Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Abstract Unmusical Man

Abstract Unmusical Man

Uploaded by

Irina GCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Abstract Unmusical Man

Abstract Unmusical Man

Uploaded by

Irina GCopyright:

Available Formats

The Ape Clothed in Gold.

The

unmusical man and his broken

music

In this paper I want to look at the early modern figure of unmusical man

and at instances of broken inner music as a way of addressing both the

figurative usage of music as an encompassing metaphor of harmony and

proportion and the account of its real effects in a persons moral and intellectual

life, in several types of text: writings in praise of music (The Praise of Musicke:

1586; John Cases Apologia Musices: 1588; Gioseffo Zarlinos Istitutioni

Harmoniche: 1558), general manuals on music (Thomas Morleys A Plaine and

Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke: 1597; Charles Butlers The Principles of

Musik: 1634; John Playfords Introduction to the Skill of Musick: 1655; Thomas

Ravenscrofts Treatise of Practicall Musicke: 1605 and A Briefe Discourse: 1614),

some of Shakespeares plays (mainly The Tempest, approx. 1610-11; Richard II,

approx. 1595; The Merchant of Venice, 1596-1598) and Peachams tratise on

gentlemanly education (The Compleat Gentleman: 1622). Since the uncultivated

nature of the man that hath no music in himself (Shakespeare, MV, 5.1.82) is

not only a matter of uncouth manners or lack of proper skills, more philosophical

questions related to moral decorum, the cultivation of ones being and the proper

balance between Art and Nature in ones life will be addressed. To this end, I will

be using texts in which human mentation is described by analogy with musics

inner mechanisms (cf. Kassler, 1995) alongside writings that comment on the

(right) use of music in altering ones inner tuning: Thomas Wright, The Passions

of the Minde in Generall: 1604; Descartess Musicae Compendium: 1653 and

the Passions of the Soul: 1649; Burtons Anatomy of Melancholy: 1621; Robert

Fludds De musica mundana: 1618 and Utriusque Cosmi , 1617-1624.

You might also like

- RP Year 1 Semester 2Document234 pagesRP Year 1 Semester 2keith90% (10)

- The Lightworker's HandbookDocument58 pagesThe Lightworker's HandbookEvgeniq Marcenkova100% (9)

- Louis Horst - Pre-Classic Dance Forms (1987) PDFDocument153 pagesLouis Horst - Pre-Classic Dance Forms (1987) PDFMartina Buquet Ibarra100% (1)

- A Maze Ing Layers of EarthDocument2 pagesA Maze Ing Layers of EarthMajessa Mae Bongue0% (1)

- Case Control StudyDocument6 pagesCase Control StudyAndre ChundawanNo ratings yet

- Mastery of Sorrow and Melancholy Lute News QDocument23 pagesMastery of Sorrow and Melancholy Lute News QLevi SheptovitskyNo ratings yet

- MonteverdiDocument10 pagesMonteverdiNikolina ArapovićNo ratings yet

- Speaking Music PDFDocument18 pagesSpeaking Music PDFPaula AbdulaNo ratings yet

- Steege 2012 History of Music Theory From Rameau To Riemann (Literatuurlijst)Document2 pagesSteege 2012 History of Music Theory From Rameau To Riemann (Literatuurlijst)MarkvN2No ratings yet

- Galant MusicDocument4 pagesGalant MusicDiana GhiusNo ratings yet

- Oral Exam - General GuideDocument7 pagesOral Exam - General GuideGabrielNo ratings yet

- Wikipedia. Doctrine of Affections (Affektenlehre) Traducido Del AlemanDocument3 pagesWikipedia. Doctrine of Affections (Affektenlehre) Traducido Del Alemansercast99No ratings yet

- Ossi BaroqueDocument266 pagesOssi Baroquechristian yokosawaNo ratings yet

- The Sonata For Guitar in 1920-1950 Period - Ph. D. Thesis Resume by Costin SoareDocument12 pagesThe Sonata For Guitar in 1920-1950 Period - Ph. D. Thesis Resume by Costin Soarecostin_soare_2100% (4)

- The Florentine Camerata and The Restoration of Musical AesDocument8 pagesThe Florentine Camerata and The Restoration of Musical Aesalxberry100% (1)

- Music of The Medieval Period (700-1400)Document6 pagesMusic of The Medieval Period (700-1400)Reijel AgubNo ratings yet

- Music 9 1 Quarter MUSIC OF THE MEDIEVAL (700-1400), RENAISSANCE (1400-1600), AND BAROQUE (1685-1750) PERIODSDocument7 pagesMusic 9 1 Quarter MUSIC OF THE MEDIEVAL (700-1400), RENAISSANCE (1400-1600), AND BAROQUE (1685-1750) PERIODSKaren Jamito MadridejosNo ratings yet

- 1Document3 pages1phamngocthao01072000No ratings yet

- Music History Study GuideDocument5 pagesMusic History Study GuideManuel Figueroa100% (1)

- Mine Doğantan Dack Journal of The Royal Musical Association Volume 142 Issue 2 2017 (Doi 10.1080/02690403.2017.1361208) Doğantan-Dack, Mine - Once Again - Page and StageDocument17 pagesMine Doğantan Dack Journal of The Royal Musical Association Volume 142 Issue 2 2017 (Doi 10.1080/02690403.2017.1361208) Doğantan-Dack, Mine - Once Again - Page and StageValentina DaldeganNo ratings yet

- History of MusicDocument22 pagesHistory of MusicMytha Isabel SalesNo ratings yet

- Mers EnneDocument25 pagesMers EnneVerónica CastelaNo ratings yet

- Wikipedia. Doctrine of The Figures (Figurenlehre) Traducido Del AlemanDocument12 pagesWikipedia. Doctrine of The Figures (Figurenlehre) Traducido Del Alemansercast99No ratings yet

- EVAN BONDS, MARK - Idealism and The Aesthetics of Insrumental Music at The Turn of The CON PDFDocument32 pagesEVAN BONDS, MARK - Idealism and The Aesthetics of Insrumental Music at The Turn of The CON PDFMonsieur PichonNo ratings yet

- tmp6849 TMPDocument31 pagestmp6849 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Full Ebook of Pakistans Foreign Policy 1947 2019 Abdul Sattar Online PDF All ChapterDocument24 pagesFull Ebook of Pakistans Foreign Policy 1947 2019 Abdul Sattar Online PDF All Chapterveronicakenney249074100% (3)

- Quantz EssayDocument4 pagesQuantz EssayMarcio CursinoNo ratings yet

- Repetition in MusicDocument6 pagesRepetition in Musicrrrrrr7575100% (1)

- Western Classic Music From 1600Document1 pageWestern Classic Music From 1600Rinaz MalaNo ratings yet

- Pre-Classic Dance FormsDocument20 pagesPre-Classic Dance FormsBruno0% (2)

- Mozart & His Masonic MusicDocument4 pagesMozart & His Masonic MusicJulio GuillénNo ratings yet

- RomanticismDocument77 pagesRomanticismAiza Casero Leaño100% (3)

- BaroqueDocument2 pagesBaroqueEnrico FaiellaNo ratings yet

- History 2023Document16 pagesHistory 2023BlakeNo ratings yet

- AbbatiniDocument5 pagesAbbatiniPaulaRiveroNo ratings yet

- The History of Classical Music For BeginnersFrom EverandThe History of Classical Music For BeginnersRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Structure in Western ClassicalDocument9 pagesStructure in Western Classicalchidi_orji_3No ratings yet

- Mersenne Paper BavingtonDocument23 pagesMersenne Paper BavingtonJosé RNo ratings yet

- Henry PurcellDocument11 pagesHenry Purcellapi-285245536No ratings yet

- Baroque Study GuideDocument6 pagesBaroque Study GuideSergio BarzaNo ratings yet

- Puritan PoetryDocument4 pagesPuritan PoetryFakhar FarooqNo ratings yet

- Musicofthemedieval PeriodDocument30 pagesMusicofthemedieval PeriodHannah Faye Ambon- NavarroNo ratings yet

- 9 Q1 Reviewer MAPEHDocument12 pages9 Q1 Reviewer MAPEHMa Belle Jasmine DelfinNo ratings yet

- Music 9 Lesson '1Document55 pagesMusic 9 Lesson '1Arthur LaurelNo ratings yet

- MODULE 4 GRADE 9 Final 1Document16 pagesMODULE 4 GRADE 9 Final 1CHERRY LYN BELGIRANo ratings yet

- Romantic MusicDocument7 pagesRomantic MusicDiana GhiusNo ratings yet

- History of Western Classical Music I Contributions of Philosophers or Theorists To The Historical Development of MusicDocument6 pagesHistory of Western Classical Music I Contributions of Philosophers or Theorists To The Historical Development of MusicAlhajiNo ratings yet

- WHMDocument31 pagesWHMJeulo D. MadriagaNo ratings yet

- Final Exam, English IVDocument2 pagesFinal Exam, English IVSteph PerezNo ratings yet

- Craig H. Russell "Manuel de Sumaya: Reexamining The A Cappella Choral Music of A Mexican Master"Document16 pagesCraig H. Russell "Manuel de Sumaya: Reexamining The A Cappella Choral Music of A Mexican Master"Angelica CrescencioNo ratings yet

- Review Sheet - Week 15 (2014)Document1 pageReview Sheet - Week 15 (2014)Eric JatonNo ratings yet

- Introducing The Music of The Classical PeriodDocument29 pagesIntroducing The Music of The Classical Period789No ratings yet

- MAPEHDocument41 pagesMAPEHLance DaoalaNo ratings yet

- Art Appreciation Elements of MusicDocument3 pagesArt Appreciation Elements of MusicDesiree Thea Tapar100% (2)

- Sensuous Music AestheticsDocument35 pagesSensuous Music AestheticsH mousaviNo ratings yet

- Baroque EraDocument1 pageBaroque EraCarol CrawfordNo ratings yet

- Locke Aida and Nine Readings of EmpireDocument28 pagesLocke Aida and Nine Readings of EmpireDolhathai IntawongNo ratings yet

- MAPEH 9-Music Day 1Document18 pagesMAPEH 9-Music Day 1Elisha OpesNo ratings yet

- WefawefDocument1 pageWefawefaefacweuhfcwuehcNo ratings yet

- The Music of The Medieval Renaissance and Baroque Grade 9 1st QuarterDocument40 pagesThe Music of The Medieval Renaissance and Baroque Grade 9 1st QuarterEduard PanganNo ratings yet

- Mad Scenes in OperaDocument4 pagesMad Scenes in Operabbyu96No ratings yet

- Decadent Enchantments: The Revival of Gregorian Chant at SolesmesFrom EverandDecadent Enchantments: The Revival of Gregorian Chant at SolesmesNo ratings yet

- Questions ExplanationDocument63 pagesQuestions ExplanationnomintmNo ratings yet

- Near Field Communication Based College CanteenDocument5 pagesNear Field Communication Based College CanteenJunaid M FaisalNo ratings yet

- Mobile COMPUTINGDocument169 pagesMobile COMPUTINGNPMYS23No ratings yet

- New Microsoft Office Word DocumentDocument9 pagesNew Microsoft Office Word DocumentGaurav JaiswalNo ratings yet

- 1.smart Light, Temperature, Air Condition ControlDocument4 pages1.smart Light, Temperature, Air Condition ControlFatin Nur Syahirah AzharNo ratings yet

- IMAGINEDocument48 pagesIMAGINEGilherme HenriqueNo ratings yet

- Phontech Ics 6200Document193 pagesPhontech Ics 6200danh voNo ratings yet

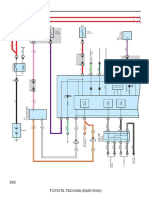

- Combination Meter: 262 Toyota Tacoma (Em01D0U)Document6 pagesCombination Meter: 262 Toyota Tacoma (Em01D0U)hamayunNo ratings yet

- Nuccore ResultDocument2,189 pagesNuccore ResultJohanS.Acebedo0% (1)

- The Downward Spiral - RiveraDocument4 pagesThe Downward Spiral - RiveraAnthony AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Module 4 - Lateral Force Procedure-Design Base ShearDocument6 pagesModule 4 - Lateral Force Procedure-Design Base ShearClarize MikaNo ratings yet

- Science 7 DLP q3w9d4 & w10d1Document4 pagesScience 7 DLP q3w9d4 & w10d1Tammy SelaromNo ratings yet

- GMORS Rubber Especification O Rings Guidebook AS568ADocument90 pagesGMORS Rubber Especification O Rings Guidebook AS568AfeltofsnakeNo ratings yet

- Ef 2000 TestingDocument12 pagesEf 2000 TestingLeiser HartbeckNo ratings yet

- Shop Policies and ProceduresDocument1 pageShop Policies and ProcedureseaeastepNo ratings yet

- 145kV GTP BPDBDocument4 pages145kV GTP BPDBJRC TestingNo ratings yet

- Posi BraceDocument2 pagesPosi BraceBenNo ratings yet

- Risk Assessment: Construction Plan For Box Girder Joints, Wing Plates and Anti-Collision GuardrailsDocument3 pagesRisk Assessment: Construction Plan For Box Girder Joints, Wing Plates and Anti-Collision Guardrailssalauddin0mohammedNo ratings yet

- Chemistry Revision NotesDocument7 pagesChemistry Revision NotesFarhan RahmanNo ratings yet

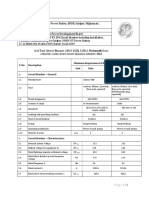

- Analysis of Rates (Nh-15 Barmer - Sanchor)Document118 pagesAnalysis of Rates (Nh-15 Barmer - Sanchor)rahulchauhan7869No ratings yet

- School of Natural Sciences Status Report Details School of Natural Sciences Intern's ReportDocument7 pagesSchool of Natural Sciences Status Report Details School of Natural Sciences Intern's ReportAgyao Yam FaithNo ratings yet

- Read The Text Carefully and Then Answer The Questions That Follow! Floods Force Thousands of People To Evacuate in GorontaloDocument2 pagesRead The Text Carefully and Then Answer The Questions That Follow! Floods Force Thousands of People To Evacuate in GorontaloDella SagitaNo ratings yet

- Product Guide: FeaturesDocument24 pagesProduct Guide: FeaturesWesleyNo ratings yet

- JournalDocument7 pagesJournalIman KhairuddinNo ratings yet

- Benfits of Review BWDocument10 pagesBenfits of Review BWbrianNo ratings yet

- TTSL CatalogDocument3 pagesTTSL CatalogNguyen CuongNo ratings yet