Professional Documents

Culture Documents

11.vol 0005www - Iiste.org Call - For - Paper - No 1-2 - Pp. 65-81

Uploaded by

Alexander DeckerOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

11.vol 0005www - Iiste.org Call - For - Paper - No 1-2 - Pp. 65-81

Uploaded by

Alexander DeckerCopyright:

Available Formats

Issues in Social and Environmental Accounting Vol. 5, No.

1/2 December 2011 Pp 65-81

Companies Ethical Commitment An Analysis Of The Rhetoric In CSR Reports

Caroline D. Ditlev-Simonsen 1*)

Department of Public Governance Norwegian School of Management, Norway

Sren Wenstp2

Department of Strategy and Management Norwegian School of Economics and Business Administration Norway

Abstract This paper investigates rhetoric applied in 80 Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) reports in 2005. A taxonomy of five distinct rhetorical strategies for describing the purpose of CSR is applied; Agency (profit), Benefit (collective welfare), Compliance (laws and contracts), Duty (duties), and Ethos (virtue). The findings reveal that very different rhetoric is applied. Ethos is the most common ethical perspective expressed in the reports, Benefit and Agency are on second and third place. Specific patterns of ethical reasoning appear to be common, while other possible reasoning strategies are rare. The most prevalent pattern of ethical reasoning is to link Agency and Benefit perspectives, claiming that Benefit is done for the sake of Agency. These findings constitute a new approach in CSR research. Keywords: Corporate social responsibility (CSR), reporting, ethics, rhetoric

Caroline Dale Ditlev-Simonsen, PhD (Corresponding author), is a researcher at BI-Norwegian School of Management and has international and comprehensive business and organizational experience in the area of corporate social responsibility, including Project Manager, World Industry Council for the Environment, New York; Executive Officer, Norwegian Pollution Control Authority; Advisor, Kvrner ASA and Vice President, Head of Community Contact, Storebrand ASA, one of Norways largest companies. From 2002-2008 she was a board member of WWF-Norway (World Wide Fund for Nature). She is also an Associate Director at the BI Centre for Corporate Responsibility www.bi.no/ccr. 2 Sren Wenstp (co-author) js a research fellow at the Norwegian School of Economics and Business Administration. His main areas of interest are business ethics and moral philosophy applied to the business context. He has previously worked at the Center of Corporate Citizenship (CCC) at the Norwegian School of Management (BI), and with initiatives in the non-profit humanitarian aid sector (the JetAid Foundation). Sren Wenstp has lectured in business ethics and the Norwegian School of Economics and Business Administration (NHH) and at the Norwegian School of Management (BI). *) We would like to thank Professor Fred Wenstp, Norwegian School of Management, for inspiration and advice in the process of this article.

66

C. Ditlev-Simonsen, S. Wenstp / Issues in Social and Environmental Accounting 1/2 (2011) 65-81

1. Introduction Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is ostensibly about doing good. But the question is good for whom? Good for the company, the owners, the managers, the employees, the customers, the environment, the local community, the world? The possibilities are many, and most CSR reports give reasons for why a particular company engages in CSR. Since CSR is about doing good, these reasons may be seen as ethical commitments. In this paper, we explore patterns of such arguments. We are not concerned with the real impacts of CSR, only what arguments are given; the study is therefore a study of rhetoric. The number and volume of CSR1 reports have increased tremendously over the last 15 years (Corporate Register, 2008; KPMG, 2008). Contrary to mandatory financial reporting which are guided by a regulatory framework, CSR reports are voluntary and without a fixed and regulated framework. Corporations are therefore free to choose the content as well as the manner in which they are presented. A substantial volume of research has been conducted to get an understanding of the background for and effect of CSR disclosures. A common method is quantitative discourse analysis with observation of such variables as the frequency of CSR related sentences, number of papers addressing CSR, number of

1

words disclosed or lines disclosed (M. C. Branco & Rodrigues, 2007). Such studies, however, do not capture underlying attitudes to CSR nor the specific ethical commitments statements express. Therefore, there is a significant lack of research that analyses practices of language through which managers and other societal actors come to describe, explain or otherwise account for environmental and social problems (Joutsenvirta, 2009). The ethical attitude behind a companys CSR is presumably a determining element for its CSR activities, and a relevant place to look for the expression of such attitudes is the rhetoric applied in CSR reports. Few studies have however been conducted in this area (Ihlen, 2010) and this study will respond to this gap through investigating the moral commitments reflected in 80 CSR reports. In the study Ethical Guidelines for Compiling Corporate Social Reports, a framework for developing CSR reports is suggested (Kaptein, 2007). In this paper, however, we go a step behind (or ahead) and look at what ethical perspectives corporations actually apply in their CSR report rhetoric. Whereas previous studies have investigated the quality of voluntary disclosures (Brammer & Pavelin, 2008), the reason behind why corporations use corporate social disclosures (Clarke & Gibson-Sweet, 1999), factors influencing social responsibility disclosures (M. Branco & Rodrigues, 2008), how companies best can communicate their CSR initiatives (Morsing, Schultz, & Nielsen, 2008), this study focuses on the ethical commitment reflected in the CSR goal rhetoric. In their study analyzing sustainability values, Livesey and Kearins com-

Many different appellations of corporate voluntary activities exist. In this article we will use the term Corporate Social Responsibility to account for voluntary engagement by corporation described in their non-financial reports. Some corporations studied have named these reports Environmental-, Sustainability-, HSE- etc., - and in some cases these reports are part of the annual report. Common for all these reports are that they are voluntary, and to simplify the wording in the article we are using one term, CSR

C. Ditlev-Simonsen, S. Wenstp / Issues in Social and Environmental Accounting 1/2 (2011) 65-81

67

pare the corporate discourse expressed in the two corporations, Body Shop Int. and Royal Dutch/Shell Group (Livesey & Kearins, 2002). Whereas they discuss to which extent the values expressed in the reports can contribute to improved social and environmental behaviour in the corporate decision making, we will not investigate the impact of the values expressed in the reports. Our study will solely identify, compare and categorize the values expressed. The contributions of this article are theoretical as well as empirical: we develop a taxonomy of rhetorical strategies that reflect the kinds of ethical arguments we find in the business ethics literature, and review 80 CSR reports and document the ethical arguments actually used. Our taxonomy has two main features. The first is a system of rhetorical strategies; the second is a structure that links them. This is necessary because different strategies can be connected within a system of moral reasoning; one reason for CSR may for instance be an instrument for another. The rest of the paper is organized as follows: The next section gives an overview of research in the CSR field and the role of rhetoric and ethics in such reports. Thereafter the method and data is presented. In the section after, different examples of quotes that exemplify ethical commitments are presented. The findings are then discussed. The final section concludes with theoretical and practical implications of the study as well as suggestions for further research.

2. CSR Reporting, Rhetoric and Ethics a review CSR Reports Non-financial reporting has gone through a comprehensive growth. The number and scope has grown exponentially, from less than 30 in 1992 to over 3000 in 2008. The focus in these reports has changed to. Whereas the majority of reports in the 90ties were concerned with environmental issues, the content has gradually become more encompassing. Now it is more common to extend the reports to address corporate responsibility and sustainability issues (www.CorporateRegister.com). Institutional theory is suggested as a theoretical approach to study CSR issues (Campbell, 2007; Galaskiewicz, 1997). The three pillars of institutions, regulative, normative and cultural-cognitive, provide a basis for legitimacy (Scott, 2008). Legitimacy is one of the leading perspectives for explaining why corporations engage in CSR reporting. Legitimacy theory is based on the idea that in order to continue operating successfully, corporations must act within the bounds of what society identifies as socially acceptable behaviour (O'Donovan, 2002). Several studies support the argument that it is socially expected of companies to issue CSR reports and apply the CSR terminology. However, legitimacy theory does not deal with the moral attitude of CSR reports.

68

C. Ditlev-Simonsen, S. Wenstp / Issues in Social and Environmental Accounting 1/2 (2011) 65-81

Ethics rhetoric in CSR reporting There is no generally accepted moral reason for why corporations ought to pursue social engagement (Hummels, 2004), but most corporations do state a purpose for their CSR activities that is based on ethical principles. Rhetoric, the art of using language to communicate effectively, is applied to convey these messages. Corporations presumptively apply ethics rhetoric in their CSR reports to achieve certain communication goals, such as for example enhancing legitimacy. Our aim is not to speculate around the set of motives behind ethics rhetoric, but rather to make theory-based assessments of what this rhetoric actually communicates, as interpreted by a reasonably informed audience. Few studies have been conducted of this kind. One of them, which analyzed the CSR reports of the worlds largest 20 companies, identified five rhetoric strategies: (1) We improve the world, (2) We clean up in our own house, (3) Others like us, (4) We are part of society, (5) We like you (Ihlen, 2010)2. Some of these strategies are close to those in our study, but whereas Ihlen looks at what companies say we look at the justification or ethical commitment entailed by what they say. Another closely related vein of research has studied corporate value statements (Wenstp & Myrmel, 2006). That paper argues that value statements would be clearer and at the same time more suitable for strategic decision-making purposes if they were structured according to the classical ethical categories. Our research makes an explicit connection between such CSR

2 Translation of 1. Vi forbedrer verden, 2. Vi rydder opp i eget hus!, 3. Andre liker oss!, 4. Vi er med!, 5 Vi liker deg!

value statements and specific ethical frameworks. The taxonomy of ethics rhetoric In their book Business Ethics, Crane and Matten present four central ethical theories and show how they relate to business: Egoism, Utilitarianism, Ethics of duties, and Rights and justice (Crane & Matten, 2004). The first two are forms of consequentialism, whereas the latter represent non-consequentialism. The consequentialist approaches focus on outcomes, whereas the nonconsequentialist approaches place a primacy on specific principles above a concern for outcome. For example, for a company that considers whether to downsize, a consequentialist theory will look at the effects of the downsizing, either more narrowly (egoism) or more widely (utilitarianism). A nonconsequentialist perspective will pick up one among a number of principles and hold that the decision should be made according to how well it complies with the guiding principle. A rights perspective, for instance, will look at downsizing in terms of what rights the people involved have, and how the decision meets or infringes on these rights. There is more than one way to cut a cake, but Crane and Mattens suggestion exemplifies a widely recognized way of dissecting ethical theory. With one notable exception, this framework is also relatively complete. It leaves out virtue ethics and it seems clear to us that this perspective needs to be included. Not only does virtue ethics have a rich intellectual history (which runs back to antiquity), but it is also a distinct perspective with a high standing in contemporary

C. Ditlev-Simonsen, S. Wenstp / Issues in Social and Environmental Accounting 1/2 (2011) 65-81

69

moral philosophy and business ethics alike. The taxonomy we propose, then, consists of five categories. To capture the essence of what they stand for we have chosen to denote them as follows: A (Agency), B (Benefit), C (Contract), D (Duty), and E (Ethos). We also have a sixth category, F (Fail), for companies that fail to communicate an ethical perspective. A, B, C, D, E can be thought of as denoting different ethical commitments (and F lack of commitment).

By making ethical statements, companies perform certain acts, what might appropriately be called speech acts(Austin, 1962). These ethical speech acts imply commitment to types of ethical theory. While we give examples of these theories, it is important to note that the theoretical commitments do not pertain to specific theories but specific kinds of theories (unless a specific reference is made in the CSR reports), and that the examples we give are theories of the same type. For example, Singer (1993) gives a specific expression of consequentialism. By invoking

Table 1 Overview over the ethical categories applied

A Agency Business perspective (what is important?) Profit, Agents, Shareholders B Benefit Collective welfare, Stakeholders C- Contract Contractual agreements, Rules, regulations, Laws D Duty Duty, legitimacy, Natural moral laws E Ethos Virtues, Excellence, Power F Fail Nothing in particular

Associated business theories

Adam Smith (1991) Milton Friedman (1970) Ayn Rand (1970)

Archie J. Bahm (1983), Edward R. Freeman (1984) Jeremy Bentham (2000), Peter Singer (1993) Consequentialism

Donaldson & Dunfee (1999)

DiMaggio & Powell (1983) Norman Bowie (1999) Immanuel Kant (1998)

Associated ethical theories

Jean-Jacques Rosseau (1984) John Rawls (1971) David Gauthier (1986) Nonconsequentialism

Chester I. Barnard (1938), Solomon (1992) Aristotle (2004) Alasdair MacIntyre (1984) Nonconsequentialism

Type

Consequentialism

Nonconsequentialism

Singer as an exponent of consequentialsm, we do not imply that companies expressing a consequentialist stance adopt Singers specific version of it. Our labels correspond to the question: What is of moral importance? In the CSR reports, the strength and clarity

with which the implicit commitments are expressed varies. We address neither the clarity, strength, nor the plausibility of the various theoretical commitments. The aim in this study is to classify the different commitments, and the way they feature in patterns of moral reasoning. To start with, we will look at how the

70

C. Ditlev-Simonsen, S. Wenstp / Issues in Social and Environmental Accounting 1/2 (2011) 65-81

different commitments relate to ethical theories. Table 1 provides an overview over the taxonomy and related ethics and business theories. The rest of the section will describe them more closely. Agency: Agency is linked to the ethical perspective of egoism. Some dislike even suggesting that egoism is an ethical perspective; many see egoism as lack of ethics. But, as a distinct perspective, it deserves a place in any taxonomy of ethical commitments that claims to be reasonably complete. Moreover, the relevance of egoism to business ethics is especially relevant, given the fact that egoism features as a behavioral assumption in several key theories of business and economics. In our framework, agency is somewhat wider than egoism as conventionally conceived. Normally, egoism is restricted to the individual level, but in business egoism would be linked to the profit motive. Our notion of agency therefore amounts to an extension of egoism. For instance, in a typical business organization the motives of its owners, by extension, also become the motives of the agents employed to work on their behalf (when their motives are suitably aligned). Given that this type of arrangement is so prevalent in business, we find the label agency more apt than egoism. We take agency to express the concerns that are internal to the firm; including owners, managers, as well as employees. Benefit: The benefit perspective is linked to benevolent consequentialism and utilitarianism. It expresses a commitment to further the interests, welfare, or well-being of stakeholders outside the boundaries of the firm; the boundary of the firm is the cut-off point between the agency perspective and the benefit per-

spective. For corporations, the scope of these perspectives vary between the expression of more closely held preoccupations with the interests of customers or clients, to a wider concern for social good and the environment. Contract: The contract perspective is linked to contractualism. Contractualist theories, in turn, contain theories of rights and justice. The notions of rights and justices on this perspective are understood in terms of some idea of a contract. This contract can be thought of as either actual or ideal; where the moral validity of the contract is sutured by an actual (between actual contracting parties) or idealized agreement (between suitably rational and well informed contractors). For corporations, this simply implies following existing rules and regulations and not take on responsibilities beyond this. Duty: Duty relates to duty ethics, and caters the idea of one or more absolute duties. Typical duty-based perspectives include the classical perspective of Immanuel Kant, and the contemporary perspective of Norman Bowie. Applied to corporations, the duty concept has been referred to as Trevio and Nelsons New York Times test(Crane & Matten, 2004). To a certain degree this attitude is in line with legitimacy theory. There are certain things corporations should engage in, independent of laws and regulations. For example, most companies donated to organizations helping the victims of the Tsunami in 2004, even though this was not mandatory nor linked to profit. As most companies did so, it could be perceived as embarrassing for a company if it was revealed that it had skipped this token of empathy.

C. Ditlev-Simonsen, S. Wenstp / Issues in Social and Environmental Accounting 1/2 (2011) 65-81

71

Ethos: The ethos perspectives express a commitment to virtues (or vices to avoid) how one would want to be (as opposed to look at what to do). The related normative perspective is virtue ethics. The ethos category contains two rather different sort of ideals; on the one hand we have the more business-related ideals (such as the ideal of being excellent or a leader), on the other hand there are the more overtly moral type of ideals (such as to be fair or being trustworthy). The former is an agency-related ethos, while the latter is a benefit-related ethos. Ethos needs to be separated out as a distinct rhetoric strategy because it communicates a distinct sort of moral commitment. For corporations, ethos can be viewed as having aspirations of being the best - in search of excellence. Fail: In these cases there is no traceable theoretical commitment to CSR in corporate reports. Patterns of moral reasoning The commitments discussed above can be expressed as rhetorical strategies in all sorts of combinations. While it is of interest to look at isolated expressions of commitment, it is also interesting to assess relations between them. By analyzing paragraphs and sentences, we can identify distinct patterns of moral reasoning. For instance, one company may emphasize a commitment to benefit (B), but also state that it does so in order to meet a commitment to agency (A). The end motive here is agency (A), and the pattern of moral reasoning is that (B) is an instrument for (A). Another company may express the reverse, that agency (A) is necessary in order to meet commitments to a benefit (B). In principle, all sorts of combinations are possible. The

paper will identify the most prevalent combinations in our material.

3. Data collection and Methodology The data presented in this study reflects a review of CSR attitudes reflected in annual and non-financial reports from 80 different companies in 2005. Selection of companies This article originated from a consultancy task conducted for 12 large Norwegian corporations. Management representatives in these corporations selected between five and 10 corporations which CSR activities they wanted to know more about. According to the contract, the clients should receive a two page executive summary of CSR coverage in financial and non-financial reports of the corporations selected for investigation. Some of the corporations selected were already part of the Top Brands 2005 list, the list of the Worlds Most Respected Companies (WMRC) and WMRC-CSR3, and some additional corporations from these lists were also included. The list of companies investigated is available in attachment 1. One of the authors of this article was responsible for conducting the consultancy task. A format for this two-page executive summary, or fact sheet, was developed. One section of the fact sheet documented how corporations presented their CSR efforts, with focus on CSR

3 Top Brands 2004, a joint venture between BusinessWeek and Interbrand, The Worlds Most Respected Companies survey are published in a special supplement of the Financial Times and a joint venture between PricewaterhouseCoopers and FT and been conducted on a global basis. WMRC-CSR is the companies that best demonstrate their commitment to corporate social responsibility according to NGOs

72

C. Ditlev-Simonsen, S. Wenstp / Issues in Social and Environmental Accounting 1/2 (2011) 65-81

Table 2 Overview Over Corporations Studied

Characteristic Turnover Number of employees Location / country of HQ Information 70 mill $ (NextGenTel) to 285 200 mill $ (Wal Mart) 150 (Vollvik/Chess) to 1 600 000 (Wal Mart) 1 Autralia, 1 Austria, 1 Belgium, 2 Canada, 4 Denmark, 4 Finland, 2 France, 5 Germany, 1 Italy, 2 Japan, 21 Norway, 10 Sweden, 2 Switzerland, 1 The Netherlands, 8 UK, 12 USA, 1 UK/Netherlands, 1 Sweden/UK, 1 Denmark/UK 28 support UNGC, 22 member of WBCSD, 33 on DJSI and 34 on FTSE4Good list. 32 sectors

UNGC, WBCSD, DJSI and FTSE4Good Sector

challenges their overall CSR purpose. Compiling these fact sheets, it became evident that the rhetoric in the reports reflected very different ethical commitment, and this deserved further investigation. The focus is on CSR reports from 2004/05, which is a limbo period in CSR reporting as the Global Reporting Initiative had not yet taken off, i.e. no firm reporting framework existed, making the reports provide a good picture of truly voluntary reporting. The companies vary with regards to size, sector, turnover, number of employees and location (Table 2). The size of the reports also varies widely, ranging from a few pages in the annual report to separate CSR reports of about one hundred pages (for example Alcan, Body Shop and Daimler Chrysler). Whereas most studies investigate corporations of similar sizes, sector, and country, this study looks at very different corporations. This has its advantages and

disadvantages. The advantage is that we will have large varieties in cases. The disadvantage is the lack of homogeneity that makes it less possible to generalize based on the findings.

Selection of quotes and interpretation The CSR reports were read by one of the authors and passages that most succinctly reflect ethical commitment were identified and quoted. Although CSR reports may run up to hundred pages, it was usually possible to find a place where goals and purposes are highlighted, thus revealing an ethical commitment. Several quotes from individual companies are included in this paper to give the reader an account of what they look like. The quotes were then assigned to ethical categories as well as to patterns of moral reasoning. This was done independently by three persons the two authors and a third person, who then came together to compare notes. The participants generally agreed, and subsequent discussions

C. Ditlev-Simonsen, S. Wenstp / Issues in Social and Environmental Accounting 1/2 (2011) 65-81

73

landed the remaining ambiguities. The full set of quotes can be made available. It is important to bear in mind that ours is a study of rhetoric. An exercise in comparing what companies report about themselves and what media say about the same company, illustrates the discrepancy between self reporting and others perception or reality (M. C. Branco & Rodrigues, 2007). However, we are not concerned with reality, only rhetoric strategies as revealed by CSR reports. 4. Findings Here follows a summary of interpretation and classification of quotes regarding ethical commitments in the CSR reports of 80 companies. When an ethical category appears as an instrument for another, we have an instance of moral reasoning. Patterns of moral reason are also identified and classified. Agency (A) Ten companies argued that their CSR activities were directly related to or driven by a profit motive. The following quotes exemplify an agency attitude: RWEs declared mission is to contribute to establishing a global trend that economizes resources, guarantees secure, high-quality supplies, and creates wealth. This is the very philosophy that determines RWEs strategy for sustainability. (RWE, 2003) For RWE wealth (profit) is presented as a key driver for CSR activities. CSR engagement is thus an agent for increasing the wealth of the shareholders or owners.

Some CSR reports argued to the effect that a benefit (B) motive was instrumental to an agency (A) motive that is a combination of moral reasoning. Jotun A/S will enhance long term competitiveness and financial performance through responsible approach, attitude and actions regarding Safety, Health and Environment (Jotun, 2005) By acting responsibly, we can contribute to sustainable development and build a strong foundation for economic growth. (Nokia, 2004) Jotun, one of the world's leading manufacturers of paints, coatings and powder coatings, argues that the responsibility approach leads to improved financial performance. This is along the lines of Nokia, which argues that responsibility (collective welfare) build a foundation for economic growth. In both statements it is clear that financial interests are the main objective. Responsibility is presented as a secondary aim undertaken to meet the first. A few companies argued that by fulfilling their duty (D), profit (A) could be achieved. The core responsibility of the Sony Group to society is to pursue enhancement of corporate value through innovation and sound business practices. (Sony, 2005) Innovation and sound business practices are presented as corporate activities that contribute to corporate value (A). Meanwhile the responsibility element is expressed as something that the

74

C. Ditlev-Simonsen, S. Wenstp / Issues in Social and Environmental Accounting 1/2 (2011) 65-81

company simply has; a duty (D), in relation to society. Benefit (B) Thirteen companies focused on benefit (B) as the key argument for CSR. The ambition of DnB NOR is to promote sustainable development through responsible business operations giving priority to environmental, ethical and social considerations (DnBNor, 2004) The interests of stakeholders, such as the environment and society feature centrally in DnB NORs (a Norwegian based bank) statements about CSR. The benefit (B) perspective given here is broad, and unambiguously stated due to the use of the word priority. Some companies combine benefit (B) and agency (A) moral rhetoric; doing good for society and making money at the same time. Nikes overall corporate strategy focuses on delivering value to shareholders, consumers, suppliers, employees and the community. (Nike, 2004) Nike indicates that it wants to combine value to shareholders and customers, which are more in the corporate direct self interest (A) to also encompass the community, i.e. society outside the company (B). The aims in this statement are placed side-by-side, without one being subordinated the other. No specific pattern of moral reasoning is expressed. Two companies argued that through increase profitability (A) it could further the aim of taking care of society outside the company (B).

Peab builds for the future. We wish to be the leading and most attractive construction and civil engineering company in Sweden. We wish that what we build to create added value for our customers, suppliers and ourselves, and to contribute to the sustainable development of society. Good financial profitability is a precondition of our success. (Peab, 2004) Contract (C) Only five companies argued that to fulfil laws and regulations was their main reason for CSR. One example however, is Systembolaget, the Swedish monopoly for selling wine and liqueur beverages. But the most important part of our work is actually not what we do, but what we do not do. We do not sell to just anyone. Not to anyone less than 20 years of age. Not to anyone who is obviously under the influence of alcohol or other intoxicant. And not to anyone whom we suspect will sell the goods on. (Systembolaget, 2004) This quote expresses a distinct contract (C) perspective: Their key basis for CSR is to comply with what they are (legally) obligated to do: Not sell to anyone less than 20 years of age. This expression of social responsibilities is shaped by the laws of society, and hence the central feature of the message they send is that their corporate social responsibly consists in abiding by the social contract of society as represented by laws and regulations. Only one company argued that a contract perspective (C) was instrumentally important for profit (A). Furthermore,

C. Ditlev-Simonsen, S. Wenstp / Issues in Social and Environmental Accounting 1/2 (2011) 65-81

75

none of the moral attitudes (A-E) was presented as leading to (C). This is not surprising, as for example neither profit nor duty is formally required (C) in the business world. Duty (D) Seven companies used a rhetoric of duty (D) as a basis for their CSR activities. Carrefours progressive approach is built on 3 major commitments: quality and safety, respect for the environment, and economic and social responsibility.(Carrefour, 2004) By using the word commitment Carrefour expresses their ethics in terms of a duty (D) perspective. One gets the impression that there simply are certain commitments, and that they should be heeded qua commitments. Ethos (E) Ethos (E) as a basis for CSR activities was by far the most common rhetoric approach. For 26 of the 80 companies, the rhetoric was built on the ethos (E) basis of ethics. Often the ethos was aligned with ideals such as being the best, trustworthiness, or excellence. Some of the perspectives propounded more business-like ideals, whereas others were more overtly ethical. An example of a business-related (or agency-related) ethos (E) is given by the Italian oil and gas firm, Eni. Sustainability aims to strike a balance between expectations for growth to the value of the business, environmental protection and social issues. An approach to sustainability based on adoption of all possible instruments to ad-

dress this issue rigorous management systems, targeted strategic projects, research and innovation and dialogue with stakeholders is a prerequisite to maintaining positions of leadership within the energy sector. (Eni, 2004) Enis aim to be a leader is an ideal and serves to define an ethos. To strike the balance is furthermore a type of art, along the lines of identifying where ethos is located what is the right thing to do. Pfizer, an American pharmaceutical company, expresses an ethos (E) perspective that is overtly ethics-related (or benefit-related). To consider our next generations perception fits closely with virtue ethics, since it invokes a clear ethical ideal (being one ones children would think well of) which the company professes to strive to stick by. Corporate Citizenship at Pfizer means considering our plans and actions against one profound question: What will our children think?.(Pfizer) Three companies described how fulfilling duty (D) would lead to achieving ethos (E), and the US pharmaceuticals company Johnson & Johnson was one of them: Our Credo articulates the values that drive our business strategy of sustainable, long-term growth and leadership. In essence, it is our sustainable strategy: our Companys commitment to meet our responsibilities to people, communities and the environment. (Johnson&Johnson, 2004)

76

C. Ditlev-Simonsen, S. Wenstp / Issues in Social and Environmental Accounting 1/2 (2011) 65-81

In this example we see how duty is presented through commitment (D) and the companys value (E). This value is not presented as financial value, profit, but more as an encompassing long-term focus on growth and leadership excellence, i.e. ethos (E) Fail (F) In seven of the reports we could not find any rhetoric ethical commitments. Most of these companies were small and generally had less voluminous reports. Some did not use the term responsibility, nor sustainability in their ethical rhetoric. Arla, a Danish Food producer and processor, is one example of a company stating a goal free of any CSR related

moral elements. Arla Foods mission is to offer modern consumers milk-based products that create inspiration, confidence and wellbeing. (Arla, 2005) Summary In sum, the analysis of the statements show that ethos (E) followed by agency (A) are the most frequently applied rhetoric elements for engaging in CSR. The most frequent pattern of moral reasoning appears to be one where benefit (B) is instrumental to agency (A). A pattern where duty (D) is instrumental to agency (A) also appears to be relatively common (ref. Table 3 and 4)

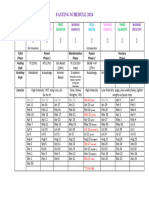

Table 3: Summary of Ethical Attitudes Reflected in CSR Reports

Agency (A) 10 Benefit (B) 13 Contract (C) 5 Duty (D) 7 Ethos (E) 26 Fail (F) 7

Table 4 Summary of Ethical Instruments for Another Ethical Attitude (patterns of moral reasoning)

Agency (A) Agency (A) Benefit (B) Contract (C) Duty (D) Benefit (B) Contract (C) Duty (D) Ethos (E)

9 1 4 2

2 1 2

2 1

2 3 -

Ethos (E)

5. Discussion and Conclusion Corporations issue non-financial reports on a voluntary basis, beyond what is required by accounting regulations. They are therefore relatively free to communicate normative content and make social commitments. As this paper

illustrates, the type of ethics rhetoric, and the practical and theoretical commitments implied in that rhetoric, as well as the expressed patterns of moral reasoning, varies considerably among the companies. Companies, or the persons writing the reports, express different opinions of why the corporation should en-

C. Ditlev-Simonsen, S. Wenstp / Issues in Social and Environmental Accounting 1/2 (2011) 65-81

77

gage in CSR and thus their role in society. The rhetorical landscape is pluralistic. Still, there is a centre of gravity around ethos (E). Almost a third of the companies would subscribe to We do CSR because we are virtuous although the exact formulations differ, but to be committed to some sort of ethos appears to be widespread. To just fulfil the idea of heeding some sort of law or social contract (C) seems much less widespread. Agency considerations (A) are expressed in a substantial number of the reports. Indeed many of the companies state this as their main CSR consideration. However, the agency perspective only seldom features alone. It is far more common to combine the agency perspective with other normative elements, most notably the benefit (B) perspective. This paper has investigated the 2005 reports of 80 companies which vary substantially with regards to location, sector, and size. To investigate this moral rhetoric more closely, further studies should select specific sectors in different countries. A plausible research aim would be to assess whether there are culturally related differences. A more comprehensive study of individual companies CSR reports to investigate if they express different moral attitudes towards different societal activities would also be an interesting avenue of research. The taxonomy of ethical rhetoric can be applied in research of individual companies as well as in comparative analysis. Since formal corporate statements involves doing something whether acts of informing us about facts, advocating certain things, giving specific promises, making moral commitments, or whatever the study of corporate rhetoric is important and deserves

intensified attention from social scientists.

References Aristotle, Trendennick, H., Thomson, J. A. K., & Barnes, J. (2004). The Nicomachean ethics. New York, NY, USA: Penguin Classics. Arla. (2005). A brief presentation 2005 (pp. 3). Austin, J. L. (1962). How to do things with words. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press. Bahm, A. J. (1983). "The Foundation of Business Ethics". Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 107-110. Barnard, C. I. (1938). The Functions of the Executive. Boston: The President and the Fellows at Harvard College. Bentham, J. (2000). An Introduction to the principles of morals and legislation. Kitchener, Ont.: Batoche. Bowie, N. E. (1999). Business ethics: a kantian perspective. Oxford: Blackwell. Brammer, S., & Pavelin, S. (2008). "Factors influencing the quality of corporate environmental disclosure". Business Strategy & the Environment, Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 120-136. Branco, M., & Rodrigues, L. (2008). "Factors Influencing Social Responsibility Disclosure by Portuguese Companies". Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 83, No. 4, pp. 685-701. doi: 10.1007/ s10551-007-9658-z Branco, M. C., & Rodrigues, L. L. (2007). "Issues in Corporate Social and Environmental

78

C. Ditlev-Simonsen, S. Wenstp / Issues in Social and Environmental Accounting 1/2 (2011) 65-81

Reporting Research: An Overview". Issues in Social & Environmental Accounting, Vol. 1, pp. 72-90. Campbell, J. L. (2007). "Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An insitutional theory of corporate social responsibility ". Academy of Management Review, Vol. 32, No. 3, pp. 946-967. Carrefour. (2004). Sustainability Report 2004 (pp. 3). Clarke, J., & Gibson-Sweet, M. (1999). "The use of corporate social disclosures in the management of reputation and legitimacy: a cross sectoral analysis of UK Top 100 Companies". Business Ethics: A European Review, Vol. 8, pp. 5-13. Corporate Register. (2008). "http:// www.corporateregister.com/ charts/byyear.htm" Crane, A., & Matten, D. (2004). Business ethics : a European perspective : managing corporate citizenship and sustainability in the age of globalization. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). "The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields". American Sociological Review, Vol. 48, No. 2, pp. 147-160. DnBNor. (2004). Annual report 2004 (pp. 18). Donaldson, T., & Dunfee, T. W. (1999). Ties that bind: a social contracts approach to business ethics. Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business School Press.

Eni. (2004). Health Safety Environment 2004 report (pp. 9). Freeman, E. R. (1984). Strategic Management, A Stakeholder Approach. Marshfield, Massachusetts: Pitman Publishing Inc. Friedman, M. (1970). The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase Its Profits The New York Times Magazine (Vol. September 13, 1970). Galaskiewicz, J. (1997). "An Urban Grants Economy Revisited: Corporate Charitable Contributions in the Twin Cities, 1979-81, 1987-89". Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 42, No. 3, pp. 445-471. Gauthier, D. (1986). Moral by Agreement. N.Y.: Oxford University Press. Hummels, H. (2004). "A Collective Lack of Memory". Journal of Corporate Citizenship, No. 14, pp. 18-21. Ihlen, . (2010). Slik snakker de om samfunnsansvar: http:// www.bi.no/Hovedstruktur/ Forskning-20/Nyheter-20/ Nyheter-2010/Slik-snakker-deom-samfunnsansvar/. Johnson&Johnson. (2004). 2004 Sustainability report (pp. 1). Jotun. (2005). SHE report 2005 (pp. 7). Joutsenvirta, M. (2009). A language perspective to environmental management and corporate responsibility Business Strategy & the Environment (John Wiley & Sons, Inc) (Vol. 18, pp. 240253). Kant, I. (1998). Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Moral.

C. Ditlev-Simonsen, S. Wenstp / Issues in Social and Environmental Accounting 1/2 (2011) 65-81

79

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Kaptein, M. (2007). "Ethical Guidelines for Compiling Corporate Social Reports". Journal of Corporate Citizenship, No. 27, pp. 71-90. KPMG. (2008). KPMG International Survey of Corporate Responsibility Reporting 2008. Livesey, S. M., & Kearins, K. (2002). "Transparent and Caring Corporations? A Study of Sustainability Reports by The Body Shop and Royal Dutch/ Shell". Organization & Environment, Vol. 15, No. 3, pp. 233. MacIntyre, A. (1984). After Virtue: a study in moral theory. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. Morsing, M., Schultz, M., & Nielsen, K. U. (2008). "The 'Catch 22' of communicating CSR: Findings from a Danish study". Journal of Marketing Communications, Vol. 14, No. 2, pp. 97-111. Nike. (2004). Corporate Responsibility Report (pp. 3). Nokia. (2004). Corporate responsibility report 2004 (pp. 3). O'Donovan, G. (2002). "Environmental disclosures in the annual report Extending the applicability and predictive power of legitimacy theory". Accounitn, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 15, No. 3, pp. 344-371.

Peab. (2004). Our most important values, company policy. Pfizer. How are we doing? Rand, A., & Branden, N. (1970). The virtue of selfishness: a new concept of egoism. New York: Signet. Rawls, J. (1971). A theory of justice. Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. Rosseau, J. (1984). A Discourse on Inequality: Penguin Book. RWE. (2003). Corporate Responsibility. Report 2003. Scott, W. R. (2008). Institutions and Organizations - Ideas and Interests (third ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. Singer, P. (1993). Practical ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Smith, A. (1991). Wealth of nations. Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books. Solomon, R. C. (1992). Ethics and Excellence: Cooperation and Integrity in Business. New York: Oxford University Press. Sony. (2005). CSR Report 2005 (pp. Preface). Systembolaget. (2004). Annual report 2004 (pp. 11). Wenstp, F., & Myrmel, A. (2006). "Structuring organizational value statements". Management Research News, Vol. 29, No. 11, pp. 673-683.

80

C. Ditlev-Simonsen, S. Wenstp / Issues in Social and Environmental Accounting 1/2 (2011) 65-81

Attatchment 1. Overview over Companies Evaluated

Company

Alcan Alcoa Arla Foods AstraZeneca Best Buy Bilfinger Berger BNFL Body Shop BP BT Camelot Carrefour Centrica Coca-Cola Comalco Coop DaimlerChrysler Danish Crown Dixons / DSG Int. DnB Dow DynoNobel Electrabel Eni Fortum GE Hydro IBM Ikea Johnson & Johnson Jotun Kingfisher Lundbeck Lyse MT Hjgaard Microsoft

Country

Canada USA Denmark, UK Sweden/UK USA Germany UK UK UK UK UK France UK USA Australia Norway Germany Denmark UK Norway USA Norway Belgum Italy Finland USA Norway USA Sweden USA Norway UK Denmark Norway Denmark USA

Sector

Steel & Other Metals Steel & Other Metals Food Producers & Processors Pharmaceuticals & Biotechnology General Retailer Construction & Building Materials Electricity General Retailer Oil & Gas Telecommunication Services Leisure, Entertainment & Hotels Food & Drug Retailer Gas Distribution Beverages Mining (Rio Tinto) General Retailer Automobiles & Parts Food Producers & Processors General Retailer Banks Chemicals Chemicals Electricity (Suez) Oil & Gas Oil & Gas Diversified Industrials Oil & Gas Information Technology Hardware Household Goods & Textiles Pharmaceuticals & Biotechnology Distributor General Retailer Pharmaceuticals & Biotechnology Electricity Construction & Building Materials Software & Computer Services

C. Ditlev-Simonsen, S. Wenstp / Issues in Social and Environmental Accounting 1/2 (2011) 65-81 Nestl NextGen Tel Nike Nokia NorgesGruppen Norsk Tipping Novo Nordisk Nuon Orkla Peab Pfizer Philip Morris Rieber (Toro) RWE SAQ Schibsted Securitas Shell SIBA Siemens Skanska Sony Starbucks Statoil Steen & Strm Stora Enso Storebrand Svenska Spel Swedish Meat Systembolaget Telenor Tine Tomra Total Toyota UPM Vattenfall Veidekke Verbund Volkswagen Vollvik (Chess) Volvo Cars Wal-Mart Yara Switzerland Norway USA Finland Norway Norway Denmark Netherlands Norway Sweden USA Switzerland Norway Germany Canada Norway Sweden UK/Netherlands Sweden Germany Sweden Japan USA Norway Norway Finland Norway Sweden Sweden Sweden Norway Norway Norway France Japan Finland Sweden Norway Austria Germany Norway Sweden USA Norway Food Producers & Processors Telecommunication Services Household Goods & Textiles Information Technology Hardware Food & Drug Retailer Leisure, Entertainment & Hotels Pharmaceuticals & Biotechnology Electricity Personal Care & Household Products Construction & Building Materials Pharmaceuticals & Biotechnology Tobacco (Altria) Diversified Industrials Multi-Utilities Food & Drug Retailer Media & Photography Diversified Industrials Oil & Gas General Retailer Electronic & Electrical Equipment Construction & Building Materials Electronic & Electrical Equipment Leisure, Entertainment & Hotels Oil & Gas Real Estate Forestry & Paper Speciality & Other Finance Leisure, Entertainment & Hotels Food & Drug Retailer Food & Drug Retailer Telecommunication Services Food Producers & Processors Engineering & Machinery Oil & Gas Automobiles & Parts Forestry & Paper Electricity Construction & Building Materials Electricity Automobiles & Parts Telecommunication Services Automobiles & Parts (Ford) General Retailer Chemicals

81

International Journals Call for Paper

The IISTE, a U.S. publisher, is currently hosting the academic journals listed below. The peer review process of the following journals usually takes LESS THAN 14 business days and IISTE usually publishes a qualified article within 30 days. Authors should send their full paper to the following email address. More information can be found in the IISTE website : www.iiste.org

Business, Economics, Finance and Management European Journal of Business and Management Research Journal of Finance and Accounting Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development Information and Knowledge Management Developing Country Studies Industrial Engineering Letters Physical Sciences, Mathematics and Chemistry Journal of Natural Sciences Research Chemistry and Materials Research Mathematical Theory and Modeling Advances in Physics Theories and Applications Chemical and Process Engineering Research Engineering, Technology and Systems Computer Engineering and Intelligent Systems Innovative Systems Design and Engineering Journal of Energy Technologies and Policy Information and Knowledge Management Control Theory and Informatics Journal of Information Engineering and Applications Industrial Engineering Letters Network and Complex Systems Environment, Civil, Materials Sciences Journal of Environment and Earth Science Civil and Environmental Research Journal of Natural Sciences Research Civil and Environmental Research Life Science, Food and Medical Sciences Journal of Natural Sciences Research Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare Food Science and Quality Management Chemistry and Materials Research Education, and other Social Sciences Journal of Education and Practice Journal of Law, Policy and Globalization New Media and Mass Communication Journal of Energy Technologies and Policy Historical Research Letter Public Policy and Administration Research International Affairs and Global Strategy Research on Humanities and Social Sciences Developing Country Studies Arts and Design Studies

PAPER SUBMISSION EMAIL EJBM@iiste.org RJFA@iiste.org JESD@iiste.org IKM@iiste.org DCS@iiste.org IEL@iiste.org PAPER SUBMISSION EMAIL JNSR@iiste.org CMR@iiste.org MTM@iiste.org APTA@iiste.org CPER@iiste.org PAPER SUBMISSION EMAIL CEIS@iiste.org ISDE@iiste.org JETP@iiste.org IKM@iiste.org CTI@iiste.org JIEA@iiste.org IEL@iiste.org NCS@iiste.org PAPER SUBMISSION EMAIL JEES@iiste.org CER@iiste.org JNSR@iiste.org CER@iiste.org PAPER SUBMISSION EMAIL JNSR@iiste.org JBAH@iiste.org FSQM@iiste.org CMR@iiste.org PAPER SUBMISSION EMAIL JEP@iiste.org JLPG@iiste.org NMMC@iiste.org JETP@iiste.org HRL@iiste.org PPAR@iiste.org IAGS@iiste.org RHSS@iiste.org DCS@iiste.org ADS@iiste.org

Global knowledge sharing: EBSCO, Index Copernicus, Ulrich's Periodicals Directory, JournalTOCS, PKP Open Archives Harvester, Bielefeld Academic Search Engine, Elektronische Zeitschriftenbibliothek EZB, Open J-Gate, OCLC WorldCat, Universe Digtial Library , NewJour, Google Scholar. IISTE is member of CrossRef. All journals have high IC Impact Factor Values (ICV).

You might also like

- Scientology Abridged Dictionary 1973Document21 pagesScientology Abridged Dictionary 1973Cristiano Manzzini100% (2)

- From CSR to the Ladders of Corporate Responsibilities and Sustainability (CRS) TaxonomyFrom EverandFrom CSR to the Ladders of Corporate Responsibilities and Sustainability (CRS) TaxonomyNo ratings yet

- Monster Visual Discrimination CardsDocument9 pagesMonster Visual Discrimination CardsLanaNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Teachers Motivation On The Overall Performance ofDocument16 pagesAnalysis of Teachers Motivation On The Overall Performance ofAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Study of CSR in Developedand Developing CountriesDocument23 pagesA Comparative Study of CSR in Developedand Developing Countriesindahmuliasari100% (3)

- Research Proposal On CSR and Corporate GovernanceDocument12 pagesResearch Proposal On CSR and Corporate GovernanceAmir Zeb100% (1)

- The Good The Bad and The Successful How Corporate Social Responsibility Leads To Competitive Advantage and Organizational TransformationDocument21 pagesThe Good The Bad and The Successful How Corporate Social Responsibility Leads To Competitive Advantage and Organizational TransformationPredi MădălinaNo ratings yet

- Angelomorphic Christology and The Book of Revelation - Matthias Reinhard HoffmannDocument374 pagesAngelomorphic Christology and The Book of Revelation - Matthias Reinhard HoffmannEusebius325100% (2)

- S06 - 1 THC560 DD311Document128 pagesS06 - 1 THC560 DD311Canchari Pariona Jhon AngelNo ratings yet

- Chronological OrderDocument5 pagesChronological OrderDharWin d'Wing-Wing d'AriestBoyzNo ratings yet

- SHORT STORY Manhood by John Wain - Lindsay RossouwDocument17 pagesSHORT STORY Manhood by John Wain - Lindsay RossouwPrincess67% (3)

- Corporate Social ResponsibilityDocument4 pagesCorporate Social Responsibilitykhozema1No ratings yet

- Oracle Unified Method (OUM) White Paper - Oracle's Full Lifecycle Method For Deploying Oracle-Based Business Solutions - GeneralDocument17 pagesOracle Unified Method (OUM) White Paper - Oracle's Full Lifecycle Method For Deploying Oracle-Based Business Solutions - GeneralAndreea Mirosnicencu100% (1)

- Positive Accounting TheoryDocument14 pagesPositive Accounting TheorygandhunkNo ratings yet

- Building and Enhancing New Literacies Across The CurriculumDocument119 pagesBuilding and Enhancing New Literacies Across The CurriculumLowela Kasandra100% (3)

- Compromiso EticoDocument18 pagesCompromiso EticoGabu CamachoNo ratings yet

- Dissertation On CSRDocument19 pagesDissertation On CSRImran AhmedNo ratings yet

- Article Title Page: From Altruistic To Strategic CSR: How Social Value Affected CSR Development-A Case Study of ThailandDocument40 pagesArticle Title Page: From Altruistic To Strategic CSR: How Social Value Affected CSR Development-A Case Study of ThailandSiti Noormi AliasNo ratings yet

- Corporate Social Responsibility Research in Accounting WordDocument17 pagesCorporate Social Responsibility Research in Accounting Wordpuspa100% (1)

- 52119607Document31 pages52119607Getaw AlamnewNo ratings yet

- CSR in Public Sector Has Wider Meaning Than PrivateDocument15 pagesCSR in Public Sector Has Wider Meaning Than PrivateElianaNo ratings yet

- Corporate Social Responsibility, Financial and Human Resource Management: A Systematic Review and Conceptual AnalysisDocument13 pagesCorporate Social Responsibility, Financial and Human Resource Management: A Systematic Review and Conceptual Analysisindex PubNo ratings yet

- Corporate Social and Environmental Responsibility in Web-Based Reports Currency in The BankinDocument17 pagesCorporate Social and Environmental Responsibility in Web-Based Reports Currency in The Bankinartha wibawaNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Corporate Social Responsibility and EthicsDocument4 pagesLiterature Review On Corporate Social Responsibility and EthicsaflshftafNo ratings yet

- CSRDocument11 pagesCSRMotin UddinNo ratings yet

- Rameez Shakaib MSA 3123Document7 pagesRameez Shakaib MSA 3123OsamaMazhariNo ratings yet

- Corporate Social Responsibility and Smes A Literature Review and Agenda For Future ResearchDocument5 pagesCorporate Social Responsibility and Smes A Literature Review and Agenda For Future Researchfut0mipujeg3No ratings yet

- A Comparative Study of CSR in A Croatian and A UK CompanyDocument57 pagesA Comparative Study of CSR in A Croatian and A UK CompanySammy Muli BNo ratings yet

- CSR 2Document7 pagesCSR 2Shravan RamsurrunNo ratings yet

- Research of 6th Sem Ethics PrakDocument7 pagesResearch of 6th Sem Ethics PrakPrakruthiNo ratings yet

- IOP2013Document19 pagesIOP2013MitzuNo ratings yet

- Economic Perspectives On CSRDocument34 pagesEconomic Perspectives On CSRPinkz JanabanNo ratings yet

- Kingsley Nwagu Viva Voce PresentationDocument48 pagesKingsley Nwagu Viva Voce PresentationKingsley NwaguNo ratings yet

- Corporate Social and Environmental Auditing: Perceived Responsibility or Regulatory Requirement?Document11 pagesCorporate Social and Environmental Auditing: Perceived Responsibility or Regulatory Requirement?Ahmad SyaifudinNo ratings yet

- CSR IntroductionDocument7 pagesCSR IntroductionBG GoelNo ratings yet

- A Literature Review On Corporate Social Responsibility in The Innovation ProcessDocument5 pagesA Literature Review On Corporate Social Responsibility in The Innovation Processea8p6td0No ratings yet

- Chapter OneDocument76 pagesChapter OnesushankmbafinanceNo ratings yet

- Corporate Governance, Social Responsibility and Business EthicsDocument12 pagesCorporate Governance, Social Responsibility and Business EthicsAshish KumarNo ratings yet

- Charcteristics of CSRDocument21 pagesCharcteristics of CSRrohitNo ratings yet

- An Institution of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in Multi-National Corporations (MNCS) : Form and ImplicationsDocument44 pagesAn Institution of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in Multi-National Corporations (MNCS) : Form and ImplicationsJhovany Amastal MolinaNo ratings yet

- Social Audit Article 5Document10 pagesSocial Audit Article 5DHANRAJ KAUSHIKNo ratings yet

- CSR Definitions and CSR Measurement MethodsDocument4 pagesCSR Definitions and CSR Measurement MethodsSyful An-nuarNo ratings yet

- Social Responsibility and Financial Performance - The Role of Good Corporate GovernanceDocument15 pagesSocial Responsibility and Financial Performance - The Role of Good Corporate GovernanceRiyan Ramadhan100% (1)

- Employees Perception Towards Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Initiatives of Ethiopian Brewery IndustryDocument9 pagesEmployees Perception Towards Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Initiatives of Ethiopian Brewery Industryarcherselevators100% (1)

- Task 746Document8 pagesTask 746hoangphuongthonguyenNo ratings yet

- Patrycjagulaklipka,+018 KsiezakDocument16 pagesPatrycjagulaklipka,+018 KsiezakSheriff SheriffNo ratings yet

- Communication of Corporate Social Responsibility: A Study of The Views of Management Teams in Large CompaniesDocument16 pagesCommunication of Corporate Social Responsibility: A Study of The Views of Management Teams in Large CompaniesGurmani ChadhaNo ratings yet

- CSR in Banking Sector: International Journal of Economics, Commerce and ManagementDocument22 pagesCSR in Banking Sector: International Journal of Economics, Commerce and ManagementmustafaNo ratings yet

- Corporate Social Responsibility, Financial and Human Resource Management: A Systematic Review and Conceptual AnalysisDocument13 pagesCorporate Social Responsibility, Financial and Human Resource Management: A Systematic Review and Conceptual Analysisindex PubNo ratings yet

- 02 SCOPUS - The Social Responsibility of Organizations Perceptions ofDocument17 pages02 SCOPUS - The Social Responsibility of Organizations Perceptions ofGung IsNo ratings yet

- Empirical Literature Review On Corporate Social ResponsibilityDocument9 pagesEmpirical Literature Review On Corporate Social Responsibilityc5t9rejgNo ratings yet

- CSR GCG - 1Document21 pagesCSR GCG - 1ESantosoNo ratings yet

- Corporate social performance inter-industry and international differencesDocument29 pagesCorporate social performance inter-industry and international differencesdessyNo ratings yet

- CSR Performance in Four European CountriesDocument21 pagesCSR Performance in Four European CountriesmaluNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On CSR ActivitiesDocument4 pagesLiterature Review On CSR Activitiesafmzuiffugjdff100% (1)

- Business EthicsDocument11 pagesBusiness Ethicstemesgen yematewNo ratings yet

- Dissertation On Corporate Social Responsibility PDFDocument4 pagesDissertation On Corporate Social Responsibility PDFPaperWritingServicesReviewsCanadaNo ratings yet

- CULTURE, GOVERNANCE AND CSR REPORTING QUALITYDocument27 pagesCULTURE, GOVERNANCE AND CSR REPORTING QUALITYRudy HartantoNo ratings yet

- Chapitre World Scientific PublisherDocument45 pagesChapitre World Scientific PublishermarkjunjacusalemNo ratings yet

- Stakeholder Management Paradoxes From The Perspective of Normative, Descriptive and Instrumental ApproachDocument9 pagesStakeholder Management Paradoxes From The Perspective of Normative, Descriptive and Instrumental ApproachAaNo ratings yet

- Asongu 2007 - CSR As A Marketing ToolDocument12 pagesAsongu 2007 - CSR As A Marketing ToolchunkypopsNo ratings yet

- Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial Performance in Developing Economies: The Nigerian ExperienceDocument12 pagesCorporate Social Responsibility and Financial Performance in Developing Economies: The Nigerian ExperienceMinh NguyenNo ratings yet

- J Ribaf 2017 07 151Document33 pagesJ Ribaf 2017 07 151Nur Alfiyatuz ZahroNo ratings yet

- Grażyna Wolska: Corporate Social Responsibility in Poland - Theory and PracticeDocument12 pagesGrażyna Wolska: Corporate Social Responsibility in Poland - Theory and PracticeDIDIER DROGBANo ratings yet

- What We Know and Don't Know About Corporate Social Responsibility A Review and Research AgendaDocument39 pagesWhat We Know and Don't Know About Corporate Social Responsibility A Review and Research AgendaAndra ComanNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Accounting: Suresh Radhakrishnan, Albert Tsang, Rubing LiuDocument21 pagesInternational Journal of Accounting: Suresh Radhakrishnan, Albert Tsang, Rubing LiuHutama Putra JuniriansyahNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On CSR ReportingDocument6 pagesLiterature Review On CSR Reportingafmzxutkxdkdam100% (1)

- The Determinants Influencing The Extent of CSR DisclosureDocument25 pagesThe Determinants Influencing The Extent of CSR DisclosurePrahesti Ayu WulandariNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Teachers' and Principals' Opinion On Causes of LowDocument15 pagesAssessment of Teachers' and Principals' Opinion On Causes of LowAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Availability, Accessibility and Use of Information Resources and Services Among Information Seekers of Lafia Public Library in Nasarawa StateDocument13 pagesAvailability, Accessibility and Use of Information Resources and Services Among Information Seekers of Lafia Public Library in Nasarawa StateAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Relationships Between Students' Counselling NeedsDocument17 pagesAssessment of Relationships Between Students' Counselling NeedsAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Asymptotic Properties of Bayes Factor in One - Way Repeated Measurements ModelDocument17 pagesAsymptotic Properties of Bayes Factor in One - Way Repeated Measurements ModelAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Some Micronutrient (ZN and Cu) Status of Fadama Soils Under Cultivation in Bauchi, NigeriaDocument7 pagesAssessment of Some Micronutrient (ZN and Cu) Status of Fadama Soils Under Cultivation in Bauchi, NigeriaAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Availability and Use of Instructional Materials and FacilitiesDocument8 pagesAvailability and Use of Instructional Materials and FacilitiesAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Housing Conditions For A Developing Urban Slum Using Geospatial AnalysisDocument17 pagesAssessment of Housing Conditions For A Developing Urban Slum Using Geospatial AnalysisAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Assessment of The Practicum Training Program of B.S. Tourism in Selected UniversitiesDocument9 pagesAssessment of The Practicum Training Program of B.S. Tourism in Selected UniversitiesAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Concerning Food Safety Among Restaurant Workers in Putrajaya, MalaysiaDocument10 pagesAssessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Concerning Food Safety Among Restaurant Workers in Putrajaya, MalaysiaAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Effect of Liquidity On Profitability of Commercial Banks in KenyaDocument10 pagesAssessing The Effect of Liquidity On Profitability of Commercial Banks in KenyaAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Attitude of Muslim Female Students Towards Entrepreneurship - A Study On University Students in BangladeshDocument12 pagesAttitude of Muslim Female Students Towards Entrepreneurship - A Study On University Students in BangladeshAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Barriers To Meeting The Primary Health Care Information NeedsDocument8 pagesBarriers To Meeting The Primary Health Care Information NeedsAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Survivors' Perceptions of Crises and Retrenchments in The Nigeria Banking SectorDocument12 pagesAssessment of Survivors' Perceptions of Crises and Retrenchments in The Nigeria Banking SectorAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Assessment of The Skills Possessed by The Teachers of Metalwork in The Use of Computer Numerically Controlled Machine Tools in Technical Colleges in Oyo StateDocument8 pagesAssessment of The Skills Possessed by The Teachers of Metalwork in The Use of Computer Numerically Controlled Machine Tools in Technical Colleges in Oyo StateAlexander Decker100% (1)

- Are Graduates From The Public Authority For Applied Education and Training in Kuwaiti Meeting Industrial RequirementsDocument10 pagesAre Graduates From The Public Authority For Applied Education and Training in Kuwaiti Meeting Industrial RequirementsAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Productive and Reproductive Performances of CrossDocument5 pagesAssessment of Productive and Reproductive Performances of CrossAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Application of The Diagnostic Capability of SERVQUAL Model To An Estimation of Service Quality Gaps in Nigeria GSM IndustryDocument14 pagesApplication of The Diagnostic Capability of SERVQUAL Model To An Estimation of Service Quality Gaps in Nigeria GSM IndustryAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Applying Multiple Streams Theoretical Framework To College Matriculation Policy Reform For Children of Migrant Workers in ChinaDocument13 pagesApplying Multiple Streams Theoretical Framework To College Matriculation Policy Reform For Children of Migrant Workers in ChinaAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Factors Responsible For Organizational PoliticsDocument7 pagesAssessment of Factors Responsible For Organizational PoliticsAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Assessment in Primary School Mathematics Classrooms in NigeriaDocument8 pagesAssessment in Primary School Mathematics Classrooms in NigeriaAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Antibiotic Resistance and Molecular CharacterizationDocument12 pagesAntibiotic Resistance and Molecular CharacterizationAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Assessment For The Improvement of Teaching and Learning of Christian Religious Knowledge in Secondary Schools in Awgu Education Zone, Enugu State, NigeriaDocument11 pagesAssessment For The Improvement of Teaching and Learning of Christian Religious Knowledge in Secondary Schools in Awgu Education Zone, Enugu State, NigeriaAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Application of Panel Data To The Effect of Five (5) World Development Indicators (WDI) On GDP Per Capita of Twenty (20) African Union (AU) Countries (1981-2011)Document10 pagesApplication of Panel Data To The Effect of Five (5) World Development Indicators (WDI) On GDP Per Capita of Twenty (20) African Union (AU) Countries (1981-2011)Alexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Analyzing The Economic Consequences of An Epidemic Outbreak-Experience From The 2014 Ebola Outbreak in West AfricaDocument9 pagesAnalyzing The Economic Consequences of An Epidemic Outbreak-Experience From The 2014 Ebola Outbreak in West AfricaAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Antioxidant Properties of Phenolic Extracts of African Mistletoes (Loranthus Begwensis L.) From Kolanut and Breadfruit TreesDocument8 pagesAntioxidant Properties of Phenolic Extracts of African Mistletoes (Loranthus Begwensis L.) From Kolanut and Breadfruit TreesAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- An Investigation of The Impact of Emotional Intelligence On Job Performance Through The Mediating Effect of Organizational Commitment-An Empirical Study of Banking Sector of PakistanDocument10 pagesAn Investigation of The Impact of Emotional Intelligence On Job Performance Through The Mediating Effect of Organizational Commitment-An Empirical Study of Banking Sector of PakistanAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Frauds in Banks Nigeria's ExperienceDocument12 pagesAnalysis of Frauds in Banks Nigeria's ExperienceAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Analysis The Performance of Life Insurance in Private InsuranceDocument10 pagesAnalysis The Performance of Life Insurance in Private InsuranceAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Aerospace Opportunities in SwitzerlandDocument5 pagesAerospace Opportunities in SwitzerlandBojana DekicNo ratings yet

- IPO Fact Sheet - Accordia Golf Trust 140723Document4 pagesIPO Fact Sheet - Accordia Golf Trust 140723Invest StockNo ratings yet

- BarclaysDocument5 pagesBarclaysMehul KelkarNo ratings yet

- Classroom Observation Form 1Document4 pagesClassroom Observation Form 1api-252809250No ratings yet

- State of Education in Tibet 2003Document112 pagesState of Education in Tibet 2003Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and DemocracyNo ratings yet

- Appliance Saver Prevents OverheatingDocument2 pagesAppliance Saver Prevents OverheatingphilipNo ratings yet

- U-KLEEN Moly Graph MsdsDocument2 pagesU-KLEEN Moly Graph MsdsShivanand MalachapureNo ratings yet

- CHEMICAL ANALYSIS OF WATER SAMPLEDocument5 pagesCHEMICAL ANALYSIS OF WATER SAMPLEAiron Fuentes EresNo ratings yet

- How To Pass in University Arrear Exams?Document26 pagesHow To Pass in University Arrear Exams?arrearexam100% (6)

- Visualization BenchmarkingDocument15 pagesVisualization BenchmarkingRanjith S100% (1)

- $R6RN116Document20 pages$R6RN116chinmay gulhaneNo ratings yet

- Indonesia Banks Bank Mandiri Trading Buy on Strong 9M21 EarningsDocument8 pagesIndonesia Banks Bank Mandiri Trading Buy on Strong 9M21 EarningsdkdehackerNo ratings yet

- Quick Reference - HVAC (Part-1) : DECEMBER 1, 2019Document18 pagesQuick Reference - HVAC (Part-1) : DECEMBER 1, 2019shrawan kumarNo ratings yet

- Moon Fast Schedule 2024Document1 pageMoon Fast Schedule 2024mimiemendoza18No ratings yet

- Grade 8 Lily ExamDocument3 pagesGrade 8 Lily ExamApril DingalNo ratings yet

- Eportfile 4Document6 pagesEportfile 4api-353164003No ratings yet

- Smoktech Vmax User ManualDocument9 pagesSmoktech Vmax User ManualStella PapaNo ratings yet

- The Interview: P F T IDocument14 pagesThe Interview: P F T IkkkkccccNo ratings yet

- Jotrun TDSDocument4 pagesJotrun TDSBiju_PottayilNo ratings yet

- AnhvancDocument108 pagesAnhvancvanchienha7766No ratings yet

- Interesting Facts (Compiled by Andrés Cordero 2023)Document127 pagesInteresting Facts (Compiled by Andrés Cordero 2023)AndresCorderoNo ratings yet

- Serendipity - A Sociological NoteDocument2 pagesSerendipity - A Sociological NoteAmlan BaruahNo ratings yet