitor solar UV radiation to support awareness campaigns

Gerrie Coetzee5 and intervention development. The situation is different in sub-Saharan Africa. Adequate

Matthew O. Oriowo6

empirical evidence of the impact of solar UV radiation on human health, even for melanomas

Affiliations: and cataracts, is lacking, and is overshadowed by other factors such as communicable

1

Modelling and Environmental diseases, especially HIV, AIDS and tuberculosis. In addition, the established photoprotection

Health Research Group,

Council for Scientific messages used in developed countries have been adopted and implemented in a limited

and Industrial Research, number of sub-Saharan countries but with minimal understanding of local conditions and

Natural Resources and the behaviours. In this review, we consider the current evidence for sun-related effects on human

Environment, Pretoria,

South Africa health in sub-Saharan Africa, summarise published research and identify key issues. Data

on the prevalence of human diseases affected by solar UV radiation in all subpopulations

2

Biomedical Sciences, are not generally available, financial support is insufficient and the infrastructure to address

University of Edinburgh

Medical School, Edinburgh, these and other related topics is inadequate. Despite these limitations, considerable progress

Scotland may be made regarding the management of solar UV radiation related health outcomes in

sub-Saharan Africa, provided researchers collaborate and resources are allocated appropriately.

3

Department of Pharmacy

/ Photobiology Laboratory,

University of Limpopo,

Polokwane, South Africa Introduction

4

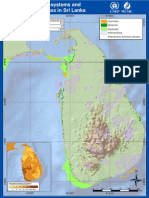

Department of Human Sub-Saharan Africa consists of 43 countries south of the Sahara (Figure 1). This area spans

Biology, University of Cape latitudes 13°N to 33°S with an average annual daytime temperature of 21 °C. The UV Index is

Town Medical School, Cape often higher than 10 (extreme) and rarely drops below 7, except at high altitudes and towards the

Town, South Africa

tip of South Africa in the winter months (June, July and August). The land varies from equatorial

5

South African Weather rainforest to dry woodland, savannah, grassland and mountain grassland.

Services, Pretoria,

South Africa The major beneficial outcome of solar ultraviolet radiation (UVR) exposure on human health lies

in the endogenous production of vitamin D, while adverse outcomes of excess exposure include

6

Department of Optometry,

skin cancers and eye diseases.1 Extensive research and public health interventions relating

Faculty of Health Sciences,

University of Limpopo, to the consequences of solar UVR on human health have been carried out in many developed

Polokwane, South Africa countries; however, the same is not true for sub-Saharan Africa. Limited information suggests

health and exposure risks do exist in this area of the world, although accessing published and

Correspondence to: verified data is a challenge, because most sub-Saharan countries do not have operational health

Caradee Wright

information systems or ground-based networks to monitor solar UVR. The aim of this review is

Email: to broaden the understanding of the effects of solar UVR on human health in sub-Saharan Africa

cwright@csir.co.za by considering an update of relevant health outcomes and by documenting public perceptions

and interventions.

Postal address:

PO Box 395, Pretoria 0001,

South Africa Search strategy

Dates A systematic approach was used to identify key published resources of substance and

Received: 24 Apr. 2012 appropriate scientific merit. Databases searched were African Journals Online, SABINET,

Accepted: 11 June 2012 Academic Search Premier, Pubmed, SciELO, Medline, JSTOR, Web of Science and Scopus.

Published: 26 Oct. 2012 Keywords entered were “solar UV radiation” AND health AND [country]; “sun exposure” AND

How to cite this article: health AND [country]; sunburn AND [country]; “skin cancer” AND [country]; albinism AND

Wright CY, Norval M, “sun exposure” AND [country]; [range of sun-related eye diseases] AND “sun exposure” AND

Summers B, Davids L, [country]; “sun protection” AND [country]; “sun behaviour” AND [country]; and “sunsmart

Coetzee G, Oriowo MO. The awareness programme” AND [country]. Reference lists of collected articles including reports of

impact of solar ultraviolet

radiation on human health the World Health Organization (WHO) were examined. Using the same keywords, Google was

in sub-Saharan Africa. S searched for grey literature, a particularly important source in the African context. The websites

Afr J Sci. 2012;108(11/12), of national departments of health and cancer associations were investigated for information on

Art. #1245, 6 pages. http:// ‘SunSmart’ programmes and sun-related health statistics.

dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajs.

v108i11/12.1245 Copyright: © 2012. The Authors. Licensee: AOSIS OpenJournals. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License.

http://www.sajs.co.za S Afr J Sci 2012; 108(11/12)

Page 2 of 6 Review Article

10°W 0° 10°E 20°E 30°E 40°E 50°E

40°N 40°N

30°N 30°N

20°N 20°N

10°N 10°N

0° 0°

10°S 10°S

20°S 20°S

N

W E

30°S 30°S

S

0 500 1000 2000

km

40°S 40°S

10°W 0° 10°E 20°E 30°E 40°E 50°E

FIGURE 1: The countries of sub-Saharan Africa.

Results pigmented people, in whom SCCs are the most frequent.

In dark-skinned individuals, SCCs occur most often on

Skin cancers the lower limbs (developing from antecedent lesions such

Sun exposure is the major environmental risk factor for as ulcerations, burns and scars), followed by the head and

melanoma and for the non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSCs), neck. In fair-skinned people, SCCs are found almost entirely

on the most sun-exposed areas of the body, such as the face

basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma

and ears. Unlike the situation in individuals with fair skin,

(SCC). The lifetime risk of these tumours is low in those

the majority of melanomas in black skin occur on a lower

with black skin and highest in those with fair skin, estimated

extremity, particularly on the sole of the foot, a body site with

at a difference of up to 60-fold. There are other major little pigmentation.

differences depending on skin colour.2 While BCCs represent

about 80% of cutaneous tumours in fair-skinned people, The occurrence of NMSCs in sub-Saharan Africa is rarely

they are the least common of the skin tumours in deeply monitored. However, the UVR-attributable disease burden

http://www.sajs.co.za S Afr J Sci 2012; 108(11/12)

Page 3 of 6 Review Article

caused by SCCs and BCCs for some of the countries in this Oculocutaneous albinism

region was calculated for the year 2000 using three levels

Oculocutaneous albinism (OCA) is a genetically

of skin pigmentation, models for global assessment and

inherited, autosomal recessive condition characterised by

country-specific population-weighted average daily ambient

hypopigmentation of the skin, hair and eyes as a result of

UVR.3,4 Using actual results, the annual incidence of SCC in

a lack of, or reduced, melanin. There are many people

Black individuals was estimated as 1 in 100 000 in a township

living with OCA in sub-Saharan Africa; estimates indicate a

near Soweto, Johannesburg in 1966–1975,5 whereas the age-

prevalence of 1 in 4728 in Zimbabwe, 1 in 3900 in South Africa

standardised annual incidence of BCC in the Netherlands is

and as high as 1 in 1000 in the Tonga tribe in Zimbabwe.13,14

currently more than 140 in 100 000. A study in Kano, Nigeria

Individuals with OCA are at increased risk from the adverse

revealed that 6.3% of all cancers in female individuals and effects of sun exposure, such as extreme sun sensitivity

9.9% in male individuals were NMSCs in 1995–2004.6 One and photophobia. SCCs of the neck and head are the most

recent report based on rural hospitals in Kenya found common cutaneous tumours seen in African patients with

that 44% of all cutaneous malignancies were SCCs and 7% OCA,15 with melanomas occurring rarely.14

were BCCs.7

For melanoma, which accounts for more than 80% of skin

Ophthalmohelioses

cancer deaths, there are also few figures available regarding There is a range of eye diseases associated with sunlight

incidence and prevalence for sub-Saharan Africa, although, exposure – ophthalmohelioses. These diseases include

as for the NMSCs, the UV-attributable disease burden from photoconjunctivitis, photokeratitis and activation of

this tumour was calculated as approximately 5100 deaths for ocular herpes simplex virus following acute exposure to

the year 2000 in this area of the world.4 For South Africa, in solar UVR, and NMSCs of the lid and conjunctiva, ocular

2001 – one of the last years for which statistics are currently melanoma, pinguecula (local degeneration of conjunctiva),

available – the National Cancer Registry recorded an age- pterygium (inflammation, proliferation and invasive growth

standardised incidence rate per 100 000 for melanoma of 1.1 on conjunctiva and cornea), climatic droplet keratopathy

for Black males, 1.5 for Black females, 22.5 for White males (epithelial degeneration), age-related cataracts and possibly

and 17.4 for White females.8 The incidence has risen since age-related macular degeneration following chronic

then and the South African Cape region was estimated in exposure to solar UVR.

2009 to have the highest incidence of melanoma in the world

Few data are available for sub-Saharan Africa that estimate the

at 69 new cases per 100 000 White individuals9 (Australia has

scale of health problems caused by these ophthalmohelioses,

65 per 100 000).

although it is recognised that this area has the highest

regional burden of blindness at 20% of the world’s blindness

Accurate figures on the prevalence of skin cancers in all

and only 11% of the world’s population.16 Indeed, 1% of

subpopulations in sub-Saharan Africa are required, especially

Africans are blind.17 Cataracts account for approximately

to record any changes in incidence. Such data are needed to

50% of the cases of blindness worldwide. The evidence to

inform the public regarding photoprotection and to improve

link cataract development with sun exposure is strongest for

clinical awareness.

cortical cataracts, the form found in about 33% of subjects

with cataracts in one survey based in rural Tanzania.18 In the

Melasma first population-based study in an African setting (Nigeria),

it was reported that there were 5000 per million population

Melasma is an uneven hyperpigmentation which appears

with functional low vision and 340 per million blind.19 One-

as dark, macular, pigmented patches on the face.10 The

quarter of the functional low vision cases were as a result of

cause of melasma is complex – genetic, hormonal, therapy

corneal opacity and about 3% were as a result of pterygium.

and lifestyle-related contributions are implicated, as is sun

The prevalence of functional low vision was highest in the

exposure. For example, 51% of patients reported sun exposure

northern part of Nigeria, which is drier and sunnier than

as a triggering factor and 84% reported sun exposure as an

the south. Earlier studies in South Africa showed an annual

aggravating factor in a study based in Tunisia, with a high

incidence of cataract blindness of 0.14% with a prevalence

lifetime sun exposure increasing the risk of severe melasma

of 0.6% in a rural population in KwaZulu-Natal,20 and a

threefold.11 Melasma represents a significant problem in sub-

prevalence of 0.3% in rural northern Transvaal.21

Saharan Africa, primarily because of its impact on quality of

life. It is suggested to have a significant psycho-emotional Figures for the incidence and prevalence of corneal and

effect on women.12 While different scales, including the other external eye diseases in sub-Saharan Africa are not

Melasma Quality of Life scale, have been devised, these have generally available for recent years, although such disorders

not been tailored effectively for the cultural needs of multi- are recognised to be very common. For example, corneal

ethnic subpopulations. diseases, the majority being pterygium and climatic droplet

keratopathy, were found in more than 20% of a mixed race

Few statistics are available for sub-Saharan Africa regarding community in the north-western Cape (South Africa),22 and

the prevalence of other skin disorders induced by either pterygium represented 9% of all new cases at an eye clinic

acute sun exposure, such as sunburn, or by chronic sun in Ibadan (Nigeria)23 and 8% of ocular problems in adults

exposure, such as photoageing and actinic keratoses, the aged 18–49 in rural Nigeria, most of which occurred in

latter recognised as premalignant lesions. outdoor workers.24

http://www.sajs.co.za S Afr J Sci 2012; 108(11/12)

Page 4 of 6 Review Article

Concern has been expressed recently that sub-Saharan UVR, fair-skinned people exhibit more DNA damage,35

Africa is not on track to achieve the main goal of ‘VISION a higher production of immune mediators and a higher

2020: The Right to Sight’ – to eliminate avoidable blindness degree of immunosuppression36 than those with darker

by 2020.25 This imminent failure has been attributed to the skins. This difference is likely to contribute to the increased

lack of eye care teams, staff development, infrastructure and susceptibility of individuals with fair skin to develop

community programmes.25 In this context, it is disappointing skin cancers compared with individuals with more

to note that the national target for cataract surgery in South pigmented skin.

Africa was downgraded in 2010 from 2000 to 1500 per million

population, when at least 2000 per million per year is It is unclear whether UV-induced immunosuppression can

required to eliminate cataract blindness.26 Guidance for the affect the course of human infectious diseases, apart from

general public about protecting the eye by wearing hats with triggering the reactivation from latency of herpes simplex

wide brims or sunglasses that meet an appropriate standard virus. Some human infections exhibit a strong seasonal

for solar UVR protection would be very helpful in reducing incidence. For example, influenza is highly seasonal in

the risk of ophthalmohelioses.

southern Africa with the peak incidence occurring in the

drier cooler winter months: the seasonality becomes less

Immunosuppression and effects on pronounced with closeness to the equator.37 This pattern is

diseases also seen in other parts of the world, and has been attributed

UV-induced downregulation of immunity to a variety of to lower vitamin D levels (and thus less effective innate

antigens has been demonstrated in humans. The pathways immunity) in the winter compared with the summer in

involved are complex,27 and may involve vitamin D which countries outside the tropics. Tuberculosis presents a major

has many immunoregulatory properties.28 The majority public health issue in sub-Saharan Africa with Nigeria having

of vitamin D in most people is produced as a result of sun the fourth largest tuberculosis burden in the world and South

exposure. The vitamin D status of almost all populations in Africa the fifth largest. Many of the new cases of tuberculosis

sub-Saharan Africa is unknown but, from the incomplete data are co-infections with HIV; currently sub-Saharan Africa

available, is lower in South Africa compared with the tropical accounts for 79% of the worldwide HIV–tuberculosis burden.

African countries.29 However, even near the equator, there From a survey of studies conducted in 11 countries or regions

can be a high rate of vitamin D deficiency, as demonstrated around the world (including South Africa), a seasonal pattern

in adults in Ethiopia (10°N)30 and Guinea-Bissau (12°N).31 of tuberculosis is indicated with a peak in the spring and

Nutritional rickets remains prevalent in some tropical summer months.38 This pattern has been explained by low

countries despite good sunshine exposure, although this may vitamin D levels in the winter leading to less effective control

be as a result of a low calcium intake rather than a deficiency of microbial growth. Hypovitaminosis D is highly prevalent

in vitamin D.32 in tuberculosis patients and is associated with an increased

risk of disease progression, although it is not known if the

From many studies covering a variety of approaches, it low level is a symptom or is causal.31 Recent research has

can be concluded that UVR and/or vitamin D have the considered whether vitamin D prevents reactivation of

potential to protect against some inflammatory diseases tuberculosis.39 With regard to HIV, while some observations

and autoimmune diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, while support a role for UVR in altering the interaction of the

decreasing the immune surveillance against skin tumours virus with the host, clinical and epidemiological reports

and infectious diseases. Each of these categories is discussed

have not demonstrated that exposure to sunlight changes

briefly below.

the course of the disease.40 Many HIV-infected people are

vitamin D deficient but the impact of this deficiency on

In the context of diseases in sub-Saharan Africa, the light-

disease progression is unknown and should be investigated.

sensitive dermatoses (e.g. polymorphic light eruption where

there is a lack of immunosuppression following sun exposure

Vaccination represents a major public health strategy in sub-

with development of an allergic response) do not constitute

Saharan Africa in attempts to control common infections,

a major health problem as they are much less common in

particularly in childhood. The potential of UVR to decrease

people with pigmented skin and occur rarely in regions near

the equator.33 Similarly, multiple sclerosis is uncommon in the efficacy of vaccination by downregulating immunity has

the indigenous Black, Coloured or Indian people of Africa. not been rigorously assessed for human vaccines although

In southern Africa, there is a relatively high prevalence of there are reports indicating that a less effective immune

multiple sclerosis in White migrants from Europe with a response is induced if the vaccine is administered in the

lower prevalence in White African-born people, possibly as a summer compared with the winter, and in tropical compared

result of the protective effect of early exposure to high levels with temperate regions.41 Perhaps of most relevance in the

of solar UVR.34 context of sub-Saharan Africa is finding that the protection

against tuberculosis following vaccination correlates

UVR not only causes mutations but also downregulates positively with distance from the equator.42 More severe

immunity, an effect which is recognised to be critical in UV-induced immunosuppression nearer to the equator as a

the development of skin tumours. For the same dose of result of the higher sun intensity could account for this result.

http://www.sajs.co.za S Afr J Sci 2012; 108(11/12)

Page 5 of 6 Review Article

Sun-related exposure, protection, care for the management of cataracts and skin cancer. The

non-governmental African Organisation for Research and

perceptions and awareness Training in Cancer promotes cancer control and palliative

The people of sub-Saharan Africa are genetically diverse: care, and several sub-Saharan countries have cancer societies.

migrants from other countries have settled here since the The Cancer Association of South Africa is one of the few

Greeks, Romans and Arabs 3000 years ago, Europeans since with a SunSmart programme. As outlined above, there are

the 1600s and Asians since the 1800s. If this heterogeneity is currently insufficient data to assess the extent of sun-related

added to the range of environments and social conditions in health effects and the relevance of any interventions in sub-

sub-Saharan Africa, it can be anticipated that solar UVR will Saharan Africa.

not have straightforward health outcomes. In addition, the

only country to possess solar UV monitoring instruments in Challenges and opportunities

this region is South Africa, where a four-station network has Several challenges will need to be overcome and

been in operation since the early 1990s. The network aims opportunities created to improve the understanding of the

to provide measured data to the media daily to inform the health impacts of solar UVR and to implement interventions

public regarding times of intense solar irradiation. locally for a sustained improvement in public health. The

WHO INTERSUN programme is one possible mechanism.

Personal sun exposure studies in sub-Saharan Africa are non- For this programme to be effective in sub-Saharan Africa,

existent, inaccessible or sparsely documented. One of the few fundamental research is needed on local disease prevalence

studies, based in Durban (South Africa), emphasised the risk and incidence, exposure patterns (occupational, early life and

of sunburn and NMSC for children and outdoor workers.43 recreational) and sun awareness, especially the lack thereof

Schoolchildren in this city experienced a mean total daily but also how awareness is affected by cultural beliefs and

solar exposure of two Standard Erythemal Doses, with boys practices. The capacity to initiate and manage public health

experiencing greater sun exposure than girls and outdoor information to support such research is required. For example,

physical activity being the most important determinant of a National Cancer Registry has only recently been re-instated

sun exposure. in South Africa. There are additional unknowns such as

any consequence of climate change in sub-Saharan Africa.

Knowledge about sun protection is not widespread in sub- Ground-based monitoring of ambient solar UVR is limited,

Saharan Africa. Sunscreen use and environmental awareness mainly because of financial and personnel restrictions. Little

were investigated in White Cape Town beachgoers; the research has been done on potential interactions of solar

UVR with local diseases, such as HIV, AIDS, malaria and

results showed that only 50% wore sunscreen, although 90%

tuberculosis, and with vaccine responses. Research is also

of respondents cited skin cancer as a potential adverse effect

needed on personal solar UVR exposure and sun protection

of excess sun exposure and a few acknowledged other health

studies on at-risk subpopulations should be conducted. The

effects.44 A survey of students attending four large tertiary

potential of solar UVR to decrease the efficacy of vaccination

institutions in South Africa showed that 82.3% knew that

by immunosuppression also merits investigation.

excessive sunlight may have harmful ocular effects, but only

a quarter reported that they often wore sunglasses outdoors Sun education needs to be tailored for sub-Saharan Africa

and 38.5% recognised that not all spectacles and contact and its multi-ethnic subpopulations. Sun protection and

lenses were protective.45 health intervention programmes targeted at children

with OCA have proved relatively successful48 and similar

Sun protection is of special importance for individuals targeted interventions for groups at particular risk may be an

with OCA to prevent skin damage and thus lessen the risk appropriate way forward. A multidisciplinary approach for

of skin cancer. Most OCA cases present late in the tumour research and intervention programmes is essential, especially

process and patients do not complete treatment because of given the limited resources, capacity and infrastructure, and

a lack of funds or for cultural reasons. Education regarding the high burden of communicable diseases in sub-Saharan

protective clothing, sunscreens, indoor occupations and Africa. Seeking health co-benefits that arise from dovetailing

early treatment of skin lesions would be beneficial. An research with society and government priorities could be

investigation in Tanzania of albinos’ understanding of skin the best strategy to manage the health consequences of solar

cancer risk and attitudes toward sun protection showed that UVR in sub-Saharan Africa.

78% of respondents believed skin cancer was preventable,

63% knew that skin cancer was related to the sun and 77% Acknowledgements

thought sunscreens afforded sun protection.46 Reasons for

The preparation of this manuscript was funded, in part, by

not wearing a hat included fashion, culture and heat. Hat-

a CSIR Parliamentary Grant to C.W. and a South African

wearing among children with OCA and visual impairment

Medical Research Council Career Award to L.D.

in northern South Africa was high (although the brim width

was not always sufficient) and one-third used sunscreens.47

Competing interests

Few sub-Saharan countries have active, sun-related We declare that we have no financial or personal relationships

awareness and disease prevention campaigns although which may have inappropriately influenced us in writing

some work has been carried out to improve primary health this paper.

http://www.sajs.co.za S Afr J Sci 2012; 108(11/12)

Page 6 of 6 Review Article

Authors' contributions 22. Hill JC. The prevalence of corneal disease in the coloured community of a

Karoo town. S Afr Med J. 1985;67:723–727.

C.W. was the project leader, conceptualised the article content 23. Ashaye AO. Pterygium in Ibadan. West Afr J Med. 1991;10:232–243.

and compiled the sun protection and albinism sections. M.N. 24. Nwosu SN. Ocular problems of young adults in rural Nigeria. Int Ophthalmol.

1998;22:259–263. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1006338013075

compiled the immune system section, B.S. compiled the 25. Lewallen S, Kello AB. The need for management capacity to achieve

melasma section, L.D. compiled the skin cancer section and VISION 2020 in sub-Saharan Africa. PloS Med. 2009;6:e1000184. http://

dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000184

M.O.O. compiled the ophthalmohelioses section. C.W., M.N., 26. Lecuona K, Cook C. South Africa’s cataract surgery rates: Why are we not

B.S., L.D. and M.O.O. wrote the manuscript. G.C. gave input meeting our targets? S Afr Med J. 2011;101:510–512.

to the challenges and opportunities section. 27. Schwarz T, Schwarz A. Molecular mechanisms of ultraviolet radiation-

induced immunosuppression. Eur J Cell Biol. 2011;90:560–564. http://

dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcb.2010.09.011

References 28. Schwalfenberg GK. A review of the critical role of vitamin D in the

functioning of the immune system and the clinical implications of

vitamin D deficiency. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2011;55:96–108. http://dx.doi.

1. Norval M, Lucas RM, Cullen AP, et al. The human health effects of ozone org/10.1002/mnfr.201000174

depletion and interactions with climate change. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 29. Prentice A. Vitamin D deficiency: A global perspective. Nutr Rev.

2011;10:199–225. http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/c0pp90044c 2008;66:s153–164. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00100.x

2. Gloster HM, Neal K. Skin cancer in skin of colour. J Am Acad Dermatol. 30. Feleke Y, Abdulkadir J, Mshana RM, et al. Low levels of serum calcidiol

2006;55:741–760. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2005.08.063 in an African population compared to a North European population. Eur

3. Lucas RM. Solar ultraviolet radiation. Assessing the environmental burden J Endrocrinol. 1999;141:358–360. http://dx.doi.org/10.1530/eje.0.1410358

of disease at national and local levels. Environmental Burden of Disease 31. Wejse C, Olesen R, Rabna P, et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D in a West

Series number 13. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. African population of tuberculosis patients and unmatched healthy

4. Lucas RM. Solar ultraviolet radiation. Assessing the environmental burden controls. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:1376–1383.

of disease at national and local levels. Environmental Burden of Disease 32. Thacher TD, Fischer PR, Pettifor JM, et al. A comparison of calcium, vitamin

Series number 17. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. D, or both for nutritional rickets in Nigerian children. N Engl J Med.

5. Isaacson C. Cancer of the skin in urban blacks of South Africa. Br J 1999;341:563–568. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199908193410803

Dermatol. 1979;100:347–350. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.1979. 33. Honigsmann H. Polymorphous light eruption. Photodermatol

tb06210.x Photoimmunol Photomed. 2008;24;155–161. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/

6. Mohammed AZ, Edino ST, Ochicha O, Gwarzo AK, Samila AA. Cancer in j.1600-0781.2008.00343.x

Nigeria: A 10-year analysis of the Kano registry. Niger J Med. 2008;17:280– 34. Dean G, Bhigjee AI, Bill PL, et al. Multiple sclerosis in black South Africans

284. http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/njm.v17i3.37396 and Zimbabweans. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57:1064–1069.

7. Nthumba PM, Cavadas PC, Landin L. Primary cutaneous malignancies http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.57.9.1064

in sub-Saharan Africa. Ann Plast Surg. 2011;66:313–320. http://dx.doi. 35. Tadokoro T, Kobayashi N, Zmudzka BZ, et al. UV-induced DNA damage

org/10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181e7db9a and melanin content in human skin differing in racial/ethnic origin.

8. Mqoqi N, Kellet P, Sitas F, Jula M. Incidence of histologically diagnosed FASEB J. 2003;17:1177–1179.

cancer in South Africa, 1998–1999. Johannesburg: National Cancer Registry 36. Kelly DA, Young AR, McGregor JM, Seed PT, Potten CS, Walker SL.

of South Africa, National Health Laboratory Service; 2004. Sensitivity to sunburn is associated with susceptibility to ultraviolet

9. Davids LM, Kleemann B. Combating melanoma: The use of photodynamic radiation-induced suppression of cutaneous immunity. J Exp Med.

therapy as a novel, adjuvant therapeutic tool. Cancer Treat Rev. 2000;191:561–566. http://dx.doi.org/10.1084/jem.191.3.561

2011;37(6):465–475. 37. Gessner BD, Shindo N, Briand S. Seasonal influenza epidemiology in sub-

Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:223–235.

10. Victor FC, Gerlber J, Rao B. Melasma: A review. J Cutan Med Surg. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70008-1

2004;8:97–102. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10227-004-0158-9

38. Fares A. Seasonality of tuberculosis. J Glob Infect Dis. 2011;3:46–55. http://

11. Guinot C, Cheffai S, Latreille J, et al. Aggravating factors for melasma: A dx.doi.org/10.4103/0974-777X.77296

prospective study in 197 Tunisian patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol.

2010;24:1060–1069. 39. Martineau AR, Nhamoyebonde S, Oni T, et al. Reciprocal seasonal

variation in vitamin D status and tuberculosis notifications in Cape Town,

12. Jobanputra R, Bachmann M. The effect of skin diseases on quality of life South Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sic USA. 2011;108(47):19013–19017. http://

in patients from different social and ethnic groups in Cape Town, South dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1111825108

Africa. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:826–831. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-

4362.2000.00073.x 40. Akaraphanth R, Lim HW. HIV, UV and immunosuppression.

Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 1999;15:28–31. http://dx.doi.

13. Hong ES, Zeeb H, Repacholi MH. Albinism in Africa as a public health org/10.1111/j.1600-0781.1999.tb00049.x

issue. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:212. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-

2458-6-212 41. Norval M, Woods GM. UV-induced immunosuppression and the efficacy

of vaccination. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2011;10:1267–1274. http://dx.doi.

14. Asuquo ME, Otei OO, Omotoso J, Bassey EE. Letter: Skin cancer in albinos org/10.1039/c1pp05105a

at the University of Calabar teaching Hospital, Calabar, Nigeria. Dermatol

Online J. 2010;16:14. 42. Colditz GA, Brewer TF, Berkey CS, et al. Efficacy of BCG vaccine in the

prevention of tuberculosis. JAMA. 1994;271:698–702. http://dx.doi.

15. Yakabu A, Mabogunje OA. Skin cancer in African albinos. Acta Oncologica. org/10.1001/jama.1994.03510330076038

1993;32:621–622. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/02841869309092440

43. Guy CY, Diab RD. A health risk assessment of ultraviolet radiation in

16. Resnikoff S, Pascolini D, Etya’ale D, et al. Global data on visual impairment Durban. S Afr Geographical J. 2002;84:208–213. http://dx.doi.org/10.108

in the year 2002. Bull World Health Org. 2004;82:844–851. 0/03736245.2002.9713772

17. Lewallen S, Courtright P. Blindness in Africa: Present situation and future 44. Von Schirnding Y, Strauss N, Mathee A, Robertson P, Blignaut R.

needs. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:897–903. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ Sunscreen use and environmental awareness among beach-goers in Cape

bjo.85.8.897 Town, South Africa. Public Health Rev. 1991/92;19:209–217.

18. Congdon N, West SK, Buhrmann RR, Kouzis A, Munoz B, Mkocha H. 45. Oduntan OA, Carlson A, Clarke-Farr P, Hansraj R. South African

Prevalence of the different types of age-related cataract in an African university student knowledge of eye protection against sunlight. S Afr

population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:2478–2482. Optom. 2009;68:25–31.

19. Entekuma G, Patel J, Sivasubramaniam S, et al. Prevalence, causes, and 46. McBride SR, Leppard DM. Attitudes and beliefs of an albino population

risk factors for functional low vision in Nigeria: Results from the national towards sun avoidance: Advice and services provided by an outreach

survey of blindness and visual impairment. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. albino clinic in Tanzania. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:629–632. http://dx.doi.

2011;52:6714–6719. http://dx.doi.org/10.1167/iovs.11-7293 org/10.1001/archderm.138.5.629

20. Cook CD, Stulting AA. Prevalence and incidence of blindness due to age- 47. Lund PM, Taylor JS. Lack of adequate sun protection for children with

related cataract in the rural areas of South Africa. S Afr Med J. 1995;85:26– oculocutaneous albinism in South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:225.

27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-8-225

21. Bucher PJ, Ijsselmuiden CB. Prevalence and causes of blindness in the 48. Lund PM, Gaigher R. A health intervention programme for children with

Northern Transvaal. Br J Ophthalmol. 1988;72:721–726. http://dx.doi. albinism at a special school in South Africa. Health Educ Res. 2002;17:365–

org/10.1136/bjo.72.10.721 372. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/her/17.3.365

http://www.sajs.co.za S Afr J Sci 2012; 108(11/12)

You might also like

- AS440S42T FP LT XP - Low-Chassis Tractor 4x2Document14 pagesAS440S42T FP LT XP - Low-Chassis Tractor 4x2Dan RosoiuNo ratings yet

- The Human-Environment Nexus and Vegetation-RainfalDocument11 pagesThe Human-Environment Nexus and Vegetation-Rainfalalina22vsNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id4008109Document9 pagesSSRN Id4008109Chiemeka ChibuezeNo ratings yet

- Experimental Dermatology - 2014 - Ichihashi - The Maximal Cumulative Solar UVB Dose Allowed To Maintain Healthy and YoungDocument4 pagesExperimental Dermatology - 2014 - Ichihashi - The Maximal Cumulative Solar UVB Dose Allowed To Maintain Healthy and YoungMayra Alves SetalaNo ratings yet

- Guan Et Al 2015 Nature GeoscienceDocument6 pagesGuan Et Al 2015 Nature GeoscienceAriadne Cristina De AntonioNo ratings yet

- Applsci 10 06589 1Document14 pagesApplsci 10 06589 1Ashraf RamadanNo ratings yet

- Volume 55Document9 pagesVolume 55Nho TaNo ratings yet

- UV Creates Vitamin D and Skin Cancer - 2009Document6 pagesUV Creates Vitamin D and Skin Cancer - 2009negrumih1683No ratings yet

- Atmosphere 13 01054Document13 pagesAtmosphere 13 01054Édria SousaNo ratings yet

- An Assessment of The Global UV Solar Radiation Under Various Sky Conditions in Maceió-Northeastern BrazilDocument10 pagesAn Assessment of The Global UV Solar Radiation Under Various Sky Conditions in Maceió-Northeastern BrazilAshraf RamadanNo ratings yet

- Ultraviolet Radiation and The Eye - An Epidemiologic StudyDocument52 pagesUltraviolet Radiation and The Eye - An Epidemiologic StudyMaria Gerber RozaNo ratings yet

- NSTP2 G8 Solar StormsDocument6 pagesNSTP2 G8 Solar StormsSAMANTHAALEXA ASAJARNo ratings yet

- Solar Index GuideDocument18 pagesSolar Index GuidecavrisNo ratings yet

- Lifetime La Exposición A La Radiación Ultravioleta Ambiente y El Riesgo para La Extracción de Catarata y Edad Degeneración Macular RelacionadaDocument10 pagesLifetime La Exposición A La Radiación Ultravioleta Ambiente y El Riesgo para La Extracción de Catarata y Edad Degeneración Macular RelacionadaMarco Gámez BegazoNo ratings yet

- (Diaz, 2013) 30Document11 pages(Diaz, 2013) 30Corina Elena CozmaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 4 - RizalDocument10 pagesJurnal 4 - RizalVura guraNo ratings yet

- Always The Sun - The Uniqueness of Sun Exposure in TourismDocument12 pagesAlways The Sun - The Uniqueness of Sun Exposure in TourismMaayan FrancoNo ratings yet

- Đỗ Thị Yến Nhi - 225111214 - A058Document4 pagesĐỗ Thị Yến Nhi - 225111214 - A058nhidty22No ratings yet

- Ijmer 46060106 PDFDocument6 pagesIjmer 46060106 PDFIJMERNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Skin Cancers, Solar Radiation and Ozone DepletionDocument7 pagesThe Relationship Between Skin Cancers, Solar Radiation and Ozone DepletionMBNo ratings yet

- CGH PPT - CCCDocument45 pagesCGH PPT - CCCIan GreyNo ratings yet

- Contribution of UVA Irradiance To The Erythema - 2015 - Journal of PhotochemistrDocument7 pagesContribution of UVA Irradiance To The Erythema - 2015 - Journal of PhotochemistrPericles AlvesNo ratings yet

- Should We Be Advising Our Patients About The Need For Ocular Protection?Document7 pagesShould We Be Advising Our Patients About The Need For Ocular Protection?AnthonyNo ratings yet

- Verkouteren 2017Document14 pagesVerkouteren 2017Nilamsari KurniasihNo ratings yet

- Bataille 2004Document7 pagesBataille 2004Bobby JimNo ratings yet

- Programa Ruv Solar de Origen SolarDocument24 pagesPrograma Ruv Solar de Origen SolarVictor Tomas Tabilo PizarroNo ratings yet

- Ultraviolet Keratitis: From The Pathophysiological Basis To Prevention and Clinical ManagementDocument6 pagesUltraviolet Keratitis: From The Pathophysiological Basis To Prevention and Clinical ManagementJosé Eduardo Zaragoza LópezNo ratings yet

- CBCT Dosimetry: Orthodontic ConsiderationsDocument5 pagesCBCT Dosimetry: Orthodontic Considerationsgriffone1No ratings yet

- SiteDocument1 pageSiteAMBIENSEGNo ratings yet

- Solar Radiation Exposure and Outdoor Work: An Underestimated Occupational RiskDocument24 pagesSolar Radiation Exposure and Outdoor Work: An Underestimated Occupational Riskzen AlkaffNo ratings yet

- Non-Ionizing Radiation GuideDocument10 pagesNon-Ionizing Radiation GuidemohamedNo ratings yet

- New Continuous Total Ozone, UV, VIS and PAR Measurements at Marambio 64 S, AntarcticaDocument21 pagesNew Continuous Total Ozone, UV, VIS and PAR Measurements at Marambio 64 S, AntarcticaR. SanchezNo ratings yet

- Pi-Rard Et Al-2015-Journal of Cosmetic DermatologyDocument7 pagesPi-Rard Et Al-2015-Journal of Cosmetic DermatologyputrisarimelialaNo ratings yet

- Health PhysDocument7 pagesHealth PhysCarlos BustamanteNo ratings yet

- CBCT Dosimetry Orthodontic ConsiderationsDocument5 pagesCBCT Dosimetry Orthodontic ConsiderationsElzaMMartinsNo ratings yet

- Contribution of Mode B Ultrasound in The Management of Cataracts in BamakoDocument7 pagesContribution of Mode B Ultrasound in The Management of Cataracts in BamakoIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Consulta Do Atlas Solar GlobalDocument1 pageConsulta Do Atlas Solar GlobalAntonio CaioNo ratings yet

- Grade 12 ATP 2024 GeographyDocument9 pagesGrade 12 ATP 2024 GeographyngqubaanakoNo ratings yet

- Cancers 13 00498 v2Document22 pagesCancers 13 00498 v2Aiwi Goddard MurilloNo ratings yet

- Protection Agains UVDocument4 pagesProtection Agains UVPaul MathewNo ratings yet

- 2020 Materials Science Challenges in Skin UV ProtectionDocument19 pages2020 Materials Science Challenges in Skin UV ProtectionKristanto WahyudiNo ratings yet

- Antibacterial Effect of Laser Assisted Periodontal TherapyDocument7 pagesAntibacterial Effect of Laser Assisted Periodontal TherapyrindaNo ratings yet

- WMO Airborne Dust Bulletin 4 en Web 1Document8 pagesWMO Airborne Dust Bulletin 4 en Web 1wilmerNo ratings yet

- CORRECTED Iraya CADT Envi Work Proposal 2019 - 20190219Document16 pagesCORRECTED Iraya CADT Envi Work Proposal 2019 - 20190219Louis SantosNo ratings yet

- 2023 MATE ROV Competition Briefing 5Document11 pages2023 MATE ROV Competition Briefing 5Omar MedhatNo ratings yet

- 5 6321128026377555193Document16 pages5 6321128026377555193Malik OwaisNo ratings yet

- Delic 2016Document40 pagesDelic 2016Faisal BastianNo ratings yet

- Ultraviolet Radiation HazardsDocument1 pageUltraviolet Radiation HazardsJorge FigueroaNo ratings yet

- Patient Shielding During Dentomaxillofacial RadiographyDocument12 pagesPatient Shielding During Dentomaxillofacial RadiographyAainaa KhairuddinNo ratings yet

- Supplementary DIagnostic AidsDocument186 pagesSupplementary DIagnostic AidsRajshekhar Banerjee100% (1)

- Illuminating The SpectrumDocument2 pagesIlluminating The SpectrumdariellacatalanNo ratings yet

- Population de Ns Ity People /K MDocument3 pagesPopulation de Ns Ity People /K MCarlos ChaconNo ratings yet

- BúsquedadepapersDocument12 pagesBúsquedadepapersAnibal LópezNo ratings yet

- Estrelles Et Al. in Seed Conservation Turning Science Into Practice. PP 857-868Document12 pagesEstrelles Et Al. in Seed Conservation Turning Science Into Practice. PP 857-868Daniel BallesterosNo ratings yet

- Ghitany 2005Document8 pagesGhitany 2005KOHOLE WENCESLASNo ratings yet

- Refractivity Gradient of The First 1km of The Troposphere For Some Selected Stations in Six Geo-Political Zones in NigeriaDocument9 pagesRefractivity Gradient of The First 1km of The Troposphere For Some Selected Stations in Six Geo-Political Zones in Nigeriadayo JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Sunscreens and Their Usefulness: Have We Made Any Progress in The Last Two Decades?Document56 pagesSunscreens and Their Usefulness: Have We Made Any Progress in The Last Two Decades?Mirtha Del ArrayánNo ratings yet

- (Backes, 2018) 29Document12 pages(Backes, 2018) 29Corina Elena CozmaNo ratings yet

- Obedri Et. Al Soil Radon f84001Document12 pagesObedri Et. Al Soil Radon f84001Adesunloro Gbenga Mic.No ratings yet

- 1 - Helioterapia Nos Sul-AfricanosDocument6 pages1 - Helioterapia Nos Sul-AfricanosLuis Miguel MartinsNo ratings yet

- Multihazard Risk Atlas of Maldives: Summary—Volume VFrom EverandMultihazard Risk Atlas of Maldives: Summary—Volume VNo ratings yet

- Sultana 2021Document9 pagesSultana 2021Lia PuspitasariNo ratings yet

- Taksonomi TumbuhanDocument101 pagesTaksonomi TumbuhanLia PuspitasariNo ratings yet

- Materi IV Taksonomi Tumbuhan SambunganDocument101 pagesMateri IV Taksonomi Tumbuhan SambunganLia PuspitasariNo ratings yet

- GambariDocument5 pagesGambariLia PuspitasariNo ratings yet

- Profile Trigliserid Serum On Hypercholesterolemi Rats by Ethanol Extract of Lingzhi Mushroom (Ganoderma Lucidum)Document10 pagesProfile Trigliserid Serum On Hypercholesterolemi Rats by Ethanol Extract of Lingzhi Mushroom (Ganoderma Lucidum)Lia PuspitasariNo ratings yet

- Dapus AliskirenDocument1 pageDapus AliskirenLia PuspitasariNo ratings yet

- Ciulu, 2018 ReviewDocument20 pagesCiulu, 2018 ReviewLia PuspitasariNo ratings yet

- 1 Daun Jamblang PDFDocument5 pages1 Daun Jamblang PDFLia PuspitasariNo ratings yet

- 2 Walter, 2013Document6 pages2 Walter, 2013Lia PuspitasariNo ratings yet

- 1 Ghasemzadeh, 2018Document13 pages1 Ghasemzadeh, 2018Lia PuspitasariNo ratings yet

- 4 Perera PDFDocument6 pages4 Perera PDFLia PuspitasariNo ratings yet

- Update Manjaro - Buscar Con GoogleDocument9 pagesUpdate Manjaro - Buscar Con GoogleHéctor PérezNo ratings yet

- Human Resource Information Systems 2Nd Edition Kavanagh Test Bank Full Chapter PDFDocument30 pagesHuman Resource Information Systems 2Nd Edition Kavanagh Test Bank Full Chapter PDFSharonVargasgjme100% (11)

- CHG0071604Document18 pagesCHG0071604Luis Carlos CelyNo ratings yet

- Tourist ChecklistDocument1 pageTourist Checklistsanamariha01No ratings yet

- CFC Afghanistan Review, 27 August 2013Document5 pagesCFC Afghanistan Review, 27 August 2013Robin Kirkpatrick BarnettNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurs Characteristics, Functions & TypesDocument85 pagesEntrepreneurs Characteristics, Functions & TypesSanjeev Kumar Jain96% (24)

- A320180279 Muthi'ah Nurul Izzati UAS RMLT Penelitian KualitatifDocument14 pagesA320180279 Muthi'ah Nurul Izzati UAS RMLT Penelitian KualitatifRisaaNo ratings yet

- 3.0L L4 Oem Parts List: Illustration IndexDocument32 pages3.0L L4 Oem Parts List: Illustration IndexПетрNo ratings yet

- MET 207 Tool Design Week 4: Review - Basic Drawing and ToleranceDocument14 pagesMET 207 Tool Design Week 4: Review - Basic Drawing and ToleranceVINCENT MUNGUTINo ratings yet

- Vocabulary: Choose The Correct AnswerDocument2 pagesVocabulary: Choose The Correct AnswerMARI CARMEN SANCHEZ RUBIONo ratings yet

- ManagementDocument12 pagesManagementaakanksha_rinni0% (1)

- 5, Specification - DensitometerDocument2 pages5, Specification - DensitometerTadele WondimuNo ratings yet

- GSM Vs CDMA: Technical Difference Between GSM and CDMADocument3 pagesGSM Vs CDMA: Technical Difference Between GSM and CDMAvidyajai84No ratings yet

- L2 ICT - UNIT 2: Technology Systems Revision Template: Subject Notes Revision Done CPU Central Processing UnitDocument6 pagesL2 ICT - UNIT 2: Technology Systems Revision Template: Subject Notes Revision Done CPU Central Processing Unitapi-591240586No ratings yet

- BOQ Pack 4Document36 pagesBOQ Pack 4Prachi DongreNo ratings yet

- HS2016/2032/2064/2128 Alarm Panel: V1.0 User GuideDocument28 pagesHS2016/2032/2064/2128 Alarm Panel: V1.0 User GuidetestNo ratings yet

- Design and Implementation of LUT Optimization Using APC-OMS SystemDocument10 pagesDesign and Implementation of LUT Optimization Using APC-OMS SystemIJCERT PUBLICATIONS100% (1)

- Human SecurityDocument28 pagesHuman SecurityjmmllaarNo ratings yet

- Certificate of Analysis ListDocument3 pagesCertificate of Analysis ListJorge Luis ParraNo ratings yet

- Resume Syeda WaniaDocument1 pageResume Syeda WaniaAliNo ratings yet

- Gmax Tutorial - Installation of GmaxDocument18 pagesGmax Tutorial - Installation of GmaxCeren ErgulNo ratings yet

- Course Outline: 1. Introduction To WECC 2. Fundamentals of ElectricityDocument51 pagesCourse Outline: 1. Introduction To WECC 2. Fundamentals of ElectricityWoldemariam WorkuNo ratings yet

- Vision Without Action Is A Daydream. Action Without Vision Is A Nightmare.Document29 pagesVision Without Action Is A Daydream. Action Without Vision Is A Nightmare.yebegashetNo ratings yet

- HosukiDocument2 pagesHosukianggaradivaNo ratings yet

- Localytics - 8 Critical Metrics For Measuring App User EngagementDocument24 pagesLocalytics - 8 Critical Metrics For Measuring App User EngagementteinettNo ratings yet

- Civil Law - Definitions, Branches, ExamplesDocument13 pagesCivil Law - Definitions, Branches, Examplesgulowisuwdmuwq0% (1)

- IJCRT2306026Document8 pagesIJCRT2306026pankaj645924No ratings yet

- Payement of Wage Act, 1936 Unit-4Document8 pagesPayement of Wage Act, 1936 Unit-4rpsinghsikarwarNo ratings yet

- Exam4 MarksList ASO 362 PDFDocument52 pagesExam4 MarksList ASO 362 PDFManoj MalviyaNo ratings yet