Professional Documents

Culture Documents

18th Century Politics and Parliamentary Sovereignty

Uploaded by

Alex NF0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

16 views6 pagesThe 18th century was a prosperous time for Britain and its colonies as Britain became the dominant global power through wars against other European powers. Britain's North American colonies saw rapid population and economic growth from 250,000 to nearly 3 million inhabitants. Parliamentary sovereignty was established after the Glorious Revolution, consolidating power in the House of Commons. However, electoral corruption was rampant, with many seats effectively controlled by aristocratic landowners who could sell seats or direct how constituents voted. Reform efforts faced resistance but the 1832 Reform Act abolished some rotten boroughs and expanded the electorate, though a wealthy elite still dominated politically.

Original Description:

Owow

Original Title

Politics in the 18th Century

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe 18th century was a prosperous time for Britain and its colonies as Britain became the dominant global power through wars against other European powers. Britain's North American colonies saw rapid population and economic growth from 250,000 to nearly 3 million inhabitants. Parliamentary sovereignty was established after the Glorious Revolution, consolidating power in the House of Commons. However, electoral corruption was rampant, with many seats effectively controlled by aristocratic landowners who could sell seats or direct how constituents voted. Reform efforts faced resistance but the 1832 Reform Act abolished some rotten boroughs and expanded the electorate, though a wealthy elite still dominated politically.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

16 views6 pages18th Century Politics and Parliamentary Sovereignty

Uploaded by

Alex NFThe 18th century was a prosperous time for Britain and its colonies as Britain became the dominant global power through wars against other European powers. Britain's North American colonies saw rapid population and economic growth from 250,000 to nearly 3 million inhabitants. Parliamentary sovereignty was established after the Glorious Revolution, consolidating power in the House of Commons. However, electoral corruption was rampant, with many seats effectively controlled by aristocratic landowners who could sell seats or direct how constituents voted. Reform efforts faced resistance but the 1832 Reform Act abolished some rotten boroughs and expanded the electorate, though a wealthy elite still dominated politically.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 6

THE POLITICS IN THE 18TH CENTURY

PROSPERITY AND GROWTH

The Eighteenth Century was a very prosperous time for

Britain and its overseas colonies. It was in this period that

the United Kingdom of Great Britain became the

dominant global maritime power. Britain gained this new

power in part by fighting many wars against other

European colonial powers, including Spain, the

Netherlands, and especially France. Despite these wars,

the eighteenth century was particularly prosperous for

Britain’s colonies within the Atlantic coast’s temperate

zone, which later became the first thirteen U.S. states.

These colonies saw rapid growth in both population and

economy, growing from about 250,000 inhabitants in

1700 to close to three million by the outbreak of the

American Revolution in 1775–when Britain’s own

population was only about nine million. This context of

prosperity may help to explain why almost all politically

active Americans remained loyal, patriotic British subjects

until about 1765, when the Revolutionary period began.

PARLIAMENTARY SOVEREIGNTY

After the Glorious Revolution of 1689, the

balance of power in England’s

parliamentary monarchy tipped definitively

away from the king and towards

Parliament. While Parliament only

gradually came to exercise the full powers

it had acquired in 1689, by the mid-1700s

there was no longer any doubt that

Britain’s government was characterized by

“Parliamentary sovereignty,” or the rule of

Parliament. In practice this meant the rule

of Parliament’s more powerful “lower”

house, the House of Commons. In this

system, both the House of Lords and the

king and the various agencies of the royal

bureaucracy continued to play important

roles. But real power–for example over

both legislation and taxation–now lay with

the House of Commons.

BRIBERY AND CORRUPTION

This electorate expected to be bribed. The going rate for even a ‘cheap’

constituency was £5 a vote, plus copious food and (especially) drink. The

politician-playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s expenses for election in

Stafford in 1780 were over £1,000.

At least in Stafford the electors had some say in whom they voted for.

Many other constituencies were ‘pocket boroughs’, owned outright by a

major landowner. In such cases, the entire electorate were the

landowner’s tenants, obliged to vote (in a public ballot) as directed or

face eviction. In the 1760s, 205 of the 406 English constituencies were

controlled by just 111 aristocratic owners.

If not wanted for a relative, seats could be sold to the highest acceptable

bidder. A single nomination could cost £9,000; the permanent purchase

of a constituency, and with it the ongoing right to nominate its two MPs,

cost much more. In 1802 Old Sarum in Wiltshire reputedly changed

hands for £60,000.

Old Sarum was the most notorious of the 56 so-called ‘rotten boroughs’,

places whose right to return MPs extended back to the Middle Ages, but

which were almost completely depopulated by Georgian times.

Meanwhile the people of the rapidly expanding new towns, such as

Manchester, had no direct parliamentary representation at all.

REFORM

Influential figures long accepted this system, partly because they

themselves relied upon aristocratic patronage. Growing agitation for reform

was hampered by the French Revolution and the subsequent wars with

France (1793–1815). Critics were marginalised or silenced, and regarded

as at best unpatriotic, at worst dangerous revolutionaries.

A slender majority of the political establishment, however, recognised that

some degree of change was required to stave off revolution.

In 1832, after two years of parliamentary manoeuvring and opposition from

the Duke of Wellington and the House of Lords, the first Reform Act for

England and Wales was passed. This abolished rotten and pocket boroughs

and created 135 new seats, giving 41 of the larger English towns their first

MPs.

The electorate was increased from about 400,000 to 650,000, about one in

six of the adult male population. Yet the beneficiaries were the richer middle

classes, rather than the great majority of working people. The ruling elite

had expanded, but an elite still ruled.

THANKS FOR WATCHING

Schiopu Sorin Paul

Cront Razvan

You might also like

- Fiche de Civilisation – the British Political SystemDocument22 pagesFiche de Civilisation – the British Political Systemtheo.gathelierNo ratings yet

- IdkidkDocument6 pagesIdkidkAna IosupNo ratings yet

- Brit Civ Lesson 5 Oct 2023Document4 pagesBrit Civ Lesson 5 Oct 2023mohamedabdesselembecharef879No ratings yet

- 1805) Is A High Point in British History - A Famous Victory, A Famous Tragedy, An Event That Everybody KnowsDocument8 pages1805) Is A High Point in British History - A Famous Victory, A Famous Tragedy, An Event That Everybody KnowsАня РалеваNo ratings yet

- Restoration and Eighteenth Century - Norton AnthologyDocument26 pagesRestoration and Eighteenth Century - Norton AnthologySilvia MinghellaNo ratings yet

- Culture 3Document131 pagesCulture 3كمونه عاطفNo ratings yet

- She - Unit-5Document13 pagesShe - Unit-5Eng Dpt Send Internal QuestionsNo ratings yet

- History of Britain 18-20 CenturyDocument33 pagesHistory of Britain 18-20 CenturyVivien HegedűsNo ratings yet

- The Stuarts. The Crown and ParliamentDocument3 pagesThe Stuarts. The Crown and ParliamentNatalia BerehovenkoNo ratings yet

- Mini Handbook Great BritainDocument17 pagesMini Handbook Great BritainEDGAR PAUL ARROGANTENo ratings yet

- English Novel of The 18 AND 19 Century: Karahasanović ArnesaDocument44 pagesEnglish Novel of The 18 AND 19 Century: Karahasanović ArnesaArnesa Džulan100% (1)

- What Was The English Revolution?: John Morrill, Brian Manning and David UnderdownDocument19 pagesWhat Was The English Revolution?: John Morrill, Brian Manning and David UnderdownAurinjoy BiswasNo ratings yet

- British Society & Politics in the 18th CenturyDocument48 pagesBritish Society & Politics in the 18th CenturySofia JuarezNo ratings yet

- British Country & Civilization Study: Some Important EventsDocument21 pagesBritish Country & Civilization Study: Some Important EventsVũ HoànNo ratings yet

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Britain from the English Civil War to the Glorious RevolutionFrom EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Britain from the English Civil War to the Glorious RevolutionNo ratings yet

- Sacbr w8Document5 pagesSacbr w8Elif Hilal ErdoganNo ratings yet

- History of GBDocument15 pagesHistory of GBLevindoNascimentoNo ratings yet

- British Democracy Evolution 1840-1940Document6 pagesBritish Democracy Evolution 1840-1940Teresa WalterNo ratings yet

- The Great Experiment-ReadingDocument5 pagesThe Great Experiment-ReadingT. McCaskillNo ratings yet

- Britain's 17th Century HistoryDocument11 pagesBritain's 17th Century HistoryNastya BeznoshchenkoNo ratings yet

- AN Open Letter To Whoever Wins The ElectionDocument15 pagesAN Open Letter To Whoever Wins The Electionjep9547100% (1)

- Tudor Parliaments Power Grew During 16th CenturyDocument5 pagesTudor Parliaments Power Grew During 16th CenturyMatias BNo ratings yet

- Activities AncienregimeDocument4 pagesActivities AncienregimeMiquel VialNo ratings yet

- Features of Victorian AgeDocument4 pagesFeatures of Victorian AgeM Ans AliNo ratings yet

- CH 31 The French Revolution and The Empire of NapoleonDocument22 pagesCH 31 The French Revolution and The Empire of NapoleonAli MNo ratings yet

- Popa AndreiDocument13 pagesPopa Andreiandrei.popa7No ratings yet

- Class 106Document18 pagesClass 106Ashiful IslamNo ratings yet

- The Great Britain in The 18th CenturyDocument12 pagesThe Great Britain in The 18th CenturyVicentiu Iulian Savu100% (1)

- French RevolutionDocument21 pagesFrench RevolutionMehdi ShahNo ratings yet

- Proiect Civilizatie BritanicaDocument10 pagesProiect Civilizatie BritanicaCriss AlexandruNo ratings yet

- Homework:: Textbook: Interpretations of American History Read Chapter 4Document51 pagesHomework:: Textbook: Interpretations of American History Read Chapter 4Henry ChaoNo ratings yet

- WHY NATIONS FAIL Chapter 4 (Summary and Reflections)Document15 pagesWHY NATIONS FAIL Chapter 4 (Summary and Reflections)Jobanie BolotoNo ratings yet

- English Revolution and Various InterpretationsDocument8 pagesEnglish Revolution and Various Interpretationsayush100% (1)

- 4 - French Revolution PowerPoint NotesDocument120 pages4 - French Revolution PowerPoint NotesJulie PagleyNo ratings yet

- Arrogante - Bsse III-8 - Handbook PartDocument15 pagesArrogante - Bsse III-8 - Handbook PartEDGAR PAUL ARROGANTENo ratings yet

- Chapter IDocument8 pagesChapter IMLP Twilight TwinkleNo ratings yet

- 8A A Brief History of The British ParliamentDocument5 pages8A A Brief History of The British ParliamentNuria Paillissé VilanovaNo ratings yet

- England and France in the 18th Century: A Study of Political and Industrial DevelopmentsDocument18 pagesEngland and France in the 18th Century: A Study of Political and Industrial DevelopmentsNicoleta-Mariana GoiaNo ratings yet

- First Lecture: Empire, Modernization, Progress and Dickens's Humorous Critique in Bleak HouseDocument7 pagesFirst Lecture: Empire, Modernization, Progress and Dickens's Humorous Critique in Bleak HouseRoxanneNo ratings yet

- William of Orange and the Fight for the Crown of England: The Glorious RevolutionFrom EverandWilliam of Orange and the Fight for the Crown of England: The Glorious RevolutionNo ratings yet

- House of Hanover (1714-1901) : George IDocument8 pagesHouse of Hanover (1714-1901) : George IPilar Palma del PasoNo ratings yet

- Causes of the French Revolution ExplainedDocument5 pagesCauses of the French Revolution ExplainedNicolás Gaviria0% (1)

- Political Life in Britain: Colegiul Național "Silvania"Document18 pagesPolitical Life in Britain: Colegiul Național "Silvania"Elda CenterNo ratings yet

- Assignment 3 The Glorious RevolutionDocument4 pagesAssignment 3 The Glorious RevolutionVictoria FajardoNo ratings yet

- The Atlantic RevolutionsDocument9 pagesThe Atlantic RevolutionshelenaNo ratings yet

- The Development of Modern Europe Volume II: From the Fall of Metternich to the Eve of World War IFrom EverandThe Development of Modern Europe Volume II: From the Fall of Metternich to the Eve of World War INo ratings yet

- POLITICAL SYSTEM of UKDocument27 pagesPOLITICAL SYSTEM of UKMahtab HusaainNo ratings yet

- PARTE STORICA IngleseDocument10 pagesPARTE STORICA Ingleseeleonora olivieriNo ratings yet

- The History of the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars (1789-1815)From EverandThe History of the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars (1789-1815)No ratings yet

- The French Revolution ExplainedDocument52 pagesThe French Revolution ExplainedRaman BiswalNo ratings yet

- Tudor ParliamentDocument3 pagesTudor ParliamentNuñez Gimena RocioNo ratings yet

- Story of Medieval England (Starter)Document3 pagesStory of Medieval England (Starter)Ivan HermitNo ratings yet

- The Romantic AgeDocument4 pagesThe Romantic AgeMatthew GallagherNo ratings yet

- Letter in 10 Years From NowDocument2 pagesLetter in 10 Years From NowAlex NFNo ratings yet

- HackerDocument3 pagesHackerAlex NFNo ratings yet

- HackerDocument3 pagesHackerAlex NFNo ratings yet

- ClearDocument1 pageClearAlex NFNo ratings yet

- ClearDocument1 pageClearAlex NFNo ratings yet

- HackerDocument3 pagesHackerAlex NFNo ratings yet

- Centre RevendicareDocument100 pagesCentre RevendicareAlex NFNo ratings yet

- Centre RevendicareDocument100 pagesCentre RevendicareAlex NFNo ratings yet

- ClearDocument1 pageClearAlex NFNo ratings yet

- WowDocument14 pagesWowAlex NFNo ratings yet

- Read MeDocument1 pageRead MeAlex NFNo ratings yet

- For and Against EssayDocument1 pageFor and Against EssayAlex NFNo ratings yet

- Read MeDocument1 pageRead MeAlex NFNo ratings yet

- MelodiiDocument12 pagesMelodiiAlex NFNo ratings yet

- The Tudors: Project by Azamfirei Katherina Balanovici Anastasia Surubariu GeorgianaDocument13 pagesThe Tudors: Project by Azamfirei Katherina Balanovici Anastasia Surubariu GeorgianaAlex NFNo ratings yet

- Rifle Crosshair 2Document1 pageRifle Crosshair 2Alex NFNo ratings yet

- Society in 18th CenturyDocument11 pagesSociety in 18th CenturyAlex NF100% (1)

- Buckingham PalaceDocument8 pagesBuckingham PalaceAlex NFNo ratings yet

- The British Royal FamilyDocument15 pagesThe British Royal FamilyAlex NFNo ratings yet

- Election Law CasesDocument322 pagesElection Law CasesPaolo Sison GoNo ratings yet

- 83.development of Anti Rigging Voting System Using Finger PrintDocument4 pages83.development of Anti Rigging Voting System Using Finger PrintAmit Verma100% (1)

- Nigerian Political System: An AnalysisDocument8 pagesNigerian Political System: An AnalysisJustice WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Abilene Reflector ChronicleDocument8 pagesAbilene Reflector ChronicleARCEditorNo ratings yet

- Understanding Random Sampling ErrorDocument4 pagesUnderstanding Random Sampling ErrorChandra AndjarNo ratings yet

- Smart Voting System With Face RecognitionDocument3 pagesSmart Voting System With Face RecognitionInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Mason Dixon Poll On Recreational Pot InitiativeDocument6 pagesMason Dixon Poll On Recreational Pot InitiativePeter SchorschNo ratings yet

- Buenavista, MarinduqueDocument2 pagesBuenavista, MarinduqueSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- Final Judgment Denying Election ContestDocument36 pagesFinal Judgment Denying Election ContestHouston ChronicleNo ratings yet

- RA 8436 As AmendedDocument11 pagesRA 8436 As AmendedAldan Subion AvilaNo ratings yet

- Santa Maria, BulacanDocument2 pagesSanta Maria, BulacanSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- Reflection Paper - GonzalesC - 11981318Document2 pagesReflection Paper - GonzalesC - 11981318Celina GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Omnibus Election CodeDocument2 pagesOmnibus Election CodeKathNo ratings yet

- Bellarmine Political Review (Fall 2012)Document28 pagesBellarmine Political Review (Fall 2012)Bellarmine Political Review100% (1)

- Review of The Pennsylvania and Georgia 2020 Presidential Election ResultsDocument4 pagesReview of The Pennsylvania and Georgia 2020 Presidential Election ResultsJim Hoft80% (5)

- Board of Canvassers Minutes - August 4, 2020Document3 pagesBoard of Canvassers Minutes - August 4, 2020WWMTNo ratings yet

- Timeline of The Events Leading Up To Jan. 6 Insurgency ShowsDocument8 pagesTimeline of The Events Leading Up To Jan. 6 Insurgency ShowssiesmannNo ratings yet

- CREW: Governor Scott Walker: Regarding Dispatching of Wisconsin State Patrol: 4/18/11 - Keith Gilkes (Part 1a)Document148 pagesCREW: Governor Scott Walker: Regarding Dispatching of Wisconsin State Patrol: 4/18/11 - Keith Gilkes (Part 1a)CREWNo ratings yet

- Civilian Authority Supreme Over MilitaryDocument36 pagesCivilian Authority Supreme Over MilitaryKarla MontuertoNo ratings yet

- 10 Slogans That Changed India 23.8Document6 pages10 Slogans That Changed India 23.8amytbhatNo ratings yet

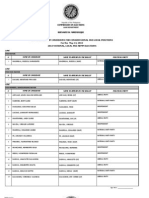

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Provincial Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocument2 pagesCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Provincial Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- Isabela - Mun DeleteDocument76 pagesIsabela - Mun DeleteireneNo ratings yet

- Election DigestDocument28 pagesElection DigestJoanna MarinNo ratings yet

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocument2 pagesCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- OH-Sen Anzalone Liszt Grove For The Ohio Education Association (Oct. 2016)Document7 pagesOH-Sen Anzalone Liszt Grove For The Ohio Education Association (Oct. 2016)Daily Kos ElectionsNo ratings yet

- LEADERS BEYOND MEDIA IMAGESDocument126 pagesLEADERS BEYOND MEDIA IMAGESgw bushNo ratings yet

- Epstein and O'Halloran - 1999 - Delegating Powers A Transaction Cost Politics AppDocument423 pagesEpstein and O'Halloran - 1999 - Delegating Powers A Transaction Cost Politics AppJosé Manuel MejíaNo ratings yet

- Annual Meeting Minutes SummaryDocument16 pagesAnnual Meeting Minutes SummaryMaureen Derial Panta100% (1)

- Institutional Models of Local Governance - Comparative AnalysisDocument10 pagesInstitutional Models of Local Governance - Comparative AnalysisANTHONY BALDICANASNo ratings yet

- CANICOSA VDocument4 pagesCANICOSA VrethiramNo ratings yet