Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Modified Rapidseq

Uploaded by

zaheermechOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Modified Rapidseq

Uploaded by

zaheermechCopyright:

Available Formats

AANA Journal/August 2001/Vol. 69, No.

4 291

Introduction

R

apid-sequence induction

(RSI) is a commonly used

anesthetic technique for

patients considered at risk

for regurgitation and pul-

monary aspiration. This technique con-

sists of preoxygenation, cricoid pressure,

and the avoidance of postive-pressure

ventilation until the airway has been

secured with an endotracheal tube.

Patients at risk for aspiration include

those with full stomachs and patients

with a history of gastrointestinal surgery,

hiatal hernia, gastroesophageal reflux

disease, esophageal motility disorders,

hyperchlorhydria, peptic ulcer, obesity,

or diabetes mellitus.

1

Although RSI is well established in

anesthetic practice, it is not without

possible risk to the patient. The most

alarming risk is the potential inability

to secure an airway or to ventilate a

patient who is unconscious and apneic.

The decision to use RSI needs to be

based on a thorough assessment of a

patients potential risk of aspiration and

the potential risks associated with RSI.

Potential risks of RSI include inability

to ventilate leading to hypoxia and

hypercarbia, alteration in heart rate and

blood pressure, and trauma to the air-

way. These risks may not be warranted

or appropriate for a patient at minimal

risk of regurgitation and aspiration. For

these cases, a modification of the stan-

dard RSI technique consisting of pre-

oxygenation, cricoid pressure, and gen-

tle positive-pressure ventilation before

tracheal intubation may be more appro-

priate. The purpose of this study was to

determine whether any such modifica-

tion of RSI technique is used currently

in clinical practice.

The primary objective of RSI is to

minimize the time between patient loss

of consciousness and tracheal intuba-

tion. RSI is a standard technique con-

sisting of preoxygenation and cricoid

pressure.

2

Positive-pressure ventilation

generally is avoided until the airway is

secured with an endotracheal tube,

unless attempts at intubation are

unsuccessful or desaturation occurs.

Considerable variation, however, exists

among anesthesia providers in the use

of this technique. Variability exists in

the duration of preoxygenation; the

selection, dosage, and timing of admin-

istration of the induction agent and

muscle relaxant; the use of adjunct

medications; the application of cricoid

pressure; and the management of a

failed intubation.

2

Preoxygenation is a standard com-

ponent of RSI.

2

According to basic

anesthetic texts, preoxygenation on

high fresh gas flows of 100% oxygen

via face mask with a good mask fit for

3 to 5 minutes is recommended. Alter-

natively, a series of 4 vital capacity

breaths of 100% oxygen may be used in

an emergency.

3,4

Sodium thiopental is selected most

frequently as the induction agent in

RSI.

2

Other agents used include keta-

mine,

5

etomidate,

6

and propofol.

7

Suc-

cinylcholine has long been considered

the gold standard muscle relaxant for

RSI, but adverse effects such as

arrhythmias, hyperkalemia, and fascic-

ulations may preclude its safe use in

certain situations such as burn injury

or spinal cord injury. Other muscle

relaxants that can be considered

include vecuronium

8-10

and rocuro-

nium.

6,10-12

Nondepolarizing muscle

relaxants, however, have a significantly

longer duration of action than suc-

The purpose of this study was to

identify the use of rapid-sequence

induction (RSI) and its hybrids. For

the study, 67 Certified Registered

Nurse Anesthetists at 1 hospital

completed a survey describing

their experience using a modified

technique for patients with a mod-

erately increased risk of regurgita-

tion and aspiration. Patient selec-

tion criteria and the use of

aspiration prophylaxis, preoxy-

genation, cricoid pressure, and

positive-pressure ventilation were

evaluated. In contrast with routine

induction and standard RSI tech-

niques, the modified RSI technique

consisted of aspiration prophy-

laxis, preoxygenation, application

of cricoid pressure, and positive-

pressure ventilation. The survey

revealed that a modification of

standard RSI is used commonly in

clinical practice. These modified

RSI techniques are not standard-

ized, as variation was noted in the

delivery of positive pressure venti-

lation. Further study is necessary

to identify widespread use of mod-

ified RSI techniques and to clarify

the risks and benefits of modified

RSI.

Key words: Modified rapid-se-

quence induction, preoxygenation,

cricoid pressure, positive-pressure

ventilation.

Modified rapid-sequence induction of

anesthesia: A survey of current

clinical practice

Stacey Schlesinger, CRNA, MSN,

MBA

Statesville, North Carolina

Diane Blanchfield, CRNA, MS

Charlotte, North Carolina

292 AANA Journal/August 2001/Vol. 69, No. 4

cinylcholine and could prove disastrous if a patient

could not be adequately ventilated or intubated. Non-

depolarizing muscle relaxants also may be undesir-

able for surgical procedures of short duration.

The timing of administration of the induction

agent in relation to the muscle relaxant in RSI also

seems to be variable. In 1 study of 210 anesthetists,

the muscle relaxant was administered immediately

after the induction agent by 46.5% of anesthetists,

after loss of lid reflex by 38% of anesthetists, and after

loss of verbal contact by 15% of anesthetists.

2

Other

descriptions of RSI include administration of muscle

relaxant 5 seconds after administration of the induc-

tion agent

5

or even before administration of the induc-

tion agent.

8,9

In any event, the rapid administration of

a barbiturate with an alkaline pH and a muscle relax-

ant with an acidic pH can result in immediate and

substantial precipitation and occlusion of the intra-

venous line.

13-15

The loss of intravenous access after a

patient loses consciousness and protective airway

reflexes might prove disastrous.

Another key component of RSI is the application of

cricoid pressure. Cricoid pressure consists of com-

pression and occlusion of the esophagus in an attempt

to minimize the risk of regurgitation. Cricoid pressure

has been demonstrated to prevent air entry into the

stomach as long as a patent airway is maintained.

16

Excessive force applied to the cricoid cartilage can

obstruct the airway and interfere with successful tra-

cheal intubation. Possible complications of cricoid

pressure include difficult tracheal intubation, airway

obstruction, pulmonary aspiration, and esophageal

rupture.

17

Other unusual but reported complications

include bilateral subconjunctival hemorrhage from a

patient bucking against cricoid pressure

18

and cricoid

cartilage fracture.

19

Positive-pressure ventilation generally is avoided to

prevent aspiration and gaseous distention of the stom-

ach in RSI.

16

This, however, precludes the ability to

test the airway and verify that a patient can be ven-

tilated by mask before the administration of a muscle

relaxant. This also mandates a period of apnea that

may not be well tolerated by patients with compro-

mised respiratory status or increased baseline oxygen

requirements.

The use of a modified RSI technique would allow

for a patient to be gently ventilated by mask before the

insertion of an endotracheal tube. Positive-pressure

ventilation via a face mask could be provided before

administration of a muscle relaxant to test the airway

in patients with an airway assessed as marginal. Alter-

natively, positive-pressure ventilation via a face mask

could be provided before and after administration of a

muscle relaxant for patients unable to tolerate the

brief period of apnea associated with RSI. An exten-

sive review of the literature, however, has revealed no

descriptions of a modified RSI technique for these

patients.

Materials and methods

This descriptive study consisted of a survey of Certi-

fied Registered Nurse Anesthetists (CRNAs) em-

ployed at a large tertiary care hospital located in the

southeastern United States. The anesthetists were

asked to complete a survey describing their experi-

ence performing both RSI and modifications of RSI in

their clinical practice. CRNAs who reported having

used a modified RSI technique were asked additional

questions to determine how patients were selected

and whether preoxygenation, cricoid pressure, and

positive-pressure ventilation were used. One of the

investigators (S.S.) developed the data collection tool

for the sole purpose of this study.

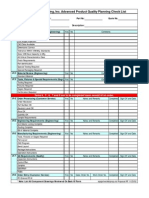

The survey (Figure 1) included 4 basic questions

on the anesthetists experience, practice setting, and

use of RSI and modified RSI techniques. CRNAs who

reported using a modified RSI technique in clinical

practice were asked 5 additional questions regarding

patient selection, provision of prophylaxis for aspira-

tion pneumonia, preoxygenation, cricoid pressure,

and positive-pressure ventilation.

Institutional review board approval was obtained

before the distribution of surveys to all employed

CRNAs in the inpatient and outpatient operating

rooms. Responses were compiled and analyzed to

identify the frequency of clinical use of RSI and mod-

ified RSI techniques, CRNA experience, and clinical

practice setting. For CRNAs who reported using a

modified RSI technique in clinical practice, further

review of the data identified patient selection consid-

erations and the anesthetists definition of the modi-

fied RSI technique.

Results

Of 84 surveys distributed, 67 were returned for an

overall response rate of 80%; 31 CRNAs (46%) had

more than 10 years of clinical experience, 21 (31%) had

5 to 10 years of experience, and 15 (22%) had fewer

than 5 years of experience. Of the 65 respondents who

answered question 2 (type of practice setting), 51

(78%) were employed primarily in the inpatient oper-

ating room, while 14 (22%) were employed primarily

in the outpatient department (Figures 2 and 3).

Nearly all respondents reported using both RSI and

modified RSI techniques in their clinical practice

(Figure 4). The reported use of a standard RSI tech-

AANA Journal/August 2001/Vol. 69, No. 4 293

Modified rapid-sequence induction (RSI) techniques

A Survey of Current Clinical Practice

RSI is a commonly used procedure in patients with full stomachs to minimize the risk of regurgitation and aspiration.

Standard components of RSI are preoxygenation, cricoid pressure and the avoidance of positive pressure ventilation via face

mask until an endotracheal tube is placed. In some circumstances, a modification of this rapid-sequence technique may be

warranted. The purpose of this questionnaire is to identify the clinical definition of modified RSI.

Please select the response that most closely reflects your current clinical practice.

1. Years anesthesia experience __< 5 years __5-10 years __> 10 years

2. Type of practice setting __ Inpatient operating room __ Outpatient operating room

3. In my clinical practice, I currently use RAPID-SEQUENCE INDUCTION (RSI)

__Never __ Rarely __Occasionally __Often __Always

4. In my clinical practice, I currently use MODIFIED RSI

__Never __Rarely __Occasionally __Often __Always

If you have NEVER used a modified RSI technique in your clinical practice, THANK YOU for your participation.

If you have used a MODIFIED RSI technique, please answer the following questions.

5. Patients that I have utilized a MODIFIED RSI technique upon include: (check all that apply)

__ Moderately obese patients

__ Morbidly obese patients

__ Diabetic patients with no clinical symptoms of reflux disease

__ Patients with a history of prior esophageal surgery

__ Patients with a history of GERD but with no recent symptoms

__Other. Please explain:__________________________________________________

6. Based on your definition of modified RSI, is aspiration prophylaxis appropriate?

___ No ___ Yes If Yes, your usual management is: (check all that apply)

__Premedication with sodium citrate

__Premedication with metoclopramide

__Premedication with H

2

antagonist

__Other: _____________________________ (please specify)

7. Based on your definition of Modified RSI, is preoxygenation required prior to induction?

___ No ___ Yes If Yes, for how long? (select the best answer)

__PreO

2

on 100% > 5 min

__PreO

2

on 100% 3-5 min

__PreO

2

on 100% < 3 min

__PreO

2

on 100% 4 vital capacity breaths

8. Based on your definition of modified RSI, is the application of cricoid pressure necessary?

___ No ___ Yes If yes, when is it applied? (select the best answer)

__Prior to induction agent

__At the same time as induction agent

__After loss of lid reflex

__After loss of verbal contact

9. Based on your definition of modified RSI, is an attempt to ventilate via face mask appropriate?

___ No ___ Yes If yes, when do you attempt to ventilate? (select the best answer)

__PRIOR to administration of a muscle relaxant

__FOLLOWING administration of muscle relaxant

__BOTH before and after administration of muscle relaxant

Figure 1. Survey*

*GERD indicates gastroesophageal reflux disease; PreO

2

indicates preoxygenation.

294 AANA Journal/August 2001/Vol. 69, No. 4

nique was described as often by 45 (67%) and

occasional by 20 (30%). Only 2 respondents (3%)

reported never or rarely having used a standard

RSI technique. No CRNA reported always using a

standard RSI technique.

Of the respondents, 65 (97%) reported they have

used a modified RSI technique in their clinical prac-

tice. The use of this technique was described as occa-

sional by 42 (63%), often by 19 (28%), and

always by 1 (1%). Only 3 (4%) reported rarely

using a modified RSI technique.

The 65 CRNAs who reported using a modified RSI

technique were asked to answer 5 additional ques-

tions on the survey. Five patient scenarios were

described, and the anesthetists were asked to identify

those in which they had used a modified RSI tech-

nique for the induction of general anesthesia. A total

of 57 respondents (88%) reported they had used a

modified RSI technique for patients with moderate

obesity, while 23 (35%) reported its use for patients

with morbid obesity. In addition, 43 respondents

(66%) reported they had used modified RSI for

patients with diabetes who had no current signs and

symptoms of reflux disease. For patients with a his-

tory of esophageal surgery, 18 (28%) responded they

had used a modified RSI technique. For patients with

a history of gastroesophageal reflux disease but no

recent symptoms, 48 respondents (74%) reported

using a modified RSI technique. These findings are

summarized in Figure 5.

CRNAs also were asked to identify any other

patient situations in which they had used a modified

RSI technique (Table).

The remaining survey questions addressed the spe-

cific components of a modified RSI technique. The

0

25

50

75

100

> 10 5-10 < 5

Years of clinical experience

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

a

g

e

o

f

r

e

s

p

o

n

s

e

s

21(31%)

15(22%)

31(46%)

Figure 2. Reported experience of Certified Registered

Nurse Anesthetists (N=67)*

Inpatient

operating room

Outpatient

operating room

Clinical practice setting

14(22%)

51(78%)

Figure 3. Reported primary employment setting

(n=65)

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Modified

RSI

RSI

Always Often Occasion-

ally

Rarely Never

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

a

g

e

o

f

r

e

s

p

o

n

s

e

s

1% 0%

67%

28%

63%

30%

4%

1%

3%

1%

How often technique is used

Figure 4. Use of standard rapid-sequence induction

(RSI) and modified RSI techniques in clinical practice

(N=67)*

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

History of

gastroesophageal

reflux disease but

no current signs

and symptoms

Prior

esoph-

ageal

surgery

Diabetes,

no signs

and

symptoms

of reflux

Morbid

obesity

Moderate

obesity

Indication

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

a

g

e

o

f

r

e

s

p

o

n

s

e

s

88%

35%

66%

28%

74%

Figure 5. Modified rapid-sequence induction

indications (n=65)

*Due to rounding, percentages may not add up to 100%.

*Due to rounding, percentages may not add up to 100%.

AANA Journal/August 2001/Vol. 69, No. 4 295

preoperative administration of medication to alter

gastric pH and/or gastrointestinal motility (aspiration

pneumonia prophylaxis) was reported by 55 (85%) of

the CRNAs who reported using a modified RSI tech-

nique. Regarding their choice of drug administration,

52 (95%) of these 55 respondents administered H

2

receptor antagonists, 49 (89%) administered metoclo-

pramide, and 2 (4%) administered sodium citrate.

These data are summarized in Figure 6. No other

medications were identified as being administered as

part of a modified RSI.

Preoxygenation is another key component of stan-

dard RSI and possibly of modified RSI. Of the CRNAs

who have used a modified RSI technique, 63 (97%)

reported that preoxygenation is required before

induction. Of those respondents, 61 reported meth-

ods (Figure 7), which included preoxygenation on

100% FIO

2

(fraction of inspired oxygen) for 3 to 5

minutes (31 [51%]), for 4 vital capacity breaths (13

[21%]), for fewer than 3 minutes (11 [18%]), and for

more than 5 minutes (6 [10%]).

Cricoid pressure is another usual component of

both standard and modified RSI. A total of 62 CRNAs

(95%) who have used a modified RSI technique

reported that the application of cricoid pressure is

necessary. Of the respondents (n=57) who reported

when cricoid pressure is applied, 40 (70%) reported

that cricoid pressure was applied at the same time as

administration of the induction agent. Other re-

sponses included before administration of the induc-

tion agent (11 [19%]), after loss of lid reflex (3 [5%]),

and following loss of verbal contact (3 [5%]). These

data are summarized in Figure 8.

In standard RSI, positive-pressure ventilation is

avoided until the airway is secured. Of those using a

modified RSI technique, 61 (94%) reported that an

attempt to ventilate via a face mask is appropriate. Of

Patient at risk for desaturation but RSI is indicated

Trauma patient who has been NPO for 8 h

End-stage renal disease without symptoms of GERD

Patient for heart surgery with GERD

Consistent history of reflux

Patient >24 h postpartum

Patient who is >5 mo pregnant

Inhalation induction

Table. Other proposed indications for modified

rapid-sequence induction (RSI)*

*GERD indicates gastroesophageal reflux disease; NPO indicates nothing by

mouth.

0

25

50

75

100

Metoclopramide H

2

receptor

antagonist

Sodium citrate

Method

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

a

g

e

o

f

r

e

s

p

o

n

s

e

s

52 (95%)

2 (4%)

49 (89%)

Figure 6. Methods of prophylaxis for aspiration

pneumonia in modified rapid-sequence induction

(n=55)

0

25

50

75

100

4 vital

capacity

breaths

< 3

minutes

3-5

minutes

> 5

minutes

Duration

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

a

g

e

o

f

r

e

s

p

o

n

s

e

s

31 (51%)

6 (10%)

11 (18%)

13 (21%)

Figure 7. Duration of preoxygenation in modified

rapid-sequence induction (n=61)

0

25

50

75

100

After loss

of verbal

contact

After loss

of lid

reflex

Same time

as induction

agent

Before

induction

agent

Timing of cricoid pressure

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

a

g

e

o

f

r

e

s

p

o

n

s

e

s

40 (70%)

11 (19%)

3 (5%) 3 (5%)

Figure 8. Timing of the application of cricoid pressure

in modified rapid-sequence induction (n=57)

296 AANA Journal/August 2001/Vol. 69, No. 4

the respondents who reported when they attempt to

ventilate (n = 60), 30 (50%) reported that they did so

both before and after administration of a muscle

relaxant. An additional 13 (22%) reported providing

positive-pressure ventilation before administration of

a muscle relaxant, and 17 (28%) reported providing

positive-pressure ventilation following administration

of a muscle relaxant. These data are summarized in

Figure 9.

Discussion

The analysis of the data confirms that a modified RSI

technique often is used by CRNAs in clinical practice

at 1 institution. As shown in Figure 10, the modified

RSI technique most often consists of pharmacological

prophylaxis, preoxygenation, cricoid pressure, and

positive-pressure ventilation. This differs from a stan-

dard RSI technique, which does not include positive-

pressure ventilation, and from a routine induction,

which does not include aspiration prophylaxis or

cricoid pressure.

Although survey respondents were CRNAs with

varying experience from inpatient and outpatient set-

tings, the reported use of standard RSI and modified

RSI was consistent among all practioners (Figures 11

and 12). It is important to note that most of the anes-

thetists surveyed graduated from the same nurse anes-

thesia training program.

Patients selected for the modified RSI technique

included those in whom the relative risks of regurgi-

tation and aspiration seemed to be less than the risks

associated with the use of standard RSI. These include

moderately obese patients and patients with underly-

ing gastroesophageal reflux disease or a disease

process (diabetes, renal failure) associated with gas-

troesophageal reflux disease but who have no current

symptoms. The low reported use of modified RSI for

patients with morbid obesity or who have undergone

esophageal surgery most likely reflects a tendency to

select a standard RSI technique for these patients.

There were some differences among clinicians in

the specific application of each component of modi-

fied RSI. Variation was demonstrated in the duration

of preoxygenation, the timing of application of cricoid

pressure, and the choice of preoperative medications

to alter gastrointestinal motility and gastric pH. There

was wide variation in the timing of positive-pressure

ventilation in modified RSI.

Aspiration prophylaxis was reported by most

CRNAs as part of a modified RSI. This most com-

monly consisted of the administration of an H

2

recep-

tor antagonist, metoclopramide, or both.

Preoxygenation with 100% oxygen was provided

most often for 3 to 5 minutes and was followed by the

application of cricoid pressure. Cricoid pressure gen-

erally was applied at the same time as administration

of an induction agent. The use of cricoid pressure was

reported by nearly all anesthetists as part of a modi-

fied RSI technique.

Positive-pressure ventilation is used as part of a

modified RSI technique by most CRNAs surveyed.

This represents the most substantial difference of

modified RSI with standard RSI, in which positive-

pressure ventilation generally is avoided. The timing

of positive-pressure ventilation in relation to the

administration of a muscle relaxant in modified RSI,

however, is variable. Some anesthetists reported that

they administered positive-pressure ventilation both

before and after administration of a muscle relaxant.

0

25

50

75

100

Before

and after

administration

of muscle

relaxant

Following

administration

of muscle

relaxant

Before

administration

of muscle

relaxant

Timing of positive-pressure ventilation

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

a

g

e

o

f

r

e

s

p

o

n

s

e

s

17 (28%)

13 (22%)

30 (50%)

Figure 9. Use of positive-pressure ventilation via face

mask in modified rapid-sequence induction (n=60)

0

25

50

75

100

Positive-

pressure

ventilation

Cricoid

pressure

Preoxy-

genation

Aspiration

prophylaxis

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

a

g

e

o

f

r

e

s

p

o

n

s

e

s

63 (97%)

55 (85%)

62 (95%)

61 (94%)

Components of rapid-sequence induction

Figure 10. Reported components of modified rapid-

sequence induction (n=65)

AANA Journal/August 2001/Vol. 69, No. 4 297

Other anesthetists provided positive-pressure ventila-

tion only before or only after administration of a mus-

cle relaxant. A few anesthetists reported that they did

not provide positive-pressure ventilation at any time

during modified RSI. It is unclear to the investigators

how this modified RSI technique differed from stan-

dard RSI.

The variability in the use of positive-pressure ven-

tilation may represent different objectives for individ-

ual patients in the selection of a modified RSI tech-

nique. During standard RSI, patients are made apneic

and unconscious without establishing that they can

be ventilated by mask. This theoretically avoids

gaseous distention of the stomach and subsequent

possible regurgitation and aspiration. However, if the

anesthetist subsequently is unable to intubate or ven-

tilate, results could prove disastrous. During modified

RSI, the provision of positive-pressure ventilation via

a face mask allows the anesthetist to affirm the ability

to ventilate before administering a muscle relaxant.

For patients who cannot be ventilated safely via a face

mask during modified RSI, a decision can be made

before the administration of a muscle relaxant to

reawaken the patient and proceed with an awake intu-

bation. This may be of added importance for patients

in whom succinylcholine is contraindicated, since the

resulting period of paralysis with a nondepolarizing

muscle relaxant can be substantially longer.

The modified RSI technique also may be valuable

for patients who may not tolerate even brief periods of

apnea, because careful, low-peak airway pressure ven-

tilation can be provided throughout the induction

period. The use of positive-pressure ventilation before

and after the administration of a muscle relaxant

allows the anesthetist to test the airway and avoid

desaturation.

Modified RSI seems to be an acceptable and com-

mon clinical technique for the induction of general

anesthesia in selected patients at this institution. Fur-

thermore, the modified technique seems to be well-

defined as the sequence of aspiration prophylaxis with

an H

2

receptor antagonist and metoclopramide, pre-

oxygenation with 100% oxygen for 3 to 5 minutes or

4 vital capacity breaths, application of cricoid pressure

at the same time as administration of the induction

agent, and provision of positive-pressure ventilation

before and after administration of a muscle relaxant.

As with standard RSI, there seems to be variation in

the specific application of each of these components.

The purpose of the present study was to determine

whether a modified RSI technique is used in clinical

practice for the induction of general anesthesia. Fur-

ther study is warranted to evaluate the use of a modi-

fied RSI technique in other clinical settings and to

determine the safety and efficacy of the technique.

REFERENCES

1. Mallampati SR. Airway management. In: Barash PG, Cullen BF,

Stoelting RK, eds. Clinical Anesthesia. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-

Raven; 1997:573-594.

2. Thwaites AJ, Rice CP, Smith I. Rapid sequence induction: a ques-

tionnaire survey of its routine conduct and continued manage-

ment during a failed intubation. Anaesthesia. 1999;54:376-381.

3. Santos AC, Pederson H, Finster M. Obstetric anesthesia. In: Barash

PG, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK, eds. Clinical Anesthesia. Philadelphia

PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1997:1061-1090.

4. Chipas A. Airway management. In: Nagelhout JJ, Zaglaniczny KL,

eds. Nurse Anesthesia. Philadelphia PA: WB Saunders; 1997:708-

725.

5. Baraka AS, Sayyid SS, Assaf BA. Thiopental-rocuronium versus ket-

amine-rocuronium for rapid-sequence intubation in parturients

0

25

50

75

100

> 10 y (n=31)

5-10 y (n=21)

< 5 y (n=15)

Always Often Occasion-

ally

Rarely Never

Frequency of RSI

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

a

g

e

o

f

r

e

s

p

o

n

s

e

s

Figure 11. Reported use of standard rapid-sequence

induction (RSI) by length of Certified Registered

Nurse Anesthetist experience

0

25

50

75

100

>10y (n=31)

5-10 y (n=21)

<5 y (n=15)

Always Often Occasion-

ally

Rarely Never

Frequency of modified RSI

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

a

g

e

o

f

r

e

s

p

o

n

s

e

s

Figure 12. Reported use of modified rapid-sequence

induction (RSI) by length of Certified Registered

Nurse Anesthetist experience

298 AANA Journal/August 2001/Vol. 69, No. 4

undergoing cesarean section. Anesth Analg. 1997;84:1104-1107.

6. Fuchs-Buder T, Sparr HJ, Ziegenfub T. Thiopental or etomidate for

rapid sequence induction with rocuronium. Br J Anaesth. 1998;

80:504-506.

7. Wright PMC, Caldwell JE, Miller RD. Onset and duration of

rocuronium and succinylcholine at the adductor pollicis and

laryngeal adductor muscles in anesthetized humans. Anesthesiol-

ogy. 1994;81:1110-1115.

8. Cicala R, Westbrook L. An alternative method of paralysis for

rapid sequence induction. Anesthesiology. 1988;69:983-986.

9. Silverman SM, Culling RD, Middaugh RE. Rapid-sequence orotra-

cheal intubation: a comparison of three techniques. Anesthesiology.

1990;73:244-248.

10. Magorian T, Flannery KB, Miller RD. Comparison of rocuronium,

succinylcholine, and vecuronium for rapid-sequence induction of

anesthesia in adult patients. Anesthesiology. 1993;79:913-918.

11. McCourt KC, Salmela L, Mirakhur RK, et al. Comparison of

rocuronium and suxamethonium for use during rapid sequence

induction of anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 1998;53:867-871.

12. Mazurek AJ, Rae B, Hann S, et al. Rocuronium versus succinyl-

choline: are they equally effective during rapid-sequence induc-

tion of anesthesia? Anesth Analg. 1998;87:1259-1262.

13. Njoku DB, Lenox WC. Use care when injecting rocuronium and

thiopental for rapid sequence induction and tracheal intubation

[letter]. Anesthesiology. 1995;83:222.

14. Brandom BW. Use care when injecting rocuronium and thiopental

for rapid sequence induction and tracheal intubation [letter].

Anesthesiology. 1995;83:222.

15. Molbegott L. The precipitation of rocuronium in a needleless intra-

venous injection adaptor [letter]. Anesthesiology. 1995; 83:223.

16. Lawes EJ, Campbell I, Mercer D. Inflation pressure, gastric insuffla-

tion and rapid sequence induction. Br J Anaesth. 1987;59:315-318.

17. Vanner RG, Asai T. Safe use of cricoid pressure. Anesthesia. 1999;

54:1-3.

18. Putland J. Subconjunctival haemmorrhage following rapid

sequence induction in pregnancy [letter]. Anaesthesia. 1998;

53:313.

19. Heath KJ, Palmer M, Fletcher, SJ. Fracture of the cricoid cartilage

after Sellicks manoeuvre. Br J Anaesth. 1996;76:877-878.

AUTHORS

Stacey Schlesinger, CRNA, MSN, MBA, is a nurse anesthetist for Uni-

four Anesthesia Associates in Hickory, NC.

Diane Blanchfield, CRNA, MS, is a clinical coordinator at Carolinas

Health System in Charlotte, NC.

You might also like

- Critical Care Review: Airway Management of The Critically Ill PatientDocument16 pagesCritical Care Review: Airway Management of The Critically Ill PatientNikita ShakyaNo ratings yet

- Secuencia de Intubación RápidaDocument16 pagesSecuencia de Intubación Rápidaalis_maNo ratings yet

- Rapid Sequence Intubation and Cricoid PressureDocument16 pagesRapid Sequence Intubation and Cricoid PressureErlin IrawatiNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0733862722000384 MainDocument13 pages1 s2.0 S0733862722000384 Maincoca12451No ratings yet

- 4.-Rapid Sequence Intubation in Adults - Uptodate PDFDocument14 pages4.-Rapid Sequence Intubation in Adults - Uptodate PDFkendramura100% (1)

- Obesity and Anticipated Difficult Airway - A Comprehensive Approach With Videolaryngoscopy, Ramp Position, Sevoflurane and Opioid Free AnaesthesiaDocument8 pagesObesity and Anticipated Difficult Airway - A Comprehensive Approach With Videolaryngoscopy, Ramp Position, Sevoflurane and Opioid Free AnaesthesiaIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- 2022 Preoperative Assessment Premedication Perioperative DocumentationDocument38 pages2022 Preoperative Assessment Premedication Perioperative DocumentationMohmmed Mousa100% (1)

- AARC Clinical Practice GuidelineDocument7 pagesAARC Clinical Practice GuidelineXime GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Ventilatorweaningand Extubation: Karen E.A. Burns,, Bram Rochwerg, Andrew J.E. SeelyDocument18 pagesVentilatorweaningand Extubation: Karen E.A. Burns,, Bram Rochwerg, Andrew J.E. Seelyأركان هيلث Arkan healthNo ratings yet

- Essentials in Lung TransplantationFrom EverandEssentials in Lung TransplantationAllan R. GlanvilleNo ratings yet

- Smith 2001Document19 pagesSmith 2001PaulHerreraNo ratings yet

- Freid 2005Document14 pagesFreid 2005PaulHerreraNo ratings yet

- Airway Management in The Obese Patient: William A. LoderDocument6 pagesAirway Management in The Obese Patient: William A. LoderTapas Kumar SahooNo ratings yet

- Rapid Sequence Intubation For Adults Outside The Operating RoomDocument12 pagesRapid Sequence Intubation For Adults Outside The Operating Roomjohnsam93No ratings yet

- Evid TT 2200305Document4 pagesEvid TT 2200305Muthia Farah AshmaNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia in Prehospital Emergencies and in The Emergency DepartmentDocument7 pagesAnesthesia in Prehospital Emergencies and in The Emergency DepartmentIvan TapiaNo ratings yet

- Practice Guidelines For Preoperative FastingDocument18 pagesPractice Guidelines For Preoperative FastingTaufik RachmanNo ratings yet

- Physiotherapy in The ICUDocument10 pagesPhysiotherapy in The ICUakheel ahammedNo ratings yet

- Effect of Smoking On Intraoperative Sputum and Postoperative Pulmonary Complication in Minor Surgical PatientsDocument7 pagesEffect of Smoking On Intraoperative Sputum and Postoperative Pulmonary Complication in Minor Surgical PatientsfellaniellaNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Rapid Sequence Intubation - An In-Depth ReviewDocument12 pagesPediatric Rapid Sequence Intubation - An In-Depth ReviewDiego LatorreNo ratings yet

- Rapid Sequence Intubation in Adults For Emergency Medicine and Critical Care - UpToDateDocument41 pagesRapid Sequence Intubation in Adults For Emergency Medicine and Critical Care - UpToDateFabio FreitasNo ratings yet

- 2015 LeeuwenbergDocument10 pages2015 LeeuwenbergPaulHerreraNo ratings yet

- Maximizing Success With Rapid Sequence IntubationsDocument11 pagesMaximizing Success With Rapid Sequence IntubationsRaymond RosarioNo ratings yet

- Prehospital Rsi ManualDocument20 pagesPrehospital Rsi ManualMiguel XanaduNo ratings yet

- Articulo de Indice de SecrecionesDocument7 pagesArticulo de Indice de Secrecionesmariam.husseinjNo ratings yet

- The Physiologically Difficult Airway: Eview RticleDocument9 pagesThe Physiologically Difficult Airway: Eview RticleEdson Llerena SalvoNo ratings yet

- Farmacologia en SIRDocument19 pagesFarmacologia en SIRFranklin Correa PrietoNo ratings yet

- Greater Sydney Area Hems Prehospital Rsi Manual: Version 2.1 Oct 2012Document20 pagesGreater Sydney Area Hems Prehospital Rsi Manual: Version 2.1 Oct 2012Juan Antonio GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Enhancing Pulmonary Function and Arterial Blood GaDocument12 pagesEnhancing Pulmonary Function and Arterial Blood Gaاحمد العايديNo ratings yet

- Module 1 Case StudyDocument7 pagesModule 1 Case StudyDivine ParagasNo ratings yet

- Secuencia Rapida GuiasDocument29 pagesSecuencia Rapida GuiasToñoGomezNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia For Bariatric Surgery Practice Guideline - Approved 4 - 9 - 2018 - KAPC - PDF PDFDocument4 pagesAnesthesia For Bariatric Surgery Practice Guideline - Approved 4 - 9 - 2018 - KAPC - PDF PDFHIRANGERNo ratings yet

- Myasthenia Gravis Multiple Sclerosis Case FileDocument3 pagesMyasthenia Gravis Multiple Sclerosis Case Filehttps://medical-phd.blogspot.comNo ratings yet

- Atracurio Vs CisatracurioDocument6 pagesAtracurio Vs CisatracurioEdisonANo ratings yet

- Trends in Anasthesia and Critical CareDocument6 pagesTrends in Anasthesia and Critical CareNurLatifah Chairil AnwarNo ratings yet

- Acute Life-Threatening Hypoxemia During Mechanical VentilationDocument8 pagesAcute Life-Threatening Hypoxemia During Mechanical VentilationCesar Rivas CamposNo ratings yet

- Rapid Sequence Intubation: BackgroundDocument8 pagesRapid Sequence Intubation: Backgroundmarsh86No ratings yet

- RCT of Aprv Vs LPV in Ards PtsDocument11 pagesRCT of Aprv Vs LPV in Ards PtsOldriana Prawiro HapsariNo ratings yet

- Airway Covid - 19Document37 pagesAirway Covid - 19Monica Herdiati Rukmana NaibahoNo ratings yet

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America Office Based Anesthesia 45 57Document13 pagesOral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America Office Based Anesthesia 45 57Max FaxNo ratings yet

- Symposium Papers: Emergency Airway ManagementDocument10 pagesSymposium Papers: Emergency Airway Managementdewin21No ratings yet

- 37 Iajps37112017 PDFDocument4 pages37 Iajps37112017 PDFBaru Chandrasekhar RaoNo ratings yet

- Kali Bichromicum 30C For COPD 2005Document8 pagesKali Bichromicum 30C For COPD 2005Dr. Nancy MalikNo ratings yet

- Mechanical Ventilator Discontinuation Process: Lingye Chen,, Daniel Gilstrap,, Christopher E. CoxDocument7 pagesMechanical Ventilator Discontinuation Process: Lingye Chen,, Daniel Gilstrap,, Christopher E. CoxGhost11mNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Time-To-Weaning in A Specialized Respiratory Care UnitDocument10 pagesDeterminants of Time-To-Weaning in A Specialized Respiratory Care UnitClaudia IsabelNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Time-To-Weaning in A Specialized Respiratory Care UnitDocument10 pagesDeterminants of Time-To-Weaning in A Specialized Respiratory Care UnitClaudia IsabelNo ratings yet

- Comparative Study of Breathing Techniques After Coronary Artery by Pass GraftingDocument12 pagesComparative Study of Breathing Techniques After Coronary Artery by Pass GraftingJulenda CintarinovaNo ratings yet

- 2 DiaphragmaticExcursionDocument5 pages2 DiaphragmaticExcursionTiago XavierNo ratings yet

- Masoomeh Adib, Atefeh Ghanbari, Cyrus Emir Alavi and Ehsan Kazemnezhad LeyliDocument9 pagesMasoomeh Adib, Atefeh Ghanbari, Cyrus Emir Alavi and Ehsan Kazemnezhad LeyliBoy MadNo ratings yet

- Should Patients Be Able To Follow Commands Prior To IonDocument10 pagesShould Patients Be Able To Follow Commands Prior To IonjuliasimonassiNo ratings yet

- Extubation With or Without Spontaneous Breathing TrialDocument9 pagesExtubation With or Without Spontaneous Breathing TrialPAULA SORAIA CHENNo ratings yet

- Maggiore 2013Document10 pagesMaggiore 2013oman hendiNo ratings yet

- NCM 112 (FINALS) Chap 1Document2 pagesNCM 112 (FINALS) Chap 1MikasaNo ratings yet

- ERAS Protocols in TB EmpyemaDocument6 pagesERAS Protocols in TB EmpyemaMohan VenkateshNo ratings yet

- Ards Prone PositionDocument9 pagesArds Prone PositionAnonymous XHK6FgHUNo ratings yet

- Jerath2020 Article InhalationalVolatile-basedSedaDocument4 pagesJerath2020 Article InhalationalVolatile-basedSedasncr.gnyNo ratings yet

- Webinar Kuliah Umum Anestesi Joglo Semar 17 Juni 2020Document95 pagesWebinar Kuliah Umum Anestesi Joglo Semar 17 Juni 2020izaNo ratings yet

- Terapia Adjunta en SdraDocument23 pagesTerapia Adjunta en SdraMarcoNo ratings yet

- RSI - Children 2 PDFDocument6 pagesRSI - Children 2 PDFAbdul RachmanNo ratings yet

- Voisard Manufacturing, Inc. Advanced Product Quality Planning Check ListDocument1 pageVoisard Manufacturing, Inc. Advanced Product Quality Planning Check ListzaheermechNo ratings yet

- Total Quality Management Must Know" Concepts For EngineersDocument28 pagesTotal Quality Management Must Know" Concepts For EngineerszaheermechNo ratings yet

- Training Schedule PWIDocument1 pageTraining Schedule PWIzaheermechNo ratings yet

- Cswip 3.1 Welding Inspector - Multiple Choice Question, Dec 7, 2007Document43 pagesCswip 3.1 Welding Inspector - Multiple Choice Question, Dec 7, 2007claytoninf87% (30)

- CSWIP Plate Tr5. WPK Rev2Document4 pagesCSWIP Plate Tr5. WPK Rev2razormeback100% (1)

- Physical Configuration Audit (PCA) ChecklistDocument2 pagesPhysical Configuration Audit (PCA) ChecklistzaheermechNo ratings yet

- Preventive Maintenance of MachinesDocument6 pagesPreventive Maintenance of MachineszaheermechNo ratings yet

- ISO Standards Collection - CranesDocument4 pagesISO Standards Collection - CranesJosé Rezende0% (1)

- Functional Configuration Audit (FCA) Checklist: RequirementsDocument2 pagesFunctional Configuration Audit (FCA) Checklist: RequirementszaheermechNo ratings yet

- Passive and Low Frequency RadarDocument11 pagesPassive and Low Frequency RadarzaheermechNo ratings yet

- Pca Checklist: RestrictedDocument3 pagesPca Checklist: RestrictedzaheermechNo ratings yet

- FCA Checklist (NASA)Document2 pagesFCA Checklist (NASA)zaheermechNo ratings yet

- Guide To Insulation Product Specifications: ASTM Guides, Practices and Test MethodsDocument24 pagesGuide To Insulation Product Specifications: ASTM Guides, Practices and Test MethodszaheermechNo ratings yet

- A Powerpoint Training Presentation: by Keith H. CooperDocument38 pagesA Powerpoint Training Presentation: by Keith H. CooperzaheermechNo ratings yet

- ACCP Professional Level III Initial Qualification RequirementsDocument1 pageACCP Professional Level III Initial Qualification RequirementszaheermechNo ratings yet

- EXAMPLE CalculationsDocument4 pagesEXAMPLE CalculationszaheermechNo ratings yet

- Gant ChartDocument2 pagesGant ChartzaheermechNo ratings yet

- Denso HP4Document87 pagesDenso HP4Abraham Janco Janco100% (2)

- Thesis TopicsDocument9 pagesThesis TopicsInayath AliNo ratings yet

- dnd3 Character Sheet STD 105cDocument2 pagesdnd3 Character Sheet STD 105cGerry MaloneyNo ratings yet

- PRP RationaleDocument12 pagesPRP Rationalemarquezjayson548No ratings yet

- ReflectionDocument2 pagesReflectionBảo HàNo ratings yet

- A Crude Awakening Video NotesDocument3 pagesA Crude Awakening Video NotesTai NguyenNo ratings yet

- Individual Ability in SoftwareDocument9 pagesIndividual Ability in Softwaredhana0809100% (4)

- CREW Whitaker Recusal Letter DOJ 11-8-2018Document9 pagesCREW Whitaker Recusal Letter DOJ 11-8-2018Beverly TranNo ratings yet

- Airplus CDF3 Technical SpecsDocument38 pagesAirplus CDF3 Technical Specssadik FreelancerNo ratings yet

- Distortion of The Ecclesiological Views of Metropolitan Chrysostomos of PhlorinaDocument11 pagesDistortion of The Ecclesiological Views of Metropolitan Chrysostomos of PhlorinaHibernoSlavNo ratings yet

- Name: - Date: - Week/s: - 2 - Topic: Examining Trends and FadsDocument3 pagesName: - Date: - Week/s: - 2 - Topic: Examining Trends and FadsRojelyn Conturno100% (1)

- Kindergarten ArchitectureDocument65 pagesKindergarten ArchitectureAnushka Khatri83% (6)

- Report End of Chapter 1Document4 pagesReport End of Chapter 1Amellia MaizanNo ratings yet

- Proofreading: Basic Guide (Research)Document34 pagesProofreading: Basic Guide (Research)Mary Christelle100% (1)

- Biologic and Biophysical Technologies. FINALDocument28 pagesBiologic and Biophysical Technologies. FINALRafael Miguel MallillinNo ratings yet

- SwahiliDocument7 pagesSwahiliMohammedNo ratings yet

- Content Kartilya NG Katipunan: Kataastaasan, Kagalanggalangang Katipunan NG Mga Anak NG Bayan)Document6 pagesContent Kartilya NG Katipunan: Kataastaasan, Kagalanggalangang Katipunan NG Mga Anak NG Bayan)AngelaNo ratings yet

- CPP CheatsheetDocument10 pagesCPP CheatsheetPrakash GavelNo ratings yet

- RagragsakanDocument6 pagesRagragsakanRazel Hijastro86% (7)

- Implementasi Fault Management (Manajemen Kesalahan) Pada Network Management System (NMS) Berbasis SNMPDocument11 pagesImplementasi Fault Management (Manajemen Kesalahan) Pada Network Management System (NMS) Berbasis SNMPIwoncl AsranNo ratings yet

- Natural Gas DistributionDocument46 pagesNatural Gas DistributionscribdmisraNo ratings yet

- The Spokesman Weekly Vol. 32 No. 39 May 30, 1983Document12 pagesThe Spokesman Weekly Vol. 32 No. 39 May 30, 1983SikhDigitalLibraryNo ratings yet

- Small Incision Cataract SurgeryDocument249 pagesSmall Incision Cataract SurgeryAillen YovitaNo ratings yet

- My Kindergarten BookDocument48 pagesMy Kindergarten BookfranciscoNo ratings yet

- Detergent For Auto DishWashing Machine EDocument5 pagesDetergent For Auto DishWashing Machine EkaltoumNo ratings yet

- Pale ExamDocument4 pagesPale ExamPatrick Tan100% (1)

- Material Safety Data Sheet: Manufacturer Pt. Bital AsiaDocument3 pagesMaterial Safety Data Sheet: Manufacturer Pt. Bital AsiaediNo ratings yet

- E9d30c8 4837smartDocument1 pageE9d30c8 4837smartSantoshNo ratings yet

- Exercise No. 2 (DCC First and Second Summary)Document3 pagesExercise No. 2 (DCC First and Second Summary)Lalin-Mema LRNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesLiterature Reviewapi-353923446No ratings yet