Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Leading Lean: A Canadian Healthcar e Leader' S Guide: Feature

Uploaded by

Suman Saurabh MohantyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Leading Lean: A Canadian Healthcar e Leader' S Guide: Feature

Uploaded by

Suman Saurabh MohantyCopyright:

Available Formats

Feature

d i a n

a n a

: A C u i d e

L e an e r ’s G

d i n g e a d

L e a a re L

a lt h c

H e

Ben Fine, Brian Golden,

Rosemary Hannam and Dante J. Morra

One proven approach is Lean. As we show, once an organiza-

Abstract tion is familiar with Lean methodology, it takes no more than a

Canadian healthcare organizations are increasingly asked few hours of observation on the front lines to uncover opportu-

to do more with less, and too often this has resulted in nities for improvement, such as repeated laboratory orders, staff

demands on staff to simply work harder and longer. Lean walking miles to find equipment and forms produced and never

methodologies, originating from Japanese industrial organ- read. These non-value-added steps, called muda in Japanese and

izations and most notably Toyota, offer an alternative – tried waste in English, impede the quality of care, increase wait times

and tested approaches to working smarter. Lean, with its and cost the public money. Toyota pioneered Lean and has

systematic approaches to reducing waste, has found its led the world in demonstrating its benefit. Lean thinking has

way to Canadian healthcare organizations, with promising propelled Toyota to become the world’s most profitable automo-

results. This article reports on a study of five Canadian bile manufacturer and a leader in quality (May 2007).

healthcare providers that have recently implemented Lean. While Lean was developed originally in the automotive

We offer stories of success but also identify potential obsta- sector, it has spread across the manufacturing and the service

cles and ways by which they may be surmounted to provide industries to companies such as Southwest Airlines, Alcoa and

better value for our healthcare investments. Vanguard Insurance (Spear 2005). Recently, the healthcare

industry has demonstrated success using these principles in the

United States, United Kingdom, Australia and now Canada

V

(Royal Bolton Hospital 2009; Bush 2007; Ben-Tovim et al.

face the same challenge:

irtually all healthcare systems 2007; Foster 2007; Kim et al. 2006; Institute for Healthcare

improving the quality of patient care, increasing the Improvement 2005). In healthcare, there is an opportunity to

number of patients served and reducing wait times, do more with less – if we can eliminate that waste. This oppor-

while keeping spiralling costs in check. For many, it is difficult tunity is found in supporting front-line staff to identify and

to imagine finding new opportunities to do more and better remove unnecessary steps from their everyday work. This is the

with less; yet such demands persist, and many organizations, in essence of Lean, and it has been employed in manufacturing

fact, continue to succeed. industries for decades. It is now becoming a critical tool for

26 Healthcare Quarterly Vol.12 No.3 2009

Ben Fine et al. Leading Lean: A Canadian Healthcare Leader’s Guide

healthcare leaders (Macleod et al. 2008).

This article is intended to serve as a practical guide for health- Lean Terminology: What Does It All Mean?

care leaders who may be considering using Lean approaches to Lean: A term coined by those who compared Toyota’s

value creation. We first introduce the concepts of Lean applied methods to those of other manufacturers: “Lean is the

to healthcare and then document the Lean experiences and antidote to waste … It provides a way to specify value, line-

up value-creating actions in the best sequence, conduct

lessons of five Canadian hospitals.

these activities without interruption whenever someone

requests them, and perform more and more effectively”

Lean 1-2-3

(Womack et al. 1990; Womack and Jones 2003).

Great Waste, Great Opportunity

Value-added work: Work that adds value from the perspec-

Healthcare is an ideal environment in which to reap the

tive of the client or customer; it is the kind of activity or

benefits of Lean. To understand why, managers and clinicians service for which end users are willing to pay. In healthcare

must first accept that waste equals opportunity: the more waste this could be the taking of blood for a medically necessary

(repeated steps, rework and unnecessary motion) that exists in a test or patient time spent with an examining physician.

process, the greater the opportunity is to convert that waste into Waste or muda: Activities of overproduction, waiting, trans-

value-added activities. Remove the “waste of making defective portation, processing, inventory, movement and defective

products,” and quality improves. Remove the “waste of inven- products. Type 1 muda represents activities that cannot be

tory,” and capital is freed up to invest elsewhere. Remove the avoided immediately given current assets and technologies. If

“waste of waiting,” and patient wait times are reduced (see Table a physician cannot eliminate the need to fill out a drug aller-

1 for Taichi Ohno’s seven wastes as applied to health care) (Bush, gies form because of an existing policy, that muda is catego-

R. W., 2007). While virtually all Canadian healthcare organiza- rized as type 1. In contrast, type 2 muda is clearly wasteful

tions have attempted to drive out waste, many have concluded activity; it is the prime target for immediate elimination.

that the well has run dry; Lean reveals new opportunities to Value stream map: Visual presentation of activities required

improve effectiveness. to bring a service or product from customer order to delivery.

Value-added steps and muda are most easily identified on

Lean on the Ground a value stream map. The mapping starts with defining what

the customer demands (in the top right corner) and then

Unfortunately, Lean is often presented as a mystical process, only

captures all the steps required to fulfillment. The “current

to be practised by “Lean Wizards” – a.k.a. management consul-

state” value stream map represents the steps, similar to

tants. Too often, unless one is working with teaching-oriented the filling of a customer order. The “future state” value

consultants and trainers, the magical benefits of Lean disappear stream map is a visual representation of an idealized state.

shortly after the consultants leave. There is nothing magical Improvement activities (like kaizen events below) undertaken

about Lean other than the leadership and discipline needed by front-line staff move the process toward the future state.

to bring a change to an organization’s culture and processes. Gemba: In Japanese, gemba means “actual place.” In the

In short, waste is eliminated through a structured process that Lean context, it refers to the place where value is actually

trains and empowers front-line workers. The example outlined created: the shop floor in manufacturing, or a clinic (e.g.,

below in steps one to five describes what Lean might look like emergency department, outpatient dialysis unit, or operating

in early stages in an organization (Lummus et al. 2006; Joint room) in the healthcare setting. The concept of gemba is

Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations important because it emphasizes the Lean principle that

2006; Kim et al. 2006; Institute for Healthcare Improvement value – what customers actually want – is created on the

2005; Laing and Baumgartner 2005; Thompson et al. 2003). front lines, not in boardrooms. The value stream mapping

exercise forces workers to “walk the gemba” to see value

Imagine the following: Twelve staff members from the

and the process that creates it.

emergency department (a few nurses, a ward clerk, a physician, a

porter, cleaning staff and the manager) walk into a single room. Kaizen event or rapid improvement event (RIE): Kaizen

means “improvement” in Japanese, and kaizen events are

Each day, this group works side by side delivering care, and

focused on implementing improvements to the process of

yet they have never taken the opportunity to discuss how to

meeting customer demands. In healthcare, these week-long

improve their collective work. An executive stands at the front events provide the opportunity for front-line workers from

of the room to set the stage, and a Lean facilitator – an expert different disciplines to work together to rapidly plan, imple-

in Lean methodologies – takes the lead. ment, measure and adjust improvements.

Kamikaze kaizen: Kaizen activities that improve an isolated

Step One: Define Value segment of a process but negatively affect the entire process

Front-line workers are led through a conversation on “value” are referred to as “kamikaze kaizens.”

(Figure 1). What do patients want and need from a visit to the

Healthcare Quarterly Vol.12 No.3 2009 27

Leading Lean: A Canadian Healthcare Leader’s Guide Ben Fine et al.

Table 1. Ohno’s 7 Wastes as Applied to Health Care * Bush, R. W. JAMA 2007;297: 871-874.

Waste Description Examples in Health Care Process Remedies at Virginia Mason

Medical Center

Waste of Producing what is unnecessary, when it Fragmented, parallel care: separate Multidisciplinary bedside rounds, with

overproduction is unnecessary, and in an unnecessary resident, attending, social services, contemporaneous documentation

amount pharmacy, and care management and order entry by portable wireless

rounding cycles; making photocopies computer; primary care physician

of a form that is never used; providing flow stations incorporate many lean

copies of reports to people who principles

have not asked for them and will not

actually read them; processing piles

of documents that then sit at the next

work station; cc’s on e-mails

Waste of time on Waiting for materials, operations, Patients waiting to see their physician; Patients are advised at point of care

hand (waiting) conveyance, inspection, idle time office staff batching test results for when tests will be available, and test

attendant to monitoring and operation patients; waiting on the phone to results are reported as they become

procedures, rather than just-in-time schedule appointments; early-morning available; emergency department

supply or “pull production” admits for surgeries that won’t be physicians enter orders in the electronic

performed until later in the day; waiting medical record within 15 minutes of

for support services such as internal patient arrival

transport; waiting for office equipment

(computer, photocopier, etc.) to be

repaired before being able to do work:

waiting for a meeting that is starting

late

Waste in Conveying, transferring, picking up/ Moving individual files from one Travel for chemoradiation reduced 55%,

transportation setting down, piling up, and otherwise location to another; moving supplies to 544 feet and 12 floors, by providing

moving unnecessary items; problems into and out of a storage area; moving injections and dressing changes in

concerning conveyance distances, equipment for surgeries in/out of radiation oncology department; instead

conveyance flow, and conveyance operating and procedure rooms; of patients or supplies traveling to and

utilization rate patients receiving chemoradiation from isolated process villages, the input

treatment traveling 1220 horizontal feet proceeds through the operations in

and 25 vertical floors per episode single-piece-flow in 1 short space

Waste of Unnecessary processes and operations Hard copies of memos already sent by Hyperbaric oxygen indications

processing traditionally accepted as necessary e-mail or posted on intranet; redundant negotiated with payers, who have

capture of information at admission; agreed to waive preapproval; redesign

multiple recording and logging of data; of chamber to allow emergency cases

writing by hand, when direct input to without canceling scheduled patients;

a word processor could eliminate this eliminate medication lists on electronic

step; producing paper hard copy when medical records progress notes

a computer file is sufficient; patients

waiting for preapproval of urgent

treatments

Waste of Inventory waste is when anything Office supplies in hallways; expensive Surgeons now accept only those

stock on hand – materials, parts, assembly part clinical supplies and implants that can instruments that are frequently used,

(inventory) – is retained for any length of time, be ordered on a just-in-time basis; or 25 instruments, in the operating

including not only warehouse stock charge slips piled up to be dictated; room kit

but also items in the factory that are unnecessary instruments in operating

retained at or between processes room kits

28 Healthcare Quarterly Vol.12 No.3 2009

Ben Fine et al. Leading Lean: A Canadian Healthcare Leader’s Guide

Waste of Movement that is unnecessary, that Physicians and nurses leaving patient Common supplies are stocked in

movement does not add value, or that is too slow rooms for common supplies or hospital, operating, and outpatient

or too fast information rooms, with visually controlled

restocking system; computer access

in outpatient examination rooms

and wireless portable computers for

inpatient rooms

Waste of making Waste related to costs for inspection Iatrogenic illness; fixing errors made Ventilator-acquired pneumonia bundles

defective of defects in materials and processes, in documents; misfiling documents; decreased annual incidence from

products customer complaints, and repairs; dealing with complaints about 40 to 5 cases; patient safety alerts;

passing defects down to a coworker or service; mistakes caused by incorrect computerized clinician order entry

patient, rather than the defect producer information or miscommunication;

“feeling the pinch” handwritten orders; sending out bills

with an incorrect address

*Adapted from Ohno.14

Copyright 2007 American Medical Association. All Rights Reserved.

emergency department? Despite years of struggling to provide it the patient comes in the door until discharge) is drawn as boxes

and the best intentions to do so, staff have no trouble answering or placed as sticky notes on the paper (Figure 2). To learn more

the question: patients want an accurate diagnosis and appro- about the process, the staff may leave the room and “walk the

priate treatment without mistakes and without wasted time. To line” (“gemba”) from the perspective of the patient, observing

get this group to the long elusive next step, the concepts of value- the activities that are required to deliver care. The output is a

added work and muda are introduced as a way of systematically current state value stream map that covers the wall, depicting the

steps in this emergency

department process as

they exist from begin-

Figure 1. The five principles of Lean thinking* ning to end. Waste is

attributed to the process

������ ���������� ���� of activity, not to the

���� ����

����� ������������ ���������� failings of any individ-

uals. This framing is

critically important

*As defined by Womack and Jones (2005). if staff are to become

engaged and not feel

threatened.

Also noteworthy

classifying the kind of work that has been done in the past and, about this early experience is that, for the first time, a multipro-

more importantly, that must be done in a waste-free process. fessional and administrative team can (1) appreciate the work

of all team members – and the connections between their work

Step Two: Arrange by Value Stream – and (2) see the total amount of work required to deliver care

In the beginning, there is an unspoken belief that every activity to one patient. The feeling is nearly unanimous in the room: “I

is value added. Who, after all, wants to believe that the work can’t believe there are so many steps, some of them so silly; there

they do is not value added? Mindsets shift as the discussion must be plenty of room for us to improve how we work.”

continues, allowing the team to realize that some activities are The facilitator next leads the team through a series of

muda from the patient’s perspective (see Table 1). Value stream questions to help them identify opportunities for improvement

mapping helps the team see the waste. The team sits in front of in this value stream. He or she points to each box and asks the

a big piece of craft paper taped on the wall. The sequence of team: “Is the step valuable or is it wasteful activity – waiting,

steps in a specific process (e.g., delivering care from the point rework or unnecessary motion in looking for items?” “How

Healthcare Quarterly Vol.12 No.3 2009 29

Leading Lean: A Canadian Healthcare Leader’s Guide Ben Fine et al.

“future state” in the form of a value stream map that comes

Figure 2. North York General Hospital staff from across closer to perfection. The new process may have fewer steps,

disciplines at a value stream mapping kaizen event

leading to lower cost and a shorter stay. This map becomes the

vision that guides all improvements.

Next, the process is standardized and each step is well defined,

eliminating the uncertainty and confusion that often leads to

errors. For example, the new process may place all heparin vials

in one box and insulin in another to help prevent medication

errors. Improvements are prioritized and added to the value

stream map. Seeing all the potential improvements on the

value stream map helps the team to avoid “kamikaze kaizens,”

improvements that better one section of the process without

positively impacting the whole. The team leaves the room

knowing exactly who needs to do what, by when, in order to

achieve the future state.

With waste identified, the team moves to a process of disci-

plined waste elimination. Here, Lean theory is flexible. Since

each individual situation is different, staff are encouraged to

use whatever method is most appropriate to remove the waste.

does the work at this stage positively or negatively impact the (Common choices from industrial engineering and manage-

work of others down the stream?” It becomes clear that staff ment science include The Deming Cycle, PDCA, or A3 problem

have a number of workarounds (steps they take to get around solving. Any method that produces results would be acceptable.)

a problem with the process) that are wasteful (Hollingsworth In some cases, the elimination of waste simply involves moving

et al. 1998). Team members tag wasteful steps for elimination equipment to a new location. For example, the nurse returns to

(with a sticky note) on the value stream map for all to see. The the ward and creates a “home” for the telemetry units to prevent

total number of steps in the process begins to drop, and cost and future waste of motion. More complicated waste-removal initia-

length of stay drop with it. tives are left for kaizen weeks – week-long events for front-line

staff dedicated to continuous improvement. For each waste-

Step Three: Flow reduction project, the front-line workers establish measures of

Next, the facilitator asks, “Does the patient ‘flow’?” For example, success that are meaningful to them.

when a patient walks in the door, is she triaged, then registered As initiatives are implemented, the emergency department

and then seen by a physician without interruption, or does she begins to see a drop in wait times, improved job satisfaction due

queue between these steps? Ideas are generated to remove the to a reduction in workarounds and a reduction in errors. Two

waits between steps, such as removing the second waiting room or three small changes quickly lead to an extra bed and an extra

after registration. The net result of flow is a reduction in the patient seen each day. More importantly, Lean becomes part of the

time from beginning to the end of the patient’s experience. culture, and waste can be easily spotted, identified and corrected

By removing the waiting, underlying waste can be more easily at multiple levels. Continuous improvement persists until the

identified and addressed. future state is achieved. Then the entire process begins again.

Step Four: Pull The Canadian Experience

A further question is asked: “Does the process allow customers We turn now to lessons we have learned from studying Lean

to pull value?” Conventional thinking has the emergency room implementations in Canada. We first present the three Ls

“pushing” patients from the waiting room when registration is critical to successful Lean implementations: launch, learning

complete, only to have them wait again. A “pull” system has and leading. We conclude with lessons shared by hospital leaders

the healthcare worker who finishes preparing an empty bed from ongoing lean initiatives.

bring the patient from the waiting room to ensure the bed does Our study involved semi-structured interviews with

not sit idle. As pull is implemented, the time from the patient five Canadian organizations between December 2007 and

demanding care to the time care is delivered begins to drop. March 2008. These included the Five Hills Health Region

in Saskatchewan, two community teaching hospitals (North

Step Five: Continuously Seek Perfection York General Hospital and St. Joseph’s Health Centre, both in

The ideas generated by the team lead the group to envision a Toronto, Ontario), a quaternary care research centre (Toronto’s

30 Healthcare Quarterly Vol.12 No.3 2009

Ben Fine et al. Leading Lean: A Canadian Healthcare Leader’s Guide

University Health Network [UHN]) and a regional tertiary constraint – funding. Fortunately, four of five hospitals in this

care centre (Hotel-Dieu Grace Hospital in Windsor, Ontario). study were provided with government funding to make the

The goal was to highlight how these organizations began their Lean improvement initiative possible. The investment covered

Lean initiatives and to identify some lessons helpful to others hiring Lean expertise, education programs within the organiza-

applying Lean in a Canadian setting. The interviewees included tion, compensating staff, and for systems. The return on this

a chief executive officer (CEO), directors of quality/patient investment for these five hospitals would come in the form of

safety, a director of a clinical program, a senior project manager reduced wait times, a change in culture and improved patient

and a designated Lean coordinator. Semi-structured interviews safety. None of this could have occurred, however, without suffi-

were performed by phone or in person, with the 18 questions cient start-up resources – which would only later prove to have

provided beforehand. Notes were taken during the interview, a positive return on investment.

and data were sorted by theme. Some data were obtained

through correspondence after the interviews. Table 2 describes Learning

the sites and provides details about the Lean initiatives. When Five Hills’ CEO Dan Florizone returned from experi-

encing Lean in action at Seattle’s Virginia Mason Medical Centre,

Launch he commented that he “knew enough to do damage.” That is,

What prompted the above organizations to begin Lean projects? he knew Lean could work and wanted to make it happen, but

For some, such as Hotel-Dieu Grace, it started with a crisis: the he lacked the know-how to accomplish anything. Even worse,

hospital was featured in the local newspaper for its long wait he realized that an early failure of execution might kill the credi-

times. For other sites, motivation came from a challenge from bility of future Lean efforts. To address his problem, he went to

leadership – the need to transform the organization and deliver a nearby wire manufacturer that had previously implemented

better quality service to patients within the available budget. Lean when it swept across the manufacturing industry. Florizone

We also observed that each organization had an internal aimed to recruit a Lean black belt (a trained Lean expert), Dale

champion to seed the idea of Lean due to personal experience Schattenkirk, to come and work for Five Hills with the promise

with the approach. For instance, Dan Florizone, CEO of Five that he could apply his knowledge to save lives. Schattenkirk

Hills Health Region, spent a week participating in a rapid had been down the challenging path of implementing Lean and

improvement event at Virginia Mason Medical Centre along- was skeptical that Florizone understood what he was getting

side front-line workers. After seeing Lean in action in another into. Once Florizone assured Schattenkirk that the hospital was

institution, he led the commitment to go Lean. For other organ- in this for the long-haul, and that this project was not a passing

izations such as UHN, those who became champions of Lean fancy, Schattenkirk agreed to lead Lean.

had heard about the initiative at a hospital in the same city. Like Five Hills, four of the five hospitals hired or trained staff

Finally, although each organization had unique circumstances externally to develop the in-house knowledge of Lean imple-

that created a desire to improve its process, all faced a similar mentation. Three sites hired Lean experts with backgrounds in

Table 2. Participating hospitals

Hospital Type of Facility Departments with Lean Applied Started Lean

Hotel-Dieu Grace Hospital Regional tertiary care centre ED, MH, CTU, rad, GIM, sterilization, 2005

ortho, pharm

UHN – Toronto General Hospital Quaternary care, research intensive MI, OR, Surgical preadmission, palliative 2005

care, ED, GIM

Five Hills Health Region Saskatchewan Health Region 49 projects 2006

St. Joseph’s Health Centre Catholic community teaching hospital ED, GIM, HR 2006

North York General Hospital Community teaching hospital ED, GIM, MI, infection control, in-patient 2005

ortho

CTU = clinical teaching unit; ED = emergency department; GIM = general internal medicine; HR = human resources; MH = mental health; MI = medical imaging; OR = operating room; ortho = orthopedics;

pharm = pharmacy; rad = radiology; UHN = University Health Network.

Healthcare Quarterly Vol.12 No.3 2009 31

Leading Lean: A Canadian Healthcare Leader’s Guide Ben Fine et al.

manufacturing, retail or service industries. In contrast, Hotel- we do not devote much attention here to change in general.

Dieu Grace chose to train its Lean-leading staff at the University However, several important steps in the Lean implementation

of Michigan’s Lean healthcare course. process, also addressed in that earlier article (Golden 2006),

While “classroom” experiences, seminars and simulations are especially noteworthy. Among these is the need to identify

are useful starting points, our interviewees reported that Lean and support a Lean change leader who possesses those quali-

is ultimately learned through hands-on experience. Each site ties found in other successful “change agents” (e.g., technical

employed consultants to act as guides through the early stages skills, credibility, personal commitment and broad support in

of Lean implementation. The consultants helped set objectives the organization).

for the Lean initiative, determine tactics and facilitate the first The leaders who championed Lean in the five organizations

mapping sessions. we studied held varied titles and responsibilities (CEO, vice-

All the hospitals attempted to transform external expertise to president or director) (Table 3). Each of these change agents

internal knowledge, but hospitals that used consultants with a kept Lean on the agenda, provided vision and inspiration and

focus on Lean reported greater progress than those that employed removed barriers for managers and front-line workers.

generalist consultants. (In our study, four different consulting Assigning responsibility for driving the work of Lean –

firms provided advice to the five hospitals.) In contrast, non- planning and execution – appears to be a critical decision for the

teaching-oriented consultants delivered one-time changes, but organization. In two cases, dedicated Lean leadership roles were

the initiative seemed to lose momentum upon their exit. Thus, established: (1) Hotel-Dieu Grace trained a LEA(R)N coordi-

consultants with proven experience in teaching Lean are critical nator to manage Lean (Hotel Dieu Grace labels it “LEA(R)N”

to success. For Lean to be sustainable, it is important to live to promote the continuous learning aspect of Lean); and (2) Five

by Lao Tzu’s dictum, “Give someone a fish, feed them for a Hills’ Lean expert, Schattenkirk, currently leads and manages

day; teach someone to fish, feed them for a lifetime.” This is the implementation of Lean across 49 projects in Five Hills. At

akin to Ontario’s recent coaching-teams initiatives in critical the other hospitals, Lean was built into existing responsibili-

and perioperative care (Sherrard et al. 2009) in which existing ties. UHN housed its Lean leadership in the project manage-

expertise in the system is leveraged to other organizations. ment office, hiring Lean experts to manage projects under a

Leading

In an earlier article in Figure 3. Four stages of leading change

Healthcare Quarterly (Golden

2006), one of us presented a ��������� ��������� ����������� ����������

model for organizing complex �������������������������

change efforts in healthcare ������� ������������������

organizations (Figure 3). ���������������� ����������������������������� ���������

That model suggested that ��������������������������� ���������������������������� ������������������

the successful implementa- ��������� ������������������ �������������������

tion of complex changes

in healthcare organizations

(e.g., the implementation �������

��������� ������ ���������

�������

of Lean) typically proceeds ������� ��������� ���

through four stages: (1) ��� ���������� �������

��������������

����� ������

determining the desired end ���������

state, (2) assessing readiness

for change, (3) broadening

�����������������������������������������

organizational support and ������������������������ ���������������

organizational re-design and ��������������������������������� �����������

(4) reinforcing and sustaining ������������������������� ������������

���������

change. ���������������

Because the present article ��������������������

focuses more on the specific

task of implementing Lean HRM = human resources management.

than the common challenges Source: Golden (2006).

of change management,

32 Healthcare Quarterly Vol.12 No.3 2009

Ben Fine et al. Leading Lean: A Canadian Healthcare Leader’s Guide

Table 3. Key decisions of early Lean deployment demonstrating various approaches to Lean

Hospital Who Led the Who Drove Work? How Was Crisis or Lever First Value First Win Objective

Change? Knowledge Stream

or Expertise Mapping

Acquired?

HDGH EVP LEA(R)N coordinator Training, ED in newspaper Portering ED Reduce ED

consultant wait times

UHN PMO senior PMO Hire CEO’s Bullet rounds ED-GIM Reduce ED

manager consultant transformation (GIM) wait times

agenda leveraged

to introduce Lean

St. Joseph’s Former VP, now Manager of access Consultant VP challenge ED admit and ED-GIM Patient safety

CEO services discharge

processes

FHHR CEO, QI Lean expert Hire Provincial ED flow ED Change in

consultant government culture

brought CEO to see

Lean at VMMC

NYGH VP Lean deployment Hire SARS outbreak ED-GIM ED-GIM Move patient

leader chaired Flow consultant and subsequent safety and

Steering Committee leadership quality

transformation agenda

CEO = chief executive officer; ED = emergency department; EVP = executive vice-president; FHHR = Five Hills Health Region; GIM = general internal medicine; HDGH = Hotel-Dieu Grace Hospital; NYGH

= North York General Hospital; PMO = project management office; SARS = severe acute respiratory syndrome; QI = quality improvement; UHN = University Health Network; VMMC = Virginia Mason

Medical Centre; VP = vice-president.

director. St Joseph’s appointed a manager of access services from manage the Lean implementation. In cases where an executive

the internal medicine floor to lead Lean. Lean at North York champion was present but lacked a Lean expert, projects stalled.

General Hospital was led by the director of quality. Each of the At hospitals where Lean experts were present but the executive

leaders who drove the Lean work had varying degrees of Lean was not fully bought in, Lean was limited in its scope. Only

understanding; but in all cases, they had ready access to Lean when both champions were committed and involved did the

experts or consultants. diffusion and sharing of implementation responsibility occur

Two leadership lessons emerge from these five cases. First, and result in the best outcomes.

when the CEO was fully engaged in the initiative and worked

closely with the Lean leaders, the Lean initiative spread across Challenges and Additional Lessons Learned

the organization more quickly. On the other hand, if the change Each of the five organizations studied here characterized their

agent was a director, the change tended to be limited to his or her Lean experience as a “success.” As with hospitals in the United

span of influence (creating what could be called a Lean “ghetto”). States, United Kingdom and Australia, mentioned above,

While the Lean project was important in every organization we Canadian sites reported decreased emergency wait times,

studied, we suggest that the highest probability of broad success decreased patient length of stay, improved operating room usage,

comes when senior leadership is fully behind the change. more radiology procedures per time period and better infection

Second, and also consistent with earlier change research, we control outcomes. (Some of the results have been previously

believe that the organizations that achieved the greatest results described in recent articles in Healthcare Quarterly (Adamson

did so because they not just one but two champions leading the and Kwolek 2008; MacLeod et al. 2008). However, leaders of

way: A true executive champion at the top of the organization the Lean initiatives also experienced several ongoing challenges

to provide inspiration, and a Lean expert to provide advice and as they aimed to implement a sustainable Lean culture. As a

Healthcare Quarterly Vol.12 No.3 2009 33

Leading Lean: A Canadian Healthcare Leader’s Guide Ben Fine et al.

guide for leaders implementing Lean, typical challenges are need not involve rewards other than the removal of obstacles to

described below, along with some tactics that were successfully the work of healthcare professionals.

employed to address them.

Challenge of Sustainability

Staff Concern about Jobs As with any change initiative, the Lean initiative is challenging

Staff are concerned that Lean means cutting jobs. This fear needs to sustain. To address this, Lean must first be treated as a long-

to be addressed up front. Hotel-Dieu Grace faced this challenge term commitment. Five Hills speaks of Lean as a 50-year project.

acutely. With its community tied to automotive manufacturers, Establishing its longevity is important for sustaining the change.

Hotel-Dieu Grace staff had been warned about Lean systems Second, the cultural penetration of Lean concepts must be made

– they mean job cuts. In order to counter this myth strongly a primary aim of the initiative. The principles must be taught to

and firmly, Hotel-Dieu Grace established a core rule of Lean: those who will practise it. Those who truly understand Lean will

no jobs are lost because of Lean. This rule protected the interests see its value and begin to apply it to their work; their actions and

of staff, allayed concerns and provided freedom for the staff to news of their successes will spread the idea. All of the hospitals

be creative. described a point – a “tipping point” – at which Lean leaders no

longer had to “push” Lean ideas out to staff. Instead, staff started

Flavour of the Month to “pull” Lean and demand it for themselves. For example, Five

Staff believe Lean is the flavour of the month. In the shadow Hills has a regular Rapid Access Process Improvement Team

of other failed process improvement initiatives, Lean may (RAPIT) team that introduces Lean in small bursts on three

face intense skepticism. However, Lean differs in the way it consecutive Tuesdays. Third, Lean must feel like a natural part

engages front-line staff. Front-line workers develop ideas and of day-to-day operations, not an isolated initiative. For example,

make changes rather than having process changes imposed on kaizen events are held regularly on the third week of each month

them from above. Two effective tactics used by the hospitals at North York General Hospital to maintain a sense of rhythm.

to confront this challenge were demonstrating results from Finally, results must be demonstrated.

elsewhere and having senior-level leaders speak in terms of years

of commitment to Lean. Negative Connotations

Lean language may evoke negative images of shedding jobs,

Slow Engagement trimming fat and aiming for ruthless efficiency. Five Hills

Physicians are slow to engage. All five hospitals found it diffi- labelled the initiative “Pursuing Excellence,” emphasizing the

cult to get physicians “in the room” to plan improvements. The kaizen continuous pursuit of perfection (like Toyota’s Lexus

reasons for the lack of physician engagement include a substan- brand). As mentioned earlier, Hotel Dieu Grace labels it

tial opportunity cost because of fee-for-service payment schemes “LEA(R)N @ HDGH” as a way of promoting the continuous

and cultural barriers. learning aspect of Lean in appealing to staff.

One way hospitals have engaged physicians is by paying

them, to make it worth their time. Another is more creative: Future of Care: Aligning Delivery by Value Stream

pick an issue of key concern to physicians and deliver results along the Patient Journey

to build physician interest and faith in the Lean initiative. For Lean hospitals look at the delivery of healthcare from a new

example, a physician may be frustrated by time wasted looking perspective. Instead of organizing a hospital by function –

for a central line kit in the storage room. Performing a Lean wrought with barriers, leading to waste and repetition – there

initiative to reduce waste of motion using Lean tools will is the opportunity to arrange delivery by value stream, from

demonstrate the value of the Lean process, even in this local- arrival to departure. According to LEA(R)N coordinator Nicki

ized case, thus increasing the likelihood for greater subsequent Schmidt at Hotel-Dieu Grace, “We don’t serve patients of 5

involvement. South, 6 East or the Emergency Department. We are here to

More generally, change leaders need to address the “WIFM” deliver care across boundaries and silos along value streams. That

question (“What’s in it for me?”). In an age of shrinking requires us to look at where we are providing value according

resources and increasing demand, purchasing support from to the patient, and that opens up a whole new way of thinking

physicians or anyone else is problematic. Thus, reframing of and ways to improve care.”

opportunities needs to occur. Rather than buying support, for We can imagine that patients of the future will enter into

instance, Lean initiatives may promise the reward of reducing a specific value stream (e.g. medicine-short stay, surgery-long

the bottlenecks that physicians have been grousing about for stay). The hospital will add value at every step of the way, from

years. In all cases, WIFM must be answered; but the solution entrance to discharge, and every staff member will be empow-

34 Healthcare Quarterly Vol.12 No.3 2009

Ben Fine et al. Leading Lean: A Canadian Healthcare Leader’s Guide

Royal Bolton Hospital. 2009. Bolton Improving Care System (BICS)

ered to eliminate any wasteful activity. – Using Lean Methodology. Bolton, England: Author. http://www.

This cross-functional approach to delivering value is how boltonhospitals.nhs.uk/bics/default.html (retrieved April 10, 2009)

Toyota builds cars and beats its competitors – in quality, product Sherrard, H., J. Trypuc and A. Hudson. 2009. “The Use of Coaching

development time and profit. It also provides insights into how to Improve Peri-operative Efficiencies: The Ontario Experience.”

we can face our current challenges in healthcare: remove waste Healthcare Quarterly 12(1): 48–75.

to improve the quality of patient care and increase the number Spear, S.J. 2005. “Fixing Health Care from the Inside, Today.” Harvard

of patients we serve, all while reducing costs and the time Business Review 83(9): 78–91.

patients wait. Thompson, D.N., G.A. Wolf and S.J. Spear. 2003. “Driving

The first step on a Lean journey begins by experiencing Lean Improvement in Patient Care: Lessons from Toyota.” Journal of Nursing

Administration 33(11): 585–95.

in action. All you have to lose is the muda.

Womack, J.P and D.T. Jones. 2003. Lean Thinking: Banish Waste and

Create Wealth in Your Corporation. New York, NY: Free Press.

Bibliography

Adamson, B. and S. Kwolek. 2008. “Strategy, Leadership and Change: Womack, J.P. and D.T. Jones. 2005. Lean Solutions: How Companies

The North York General Hospital Transformation Journey.” Healthcare and Customers Can Create Value and Wealth Together. New York, NY:

Quarterly 11(3): 50–53. Free Press.

Ben-Tovim, D.I., J.E. Bassham, D. Bolch, M.A. Martin, M. Dougherty Womack, J.P., D. Roos and D. Jones. 1990. The Machine That Changed

and M. Szwarcbord. 2007. “Lean Thinking across a Hospital: the World. New York, NY: Rawson Associates.

Redesigning Care at the Flinders Medical Centre.” Australian Health

Review 31(1): 10–15.

Bush, R.W. 2007. “Reducing Waste in US Health Care Systems.” About the Authors

Journal of the American Medical Association 297(8): 871–74. Ben Fine, SM, is a fellow at the Centre for Innovation in Complex

Care at University Health Network (UHN) and is a medical student

Foster, R. 2007. “Windsor Regional Hospital Emergency Department

Revolutionized.” Hospital News August: 1, 8. Retrieved April 8, 2009. in the Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, in Toronto,

<http://www.hospitalnews.com/content/magazines/Aug07/HN_ Ontario. He also holds a graduate degree in engineering from

August07.pdf>. MIT.

Golden, B. 2006. “Change: Transforming Healthcare Organizations.” Brian Golden, PhD, is the Sandra Rotman Chaired Professor

Healthcare Quarterly 10(Special Issue): 10–19. of Health Sector Strategy at The University of Toronto and

The University Health Network, and a professor of strategic

Hollingsworth, J.C., C.D. Chisholm, B.K. Giles, W.H. Cordell and

D.R. Nelson. 1998. “How Do Physicians and Nurses Spend Their management at the Rotman School of Management, The

Time in the Emergency Department?” Annals of Emergency Medicine University of Toronto. He is the Executive Director of the

31(1): 87–91. Collaborative for Health Sector Strategy and, since 2005, has

been Board Chair of the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences.

Institute for Healthcare Improvement. 2005. Going Lean in Health Care (bgolden@rotman.utoronto.ca)

(IHI Innovation Series White Paper). Cambridge, MA: Author. http://

www.ihi.org/IHI/Results/WhitePapers/GoingLeaninHealthCare.htm Rosemary Hannam, MBA, is the manager for research and

(retrieved August 22, 2007) operations at the Collaborative for Health Sector Strategy based

Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. at the Rotman School of Management.

2006. Doing More with Less: Lean Thinking and Patient Safety in Health Dante J. Morra, MD, MBA, FRCP(C), is the medical director of

Care. Ed. Porche, R. A. Oakbrook Terrace, IL. the Centre for Innovation in Complex Care at UHN, the director

Kim, C.S., D.A. Spahlinger, J.M. Kin and J.E. Billi. 2006. “Lean Health of the Clinical Teaching Unit at the Toronto General Hospital,

Care: What Can Hospitals Learn from a World-Class Automaker?” Toronto, Ontario, and an associate of the Collaborative for Health

Journal of Hospital Medicine 1(3): 191–99. Sector Strategy based at the Rotman School of Management. Dr.

Laing, K. and K. Baumgartner. 2005. “Implementing ‘Lean’ Principles Morra can be contacted at 416-340-3530, by fax at 416-595-5826

to Improve the Efficiency of the Endoscopy Department of a or by e-mail at dante.morra@utoronto.ca.

Community Hospital: A Case Study.” Gastroenterology Nursing 28(3):

210–15.

Lummus, R.R., R.J. Vokurka and B. Rodeghiero. 2006. “Improving

Quality through Value Stream Mapping: A Case Study of a Physicians

Clinic.” Total Quality Management and Business Excellence 17(8):

1063–75.

MacLeod, H., B. Bell, K. Deane and C. Baker. 2008. “Creating

Sustained Improvements in Patient Access and Flow: Experiences from

Three Ontario Healthcare Institutions.” Healthcare Quarterly 11(3):

38–49.

May, M.E. 2007. The Elegant Solution: Toyota’s Formula for Mastering

Innovation. New York, NY: Free Press.

Healthcare Quarterly Vol.12 No.3 2009 35

You might also like

- Emcee King & QueenDocument8 pagesEmcee King & QueenMaryHazelClaveBeniga100% (10)

- Harvard Case Study - AccountingDocument3 pagesHarvard Case Study - AccountingSuman Saurabh MohantyNo ratings yet

- Applying Lean and Six Sigma To Your Dermatology PracticeDocument7 pagesApplying Lean and Six Sigma To Your Dermatology PracticedrustagiNo ratings yet

- Kaizen Continuous ImprovementDocument4 pagesKaizen Continuous ImprovementPradeep NarendiranNo ratings yet

- Quality Circles and Teams-Tqm NotesDocument8 pagesQuality Circles and Teams-Tqm NotesStanley Cheruiyot100% (1)

- Lean Done Right: Achieve and Maintain Reform in Your Healthcare OrganizationFrom EverandLean Done Right: Achieve and Maintain Reform in Your Healthcare OrganizationNo ratings yet

- The Tracking Shot in Kapo Serge Daney Senses of CinemaDocument22 pagesThe Tracking Shot in Kapo Serge Daney Senses of CinemaMarcos GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Blooms Taxonomy and Costas Level of QuestioningDocument6 pagesBlooms Taxonomy and Costas Level of QuestioningChris Tine100% (1)

- October 2016 Practice PerfectDocument2 pagesOctober 2016 Practice PerfectNaresh SapoliaNo ratings yet

- 196-1584526128 LeanhospitalDocument8 pages196-1584526128 LeanhospitalDharm Veer RathoreNo ratings yet

- Social Science & Medicine: Zoe J. Radnor, Matthias Holweg, Justin WaringDocument8 pagesSocial Science & Medicine: Zoe J. Radnor, Matthias Holweg, Justin WaringOrfani Valencia MenaNo ratings yet

- Lean Principles in Healthcare: An Overview of Challenges and ImprovementsDocument6 pagesLean Principles in Healthcare: An Overview of Challenges and ImprovementsJULIANANo ratings yet

- Core ConceptsDocument6 pagesCore Conceptsnagendra_6391No ratings yet

- Lean Healthcare: Enhancing the Patient Care Process while Eliminating Waste and Lowering CostsFrom EverandLean Healthcare: Enhancing the Patient Care Process while Eliminating Waste and Lowering CostsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Lean ManagmentDocument20 pagesLean Managmentفيصل الاعرجNo ratings yet

- CMA Projet Report Group5Document14 pagesCMA Projet Report Group5anon_218438845No ratings yet

- The Application of Lean in Healthcare: Exploratory PaperDocument40 pagesThe Application of Lean in Healthcare: Exploratory PaperSaraNo ratings yet

- 7 Wastes of Lean in HealthcareDocument5 pages7 Wastes of Lean in HealthcarerheaNo ratings yet

- Quality Control and The Practice of ClinDocument7 pagesQuality Control and The Practice of ClinfranciscoNo ratings yet

- Quality Gurus and Their ContributionDocument17 pagesQuality Gurus and Their ContributionFayis FYSNo ratings yet

- Production and Operation ManagementDocument49 pagesProduction and Operation ManagementIrem AàmarNo ratings yet

- MQA Lab CepDocument19 pagesMQA Lab CepShaffan AbbasiNo ratings yet

- Process Improvement in A Radiology Department: Hatice Camgoz-Akdag and Tu Ğçe BeldekDocument12 pagesProcess Improvement in A Radiology Department: Hatice Camgoz-Akdag and Tu Ğçe BeldekAditya ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Lean Dan 5S Pada Bidang Jasa (Healthcare) PDFDocument9 pagesLean Dan 5S Pada Bidang Jasa (Healthcare) PDFNisaa RahmiNo ratings yet

- TQM Goals and ConceptsDocument5 pagesTQM Goals and ConceptsXavier Scarlet IVNo ratings yet

- Lean Thinking NHSDocument28 pagesLean Thinking NHSHarish VenkatasubramanianNo ratings yet

- Value Stream Mapping CaseDocument13 pagesValue Stream Mapping Casesteve.steinNo ratings yet

- All-Wharton-2009-Rethinking Lean Beyond The Shop Floor PDFDocument18 pagesAll-Wharton-2009-Rethinking Lean Beyond The Shop Floor PDFVishnupriya SharmaNo ratings yet

- Kaizen PDFDocument3 pagesKaizen PDFcs_harsha274280No ratings yet

- Introduction To Total Quality Management: Who Is A Quality Guru?Document9 pagesIntroduction To Total Quality Management: Who Is A Quality Guru?Vaishnavi VaishuNo ratings yet

- Continuous Improvement Strategy: A Learning ApproachDocument11 pagesContinuous Improvement Strategy: A Learning ApproachAdas PapartisNo ratings yet

- Articulo Valido - Principios LEAN LABDocument18 pagesArticulo Valido - Principios LEAN LABFernando Berrospi GarayNo ratings yet

- Effects of Lean Six Sigma in HealthcareDocument6 pagesEffects of Lean Six Sigma in HealthcareYou YouNo ratings yet

- Lean Abstract PDFDocument19 pagesLean Abstract PDFmammutbalajiNo ratings yet

- Uva-Dare (Digital Academic Repository) : Lean Six SigmaDocument9 pagesUva-Dare (Digital Academic Repository) : Lean Six SigmaLuisGutierrezNo ratings yet

- Mistake Proofing HealthcareDocument8 pagesMistake Proofing HealthcareLuis Luchini FernandezNo ratings yet

- Lean Manufacturing Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesLean Manufacturing Literature Reviewea86yezd100% (1)

- Chapter 20Document41 pagesChapter 20Amer RahmahNo ratings yet

- Lean Briefing1912007311331Document13 pagesLean Briefing1912007311331Jorge CardosoNo ratings yet

- 10 - Chapter 3 PDFDocument70 pages10 - Chapter 3 PDFRaghuram Vadiboyena VNo ratings yet

- QI and PDSA Self Learning Packet PA PDFDocument44 pagesQI and PDSA Self Learning Packet PA PDFReli GiusmanNo ratings yet

- Mas YAF (1) TranslationDocument8 pagesMas YAF (1) Translationsaladass 2No ratings yet

- Al Araidah2010Document8 pagesAl Araidah2010jf.leungyanNo ratings yet

- Resumo Alargado Sofia CarvalhoDocument10 pagesResumo Alargado Sofia CarvalhoPatricio Arancibia OrellanaNo ratings yet

- What Is QualityDocument8 pagesWhat Is QualitydzulkormNo ratings yet

- Task#20Document3 pagesTask#20ouia iooNo ratings yet

- Principles and Philosophies of Quality Management: Deming'S Contributions BiographicalDocument15 pagesPrinciples and Philosophies of Quality Management: Deming'S Contributions BiographicalAlbert MervinNo ratings yet

- Lecture 2 Quality AdvocatesDocument71 pagesLecture 2 Quality AdvocatesDOn Ad0% (1)

- Lean Six SigmaDocument8 pagesLean Six Sigma_srobert_No ratings yet

- A Comparative Analysis of Lean Practices and Performance in TheDocument17 pagesA Comparative Analysis of Lean Practices and Performance in TheDanilo Martin Tuppia ReyesNo ratings yet

- Agile Development As A Change Management Approach in Healthcare Innovation ProjectsDocument16 pagesAgile Development As A Change Management Approach in Healthcare Innovation ProjectsAmR ZakiNo ratings yet

- AdvancedTopic OECDocument13 pagesAdvancedTopic OECNoureddine ait el hajNo ratings yet

- Total Quality ImprovementDocument21 pagesTotal Quality ImprovementMar DiyanNo ratings yet

- Kaizen - The Many Ways For Getting BetterDocument6 pagesKaizen - The Many Ways For Getting Betterfahrie_manNo ratings yet

- How Lean Can improve Healthcare? A Brief Guide on Eliminating Waste and Identifying Areas for Improvement: Toyota Production System ConceptsFrom EverandHow Lean Can improve Healthcare? A Brief Guide on Eliminating Waste and Identifying Areas for Improvement: Toyota Production System ConceptsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- TQM Legacy of Quality Gurus and Their Theoretical ContributionsDocument18 pagesTQM Legacy of Quality Gurus and Their Theoretical ContributionsAhmadTalibNo ratings yet

- Implementation of The Lean Six Sigma Framework in Non-Profit Organisations A Case StudyDocument18 pagesImplementation of The Lean Six Sigma Framework in Non-Profit Organisations A Case StudyYolandaNo ratings yet

- Total Quality Management PhilosophyDocument34 pagesTotal Quality Management PhilosophyAtharva GuptaNo ratings yet

- A3 Process - A Pragmatic Problem-Solving Technique For Process Improvement in Health CareDocument11 pagesA3 Process - A Pragmatic Problem-Solving Technique For Process Improvement in Health CareNoé HumbertoNo ratings yet

- TQM Assignment 1Document4 pagesTQM Assignment 1hg plNo ratings yet

- Managing in Reverse: The 8 Steps to Optimizing Performance for LeadersFrom EverandManaging in Reverse: The 8 Steps to Optimizing Performance for LeadersNo ratings yet

- How to Manage Future Costs and Risks Using Costing and MethodsFrom EverandHow to Manage Future Costs and Risks Using Costing and MethodsNo ratings yet

- FSnotes 13 To 16Document11 pagesFSnotes 13 To 16Suman Saurabh MohantyNo ratings yet

- Financial Services NotesDocument16 pagesFinancial Services NotesSuman Saurabh MohantyNo ratings yet

- What Is Sustainable DevelopmentDocument14 pagesWhat Is Sustainable Developmentmaverick987No ratings yet

- Driving Indian ConsumptionDocument28 pagesDriving Indian ConsumptionSuman Saurabh MohantyNo ratings yet

- PCLN - Priceline Group Stock Interactive Chart PDFDocument1 pagePCLN - Priceline Group Stock Interactive Chart PDFSuman Saurabh MohantyNo ratings yet

- ETHICS IN PRACTICE: Parable of the SadhuDocument3 pagesETHICS IN PRACTICE: Parable of the SadhuSuman Saurabh MohantyNo ratings yet

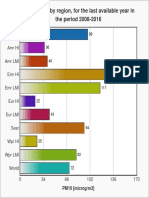

- PM10 air pollution levels by global region 2008-2016Document1 pagePM10 air pollution levels by global region 2008-2016Suman Saurabh MohantyNo ratings yet

- GoingLeaninHealthCareWhitePaper 3 PDFDocument24 pagesGoingLeaninHealthCareWhitePaper 3 PDFyaswanthbhuNo ratings yet

- Project Planning and SchedulingDocument52 pagesProject Planning and SchedulingBatkhishig100% (1)

- Titan Company (TITIND) : Jewellery Segment Growth Expected To SustainDocument11 pagesTitan Company (TITIND) : Jewellery Segment Growth Expected To SustainSuman Saurabh MohantyNo ratings yet

- Introductory MacroeconomicsDocument106 pagesIntroductory MacroeconomicsHardik Gupta50% (4)

- Pricing PredicamentDocument3 pagesPricing PredicamentSuman Saurabh MohantyNo ratings yet

- Exercise 1: Simple I/O Using Keil SimulatorDocument3 pagesExercise 1: Simple I/O Using Keil SimulatorSuman Saurabh MohantyNo ratings yet

- Online Banking Application FormDocument2 pagesOnline Banking Application FormAnkit SahuNo ratings yet

- EMR SchemeDocument44 pagesEMR SchemeSuman Saurabh MohantyNo ratings yet

- Open Banking'S Next Wave: Perspectives From Three Fintech CeosDocument12 pagesOpen Banking'S Next Wave: Perspectives From Three Fintech CeosSuman Saurabh MohantyNo ratings yet

- Hilton CH 10 Select SolutionsDocument25 pagesHilton CH 10 Select Solutionsmanthana9950% (2)

- Embedded Systems - ARM Programming TechniquesDocument258 pagesEmbedded Systems - ARM Programming TechniquesSamir KhNo ratings yet

- Exercise 2: Observing Mode Switching Using A Software InterruptDocument3 pagesExercise 2: Observing Mode Switching Using A Software InterruptSuman Saurabh MohantyNo ratings yet

- LP DegeneracyDocument2 pagesLP DegeneracySuborno AdityaNo ratings yet

- 10 1 1 69Document42 pages10 1 1 69Suman Saurabh MohantyNo ratings yet

- Aichi Biodiversity TargetsDocument3 pagesAichi Biodiversity TargetsSuman Saurabh MohantyNo ratings yet

- L 293 DDocument6 pagesL 293 DSuman Saurabh MohantyNo ratings yet

- VCO1Document3 pagesVCO1Suman Saurabh MohantyNo ratings yet

- 01225959Document6 pages01225959Suman Saurabh MohantyNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Field Programmable Gate Array-Based Kalman Filter ArcDocument123 pagesAnalysis of Field Programmable Gate Array-Based Kalman Filter ArcSuman Saurabh MohantyNo ratings yet

- Ued 495-496 Kelley Shelby Personal Teaching PhilosophyDocument6 pagesUed 495-496 Kelley Shelby Personal Teaching Philosophyapi-295041917No ratings yet

- Core 13 UcspDocument3 pagesCore 13 UcspJanice DomingoNo ratings yet

- Kolkata Thika Tenancy ActDocument15 pagesKolkata Thika Tenancy Actadv123No ratings yet

- 6000 EN 00 04 Friction PDFDocument30 pages6000 EN 00 04 Friction PDFM Ferry AnwarNo ratings yet

- Suretyship and Guaranty CasesDocument47 pagesSuretyship and Guaranty CasesFatima SladjannaNo ratings yet

- Music in The United KingdomDocument33 pagesMusic in The United KingdomIonut PetreNo ratings yet

- Reading Comprehension StrategiesDocument67 pagesReading Comprehension StrategiesKumar ChetanNo ratings yet

- ISO 9001:2015 certified Fargo Courier with over 100 branchesDocument1 pageISO 9001:2015 certified Fargo Courier with over 100 branchesMuchiri NahashonNo ratings yet

- Meaning and Nature of MathematicsDocument3 pagesMeaning and Nature of MathematicsCyril KiranNo ratings yet

- 21st Century Literature Grade 11 21st Century Literature Grade 11 21st Century Literature Grade 11 CompressDocument75 pages21st Century Literature Grade 11 21st Century Literature Grade 11 21st Century Literature Grade 11 Compressdesly jane sianoNo ratings yet

- Sacred SpaceDocument440 pagesSacred SpaceAbdiel Cervantes HernandezNo ratings yet

- Tañada v. Angara Case DigestDocument12 pagesTañada v. Angara Case DigestKatrina PerezNo ratings yet

- UNIT 1 - Revision: HFFFFFDocument3 pagesUNIT 1 - Revision: HFFFFFRedDinoandbluebird ChannelTMNo ratings yet

- 3 Week Lit 121Document48 pages3 Week Lit 121Cassandra Dianne Ferolino MacadoNo ratings yet

- Partition SuitDocument2 pagesPartition SuitJyoti ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- EBM CasesDocument1 pageEBM CasesdnaritaNo ratings yet

- GEO123 Worksheet 8Document4 pagesGEO123 Worksheet 8Hilmi HusinNo ratings yet

- Book Review of Conceptualising Integration in CLIL and Multilingual EducationDocument5 pagesBook Review of Conceptualising Integration in CLIL and Multilingual EducationAigul AitbaevaNo ratings yet

- MC Sampler Pack PDFDocument195 pagesMC Sampler Pack PDFVedaste Ndayishimiye100% (2)

- Gr.8 Ch.5 Chapter Review AnswerDocument10 pagesGr.8 Ch.5 Chapter Review Answerson GokuNo ratings yet

- American Ceramic: SocietyDocument8 pagesAmerican Ceramic: SocietyPhi TiêuNo ratings yet

- Edu 233Document147 pagesEdu 233Abdul Ola IBNo ratings yet

- St. John, Isaac Newton and Prediction of MedicanesDocument6 pagesSt. John, Isaac Newton and Prediction of MedicanesMarthaNo ratings yet

- Whats New SAP HANA Platform Release Notes enDocument66 pagesWhats New SAP HANA Platform Release Notes enJohn Derteano0% (1)

- Theories of StressDocument15 pagesTheories of Stressyared desta100% (1)

- Mock Test 2Document8 pagesMock Test 2Niranjan BeheraNo ratings yet

- Philippine Cartoons: Political Caricatures of the American EraDocument27 pagesPhilippine Cartoons: Political Caricatures of the American EraAun eeNo ratings yet