Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Introduction: The Assassin Legends: Myths of The Ismailis

Uploaded by

Shahid.Khan1982Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Introduction: The Assassin Legends: Myths of The Ismailis

Uploaded by

Shahid.Khan1982Copyright:

Available Formats

The Institute of Ismaili Studies

The use of materials published on the Institute of Ismaili Studies website indicates an acceptance of the Institute of

Ismaili Studies Conditions of Use. Each copy of the article must contain the same copyright notice that appears

on the screen or printed by each transmission. For all published work, it is best to assume you should ask both the

original authors and the publishers for permission to (re)use information and always credit the authors and source

of the information.

1994,1995, 2001 Farhad Daftary

2003 The Institute of Ismaili Studies

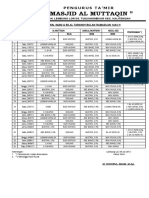

The Old Man of the Mountain and his Paradise, as depicted

in a manuscript of the travels of Odoric of Pordenone

(d. 1331) contained in the Livre des Merveilles (Bibliothque

Nationale, Paris, Ms. fr. 2810). The manuscript was produced

in the 15

th

century for John the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy.

Introduction to The Assassin Legends

Farhad Daftary

*

Reference

Daftary, Farhad. Introduction, The Assassin Legends: Myths of the Ismailis. (London: I. B.

Tauris, 1994; reprinted 2001), pp. 1-7.

Abstract

This article traces the origin and evolution of the

Assassin legends with the aim of invalidating the

scholarly and popular legitimacy they have acquired

over the centuries. The creation and widespread

promulgation of these stories detailing the Nizari

Ismailis use of hashish, the earthly paradise created

by the Old Man of the Mountain and the deadly

missions Ismaili devotees were ready to undertake

were the result of several factors. Western

Orientalists indulged their European audiences with

fabricated tales of passion, mystery and murder. The

perpetuation of misinformation regarding the

community by their Sunni contemporaries reinforced the existing European fictions as the

Crusaders took these damaging accounts home with them. In addition, persecution of Ismailis

necessitated intense secrecy regarding their own practices, beliefs and literature. In more

recent times, European scholars have contributed to the currency of the legends.

Keywords

Assassin legends, Ismaili studies, Nizaris, Ismailis, Alamut, Hassan Sabbah, Crusades, Old Man of the

Mountain, history, Persia, Hashishin.

*

Educated in Iran, Europe and the United States, Dr Farhad Daftary received his doctorate from the University of

California at Berkeley in 1971. He has held different academic positions, and since 1988 he has been affiliated with

The Institute of Ismaili Studies, where he is Head of the Department of Academic Research and Publications. An

authority on Ismaili studies, Dr Daftary has written several acclaimed books in this field, including The Ismailis: Their

History and Doctrines (Cambridge University Press, 1990), The Assassin Legends: Myths of the Ismailis (I. B. Tauris, 1994)

and A Short History of the Ismailis (Edinburgh University Press, 1998). He has also edited Mediaeval Ismaili History and

Thought (Cambridge University Press, 1996) and Intellectual Traditions in Islam (I. B. Tauris in association with The

Institute of Ismaili Studies, 2000). A regular contributor to the Encyclopaedia Iranica of which he is a Consulting Editor,

and the Encyclopaedia of Islam, his shorter studies have appeared in various collected volumes and academic journals. Dr

Daftary is currently working on a biography on the eleventh to twelfth-century Persian Ismaili leader Hassan Sabbah.

Please see copyright restrictions on page 1

2

How It All Began

Western readers of Edward FitzGeralds introduction to his English rendition of Umar

Khayyams quatrains will be familiar with the Tale of the Three Schoolfellows. In this,

the Persian poet-astronomer Umar Khayyam is linked with the Saljuq vizier Nizam al-

Mulk and Hasan Sabbah, the founder of the so-called Order of Assassins. The three

famous Persian protagonists of this tale were, allegedly, classmates in their youth under the

same master in Nishapur. They made a vow that whichever of them first achieved success

in life would help the other two in their careers. Nizam al-Mulk attained rank and power

first, becoming the vizier to the Saljuq sultan, and he kept his vow, offering Khayyam a

regular stipend and giving Hasan a high post in the Saljuq government. However, Hasan

soon became a rival to Nizam al-Mulk, who eventually succeeded through trickery in

disgracing Hasan before the sultan. Hasan vowed to take revenge. He left for Egypt, where

he learned the secrets of the Ismaili faith, and later returned to Persia to found a sect that

terrorised the Saljuqs through its assassins. Nizam al-Mulk became the first victim of

Hasans assassins. This is one of the eastern legends connected with the Nizari Ismailis,

known to mediaeval Europe as Assassins.

In the West, too, the Nizaris have been the subjects of several legends since the twelfth

century. The first contact between the Europeans, or the Latin Franks, then engaged in the

Crusading movement to liberate the Holy Land, and the members of this Shii Muslim

community occurred in Syria during the earliest years of the twelfth century. At the time,

the Nizari Ismailis had just founded, under the leadership of the redoubtable Hasan Sabbah,

a special territorial state of their own, challenging the hegemony of the Saljuq Turks in the

Muslim lands. Subsequently, the Nizari Ismailis of Syria became involved in a web of

intricate alliances and rivalries with various Muslim rulers and with the Christian Franks,

who were not interested in acquiring accurate information about their Ismaili neighbours,

or indeed about any other Muslim community, in the Latin Orient. Nonetheless, the

Crusaders and their occidental observers began to transmit a multitude of imaginative

tales about the so-called Assassins, the devoted followers of a mysterious Vetus de

Montanis or Old Man of the Mountain. These Assassin legends soon found wide

currency in Europe, where the knowledge of all things Islamic verged on complete

ignorance and the romantic and fascinating tales told by the returning Crusaders could

achieve ready popularity.

The Assassin legends, rooted in the general hostility of the Muslims towards the Ismailis

and the Europeans own fanciful impressions of the Orient, evolved persistently and

systematically during the Middle Ages. In time, these legends were taken, even by serious

western chroniclers, to represent accurate descriptions of the practices of an enigmatic

eastern community.

The Assassin legends thus acquired an independent currency, which persistently defied

re-examination in later centuries when more reliable information on Islam and its internal

Please see copyright restrictions on page 1

3

divisions became available in Europe. However, progress in Islamic studies, and a

remarkable modern breakthrough in the study of the history and doctrines of the Ismailis,

have finally made it possible to dispel once and for all some of the seminal legends of the

Assassins, which reached their height in the popular version attributed to Marco Polo,

the famous thirteenth century Venetian traveller. It is the primary object of this study to

trace the origins of the most famous of the mediaeval legends surrounding the Nizari

Ismailis, at the same time investigating the historical circumstances under which these

legends acquired such widespread currency.

The Nizari Ismailis

The Nizari lsmailis, numbering several millions and accounting for the bulk of the Ismaili

population of the world, are now scattered over more than 25 countries in Asia, Africa,

Europe and North America. They currently acknowledge Prince Karim Aga Khan as their

49th imam or spiritual leader. The Ismailis represent an important minority community of

Shii Muslims, who themselves today account for about 10 per cent of the entire Muslim

society of around one billion persons.

The Ismailis have had a long and eventful history, stretching over more than 12 centuries,

during which they became subdivided into a number of major branches and minor

groupings. They came into existence, as a separate Shii community, around the middle of

the eighth century; and, in mediaeval times, they twice founded states of their own, the

Fatimid caliphate and the Nizari state. At the same time, the Ismailis played an important

part in the religio-political and intellectual history of the Muslim world. The celebrated

Ismaili dais or propagandists, who were at once theologians, philosophers and political

emissaries, produced numerous treatises in diverse fields of learning, making their own

contributions to the Islamic thought of mediaeval times.

In 1094, the Ismaili movement, which had enjoyed unity during the earlier Fatimid

period, split into its two main branches, the Nizaris and the Mustalians. The Nizaris, who

are the main object of this investigation, succeeded in founding a state in Persia, with a

subsidiary in Syria. This territorially scattered state, centred on the mountain fortress of

Alamut in northern Persia, maintained its cohesiveness in the midst of a hostile

environment controlled by the overwhelmingly more powerful and anti-Shii Saljuq

Turks, who championed the cause of Sunni Islam and its nominal spokesman, the

Abbasid caliph at Baghdad. It was under such circumstances that the Syrian Nizaris were

forced to confront a new adversary in the Christian Crusaders who, from 1096, had set out

in successive waves to liberate the Holy Land of Christendom from the domination of the

Muslims (or the Saracens as they were commonly but incorrectly called). The Nizari

Ismaili state, which controlled numerous mountain strongholds and their surrounding

villages as well as a few towns, finally collapsed in 1256 under the onslaught of the

Mongols. Thereafter, the Nizaris of Persia, Syria and other lands survived merely as Shii

minority communities without any political prominence.

Please see copyright restrictions on page 1

4

The Genesis of the Term

The western tradition of calling the Nizari lsmailis by the name of Assassins can be traced

to the Crusaders and their Latin chroniclers as well as other occidental observers who had

originally heard about these sectarians in the Levant. The name, or more appropriately

misnomer, Assassin, which was originally derived under obscure circumstances from

variants of the word hashish, the Arabic name for a narcotic product, and which later

became the common occidental term for designating the Nizari lsmailis, soon acquired a

new meaning in European languages; it was adopted as a common noun meaning

murderer. However, the doubly pejorative appellation of Assassins continued to be

utilised as the name of the Nizari Ismailis in western languages; and this habit was

reinforced by Silvestre de Sacy and other prominent orientalists of the nineteenth century

who had begun to produce the first scientific studies about the Ismailis.

In more recent times, too, many western Islamists have continued to apply the ill-

conceived term Assassins to the Nizari Ismailis, perhaps without being consciously

aware of its etymology or dubious origins. Bernard Lewis, the foremost modern authority

on the history of the Syrian Nizaris and a scholar who has also concerned himself with the

etymological aspects of the term Assassin, has consistently used it in his work, even

adopting it for the title of his well-known monograph on the Nizari Ismailis.

1

Marshall

Hodgson also used it in the title of his standard scholarly treatment of the subject.

2

It is,

therefore, not surprising that a non-specialist such as the famous English explorer Freya

Stark (1893-1993), who visited Alamut in 1930, should have decided to use this term in

the title of her romantic and still highly popular travelogue which, in fact, relates mainly

to sites in Persia other than Alamut.

3

A similar choice was made by an Oxford

expeditionary group of scholars who went to Persia in 1960 to conduct the most extensive

archaeological investigation yet of the mediaeval Nizari strongholds of northern Persia,

even though they had the renowned Ismaili specialist Samuel Stern (1920-69) as their

historical adviser.

4

Indeed, despite the long-standing correct identification of the people in

question as Nizari Ismailis, the appellation of Assassins has by and large been retained in

the West. Doubtless, the term Assassins, with its aura of mystery and sensation, has

acquired an independent currency.

The Legends Themselves

The myths and legends of the Nizari Ismailis, encouraged throughout the centuries by the

retention of the name Assassins, seem to have had a similar history. Starting in the latter

decades of the twelfth century, a number of inter-related legends began to circulate in the

Latin Orient and Europe about this mysterious eastern sect, whose members had attracted

attention because of their seemingly blind obedience to their leader, the Old Man of the

1

Bernard Lewis, The Assassins: A Radical Sect in Islam (London, 1967).

2

Marshal G. S. Hodgson, The Order of Assassins: The Struggle of the Early Nizari Ismailis against the Islamic World (The

Hague, 1955).

3

Freya Stark, The Valleys of the Assassins and other Persian Travels (London, 1934).

4

Peter R.E. Wiley, The Castles of the Assassins (London, 1963).

Please see copyright restrictions on page 1

5

Mountain. Their self-sacrificing behaviour, carrying out dangerous missions at the behest

of the Old Man, was soon attributed by their occidental observers to the influence of an

intoxicating drug like hashish. This provided a rational explanation for behaviour that

otherwise seemed irrational. The observers, however, had at best heard only fictitious

details and distorted half-truths about the Nizaris from their numerous Muslim and

Christian enemies in the Levant. Once the hashish connection was firmly established, it

provided ample source material for yet more imaginative tales. The Old Man was held

to control the behaviour of his would-be assassins through regulated and systematic

administration of some intoxicating potion like hashish, in conjunction with a secret

garden of paradise in which his drugged devotees would temporarily enjoy the delights

of an earthly paradise; hence, they would carry out the dangerous commands of their chief

in order to experience such bliss in perpetuity.

The Role of the Orientalists

It did not take long for these legends to become fully elaborated and accepted as authentic

descriptions of the secret practices of the Nizaris, who were now generally depicted in

European sources as a sinister order of drugged and murderous Assassins. These popular

legends were handed down from generation to generation, providing important source

materials even for the more scholarly Ismaili studies of the nineteenth-century

orientalists, starting with Silvestre de Sacy who himself solved an important etymological

mystery in this field, the connection between the words Assassin and hashish. Joseph von

Hammer-Purgstall (1774-1856), the Austrian orientalist-diplomat who produced the first

monograph in a European language on the Nizari Ismailis, had indeed accepted the

authenticity of the Assassin legends wholeheartedly.

5

His book was treated as the

standard account of the Nizaris of the Alamut period, at least until the 1930s.

The Role of Muslim Polemicists

In the meantime, Muslim authors from early in the ninth century had generated their own

myths of the Ismailis, especially regarding the origins and aims of the Ismaili movement.

In particular, Sunni Muslims, who were generally ill-informed about the internal divisions

of Shiism and could not distinguish between the Ismailis and the dissident Qarmatis,

wrote more polemical tracts against the Ismailis than any other Muslim group, also

blaming the Ismaili movement for the atrocities of the Qarmatis of Bahrain. In time, the

anti-Ismaili polemicists themselves contributed significantly to shaping the hostility of

Muslim society at large towards the Ismailis.

By spreading their disparaging accounts widely from Transoxania to North Africa, aiming

to discredit the entire Ismaili movement, the Muslim polemicists gave rise to their own

particular black legend of Ismailism, which they portrayed as a sect with dubious

founders and secret, graded initiation rites leading to irreligiosity and nihilism. Indeed,

5

See Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall, Die Geschichte der Assassinen (Stuttgart-Tbingen, 1818), pp 211-14. English trans.,

The History of the Assassins, tr. O.C. Wood (London, 1835, reprinted, New York, 1968), pp 136-8.

Please see copyright restrictions on page 1

6

the most common feature of such anti-Ismaili polemics, which greatly influenced all

Islamic writings on the Ismailis until modern times, was the portrayal of Ismailism as an

arch-heresy or ilhad, carefully designed to destroy Islam from within. It was further

alleged that the Ismaili imams, including especially the Fatimid caliphs, had falsely

claimed Fatimid Alid descent from the Prophets daughter Fatima and her husband Ali,

the first Shii imam. Needless to say, the anti-Ismaili sentiments of the polemicists also

found expression in the writings of very many Muslim historians, theologians, jurists and

heresiographers of mediaeval times, who rarely missed an opportunity to denounce the

Ismailis and their doctrines. The anti-Ismaili black legend of the Muslim polemicists,

and the general hostility of Muslim society towards the Ismailis, in time contributed to the

westerners imaginative tales about the Nizari Ismailis.

The Role of the Ismailis

The Ismailis themselves did not help matters by guarding their literature and refusing to

divulge their doctrines to outsiders. They were, though, essentially justified in maintaining

their secretiveness; in the Middle Ages the Ismailis were perhaps the most severely

persecuted community within the Muslim world, subjected to massacres in many localities.

The lsmailis were, therefore, obliged from the beginning of their history to adhere closely to

the Shii principle of taqiyya, precautionary dissimulation of ones true religious belief in

the face of danger. In fact, with the major exception of the Fatimid period, when Ismaili

doctrines were preached openly in the Fatimid dominions, Ismailism developed in utmost

secrecy and the Ismailis were coerced into what may be termed an underground or

clandestine existence. In addition, the dais who produced the bulk of the Ismaili writings

were mainly theologians and, as such, were not keen on historiography. All this, of course,

provided ideal opportunities for the Ismailis numerous adversaries to falsify and

misrepresent their actual beliefs and practices.

The Literary Background

It was against this background that the orientalists of the nineteenth century, who had for

the first time gained access to important collections of Islamic manuscripts held at major

European libraries in Paris and elsewhere, began what promised to be a scientific study of

the Ismailis. Unfortunately, they too achieved few results, mainly because they had no

access to genuine Ismaili texts and were therefore obliged to approach the subject from the

narrow and fanciful viewpoint of the mediaeval Crusaders and the travesties of hostile

Muslim authors. It is only against this literary background that one can read any sense into

some of the conjectures and dubious inferences of Silvestre de Sacy (1758-1838), the

greatest orientalist of the time, who summarised his main ideas on the Nizari Ismailis in his

Mmoire sur la dynastie des Assassins. The distorted image of the Ismailis in general and

the Nizari Ismailis in particular was maintained in orientalist circles until the opening

decades of the twentieth century. A truly scholarly assessment of the Ismailis had to await

the recovery and study of a large number of Ismaili texts, a process that did not start until

almost a century after de Sacys death. It is due to the findings of modern scholarship that

Please see copyright restrictions on page 1

7

we are now finally in a position to distinguish fantasy or legend from reality in things

Ismaili, especially in connection with the Nizaris of the Alamut period who were the objects

of the seminal Assassin legends.

Proliferating the Tales

In the light of these findings, this study contends that the Assassin legends, especially those

based on the hashish connection and the secret garden of paradise, were actually

fabricated and put into circulation by Europeans. It seems that the occidental observers of

the Nizari Ismailis, especially those who were least informed about Islam and the Near

East, generated these legends (initially in reference to the Syrian Nizaris) gradually and

systematically, adding further components or embellishments in successive stages during

the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. In this process, the westerners, who in the Crusaders

times had a high disposition towards imaginative and romantic eastern tales, were greatly

influenced by the biases and the general hostility of the non-Ismaili Muslims towards the

Ismailis, hostility which had earlier given rise to the anti-Ismaili black legend of the Sunni

polemicists as well as some popular misconceptions about the Ismailis. In all probability,

such popular misconceptions also circulated about the Nizaris in the non-literary local

circles of the Latin East during the Crusaders times; they would have been picked up by

the Crusaders through their contact with rural Muslims working on their estates and the

lesser educated Muslims of the towns, in addition to whatever information they could gather

indirectly through the oriental Christians. In this connection, it is significant to note that

similar legends have not been found in any of the mediaeval Islamic sources, including

contemporary histories of Syria. Indeed, educated Muslims, including their historians, did

not fantasise at all about the secret practices of the Nizaris, even though they were hostile

towards them. Similarly, those few well-informed occidental observers of the Syrian

Nizaris, such as William of Tyre, who lived in the Latin East for long periods, did not

contribute to the formation of the Assassin legends.

In sum, it seems that the legends in question, though ultimately rooted in some popular lore

and misinformation circulating locally, were actually formulated and transmitted rather

widely due to their sensational appeal by the Crusaders and other western observers of the

Nizaris; and they do, essentially, represent the imaginative constructions of these

uninformed observers.

You might also like

- Moors and Free MasonryDocument5 pagesMoors and Free MasonryNoxroy Powell0% (1)

- The Sons of The Serpent Tribe - Druze in FreemasonryDocument18 pagesThe Sons of The Serpent Tribe - Druze in FreemasonryRene Lucius100% (1)

- The Hundred Years' War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017From EverandThe Hundred Years' War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (43)

- Origin of ShrinersDocument4 pagesOrigin of ShrinersMarcus Why100% (8)

- The Masons and the Moors: The Secret Link Between Freemasonry and Islamic MysticismDocument6 pagesThe Masons and the Moors: The Secret Link Between Freemasonry and Islamic MysticismMeru Muad'Dib Massey Bey100% (1)

- Priory of Scions SanctionedDocument18 pagesPriory of Scions SanctionedShawki ShehadehNo ratings yet

- The Secret Doctrines of The AssassinsDocument18 pagesThe Secret Doctrines of The AssassinsghostesNo ratings yet

- Homosexuality and Enslaved Sex and Gender in Umayyad IberiaDocument25 pagesHomosexuality and Enslaved Sex and Gender in Umayyad Iberiausername444No ratings yet

- The Masons and The Moors - New Dawn - The World's Most Unusual MagazineDocument6 pagesThe Masons and The Moors - New Dawn - The World's Most Unusual MagazineIfe100% (1)

- Postcolonialism and Orientalism in AladdinDocument9 pagesPostcolonialism and Orientalism in Aladdinmilos100% (1)

- Brethren of Purity: On Magic I ForewardDocument9 pagesBrethren of Purity: On Magic I ForewardShahid.Khan19820% (2)

- Introduction: The Assassin Legends: Myths of The IsmailisDocument7 pagesIntroduction: The Assassin Legends: Myths of The IsmailisShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- Western Views of Islam - OrientalistDocument248 pagesWestern Views of Islam - OrientalistMilli Görüş Mücahidi100% (1)

- Ginan PDFDocument476 pagesGinan PDFselma samnani100% (8)

- Visions of Heaven and Hell in Late Antiquity TextsDocument14 pagesVisions of Heaven and Hell in Late Antiquity Textsyadatan100% (1)

- Shi'i Ismaili Interpretations of The Holy Qur'an - Azim NanjiDocument7 pagesShi'i Ismaili Interpretations of The Holy Qur'an - Azim NanjiHussain HatimNo ratings yet

- Ismaili Literature in Persian and ArabicDocument15 pagesIsmaili Literature in Persian and ArabicShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- Poetics of Religious ExperienceDocument81 pagesPoetics of Religious ExperienceShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- Islam and Arabs in East AfricaDocument103 pagesIslam and Arabs in East AfricaNati ManNo ratings yet

- Elnazarov Hakim Nizari Ismailis of Central Asia in Modern TimesDocument31 pagesElnazarov Hakim Nizari Ismailis of Central Asia in Modern TimesKainat AsadNo ratings yet

- Pan IslamismDocument92 pagesPan IslamismNadhirah BaharinNo ratings yet

- Avicenna HisLifeAndWorkssoheilMAfnanDocument303 pagesAvicenna HisLifeAndWorkssoheilMAfnanarrukin1100% (1)

- Between Metaphor and Context: The Nature of The Fatimid Ismaili Discourse On Justice and InjusticeDocument7 pagesBetween Metaphor and Context: The Nature of The Fatimid Ismaili Discourse On Justice and InjusticeShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- The Medieval Ismailis of The Iranian LandsDocument31 pagesThe Medieval Ismailis of The Iranian LandsShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- Islamic Law and Slavery in Premodern West AfricaDocument20 pagesIslamic Law and Slavery in Premodern West Africasahmadouk7715No ratings yet

- Elizabeth Urban - Conquered Populations in Early Islam - Non-Arabs, Slaves and The Sons of Slave Mothers-Edinburgh University Press (2020)Document228 pagesElizabeth Urban - Conquered Populations in Early Islam - Non-Arabs, Slaves and The Sons of Slave Mothers-Edinburgh University Press (2020)Abduljelil Sheh Ali KassaNo ratings yet

- Memoirs of A MissionDocument181 pagesMemoirs of A MissionAltafNo ratings yet

- Islam: Empire of Faith, A PBS DocumentaryDocument4 pagesIslam: Empire of Faith, A PBS Documentarybassam.madany9541No ratings yet

- Bismillah Walhamdulillah Was Salaatu Was SalaamDocument42 pagesBismillah Walhamdulillah Was Salaatu Was SalaamJojo HohoNo ratings yet

- Carol Hillenbrand-The Crusade PerspectiveDocument74 pagesCarol Hillenbrand-The Crusade PerspectiveAleksandre Roderick-Lorenz100% (2)

- The Sacred Music of IslamDocument26 pagesThe Sacred Music of IslamShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- (Farhad Daftary) Ismailis in Medieval Muslim SocieDocument272 pages(Farhad Daftary) Ismailis in Medieval Muslim SocieCelia DanieleNo ratings yet

- Taqwa-From Encyclopaedia of IslamDocument9 pagesTaqwa-From Encyclopaedia of IslamShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- Syrian Episodes: Sons, Fathers, and an Anthropologist in AleppoFrom EverandSyrian Episodes: Sons, Fathers, and an Anthropologist in AleppoRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (7)

- Making the Modern Middle East: Second EditionFrom EverandMaking the Modern Middle East: Second EditionRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Muslim Philosophy and The Sciences - Alnoor Dhanani - Muslim Almanac - 1996Document19 pagesMuslim Philosophy and The Sciences - Alnoor Dhanani - Muslim Almanac - 1996Yunis IshanzadehNo ratings yet

- Khalil Et Al-2016-Sufism in Western HistoriographyDocument25 pagesKhalil Et Al-2016-Sufism in Western Historiographybhustlero0oNo ratings yet

- 1 AsasiniDocument8 pages1 AsasiniBoban MarjanovicNo ratings yet

- Speculum: A Journal of Mediaeval StudiesDocument23 pagesSpeculum: A Journal of Mediaeval StudiesAsra IsarNo ratings yet

- Basics of True Islam ExplainedDocument110 pagesBasics of True Islam ExplainedUsama IlyasNo ratings yet

- 6 Great Converts To IslamDocument5 pages6 Great Converts To Islambradia_03686330No ratings yet

- (15700607 - Die Welt Des Islams) Michael Winter (1934-2020)Document6 pages(15700607 - Die Welt Des Islams) Michael Winter (1934-2020)n2xwg5z4bmNo ratings yet

- Approaching The Qur An in Sub Saharan AfDocument23 pagesApproaching The Qur An in Sub Saharan AfEmad Abd ElnorNo ratings yet

- The AssassinsDocument11 pagesThe AssassinsWF1900No ratings yet

- Representations of Elite Ottoman WomenDocument42 pagesRepresentations of Elite Ottoman Womendeniz alacaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Thomas Arnolds PreachingDocument85 pagesIntroduction To Thomas Arnolds PreachingSehar AslamNo ratings yet

- 06 - Chapter 1Document25 pages06 - Chapter 1MuhammedNo ratings yet

- A Short History of The IsmailisDocument30 pagesA Short History of The IsmailisAbbas100% (1)

- Jamal Ud Din AfghaniDocument8 pagesJamal Ud Din AfghaniMaryam Siddiqa Lodhi LecturerNo ratings yet

- Hashashin (Hassisi) (Asesinos)Document8 pagesHashashin (Hassisi) (Asesinos)Gonn LLeNo ratings yet

- The Alamiit Period in Nizari Ismaili HistoryDocument39 pagesThe Alamiit Period in Nizari Ismaili HistoryA.A. OsigweNo ratings yet

- Al AndalusDocument4 pagesAl Andalusnereacarreroc14No ratings yet

- Eunuchs in Islamic CivilizationDocument2 pagesEunuchs in Islamic CivilizationdrwlnobNo ratings yet

- Modern Trends in Sirah WritingsDocument19 pagesModern Trends in Sirah Writingsekinymm9445No ratings yet

- Review - Iraq After The Muslim ConquestDocument2 pagesReview - Iraq After The Muslim ConquestSepide HakhamaneshiNo ratings yet

- Historique de La Family Swaray - WilkipediaDocument6 pagesHistorique de La Family Swaray - WilkipediamustaphaNo ratings yet

- Calls For Jihad in MauritiusDocument6 pagesCalls For Jihad in MauritiusmeltNo ratings yet

- Hintze 2002Document110 pagesHintze 2002Sajad AmiriNo ratings yet

- A Short History of The Ismailis - Reading GuideDocument13 pagesA Short History of The Ismailis - Reading Guiderahimdad mukhtariNo ratings yet

- Charles River Editors - The Moors in Italy - The History of The Muslims Who Moved From North Africa To Italy During The Middle Ages-Charles River Editors (2023)Document44 pagesCharles River Editors - The Moors in Italy - The History of The Muslims Who Moved From North Africa To Italy During The Middle Ages-Charles River Editors (2023)walid princoNo ratings yet

- ReligionDocument248 pagesReligionKashif Imran100% (2)

- Ibn Khaldun's Encounters and Insights as a Medieval HistorianDocument30 pagesIbn Khaldun's Encounters and Insights as a Medieval HistorianBlack Thorn League Radio CrusadeNo ratings yet

- Middle East Book ReviewsDocument20 pagesMiddle East Book ReviewsRobert W. Lebling Jr.No ratings yet

- Unit 3 - Almohads and AlmoravidsDocument6 pagesUnit 3 - Almohads and AlmoravidsAKASH SINGHNo ratings yet

- Orientalism & Literature Edward SaidDocument5 pagesOrientalism & Literature Edward SaidsarahNo ratings yet

- Talmudic Text Iranian ContextDocument13 pagesTalmudic Text Iranian ContextShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- The Philosophy of Mediation: Questions and Responses From Diverse Parts of The World and Especially From The Islamic TraditionDocument6 pagesThe Philosophy of Mediation: Questions and Responses From Diverse Parts of The World and Especially From The Islamic TraditionShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- Ethics and Aesthetics in Islamic ArtsDocument4 pagesEthics and Aesthetics in Islamic ArtsShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- Timurids - From Medieval Islamic Civilization, An EncyclopaediaDocument3 pagesTimurids - From Medieval Islamic Civilization, An EncyclopaediaShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- Quranic ExpressionsDocument7 pagesQuranic Expressionsali_shariatiNo ratings yet

- The Shia Ismaili Muslims - An Historical ContextDocument5 pagesThe Shia Ismaili Muslims - An Historical ContextShahid.Khan1982100% (1)

- "Plato, Platonism, and Neo-Platonism" From Medieval Islamic Civilization: An EncyclopaediaDocument3 pages"Plato, Platonism, and Neo-Platonism" From Medieval Islamic Civilization: An EncyclopaediaShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- Beyond The Exotic: The Pleasures of Islamic ArtDocument5 pagesBeyond The Exotic: The Pleasures of Islamic ArtShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- Philosophical Remarks On ScriptureDocument16 pagesPhilosophical Remarks On ScriptureShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- The Ismailis and Their Role in The History of Medieval Syria and The Near EastDocument12 pagesThe Ismailis and Their Role in The History of Medieval Syria and The Near EastShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- Tawakkul-From The Encyclopaedia of IslamDocument5 pagesTawakkul-From The Encyclopaedia of IslamShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- The Days of Creation in The Thought of Nasir KhusrawDocument10 pagesThe Days of Creation in The Thought of Nasir KhusrawShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- Optics From Medieval Islamic Civilization, An EncyclopaediaDocument3 pagesOptics From Medieval Islamic Civilization, An EncyclopaediaShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- Ismailism (From Islamic Spirituality: Foundations)Document18 pagesIsmailism (From Islamic Spirituality: Foundations)Shahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- On Pluralism, Intolerance, and The Qur'anDocument8 pagesOn Pluralism, Intolerance, and The Qur'anShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- A Changing Religious Landscape: Perspectives On The Muslim Experience in North AmericaDocument13 pagesA Changing Religious Landscape: Perspectives On The Muslim Experience in North AmericaShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- Mysticism and PluralismDocument3 pagesMysticism and PluralismShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- Muslim Ethics: Chapter 1-Taking Ethics SeriouslyDocument24 pagesMuslim Ethics: Chapter 1-Taking Ethics SeriouslyShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- "Muslim, Jews and Christians" The Muslim AlmanacDocument9 pages"Muslim, Jews and Christians" The Muslim AlmanacShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- Beyond The Clash of CivilizationsDocument6 pagesBeyond The Clash of CivilizationsShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- " On Muslims Knowing The "Muslim" Other: Reflections On Pluralism and Islam"Document9 pages" On Muslims Knowing The "Muslim" Other: Reflections On Pluralism and Islam"Shahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- The Mediator As A Humanising Agent: Some Critical Questions For ADR TodayDocument9 pagesThe Mediator As A Humanising Agent: Some Critical Questions For ADR TodayShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- Multiculturalism and The Challenges It Poses To Legal Education and Alternative Dispute Resolution: The Situation of British Muslims'Document9 pagesMulticulturalism and The Challenges It Poses To Legal Education and Alternative Dispute Resolution: The Situation of British Muslims'Shahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- 1440H CALENDARDocument15 pages1440H CALENDARwaheed anjumNo ratings yet

- Hashashin (Hassisi) (Asesinos)Document8 pagesHashashin (Hassisi) (Asesinos)Gonn LLeNo ratings yet

- Series 32 - 1945 - Umiya Mataji Vandhay Mandir - InaugurationDocument55 pagesSeries 32 - 1945 - Umiya Mataji Vandhay Mandir - InaugurationsatpanthNo ratings yet

- Calender India PDFDocument14 pagesCalender India PDFMurtaza MustafaNo ratings yet

- Series 17A - Gujarati Dictionary - BhagwadgomandalDocument2 pagesSeries 17A - Gujarati Dictionary - BhagwadgomandalsatpanthNo ratings yet

- Hassan I SabbahDocument9 pagesHassan I SabbahfawzarNo ratings yet

- Wikipedia, Satpanth & Pirana's Akhand JyotDocument4 pagesWikipedia, Satpanth & Pirana's Akhand Jyotએક વ્યક્તિNo ratings yet

- OE 33 - Chhabhaiya Parivar Boycotts SatpanthDocument2 pagesOE 33 - Chhabhaiya Parivar Boycotts SatpanthsatpanthNo ratings yet

- Series 7 - Pirana Satpanth Ni Pol Ane Satya No PrakashDocument580 pagesSeries 7 - Pirana Satpanth Ni Pol Ane Satya No PrakashsatpanthNo ratings yet

- Jadwal Imam TarawihDocument16 pagesJadwal Imam Tarawihmat rukunNo ratings yet

- Series 38 - Pirana Site and Location Map & PhotosDocument19 pagesSeries 38 - Pirana Site and Location Map & PhotossatpanthNo ratings yet

- Fatimids - Encyclopaedia IranicaDocument8 pagesFatimids - Encyclopaedia IranicaShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- Series 42 - Views of Pirana Satpanth's Main Insider - Swadhyay Pothi Yane Gyan GostiDocument26 pagesSeries 42 - Views of Pirana Satpanth's Main Insider - Swadhyay Pothi Yane Gyan GostisatpanthNo ratings yet

- Hospital ListDocument3 pagesHospital Listims10% (1)

- Age 0 - 10Document18 pagesAge 0 - 10aliasgharmithaiwala448No ratings yet

- Kahak (The Encyclopaedia Iranica Online)Document4 pagesKahak (The Encyclopaedia Iranica Online)Shahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- Series 48 - Gujarati Vishvakosh - EncyclopediaDocument18 pagesSeries 48 - Gujarati Vishvakosh - EncyclopediasatpanthNo ratings yet

- Series 54 - Mulband (Fake) - Full DownloadDocument2 pagesSeries 54 - Mulband (Fake) - Full DownloadsatpanthNo ratings yet

- OE 30 - ABKKP Samaj - Letter DT 18-01-2011 - Taking Strict ActionDocument3 pagesOE 30 - ABKKP Samaj - Letter DT 18-01-2011 - Taking Strict ActionsatpanthNo ratings yet

- Series 52 - Shankaracharyaji & Sadhu Samajs Declare Satpanth As Muslim ReligionDocument10 pagesSeries 52 - Shankaracharyaji & Sadhu Samajs Declare Satpanth As Muslim ReligionsatpanthNo ratings yet

- Special report on the redevelopment of Mumbai's crowded Bhendi Bazaar market into swanky high-risesDocument2 pagesSpecial report on the redevelopment of Mumbai's crowded Bhendi Bazaar market into swanky high-risesAmit K. YadavNo ratings yet

- DUBAIDocument5 pagesDUBAIKhadija ujjainwalaNo ratings yet

- 1985 09 07 Amrutvani276 Clean DDocument138 pages1985 09 07 Amrutvani276 Clean Dpraxd designNo ratings yet

- Isma'ilismDocument22 pagesIsma'ilismT 4No ratings yet

- Series 49 - Mirate Ahmadi - Historical Records On Imam Shah and Role of KakaDocument7 pagesSeries 49 - Mirate Ahmadi - Historical Records On Imam Shah and Role of KakasatpanthNo ratings yet

- Series 61 - Bhoomidag - Atharv Ved's Wrong InterpretationDocument33 pagesSeries 61 - Bhoomidag - Atharv Ved's Wrong InterpretationsatpanthNo ratings yet

- The Institute of Ismaili Studies: Encyclopaedia IranicaDocument3 pagesThe Institute of Ismaili Studies: Encyclopaedia IranicaShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet