Professional Documents

Culture Documents

39AdminHowison NZCooperativehandbook

Uploaded by

joyelisadhty0906Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

39AdminHowison NZCooperativehandbook

Uploaded by

joyelisadhty0906Copyright:

Available Formats

Lazarus and Oloroso – Administering Cooperative Education Programs

36 Administering Cooperative Education Programs

FREYDA C. LAZARUS

Montclair State University, Upper Montclair, NJ, USA

HELEN C. OLOROSO

Robert R. McCormick School of Engineering & Applied Science, Northwestern University,

Evanston, IL, USA

SHARLEEN HOWISON

Otago Polytechnic, Dunedin, NZ

Over the past century, cooperative education (co-op) programs have developed in

institutions of higher education throughout the world. In the UK and Australasia, work

placements and sandwich courses described the alternation of work and study, and the term

internship was used in some academic institutions in the USA and Europe. Work-based

learning and work-integrated learning have recently emerged as new ways to expand or

describe the cooperative education concept. Co-op programs have developed to support

every type of curriculum, from engineering, technology, the social and natural sciences, to

the arts and humanities. Although co-op programs are diverse and the descriptions and

terms to define them vary, they all share the goal of guiding students through the process of

integrating academics with learning in the workplace. The person responsible for managing

this educational process is the co-op administrator.

This chapter will provide insights into the challenges of co-op program

administration, a discussion of co-op literature concerning administration; an exploration of

the academic workplace as a context for learning administration; and an inventory of the

functions, skills, and competencies needed to succeed as a co-op administrator.

Recommendations are made for an effective human resource development plan that will

move a new practitioner from novice to professional, as well as research needed to advance

the profession. Co-op administrators can be faculty or professional staff hired for the

purpose of administering a program, as compared with Boud and Solomon’s (2001)

perspective that “partner organizations want full-time academics involved, not sessional

staff hired for the purpose” (p. 218). Co-op administrators in some countries such as New

Zealand and Australia also work as academic lecturers, where their work role is split

between administration and lecturing.

Having administrators who are also academics, can be positive, as the emphasis

on effective learning as part of the co-op experience is integrated into the administration of

the program. With the increase in technology available, co-op administrators are in a

position to exchange dialogue with students and employers through Skype. Where the

administrators are charged with organizing seminars Elluminate and Skype are effective

tools for this to occur. The use of learning platforms such as Moodle and Blackboard have

also encouraged the development of more online discussion boards for students, supervisors

and the administrators encouraging more regular integrated feedback by all parties.

(Howison, and Finger, 2010)

CHALLENGES OF CO-OP PROGRAM ADMINISTRATION

Co-op programs exist at the interface between the world of academia and the larger

International Handbook for Cooperative Education 180

Lazarus and Oloroso – Administering Cooperative Education Programs

community. As a result, the administration of co-op programs calls for individuals who

possess a unique set of skills and insights equipping them to draw together constituencies

that do not normally coexist peacefully. Two overarching challenges face administrators.

The first is that co-op administrators must be able to bridge the vast cultural differences

between their academic institutions and organizations that employ their students. The

second is the conflict that often exists between the role of the co-op program and the mission

of the academic institution. The challenge is to administer a co-op program that is both

stimulating in the work placement sense and also fulfills the needs of the institution in

reference to the academic requirements. Engaging students in more online engagement

through discussion boards, online reflective journals and technology such as Elluminate and

Skype help to strengthen the link between the institution and the workplace. Administrators

who can effectively utilize all the technology available today are extremely valuable to any

co-op program. Being able to successfully master these technologies will enable the

administrator to work more effectively and efficiently to meet the requirements of their

position.

Co-op administrators must understand the natural differences that exist between the

purpose of academia and the purpose of enterprise, and then translate that understanding into

the ability to work with the differences and find common ground in the shared purpose of

developing students into professionals. Students themselves play a different role in each

environment, but the eventual outcome for them should be the integration of learning at

work and in the classroom. Institutions of higher education exist to preserve fundamental

knowledge and to develop new knowledge in each discipline they represent. Students are

both participants in, and beneficiaries of, these goals; they are the end itself. Co-op

administrators must understand and advance this process.

Employing organizations, on the other hand, serve a very different purpose. While

the service mission of non-profit organizations and the governance mission of public sector

organizations help foster cultures similar to that of academic institutions, there are still

fundamental differences between them. Colleges and universities are there to serve

students; employing organizations are there to get work done. Students are important to

employers insofar as they can deliver results. Private sector organizations have the

additional pressure to be profitable; for them, students must add value or they will not be

considered. For all employers, cooperative education is a means of accomplishing strategic

goals of talent acquisition and development. Students, therefore, are a means to an end, and

not the end itself.

Also not surprising is the common experience of co-op professionals that the

dichotomy and contradictions between academia and the workplace exist within the walls of

the institution as well. Therefore the second challenge confronting the co-op administrator

is to align the program with the mission and goals of the institution. With one foot in the

world of the employer, co-op administrators must be able to plant the other foot in the world

of academia, where the student is the end and not the means to the mission. Faculty are key

in the accomplishment of this mission. However, they frequently see teaching as the only

legitimate way to guarantee that students will learn the fundamentals of their discipline, free

from bias that comes from learning by serving the vested interests of a company.

Theoretical learning is often viewed as pure learning, as opposed to learning as a by-product

of a corporate agenda.

The co-op administrator, therefore, must develop and guide the co-op program in

such a way as to bridge the talent development aspects of the academic institution and

employers talent acquisition priorities. The success of the program rests upon the

administrator’s ability to assess the changing environment of the academic institution, the

academic leadership’s expectations for the program, and clear understanding of the skills

International Handbook for Cooperative Education 181

Lazarus and Oloroso – Administering Cooperative Education Programs

needed to succeed in the position.

LITERATURE ON PROGRAM ADMINISTRATION

Within co-op literature there is an enormous gap in information about program

administration and the responsibilities of the administrator. Early in the expansion of

cooperative education programs in the USA, Knowles et al. (1972) included a chapter on

general administration with consideration of a few basic concepts that help insure success:

support of upper-level administrators (president, deans, and heads of departments), support

of faculty, the availability of jobs and assignments, requirement for a degree, and public

relations. For the next three decades, when exploring issues of program administration, co-

op practitioners debated from two major perspectives: the appropriate organizational

structure for the most effective program, and the reporting relationships for the co-op

program within the institution.

Boud and Solomon (2001) have determined, based on their knowledge of work-

based learning in Australian universities, that “the most common approach to date has been

to locate it [co-op administration] as part of a program structure within existing schools or

faculties, as at Anglia Poloytechnic University, or within its own faculty structure, as has

occurred at Middlesex Universities” (p. 217). In a similar way, the experiential education

field has explored the virtues of different organizational reporting relationships, with the

debate centering on the merits of reporting to academic affairs or student affairs (Kendall,

Duley, Little, Permaul, & Rubin, 1986).

Some administrators have been faculty members; some come from the ranks of

student affairs; and others from the business world (Heinemann & Wilson, 1995). Often,

the reporting structure around the co-op program reinforces the focus of the administrator.

Further to this, an administrator can be drawn from either the faculty, with experience in the

academic affairs, or from the student affairs division, or from the business community.

The cooperative education literature and research on program administration is

limited and is primarily based on the perspectives of the author. Exceptions are the studies

conducted by Stull (1981) and Lazarus (1991) concerning the ways in which co-op directors

learn their job, and general research about higher education administration. It is clear that

there is a serious void in the professional literature about co-op program administration.

Jenny Onyx of the Faculty of Business at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS)

draws a similar conclusion in her chapter Implementing Work-based Learning for the First

Time (Onyx, 2001), concluding that “the lessons that can be learnt from our experience

suggest that we have not recognized the importance of adequate staff development of both

university academics and workplace supervisors” (p. 139).

As argued by Harper, O'Donoghue, Oliver, and Lockyer (2001), there is a need for

academics and administrators to design courses based upon educational principles of

effective learning with reference to ICT. Thus it is essential that the technology adopted in

administering the co-op courses must be user friendly, contain all the necessary

functionalities and encourage the students to engage with it.

Of the various theories that explain technology style acceptance, the Technology

Acceptance Model (TAM) appears to be the most widely accepted theory among

information systems research for studying users’ system acceptance behaviour.

Furthermore, in the model conceptualised by Davis et al. (1989), perceived ease of use

directly affects perceived usefulness, and affects computer technology adoption (Pituch &

Lee, 2004). Davis has also suggested that external factors may be important determinants of

the usefulness constructs of TAM. These include internet experiences, computer anxiety,

International Handbook for Cooperative Education 182

Lazarus and Oloroso – Administering Cooperative Education Programs

computer self-efficacy, and affect. Pituch & Lee (2004) conclude that students’ prior

technical skills in using the internet may affect intention to use E-learning. When

administrators are involved in decisions associated with the preferred computer programs to

adopt in the implementation of co-op, it is essential that they consider this issue.

Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) Davis et al. 1989)

Roffe (2002) argues that purchasers of E-learning platforms, including managers and

administrators often want particular forms of information on performance. One of the most

promising aspects of E-learning consists of the opportunity to activate students and shift

more of the responsibility for the learning outcome to the learner. This can be done, on the

one hand, by integrating communication tools in order to foster collaborative learning and

discussion about problems and task-solving with other administrators as well as among

peers. Administrators of co-op could therefore utilise the E-Learning program to assist with

delivery and implementation of co-op while the students are completing their placement.

Furthermore, connectivism recognises the need to be flexible to meet the needs of the

individual learners. E-Learning, and the digital age that we are in, necessitate the need for

effective online programs that encourage, stimulate and motivate the student (Siemens,

2008). The functions of the program that the students engage with must include options

that allow discussion, feedback and a sense of being part of a larger community. The

administrators of co-op must consider this when implementing new E-Learning programs.

Virtual learning communities are also being established as a means of managing workforce

placement, through delivery modes that are not time- or place-dependent (Arbaugh &

Duray, 2002). In order to successfully participate in virtual learning communities, however,

participants must invest time and energy in a range of virtual discussions and other online

collaborative activities. Administrators should consider this E-Learning concept, as an

effective strategy to assist in the co-ordination of the co-op students (Jones & McCann,

2005).

THE CONTEXT AND THE CONTENT FOR LEARNING PROGRAM

ADMINISTRATION

The academic workplace provides a unique context for learning how to administer a

program. Higher education relies on co-op administrators learning their administrative

responsibilities by “doing” and then reflecting on the experience in order to produce some

level of knowledge that will guide future actions. The institution normally does not provide

professional development activities, but relies on the individual locating resources and

International Handbook for Cooperative Education 183

Lazarus and Oloroso – Administering Cooperative Education Programs

colleagues to foster his or her own development. In fact, individual administrators must

come to the realization that they have a need for learning and decide what and how they will

learn what they need to know (Lazarus, 1991).

Marsick and Watkins (1990), when discussing informal and incidental learning,

suggest that there is no formula that guarantees workplace learning; however proactivity,

critical reflectivity, and creativity can enhance it. They go on to state:

Proactivity refers to readiness to take initiative in learning. Critical reflectivity is

related to the surfacing and critiquing of tacit, taken for granted assumptions and

beliefs that need to be examined in order for people to reframe problems.

Creativity refers to the capacity of people to see a situation from many points of

view, and use new perspectives and insights to break out of preconceived patterns

that inhibit learning (p. 8).

In contrast, the worlds of business and government provide professional development in a

more rational and routine manner by sponsoring training programs and planned instructional

meetings. Visionary organizations recognize the importance of formal training, as well as

informal and incidental learning that occurs out of the structure of planned activities.

According to McDade (1987), higher education follows a “pattern of natural selection with

little planning or preparation by the individual or the organization for its leadership of the

future” (p. 1).

Co-op administrators are often not consciously aware of what they are learning;

they frequently overlook opportunities for professional development that occur

simultaneously with on-going, job-related responsibilities. However, administrators who

proactively seek out on-campus, informal learning opportunities, such as serving on a task

force or participating in organizational events, can enhance their understanding of the art of

administration. This understanding is further enhanced through reflection and discussion or,

most especially, by participating in formal training programs through either professional

organizations or courses (Lazarus, 1991, 1992).

Further to this the importance of networking and attending national and

international cooperative education conferences cannot be undervalued. It is at such

conferences that administrators are able to share common ideas and knowledge and learn

from other administrators in the same position, adding to best practice models. As stated by

Randall (2010, p.1) “Conferences offer the chance to join forces with others in pursuit of a

common goal…..for this reason alone, the conference experience can be extremely

beneficial--and that is before one takes into account the access to fresh research, and new

resources available”.

ADMINISTRATOR FUNCTIONS, SKILLS AND COMPETENCIES

To date the only significant research to establish a curriculum supporting the development of

co-op administrators is the work of Timothy Nolan. Conducting an occupational analysis in

the 1980s, the published outcome of Nolan’s (1988) work was A Professional Inventory for

Administrators: Functions, Skills and Competencies which details the tasks, skills, and

competencies required to execute the responsibilities of a co-op administrator. Once the

tasks, skills, and competencies were identified to create a DACUM (Developing a

Curriculum) and SCID (Steps, Competencies, Information, and Decisions), further analysis

was undertaken to uncover the accepted practices within a job cluster, along with the skills

and competencies needed to perform the job This inventory for co-op administrators

International Handbook for Cooperative Education 184

Lazarus and Oloroso – Administering Cooperative Education Programs

contains 13 job functions with each function containing between 6 and 15 tasks. It also

provides an in-depth description of the overall responsibilities of the position and provides

the “curriculum” for self-directed learning.

With respect to student development, the activities of a administrator parallel the

sequence of events that transpire during a student’s participation in the program. These

include, but are not limited to, assisting students with career planning, teaching career

planning courses and evaluating students for placement. Following the finalization of

placement plans, the administrator continues the student development process by helping

students to see the links between academic work and work experience, monitoring placed

students, and evaluating and assessing student learning at work.

The administrator’s responsibility for employer development includes developing

new work sites and maintaining the continuity of those sites. This involves outreach to

those employers who can provide meaningful, challenging opportunities for the general

student population, as well as assisting an individual student identify particular employers

who can offer an experience that will be unique to that student. It also means anticipating a

pending vacancy with a co-op employer and proactively assisting the employer with the

process of identifying candidates to fill their co-op position. It is essential that the student

and employer are matched correctly to meet the needs of the academic curriculum and also

the career path of the student involved.

Finally, the administrator is responsible for program management. This means

developing and maintaining links among the faculty, as well as promoting and marketing the

program to students and employers. Administrators must also evaluate the program

periodically, participate in strategic planning, as well as advance their own professional

development in order to keep the program and their own skills current with the changing

needs of the students, the curriculum, and the workplace. Further to this they may be

required to update the learning platforms such as Blackboard or Moodle to ensure that

relevant course information and announcements are dispersed electronically to the students,

academics and themselves. Student participation in online discussions through these

learning platforms may also be monitored for evaluation by the administrators. These

functions, then, constitute the inventory for administrators.

Functional Learning

Learning to develop and manage program resources; create and maintain information

management systems; collect, analyze, and disseminate program outcomes to all involved

parties – the institution, students, employers, and the community.

International Handbook for Cooperative Education 185

Lazarus and Oloroso – Administering Cooperative Education Programs

FIGURE 1

Director DACUM

International Handbook for Cooperative Education 186

Lazarus and Oloroso – Administering Cooperative Education Programs

Behavioral Learning

Behavioral learning is learning to manage the full range of relationships that exist among

participants in the co-op program (students, faculty, employers and site supervisors) and

between the program participants and the academic institution. The activities associated

with this category of learning include such responsibilities as promoting and marketing the

program to all constituencies; staffing the program; developing and managing employer

relations; and facilitating student learning.

Organizational Learning

Organizational learning is learning that involves the integration of the co-op program with

the institution as a whole. It refers to all functions that actualize the institution’s mission

and goals through the program’s objectives and activities. The DACUM addresses the

following elements of organizational learning: implementing strategic management within

the co-op program; building and maintaining institutional support for the program; and

participating in and contributing to the development of the institution’s strategic initiatives.

Professional Learning

Professional learning is learning to pursue professional development activities for the field

of cooperative education and work-integrated learning. This includes learning about, and

adhering to, the standards for professional conduct as a co-op professional, as well as

developing a desire for continued learning about the field.

Technical Learning

Technical learning involves the development of skills related to the use of website

development, digital media, social networking strategies, electronic reputation management

tools, web-based video, webinars, electronic communications platforms and other Web 2.0

applications. At the current time, this would include blogs, wikis, video sharing, personal

branding, mashups and folksonomies. These are all web applications that facilitate

participatory information sharing, interoperability and user-centered design. On the

hardware side, the use of smart phones, tablet devices and electronic readers are

proliferating, and point the way towards smarter and more agile handheld devices.

However, the world of electronic media and communications is changing so rapidly that the

role of the administrator is to continuously learn not only what is new, but devise ways to

integrate these tools into the structure and strategies of the co-op program, while at the same

time, maintaining quality content. Ensuring that the administrators are trained and skilled at

implementing these new technologies is essential.

APPLICATIONS FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF PROGRAM ADMINISTRATORS

The information found in the administrator and director inventories can serve as the

curriculum for a training program, and be used to explain the responsibilities of the positions

to senior administrators. The inventory for a director can be used to construct a job

description for a newly-established program, or it can be used when an out-going

administrator is not available to help select a successor. It offers the institution a

comprehensive view of the position in order to recruit the best candidates. The functions

International Handbook for Cooperative Education 187

Lazarus and Oloroso – Administering Cooperative Education Programs

described in both inventories are necessary for every type of program, and the skills they

outline provide criteria for recruiting the most qualified candidates.

Frequently, individuals comprising the interview committee hiring a co-op

administrator come from a cross-section of the institution. They do not necessarily perform

any functions directly related to the co-op program, but their units may impinge on the

program in some ancillary fashion. In order for them to conduct a productive and beneficial

interview, they need a framework for questions that address the skills and competencies the

job requires. Each function outlined in the DACUM can be made into quantifiable or

observable objectives with corresponding activities. Taken as a whole, they provide the

framework for the administrator’s role within the co-op program and with internal and

external constituencies. This is especially useful when individuals in the institution who

have no direct experience with cooperative education programs conduct the performance

review.

INSIGHTS FOR THE FUTURE

Cooperative education programs all over the world face the challenge of selecting,

developing, and supporting administrators who must possess a rare combination of skills and

talents. By balancing the often-conflicting missions of academia and business they create a

synergy between theoretical and applied learning, through their own efforts and by leading

staff and faculty in that process. They learn their own jobs through a variety of informal

learning methods, often unknowingly, and frequently in isolation. They are the very

embodiment of the pedagogical strategies that they seek to implement: learning by doing

and, ultimately, learning from experience.

Based on the absence of information and limited research on co-op program administration,

it is clear that co-op practitioners, whether faculty or staff, rely on their professional

organizations for formal training and developmental activities. The leaders of the

professional community socialize their members to the norms and values of the profession

(Lazarus, 1991). With the increase in E-Learning technologies available to co-op

administrators, it is important that these individuals are given specific training and support

to implement that technology effectively. Building online communities of learning with

students and the academic supervisors of the co-op program, is one way of integrating the

co-op placement with the academic work required. It also increases the flexibility of the

learning experience whilst encouraging more integrated reflective learning for the students

(Howison, and Finger, 2010).

With this clear mandate, state, regional, national, and international

organizations have a renewed responsibility to provide programs and resources that will

move the administrators from novice to professional. As cooperative education programs

evolve in the next hundred years, they will no doubt reflect the changing needs of both

academia and the workplace. Through skilled administrators the programs will continue to

bridge these two worlds, resulting in the ongoing refinement of the learning process as well

as the skills, competencies, and insights needed to succeed as a program administrator.

International Handbook for Cooperative Education 188

Lazarus and Oloroso – Administering Cooperative Education Programs

REFERENCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arbaugh, J., & Duray, R. (2002). Technological and structural characteristics, learner learning and

satisfaction with web-based courses. Journal of Management Learning, 33 (3), pp. 331-47.

Argyris, C., & Schön, D. (1974). Theory in practice: Increasing professional effectiveness. San

Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Austin, A.E. (1984a). The work experience of university and college administrators. Washington, DC:

American Association of University Administrators.

Austin, A.E. (1984b, March). Work orientation of university mid-level administrators: Commitment to

work role, institution, and career. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Association

for the Study of Higher Education. Chicago, Il.

Boud, D., Keogh, R., & Walker, D. (1985). Reflection: Turning experience into learning. London:

Kogan Page.

Boud, D., & Solomon, N. (Eds.). (2001). Work-based learning: A new higher education? London:

Open University Press.

Bookfield, S. (1986). Understanding and facilitating adult learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Brown, S.J., & Wilson, J.W. (1979). National assessment of cooperative education training. Boston:

Cooperative Education Research Center, Northeastern University.

Clark, B.R. (1984). The higher education system: Academic organization in cross-national

perspective. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Davis, F. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information

technology, MIS Quarterly, 13.

Eble, K.E. (1988). The art of administration. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Harper, B., O'Donoghue, J., Oliver, R., & Lockyer, L. (2001). New designs for web-based learning

environments. In C. Montgomerie, & J. Viteli (Eds.), Proceedings of ED-MEDIA 2001, World

Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia & Telecommunications (pp.674-675).

Tampere, Finland: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education.

Heinemann H., & Wilson, J.H. (1995). Developing a taxonomy of institutional sponsored work

experience. Journal of Cooperative Education, 30(1), 46-55.

Howison, S., Finger, G., (2010) Enhancing Cooperative Education Placement through the Use of

Learning Management System Functionalities: A Case Study of the Bachelor of Applied

Management Program, Asia Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education, 11(2), pp.47-56

Jarvis, P. (1987a). Adult learning in the social context. London: Croom Helm.

Jarvis, P. (1987b). Meaningful and meaningless experience: Towards an analysis of learning from life.

Adult Education, 37(3), 164-172.

Jones, S., & McCann, J. (2005). Virtual learning environments for time-stressed and peripatetic

managers, Journal of Workplace Learning, 17 (5), pp. 359-69.

Kendall, J., Duley, J., Little, T., Permaul, P., & Rubin, S. (1986). Establishing administrative structures

that fit the goals of experiential education. In J.C. Kendall (Ed.), Strengthening experiential

education within your institution: A sourcebook by the National Society for Internships and

Experiential Education (pp. 81-104). Raleigh, NC: National Society for Experiential

Education.

Kennedy, W.B. (1990). Integrating personal and social ideologies. In J. Mezirow, & Associates.

Fostering critical reflection in adulthood: A guide to transformative and emancipatory

learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Knowles, A., & Associates (1972). Handbook of cooperative education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development.

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Kram, K. (1985). Mentoring at work: Developmental relationships in organizational life. Glenview,

IL: Scott Foresman.

Kuh, G., & Whitt, E. (1988). The invisible tapestry: Culture in American colleges and universities.

(Report No. 1). Washington, DC: Association for the Study of Higher Education.

International Handbook for Cooperative Education 189

Lazarus and Oloroso – Administering Cooperative Education Programs

Lazarus, F. (1991). The synergy of workplace learning. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. New York:

Columbia University Teachers College.

Lazarus, F. (1992). Learning in the academic workplace: Perspectives of cooperative education

directors. Journal of Cooperative Education, 28(1), 67-76.

Marsick V.J. (Ed.). (1987). Learning in the workplace: Theory and practice. London: Croom Helm.

Marsick, V.J. (1988). Learning in the workplace: The case for reflectivity and critical reflectivity.

Adult Education Quarterly, 38(4), 187-198.

Marsick, V.J. (1990a). Altering the paradigm for theory building and research in human resource

development. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 1(1), 5-23.

Marsick, V.J. (1990b). Action learning and reflection in the workplace. In J. Mezirow, & Associates

(Eds.), Fostering critical reflection in adulthood: A guide to transformative and

emancipatory learning (pp. 23-46). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Marsick, V.J. & Watkins, K.E. (1990). Informal and incidental learning: A challenge to human

resource developers. London: Routledge.

McDade, S. (1987). Higher education leadership: Enhancing skills through professional development

programs. (Report No. 5). Washington, DC: Association for the Study of Higher Education.

Mezirow, J. (1977). Perspective transformation. Studies in Adult Education, 9(2), 153-154.

Mezirow, J. (1978). Perspective transformation. Adult Education, 28(2), 100-110.

Mezirow, J. (1981). A critical theory of adult learning and education. Adult Education, 32(1), 3-24.

Mezirow, J. (1985). A critical theory of self-directed learning. In S. Brookfield (Ed.), Self-directed

learning: From theory to practice. New directions for continuing education. San Francisco:

Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J. (1990). How critical reflection triggers transformative learning. In J. Mezirow, &

Associates (Eds.), Fostering Critical reflection in adulthood: A guide to transformative and

emancipatory learning (pp. 23-46). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Moore, K.M., & Sagaria, M.D. (1982). Differential job change and stability among academic

administrators. Journal of Higher Education, 53, 501-513.

Nolan, T. (1988). Task analysis of the cooperative education administrator. In S. Sovilla, B. LeMaster,

& C Stemple (Eds.), Proceedings of the Twenty-fifth Anniversary Conference of the

Cooperative Education Association (pp. 27-33). Cincinnati, OH: Cooperative Education

Association.

Ott, J.S. (1989). The organizational culture perspective. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Onyx, J. (2001). Implementing work-based learning for the first time. In D. Boud & N. Solomon

(Eds.), Work-based learning: A new higher education? (pp. 126-140). London: Open

University Press.

Pituch, K. A. and Lee, Yao-Kuci. (2004). The influence of system characteristics on E-Learning,

Retrieved August 01st from http://www.qou.edu/homePage/arabic/researchProgram/E-

LearningResearchs/

Randall, M. (2010) Adventures on the Conference Circuit. Teaching Music Journal. 17 (4), pp. 38-41.

Roffe, I. (2002) E-learning: Engagement, enhancement and execution. Quality Assurance in

Education Journal. 10, (1), pp. 40-50.

Ryder, K.G., Wilson, J.W., & Associates (Eds.). (1987). Cooperative education in a new era. San

Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Sagaria, M.A. (1986, February). Head counting and hill climbing, and beyond: The status and future

directions for research on mid-level administrators careers. Paper presented at the annual

meeting of the Association for the Study of Higher Education. San Antonio, CA.

Schön, D.A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic

Books

Schön, D.A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner: Toward a new design for teaching and

learning in the professions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Siemens, G. (2004). Connectivism: A Learning Theory for the Digital Age. Retrieved December 12,

2008 from http://elearnspace.org/Articles/connectivism.htm.

Siemens, G. (2008). New structures and spaces of learning: The systemic impact of connective

knowledge, connectivism, and networked learning. Retrieved October 10 from

http://elearnspace.org/Articles/systemic_impact.htm.

International Handbook for Cooperative Education 190

Lazarus and Oloroso – Administering Cooperative Education Programs

Stull W.A. (1981). Leadership styles of cooperative education directors, organizations characteristics

and elements of program success in colleges and universities in the United States. Logan,

UT. US Department of Education (Grant #GOO8005091), September 1981, Research

Monograph, # 4.

Tough, A.M. (1967). Learning without a teacher: A study of tasks and assistance. The adult’s learning

projects: Education resource series (Report No. 3). Toronto, ON: Ontario Institute for Studies

in Education.

Tough, A.M. (1979). The adult’s learning projects: A fresh approach to theory and practice in adult

learning (2nd ed.). Toronto, ON: Ontario Institute for Studies in Education.

Weick, K.E. (1976). Educational organizations as loosely coupled systems. Administrative Science

Quarterly, 21, 1-18.

Wilson, J.W. (1987). Contemporary trends in the United States. In K. Ryder & J.W. Wilson (Eds.).

Cooperative education in a new era (pp. 30-44). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

International Handbook for Cooperative Education 191

You might also like

- Pygmalion EffectDocument11 pagesPygmalion EffectKarandeep Singh100% (1)

- Policy Guidelines On Awards and Recognition For The K To 12 Basic Education ProgramDocument21 pagesPolicy Guidelines On Awards and Recognition For The K To 12 Basic Education ProgramChajotsuczyzai Reivaj ZenMartNo ratings yet

- Suma Parahakaran ICELDocument10 pagesSuma Parahakaran ICELDr Suma ParahakaranNo ratings yet

- Delhi Case Study Final Exec SummaryDocument4 pagesDelhi Case Study Final Exec SummaryFD OriaNo ratings yet

- 02 TQMRSynergiesHEIDocument12 pages02 TQMRSynergiesHEIDinkisaNo ratings yet

- Bringing The Community To The School and Placing The School in The Community: New Practices and Challenges in The Teaching of Graduate StudentsDocument6 pagesBringing The Community To The School and Placing The School in The Community: New Practices and Challenges in The Teaching of Graduate Studentsfernando santosNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Transformative Curriculum Design EDIT2Document50 pagesChapter 2 Transformative Curriculum Design EDIT2Noey TabangcuraNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Educational LeadershipDocument8 pagesThesis On Educational Leadershipbseb81xq100% (2)

- Curriculum in DevelopmentDocument5 pagesCurriculum in DevelopmentEndang GolisNo ratings yet

- Computer Supported Collaborative LearningDocument2 pagesComputer Supported Collaborative LearningshahidNo ratings yet

- F3F The Idea of Instructional Leadership in Engineerinfg EducationDocument4 pagesF3F The Idea of Instructional Leadership in Engineerinfg EducationMohd Shafie Mt SaidNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Academic and Student Affairs Collaboration and Student Success 2.institutionalization of Student ServicesDocument11 pagesThe Relationship Between Academic and Student Affairs Collaboration and Student Success 2.institutionalization of Student ServicesCrisanta AgooNo ratings yet

- Royal Roads Teaching and Learning ModelDocument40 pagesRoyal Roads Teaching and Learning ModelGeorge VeletsianosNo ratings yet

- AM The Increasing Importance of Curriculum DesignDocument15 pagesAM The Increasing Importance of Curriculum DesignariefNo ratings yet

- Final - Transformative Experiences For Students Concept PaperDocument6 pagesFinal - Transformative Experiences For Students Concept Papermarkpalolan17No ratings yet

- Article On Assessment PDFDocument17 pagesArticle On Assessment PDFtariqghayyur2No ratings yet

- TEACHING COMPETENCIES FOR THE 21ST CENTURY RRLDocument5 pagesTEACHING COMPETENCIES FOR THE 21ST CENTURY RRLDENNIS RAMIREZNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Internationalization of Higher EducationDocument6 pagesLiterature Review Internationalization of Higher EducationxvszcorifNo ratings yet

- Conlon 1997Document11 pagesConlon 1997AngelooNo ratings yet

- Chapter IiDocument36 pagesChapter IiMichael Casil MillanesNo ratings yet

- 2nd Activity Dpa 318 Doc - CatapangDocument5 pages2nd Activity Dpa 318 Doc - CatapangCriselda Cabangon DavidNo ratings yet

- Literature Review in Mobile Technologies and Learning NaismithDocument7 pagesLiterature Review in Mobile Technologies and Learning Naismithc5j2ksrgNo ratings yet

- 216-Management of Services and Affairs: Alma Villa R. Pascual Presenter-Maed StudentDocument82 pages216-Management of Services and Affairs: Alma Villa R. Pascual Presenter-Maed StudentCrisanta AgooNo ratings yet

- Cohort-Based Doctoral Programs: What We Have Learned Over The Last 18 YearsDocument20 pagesCohort-Based Doctoral Programs: What We Have Learned Over The Last 18 YearsAnonymous qAegy6GNo ratings yet

- Who or What Contributes To Student Satisfaction in Different Blended Learning Modalities?Document18 pagesWho or What Contributes To Student Satisfaction in Different Blended Learning Modalities?colegiulNo ratings yet

- Researches On Curriculum Development (Written Report) - PANZUELODocument4 pagesResearches On Curriculum Development (Written Report) - PANZUELOPanzuelo, Kristene Kaye B.No ratings yet

- Session 7 Habib KhanDocument11 pagesSession 7 Habib Khanu0000962No ratings yet

- Writing Sample - Olshefski 2018Document11 pagesWriting Sample - Olshefski 2018api-397858890No ratings yet

- Dave Burnapp, Rob Farmer, Sam Reese, Anthony Stepniak: Case StudiesDocument8 pagesDave Burnapp, Rob Farmer, Sam Reese, Anthony Stepniak: Case StudiesI Wayan RedhanaNo ratings yet

- Teachers' Social Capital As A Resource For Curriculum Development: Lessons Learnt in The Implementation of A Child-Friendly Schools ProgrammeDocument8 pagesTeachers' Social Capital As A Resource For Curriculum Development: Lessons Learnt in The Implementation of A Child-Friendly Schools ProgrammeHuda AlassafNo ratings yet

- 3 Articles Summary 900 WDocument2 pages3 Articles Summary 900 WTraining for BeginnersNo ratings yet

- From Planning To Action-14-24Document11 pagesFrom Planning To Action-14-24Ahmad Abdun SalamNo ratings yet

- Repurposing Social Networking Technologies To Encourage Preservice Teacher Collaboration in Online Communities: A Mixed Methods Study Michael MoroneyDocument20 pagesRepurposing Social Networking Technologies To Encourage Preservice Teacher Collaboration in Online Communities: A Mixed Methods Study Michael MoroneyMike MoroneyNo ratings yet

- CurriculumFramework ATIAH enDocument17 pagesCurriculumFramework ATIAH enkausalyia appannanNo ratings yet

- Impact of Educational Leadership and Organisational Management On Further StudiesDocument5 pagesImpact of Educational Leadership and Organisational Management On Further StudiesKanza NajamNo ratings yet

- Power Distance Literature ReviewDocument6 pagesPower Distance Literature Reviewakjnbowgf100% (1)

- Participants of Curriculum Development - RevisedDocument5 pagesParticipants of Curriculum Development - RevisedRajeswariPerumalNo ratings yet

- 8 Learning Communities and Support - v3 - en-USDocument9 pages8 Learning Communities and Support - v3 - en-USRafelly113No ratings yet

- Curriculum DevelopmentDocument10 pagesCurriculum DevelopmentKenneth Myro GarciaNo ratings yet

- Reflective Analysis (Profed2)Document4 pagesReflective Analysis (Profed2)flairemoon05No ratings yet

- A Learning and Teaching Model Using Project-Based Learning (PBL) On The Web To Promote Cooperative LearningDocument9 pagesA Learning and Teaching Model Using Project-Based Learning (PBL) On The Web To Promote Cooperative LearningNenden Nur AeniNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Gaps of Bachelor's Business Education in Universities of Bangladesh: An AnalysisDocument8 pagesCurriculum Gaps of Bachelor's Business Education in Universities of Bangladesh: An AnalysisBashir Ali Sidi JuhaNo ratings yet

- Educ 205Document4 pagesEduc 205Eden Grace Benenoso ArabesNo ratings yet

- Developinga Modelfor Stakeholder Engagement Managementfor SHSImmersion ProgramDocument97 pagesDevelopinga Modelfor Stakeholder Engagement Managementfor SHSImmersion Programmarco24medurandaNo ratings yet

- Online LearningDocument11 pagesOnline LearningSteven WaruwuNo ratings yet

- Learning Culture As A Guiding Concept For SustainaDocument14 pagesLearning Culture As A Guiding Concept For SustainaAndrea MeloNo ratings yet

- Using Facebook Groups To Support Teachers' Professional DevelopmentDocument22 pagesUsing Facebook Groups To Support Teachers' Professional DevelopmentLilmal SihamNo ratings yet

- Research Papers Learning Management SystemDocument6 pagesResearch Papers Learning Management Systemqqcxbtbnd100% (1)

- Professional Learning Networks: A Conceptual Model and Research OpportunitiesDocument19 pagesProfessional Learning Networks: A Conceptual Model and Research OpportunitiesLilmal SihamNo ratings yet

- ComleadDocument11 pagesComleadHenniejones MacasNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER II REVIEW OF LITERATURE IntroducDocument46 pagesCHAPTER II REVIEW OF LITERATURE IntroducRiniel100% (1)

- Reading Team BuildingDocument3 pagesReading Team BuildingAidaNo ratings yet

- A Theoretical Framework For Effective Online LearningDocument12 pagesA Theoretical Framework For Effective Online LearningSiti NazleenNo ratings yet

- Educational Management, Educational Administration and Educational LeadershipDocument5 pagesEducational Management, Educational Administration and Educational LeadershipAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1096751611000510 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S1096751611000510 MainRaluca Andreea PetcuNo ratings yet

- Different Things From School To School or Place To Place, Including Professional LearningDocument27 pagesDifferent Things From School To School or Place To Place, Including Professional LearningMICHAEL STEPHEN GRACIASNo ratings yet

- 5 Assumptons OJDLA PDFDocument7 pages5 Assumptons OJDLA PDFdaveasuNo ratings yet

- Dias Fonseca T 49638 AAMDocument17 pagesDias Fonseca T 49638 AAMRaven Portia Ivon Gmelijah MejiaNo ratings yet

- Ect 212 Curriculum ImplementationDocument81 pagesEct 212 Curriculum Implementationaroridouglas880No ratings yet

- Edu Tech Best Practices WPDocument12 pagesEdu Tech Best Practices WPapi-262223114No ratings yet

- A Definitive White Paper: Systemic Educational Reform (The Recommended Course of Action for Practitioners of Teaching and Learning)From EverandA Definitive White Paper: Systemic Educational Reform (The Recommended Course of Action for Practitioners of Teaching and Learning)No ratings yet

- I Plan in MAPEH 1Document3 pagesI Plan in MAPEH 1Ella Rose OcheaNo ratings yet

- PMPcourse OutlineDocument5 pagesPMPcourse OutlineArsalan MushtaqNo ratings yet

- Mechanics of Materials Labs With SolidWorks Simulation 2014 by Huei-Huang LeeDocument3 pagesMechanics of Materials Labs With SolidWorks Simulation 2014 by Huei-Huang LeezidaaanNo ratings yet

- Mitch LPDocument14 pagesMitch LPMishie Bercilla100% (1)

- The New Somatic Symptom Disorder in DSM-5 Risks Mislabeling Many People As Mentally IllDocument2 pagesThe New Somatic Symptom Disorder in DSM-5 Risks Mislabeling Many People As Mentally IllfortisestveritasNo ratings yet

- Social-Emotional Outcomes For Children With SLI: A Newsletter Dedicated To Speech & Language in School-Age ChildrenDocument5 pagesSocial-Emotional Outcomes For Children With SLI: A Newsletter Dedicated To Speech & Language in School-Age ChildrenPaul AsturbiarisNo ratings yet

- Workplace Ostracism ScaleDocument19 pagesWorkplace Ostracism ScaleShaheena SanaNo ratings yet

- SET DPP - 3: Let'S Crack It!Document2 pagesSET DPP - 3: Let'S Crack It!DtyuijNo ratings yet

- Endoscopic Ear Surgery Course. 4th Edition: Barcelona, April 27, 2022Document1 pageEndoscopic Ear Surgery Course. 4th Edition: Barcelona, April 27, 2022Luana Maria GherasieNo ratings yet

- HRLinc Sample Behavioural Interview Questions 1 73Document5 pagesHRLinc Sample Behavioural Interview Questions 1 73Thushara JayawickramaNo ratings yet

- Modal Analysis of Cracked Cantilever Beam by Finite Element SimulationDocument8 pagesModal Analysis of Cracked Cantilever Beam by Finite Element SimulationMohammad Talha AamirNo ratings yet

- Pak Study 301 MCQDocument19 pagesPak Study 301 MCQfatima shahNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement: The Central Idea of A Multiple-Paragraph CompositionDocument15 pagesThesis Statement: The Central Idea of A Multiple-Paragraph CompositionKd123No ratings yet

- Lesson 11 and 12 ActivittiesDocument32 pagesLesson 11 and 12 ActivittiesHazel HazeNo ratings yet

- Difference Between Male and Female LanguageDocument3 pagesDifference Between Male and Female LanguageAyesha HameedNo ratings yet

- Micro Teaching ON Question BankDocument40 pagesMicro Teaching ON Question BankSumi SajiNo ratings yet

- CRLA - EoSY - G1 - S.Y 22-23Document17 pagesCRLA - EoSY - G1 - S.Y 22-23DONNA MAE CAMACHO100% (1)

- AAMUSTED Student HandbookDocument110 pagesAAMUSTED Student Handbookakabiru831No ratings yet

- UBANAN-ANDRO-Thesis For DecDocument49 pagesUBANAN-ANDRO-Thesis For Decgladen shelley billonesNo ratings yet

- Grade 6 Summative Test 4TH QuarterDocument3 pagesGrade 6 Summative Test 4TH QuarterPatrixia Miclat100% (1)

- Self EsteemDocument2 pagesSelf EsteemNisansala Vidana PathiranaNo ratings yet

- Preparing For Transformational Change: A Framework For Assessing Organisational Change ReadinessDocument15 pagesPreparing For Transformational Change: A Framework For Assessing Organisational Change ReadinessSourabh MishraNo ratings yet

- Education System in PolandDocument2 pagesEducation System in Polandapi-466148385No ratings yet

- 02 Embedded Design Life CycleDocument19 pages02 Embedded Design Life CyclePAUL SATHIYANNo ratings yet

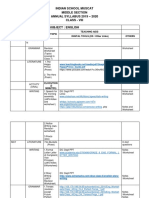

- Indian School Muscat Middle Section Annual Syllabus 2019 - 2020 Class - Viii Subject: EnglishDocument8 pagesIndian School Muscat Middle Section Annual Syllabus 2019 - 2020 Class - Viii Subject: EnglishJoseph MaryNo ratings yet

- Professional Ethics in Higher Education: Dr. Radhika KapurDocument14 pagesProfessional Ethics in Higher Education: Dr. Radhika KapurHamdi AbdirhmaanNo ratings yet

- Revised Syllabus Law 211 Bsa ObliconDocument13 pagesRevised Syllabus Law 211 Bsa ObliconCherielyn BeguiaNo ratings yet

- Teaching ResumeDocument4 pagesTeaching Resumeapi-278722846No ratings yet