Professional Documents

Culture Documents

10.1017 s0140525x00012759 PDF

Uploaded by

kristian FelipeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

10.1017 s0140525x00012759 PDF

Uploaded by

kristian FelipeCopyright:

Available Formats

THE BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (1982) 5, 407-467

Printed in the United States of America

Toward a general psychobiological

theory of emotions

Jaak Panksepp

Department of Psychology, Bowling Green

State University, Bowling Green, Ohio 43403

Abstract: Emotions seem to arise ultimately from hard-wired neural circuits in the visceral-limbic brain that facilitate diverse and

adaptive behavioral and physiological responses to major classes of environmental challenges. Presumably these circuits developed

early in mammalian brain evolution, and the underlying control mechanisms remain similar in humans and "lower" mammals. This

would suggest that theoretically guided studies of the animal brain can reveal how primitive emotions are organized in the human

brain. Conversely, granted this cross-species heritage, it is arguable that human introspective access to emotional states may provide

direct information concerning operations of emotive circuits and thus be a primary source of hypotheses for animal brain research. In

this article the possibility that emotions are elaborated by transhypothalamic executive (command) circuits that concurrently activate

related behavior patterns is assessed. Current neurobehavioral evidence indicates that there are at least four executive circuits of this

type - those which elaborate central states of expectancy, rage, fear, and panic. The manner in which learning and psychiatric

disorders may arise from activities of such circuits is also discussed.

Keywords: affect; brain theory; command circuits; emotion; expectancy; fear; hypothalamus; panic; psychiatric disorders; rage;

reinforcement

The scientific study of emotions is beset by more than the more knowledge concerning the nature of emotions may

usual number of methodological and conceptual prob- be derived than from either approach taken alone. This is

lems. It is difficult to agree how, within the constraints of not to say that we can measure the subjective awareness

scientific objectivity, we can derive substantive under- of other animals, but to assert that basic emotions may

Standing of phenomena that appear intimately linked to have obligatory internal dynamics, which humans share

the internal experiences of organisms. In animal re- with other mammals. By using our subjective sources of

search, the traditional solution (and compromise) has insight concerning these dynamics, we may be able to

been to study the objective behavioral and physiological resolve some of the subtleties of brain organization more

manifestations of presumed emotional states, with an readily than if we follow the dictum that all we can know

exclusive focus on behavior and a calculated disregard of are the behavioral and physiological symptoms of emotive

the underlying states. Conversely, at the human level states.

there is abundant discussion of the various emotional In any event, it should be self-evident that the use of

states and little knowledge concerning their sources in anthropomorphism in the study of mammalian emotions

the brain. Thus, while major concepts concerning the cannot be arbitrarily ruled out. Although its application

nature of emotions arise from human introspection, most may be risky under the best of circumstances, its validity

knowledge concerning the mechanisms underlying emo- depends on the degree of evolutionary continuity among

tionality arises from animal brain research. This paper is brain mechanisms that elaborate emotions in humans and

based on the conviction that the study of emotions, in animals. Hence, the degree of anthropomorphism that

both humans and animals, continues to be impoverished can have scientific utility in mammalian brain research

by our failure to blend these two sources of knowledge. should be directly related to the extent that emotions

The major obstacles to achieving the above synthesis reflect class-typical mechanisms as opposed to species-

are our inability to read the animal mind as directly as we typical ones.

can read our own and the subtleties of emotional nuance Although a definitive statement concerning the degree

that can evolve during the course of social learning in of similarity between neural systems that mediate emo-

humans. Accordingly, introspection and the consequent tions in animals and humans cannot be made, available

tendency to anthropomorphize remain anathema in ani- evidence suggests that fundamental emotional circuits

mal research. However, the fundamental organization of are inherited components of the limbic brain, which are

emotions in the brain may be quite similar in humans and to a substantial degree a shared mammalian heritage

other mammals. If this is so, recent advances in brain (Crosby & Showers 1969; MacLean 1973; Parent 1979).

research may permit anthropomorphism to become a Species-typical instinctual behaviors remain intact even

more useful strategy for understanding certain primitive after radical decortication soon after birth (e.g., Murphy,

psychological processes in animals than it has been in the MacLean, & Hamilton 1981), and, with few exceptions,

past. Through the conjoint application of an- trauma to subcortical tissue in humans yields behavioral

thropomorphic reasoning and animal brain research, changes similar to those which result from experimental

© 1982 Cambridge University Press 0140-525X1821030407-61 IS06.00 407

Panksepp: Psychobiology of emotions

manipulation of these circuits in other mammals. For individual emotive circuits. (4) The most efficient and

instance, animals with ventromedial hypothalamic le- reasonable way to obtain an initial neurotaxonomy of the

sions exhibit voraciousness and rage (Heatherington & hard-wired emotional processes in the mammalian brain

Ranson 1942; Wheatley 1944), as do humans (Reeves & is through introspection. (5) The scientific understanding

Plum 1969). Posterior hypothalamic damage brings on of emotional processes must arise from a clarification of

somnolence, and anterior hypothalamic damage insom- how they are organized in the brain (and hence, out of

nia, in both animals and humans (McGinty & Sterman "ethical" necessity, the animal brain).

1968; Nauta 1946; Ranson 1939; von Economo 1930). On the basis of these assumptions, the substantive aims

Electrical stimulation of the amygdala can yield rage in of this paper are to propose a taxonomy of emotions that is

both (de Molina & Hunsperger 1963; King 1961). Al- supported by existing neurobehavioral data; to provide an

though exceptions to such apparent homologies could approximate neural scheme of how emotions may be

also be cited, the general conclusion appears to be that organized in the brain; and to discuss the implications of

the functional terrain of the subcortical limbic brain such circuits for the understanding of learning and emo-

across mammalian species is remarkably similar, in kind if tional disorders. Admittedly, each successive aim is

not in precise organization. Accordingly, the study of based on increasingly large measures of speculation. In

these parts of the emotional brain in animals should general, I shall argue that "the mammalian brain" con-

provide a credible outline for understanding the primi- tains at least four primitive executive (command) circuits

tive emotional functions of the human brain. Conversely, that initiate the distinct subjective emotional states of

it should follow that some properties of these circuits in expectancy, fear, rage, and panic in humans and that

the animal brain could be deciphered by judicious intro- trigger the corresponding emotive processes in animals.

spection. Although it is not evident how a clear path First, however, I shall trace some of the historical roots of

through the possibilities of human imagination is to be this endeavor.

achieved, anthropomorphic excesses can be checked by

the constraint that verifiable consequences must be gen-

erated with the accepted empirical tools of behavioral Historical overview

brain research. By insisting that introspectively derived

conceptions of animal emotion be linked simultaneously A great deal has been written on emotions through the

to specific behaviors and brain processes, the testability ages, and one who attempts the journey through that

of the resulting ideas could help stave off the terminally material may soon concur with James (1892, p. 241) that

debilitating scholastic debates, which have immobilized "the varieties of emotion are innumerable" and that the

this important area of inquiry in the past. descriptive literature on the subject "is one of the most

Although behavioral and physiological effects of emo- tedious parts of psychology. And not only is it tedious, but

tional states may be all that can ever be empirically you feel that its subdivisions are to a great extent either

measured in animals, some of these could be used as fictitious or unimportant, and that its pretences to ac-

indicator variables for more hidden central processes that curacy are a sham," so that "reading of classic works on

may be operative in certain situations. Indeed, such an the subject" is as interesting as "verbal descriptions of the

indirect theoretical analysis of certain neural systems may shapes of the rocks on a New Hampshire farm."

be essential, because the field of inquiry is confronted by Still, at the conceptual Jevel, an inquiry into emotions

experimental difficulties similar to those encountered in must start with a taxonomy of emotional experience in

particle physics, where the clarification of intranuclear humans. Were it not for the consensus that such subjec-

forces has to proceed through indirect observations that tive states exist in humans, emotion as a construct would

yield only indirect affirmative or negative evidence about never have arisen in the study of animal behavior. Many

the nature of the underlying processes. In a similar way, plausible taxonomies of emotions have come from the

the functions of certain brain circuits may be sufficiently consideration of such subjective states, and it is reason-

internalized in the fabric of the brain so that their normal able to expect that a cogent physiological theory of emo-

operations and intersystemic cleavage lines need to be tion should subsume the best organizational principles

derived initially by introspectively based theoretical in- generated from that perspective. Historically, the con-

ference. Of course, our initial conceptualizations will struction of taxonomies of emotional experience, though

invariably be simplifications, which fail to do full justice to not strictly empirical, led directly to the study of emo-

the actual circuit configurations in the brain. With such tional expression in humans and kindred animals and,

qualifications in mind, the overall aim of this paper is to recently, to attempts to specify how various emotional

outline a testable theory of how emotional processes may processes are related to physiological changes in both

be organized in the central nervous system of mammals. brain and body.

Because they will receive little further emphasis here,

I shall reiterate the theoretical assumptions underlying Taxonomies of emotion. In one of the earliest major

this proposal. They are: (1) Distinct emotional processes treatises to attempt to relate brain and mind, Willis (1683,

reflect activity in specific hard-wired brain circuits. (2) p. 49) began his ninth chapter on "Two Discourses

Humans share essentially similar primitive emotional Concerning the Soul of Brutes" as follows:

processes with all other mammals and perhaps some Concerning the Number of the Passions, as it hath

related vertebrates. (3) The number of fundamental emo- been variously disputed among Philosophers, so in

tional circuits is limited, but through their intermixtures famous Schools, this Division into Eleven Passions,

and social learning, emotions in humans have a much long since grew of use; to wit, the Sensitive Appetite is

richer phenomenological texture than is contained in the distinguished into Concupiscible and Irascible, to the

408 BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (1982)3

Panksepp: Psychobiology of emotions

first, are counted commonly six Passions, viz. Pleasure Table 1. Taxonomy of the passions (Cogan, 1802)

and Grief, Desire and Aversions, Love and Hatred; but

to the latter five, viz. Anger, Boldness, Fear, Hope, Class I Passions arising from principle of self-love

and Desperation, are wont to be attributed. Order I From the idea of good

Foreshadowing future controversies, Willis disagreed: Genus 1 Good in possession (JOY: gladness, cheerful-

But this distribution of the Affections is not only in- ness, mirth, satisfaction, contentment, com-

congruous, for that Hope is but ill referred to the placency)

Irascible Appetite, and Hatred and Aversion, seem Genus 2 Good in expectancy—DESIRE

rather to belong to this, than to the Concupiscible: But Order II From the idea of evil

it is also very insufficient, because some more noted Genus 1 Losses and disappointment—SORROW

Affections, as Shame, Pity, Emulation, Envy, and Genus 2 Evils which are apprehensive—FEAR

many others, are wholly omitted: Wherefore the An- Genus 3 Conduct which deserves reprehension—

cient Philosophers did determinate the Primary to a ANGER

certain Number, then they placed under their several

Kinds, very many indefinite Species. Class II Passions and affections derived from the so-

Perhaps as a reaction to the categorical excesses of cial principle

medieval scholastics, Descartes, in his discourse on "the Order I Excited by ideas of benevolence

passions of the soul" (1650), reduced emotional life to six Genus I Benevolent desires (generosity, condolence,

primary passions: wonder, love, hate, desire, joy, and pity, charity, liberality)

sadness, with all the rest being "made up of some of these Genus 2 Good opinion (gratitude, thankfulness, admi-

six or at least are species of them" (cf. Ruckmick 1936, p. ration)

39). The idea that primary emotional processes are lim- Order II Excited by idea of evil

ited to a relatively small group of fundamental systems is Genus 1 Malevolence (malice, envy, rancor, cruelty,

still with us, with the number of primary emotions usually prejudice, jealousy, resentment, revenge)

ranging from three to eight; the father of behaviorism Genus 2 Unfavorable opinion (horror, contempt, dis-

suggested that three, namely, fear, rage, and sexual love, dain)

characterized the fundamental nature of man (Watson

1924). However, except for general suggestions of where

emotions may be elaborated in the brain (e.g., Papez

1937), as well as highly concrete neurophysiological hy- overcome, straightforward, testable hypotheses can be

potheses concerning the genesis of specific emotions

generated, and refutations can be decisive.

(e.g., anxiety, in Gray, 1979), there has been little at-

tempt to relate any of the well articulated taxonomies of The expression of emotion. Perhaps as a response to the

emotion to specific brain circuits. The aim of this paper is endlessly equivocal nature of introspectively derived

to attempt such a synthesis. [See also BBS multiple book taxonomies of emotions, as well as the development of

review of Gray: The Neuropsychology of Anxiety, BBS 5 new intellectual disciplines, such as physiognomy (Lava-

(3) 1982, this issue.] ter 1789-98) and phrenology (Gall 1835; Spurzheim

After the ideas expressed in this paper had crystallized, 1832), the nineteenth century saw the rise of descriptive

I discovered a forgotten system closely resembling it in analysis of emotional expression, ranging from detailed

form, if not specific content. This system, proposed by studies of the facial musculature generating the emotional

Cogan (1802) and summarized in Table 1, viewed emo- countenance (Bell 1806) to the recognition that the ste-

tions from the subjective perspective, and thus contained reotyped character of emotional expression in animals

the existential virtues (or mentalistic excesses, depending and humans indicates the common inheritance of mecha-

on one's point of view) that have traditionally proved nisms that govern the elaboration of emotions (Darwin

troublesome in the scientific analysis of emotion. Howev- 1872). At the end of the century, the emphasis on emo-

er, it will be argued that the scheme contains the seed of tional expression, as opposed to emotional experiences or

truth that any credible psychobiological theory of emo- processes, led to the renowned James-Lange theory

tion must ultimately nurture. Cogan suggested that hu- (James 1884), which entertained placing anger inside the

mans inherit five primitive passions - those of desire, fist rather than behind it. By proposing that the bodily

anger, fear, sorrow, and joy. Under somewhat different changes occurring during emotive acts might be causes

labels, expectancy, rage, fear, and panic, I shall attempt rather than consequences of emotions, the James-Lange

to relate the first four of these passions to the circuitry of theory challenged common reason and reaped a harvest

the visceral brain. of negative evidence and critical counterargument (Can-

Since Cogan's time, many other taxonomies have been non 1927, 1931; Sherrington 1900), though perhaps none

proposed, but in the absence of concurrent analyses of sufficiently compelling as to be decisive, especially if one

brain mechanisms, they remain on the fringes of science. wished to entertain an infinite regress into the potential

Recent thought on the subject has been well summarized subjective awareness of a brain disconnected of its inputs

by Ruckmick (1936) and Plutchik (1980). Without phys- and outputs. Although it is likely that peripheral auto-

iological anchor points, theories of emotion remain gra- nomic feedback influences the labeling of emotional

tuitous because they cannot escape from fatal cir- states in humans and provides reafferent feedback that

cularities, although they can generate useful experimen- intensifies emotional experience (Schachter & Singer

tation (Strongman 1973). With clearly specified 1962) and behavior (Baccelli, Guazzi, Libretti, & Zan-

physiological anchor points, however, circularity can be chetti 1965), it now seems likely that the James-Lange

BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (1982)3 409

Panksepp: Psychobiology of emotions

theory reversed primary cause and consequence. Yet, only medial and temporal cortex were left intact, amend-

unlike earlier inquiries such as Darwin's, in which little ing the earlier idea that the cortex generally inhibited

heed was given to the nature of proximal causes, the emotional responsivity (Bard & Mountcastle 1948). Since

James-Lange perspective emphasized the need for such heightened emotionality emerged gradually following

a level of analysis if emotions were ever to be probed damage to those remaining cortical areas, it was sug-

experimentally. gested that inhibition of emotional responsivity might be

The study of emotional expression, as reflected in due specifically to limbic cortical influences, but this

somatic and visceral changes, has remained a hallmark of conclusion remained tenuous, because it was outwardly

the scientific analysis of emotions (Ax 1953; Eibl- inconsistent with the emotional placidity that appeared

Eibesfeldt 1979; Ekman 1973; Grings & Dawson 1978). after temporal lobe damage in monkeys (Kluver & Bucy

Unfortunately, brain research generally continues to 1937) and cats (Schreiner & Kling 1953). More recently,

cling to the tenet that the only credible scientific ap- wildness has been induced by cingulate cortical damage

proach to this area is the study of emotional expression. in neodecorticate animals (Murphy et al. 1981), suggest-

Although the approach has yielded many elegant facts ing that disinhibition of rage may have resulted from

(Flynn 1976; Hess 1957), it is my contention that such a damage to medial limbic cortex.

single-minded focus on emotional expression without Although many questions concerning decorticate rage

concurrent consideration of underlying emotional pro- remain, it is now clear that both excitatory and inhibitory

cess has outlived its usefulness in psychobiology and may influences on emotional behavior are elaborated through

be currently hindering progress in understanding the limbic cortex and ganglia (Ursin 1965; Ursin & Kaada

neural organization of emotion. 1960). The early studies definitively localized the elabora-

tion of primitive emotional tendencies in the vis-

Brain organization of emotive processes. Since range ceral-limbic brain, and the old controversies concerning

could be precipitated in animals by decerebration (Goltz whether the emotional changes observed in some of those

1892), the suspicion arose that certain subcortical parts of early studies were devoid of emotional content, whether

the brain were important for organizing emotions. How- they were "sham" or "real," have become less pertinent

ever, it was not until after the turn of the century that with the recognition that hierarchical levels of organiza-

experimental evidence was found that indicated that tion exist within functionally continuous psycho-

certain areas of the brain, especially those near the behavioral organ systems of the brain (Bernston & Micco

ventral surface, are critical for organizing the autonomic 1976). Indeed, questions of animal awareness were

changes that accompany emotional states and behaviors. shelved as basically unanswerable, and the mainstream of

Further study of decorticate rage by Bard (1928; 1934), investigation continued to focus on the actual brain cir-

Cannon (1929), and others established that the expression cuits that participate in the expression of "emotive"

of anger could be initiated subcortically, suggesting that behaviors. It became clear that the functions of higher

the neocortex tonically inhibits circuits that mediate this brain areas >vere mediated through lower systems (de

emotional behavior. This discovery led to the hypothesis Molina & Hunsperger 1962), and it came to be widely

that endogenous brain systems elaborate emotions and, assumed by psychobiological investigators that the elu-

specifically, that thalamic circuits mediate emotional ex- cidation of hard-wired brainstem circuits would provide

periences (Cannon 1929). Concurrently, Karplus and the basic information through which higher functions

Kreidl (1909; 1927), followed by Kabat (1936), Ranson and were ultimately to be understood. At the same time, the

Magoun (1939), and others, were demonstrating dramatic likely relevance of these circuits to the emotional life of

changes in the autonomic responsivity of anesthetized humans was implicitly accepted but generally treated

cats during localized electrical stimulation of the hypo- with benign neglect. The translation between the two was

thalamus. This response suggested that the ventral part of understood to be empirically impossible, and hence, in

the upper brainstem was a head ganglion of the autonom- some ultimate logical sense, gratuitous.

ic nervous system, which participated in the genesis of Thus, even though there has been a great deal of

emotional behavior and experience. The fact that excellent work on brainstem mediation of emotive behav-

thalamic damage did not eliminate decorticate rage in iors, especially aggression, there has been little attempt

cats (Bard & Macht 1958) affirmed the probability that the to integrate concepts from the taxonomy of human emo-

hypothalamus was essential for elaborating emotional tional experience with data concerning the limbic circuit-

responsivity. Hess's studies (1925-49, and English sum- ry of the animal brain. Although the work on brain

mary in 1957) established that rage and other well coordi- organization of aggression has yielded a harvest of knowl-

nated emotive behaviors could be instigated by localized edge (Adams 1979; Flynn 1976; Siegel & Edinger 1981),

electrical stimulation of the hypothalamus in a conscious as has the analysis of autonomic changes that typically

animal. This work solidly established the concept that the accompany such agonistic emotive states (Mancia &

emotional nervous system is embedded in the visceral Zanchetti 1981), other affective processes that do not

nervous system. Later, with the recognition of the di- have such dramatic somatic and autonomic manifesta-

verse anterior connectivities of hypothalamic systems tions remain largely unstudied.

(Papez 1937) and the emotional changes resulting from

damage to those circuits (Bard & Mountcastle 1948;

Kluver & Bucy 1939), the concept of a visceral-emotional

brain was generalized to the entire limbic system (Mac- A definition of emotions

Lean 1949).

On the assumption that emotions arise from the activities

Further study of restricted decortications in cats indi- of brain circuits, a general definition of emotion would

cated an insensitivity to emotion-provoking stimuli when consist of a list of attributes such brain circuits possess. In

410 BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (1982)3

Panksepp: Psychobiology of emotions

the absence of extensive knowledge concerning these a distinction between affective "feelings" and "emotions"

circuits, the list must first be constructed rationally. I may be made on the basis of the degree of arousal within

propose that such circuits have at least the following six an emotive system. Thus, environmental stimuli that

attributes: (1) They are genetically hard-wired and de- provoke weak interactions with primitive emotive cir-

signed to respond unconditionally to stimuli arising from cuits without generating sustained reverberatory feed-

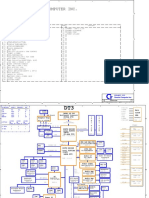

major life-challenging circumstances (Figure 1). (2) They back may be considered to have simply provoked an

organize behavior by activating or inhibiting classes of affective "feeling." Furthermore, the fact that there are a

related actions (and concurrent autonomic/hormonal variety of homeostatic interoreceptors in the hypo-

changes) that have proved adaptive in the face of those thalamus, designed to monitor various bodily states,

types of life-challenging circumstances during the evolu- which not only interact with emotive systems but which

tionary history of the species (Figure 2). (3) Through surely also have distinct sensory attributes, further ampli-

recurrent feedback, emotive circuits change the sen- fies the variety of discriminable "feelings" that can be

sitivities and responsivities of sensory systems relevant elaborated by the brain. By assuming that most of the

for those behavior sequences. (4) The activity in the internal and external stimuli encountered in everyday life

underlying neural systems can outlast the precipitating interact with a limited number of primitive emotive

circumstances (i.e., there is either substantial positive circuits, the list of distinct emotions can be kept much

feedback or long-term neuromodulation in the circuits). shorter than the list of distinct feelings. Accordingly,

(5) Activity in these circuits can come under the condi- questions of how the affective coloring of each human

tional control of emotionally neutral environmental stim- subjective experience is achieved can be shelved until the

uli via a reinforcement process that is a design feature of primitive emotional circuitries of the brain are deline-

each emotive circuit. (6) Activity in such circuits has ated, and the analysis of basic emotive systems need not

access to and reciprocal interactions with brain mecha- be paralyzed by the vast variety of human affective

nisms that elaborate consciousness (to provide higher- experience in the real world.

order response selection among the specific behavioral Moreover, several primitive affective states, which

acts that are sensitized by arousal of an emotive system). have been incorporated in past taxonomies of emotional

It is only this last aspect of emotions, so evident in human life, will be ignored because they do not appear to fulfill

mental life, which remains so untestable in animal re- all of the criteria mentioned above. For instance, neither

search. However, since all mammals seem to share funda- "surprise" and "disgust," both of which have clear behav-

mentally similar emotive brain circuits, this last attribute ioral referents in animals (e.g., Davis 1979; Grill &

may prove to be the "Rosetta stone" via which the general Norgren 1978) and may be controlled by specific brain-

organization of the primitive hard-wired emotional sys- stem circuits (the "stimulus-bound" startle and retching

tems of the mammalian brain can be deciphered. described by Hess, 1957), are included as major emo-

Thefirstfour criteria should help delimit the number of tional states in the present context (powerful affects as

emotive circuits in the mammalian brain and help gener- they may be in humans), because they do not activate

ate distinctions among the many vague terms that have diverse classes of species-typical behaviors (permitting

been used in discussions of the affective life. For instance, adaptive response selection among alternatives) and be-

cause their underlying states appear to be largely time-

locked to the precipitating stimuli, with no sustained

regenerative feedback in the underlying brain systems.

In other words, "startle" and "disgust" may be more

reflexive in character than the brain processes that are

herein considered to be truly emotional.

For similar reasons, the concepts of pleasure/relief and

displeasure/distress are not included in the present analy-

sis. Such states do not appear to generate unique behav-

ioral manifestations, and such generalized affects may cut

across many distinct emotive states and probably arise

secondarily from changes in activity of the discrete emo-

PAIN .ndTHREAT tive systems to be discussed. For instance, pleasure and

Of M>RM

DESTRUCTION relief may be states which accompany stimuli that tend to

return organisms toward physiological homeostasis and

emotional equilibrium, while unpleasantness and dis-

tress may arise from stimuli that remove an organism

from those respective conditions (Aristotle in "Nic-

homachean Ethics"; Cabanac 1971). Although such con-

cepts can yield general behavioral predictions in animal

research (as generalized response guiding principles) and

may even operate through discrete neurochemical sys-

tems of the brain, such as dopamine (Wise 1982) or

endorphins (Panksepp 1981b; Stein & Belluzzi 1978),

they will not be discussed further here because currently

Figure 1. Major classes of environmental stimuli that require their behavioral indicators in animals are rather subtle

rapid behavioral adjustments presumably converge upon com- and diffuse; incisive approaches to the neurobiological

mand systems of the brain to trigger species-typical sensory- analysis of these more generalized phenomena may first

motor patterns.

BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (1982)3 411

Panksepp: Psychobiology of emotions

FOREWARD LOCOMOTION, SNIFFING, INVESTIGATION

STIMULUS-BOUND-

APPETITIVE

BEHAVIOR

AND

SELF-STIMULATION

a.

U

o STIMULUS-BOUND

FLIGHT

"STIMULUS-BOUND

DISTRESS VOCALIZATION

AND AND

ESCAPE BEHAVIORS EXPLOSIVE BEHAVIORS

i

N

Ui

Ul

STIMULUS-BOUND-

BITING

AND

AFFECTIVE ATTACK

ATTACK, B I T I N G , FIGHTING

Figure 2. Emotive-command systems are defined primarily by neural circuits from which well-organized behavioral sequences can

be elicited by localized stimulation of brain tissue. The approximate locations of these systems are depicted on hemifrontal

hypothalamic sections of the rat brain; cp - cerebral peduncle; dm - dorsomedial nucleus; mf - medial forebrain bundle; mt

-mammillothalamic tract; ot - optic tract; re - nucleus reuniens; vm - ventromedial nucleus; x - fornix; zi - zona incerta. The major

behavioral outputs of each command system are indicated. The various command systems are anatomically close to each other and

presumably interact so as to maintain behavioral focus on a single class of behaviors. It is assumed that the various possible

interactions among systems lead to second-order emotive states consisting of blended activities across the primary systems. Some

possible interactions are outlined. Some systems may also have biphasic interactions depending on the level of activity within an

emotive system and the past experiences of the animal.

require clarifying the mechanisms that organize the more Emotive circuits of the brain: The theory

discrete emotive states of the brain.

Within these constraints, the analysis of the brain Emotional concepts can be tied to specific brain mecha-

mechanisms mediating emotions becomes a more man- nisms through a variety of maneuvers. The idea that

ageable undertaking. Only certain neural circuits begin emotions simply arouse (Duffy 1941) served as a theoreti-

to fulfill the definitional requirements of emotive sys- cal basis for proposing that the ascending reticular activat-

tems, and many of the fuzzier dimensions of affective life ing system is a physiological substrate for emotion

can be temporarily excluded from consideration. (Lindsley 1950). The fact that localized stimulation of the

412 BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (1982)3

Panksepp: Psychobiology of emotions

limbic system could induce both positive and negative discrete behaviors that can be observed during such

affective states, as indicated by species-typical approach stimulation appears to be greater than the number of

and escape behaviors, suggested that emotions and rein- discrete command systems actually present under the

forcements are intrinsically organized by dichotomous stimulating electrodes. Of course, this is reasonable if one

affective circuits of the brain (Glickman & Schiff 1967). considers that the function of such executive systems may

Although the most illuminating results, with regard to be to facilitate simultaneously a number of related behav-

how emotions are organized in the nervous system, have ioral options so that reinforcement processes can mold

been obtained using localized electrical stimulation of adaptive behavior sequences for a variety of related life

brain tissue with indwelling electrodes in awake animals circumstances (Figure 1), which differ in detail.

(Hess 1957), I believe the evidence supports the exis- In any event, this discrepancy poses great problems for

tence of a more highly articulated emotive "phrenology" accurate categorization, as is apparent in recent contro-

in the limbic system than has been postulated before. versies over the nature of the circuits which mediate

It is astounding that the simple application of electrical "stimulus-bound" appetitive behaviors in the hypo-

"noise" to certain brain areas can yield a variety of well- thalamus. For instance, from a relatively diffuse zone

coordinated species-typical behavior sequences, most centered around the dorsolateral hypothalamus of the rat,

notably ones which appear to reflect emotional states. By we can evoke feeding, drinking, gnawing, hoarding, pup

stimulating specific areas in the hypothalamus, we can retrieving, predatory aggression, and copulation. Are

induce animals to exhibit ragelike behaviors, explorato- there discrete circuits under our electrodes for each of

ry-investigative behaviors, flight, and several other be- these behavioral acts (the specificity hypothesis), or are

havior patterns indicative of complex neuropsychological they all induced by a unitary neural influence (the non-

integration. The waveform of the electricity applied to specificity hypothesis)? Without going into details, which

the brain tissue does not seem to be orchestrating the can be found elsewhere (Panksepp 1981a), current evi-

actual sequences of the artificially elicited behavior. The dence overwhelmingly supports the nonspecificity hy-

simplest explanation for these remarkable effects is that pothesis for such stimulus-bound appetitive behaviors.

we are stimulating neural networks that can facilitate Aside from the basic demonstration of behavioral mal-

(command) activity in distant sensory filtering systems leability after lateral hypothalamic stimulation (i.e., one

and motor patterning circuits governing the sequencing appetitive behavior can be changed to another through

of emotive acts. experience: Valenstein et al. 1970), the most important

The activation of these systems not only induces emo- evidence supporting such a conclusion is: (1) "Stim-

tional behaviors and concurrent visceral and hormonal ulus-bound" appetitive behaviors do not change when an

changes (Mancia & Zanchetti 1981), but it also sensitizes electrode is passed through the relevant lateral hypothal-

sensoryfieldson the body surfaces. In cats, hypothalamic amic field of a single animal (Wise 1971). (2) The type of

stimulation yielding attack, increases perioral biting re- behavior elicited from an electrode does not change when

flexes, the probability that touch to the arm will induce the tissue under the electrode is damaged; instead, the

lashing out, and aggressive responsivity of the con- threshold for elicitation of the behavior is increased

tralateral eye (Flynn 1976). In rats, hypothalamic stimula- (Bachus & Valenstein 1979). (3) The temperament of the

tion that induces stimulus-bound appetitive behaviors test animal may be more important in determining the

can increase perioral (Smith 1972) and visual (Beagley & stimulus-bound appetitive behavior observed than the

Holley 1977) sensitivity, and damage to these systems is exact location of the stimulating electrode in the active

accompanied by sensory-motor neglect (Balagura, zone within the dorsolateral hypothalamus (e.g., stim-

Wilcox, & Coscina 1969; Frigyesi, Ige, Iulo, & Schwartz ulus-bound predatory attack in rats is most easily ob-

1971; Marshall & Teitelbaum 1974). Also, even though tained in animals that exhibit some tendency to spon-

the most spectacular kinds of stimulus-bound behavior taneously emit this behavior: Panksepp 1971a).

are strictly limited to the duration of brain stimulation, Still, this is not to suggest that several distinct emotive

more subtle behavioral changes persist for a while. For circuits do not course through the lateral hypothalamic

instance, Hess (1957) and Nakao (1958) detected affective field where stimulus-bound behaviors are most fre-

changes in their cats for minutes following hypothalamic quently encountered, for there appear to be several

stimulation. Similarly, the increased motor activity in- distinct classes of behavior that can be activated (Figure

duced by stimulation of lateral hypothalamic reward sites 2). Also, the present conception of nonspecificity does not

decays gradually during the minute following stimulation imply that the functions of the underlying circuits are not

(Rolls & Kelly 1972). The general functions of these genetically determined. Although each emotive circuit

circuits appear to be genetically coded (Roberts & Ber- may be nonspecific in the sense that it can provoke

quist 1968), although the exact behavioral expressions of several distinct emotive actions, they may all be specific

each system may be quite malleable (Valenstein, Cox, & (hard-wired), in the sense that each generates a single,

Kakolewski 1970). homogeneous psychobehavioral tendency (Figures 1 and

This paper is based on the assumption that these 2). Presumably, an analysis of these partially interdigitat-

ing, transhypothalamic emotive command circuits pres-

"stimulus-bound" behaviors reflect species-typical ex-

ently provides the best foundation for neurophysiological

pressions of class-typical brain circuits which mediate understanding of emotions in both animals and humans.

emotions, and, hence, that a realistic and scientifically To some investigators in the field this may be self-

useful taxonomy of emotions, in humans as well as other evident, but the scarcity of neuro-psycho-behavioral

mammals, could be based upon the number of distinct investigations based on this assumption suggests that it

behavioral control systems that can be activated in this has not yet been widely accepted.

manner. However, difficulties arise in enumerating the

number of emotive command systems, for the number of Herein I propose four fundamental transdiencephalic

BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (1982)3 413

Panksepp: Psychobiology of emotions

emotion-mediating circuits passing between midbrain, major label for this system, because it is assumed that the

limbic system, and basal ganglia of the mammalian brain. circuit readily comes under the conditional control of

Based on the extreme emotional experiences that these environmental cues and is thereby essential for elaborat-

systems are presumed to mediate in humans, they are ing anticipatory appetitive behaviors. Accordingly,

labeled the "expectancy," "rage," "fear," and "panic" throughout this paper expectancy is intended only in the

circuits. Their specific neuronal projections and interac- positive sense, as hope, desire - joyful anticipation,

tions can only be surmised, but from localized rather than in the negative sense in which it can also be

brain-stimulation studies we do know the approximate used.

locations of these circuits in the several species. Although

sites have been identified in diverse areas of the brain, at Fear. It is proposed that sites in the hypothalamus from

present the hypothalamus is the best site in which to which flight and unconditional escape behaviors can be

pursue systematic study of the properties of these cir- elicited represent the trajectory of fear circuitry, the

cuits. Such executive circuits (Figure 3) are likely to be major adaptive function of which is to respond to all

activated by sensory information concerning various external stimuli that have the potential of harming or

classes of environmental events (Figure 1), as well as hurting the body.

stimuli arising from internal states (autonomic reafferents

and homeostatic states of the body). Once activated, Rage. It is proposed that sites from which angry emo-

these circuits arouse and organize related arrays of soma- tional displays and affective attack can be elicited repre-

tic (Figure 2), hormonal, and visceral sensory-motor sent the location of a rage circuit, the major adaptive

processes. This paper will focus on the psychobehavioral function of which is to invigorate behavior when activity

attributes of these circuits. in the expectancy circuit diminishes rapidly as well as

when the body is irritated or uncomfortably restrained.

Expectancy. It is proposed that through the medial fore-

brain bundle of the lateral hypothalamus passes a gener- Panic. It is proposed that sites from which distress vocal-

alized "foraging-expectancy" circuit, which is sensitized izations and explosive agitated behavior can be elicited

by major homeostatic imbalances in the body and their represent the approximate trajectories of panic circuitry,

respective environmental incentives. The major adaptive the major adaptive function of which is to sustain social

function of this circuit is to produce a specific type of cohesion among organisms whose survival depends on

motor arousal - characterized by exploratory and investi- reciprocity of care-soliciting and care-giving behaviors.

gative (i.e., foraging) activities - which induces an animal The approximate hypothalamic locations of these cir-

to move from where it is to where it should be in order to cuits are depicted in the hemifrontal sections through a

consume the substances needed for survival. In artificial rat hypothalamus in Figure 2. It is assumed that these

experimental situations, this circuit can also mediate a four life-challenges (Figure 1) are archetypal, and that

highly energized form of electrical self-stimulation of the the evolution of such extensive systems in the brain was

brain. The term expectancy has been selected as the dictated by the adaptive advantage of rapidly acting

Figure 3. A simplified schematic of the trajectory of a transdiencephalic emotive command system on a parasaggital view of a rat

brain. The system collects various type of processed sensory information along its trajectory; for instance: (1) perceptual influences

from temporal and frontal lobes and various basal ganglia; (2) somatosensory inputs from the thalamus; (3) homeostatic inputs from

body-state detectors in the hypothalamus; (4) decoded olfactory, vomeronasal, and other perceptual inputs from midline thalamic

nuclei; and (5) simple sensory controls such as those arising from taste, touch, sound, and pain from lower brainstem levels. The

system is conceived as elaborating motor control by ascending influences (e.g., behavior sequencing mechanisms of basal ganglia) as

well as by descending control of emotion-appropriate autonomic and somatic reflex control circuits (6).

414 BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (1982)3

Panksepp: Psychobiology of emotions

command circuits, which could simultaneously recruit used to derive biological significance for such traditional

multiple body systems to meet major environmental behavioral concepts as reward and reinforcement, as well

emergencies. as for psychological states such as pleasure (see Panksepp,

The command-system construct has been much used 1981a, for review of the literature), the highly energized

in the analysis of stereotyped motor patterns in inverte- behavior of an animal electrically stimulating its own

brates, although it remains surrounded by many contro- lateral hypothalamus has remained enigmatic from such

versies (Kupfermann & Weiss 1978). The analogous na- perspectives. Although there may be considerable diver-

ture of "stimulus-bound" behaviors evoked by sity in the response topographies that individual animals

hypothalamic stimulation suggests that this principle can exhibit during self-stimulation (perhaps partially because

guide investigation of certain brain systems in mammals. of overlap with other emotional command systems), most

Although the neural trajectories and the exact functions of animals move forward, sniff intensely, and interact with

these circuits have yet to be mapped accurately, I shall many objects in the environment, especially those ob-

attempt to summarize existing knowledge of these puta- jects with strong intrinsic connections with the activated

tive emotive command systems. This review is highly circuits (e.g, odors). The invigorated explorato-

selective and emphasizes only materials most influential ry-investigative activity of such animals is just what

in my own thinking. A more comprehensive coverage of would be expected if a nonspecific circuit specialized for

past work related to many of these issues, can be found in the generation of incentive-directed (foraging) behavior

Panksepp (1981a). were activated. On a priori grounds, it would be advan-

tageous for activity in such a circuit to be amplified by

The "expectancy" command system. A unified executive internal need states as well as in response to positive

sensory-motor system for the mediation of explora- incentives, until contact with an appropriate consumma-

tion-approach-investigation (i.e., foraging) is proposed tory object was achieved and until internal homeostatic

to be isomorphic with neural circuits mediating electrical detectors provided satiety and inhibition of further

self-stimulation of the lateral hypothalamus (LH). In rats, foraging.

LH self-stimulation is characterized by increased forward Many of the unusual behavioral characteristics that can

locomotion with persistent sniffing, exploration, and ma- be obtained by stimulating this emotive system (e.g., the

nipulation of prominent objects in the environment unusual motivational characteristics discussed by Trowill

(Christopher & Butter 1968). Activity in this circuit may et al., 1969, and the behavioral "plasticity" described by

mediate the incentive attributes of rewards (Trowill, Valenstein et al., 1970) can be explained by the way in

Panksepp, & Gandelman 1969), and it is now known that which normal control gates in the circuit are superseded.

its cell are highly responsive to both external incentives Artificial activation of the circuit could override normal

and internal homeostatic imbalances (Oomura 1980; input signals, such as the inhibition that may arise di-

Panksepp 1981a; Rolls 1980). It is apparent that activity in rectly from consummatory acts as well as those arising

this circuit promotes an animal's capacity to seek out from replenishment of body needs. This would not only

biologically important stimuli in the environment, in part make stimulus-bound appetitive behavior more agitated

by invigorating motor behavior (Wayner, Barone, & than that normally seen in animals (i.e, foraging arousal

Loullis 1981) and also by modifying sensory acuity being sustained during reward consummation), but due

(Gellhorn, Koella, & Ballin 1955; Marshall 1979; Smith to the absence of accruing negative feedback signals,

1972). A fundamental requirement for survival is that an there would be a relative absence of satiation during self-

animal move from where it is to where life-sustaining stimulation of the circuit. Also, since the underlying

objects are located. Lateral hypothalamic stimulation system is nonspecific - subserving a general behavioral

potentiates the requisite behavioral tendencies in all function, which can be accessed by various positive en-

vertebrates studied, suggesting that a primitive executive vironmental incentives as well as by homeostatic need

system designed to trigger foraging activities courses detectors - enforced activation of this system could lead

through the forebrain bundles of the ventral dien- to a variety of specific stimulus—bound consummatory

cephalon. Although the behavioral expressions of arousal behaviors. These would be interchangeable, depending

not only on the availability of goal-objects but also on

in this circuit, such as genus-typical consummatory ac-

each animal's past foraging history. Furthermore, since

tivities (including feeding, drinking, gnawing, object car- the stimulation evokes a generalized emotive state, which

rying, hoarding, predatory aggression, and copulatory is artificially uncoupled from homeostatic inputs, the

behavior), may vary substantially across genera, the com- specific stimulus-bound behaviors observed during ar-

mand structure appears to have been comparatively re- tificial activation of the circuit could develop characteris-

sistant to evolutionary modification; this persistance sug- tics that are independent of momentary physiological

gests that an effective solution for coordinating bodily needs.

activities in response to archetypal survival needs was

sustained, functionally intact, during the diversification Expectancy was selected as a label for this neuronal

of vertebrate species into different ecological niches. network to emphasize the fact that this system mediates

However, the variety of genus-typical expressions of anticipatory appetitive behaviors and, presumably, the

activity in this system could explain the relative ease or corresponding subjective state in humans. In animals,

difficulty with which self-stimulation has been observed the activity of this system comes spontaneously under the

in various species - it being readily obtained in rats conditional control of correlated environmental cues

(because they exhibit energetic foraging) but not so read- (Clarke & Trowill 1971; Olds 1975; Rolls 1980). Lateral

ily in cats (because they exhibit a more restrained form of hypothalamic cells of rats fire with increasing frequency

stalking). when the animal is approaching food; they slow down

Although the phenomenon of self-stimulation has been dramatically when the animal starts to eat, but promptly

BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (1982)3 415

Panksepp: Psychobiology of emotions

resume rapid activity when its food is taken away (Ham- stances, rendering untenable the conclusion that this

burg 1971). Moreover, anticipatory enhancement of circuit simply triggers vacuous emotional displays.

motor activity induced by signals predicting food is Hypothalamic stimulation that generates affective at-

markedly attenuated by lateral hypothalamic lesions tack has been found to be aversive in cats (Nakao 1958),

(Campbell & Baez 1974). monkeys (Plotnick, Mir, & Delgado 1971), and rats

The postulated existence of a discrete circuit, designed (Panksepp 1971a). However, this circuit overlaps sub-

to energize appetitive foraging behaviors, readily ex- stantially with expectancy systems. Thus, both stim-

plains most of the behavioral changes that have been ulus-bound "affective" attack and agitated self-stimula-

observed following manipulations of the lateral hypo- tion (characterized by vigorous biting of the

thalamus and suggests a variety of behavioral and neu- manipulandum) can be obtained from hypothalamic

rophysiological hypotheses. At a behavioral level, manip- zones in which these systems presumably intermingle.

ulation of the system should generally modify the capacity Circuit overlap appears to be especially dense in tissue

of an organism to seek out biologically important stimuli just ventrolateral to the fornix columns, with the active

in its environment; and changes in the cellular activities field for rage extending ventrally and medially and the

of the system during appetitive tasks (e.g., Hamburg most sensitivefieldfor self-stimulation extending dorsally

1971) should generalize across different positive rewards. and laterally (Panksepp 1971a).

Perhaps the most objective physiological-behavioral in- Such mingling may complicate the dissection of under-

dicator of the state of this system in rats and other species lying circuitries, but it also points to the probable interac-

in which olfaction predominates would be the level of tion of these systems in the control of behavior. Adaptive

sniffing, not only during spontaneous exploration, but as considerations suggest that rage and expectancy circuits

correlated with environmental cues that predict environ- should strongly inhibit each other. A high level of forag-

mental rewards (Clarke, Panksepp, & Trowill 1971; ing and anticipation should dampen aggressive impulses,

Clarke & Trowill 1972). Indeed, for the past decade we whereas anger, and the resulting increased vigor of be-

have routinely identified lateral hypothalamic self-stim- havior, should be intensified when expected rewards are

ulation sites in anesthetized animals during surgery by not forthcoming. Thus, the increased responding ob-

monitoring sniffing evoked by electrical stimulation of

served at the beginning of extinction (i.e., the "frustra-

hypothalamic tissues. This measure could be used as a

straightforward behavioral assay for tapping the momen- tion effect") may be due to a release of the rage circuit,

tary state of the "foraging-expectancy" system. and selective damage to that circuit should reduce the

effect. Electrical stimulation applied to zones of overlap

This conception does not preclude the possibility that in these circuits may yield other unusual behavioral

specific neuronal circuits for the various motivational symptoms, for, typically, the two systems should not be

states (e.g., thirst, hunger, salt appetite, sexual behavior) active concurrently. For instance, self-stimulation at

exist in the hypothalamus. Homeostatic receptor systems these sites may be sensitive to stimulus duration, with

appear to exist in medial strata of the hypothalamus; these animals exhibiting vigorous responding for short pulse

systems presumably modulate activity in the generalized

durations and poor self-stimulation for long durations.

foraging system of the lateral hypothalamus and probably

have drive-specific interconnections to brain circuits Also, such animals may exhibit vigorous biting of the

which control consummatory acts (for a review, see Pank- manipulandum during self-stimulation.

sepp, 1981a). The most objective and easily quantified behavioral

indicators of activity in the rage system are vocal displays,

such as growling (Jiirgens & Ploog 1970), hissing, and the

The "rage" command system. The first hypothalamic potentiation of striking and biting behaviors (Flynn, Ed-

emotive system to be discovered was the one mediating wards, & Bandler 1971). This last measure has yielded

rage (Hess 1932; Ranson 1934), although the idea that this data that are highly consistent with the proposed reci-

system elaborated a true emotional state was not accepted procity of the rage and expectancy systems. Both the

by all (Masserman 1941). It is now clear that, even though activation of hypothalamic attack sites and the deactiva-

occasional electrode sites are encountered, which may tion of self-stimulation sites induce biting (Hutchinson &

generate affective displays apparently void of true emo- Renfrew 1978). Accordingly, with the use of such mea-

tional content, most electrodes placed in this circuit sures (summarized in Figure 2), clear predictions can be

generate an "affective" attack, which is well integrated made concerning the interactions that should be ob-

with environmental events (Nakao 1958). Indeed, in served during concurrent activation of "pure sites" within

monkeys, hypothalamically elicited aggression is di- these systems.

rected along dominance lines established prior to stim- Few investigations have sought to evaluate the effect

ulation. Robinson, Alexander, and Browne (1969) report on naturally occurring aggression of precise surgical

that submissive animals direct their attacks primarily damage to the rage command system at the hypothalamic

toward dominant ones, even to the point where stable level. This omission may be due, in part, to the fact that

dominance reversals are established. Delgado (1969) and lateral hypothalamic lesions precipitate a severe gener-

Alexander and Perachio (1973) have also found stim- alized amotivational syndrome (Ranson 1939; Strieker &

ulus-bound aggression to be guided by preexisting social Zigmond 1976), which makes it difficult to interpret

rank, but they observed attack to be directed most fre- experiments with large LH lesions (e.g., Karli & Vergnes

quently toward submissive animals. In general, most 1964; Panksepp 1971c). Still, no thorough investigation

recent studies indicate that artificial activation of the has been conducted that has behaviorally verified the

hypothalamic rage circuit precipitates aggression, which placement of electrodes before making of lesions; from a

is well integrated with an animal's normal life circum- command-system perspective, such a verification seems

416 BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (1982)3

Panksepp: Psychobiology of emotions

essential for deriving meaningful conclusions from lesion the hypothalamus has been recognized since Hess's pi-

work. oneering work, the fact that this behavior has not been

Although the rage command system is viewed as the extensively used to analyze the brain organization of fear

substrate for affective attack, diverse forms of aggression (and, hence, anxiety) suggests that it has not generally

can be distinguished in terms of their eliciting conditions been regarded as reflecting a true emotional state, but

(Moyer 1976). Presumably many of these stimuli con- rather only as a motor patterning mechanism. Such an

verge upon a common executive system, although certain interpretation has probably been reinforced by the many

forms of aggression, such as predation, need not arise failures to condition avoidance behaviors with hypothala-

from the activity of this system. The hypothalamic circuit- mically elicited flight as the unconditioned stimulus (e.g.,

ry mediating these behaviors has been distinguished Bower & Miller 1958; Roberts 1958; Wada & Matsuda

anatomically (Flynn 1976) and affectively (Panksepp 1970). But such conditioned avoidance has been obtained

1971a). Indeed, from the present perspective, quiet- by others (Delgado, Roberts, & Miller 1954; Nakao 1958),

biting attack forms of predatory aggression are considered and it may be essential to have "pure" fear sites, or

to be expressions of the foraging-expectancy system, or perhaps some concurrent stimulation of pain inputs, to

perhaps a mixture of activity in several systems. Similar- obtain efficient avoidance behavior. This may explain

ly, defensive aggression may be a mixture of concurrent why flight behavior obtained from the periventricular

activity in the fear and rage systems (Panksepp 1979a). gray has proved more readily conditionable (Wada, Mat-

suda, Jung, & Hamm 1970).

The "fear" command system. In comparison to lateral Even though "anxiety has been considered the alpha

hypothalamic expectancy and rage systems, the proper- and omega of psychiatry" (Delgado 1969, p. 131), hypo-

ties of circuits that mediate escape and flight behaviors thalamically elicited flight remains to be used as a general

(i.e., the fear emotive system) are poorly understood. model for analyzing neural substrates of anxiety. Nor has

Although the feeling of anxiety has been precipitated in any substantial attempt been made yet to analyze the role

humans by stimulation of several brain areas, especially of this neural system in the elaboration of natural avoid-

in the temporal lobe (Chapman 1958; Heath, Monroe, & ance and conditioned emotional responses. If such a

Mickle 1955; Jasper & Rasmussen 1958), the most ex- command system plays a cardinal role in the elaboration

pressive displays of fear in rats are observed during of fear, it is to be expected that selective damage to the

stimulation of the anteroventral hypothalamus (Panksepp circuit (as might be obtained with the use of behaviorally

1971a). Anxiety is also precipitated by electrical stimula- verified electrode placements) would markedly attenuate

tion of this zone in humans (Grinker & Serota 1938; the development of conditioned fear, as well as those

Monroe & Heath 1954). unconditional fear responses that are initiated by percep-

Hypothalamic sites that provoke flight surround the tual inputs rostral to the level of brain damage. There is

core system for which rage (threat behavior) is elicited (de substantial evidence that deficits in the elaboration of fear

Molina & Hunsperger 1962), and there appears to be result from damage to ascending projections of this sys-

substantial anatomical overlap and functional interaction tem in the amygdala (Kliiver & Bucy 1937; Ursin 1965).

between these systems. Accordingly, many of the behav-

ioral patterns elicited from this area are characterized by a The "panic" command system. This may be the most

mixture of flight and threat (i.e., defensive behavior). controversial of the emotive systems to be proposed in

Although stimulation of the intermediate zones typically this paper. It is not typically found among the traditional

elicits flight, defensive attack often ensues, if no avenue of lists of emotional responses attributed to the visceral

escape is available. Concurrent activation of the two brain via brain stimulation techniques. However, Cogan

systems with independently placed electrodes can yield (1802) and many others have entertained the idea that

synergistic effects, with either threat or flight being sorrow may be a fundamental emotion (Table 1), and, in

intensified (Hunsperger, Brown, & Rosvold 1964). the present context, sorrow (defined as the diminutive

The affective state elicited by stimulation of sites pro- form of panic, in the same manner that anxiety may be a

ducing flight is aversive, even though self-stimulation can diminutive form of fear, and anger a diminutive form of

also be obtained from some sites. However, self-stimula- rage) appears to reflect activity in a basic emotive system

tion behavior obtained from such electrodes is accom- of the brain. Our past work on separation-induced dis-

panied by flight responses (Panksepp 1971a). In rats, such tress in various species has been premised on the exis-

self-stimulation is characterized by crescendos of lever tence of such an emotion. The characteristic and univer-

pressing interspersed with frequent running away from sal emotional consequence of socially isolating young

the lever and energetic leaps upward. animals is protest, especially as reflected in the objective

Because the simple behavioral measure of aversion behavior of crying. This response appears to be mediated

does not readily discriminate between several trans- by an innate brain system that is attuned to the presence

hypothalamic emotive systems, the best indicator vari- and absence of social stimuli.

ables for the state of the fear system may be derived from Our work in this area (summarized in Panksepp, Her-

the response topographies of species-typical flight re- man, Vilberg, Bishop, & DeEskinazi 1980; Panksepp

sponses. In the rat, one highly characteristic response 1981b) affirms that similarities exist between the underly-

elaborated by this system is an upward leap. At anterior ing neurochemical dynamics of opiate addiction and of

lateral hypothalamic sites, this response is so systematic social dependence. This suggests that some of the neural

that it can be used quantitatively with repeated brief processes of this emotive system may involve brain

stimulations (Panksepp 1971b). opioids; this has been confirmed by brain stimulation

Although the existence of flight patterns elicited from studies (Herman 1979;.Herman & Panksepp 1981). Dis-

BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (1982)3 417

Panksepp: Psychobiology of emotions

tress vocalizations in guinea pigs can be elicited by evoked from the hypothalamus (e.g., Berntson 1972).

stimulating many opioid-rich sites, including the dor- Although the details of the underlying systems remain

somedial thalamus, ventral septal, and preoptic areas, to be determined, these putative command systems

and less dense zones in the amygdala and medial hypo- probably run from the mesencepahlon, through the re-

thalamus. However, these vocalizations follow the termi- ticular fields of the hypothalamus and, perhaps,

nation of brain stimulation, and therefore may not clearly thalamus, to basal ganglia and higher limbic areas (Figure

indicate the localization of the command circuit for this 3). Each command system probably emits ascending and

emotive system. Stimulus-bound distress calls have descending controls throughout its trajectory, not only to

been elicited in the vicinity of the central gray, suggesting interconnect with other behavior control circuits and to

that the executive system for this emotional state inter- bias sensory and motor processes, but also to coordinate

mingles with the other emotive systems at the level of the the activity of each system with homeostatic and autono-

medial mesencephalon. mic states of the body. Thus the trajectory of emotive

Although rats do not exhibit marked separation-in- command circuits through the hypothalamus may repre-

duced crying, stimulation of the anterior basal hypoth- sent a design feature that permits diverse bodily states to

alamus yields a stimulus—bound aversive response, be brought in line rapidly with behavioral demands.

which seems distinct from fear- and rage-related behav- Some of the above issues are highlighted in the sche-

iors. This response consists of a freezing reaction, accom- matized command network in Figure 3. Were this to

panied by apparently strong negative affect, which culmi- represent the command system for panic, it would be

nates suddenly in explosive behavior, during which the activated normally by social separation. It might bias

animal exhibits violent leaping about the test chamber ascending sensory projection areas in the cortex, tuning

(Panksepp 1971a). Unlike stimulus-bound flight, this certain systems to be especially sensitive to social stimuli;

behavioral response typically habituates rapidly, and, it might activate behavior sequencing mechanisms in the

with closely spaced trials, ever-increasing current levels basal ganglia specialized to generate discrete social sig-

are needed to reelicit the explosive component of the nals (e.g., MacLean 1981); it might establish hypoth-

behavior sequence. These behaviors may be homologous alamo-pituitary balances to increase ability to cope bet-

to the emotional disturbance known as "panic" attacks ter with stress; and perhaps, via descending influences, it

(Klein 1981), and this response may thereby indicate the might bias specific somatic motor tendencies, such as

hypothalamic location of the emotive command system increased agitation, distress vocalization, and the sensi-

that is attuned to social loss. It is noteworthy that similar tization of other care-soliciting behavior patterns. At the

explosive behavior patterns occur in addicted animals same time, overall autonomic balance may be shifted

during opiate withdrawal. toward parasympathetic dominance so as to conserve

Although activity of the panic system may be reflected bodily energy resources. The command system itself

in a variety of agitated behavioral patterns, separation- would be modulated by various sensory inputs along its

induced distress vocalization is currently the best indica- trajectory as illustrated in Figure 3. Since the system can

tor of arousal in this system. The activity of this emotive be accessed at various levels of the neuroaxis, learned as

system should also be expressed in the tendency of well as unconditional influences could modulate the ac-

animals to exhibit social cohesion, and decreased gregari- tivity of the command circuit at diverse points along the

ousness has been observed in rats following ventromedial trajectory of the system. Conceptualizing emotive cir-

and anterolateral hypothalamic lesions (Enloe 1975). Fur- cuits in this way would permit many rudiments of goal-

ther analysis of social cohesion and separation distress directed emotive behaviors to remain operational even

after damage to the various brain areas where stim- after substantial damage to both limbic forebrain and

ulus-bound crying and explosive behaviors can be elic- hypothalamic tissues (e.g., Ellison & Flynn 1968; Huston

ited will be needed to clarify the behavioral characteris- & Borbely 1974).

tics of this emotive system.

Neurochemistry of the emotive command sys-

tems. Whether the various emotive control systems mod-

Properties of emotive systems ulate the activities of output circuits via single- or multi-

ple-command transmitters remains unknown. From

Anatomy of the emotive systems of the visceral available evidence, dopamine and acetylcholine are rea-

brain. The actual neuronal trajectories of the proposed sonable candidates as key transmitters in the expectancy

emotive systems can only be sketched in broad outline. and rage systems respectively.

Although it is clear that lateral hypothalamic neuropil The catecholamine hypothesis of self-stimulation re-

contains widely ramifying, long-axoned systems, both ward has received substantial support (for reviews, see

ascending and descending, with multiple interneuronal German & Bowden 1974; Stein 1978; Wise 1978), and

feedback loops (Millhouse 1979; Palkovits & Zaborszky both norepinephrine and dopamine facilitate self-stim-

1979), our knowledge of functional circuits in such a ulation at various sites in the lateral hypothalamus as

reticular substance remains too imperfect to attempt determined by pharmacologic studies (e.g., Herberg,

filling in the details of system connectivities. The gross Stephens, & Franklin 1976; Phillips & Fibiger 1973;

anatomy of some systems can be surmised from anatomi- Zolovick, Rossi, Davies, & Panksepp 1982), even though

cal studies of self-stimulation and stimulus-bound appe- recent anatomical studies do not support the importance

titive (e.g., Gallistel, Karreman, &Reivich 1977; Roberts of norepinephrine in the self-stimulation phenomenon

1980; Routtenberg & Malsbury 1969; Wise 1978) and (e.g., Clavier, Fibiger, & Phillips 1976; Corbett & Wise

attack behaviors (Siegel & Edinger 1981) as well as from 1979). Stimulus-bound object-carrying (foraging)

studies analyzing the effect of brain lesions on behaviors evoked from the lateral hypothalamus is reduced follow-

418 BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (1982)3

Panksepp: Psychobiology of emotions

ing destruction of dopamine systems (Phillips 1975), and

pharmacological facilitation of brain dopamine activity

with d-amphetamine invigorates exploratory activities,

including forward locomotion and sniffing. A command

function for dopamine systems seems apt, because selec-

tive receptor agonists applied to the striatum can restore

behavioral competence in animals whose ascending DA

systems have been damaged (Marshall, Berrios, &

Sawyer 1980). This suggests that the system works as a

permissive response-biasing mechanism rather than as a

precise information-transfer system.

Acetylcholine may subserve a command function in the

rage system, since applying cholinomimetics into the

hypothalamus and amygdala can provoke rage responses

(Baxter 1968; MacPhail & Miller 1968; Myers 1964). The

observation that cholinergic agonists decrease self-stim-

ulation (Stark & Boyd 1963), whereas anticholinergics

increase such behavior (Pradhan & Kamat 1973) is con-

sistent with the proposed reciprocal inhibitory relations

between the expectancy and rage systems (Figure 2).

Additional evidence for such an interaction is provided by

the tendency of catecholamine depletion in the brain to

make animals irritable (Coscina, Seggie, Godse, &

Stancer 1973; Eichelman, Thoa, & Ng 1972; Nakamura &

Thoenen 1972). Furthermore, a reciprocal action of these

neurochemical systems is apparent in the nigrostria-

tal-striatonigral neuronal loop where dopamine appears

to inhibit acetylcholine cells, and acetylcholine, through

a GABA interneuron, inhibits dopamine cells (see Carls-

son 1965; Groves, Wilson, Young, & Rebec 1975; Iversen

1978; Pradhan & Bose 1978).

Command transmitter candidates for panic and fear

systems remain more elusive, but major inhibitory influ-

ences on these emotive systems may arise via the ben-

zodiazepine receptor (Braestrup & Squires 1977) and Figure 4. Biogenic amines that are widely dispersed through-

endorphin systems (see Panksepp et al., 1980, for re- out the brain may provide nonspecific excitatory and inhibitory

view). Further investigation of the various peptide net- control over emotive command circuits. The frontal sections

works of the limbic-enteric nervous system may reveal depict approximate locations of brain serotonin (5-HT) and

command transmitters for these circuits. norepinephrine (NE) systems at the mid-hypothalamic level as

If emotive systems have strong reciprocal interactions determined by autoradiographic localization of (14C), 5-HT,

with each other, a broad range of specificity in neu- and NE uptakes in the mouse brain. (Photomicrographs accord-