Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Graham 2011 Time Machines and Virtual Portals The Spatialities of The Digital Divide

Uploaded by

Simon ODonovanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Graham 2011 Time Machines and Virtual Portals The Spatialities of The Digital Divide

Uploaded by

Simon ODonovanCopyright:

Available Formats

Progress in Development Studies 11, 3 (2011) pp.

211–27

Time machines and virtual portals:

the spatialities of the digital divide

Mark Graham

Oxford Internet Institute

University of Oxford, UK

Abstract: It is frequently argued that the ‘digital divide’ is one of the most significant development

issues facing impoverished regions of the world. Yet, even though the term is inherently spatial,

there have been no sustained efforts to examine the geographic assumptions underlying discourses

of the ‘digital divide.’ This article traces the history of the term, reviewing some of its tangible

effects and placing a focus on the temporal and spatial assumptions underpinning ‘digital divide’

discourses. Alternative formulations of the ‘digital divide’ are offered which take into account the

hybrid, scattered, ordered and individualized nature of cyberspaces.

Key words: Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs), digital divide, geography,

Internet, ICT for development, virtuality

I The information revolution and a spell the end of poverty (Purcell and Toland,

‘digital divide’ 2004). Network connections are therefore

There has been much talk of an economic posited as crucial to obtaining the raw materials

and social revolution taking place over the of the post-industrial, third-wave, networked

last few decades. This revolution has been as- society (Castells, 2002).

signed a variety of terms: a ‘computer revolu- There have always been concerns that

tion,’ a ‘knowledge economy,’ an ‘information divergent levels of access to Information

revolution,’ or a ‘third-wave’ in human his- and Communication Technologies (ICTs)

tory bringing about a post-industrial, post- and uneven global flows of information

service and post-modern ‘network society’ will exacerbate economic and socio-spatial

(Benkler, 2006; Berkeley, 1962; Castells, segregation. However, it is only relatively

1996; Dahrendorf, 1977; Drucker, 1969; Jones, recently that the ‘digital divide’ has entered

1982; Machlup, 1962; Toffler, 1980). These into popular discourse. The term has had far-

revolutions have been widely touted as having reaching effects: hundreds of projects around

far-reaching and largely-positive outcomes for the world are framed with the intention of

society in general. It has been argued that the solving or bridging a ‘digital divide’ and billions

information revolution can take away power of dollars have been spent to achieve such

from centralized structures, spread democracy goals. This article therefore begins by charting

(see Ayres, 1999; Barber, 1998) and of course the history of the ‘digital divide’ from concerns

© 2011 SAGE Publications 10.1177/146499341001100303

212 Time machines and virtual portals

about connecting the global peripheries to the grounded vision of the relationships between

imperial centres in the era of the telegraph to geography and technology. Specifically, by

the coining of the term at the beginning of the taking into account the economic, cultural,

twenty-first century. political and technological positionalities of

In order to understand why the trope of a each person attempting to access cyberspace,

‘digital divide’ has been able to command such as well as both the material and cyber-divides

large investments into technology projects that obstruct communication through the

(i.e. resources that could conceivably be in- Internet, we can move away from some of

vested in a variety of other economic and social the problematic imaginings of the Internet as

development programmes), the temporal and a panacea for economic development.

spatial assumptions embedded into popular

uses of the term are examined in detail. This The origins of the ‘digital divide’

article continues by arguing that solutions Virtual and non-proximate connections are

to (or bridges across) the ‘digital divide’ are a cornerstone of the new economy and net-

commonly employed to posit movement work society. To be disconnected is to be both

along temporal and spatial axes of develop- economically and socially absent from the

ment. Like many other terms adopted into information/knowledge revolution. This idea

development discourse over the past few cen- that being disconnected from the tools and the

turies, the ‘digital divide’ is frequently used to content of the information revolution could

describe an obstacle to movement of people cause social polarisation amongst individuals,

and places temporally along a pre-defined path groups, and regions has been highlighted for

of development. almost as long as commentators have been

The term is also frequently used to make a noting the socio-economic importance of

uniquely-spatial argument. Within academic, technological changes.

policy and popular literature, there is often Even before the invention of electronic

a common assumption that the Internet has computers and the coining of the ‘digital

brought into being a distinct type of geography. divide,’ there was, in the era of the telegraph,

Two nodes on a network (e.g. a Londoner sell- a well-circulated idea that communication

ing books using an online marketplace and a technologies would bring about positive eco-

Parisian buying books using that same online nomic and social development in the global

marketplace) are described as sharing more periphery (Marvin, 1988). During this time,

than a topological connection; they are instead one of the inventors of the telephone, Amos

seen to be occupying the same virtual space, Dolbear, remarked that ‘any device that

cyberspace or ‘global village’ (cf. McLuhan, enlarges one’s environment and makes the rest

1962). The ontology of a global village is crucial of the world one’s neighbours is an efficient

to understanding the discursive effects of the mechanical missionary of civilisation and

‘digital divide.’ Within this worldview, people helps to save the world from insularity where

and places can be separated into two groups: barbarism hides’ (quoted in Marvin, 1988: 192).

those with access to the ‘global market place’ In other words, communication technologies

and ‘information revolution,’ and those unable would develop the disconnected peripheries of

to gain access and participate. As such, it is the world into cultural and economic models

easy to see how such enormous amount of of the centre (see also Tesla, 1993).

resources are spent to end what a number of More recently, Singer (1970) highlighted

prominent commentators such as Colin Powell an international technological dualism be-

have dubbed as ‘digital apartheid’. tween rich and poor countries, while the

Finally, the article concludes by rethinking term ‘New World Information Order’ was

the ‘digital divide’ in order to employ a more used within UNESCO to describe to uneven

Progress in Development Studies 11, 3 (2011) pp. 211–27

Mark Graham 213

global flows of information (Mowlana, 1997). There has been a recent explosion in usage

Castells (1998) has similarly argued that the of the term where, for example, both the

information revolution would exacerbate World Bank and the OECD define the ‘digital

socio-spatial segregation and create ‘dual cities’ divide’ as a gap between people and places

of inhabitants that occupy vastly different with regard to their access to ‘information

spheres of knowledge. and communication technologies (ICTs) and

It was around this time that the trope of their use of the Internet for a wide variety of

a ‘digital divide’ began to emerge. Its exact activities’ (OECD, 2008). Almost every major

origins are unknown (Compaine, 2001), but it international development agency now has a

became rapidly popularized due to efforts by programme to tackle the ‘digital divide’ and

high-ranking US government officials (most every industrialized nation (as well as many in

notably President Clinton, Vice-president the global South) devotes significant resources

Gore, and Larry Irving, the head of the to reversing domestic ‘digital divides.’

National Telecommunications Infrastructure One of the earliest was the E-rate1 pro-

Administration (NTIA)) (Servon, 2002). grammeme in the United States, where

Perhaps because few people could anticipate legislation was passed allowing a fee to be

the ways that the Internet would reorganize levied on all interstate and international tele-

communications services. Proceeds were

socio-economic relationships across the globe,

then disbursed to schools and libraries to

the term was initially used to simply describe

provide telecommunications service (usually

access (or a lack thereof ) to computers. For

Internet access). Over one billion dollars has

example, in a report by the NTIA in 1998 (one

been allocated to the programme and during

of the first references to the term), the ‘digital

negotiations on how to fund the programme,

divide’ is specifically used to refer to ‘computer

many saw even that figure as insufficient to

ownership and usage’ (NTIA, 1998).

tackling the digital divide (Macavinta 1998).

In more recent usages, focus has shifted Another scheme, and one of the most cited

from access to computing hardware to access examples of a project that aims to reduce the

to communication technologies or more ‘digital divide’ is the One Laptop per Child

specifically: the Internet. Often it is even used (OLPC) programme. Hundreds of newspaper

to refer to differences between reliable and and magazine articles promote the project as a

fast connections to the Internet and slow and solution to the digital divide, and the project’s

intermittent ones (Compaine, 2001). With website even contains one hundred and forty

the advent of ubiquitous computing and the references to the term. The goal of the pro-

peer-production of information (Graham, gramme is to distribute inexpensive laptops

2011; Graham, 2010b), it is likely that the to children across the world. With 1.5 million

‘digital divide’ will increasingly also be used to laptop orders to date, the project has at-

refer to integration with the many ubiquitous tracted at least US$100 million in funding.

networked technologies embedded into daily There are, however, plans to massively expand

life (Greenfield, 2006). Yet, as the Internet the project and secure US$2.6 billion from the

remains the focus of most contemporary public and private sectors to distribute 100

references to the ‘digital divide,’ the remainder million OLPC laptops (Deva, 2008).

of this article will continue to equate the The ‘digital divide’ has been recognized

‘digital divide’ with access to the Internet. as an issue at a range of scales including urban

Nonetheless, it should be noted that instead of and regional governments. For instance, many

having a fixed meaning, the term can be seen of the (at least) thirty six cities2 across the

to be a moving signifier, keeping track with world that have invested heavily to establish

concurrent technological changes. free wifi networks accessible to all residents

Progress in Development Studies 11, 3 (2011) pp. 211–27

214 Time machines and virtual portals

also frame their work within the trope of II Ontological underpinnings

a digital divide (Gibbons and Ruth, 2006; Irrespective of how any ‘digital divide’ dis-

Goth, 2005; Kvasny and Keil, 2005; Tapia course is formulated, the trope is always used

et al., 2006). Even former California Governor to refer to a gap in capabilities, potentials and

Arnold Schwarzenegger has announced that possibilities between different groups or places.

US $460 million will be made available to Furthermore, a ‘digital divide’ is never posited

combat the ‘digital divide’ – defined as ‘the as a beneficial or positive outcome; it is rather

lack of broadband data transmission to rural something to be alleviated, filled, narrowed,

and poor urban areas’ (Geissinger, 2006). reduced, stepped over or shrunk. However,

The private sector has also contributed there remain a range of diverse visions about

enormous funds to ‘digital divide’ related devel- what the precise outcomes of bridging a ‘digital

opment programmes. For example, Google divide’ would be. This is in part because the

and the HSBC are investing US$65 million to trope of a ‘digital divide’ is inherently spatial and

launch medium orbit satellites that will pro- as such necessarily rests on distinct ontologies

vide Internet access to the three billion people of the relationships between time, space and

without Internet access (Kirk, 2008); in 2006, technology.

Intel announced that they would spend one

billion dollars to extend wifi networks across Temporal assumptions

the globe and train teachers (Markoff, 2006). There is a long history in the academic and

Myriad other smaller projects also employ the policy literatures of seeing development as

‘digital divide’ as a framing mechanism. While a progression along a linear temporal path.

motivations are likely more economic than Rostow (1960), for example, created a five-

altruistic, the fact that such enormous sums stage model of economic growth and asserted

are being spent under the banner of alleviating that all societies could be placed somewhere

a ‘digital divide’, does highlight the discursive in-between a traditional subsistence economy

weight that the idea contains. and the end-point of ‘high mass consumption’.

The sums invested under the banner Much of the rhetoric on the ‘digital divide’ is

of reducing a ‘digital divide’ are staggering. no exception. On the temporal path of digital

The combined figures mentioned above are development, many posit a forwards and a

alone larger than the gross domestic products backwards with people and places who are

of some countries and beg two questions: behind, using ICTs to ‘catch up’ with those

Why are such massive sums invested in the who are in front. Norris (2001: 5), for example,

name of bridging a ‘digital divide’ and what argues that:

outcomes do funding organisations expect

to achieve by narrowing ‘digital divides’? To …most poorer societies, lagging far behind,

plagued by multiple burdens of debt, disease,

answer these questions, we can turn to the

and ignorance, may join the digital world

ways that the trope is being put to use. The decades later and, in the long-term, may

following section therefore outlines some of ultimately fail to catch up.

the temporal and spatial assumptions that

are frequently embroiled into ‘digital divide’ The idea of a linear path of digital devel-

discourses. The temporal assumptions will opment is also prominent in language em-

only be covered briefly, primarily because simi- ployed by large international organisations.

lar arguments have already been made by a For instance, after the 2000 G8 summit in

number of development theorists. The spatial Okinawa, the group of eight of the world’s

assumptions, however, are more unique to most influential nations declared that:

discourses surrounding the ‘digital divide’ and The challenge of bridging the international

will thus be brought to the fore. information and knowledge divide cannot…

Progress in Development Studies 11, 3 (2011) pp. 211–27

Mark Graham 215

be underestimated. We recognise the priority theory and practice can greatly reduce the

being given to this by many developing coun- possibilities for open politics (see also Escobar,

tries. Indeed, those developing countries

1995; Ferguson, 1994). It is clear that digital-

which fail to keep up with the accelerating

pace of IT innovation may not have the oppor- development is no exception and imagina-

tunity to participate fully in the information tions of linear temporal paths of development

society and economy. (G8, 2000) can similarly close down discussion and reduce

the scope for contingent alternatives.

It has also been argued that communication

technologies can be employed to enable

Spatial assumptions

‘catching up’ to happen at a sub-national

Some commentators have suggested that both

level. Borgida et al. (2002: 128), for example,

the discursive power and the problematics

proposed that:

inherent to the ‘digital divide’ rest on techno-

In order to maintain a healthy economy and logical determinist uses of the trope (see

a vibrant workforce, electronic networks Warschauer, 2003a). For example, Warschauer

are one way some rural communities are

attempting to catch up to urban areas.

(2003b) notes that the ‘digital divide’ is

posited as a technological problem that has a

Others still point out that different demo- necessary technological solution. While the

graphic groups separated by a ‘digital divide’ simplicity of such arguments makes them

can ‘catch up’. For instance, Hoffman and simultaneously appealing and problematic

Novak (1998) argue that socio-economic (albeit to different audiences), I would, rather,

racial differences will ‘disappear as African maintain that a lot of the power embedded in

Americans “catch up” to whites in terms of discourses about the ‘digital divide’ lies in the

time spent online’.3 Even amongst the few fact that they are able to postulate movement

authors who maintain that the ‘digital divide’ is not only in time, but also across space. Much

not a pressing issue, the language of ‘catching of the spatiality embedded into rhetoric about

up’ is prominent: the ‘digital divide’ refers to the geography of the

… though developing countries have fallen divide itself. That is, a divide can be thought

behind economically over the past decades, to exist between the North and South, East

they managed to catch up digitally. (Fink and and West, urban and rural, etc. However,

Kenny, 2003: 19) the ‘digital divide’ is increasingly being used to

Using ICTs to bridge a ‘digital divide’ is thus refer not to a divide in capabilities or technical

in many cases seen as a way of moving people ability, but rather to a more existential divide:

and places temporally along a pre-defined namely, an actual divide in shared co-presence

path of development. This line of thought in cyberspace.

is perhaps best articulated by Nirj Deva, a

member of the European Parliament, who Cyberspace

in relaying plans to make universal access to To fully explore the ways that space is con-

ICTs the ninth United Nations Millennium ceptualized and used as an epistemological

Development Goal exclaimed that ‘We are and ontological framework within discourses

not delivering a computer. We are delivering of a ‘digital divide’, it is first necessary to more

a time machine. A time machine that is so thoroughly explore the nature of cyberspace

enormously transformational that everything itself. Like the ‘digital divide,’ cyberspace is

after that is changed. Changed forever’ (Deva, an inherently geographic concept. When

2008). As James Ferguson (1999) and others employed as a metaphor within the contexts

have previously noted, the linear, teleological of discussions about socio-economic change,

assumptions that underlie much development cyberspace can become a useful heuristic

Progress in Development Studies 11, 3 (2011) pp. 211–27

216 Time machines and virtual portals

device upon which issues of spatial division and synchronous communication technologies, like

unequal access can be framed. the telegraph, would bring humanity together

However, cyberspace has often taken on in some sort of shared space (Standage,

an ontic role. Cyberspace, in this sense, is 1998). For instance, in 1846, in a proposal

conceived of as both an ethereal, alternate to connect European and American cities

dimension which is simultaneously infinite via an Atlantic telegraph, it was stated that

and everywhere (because everyone with an one of the benefits would be the fact that

Internet connection can enter), and as fixed ‘all of the inhabitants of the earth would be

in a distinct location, albeit a non-physical one brought into one intellectual neighbourhood

(because despite being infinitely accessible, and be at the same time perfectly freed from

all willing participants are thought to arrive those contaminations which might under

into the same marketspace, civic forum and other circumstances be received’ (Marvin,

social space). Cyberspace, in this sense, truly 1988: 201). Twelve years later, after the

becomes a global village. Therefore, cyber- completion of the Atlantic telegraph, The

space, like other spaces, has a mappable Times proclaimed that ‘the Atlantic is dried

form, but exists beyond the material world up, and we become in reality as well as in

(Batty and Miller, 2000; Dodge and Kitchin, wish one country’ (quoted in Standage,

2001). It becomes a shared virtual reality and 1998: 80). In the 1960s, Marshall McLuhan’s

a consensual hallucination (Gibson, 1984), philosophy of media posited a future not too

which is ‘generating an entirely new dimension different from proclamations about the power

to geography’ (Batty, 1997: 339). of communication technologies a century

The precise sources of this, a priori onto- earlier. He noted that ‘electric circuitry has

logy of cyberspace as simultaneously infinite overthrown the regime of “time” and “space”

and fixed, are unclear. One argument that and pours upon us instantly and continuously

has been put forward is that cyberspace as a concerns of all other men. It has reconsti-

‘global village’ satisfies a dualistic philosophy tuted dialogue on a global scale...” Time”

of space that has only relatively recently been has ceased, “space” has vanished. We now

replaced with a monistic one (Wertheim, live in a global village’ (McLuhan and Fiore,

1999). Descartes, for instance, separated 1967: 63).

reality into the res extensa (the realm of cor- Such ideas were equally prevalent in

poreal substance and matter) and the res the early days of the Internet. John Barlow

cognitans (the ethereal realm of thoughts and (1996), for example, in his Declaration of the

non-material, spiritual existence). Variations of Independence of Cyberspace, boldly asserted

this dualistic worldview were widely accepted that ‘cyberspace does not lie within your

in western society until the materialism of borders’ and ‘ours is a world that is both every-

the scientific revolution resulted in a shift where and nowhere, but it is not where bod-

towards an understanding of reality as being ies live’. Trotter Hardy (1994), in a discussion

comprised solely of the physical realm. With about appropriate legal regimes for cyberspace,

the invention of the Internet, Margaret similarly posits the idea that cyberspace is a

Wertheim argues that ‘the emergence of a distinct and separate space.

new kind of nonphysical space [cyberspace] was Representations or allusions to the Inter-

almost guaranteed to attract “spiritual” and net in popular culture often reinforce the

even “heavenly” dreams’ and thus be viewed ontic role given to cyberspace. For instance,

as a ‘technological res cognitans’ (Wertheim, Dave Chappelle’s (2004) comedy sketch, titled

1999: 38). What if the Internet was a place that you could

Even before the coining of the term ‘cyber- go to? in which he strolls around cyberspace,

space’, commentators were speculating that deliberately gives the Internet physical, spatial

Progress in Development Studies 11, 3 (2011) pp. 211–27

Mark Graham 217

and fixed properties.4 The Matrix trilogy of contain the idea that cyberspace contains

films, which in many ways reverses the ideas ‘a’ fixed marketplace, which despite being a

of cyberspace and physical space, can similarly singular location, is infinitely accessible.

be seen to assign to the virtual an ontic role It is interesting then, to note the differ-

(Wachowski and Wachowski, 1999). The ences between the ontology of cyberspace as

Matrix (an illusion of the physical world) can simultaneously infinite and fixed that is pre-

be exited from anywhere using a telephone. sent in the words of businesses, development

Doing so brings the user of the telephone organizations, and much of the media, and

back into a shared alternate dimension. Neal the ways that academic geographers have

Stephenson’s (1992) novel, Snow Crash, also theorized the existence of cyberspace. Geo-

describes a three-dimensional evolution of graphers have largely moved beyond the

the Internet (which he dubs ‘the Metaverse’) idea that space-transcending possibilities of

in which users can attain co-presence in a vir- cyberspace will render geography meaningless

tual dimension accessible from anywhere on (cf. Cairncross, 1997; Couclelis, 1996). Spatial

earth. There have actually been a number of differences continue to exist because, far from

highly successful real-life implementations of being uniformly distributed, communications

versions of Stephenson’s Metaverse. Second technologies and opportunities for production

Life (with over fifteen million users) and World and consumption have a pronounced geo-

of Warcraft (with over eleven million users) are graphic bias (Castells, 2002; Dodge and

two of the most popular examples. Kitchin, 2001; Gorman and Malecki, 2002;

It is likely that development professionals Townsend, 2001; Zook, 2000). In part because

have also played a hand in either creating or of its geographic bias, cyberspace is far from

reproducing this discourse through reports being a ‘global village’ or a universally accessible

by, or reports used by, international organisa- marketplace and indeed has its own mappable

tions. Kirkman and Sachs’ Global Information geographies and uneven topologies (Brunn

Technology Report, for instance, implies that and Dodge, 2001; Zook, 2005, 2006) (see for

there is ‘a’ market that can be tapped by enter- example, the map of the structure of cyber-

ing the infinity of cyberspace (Kirkman et al., space in Figure 1).

2002). Similar conceptions of ‘a’ global mar-

ket can be found in the World Economic Cyberspace and the ‘digital divide’

Forum’s other Global Information Technology Graham (1998) argues for complex and parallel

Reports and Global Competitiveness Reports, as considerations of electronic and physical pro-

well as publications by the World Trade Organ- pinquity. Technology is described as being

ization, various UN agencies, the World Bank an appendage to life in the physical world

and countless other international organisa- rather than a replacement. Communications

tions and NGOs (cf. Porter et al., 2002). technologies can alter and redefine relative

The World Bank’s ‘Artisan as Entrepreneur’ distance, but they are unable to cancel out

project supports concrete programmes that geography, and as a result we live in a state of

aim to bring ‘crafts from Latin America, Asia, suspension between our de-localized presences

and Africa onto the global market’ (World and our physical existences (Castells, 2002;

Bank, 2000: 3, emphasis added). Hundreds Robins, 1995).

of articles in the popular press recycle similar Others have suggested envisioning cyber-

stories about the potentials of e-commerce space ‘as a socially constructed discourse

and the Internet as a means of providing that simultaneously reflects and constitutes

access to ‘a’ global market that can be entered social reality’, in order to focus on the social

through the gateway of the Internet (cf. outcomes it brings about (Warf, 2001: 6).

Faucon, 2001). Many of these articles again Kitchin (1998) recommends that cyberspace

Progress in Development Studies 11, 3 (2011) pp. 211–27

218 Time machines and virtual portals

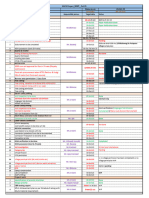

Figure 1 A map of the Internet

Source: This image was created by Matt Britt. Available at http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/

d/d2/Internet_map_1024.jpg

Note: The map is only thirty per cent of the class C networks reachable in 2005. Nodes represent IP addresses

and the length of each line is indicative of the delay between those nodes. Lines are variably shaded according

to the domain suffixes associated with each address.

be conceptualized as existing in a symbiotic situated in real space’ (Cohen, 2007: 218).

relationship with geographic space. Cohen In other words, the Internet and other

(2007) similarly suggests that cyberspace is ICTs can give rise to an individual sphere of

an evolution and extension of everyday spatial hybrid geography in which certain distance-

practice rather than a separate space. She transcending activities can be performed

notes, ‘cyberspace is in and of the real-space while being simultaneously embedded in, and

world, and is so not (only) because real-space influenced by, the performer’s positionality in

sovereigns decree it, or (only) because real- material space.

space sovereigns can exert physical power It should be noted that, the global village

over real-space users, but also and more conceptualization of cyberspace is far from

fundamentally because cyberspace users are a dominant discourse. For example, some

Progress in Development Studies 11, 3 (2011) pp. 211–27

Mark Graham 219

popular writings about the Internet do often in northeast Thailand in order to allow silk

allude to notions of hybridity, and it is unlikely weavers access to a global marketplace found

that many people imagine that they are en- that a priori ontologies of cyberspace that

tering into another dimension when they are posit a universally accessible yet fixed and

Googling, Facebooking and Twittering from bounded dimension rarely match up to the

their mobile devices. Yet, it remains that such experiences that silk sellers have with the

conceptualizations of a hybrid virtual/physical Internet (Graham, 2008a, 2010a). The Inter-

sphere of existence for Internet users rarely net was not being used as a middle ground

enter into discussions of a ‘digital divide’. Uses or an intermediate virtual space that bridges

of the ‘digital divide’ are instead often grounded non-proximate buyers and sellers. Instead,

in an ontology that presents cyberspace as producers and merchants that were able to

being simultaneously infinite and fixed. Hence,

use the Internet as a tool to sell silk were, in

the ‘digital divide’ becomes not a statistical

most cases, interacting with non-proximate

divide between people or places, but rather

customers through highly individualized and

an existential divide between those that can

access a shared cyberspace and those on the non-transparent conduits (see also, Graham,

other side of a gulf who remain rooted to the 2008b; Sheppard, 2002). Transactions thus

physical world. took place not in an alternate virtual space,

This ontic divide becomes all the more but in the real world through virtual conduits.

significant when seen in the contexts of the The primary reason for the disconnect be-

‘information revolution’ and the literatures on tween many of the oft-repeated, a priori

the networked society. Those without access ontologies of cyberspace and the realities of

to the ‘global village’ are therefore seen to concrete attempts to use ICTs to reduce a

be segregated from the contemporary socio- ‘digital divide’ was that cyberspace is not a

economic revolution taking place. Some, such container of a singular globally-accessible

as the former US secretary of State Colin market. The study demonstrated that market

Powell (2000) and the chief executive of spaces brought into being by the Internet are

3Com (Macavinta, 1998), have on separate instead often scattered, disconnected, indi-

occasions gone so far as to term this exclusion vidual, hybrid and perhaps most important,

digital apartheid’. ranked and ordered. Warschauer (2003a: 297),

When relying on the ‘global village’ con- similarly argues that:

ceptualization of what ICTs can do to space,

…just as the ubiquitous presence of other

it is easy to see how the discourse of a ‘digital

media, such as television and radio, has done

divide’ has been able to attract such enormous nothing to overcome information inequality

amounts of funding and interest. But it still in the United States, there is little reason

remains to be seen whether powerful claims to believe that the mere presence of the

about the effects of ICTs on those who are Internet will have a better result.

left out of the information revolution will prove

prescient. Because of the contemporaneity of In the contexts of the Egyptian educational

the Internet, there remains no comprehen- system, Warschauer found that despite

sive body of empirical literature on the effects significant expenditures to reduce a ‘digital

of ICTs and cyberspace on socio-economic divide’, students were never being teleported

processes. However, existing research does into virtual forums of learning or cyber-

indicate that it is unlikely that ICTs can libraries. 5 Instead, despite the necessary

ever allow co-presence in a singular ‘global hardware being in place in schools across

village’. the country, access to knowledge remained

For instance, one study on attempts to constrained by multiple layers of restrictive

use the Internet to bridge a ‘digital divide’ political, social and bureaucratic factors. Here

Progress in Development Studies 11, 3 (2011) pp. 211–27

220 Time machines and virtual portals

again, it is clear that cyberspace cannot be is helpful to use Julie Cohen’s formulation

viewed as a disconnected, floating dimension. of the cyberspace metaphor. Cohen argues

The Internet was instead embedded into the that cyberspace ‘does not refer to abstract,

many restrictive social, political and economic Cartesian space, but instead expresses an

factors that exist outside of the virtual realm. experienced spatiality mediated by embodied

In both of these examples, it is clear that a human cognition. Cyberspace in this sense is

reliance on the ‘digital divide’ discourse and relative, mutable, and constituted via the inter-

its necessary linkages to specific ontologies of actions among practice, conceptualisation, and

cyberspace obscures and even depoliticizes representation’. In other words, cyberspaces

solutions to fundamental problems related operate as ‘as both extension and evolution

to the ability to access information and com- of everyday spatial practice’ (Cohen, 2007)

municate non-proximately. and are perpetually created and re-created

through highly-individualized interactions.

III Re-theorizing the ‘digital divide’ Cyberspace is therefore not a singular ontic

The critiques offered in this article are not entity and no amount of work to bridge a

meant to suggest that the notion of a ‘digital ‘digital divide’ could ever create such a space.

divide’ is theoretically ineffectual. This article is School children in Egypt, village weavers in

in addition by no means an attempt to suggest Thailand and everyone else thought to be on

that efforts made to connect the disconnected the wrong side of a ‘digital divide’ cannot enter

should not be made. Rather, a richer formulation into a ‘global village’ to learn and trade be-

of the ‘digital divide’ is needed: specifically, one cause a ‘global village’ has no ontic basis.

that takes into account theorizations of hybrid The concept of a ‘digital divide’ should thus

and embedded cyberspaces. Grounding any be pluralized, localized and grounded in more

theorization of a ‘digital divide’ in alternate appropriate spatial frameworks. The initial

spatial underpinnings would thus allow more

material divide concerns a lack of access to

realistic expectations of spatial effects of digital

the entry points of cyberspace. This divide is

technologies to be created.

almost entirely a question of resources. People

The ‘digital divide’ should not be con-

need the hardware (computer, modem, router,

ceived of as a singular chasm separating an

etc.), software (i.e. browser and email client)

Internet user from communication, knowledge

and an Internet connection (either hardwired

or interaction. Such a conceptualization would

imply that, were a metaphorical bridge to or a wireless access point). Without access

be built, the Internet user could easily pass to all of the above, there can be no entry

over the chasm and enter the cyberspace into any cyberspaces. Although the material

that she or he was previously divided from. ‘digital divide’ revolves entirely around access

The spatiality of this metaphor is grounded to hardware, software and a connection point,

in a vision of cyberspace as a ‘global village’ the solution to it cannot be entirely economic.

and, as such, allows both cyberspace and the Myriad other factors related to the politics and

‘digital divide’ to take on ontic roles. Instead, practices of access (such as gender, class and

two types of divides should be recognized: the age) can be as equally inhibitive as financial

physical divides separating people from access barriers. Telecentres and Internet cafes, for

to cyberspaces and the cyber-divides that example, are often highly-gendered spaces

obstruct movement between cyberspaces. and can be unwelcoming to women, while

wifi access points by their nature discriminate

Material divides against the poorest members of society by

Rather than imagining cyberspace as a requiring users to own a laptop computer. Many

‘global village’ that can be stepped into, it of these points have indeed been recognized

Progress in Development Studies 11, 3 (2011) pp. 211–27

Mark Graham 221

in recent formulations of the ‘digital divide’ even individuals are all able to construct layers

(cf. Barzilai-Nahon, 2006; Chakraborty and of censorship that effectively make parts of

Bosman, 2005; Crang et al., 2006; Gilbert and the Internet inaccessible (cf. Faris, Wang

Masucci, 2005; Gilbert et al., 2008; Grasland and Palfrey, 2008). These attempts to block

and Puel, 2007; Schwanen and Kwan, 2008; access to cyberspaces include: the situation

Selwyn, 2004). in North Korea where only a few government

Yet, in part because of the existence of the officials are permitted to access the Inter-

‘global village’ ontology of cyberspace, there is net (Reporters Without Borders, 2006); the

often a pollyannish assumption that once the French Government’s successful attempts to

material ‘digital divide’ is bridged, the many restrict the visibility of Nazi memorabilia on-

problems attributed to ‘digital divides’ will also line (Drissel, 2006); the restriction of access to

vanish. Or, in other words, despite the myriad websites deemed to threaten national security

barriers to access, once people are placed in a variety of countries including China,

in front of connected terminals, the ‘digital Iran, Saudi Arabia and Thailand (Dann and

divide’ becomes bridged and the previously Haddow, 2007; Graham and Khosravi, 2002;

disconnected are consequently able to enter Hofheinz, 2005; Kluver and Banerjee, 2005;

cyberspace. Xue, 2005); efforts by businesses and schools

to limit access to only approved websites

Virtual-divides (Hamade, 2008); and commercial censorship

Once connected, entirely different divides are software designed to prevent children from

potentially encountered within the experienced accessing some websites.

and imagined fabrics of cyberspace. After In terms of virtual topology, there can

overcoming the initial physical divide, Internet therefore never be a singular divide. Space

users still have not necessarily achieved virtual created within the Internet is not binary in the

co-presence with all the other Internet users, sense that a person is either inside or outside,

nor are they free or able to enter all cyber separated by a ‘digital divide’. There are rather

places. The map of the Internet (in Figure 1) countless small (although important and often

illustrated a useful conceptualization of the insurmountable) ‘digital divides’ preventing

topologies of the Internet. Instead of being a movement through the topologies of the

singular location, users are able to engage with Internet and limiting access to cyberspaces.

(or through) billions of nodes which are often These divides can take myriad forms, but all

poorly networked. ultimately relate to issues of accessibility and

Even when there is a large amount of visibility. Three of the most common divides

convergence to specific cyberspaces in which are discussed below.

co-presence can be attained (traditional chat Cultural differences also play a large role in

rooms or more recent virtual environments6 determining the ways in which Internet users

that can be embedded into any webpage are are able to interact and access information

examples), cyber presence is rarely static. (cf. Recabarren, Nussbaum and Levia, 2008).

Internet users navigate through not only the Language is likely the largest and most sig-

network of the Internet, but also through nificant barrier to access on the Internet. A

the often labyrinthine topologies of individual majority of Internet users are now non-native

websites. English speakers (Shea, Ariguzo and White,

The most apparent are those related to 2007). However, it remains that English is a

censorship and the securitization of cyber- dominant language on the Internet (Flammia

spaces (Deibert, 2003). Nation states, gov- and Saunders, 2007) and despite recent

ernment agencies, the private sector and developments in machine translation, those

Progress in Development Studies 11, 3 (2011) pp. 211–27

222 Time machines and virtual portals

not fluent in English are likely to face signifi- to a page is an indication of the quality or im-

cant barriers to both non-proximate communi- portance of that page. The ranking that a

cation and organizing online content into webpage ultimately receives from a search

meaning. The contexts and positionalities algorithm is critically important for online

of information sources and those accessing visibility as research has shown that only a

virtual information also strongly influence small minority of Internet searchers move

how information can be retrieved and used. beyond the first ten results presented to them

Withers and Grout (2006), for instance, in (Jansena et al., 2000).

their discussion of virtual archives, argue In practice, this means that the websites of

that information on the Internet can often be organizations already well integrated into the

interpreted in ways that differ sharply from social and economic fabric of large segments of

the emotional and aesthetic relationships society (e.g. the New York Times or Amazon.

between information sources and the readers com) are more likely to be made visible

of information in the non-virtual world. Fur- than the websites of smaller organizations.

thermore, barriers exist which limit not only To return to the two examples used earlier

the comprehension and interpretation of in the article, we can see that visibility can

content, but also its creation. For example, cause divides for producers and consumers of

digital ethnographies have shown that in wikis,

information. Many Thai silk sellers construct

methods employed to resolve disagreements

elaborate websites which end up not being

about the ways a subject should be repre-

found by any potential buyers due to the fact

sented are frequently opaque and often favour

that they have low rankings in search engines.

distinct demographics (usually young western

Egyptian school children similarly might in

males) (O’Neil, 2009).

theory have access to an enormous amount

Finally, there are the divides brought about

of content on the Internet, but if there is no

by online visibility (or a lack thereof). There

are immense difficulties involved in being able apparent route to access specific websites

to organize, classify and move through the (i.e. they are not indexed in search engines or

thirty billion7 web pages on the Internet (cf. listed in directories), the children inevitably

Senécal, 2005). Ranking and ordering systems will not visit those sites. Therefore, even when

(i.e. search engines and online directories) are ‘digital divides’ have, in theory, been bridged

powerful factors which allow some informa- (e.g. allowing Thai silk sellers to engage in

tion to remain visible while other content stays e-commerce and Egyptian children access to

hidden. As a consequence, a website can exist educational materials), there can, in practice,

in cyberspace and be accessible from anywhere remain fundamental divides brought about by

in the world, but essentially be cloaked and a simple lack of visibility.

invisible if it is not networked. An issue faced

by those attempting to access the websites of IV Conclusion

less well-known people and organizations is There is a widespread assumption that an

the fact that all sorting, ordering and ranking information revolution is taking place in con-

systems are inevitably hierarchical (Zook and temporary society. Economic, cultural and

Graham, 2007a, 2007b). The Google search political interactions and relationships are

engine, for example, has a search algorithm increasingly grounded in ICTs and are reliant

that is modelled after the academic search on unimpeded flows of information over space.

literature. The algorithm is designed under However, a majority of the world’s population

the assumption that the number of hyperlinks is being excluded from these new ways of

(and ultimately the rank of those hyperlinks) organizing society (only 22 per cent of Asians

Progress in Development Studies 11, 3 (2011) pp. 211–27

Mark Graham 223

and 11 per cent of Africans have access to the the sense that a person is either inside or

Internet) (Internet World Stats, 2009). As outside, separated by a ‘digital divide’. There

a result, many individuals, organizations and are rather countless small (although often

governments have expressed concern and insurmountable) ‘digital divides’ preventing

invested enormous sums of money to eliminate movement through the topologies of the Inter-

a perceived ‘digital divide’. net and limiting access to cyberspaces.

Some of these projects have been highly The consequences of being excluded from

effective, and indeed, Internet usage rates in the Internet can in many cases be severe.

much of the world are growing rapidly. Yet it People can be left out of networks and flows

remains that success stories can be difficult to of information, thereby reinforcing existing

find. There are too many examples of failed social, economic and political power struc-

development projects, computers collecting tures. While ICTs cannot alone flatten

dust and websites hidden to all but the most structural and social forces of exclusion and

proficient of searchers. More importantly, inequality they can, nonetheless, be a powerful

there are too many examples of large amounts impetus behind positive economic and social

of resources invested into projects designed change.

under an (almost always incorrect) assumption As such, it is important to recognize that

that computers and an Internet connection while online access is not a determinant of

would be a sufficient investment to bring about participation in the information revolution, it

a meaningful amount of co-presence. Within is a prerequisite. Policymakers should therefore

the contexts of development, resources are always employ the ‘digital divide’ metaphor

always finite; for every funded project many

with caution. Attaining any semblance of

others are left unfunded, and it clearly takes

virtual co-presence in order to achieve eco-

forceful imagery such as the ‘digital divide’,

nomic, social and political goals involves the

‘digital apartheid’ and the ‘global village’ to

circumvention of not only the material divides

allow funds to be spent on ICTs rather than

(i.e. the fact that there is a lack of co-presence

vaccines, water pumps and textbooks.

between people and information), but also the

Nonetheless, as this article has argued,

myriad divides that obstruct communication

more nuance is needed if metaphors such as the

‘digital divide’ are to be continued to be used. within the networks of the Internet. Because

An assumption in much of what is written virtual information and online networks are

about the ‘digital divide’ is that both cyberspace not a floating ‘global village’, ‘digital divides’

and the divide separating the disconnected are consequently contingent on the eco-

from it are distinct, singular and ontic entities. nomic, cultural, political and technological

Bridging a ‘digital divide’ is often thought to be positionalities of each person attempting to

a panacea to issues of development: allowing access the Internet.

people and places to move temporally forwards

on a path of development by being closer in Acknowledgements

relative space to the sites of the information This work benefitted from the support of

revolution. a National Science Foundation Doctoral

This article argues that the trope of a Dissertation Award and the Association of

‘digital divide’ should be pluralized, localized American Geographers Dissertation Grant.

and grounded in more appropriate spatial I also wish to extend thanks to Professor

frameworks. Because of the nature of virtual Matthew Zook, Professor Tom Leinbach,

topologies, there can never be a singular divide. Padraig Carmody and the anonymous re-

There is no singular floating cyberspace, in ferees for their comments and guidance.

Progress in Development Studies 11, 3 (2011) pp. 211–27

224 Time machines and virtual portals

Notes Borgida, E., Sullivan, J. L., Oxendine, A., Jackson,

1. This programme is also known as the Schools and M. S., Riedel, E. and Gangl, A. 2002: Civic culture

Libraries Program of the Universal Service Fund. meets the digital divide: The role of community

2. By the time this article goes to press this figure is likely electronic networks. Journal of Social Issues 58,

to greatly underestimate the number of cities with free 125–41.

wifi access. Brunn, S. and Dodge, M. 2001: Mapping the ‘worlds’

3. See Walton (1999) for a more alarmist take on this of the world wide web. American Behavioral

thesis. Scientist, 44, 1717–39.

4. The premise of the sketch is that ‘if the Internet was Cairncross, F. 1997: The death of distance: How the com-

a real place, it would be disgusting and intolerable’ munications revolution will change our lives. Harvard

(Chapelle, 2004). To prove the point, Chappelle walks Business School Press.

around cyberspace (a fixed and distinct place) which Castells, M. 1996: The rise of the network society. Basil

is populated by other Internet users from around Blackwell.

the world. He is initially looking for a news site, but ——— 1998: The informational city is a dual city: Can it

ultimately gets waylaid by free music, pornographic be reversed? In Schon, D.A., Sanyal, B. and Mitchell,

videos of Paris Hilton and doctors selling male herbal W.J., editors, High technology and low-income

enhancements. communities. MIT Press, 25–42.

5. See Rye (2008) for complementary findings within the ——— 2002: The internet galaxy. Oxford University

contexts of the Indonesian education system. Press.

6. Fisher and Unwin (2002) offer an interesting collec- Chakraborty, J. and Bosman, M. 2005: Measuring

tion of writing on virtual environments. the digital divide in the United States: Race, income,

7. This statistic was obtained from the article ‘How many and personal computer ownership. The Professional

websites are there’ (Anonymous, n.d.) available at Geographer 57, 395–410.

boutell.com. Chappelle, D. 2004: Chappelle’s show: What if the

internet was a real place? USA, Comedy Central.

Cohen, J.E. 2007: Cyberspace as/and space. Columbia

References Law Review 107, 210–56.

Anonymous. n.d: How many websites are there. Compaine, B.M. (editor) 2001: The digital divide: Facing

Available at: http://boutell.com/newfaq/misc/size a crisis or creating a myth?. MIT Press.

ofweb.html, last accessed on 7 April 2011. Couclelis, H. 1996: Editorial: The death of distance.

Ayres, J.M. 1999: From the streets to the internet: Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design

The cyber-diffusion of contention. The Annals of 23, 387–89.

the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Crang, M., Crosbie, T. and Graham, S. 2006: Variable

566, 132–43. geometries of connection: Urban digital divides and

Barber, B.R. 1998: Three scenarios for the future of the uses of information technology. Urban Studies

technology and strong democracy. Political Science 43, 2551–70.

Quarterly 113, 573–89. Dahrendorf, R. (editor) 1977: Scientific-technological

Barlow, J.P. 1996: A Declaration of the Independence revolution: Social aspects. Sage Publications.

of Cyberspace. Online report. Davos, Switzerland. Dann, G.E. and Haddow, N. 2007: Just doing business

Available at: https://projects.eff.org/~barlow/ or doing just business: Google, Microsoft, Yahoo! and

Declaration-Final.html the business of censoring China’s internet. Journal of

Barzilai-Nahon, K. 2006: Gaps and bits: Conceptualiz- Business Ethics 79, 219–34.

ing measurements for digital divide/s. The Information Deibert, R.J. 2003: Black code: Censorship, surveillance,

Society 22, 269–78. and the militarisation of cyberspace. Millenium:

Batty, M. 1997: Virtual geography. Futures 29, Journal of International Studies 32, 501–30.

337–52. Deva, N. 2008: Keynote speech to OLPC 2008 country

Batty, M. and Miller, H.J. 2000: Representing and workshop. Country Workshop. OLPC. Available

visualizing physical, virtual and hybrid information at: http://wiki.laptop.org/go/Country_workshops/

spaces. In Janelle, D.G. and Hodge, D.C., editors, May_2008

Information, place, and cyberspace. Springer, 133–46. Dodge, M. and Kitchin, R. 2001: Atlas of cyberspace.

Benkler, Y. 2006: The wealth of networks. Yale University Addison-Wesley.

Press. Drissel, D. 2006: Internet governance in a multipolar

Berkeley, E.C. 1962: The computer revolution. world: Challenging American hegemony. Cambridge

Doubleday. Review of International Affairs 19, 105–20.

Progress in Development Studies 11, 3 (2011) pp. 211–27

Mark Graham 225

Drucker, P.F. 1969: The age of discontinuity; guidelines to ——— 2010b: Neogeography and the palimpsests of place:

our changing society. Harper and Row. Web 2.0 and the construction of a virtual earth.

Escobar, A. 1995: Encountering development. The making Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 101,

and unmaking of the Third World. Princeton University 422–36.

Press. ——— 2011: Cloud collaboration: Peer-production and

Faris, R., Wang, S. and Palfrey, J. 2008: Censorship the engineering of cyberspace. In Brunn, S., editor,

2.0. Innovations 3, 165–87. Engineering Earth. Springer, 67–83.

Faucon, B. 2001: Getting e-commerce to Africa. Red Graham, M. and Khosravi, S. 2002: Reordering public

Herring. Online magazine. Available at: http://www. and private in Iranian cyberspace: Identity, politics,

redherring.com/Home/9506 and mobilization. Identities: Global Studies in Power

Ferguson, J. 1994: The anti-politics machine: ‘Develop- and Culture 9, 219–46.

ment,’ depoliticization, and bureaucratic power in Graham, S. 1998: The end of geography or the

Lesotho. University of Minnesota Press. explosion of place? Conceptualizing space, place and

——— 1999: Expectations of modernity: Myths and information technology. Progress in Human Geography

meanings of urban life on the Zambian copperbelt. 22, 165–85.

University of California Press. Grasland, L. and Puel, G. 2007: The diffusion of ICT

Fink, C. and Kenny, C.J. 2003: W(h)ither the digital and the notion of the digital divide: Contributions from

divide? The World Bank. Francophone geographers. GeoJournal 68, 1–3.

Fisher, P. and Unwin, D. (editors) 2002: Virtual reality Greenfield, A. 2006: Everyware: The dawning age of

in geography. Taylor and Francis. ubiquitous computing. Peachpit Press.

Flammia, M. and Saunders, C. 2007: Language as Hamade, S.N. 2008: Internet filtering and censorship.

power on the internet. Journal of the American Information Technology: New Generations. IEEE.

Society for Information Science and Technology 58, Hardy, T. 1994: The proper legal regime for ‘cyberspace’.

1899–903. University of Pittsburgh Law Review 55, 993–1055.

G8 2000: Okinawa charter on Global Information Society. Hoffman, D.L. and Novak, T.P. 1998: Bridging the racial

University of Toronto G8 Information Centre. divide on the internet. Science 280, 390–91.

Geissinger, S. 2006: Governor: It’s high time we all go Hofheinz, A. 2005: The internet in the Arab world:

digital. Oakland Tribune. Playground for political liberalization. International

Gibbons, J. and Ruth, S. 2006: Municipal wi-fi: Big wave Politics and Society 3, 78–96.

or wipeout? Internet Computing, IEEE 10, 66–71. Internet World Stats 2009: Internet usage statistics,

Gibson, W. 1984 Neuromancer. HarperCollins.

http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm, last

Gilbert, M.R. and Masucci, M.M. 2005: Research

accessed on 4 April 2011.

directions for information and communication tech-

Jansena, B.J., Spink, A. and Saracevi, T. 2000: Real

nology and society in geography. Geoforum 36,

life, real users, and real needs: A study and analysis

277–9.

of user queries on the web. Information Processing and

Gilbert, M.R., Masucci, M.M., Homoko, C. and

Management 36, 207–27.

Bove, A.A. 2008: Theorizing the digital divide:

Jones, B.O. 1982: Sleepers, wake! Technology and the

Information and communication technology use

future of work. Oxford University Press.

frameworks among poor women using a telemedicine

Kirk, J. 2008: O3b links with Google for fast satellite

system. Geoforum 39, 912–25.

internet capacity. New York Times.

Gorman, S.P. and Malecki, E.J. 2002: Fixed and fluid:

Kirkman, G.S., Cornelius, P.K., Sachs, J.D. and

Stability and change in the geography of the internet.

Schwab, K. 2002: The global information technology

Telecommunications Review 26, 389–413.

Goth, G. 2005: Municipal wireless networks open new report 2001–2002: Readiness for the networked world.

access and old debates. Internet Computing, IEEE Oxford University Press.

9, 8–11. Kitchin, R. 1998: Towards geographies of cyberspace.

Graham, M. 2008a: New silk roads: Promises and perils Progress in Human Geography 22, 385–406.

of the internet in the Thai Silk industry. Department of Kluver, R. and Banerjee, I. 2005: The internet in nine

Geography, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY. Asian nations. Information, Communication, and

——— 2008b: Warped geographies of development: Society 8, 30–46.

The internet and theories of economic development. Kvasny, L. and Keil, M. 2005: The challenges of re-

Geography Compass 2, 771–89. dressing the digital divide: A tale of two US cities.

——— 2010a: Justifying virtual presence in the Thai Information Systems Journal 16, 23–53.

Silk industry: Links between data and discourse. Macavinta, C. 1998: FCC cuts e-rate funding. cnet

Information Technologies and International Development news. Available at: http://news.cnet.com/FCC-cuts-

6, 57–70. E-rate-funding/2100-1023_3-212239.html

Progress in Development Studies 11, 3 (2011) pp. 211–27

226 Time machines and virtual portals

Machlup, F. 1962: The production and distribution of Selwyn, N. 2004: Reconsidering political and popular

knowledge in the United States. Princeton University understandings of the digital divide. New Media &

Press. Society 6, 341–62.

Markoff, J. 2006: Intel programme to bridge divide. Senécal, S. 2005: The effect of the web on archives.

International Herald Tribune. Archivaria 59, 139–52.

Marvin, C. 1988: When old technologies were new: Servon, L.J. 2002: Bridging the digital divide. Blackwell.

Thinking about electric communication in the late Shea, T., Ariguzo, G. and White, S.D. 2007: Putting

nineteenth century. Oxford University Press. the world in the world wide web: The globalisation

Mcluhan, M. 1962: The Gutenberg Galaxy: The making of of the internet. International Journal of Business

typographic man. University of Toronto Press. Information Systems 2, 75–98.

Mcluhan, M. and Fiore, Q. 1967: The medium is the Sheppard, E. 2002: The spaces and times of global-

massage: An inventory of effects. Penguin. ization: Place, scale, networks, and positionality.

Mowlana, H. 1997: Global information and world Economic Geography 78, 307–30.

communication. Sage Publications. Singer, H. 1970: Dualism revisited: A new approach

Norris, P. 2001: Digital divide: Civic engagement, infor- to the problems of the dual society in developing

mation poverty, and the internet worldwide. Cambridge countries. Journal of Development Studies 7, 60–75.

University Press. Standage, T. 1998: The Victorian internet: The remarkable

NTIA 1998: Falling through the net II: New story of the telegraph and the nineteenth century’s online

data on the digital divide. Washington, D.C., pioneers. Weidenfield and Nicolson.

National Telecommunications and Information Stephenson, N. 1992: Snow crash. Penguin.

Administration. Tapia, A., Maitland, C. and Stone, M. 2006: Making

O’Neil, M. 2009: Cyber chiefs: Autonomy and authority

IT work for municipalities: Building municipal wireless

in online tribes. Pluto Press.

networks. Government Information Quarterly 23,

OECD 2008: Digital divide. Paris, Organisation for

359–80.

Economic Co-operation and Development. Avail-

Tesla, N. 1993: The fantastic inventions of Nikola Tesla.

able at: http://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.

Adventures Unlimited Press.

asp?ID=4719

Toffler, A. 1980: The third wave. Bantam.

Porter, M.E., Sachs, J.D., Cornelius, P.K., Mcarthur,

Townsend, A.M. 2001: Network cities and the global

J.W. and Schwab, K. 2002: The global competitiveness

structure of the internet. American Behavioral

report 2001–2002. Oxford University Press.

Scientist 44, 1697–716.

Powell, C.L. 2000: A special message from General Colin

Wachowski, L. and Wachowski, A. 1999: The Matrix.

L. Powell, U.S.A. (ret.). Businessweek. http://www.

businessweek.com/adsections/digital/powell.htm, Warner Bros.

last accessed on 4 April 2011. Walton, A. 1999: Technology Versus African-Americans.

Purcell, F. and Toland, J. 2004: Electronic commerce The Atlantic. Available at: http://www.theatlantic.

for the South Pacific: A review of e-readiness. Elec- com/issues/99jan/aftech.htm

tronic Commerce Research 4, 241–62. Warf, B. 2001: Segueways into cyberspace: Multiple

Recabarren, M., Nussbaum, M. and Levia, C. 2008: geographies of the digital divide. Environment and

Cultural divide and the internet. Computers in Human Planning B: Planning and Design 28, 3–19.

Behavior 24, 2917–26. Warschauer, M. 2003a: Dissecting the ‘digital divide’:

Reporters without Borders 2006: List of the 13 Internet A case study in Egypt. The Information Society 19,

enemies. Available at: http://en.rsf.org/list-of-the-13- 297–304.

internet-enemies-07-11-2006,19603, last accessed ——— 2003b: Technology and social incusion: Rethinking

on 7 April 2011. the digital divide. MIT Press.

Robins, K. 1995: Cyberspace and the world we live Wertheim, M. 1999: The pearly gates of cyberspace: A

in. In Featherstone, M. and Burrows, R., editors, history of space from Dante to the internet. Virago

Cyberpunk/cyberspace/cyberbodies. Sage Publications, Press.

135–56. Withers, C.W.J. and Grout, A. 2006: Authority in

Rostow, W.W. 1960: The stages of economic growth: space?: Creating a web-based digital map archive.

A non-communist manifesto. Cambridge University Archivaria 61, 27–46.

Press. World Bank 2000: The artisan as entrepreneur.

Rye, S.A. 2008: Exploring the gap of the digital divide. WBINews, Summer/Fall, 3. Available at: siteresources.

GeoJournal 71, 171–84. worldbank.org/WBI/Resources/wbinews.pdf

Schwanen, T. and Kwan, M.P. 2008: The internet, Xue, S. 2005: Internet policy and diffusion in China,

mobile phone and space-time constraints. Geoforum Malaysia and Singapore. Journal of Information

39, 1362–77. Science 31, 238–50.

Progress in Development Studies 11, 3 (2011) pp. 211–27

Mark Graham 227

Zook, M. 2000: The economic geography of commercial Zook, M. and Graham, M. 2007a: The creative re-

internet content production in the United States. construction of the internet: Google and the pri-

Environment and Planning A 32, 411–26. vatization of cyberspace and digiplace. Geoforum

——— 2005: The geography of the internet industry: 38, 1322–43.

Venture capital, dot-coms, and local knowledge. ——— 2007b: Mapping digiplace: Geocoded internet

Blackwell. data and the representation of place. Environment

——— 2006: The geographies of the internet. Annual and Planning B: Planning and Design 34, 466–82.

Review of Information Science and Technology 40,

53–78.

Progress in Development Studies 11, 3 (2011) pp. 211–27

You might also like

- Evolution of TechnologyDocument26 pagesEvolution of TechnologycaigoykobiandrewNo ratings yet

- Comparative Analysis - History of Architecture, China, Japan, KoreaDocument14 pagesComparative Analysis - History of Architecture, China, Japan, KoreaMillenia domingoNo ratings yet

- WEBSTER - 2002 - The Information Society RevisitedDocument12 pagesWEBSTER - 2002 - The Information Society RevisitedAna JúliaNo ratings yet

- The Road Not TakenDocument12 pagesThe Road Not TakenAnjanette De LeonNo ratings yet

- Fritz Springmeier InterviewDocument59 pagesFritz Springmeier InterviewCzink Tiberiu100% (4)

- Lecture Five - StudentDocument66 pagesLecture Five - Student코No ratings yet

- Anthropologyof Onlne CommunitiesDocument21 pagesAnthropologyof Onlne CommunitiesjosepipoNo ratings yet

- Sacred Heart Villa School "Maria Schinina": 181 Aguinaldo Highway, Lalaan I, Silang, Cavite (046) 423 - 3403Document7 pagesSacred Heart Villa School "Maria Schinina": 181 Aguinaldo Highway, Lalaan I, Silang, Cavite (046) 423 - 3403katlinajuanaNo ratings yet

- Warschauer 2003Document8 pagesWarschauer 2003José MontoyaNo ratings yet

- 1.1 Globalization and Facets of GlobalizationDocument5 pages1.1 Globalization and Facets of GlobalizationAndrea Lyn Salonga CacayNo ratings yet

- Information, Communication & SocietyDocument30 pagesInformation, Communication & SocietyBerani MatiNo ratings yet

- Seong-Jae Min (2010)Document15 pagesSeong-Jae Min (2010)Luis JaraNo ratings yet

- ICT in DplmcyDocument7 pagesICT in DplmcyFatih ŞengülNo ratings yet

- Global Administration of Information, Communication and Technology - Need For ConvergenceDocument19 pagesGlobal Administration of Information, Communication and Technology - Need For ConvergenceR. U. SinghNo ratings yet

- Coleman - Annual Review of Anthropology & Digital MediaDocument23 pagesColeman - Annual Review of Anthropology & Digital MediaLuke SimulacrumNo ratings yet

- SIPP Module-01-Social-Context-of-ComputingDocument12 pagesSIPP Module-01-Social-Context-of-ComputingCM Soriano TalamayanNo ratings yet

- History of Informatiion System and ICT FaisalDocument10 pagesHistory of Informatiion System and ICT FaisalFaisal YussufNo ratings yet

- E-Topia As Cosmopolis or CitadelDocument29 pagesE-Topia As Cosmopolis or CitadelLaura PereiraNo ratings yet

- Relation Between ICT and DiplomacyDocument7 pagesRelation Between ICT and DiplomacyTony Young100% (1)

- Digital Business Communication in The Global Era ) : Digitalization Culture Based CultureDocument16 pagesDigital Business Communication in The Global Era ) : Digitalization Culture Based CulturejjruttiNo ratings yet

- Drori 2010SItechdividesDocument30 pagesDrori 2010SItechdividesamyouanNo ratings yet

- Graham 1998 The End of Geography or The Explosion of Place? Conceptualizing Space, Place and Information TechnologyDocument22 pagesGraham 1998 The End of Geography or The Explosion of Place? Conceptualizing Space, Place and Information TechnologyJavier PNo ratings yet

- Hand e Sandywell - E-Topia As Cosmopolis or Citadel - Theory Culture and SocietyDocument30 pagesHand e Sandywell - E-Topia As Cosmopolis or Citadel - Theory Culture and Societybeit7No ratings yet

- Digital RevolutionDocument15 pagesDigital RevolutionFlávia PessoaNo ratings yet

- Craig CalhounIT and Public SphereDocument21 pagesCraig CalhounIT and Public Spherejasper_gregoryNo ratings yet

- Digital LiteratureDocument12 pagesDigital LiteratureVinaya BhaskaranNo ratings yet

- Social Epistemology and The Digital DivideDocument6 pagesSocial Epistemology and The Digital DivideJorge ZamogilnyNo ratings yet

- TCW Module #1Document5 pagesTCW Module #1Kai KenzieNo ratings yet

- 1 Digital and Data Fied SpacesDocument14 pages1 Digital and Data Fied SpacesRenn MNo ratings yet

- Cyperspace WarDocument17 pagesCyperspace WarOliver FröhlingNo ratings yet

- Chapter OneDocument17 pagesChapter OneAndrew JamesNo ratings yet

- Latham Information Technology and Social Transformation 2002Document16 pagesLatham Information Technology and Social Transformation 2002Robert LathamNo ratings yet

- ModuleDocument2 pagesModuleGENEROSE BANTAWANNo ratings yet

- Module #1: Definitions and Nature of GlobalizationDocument2 pagesModule #1: Definitions and Nature of GlobalizationGENEROSE BANTAWANNo ratings yet

- ModuleDocument2 pagesModuleGENEROSE BANTAWANNo ratings yet

- Digital AgeDocument20 pagesDigital AgeMhark Jelo Ancheta Chavez0% (1)

- Mass Media Ritzer and DeanDocument2 pagesMass Media Ritzer and DeanHarlika DawnNo ratings yet

- E WasteDocument9 pagesE WasteFrank MartinNo ratings yet

- Mil - Q2 - Module 5Document9 pagesMil - Q2 - Module 5Rea AmparoNo ratings yet

- Globalization and The Internet: Myths and Realities: Trends in Communication July 2003Document18 pagesGlobalization and The Internet: Myths and Realities: Trends in Communication July 2003Srijesh SinghNo ratings yet

- Urban Geography PresentationDocument20 pagesUrban Geography Presentationhelder langaNo ratings yet

- Social Implication of The InternetDocument31 pagesSocial Implication of The InternetlucasNo ratings yet

- Information: Culture and Society in The Digital AgeDocument13 pagesInformation: Culture and Society in The Digital Ageagung yuwonoNo ratings yet

- Web 2.0 and The Culture-Producing PublicDocument16 pagesWeb 2.0 and The Culture-Producing PublicC. Scott Andreas100% (8)

- Metaphors in Critical Internet and Digital Media Studies 2021 Sally Wyatt New Media & SocietuyDocument11 pagesMetaphors in Critical Internet and Digital Media Studies 2021 Sally Wyatt New Media & SocietuyKalynka CruzNo ratings yet

- Unesco - Eolss Sample Chapters: Interactive Multimedia and Digital TechnologiesDocument6 pagesUnesco - Eolss Sample Chapters: Interactive Multimedia and Digital TechnologiesBurhan SivrikayaNo ratings yet

- Running Header: The World As A Global Village 1Document8 pagesRunning Header: The World As A Global Village 1Mikhail LandichoNo ratings yet

- Communication and GlobalizationDocument14 pagesCommunication and GlobalizationJOHN LEE VALDEZNo ratings yet

- Counterhegemonic Discourses and The InternetDocument16 pagesCounterhegemonic Discourses and The InternetCarol CaracolNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Digital AgeDocument19 pagesChapter 2 Digital AgeWinston john GaoiranNo ratings yet

- Information Society An Information Is A Society Where The CreationDocument3 pagesInformation Society An Information Is A Society Where The CreationmisshumakhanNo ratings yet

- Digital DivideDocument17 pagesDigital DivideLaurentiu SterescuNo ratings yet

- Emergent' Media and Public Communication: Understanding The Changing MediascapeDocument15 pagesEmergent' Media and Public Communication: Understanding The Changing MediascapeVasuNo ratings yet

- Pagesfrom VANDIJK9781509534449003Document9 pagesPagesfrom VANDIJK9781509534449003Amina SultanovaNo ratings yet

- Theories of Technological Change and The Internet Phil Gyford 2000-02-21Document4 pagesTheories of Technological Change and The Internet Phil Gyford 2000-02-21Sohan Hasan HasanNo ratings yet

- Globalization The Final VersionDocument74 pagesGlobalization The Final VersionSaif RehmanNo ratings yet

- Digital-Era-From-Mass-Media-Towards-A-Mass-Of-Media - Content File PDFDocument10 pagesDigital-Era-From-Mass-Media-Towards-A-Mass-Of-Media - Content File PDFnhlanhlalekoa05No ratings yet

- Media Technologies, Transmedia Storytelling and CommodificationDocument13 pagesMedia Technologies, Transmedia Storytelling and CommodificationKyle Patrick De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- ComProg TermPaperDocument147 pagesComProg TermPaperJerald BacacaoNo ratings yet

- Digital DivideDocument23 pagesDigital Divideberengmake82No ratings yet

- Art Private Space《Introduction to Mobile Ubiquity in Public and》Document8 pagesArt Private Space《Introduction to Mobile Ubiquity in Public and》bingwan zhangNo ratings yet

- Digital NativeDocument16 pagesDigital Nativen.selwyn86% (7)

- Practicing Sovereignty: Digital Involvement in Times of CrisesFrom EverandPracticing Sovereignty: Digital Involvement in Times of CrisesBianca HerloNo ratings yet

- The Politics of Time and Temporality in Foucault's Theorisation of Resistance: Ruptures, Time-Lags and DecelerationsDocument16 pagesThe Politics of Time and Temporality in Foucault's Theorisation of Resistance: Ruptures, Time-Lags and DecelerationsSimon ODonovanNo ratings yet

- Simon 16Document15 pagesSimon 16Simon ODonovanNo ratings yet

- Simon 3Document18 pagesSimon 3Simon ODonovanNo ratings yet

- Desire As A Theory For Migration StudiesDocument17 pagesDesire As A Theory For Migration StudiesSimon ODonovanNo ratings yet

- Blommaert Spotti VD Aa 2017 Complexitymobilitymigration Canagarajah Handbookof Lgand Migration RoutledgeDocument18 pagesBlommaert Spotti VD Aa 2017 Complexitymobilitymigration Canagarajah Handbookof Lgand Migration RoutledgeSimon ODonovanNo ratings yet

- Evija - Lotus Cars Official WebsiteDocument5 pagesEvija - Lotus Cars Official WebsiteluyuanNo ratings yet

- Summer ReadingDocument1 pageSummer ReadingDonna GurleyNo ratings yet

- WN Ce1905 enDocument3 pagesWN Ce1905 enanuagarwal anuNo ratings yet

- Bacc Form 02Document2 pagesBacc Form 02Jeanpaul PorrasNo ratings yet

- Present Status of Advertising Industry in IndiaDocument25 pagesPresent Status of Advertising Industry in IndiaMeenal Kapoor100% (1)

- ASA 105: Coastal Cruising Curriculum: Prerequisites: NoneDocument3 pagesASA 105: Coastal Cruising Curriculum: Prerequisites: NoneWengerNo ratings yet

- Nec Exhibition BrochureDocument4 pagesNec Exhibition BrochurejppullepuNo ratings yet

- Latihan Soal Dan Evaluasi Materi ComplimentDocument6 pagesLatihan Soal Dan Evaluasi Materi ComplimentAvildaAfrinAmmaraNo ratings yet

- Reading 2 - Julien Bourrelle - TranscriptDocument4 pagesReading 2 - Julien Bourrelle - TranscriptEmely BuenavistaNo ratings yet