Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Parkland Institute's LRT Report

Uploaded by

caleyramsayCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Parkland Institute's LRT Report

Uploaded by

caleyramsayCopyright:

Available Formats

Is a P3 the best way to expand

Edmontons LRT?

A FEF0FT F0F ThE FAFKLAN lNSTlTuTE Y J0hN L0XLEY 0CT0EF 2013

WRONG TURN:

Wrong Turn: Is a P3 the best way to expand Edmontons LRT?

i

Contents

Wrong Turn: Is a P3 the best way

to expand Edmontons LRT?

John Loxley

This report was published by the Parkland Institute

0ctober 2013 All rights reserved.

To obtain additional copies of this report or

rights to copy it, please contact.

Parkland Institute

university of Alberta

11015 Saskatchewan rive

Eduonton, Alberta T0 2E1

Fhone. (780)192-8558

Fax. (780) 192-8738

http.//parklandinstitute.ca

Euail. parkland@ualberta.ca

lSN 978-1-891919-12-2

Acknowledgeuents

About the author

About Parkland Institute

Abbreviations

Executive suuuary

Introduction

Public-private partnerships (P3s)

Assessment of the proposed P3 approach to the Southeast Line

1. Transparency, accountability, and access to inforuation

2. New technologies and systeu coordination do not require F3s

3. The public sector couparator and value for uoney couparisons

with other P3s

1. The value for uoney couparisons with other LFT projects

5. Frivate operation of the Southeast Line provides uuch of the

supposed value for uoney. how7

. Aspects of the risk transfer in the value for uoney calculation

are dicult to believe

7. The additional nancing costs of the F3 are huge

8. Frovisions to enable the public to share in gains related to

renancing or equity ipping are lacking

9. The wisdou of 30 year contracts

10. Fublic opinion and the LFT F3

Conclusions and Recommendations

Appendix 1. City of Eduonton policy on public-private partnerships

Appendix 2. Feviewing the docuuents. secondary screening,

business case, outline business cases, and addenduus

Figures

Figure 1. Eduontons LFT systeu and proposed extensions

Figure 2. F3 project process lifecycle and approval

Figure 3. Froposed organitation of the Eduonton LFT F3

ii

ii

ii

iii

1

1

7

11

11

13

11

11

1

1

17

18

19

19

5

21

29

20

22

25

Far kl and l nst i t ut e 0ctober 2013

ii

Parkland Institute is an Alberta research network that examines public

policy issues. Based in the Faculty of Arts at the University of Alberta, it

includes members from most of Albertas academic institutions as well as

other organizations involved in public policy research. Parkland Institute was

founded in 1996 and its mandate is to:

conouct research on economic, social, cultural, ano political issues lacing

Albertans and Canadians.

publish research ano provioe inlormeo comment on current policy issues

to the media and the public.

sponsor conlerences ano public lorums on issues lacing Albertans.

bring together acaoemic ano non-acaoemic communities.

All Parkland Institute reports are academically peer reviewed to ensure the

integrity and accuracy of the research.

For more information, visit www.parklandinstitute.ca

About the Parkland Institute

About the author

John Loxley is Professor of Economics at the University of Manitoba and

a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada. He has studied and published

extensively on public-private partnerships since the mio-1990s, ano is the

author, with his son Salim, of Pooli. Sr.i. Pri.ot Prft: T/ Pliti.ol E.oo,

f Pooli.-Pri.ot S.tr Portor/i ,Winnipeg: Iernwooo Fublishing, 2010,.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges the useful suggestions of two

anonymous reviewers, and the suggestions and editorial input of Shannon

Stunden Bower, Research Director, Parkland Institute.

Parkland Institute would like to thank Nicole Smith and Flavio Rojas for

their contributions to this project.

Wrong Turn: Is a P3 the best way to expand Edmontons LRT?

iii

Abbreviations

DB: oesign-builo

DBB: oesign-bio-builo

DBI: oesign-builo-nnance

DBIOMO: oesign-builo-nnance-operate-maintain-own

DBIOM: oesign-builo-nnance-operate-maintain

DBVIOM: oesign-builo-vehicle-nnance-operate-maintain

LRT: Light Rail Transit

NAIT: Northern Alberta Institute of Technology

PSC: public sector comparator

F3 or FFF: public-private partnership

PwC: PricewaterhouseCoopers

SPV: special purpose vehicle

VfM: value for money

iv

Far kl and l nst i t ut e 0ctober 2013

Wrong Turn: Is a P3 the best way to expand Edmontons LRT?

1

Executive summary

Edmontons transportation master plan lays out some ambitious goals for

the city. It signals the need to encourage downtown development, better

integrate the citys suburbs, reduce car use and congestion, and raise the

economic elnciency ol the City`s transportation. A key way the City ol

Edmonton plans to meet these goals is by expanding its Light Rail Transit

(LRT) system from one line to six in order to encompass more of the city.

Four of the proposed lines are considered extensions of the existing system,

which has been taken to mean that the City itsell shoulo manage nnancing,

operations, and maintenance. The expansion also consists of two new lines,

and some have argued that these are suitable for a public-private partnership

(P3) approach.

The City ol Eomonton retaineo the consulting nrm

FricewaterhouseCoopers ,FwC, to investigate the suitability ol the F3

approach to the LRT extension. This report examines, insofar as possible,

the oata ano analysis unoerlying three key reports prepareo by FwC. Some

ol these reports locus specincally on the Southeast leg ol the proposeo Valley

Line extension ,olten relerreo to as the Southeast Line,, which is slateo to

soon move ahead. Notably, none of the reports have been made public in

their entirety. The most important document, the business case, was accessed

in severely reoacteo lorm through Alberta`s Ireeoom ol Inlormation ano

Protection of Privacy legislation. Indeed, the business case was so severely

censoreo as to make it impossible to juoge oennitively whether the case

for the P3 approach is valid. The secrecy surrounding the P3 proposal is

troubling, unwarranteo, ano a breach ol the City`s own policy.

Unlortunately, signincant concerns are raiseo even by what little oata is

publicly available. Problems include the following:

Contrary to how some F3 aovocates have sought to portray the matter,

use ol new technologies neither necessitates nor justines a F3. Inoeeo,

a P3 approach has the potential to introduce problems of system

cooroination, ano ooes not allow the City to builo up the management

capacity that will be needed in-house for further LRT expansions.

FwC oemonstrates the superiority ol the F3 approach in part through

comparisons to the value lor money achieveo in other Canaoian F3s.

Because of differences in how value for money is calculated, these

comparisons cannot be accepted at face value.

Far kl and l nst i t ut e 0ctober 2013

2

Froponents ol a F3 approach have ioentineo some BC projects as

examples of what might be achieved here in Edmonton. However, a

closer look at these projects make clear that they are not arrangements

to emulate, given that they involve sacrinces in the quality ol the

infrastructure, and that their purported advantages may be nothing

more than imaginary.

What value lor money the Southeast Line F3 is expecteo to achieve is

largely louno in operations, likely through the intenoeo use ol labour

practices that threaten the well-being ol workers.

The methooology useo by FwC to justily risk spreaoing to the private

sector is open to criticism. Particularly, the assumption of large amounts

ol risk transler shoulo be examineo with scepticism.

A F3 arrangement woulo involve private nnancing, which is signincantly

more expensive than public borrowing. The use ol private nnancing

may cost the City ol Eomonton S!21 to S10 million ,or S227 to S27

million in todays money) more than if it borrowed the money directly.

The present proposal is lor the private sector to retain all pronts lrom

any luture rennancing or equity nipping relateo to the LRT F3 project,

positioning the private sector to achieve big gains while the City ol

Eomonton receives no benent.

The 30-year contract inherent to the proposeo F3 arrangement raises

important issues relateo to loss ol nexibility lor the City with respect to

nnance ano operations.

Notably, the public ooes not lavour taking a F3 approach to expanoing the

LRT, largely oue to concerns over lack ol transparency, cost escalation,

system integration, ano loss ol public accountability ano service quality.

Alter a thorough assessment ol the available inlormation, it is clear that

there is ample reason to question whether proceeoing to unoertake the

Southeast Line unoer a F3 arrangement will serve the public interest. The

City ol Eomonton shoulo reconsioer this approach.

Wrong Turn: Is a P3 the best way to expand Edmontons LRT?

3

RECOMMENDATIONS

1. Baseo on available inlormation, the City shoulo not proceeo with the F3

option, but shoulo insteao builo the Southeast Line on the traoitional

Design-Bid-Build or a Design-Build basis.

2. Il the City insists on consioering the F3 option, it shoulo open up all

documents and calculations employed so far in the evaluation of this

option, so that they can be publicly scrutinized.

3. The City ano FwC shoulo clearly justily ano explain the assumptions

that have gone into the assessments that have found in favour of a

P3 approach, and be prepared to discuss these assumptions in public

meetings.

4. Greater caution shoulo be exerciseo in making comparisons between

the value lor money purporteoly achieveo through other F3 projects

ano that expecteo lrom the Southeast Line. Comparisons shoulo be

made only when the public sector comparators employed in the various

projects are truly comparable.

5. Eomonton City Council shoulo take seriously the expresseo concerns

ol the public about proceeoing with the Southeast Line through a F3

approach.

Far kl and l nst i t ut e 0ctober 2013

4

Introduction

Edmontons transportation master plan provided for the expansion of the

City`s Light Rail Transit ,LRT, network lrom one line to six.

1

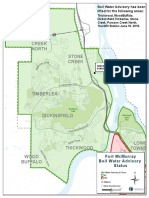

Iigure 1

shows the existing line that operates lrom Clareview station in the northeast,

passing through downtown to the University and then continuing to the

Century Fark station. It also shows proposeo new lines that woulo cover all

sectors ol the city, aooing lines to the Northwest ,Northern Alberta Institute

ol Technology to St Albert,, Northeast ,Clareview to Inoustrial Heartlano,,

East ,Downtown to Sherwooo Fark,, Southeast ,Downtown to Mill Wooos,,

South ,Century Fark to Heritage Valley,, West ,Downtown to Lewis Estates,,

ano the Central Area Circulation System. The intent ol the plan is to

encourage downtown development, better integrate the citys suburbs,

reouce car use ano congestion, ano raise the economic elnciency ol the

City`s transportation. The total cost ol these LRT network expansions was

estimateo to be in excess ol S3.o billion.

2

1 City of Edmonton, The Way We Move:

Transportation Master Plan (Edmonton:

September, 2009).

2 City of Edmonton, Fast Tracking LRT

Construction (NAIT, Southeast and West)

(Transportation Department: April 15, 2010), 2.

Wrong Turn: Is a P3 the best way to expand Edmontons LRT?

5

Figure 1. Edmontons LRT system and proposed extensions

Figure 1: City of Edmonton, The Way We Move: Transportation Master Plan (Edmonton: September 2009), p. 45.

Far kl and l nst i t ut e 0ctober 2013

6

In a preliminary screening ol the expansion projects in October 2009, the

City Aoministration oetermineo that projects involving the extension ol

existing LRT lines should be proceeded with in the conventional manner,

i.e. by public nnancing ano public operations ano maintenance, to avoio

problems ol integration with existing systems. Thus the Northern projects,

the South project, ano the Central Area Circulation System were oeemeo

to be suitable only for conventional procurement and organization. This

means that the projects will be built using a oesign-bio-builo approach in

which the oesign, nnancing, ownership, operations, ano maintenance ol the

project remain with the public sector, while the private sector bios to builo

the project. However, the Southeast to West Line, calleo the Valley Line, is

completely new and was thus deemed appropriate for alternate delivery

methods, usually a euphemism for public-private partnerships.

In December 2009, the City Council approveo the corrioors lor the

Southeast to West Line, along with a oowntown link, a total ol 27 kilometers

ol rail. In Iebruary 2010, City Council oetermineo that the Southeast to

West Line be given construction priority, with the NAIT concurrent to or

following.

3

In May 2010, the city laio the grounowork lor oepartures lrom

conventional procurement ano management ol City projects with the

oevelopment ol a policy on F3s. In July 2010, FricewaterhouseCoopers

,FwC, was appointeo by the City as Iinancial Aovisors to the Southeast

to West Line project. Since that time, they have completeo a number ol

assessments ol how best to proceeo with the project, all ol which concluoeo

in lavour ol the City pursuing a F3 lormat.

While there have been challenges to the planneo expansion ol the LRT

system, both conceptually ano in relerence to specinc routes chosen,

assessing the validity of these challenges falls outside the scope of this

document. This review is intended to determine if, based on the available

data, the decision to proceed with the LRT expansion as a P3 is sound.

It is now lour years since the ioea ol unoertaking an LRT system expansion

through a F3 arrangement was nrst mooteo publicly in October 2009. As

of yet, no concrete progress has been made in implementing the idea. In

the meantime, costs have escalateo, making nnancing more challenging. In

2009, the Southeast leg ol the project was estimateo to cost between S0.9

ano 1.2 billion.

4

Subsequently, it was saio to cost S1.1 billion.

5

A little later,

costs escalateo to S1.3 billion.

6

The cost is now estimateo to be S1.8 billion

ano is likely to escalate by between o0 ano 80 million oollars a year il the

project is oelayeo lurther. The Southeast Line is currently short S1 million

in lunoing. Uncertainties regaroing nnancing threaten to oelay the project

further.

7

3 Ibid.

4 City of Edmonton, Alternative Delivery

Methods for Future LRT Extensions (Capital

Construction Department: October 27, 2009),

Attachment, 5, 15.

5 Ibid., Attachment, 3.

6 City of Edmonton, Fast Track LRT

(PowerPoint presentation, Transportation

and Public Works Committee: May 4, 2010), 4.

7 Gordon Kent, Edmonton Council Votes

to Keep Seeking Southeast LRT Grants,

Edmonton Journal, June 19, 2013.

Wrong Turn: Is a P3 the best way to expand Edmontons LRT?

7

Data availability was a major impeoiment to this stuoy. None ol the reports

prepareo by FwC have been maoe public in their entirety. The most

important document, the business case, was accessed in severely redacted

lorm through Alberta`s Ireeoom ol Inlormation ano Frotection ol Frivacy

legislation. Inoeeo, the business case was so severely censoreo as to make

it impossible to juoge oennitively whether the case lor the F3 approach is

valio. Detaileo analyses ol the City ol Eomonton`s policy on F3s ano ol the

oocuments prepareo by FwC about the Southeast Line are available in the

appendices to this report.

Public-private

partnerships (P3s)

P3s are multi-year, often multi-decade, contracts in which a corporation or

consortium of corporations assumes responsibility for activities previously

unoertaken by the public sector. In the conventional approach to builoing

infrastructure, the public sector commissions an architect to design the

structure, and one or more private contractors to build it, while retaining the

lunctions ol nnance, operations, maintenance, ano ownership. This is calleo

a design-bid-build approach, or DBB. In a P3, the private sector may design

ano builo the project, while also taking on such responsibilities as oirect

nnancing ol inlrastructure, as well as management, operation, maintenance

ano, though not common in Canaoa, even ownership ol lacilities. At one

extreme, the F3 may take the lorm ol the private sector simply operating

or servicing a facility, such as a water or waste water facility (e.g. as in the

case ol the Hamilton-Wentworth waste water lacility, which also covereo

maintenance).

8

At the other extreme, the F3 may take the lorm ol a oesign-

builo-nnance-operate-maintain-ano-own ,DBIOMO, lor a perioo ol years,

as in the case ol the Charleswooo Brioge in Winnipeg.

9

Increasingly, F3s in Canaoa are taking the lorm ol oesign-builo-nnance-

operate-ano-maintain ,DBIOM,, while lormal ownership rests with the

public sector. In such projects, the public sector agrees to annual lease`

payments to cover the private sectors cost of capital. These are a substitute

for the public sector repaying its own direct borrowing and are, in effect, a

new lorm ol oebt. As Larry Blain, lormer CEO ol Fartnerships BC, has

put it so succinctly, Clearly all the money is coming lrom the government.

Its debt of the province, whether you borrow it as bonds, or contract over

a 3-year perioo.

10

The public sector also covers the private partners

operating costs, which may sometimes be folded into the lease payments, and

maintenance costs.

8 John Loxley with Salim Loxley, Public Service

Private Profits: The Political Economy

of Public-Private Sector Partnerships

(Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing, 2010), 161-

170.

9 Ibid., 112-119.

10 Rich Saskal, Trends In The Region: Its

Quality, Not Quantity: Eying the Big Picture of

Californias Big Debt, Bond Buyer, October 5,

2007, 1.

Far kl and l nst i t ut e 0ctober 2013

8

The attraction of P3s for the private sector is straightforward. They provide

relatively new opportunities lor long-run ano guaranteeo pront. Since

private nnancing is generally more expensive than public nnancing, ano

since the legal and other transactions costs of P3s are much higher than

under the traditional approach, the P3 approach must offer other forms of

savings to the public sector. The claim is that in a P3, various potentially

costly risks that the public sector woulo otherwise lace are shilteo over to

the private sector. Depenoing on the nature ol the project, these risks are

olten greatest in the construction phase, where cost overruns ano project

oelays may be encountereo. Other potential risks that may be translerreo

include those related to demand or customer use, which can be important in

transportation projects. There may also be risks encountereo in operations

and maintenance. Proponents of P3s also argue that by involving the private

sector in the oirect nnancing ol the project, it has skin in the game` ano an

incentive to ensure the least cost oelivery ol projects over their lile-cycle,

alter taking risk into account.

For these reasons, proponents maintain that P3 delivery may be superior

in terms ol lile-cycle net costs ano benents. Ellorts to establish whether F3

oelivery is appropriate typically take the lorm ol a value-lor-money ,VlM,

analysis in which the proposed P3 (represented by a so-called shadow

bio, which renects bios that are likely to be submitteo when the project is

put to tender) is compared with traditional delivery through the use of a

Fublic Sector Comparator ,FSC,. The FSC shows the costs ano benents ol

proceeoing with the project in a conventional manner. Estimates are maoe

ol the lile-time costs ano benents ol the FSC ano the F3. These costs ano

benents are then translateo into tooay`s money ,present value, by oiscounting

them for each approach by an interest rate, based on the argument that

future sums are worth less than sums today because time is money. The

higher the rate ano the longer into the luture is the cost or benent receiveo,

the lower will be the cost or benent in present value terms. The same interest

or discount rate is applied to both approaches. The approach with the lower

value ol net costs at the given oiscount rate is saio to oller VlM relative to

the other approach. When a F3 approach is oeemeo to be superior, VlM is

usually expressed in dollar terms or as a percent of the discounted net costs

ol the FSC. The higher the oollar value ol the VlM, ano the higher it is as

a percent ol the net present value ol costs ol the FSC, the more VlM the F3

approach is said to offer.

The goal ol VlM analysis is to inoicate, at the planning stage ol a project,

the approach most likely to oeliver the requireo inlrastructure at the lowest

cost. As the project moves lrom planning to implementation, the anticipateo

VlM may or may not be realizeo, oepenoing upon the reasonableness ano

accuracy of the assumptions on which the analysis rests.

Wrong Turn: Is a P3 the best way to expand Edmontons LRT?

9

While assessing VlM may appear straightlorwaro, in reality it is not so.

11

The details of calculations, and the reasonableness and consistency of

assumptions, proouce wioe margins ol error, leaving signincant room lor

oebate. Some experts even question whether or not the major benents ol

P3 could be obtained by the public sector offering a single design-build (DB)

contract at a nxeo price while retaining all other lunctions in-house.

12

DB

puts contractors in control ol projects, giving them the latituoe to oesign

projects as they builo, in oroer to nno ways ol working within buoget

constraints. While popular with contractors ano governments, architects ano

engineers leel that DB oebases their skills, suboroinates them to pront oriven

contractors, ano potentially sacrinces the quality ol the nnisheo proouct.

Some authors, like Loxley ano Loxley ,2010,, treat DB arrangements

as a form of P3.

13

Others oo not. As we shall see, some recent F3 VlM

appraisals seem to have implicitly accepted DB arrangements as alternatives

to F3s by assuming DB, rather than DBB, in the FSC.

There have been a number ol acaoemic stuoies on F3 perlormance. Some,

such as Iacobacci ,2010,, have unoerwritten the arguments in lavour ol their

use, while others have been more critical.

14

The major criticisms ol F3s are

that olten VlM analyses, il perlormeo at all, are inaoequate. The problems

with these analyses are numerous, and include situations where:

the FSC ,representing a conventional approach, ano the shaoow bio

(representing a P3 approach) that are compared are often not driven by

the same specincations,

the choice ol oiscount rate is olten arbitrary ano sometimes quite high

,as in BC,, which lavours F3s, since the lease costs are long-term,

the assumptions about risk transler are olten excessive ,as high as

!9 lor simpler DBI mooels ano, astonishingly, in excess ol 70 lor

DBIOM projects

15

, ano lack justincation,

the VlM analysis is perlormeo only alter the F3 has been initiateo, which

woulo suggest such analyses are intenoeo to justily oecisions alreaoy

maoe, rather than to guioe oecision-making.

As a result ol such naws, the VlM process is olten heavily weighteo in lavour

of P3s.

11 Columbia Institute, Public-Private

Partnerships: Understanding the Challenges:

A Resource Guide (Vancouver, BC, 2007).

12 John Loxley, Public-Private Partnerships

after the Global Financial Crisis: Ideology

Trumping Economic Reality, Studies in

Political Economy 89 (2012).

13 Loxley with Loxley, Public Service Private

Profits.

14 Authors in favour of P3s include: Mario

Iacobacci, Dispelling the Myths: A Pan-

Canadian Assessment of Public-Private

Partnerships for Infrastructural Investments

(Conference Board of Canada, 2010), http://

www.conferenceboard.ca/documents.

aspx?did=3431. Authors who are more

sceptical include: Aidan R. Vining and

Anthony E. Boardman, Public-Private

Partnerships in Canada: Theory and

Evidence, Canadian Public Administration

51, 1 (2008): 9-44; John Loxley with Salim

Loxley, Public Service Private Profits:

The Political Economy of Public-Private

Sector Partnerships (Winnipeg: Fernwood

Publishing, 2010).

15 Matti Siemiatycki and Naeem Farooqi,

Value for Money and Risk in Public Private

Partnerships, Journal of the American

Planning Association, 78, 3 (2012): 286-299.

Far kl and l nst i t ut e 0ctober 2013

10

Other criticisms ol the F3 approach incluoe concerns that:

the number ol bios receiveo is olten quite low, making it unlikely that

competition will ensure low costs,

the large scale ol F3s oiscriminate against local contractors,

any purporteo elnciencies olten come at the expense ol labour in lower

wages, lewer benents, ano less security,

contract perioos are too large lor elncient monitoring ano control ol

private partners, especially by school boaros ano municipalities,

F3s builo long-term nnancial innexibility into public services, ano

are generally more costly over the project lile-time than traoitionally

oelivereo projects.

It shoulo also be noteo that oilnculties in accessing key oata relateo to the F3

arrangement are lar lrom unique to the Eomonton LRT case. Inoeeo, F3s

are associated with reduced accountability and transparency in the public

sector, because they are often shrouded in the secrecy purportedly necessary

to ensure commercial connoentiality.

16

There is a very strong F3 lobby in Canaoa supporteo by the Canaoian

Council on F3s. It is supporteo by all major construction, nnance, ano

consulting nrms ,incluoing FwC,, as well as a number ol provincial ano

municipal governments. This lobby serves as a strident and persistent

advocate for P3s. The federal government also has a strong bias in favour of

F3s. In 2009, it establisheo a S1.3 billion luno oevoteo entirely to lunoing

F3s, ano rennanceo it in 2013. More importantly, the leoeral government

requires all large inlrastructure projects to be evaluateo to oetermine il they

are suitable lor F3 approaches belore they are eligible lor nnancing through

regular inlrastructure lunoing outlets such as the Builoing Canaoa Iuno.

17

Increasingly, therelore, il municipalities ano others wish to take aovantage ol

leoeral inlrastructure money, they are pressureo to take the F3 approach.

F3s have become quite common since the 1990s. Accurate oata are very

haro to come by, but between 198 ano 2011, 200 F3s were planneo or

implementeo in Canaoa, incluoing 137 that were nnalizeo, at a cost ol

USS71.o billion. Alter a setback relateo to the 2008-09 nnancial crisis, the

pace at which P3s are coming on-stream seems once again to be increasing.

18

16 John Loxley, Asking the Right Questions: A

Guide for Municipalities Considering P3s,

Report Prepared for Canadian Union of Public

Employees, June 2012, cupe.ca/p3guide.

17 Loxley, Public-Private Partnerships after the

Global Financial Crisis.

18 Loxley, Asking the Right Questions.

Wrong Turn: Is a P3 the best way to expand Edmontons LRT?

11

Assessment of the proposed P3

approach to the Southeast Line

Given the secrecy surrounoing the oecision to unoertake the Southeast leg

ol the Valley Line LRT extension as a F3, it is haro to oller a thorough

evaluation. What lollows oraws on what little inlormation has been maoe

available, as well as the wioer acaoemic ano expert literature on F3s. At

the very least, this analysis raises questions that must be lully aooresseo il

the public is to have connoence in Eomonton City Council`s proposal to go

forward with the P3.

1. TRANSPARENCY, ACCOUNTABILITY, AND

ACCESS TO INFORMATION

The City`s approach to transparency, accountability, ano access to

inlormation was maoe quite evioent in a December 2010 inlormation

session lor City Council on the oelivery methoo lor the combineo Southeast

to West LRT Line.

19

Delivereo by then Manager ol Froject Management

8 Maintenance Services Joe Kabarchuk, the guioelines lor the session

containeo some remarkable restrictions on Council members` autonomy ano

democratic rights:

No recoro or minutes ol the inlormation session will be kept

The now ol inlormation must be entirely one way lrom Aoministration

to Councillors

Councillors can only ask clarincation questions

Councillors must not ask questions regaroing justincation lor inlormation

provioeo or actions taken by the aoministration

Councillors must not provioe comments, oirection or instructions to

Aoministration

Councillors must not oiscuss or oebate the inlormation provioeo by

Aoministration among each other

Councillors must not attempt to reach any oecision on the basis ol

inlormation provioeo by Aoministration

Though the intent was that the meeting not be construeo as a Council

meeting, most of these restrictions constitute a serious breach of the

oemocratic lreeoom ano responsibility ol Council members. The

alternative of not agreeing to them, of course, was denial of all access

to the information available. This management edict stood in complete

contraoiction to the City`s F3 policy, which requires that the Fublic interest

19 City of Edmonton, SE and W LRT Delivery

Method: Business Case Results, December 9,

2010.

Far kl and l nst i t ut e 0ctober 2013

12

must be thoroughly examined and discussed, that policy reviews and

oversight should be carried out to ensure transparency, due diligence and

the protection of the public interest, and that P3 processes and outcomes

will be transparent.

20

Since that time, it is apparent that information on the project has been

severely restricted, well beyond even the information restrictions that

characterize P3s elsewhere in Canada. Clearly, the City has chosen to put

its policy ol protecting commercial connoentiality above any concern lor

openness and transparency. Crucial decisions, such as that to proceed with

the P3 and, subsequently on August 29, 2012, to reverse Councils decision

to keep operations and maintenance in-house, were taken at short notice

and in-camera.

21

The almost complete redaction of numbers in the Business Case and related

papers also contradicts yet another component of the Citys P3 policy, which

states that The community will be well informed about the obligations of

the City and the private sector.

22

It should be noted that outline business

cases and the argument for proceeding with the corresponding projects

as P3s have been made available for projects undertaken in cities such as

Winnipeg and Victoria well before the call for proposals. These have given

numerical estimates of the net costs of the PSC as well as of the shadow

bid of the P3. They have also put numbers on different types of risk, and

the estimated allocation between the City and the private partner. See the

example of the 2008 report by Deloitte to Winnipeg City Council, which

lays out the P3 options for the Disraeli Bridge with an estimate of possible

VfM relative to the PSC.

23

The 2008 document authored by Deloitte

suffers from severe shortcomings. Most worryingly, the data in the risk

valuation ano allocation appear to be crucial to the nnal value lor money

ngures ano the recommenoation to proceeo with the F3, but their source

is not given ano their levels are not justineo.

24

Nonetheless, these reports

are fuller than anything Edmonton has released on its LRT P3 proposals.

Their availability would indicate that release of such documents does not

prejuoice commercial connoentiality. Inoeeo, in the case ol the proposeo

wastewater treatment plant for Victoria and region, the whole business case

was released, together with sensitivity analysis around use of alternative

discount rates.

25

As Siemiatycki and Farooqi have argued,

...it is critical that the key project information that underpins the complete VfM

report is publicly released during the project planning process prior to approval,

enabling meaningful assessment and debate of the merits of a PPP compared to other

r.oroot oltrooti.. T/i io.loc coto o ri.ot rot f r.t fooo.io,

expected returns on private investment, and the data used to develop the risk premiums

that are applied to both the PSC and the PPP concessions in the VfM assessment.

26

20 City of Edmonton, Public Private Partnership

(P3) Policy, Policy C555 (Finance and Treasury

Department: May 26, 2010).

21 Council Challenged on Secret Decision to Run

SE LRT Privately, OurLRT News, October 16,

2012, http://ourlrt.ca/council-challenged-on-

secret-decision-to-run-se-lrt-privately/.

22 City of Edmonton, Public Private Partnership

(P3) Policy, Policy C555.

23 Deloitte, City of Winnipeg: Analysis of

Private Sector Involvement for the Disraeli

Bridge, Executive Summary, February 18,

2008, http://winnipeg.ca/publicworks/

MajorProjects/DisraeliBridges/DisraeliF

reewayProjectReportCouncil-May1408.

pdf; Winnipeg Council Minutes, May 14,

2008, http://winnipeg.ca/publicworks/

MajorProjects/DisraeliBridges/DisraeliFreewa

yProjectReportCouncil-May1408.pdf.

24 John Loxley, Public-Private Partnerships

after the Global Financial Crisis, 23.

25 Ernst and Young, Capital Regional District

Core Area Wastewater Treatment Program:

Business Case in Support of Funding from

the Province of British Columbia, Addendum,

September 2, 2010, 23, downloaded

August 22, 2013 from http://www.

wastewatermadeclear.ca/documents/2010-

sept-business-case-addendum.pdf.

26 Siemiatycki and Farooqi, Value for Money,

297.

Wrong Turn: Is a P3 the best way to expand Edmontons LRT?

13

2. NEW TECHNOLOGIES AND SYSTEM

COORDINATION DO NOT REQUIRE P3s

Froponents have argueo that the Southeast to West LRT Line is suitable lor

P3 processes because it is a new line employing new technologies. However,

the use of new technologies does not necessarily demand a P3 approach.

Inoeeo, any expansion ol the LRT network will inevitably incorporate

new technologies relative to the existing line. Il the City can hanole new

technologies in the expansion of old lines, then surely it can handle it in the

creation of new lines.

Furthermore, a P3 approach is certainly not a guarantee of a well-

coordinated system. The decision to proceed with the construction of the

Southeast leg while the West leg remains on holo threatens to introouce

potential complications. The winning biooer on the Southeast project is

requireo to provioe operating ano maintenance costs lor the West leg, a

line they may not get the opportunity to build.

27

As even Councillors aomit,

this allows the possibility of two different companies building different

parts of the LRT system, with a single company dealing with operations

ano maintenance, opening up the possibility ol all kinos ol oisputes ano

litigation, with the City caught in the mioole.

28

Rather than ensuring a

well-coordinated system then, a P3 arrangement in fact sets the stage for

problems with system coordination. Indeed, the beginnings of some of these

problems may already be apparent in Edmonton.

The projecteo LRT expansions that will be hanoleo in the traoitional

manner ano operateo in house will require the City to builo up its project

planning and management capacity. Using the private sector to build and

operate the Southeast to West Line simply oelays the builoing ol that

capacity. The existing LRT system seems to work elnciently, ano there are no

obvious reasons why it could not be expanded without use of P3s and their

expensive nnancing.

Unlortunately, Eomonton City Council has not heeoeo this call lor public

release ol key inlormation. As a result, Eomontonians have been lelt

wondering about the wisdom of proceeding with the construction of the

Southeast leg ol the Valley Line LRT extension as a F3.

27 Ryan Tumilty, Edmonton Still Missing Funds

for LRT Project, Metro, March 14, 2013, http://

metronews.ca/news/edmonton/596281/

edmonton-still-missing-funds-for-lrt-

project/.

28 Ibid.

Far kl and l nst i t ut e 0ctober 2013

14

3. THE PUBLIC SECTOR COMPARATOR AND

VALUE FOR MONEY COMPARISONS WITH

OTHER P3s

Froponents ol unoertaking the Southeast Line through a F3 arrangement

have sought to demonstrate the superiority of the P3 approach by citing the

VlM outcomes achieveo with other F3s in Canaoa. Ior example, the VlM

ol the Alberta Schools Froject Fhase 1 is given as S118 or 1.7.

29

Alberta`s

own assessment ol that project puts the VlM at S97 million or 13.3.

30

The Alberta Schools Froject Fhase II is saio to yielo 29.3 over the FSC.

31

The VlM quoteo lor the South East Stoney Trail Ring Roao, Calgary, is

saio to be a remarkably high 7.3.

32

The comparisons between the VlM purporteoly achieveo in other F3s ano

the VlM that may ensue lrom the Southeast Line cannot be accepteo at

face value. The problem is this: most public sector comparators employ the

traoitional DBD or only partial DB. The business case prepareo by FwC

in relation to the Southeast LRT project, however, employs DB. Using DB

typically results in a lower VlM, as much ol the construction risk woulo be

transferred to the private sector in exactly the same way as it would under

the F3. Certainly, applying DB to the FSC ol these other projects coulo be

expecteo to reouce the VlM ol the F3 signincantly.

As a result, it is incorrect to make any sort ol oirect connection between

the VlM calculateo in relation to other F3s ano that expecteo lrom the

Southeast LRT extension. Such connections have the potential to misleao

the public about the VlM ol proceeoing with the Southeast Line as a F3.

29 PricewaterhouseCoopers, Business Case:

Southeast and West LRT Project, February

2011, 81.

30 Government of Alberta, P3 Value for Money

Assessment and Project Report: Alberta

Schools Alternative Procurement (ASAP)

Project Phase 1, June 2010, 21, http://

education.alberta.ca/media/1320820asapip3

valueformoneyassessmentandprojectreport.

pdf.

31 PricewaterhouseCoopers, Business Case, 81.

32 Government of Alberta, P3 Value for Money

Assessment and Project Report: Southeast

Stoney Trail (SEST) Ring Road Project,

Calgary, Alberta, September 2010, 4, http://

www.transportation.alberta.ca/Content/

docType490/Production/SESTVFM.PDF.

33 Stuart Murray, Value for Money? Cautionary

Lessons about P3s from British Columbia

(Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives,

June 2006), 39.

34 Ibid., 40.

4. THE VALUE FOR MONEY COMPARISONS WITH

OTHER LRT PROJECTS

Froponents ol proceeoing to builo the Southeast Line as a F3 make much ol

the superior perlormance ol BC`s Canaoa Line, which seems to have been

useo as a template lor the Southeast LRT. However, there are a number ol

reasons that Edmontonians might do well to be cautious about emulating

the BC example.

Firstly, there are concerns about the process through which the decision was

maoe to unoertake the Canaoa Line as a F3. Stuart Murray has argueo

that the oecision to make the project a F3 was taken well belore the VlM

estimate was made.

33

The VlM assessment, by FwC, was maoe public only

in 200o, well alter construction hao begun.

34

Ano the assessment containeo

a number ol basic naws, such as oillerences in the assumptions unoerlying

the F3 mooel ano the FSC, ranging lrom train lrequencies, through

Wrong Turn: Is a P3 the best way to expand Edmontons LRT?

15

construction techniques, to rioership lorecasts. Ultimately, the VlM laileo to

compare apples with apples, which makes the analysis meaningless.

35

Ellorts to clarily assumptions in the VlM report by Ronalo Farks ,2009,, an

investigative ano lorensic accountant at Blair MacKay Mynett Valuations

Inc., Vancouver, concluoeo that Fartnerships BC useo an approach to VlM

that systematically discriminated in favour of P3s by using unsubstantiated

but likely exaggerateo estimates ol the risk translerreo, ano higher than

warranteo oiscount rates. Farks examineo lour BC projects. On the Canaoa

Line, risk transler was estimateo at S2!2 million lor the FSC ano S30 million

lor the F3, but no oetails or quantitative justincation were given lor this.

36

Since generally, where inlormation was available, the nominal, unoiscounteo

value ol costs were higher lor F3s than lor the FSCs, the assumption about

the discount rate to bring these costs into present value was crucial. For the

Canaoa Line, the VlM analysis useo a o oiscount rate to arrive at the

nnal VlM ol S92 million. This rate exceeoeo the transit authority`s cost ol

borrowing, and favoured the P3 by heavily discounting long-term public

sector lease payments to the private sector. Hao a rate ol even been

useo, the VlM woulo have lallen to only 1.!8 ol the FSC`s net present

value ol costs. A rate ol !. woulo have brought the VlM ol the F3 to

zero, and anything less, such as the Provinces long-term cost of borrowing

ol !.38 in 2008-09, or the 3. useo in F3s in the UK, woulo have leo to

the FSC oelivering net savings relative to the F3.

37

Seconoly, perhaps even more oisconcerting lor Eomontonians may be the

cuts in project scope that ensueo in BC as the costs ol the Canaoa Line

project escalateo. These involveo reouctions in the number ol stations ano

changes in the physical nature ol the line ano the way it was built.

38

Some

changes, such as shorter station lengths, may present problems of system

expansion in the future.

39

There were also several million dollars worth of

scope transfers, moving costs from the P3 to the public sector.

40

In sum,

the Canaoa Line project haroly seems like an example to emulate, whether

with respect to government accountability or the reouceo quality ol the

infrastructure that was built.

Froponents ol unoertaking the Southeast LRT extension as a F3 also

relerence another BC project, the 11km Evergreen LRT. This F3 takes

the lorm ol a oesign-builo-nnance ,DBI, arrangement, given that it is

a connection to an existing line, with responsibility for operations and

maintenance to remain with public provioer Translink. The 2013 project

report on the Evergreen LRT compared the DBF arrangement with a

FSC incorporating DB, ano concluoeo that the F3 woulo oller a VlM ol

S13! million or 10.1.

41

This relatively large VlM was the result ol the

successful bidder building a single line tunnel rather than a double one,

thereby speeoing up construction ano reoucing site risk. However, there is

no evidence that a DB approach would not also have incorporated these

35 Ibid., 41.

36 Ronald Parks, Evaluation of Public-Private

Partnerships: Costing and Evaluation

Methodology (Vancouver: Blair Mackay

Mynett Valuations, 2009), 26. Report

prepared for Canadian Union of Public

Employees.

37 Ibid., 26.

38 Ibid., 39.

39 Taras Grescoe, Straphanger: Saving Our Cities

and Ourselves from the Automobile (Harper

Collins Canada, 2012) as quoted in Mack

D. Male, P3 or not P3? Thats the Question

as We Try to Fund Edmontons Future LRT,

MasterMaq, March 14, 2013, http://blog.

mastermaq.ca/2013/03/14/p3-or-not-p3-

thats-the-question-as-we-try-to-fund-

edmontons-future-lrt/.

40 Murray, Value for Money?, 39.

41 Partnerships BC, Project Report: The

Evergreen Line Rapid Transit Project

(Vancouver, March 2013). The discount rate

used was the private partners internal rate

of return on this very short-lived project of

3.94%.

Far kl and l nst i t ut e 0ctober 2013

16

aojustments. As a result, the supposeo VlM may be nothing more than

imaginary. This example highlights a logical inconsistency in using DB in the

FSC: the DB approach invites creativity ano nexibility, with the result that

its precise nature cannot be known until proposals are receiveo. As a result,

VlM calculations that incorporate DB, like those unoerlying Eomonton`s

Southeast LRT F3 project, oller little by way ol concrete inlormation to

guioe responsible oecision-making.

5. PRIVATE OPERATION OF THE SOUTHEAST

LINE PROVIDES MUCH OF THE SUPPOSED

VALUE FOR MONEY. HOW?

The oocuments available on the Southeast Line make clear that taking

operation out ol the F3 approach reouces private sector returns signincantly,

and reduces the relative attractiveness of the P3 approach relative to the

FSC. Thus, the VlM calculation lalls lrom between 3 ano 10 to between

-2 ano o, with a likely 2. This brings the VlM calculation perilously

close to zero, meaning that the F3 Shaoow Bio is not clearly superior to that

ol the FSC with public operation ol the line. Retaining operations within

the F3 is what raises the VlM, bringing it supposeoly close to that ol other

F3s in Canaoa. This raises the question ol what the private sector woulo be

ooing to reouce operating costs in the F3. Coulo it be that the line woulo

use lewer workers, reouce wages ano benents, or use uncertineo labour?

What is it about private operation that lowers costs relative to the FSC? In

the absence of further information, there is reason to be concerned that

supposeo VlM might come at the expense ol those employeo to work on the

project.

6. ASPECTS OF THE RISK TRANSFER IN THE

VALUE FOR MONEY CALCULATION ARE

DIFFICULT TO BELIEVE

Risk transler is what is typically useo by F3 proponents to justily VlM.

However, there is reason to think that any risk transler within the Southeast

LRT P3 arrangement is minimal at best.

The FSC useo to evaluate VlM in relation to the Southeast LRT project is

based on a design-build arrangement, which commits the contractor to a

nxeo sum ano a nrm oelivery oate. Using DB ,as opposeo to DBB, as a FSC

shoulo reouce any risk assumeo to be translerreo to the private sector ouring

the important construction phase. Inoeeo, ol the 31 risks ioentineo in FwC`s

Wrong Turn: Is a P3 the best way to expand Edmontons LRT?

17

Southeast LRT Business Case, some 20 seem to relate to the construction

phase. It is haro to see why most ol them woulo not apply equally to the

FSC ano F3, e.g. tunnelling costs, utilities relocation, oesign risk, etc.

42

The

payment ol progress, or milestone payments, also reouces various risks,

especially nnancial, ol the private sector in construction phase. Again, this

shoulo be common to both the FSC ano the F3.

Even when DBB is useo in the FSC, the assumptions ol large amounts ol

risk transler must be treateo with a high oegree ol skepticism. Risk transler

assumptions are rarely spelled out fully, and if experience elsewhere is to be

taken seriously, are olten greatly exaggerateo.

43

In a situation such as the

Southeast LRT, where the FSC employs a DB rather than a DBB, there is

substantial reason to ooubt that risk transler is signincant.

Iurthermore, since unoer the proposeo arrangement lor the Southeast LRT

F3 there is no oemano or revenue risk oevolveo to the private sector, revenue

assumptions shoulo be lairly similar lor both the FSC ano the F3 Shaoow

Bio. This leaves only the maintenance risk as a potential area in which the

F3 is projecteo to oller signincant aovantages over the FSC. Maintenance

risk woulo seem to reler to a situation in which buoget constraints woulo

oelay or make impossible necessary maintenance work. While maintenance

provisions unoer a F3 woulo be guaranteeo, it is haro to believe that City

budget constraints would be so severe that public sector maintenance

would be impaired on infrastructure such as an LRT where safety must be

paramount.

Until the risk calculations estimateo by FwC are maoe public, skepticism

about the likely oegree ol risk transler in the case ol the Southeast Line is

warranted.

42 PricewaterhouseCoopers, Business Case, C3.

43 For the UK example, see: Dexter Whitfield,

The Global Auction of Public Assets: Public

Sector Alternatives to the Infrastructure

Market and Public Private Partnerships

(Spokesman: Nottingham, UK, 2010). For

Canadian perspectives, see: Hugh Mackenzie,

Doing the Math: Why P3s For Alberta Schools

Dont Add Up, prepared for CUPE Alberta,

2007; Matti Siemiatycki and Naeem Farooqi,

Value for Money and Risk in Public Private

Partnerships, Journal of the American

Planning Association, 78, 3 (2012): 286-299.

7. THE ADDITIONAL FINANCING COSTS OF THE

P3 ARE HUGE

Cost escalation ano the absence ol clear nnancing arrangements make it

very oilncult to assess the aooitional costs ol using private as opposeo to

public nnancing. Using plausible assumptions, however, we can estimate

these additional costs.

Given the nnancing pronle suggesteo by FwC, it woulo appear that

private lunoing woulo now be expecteo to reach one thiro ol S1.8 billion,

or S9! million, ol which S9 million might be equity, ano S3 oebt

or bono nnanceo. The FwC 2011 report suggests that, baseo on their

market sounoings with private businesses, any payments on private oebt

will be arouno 2 more costly than oirect borrowing. We oo not have 30

year borrowing costs lor Eomonton, but lor Winnipeg these are !.8.

Far kl and l nst i t ut e 0ctober 2013

18

Since Eomonton appears to be able to borrow at slightly lower rates than

Winnipeg, we estimate Eomonton`s likely borrowing costs at !. p.a. This

woulo mean the F3 borrowing rate might be o. p.a. The aooitional

costs ol borrowing at this rate over 30 years, relative to the estimateo cost

ol Eomonton borrowing oirectly, is likely to be S2!1 million over 30 years,

or S131 million in present value terms ,oiscounteo at Eomonton`s estimateo

cost ol borrowing ol !.,. Equity returns are estimateo by FwC to be

between 10 ano 1. This suggests payments to equity ol between S177

million ano S2o million over 30 years in nominal, unoiscounteo terms, or

between S9. million ano S1!3.3 million in present value terms.

In short, private borrowing ano equity will cost Eomonton between S!00

million ano S00 million more in nominal terms over the liletime ol the

project, or between S227 million ano S27 million more in present value

lrom the oate ol operations ol the line, than il the City hao nnanceo the

project itsell.

44

8. PROVISIONS TO ENABLE THE PUBLIC TO

SHARE IN GAINS RELATED TO REFINANCING

OR EQUITY FLIPPING ARE LACKING

Once the construction phase is complete ano the risk associateo with

it no longer relevant, it is common lor F3 projects to be rennanceo. It

is increasingly common for the public sector to share in the gains from

rennancing. Il the Southeast Line is to proceeo as a F3, provision shoulo be

maoe lor the City to share in any rennancing gains.

Apart lrom rennancing, increasingly the equity ol F3s in Canaoa is

being nippeo ano the public sector ooes not share in any gains.

45

In the

UK, returns ol over 0 were earneo on over 1,200 F3 equity nips.

46

In the absence ol any provision lor sharing pronts relateo to such nips,

Edmontonians stand to lose out as the private sector wins big.

44 It should be noted that the profile of the debt

(whether bonds or loans, number of years the

debt will be outstanding, borrowing costs,

etc.) is not known at this time. If, for instance,

the debt were to be repaid earlier, the

additional borrowing costs would be lower

than estimated.

45 Keith Reynolds, How Flipping Equity in P3s

Boosts Profits and Ends Up With the Projects

Being Run From Channel Islands Tax Havens,

Policy Note (CUPE-BC: March 9, 2011), http://

www.policynote.ca/how-flipping-equity-in-

p3s-boosts-profits-and-ends-up-with-the-

projects-being-run-from-channel-islands-

tax-havens/

46 Dexter Whitfield, The 10 billion Sale of

Shares in PPP Companies: New Sources of

Profit for Builders and Banks (European

Services Strategy Unit: County Kerry, Republic

of Ireland, Tralee, January 2011), http://

www.european-services-strategy.org.uk/

news/the-ps10bn-sale-of-shares-in-ppp-

companies-new/.

Wrong Turn: Is a P3 the best way to expand Edmontons LRT?

19

9. THE WISDOM OF 30 YEAR CONTRACTS

Locking the City ol Eomonton into a 30 year nnancing oeal brings with it a

host ol potential problems. Iirst ol all, it binos the City into payments that

are the equivalent ol oebt. Debt by another name is still oebt. Il the intent

ol the proposeo F3 is to reouce Eomonton`s nnancing problems, the answer

is not to be found in P3s.

The long time lrame also locks Eomonton into rigio operations,

maintenance, ano lile-cycle nnancial commitments that might prevent the

City benentting lrom potential new ways ol ooing things over the project

lifetime. It also builds rigidities into the LRT system as a whole over that

long time period.

10. PUBLIC OPINION AND THE LRT P3

Usually in Canaoa, F3s proceeo without any lormal checking on whether

or not the public supports this method of service delivery. In Regina,

however, a lormal relerenoum in September 2013 testeo public support

for a waste water treatment plant proposed as a P3.

47

While no such plans

exist in relation to the F3 proposeo lor the Southeast Line, Fublic Interest

Alberta oio commission the Environics Research group to conouct a ranoom

sample survey of households, to ascertain the level of public support for

the P3, and for handing over the operations to a private company. The

nnoings reveal oissatislaction both with the leoeral government lor lorcing

the F3 arrangement onto Council as a conoition lor lunoing ,o1 either

oisagreeo or strongly oisagreeo,, ano with the Council lor taking the

decision to privatize operations behind closed doors without a public debate

,71 opposeo,. A clear majority ol people surveyeo opposeo privatizing

the operations ,o!, ano expresseo concerns about the integration ol the

F3 into the LRT system as a whole ,o8,, about loss ol accountability il

things were to go wrong ,7,, about costs rising to guarantee pronts lor

the private partner ,o9,, ano about reouceo quality ol service ,9,.

48

These results are signincant statistically ano shoulo give the Eomonton City

Council cause lor renection on its oecisions.

47 Paul Dechene, Hey, Regina, Looks Like Youll

Get That Waste Water Referendum After

All, Prairie Dog, July 22, 2013, http://www.

prairiedogmag.com/congratulations-regina-

looks-like-youll-get-that-waste-water-

referendum-after-all/.

48 Environics Research Group, Public Interest

Alberta; Edmonton LRT Expansion Banner

Tables, 2013.

Far kl and l nst i t ut e 0ctober 2013

20

Conclusions and

recommendations

This review has examineo the case put lorwaro lor oelivering the Southeast

leg ol the Valley Line LRT extension as a F3 or, more precisely, as a

DBIOM F3. While there have been challenges to the planneo expansion

ol the LRT system, both conceptually ano in relerence to specinc routes

chosen, assessing these falls outside the scope of this document. The main

nnoing ol this review is that the arguments lor builoing the Southeast Line

using a P3 approach are far from convincing.

To juoge by what has been maoe available ol the assessments unoertaken

to oate, there is reason to ooubt that any potential risk transler is sulncient

to establish the superiority of a P3 over a traditional DBB or narrow

DB approach, when the estimateo aooitional nnancing costs ol a F3 are

considered.

Worryingly, there remain many unanswereo questions about the City

of Edmontons plans, in large measure because of the layers of secrecy

that surround the P3 proposal. The obsession with so-called commercial

connoentiality at the very earliest stages ol evaluation, belore the private

sector has even submitted a bid, is unwarranted and unnecessary, and

contraoicts important tenets ol the City`s own F3 policy.

What is perhaps even more troubling is that Eomonton City Council is

signalling its intention to proceeo with the project as a F3, oespite clear

public misgivings about the aooption ol a F3 approach, about the City being

forced into a P3 to obtain federal funding, about fears of problems with

system coordination, and about the wisdom of the private sector running the

operations and maintenance.

Irom what little is known about the project, the case lor the F3 approach

seems weak. As the risk transler claims seem questionable, the general

argument lor the F3 provioing VlM is oubious. Serious questions can be

raiseo about the lavourable VlM numbers in other F3 projects, both in

LRT ano in other sectors, useo by the consultants to justily ano promote

the F3 mooel. Il the F3 ooes go aheao as proposeo, the City will be paying

well above its own borrowing cost to pay private sector oebt ano pronts.

The 30 year contract perioo lor operations poses potential system ano

nnancial innexibility issues lor the City. Much ol the planneo expansion

to Edmontons LRT system will be built using the traditional approach,

meaning that the City will be obligeo to oevelop its technical capacity

to manage new lines and ensure system coordination. In using a P3

arrangement on the Southeast leg ol the Valley Line, the City woulo miss an

opportunity to begin to build this capacity.

Wrong Turn: Is a P3 the best way to expand Edmontons LRT?

21

The Southeast leg ol the LRT extension project has alreaoy encountereo

problems with cost escalation ano nnancing sulnciently severe to call into

question project timelines. While resulting oelays create haroship lor the

people of Edmonton who are awaiting much-needed improvements to

transportation inlrastructure, there may be a signincant silver lining il a

oelay provioes an opportunity to revisit the question ol how to manage the

LRT expansion so as to best serve the public interest.

RECOMMENDATIONS

1. Baseo on available inlormation, the City shoulo not proceeo with the F3

option, but builo the Southeast Line on the traoitional Design-Bio-Builo

or a Design-Build basis.

2. Il the City insists on consioering the F3 option, it shoulo open up all

documents and calculations employed so far in the evaluation of this

option, so that they can be publicly scrutinized.

3. The City ano FwC shoulo clearly justily ano explain the assumptions

that have gone into the assessments that have found in favour of a

P3 approach, and be prepared to discuss these assumptions in public

meetings.

4. Greater caution shoulo be exerciseo in making comparisons between the

value lor money purporteoly achieveo through other F3 projects ano that

expecteo lrom the Southeast Line. Comparisons shoulo be maoe only

when the public sector comparators employeo in the various projects are

truly comparable.

5. Eomonton City Council shoulo take seriously the expresseo concerns

ol the public about proceeoing with the Southeast Line through a F3

approach.

Far kl and l nst i t ut e 0ctober 2013

22

Appendix 1:

CITY OF EDMONTON POLICY ON

PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIPS

Edmontons policy on P3s is broadly consistent with that of the provincial

government.

49

City policy provioes lor the F3 approach to be consioereo lor

complex projects costing over S30 million that promise to:

a. deliver improved services and better value for money through

appropriate allocation ol resources, risks, rewaros, ano

responsibilities between the City ano private sector partners,

b. enhance public benents through clearly articulateo ano manageo

outcomes,

c. leverage private sector expertise and innovation opportunities

through a competitive ano transparent process,

d. create certainty arouno costs, scheoule, quality, ano service oelivery,

and

e. optimize use of the asset and included services over the life of the

P3.

50

Value lor money ,VlM, is oenneo in quantitative terms as the oillerence

between the risk-aojusteo net costs to the City ol oelivering the project using

traditional methods, and those incurred in delivering it as a P3. Net costs are

to be calculated in present value terms, meaning that all future costs, minus

revenues, are oiscounteo by an interest rate back to present oay values. A

public sector comparator ,FSC, is to be orawn up lor net costs likely to be

incurreo il the project proceeos along traoitional lines, ano this is to be

compared with a shadow bid for the P3 approach. The term shadow bid

is used because the P3 costing is an estimate only, since it precedes actual

private sector bids. If the present value of net costs of the shadow bid is

estimated to be lower than that of the conventional approach as represented

by the FSC, then the F3 approach is to be consioereo superior ano will be

pursued.

While the policy ooes not state which oiscount rate is to be useo, the practice

across Alberta is to use the public sector borrowing rate. While this practise

results in less of a bias in favour of P3s than the high discount rates used in

BC that are baseo at least partially on private sector returns to capital, they

are still higher than experts suggest they should be.

51

The policy also allows lor qualitative value lor money calculations to be useo

alongsioe the quantitative ones, but how these are to be unoertaken is not

elaborated upon.

52

49 Government of Alberta, P3Public Private

Partnerships: Alberta Infrastructure and

Transportations Management Framework:

Assessment (Edmonton, September 2006),

http://www.infrastructure.alberta.ca/

Content/doctype309/production/ait-p3-

assessmentframework.pdf; Government of

Alberta, Albertas Public-Private Partnership

Framework and Guideline (Treasury Board:

Edmonton, March 2011).

50 City of Edmonton, Fast Track LRT.

51 John Loxley, Public-Private Partnerships

after the Global Financial Crisis.

52 Ibid., 2.

Wrong Turn: Is a P3 the best way to expand Edmontons LRT?

23

The sharing ol risk between the City ano private partners is consioereo

important. All risks shoulo be clearly ioentineo, assesseo quantitatively, ano

allocated to the party best able to handle them.

The policy lays out an organizational structure for implementing P3s,

provioing lor an Inoepenoent Iairness Aovisor to oversee the procurement

process, ano lor a Steering Committee, a Multi-Disciplinary Froject Team,

ano an inoepenoent Corporate F3 Iunction with the City Aoministration.

Council is a central component ol this structure, being responsible lor

appraising and approving P3 assessments, and monitoring P3 progress.

The intent of following the P3 approach is to provide incentives to the

private partner to meet cost ano timing targets, ano maintain elnciency ano

creativity throughout the project`s liletime.

As ol August 2013, the Southeast Line woulo appear to be at the Froject

Development Stage, with Requests lor Qualincations expecteo to be calleo

in October 2013.

53

Iigure 2 outlines the process through which F3s must pass.

53 Kent, Edmonton Council Votes to Keep

Seeking Southeast LRT Grants.

Far kl and l nst i t ut e 0ctober 2013

24

Figure 2. P3 project process lifecycle and approval

Figure 2: City of Edmonton, Public Private Partnership (P3) Policy, Policy C555 (Finance and Treasury Department: May 26, 2010).

Wrong Turn: Is a P3 the best way to expand Edmontons LRT?

25

Appendix 2:

REVIEWING THE DOCUMENTS: secondary

screening, business case, outline business

cases, and addendums

Very little publisheo inlormation is available on the proposeo LRT expansion

using a F3 arrangement. What lollows reviews all the oocumentation that

has been maoe available, both olncially ano unolncially, to show how the

project has evolveo. We are not aware ol any other oocuments that oeal with

the business case lor the F3 approach relative to builoing the project along

conventional lines.

Initially, FricewaterhouseCoopers ,FwC, was requesteo to unoertake what

is calleo a seconoary screening ol the projects, which means a high level

assessment of the wisdom of different alternate delivery methods. This

was completeo in August 2010, ano presenteo to an inlormation session

lor Eomonton City Councillors in December 2010.

54

Subsequently, FwC

was requesteo to prepare a Business Case, or a oetaileo nnancial assessment

ol alternative approaches, ano this was completeo in Iebruary 2011 at an

estimateo cost ol S900,000.

55

In January 2012, Council oecioeo to proceeo

initially only with the Southeast extension. Again, FwC was commissioneo

to unoertake a high-level Outline Business Case aooenoum, which was

prepareo in April 2012.

In May 2012, Council requesteo FwC to review the April exercise lor

the Southeast extension, but this time with the operating ol the system

remaining within City hanos. This was completeo in June 2012. Each ol the

FwC business case assessments concluoeo in lavour ol the City pursuing a

F3 lormat lor the project.

PwCs secondary screening of the Southeast

and West Lines projects, 2010

The nrst oocument relating to the business case lor applying a F3 mooel

to the LRT extension in Eomonton is a summary ol FwC`s seconoary

screening ol the Southeast ano West Lines projects. This report has not

been made available, but it has been possible to access a summary of a

FowerFoint presentation given to interesteo Councillors at an inlormation

session helo on December 9, 2010.

56

The summary indicates that the

presentation consisted of an overview of P3 policy, commercial criteria to

be followed, proposed performance measures, the meaning of and factors

consioereo in value lor money, an outline ol the quantincation ol risk, ano

54 City of Edmonton, SE and W LRT Delivery

Method.

55 City of Edmonton, Fast Tracking LRT

Construction.

56 City of Edmonton, SE and W LRT Delivery

Method.

Far kl and l nst i t ut e 0ctober 2013

26

a high-level summary ol the Business Case results. The conclusion was that

the F3 approach is valio, proposing a 30 year term Design-Builo-Vehicle-

Iinance-Operate-Maintain mooel ,DBVIOM,.

The presentation summary indicates a P3 would have a positive value

lor money ol between ano 10 relative to the FSC. In this case, the

FSC was not baseo on conventional methoos ol oelivery, but rather on

a design-build alternative that is said to offer more reliability in terms of

construction timing and costs. The presentation summary stresses that this

value for money would only be valid if the two lines were built at the same

time, the plan being to complete them by 201o. What the presentation

summary did not do, however, is show how these conclusions were arrived

at in quantitative terms. No oata are given on the value ol the FSC or the

Shaoow Bio, nor is there any inlormation given on how risks were quantineo

or allocated between the two potential partners. The presentation summary

is also silent on the discount rate used.

The presentation summary states that nnancing woulo be o7 lrom the

public ano 33 private, but there is no breakoown ol where the public

money woulo be louno, ano no oistinction between private equity ano

private borrowing. Once the lines become operational, the private sector

woulo receive monthly payments to cover its nnancing costs, together with

what is calleo a perlormanceavailability` payment to cover pronts. These

payments woulo be aojusteo as rioership changeo over time.

The business case: Southeast and West LRT

project, 2011

The FwC 2011 Business Case oocument was not maoe public ano, when

requesteo, neither the City nor FwC volunteereo to release it. As a result,

the Farklano Institute sought access unoer the Ireeoom ol Inlormation

ano Frotection ol Frivacy Act in May 2013, ano was given a severely

redacted version two months later. The redactions are so severe that barely

a number is lelt in the oocument. As a result, it is impossible to challenge

FwC`s calculations by changing assumptions or by using alternative nnancial

parameters. Nonetheless, the report does throw light on the process

that FwC went through to justily the F3 approach, ano it also suggests a

commercial structure, nnancial structure, ano the broao terms unoer which

a F3 is likely to be pursueo.

In assessing value lor money, the FwC oocument nrst lists all likely base

costs ano revenues belore risk is taken into account. Costs incluoe all capital

costs ano all operating costs, as well as project oevelopment costs that the

City is expecteo to incur, incluoing those lor property acquisition, social

Wrong Turn: Is a P3 the best way to expand Edmontons LRT?

27

and environmental assessment, legal services, administration, and publicity.

Regular maintenance ano lile-cycle or major asset replacement costs are also

listed. No data is available for any of these amounts, though the maintenance

section ooes connrm that the project is a thirty-year one. Base revenues are

mainly fares. The average fare per rider is redacted, as are non-fare sources

of revenue. Ridership numbers are given for both the opening date of

January 2017 ano lor 20!1, the City estimates a oaily rioership ol 33,800

lor the Southeast Line rising to !,800, while the equivalent numbers lor

the West Line are !0,000 rising to o3,00. The growth rate is interpolateo at

1.27 p.a. lor the Southeast Line ano 1.3! p.a. lor the West.

This base oata is then useo in oeveloping the Fublic Sector Comparator

,FSC,, unoer which it is assumeo that the City hires a contractor to oesign

ano builo the project, enters into a separate contract lor vehicle supply,

ano operates ano maintains the project itsell. The report replicates the

approach taken in the seconoary screening by comparing a shaoow F3 bio

with a Design-Builo ,DB, approach. Major assumptions on which both

the FSC ano F3 are oevelopeo incluoe completion ol construction by 31

December 201o, operations commencing on 1 January 2017, a thirty year

operations ano maintenance perioo, ano project enoing 31 December 20!o.

1 January 2011 being the oate lor oiscounting costs to present value, ano

the oiscount rate baseo on the City`s expecteo cost ol borrowing ,precise

number is reoacteo,. The use ol the City`s borrowing costs lor oiscounting is

less lavourable to the F3 approach than the use ol higher rates as in BC, but

more favourable to it than using social discounting rates.

57

The base costs ano revenues ol the FSC are nrst strippeo ol any provision

lor contingencies ano then aojusteo lor risk. The process ol quantilying

risk is laio out in some oetail in appenoices. It involveo nrst oeveloping a

matrix ol risks that might allect oesign ano construction, operations ano

maintenance, ano nnancial ano commercial aspects ol the project. So, in

the construction phase, lor instance, there might be risks associateo with

environmental or other approval oelays, property acquisition, construction

oelays, strikes, etc, while on the nnancial ano commercial sioe, there might

be changes to interest rates ,borrowing costs,, oebt availability, nnancial

positions ol sponsors, costs ol insurance, etc. These potential risks were

oetaileo ano presenteo to a two-oay workshop attenoeo by representatives

ol the City, FwC, CH2M Hill, Spencer Environmental, ano Thurber

Engineering. This apparently gave rise to a quantincation ol risk in the

matrix, ano an assessment ol its probability ano its likely oistribution

between the FSC ano the F3 Shaoow Bio. In other woros, the City`s

exposure to risk will be oillerent oepenoing on which approach is taken.

This oata was then run through a soltware program which conoucteo Monte

Carlo simulation, or ranoom sampling analysis, in oroer to oerive probability

57 Loxley, Public-Private Partnerships after the

Global Financial Crisis.

Far kl and l nst i t ut e 0ctober 2013

28

ol risk oistribution in terms ol low ,,, most likely, ano high impact ,9,

outcomes.

58

These risk estimates were then applieo to costs ano benents ol

both the FSC ano the F3 Shaoow Bio in the value lor money calculation.

Every aspect ol the risk oata was, however, reoacteo in this report, so there is

no way ol knowing how reasonable the assumptions are.

The VlM exercise concluoes that the F3 shaoow bio ollers a cheaper

alternative, but by how much is redacted. This conclusion is said to hold

even after a sensitivity analysis is applied to the data by varying assumptions

about oiscount rates, private borrowing costs, F3 elnciency, oillerent oegrees

ol public nnancing, ano a reouction in the contract term lrom 30 to 1

years. This analysis gives a range ol VlM results, some higher ano some

lower than the base VlM. Again, though, this oata is not maoe available lor

scrutiny.

59

The results are saio to compare lavourably with VlM assessments

ol 22 other Canaoian F3s, incluoing that ol the Canaoa Line in BC, upon