Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Braganza2011 PDF

Uploaded by

Amirullah AbdiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Braganza2011 PDF

Uploaded by

Amirullah AbdiCopyright:

Available Formats

Seminar

Chronic pancreatitis

Joan M Braganza, Stephen H Lee, Rory F McCloy, Michael J McMahon

Lancet 2011; 377: 1184–97 Chronic pancreatitis is a progressive fibroinflammatory disease that exists in large-duct (often with intraductal

Published Online calculi) or small-duct form. In many patients this disease results from a complex mix of environmental (eg, alcohol,

March 11, 2011 cigarettes, and occupational chemicals) and genetic factors (eg, mutation in a trypsin-controlling gene or the cystic

DOI:10.1016/S0140-

fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator); a few patients have hereditary or autoimmune disease. Pain in

6736(10)61852-1

the form of recurrent attacks of pancreatitis (representing paralysis of apical exocytosis in acinar cells) or constant

Department of

Gastroenterology

and disabling pain is usually the main symptom. Management of the pain is mainly empirical, involving potent

(J M Braganza DSc) and analgesics, duct drainage by endoscopic or surgical means, and partial or total pancreatectomy. However, steroids

Department of Radiology rapidly reduce symptoms in patients with autoimmune pancreatitis, and micronutrient therapy to correct

(S H Lee FRCR), Manchester

electrophilic stress is emerging as a promising treatment in the other patients. Steatorrhoea, diabetes, local

Royal Infirmary, Manchester,

UK; Department of Education, complications, and psychosocial issues associated with the disease are additional therapeutic challenges.

Lancashire Teaching Hospitals,

Preston, UK (R F McCloy FRCS); Introduction Definition

and University of Leeds and

Chronic pancreatitis is a progressive inflammatory Traditionally, chronic pancreatitis has been classed as

Nuffield Hospital, Leeds, UK

(Prof M J McMahon FRCS) disorder in which pancreatic secretory parenchyma is fundamentally different from acute pancreatitis—the

Correspondence to:

destroyed and replaced by fibrous tissue, eventually latter is usually characterised by restoration of normal

Dr Joan M Braganza, leading to malnutrition and diabetes. Two forms are pancreatic histology after full clinical recovery.1 However,

c/o Mrs Jenny Parr, recognised—a large-duct calcifying type1 and a small-duct acute, recurrent acute, and chronic pancreatitis are now

Core Technology Facility,

variant.2–4 The disease is uncommon in Europe and the regarded as a disease continuum.9,10 There are several

3rd Floor, Grafton Street,

Manchester M13 9NT, UK USA; its prevalence in France is 26 per 100 000 people.5 reasons for this change: recurrent acute pancreatitis can

jenny.parr@manchester.ac.uk This prevalence is not dissimilar to the middle of three develop into chronic pancreatitis;10–12 there is an overlap

estimates from Japan,6,7 but considerably lower than the in causative factors, both genetic and environmental;10,13

figure of 114–200 per 100 000 in south India.7 experimental protocols can be modified to induce each

The main symptom of chronic pancreatitis is usually condition;14 and the pancreatitis attack is stereotyped—

pain, which occurs as attacks that mimic acute pancrea- patients have severe abdominal pain and increased blood

titis or as constant and disabling pain. Despite decades of amylase, lipase, and trypsinogen.

research, treatment of chronic pancreatitis remains

mostly empirical, and thus patients are repeatedly Pathophysiology and pathology

admitted to hospital and have interventional procedures, Experimental studies since the 1950s have shown that an

which strains medical resources.8 This absence of attack of pancreatitis begins as pancreastasis,13 prevention

progress in treatment is a sign of uncertainty about how of apical exocytosis in the pancreatic acinar cell (figure 1).15

the identified causative factors lead to the disease. The acinar cell quickly releases newly synthesised enzyme

Therefore, in this Seminar we focus on the patho- via the basolateral membrane into lymphatics, by way of

physiology and pathology of chronic pancreatitis before the interstitium, and directly into the bloodstream.16 Some

describing clinical management. zymogen granules also release their stored enzyme

basolaterally.15 These events result in inflammation.17

Findings from prospective clinical studies concur with

Search strategy and selection criteria this pancreastasis–pancreatitis sequence.13,17

We searched PubMed and the Cochrane library (to August, Experimental work has pinpointed a burst of reactive

2010) for reviews on chronic pancreatitis. We used Google oxygen species (ROS) as the trigger of so-called

scholar for specific searches, with “chronic pancreatitis” as the pancreastasis18 and as the potentiator of inflammation by

key phrase combined with “epidemiology”, “pathology”, activating signalling cascades that convert the damaged

“aetiology”, “gene mutations”, “pathogenesis”, acinar cell into a factory for chemokines and cytokines.19,20

“classification”, “diagnosis”, “pancreatic function tests”, ROS serve several physiological roles, including in signal

“pancreatic imaging tests”, “treatment of pain”, “pancreatic transduction,13,21 but an excess of ROS compared with

enzyme therapy”, “micronutrient therapy”, “antioxidant antioxidant capacity (electrophilic stress) is potentially very

therapy”, “endoscopic treatment”, or “surgical treatment”. We damaging. The exocytosis blockade seems to be caused by

selected the most up-to-date articles but did not disregard disruption of the methionine trans-sulphuration pathway

commonly referenced older publications. We also examined that produces essential methyl and thiol (principally

the reference lists of identified papers and selected those that glutathione) moieties.17,22 This problem also occurs in

we judged to be relevant. Review articles and book chapters clinical acute or acute-on-chronic pancreatitis.23–25

are cited to give readers more details and references than this In patients who develop large-duct chronic pancreatitis,

Seminar can accommodate. studies in the quiescent phase of the disease show that

the composition of pancreatic fluid changes in a manner

1184 www.thelancet.com Vol 377 April 2, 2011

Seminar

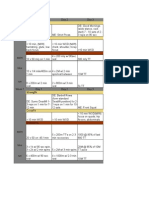

Normal Pancreastasis Pancreatitis

Constitutive

E pathways PAP/regIII

PSP/reg

ZG ZG ZG D

L ZG-L ZG-L

GC GC

RER RER ZG RER

Ph-elastase

Ph-PLA2

Nucleus Nucleus Nucleus

Constitutive MO

pathway

E

E E

MC PMN

Foci of gland digestion

Figure 1: Schematic representation of disturbances in the pancreatic acinar cell during experimental acute pancreatitis

See text for a full description. The constitutive pathway at the basolateral pole normally transports a small fraction of newly synthesised enzyme, as do two pathways at the

apical pole. E=amylase, lipase, trypsinogen, and other precursor proteases, and pro-phospholipase A2. RER=rough endoplasmic reticulum. GC=Golgi complex. ZG=zymogen

granules. L=lysosomes. ZG-L=miniscule fraction of zymogens activated by co-localisation with lysosomal enzymes. D=centripetal dissolution of granules.

PAP/regIII=pancreatitis associated protein. PSP/reg=pancreatic stone protein/islet regenerating protein. MC=mast cell. PMN=polymorphonuclear cell. MO=monocyte.

Ph-PLA2=phospholipase A2 from phagocytes and mast cell. Adapted from Braganza.13

that, for uncertain reasons, facilitates protein deposits— fibrosis.11 Nerves show breaching of the perineurium

the precursors to calcium carbonate stones.1 (1) There is adjacent to inflammatory foci, while the expression of

an early increase in secretion of enzyme and calcium, but nociceptive chemicals in nerve endings is increased.36

a decrease in the serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 1 Immunocytochemistry gives valuable insights into the

(SPINK 1), bicarbonate, and citrate.1 (2) Concentrations of development of chronic pancreatitis. Acinar cells,

free radical oxidation products are raised in the pancreatic which are hyperplastic at disease outset,2 show

fluid,26 which suggests ongoing electrophilic stress, and strong expression of cytochrome P450 (CYP) mono-

in an apparent attempt to compensate, concentrations of oxygenases,37–39 as do proliferated islets of Langerhans,37–39

the natural antioxidants27 lactoferrin and mucin are and hepatocytes (figure 2).37,38 After birth, CYP enzymes

increased.1,2,28 (3) Concentrations are altered of two are mainly located in the liver. CYP metabolises

secretory stress proteins29 (increased concentration of environmental lipophilic chemicals (xenobiotics). In the

pancreatitis associated protein [PAP]/regIII, which is first phase, the enzyme uses ROS to hydroxylate the

activated by electrophilic stress; and variable concentration substrate, which then usually undergoes second-phase

of pancreatic stone protein [PSP]/reg, formerly called conjugation reactions, often with glutathione and

lithostatin;1 figure 1) that tend to form fibrous lattices catalysed by glutathione transferases. So-called enzyme

upon partial digestion by trypsin. (4) There is an increase induction might be accompanied by expansion of the

of GP-2, which is a secreted component of zymogen endoplasmic reticulum so that, at least initially, the cell

granule membranes (analogous to the renal cast protein).30 secretes more of its normal products. However, this

(5) Concentrations of lysosomal enzymes are increased in defence reaction backfires if first-phase processing (eg, by

ductal fluid, and traces of trypsin appear.31 Moreover, the CYP2E1, CYP1A, and CYP3A1 isoforms) produces a

methionine metabolic pathway remains fractured.32–34 reactive xenobiotic metabolite. Cell injury depends on

On histology, the defining triad of stable disease whether or not there is enough by way of defences to

(irrespective of main causes or location)35 is acinar loss, ROS and reactive xenobiotic species: antioxidant enzymes

mononuclear cell infiltration, and fibrosis. The early (including the selenium-dependent glutathione peroxi-

lesions are distributed in patches; thus, normal findings dase), glutathione transferases, glutathione, and ascorbic

on needle biopsy are unreliable. An unusual form of so- acid (the bioactive form of vitamin C, which can substitute

called groove (paraduodenal) pancreatitis has been for glutathione).32,40 Immunochemistry shows that these

identified.11 Each inflammatory attack can cause foci of defence mechanisms are insufficient to meet the

fat necrosis that seem to lead to both pseudocysts and increased oxidant load in acinar cells,32,37 which therefore

www.thelancet.com Vol 377 April 2, 2011 1185

Seminar

show signs of electrophilic stress, such as excess lipo- progression resembles that from chronic active hepatitis

fuscin and cytoplasmic microvesiculation.41 to liver cirrhosis.2,12,47

Fibrosis is a sign that interstitial stellate cells are The table summarises the histological features of

activated in chronic pancreatitis; these cells play a ordinary chronic pancreatitis compared with features of

central part in disease progression by regulating the three variants in which the lesions are diffuse. The

synthesis and degradation of extracellular matrix pancreatic lesion in cystic fibrosis is a diffuse form of

proteins.42,43 Findings from histochemistry suggest a chronic pancreatitis wherein inflammatory stigmata

causal influence of two factors—an increase in lipid disappear by birth,48 except in patients with mild

peroxidation products caused by an excess of ROS in mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane

adjacent acini,44 and the release of mast cell conductance regulator gene (CFTR), who might have

degranulation products,45 transforming growth factor β1 recurrent attacks.49 Uniform lesions also occur upstream

in particular.46 The two factors are linked in that ROS of an obstructed duct1,11,48 and in autoimmune

and their oxidation products are natural activators of pancreatitis.50,51 The latter can involve the whole or part

mast cells.17 Activation of stellate cells is increased by of the gland and has two subtypes. Characteristics of

cytokines from infiltrating leucocytes and the injured the more common type-1 autoimmune pancreatitis are

acinar cell.43 The end stage of chronic pancreatitis is a dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with predominantly

identified by loss of all secretory tissue, disappearance IgG4+ cells, periductal swirling sclerosis, and obliterative

of inflammatory cells, and intense fibrosis. This venulitis. In the type-2, duct-destructive form, hordes

A B

D

H

H

D A

S

A

D

50 μm 50 μm

Figure 2: Immunolocalisation of cytochrome P4503A1 in surgical material from a 27-year-old woman with calcific chronic pancreatitis

The patient drank little alcohol, smoked 40 cigarettes a day, and worked as a forecourt attendant at a car and lorry-fuelling station. (A) The pancreatectomy fragment

shows that the enzyme (brown stain) is strongly expressed in acinar cells (A) but absent from epithelium of dilated ducts (D) or expanded stroma (S). (B) The needle

biopsy fragment of the liver showed that the enzyme is strongly expressed across the liver lobule (H) and weakly expressed in bile duct epithelium (D). Reproduced

with permission from Foster et al.37

Ordinary* Cystic fibrosis† Obstructive‡ Autoimmune§

Lesions

Distribution Patchy Diffuse Diffuse Diffuse

Extent of gland Variable Total Total Total or focal

Duct system

Main duct Irregularly dilated Minimally dilated Smoothly dilated Constricted

Protein plugs All ducts Intralobular and interlobular No No

Calcifying tendency Yes No No No

Epithelium destroyed (Groove form) No No Yes (type 2)

Neutrophils No No No Yes (type 2)

Inflammatory cells Mononuclear No No Plasmalymphacytic

Fibrosis Mainly perilobular Perilobular, intralobular Perilobular, intralobular Perilobular, intralobular, periductal

Pseudocyst Frequent No No No

*Excludes the small-duct variant (as in at least 30% of cases) wherein characteristic features are focal acinar cell damage and tubular complexes.3 Groove pancreatitis is similar

to the ordinary form, except for prominent destruction of ductal epithelium and cysts.1,11 †The earliest lesions occur in utero.48 ‡Diffuse lesions occur upstream from the

obstruction.1,11 §See text for subtypes.

Table: Main histological features of chronic pancreatitis subtypes (at diagnosis in stable disease)

1186 www.thelancet.com Vol 377 April 2, 2011

Seminar

of neutrophils infiltrate the wall of the duct, accompanied

by lymphocytes and plasma cells.51 Panel 1: Causative factors

Toxic

Causes Xenobiotics

Panel 1 lists causative factors of chronic pancreatitis. In • Alcohol

adults, excluding those with cystic fibrosis, 90–95% of • Cigarette smoke

patients are regarded as having alcoholic or idiopathic • Occupational volatile hydrocarbons

disease. Infective causes are rare.52 The connection between • Drugs: valproate, phenacitin, thiazide, oestrogen,

chronic pancreatitis and drugs (eg, valproate) is mostly and azathioprine

anecdotal. Studies from Italy,53 China, and Japan54 report

Endogenous

an association with gallstones in about 30% of patients.

• Hypercalcaemia, hyperparathyroidism

• Hyperlipidaemia, lipoprotein lipase deficiency

Alcoholic

• Chronic renal failure

Alcohol has long been regarded as the leading cause of

chronic pancreatitis in Europe, the USA, Brazil, Mexico, Infection or infestation

and South Africa, and is now regarded as the main cause • HIV, mumps virus, coxsackie virus

of the disease also in Australia and South Korea.7 • Echinococcus, Cryptosporidium

However, excess alcohol was the predominant factor in Genetic*

only 34% of cases of chronic pancreatitis in a recent • CFTR mutation

multicentre study from Italy53 and in 44% of cases in an • PRSS1 mutation

audit from the USA,55 with another study reporting that • SPINK1 mutation

African-Americans are at particular risk.56 Whether these

new data reflect differences in the definition of alcoholic Obstruction of main pancreatic duct

disease55 or a genuine change in the cause of chronic • Cancer

pancreatitis is not clear.57 • Post-traumatic scarring

Experimental studies have shown that, although the • Post-duct destruction in severe attack

pancreas processes ethanol efficiently (via a non-oxidative Recurrent acute pancreatitis

route that produces fatty acid ethyl esters, and by

oxidation via the acetaldehyde pathway), its metabolites Autoimmune

injure acinar cells and activate stellate cells in vitro.42,58

Miscellaneous

However, prolonged ethanol feeding does not induce

• Gall stones

chronic pancreatitis.58,59 Hence, the finding of a latent

• After transplant

interval of 15 years or more in patients who consumed

• After irradiation

150 g or more of ethanol per day—as most recently noted

• Vascular disease

in India60—is unsurprising. Moreover, less than 10% of

people who drink alcohol in excess develop the disease.61 Idiopathic

Collectively, these findings suggest that other factors • Early or late onset

interact to amplify ethanol toxicity in vivo. • Tropical

In animal models, small doses of ethanol induce

CFTR=cystic fibrosis transmenbrane conductance regulator. PRSS1=protease serine

CYP2E1, thus increasing the toxicity from other chemicals cationic trypsinogen. SPINK1=serine protease inhibitor Kazal. *Other, less common

to which the animal is simultaneously exposed.62,63 These mutations have been described.

results might rationalise the old observation that there is

no threshold for the pancreatic toxicity of ethanol,1 but

recent data suggest there is a threshold at 60 g per day.55 (manioc) were implicated. The classic description of

Moreover, CYP2E1 is the main pathway that metabolises tropical pancreatitis was from Kerala, south India;66

ethanol upon chronic excessive ingestion,63 but this however, hospital admission statistics revealed a decline

pathway releases ROS.64 in the disease by six times between 1962 and 1987,66

without a change in cassava consumption. Instead, the

Idiopathic decline coincided with the introduction of electricity in

60–70% of cases of chronic pancreatitis in India and this province, which removed the dependence on

China are labelled as idiopathic, as are around half the traditional lighting (see below). At present, tropical

cases in Japan.7 Tropical pancreatitis is a form of pancreatitis accounts for just 3·8 % of cases of chronic

idiopathic pancreatitis that affects young people and pancreatitis in India.60

has a propensity to diabetes and large calculi.65 This

disease is mainly reported in developing countries of Other toxic causes

Asia, Africa, and Central America, where severe Cigarette smoke has emerged as a strong independent

malnutrition and cyanogenic glycosides in cassava risk factor for chronic pancreatitis;55,67 the link was verified

www.thelancet.com Vol 377 April 2, 2011 1187

Seminar

by inhalation toxicology experiments.68,69 A case-control Idiopathic chronic pancreatitis is associated with a

study from the UK identified occupational volatile mutation in the CFTR gene.80,82,83 Patients can have one

hydrocarbons as another independent risk factor.70 This abnormal recessive allele, but possession of two confers

connection is upheld by descriptive studies from Chennai, a 40 times increased risk of developing idiopathic chronic

India,71 and Soweto, South Africa,72 which also reported pancreatitis, which rises to 500 times in patients who

regular contact with kerosene or paraffin, respectively, in also have a SPINK1 mutation.83 Some patients with

cookers, heaters, or lamps in patients with chronic apparent idiopathic chronic pancreatitis who have CFTR

pancreatitis (potentially relevant to Kerala, see above). mutations have an atypical form of cystic fibrosis.80 Three

Toxic damage to the pancreas by petrochemicals has been overlooked aspects of CFTR function have been reviewed

documented in lower vertebrates.40 Moreover, the simplest recently.32 CFTR is present in the luminal pole of acinar

animal model of chronic pancreatitis, which develops via cells where it might facilitate membrane recycling and

an acute phase, involves just one parenteral injection of exocytosis, like it does elsewhere. CFTR transports

dibutyltin (which has many industrial uses) and the injury bicarbonate and glutathione—which facilitate the

is amplified by alcohol.73 solubility of mucins in secretions—across the luminal

All these findings reinforce the pathological evidence membrane of ductal cells adjacent to the centroacinar

(figure 2) that the pancreas is a versatile but also space. CFTR is inactivated by electrophilic stress but is

vulnerable xenobiotic-metabolising organ.40 Inhaled protected by thiols and ascorbic acid. Moreover, CFTR is

xenobiotics that survive the pulmonary circulation would mislocalised to the cytoplasm of ductal cells in patients

pose the biggest threat (figure 2A) by striking the with chronic pancreatitis; this misplacement is corrected

pancreas directly via its rich arterial supply. in autoimmune disease by steroids, which also reduce

inflammation, restore bicarbonate and enzyme secretion,

Autoimmune and regenerate acinar cells.84

Autoimmune pancreatitis (2–4% of cases57) can be part Mutations in CFTR and SPINK1 have also been

of a multisystem disease (type 1) or can affect the described in patients with hypertriglyceridaemia or

pancreas alone (type 2).50,51 Aberrant human leucocyte hyperparathyroidism who develop pancreatitis.32 At

antigen DR-1 expression on pancreatic ductal cells present, molecular deficits that contribute to chronic

might present autoantigens to lymphocytes. Proposed pancreatitis have been identified in less than 10% of

pancreas-specific antigens include lactoferrin,28 carbonic alcoholic chronic pancreatitis and around 50% of

anhydrase, SPINK1, and a peptide that is present in cases overall.79

acinar cells that has homology to aminoacid sequences

in the plasminogen-binding protein of Helicobacter pylori74 Pathogenesis

(which might represent molecular mimicry)51 and also There is no agreement as to how these diverse causative

in ubiquitin–protein ligase74 (a cofactor for steroid factors lead to chronic pancreatitis. There are many

hormone receptors and an important peptide in the hypotheses about the pathogenesis of the disease,43 which

intracellular protein degradation pathway).75 fall into five main categories.

Genetic Ductal theory

Normally, if trypsinogen becomes prematurely activated One hypothesis suggests that ducts are the primary target

within the pancreas, it is inhibited by SPINK1 and then of the disease: theories centre on the primacy of calcifying

self-destructs or is degraded by trypsin-activated pro- protein deposits (protein plug hypothesis),1 stagnation of

teases;31 the potent inhibitor gluthathione is available if pancreatic juice, reflux of noxious bile and duodenal juice

all else fails.76 Hereditary pancreatitis is a rare condition (facilitated by passage of gallstones), and primary auto-

that is caused by a gain-of-function mutation (autosomal immune attack.

dominant, 80% penetrance) in the cationic trypsinogen

gene (PRSS1),9,10,42 which produces a degradation- Acinar theory

resistant form of trypsin.77 A transgenic mouse model Another hypothesis suggests that acini are the primary

of chronic pancreatic injury has proved this link.78 The target: alcohol is thought to injure acinar cells directly

PRSS1 mutation is not associated with alcoholic or (toxic metabolite hypothesis) or by increasing the cell’s

tropical chronic pancreatitis.79 By contrast, a loss-of- sensitivity to cholecystokinin (CCK) or via CYP2E1, while

function mutation in SPINK1 is strongly associated also activating stellate cells, especially in the presence of

with idiopathic disease79–82 but is thought to be a endotoxin.42,58 Another suggestion is that the disease is

predisposing or modifying factor rather than being caused by cyanide toxicity of the pancreas.

directly causative.42,79,80 Mutations in other genes that

could increase the threat from trypsin have also been Two-hits theory

described,79 as has a loss-of-function mutation in the Two so-called hits are additionally suggested as causing

PRSS2 gene (encoding anionic trypsinogen), which the disease: variations include a duct-to-acinar sequence,

protects against pancreatitis.79,80 vice versa, or double acinar hits. The last of these is the

1188 www.thelancet.com Vol 377 April 2, 2011

Seminar

most popular theory and incorporates the idea that constant pain; symptoms and signs of local complications

recurrent necrosis leads to periductal fibrosis.11 The first of the disease (eg, pseudocyst, obstruction of adjacent

attack of pancreatitis is taken to represent autodigestion organs, or vascular thrombosis); or complaints that suggest

caused by unregulated trypsin activity in the acinar cell. If exocrine or endocrine pancreatic failure, or both, by which

this attack is severe enough to recruit macrophages stage pancreatic calculi are often present. These features

(sentinel acute pancreatitis event hypothesis), subsequent form the basis for the most recent classification system

damage to the gland (by alcohol or electrophilic stress) (figure 3).47 In alcoholic disease, the interval from first

leads to fibrosis via macrophage-primed stellate cells. attack to steatorrhoea (signifying >95% loss of acini) is

around 13 years, which is substantially shorter than in

Electrophilic stress theory early-onset idiopathic disease12,86 or hereditary pancreatitis

The electrophilic stress theory is the pancreatic equivalent (≥26 years).12 Pancreatic calculi appear earliest in tropical

of paracetamol or carbon tetrachloride hepatotoxicity, pancreatitis,65 and earlier in alcoholic than idiopathic

which results from insufficient protection by glutathione disease.86 Diabetes might precede, begin at the same time

against electrophilic attack (via CYP) on key as, or start after steatorrhoea.65,88

macromolecules—not least, enzymes in the methionine Pain is the over-riding symptom in all but 10–15% of

trans-sulphuration pathway towards glutathione. How- cases of chronic pancreatitis; these cases are usually elderly

ever, in chronic pancreatitis electrophilic stress from patients with idiopathic disease12,86 or patients with

toxic metabolites—and, thereby, recurrent pancrea- autoimmune pancreatitis who might present with

stasis—develops over many years as a result of repetitive steatorrhoea, diabetes, or jaundice.50,51 The pain is wearying

exposures to multiple xenobiotics.41 Previous dietary and occurs in episodes that last about 1 week, or is constant.

insufficiency of micronutrients, especially methionine It starts in the epigastrium and moves through to the dorsal

and ascorbic acid, facilitates the problem.41,85 The diversion spine or localises to the left hypochondrium, radiating to

of free radical oxidation products into the interstitium the left infrascapular region. The pain is sometimes

causes mast cells to degranulate, leading to inflammation, associated with nausea and vomiting and can be partially

activation of nociceptive axon reflexes, and fibrosis.41 The eased by sitting up and leaning forward or by application of

realisation that compromised availability of methyl and local heat or other counterirritants to the dorsal spine or

thiol (glutathione) moieties underlies chronic pancreatitis epigastrium. The pain can be so severe that patients fear

has allowed an extension of the electrophilic stress food and lose weight. Most,12,86,89 but not all,88 studies have

concept to chronic pancreatitis that is associated with reported that pain diminishes markedly once the disease

gene mutations.32 Thus, the daily exposure of acinar cells burns out (which suggests that viable acini are a prerequisite

to traces of trypsin in people with PRSS1 or SPINK1 for pancreatic pain). However, by then patients often have

mutations is expected to strain glutathione reserves. Of become addicted to narcotic analgesics, which could cause

particular note, those with a CFTR mutation would be them to lose their jobs, homes, or families.88,90

left vulnerable not only to pancreastasis but also to Panel 2 lists factors that might contribute to pain in

intraductal calcifying protein plugs (large duct disease) patients with chronic pancreatitis:36 mast cell degranulation

when the residual CFTR protein is immobilised by products and hydrogen sulphide are plausible mediators

electrophilic stress.32 of the pancreatic component.91,92 The intensity of the pain

contrasts with the absence of specific signs in

Multiple-cause theory

The final hypothesis states that different causative factors

lead to damage via different pathways: this concept Attacks of apparent

acute pancreatitis A Early

incorporates the other theories while noting that Pain

pancreatic ischaemia can aggravate the disease.43

Complications

Clinical features • Bile duct stricture

• Duodenal stricture

Alcoholic chronic pancreatitis presents in the fourth or • Vascular stricture

fifth decade of life and mainly affects men.86 Idiopathic Clinical • Portal hypertension B Intermediate Cause

criteria • Pseudocyst

disease has early-onset (second decade) and late-onset • Pancreatic fistula

(sixth decade) forms, which have equal gender distri- • Pancreatic ascites

bution.12,86 Hereditary disease manifests at around 10 years87 • Rare, eg, colonic

stricture C End stage

and tropical pancreatitis at between 20 and 30 years,65 1 endocrine

whereas the more common type-1 form of autoimmune 2 exocrine

disease affects men in the sixth decade.51 Pancreatic failure 3 both

Presenting features of chronic pancreatitis usually fall

Figure 3: Proposal for a clinically based classification system for

into one of four groups: apparent acute or recurrent acute chronic pancreatitis

pancreatitis (the true diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis is For example, a patient may be described as having chronic pancreatitis

suspected when attacks recur after cholecystectomy); (idiopathic), stage B, bile duct.47

www.thelancet.com Vol 377 April 2, 2011 1189

Seminar

uncomplicated disease. Erythema ab igne is a useful Ordinary chronic pancreatitis has a high mortality

pointer for diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis in these rate—nearly 50% within 20–25 years of disease onset,12

patients, as is meteorism in patients whose pain has led to as a result of complications of an attack, coexisting

dependence on narcotic analgesics (figure 4). An epigastric disease, or the effects of alcoholism. Patients with

swelling suggests a pseudocyst, inflammatory mass, or chronic pancreatitis have an increased risk of pancreatic

cancer. Patients with multisystem involvement usually cancer,93 which accounts for 3% of deaths.86 Although

have the autoimmune form of chronic pancreatitis. the risk of pancreatic cancer is especially high in patients

with hereditary pancreatitis,87 they do not have a higher

mortality risk than the general population.94 Autoimmune

Panel 2: Pain in chronic pancreatitis pancreatitis also does not affect long-term survival.95

Caused by the disease

Diagnosis

Active inflammation*

Routine laboratory tests might reveal incipient diabetes,

Altered nociception type-1 hyperlipidaemia, or hypercalcaemia in patients

• Neurogenic inflammation* with suspected chronic pancreatitis. If type-1 auto-

• Visceral nerve sensitisation* immune disease is a possibility, serology will show

• Central nerve sensitisation raised concentrations of γ-globulin, IgG (IgG4 pre-

• Psychological dominantly), and various antibodies, including anti-

Hypertension lactoferrin, anti-carbonic anhydrase, rheumatoid factor,

• Ductal or tissue via increased cholecystokinin and anti-nuclear antibody.50,51 An abnormal liver function

profile suggests alcoholic liver disease, non-alcoholic

Tissue ischaemia

steatohepatitis,96 sclerosing cholangitis,50,51,96 metastases

Caused by complications from superimposed pancreatic cancer, gallstones, or,

• Inflammatory mass in head of gland most commonly, constriction of the intrapancreatic bile

• Obstruction of bile duct or duodenum duct, which occurs early in autoimmune pancreatitis,50,51

• Pseudocyst but is late otherwise.47

• Cancer of the pancreas Confirmation of the diagnosis of (non-calcific) chronic

pancreatitis is by histology of a wedge biopsy or resected

Caused by treatment specimen of pancreas. However, this is impractical. A

• Opiate gastroparesis or constipation reduction in bicarbonate with or without enzyme

Caused by unrelated problems content of duodenal aspirates after intubation and

• Peptic ulcer hormonal stimulation (by secretin with or without CCK

• Gall stones or its analogue caerulein), and abnormalities in the

• Mesenteric ischaemia pancreatic duct system on endoscopic retrograde

• Small-bowel stricture cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) are the most efficient

• Somatic (eg, surgical scar) alternative diagnostic techniques—with the former

substantially better at detecting small-duct disease than

*Mast cell degranulation products and hydrogen sulphide are potential mediators

(see text).

the latter.2,4 However, the secretory test is available in

only a few centres worldwide (and whether or not an

A B

Figure 4: Clinical features in chronic pancreatitis

(A) Erythema ab igne across the upper abdomen in a young patient with recurrent pancreatitis despite cholecystectomy for multiple gallstones (vertical scar). (B) Plain

abdominal radiograph shows heavy calcification in the pancreatic head (arrow) and a loaded colon in a patient with abdominal distension who was addicted to opiates.

1190 www.thelancet.com Vol 377 April 2, 2011

Seminar

endoscopic secretory test is as good is unclear).97

A B

Moreover, ERCP for diagnosis has largely been

abandoned in favour of magnetic resonance

cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) because ERCP can

precipitate pancreatitis in up to 4% of patients.9

There is no non-invasive test that can substitute for the

hormonal test for chronic pancreatitis.2 By contrast,

sophisticated imaging methods have rapidly developed,

such that the traditional ultrasound scan to visualise the

pancreas itself is virtually obsolete (but see figure 5). The

repertoire of imaging techniques is impressive:

multidetector CT (MDCT; figure 5); MRI;97 MRCP

(figure 6), which provides excellent images of the main

pancreatic duct98 but not always of the side-branch

changes as shown by ERCP; secretin-enhanced MRCP, Figure 5: Examples of ultrasound and multidetector images in patients with chronic pancreatitis

which also shows duodenal filling by pancreatobiliary (A) Transabdominal ultrasound scan showing a uniformly swollen, hypoechoic pancreas (arrowed), typical of

autoimmune pancreatitis. (B) Multidetector CT showing pancreatic calculi in an atrophic pancreas (long arrow)

secretions99 and is more accurate than standard MRCP in and a pseudocyst at the tail of the pancreas (short arrow).

identifying small-duct disease;100 endoscopic ultrasound

(EUS),101,102 which identifies both parenchymal and ductal A B

alterations (figure 6; now classified as the Rosemont

criteria),102 but which is observer-dependent and tends to

overdiagnose the disease;67 diffusion-weighted MRI;103

and PET.104 The last two imaging techniques have not

been properly assessed in chronic pancreatitis, whereas

the role of EUS continues to advance.

No investigation algorithm is suitable worldwide,

because much depends on available resources and

expertise, but a battery of tests should not be used for

diagnosis of suspected chronic pancreatitis because this Figure 6: Examples of three-dimensional magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatogram and endoscopic

will generate many false positive outcomes and cause ultrasound in patients with chronic pancreatitis

distress to the patient.2 Figure 7 presents a sequential (A) Three-dimensional magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatogram shows a minimally dilated biliary tree and

moderately dilated irregular main pancreatic duct. (B) Endoscopic ultrasound scan shows a minimally dilated

scheme for diagnosis of the disease, on the basis of pancreatic duct in the head of pancreas (arrowed) consistent with mild chronic pancreatitis: the distal common

whether or not the secretin test is available. This scheme bile duct appears normal (arrow head).

recognises that an abdominal radiograph will show

pancreatic calculi (nearly 100% specificity; figure 4) in at

least 30% of patients overall and in most patients with disease, for which there are no serum markers), a

tropical pancreatitis. This stepwise approach is therapeutic trial of steroids or histology (of core biopsy or

unnecessary in a patient who presents with fatty stools resected specimen), or both might be needed.50,51

after a long history of pancreatitis attacks or pain. In this There are two difficult diagnostic issues that must be

event, any of the following tests is probably sufficient for addressed. First, how can one distinguish between an

diagnosis: acid steatocrit (high value) on a spot stool inflammatory mass of ordinary chronic pancreatitis, focal

sample (which obviates the need for the traditional 3-day autoimmune disease, and pancreatic adenocarcinoma

faecal fat test);105 faecal elastase (low);105 recovery in expired with upstream chronic pancreatitis? Raised IgG

air of ¹³C (low) from a ¹³C-labelled mixed triglyceride concentrations can occur in all three settings and existing

load;106 or serum trypsinogen (low).4 However, a CT scan tumour markers are not specific enough to distinguish

is needed to identify the disease type. between them, although new molecular markers are being

Imaging tests show distinctive changes in type-1 developed.108 EUS or MDCT-guided core biopsy can be

autoimmune pancreatitis. Both ultrasound and MDCT used to confirm autoimmune pancreatitis, or a simple

typically show a diffusely enlarged sausage-shaped gland needle biopsy might identify tumour cells. ¹⁸F-fluoro-

(figure 5). ERCP shows long or multiple strictures of the deoxyglucose PET with CT facilitates the identification of

pancreatic duct and sometimes a long stricture in the cancer,104 but increased uptake is also a feature of

distal bile duct or sclerosing cholangitis.50,51 Findings autoimmune pancreatitis (as is increased uptake of

from one study suggest that MRCP cannot replace ERCP gallium).50,51 A pancreatectomy specimen might have to be

for the diagnosis of autoimmune disease.107 These used as the final diagnostic test, as it is for detecting an

imaging features are sufficient to make the diagnosis in a intraductal papillary mucinous tumour in a patient who

patient with an increased concentration of IgG4 in serum. has suspected idiopathic large-duct disease.109 Second,

If diagnostic doubt exists (as in a patient with type-2 should the clinician start a search for genetic mutations?

www.thelancet.com Vol 377 April 2, 2011 1191

Seminar

When providing treatment to control the pain

Suspected chronic associated with chronic pancreatitis, the patient’s fears

pancreatitis

and misconceptions about the disease should be

Positive

addressed sympathetically. Time should be spent

Plain radiograph for calculi

discussing the disease with the patient at the first clinic

Negative visit, with particular attention paid to circumstances

Positive

Multidetector CT surrounding the first attack. Patients should be advised

Negative to avoid alcohol and cigarettes, although there is no

Suspected small-duct Large-duct

evidence that abstinence from alcohol slows the disease

disease disease and the effect of alcohol on pain is debated.67,89 A dietary

assessment should be done (see later). Where warranted,

No Secretin test available? the help of a psychologist or pain therapy specialist

Yes should be sought, and the primary-care practitioner

Positive

must also be briefed on treatment strategy. Continuity of

Secretin test care is important to gain the patient’s trust and to

Negative

Positive minimise the risk of addiction to narcotics.

Magnetic resonance

cholangiopancreatography

after secretin stimulation Analgesics

Regular analgesics are superfluous in patients with

Negative

sporadic attacks but are needed in those with background

Positive pain. Use of analgesics should broadly follow WHO

Endoscopic ultrasound

guidelines for cancer pain.110 Briefly, analgesic

Negative

Reconsider other diagnoses Chronic

treatment begins with paracetamol or a non-steroidal

Re-test at intervals pancreatitis anti-inflammatory drug, or both, followed by a mild

Therapeutic trial of opioid such as tramadol, perhaps coupled with a

micronutrients?

neuroleptic antidepressant. Narcotic analgesics should

Figure 7: Algorithm for the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis

be avoided if possible. A simple pain diary with a 10 cm

visual analogue scale is useful, as is a baseline quality-of-

life assessment. Analgesia devices to deliver morphine

A recent review gives valuable guidance.80 PRSS1 mutation that are controlled by the patient should not be used,

testing for diagnostic purposes is acceptable in even in an attack. Such drugs can worsen pain by

symptomatic young individuals or in those with a family inducing mast cell degranulation111 and (possibly thereby17)

history of pancreatitis, but counselling and clinical follow- cause gastroparesis4 and constipation (figure 4).

up are needed if the result is positive. There is no indication

for SPINK1 mutation testing. At present there is no Steroids and enzyme therapy

rationale for CFTR mutation testing in the setting of Treatment with steroids is associated with rapid relief

pancreatitis alone. Instead, a sweat test should be done if of symptoms in autoimmune pancreatitis.50,51 The

atypical cystic fibrosis is suspected, and patients should be starting dose is 30–40 mg per day of prednisolone,

referred to a specialist clinic when sweat chloride which is tapered over 3 months while monitoring

concentration is borderline (40–59 mmol/L) or abnormal serum IgG concentrations and imaging findings. Long-

(>60 mmol/L). However, the vulnerability of CFTR to term maintenance with 5·0–7·5 mg per day of

electrophilic stress potentially explains both false positive prednisolone is recommended to prevent relapses.50

sweat tests and abnormal nasal potential difference studies Recurrences, which typically occur in type-1 disease,95

in a variety of conditions (eg, severe malnutrition).32 favour the development of pancreatic calculi.112

In patients with small-duct disease, pancreatic acinar

Treatment cells are suggested to be under constant stimulation by

Treatment goals CCK because subnormal delivery of pancreatic proteases

The goals of treatment for chronic pancreatitis are to into the duodenum allows improved survival of a CCK-

relieve acute or chronic pain, calm the disease process to releasing peptide from the duodenal mucosa.4 Hence,

prevent recurrent attacks, correct metabolic consequences the following potential treatments have been successfully

such as diabetes or malnutrition, manage complications tested:4 oral pancreatic enzymes (non-enteric coated, two

when they arise, and address psychosocial problems. trials), subcutaneous octreotide (one trial), and oral

Endoscopic treatment, surgery, or both, are only needed dosing with the CCK-A receptor antagonist loxiglumide

when optimum medical treatment fails to relieve pain (one trial). However, this issue is contentious,113,114 and the

(figure 8) and to deal with specific complications (figure 3). explanation that these measures “allow the pancreas to

A detailed discussion of complications is beyond the rest”4 is at odds with the finding that the exocytosis

scope of this Seminar. apparatus is already paralysed in an attack (figure 1) and

1192 www.thelancet.com Vol 377 April 2, 2011

Seminar

hindered thereafter.32 Other explanations might be that

such treatments act by blunting an effect of CCK on pain Painful chronic pancreatitis

pathways in the CNS36 or by ameliorating electrophilic

stress (see later).115 Non-narcotic analgesia

Alcohol and cigarette avoidance

Dietary assessment Exclude non-pancreatic pain Treatment

Micronutrient therapy Psychosocial issues Conservative treatment for 10 weeks effective

Micronutrient therapy is designed to supply methyl and Micronutrient treatment

Pancreatic enzyme treatment Treatment

thiol moieties that are essential for the exocytosis not

apparatus (figure 1) while protecting it against effective

electrophilic attack, as by CYP-derived ROS or reactive

xenobiotics species (figure 2).32 Findings from six

Large–duct disease Small–duct disease

clinical trials have reported that micronutrient therapy

controls pain and curbs attacks in patients with chronic

pancreatitis.116–122 Of these trials, three were Pancreatic mass No mass

descriptive116–118 and three were placebo-controlled.119–122

However, the different ways of expressing outcome

precludes a meta-analysis.123 The study with the highest Treatment

Cyst or pseudocyst Solid mass Endoscopic or surgical

power (80%) to detect a difference between treatment duct drainage effective

and placebo was from Delhi:122 after 6 months’ treatment

(which included pancreatic enzymes in all patients)

Treatment

there was a greater reduction in the number of painful Suspected Suspected not

days per month and in the use of analgesic tablets in autoimmune cancer effective

pancreatitis

the treatment group than in the placebo group;

Treatment

substantially more patients became pain free, and not effective Neural Treatment

biochemical markers of electrophilic stress were Trial of steroids manipulation* effective

lowered by active treatment.

Studies from Manchester, UK, suggested that the Endoscopic CT guided or endoscopic Treatment

drainage ultrasound-guided biopsy not

micronutrient therapy formulation should include effective

methionine and vitamin C,124 with the need for selenium

assessed by measuring blood concentrations. Vitamin E

Treatment Treatment Cancer Doubt

and β carotene were included in the first trial because effective effective confirmed persists

Pancreatectomy

there was no commercial preparation that did not include

them,119 and three of the other five trials also used this Figure 8: Algorithm for the management of painful chronic pancreatitis

protocol.116,121,122 Improvement, as judged by the number of Note that the solid mass in autoimmune pancreatitis is often in the head of pancreas and suggests cancer,

attacks, admission episodes, pain diaries, pain intensity, but that ducts are usually constricted. *Procedures include thoracic splanchnicectomy, coeliac plexus block,

and neurostimulation.

or permutations and combinations of these factors,

occurred by 10–12 weeks.119,121,122 In the UK, the micro-

nutrient therapy preparation Antox (Pharma Nord, glutathione levels have increased and that concentrations

Morpeth, UK) is a convenient means of dosing because it of the prescribed micronutrients are not excessive,

contains all the desired items. A starting regimen of two because this would compromise the physiological roles of

tablets of Antox three times per day provides daily doses ROS.127,128 Very recent reports indicate the need to keep

of 2·88 g methionine (but up to 4 g might initially be track of blood homocysteine, and concentrations of

needed in some patients),125 720 mg vitamin C, 300 μg vitamins (B6, B12, folic acid) that serve as cofactors of

organic selenium, and 210 mg vitamin E (which is enzymes that govern homocysteine removal—either by

unnecessary until steatorrhoea develops).126 This treat- facilitating its transmethylation back to methionine, or by

ment has no significant side-effects now that β carotene ensuring its passage along the transsulphuration pathway

has been withdrawn because of cosmetic problems:125 towards glutathione.32,34,41,129 Of particular interest, elevated

one patient (of >300) developed schizophrenia when on homocysteine has been recorded in people at Soweto

4 g of methionine daily but, of note, this patient had a (South Africa) who drank more than 100 g alcohol per day

strong family history of psychiatric disease.125 for many years130—a group that is traditionally regarded

Patients should also be given dietary advice on as being at high risk of chronic pancreatitis.55

antioxidant-rich foods to aid the long-term management Treatment for 10 weeks is recommended before any

of the disease. It should be stressed that culinary invasive procedure in patients with chronic pancreatitis,

practices—eg, frying vegetables at high temperature (as to calm the disease process. Full treatment is usually

in south India41)—could compromise the bioavailability of needed for 6 months, followed by a gradual dose reduction

antioxidants, notably of ascorbic acid.32 Blood monitoring guided by biochemical data and patients’ symptoms.125 We

is essential to ensure that plasma and erythrocyte recorded treatment failure in 10% of patients, usually

www.thelancet.com Vol 377 April 2, 2011 1193

Seminar

because of non-compliance (eg, in patients who misuse 2 years in patients with intraductal calculi;138 however,

alcohol) or a large cyst or pseudocyst;125 otherwise, lithotripsy can occasionally precipitate acute pancrea-

symptom control was achieved by choline supplements to titis.133 Thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy can provide good

boost methyl supply.32 Moreover, micronutrient therapy initial pain relief, but pain recurs by 15 months in more

has no effect on painful conditions that might be than 50% of patients.139

misdiagnosed as chronic pancreatitis (unpublished); once

validated, this finding could form the basis for a therapeutic Surgery

trial when the diagnosis remains equivocal after full Historically, around 50% of patients with chronic

testing (figure 7). Finally, there is increasing evidence to pancreatitis referred to surgical clinics require an operation

support the idea that a daily micronutrient supplement compared with around 25% on long-term follow-up in a

might abort the development of chronic pancreatitis in specialist medical clinic.88 Micronutrient treatment seems

groups or even populations at risk of the disease.32,130 to substantially reduce the need for surgery.82,125,132 The

Micronutrient treatment is better at controlling pain objectives of surgery are to decompress obstructed ducts

and improving quality of life than conventional (to relieve pain) and at the same time to preserve pancreatic

treatment.131 Moreover, long-term micronutrient tissue as well as adjacent organs (to preserve function),

treatment might curb disease progression.82 Excluding while recognising that the head of the pancreas constitutes

typical autoimmune pancreatitis, which can be treated the so-called pacemaker of chronic pancreatitis. The

with steroids, micronutrient treatment has been effective simplest operation—lateral pancreaticojejunostomy—

irrespective of cause (including mutations in PRSS1,118 provides immediate pain relief in many patients but pain

CFTR,82 and SPINK182), disease duration,131 or ductal tends to recur with the passage of time. Distal pancrea-

anatomy (large-duct calcifying or small-duct disease), tectomy, like pancreaticojejunostomy, does not address the

and also when there is an inflammatory calcified mass.132 problem of disease in the head of the pancreas, which can

By contrast, the antioxidants allopurinol and curcumin continue to deteriorate. Moreover, distal pancreatectomy

have been ineffective for treatment of chronic pancreatitis can result in removal of the functionally most active part of

in clinical trials.32 Two multicentre trials of Antox are the gland. Pancreaticoduodenectomy gives good pain

in progress (Current Controlled Trials numbers relief, but is a major operation. It is indicated in groove

ISRCTN21047731 and ISRCTN44912429). pancreatitis if there is duodenal obstruction or when

neoplasia cannot be ruled out preoperatively.140

Treatment of steatorrhoea and diabetes Duodenum-preserving head resection combined, when

The treatment of pancreatic steatorrhoea usually begins appropriate, with lateral pancreaticojejunostomy has

with 30 000 IU of lipase per meal in an acid-resistant been a major advance: only 8·7% of patients continued to

enzyme preparation. In patients who do not respond to have pancreatic pain at a median of 5·7 years follow-up,

this treatment, a low-fat diet (50–75 g per day), dose whereas 93% of patients had pancreatic pain

increase, gastric proton-pump inhibitor, or a combination preoperatively.141 The operation was simplified by carving

thereof should be recommended.67 A check on fat-soluble out an inverted cone from the pancreatic head, allowing

vitamin status is advisable.126 The main aim in the the cavity and the distal duct to drain into a jejunal loop,

treatment of diabetes in patients with chronic pancreatitis thus removing the complex mass of obstructed ducts and

is to prevent hypoglycaemia caused by deficiency of inflammatory tissue that frequently lies within the head

glucagon; simple insulin regimens are preferable. of the gland.142 A further simplification made this

operation suitable for patients in whom there was little in

Endoscopic treatment the way of duct dilatation: a so-called ice-cream scoop is

Of the many potential indications for endoscopic taken out of the pancreatic head to leave a thin rim of

treatment of chronic pancreatitis,133 two are undisputed. pancreas laterally and posteriorly. Pain improved in

First, EUS can be used to facilitate transmural drainage of 55% of patients after 41 months of follow-up.143

pseudocysts that are not connected to the pancreatic duct A precise assessment of the merits of the different

system, and endoscopically placed transpapillary stents in operations for painful chronic pancreatitis has been

the duct are useful when they do134 or when a duct leak confounded by an absence of agreement about

leads to pancreatic ascites or pleural effusion.135 Second, indications for surgery, details of the surgical

endoscopic stenting of the bile duct is a useful temporary techniques, and methods used to measure outcomes.144

measure in patients with a distal duct stricture. However, there is no doubt that the safety of conser-

Limited comparative data suggest that surgery is more vative operations (eg, lateral pancreaticojejunostomy

effective136 and has a more durable effect in controlling combined with limited excision of the head of the

pain137 than endoscopic dilatation or stenting of the gland) has improved: operative mortality, about 5% with

pancreatic duct. Findings from a randomised clinical traditional resection of the head of pancreas, has fallen

trial showed that extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy to 0–3% and morbidity has been halved.145 There seems

with or without endoscopic clearance of stone fragments to be little if any advantage to be gained from total

was equally effective at reducing pain over the subsequent pancreatectomy with islet transplant.146

1194 www.thelancet.com Vol 377 April 2, 2011

Seminar

Conclusions 22 Capdevila A, Decha-Umphai W, Song K-H, Borchardt RT,

Chronic pancreatitis remains a challenging disease. Wagner C. Pancreatic exocrine secretion is blocked by inhibitors

of methylation. Arch Biochem Biophys 1997; 345: 47–55.

Resective surgery continues to be the definitive treatment 23 Mårtennson J, Bolin T. Sulphur amino acid metabolism in chronic

for persistent pain, but is not ideal in a chronic relapsing pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 1986; 81: 1179–84.

inflammatory process. Micronutrient treatment might 24 Braganza JM, Scott P, Bilton D, et al. Evidence for early oxidative

stress in acute pancreatitis. Int J Pancreatol 1995; 17: 69–81.

offer a viable alternative.

25 Rahman SH, Srinivasan AR, Nicolaou A. Transsulfuration defects

Contributors and increased glutathione degradation in severe acute pancreatitis.

All authors participated in writing this Seminar. All authors saw and Dig Dis Sci 2009; 54: 675–82.

approved the final manuscript. 26 Santini SA, Spada C, Bononi F, et al. Enhanced lipoperoxidation

products in pure pancreatic juice: evidence for organ-specific

Conflicts of interest oxidative stress in chronic pancreatitis. Dig Liver Dis 2003;

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest. 35: 888–92.

Acknowledgments 27 Gutteridge JMC. Lipid peroxidation and antioxidants as biomarkers

We thank Prof J R Foster for the microphotographs (figure 2). of tissue damage. Clin Chem 1995; 41: 1819–28.

28 Jin CX, Hayakawa T, Kitagawa M, Ishiguro H. Lactoferrin

References in chronic pancreatitis. JOP 2009; 10: 237–41.

1 Sarles H. Etiopathogenesis and definition of chronic pancreatitis.

29 Graf R, Schiesser M, Reding T, et al. Exocrine meets endocrine:

Dig Dis Sci 1986; 11 (suppl): S91–107.

pancreatic stone protein and regenerating protein—two sides

2 Braganza JM. The pancreas. Recent Adv Gastroenterol 1986; of the same coin. J Surg Res 2006; 133: 113–20.

6: 251–80.

30 Freedman SD, Sakamoto K, Venu RP. GP2, the homologue to the

3 Walsh TN, Rode J, Theis BA, Russell RCG. Minimal change renal cast protein uromodulin is a major component of intraductal

chronic pancreatitis. Gut 1992; 33: 1566–71. plugs in chronic pancreatitis. J Clin Invest 1993; 92: 83–90.

4 Gupta V, Toskes PP. Diagnosis and management of chronic 31 Rinderknecht H. Pancreatic secretory enzymes. In: Go VLW,

pancreatitis. Postgrad Med J 2005; 81: 491–97. DiMagno EP, Gardner JD, Lebenthal E, Reber HA, Scheele GA, eds.

5 Lévy P, Barthet M, Mollard BR, Amouretti M, The pancreas. Biology, pathobiology, and disease. 2nd edition.

Marion-Audibert AM, Dyard F. Estimation of the prevalence New York: Raven Press, 1993: 219–52.

and incidence of chronic pancreatitis and its complications. 32 Braganza JM, Dormandy TL. Micronutrient therapy for chronic

Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2006; 30: 838–44. pancreatitis: rationale and impact. JOP 2010; 11: 99–112.

6 Otsuki M. Chronic pancreatitis in Japan: epidemiology, prognosis, 33 Syrota A, Dop-Ngassa M, Paraf A. ¹¹C-L-methionine for evaluation

diagnostic criteria, and future problems. J Gastroenterol 2003; of pancreatic exocrine function. Gut 1981; 22: 907–15.

38: 315–26.

34 Girish BN, Vaidyanathan K, Rao NA, Rajesh G, Reshmi S,

7 Garg PK, Tandon RK. Survey on chronic pancreatitis in the Balakrishnan V. Chronic pancreatitis is associated with

Asia–Pacific region. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 19: 998–1004. hyperhomocysteinemia and derangements in transsulfuration

8 Spanier BWM, Dijkgraaf MGW, Bruno MJ. Trends and forecasts and transmethylation pathways. Pancreas 2010; 39: e11–16.

of hospital admissions for acute and chronic pancreatitis in the 35 Shrikhande SV, Martignoni ME, Shrikhande M, et al. Comparison

Netherlands. Eur J Gasroenterol Hepatol 2008; 20: 653–58. of histological features and inflammatory cell reaction in alcoholic,

9 Mitchell RMS, Byrne MF, Baillie J. Pancreatitis. Lancet 2003; idiopathic and tropical chronic pancreatitis. Br J Surg 2003;

361: 1447–55. 90: 1565–72.

10 Whitcomb DC. Mechanisms of disease: advances in understanding 36 Lieb II JG, Forsmark CE. Pain and chronic pancreatitis.

the mechanisms leading to chronic pancreatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009; 29: 706–19.

Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 1: 46–52. 37 Foster JR, Idle JR, Hardwick JP, Bars R, Scott P, Braganza JM.

11 Klöppel G. Chronic pancreatitis, pseudotumors and other Induction of drug-metabolising enzymes in human pancreatic

tumor-like lesions. Mod Pathol 2007; 20: S113–31. cancer and chronic pancreatitis. J Pathol 1993; 169: 457–63.

12 Ammann RW. Diagnosis and management of chronic 38 Wacke R, Kirchner A, Prail F, et al. Up-regulation of cytochrome

pancreatitis: current knowledge. Swiss Med Wkly 2006; P450 1A2, 2C9 and 2E1 in chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas 1998;

136: 166–74. 16: 521–28.

13 Braganza JM. Evolution of pancreatitis. In: Braganza JM, ed. 39 Standop J, Schneider M, Ulrich A, Büchler MW, Pour PM.

The pathogenesis of pancreatitis. Manchester: Manchester Differences in immunohistochemical expression of

University Press, 1991: 19–33. xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes between normal pancreas, chronic

14 Wallig M. Xenobiotic metabolism, oxidant stress and chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Toxicol Pathol 2003; 31: 506–13.

pancreatitis: focus on glutathione. Digestion 1998; 40 Foster JR. Toxicology of the exocrine pancreas. In: Ballantyne B,

59 (suppl 4): 13–24. Marrs T, Syversen T eds. General and applied toxicology, 3rd edn.

15 Gaisano HY, Gorelick FS. New insights into the mechanisms Chichester: John Wiley and Sons, 2009: 1411–55.

of pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2009; 136: 2040–44. 41 Braganza JM. A framework for the aetiogenesis of chronic

16 Cook LJ, Musa OA, Case RM. Intracellular transport of pancreatic pancreatitis. Digestion 1998; 58 (suppl 4): 1–12.

enzymes. Scand J Gastroenterol 1996; 219 (suppl): 1–5. 42 Witt H, Apte MV, Keim V, Wilson JS. Chronic pancreatitis:

17 Braganza JM. Towards a novel treatment strategy for acute challenges and advances in pathogenesis, genetics, diagnosis,

pancreatitis: 1: reappraisal of the evidence on aetiogenesis. and therapy. Gastroenterology 2007; 132: 1557–73.

Digestion 2001; 63: 69–91. 43 Stevens T, Conwell DL, Zuccaro G. Pathogenesis of chronic

18 Sanfey H, Bulkley B, Cameron JL. The role of oxygen-derived free pancreatitis: an evidence-based review of past theories and recent

radicals in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis. Ann Surg 1984; developments. Am J Gastroenterol 2004; 99: 2256–70.

200: 405–13. 44 Casini A, Galli A, Pignalosa P, et al. Collagen type 1 synthesised

19 Dabrowski A, Boguslowicz C, Dabrowska M, Tribillo I, by pancreatic periacinar stellate cells (PSC) co-localizes with lipid

Gabryelewicz A. Reactive oxygen species activate mitogen-activated peroxidation-derived aldehydes in chronic alcoholic pancreatitis.

protein kinases in pancreatic acinar cells. Pancreas 2000; J Pathol 2000; 192: 81–89.

21: 376–84. 45 Zimnoch L, Szynaka B, Puchalski Z. Mast cells and pancreatic

20 Leung P, Chan YC. Role of oxidative stress in pancreatic stellate cells in chronic pancreatitis with differently intensified

inflammation. Antioxid Redox Signal 2009; 11: 135–65. fibrosis. Hepatogastroenterology 2002; 49: 1135–38.

21 Chavnov M, Petersen OH, Tepikin A. Free radicals and 46 Lindstedt KA, Wang Y, Shiota N, et al. Activation of paracrine

the pancreatic acinar cells: role in physiology and pathology. TGF-beta1 signaling upon stimulation and degranulation of rat serosal

Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2005; 360: 2273–84. mast calls: a novel function for chymase. FASEB J 2001; 15: 1377–88.

www.thelancet.com Vol 377 April 2, 2011 1195

Seminar

47 Buchler MW, Martigone ME, Friess H, Malfertheiner P. A proposal 75 Ramamoorthy S, Nawaz Z. E6-associated protein is a dual

for a new clinical classification of chronic pancreatitis. function coactivator of steroid hormone receptors.

BMC Gastroenterol 2009; 9: 93. Nucl Recept Signal 2008; 6: e006.

48 Longnecker DS. Pathology and pathogenesis of diseases 76 Steven FS, Al-Habib A. Inhibition of trypsin and chymotrypsin

of the pancreas. Am J Pathol 1982; 107: 103–21. by thiols. Biochim Biophys Acta 1979; 568: 408–15.

49 O’Sullivan BP, Freedman SD. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet 2009; 77 Halangk W, Krüger B, Ruthenbürger M, et al. Trypsin activity is

373: 1891–904. not involved in premature, intrapancreatic trypsinogen activation.

50 Shimosegawa T, Kanno A. Autoimmune pancreatitis in Japan: Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2002; 282: G367–74.

overview and perspective. J Gastroenterol 2009; 44: 503–17. 78 Archer H, Jura N, Keller J, Jacobson M, Bar-sag D. A mouse

51 Park DH, Kim M-H, Chari S. Recent advances in autoimmune model of hereditary pancreatitis generated by transgenic

pancreatitis. Gut 2009; 58: 1680–89. expression of R122H trypsinogen. Gastroenterology 2006;

52 Wagner ACC. Serological tests to diagnose chronic pancreatitis. 131: 1844–55.

In: Buchler MW, Friess H, Uhl W, Malfertheiner P, eds. Chronic 79 Chen JM, Férec C. Chronic pancreatitis: genetics and

pancreatitis: novel concepts in biology and therapy. London: pathogenesis. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 2009; 10: 63–87.

Blackwell, 2002: 217–22. 80 Ooi CY, Gonska T, Durie PR, Freedman SD. Genetic testing

53 Frulloni L, Gabrielli A, Pezzilli R, et al. Chronic pancreatitis: report in pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2010; 138: 2202–06.

from a muticenter Italian survey (PanCronfAISP) on 893 patients. 81 Mahurkar S, Nageshwar Reddy D, Rao GV, Chandak GR. Genetic

Dig Liver Dis 2009; 41: 311–17. mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of tropical calcific

54 Yan M-X, Li Y-Q. Gall stones and chronic pancreatitis: the black box pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 21: 256–69.

in between. Postgrad Med J 2006; 82: 254–58. 82 Midha S, Khaguria R, Shastri S, Kabra M, Garg PK. Idiopathic

55 Yadav D, Whitcomb DC. The role of alcohol and smoking chronic pancreatitis in India: phenotypic characterization and

in pancreatitis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010; 7: 131–45. strong genetic susceptibility due to SPINK1 and CFTR mutations.

56 Yang AL, Vadhavkar S, Singh G, Omary MB. Epidemiology of Gut 2010; 59: 800–07.

alcohol-related liver and pancreatic disease in the United States. 83 Cohn JA. Reduced CFTR function and the pathobiology of

Arch Intern Med 2008; 168: 649–56. idiopathic pancreatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2005; 39: S70–77.

57 Pezzilli R. Etiology of chronic pancreatitis: has it changed in the last 84 Ko SB, Mizumo N, Yatabe Y, et al. Corticosteroids correct aberrant

decade? World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15: 4737–40. CFTR localization in the duct and regenerate acinar cells in

58 Pandol SJ, Rarity M. Pathobiology of alcoholic pancreatitis. autoimmune pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2010; 138: 1988–96.

Pancreatology 2007; 7: 105–14. 85 Segal I. Pancreatitis in Soweto, South Africa: focus on alcohol.

59 Li J, Guo M, Liu R, Wang R, Tang C. Does chronic ethanol intake Digestion 1998; 59 (suppl 4): 25–35.

cause chronic pancreatitis?: evidence and mechanism. Pancreas 86 Layer P, Yamamoto H, Kalthoff L, Clain JE, Bakken LJ,

2008; 37: 189–95. DiMagno EP. The different courses of early and late-onset

60 Balakrishnan V, Unnikrishnan AG, Thomas V, et al. Chronic idiopathic and alcoholic chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology

pancreatitis: a prospective nationwide study of 1086 subjects from 1994; 107: 1481–87.

India. JOP 2008; 9: 593–600. 87 Rosendahl J, Bödeker H, Mössner J, Teich N. Hereditary chronic

61 Dufour MC, Adamson MD. The epidemiology of alcohol-induced pancreatitis. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2007; 2: 1.

pancreatitis. Pancreas 2003; 27: 286–90. 88 Lankisch PG, Löhr-Happe A, Otto J, Creutzfeldt W. Natural course

62 Strubelt O. Interaction between ethanol and other hepatotoxic in chronic pancreatitis. Digestion 1993; 54: 148–55.

agents. Biochem Pharmacol 1980; 29: 1445–49. 89 Bornman PC, Girdwood AH, Marks IN, Hatfield ARW, Kottler RE.

63 Lieber CS. The discovery of the microsomal ethanol oxidizing The influence of continued alcohol intake, pancreatic duct

system and its physiological and pathological role. Drug Metab Rev hold-up, and pancreatic insufficiency on the pain pattern in

2004; 36: 511–12. chronic noncalcific and calcific pancreatitis: a comparative study.

Surg Gastroenterol 1982; 1: 5–9.

64 Gonzalez FJ. Role of cytochromes P450 in chemical toxicity and

oxidative stress: studies with CYP2E1. Mutat Res 2005; 569: 101–10. 90 Gardner TB, Kennedy AT, Gelrud A, et al. Chronic pancreatitis

and its effect on employment and health care experience: results

65 Barman KK, Premalatha G, Mohan V. Tropical chronic pancreatitis.

of a prospective American multicenter study. Pancreas 2010;

Postgrad Med J 2003; 79: 606–15.

39: 498–501.

66 Balakrishnan V. Tropical pancreatitis—epidemiology, pathogenesis

91 Hoogerwerf WA, Gondesen K, Xiao SY, Winston JH, Willis WD,

and aetiology. In: Balakrishnan V, ed. Chronic pancreatitis in India.

Pasricha PJ. The role of mast cells in the pathogenesis of pain in

Trivandrum: St Joseph’s Press, 1987: 81–85.

chronic pancreatitis. BMC Gastroenterol 2005; 5: 8.

67 Di Magno MJ, Wamsteker E-J, Lee A. Chronic pancreatitis.

92 Nishimura S, Fukushima H, Takahashi T, et al. Hydrogen sulfide

BMJ Best Practice 2010. http://bestpractice.bmj.com/best-practice/

as a novel mediator for pancreatic pain in rodents. Gut 2009;

monograph/67/highlights.html (accessed Feb 12, 2011).

58: 762–70.

68 Wittel UA, Hopt UT, Batra SK. Cigarette smoke-induced pancreatic

93 Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, Cavallini G, et al. Pancreatitis

damage: experimental data. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2008;

and the risk of pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 1993; 328: 1433–37.

393: 581–88.

94 Rebours V, Boutron-Ruault M-C, Jooste V, et al. Mortality rate

69 Hao J-Y, Li G, Pang B. Evidence for cigarette smoke-induced

and risk factors in patients with hereditary pancreatitis: uni- and

oxidative stress in the rat pancreas. Inhalation Toxicol 2009;

multidimensional analyses. Am J Gastroenterol 2009; 104: 2312–17.

21: 1007–12.

95 Sah RP, Chari ST, Pannala R, et al. Differences in clinical profile

70 McNamee R, Braganza JM, Hogg J, Leck I, Rose P, Cherry N.

and relapse rate of type 1 versus type 2 autoimmune pancreatitis.

Occupational exposure to hydrocarbons and chronic pancreatitis:

Gastroenterology 2010; 139: 140–48.

a case-referent study. Occup Environ Med 1994; 51: 631–37.

96 Braganza JM. The role of the liver in exocrine pancreatic disease.

71 Braganza JM, John S, Padmayalam I, et al. Xenobiotics and tropical

Int J Pancreatol 1988; 3: S19–42.

pancreatitis. Int J Pancreatol 1990; 7: 231–45.

97 Balci NC, Smith A, Momtahen AJ, et al. MRI and S-MRCP

72 Jeppe CY, Smith MD. Transversal descriptive study of xenobiotic

findings in patients with suspected chronic pancreatitis:

exposures in patients with chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic

Correlation with endoscopic pancreatic function testing (Epft).

cancer. JOP 2008; 9: 235–39.

J Magn Reson Imaging 2010; 31: 601–06.

73 Merkord J, Weber H, Jonas L, Nizze H, Henninghausen G.

98 Tamura R, Ushibashi T, Takahashi S. Chronic pancreatitis: MRCP

The influence of ethanol on long-term effects of dibutyltin

versus ERCP for quantitative caliber measurement and qualitative

dichloride (DBTC) in pancreas and liver of rats. Hum Exp Toxicol

evaluation. Radiology 2006; 238: 920–28.

1998; 17: 144–50.

99 Czako L. Diagnosis of early-stage chronic pancreatitis by

74 Frulloni L, Lunardi C, Simone R, et al. Identification of a novel

secretin-enhanced magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography.

antibody associated with aotuimmune pancreatitis. N Engl J Med

J Gastroenterol 2007; 42 (suppl 17): 113–17.

2010; 361: 2135–42.

1196 www.thelancet.com Vol 377 April 2, 2011

Seminar

100 Sai JK, Suyama M, Kubokawa Y, Watanabe S. Diagnosis of mild 123 Monfared SSMS, Vahidi H, Abdolghaffari AH, Nikfar S,

chronic pancreatitis (Cambridge classification): comparative study Abdollahi M. Antioxidant therapy in the management of acute,

using secretin injection-magnetic resonance chronic and post-ERCP pancreatitis: a systematic review.

cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic retrograde World J Gastroenterol 2010; 15: 4481–90.

pancreatography. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14: 1218–21. 124 Bilton D, Schofield D, Mei G, Kay PM, Bottiglieri T, Braganza JM.

101 Kahl S, Glasbrenner B, Leodolter A, Pross M, Schulz HU, Placebo-controlled trials of antioxidant therapy in patients with

Malfertheiner P. EUS in the diagnosis of early chronic pancreatitis: recurrent pancreatitis. Drug Invest 1994; 8: 10–20.

a prospective follow-up study. Gastrointest Endosc 2002; 55: 507–11. 125 McCloy RF. Chronic pancreatitis at Manchester, UK. Focus

102 Catalano MF, Sahai A, Levy M, et al. EUS-based criteria for the on antioxidant therapy. Digestion 1998; 59 (suppl 4): 36–48.

diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis: the Rosemont classification. 126 Dominguez-Muňoz JE, Iglesias-Garcia J. Oral pancreatic enzyme

Gastrointest Endosc 2009; 169: 1251–61. substitution therapy in chronic pancreatitis: is clinical response an

103 Balci NC, Perman WH, Saglam S, Akisik F, Fattahi R, Bilgin M. appropriate marker for evaluation of therapeutic efficacy? JOP 2010;

Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the pancreas. 11: 158–62.

Top Magn Reson Imaging 2009; 20: 43–47. 127 Li T-S, Marbán E. Physiological levels of reactive oxygen species are

104 Kumar R, Kumari A, Garg P, et al. Role of F18-FDG PET-CT required to maintain genomic stability in stem cells. Stem Cells

imaging in differentiating benign and malignant pancreatic lesions 2010; 28: 1178–85.

and its comparison with CT/MRI/EUS. J Nucl Med 2009; 128 Gutteridge JMC, Halliwell B. Antioxidants: molecules, medicines,

50 (suppl 2): 1755. and myths. Biochim Biophys Res Commun 2010; 393: 561–64.

105 Girish BN, Rajesh G, Vaidyanathan K, Balakrishnan V. Fecal 129 Braganza JM, Odom N, McCloy RF, Ubbink JB. Homocysteine

elastase1 and acid steatocrit estimation in chronic pancreatitis. and chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas 2010; 39: 1303–04.

Indian J Gastroenterol 2009; 28: 201–05. 130 Segal I, Ally R, Hunt LP, Sandle LN, Ubbink JB, Braganza JM.

106 Nakamura H, Morifuji M, Murakami Y, et al. Usefulness of a Insights into the development of alcoholic chronic pancreatitis at

13C-labeled mixed triglyceride breath test for assessing exocrine Soweto, South Africa: a controlled cross-sectional study. Pancreas

function after pancreatic surgery. Surgery 2009; 145: 168–75. (in press).

107 Kamisawa T, Tu Y, Egawa N, Okamoto A, Kodama M, Kamata N. 131 Shah NS, Makin AJ, Sheen AJ, Siriwardena AK. Quality of life

Can MRCP replace ERCP for the diagnosis of autoimmune assessment in patients with chronic pancreatitis receiving

pancreatitis? Abdom Imaging 2009; 34: 381–84. antioxidant therapy. World J Gatroenterol 2010; 16: 4066–71.

108 Mendieta Zerón H, Garcia Flores JR, Romero Prieto ML. 132 Sharer NM, Taylor PM, Linaker BD, Gutteridge JMC, Braganza JM.

Limitations in improving detection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Safe and successful use of vitamin C to treat painful calcific chronic

Future Oncol 2009; 5: 657–68. pancreatitis despite iron overload from primary haemochromatosis.

109 Pezzilli R. Intraductal papillary-mucinous tumor of the pancreas: Clin Drug Invest 1995; 10: 310–15.

the clinical research continues. JOP 2004; 5: 53–55. 133 Heyries L, Sahel J. Endoscopic treatment of chronic pancreatitis.

110 WHO. Cancer pain relief and palliative care: report of a WHO World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13: 6127–33.