Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Gastrointestinal Disorders

Uploaded by

Jobelle Acena0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

19 views40 pagesOriginal Title

GASTROINTESTINAL-DISORDERS.pptx

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

19 views40 pagesGastrointestinal Disorders

Uploaded by

Jobelle AcenaCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 40

OMPHALOCELE

• A protrusion of abdominal contents through the abdominal wall at

the point of the junction of the umbilical cord and abdomen.

• The herniated organs usually the intestines, but they may include

stomach and liver.

• The herniated organs are covered by the parietal peritoneum.

• After 10 weeks' gestation, the amnion and Wharton jelly also cover

the herniated mass.

Cause

• An omphalocele is a type of hernia. Hernia means "rupture."

• An omphalocele develops as a baby grows inside the mother's womb.

The muscles in the abdominal wall (umbilical ring) do not close

properly. As a result, the intestine remains outside the abdominal

wall.

• Infants with an omphalocele often have other birth defects. Defects

include genetic problems (chromosomal abnormalities), congenital

diaphragmatic hernia, and heart defects.

Symptoms

• An omphalocele can be clearly seen. This is because the abdominal

contents stick out (protrude) through the belly button area.

• There are different sizes of omphaloceles. In small ones, only the

intestines remain outside the body. In larger ones, the liver or spleen

may be outside as well.

Diagnosis

• Prenatal ultrasounds often identify infants with an omphalocele

before birth.

• Otherwise, a physical examination of the infant is enough for your

health care provider to diagnose this condition.

• Testing is usually not necessary.

Management

• Omphaloceles are repaired with surgery, although not always immediately.

• A sac protects the abdominal contents and allows time for other more

serious problems (such as heart defects) to be dealt with first, if necessary.

• To fix an omphalocele, the sac is covered with a special man-made

material, which is then stitched in place to form what is referred to as a

“silo”. Slowly, as the baby grows over time, the abdominal contents are

pushed into the abdomen.

• When the omphalocele can comfortably fit within the abdominal cavity,

the silo is removed and the abdomen is closed.

• Sometimes the omphalocele is so large that it cannot be placed back inside

the infant's abdomen. The skin around the omphalocele grows and

eventually covers the omphalocele. The abdominal muscles and skin can be

repaired when the child is older for a better cosmetic outcome.

GASTROSCHISIS

• Gastroschisis is a birth defect of the abdominal (belly) wall. The baby’s

intestines stick outside of the baby’s body, through a hole beside the

belly button. The hole can be small or large and sometimes other

organs, such as the stomach and liver, can also stick outside of the

baby’s body.

• Gastroschisis occurs early during pregnancy when the muscles that

make up the baby’s abdominal wall do not form correctly. A hole

occurs which allows the intestines and other organs to extend outside

of the body, usually to the right side of belly button. Because the

intestines are not covered in a protective sac and are exposed to the

amniotic fluid, the bowel can become irritated, causing it to shorten,

twist, or swell.

Causes/Risk Factors

• Like many families affected by birth defects, Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention (CDC) wants to find out what causes them.

• Recently, CDC researchers have reported important findings about

some factors that affect the risk of having a baby with gastroschisis:

• Younger age: teenage mothers were more likely to have a baby with

gastroschisis than older mothers, and White teenagers had higher

rates than Black or African-American teenagers.

• Alcohol and tobacco: women who consumed alcohol or were a

smoker were more likely to have a baby with gastroschisis.

Diagnosis

• Gastroschisis can be diagnosed during pregnancy or after the baby is

born.

• During pregnancy, there are screening tests (prenatal tests) to check

for birth defects and other conditions. Gastroschisis might result in an

abnormal result on a blood or serum screening test or it might be

seen during an ultrasound (which creates pictures of the body).

• Gastroschisis is immediately seen at birth.

Management

• Soon after the baby is born, surgery will be needed to place the abdominal

organs inside the baby’s body and repair the defect.

• If the gastroschisis defect is small (only some of the intestine is outside of

the belly), it is usually treated with surgery soon after birth to put the

organs back into the belly and close the opening.

• If the gastroschisis defect is large (many organs outside of the belly), the

repair might done slowly, in stages.

• The exposed organs might be covered with a special material and slowly

moved back into the belly. After all of the organs have been put back in the

belly, the opening is closed.

• Babies with gastroschisis often need other treatments as well, including

receiving nutrients through an IV line, antibiotics to prevent infection, and

careful attention to control their body temperature.

INTESTINAL OBSTRUCTION

• Intestinal obstruction is a partial or complete blockage of the bowel.

• The contents of the intestine cannot pass through it.

• If canalization of the intestine does not occur in utero at some point

in the bowel, an atresia (complete closure) or stenosis (narrowing) of

the fetal bowel can develop.

• The most common site of this occurrence is in the duodenum.

Causes

Obstruction of the bowel may due to:

• A mechanical cause, which means something is in the way

• Ileus, a condition in which the bowel does not work correctly, but there

is no structural problem causing it

Paralytic ileus, also called pseudo-obstruction, is one of the major causes of

intestinal obstruction in infants and children. Causes of paralytic ileus may

include:

• Bacteria or viruses that cause intestinal infections (gastroenteritis)

• Chemical, electrolyte, or mineral imbalances (such as decreased

potassium levels)

• Complications of abdominal surgery

• Decreased blood supply to the intestines (mesenteric ischemia)

• Infections inside the abdomen, such as appendicitis

• Kidney or lung disease

• Use of certain medicines, especially narcotics

Mechanical causes of intestinal obstruction may include:

• Adhesions or scar tissue that forms after surgery

• Foreign bodies (objects that are swallowed and block the

intestines)

• Gallstones (rare)

• Hernias

• Impacted stool

• Intussusception (telescoping of one segment of bowel into

another)

• Tumors blocking the intestines

• Volvulus (twisted intestine)

Symptoms

• Abdominal swelling (distention)

• Abdominal fullness, gas

• Abdominal pain and cramping

• Breath odor

• Constipation

• Diarrhea

• Inability to pass gas

• Vomiting

Diagnosis

• During a physical exam, the health care provider may find bloating,

tenderness, or hernias in the abdomen.

• Tests that show obstruction include:

• Abdominal CT scan

• Abdominal x-ray

• Barium enema

• Upper GI and small bowel series

Management

• Treatment involves placing a tube through the nose into the stomach

or intestine. This is to help relieve abdominal swelling (distention) and

vomiting.

• Volvulus of the large bowel may be treated by passing a tube into the

rectum.

• Surgery may be needed to relieve the obstruction if the tube does not

relieve the symptoms. It may also be needed if there are signs of

tissue death.

MECONIUM ILEUS

• Meconium is the first stool (bowel movement) that a newborn has.

• This stool is very thick and sticky.

• Meconium ileus is a bowel obstruction that occurs when the

meconium in baby’s intestine is even thicker and stickier than normal

meconium, creating a blockage in a part of the small intestine called

the ileum.

• Most infants with meconium ileus have a disease called cystic fibrosis.

• Meconium is the material found in the intestine in a newborn.

• It consists of succus entericus that is made up of bile salts, bile acids,

and debris that is shed from the intestinal mucosa during intrauterine

life.

• It is normally evacuated within 6 hours after birth or sooner in utero

as a result of a vagal response to perinatal stress.

• Normally, meconium is invisible on a radiograph. It occasionally has a

mottled appearance on abdominal radiographs during the first 2 days

of life. By convention, 4 GI conditions have the term meconium in

their name: meconium ileus, meconium ileus–equivalent syndrome,

meconium peritonitis, and meconium plug syndrome.

• Meconium ileus

In meconium ileus, low or distal intestinal obstruction results from the impaction of thick, tenacious

meconium in the distal small bowel. In addition, complications such as ileal atresia or stenosis, ileal

perforation, meconium peritonitis, and volvulus with or without pseudocyst formation can occur in association

with meconium ileus

• Meconium peritonitis

Meconium peritonitis may be incidentally detected on abdominal radiographs. Clinically, patients may

present because of bowel obstruction caused by fibroadhesive bands, which are the result of the inflammatory

peritoneal reaction. The bowel itself may be intact, with the perforation having healed, but bowel atresias are

often found in association. If the processus vaginalis is patent at the time the perforation occurs, calcification

or hernias may involve the scrotum. Ascites may also be present.

• Meconium ileus–equivalent syndrome

The condition is important, as it can be the presenting feature of cystic fibrosis in childhood and even

in early adult life. Moreover, the operative mortality and morbidity rates are high. Recurrent bowel obstruction

(which is often correlated with poor compliance with medication for cystic fibrosis) may manifest as recurrent

colicky abdominal pain, often in the right upper quadrant. In the older infant or child, chronic constipation can

be a problem, and intestinal obstruction can occur secondary to fecal impaction. These patients may also

present with intussusceptions.

• Meconium plug syndrome

Functional colonic obstruction in the full-term neonate is another name for meconium plug

syndrome. Although this abnormality is found mostly in term infants, Mees et al reported that 3 of their 4

patients were premature. Most infants with this form of colonic obstruction present within their first 24-36

hours of life. Findings include abdominal distention, bilious vomiting, and failure to initiate the normal passage

of meconium

Diagnosis

• The earliest signs of meconium ileus are abdominal distention (a

swollen belly), bilious (green) vomit and no passage of meconium.

• The doctor will order an X-ray of abdomen to find out if there is

meconium in the intestines.

Management

• If a doctor suspects that the child has a meconium ileus, the child

won't be given anything to eat or drink and will be fed through an

intravenous (IV) line, a small tube that's inserted into a vein.

• A small tube — called a nasogastric (NG) tube — will also be placed

through the child's nose and passed into the stomach to help remove

excess air and fluid.

• The medical team may try to break up the meconium blockage with

medicines given to the child through an enema. If the medicine

doesn't break up the meconium, there is a need for surgery.

• If the baby needs surgery for meconium ileus, the baby have a bowel

resection and ileostomy placement.

• Bowel resection surgery

• The child may need a bowel resection, a surgical procedure that

brings part of the small intestine out to the surface of the abdominal

wall. This creates an ileostomy, which is temporary. The bowel can be

reconnected once the child's ileus is gone.

DIAPHRAGMATIC HERNIA

• A protrusion of an abdominal organ (usually the stomach or intestine)

through a defect in the diaphragm into the chest cavity.

• This usually occurs on the left side, causing cardiac displacement of

the chest and collapse of the left lung.

• A diaphragmatic hernia is a birth defect in which there is an abnormal

opening in the diaphragm. The diaphragm is the muscle between the

chest and abdomen that helps you breathe.

• The opening allows part of the organs from the belly (stomach,

spleen, liver, and intestines) to go up into the chest cavity near the

lungs.

Causes

• A diaphragmatic hernia is a rare defect that occurs while the baby is

developing in the womb.

• The abdominal organs, such as the stomach, small intestine, spleen,

part of the liver, and the kidney, may take up part of the chest cavity.

This prevents the lung from growing normally.

• It is more common on the left side. Having a parent or sibling with the

condition slightly increases your risk.

Symptoms

• Severe breathing problems almost always develop shortly after the

baby is born. This is due in to poor movement of the diaphragm

muscle crowding of the lung tissue. This causes the lung to collapse.

• Other symptoms include:

• Bluish colored skin due to lack of oxygen

• Rapid breathing (tachypnea)

• Fast heart rate (tachycardia)

Diagnosis

• The pregnant mother may have a large amount of amniotic fluid.

Fetal ultrasound may show abdominal organs in the chest cavity.

• An exam of the infant shows:

• Irregular chest movements

• Lack of breath sounds on side with the hernia

• Bowel sounds that are heard in the chest

• Abdomen that feels less full when touched

• A chest x-ray may show abdominal organs in chest cavity

Management

• A diaphragmatic hernia repair is an emergency that requires surgery.

Surgery is done to place the abdominal organs into the proper

position and repair the opening in the diaphragm.

• The infant will need breathing support during the recovery period.

Some infants are placed on a heart/lung bypass machine. This gives

the lungs a chance to recover and expand after surgery.

• If a diaphragmatic hernia is diagnosed during pregnancy (around 24

to 28 weeks), fetal surgery may be an option.

UMBILICAL HERNIA

• An umbilical hernia is an outward bulging (protrusion) of the

lining of the abdomen or part of the abdominal

organ(s) through the area around the belly button.

Causes

• An umbilical hernia in an infant occurs when the muscle

through which the umbilical cord passes does not close

completely after birth.

• Umbilical hernias are common in infants. They occur slightly

more often in African Americans.

• Most umbilical hernias are not related to disease. Some

umbilical hernias are linked with rare conditions such as

Down syndrome.

Symptoms

• A hernia can vary in width from less than 1 centimeter to more than 5

centimeters.

• There is a soft swelling over the belly button that often bulges when

the baby sits up, cries, or strains.

• The bulge may be flat when the infant lies on the back and is quiet.

• Umbilical hernias are usually painless.

Diagnosis

• A hernia is usually found by the doctor during a physical

exam.

Management

• Most hernias in children heal on their own. Surgery to repair

the hernia is needed only in the following cases:

• The hernia does not heal after the child is 3 or 4 years old.

• The intestine or other tissue bulges out and loses its blood

supply (becomes strangulated).

• This is an emergency that needs surgery right away.

IMPERFORATE ANUS

• Imperforate anus is a defect that is present from birth

(congenital).

• The opening to the anus is missing or blocked.

• The anus is the opening to the rectum through which stools

leave the body.

Causes

• Imperforate anus may occur in several forms.

• The rectum may end in a pouch that does not connect with the colon.

• The rectum may have openings to other structures. These may

include the urethra, bladder, base of the penis or scrotum in boys, or

vagina in girls.

• There may be narrowing (stenosis) of the anus or no anus.

• The problem rare. It is caused by abnormal development of the fetus.

Many forms of imperforate anus occur with other birth defects.

Symptoms

• Anal opening very near the vagina opening in girls

• Baby does not pass first stool within 24 - 48 hours after birth

• Missing or moved opening to the anus

• Stool passes out of the vagina, base of penis, scrotum, or urethra

• Swollen belly area

Diagnosis

• A doctor can diagnose this condition during a physical exam.

Imaging tests may be recommended.

Management

• The infant should be checked for other problems, such as

abnormalities of the genitals, urinary tract, and spine.

• Surgery to correct the defect is needed.

• If the rectum connects with other organs, these organs will

also need to be repaired.

• A temporary colostomy (connecting the end of the large

intestine to the abdomen wall so that stool can be collected

in a bag) is often needed.

You might also like

- Abdominal Wall DefectsDocument5 pagesAbdominal Wall DefectsS GNo ratings yet

- Gastric Outlet Obstruction, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandGastric Outlet Obstruction, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Small and Lrge Intestine Pathology SuufiDocument78 pagesSmall and Lrge Intestine Pathology Suufiahmed mahamedNo ratings yet

- Congenital Anomalies of GiDocument94 pagesCongenital Anomalies of GiPadmaNo ratings yet

- physiology8weekDocument16 pagesphysiology8weekAnshulNo ratings yet

- Hernia: Under Supervision DR Arzak SaberDocument32 pagesHernia: Under Supervision DR Arzak Sabermathio medhatNo ratings yet

- Dr. Al-Ghanemi's Guide to Nausea and Vomiting in ChildrenDocument50 pagesDr. Al-Ghanemi's Guide to Nausea and Vomiting in ChildrenyusufharkianNo ratings yet

- Problem 5 GIT Josephine AngeliaDocument40 pagesProblem 5 GIT Josephine AngeliaAndreas AdiwinataNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Wall Defects: Omphalocele and Gastroschisis: DR - Enono Yhoshu Department of Pediatric SurgeryDocument42 pagesAbdominal Wall Defects: Omphalocele and Gastroschisis: DR - Enono Yhoshu Department of Pediatric SurgeryYogi drNo ratings yet

- Gastric DisordersDocument135 pagesGastric DisordersEsmareldah Henry SirueNo ratings yet

- Esophageal ObstructionDocument18 pagesEsophageal ObstructionArun Murali50% (2)

- C. Disorders of The Lowel BowelDocument69 pagesC. Disorders of The Lowel BowelJmarie Brillantes PopiocoNo ratings yet

- Acute Abdominal Pain in Children: Causes, Symptoms, DiagnosisDocument24 pagesAcute Abdominal Pain in Children: Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosisabdalmajeed alshammaryNo ratings yet

- HirschsprungDocument4 pagesHirschsprungMrmonstrosityNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Wall Defects PresentationDocument45 pagesAbdominal Wall Defects PresentationWasswaNo ratings yet

- INTESTINEDocument98 pagesINTESTINEDeepika LingamNo ratings yet

- hirschsprung diseaseDocument28 pageshirschsprung diseaseJils SureshNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Pain and Vomiting in ChildrenDocument18 pagesAbdominal Pain and Vomiting in ChildrenSimon Ganesya RahardjoNo ratings yet

- Cleft Lip and Palate Guide: Causes, Treatment and MoreDocument116 pagesCleft Lip and Palate Guide: Causes, Treatment and MoremeleseNo ratings yet

- Intestinal Malrotation and VolvulusDocument14 pagesIntestinal Malrotation and VolvulusSaf Tanggo Diampuan100% (1)

- Pyloric StenosisDocument16 pagesPyloric StenosisHelen McClintockNo ratings yet

- Hirchsprung Disease: A.K.A. Congenital AganglionicDocument29 pagesHirchsprung Disease: A.K.A. Congenital Aganglionicdesh_dacanayNo ratings yet

- Omphalocele: 1 Baskaran NDocument5 pagesOmphalocele: 1 Baskaran Nதாசன் தமிழன்No ratings yet

- No Bowel Output in NeonatesDocument24 pagesNo Bowel Output in NeonatesOTOH RAYA OMARNo ratings yet

- Projectile Vomiting in Infants: Understanding Pyloric StenosisDocument66 pagesProjectile Vomiting in Infants: Understanding Pyloric StenosisNITHA KNo ratings yet

- Evaluation and Management of Neonatal EmesisDocument34 pagesEvaluation and Management of Neonatal EmesisVasishta NadellaNo ratings yet

- Everything You Need to Know About Ulcerative ColitisDocument12 pagesEverything You Need to Know About Ulcerative Colitisquidditch07No ratings yet

- Gastro - NelsonDocument14 pagesGastro - NelsonGemma OrquioNo ratings yet

- Meckel's Diverticulum DR SuryaDocument30 pagesMeckel's Diverticulum DR SuryaHorakhty PrideNo ratings yet

- Gastroschizis Vs OmfalocelDocument35 pagesGastroschizis Vs OmfalocelElena LicsandruNo ratings yet

- Congenital Development Disorder of Esophagus, Stomach, Duodenum, Abdomen Wall, Anus and RectumDocument56 pagesCongenital Development Disorder of Esophagus, Stomach, Duodenum, Abdomen Wall, Anus and RectumSarah Nabella PutriNo ratings yet

- Chapter 28 Child With A Gastrointestinal ConditionDocument85 pagesChapter 28 Child With A Gastrointestinal Conditionsey_scottNo ratings yet

- Concept of Elimination-1Document39 pagesConcept of Elimination-1kalimulallah4No ratings yet

- Imperforate AnusDocument24 pagesImperforate AnusGrace EspinoNo ratings yet

- Surgery - Pediatric GIT, Abdominal Wall, Neoplasms - 2014ADocument14 pagesSurgery - Pediatric GIT, Abdominal Wall, Neoplasms - 2014ATwinkle SalongaNo ratings yet

- Omphalocelevsgastroschisis 160810122732Document23 pagesOmphalocelevsgastroschisis 160810122732LNICCOLAIO100% (1)

- Paralytic IleusDocument2 pagesParalytic Ileusrjalavazo100% (2)

- Foreign Body Ingestion: Leano, Fides Beatrice D.LDocument29 pagesForeign Body Ingestion: Leano, Fides Beatrice D.L3sshhhNo ratings yet

- Intussusception: Awan RochaniawanDocument13 pagesIntussusception: Awan Rochaniawan4wanRNo ratings yet

- Imperforate AnusDocument17 pagesImperforate AnusNalzaro Emyril100% (1)

- Inginal HerniaDocument6 pagesInginal HerniamohammedrubyNo ratings yet

- Anorectal Malformations HandoutDocument4 pagesAnorectal Malformations HandoutShikha Acharya100% (1)

- Intussuscept ION: in The Paediatric PatientDocument30 pagesIntussuscept ION: in The Paediatric PatientSuneil R AlsNo ratings yet

- Meconium plug syndrome causes and treatmentDocument3 pagesMeconium plug syndrome causes and treatmentGlen Jacobs SumadihardjaNo ratings yet

- CancerDocument30 pagesCancerAbhirami BabuNo ratings yet

- Abdominal ExaminationDocument22 pagesAbdominal ExaminationDARK WATCHERNo ratings yet

- Esophageal DiverticulaDocument18 pagesEsophageal DiverticulaAbigail BascoNo ratings yet

- Case Study For Diverticular DiseaseDocument4 pagesCase Study For Diverticular DiseaseGabbii CincoNo ratings yet

- Anorectal MalformationsDocument24 pagesAnorectal MalformationsVaishali SinghNo ratings yet

- GI DisordersDocument42 pagesGI Disordersvarshasharma05No ratings yet

- HerniaDocument24 pagesHerniaSalman HabeebNo ratings yet

- Anorectal MalformationDocument11 pagesAnorectal MalformationNazurah AzmiraNo ratings yet

- Case Study Presented by Group 22 BSN 206: In-Depth View On CholecystectomyDocument46 pagesCase Study Presented by Group 22 BSN 206: In-Depth View On CholecystectomyAjiMary M. DomingoNo ratings yet

- Gastro SCH Is IsDocument14 pagesGastro SCH Is IsFloriejane MarataNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care of The Child With Gastrointestinal DisordersDocument50 pagesNursing Care of The Child With Gastrointestinal Disordersمهند الرحيليNo ratings yet

- APSA Gastroschisis Brochure FNLDocument5 pagesAPSA Gastroschisis Brochure FNLFarzana AhmedNo ratings yet

- CELIAC DISEASE, Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis, AchalasiaDocument6 pagesCELIAC DISEASE, Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis, Achalasiasophisticated_kim09No ratings yet

- What Is Intestinal MalrotationDocument10 pagesWhat Is Intestinal MalrotationNathan BlackwellNo ratings yet

- NCM 107 Leadership and Management RLEDocument4 pagesNCM 107 Leadership and Management RLEJobelle AcenaNo ratings yet

- Geriatric Case StudyDocument15 pagesGeriatric Case StudyJobelle AcenaNo ratings yet

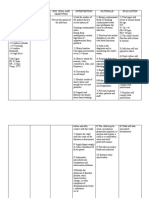

- Assessment Nursing Diagnosis Inference Objectives Nursing Intervention Rationale Evaluation Short Term Goal Independent: Short Term GoalDocument5 pagesAssessment Nursing Diagnosis Inference Objectives Nursing Intervention Rationale Evaluation Short Term Goal Independent: Short Term GoalJobelle AcenaNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Case StudyDocument21 pagesPediatric Case StudyJobelle AcenaNo ratings yet

- Date/Schedule Activities Expected Output Verified/Checked by Area in ChargeDocument2 pagesDate/Schedule Activities Expected Output Verified/Checked by Area in ChargeJobelle AcenaNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument10 pagesCase StudyJobelle AcenaNo ratings yet

- Case Study (ACS)Document12 pagesCase Study (ACS)Kristel Joy Cabarrubias Acena100% (1)

- Union Christian College School of Health and Sciences City of San Fernando La UnionDocument11 pagesUnion Christian College School of Health and Sciences City of San Fernando La UnionJobelle AcenaNo ratings yet

- NCM 107 SY 2020-2021: Legal and Ethical Consideration of Euthanasia in India: A Choice Between Life and DeathDocument8 pagesNCM 107 SY 2020-2021: Legal and Ethical Consideration of Euthanasia in India: A Choice Between Life and DeathJobelle AcenaNo ratings yet

- GC ncp1Document2 pagesGC ncp1Jobelle AcenaNo ratings yet

- DRUG STUDY (Lung Cancer)Document10 pagesDRUG STUDY (Lung Cancer)Jobelle AcenaNo ratings yet

- GC ncp1 and 2Document4 pagesGC ncp1 and 2Jobelle AcenaNo ratings yet

- Difference Between Mechanism of Action of Cell Mediated Immune System and Humoral Mediated Immune SystemDocument4 pagesDifference Between Mechanism of Action of Cell Mediated Immune System and Humoral Mediated Immune SystemJobelle AcenaNo ratings yet

- Assessment Nursing Diagnosis Inference Objectives Nursing Intervention Rationale EvaluationDocument10 pagesAssessment Nursing Diagnosis Inference Objectives Nursing Intervention Rationale EvaluationJobelle Acena100% (2)

- Subjective: Ventilation AssistanceDocument3 pagesSubjective: Ventilation AssistanceJobelle Acena100% (2)

- Normal Cell GrowthDocument5 pagesNormal Cell GrowthJobelle AcenaNo ratings yet

- PHARMAfdDocument7 pagesPHARMAfdJobelle AcenaNo ratings yet

- Case Study (Lung Cancer)Document17 pagesCase Study (Lung Cancer)Jobelle Acena100% (1)

- Online LectureDocument9 pagesOnline LectureJobelle AcenaNo ratings yet

- Er Drugs StudyDocument80 pagesEr Drugs StudyJobelle AcenaNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plans for Fever, Wound Healing and Pressure UlcerDocument11 pagesNursing Care Plans for Fever, Wound Healing and Pressure UlcerJobelle AcenaNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Tests Guide for NursesDocument2 pagesDiagnostic Tests Guide for NursesBenedict AlvarezNo ratings yet

- SummaryDocument1 pageSummaryJobelle AcenaNo ratings yet

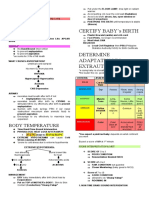

- Certify Baby'S Birth: Body TemperatureDocument9 pagesCertify Baby'S Birth: Body TemperatureJobelle Acena100% (1)

- Notes On Obstetrics: Normal Labor (Theories of Labor Onset)Document22 pagesNotes On Obstetrics: Normal Labor (Theories of Labor Onset)Jobelle Acena100% (1)

- Psychiatric Nursing Michael Jimenez, PENTAGON Slovin'S Formula: N 1 + NeDocument10 pagesPsychiatric Nursing Michael Jimenez, PENTAGON Slovin'S Formula: N 1 + NeJobelle AcenaNo ratings yet

- ER Protocols in The PhilippinesDocument9 pagesER Protocols in The PhilippinesJobelle Acena100% (1)

- Bioethics in Nursing Practice: Principles of Autonomy and Informed ConsentDocument5 pagesBioethics in Nursing Practice: Principles of Autonomy and Informed ConsentVhinny Macabontoc100% (1)

- Nursing: Core Values of NursingDocument14 pagesNursing: Core Values of NursingJobelle AcenaNo ratings yet

- Anti Psychotic DrugsDocument2 pagesAnti Psychotic DrugscalfornianursingacadNo ratings yet

- ACSM Position Stand - Exercise and Fluid Replacement - Medicine & Science in Sports & ExerciseDocument7 pagesACSM Position Stand - Exercise and Fluid Replacement - Medicine & Science in Sports & ExerciseDiógenes OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Science Investigatory ProjectDocument25 pagesScience Investigatory ProjectMigs Jaudian100% (1)

- Targocid PI - NewDocument4 pagesTargocid PI - NewDR JAMAL WARISNo ratings yet

- Shoulder RehabDocument29 pagesShoulder Rehabmanarpt100% (4)

- PMAD PresentationDocument17 pagesPMAD PresentationBrittany100% (1)

- Contraception in DiabetesDocument36 pagesContraception in DiabetesbhartihospitalNo ratings yet

- Tooth Morphology and Access Cavity PreparationDocument232 pagesTooth Morphology and Access Cavity Preparationusmanhameed8467% (3)

- Data Pasien TB JuliDocument42 pagesData Pasien TB JuliTsubbatun NajahNo ratings yet

- 2009 Annual ReportDocument12 pages2009 Annual ReportWSCFoundationNo ratings yet

- Actinic KeratosisDocument19 pagesActinic KeratosisDajour CollinsNo ratings yet

- U On PG Prospectus 2013Document94 pagesU On PG Prospectus 2013jesusgameboyNo ratings yet

- List of Teaching StaffDocument10 pagesList of Teaching StaffGaurav SinghNo ratings yet

- MRCS Part B OSCEDocument117 pagesMRCS Part B OSCEMuhammadKhawar100% (1)

- Imagination and DNADocument5 pagesImagination and DNAdextromeNo ratings yet

- AMEBIASISDocument19 pagesAMEBIASISDika Herza Pratama100% (1)

- Hidden Covert, Chemical Torture With FlourideDocument4 pagesHidden Covert, Chemical Torture With FlourideViktoriaNo ratings yet

- Relert Tablets: 1. Qualitative and Quantitative CompositionDocument9 pagesRelert Tablets: 1. Qualitative and Quantitative Compositionddandan_2No ratings yet

- Honoring graduates and sharing life lessonsDocument5 pagesHonoring graduates and sharing life lessonsamitm17No ratings yet

- Plasticity in The Visual System - From Genes To Circuits - R. PinaudDocument366 pagesPlasticity in The Visual System - From Genes To Circuits - R. PinaudEliMihaelaNo ratings yet

- Qi Project PaperDocument8 pagesQi Project Paperapi-380333919No ratings yet

- Kinesio InfoGuide 2013 PDFDocument12 pagesKinesio InfoGuide 2013 PDFCésar Luís Bueno GonçalvesNo ratings yet

- How Fast Food Affects Thai Teenagers LifeDocument15 pagesHow Fast Food Affects Thai Teenagers Lifeapi-263388641No ratings yet

- Breath of FireDocument3 pagesBreath of FirepraveenmspkNo ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument2 pagesAnnotated BibliographyKevin JohnsenNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7Document34 pagesChapter 7Hima AlqahtaniNo ratings yet

- MEDI7241 How To Write A Research Protocol TutorialDocument7 pagesMEDI7241 How To Write A Research Protocol TutorialJazradelNo ratings yet

- History of OrthodonticsDocument133 pagesHistory of OrthodonticsAnubha VermaNo ratings yet

- AdhdDocument16 pagesAdhdCristina Badenas de CoaNo ratings yet

- Medfield PharmaceuticalsDocument17 pagesMedfield PharmaceuticalsSreya De100% (1)

- Seamless Care - DR SH LeungDocument38 pagesSeamless Care - DR SH Leungmalaysianhospicecouncil6240No ratings yet