Professional Documents

Culture Documents

28sici 291099 078x 28199802 2913 3A1 3C11 3A 3aaid Bin6 3e3.0.co 3B2 1

Uploaded by

Lata DeshmukhOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

28sici 291099 078x 28199802 2913 3A1 3C11 3A 3aaid Bin6 3e3.0.co 3B2 1

Uploaded by

Lata DeshmukhCopyright:

Available Formats

Behavioral Interventions, Vol.

13, 1119 (1998)

THE EFFECTS OF BONUS CONTINGENCIES IN A

CLASSWIDE TOKEN PROGRAM ON MATH

ACCURACY WITH MIDDLE-SCHOOL STUDENTS

WITH BEHAVIORAL DISORDERS

James C. Swain and T. F. McLaughlin

Gonzaga University, Spokane, WA, USA

The eects of bonus points contingent on 80% accuracy in math with four middle-school special

education students with behavior disorders were examined. A multiple-baseline design across

students was used to evaluate the eects of bonus points. The overall results indicated that higher

accuracy was found for math assignments during the bonus points condition than during baseline.

This overall outcome was replicated for each subject in the study. The benets of implementing a

bonus contingency within an ongoing classroom token economy with middle-school students with

behavior disorders are discussed. # 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Behav. Intervent., Vol. 13, 1119 (1998)

Application of behavioral techniques in various school settings continues to

expand (Kazdin, 1977; McLaughlin & Williams, 1988; O'Leary & O'Leary,

1976). Token-reinforcement programs have been successfully employed at

various grade levels and with diering school populations (see e.g. Long &

Williams, 1973; McKensie, Clark, Wolf, Kothera, & Benson, 1968; McLaughlin

& Malaby, 1972; Strandy, McLaughlin, & Hunsaker, 1979; Stewart &

McLaughlin, 1986; Williams, Williams, & McLaughlin, 1991). It has been

noted that token programs, while one of the most eective and empirically

validated classroom management procedures, have received less empirical

validation in the professional literature (Williams et al., 1991; Naughton &

McLaughlin, 1995).

For token programs to have a place in school systems they should be shown to

be eective, easy to implement, enjoyed by pupils, and compatible with school

policy (Naughton & McLaughlin, 1995). Most token programs employ either

management schemes or back-up reinforcers that many in school settings would

nd dicult to implement in their respective classrooms such as extra personnel,

complex data collection systems, or expensive back-up consequences.

* Correspondence to: T. F. McLaughlin, Chairperson, Department of Special Education, School of

Education, Gonzaga University, Spokane, WA, USA.

CCC 10720847/98/01001109$17.50

# 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

12

J. C. Swain and T. F. McLaughlin

In the present report, available back-up activities were employed and school

district policy was not violated in their selection of such back-up items. Also, an

entire class of special education students was placed under the token program

with available sta used to implement and manage the token system.

However, many token-reinforcement programs have required (i) outside

personnel for their management (Ringer, 1973), (ii) special outside observers for

data collection (O'Leary & Becker, 1967; O'Leary, Becker, Evans, & Saudargas,

1969; Walker, Hops, & Feigenbaum, 1976), (iii) back-up reinforcers such as

candy or trinkets which may not be readily available or compatible with school

district policy (Bolstad & Johnson, 1972; McKensie et al., 1969; O'Leary et al.,

1969) or (iv) the use of social behaviors as measures of eectiveness (Long &

Williams, 1973; O'Leary et al., 1969; Shook, LaBrie, Vallies, McLaughlin, &

Williams, 1990).

Most of the research dealing with token reinforcement procedures has taken

place in elementary school settings (Kazdin, 1977; McLaughlin, 1975;

McLaughlin & Williams, 1988; Naughton & McLaughlin, 1995; Williams,

et al., 1991). There have been some exceptions reported in the literature.

Broden, Hall, Dunlap, & Clark (1970) implemented a token program with a

class of junior high-school special education students. However, snacks were

used as a back-up reinforcer to increase attention to task, no direct measures of

academic responding were made and individual data were not presented in

detail. It may be that the withdrawal of snacks or the failure of the students'

next teacher to employ such a system would reduce the probability of maintenance of behavior change. In addition, the merits of using attending as a

measure of eectiveness has been questioned because it may not be related to

academic productivity or having students actively engaged in the curriculum

(Winett & Winkler, 1972).

Long & Williams (1973) and Stewart & McLaughlin (1986) investigated the

eect of a free-time contingency with inner-city junior high-school students. Free

time was shown to be an eective consequence to control disruptive and

attending behaviors. Individual data across sessions were not presented and,

again, no measures of academic responding were made. Strandy, McLaughlin, &

Hunsaker (1979) reported that free-time was an eective consequence to increase

assignment completion with six high school special education students. However, the results were mixed with two students and data collection was short in

duration (22 sessions). Inkster & McLaughlin (1993) successfully implemented a

token program employing access to computers as a consequence with an

adolescent male to increase his attendance at school.

Since very few applications of token programs have involved middle-school

students and few studies have evaluated the eect of bonus points on

# 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Behav. Intervent., Vol. 13, 1119 (1998)

Bonus contingencies

13

academic performance, the present report provided such an analysis. In

addition, the present research also examined the eects of increasing the magnitude of point contingencies within an ongoing token program in daily assignment in math.

METHOD

Participants and setting

The participants were four middle-school special education students enrolled

in the rst author's self-contained classroom. The ages of the students ranged

from 13 years 11 months to 14 years 11 months at the beginning of the experiments Scores on the Peabody Individual Achievement Test (Dunn & Markwardt,

1970) ranged from 3.5 to 6.5 grade equivalents for mathematics, reading

comprehension and spelling, when it was given one month subsequent to the

start of the investigation. For each of the participants, improving accuracy of

math performance was an objective listed on their Individualized Education

Programs (IEPs).

The classroom was managed by a token (point) economy (McLaughlin,

Swain, Brown, & Fielding, 1986). Briey, Students earned points for accuracy of

academic performance in math, spelling, English, social studies and reading.

Points also could be earned for assignment completion, on-task responding and

appropriate behavior in the hall. Points were lost (response cost) for behaviors

such as wasting time, playing with objects, incomplete assignments, not following directions, talk-outs, swearing, cheating etc. Points were exchanged in blocks

of 100 on an intermittent schedule, averaging ve days, for any of or a combination of four back-up reinforcers. Back up reinforcers consisted of (i) leaving

school 30 minutes early, (ii) playing table games, (iii) going to the resource

center, and (iv) free time. The classroom was staed by a certied teacher and a

half-time teaching assistant.

The dependent variable employed in the study was academic accuracy in math

class. Accuracy was calculated from individual workbook pages in the Spectrum

Mathematics Series (France & Clark, 1990). A correct math response was dened

as matching the answer key for the math workbook. The percent correct was

calculated by dividing the correct responses by the total number of possible

responses for the daily assignment. The teacher attempted to make the assignments of equal diculty and length, but some assignments were longer and more

dicult due to the curriculum employed in the school district.

A multiple-baseline design across students was used (Kazdin, 1982).

# 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Behav. Intervent., Vol. 13, 1119 (1998)

14

J. C. Swain and T. F. McLaughlin

Baseline

During the baseline condition, pupils received their math assignments were

allowed 55 min class time to complete two pages. Under the ongoing token

economy, a maximum of 20 points could be earned per assignment. The scale for

earning points was 100 to 95% 10 points, 94 to 86% 9 points, 85 to 75%

8 points, 74 to 66% 7 points, 65 to 55% 6 points and 54 to 0% 0 points.

Ten extra points also could be earned if the assignment was completed during the

55 min class period. This procedure was in eect for 1129 assignments.

Bonus contingency

In this condition, pupils could earn 50 bonus points contingent upon a score

of 80 percent or higher. Twenty additional bonus points could also be earned;

10 for assignment completion and 10 for neatness, totaling 70 points. This

condition was in eect for eight to 46 assignments.

Reliability of measurement

Reliability was assessed daily by having the teacher's aide, who was unaware

of the experimental conditions, check the pupil's daily math assignments prior to

being rechecked by the rst author. An agreement was dened as both graders

scoring a problem as either correct or in error. A disagreement was dened as the

graders failing to score the problem in the same manner. Two hundred

assignments were corrected with 100% agreement between graders.

RESULTS

The overall results indicated that accuracy in math increased under the bonus

contingency procedure compared with the baseline conditions. This eect was

replicated for each student. The overall percent correct for all four students

during baseline was 54% (range 2274%). With the commencement of the

bonus point contingency, the overall mean percent correct for all four students

increased (M 29%; range 2274%).

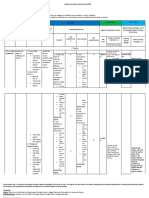

As shown in Figure 1, the rst student (S-1), who was transferred from the rst

author's classroom shortly after the bonus points were implemented, increased

his mean percent correct from 22% in baseline to 86% in the bonus contingency

# 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Behav. Intervent., Vol. 13, 1119 (1998)

Bonus contingencies

15

Figure 1. The percent correct in math for each student as a function of the experimental

conditions: Baselinetoken program with no bonus contingencies; Bonus Contingency

additional points awarded for 80% or greater accuracy in the ongoing token program.

# 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Behav. Intervent., Vol. 13, 1119 (1998)

16

J. C. Swain and T. F. McLaughlin

condition. Compared to baseline, this was an mean overall improvement of

391%.

The second student (S-2) increased his mean accuracy from 74% in baseline to

83% during bonus points. The third student (S-3) also improved his overall

mean accuracy from 61% in baseline to 82% in the bonus points condition. The

last student (S-4) had an overall mean performance of 61% during baseline

increased to 81% in the bonus contingency conditions (an increase of 20%).

During baseline there was a great deal of variability for students 1, 3, and 4

and there were several data points of zero or near zero. For students 2 through 4

there were downward trends in performance. When bonus points were added,

data for students 1, 3 and 4 showed an abrupt change in level and became more

stable (i.e. the range was narrower). These all indicated better control of math

accuracy with more consistent performance from assignment to assignment.

DISCUSSION

The present report replicated the positive eect of token reinforcement on

academic responding of middle-school students with behavior disorders. The use

of bonus points further enhanced the positive outcomes of the token program.

In addition, these gains in academic responding were replicated across all four

students. In the present research, data were collected for an extended period of

time (60 d). Eective measures involved academic responding (accuracy of

performance in math) with adolescent special education students. No data were

presented on assignment completion since it was high (100%) over the duration

of the experiment.

The use of individual data presentation revealed that some students improved

their performance in math more than others. The smaller gains by S-2 were made

more evident. Teachers interested in working with adolescent students with

behavior disorders may nd single-subject design an applicable evaluation procedure (Morgan & Jenson, 1988).

All of the pupils met the 80 percent criterion required to earn extra points.

Therefore, manipulation of the density of reinforcement may be an additional

procedure to employ to increase academic responding. The selection of academic

responding with an adolescent population was worthy of note. Most previous

studies have examined the eectiveness of token programs on disruptive or

attending behaviors (Broden et al., 1970; Long & Williams, 1973). Also, most

teachers provide some type of consequence for academic performance, and

increasing such a behavior should be of benet to students when mainstreaming

is considered. Most regular education teachers tend to respond positively to

# 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Behav. Intervent., Vol. 13, 1119 (1998)

Bonus contingencies

17

students who have enough academic skills to complete their work with accuracy

with minimal teacher assistance (Lewis, Wilson, & McLaughlin, 1993). Changes

in academic responding are more likely to maintain or generalize after the

termination of specialized intervention procedures (McLaughlin, 1979;

McLaughlin & Connis, 1991; Stokes & Osnes, 1988). The use of accuracy in

math as a dependent measure was employed to `trap' the behavior so it would be

maintained in other math classes (Morgan & Jenson, 1988). Such data would be

of interest as generalization of behavior continues to be an issue in behavioral

research (Rutherford & Nelson, 1988).

Student reactions gathered by the teacher through interviews and their anecdotal comments to the bonus points contingency were favorable. The students

enjoyed this procedure. The classroom teacher felt that such a procedure made

the management of the self-contained classroom easier.

Although the present research indicated that academic gains can be attained

using token reinforcement procedures with middle-school youth with behavior

disorders, countless academic dependent variables remain to examined. For

example, what are the eects of employing bonus points on performance in

social studies or in computer classes? This will have to be left to future research

and would no doubt be benecial to such students in the educational

community.

There was a great deal of variability in student performance. Several things

may have accounted for such a nding (e.g. loss of reinforcer eectiveness,

changes in math content and changes in diculty of the subject-matter materials

in math). It was our view that the major variable that aected the variability of

performance during the bonus point conditions was changes in the diculty of

the materials. We examined the math assignments in baseline as well as those

used in the bonus points phase and found that the work during baseline was

easier in terms of content. As the school year progressed, the material became

more dicult. However, the use of bonus points helped overcome some of these

changes in diculty.

Bonus points were only available in math. However, it was the view of the

classroom teacher that the use of bonus points was highly eective for math, but

did not adversely change student performance in social studies, reading, spelling

or science.

The number of published studies dealing with token economies has declined in

recent times (McLaughlin & Williams, 1988; Williams et al., 1991). The present

report provides additional support for the continued use and evaluation of token

reinforcement programs. The token economy can be an eective procedure to

assist students with behavior disorders in their academic skills. The addition of

bonus points can further enhance the eectiveness of token programs.

# 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Behav. Intervent., Vol. 13, 1119 (1998)

18

J. C. Swain and T. F. McLaughlin

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Preparation of this manuscript was in partial fulllment of the requirements for a

Masters of Education in Special Education in the Department of Education, School of

Education, Gonzaga University. A special note to thanks of Lamar Fielding, Principal,

for allowing this research in his school.

REFERENCES

Bolstad, O. D., & Johnson, S. M. (1972). Self-regulation in the modication of disruptive

behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 5, 433454.

Broden, M., Hall, R. V., Dunlap, A., & Clark, R. (1970). Eects of teaching attention and a token

reinforcement system in a junior high school special education class. Exceptional Children, 36,

341249.

Dunn, L., & Markwardt, F. (1970). Peabody Individual Achievement Test. Circle Pines, MN:

American Guidance Service.

France, N., & Clark, B. (1990). Spectrum Mathematics. Palo Alto, CA: Laidlaw.

Inkster, A., & McLaughlin, T. F. (1993). Token reinforcement: eects for reducing tardiness with

a socially disadvantage adolescent student. B. C. Journal of Special Education, 17, 176182.

Kazdin, A. E. (1977). The token economy: a review and evaluation. New York: Plenum.

Kazdin, A. E. (1982). Single case research designs: methods for clinical and applied settings.

New York: Oxford University Press.

Lewis, A., Wilson, S. M., & McLaughlin, T. F. (1993). A comparison of regular and special

education teachers practices for providing instruction. B. C. Journal of Special Education, 17,

221237.

Long, J. D., & Williams, R. L. (1973). The comparative eectiveness of group and individually

contingent free time with inner-city junior high school students. Journal of Applied Behavior

Analysis, 6, 465474.

McKensie, H. S., Clark, M., Wolf, M. M., Kothera, R., & Benson, C. (1969). Behavior modication of children with learning disabilities using grades as tokens and allowances as back-up

reinforcers. Exceptional Children, 34, 745752.

McLaughlin, T. F. (1975). The applicability of token reinforcement systems in public school

systems. Psychology in the Schools, 14, 8489.

McLaughlin, T. F. (1979). Generalization of treatment eects: an analysis of procedures and

outcomes. Corrective and Social Psychiatry, 25(2), 3338.

McLaughlin, T. F., & Connis, R. T. (1991). Generalization and analysis of behavior: an analysis.

Corrective and Social Psychiatry, 37(4), 5863.

McLaughlin, T. F., & Malaby, J. E. (1972). Intrinsic reinforcers in classroom token economy.

Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 5, 263270.

McLaughlin, T. F., Swain, J. C., Brown, M., & Fielding, L. (1986). The eects of academic

consequences on inappropriate social behavior of special education middle school students.

Techniques: A Journal of Remedial Education and Counseling, 2, 310316.

McLaughlin, T. F., & Williams, R. L. (1988). The token economy in the classroom. In J. C. Witt,

S. N. Elliott, & F. M. Gresham (Eds), Handbook of behavior therapy in education (pp. 469487).

New York: Plenum.

# 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Behav. Intervent., Vol. 13, 1119 (1998)

Bonus contingencies

19

Morgan, D., & Jenson, W. R. (1988). Teaching behaviorally disordered students: preferred

practices. Columbus, OH: Merrill.

Naughton, C., & McLaughlin, T. F. (1995). The use of a token economy system for students with

behavior disorders. B. C. Journal of Special Education, 19(2), 1938.

O'Leary, K. D., Becker, W. C. (1967). Behavior modication of an adjustment class: a token

reinforcement program. Exceptional Children, 33 637642.

O'Leary, K. D., & Becker, W. C., Evans, R., & Saudargas, R. A. (1969). A token reinforcement

program in a public school: a replication and systematic analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior

Analysis, 2, 313.

O'Leary, S. G., & O'Leary, K. D. (1976). Behavior modication in the school. In H. Leitenberg

(Ed.), Handbook of behavior modication and behavior therapy (pp. 475515). Englewood Clis,

NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Ringer, V. M. J. (1973). The use of a `token helper' in the management of classroom behavior

problems and in teacher training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 6, 671677.

Rutherford, R. B., & Nelson, C. M. (1988). Generalization and maintenance of treatment eects.

In J. C. Witt, S. N. Elliott, & F. M. Gresham (Eds), Handbook of behavior therapy in education

(pp. 277324). New York: Plenum.

Shook, S., LaBrie, M., Vallies, J., McLaughlin, T. F., & Williams, R. L. (1990). The eects of a

token program on rst grade student's inappropriate social behavior. Reading Improvement, 27,

96101.

Stewart, J. P., & McLaughlin, T. F. (1986). Eects of group and individual contingencies on

reading performance with Native American junior high school students. Techniques: A Journal

for Remedial Education and Counseling, 2, 133144

Stokes, T. F., & Osnes, P. G. (1988) The developing applied technology of generalization and

maintenance. In R. H. Horner, G. Dunlap, & R. Koegel (Eds), Generalization and maintenance

(pp. 519). Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

Strandy, C., McLaughlin, T. F., & Hunsaker, D. (1979). Free time as a reinforcer for assignment

completion with high school special education students. Education and Treatment of Children, 2,

271277.

Walker, H. M., Hops, H., & Feigenbaum, E. (1976). Deviant classroom behavior as a function of

combinations of social and token reinforcement and cost contingency. Behavior Therapy, 7,

7688.

Williams, B. F., Williams, R. L., & McLaughlin, T. F. (1991). Classroom procedures for

remediating behavior disorders. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 3, 349384.

Winett, R., & Winkler, R. C. (1972). Current behavior modication in the classroom: be still, be

quiet, be docile. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 5, 499504.

# 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Behav. Intervent., Vol. 13, 1119 (1998)

You might also like

- Journal of Statistics Education, V16n1 - Carmelita YDocument10 pagesJournal of Statistics Education, V16n1 - Carmelita YHerawati AffandiNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Manipulatives on the Performance of Mathematical Problems in Elementary School ChildrenFrom EverandThe Effect of Manipulatives on the Performance of Mathematical Problems in Elementary School ChildrenNo ratings yet

- Full TextDocument15 pagesFull Textflorie_belleNo ratings yet

- Action Research Proposal Final DraftDocument12 pagesAction Research Proposal Final Draftmonalinda gonzalesNo ratings yet

- RRLDocument12 pagesRRLVenz AndreiNo ratings yet

- Mathematical Problem Posing As A Measure of Curricular Effect On Students' LearningDocument13 pagesMathematical Problem Posing As A Measure of Curricular Effect On Students' LearningX YNo ratings yet

- The Impact on Algebra vs. Geometry of a Learner's Ability to Develop Reasoning SkillsFrom EverandThe Impact on Algebra vs. Geometry of a Learner's Ability to Develop Reasoning SkillsNo ratings yet

- A Comparison of Three Instructional Methods For Teaching Math Skills To Secondary Students With Emotional/Behavioral DisordersDocument15 pagesA Comparison of Three Instructional Methods For Teaching Math Skills To Secondary Students With Emotional/Behavioral DisordersNurul IzzaNo ratings yet

- 11 - Using Performance Assessment Proofreading Done PDFDocument21 pages11 - Using Performance Assessment Proofreading Done PDFAteng TrisnadiNo ratings yet

- The Problem and The Related LiteratureDocument25 pagesThe Problem and The Related LiteratureKister Quin EscanillaNo ratings yet

- Sample Research Ojastro, Et Al 2017-2018Document11 pagesSample Research Ojastro, Et Al 2017-2018hope lee oiraNo ratings yet

- Problems of Implementing Continuous Assessment in Primary Schools in NigeriaDocument7 pagesProblems of Implementing Continuous Assessment in Primary Schools in NigeriaShalini Naidu VadiveluNo ratings yet

- Edu-690 Action Research PaperDocument27 pagesEdu-690 Action Research Paperapi-240639978No ratings yet

- "Backwash Effects" of Testing On Learning MathematicsDocument24 pages"Backwash Effects" of Testing On Learning MathematicsAmadeus Fernando M. PagenteNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Teaching Mathematics Using Manipulative Instructional MaterialsDocument68 pagesEffectiveness of Teaching Mathematics Using Manipulative Instructional Materialsanne ghieNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document12 pagesChapter 1Rosa Mae BascarNo ratings yet

- Improving Multiplication and Division Automaticity in Elementary EducationDocument29 pagesImproving Multiplication and Division Automaticity in Elementary Educationapi-617517064No ratings yet

- Academic Performance of Grade VI Pupils in Mathematics Using Online and Modular InstructionDocument11 pagesAcademic Performance of Grade VI Pupils in Mathematics Using Online and Modular Instructionset netNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Family Background and SCH PDFDocument49 pagesThe Effects of Family Background and SCH PDFjefferson Acedera ChavezNo ratings yet

- 37 04 36Document8 pages37 04 36Himmatul UlyaNo ratings yet

- Improving Multiplication and Division Automaticity Using SplashlearnDocument17 pagesImproving Multiplication and Division Automaticity Using Splashlearnapi-617517064No ratings yet

- Research For AnnDocument102 pagesResearch For AnnNikka JaenNo ratings yet

- First Grade Teaching Math Fact Fluency Research ProjectDocument15 pagesFirst Grade Teaching Math Fact Fluency Research ProjectKali CoutourNo ratings yet

- Edited ResearchDocument12 pagesEdited ResearchRICHEL MANGMANGNo ratings yet

- Mabe Ar (2) For FinalDocument52 pagesMabe Ar (2) For FinalZaila Valerie BabantoNo ratings yet

- Cooperative Learning Approach and Students Attitude Towards MathematicsDocument13 pagesCooperative Learning Approach and Students Attitude Towards MathematicsRan RanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 11Document26 pagesChapter 11joy garciaNo ratings yet

- Research - Ashly GroupDocument14 pagesResearch - Ashly GroupRoselyn SalamatNo ratings yet

- TherioesDocument5 pagesTherioesKenneth TumlosNo ratings yet

- Teaching Methods Paper # 2 Self-Monitoring and Graphic Organizers Matt Drabenstott 12/03/2015 SEDP 601 Virginia Commonwealth UniversityDocument12 pagesTeaching Methods Paper # 2 Self-Monitoring and Graphic Organizers Matt Drabenstott 12/03/2015 SEDP 601 Virginia Commonwealth UniversityIvy RedadoNo ratings yet

- Research StudyDocument85 pagesResearch StudyDesiree Fae Alla100% (1)

- Comparing Math Success: Math Success Rate Between A Blending Learning Classroom and A Traditional Math ClassroomDocument17 pagesComparing Math Success: Math Success Rate Between A Blending Learning Classroom and A Traditional Math Classroomapi-324708628No ratings yet

- Thesis John Carlo Macaraeg SahayDocument26 pagesThesis John Carlo Macaraeg SahayCaloyNo ratings yet

- Research SynthesisDocument8 pagesResearch SynthesisMichelle NewNo ratings yet

- Cover, Copy and CompareDocument10 pagesCover, Copy and Compareedgar alirio insuastiNo ratings yet

- Teachers' Intervention in Improving Numeracy Skills of Grade 7 StudentsDocument9 pagesTeachers' Intervention in Improving Numeracy Skills of Grade 7 StudentsLuis SalengaNo ratings yet

- Action ResearchDocument30 pagesAction Researchgilda ocampoNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Pre-Recorded Lesson and Home Tutorial To The Academic Performance in Mathematics of Grade 11 StudentsDocument19 pagesThe Effect of Pre-Recorded Lesson and Home Tutorial To The Academic Performance in Mathematics of Grade 11 StudentsPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- EDITED RESEARCH For PublicationDocument11 pagesEDITED RESEARCH For PublicationRICHEL MANGMANGNo ratings yet

- Managing Classroom Behavior of Head Start Children Using Response Cost and Token Economy ProceduresDocument12 pagesManaging Classroom Behavior of Head Start Children Using Response Cost and Token Economy ProceduresJieNajihahNo ratings yet

- Flipped Classroom Model: Effects On Performance, Attitudes and Perceptions in High School AlgebraDocument13 pagesFlipped Classroom Model: Effects On Performance, Attitudes and Perceptions in High School Algebrasome oneNo ratings yet

- Assignment 5Document29 pagesAssignment 5RuStoryHuffmanNo ratings yet

- Metacognitive Strategies: Their Efffects To Academic Performance and EngagementDocument21 pagesMetacognitive Strategies: Their Efffects To Academic Performance and EngagementDerren Nierras Gaylo100% (1)

- A Model of Classroom Assessment in Action: Using Assessment To Improve Student Learning and Statistical ReasoningDocument4 pagesA Model of Classroom Assessment in Action: Using Assessment To Improve Student Learning and Statistical ReasoningAgi B BossNo ratings yet

- Synopsis of A Synthesis of Empirical Research On Teaching Mathematics To Low Achieving Students PDFDocument3 pagesSynopsis of A Synthesis of Empirical Research On Teaching Mathematics To Low Achieving Students PDFkaskaraitNo ratings yet

- Crisis Management ResearchDocument7 pagesCrisis Management Researchhong sikNo ratings yet

- On Line Assessment The Impact of Mode On Student PerformanceDocument16 pagesOn Line Assessment The Impact of Mode On Student PerformanceLuis SalengaNo ratings yet

- Chapters 1 3 Thesis SampleDocument20 pagesChapters 1 3 Thesis SampleRandy Lucena100% (3)

- RRL Nov 14Document4 pagesRRL Nov 14Nancy AtentarNo ratings yet

- Action Research Sample If ExperimentalDocument28 pagesAction Research Sample If ExperimentalLyn Gene Bartolome - FamisaranNo ratings yet

- School Counselors and CicoDocument10 pagesSchool Counselors and Cicoapi-249224383No ratings yet

- How The Time of Day Affects Productivity - Evidence From School SchedulesDocument12 pagesHow The Time of Day Affects Productivity - Evidence From School Schedulesnctneo .01No ratings yet

- Peer Tutorial Program: Its Effect On Grade Seven (7) Grades in MathemathicsDocument23 pagesPeer Tutorial Program: Its Effect On Grade Seven (7) Grades in Mathemathicsbryan p. berangelNo ratings yet

- Impact of Digital Technology To Academic Performance of Grade 11 Students in General MathematicsDocument9 pagesImpact of Digital Technology To Academic Performance of Grade 11 Students in General MathematicsFRANCISCO, Albert C.No ratings yet

- Learning Modalities Utilization Perceived Effectiveness and Academic Performance of Key Stage 2 LearnersDocument15 pagesLearning Modalities Utilization Perceived Effectiveness and Academic Performance of Key Stage 2 LearnersPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Among Grade 7 Students in Malobago Pagsang-An National High School."Document4 pagesAmong Grade 7 Students in Malobago Pagsang-An National High School."Corong RoemarNo ratings yet

- Concept Paper: by Nicholas O. Onim REG. NO.: I56/79879/2012Document24 pagesConcept Paper: by Nicholas O. Onim REG. NO.: I56/79879/2012Allan JoseNo ratings yet

- Todd Campbell Meyey Horner 2008Document11 pagesTodd Campbell Meyey Horner 2008api-252901326No ratings yet

- Course TasksssDocument8 pagesCourse TasksssJessa Valerio LacaoNo ratings yet

- Sample Thesis2Document25 pagesSample Thesis2Lemuel KimNo ratings yet

- (Micro) Fads Asset Evidence: FuturesDocument23 pages(Micro) Fads Asset Evidence: FuturesLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Factor Analysis of Spectroelectrochemical Reduction of FAD Reveals The P K of The Reduced State and The Reduction PathwayDocument9 pagesFactor Analysis of Spectroelectrochemical Reduction of FAD Reveals The P K of The Reduced State and The Reduction PathwayLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- A Homogenous Assay of FAD Using A Binding Between Apo-Glucose Oxidase and FAD Labeled Withan Electroactive CompoundDocument6 pagesA Homogenous Assay of FAD Using A Binding Between Apo-Glucose Oxidase and FAD Labeled Withan Electroactive CompoundLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Gepi 1370100621Document5 pagesGepi 1370100621Lata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Electrochemical and Catalytic Properties of The Adenine Coenzymes FAD and Coenzyme A On Pyrolytic Graphite ElectrodesDocument7 pagesElectrochemical and Catalytic Properties of The Adenine Coenzymes FAD and Coenzyme A On Pyrolytic Graphite ElectrodesLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- BF 01456737Document8 pagesBF 01456737Lata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Covalent Immobilization of and Glucose Oxidase On Carbon ElectrodesDocument5 pagesCovalent Immobilization of and Glucose Oxidase On Carbon ElectrodesLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Spectroscopic Study of Intermolecular Complexes Between FAD and Some Fl-Carboline DerivativesDocument5 pagesSpectroscopic Study of Intermolecular Complexes Between FAD and Some Fl-Carboline DerivativesLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Fid, Fads: If Cordorate Governance Is A We Need MoreDocument1 pageFid, Fads: If Cordorate Governance Is A We Need MoreLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Infrared Spectroscopic Study of Thermally Treated LigninDocument4 pagesInfrared Spectroscopic Study of Thermally Treated LigninLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- BF 00314252Document2 pagesBF 00314252Lata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Apj 526Document7 pagesApj 526Lata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Task Group Osition Paper On Unbiased Assessment of CulturallyDocument5 pagesTask Group Osition Paper On Unbiased Assessment of CulturallyLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Production of Recombinant Cholesterol Oxidase Containing Covalently Bound FAD in Escherichia ColiDocument10 pagesProduction of Recombinant Cholesterol Oxidase Containing Covalently Bound FAD in Escherichia ColiLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Editorial: Etiology Nutritional Fads: WilliamDocument4 pagesEditorial: Etiology Nutritional Fads: WilliamLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Spectroscopic Study of Molecular Associations Between Flavins FAD and RFN and Some Indole DerivativesDocument6 pagesSpectroscopic Study of Molecular Associations Between Flavins FAD and RFN and Some Indole DerivativesLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Amperometric Assay Based On An Apoenzyme Signal Amplified Using NADH For The Detection of FADDocument4 pagesAmperometric Assay Based On An Apoenzyme Signal Amplified Using NADH For The Detection of FADLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Integrated Project Development Teams: Another F A D - ., or A Permanent ChangeDocument6 pagesIntegrated Project Development Teams: Another F A D - ., or A Permanent ChangeLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- A Rapid Micromethod For Determination of FMN and FAD in MixturesDocument5 pagesA Rapid Micromethod For Determination of FMN and FAD in MixturesLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- FAD Used As A Mediator in The Electron Transfer Between Platinum and Several BiomoleculesDocument11 pagesFAD Used As A Mediator in The Electron Transfer Between Platinum and Several BiomoleculesLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- A Defense of Popular Culture: Brustein, Munson, Rothstein, Simon, Nichols, Kimball, and Pinsker 73Document6 pagesA Defense of Popular Culture: Brustein, Munson, Rothstein, Simon, Nichols, Kimball, and Pinsker 73Lata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Contrasting Zones of Comfortable Competence: Popular Culture in A Phonics LessonDocument15 pagesContrasting Zones of Comfortable Competence: Popular Culture in A Phonics LessonLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Sce 20287Document3 pagesSce 20287Lata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Spectroscopic Study of The Molecular Structure of A Lignin-Polymer SystemDocument5 pagesSpectroscopic Study of The Molecular Structure of A Lignin-Polymer SystemLata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Raman Scattering in Tellurium-Metal Oxyde Glasses: Journal of Molecular Structure 349 (1995) 413-416Document4 pagesRaman Scattering in Tellurium-Metal Oxyde Glasses: Journal of Molecular Structure 349 (1995) 413-416Lata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- J Religion 2003 11 003Document2 pagesJ Religion 2003 11 003Lata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- DOI 10.1007/s12138-009-0064-z: © Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2008Document5 pagesDOI 10.1007/s12138-009-0064-z: © Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2008Lata DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Tag Questions: Grammar Practice WorksheetsDocument11 pagesTag Questions: Grammar Practice WorksheetsNorma Constanza Ramírez Quino67% (3)

- Bright Ideas 2 Evaluation MaterialDocument45 pagesBright Ideas 2 Evaluation MaterialЕкатерина Михальченко100% (2)

- English Learning Through TamilDocument3 pagesEnglish Learning Through Tamilkrishna chaitanya100% (1)

- Website Design of Job Description Based On Isco-08 and Calculation of Employee Total Needs Based On Work LoadDocument10 pagesWebsite Design of Job Description Based On Isco-08 and Calculation of Employee Total Needs Based On Work LoadAgra AdiyasaNo ratings yet

- Standard: Capstone Project Scoring RubricDocument1 pageStandard: Capstone Project Scoring Rubricapi-546285745No ratings yet

- CChikun - Encyclopedia of Life and Death - Elementary - 04Document115 pagesCChikun - Encyclopedia of Life and Death - Elementary - 04kooka_k100% (1)

- SCHOLTEN J. Homoeopathy and MineralsDocument193 pagesSCHOLTEN J. Homoeopathy and Mineralsrodriguezchavez197567% (3)

- Approaches To Strategic Decision Making, Phases inDocument22 pagesApproaches To Strategic Decision Making, Phases inShamseena Ebrahimkutty50% (8)

- Lesson Plan 5 SpeakingDocument3 pagesLesson Plan 5 SpeakingRian aubrey LauzonNo ratings yet

- Ucu 110 Project GuidelinesDocument5 pagesUcu 110 Project GuidelinesvivianNo ratings yet

- D Nunan 2003 The Impact of English As A Global Language On Educational Policies and Practices in The Asia ) Pacific Region PDFDocument26 pagesD Nunan 2003 The Impact of English As A Global Language On Educational Policies and Practices in The Asia ) Pacific Region PDFkayta2012100% (2)

- Research Misconduct As White-Collar Crime - A Criminological Approach (PDFDrive)Document267 pagesResearch Misconduct As White-Collar Crime - A Criminological Approach (PDFDrive)Ambeswar PhukonNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan TLE / ICT - Entrepreneurship 6Document2 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan TLE / ICT - Entrepreneurship 6Reyjie VelascoNo ratings yet

- PGDT Clasroom Eng.Document107 pagesPGDT Clasroom Eng.Dinaol D Ayana100% (2)

- Organizational Behavior: Robbins & JudgeDocument18 pagesOrganizational Behavior: Robbins & JudgeYandex PrithuNo ratings yet

- SLM G12 Week 4 The Human Person and DeathDocument13 pagesSLM G12 Week 4 The Human Person and DeathMarcelino Halili IIINo ratings yet

- Jurnal Penggunaan Bahasa Daerah Pada Komunikasi Mahasiswa Di KampusDocument14 pagesJurnal Penggunaan Bahasa Daerah Pada Komunikasi Mahasiswa Di KampusHilman RamayadiNo ratings yet

- Most 50 Important Interview QuestionsDocument6 pagesMost 50 Important Interview Questionsengjuve0% (1)

- What Is Strategic ManagementDocument10 pagesWhat Is Strategic ManagementREILENE ALAGASINo ratings yet

- Presentations For CLILs For ClilDocument11 pagesPresentations For CLILs For ClilAngela J MurilloNo ratings yet

- Maam BDocument2 pagesMaam BCristine joy OligoNo ratings yet

- OB Session Plan - 2023Document6 pagesOB Session Plan - 2023Rakesh BiswalNo ratings yet

- Emotion DetectionDocument17 pagesEmotion Detectionhet patelNo ratings yet

- Rpms GuidelinesDocument53 pagesRpms GuidelinesNELLY L. ANONUEVONo ratings yet

- Language Curriculum For Secondary Schools Syllabus (OBE)Document4 pagesLanguage Curriculum For Secondary Schools Syllabus (OBE)Bhenz94% (16)

- A Translanguaging Pedagogy For Writing A CUNY-NYSIEB Guide For Educators ArquivoDocument119 pagesA Translanguaging Pedagogy For Writing A CUNY-NYSIEB Guide For Educators ArquivoMariana HungriaNo ratings yet

- TOS Grades 1-3 FinalDocument46 pagesTOS Grades 1-3 FinalRadcliffe Lim Montecillo BaclaanNo ratings yet

- Science Lesson Observation FormDocument2 pagesScience Lesson Observation Formapi-381012918No ratings yet

- Largo, Johara D. FIDPDocument4 pagesLargo, Johara D. FIDPJohara LargoNo ratings yet

- YES-O Accomplishment Report - Sept. 2016Document5 pagesYES-O Accomplishment Report - Sept. 2016Esmeralda De Vera LozanoNo ratings yet