Professional Documents

Culture Documents

FPA Challenges

Uploaded by

Ytfreemode2 20 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 views27 pagesForeign policy challenges

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentForeign policy challenges

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 views27 pagesFPA Challenges

Uploaded by

Ytfreemode2 2Foreign policy challenges

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 27

1

Challenges to Foreign Policy

Analysis

3

Introduction

Scholars engaged in foreign policy analysis (FPA)

have forged new paths of inquiry essential to

opening the black box of domestic politics and

policymaking in an effort to understand actor’s

choices in global politics. It is now broadly

accepted that different levels of analysis--individual

factors, inputs into the decision process, and

institutional as well as cultural and societal

factors--converge to shape foreign policy output

4

Important factor in FPA

1-Observing role of identity in foreign

2-How foreign policy provides the tools to

understand the world and how the future of FPA is

linked to what happens in the international and

domestic political setting.

3-The need for tolerance of different

methodological approaches within the analysis of

foreign policy.

4-Discussion of group dynamics

5-Crisis decision making

5

FPA more or less relevant post Cold War

The debates on the value of FPA has emerged as

a result of changes in the international system. On

the one hand, critics charge that post-Cold War

changes (that is, interdependence, the increasing

numbers of regional and international

organizations, and concern about global problems

and permanent membership in alliances) have

challenged the nature of the state and its ability to

forge foreign policy and have made the field less

relevant.

6

As Margot Light (1994:100) notes, "there is a

steady erosion of a separate concept of foreign

policy." On the other hand, some argue that these

same changes in the international system make

the study of foreign policy more significant.

7

One of the most disappointing features of

contemporary FPA is the relative dearth of

comparative studies. If a researcher wants to

investigate many of the traditional factors that

explain foreign policy-factors such as a state's

position in the international system, the role of

public opinion, political culture, state-society

relations, and the impact of governmental

organization-it is necessary to compare foreign

policies across time, space, and issues to

understand the general explanatory power of these

various influences on governments behaviour.

8

Policy questions demand this type of comparative

knowledge. In the international debate over policy

toward Iraq in late 2002 and early 2003, for example,

one underlying question was: "What explains the

French position as compared to the British position as

compared to the German position as compared to the

Turkish position?" The answers to this question were

central to an understanding of the origin and outcome of

the transatlantic division over policy toward Iraq.

Foreign policy analysts certainly have potential

responses to this question, but such inquiry has not

been the focus of recent research.

9

UN Security Council Resolution 1441, which on

November 8 gave Iraq a “final opportunity” to disarm,

passed in the Security Council by a vote of 15-0 and

was strongly endorsed two weeks later by a unanimous

NATO alliance—including France and Germany. At its

Prague summit, NATO allies not only claimed to “stand

united” in their commitment to implement 1441, but

announced the historic enlargement of the Alliance to

seven new members and the development of a rapid

reaction force that would enable member states to

conduct joint military operations abroad.

10

While no one pretended that U.S. and European views

of the Iraq crisis (or NATO’s potential role in it) were

identical, a basic agreement seemed to have been

reached—if Iraq willingly disarmed Washington would

forego regime change; if it did not, the United States

would lead a coalition to disarm Iraq by changing the

regime by force.

11

The current dispute arises from the interpretation of

those commitments. For the United States, the essence

of Resolution 1441 was voluntary Iraqi disarmament—

if Iraq failed to demonstrate that it was free of weapons

of mass destruction, the threat of “serious

consequences” meant the use of military force. Many

Europeans, on the other hand—including at least the

French, German, and Belgian governments—instead put

the emphasis on weapons inspections.

12

1441 contained no timetable for action, and that more

intrusive inspections, so long as they can be maintained,

remain a better approach than war. These European

governments seem to be making the case for an

enhanced form of containment, even though the

approach they accepted in 1441 appeared to be a choice

between genuine disarmament and war.

13

If these were just the views of a small number of European

governments—even including veto-wielding France and

current Security Council president Germany—it would not

pose the Bush Administration much of a problem. France and

Germany would be isolated and the United States could move

ahead to implement 1441 according to its own interpretation.

The problem, however, is that a vast majority of European

public opinion—around 82 percent according to recent polls—

along with key foreign governments like Russia and China,

shared the French and German perspective.

14

Possible reasons for not supporting US

• Two of the most commonly suggested explanations

for French and German policy:

• Commercial interests

• Anti-Americanism

15

British Prime Minister Tony Blair’s political need for

another UN Security Council resolution, antiwar

demonstrations by millions of European citizens, and

the unprecedented spectacle of an audience at the

Security Council greeting the French Foreign Minister’s

call for more time for inspections with applause, all

suggested that European opposition to use of force in

Iraq.

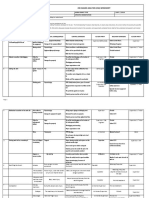

France German Turkey

1-France, which has also 1-Germany that suffered most 1-Europeans are therefore 16

experienced “war, occupation, from the devastation of World deeply skeptical that the

and barbarity,” as Foreign War II invasion of Iraq will produce

Minister Dominique de 2-If the next large terrorist the stable, liberated

Villepin reminded the Security attack takes place in a democracy that Americans

Council European capital of a country hope will prove a catalyst for

2-The second key factor is that supports the United democratization and reform

terrorism. Most Europeans States on Iraq—London, throughout the region

believe that a U.S.-led invasion Madrid, or Rome, for example 2-Turkey about the effects of

of an Arab country—with its —many Europeans may well an Iraq war, and stung by the

consequent civilian casualties blame American policy for criticism that it snubbed its

and likely need for a long-term having provoked the result. NATO allies during the

occupation—will more likely Afghanistan operation the

be a recruitment tool for Al previous year, the United

Qaeda than a blow against States in late 2002 asked NATO

terrorism. to consider planning for the

defense of Turkey in case of

retaliation by Iraq

3-Europeans, especially 3-Even if they support the goal 3-After a nearly three-month

France, for Iraq, Syria, of removing Saddam’s standoff, and a request by 17

Lebanon, and Palestine after dictatorial regime, they doubt Turkey itself under NATO’s

World War I—see little reason that Iraq’s ethnically divided consultation mechanism

to expect the project to be a population, artificial borders, Germany and Belgium finally

success based on their and unequally allocated agreed to let NATO plan for

colonial experience in the natural resources lend the deployment of air and

Arab world themselves to future stability, missile defense systems, and

and fear that disorder there chemical and biological

could prove disastrous for the weapons detection units to

entire Arab world Turkey

Challenges to FPA 18

The challenge for FPA will be to integrate ongoing

transformations in international political structures and

processes into theories regarding government

processes and individual behavior:

1- such, FPA will need to develop new understandings

regarding the nature of policymaking among the various

actors who create FP.

2- As for the international system, several overarching

future visions of world politics have come to dominate

popular intellectual discussion. Francis Fukuyama's

(1992) "End of History" view suggests that liberalism,

democracy, and the latter's emphasis on individual rights

have triumphed ideologically

19

3- Potential conflicts existing between the democratic

and nondemocratic zones.

4- Robert Kaplan's (2000) analysis in which he

suggests that societal breakdown in the developing

world (characterized by poverty, inequality, instability,

and strife) will eventually spread to the developed world

and encompass the entire globe.

5- Samuel Huntington (1996) expects conflict to emerge

among various cultural civilizations (Islamic, Judeo-

Christian, Eastern Orthodox, and Confucian) in a

manner that at once potentially supersedes loyalties to

the state internally

20

6- Thomas Friedman (1999) identifies globalization

associated with the free flow of economic goods and

services across the globe as the key international

variable. Nations that embrace globalization will thrive;

those that do not will wither.

7- While pointing to traditional balance of power

considerations as a continuing foundation for

international relations, Charles Kupchan (2002: 318-

319) believes that international politics and internal state

dynamics will increasingly be affected in unpredictable

ways by digital technology's influence on productivity,

economies of scale, and the creation of "atomized and

individualized" modes of production

21

8- John Mearsheimer (2001) emphasizes the

continued dominance of the balance of power and

state competition in an anarchical world.

9- In the future there will be greater movement of

capital, people, ideas, and goods across

increasingly porous international borders. The

challenge for FPA will be to adapt to these

increasingly dynamic processes.

Conclusion 22

leaders and foreign policymakers at all levels will have

to become increasingly responsive to the attitudes of

citizens in countries other than their own if they are to

remain successful. State actors already are beginning to

consider globalized forces and inter- nationalized actors

(for example, international investors, tourist travel

money, global norms, and so on). To formulate foreign

policy successfully, leaders increasingly must anticipate

and react to these forces. As a result, FPA needs to

become responsive to this chain of events by focusing

even more on cross- national bureaucratic, public,

interest group, and decision-making dynamics

23

With increasing globalization, FPA will be critical in

sorting out the interactions among the international,

domestic, and individual levels of analysis and their

effect on policy. Just as some business leaders have

proven adept at seizing the implications of the new

opportunities provided by shifts in technology, some

political leaders embrace avenues to enhance their

political fortunes; others try and fail; and still others

sense no opportunity at all

FPA needs to become increasingly attentive to the

cross-national nature of domestic political influences

24

In the future, perceptive leaders might use the

Internet as a diplomatic tool in yet unforeseen

ways to enhance their connection with their

citizens and citizens of other nations.

As the speed and complexity of international

politics increases, leaders could find that traditional

methods of assessing citizen sentiment (polling,

elections, letters, press, and so on) do not

adequately address their needs in determining the

intensity and nuance of public attitude

25

Although some have claimed that the increasing

speed of media communications hamstrings

policymakers, the data suggest that the media's

need for instant news allows savvy politicians to

shape the message in a manner previously

unthinkable (Strobel 1997). Similarly, the Internet

provides an opportunity for creative politicians to

interact with world opinion in ways limited only by

their imagination.

26

FPA can also provide important assistance to the

strategic interaction literature by assessing where

foreign policy preferences come from and how

these preferences are translated into policies.

Strategic interaction research at the international

level largely takes preferences as given and

assumes that the transmission from preferences

into outcomes is mediated by the institutional

environment, the configuration of the actors'

preferences, and their strategic behavior given

theses factors.

27

Thank you

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Masters of Money Activity AnswersDocument3 pagesMasters of Money Activity AnswersYtfreemode2 2No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Course Outline of Intro To Every Day Science-Bs 4th-1Document3 pagesCourse Outline of Intro To Every Day Science-Bs 4th-1Ytfreemode2 2No ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- PreviewpdfDocument42 pagesPreviewpdfYtfreemode2 2No ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- ApplicationForm PDFDocument5 pagesApplicationForm PDFYtfreemode2 2No ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- RWP IR Result Jun 2022Document13 pagesRWP IR Result Jun 2022Ytfreemode2 2No ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Slips Rc6015 Rc6019 Aug22Document391 pagesSlips Rc6015 Rc6019 Aug22Ytfreemode2 2No ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Academic Calendar (February 2022 To February 2023) - CalendarDocument25 pagesAcademic Calendar (February 2022 To February 2023) - CalendarYtfreemode2 2No ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Silk Fragranza: Presented by Zai-Noora Areej Khalid Mahnoor Fatima Tayyaba Hameed Rubab Nawaz Zeshan Mustafa Fahad KhanDocument19 pagesSilk Fragranza: Presented by Zai-Noora Areej Khalid Mahnoor Fatima Tayyaba Hameed Rubab Nawaz Zeshan Mustafa Fahad KhanYtfreemode2 2No ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- EveningDocument1 pageEveningYtfreemode2 2No ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Review Article The Crimean War and Its Lessons For TodayDocument5 pagesReview Article The Crimean War and Its Lessons For TodayYtfreemode2 2No ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Understanding International Diplomacy Theory - Practice and EthicsDocument257 pagesUnderstanding International Diplomacy Theory - Practice and EthicsYtfreemode2 2100% (1)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Baking Science and Technology, Volume 1 by E.J Pyler: Read Online and Download EbookDocument6 pagesBaking Science and Technology, Volume 1 by E.J Pyler: Read Online and Download EbookCamilo Higuera0% (1)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Course Manual Venice, Byzantium, Greek World - 2021-2022Document3 pagesCourse Manual Venice, Byzantium, Greek World - 2021-2022SP CNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- grBKmJyRKC - Tata Motor Finance JDDocument7 pagesgrBKmJyRKC - Tata Motor Finance JDVanya AroraNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Painters Sculptors ArchitectsDocument6 pagesPainters Sculptors ArchitectsELAIZA MAE DELA CRUZNo ratings yet

- Introduction - Future FarmerDocument3 pagesIntroduction - Future Farmerfuture farmersNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Surekha Front PagesDocument6 pagesSurekha Front PagesAnu GraphicsNo ratings yet

- Author 1. Florentino Ayson, Et. AlDocument2 pagesAuthor 1. Florentino Ayson, Et. AlMontarde, Hazel MaeNo ratings yet

- Pro Kontra Ujian Nasional: Dosen Fakultas Tarbiyah IAIN Raden Fatah PalembangDocument24 pagesPro Kontra Ujian Nasional: Dosen Fakultas Tarbiyah IAIN Raden Fatah PalembangRavNo ratings yet

- The-Stakeholders-of-Education-and-Funding-CapabilitiesDocument15 pagesThe-Stakeholders-of-Education-and-Funding-CapabilitiesKaren May Urlanda80% (5)

- AJK Public Service Commission: Application FormDocument4 pagesAJK Public Service Commission: Application FormX Passion KotliNo ratings yet

- Reengineering Retail Stephens en 32925Document5 pagesReengineering Retail Stephens en 32925Deep MannNo ratings yet

- Industrial RelationsDocument20 pagesIndustrial RelationsankitakusNo ratings yet

- FEBE CLARIZE PASAOL - PDS Form (Revised 2017)Document4 pagesFEBE CLARIZE PASAOL - PDS Form (Revised 2017)Czariel Clar Alonzo JavaNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Essential Components of Business AcumenDocument2 pagesEssential Components of Business AcumenYazad DoctorrNo ratings yet

- Principles of Management Mg2351 Anna University Question BankDocument4 pagesPrinciples of Management Mg2351 Anna University Question BankjeebalaNo ratings yet

- Standards For Nursing Education ProgramsDocument14 pagesStandards For Nursing Education ProgramsJeyjusNo ratings yet

- Max's Restaurants in Metro Manila" For The Partial Fulfillment of Our Thesis Writing SubjectDocument3 pagesMax's Restaurants in Metro Manila" For The Partial Fulfillment of Our Thesis Writing SubjectMark Gelo WinchesterNo ratings yet

- ENGLISH (Code No. 301)Document10 pagesENGLISH (Code No. 301)Ashmaaav SharmaNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Job Hazard Analysis (Jha) WorksheetDocument4 pagesJob Hazard Analysis (Jha) WorksheetSamer AlsumaryNo ratings yet

- Safety ExercisessDocument1 pageSafety ExercisessAvralinetine EpinNo ratings yet

- The National Artist of The Philippines Guidelines.: BackgroundDocument30 pagesThe National Artist of The Philippines Guidelines.: BackgroundJizza che Mayo100% (1)

- Chapter 1 Concepts of BusinessDocument28 pagesChapter 1 Concepts of Businessopenid_XocxHDCP100% (2)

- M. Satyanarayana Murthy, J.: Equiv Alent Citation: 2018 (1) ALD (C RL.) 862 (AP), 2018 (2) ALT (C RL.) 70 (A.P.)Document10 pagesM. Satyanarayana Murthy, J.: Equiv Alent Citation: 2018 (1) ALD (C RL.) 862 (AP), 2018 (2) ALT (C RL.) 70 (A.P.)juhiNo ratings yet

- Vageesha Padmananda: Cima Adv Dip MaDocument2 pagesVageesha Padmananda: Cima Adv Dip Mavag eeNo ratings yet

- HPWSDocument23 pagesHPWSpakutharivuNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Organizational Capability As A Competitive Advantage: Human Resource Professionals As Strategic PartnersDocument3 pagesOrganizational Capability As A Competitive Advantage: Human Resource Professionals As Strategic PartnersFaraz ShakoorNo ratings yet

- Aviation Industry in Bangladesh Prospect and ChallangesDocument41 pagesAviation Industry in Bangladesh Prospect and ChallangesKhaled Bin SalamNo ratings yet

- What Is JCIDocument15 pagesWhat Is JCIOdesa Aviles100% (2)

- Computer Integrated Manufacturing SystemDocument12 pagesComputer Integrated Manufacturing Systemabemat100% (1)

- BAESystemsDocument12 pagesBAESystemssri chandanaNo ratings yet