Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Academic Writing Research

Uploaded by

Mary-ElizabethClintonCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Academic Writing Research

Uploaded by

Mary-ElizabethClintonCopyright:

Available Formats

The Writing Approaches of University Students Author(s): Ellen Lavelle and Nancy Zuercher Source: Higher Education, Vol.

42, No. 3 (Oct., 2001), pp. 373-391 Published by: Springer Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3448002 Accessed: 13/09/2009 16:50

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=springer. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Higher Education.

http://www.jstor.org

Higher Education 42: 373-391, 2001. ? 2001 KluwerAcademic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands.

373

The writing approaches of university students

EN LAVEf T,E1 EFTl & NANCY ZUERCHER2

U.S.A. 1Department of EducationalLeadership,SouthernIllinois University-Edwardsville, (E-mail: elavell@siue.edu);2Departmentof English Universityof SouthDakota, U.S.A.

Abstract. University students' beliefs about themselves as writersand about the experience of learningin writing were investigatedas related to writing approachesas measuredby the Inventoryof Processes in College Composition (Lavelle 1993). General findings included supportfor the deep and surface paradigmas well as variationin students' conceptions of writing, in their attitudes about themselves as writers, and in their felt need for personal expressionin writing.Implicationsfor instructionand furtherresearchare included. Keywords: interviewmethodology,tertiaryor universitylearning,writingapproaches,writing beliefs

Introduction

Althoughcognitive models have focused on describingthe writingprocesses of college students in terms of problem solving (Flower and Hayes 1979), memory (McCutchenson 1996), and cognitive development (Bereiter and Scardamalia1987; Fitzgeraldand Shanahan2000), writing theory remains somewhatlimited. One shortcominginvolves the reductionisticnatureof the traditionalcognitive perspective, which results in isolating processes such as planning, translatingand revision (e.g. Flower and Hayes 1979); doing violence to the natureof writingas an integrative process (Luria1981). Along the same line, the assumptionthat writing processes occur in a tidy, linear sequence is questionable. Additionally, the role of writers' intentions and beliefs as related to writing processes has not been a major consideration. Writing is the externalizationand remaking of thinking (Applebee 1984; Emig 1977), and to consider writing as separate from the intentions and beliefs of the writer is not to address composition as a reflective tool for makingmeaning. In the area of university learning, researchershave described students' approachesto learning as reflective of the relationshipbetween the student and the task (cf. Biggs 1999; Martonet al. 1997), and the same notion has been applied to college writing (Biggs 1988a, b; Hounsell 1999; Lavelle 1993, 1997) and to writing at the graduatelevel (Biggs et al. 1999). The

374

ELLENLAVELLEAND NANCY ZUERCHER

emphasis is on variationin how it is that studentsgo about making meaning in writing to include considerationof writing intentionsas relatedto writing strategies,ratherthan on the acquisition of skills as independentprocesses (e.g. Hayes and Flower 1980). Here beliefs about the function of writing, and aboutthe writingsituation,are linkedto writingprocesses and outcomes. The primary goal of the present research is to examine university writing approachesas measuredby the Inventoryof Processes in College Composition (Lavelle 1993) in relationto students'beliefs aboutthe natureof writing, and about themselves as writers, thus extending the writing approaches paradigm.A secondary goal is to use interview data to furthervalidate the Inventory of Processes in College Composition (IPIC). Previous validity studies (Biggs et al. 1999; Lavelle 1993, 1997) supported validity using quantitativemethods, but it was felt that the interview strategywould offer an additionaldimensionof support. Writingapproaches Models of individual variationin student learning have offered a comprehensive and sensitive perspective on how it is that students engage in academictasks such as reading(Martonand Saljo 1976), studying(Schmeck 1983), and academic writing (Biggs 1988a, 1988b; Hounsell 1997; Lavelle 1993, 1997; ProsserandWebb 1994). The assumptionhas been thatstudents' beliefs affect their choices of strategies, which, in turn, affect learning outcomes (cf. VanRossum and Schenk 1984). However,the process is largely a reciprocalone in writing because revision, as both a reflective and behavioral undertaking,clearly serves to reshape both thinking and product. The term "approach" was originally used by Marton to describe the quality of students' processing, and later the same notion was extended to include emphasison students'intentionsas relatedto the qualityof processes (Marton et al. 1997). The basic distinction is between a deep, meaningful approach based on seeing the task as a whole andproactiveengagementin learning,and a surface approachbased on reproduction of informationand memorization. In a psychometric study, Biggs (1987) elaboratedthat paradigmto incorporate motivational factors (intrinsic, extrinsic and achievement oriented) as linked to study strategies, and extended it to include the student's level of focus (high, low or alternating)as related to the structureof learning outcome. The approach perspective is dynamic, with learning processes serving as an interfacebetween the situationof learning,or teachingcontext, and studentfactorssuch as intentionalityand motivation.When the student's goal is just to comply with task demands, the learning activity involves a low level of cognitive engagement (e.g. memorizing or repetition) and a superficial, linear outcome (listing or organizing), a surface approach.On

WRITINGAPPROACHES OF UNIVERSITYSTUDENTS

375

the other hand, when the intention is to fully engage the task based on a need to know, the focus is at a higherconceptuallevel, gearedtowardmanipulating layers of meaning, a deep approach.It is the activity of learning that affects the quality of the learning outcome. Thus, approachesare not consistentpersonaldifferences,as stylistic models such as those of Kolb and Schmeck (as cited in Raynerand Riding 1997) would suggest, nor are they entirelydeterminedby context (cf. Martonand Saljo as cited in Biggs 1999). Rather,approachesrepresentan interactionbetween the learnerand the situation of learningwith strategiesserving as a negotiatinglink leading to task outcomes. Biggs (1988a, b) extendedthe approachparadigmto addressuniversitylevel writing. Drawing on studies of text comprehension(e.g. Kirby 1988; Martonand Saljo 1976), Biggs (1988a) articulated a Process x Levels framework to include considerationof writers' levels of ideation (e.g. thematic, paragraph,sentence, word level, grammatical)as related to processes in writingalong a deep and surfaceapproachcontinuum.Lavelle then drew on the approachesto writing model to formulatethe Inventoryof Processes in College Compositionas a measureof writingapproaches. Thefactor structureof universitywriting Workingfrom a psychometric perspective, Lavelle (1993) factor analyzed students' responses to 119 items reflecting writing strategies and writing motives to operationalizethe approaches-to-writing framework.Items were designed to reflect the deep and surface continuumas defined in models of college learning(Schmeck 1988; Biggs 1987), as well Bigg's adaptationof that model to college writing, and Hounsell's (1997) conceptual analyses. In particular,items were written to mirrorwriters' intentions, conceptions of the function of writing, levels of focus, as well as common writing strategies(outlining, grammar,revision). Writing processes had previously been linked to the beliefs of college students regardingwriting (Hounsell 1997; Ryan 1984; Silva and Nicholls 1993) and to the structureof writing outcomes (Hounsell 1997; Biggs 1988a, b; Biggs and Collis 1982). Dimensions parallelingthe deep and surface dichotomy had also been identified by composition researchersworking with children: reactive and reflective (Graves1973), symbolizersand socializers (Dyson 1987), knowledgetelling v. knowledge transforming(Scardamaliaand Bereiter 1982), and, in young adults,reflexive and extensive (Emig 1971) (AppendixA). Based on this broadframework, 212 items were devised to reflectthe core trendsin the literature. The inventorywas administered using a trueand false format to 423 in enrolled response undergraduates generaleducationcourses at a major Midwestern (USA) university.Based on a scree test and on an

376

ELLENLAVELLEAND NANCY ZUERCHER

criterion,the numberof factors was adjusteddownwardand interpretability then rotatedto the varimaxcriterion. Five factors, thoughtto be reflectiveof the writing approachesof college is markedby students,emerged (AppendixB). The first factor"Elaborative" a search for personal meaning, self-investment,and by viewing writing as symbolic, a deep personalinvestment.The focus is high employing tools such as visualization,manipulationof audienceand voice, and extension or going beyond the bounds of the assignment in general. The Elaborativeapproach reflects self-referencing,a strategybased on using writing as a tool for one's own learningor bringingoneself to the situationof writing:"Writingmakes me feel good.""Iput a lot of myself in my writing." A similardimensionhad been definedin college learning,an Elaborative processingstrategy,involving applying new informationin a personal manner(Schmeck et al. 1991), and Silva and Nichols (1993) have subsequentlydefined a similar writing factor, "Poeticquality and personaltaste."High scores on the Elaborativescale have been relatedto the degreeof personalinvolvementin writinga narrative essay (Lavelle 1997) but were not predictive of competence in academic writing (Lavelle 1993). The second factor"LowSelf-Efficacy"describesa highly fearfulapproach based on doubtingability and thinkingaboutwritingas a painful task. It is as thoughstudentsscoring high on this scale have a high degreeof learnedhelplessness. These writers appearneedy: "Studyinggrammarand punctuation would greatly improve my writing.""Having my writing evaluated scares me."This approachevolves aroundpoor writingself-concept, accompanying perceptions of skill deficits, and little, if any, awareness of the function of writing as a tool of meaning and of personal expression. The focus is low involving grammarand sentence structure,surface concerns. College has been associatedwith self-efficacy (Meieret al. 1984; writingperformance Zimmermanand Bandura 1994) and self-esteem (Daly and Wilson 1983), and it may be that self-efficacy provides a critical link to acquiringskill and masteringvariousgenres (Lavelle et al. 2001). "Reflective-Revision,"the third approach, describes a deep writing process based on a sophisticatedunderstandingof revision as a remaking or rebuildingof one's thinking,similarto Silva and Nicholls' (1993) logical reasoning factor. Reflective-Revisionimplies willingness to take charge in writingto make meaningfor oneself and for the audience.The level of focus is high involving thematicand global concerns, and ideation is hierarchical: "In my writing, I use some ideas to supportother, largerideas," similar to Hounsell's "essay as argument" conception(1999). The strategyis to get it all out in a rough draftfor revision ratherthanto dawdle at the sentence level: "I (do not) complete each sentenceandrevise it before going on to the next."It is

WRITINGAPPROACHES OF UNIVERSITYSTUDENTS

377

as thoughthese studentsadoptthe "sculptor" ratherthan "engineer" strategy (cf. Biggs et al. 1999). Writing and revision are intertwinedin a dynamic process gearedtowardmakingmeaning:"Revisionis findingthe shape of my essay."Reflective-Revisionscale scores predictedhigh grades in a freshman compositioncourse (Lavelle 1993). The fourth factor, "Spontaneous-Impulsive," profiles an impulsive and unplannedapproachsimilarto Biggs' SurfaceRestrictiveapproach(1988a). The Spontaneous-Impulsive skill andfear representsoverestimating approach of fully dealing with what the writerperceives as limitations;the approachis defensive. It is as though you just do it and then it is done, "When writing an essay or paper,I just say what I would if I were talking!"The focus is at the surfacelevel: "Revisionis makingminor alterations, just touchingthings up.""I never thinkabouthow I go about writing." The "Procedural" approachinvolves a method-drivenstrategybased on strictadherenceto the rules and a minimalamountof involvement,similarto Silva and Nichol's methodologicalorientation(1993), Berieter'scommunicative (1980), or Bigg's Surface-Elaborative approach(1998a). Such writers ask themselves, "Wherecan I put this informationthat I just came across?" The strategyis listing or providinga "sequenceof ideas, an orderlyarrangement"which is reflective of Hounsell's "essay as arrangement" conception. If writersare unsureof themselves, the rules and "arranging" may keep them afloat,or as Stafford(1978) says in Writingthe AustralianCrawl: But swimmers know that if they relax on the water, it will prove to be miraculouslybuoyant:and writersknow that a succession of little strokes on the materialnearestthem, withoutany prejudgments aboutthe specific of the or reasonableness of their gravity topic expectations,will result in creativeprogress.(p. 23) The proceduralapproachreflects wanting to please the teacher ratherthe intentionto communicateor reflect. It is as though writingis to be managed and controlledtowardthatend. Similarapproachesbased on strivingto manifest competence have been identified in studying (Biggs 1987; Entwistle 1999). Proceduralscale scores were predictive of the complexity of writing outcomes when writers wrote under a timed condition (Lavelle 1997). Perhapsthe proceduralemphasis on "control"in writing, not allowing for emergentfactorssuch as voice and theme, keeps writerson task as limitedby time demands. Reflective-Revision and Elaborative represent deep approaches with Procedural, Spontaneous-Impulsiveand Low Self-Efficacy interpretedas surface approaches.Reflective-Revisionrepresentsa deep thinking,analytic component while Elaborativerepresents the more personal and affective

378

ELLEN LAVELLEAND NANCY ZUERCHER

dimension in writing similar to Silva and Nicholl's aesthetic and expressive goals orientation(1993) (AppendixC). However, Webb (1997) has warnedthat the binary notion of "deep"and "surface"may be too crude, noting that some learners may take surface approaches for deep purposes (although that would be predictable given that approachesare largely modifiable given the writing/learningsituation). However,from a processingperspective,it is useful to thinkaboutthe alternating levels of focus in writing as writers constantly shift between macro concerns (theme, voice, audience), and micro concerns (words, sentences, and syntax (Biggs 1988; Biggs et al. 1999)), althoughthe dichopunctuation, be a bit crude for describing writers' beliefs or conceptions of tomy may writing. Writing approachesare relationalin natureand modifiable. Biggs et al. (1999) found increasedElaborativescale scores and decreasedSpontaneousImpulsiveand Proceduralscores for graduatestudentswritingin English as a Second languagewho were enrolledin a two day academicwritingworkshop. Studentsmay use spontaneouswritingas a tool to get it all started,then move toward refining via genre familiarity and procedures,and hopefully move towarda deep outcome. Although the original assumptionwas for consistency among the factors, a stylistic perspective, it is possible to interpretthe factor scores as either an outcome of a particularteaching environmentor as a more stable student characteristic or trait (Biggs et al. 1999). However, writing is about change and the assumption that students are driven by personal characteristics is a dangerous one given the potential impact of instruction. The style interpretation"encourages teachers to take student differences as given" while the approachesperspective"addressesthe challenges of teaching",an instructional vantagepoint (Biggs et al. 1999, p. 296). In the present study, we wanted to investigate Students' experiences of writing as reflected in personal interviews, and as related to their writing approachesas measuredby the IPIC. Querying studentsas to the natureof theirwritingexperienceshadpreviouslybeen used in college writingresearch by Hounsell (1984) to supportconceptions of the academic essay as related to writing strategiesand essay outcomes, by Biggs (1988b) to furtherdefine writing approaches in term of level of ideation, and by Entwistle (1994) in investigating the 'knowledge object', an emergent structurereflecting students'understanding in preparing for writtenexaminations.Here the interview methodology was used to furtherdifferentiateand expand categories of writing processes. Similarly, Prosser and Webb (1994) had interviewed students and supporteddeep and surface approachesin terms of students' conceptions of academic essay writing, and Ryan (1984) linked epistemolo-

WRITINGAPPROACHES OF UNIVERSITYSTUDENTS

379

gical beliefs to college students' definitions of coherence in writing and to writingoutcomes.Now we sought students'commentson developingknowledge as per writing approachesas measured by the IPIC with the goal of elaboratingthe writing approachesparadigm,as well as offering additional validity for the writing approachesmodel. In line with earlier research on the role of selfhood in writing (cf. Daly and Wilson 1983; Lavelle 1997; Meier et al. 1984), we also wanted to examine the relationshipof students' of themselves as writersto their writing approaches personalinterpretations as measuredby the IPIC inventory.We felt that the interviewstrategywould provide an additionalmethodto supportthe inventoryand thus lend validity. In particular, we hypothesized,based on Lavelle'spsychometricresearch,that studentsadoptinga deep approachin writing, as measuredby the ReflectiveRevision and Elaborativescales of the IPIC, would be more likely to view themselvesas writers,own writing,have a morepositive writingself-concept, and describe the experience of writing as involving learning and changes in thinking. We also suspected that there would be less concern for how much time the writingtask took among Reflective-Revisionand Elaborative writers than among writers scoring high on the surface level scales (Low Self-Efficacy,Procedural, Spontaneous-Impulsive). 1. Method Sample The sample consisted of 30 students enrolled in two freshman composition classes at a medium sized Midwestern(U.S.A.) university.Of the total seventeenwere male and thirteenwere female. Instrumentation The Inventoryof Processes in College Composition(previously discussed) is a 74-item scale measuringfive college writing approaches(AppendixB). Reliability estimates for the scales were considered acceptable(0.83-0.66), and content,concurrent andpredictivevalidity were supportedin the original of the scales (Lavelle 1993, 1997). development Procedures The IPICwas administered duringa regular50-minute class period. Students were instructedto respond on a four-level Likert format on computerized answersheets. Participation was anonymousand voluntary. Thirteenstudents were chosen for interviewsbased on high scores on the scales (scores lying

380

ELLEN LAVELLEAND NANCY ZUERCHER

beyond 1 s.d. above the mean). Participantswere not informed as to their scores so as not to bias their comments, to add truthvalue (Merriam1988) to the researchprocess. Interviews were conducted by the researchersin a privateoffice and tape recordedfor transcription. Interview format A semi-structured interview format, in line with previous writing approach research(e.g. Entwistle and Entwistle 1991; Hounsell 1997; Biggs 1988b), was used to allow maximum opportunitiesfor depth, interpretationand expansion. Our strategywas to alternateseveral open questions with several framework. The open specific (safe) questionsin orderto providea supportive their questionswere gearedto reflectstudents'emergingcommentsregarding and their of in the writing self-concepts experiences learning writing situation. The minor questions involved students' perceptionof time as related to engaging in writing task and writing preferences. Focus on "how long it takes" had been associated with surface learning, and a preference for narrative writinghad been relatedto the Elaborative approach(Lavelle 1997). However,preferencesfor various genres as related to writing processes has not largely been addressedby researchers. After introducingherself, the interviewerindividually asked permission to tape recordthe interviewfor transcription and then proceededto ask each studentthe following: 1. Who are you as a writer? 2. Whattypes of writingtasks do you prefer?Why? 3. Describe your experience of writing. Does your thinking change in of the task? writing?Yourinterpretation 4. Are you concernedabouthow much time your writingtask takes? 2. Results Table 1 shows IPIC Scale means, standard deviationsand range, and Table2 indicates individualstudents' scores. Interestingly,studentsscoring high on more than one scale reflectedeither the deep or surfacedichotomy with one a surfacescale. exception, Matt, who also scored high on Procedural, Albert Low Self-Efficacy/Procedural Elaborative/Reflective-Revision Kathy Tara Elaborative Bob Procedural Joe Low Self-Efficacy/Procedural Barb Elaborative

WRITING APPROACHES OFUNIVERSITY STUDENTS Table1. Means and standard deviationsfor the IPICscale scores Scale Elaborative Low Self-Efficacy Reflective-Revision Spontaneous-Impulsive Procedural Mean 16.3 5.9 10.5 8.8 6.6 sd. 4.5 2.7 3.9 3.3 2.1 Range 8-24 1-10 4-22 2-15 3-10

381

Table2. studentswith high scores on the inventoryof processes in college composition Students Kathy Carol Mary Barb Joe Albert Bob Tara Christa Jack Mike Melanie Matt Elab. 21 L.S.E. R.R. 12 14 14 24 9 9 22 18 22 9 10 21 12 15 10 9 10 S.I. Pr.

Carol Reflective-Revision Mary Spontaneous-Impulsive Matt Elaborative/Reflective-Revision/Procedural Mike Low Self-Efficacy Crista Reflective-Revision Mellanie Low Self-Efficacy/Spontaneous-Impulsive Jack Elaborative A pervasive trend involved students' awareness of the role of process in writing as related to their writing approaches. Those scoring high on Elaborativeand Reflective-Revision,both deep approaches,articulatelyand consistentlyvoiced process as a criticalcomponent,inseparablefromproduct. In particular, scorerslinkedprocess to self-expression.Barb, high Elaborative

382

ELLENLAVELLEAND NANCY ZUERCHER

an Elaborative scorer, stated "... I pick up an idea and start ... the topic

may change as I go but it's still the way that I think, it expresses who I am." all studentsadoptinga deep approachwere comfortablein fully Interestingly, their writing processes, and studentsscoring high on any of the articulating and Procedural), surface scales (Low Self-Efficacy, Spontaneous-Impulsive were not similarlyinclined. Those students scoring high on both the Elaborative and ReflectiveRevision scales describedwritingas primarilyrelatedto changingone's own thinkingaboutthe topic, a feeling of satisfactionand wholeness (cf. Entwistle felt that often his thinking changed so much in 1994). One "Elaborative" writing that he readily developed ideas for subsequentpapers. Matt, who scored high on the Elaborative,Reflective-Revisionand Proceduralscales, stated,"SometimesI change directionandI change as an individualbecause it gives me a new look, it changesmy life." Similarly,Kathy,also an Elaborative andReflective-Revisionscorer,stated,"Ideasdevelopin writingas I go. I start with one idea but finish in a differentdirection." Carol, whose approachwas also Reflective-Revision claimed "Myideas aboutwritingchange when I look at what others have written;class evaluation is very important." Although neitherdeep nor surfacewritersconsistentlycited classroomrevision or peer commentsas criticalto theirprocesses, both Reflective-Revisionand Elaborative approachwritersexpressed a willingness to fully engage the topic, and concernfor an intricatestructure. Writersadoptingthe Elaborativeapproach more consistently cited meaning as personally relevant, and spoke to the generativenatureof writingand to the impact of writingon their lives. Along the same line, Elaborativewritersreportedhaving a strong awareness or feeling as to the completeness of their composition. Tara,an Elaborative,stated"It'slike yourclothes, maybethe colors or style arenot right,its a feeling thatyou get when something'smissing."Similarly,Jackdescribedhis process, "If the concept is large, writing simplifies it. I see the task changing and have a feeling if somethingis missing; it kinda evolves."The awareness of what's missing has been described as a critical component of the emerof knowledge (Entwistle structure gent "knowledgeobject"an organizational It is that this to the "intuition" is Elaborative related 1994). likely approaches' emotionalconnectionto product.Studentsscoring high on Elaborativeseem to bring an strongaffective dimensionto their writing, one that affordsthem skill in troubleshooting. Surprisingly, only two studentssaw themselves as writersin response to the prompt"Whoare you as a writer?" Again, both scored high on the Elaborative scale. Jack reported"It's not easy but I know what I'm doing," and Mattclaimed "I'mconfident,I wear the hat. I feel fine aboutwritingpapers;I see myself as a good writer." It is, perhapsthis personalorientation of seeking

WRITINGAPPROACHES OF UNIVERSITYSTUDENTS

383

self-expressionthatleads one to developingan identityas a writer.Jackstates "Ithinkof myself as a writer.I won't say it comes easy. Writingis for me and if someone else doesn't like it that is their bag. It's about personal growth often throughreadingand having a revelation." Here, a basic distinction may be made between Reflective-Revision and Elaborativeapproachesinvolving personal relevance and the role that self-referenceplays. Although Reflective-Revisionapproachemphasizes the synthesis of information, extensive revision, process awareness, students scoring high on the Reflective-Revisionscale did not reporta great deal of concernfor personalexpressionor for theirpersonalrelationshipto writing. Theircommentswere morefactualandconcise, whereasElaboratives seemed more inclined to "tell the story" of their writing. Elaborativesalso referred to their feelings about writing and to personal ownership of their documents more thanReflective-Revisionapproachwriters.Barb stated "Writing expresses who I am. I like to pick my topic; things that I have experience with."She also keeps a journal as does Tara.Tarastated "I feel that what I writeis my opinion. I thinkwritingis therapeutic, it calms you and helps you realize things more, because in your head it's a mind race, and writingmakes my own understandingmore clear."Elaboratives' interviews were longer and more in-depth.Only Reflective-Revisionsspecificallycited makingtheir ideas clear to the audience, but it may be that Elaborativestake this for granted. The validity of the three surface scales (Low Self-efficacy, Procedural, was confirmed by the interviews. Writers scoring Spontaneous-Impulsive) on Low high Self-Efficacy reporteddisliking writing. For example, Mike said "I hate writing, I only write if I have to," and Joe said, in a low almost inaudibletone, "IwritebecauseI have to, I put my thoughtson paper,it seems to take a long time."Similarly,Bob, a high Procedural, responded,"Ihave no If there is a it's writingpreference. process, just pretty unorganized.I write stuff down. Writingjust rolls off the top of my head, and then I reorder." scorer,commented"Ijust sit down with no Mary,a Spontaneous-Impulsive planningand organize a bit after;it usually takes me 15 minutes to an hour from startto finish."No writersscoring high on the surface scales reported their own process, or a need for selfemphasizingrevision, understanding expression.Most spoke in a very low tone and answeredin brief responses, althoughthe interviewermade every effort to help them to feel at home. One writer.Statingthat he exception was Albert, a Low Self-Efficacy/Procedural wrote better withoutpressure,he cited his attemptto organize with the goal of meeting the requirements. He claimed that he had come a long way, and he was concerned with how much time his assignmentstook. He preferred writingby hand but was easily distracted.Albert took pride in his progress

384

ELLENLAVELLEAND NANCY ZUERCHER

which may be a key to helping basic writers.His attitudewas fairly positive, and he was able to acknowledgehis shortcomingsin writing.Self-acceptance accompaniedby a certain reliance on the rules may serve to keep surface writers "afloat." Similarly a certaindegree of reliance on proceduremay, as Staffordhas articulated, (Stafford1978) as perhaps keep poor writers"afloat" a critical step towardmaturityin wrinting. 3. Discussion Although our writing approachesmodel is not yet fully crystallized, interviews with studentwritershave extended the basic frameworkalong several important lines. Generally writers' perceptions of the writing situation (including writing self-concept, and beliefs about the function of composition) emerged as critical process components which serve to supportthe basic deep and surface continuum,and to more fully extend that paradigm to writing. Most notably, the Reflection Revision approachmay be further distinguishedfrom the Elaborativeapproachin terms of the formerimplying a more critical,structural, dimension,and the lattera more personal,affective dimension involving a high degree of connection and self-reference and feeling in writing. It is the writer's relationship to writing which serves as a defining motivational factor with the Elaborativeapproachlinked to feeling and writing self-concept, and the Reflective-Revisionapproachmore the detached, analytic, and critical dimension. However, both represent a proactivestanceaimed at makingmeaning,awarenessof writingas a learning tool, hierarchicalstructureand a high or alternatinglevel of focus; a deep approach. The interviewdataconfirmedthe threesurfaceapproaches.Here, a dislike and a general fear and avoidance of writing situations was a trend in the comments of students scoring high on the Low Self - Efficacy approach. Similarly,writersscoring high on the Proceduralapproachreportedemphasis on organizationand a concern for how much time writing tasks take, and those scoring high on the Spontaneous- Impulsive scale, reportinga "get it all out and be done" strategy.None of the surface approachesreflected awarenessof process as relatedto outcome,a sense of involvementor feelings of completeness, wholeness in writing, nor the experience of finding oneself or learningin writing. The key to facilitatingwritingat the universitylevel is found in designing a high quality writing climate to include deep tasks, emphasis on revision and meaning, scaffolding, modeling and integratingwriting across content areas (relevance). While these themes may be familiar, the approachesto - writing frameworkbrings a new understandingof these tactics. Here

WRITINGAPPROACHES OF UNIVERSITYSTUDENTS

385

the emphasis is on the situation of writing to include focus on the cues, messages, interventionsand artifactsthat are partof the writingenvironment as opposed to a focus on the discreteacquisitionof skills or on the persistent characteristics that writersmight bring to the classroom.For example, welldefined tasks that engender deep processes such as analysis, perspective taking and self-expression need to be well-specified. Along the same line, clear evaluationrubrics should incorporatedeep criteria such as structural and meaning (cf. complexity to reflect the dynamic naturebetween structure and Collis on a 1982). Evaluatingwriting Biggs point system fosters surface andbreakingwritinginto numerouscomponentpartsas common approaches, in many rubrics is not in line with fostering writing as a tool of meaning. need to value perspectivetakingin writing,or movementin terms Instructors of ontological position as reflected in written work. Along the same line, instructorsneed to provide meaningful feedback, and to generally model a deep reflectiveapproachto instructionthemselves. Perhapsthe axiom "Physician heal thyself' is applicablehere. Clearly our system engenders surface learningwith an abundunceof atomistic, or listing expectations,common in tasks and assessments. Writingacrossthe curriculum may be redefinedas a key to relevance.Here tasks might be both academic as well as personal to foster both Reflective Revision and Elaborative writing flexibility. For example, in addition to academic essays, history courses might require journal-writingto reflect students'developingparadigmsregardingcriticalevents and movements. In terms of writing instruction,it is importantto help writers to gain a positive identity in writing in conjunction with acquiringincreased skills. Studentsneed to be familiarwith how writingworks as a tool of learningand of self-expressionas well as to findpersonalvoice in expositoryandacademic tasks. Here, in additionto familiarizingstudentswith a variety of academic for studentsto share genres,essays on the natureof writing,and opportunities theirown perspectiveson the role of process could be important. This may be especially criticalfor those adoptinga Low Self-Efficacyapproach. and Proceduralapproachesmay representproSpontaneous-Impulsive an of at early stage writing development.Indeed, "gettingit all out" gress or free writingis a well respectedinstructional tactic in composition (Elbow 1998), and, as Staffordsays "Relianceon the rules keeps you afloat."It is as though writing is a dialectic between intention and form. Here, combining the two strategiesas a beginningstep might advancewritingskills for novice writers, as well as for writers faced with mastering a new genre. Future researchshould fully investigatethis hypothesis. Theoreticalimplications drawn from the currentstudy provide a strong basis for futureresearch.The present study served to confirmand elaborate

386

ZUERCHER ELLEN LAVELLE ANDNANCY

the original model particularlyin terms of supportingthe basic deep and surface paradigm. In particular,the bidimensional nature of deep writing processes to include both an affective and critical dimensions, merits further exploration,as does the relationshipof approachesto writingto varioustypes of tasks. Tests for cross - cultural validity using various student populations (e.g. internationalstudents, community college or vocational training students,graduatestudents)should also be conductedto examine the cultural validity of the inventory. Futureresearchplans also include examinationof developmentaltrends across the scale scores both in longitudinaland instructionalinvestigations. A preliminaryinvestigationhas supportedsignificantlylower Proceduraland scale scores given a writing Spontaneousscale scores, andhigherElaboration workshopinterventionat the graduatelevel (Biggs et al. 1999). to writingmodel may help teachersto gain Familiaritywith the approaches a more sensitive understanding of thatprocess. The Inventoryof Processes in College Compositionalso provides a tool for students' personal assessment andreflectionas well as a comprehensivemodel for teachersand researchers.

Appendix A Deep and surface writingapproachesof universitystudents

Deep Writing Metacognitive,Reflective High or alternatinglevel of focus Hierarchicalorganization Engagement,self-referencing Actively making meaning (agentic) Audience concern Thinks aboutessay as an integratedwhole Thesis-driven Revision Transforming, going beyond assignment Autonomous Teacherindependent Feelings of satisfaction,coherence and Connectedness SurfaceWriting Redundant,reproductive Focus at the local level Linear,sequentialstructure Detachment Passive orderingof data Less audience concern Sees essay as an organizeddisplay Data-driven Editing Telling within the given context Rule-bound Teacherdependent

APPROACHES OFUNIVERSITY STUDENTS WRITING

387

Appendix B Inventoryof processes in college composition:sample questions

FACTORI Elaborative 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. Writingmakes me feel good. I tend to give a lot of descriptionand detail. I put a lot of myself in writing. I use writtenassignmentsas learningexperiences. Writingan essay or paperis making a new meaning. At times, my writinghas given me deep personalsatisfaction. Writingis like a journey. to me to like what I've written. It's important I thinkabouthow I come across in my writing. I often thinkaboutmy essay when I'm not writing (e.g. late at night). I sometimes get suddeninspirationsin writing. Writinghelps me organizeinformationin my mind. I cue the readerby giving a hint of what's to come. I often use analogy and metaphorin my writing. I imagine the reactionthatmy readersmight have to my paper. When writing a paper,I often get ideas for otherpapers. I compareand contrastideas to make my writingclear. I visualize whatI'm writingabout. Writingremindsme of otherthings thatI do. Writingis symbolic. Originalityin writingis highly important. I try to entertain,inform or impressmy audience. I use a lot of definitionsand examples to make things clear. 0.62 0.56 0.54 0.51 0.50 0.49 0.48 0.47 0.45 0.44 0.43 0.42 0.41 0.41 0.40 0.38 0.38 0.37 0.36 0.35 0.33 0.33 0.31

FACTORII Low Self-efficacy 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. I can write a termpaper. Writingan essay or paperis always a slow process. and punctuationwould greatlyimprovemy writing. Studyinggrammar Having my writingevaluatedscares me. I expect good grades on essays and papers. I need special encouragement to do my best writing. I do well on essay tests. I can write simple, compoundand complex sentences. My writingrarelyexpresses what I really think. I like to workin small groupsto discuss ideas or to do revision in writing. -0.54 0.52 0.47 0.41 -0.41 0.39 -0.38 -0.37 0.36 0.35

388 11. 12. 13. 14.

ANDNANCY ELLEN LAVELLE ZUERCHER The most importantthing in writingis observingthe rules of grammar, punctuationand organization. I often do writtenassignmentsat the last minute and still get a good grade. I can't revise my own writingbecause I can't see my own mistakes. If the assignmentcalls for 1000 words, I try to writejust about that many.

0.35 -0.33 0.29 0.26

FACTORImReflective-Revision 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. I re-examineand restatemy thoughtsin revision. Thereis one best way to write a writtenassignment. I complete each sentence and revise it before going onto the next. The reason for writing an essay really doesn't matterto me. Often my first draftis my finishedproduct. Revision is a one time process at the end. When given an assignmentcalling for an argumentor viewpoint, I immediatelyknow which side I'll take. My prewritingnotes are always a mess. I plan out my writing and stick to the plan. In my writing,I use some ideas to supportother,largerideas. It's importantto me to like what I've written. Revision is the process of findingthe shape of my writing. The question dictatesthe type of essay called for. 0.52 -0.45 -0.41 -0.39 -0.39 -0.39 -0.39 0.36 -0.35 0.33 0.33 0.35 0.31

FACTORIV Spontaneous-Impulsive 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. My writing 'just happens' with little planningor preparation. I often do writtenassignmentsat the last minute and still get a good grade. I never thinkabouthow I go aboutwriting. Often my first draftis my finishedproduct. I usually write severalparagraphs before rereading. I just write 'off the top of my head' and then go back and rework the whole thing. I startwith a fairly detailed outline. I plan, write and revise all the same time. I am my own audience. When I begin to write, I have only a vague idea of how my essay would come out. 0.51 0.47 0.45 0.45 0.42 0.41 -0.40 0.37 0.30 0.34

WRITING APPROACHES OFUNIVERSITY STUDENTS 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. Revision is makingminor alterations- just touching things up andrewording. I can't revise my own writingbecause I can't see my own mistakes. When writing an essay or paper,I just write out what I would say if I were talking. Revision is a one time process at the end. I set aside specific time to do writtenassignments.

389

0.34 0.33 0.32 0.31 -0.29

FACTORV Procedural 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. When writing an essay, I stick to the rules. I closely examine what the essay calls for. I keep my theme or topic clearly in mind as I write. I can usually find one main sentence that tells the theme of my essay. The teacheris the most importantaudience. I like writtenassignmentsto be well-specified with details included. My intentionin writingpapersor essays is just to answer the question. The main reason for writing an essay or paperis to get a good gradeon it. An essay is primarilya sequence of ideas, an orderly arrangement. I worryabouthow much time my essay or paperwill take. 0.54 0.52 0.43 0.41 0.40 0.34 0.33 0.31 0.29 0.28

Appendix C Approaches to Writing

Approach Elaborativevoice Low Self-Efficacy Reflective-Revision Motive To self-express To acquireskills/avoid Strategy Visualization,audience. collaborate, Study grammar, find encouragement. Revision, reshaping,drafting. Last minute,no planningor Revision,just like talking. Observerules, organizeand managewriting.

pain To make meaning Spontaneous-Impulsive To get done Please the teacher

Procedural

390

ELLEN LAVELLE ANDNANCY ZUERCHER

References

Applebee, A.N. (1984). 'Writingand reasoning', Review of EducationalResearch 54, 577596. Bereiter,C. and Scardamalia,M. (1987). The Psychology of WrittenComposition.Hillsdale: LawrenceErlbaum. Biggs, J.B. (1987). StudentApproaches To Learning and Studying. Melbourne:Council of EducationalResearch. Biggs, J.B. (1988a). 'Approachesto learning and essay writing', in Schmeck, R.R. (ed.), LearningStrategiesand learning Styles. New York:Plenum. Biggs, J.B. (1988b). 'Student approaches to essay-writing and the quality of the written product'.New Orleans, LA: American EducationalResearch Association. (ERIC Document ReproductionService No. ED 293 145). Biggs, J.B. (1999). TeachingFor QualityLearningAt University.BalmoorBuckingham,UK: Open UniversityPress. of creativewriting',Australian Biggs, J.B and Collis, K. (1982). 'The psychological structure Journalof Education26, 59-70. Biggs, J.B., Lai, P., Tang, C. and Lavelle, E. (1999). 'The effects of a writing workshop on graduatestudentswritingin English as a second language', BritishJournalof Educational Psychology 69, 293-306. Daly, J.A. and Wilson, D.A. (1983). 'Writing apprehension,self-esteem and personality', Researchin the Teachingof English 17, 327-342. Elbow, P. (1998). WritingWithPower. New York:OxfordUniversityPress. Emig, J. (1971). The ComposingProcesses of TwelfthGraders.Urbana,IL: National Council of Teachersof English. Emig, J. (1977). 'Writingas a mode of learning', College Compositionand Communication 28, 122-128. Entwistle,N.J. (1979). 'Motivation,styles of learningand the academicenvironment'.(ERIC DocumentReproductionService No. ED 190 636). and strategicstudying'. (ERICDocument Entwistle,N. (1994). 'Experiencesof understanding ReproductionService No. ED 374 704). Entwistle, N. and Entwistle, A. (1991). 'Contrastingforms of understandingfor degree examinations:The student experience and its implications', Higher Education 22(*), 205-227. Dyson, A.H. (1987). 'IndividualdifferencesI beginningcomposing', WrittenCommunication 4,411-442. Fitzgerald,J. and Shanahan,T. (2000). 'Readingand writingrelationsand theirdevelopment', EducationalPsychologist 35, 39-50. Flower,L. and Hayes, J.R. (1979). 'A cognitive process theory of writing', College Composition and Communication 37, 365-377. Good, T. and Brophy J. (1990). LookingIn Classrooms.New York:HarperCollins. Hayes, J. and Flower, L. (1980). 'Identifyingthe organizationof writingprocesses', in Gregg and E. Steinberg(eds.), CognitiveProcesses In Writing.Hillsdale, NJ; LawrenceErlbaum Associates Inc. Graves, D. (1973). 'An examination of the writing processes of seven year-old children', Researchin the Teachingof English 9, 227-241. Hounsell, D. (1997). 'Learningand essay-writing', in Marton,F., Hounsell D. and Entwistle, N. (eds.), The Experienceof Learing. Edinburg:ScottishAcademic Press, pp. 106-125.

WRITING APPROACHES OFUNIVERSITY STUDENTS

391

Lavelle, E (1993). 'Developmentand validationof an inventoryto assess processes in college composition', BritishJournalof EducationalPsychology 63, 489-499. Lavelle, E. (1997). 'Writing style and the narrativeessay', British Journal of Educational Psychology 67, pp. 475-482. Lavelle, E., Smith, J. and O'Ryan, L.W. (2001). 'The writing approaches of secondary in progressfor BritishJournal of EducationalPsychology. students'.Manuscript Luria,A.R. (1981). Languageand Cognition.New York:Wiley. Marton,F. and Saljo, R. (1976). 'On qualitativedifferencesin learning.II: Outcomeas a function of the learner'sconception of the task', British Journal of Educational Psychology 46, 115-127. Marton, E, Hounsell, D. and Entwistle, N. (1997). The Experience of Learning (2ed.). ScottishAcademic Press. Edinburgh: McCutchen, D. (1996). 'A capacity theory of writing: Working memory in composition', EducationalPsychologyReview8, 299-325. P. and Schmeck,R.R. (1984). 'Validityof self-efficacy as a predictorof Meier, S., McCarthy, writingperformance',CognitiveTherapyand Research 8, 107-120. Merriam,S.B. (1988). Case StudyResearchIn Education.San Francisco:Josey-Bass. Prosser,M. and Webb,C. (1994). 'Relatingthe process of undergraduate essay writingto the finishedproduct',Studies in Higher Education 19, 125-138. Rayner,S. and Riding, R. (1997). 'Towardsa categorizationof cognitive styles and learning styles', EducationalPsychology, 5-27. Ryan, M. (1984). 'Conceptionsof prose coherence:Individualdifferencesin epistemological Journalof EducationalPsychology 76, 1226-1238. standards', Scardamalia,M. and Bereiter, C. (1982). 'Assimilatedprocesses in composition planning', EducationalPsychologist 17, 10-24. Schmeck,R.R. (1983). 'Learningstyles of college students',in Dillon, R. and Schmeck, R.R. (eds.), IndividualDifferencesIn Cognition.New York:Academic Press. Schmeck,R.R. (1988). LearningStrategiesand LearningStyles. New York:Plenum. E. and Cercy, S.P. (1991). 'Self-concept and learning:The Schmeck,R.R., Geisler-Brenstein, revised inventoryof learningprocesses', EducationalPsychology 11, 343-362. Silva, T. andNicholls, J. (1993). 'College studentsas writingtheorists:Goals andbeliefs about the causes of success', Contemporary EducationalPsychology 18, 281-293. Stafford, W. (1978). Writing the Australian Crawl. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of MichiganPress. Van Rossum, E.J. and Schenk, S.M. (1984). 'The relationshipbetween learning conception, study strategyand learningoutcome', BritishJournal of EducationalPsychology 54, 7383. Zimmerman,B.J. and Bandura,A. (1994). 'Impact of self-regulatoryinfluences on writing course attainment', AmericanEducationalResearchJournal 31, 845-862.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- (Law Express Questions & Answers) Marina Hamilton - Contract Law (Q&A Revision Guide) - Pearson (2015) PDFDocument289 pages(Law Express Questions & Answers) Marina Hamilton - Contract Law (Q&A Revision Guide) - Pearson (2015) PDFa92% (13)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The General Automobile Insurance Company, Inc.: Insurance Identification Card(s)Document1 pageThe General Automobile Insurance Company, Inc.: Insurance Identification Card(s)Shawn TubbeNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- How To Sell Like A Pro - Dale Carnegie TrainingDocument3 pagesHow To Sell Like A Pro - Dale Carnegie TrainingxxsNo ratings yet

- Proposal For Industrial VisitDocument3 pagesProposal For Industrial Visitraazoo1988% (8)

- Liverpool Drainage History DiscussionDocument2 pagesLiverpool Drainage History DiscussionMary-ElizabethClintonNo ratings yet

- 2 Angela Carter Quotations CLC 1195094839491860 1Document10 pages2 Angela Carter Quotations CLC 1195094839491860 1Mary-ElizabethClintonNo ratings yet

- BoyerDocument54 pagesBoyerMary-ElizabethClinton100% (1)

- English Language PaperDocument9 pagesEnglish Language PaperMary-ElizabethClintonNo ratings yet

- Liverpool Drainage History DiscussionDocument2 pagesLiverpool Drainage History DiscussionMary-ElizabethClintonNo ratings yet

- MANX HEALTH ISSUES IN THE 19TH CENTURYDocument4 pagesMANX HEALTH ISSUES IN THE 19TH CENTURYMary-ElizabethClintonNo ratings yet

- Great Irish Famine - Final Presentation - 2Document22 pagesGreat Irish Famine - Final Presentation - 2Mary-ElizabethClintonNo ratings yet

- Famine Disease and The IrishDocument17 pagesFamine Disease and The IrishMary-ElizabethClintonNo ratings yet

- Poor KingDocument15 pagesPoor KingMary-ElizabethClintonNo ratings yet

- 6 Making SoundsDocument5 pages6 Making SoundsMary-ElizabethClintonNo ratings yet

- Menulis Daftar Pustaka VancouverDocument11 pagesMenulis Daftar Pustaka VancouverRatu Qurroh AinNo ratings yet

- Academic UnitsDocument23 pagesAcademic UnitsMary-ElizabethClintonNo ratings yet

- Academic Writing: Svetlana V. Eremina Saratov State UniversityDocument5 pagesAcademic Writing: Svetlana V. Eremina Saratov State UniversityMary-ElizabethClintonNo ratings yet

- Structure of ReportsDocument3 pagesStructure of ReportsMary-ElizabethClintonNo ratings yet

- Hum Lang As Cultural Transmitted ReplicatorDocument11 pagesHum Lang As Cultural Transmitted ReplicatorMary-ElizabethClintonNo ratings yet

- Learning and AnimalsDocument15 pagesLearning and AnimalsMary-ElizabethClintonNo ratings yet

- 7 GhaDocument20 pages7 GhaMary-ElizabethClintonNo ratings yet

- AnalysisDocument50 pagesAnalysisMary-ElizabethClintonNo ratings yet

- From Calls To TalkDocument7 pagesFrom Calls To TalkMary-ElizabethClintonNo ratings yet

- Gha 2012Document16 pagesGha 2012Mary-ElizabethClintonNo ratings yet

- The 13 Design Features of Human LanguageDocument18 pagesThe 13 Design Features of Human LanguageMary-ElizabethClintonNo ratings yet

- 2, GHA LanguageDocument50 pages2, GHA LanguageMary-ElizabethClintonNo ratings yet

- Rhetorical Life of Scientific FactsDocument23 pagesRhetorical Life of Scientific Factsradek1984No ratings yet

- Apps for Students with Autism Spectrum DisordersDocument1 pageApps for Students with Autism Spectrum DisordersMary-ElizabethClintonNo ratings yet

- Ict 1Document11 pagesIct 1Mary-ElizabethClintonNo ratings yet

- Go Higher Language Semester II: Week 5: Plots, Characters and FunctionsDocument54 pagesGo Higher Language Semester II: Week 5: Plots, Characters and FunctionsMary-ElizabethClintonNo ratings yet

- Welcome To The Go Higher SES Go Higher ICT Skills ModuleDocument8 pagesWelcome To The Go Higher SES Go Higher ICT Skills ModuleMary-ElizabethClintonNo ratings yet

- PaddywackedDocument38 pagesPaddywackedMary-ElizabethClintonNo ratings yet

- SYmbolic GesturesDocument6 pagesSYmbolic GesturesMary-ElizabethClintonNo ratings yet

- Tax Invoice Cum Payment Receipt of PAN Application (Form 49A)Document1 pageTax Invoice Cum Payment Receipt of PAN Application (Form 49A)N R ENTERPRISESNo ratings yet

- Adolescent Alcohol AbuseDocument11 pagesAdolescent Alcohol Abuse4-5 Raquyah MitchellNo ratings yet

- Hanoi: Package DetailsDocument3 pagesHanoi: Package DetailsAnonymous 3AQ05NvNo ratings yet

- City Definition What Is A CityDocument11 pagesCity Definition What Is A CityDeri SYAEFUL ROHMANNo ratings yet

- GS Form No. 8 - Gaming Terminal Expansion-Reduction Notification FormDocument2 pagesGS Form No. 8 - Gaming Terminal Expansion-Reduction Notification FormJP De La PeñaNo ratings yet

- Good Practice Note: Managing Retrenchment (August 2005)Document28 pagesGood Practice Note: Managing Retrenchment (August 2005)IFC Sustainability100% (1)

- Topic: Presentation SkillsDocument5 pagesTopic: Presentation Skillshanzala sheikhNo ratings yet

- PMTraining Exam TipsDocument3 pagesPMTraining Exam TipsYousef ElnagarNo ratings yet

- Classification of Exceptionalities: Welcome, Students!Document28 pagesClassification of Exceptionalities: Welcome, Students!alipao randyNo ratings yet

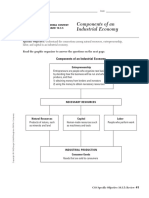

- Components of Industrial EconomyDocument2 pagesComponents of Industrial EconomyEllis ElliseusNo ratings yet

- Bachelor in Business Teacher EducationDocument2 pagesBachelor in Business Teacher EducationMyra CorporalNo ratings yet

- JMB Pharma-Draft MOUDocument20 pagesJMB Pharma-Draft MOUAndrianus Emank JeniusNo ratings yet

- RequiredDocuments For SLBDocument2 pagesRequiredDocuments For SLBRenesha AtkinsonNo ratings yet

- Tax Case AssignmentDocument3 pagesTax Case AssignmentChugsNo ratings yet

- Importance of Entrepreneur ShipDocument23 pagesImportance of Entrepreneur ShipXiet JimenezNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International General Certificate of Secondary EducationDocument16 pagesCambridge International General Certificate of Secondary EducationAhmad BatranNo ratings yet

- Ching V. Goyanko GR NO. 165879 NOV. 10, 2006 Carpio-Morales, J.: FactsDocument3 pagesChing V. Goyanko GR NO. 165879 NOV. 10, 2006 Carpio-Morales, J.: FactsKatherence D DavidNo ratings yet

- President Rajapaksa's Address On 73rd Independence DayDocument8 pagesPresident Rajapaksa's Address On 73rd Independence DayAdaderana OnlineNo ratings yet

- Mega Mini Cross Stitch: 900 Super Awesome Cross Stitch Motifs by Makoto OozuDocument3 pagesMega Mini Cross Stitch: 900 Super Awesome Cross Stitch Motifs by Makoto Oozulinky np0% (8)

- S, The VofADocument93 pagesS, The VofAdowcetNo ratings yet

- Andover Swim LessonsDocument7 pagesAndover Swim LessonsIola IolaNo ratings yet

- Pay and Allowances - Indian RailwaysDocument94 pagesPay and Allowances - Indian RailwaysRajendra Kumar70% (10)

- 01 Melsoft GT Works3 Quick Guide - L08189engaDocument58 pages01 Melsoft GT Works3 Quick Guide - L08189engavuitinhnhd9817No ratings yet

- Ramirez, C. Week8 Gokongwei CULSOCPDocument3 pagesRamirez, C. Week8 Gokongwei CULSOCPChristine Ramirez82% (11)

- Civil society's role in business ethics and sustainabilityDocument25 pagesCivil society's role in business ethics and sustainabilityNic KnightNo ratings yet

- My Days at Lovely Professional University As A FacultyDocument39 pagesMy Days at Lovely Professional University As A Facultybiswajitkumarchaturvedi461550% (2)