Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Group Design

Uploaded by

irumdocter0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

4 views29 pagesCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

4 views29 pagesGroup Design

Uploaded by

irumdocterCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 29

Group Design

Dr. Sidra Majeed; PT

Assumption of group experimental Design

• Variability is intrinsic to human subjects, rather than

coming from sources external to the people involved.

• The myriad factors —age differences, intelligence,

motivation, health status, and so on.

• if an experimenter uses a large enough sample and the

sample is randomly drawn from the population and

randomly assigned to the groups in the research, all those

intrinsic factors will be balanced out between

experimental and control groups, and the only effects left

(aside from experimental errors) will be those of the

independent variable or treatment.

RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIALS

• RCTs are prospective and experimental

• (1) the independent (treatment) variable is subject

to the controlled manipulation of the investigator

and

• (2) the dependent (measurement or outcome)

variables are collected under controlled conditions.

• The independent variable consists of at least two

levels, including a treatment group and comparison,

or control, group.

• RCT refers to random allocation

RCT

• By definition then, all RCTs are experimental

designs. However, not all experimental designs

are RCTs, in that there are many non-random

ways of placing participants into groups.

• RCTs comparing body-weight–supported

treadmill training to traditional gait training

have been published, similar to phase III trials.

Cautions About RCTs

• For example, if one wanted the strongest

possible evidence about whether cigarette

smoking causes lung cancer, one would design

and implement an RCT comparing a smoking

group to a non-smoking group.

CON…

• practically impossible to obtain a true random

sample of a population.

• Hegde notes that, in random selection,

“All members of the defined population are

available and willing to participate in the

study.” (Not all population in clinic)

• All members of a population have an equal

chance of being selected for a study. (Ethical

consent not obtained)

CON…

• In RCTs, patients are (perhaps) randomly

assigned to fixed treatment conditions.

However, intervention is individualized.

• There is no assumption that results of a group-

design experiment are generalizable to any

particular individual,

• Because results are based on averages and the

“average” person probably does not exist.

SINGLE-FACTOR EXPERIMENTAL

DESIGNS

• In 1963, Campbell and Stanley published what

was to become a classic work on single-factor

experimental design:

• Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs

for Research.

• 16 different experimental designs

Typology of experimental design

• Campbell and Stanley (1966) developed the typology

of design explored here

• R= Random allocation to group

• O= Observation or measurement

• C= Control Group

• E= Experimental group

• X= exposure of the group to the experimental variable

Pretest–Posttest Control-Group Design

• The design calls for at least two groups

randomly selected (as well as possible) from

the population of interest and randomly

assigned to one group or another

• Performance on the dependent variable(s) is

measured and, often, equivalence on the

dependent variable(s) is determined

statistically.

Example

• Runeson and Haker used the classic design to study the effect of

iontophoresis with cortisone on the treatment of lateral epicondylitis, or

tennis elbow.

• They compared two groups: a treatment group that received cortisone

iontophoresis

• and a passive control group that received sham iontophoresis.

• They were treated four times over 2 weeks and were measured at the

conclusion of the treatment and at 3 and 6 months following the

completion of the treatment.

• Both groups improved during the study and follow-up period, and there

was no statistically significant difference in the response between the two

groups, leading the authors to question the use of cortisone iontophoresis

in the treatment of tennis elbow.

CON…

• In clinical research, the pretest–posttest control group design is often altered slightly, as

follows:

R O X1 O

R O X2 O

when the researcher does not believe it is ethical to withhold treatment or when two treatments

for comparison. A control group receiving a standard treatment can be referred to as an active

control group.

• Pulvermuller and colleagues used a pretest–posttest control-group design with an

active control group in their study of constraint-induced therapy for chronic

aphasia after stroke. The treatment group received constraint-induced therapy

with intense practice over 10 days. The control group received conventional

therapy for aphasia over 4 weeks. Treatment showed significant improvement

in a number of communication variables compared with the conventional

group.

Additional variation

• Include taking more than two measurements

and using more than two treatment groups.

The general notation for this design would be

as follows, with the appropriate number of

groups and measurement periods:

R O O X1 O O

ROO X2 O O

ROO OO

Posttest-Only Control-Group Design

• Researchers use this design when they are not able to

take pretest measurements.

• judgments about the effect of the independent

variable on the dependent variable.

• Like the pretest–posttest control-group design, this

design is an RCT and a between-groups design. The

Campbell and Stanley10(p25) notation for this design

is as follows:

RXO

RO

CON…

• Baty et al used this design to compare the effects of a

carbohydrate-protein supplement (CHO-PRO) versus a

placebo on resistance exercise performance of young,

healthy men.

• The study was double-blind. The 34 participants were

randomly assigned and asked to perform a set of eight

resistance exercises.

• Performance of the exercises did not vary significantly

between groups, although the researchers concluded that

the CHO-PRO inhibited muscle damage to a greater degree

than did the placebo based on posttreatment measures of

myoglobin and creatine kinase.

Single-Group Pretest–Posttest Design

• The Campbell and Stanley notation for the

single group pretest–posttest design is as

follows:

OXO

• Unlike the above mentioned designs, the

single-group design is neither an RCT nor a

between-groups design.

EXAMPLE

• In a pilot study, Novack et al examined the effects of an in-

home occupational therapy program on 20 children with

spastic hemiplegic cerebral palsy.

• Dependent variables were changes in the Goal Attainment

Scaling (GAS), the Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory

(PEDI), and the Quality of Upper Extremity Skills Test

(QUEST).

• They also measured participation amount through a parent

self-report. They found that significant changes on the

published scales occurred after implementing the home

program but found no relationship between participation

amount and outcome using the same measures.

Nonequivalent Control-Group Design

• Used when a nonrandom control group is available

for comparison.

• The Campbell and Stanley notation for this design

is as follows:

O XO

-----------

O O

• The dotted line between groups indicates that

participants were not randomly assigned to groups.

Example

• Case-Smith’s study of the effectiveness of a school-based occupational

therapy intervention on handwriting.

• In this study, occupational therapists in five school districts identified

potential participants for the intervention group from among those who

had been referred to them for occupational therapy to improve

handwriting skills. Then, teachers in those same districts identified

potential participants for the comparison group from among students with

poor handwriting who had not been referred to occupational therapy.

• There were some differences between the two groups that probably

resulted from this nonrandom allocation to groups: several children in the

occupational therapy group but none in the comparison group were

receiving speech language therapy and physical therapy and higher

proportions of children in the occupational therapy group were diagnosed

with learning or developmental disabilities.

Time Series Design

• Used to establish a baseline of measurements

before initiation of treatment to either a group or

an individual.

• When a comparison group is not available, it

becomes important to either establish the stability

of a measure before implementation of treatment

• The Campbell and Stanley notation for the time

series design is as follows:

OOOOXOOOO

CON…

• Ulione used a time series approach to study the impact of a

health promotion and injury prevention program at a child

development center. Data on the upper respiratory illnesses,

diarrhea, and injuries of the children in the development

center were collected once a week for 4 weeks before and

after the health promotion program.

• The four measurements taken before and after the

intervention provide a fuller picture of the health status of the

children than would single pretest and posttest measures.

• Although the time series approach can be applied to group

designs, as it was in Ulione’s work, in rehabilitation research it

is commonly used with a single-subject approach

Repeated Measures or Repeated

Treatment Designs

• Repeated measures designs are widely used in health science

research.

• The term repeated measures means that the same

participants are measured under all the levels of the

independent variable.

• In this each participant receives more than one actual

treatment. The repeated measures designs are also referred

to as with in subjects or within-group designs because the

effect of the independent variable is seen within participants

in a single group rather than between the groups. When the

order in which participants receive the interventions is

randomized, this design is considered an RCT with a cross-

over design.

There are two basic strategies for selecting treatment

orders in a repeated measures design with several levels

of the independent variable.

MULTIPLE-FACTOR EXPERIMENTAL

DESIGNS

• we wanted to conduct a study to determine the effects of different

rehabilitation programs on swallowing function after cerebral vascular

accident.

• start by selecting 60 patients for study and randomly assigning them to

one of the three groups (posture program, oral-motor program, and a

feeding cues program). The first independent variable would type of

treatment, or group.

• Then assume that two different therapists—perhaps a speech-language

pathologist and an occupational therapist—are going to provide the

treatments. A second independent variable, then, is therapist.

• a third question must also be asked in this design: Is one therapist more

effective with one type of treatment and the other therapist more

effective with another type of treatment? (interaction).

3 × 2 factorial design

Completely Randomized Versus

Randomized-Block Designs

• The Treatment × Therapist

• example of a completely randomized design

• a randomized-block design is used, in which

one of the factors of interest is not

manipulable

• one of the independent variables is active

(manipulable); the other is very often an

attribute variable, such as age, or clinical status

• Participants would be placed into blocks based on

gender and then randomly assigned to treatments.

• This arrangement is also known as a mixed design and is

extremely common in rehabilitation research.

• Most often, the within-subjects factor is the

manipulable, active independent variable; all

participants receive all the levels of treatment. The

within-subjects factor is usually the groups in the

research, very often based on an attribute variable (e.g.,

typically developing versus hearing-impaired children).

Mixed design

• A mixed, or split-plot, design contains a combination of between-subjects

and within-subject factors.

You might also like

- I Never Knew I Had A Choice 11th Edition Corey Test BankDocument10 pagesI Never Knew I Had A Choice 11th Edition Corey Test BankLeroyBrauncokfe100% (12)

- Single Group Design: Presented byDocument13 pagesSingle Group Design: Presented byIyannaGee100% (3)

- Final PPT Experimental ResearchDocument36 pagesFinal PPT Experimental ResearchYosephine Susie Saraswati100% (2)

- Study Guide for Practical Statistics for EducatorsFrom EverandStudy Guide for Practical Statistics for EducatorsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- True Experimental DesignsDocument28 pagesTrue Experimental Designsleo markNo ratings yet

- Research Design: By: Dr. Lucille C. Himpayan College of EducationDocument26 pagesResearch Design: By: Dr. Lucille C. Himpayan College of EducationMary Joy Libe NuiqueNo ratings yet

- 2.1.1.P Research Design Interactive PresentationDocument39 pages2.1.1.P Research Design Interactive PresentationPurePureMilkNo ratings yet

- Epidemiological Approaches and MethodsDocument30 pagesEpidemiological Approaches and Methodsshubha jeniferNo ratings yet

- MA 200 - Designing Quantitative StudiesDocument37 pagesMA 200 - Designing Quantitative Studiesxandra joy abadezaNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 - Research Methodology (Research Design)Document29 pagesUnit 5 - Research Methodology (Research Design)Nur Farihin WahabNo ratings yet

- 7th Lecture EBPDocument20 pages7th Lecture EBPway to satlokNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8 - Creating The Appropriate Research DesignDocument58 pagesChapter 8 - Creating The Appropriate Research DesignFarah A. RadiNo ratings yet

- Lesson-2-Final ModuleDocument39 pagesLesson-2-Final Modulespg9m2gjn2No ratings yet

- Checklist Systematic Review - DefaultDocument31 pagesChecklist Systematic Review - DefaultThalia KarampasiNo ratings yet

- Research Study DesignsDocument74 pagesResearch Study Designsps.pcpc221No ratings yet

- Quantitative Research DesignsDocument6 pagesQuantitative Research DesignsMegan Rose MontillaNo ratings yet

- Mandeep Kaur M.Sc. (Medical-Surgical Nursing) Lecturer, College of Nursing, DMC & H, LudhianaDocument94 pagesMandeep Kaur M.Sc. (Medical-Surgical Nursing) Lecturer, College of Nursing, DMC & H, LudhianaNavpreet Kaur90% (10)

- Study DesignsDocument43 pagesStudy DesignsPalavalasa toyajakshiNo ratings yet

- Pre-Experimental and Quasi Experimental DesignsDocument29 pagesPre-Experimental and Quasi Experimental DesignsGerome Rosario100% (1)

- Experimental Study DesignDocument49 pagesExperimental Study DesignAyeshaNo ratings yet

- Kinds of Experimental ResearchDocument7 pagesKinds of Experimental Researchdewi nur yastutiNo ratings yet

- Experimental DesignDocument99 pagesExperimental DesignDivine MenchuNo ratings yet

- Biostat Lecture 2Document53 pagesBiostat Lecture 2Jeremie GalaponNo ratings yet

- Quantitative Research DesignsDocument22 pagesQuantitative Research DesignsKaren PangilinanNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1 Definitions & Terminologies in Experimental DesignDocument11 pagesLecture 1 Definitions & Terminologies in Experimental DesignMalvika PatelNo ratings yet

- Research On EltDocument14 pagesResearch On EltHy Hy RamandeyNo ratings yet

- Experimental Studies: Randomized Controlled Trials, Field Trials, Community TrialsDocument46 pagesExperimental Studies: Randomized Controlled Trials, Field Trials, Community TrialsMayson BaliNo ratings yet

- BiostatDocument17 pagesBiostatNayabNo ratings yet

- Clinical TrialsDocument158 pagesClinical TrialsVidya Bhushan100% (1)

- Guidelines For Preparing A Medical Research AbstractDocument4 pagesGuidelines For Preparing A Medical Research AbstractVictor Lage de AraujoNo ratings yet

- Quarter 2 - Descriptive Research Design - EXPERIMENTALDocument7 pagesQuarter 2 - Descriptive Research Design - EXPERIMENTALMaelflor PunayNo ratings yet

- Study DesignDocument67 pagesStudy DesignTaki EmmanuelNo ratings yet

- 4 Problem Identification and Writing Research TopicDocument16 pages4 Problem Identification and Writing Research TopicGadisa FitalaNo ratings yet

- 2021 Key Science Skills and Practical Investigation (Autosaved)Document52 pages2021 Key Science Skills and Practical Investigation (Autosaved)averykyliegrambs.17No ratings yet

- #2. The Psychology Professor Has Two Sections of Students That Were Not RandomlyDocument2 pages#2. The Psychology Professor Has Two Sections of Students That Were Not RandomlyShrey MangalNo ratings yet

- Research - Problems - AnalysisDocument44 pagesResearch - Problems - AnalysisAbhishek KumarNo ratings yet

- Experimental DesignsDocument20 pagesExperimental DesignsaliNo ratings yet

- Quasi-Experimental Research DesignDocument22 pagesQuasi-Experimental Research DesignSushmita ShresthaNo ratings yet

- The Nonexperimental and Quasi-Experimental Strategies: Nonequivalent Group, Pre-Post, and Developmental DesignDocument27 pagesThe Nonexperimental and Quasi-Experimental Strategies: Nonequivalent Group, Pre-Post, and Developmental DesignzebraNo ratings yet

- Critical Appraisal: Ns. Indriati Kusumaningsih, Mkep., SpkepkomDocument29 pagesCritical Appraisal: Ns. Indriati Kusumaningsih, Mkep., SpkepkomNYONGKERNo ratings yet

- Physiotherapy Interventions For Ankylosing SpondylitisDocument33 pagesPhysiotherapy Interventions For Ankylosing SpondylitisAlinaNo ratings yet

- Experimental & Quasi Experimental DesignDocument70 pagesExperimental & Quasi Experimental DesignSathish Rajamani100% (1)

- Types of Experimental ResearchDocument2 pagesTypes of Experimental Researchzanderhero30No ratings yet

- Pr2 HandoutDocument6 pagesPr2 HandoutShahanna GarciaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Research Design 1Document29 pagesIntroduction To Research Design 1Maica MaicsNo ratings yet

- Emad Magdy Shawky: Strobe For UndergraduatesDocument60 pagesEmad Magdy Shawky: Strobe For UndergraduatesMuhammad MaarijNo ratings yet

- Experimental Research DesignDocument3 pagesExperimental Research Designnabeel100% (1)

- Non-Experimental ResearchDocument32 pagesNon-Experimental ResearchMyraNo ratings yet

- Group Psychotherapy 2 PresentationDocument18 pagesGroup Psychotherapy 2 PresentationSheza FarooqNo ratings yet

- Repeated Measure DesignDocument8 pagesRepeated Measure Designstudent0990No ratings yet

- Lec14 Experimental Studies (Revised07)Document22 pagesLec14 Experimental Studies (Revised07)Shair Muhammad hazaraNo ratings yet

- Conc 24 E290Document26 pagesConc 24 E290NICOLÁS ANDRÉS AYELEF PARRAGUEZNo ratings yet

- Experimental Study: Stefania Widya S., S.GZ, MPHDocument17 pagesExperimental Study: Stefania Widya S., S.GZ, MPHKinarNo ratings yet

- Critical Appraisal 02 March 2021Document39 pagesCritical Appraisal 02 March 2021Sharifah ShakirahNo ratings yet

- 10 - Experimental MethodsDocument26 pages10 - Experimental Methodsemeeesha11No ratings yet

- Jurnal RisaDocument33 pagesJurnal RisadesialailaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 - The NONEXPERIMENTAL AND QUASI-EXPERIMENTAL STRATEGIESDocument33 pagesChapter 10 - The NONEXPERIMENTAL AND QUASI-EXPERIMENTAL STRATEGIESangeliquefaithemnaceNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 ClinicalDocument27 pagesChapter 2 ClinicalFenny MNo ratings yet

- 01.09.2020 Interventional Study DesignsDocument27 pages01.09.2020 Interventional Study Designsrnkishore_sb241604No ratings yet

- LECTURE NOTES On Pretest and PosttestDocument4 pagesLECTURE NOTES On Pretest and Posttestmarvin jayNo ratings yet

- MetotrexatDocument6 pagesMetotrexatMuhamad Rizqy MaulanaNo ratings yet

- An Example of A Systematic Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesAn Example of A Systematic Literature Reviewaflrpjser100% (1)

- Advance K Send-SayfalarDocument40 pagesAdvance K Send-SayfalarOya Ozkan YilmazNo ratings yet

- CBCP PDFDocument7 pagesCBCP PDFDarnell WoodardNo ratings yet

- Adlerian PPTS&TDocument20 pagesAdlerian PPTS&TPamela joyce c. santosNo ratings yet

- Forklift ForkDocument10 pagesForklift ForkDiah Novita SariNo ratings yet

- Formulation and Evaluation Sustained Release of Lomefloxacin Hydrochloride From In-Situ Gel For Treatment of Periodontal DiseasesDocument6 pagesFormulation and Evaluation Sustained Release of Lomefloxacin Hydrochloride From In-Situ Gel For Treatment of Periodontal DiseasesRam SahuNo ratings yet

- Crime Preventive MeasuresDocument3 pagesCrime Preventive MeasuresNumra AttiqNo ratings yet

- 2015-2016 - 4th MonthlyDocument9 pages2015-2016 - 4th MonthlyDiorinda Guevarra CalibaraNo ratings yet

- How To Improve Clinical Pharmacy Practice Using Key Performance IndicatorsDocument5 pagesHow To Improve Clinical Pharmacy Practice Using Key Performance IndicatorsTaufik Qur RaufNo ratings yet

- Project Management Professional: Exam Preparation CourseDocument8 pagesProject Management Professional: Exam Preparation Coursemarks2muchNo ratings yet

- c052 Cnhi Themeadvilletribune 1037Document1 pagec052 Cnhi Themeadvilletribune 1037Rick GreenNo ratings yet

- Dokumen - Pub John Murtaghs General Practice 8e 9781743768235 9781743768242Document1,887 pagesDokumen - Pub John Murtaghs General Practice 8e 9781743768235 9781743768242koonjNo ratings yet

- Effect of SnailDocument13 pagesEffect of SnailElvy ChardilaNo ratings yet

- Adj 67 S3Document11 pagesAdj 67 S3Wallacy MoraisNo ratings yet

- Diet Nutrition & Obesity PreventionDocument50 pagesDiet Nutrition & Obesity Preventionnaina bhangeNo ratings yet

- Lecture-1-Introduction To Public HealthDocument24 pagesLecture-1-Introduction To Public HealthKaterina BagashviliNo ratings yet

- Quiz 3 AMGT-11: Name: Raven Louise Dahlen Test IDocument2 pagesQuiz 3 AMGT-11: Name: Raven Louise Dahlen Test IRaven DahlenNo ratings yet

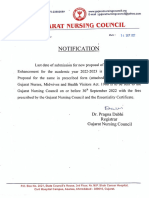

- Last Date of Submission of New ProposalDocument2 pagesLast Date of Submission of New ProposalKUSH JOSHINo ratings yet

- NCM 120 - 1st LEDocument48 pagesNCM 120 - 1st LEYo MamaNo ratings yet

- Great Eastern Life - Confidential Medical Certificate (Other Illnesses) - CLMLAMCODocument2 pagesGreat Eastern Life - Confidential Medical Certificate (Other Illnesses) - CLMLAMCOsimpoonNo ratings yet

- Part E Course Outcomes Assessment Plan: Philippine College of Science and TechnologyDocument2 pagesPart E Course Outcomes Assessment Plan: Philippine College of Science and TechnologyRhona Mae SebastianNo ratings yet

- Jett Plasma Lift 234Document39 pagesJett Plasma Lift 234SuzanaFonsecaNo ratings yet

- Original PDF Psychology Psy1011 and Psy1022 Custom Edition PDFDocument27 pagesOriginal PDF Psychology Psy1011 and Psy1022 Custom Edition PDFkyle.lentz942100% (41)

- India's 1 Health Management LabDocument14 pagesIndia's 1 Health Management LabAjay Kumar dasNo ratings yet

- Hematology - Safety in Hema LabDocument3 pagesHematology - Safety in Hema LabDaniella Andrei PlazaNo ratings yet

- Asthma - Discharge Care For Adults - EnglishDocument2 pagesAsthma - Discharge Care For Adults - EnglishMalik Khuram ShazadNo ratings yet

- Gordon'S Pattern of Functioning Before Hospitalization During Hospitalization Health PerceptionDocument3 pagesGordon'S Pattern of Functioning Before Hospitalization During Hospitalization Health PerceptionTintin TagupaNo ratings yet

- C1 MOCK Quiz 1Document2 pagesC1 MOCK Quiz 1mimi mimi3No ratings yet