Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Safari - 24 Dec 2018 at 11:02 PM PDF

Safari - 24 Dec 2018 at 11:02 PM PDF

Uploaded by

Joy Tuquero Ereno-AriraoCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Contact Number-Regional Prosecutors OfficeDocument16 pagesContact Number-Regional Prosecutors Officeirish kitong100% (2)

- Crim2 Case Digest OngoingDocument35 pagesCrim2 Case Digest OngoingMaria Yolly RiveraNo ratings yet

- CasesDocument37 pagesCasesRaymond AlhambraNo ratings yet

- People Vs AdrianoDocument5 pagesPeople Vs AdrianoMagr Esca100% (1)

- People vs. AdrianoDocument4 pagesPeople vs. AdrianoMj BrionesNo ratings yet

- Crim 2 CasesDocument72 pagesCrim 2 CasesRizza MoradaNo ratings yet

- 3people vs. Adriano, G.R. No. L-477, June 30, 1947 (Treason-Membership in An Organization)Document4 pages3people vs. Adriano, G.R. No. L-477, June 30, 1947 (Treason-Membership in An Organization)aldritzNo ratings yet

- 23.cramer v. United States, 65 Sup. Ct. 918Document6 pages23.cramer v. United States, 65 Sup. Ct. 918NEWBIENo ratings yet

- People v. AdrianoDocument6 pagesPeople v. AdrianoJeremy RolaNo ratings yet

- 0007 - People vs. Adriano 78 Phil. 561, June 30, 1947 PDFDocument6 pages0007 - People vs. Adriano 78 Phil. 561, June 30, 1947 PDFGra syaNo ratings yet

- En Banc: THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. APOLINAR ADRIANO, Defendant-AppellantDocument8 pagesEn Banc: THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. APOLINAR ADRIANO, Defendant-AppellantyassercarlomanNo ratings yet

- 5people V AdrianoDocument7 pages5people V AdrianoNana SanNo ratings yet

- Crim2 A - BDocument62 pagesCrim2 A - BAerith AlejandreNo ratings yet

- People Vs AdrianoDocument2 pagesPeople Vs AdrianoMarie TitularNo ratings yet

- BETEZDocument16 pagesBETEZJose BrinNo ratings yet

- 1 - People vs. Adriano, June 30, 1947Document7 pages1 - People vs. Adriano, June 30, 1947moiNo ratings yet

- People v. Adriano GR No L-477Document2 pagesPeople v. Adriano GR No L-477Ma Stephanie GarciaNo ratings yet

- CRIMINAL LAW 2 Study GuideDocument19 pagesCRIMINAL LAW 2 Study GuideMilcah Aquino ValenciaNo ratings yet

- The People of The Philippines vs. Apolinario Adriano, G.R. No. L-477, June 30, 1947Document2 pagesThe People of The Philippines vs. Apolinario Adriano, G.R. No. L-477, June 30, 1947Hazel EstayanNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law II JurisprudenceDocument25 pagesCriminal Law II JurisprudenceDiane MuegoNo ratings yet

- Crim II DigestDocument60 pagesCrim II DigestAnonymous 659sMW8No ratings yet

- 1st Case AssignmentDocument10 pages1st Case AssignmentRikki Marie PajaresNo ratings yet

- Case DigestDocument4 pagesCase DigestLaurene Ashley Sore-YokeNo ratings yet

- Us Vs - Delos ReyesDocument3 pagesUs Vs - Delos ReyesJam PhotostarNo ratings yet

- People vs. AlarconDocument5 pagesPeople vs. AlarconJames OcampoNo ratings yet

- Annex C NatresDocument7 pagesAnnex C NatresIJ SaavedraNo ratings yet

- 1 Title 1 CompleteDocument22 pages1 Title 1 CompletesgonzalesNo ratings yet

- People Vs PrietoDocument2 pagesPeople Vs PrietoRolando ReubalNo ratings yet

- T01C03 People V Prieto 80 Phil 138Document3 pagesT01C03 People V Prieto 80 Phil 138CJ MillenaNo ratings yet

- Plaintiff-Appellee vs. vs. Accused-Appellant The Solicitor General Manuel B. TomacruzDocument29 pagesPlaintiff-Appellee vs. vs. Accused-Appellant The Solicitor General Manuel B. TomacruzAriel MolinaNo ratings yet

- Treason 11 23Document52 pagesTreason 11 23Bhëdz SavarisNo ratings yet

- US Vs Delos ReyesDocument6 pagesUS Vs Delos ReyesDagul JauganNo ratings yet

- Crim II 20161129Document6 pagesCrim II 20161129Bryan MacabayaNo ratings yet

- The United States vs. Antonio Delos ReyesDocument2 pagesThe United States vs. Antonio Delos Reyesdarwin polidoNo ratings yet

- People v. Cawaling, G.R. No. 157147. April 17, 2009 PDFDocument25 pagesPeople v. Cawaling, G.R. No. 157147. April 17, 2009 PDFJohzzyluck R. MaghuyopNo ratings yet

- 004 People v. Manayao (1947) (Dacillo, C.)Document3 pages004 People v. Manayao (1947) (Dacillo, C.)Cyril H. Llamas100% (1)

- People vs. Alicando: Him Is A New Requirement Imposed by The 1985 Rules On Criminal Procedure. It Implements TheDocument7 pagesPeople vs. Alicando: Him Is A New Requirement Imposed by The 1985 Rules On Criminal Procedure. It Implements TheDi ko alamNo ratings yet

- People Vs Prieto DigestDocument2 pagesPeople Vs Prieto DigestLawrence Y. CapuchinoNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law Ii Digests Compilation 2020Document108 pagesCriminal Law Ii Digests Compilation 2020dnzrck100% (4)

- 1902 PDFDocument384 pages1902 PDFGabriel Canlas AblolaNo ratings yet

- Exigent and Emergency CircumstancesDocument4 pagesExigent and Emergency CircumstancesKleyr De Casa AlbeteNo ratings yet

- Title 1Document11 pagesTitle 1Maria Linda TurlaNo ratings yet

- Crim 2 DigestDocument4 pagesCrim 2 DigestpasmoNo ratings yet

- THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. EDUARDO PRIETO (Alias EDDIE VALENCIA), DefendantDocument6 pagesTHE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. EDUARDO PRIETO (Alias EDDIE VALENCIA), DefendantLawrence Y. CapuchinoNo ratings yet

- Final Case Digest For CrimDocument108 pagesFinal Case Digest For CrimBoy Kakak Toki80% (5)

- People V PrietoDocument2 pagesPeople V PrietoJona Phoebe MangalindanNo ratings yet

- Villaflor vs. Summers. 41 Phil. 62, September 08, 1920Document7 pagesVillaflor vs. Summers. 41 Phil. 62, September 08, 1920CassieNo ratings yet

- People vs. Boholst-CaballeroDocument10 pagesPeople vs. Boholst-CaballeroRomy Ian LimNo ratings yet

- Plaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Defendant-Appellant Jose M. Santos First Assistant Solicitor General Reyes Solicitor LacsonDocument6 pagesPlaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Defendant-Appellant Jose M. Santos First Assistant Solicitor General Reyes Solicitor LacsonDuffy DuffyNo ratings yet

- People v. Quiñanola y EscuadroDocument21 pagesPeople v. Quiñanola y EscuadroElmer Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Plaintiff-Appellee Accused-Appellant The Solicitor General Manuel B. TomacruzDocument33 pagesPlaintiff-Appellee Accused-Appellant The Solicitor General Manuel B. TomacruzAndrei Anne PalomarNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law 2 DigestsDocument16 pagesCriminal Law 2 DigestsMces ChavezNo ratings yet

- Treason Cases Digested (Crim Law 2)Document5 pagesTreason Cases Digested (Crim Law 2)Jacob Castro100% (2)

- Cases - National SecurityDocument191 pagesCases - National SecurityLENNY ANN ESTOPINNo ratings yet

- People v. Camerino, 108 Phil. 79Document2 pagesPeople v. Camerino, 108 Phil. 79JNo ratings yet

- People vs. LandichoDocument41 pagesPeople vs. LandichoAira Mae P. LayloNo ratings yet

- 3 US V Lagnason PDFDocument26 pages3 US V Lagnason PDFlianne_rose_1100% (1)

- People'S Journal Et. Al. vs. Francis Thoenen (Freedom of Expression, Libel and National Security)Document4 pagesPeople'S Journal Et. Al. vs. Francis Thoenen (Freedom of Expression, Libel and National Security)Parity Lugangis Nga-awan IIINo ratings yet

- Report of the Decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, and the Opinions of the Judges Thereof, in the Case of Dred Scott versus John F.A. Sandford December Term, 1856.From EverandReport of the Decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, and the Opinions of the Judges Thereof, in the Case of Dred Scott versus John F.A. Sandford December Term, 1856.No ratings yet

- PFR CasesDocument24 pagesPFR CasesJovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- Credits Bar-QDocument34 pagesCredits Bar-QJovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- (G.R. No. 123169. November 4, 1996) DANILO E. PARAS, Petitioner, vs. COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS, Respondent. Resolution Francisco, J.Document57 pages(G.R. No. 123169. November 4, 1996) DANILO E. PARAS, Petitioner, vs. COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS, Respondent. Resolution Francisco, J.Jovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- Sps. Gallent v. VelasquezDocument10 pagesSps. Gallent v. VelasquezJovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- Medical Malpractice: (Torts and Damages)Document20 pagesMedical Malpractice: (Torts and Damages)Jovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- Preference of CreditsDocument9 pagesPreference of CreditsJovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 190810 July 18, 2012 Lorenza C. Ongco, vs. Valeriana Ungco Dalisay, Sereno, JDocument7 pagesG.R. No. 190810 July 18, 2012 Lorenza C. Ongco, vs. Valeriana Ungco Dalisay, Sereno, JJovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- Medical Malpractice: (Torts and Damages)Document8 pagesMedical Malpractice: (Torts and Damages)Jovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- TRANSPODocument27 pagesTRANSPOJovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- Medical Malpractice: (Torts and Damages)Document18 pagesMedical Malpractice: (Torts and Damages)Jovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- December 5, 2017 G.R. No. 217874 OPHELIA HERNAN, Petitioner, The Honorable Sandiganbayan,, Respondent Decision Peralta, J.Document10 pagesDecember 5, 2017 G.R. No. 217874 OPHELIA HERNAN, Petitioner, The Honorable Sandiganbayan,, Respondent Decision Peralta, J.Jovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- Agusan Del Norte v. BalenDocument8 pagesAgusan Del Norte v. BalenJovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- Exconde v. CapunoDocument2 pagesExconde v. CapunoJovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- TORTS 2nd Batch FinalsDocument47 pagesTORTS 2nd Batch FinalsJovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 82248 January 30, 1992 Ernesto Martin, Petitioner, vs. Hon. Court of Appeals and Manila ELECTRIC COMPANY, Respondents. CRUZ, J.Document47 pagesG.R. No. 82248 January 30, 1992 Ernesto Martin, Petitioner, vs. Hon. Court of Appeals and Manila ELECTRIC COMPANY, Respondents. CRUZ, J.Jovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- Pale Canon 20-21Document92 pagesPale Canon 20-21Jovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- Delict Against Petitioner As Employer Arising From The Same Act or Omission of TheDocument5 pagesDelict Against Petitioner As Employer Arising From The Same Act or Omission of TheJovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- Other Code of Commerce Provisions On CaptainsDocument57 pagesOther Code of Commerce Provisions On CaptainsJovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- Training Proposal-ALIVEDocument6 pagesTraining Proposal-ALIVEdarwinNo ratings yet

- Franz Resume UpdatedDocument2 pagesFranz Resume UpdatedKelly ChengNo ratings yet

- History of BongabonDocument5 pagesHistory of BongabonRosel Sarabia50% (2)

- Final Masquerade JS PROM Tricia DuenasDocument32 pagesFinal Masquerade JS PROM Tricia DuenasKrystine TuazonNo ratings yet

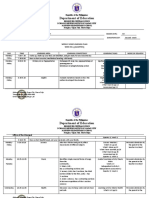

- Workweek Plan Grade 6 Third Quarter Week 2Document15 pagesWorkweek Plan Grade 6 Third Quarter Week 2Lenna Paguio100% (1)

- Travel Order LandbankDocument12 pagesTravel Order LandbankJonel TorresNo ratings yet

- CERTIFICATES by Savanna CunninghamDocument15 pagesCERTIFICATES by Savanna CunninghamPeachy MarianoNo ratings yet

- Hope 2-G11Document11 pagesHope 2-G11Aprille RamosNo ratings yet

- NPS Directory - 2023Document10 pagesNPS Directory - 2023Noemi MejiaNo ratings yet

- Contract of ServiceDocument11 pagesContract of ServiceHazel Dela PeñaNo ratings yet

- Backyard Camping Schedule of ActivitiesDocument9 pagesBackyard Camping Schedule of ActivitiesHazel Dela PeñaNo ratings yet

- Resume G12Document2 pagesResume G12Austin BlackNo ratings yet

- Gabriel2018 ReferenceWorkEntry BureaucraticRedTapeInThePhilipDocument10 pagesGabriel2018 ReferenceWorkEntry BureaucraticRedTapeInThePhilipAnaliza V. MuñozNo ratings yet

- Region 3 Data BaseDocument47 pagesRegion 3 Data BaseCess SexyNo ratings yet

- Final Seminar Maria Carmela R. ArcillaDocument34 pagesFinal Seminar Maria Carmela R. ArcillaKrystine TuazonNo ratings yet

- RDO No. 23A - Talavera, North Nueva EcijaDocument975 pagesRDO No. 23A - Talavera, North Nueva EcijagabbyNo ratings yet

- Participating Site List 108 FNLDocument13 pagesParticipating Site List 108 FNLRussel ZarateNo ratings yet

- Inquiry FormDocument6 pagesInquiry FormJefferson LiwagNo ratings yet

- Action Plan - Work ImmersionDocument10 pagesAction Plan - Work ImmersionAirah De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- PDF History of Gapan City Nueva Ecija - CompressDocument2 pagesPDF History of Gapan City Nueva Ecija - CompressJohnross Anatalio0% (1)

- Do18 2013BDocument7 pagesDo18 2013BarnoldNo ratings yet

- aCTION PLAN IN HEALTHDocument13 pagesaCTION PLAN IN HEALTHCATHERINE FAJARDONo ratings yet

- Art Exhibit (Choi)Document20 pagesArt Exhibit (Choi)ROGEL SONo ratings yet

- Crim2 A - BDocument62 pagesCrim2 A - BAerith AlejandreNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: School Tracking MechanismDocument2 pagesDepartment of Education: School Tracking MechanismDarwin GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Week-2 Quarter 3Document4 pagesWeek-2 Quarter 3Marybeth GutierrezNo ratings yet

- History of Nueva EcijaDocument50 pagesHistory of Nueva EcijaJulius Maderia100% (1)

- RLFI BPI Endorsement SY 2023 2024 For Scholars With NamesDocument8 pagesRLFI BPI Endorsement SY 2023 2024 For Scholars With NamesYOW BiatchNo ratings yet

- Nueva Ecija-Area Based Management Plan For Pampanga River Basin 2014Document17 pagesNueva Ecija-Area Based Management Plan For Pampanga River Basin 2014Margarita AngelesNo ratings yet

Safari - 24 Dec 2018 at 11:02 PM PDF

Safari - 24 Dec 2018 at 11:02 PM PDF

Uploaded by

Joy Tuquero Ereno-AriraoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Safari - 24 Dec 2018 at 11:02 PM PDF

Safari - 24 Dec 2018 at 11:02 PM PDF

Uploaded by

Joy Tuquero Ereno-AriraoCopyright:

Available Formats

Today is Sunday, December 23, 2018

Custom Search

onstitution Statutes Executive Issuances Judicial Issuances Other Issuances Jurisprudence International Legal Resources AUSL Exclusive

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

EN BANC

G.R. No. L-477 June 30, 1947

THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, plaintiff-appellee,

vs.

APOLINARIO ADRIANO, defendant-appellant.

Remedios P. Nufable for appellant.

Assistant Solicitor General Kapunan, Jr., and Solicitor Lacson for appellee.

TUASON, J.:

This is an appeal from a judgment of conviction for treason by the People's Court sentencing the accused to life

imprisonment, P10,000 fine, and the costs.

The information charged:

That between January and April, 1945 or thereabout, during the occupation of the Philippines by the

Japanese Imperial Forces, in the Province of Nueva Ecija and in the mountains in the Island of Luzon,

Philippines, and within the jurisdiction of this Court, the above-named accused, Apolinario Adriano, who is not

a foreigner, but a Filipino citizen owing allegiance to the United States and the Commonwealth of the

Philippines, in violation of said allegiance, did then and there willfully, criminally and treasonably adhere to the

Military Forces of Japan in the Philippines, against which the Philippines and the United States were then at

war, giving the said enemy aid and comfort in the manner as follows:

That as a member of the Makapili, a military organization established and designed to assist and aid militarily

the Japanese Imperial forces in the Philippines in the said enemy's war efforts and operations against the

United States and the Philippines, the herein accused bore arm and joined and assisted the Japanese Military

Forces and the Makapili Army in armed conflicts and engagements against the United States armed forces

and the Guerrillas of the Philippine Commonwealth in the Municipalities of San Leonardo and Gapan,

Province of Nueva Ecija, and in the mountains of Luzon, Philippines, sometime between January and April,

1945. Contrary to Law.

The prosecution did not introduce any evidence to substantiate any of the facts alleged except that of defendant's

having joined the Makapili organization. What the People's Court found is that the accused participated with

Japanese soldiers in certain raids and in confiscation of personal property. The court below, however, said these

acts had not been established by the testimony of two witnesses, and so regarded them merely as evidence of

adherence to the enemy. But the court did find established under the two-witness rule, so we infer, "that the accused

and other Makapilis had their headquarters in the enemy garrison at Gapan, Nueva Ecija; that the accused was in

Makapili military uniform; that he was armed with rifle; and that he drilled with other Makapilis under a Japanese

instructor; . . . that during the same period, the accused in Makapili military uniform and with a rifle, performed duties

as sentry at the Japanese garrison and Makapili headquarters in Gapan, Nueva Ecija;" "that upon the liberation of

Gapan, Nueva Ecija, by the American forces, the accused and other Makapilis retreated to the mountains with the

enemy;" and that "the accused, rifle in hand, later surrendered to the Americans."

Even the findings of the court recited above in quotations are not borne out by the proof of two witnesses. No two of

the prosecution witnesses testified to a single one of the various acts of treason imputed by them to the appellant.

Those who gave evidence that the accused took part in raids and seizure of personal property, and performed

sentry duties and military drills, referred to acts allegedly committed on different dates without any two witnesses

coinciding in any one specified deed. There is only one item on which the witnesses agree: it is that the defendant

was a Makapili and was seen by them in Makapili uniform carrying arms. Yet, again, on this point it cannot be said

that one witness is corroborated by another if corroboration means that two witnesses have seen the accused doing

at least one particular thing, it a routine military chore, or just walking or eating.

We take it that the mere fact of having joined a Makapili organization is evidence of both adherence to the enemy

and giving him aid and comfort. Unless forced upon one against his will, membership in the Makapili organization

imports treasonable intent, considering the purposes for which the organization was created, which, according to the

evidence, were "to accomplish the fulfillment of the obligations assumed by the Philippines in the Pact of Alliance

with the Empire of Japan;" "to shed blood and sacrifice the lives of our people in order to eradicate Anglo-Saxon

influence in East Asia;" "to collaborate unreservedly and unstintedly with the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy in

the Philippines;" and "to fight the common enemies." Adherence, unlike overt acts, need not be proved by the oaths

of two witnesses. Criminal intent and knowledge may be gather from the testimony of one witness, or from the

nature of the act itself, or from the circumstances surrounding the act. (Cramer vs. U.S., 65 Sup. Ct., 918.)

At the same time, being a Makapili is in itself constitutive of an overt act. It is not necessary, except for the purpose

of increasing the punishment, that the defendant actually went to battle or committed nefarious acts against his

country or countrymen. The crime of treason was committed if he placed himself at the enemy's call to fight side by

side with him when the opportune time came even though an opportunity never presented itself. Such membership

by its very nature gave the enemy aid and comfort. The enemy derived psychological comfort in the knowledge that

he had on his side nationals of the country with which his was at war. It furnished the enemy aid in that his cause

was advanced, his forces augmented, and his courage was enhanced by the knowledge that he could count on men

such as the accused and his kind who were ready to strike at their own people. The principal effect of it was no

difference from that of enlisting in the invader's army.

But membership as a Makapili, as an overt act, must be established by the deposition of two witnesses. Does the

evidence in the present case meet this statutory test? Is two-witness requirement fulfilled by the testimony of one

witness who saw the appellant in Makapili uniform bearing a gun one day, another witness another day, and so

forth?

The Philippine law on treason is of Anglo-American origin and so we have to look for guidance from American

sources on its meaning and scope. Judicial interpretation has been placed on the two-witness principle by American

courts, and authoritative text writers have commented on it. We cull from American materials the following excerpts

which appear to carry the stamp of authority.

Wharton's Criminal Evidence, Vol. 3, section 1396, p. 2282, says:

In England the original Statute of Edward, although requiring both witnesses to be to the same overt act, was

held to mean that there might be one witness to an overt act and another witness to another overt act of the

same species of treason; and, in one case it has been intimated that the same construction might apply in this

country. But, as Mr. Wigmore so succinctly observes: "The opportunity of detecting the falsity of the testimony,

by sequestering the two witnesses and exposing their variance in details, is wholly destroyed by permitting

them to speak to different acts." The rule as adopted in this country by all the constitutional provisions, both

state and Federal, properly requires that two witnesses shall testify to the same overt act. This also is now the

rule in England.

More to the point is this statement from VII Wigmore on Evidence, 3d ed., section 2038, p. 271:

Each of the witnesses must testify to the whole of the overt act; or, if it is separable, there must be two

witnesses to each part of the overt act.

Learned Hand, J., in United States vs. Robinson (D.C.S.D., N.Y., 259 Fed., 685), expressed the same idea: "It is

necessary to produce two direct witnesses to the whole overt act. It may be possible to piece bits together of the

overt act; but, if so, each bit must have the support of two oaths; . . .." (Copied as footnote in Wigmore on Evidence,

ante.) And in the recent case of Cramer vs. United States (65 Sup. Ct., 918), decide during the recent World War,

the Federal Supreme Court lays down this doctrine: "The very minimum function that an overt act must perform in a

treason prosecution is that it shows sufficient action by the accused, in its setting, to sustain a finding that the

accused actually gave aid and comfort to the enemy. Every act, movement, deed, and word of the defendant

charged to constitute treason must be supported by the testimony of two witnesses."

In the light of these decisions and opinions we have to set aside the judgment of the trial court. To the possible

objection that the reasoning by which we have reached this conclusion savors of sophism, we have only to say that

the authors of the constitutional provision of which our treason law is a copy purposely made conviction for treason

difficult, the rule "severely restrictive." This provision is so exacting and so uncompromising in regard to the amount

of evidence that where two or more witnesses give oaths to an overt act and only one of them is believed by the

court or jury, the defendant, it has been said and held, is entitled to discharge, regardless of any moral conviction of

the culprit's guilt as gauged and tested by the ordinary and natural methods, with which we are familiar, of finding

the truth. Natural inferences, however strong or conclusive, flowing from other testimony of a most trustworthy

witness or from other sources are unavailing as a substitute for the needed corroboration in the form of direct

testimony of another eyewitness to the same overt act.

The United States Supreme Court saw the obstacles placed in the path of the prosecution by a literal interpretation

of the rule of two witnesses but said that the founders of the American government fully realized the difficulties and

went ahead not merely in spite but because of the objections. (Cramer vs. United States, ante.) More, the rule, it is

said, attracted the members of the Constitutional Convention "as one of the few doctrines of Evidence entitled to be

guaranteed against legislative change." (Wigmore on Evidence, ante, section 2039, p. 272, citing Madison's Journal

of the Federal Convention, Scott's ed., II, 564, 566.) Mr. Justice Jackson, who delivered the majority opinion in the

celebrated Cramer case, said: "It is not difficult to find grounds upon which to quarrel with this Constitutional

provision. Perhaps the farmers placed rather more reliance on direct testimony than modern researchers in

psychology warrant. Or it may be considered that such a quantitative measure of proof, such a mechanical

calibration of evidence is a crude device at best or that its protection of innocence is too fortuitous to warrant so

unselective an obstacle to conviction. Certainly the treason rule, whether wisely or not, is severely restrictive." It

must be remembered, however, that the Constitutional Convention was warned by James Wilson that "'Treason may

sometimes be practiced in such a manner, as to render proof extremely difficult — as in a traitorous correspondence

with an enemy.' The provision was adopted not merely in spite of the difficulties it put in the way of prosecution but

because of them. And it was not by whim or by accident, but because one of the most venerated of that venerated

group considered that "prosecutions for treason were generally virulent.'"

Such is the clear meaning of the two-witness provision of the American Constitution. By extension, the lawmakers

who introduced that provision into the Philippine statute books must be understood to have intended that the law

should operate with the same inflexibility and rigidity as the American forefathers meant.

The judgment is reversed and the appellant acquitted with costs charged de oficio.

Moran, C.J., Feria, Pablo, Perfecto, Bengzon, Briones, Hontiveros, and Padilla, JJ., concur.

Paras, J., concurs in the result.

Separate Opinions

HILADO, J., dissenting:

Being unable to bring myself agree with the majority upon the application of the two-witness rule herein, I am

constrained to dissent.

As I see it, being a member of the Makapili during the Japanese occupation of those areas of the Philippines

referred to in the information, was one single, continuous, and indivisible overt act of the present accused whereby

he gave aid and comfort to the Japanese invaders. That membership was one and the same from the moment he

entered the organization till he was captured. The fact that he was seen on a certain day by one of the state

witnesses being a member of the Makapili, and was seen by another state witness but on a different day being a

member of the same organization, does not mean that his membership on the first day was different or independent

from his membership on the other day — it was the selfsame membership all the way through. A contrary

construction would entail the consequence that the instant defendant, if we are to believe the allegations and proofs

of the prosecution, became or was a member of the Makapili as many times as there were days from the first to the

last.

T.E. Holland defined "acts" in jurisprudence as follows:

Jurisprudence is concerned only with outward acts. An "act" may therefore be defined . . . as "a determination

of will, producing an effect in the sensible world". The effect may be negative, in which case the act is properly

described as a "forbearance". The essential elements of such an act are there, viz., an exercise of the will, an

accompanying state of consciousness, a manifestation of the will. (Webster's New International Dictionary, 2d

ed., unabridged, p. 25.)

There can, therefore, be no question that being a member of the Makapili was an overt act of the accused. And the

fact that no two witnesses saw him being such a member on any single day or on the selfsame occasion does not,

in my humble opinion, work against the singleness of the act, nor does the fact that no two witnesses have testified

to that same overt act being done on the same day or occasion argue against holding the two-witness rule having

been complied with.

My view is that, the act being single, continuous and indivisible, at least two witnesses have testified thereto

notwithstanding the fact that one saw it on one day and the other on another day.

The Lawphil Project - Arellano Law Foundation

You might also like

- Contact Number-Regional Prosecutors OfficeDocument16 pagesContact Number-Regional Prosecutors Officeirish kitong100% (2)

- Crim2 Case Digest OngoingDocument35 pagesCrim2 Case Digest OngoingMaria Yolly RiveraNo ratings yet

- CasesDocument37 pagesCasesRaymond AlhambraNo ratings yet

- People Vs AdrianoDocument5 pagesPeople Vs AdrianoMagr Esca100% (1)

- People vs. AdrianoDocument4 pagesPeople vs. AdrianoMj BrionesNo ratings yet

- Crim 2 CasesDocument72 pagesCrim 2 CasesRizza MoradaNo ratings yet

- 3people vs. Adriano, G.R. No. L-477, June 30, 1947 (Treason-Membership in An Organization)Document4 pages3people vs. Adriano, G.R. No. L-477, June 30, 1947 (Treason-Membership in An Organization)aldritzNo ratings yet

- 23.cramer v. United States, 65 Sup. Ct. 918Document6 pages23.cramer v. United States, 65 Sup. Ct. 918NEWBIENo ratings yet

- People v. AdrianoDocument6 pagesPeople v. AdrianoJeremy RolaNo ratings yet

- 0007 - People vs. Adriano 78 Phil. 561, June 30, 1947 PDFDocument6 pages0007 - People vs. Adriano 78 Phil. 561, June 30, 1947 PDFGra syaNo ratings yet

- En Banc: THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. APOLINAR ADRIANO, Defendant-AppellantDocument8 pagesEn Banc: THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. APOLINAR ADRIANO, Defendant-AppellantyassercarlomanNo ratings yet

- 5people V AdrianoDocument7 pages5people V AdrianoNana SanNo ratings yet

- Crim2 A - BDocument62 pagesCrim2 A - BAerith AlejandreNo ratings yet

- People Vs AdrianoDocument2 pagesPeople Vs AdrianoMarie TitularNo ratings yet

- BETEZDocument16 pagesBETEZJose BrinNo ratings yet

- 1 - People vs. Adriano, June 30, 1947Document7 pages1 - People vs. Adriano, June 30, 1947moiNo ratings yet

- People v. Adriano GR No L-477Document2 pagesPeople v. Adriano GR No L-477Ma Stephanie GarciaNo ratings yet

- CRIMINAL LAW 2 Study GuideDocument19 pagesCRIMINAL LAW 2 Study GuideMilcah Aquino ValenciaNo ratings yet

- The People of The Philippines vs. Apolinario Adriano, G.R. No. L-477, June 30, 1947Document2 pagesThe People of The Philippines vs. Apolinario Adriano, G.R. No. L-477, June 30, 1947Hazel EstayanNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law II JurisprudenceDocument25 pagesCriminal Law II JurisprudenceDiane MuegoNo ratings yet

- Crim II DigestDocument60 pagesCrim II DigestAnonymous 659sMW8No ratings yet

- 1st Case AssignmentDocument10 pages1st Case AssignmentRikki Marie PajaresNo ratings yet

- Case DigestDocument4 pagesCase DigestLaurene Ashley Sore-YokeNo ratings yet

- Us Vs - Delos ReyesDocument3 pagesUs Vs - Delos ReyesJam PhotostarNo ratings yet

- People vs. AlarconDocument5 pagesPeople vs. AlarconJames OcampoNo ratings yet

- Annex C NatresDocument7 pagesAnnex C NatresIJ SaavedraNo ratings yet

- 1 Title 1 CompleteDocument22 pages1 Title 1 CompletesgonzalesNo ratings yet

- People Vs PrietoDocument2 pagesPeople Vs PrietoRolando ReubalNo ratings yet

- T01C03 People V Prieto 80 Phil 138Document3 pagesT01C03 People V Prieto 80 Phil 138CJ MillenaNo ratings yet

- Plaintiff-Appellee vs. vs. Accused-Appellant The Solicitor General Manuel B. TomacruzDocument29 pagesPlaintiff-Appellee vs. vs. Accused-Appellant The Solicitor General Manuel B. TomacruzAriel MolinaNo ratings yet

- Treason 11 23Document52 pagesTreason 11 23Bhëdz SavarisNo ratings yet

- US Vs Delos ReyesDocument6 pagesUS Vs Delos ReyesDagul JauganNo ratings yet

- Crim II 20161129Document6 pagesCrim II 20161129Bryan MacabayaNo ratings yet

- The United States vs. Antonio Delos ReyesDocument2 pagesThe United States vs. Antonio Delos Reyesdarwin polidoNo ratings yet

- People v. Cawaling, G.R. No. 157147. April 17, 2009 PDFDocument25 pagesPeople v. Cawaling, G.R. No. 157147. April 17, 2009 PDFJohzzyluck R. MaghuyopNo ratings yet

- 004 People v. Manayao (1947) (Dacillo, C.)Document3 pages004 People v. Manayao (1947) (Dacillo, C.)Cyril H. Llamas100% (1)

- People vs. Alicando: Him Is A New Requirement Imposed by The 1985 Rules On Criminal Procedure. It Implements TheDocument7 pagesPeople vs. Alicando: Him Is A New Requirement Imposed by The 1985 Rules On Criminal Procedure. It Implements TheDi ko alamNo ratings yet

- People Vs Prieto DigestDocument2 pagesPeople Vs Prieto DigestLawrence Y. CapuchinoNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law Ii Digests Compilation 2020Document108 pagesCriminal Law Ii Digests Compilation 2020dnzrck100% (4)

- 1902 PDFDocument384 pages1902 PDFGabriel Canlas AblolaNo ratings yet

- Exigent and Emergency CircumstancesDocument4 pagesExigent and Emergency CircumstancesKleyr De Casa AlbeteNo ratings yet

- Title 1Document11 pagesTitle 1Maria Linda TurlaNo ratings yet

- Crim 2 DigestDocument4 pagesCrim 2 DigestpasmoNo ratings yet

- THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. EDUARDO PRIETO (Alias EDDIE VALENCIA), DefendantDocument6 pagesTHE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. EDUARDO PRIETO (Alias EDDIE VALENCIA), DefendantLawrence Y. CapuchinoNo ratings yet

- Final Case Digest For CrimDocument108 pagesFinal Case Digest For CrimBoy Kakak Toki80% (5)

- People V PrietoDocument2 pagesPeople V PrietoJona Phoebe MangalindanNo ratings yet

- Villaflor vs. Summers. 41 Phil. 62, September 08, 1920Document7 pagesVillaflor vs. Summers. 41 Phil. 62, September 08, 1920CassieNo ratings yet

- People vs. Boholst-CaballeroDocument10 pagesPeople vs. Boholst-CaballeroRomy Ian LimNo ratings yet

- Plaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Defendant-Appellant Jose M. Santos First Assistant Solicitor General Reyes Solicitor LacsonDocument6 pagesPlaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Defendant-Appellant Jose M. Santos First Assistant Solicitor General Reyes Solicitor LacsonDuffy DuffyNo ratings yet

- People v. Quiñanola y EscuadroDocument21 pagesPeople v. Quiñanola y EscuadroElmer Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Plaintiff-Appellee Accused-Appellant The Solicitor General Manuel B. TomacruzDocument33 pagesPlaintiff-Appellee Accused-Appellant The Solicitor General Manuel B. TomacruzAndrei Anne PalomarNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law 2 DigestsDocument16 pagesCriminal Law 2 DigestsMces ChavezNo ratings yet

- Treason Cases Digested (Crim Law 2)Document5 pagesTreason Cases Digested (Crim Law 2)Jacob Castro100% (2)

- Cases - National SecurityDocument191 pagesCases - National SecurityLENNY ANN ESTOPINNo ratings yet

- People v. Camerino, 108 Phil. 79Document2 pagesPeople v. Camerino, 108 Phil. 79JNo ratings yet

- People vs. LandichoDocument41 pagesPeople vs. LandichoAira Mae P. LayloNo ratings yet

- 3 US V Lagnason PDFDocument26 pages3 US V Lagnason PDFlianne_rose_1100% (1)

- People'S Journal Et. Al. vs. Francis Thoenen (Freedom of Expression, Libel and National Security)Document4 pagesPeople'S Journal Et. Al. vs. Francis Thoenen (Freedom of Expression, Libel and National Security)Parity Lugangis Nga-awan IIINo ratings yet

- Report of the Decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, and the Opinions of the Judges Thereof, in the Case of Dred Scott versus John F.A. Sandford December Term, 1856.From EverandReport of the Decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, and the Opinions of the Judges Thereof, in the Case of Dred Scott versus John F.A. Sandford December Term, 1856.No ratings yet

- PFR CasesDocument24 pagesPFR CasesJovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- Credits Bar-QDocument34 pagesCredits Bar-QJovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- (G.R. No. 123169. November 4, 1996) DANILO E. PARAS, Petitioner, vs. COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS, Respondent. Resolution Francisco, J.Document57 pages(G.R. No. 123169. November 4, 1996) DANILO E. PARAS, Petitioner, vs. COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS, Respondent. Resolution Francisco, J.Jovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- Sps. Gallent v. VelasquezDocument10 pagesSps. Gallent v. VelasquezJovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- Medical Malpractice: (Torts and Damages)Document20 pagesMedical Malpractice: (Torts and Damages)Jovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- Preference of CreditsDocument9 pagesPreference of CreditsJovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 190810 July 18, 2012 Lorenza C. Ongco, vs. Valeriana Ungco Dalisay, Sereno, JDocument7 pagesG.R. No. 190810 July 18, 2012 Lorenza C. Ongco, vs. Valeriana Ungco Dalisay, Sereno, JJovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- Medical Malpractice: (Torts and Damages)Document8 pagesMedical Malpractice: (Torts and Damages)Jovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- TRANSPODocument27 pagesTRANSPOJovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- Medical Malpractice: (Torts and Damages)Document18 pagesMedical Malpractice: (Torts and Damages)Jovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- December 5, 2017 G.R. No. 217874 OPHELIA HERNAN, Petitioner, The Honorable Sandiganbayan,, Respondent Decision Peralta, J.Document10 pagesDecember 5, 2017 G.R. No. 217874 OPHELIA HERNAN, Petitioner, The Honorable Sandiganbayan,, Respondent Decision Peralta, J.Jovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- Agusan Del Norte v. BalenDocument8 pagesAgusan Del Norte v. BalenJovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- Exconde v. CapunoDocument2 pagesExconde v. CapunoJovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- TORTS 2nd Batch FinalsDocument47 pagesTORTS 2nd Batch FinalsJovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 82248 January 30, 1992 Ernesto Martin, Petitioner, vs. Hon. Court of Appeals and Manila ELECTRIC COMPANY, Respondents. CRUZ, J.Document47 pagesG.R. No. 82248 January 30, 1992 Ernesto Martin, Petitioner, vs. Hon. Court of Appeals and Manila ELECTRIC COMPANY, Respondents. CRUZ, J.Jovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- Pale Canon 20-21Document92 pagesPale Canon 20-21Jovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- Delict Against Petitioner As Employer Arising From The Same Act or Omission of TheDocument5 pagesDelict Against Petitioner As Employer Arising From The Same Act or Omission of TheJovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- Other Code of Commerce Provisions On CaptainsDocument57 pagesOther Code of Commerce Provisions On CaptainsJovy Balangue MacadaegNo ratings yet

- Training Proposal-ALIVEDocument6 pagesTraining Proposal-ALIVEdarwinNo ratings yet

- Franz Resume UpdatedDocument2 pagesFranz Resume UpdatedKelly ChengNo ratings yet

- History of BongabonDocument5 pagesHistory of BongabonRosel Sarabia50% (2)

- Final Masquerade JS PROM Tricia DuenasDocument32 pagesFinal Masquerade JS PROM Tricia DuenasKrystine TuazonNo ratings yet

- Workweek Plan Grade 6 Third Quarter Week 2Document15 pagesWorkweek Plan Grade 6 Third Quarter Week 2Lenna Paguio100% (1)

- Travel Order LandbankDocument12 pagesTravel Order LandbankJonel TorresNo ratings yet

- CERTIFICATES by Savanna CunninghamDocument15 pagesCERTIFICATES by Savanna CunninghamPeachy MarianoNo ratings yet

- Hope 2-G11Document11 pagesHope 2-G11Aprille RamosNo ratings yet

- NPS Directory - 2023Document10 pagesNPS Directory - 2023Noemi MejiaNo ratings yet

- Contract of ServiceDocument11 pagesContract of ServiceHazel Dela PeñaNo ratings yet

- Backyard Camping Schedule of ActivitiesDocument9 pagesBackyard Camping Schedule of ActivitiesHazel Dela PeñaNo ratings yet

- Resume G12Document2 pagesResume G12Austin BlackNo ratings yet

- Gabriel2018 ReferenceWorkEntry BureaucraticRedTapeInThePhilipDocument10 pagesGabriel2018 ReferenceWorkEntry BureaucraticRedTapeInThePhilipAnaliza V. MuñozNo ratings yet

- Region 3 Data BaseDocument47 pagesRegion 3 Data BaseCess SexyNo ratings yet

- Final Seminar Maria Carmela R. ArcillaDocument34 pagesFinal Seminar Maria Carmela R. ArcillaKrystine TuazonNo ratings yet

- RDO No. 23A - Talavera, North Nueva EcijaDocument975 pagesRDO No. 23A - Talavera, North Nueva EcijagabbyNo ratings yet

- Participating Site List 108 FNLDocument13 pagesParticipating Site List 108 FNLRussel ZarateNo ratings yet

- Inquiry FormDocument6 pagesInquiry FormJefferson LiwagNo ratings yet

- Action Plan - Work ImmersionDocument10 pagesAction Plan - Work ImmersionAirah De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- PDF History of Gapan City Nueva Ecija - CompressDocument2 pagesPDF History of Gapan City Nueva Ecija - CompressJohnross Anatalio0% (1)

- Do18 2013BDocument7 pagesDo18 2013BarnoldNo ratings yet

- aCTION PLAN IN HEALTHDocument13 pagesaCTION PLAN IN HEALTHCATHERINE FAJARDONo ratings yet

- Art Exhibit (Choi)Document20 pagesArt Exhibit (Choi)ROGEL SONo ratings yet

- Crim2 A - BDocument62 pagesCrim2 A - BAerith AlejandreNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: School Tracking MechanismDocument2 pagesDepartment of Education: School Tracking MechanismDarwin GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Week-2 Quarter 3Document4 pagesWeek-2 Quarter 3Marybeth GutierrezNo ratings yet

- History of Nueva EcijaDocument50 pagesHistory of Nueva EcijaJulius Maderia100% (1)

- RLFI BPI Endorsement SY 2023 2024 For Scholars With NamesDocument8 pagesRLFI BPI Endorsement SY 2023 2024 For Scholars With NamesYOW BiatchNo ratings yet

- Nueva Ecija-Area Based Management Plan For Pampanga River Basin 2014Document17 pagesNueva Ecija-Area Based Management Plan For Pampanga River Basin 2014Margarita AngelesNo ratings yet