Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chapter 160 Diarrhea and Constipation Onkologi 2

Uploaded by

Khanszarizennia Madany Agri0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views26 pagesBEDAH

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentBEDAH

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views26 pagesChapter 160 Diarrhea and Constipation Onkologi 2

Uploaded by

Khanszarizennia Madany AgriBEDAH

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 26

Textbook Reading

CHAPTER 160 DIARRHEA AND

CONSTIPATION

Devita, Hellman, Rosenberg. Cancer: Principles and Practice

of Oncology 9th edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Publishers. 2011

Introduction

• Constipation and diarrhea are :

– both common problems.

– life-threatening dehydration and electrolyte

abnormalities.

– opioid analgesics constipation more

common that diarrhea.

• the strategies to evaluate and manage these

common and distressing symptoms.

DIARRHEA

• Diarrhea is defined as the frequent passage of loose stools

with urgency.

• Objectively defined, it is the passage of more than three

unformed stools in 24 hours.

• Diarrhea is

– among patients with advanced cancer.

– a major treatment complication (fluoropyrimidines and

irinotecan).

• The causes of diarrhea are diverse require specific

therapies.

• Severe diarrhea = dehydration, electrolyte imbalance,

malnutrition, declining immune function, and pressure ulcer

formation.

Chemotherapy-Induced Diarrhea

• The chemotherapy agents commonly causing

diarrhea include :

– 5-fluorouracil,

– capecitabine, and

– irinotecan ( CPT- 1 1 ) .

– The taxane, docetaxel, commonly causes a relatively

mild diarrhea.

• Chemotherapy acute damage to the intestinal

mucosa imbalance between absorption and

secretion in the small bowel.

Neutropenic Colitis

(necrotizing enterocolitis or typhlitis)

• an acute life-threatening complication of chemotherapy

• most commonly observed with high-dose treatments in the

setting of myeloablative therapies.

• also observed with nonmyeloablative therapies, particularly

with taxanes.

• Clinical Presentation:

– neutrophil count falls below 500 mcL.

– fever, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and, not

uncommonly, sepsis.

– Abdominal pain may be diffuse or localized to the right lower

quadrant.

– Sometimes pain is absent, particularly if the patient has

received steroid therapy

Pathogenesis of neutropenic

enterocolitis

• Multifactorial:

– mucosal injury,

– profound neutropenia, and

– impaired host defense to invasion by microorganisms.

• The microbial infection leads to necrosis of various layers of

the bowel wall.

• The predilection for the cecum is possibly related to its

dispensability and its relatively diminished vascularization.

• Bacteremia or fungemia is also common, usually with enteric

organisms such as pseudomonas or yeasts such as Candida

Diagnostic Investigations

• The diagnosis is based on signs and symptoms

in the appropriate clinical setting as well as

imaging studies.

– Plain abdominal radiographs

– Computed tomography ( CT) scanning

Targeted Therapy-Associated Diarrhea

• 30 % to 50 % of patients who receive bortezomib,

erlotinib, gefitinib, sorafenib, sunitinib, and

imatinib, and the mammalian target of rapamycin

(mTOR) inhibitors temsirolimus and everolimus.

• The monoclonal therapies targeting epidermal

growth factor receptor (EGFR), cetuximab and

panitumumab, both cause diarrhea in 10 % to 20

% of patients, which may be severe in a small

subset of patients

Other Causes of Treatment-Related

Diarrhea

• Clostridium Difficile Diarrhea

• Enteral Feeding

• Celiac Plexus Block

Assessment

General Principles in the

Management of Diarrhea

• Patients must be rehydrated either orally or,

when appropriate, by parenteral infusion.

• In general, milk products should be avoided

• Special attention should be given to patients

who are incontinent of stool due to the risk of

pressure ulcer formation.

• Skin barriers should be used to prevent skin

irritation caused by fecal material.

Antidiarrhea Medications

• Opioids

• Somatostatin Analogues

• Other Agents (Budesonide)

Specific Management Guidelines

American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO )

guidelines for management of treatment-

induced diarrhea were published in 2004.

– Patients are classified as uncomplicated or

complicated

Uncomplicated Diarrhea

• Managed conservatively with oral hydration and

loperamide.

• Initial management of mild to moderate diarrhea:

– dietary modifications

– the patient should be instructed to record the number

of stools and report symptoms of life-threatening

sequelae (e.g., fever or dizziness on standing)

– Loperamide: initial dose of 4 mg followed by 2 mg

every 4 hours or after every unformed stool (not to

exceed 16 mg/d) .

Uncomplicated Diarrhea

• If diarrhea resolves with loperamide, the patients

should be instructed to continue dietary modifications

and to gradually add solid foods to their diet.

• In the case of chemotherapy induced diarrhea, patients

may discontinue loperamide when they have been

diarrhea-free for at least 12 hours .

• The second step, if mild to moderate diarrhea persists

for more than 24 hours, is to increase the dose of

loperamide to 2 mg every 2 hours, and oral antibiotics

may be started as prophylaxis for infection.

Uncomplicated Diarrhea

• The third step, if mild to moderate

chemotherapy-induced diarrhea has not resolved

after 24 hours on high-dose loperamide (48 hours

total treatment with loperamide) , further

evaluation, including complete stool and blood

workup.

– Fluids and electrolytes should be replaced as needed.

– Loperamide should be discontinued, a second-line

antidiarrheal agent such as subcutaneous octreotide (

100 to 150 mcg starting dose, with dose escalation as

needed) or other second-line agents ( e.g., oral

budesonide or tincture of opium ) .

Complicated Chemotherapy-Induced

Diarrhea

• Patients with mild to moderate diarrhea complicated by

moderate to severe cramping, nausea and vomiting,

diminished performance status, fever, sepsis, neutropenia,

bleeding, or dehydration and patients with severe diarrhea

are classified as complicated and should be evaluated

further, monitored closely, and treated aggressively.

• Aggressive management of complicated cases usually

necessitates admission and involves administering

intravenous fluids, octreotide at a starting dose of 100 to

150 mcg subcutaneous three times a day or intravenous (25

to 50 mcg/h) if the patient is severely dehydrated, with

dose escalation up to 50 mcg subcutaneous three times a

day until diarrhea is controlled, and administration of

antibiotics (e.g., fluoroquinolone) .

CONSTIPATION

• Constipation is the slow movement of feces through the large

intestine, resulting in infrequent bowel movements and the passage

of dry, hard stools.

• Rome 2 Criteria for chronic constipation is the presence of any two

of the following symptoms for at least 12 weeks ( not necessarily

consecutive) in the previous 12 months:

– straining during bowel movements;

– lumpy or hard stool;

– sensation of incomplete evacuation;

– sensation of anorectal blockage or obstruction;

– less than three bowel movements per week.

• Prevalence : approximately 40 % to 60 % in advanced cancer; the

greatest prevalence occurs in the opioid-treated population.

Treatment-Related Causes

Differential Diagnosis

1. Low-Fiber Diet

2. Dehydration

3. Lack of Exercise

4. Colonic Pathology

5. Neuromuscular Disorders

6. Metabolic Disorders

7. Psychological Disorders

Diagnosis

• The medical history can assist in identifying the causes of

constipation.

• An accurate history should elicit the change in bowel

movements: frequency of bowel movements; whether

defecation is associated with blood or mucus (suggestive of

obstruction or hemorrhoids) , pain, or straining; presence

or absence of defecation urge (hard stool or rectal

obstruction in former, colon inertia in latter ) ; manual

maneuvers by patient.

• Questions should also be aimed to determine the cause of

the change in bowel movements, in particular eating and

drinking habits, medication use, and level of physical

activity.

Diagnosis

• The physical assessment could include a rectal examination to

evaluate sphincter tone and detect tenderness, obstruction, or

blood. Digital rectal examination may reveal:

– hard, impacted feces

– soft stool due to fecal leakage

– complete absence of stool (colonic inertia, high obstruction, or

impacted stools)

– tumor masses

– concomitant disease-hemorrhoids, anal fissure, perianal ulceration,

rectocele or anal stenosis

• If constipation manifests as part of a spinal cord compression

syndrome, full neurological examination is necessary including

assessment of anal sphincter tone (lax with colonic hypotonia) and

rectal sensation.

Investigation

• Investigations are not routinely necessary,

however, plain abdominal radiography may be

indicated to exclude bowel obstruction and to

distinguish stool from tumor.

• Plain abdominal radiography is also the best way

to assess the degree of constipation.

• More extensive testing can proceed for patients

with severe symptoms, for those with sudden

changes in number and consistency of bowel

movements or blood in the stool, and for older

adults

General Measures

• General Measures

– Diet

– Fluid Intake

– Physical Activity

• Laxatives: Bulk Laxatives, Osmotic Laxatives,

Magnesium and Sulfate Salts, Stimulant

Laxatives

• Enemas and Suppositories

Managing Fecal Impaction

• The treatment of a fecal impaction usually

requires the digital fragmentation and extraction

of the stool.

• Lubricating enemas and suppositories may be

helpful.

• Since this is a very uncomfortable procedure,

sedation is generally recommended and

anesthesia may occasionally be needed.

• Once the impaction is relieved, it is crucial that

the patient start a prophylactic daily bowel

regimen.

THANK YOU

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Metabolic Emergencies: Textbook ReadingDocument48 pagesMetabolic Emergencies: Textbook ReadingKhanszarizennia Madany AgriNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Metabolic EmergenciesDocument48 pagesMetabolic EmergenciesKhanszarizennia Madany AgriNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Marina PlantillaDocument28 pagesMarina PlantillaYamil Molina LópezNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Metabolic EmergenciesDocument48 pagesMetabolic EmergenciesKhanszarizennia Madany AgriNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- SalerioDocument28 pagesSalerioRizqaFebrilianyNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Diphtheria Clinical Features and ComplicationsDocument12 pagesDiphtheria Clinical Features and ComplicationsSasuke Grand TNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Cataract: Care of The Adult Patient WithDocument43 pagesCataract: Care of The Adult Patient WithAnna Francesca AbarquezNo ratings yet

- Diphtheria: Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Role of Immunization in PreventioDocument6 pagesDiphtheria: Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Role of Immunization in PreventioNur Rahmat WibowoNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Global Initiative For COPDDocument44 pagesGlobal Initiative For COPDsajid_saiyadNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Clinically Oriented Anatomy, 5th Edition - 5. Lower LimbDocument155 pagesClinically Oriented Anatomy, 5th Edition - 5. Lower LimbKhanszarizennia Madany AgriNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Clinically Oriented Anatomy, 5th Edition - 6. Upper LimbDocument178 pagesClinically Oriented Anatomy, 5th Edition - 6. Upper LimbKhanszarizennia Madany AgriNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Cataract: Care of The Adult Patient WithDocument43 pagesCataract: Care of The Adult Patient WithAnna Francesca AbarquezNo ratings yet

- Clinically Oriented Anatomy, 5th Edition - 3. Pelvis and PerineumDocument121 pagesClinically Oriented Anatomy, 5th Edition - 3. Pelvis and PerineumKhanszarizennia Madany AgriNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Clinically Oriented Anatomy, 5th Edition - 6. Upper LimbDocument178 pagesClinically Oriented Anatomy, 5th Edition - 6. Upper LimbKhanszarizennia Madany AgriNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Clinically Oriented Anatomy, 5th Edition - 4. BackDocument79 pagesClinically Oriented Anatomy, 5th Edition - 4. BackKhanszarizennia Madany AgriNo ratings yet

- Clinically Oriented Anatomy, 5th Edition - 2. AbdomenDocument159 pagesClinically Oriented Anatomy, 5th Edition - 2. AbdomenKhanszarizennia Madany AgriNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Clinically Oriented Anatomy, 5th Edition - Introduction To Clinically Oriented AnatomyDocument70 pagesClinically Oriented Anatomy, 5th Edition - Introduction To Clinically Oriented AnatomyKhanszarizennia Madany AgriNo ratings yet

- AcidDocument4 pagesAcidKhanszarizennia Madany AgriNo ratings yet

- Clinically Oriented Anatomy, 5th Edition - 1. ThoraxDocument139 pagesClinically Oriented Anatomy, 5th Edition - 1. ThoraxKhanszarizennia Madany Agri100% (2)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Clinically Oriented Anatomy, 5th Edition - 2. AbdomenDocument159 pagesClinically Oriented Anatomy, 5th Edition - 2. AbdomenKhanszarizennia Madany AgriNo ratings yet

- Honing Treatment Strategies in Advanced Prostate Cancer: Latest Evidence to Guide Clinical PracticeDocument50 pagesHoning Treatment Strategies in Advanced Prostate Cancer: Latest Evidence to Guide Clinical PracticeAnaSofiyNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- 4Document13 pages4Juan Carlos Hernandez CriadoNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Metastatic Pancreatic CancerDocument16 pagesMetastatic Pancreatic CancerJorge Osorio100% (1)

- Chapter 3 - Tissue Renewal, Regeneration, and RepairDocument12 pagesChapter 3 - Tissue Renewal, Regeneration, and RepairAgnieszka WisniewskaNo ratings yet

- Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Caused by Electromagnetic Fields (EMF) ?Document6 pagesChronic Fatigue Syndrome Caused by Electromagnetic Fields (EMF) ?SwissTeslaNo ratings yet

- Main Journal Lorenc2020Document14 pagesMain Journal Lorenc2020Kevin CindarjoNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Hidronefrosis 2Document5 pagesHidronefrosis 2Zwinglie SandagNo ratings yet

- Benign Skin Lesions Types and CharacteristicsDocument17 pagesBenign Skin Lesions Types and Characteristicsgarfield1No ratings yet

- WBUHS 3rd Prof Part-2 Question BankDocument174 pagesWBUHS 3rd Prof Part-2 Question BankAnindya BiswasNo ratings yet

- Entamoeba histolytica (True PathogenDocument112 pagesEntamoeba histolytica (True PathogenMiaQuiambaoNo ratings yet

- IsolationDocument5 pagesIsolationapi-392611220No ratings yet

- Fiziologia2014 1 PDFDocument48 pagesFiziologia2014 1 PDFConstantinPăvăloaiaNo ratings yet

- An Uncommon Cause of Antepartum Haemorrhage: A Case Study: January 2019Document7 pagesAn Uncommon Cause of Antepartum Haemorrhage: A Case Study: January 2019SriMathi Kasi Malini ArmugamNo ratings yet

- Breast ExaminationDocument4 pagesBreast ExaminationOlamide FeyikemiNo ratings yet

- Viva-Questions Community MedicineDocument3 pagesViva-Questions Community Medicineadeel_khan_48No ratings yet

- Cemento-Osseous Dysplasia Masquerading as CystDocument5 pagesCemento-Osseous Dysplasia Masquerading as CystQintari FauziaNo ratings yet

- 18 Male Hypogonadism LR1Document24 pages18 Male Hypogonadism LR1Retma Rosela NurkayantyNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Golden Rule: 1. Less Fried Food 2. Less FruitDocument6 pagesGolden Rule: 1. Less Fried Food 2. Less FruitRaymond LiemNo ratings yet

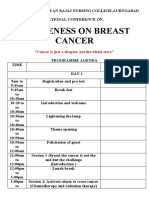

- National ConferenceDocument3 pagesNational Conferencelaveena aswaleNo ratings yet

- RH BillDocument13 pagesRH BillDr. Liza ManaloNo ratings yet

- Hematopoietic SystemDocument11 pagesHematopoietic Systemapi-247402827No ratings yet

- Kali SulphDocument31 pagesKali SulphShubhanshi BhasinNo ratings yet

- Soal Subdivisi Roo Eyelid NeoplasmDocument8 pagesSoal Subdivisi Roo Eyelid NeoplasmBudhi KaromaNo ratings yet

- 20 Questions On ObDocument5 pages20 Questions On ObCes Espino TorreNo ratings yet

- Earthing: Health Implications of Reconnecting The Human Body To The Earth's Surface ElectronsDocument9 pagesEarthing: Health Implications of Reconnecting The Human Body To The Earth's Surface ElectronsgilsonrossatoNo ratings yet

- M 4Document7 pagesM 4Aijem RyanNo ratings yet

- MSDS FuradanDocument8 pagesMSDS FuradanPopo Afiqah100% (1)

- Primary MyelofibrosisDocument82 pagesPrimary MyelofibrosisEmmanuel EkanemNo ratings yet

- Dafpus ParuDocument2 pagesDafpus ParuklontenganNo ratings yet

- TiradsDocument9 pagesTiradsDessy Riska SariNo ratings yet