Professional Documents

Culture Documents

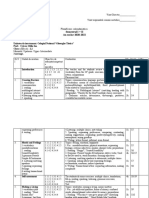

HG8005 Compilation PDF

Uploaded by

Zachary Thomas TanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

HG8005 Compilation PDF

Uploaded by

Zachary Thomas TanCopyright:

Available Formats

HG8005: Introduction to World Languages

Key Questions:

- What makes a world language a world language?

Common Assumptions of Origins world languages:

- State?

- Trade?

- Literacy?

- Classical languages?

- Prestige?

World Powers make World Languages:

Power of the State:

- Military conquests, religious, education, etc

- Examples include Hebrew, Arabic, Latin, Sanskrit, English

Latin:

- Despite vast Roman Empire, Latin did not dominate territory.

- Highlights along with examples of Egypt and China, that military expansion does not

necessarily facilitate language shift in conquered lands.

Chinese:

- Chinese was not displaced despite several successful invasions (Mongols, Jurchens,

Manchus, Turks etc)

Trade:

Phoenicians:

- Spread alphabet, taught Greeks how to read and write.

- Cultural and trading influence

- Despite this, Phoenician language had little influence by 500 CE.

Sogdian:

- Sogdian as language of Samarkand, along Silk Road, however, merchants would use their

customers’ languages such as Arabic, Chinese, Uyghur-Turkic and Tibetan.

- Language died out as Silk Road became less prominent.

Literacy:

Gaulish:

- Gauls literate in their own language.

- But converted to Latin after Roman conquest.

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 1

Classical Languages:

Aramaic (Syriac):

- Originally a nomadic language, but was also adopted by Assyrians, replacing Akkadian.

- Link language between Akkadian and Arabic

- Spoken by Jesus of Jesus of Nazareth, spread by disciples eastwards to China and India.

- Aramiac as classical and religious language.

Prestige:

- Prestige is common among successful languages (e.g. Sumerian, French, Latin)

- Prestige gained as result of wealth (e.g. Brazil’s gold rush in the 17th century, the spread of

Portugese to Brazil via economy rather than colonial administration)

What helps a world language become a world language?

- Prestige (wealth)

- Increase in population (settlement, population boom, etc)

- War and territorial expansion.

- Important resources (such as food sources i.e. Rice > large population growth)

Discussion questions:

- Do you think world powers make world languages? Explain.

- Considering the reasons given in today’s lecture, why is the English language considered a

world language?

- What is the difference between a contact language and a trade language? (Languages that

influence each other vs languages used only to bridge between)

- Why can’t literacy in a language always ensure that a language becomes a world

language?

- What exactly is the Aramaic paradox? (How does insignificant language become prominent

languages of administration?)

- In which power dimensions does the English language dominate other languages of the

world? And of all the factors discussed in today’s lecture, which do you think have most

contributed to the status of the English language today?

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 2

Week 2: The global language hierarchy

A Hierarchy of World Languages:

- By what measure to do consider the ranking of world languages?

Useful terms:

- L1: First language

- L2: Second language

- Lingua Franca: a language that is adopted as a common language between speakers

whose native languages are different

- Hierarchy: a system of organising or ranking items according to some status or authority

What makes a world language (so far…):

- A large population of speakers

- Association with linguistic prestige (usually wealth)

- Territorial expansion (‘Mergers and Acquisitions”)

But how are we to “rank” languages?:

Native Speakers:

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 3

Language Status (Official status by policy and recognition):

- “Official” languages are usually considered “protected”.

First and Second Language Speakers:

- L2 languages are only considered “second languages” rather than “foreign languages” if

they are used outside of isolated occasions (i.e. not just

However, these the data acquired by census do not adequately reflect to sociolinguistic reality of

all languages.

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 4

Languages as varieties:

- There is no consistent basis for making clear distinctions between languages, varieties of

languages and dialects of the same language

- The classical (socio)linguistic distinction revolves around the idea of mutual intelligibility

suggesting that if speakers of two different varieties understand each other then the

varieties concerned are instances of the same language, otherwise they are not.

- Hierarchies can be problematic because the categories used for selection (e.g. ‘L1’ vs

‘L2’) may not be clearly defined (e.g. When can one be proficient enough to be

considered a first language speaker? Can someone have 2 L1s, or 2 L2s? What about L3s

or ‘foreign languages’, do they count?)

Distinguishing one language from another:

- In terms of prestige, a language is a standard language (note that some languages are

more standard than others, e.g. standard French is more ‘standard’ than standard English)

- Mutual intelligibility criterion has some major problems, as noted in Hudson (1980: 35-

36):

- Criterion does not apply to popular usage—e.g. Scandinavian ‘languages’ and

Chinese ‘dialects’

- Mutual intelligibility is often a matter of degree, ranging from total intelligibility, down to

total unintelligibility

- Varieties may be arranged in a dialect continuum–If A is similar to B, and B similar to

C, then A and C are the same language. This ‘sameness of language’ is a transitive

relation, while ‘mutual intelligibility’ is an intransitive relation (A and C may not be mutually

intelligible)

- Mutual intelligibility is not so much a relation between varieties as it is about about

intelligibility between people. As such intelligibility depends on issues of motivation

Fromkin, Rodman and Hyams, 2003: 446

- When dialects become mutually unintelligible – when the speakers of one dialect group can

no longer understand the speakers of another dialect group – these “dialects” become

different languages.

- However, to define “mutually intelligible” is itself a difficult task. Danes speaking Danish and

Norwegians speaking Norwegian and Swedes speaking Swedish can converse with each

other. Nevertheless, Danish and Norwegian and Swedish are considered separate

languages because they are spoken in separate countries and because there are regular

differences in their grammars.

- Similarly, Hindi and Urdu are mutually intelligible “languages” spoken in Pakistan and India,

although the differences between them are not much different than those between English

spoken in America and Australia.

- On the other hand, the various languages spoken in China, such as Mandarin (Putonghua)

and Cantonese, although mutually unintelligible, have been referred to as dialects of

Chinese because they are spoken within a single country and have a common writing

system.

- Because neither mutual intelligibility nor the existence of political boundaries is decisive, it

is not surprising that a clear-cut distinction between language and dialects has evaded

linguistic scholars. (Fromkin, Rodman and Hyams, 2003: 446)

Hierarchies of Languages:

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 5

Americas:

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 6

Europe:

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 7

Asia:

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 8

Africa:

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 9

Pacific:

Hierarchy of Language Families:

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 10

What makes a world language?

- A large population of speakers

- Association with linguistic prestige (usually wealth)

- A substantial number of non-native speakers (the language functions as a lingua franca)

- It has official status in several countries

- It is used across several regions in the world

Discussion questions:

- What are language hierarchies?

- What do you think is a useful distinction between languages?

- Why is distinguishing between languages and dialects of the same language in terms of

mutual intelligibility problematic?

- Explain why census-data on languages can never be truly accurate?

- What do you think are the world’s top 5 languages in terms of prestige? On what objective

basis would you make your selection?

- If we use ‘foreign language learner’ as a category instead of only L1 and L2 speakers, how

does that change the dynamics of categorizing world languages?

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 11

Week 3: Global languages and ‘killer’ languages

Themes:

As language spreads, sometimes local languages are “killed” as foreign language takes

precedence

- Languages don’t die ...or do they?

- X as a killer language: What are the debates? - The language as a living being metaphor -

Sociopolitical dimensions - Who are the winners and losers of knowing and not knowing

world languages?

Key Terms:

Language death: When people stop speaking a particular language

Metaphors to talk about language:

If we say a language “dies” then what kind of metaphors do we use?

As a Living Entity

In this metaphor, we understand LANGUAGE in terms of it being a LIVING ENTITY.

E.g.:

- The English language is growing every year.

- French is alive and well in Africa.

- Mandarin will probably never die.

- The birth of Latin happened many centuries ago.

As a Physical Object:

In this metaphor, we understand LANGUAGE in terms of it being a PHYSICAL OBJECT.

E.g.:

- The Chinese took Cantonese to many countries.

- English has moved around the world.

- Mandarin is an enormous language.

- Some people think that the British own English.

Metaphor Usage:

- Conceptualising the world through the use of metaphors

- Embodiment hypothesis - abstract to non-abstract reality.

- We can only understand the physical world around us based on our perception of the world

and what we observe.

- Metaphors We Live By (George Lakoff 1980)

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 12

Linguistic Imperial and the English Language:

- Linguistic imperialism, or language imperialism, is a phenomenon that occasionally occurs

defined as "the transfer of a dominant language to other people".

- This language "transfer" comes about because of imperialism. The transfer is considered to

be a demonstration of power; traditionally military power but also, in the modern world,

economic power.

- Aspects of the dominant culture are usually transferred along with the language.

Robert Phillipson's 1992 book, Linguistic Imperialism, argues that the defining characteristics of

linguistic imperialism are:

- As a form of linguicism, which manifests in favoring the dominant language over another

along similar lines as racism and sexism.

- As a structurally manifested concept, where more resources and infrastructure are given to

the dominant language

- As being ideological, in that it encourages beliefs that the dominant language form is

superior to others, and thus more prestigious. These ideas are hegemonic and internalized

and naturalized as being "normal".

- As intertwined with the same structure as imperialism in culture, education, media, and

politics.

- As having an exploitative essence, which causes injustice and inequality between those

who use the dominant language and those who do not.

- As having a subtractive influence on other languages, in that learning the dominant

language is at the expense of others.

- As being contested and resisted, because of these factors

“Winners” and “Losers”

What is the outcome of Linguistic Imperialism? Does English have a globalising effect, or are

mother tongues under threat by English?

“The World is Flat”:

Thomas L. Friedman proposes 3 phases of Globalisation:

- First Phase (1500s-1800s): Countries as driver of globalisation (people and ideas

transferred)

- Second Phase (1800s-2000s): Companies as driver of globalisation. (Multinational

companies brought capital and trade)

- Third Phase (2000s-Present): Individuals as the driver of globalisation. (Internet allows

sharing of information around the globe)

“The world is flat”:

- Communications and Travel: Physical boundaries removed

- Opportunity: Employment opportunities and skills/talent pools more accessible.

As English facilitates this global movement, it is considered a leveller.

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 13

“The world is Spiky”

- Population: Urban areas house half of all the world’s people, and continue to grow in both

rich and poor countries.

- Patents: Just a few places in the world produce innovations. Innovations remain difficult

without a critical mass of financiers, entrepreneurs and scientists, nourished by world-class

universities and flexible corporations.

- Scientific Creations: The world’s most prolific and influential scientific researchers

overwhelmingly reside in westernised countries.

- Power Centres grow and absorb most of the world’s resources and talents.

Florida (2005, p.51) notes:

- So although one might not have to emigrate to innovate, it certainly appears that

innovation, economic growth, and prosperity occur in those places that attract a

critical mass of top creative talent.

- Because globalisation has increased the returns to innovation, by allowing innovative

products and services to quickly reach consumers worldwide, it has strengthened the lure

that innovation centres hold for our planet’s best and brightest, reinforcing the

spikiness of wealth and economic production

Florida (2005, p.51) warns further that:

- We are thus confronted with a difficult predicament. Economic progress requires that the

peaks grow stronger and taller.

- But such growth will exacerbate economic and social disparities, fomenting political

reactions that could threaten further innovation and economic progress.

- Managing the disparities between peaks and valleys worldwide—raising the valleys

without shearing off the peaks—will be among the top political challenges of the coming

decades.

The role of language:

Discuss

- Does language aid or inhibit one’s upward social mobility? If so, in what ways?

- Think about your own life, has knowing a ‘global language’ helped in your educational

prospects? Will knowing a global language help in your career prospects? Will knowing a

global language aid in your mobility on the global playing field?

- What is the role of ’smaller’ languages in globalisation and the global movement of people

and ideas? Or do they have no role to play? What about major regional languages, what is

their role?

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 14

Language Deaths:

Linguists have identified four types of language death:

- Sudden language death – When all the speakers of the language die or are killed (e.g.

Tasmanian)

- Radical language death – Similar to sudden death in its abruptness, but instead of the

speakers dying, they all stop speaking the language (e.g. for fear of political repression)

- Gradual language death – Most common way for a language to become extinct. It

happens when minority languages are in frequent contact with a dominant language and

with each generation there are fewer speakers (e.g. Cornish in the UK, Native American

language in the US, ‘dialects’ in Singapore and China)

- Bottom-to-top language death – describes a language that survives only in certain

contexts, such as a liturgical language (e.g. Latin)

Questions for discussion

- Is the English language really a ‘killer language’, as some people have said? Technology,

coupled with increasingly open economic markets and global trade, are factors fueling our

need to communicate and compete on a global playing field.

- What do you think are the implications this era of global human interaction has, and

continues to have, on language distribution and use, with respect to the social attitudes and

behaviour that underlie these changes?

- What do you think are the consequences of language death?

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 15

Week 4: French as a Global Language

French Language:

- French is the official language in some 30 countries

- For two hundred years, from the early 18th century to the early 20th, French was the

unrivaled language of international (and especially diplomatic) communication.

- It also played a crucial role in the establishment and subsequent functioning of the

institutions from which the European Union was to emerge.

French in the Plural:

- Native, northern varieties of French spoken in France (i.e. Metropolitan French) can be

historically tied to northern ‘Gallo-Romance’ and have been undergoing constant change

since the Middle Ages.

- One particular northern Gallo-Romance variety, itself a blend of many local varieties

has spread through annexation, conquest, and colonization first to other parts of

France, and then to many regions around the world.

- Thus what we, from an external point of view, will be calling ‘French’ is a foreign

language for millions of language learners around the world, and a heritage

language for many descendants of former colonists or emigrants who now

learn French as a foreign or second language (e.g. in the predominantly

anglophone areas of Canada).

- The standardized and codified variety referred to as ‘standard French’ has become the

official language in former French colonies around the world, such as the West African

countries of Senegal, Mali, and Cˆote d’Ivoire.

- Some varieties of French originated through colonization and immigration,

especially in the New World, and then blended with other local and immigrant

languages to give rise to entirely new and standardized language forms, as in the

case of Haitian Creole, now the official language of Haiti. (Language Contact and

Borrowing)

- Varieties that did not achieve the status of a ‘standard’ nonetheless continue to

show strong affiliation with French, and many of the structural properties of

French-based Creoles are attested in other varieties of French

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 16

Varieties of French:

- What is common to all these varieties? What unites all these ways of speaking and writing?

- It is common to label these different, more or less easily distinguishable, types or varieties

of French. Such a method is well known from studies of the history of French.

- What historians call northern Gallo-Romance was formed from Latin through

countless small steps and changes over centuries, and yet historians refer to the

chronological order of the formation of this group of varieties in terms of discrete

periods, such as ‘Old’, ‘Middle’, and ‘Modern’ French.

- Geographic diversity gave rise to many labels, such as northern and southern

Metropolitan French, Canadian, Québécois, Cajun, Belgian, and Swiss French, all of

which are commonly used in discussions and treatises about French.

- The French used in various social-stylistic settings will be called

- francais standard ‘standard French’

- francais familier ‘casual French’

- francais populaire ‘working-class French’,

- and francais vulgaire ‘vulgar French’

- Depending on stylistic and social characteristics of the uses of the language in real-life

situations.

Classical Latin, Vulgar Latin, Old French, Middle French:

- Classical Latin (75BCE - 3rd Century CE))

- Vulgar Latin (c. 100 CE)

- Old French (8th to 14th Century)

- Middle French (around 14th to 17th Century)

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 17

Francophonie (French-speaking world):

The French language has spread beyond France and Europe through conquests and colonization;

it is today a lingua franca.

- French is spoken natively by an estimated 80 million people in the world.

- It is ranked eleventh among the most widely spoken languages according to the

Summer Institute of Linguistics Ethnologue Survey (Grimes 1996).

- The number of French-speaking people is around 280 million, if so-called second-

language speakers are also counted.

Status of French:

French as an official native language is spoken on five different continents: Europe, the Americas,

Africa, Asia, and Oceania (See week 2 slides).

- The largest number of native francophone speakers, about 71 million, lives in Europe, and

most of them are in France.

- Approximately 45% of Belgians and 20% of the Swiss are also native speakers of

French.

- In the Americas, the largest francophone community is in Quebec, Canada,

representing about 5.9 million speakers (Canadian Census 2001).

- The largest francophone population in Africa is concentrated in the western

Sub-Saharan regions of the continent, with French as an official or administrative

language in more than ten different countries from Mauritania and Senegal to Gabon

and the Congo (see Figure 1.1 ).

- In the Indian Ocean, the islands of Madagascar, Seychelles, and Mauritius stand out

as the largest francophone communities, with about 23% of the local population

(18.4 million people) able to speak French.

- In North Africa, French has the status of a ‘privileged’ foreign language, and

several decades after decolonization it remains the dominant language of

higher education for roughly 33 million people. About 57% of the inhabitants of

Algeria (French colony 1848–1962), 41% of Moroccans, and 64% of Tunisians

(under French Protectorate 1912–1956 and 1881–1955, respectively) can speak

French.

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 18

- The largest francophone community in the Middle East is in Lebanon (under

French mandate 1920–1941), totaling about 1.5 million speakers.

- In Asia, Vietnam and Cambodia have roughly 375,000 francophones.

French in the Modern World:

- At the beginning of the seventeenth century, French was still a language that admitted

much variation, even at the highest levels of literary and legal usage.

- Over the following centuries, to the present day, the state has intervened more and more to

establish a standard and to spread the use of that standard.

- At the same time, the territory under the control of the state expanded, first along the

borders and then increasingly overseas as the French empire grew.

- Paradoxically, just as the power of the state and other social forces within France imposed

a single standard form of the language, the expansion of the empire would lead to new

diversity in the French spoken around the world

Standardisation in 17th Century:

- Early in the seventeenth century François de Malherbe critiqued the poetry of Philippe

Desportes, condemning the choice of vocabulary, stylistic excesses, and illogical or

inconsistent grammatical structures (Brunot 1891).

- Malherbe’s severe limitations on poetic language were not without critics, but his group of

admirers were well connected.

- They began meeting weekly at the home of the Parisian nobleman Valentin Conrart (1603–

1675).

- Louis XIII’s secretary, Cardinal Richelieu, took note of these meetings, and proposed

that the group take on an official role within the state, so that language might be governed

by the state as all other matters. Thus the Académie française came into being in 1635.

The Academie Française:

- The Académie française originally had one goal: to make French “pure, eloquent, and

capable of being a medium for discussion of the Arts and Sciences” (Article 24 of the

Académie’s bylaws).

- It would accomplish this task through two means: the composition of four types of

reference works on language (a grammar, a dictionary, a guide to rhetoric, and a

guide to poetics) and the correction of literary works that would be submitted to the

Académie (of which only one was ever published).

- The Académie felt more comfortable in pursuing the other charge it was given: to provide a

series of reference works relating to the French language. The Académie produced the

first of these, a dictionary, in 1694.

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 19

French Language Policy Enforcement:

- National inspection of schools began in the 1830s. Inspectors were dismayed at the

quality of French of the students, and of the teachers.

- In the 1880s the institution of free, mandatory education, under the control of the state

rather than of the church, further advanced the spread of the national language.

- Soldiers were threatened with extended tours of duty if they had not learned to speak

French during their first tour.

- By the early twentieth century, all of these factors had the cumulative effect of making

virtually all French people capable of speaking French

French Dialects in Modern World:

- The interaction between French dialectal speakers and the African languages of the slaves

brought to the Caribbean islands, French Guiana, and Louisiana formed new creole

languages in those regions.

- French colonies were established in North Africa, West and Central Africa, and in the South

Pacific in the nineteenth century.

- Each expansion of territory resulted in the creation of new varieties of French, and in

the borrowing into Metropolitan French of terms used in the local languages of the

conquered people.

- Even with the loss of much of that Empire in the second half of the twentieth century,

French is today an official language in more than thirty countries. One of the enduring

legacies of the French Empire is the conflict between the Metropolitan French

standard and local varieties in official and educational settings.

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 20

Week 5: Spanish as a global language

Language contact from the perspective of Spanishisation (How Spanish has changed local

language varieties)

The Spanish Language:

- Spanish is the official language in some 20 countries

- Spanish is the spoken L1 of over 400 million people in Spain, Equatorial Guinea, and 18

states in Latin America; it is also widely used in the United States, Israel, and in Western

(former Spanish) Sahara.

- The standard is based on, and almost identical with, the Romance speech of Old Castile,

which is why non-Castilians tend to call it castellano rather than español and sometimes

resent its privileged status;

- for according to the Spanish constitution, all Spaniards have the obligation to learn it

and the right to use it, which has made both its use and its name serious and even a

dangerous political issue in areas where many people are native speakers of another

language (e.g. Catalan; Basque).

Spanish in South (Latin) America:

Nativisation of Spanish:

- Term used for describing the kinds of changes a language goes through as a result of

the contact it has with other languages, regions and cultures. The study of nativization

tries to account for the description of the changes the parent (transported) language

undergoes.

- With regards to Spanish (and other world languages), when the language comes into

contact with a culture or a speech community where it has not been spoken before, it may

undergo certain changes that reflect that culture.

- As this kind of adoption takes place the imported language goes through a

development cycle, which may involve, at the heaviest level, a restructuring of the

language itself.

- The result of nativization is a unique variety of Spanish, as demonstrated by examples such

as the different varieties of Spanish in South America and Chavacano in The Philippines.

- Changes are manifested at the phonetic/phonological, lexical (vocabulary), syntactic

(grammatical) and pragmatic (discourse) levels.

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 21

Spanish in South American:

- There is great diversity among the various Latin American vernaculars, and there are

no traits shared by all of them.

- A Latin American "standard" does, however, vary from the Castilian "standard" register

used in television and the media.

- South American Spanish pronunciation varies from country to country and from

region to region, similar to how English pronunciation varies from one region to another.

- Some notable (shared) features include more frequent use of Anglicisms which more

common in Latin America than in Spain, due to the stronger and more direct US influence;

linguistic influences (e.g. vocabulary) from other South American languages to

describe specific social and cultural situations, geography, and fauna and flora; variation in

pronunciation (see video).

- The different dialects and accents do not block cross-understanding among the educated.

This is called the acrolect (or educated variety). Meanwhile, the basilects (vernacular

varieties) have diverged more.

- Language variety as a means of identifying a social class with class hierarchy in coloised

regions.

- Accents used to draw distinction between racial and social classes.

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 22

Spanish in Asia:

Philippines Spanish:

- Spanish was the language of government, education and trade throughout the three

centuries (333 years) of the Philippines being part of the Spanish Empire (until 1898)

and continued to serve as a lingua franca until the first half of the 20th century.

- Use of Spanish has declined, but new developments in the Philippines may be reversing

this trend. (e.g. In 2007, former President Gloria Arroyo signed a directive in Spain that

require the teaching and learning of the Spanish language in the Philippine school system

starting in 2008).

- The Under-Secretary of the Department of Education circulated a Memorandum on the

"Restoration of the Spanish language in Philippine Education". Schools mandated to offer

Spanish classes.

- General resurgence of learning Spanish among Filipinos. Reasons include interest in the

language and historical identity (namely their written, cultural history), interest in

their connection to the Spanish-speaking world, etc.

- Observed increase in number of Filipinos learning Spanish for business purposes.

Chavacano (Phillpine Spanish Creole):

- The variety spoken in Zamboanga City, located in the southern Philippine island group

of Mindanao, has the highest concentration of speakers.

- On 23 June 1635, Zamboanga City became a permanent foothold of the Spanish

government with the construction of the San José Fortress.

- The military authorities imported labor from Luzon and the Visayas and the construction

workforce consisted of Spanish, Mexican and Peruvian soldiers, masons from Cavite (who

comprised the majority), sacadas from Cebu and Iloilo, and those from the various local

tribes of Zamboanga like the Samals and Subanons.

- Language differences made it difficult for one ethnic group to communicate with

another. To add to this, work instructions were issued in Spanish. The majority of the

workers were unschooled and therefore did not understand Spanish but needed to

communicate with each other and the Spaniards.

- A pidgin developed and became a full-fledged creole language still in use today as a

lingua franca and/or as official language, mainly in Zamboanga City.

Chavocano itself has different varieties:

- To what extent is Chavocano a ‘dialect’ of Spanish?

- Chavocano and Standardised Spanish are both varieties of the same language

- However, the reality of language use and politics has disjunctions.

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 23

Spanishisation of Phillpine Languages:

- The influence of a world language can also be seen on the languages they come into

contact with.

- This influence is seen most commonly at the lexical (vocabulary) level, when, for example,

vocabulary is ‘borrowed’ from Spanish and incorporated into a particular local language or

language variety (e.g. Tagalog).

- The term for this is linguistic borrowing

- The X-ization of a language is complex, and may manifest at various levels (e.g.

through transliterated loan words— ’chocolate’ in Mandarin is … ?, grammar, phonology

and phonetics, and discourse patterns)—more on this later in the course.

- Think about the different ways a world language has influenced another language you

speak or know well. Can you identify examples of how this influence is manifested at

various levels in the language (e.g. vocabulary, grammar, phonology, discourse)?

- Can you provide definitions (with your own examples) of the following terms:

- (i) Nativization of Spanish

- (ii) Spanishization

- (iii) Linguistic borrowing

- What is difference between a basilect and an acrolect? Can you give examples?

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 24

Week 6: Arabic as a global language

What makes a world language?

- Number of Speakers L1/L2

- Usage and official status of the language

- Prestige, Classical usage, religious aspect.

- Literacy in language

Arabic: The Triumph of Submission

- Modern Standard Arabic is an official language of 26 states, the third most after English

and French

- Arabic is a Semitic language closely related to Aramaic and Akkadian

- Its records go back to North Arabian inscriptions of the fourth century BCE, spoken

mainly by Bedouin and pastoralists

- Within 25 years of the prophet Muhammad’s death in 632, they had conquered all of the

Fertile Crescent and Persia, and thrust into Armenia and Azerbaijan

- Penetrating advance to the West: Egypt fell in 641 and the rest of North Africa as far as

Tunisia in the next decade

- Two generations later, by 712, the Arabic language had become the medium of

worship and government in a continuous band of conquered territories from Toledo

and Tangier in the west to Samarkand and Sind in the east. No one has ever explained

clearly how or why the Arabs could do this

- “An appeal is usually made to a power vacuum in the east (where the Roman/ Byzantine

empire and the Sassanian empire of Iran were just recovering from their exhausting war),

and the absence of any power to organize resistance in the west” Ostler (2005, p. 93)

Political Changes:

- Politically, the Arab campaigns destroyed the hold of the Roman, now Byzantine,

empire on most of the eastern Mediterranean

- Despite their efforts to take Constantinople, this centre of Roman power survived, and lived

on in Christian defiance for another eight centuries (until start of Ottoman empire, more on

the Turks below)

- Farther east, the Arabs overran Armenia but did not convert it

- More significant was the Arabs' termination of Sassanian power in Iran and the mountains

of Afghanistan

- But in many instances Arabic did not spread with the spread of Islam into the

communities where the religion took hold (e.g. Persian in Iran—ironically Persian was

spread with the spread of Islam towards the east)

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 25

Ostler:

- Finally, consider the Turks, nomad forces who came into contact with Arabic, not through

being conquered by its speakers, or proselytize by them, but through taking the initiative

and conquering them. Coming from the north-east, they first dominated the eastern areas of

Muslim power, moved to take the centre in Baghdad, and later expanded to be in effective

control of the whole Dar al-Islam. Once they had conquered, there were none to match the

Turks in their adherence to the Muslim faith.

- Nevertheless, they held onto their language even as they accepted the religion. And

they had one other linguistic effect: they also slackened the grip of Arabic on Persia

as a whole. The Turks had first encountered the world of Islam through the Persian-

speaking area of central Asia. In a sense, they saw it only through a veil of Persian

gauze. And so, when the Turks began to exercise influence, Persian returned as

official administrative language to Iran with Arabic restricted more and more to

religious functions (Ostler, 2005, p. 101).

Linguistic Changes:

Linguistically, the immediate effects were comparable to the political ones:

- Arabic established itself as the language of religion, wherever Islam was accepted, or

imposed

- In the sphere of the holy, there was never any contest, since Islam unlike Christianity did

not look for vernacular understanding, or seek translation into other languages

- The revelation was simple, and expressed only in Arabic

- Islam was a religion that insisted on public rituals of prayer in Arabic, and where the

muezzin's call of the faithful to prayer, in Arabic, has always punctuated everyone's day

- In the long term there was a subtle linguistic limit on Arab success, or rather on the success

of Arabic

- Arabic progressed from the language of the mosque to establish itself permanently as the

common vernacular of the people only in countries that had previously spoken some

related language, one that belonged to the Afro-Asiatic (or Hamito-Semitic) family (In other

words, language shift was not difficult)—Remember what we said before about

shifting to a related language

- This Afro-Asiatic zone included the Fertile Crescent, where Arabic replaced Aramaic;

Egypt, where it overwhelmed Coptic; Libya and Tunisia, where it finally supplanted

Berber and erased-or merged into-Punic; and the Maghreb (the north of modem

Algeria and Morocco), where it also pushed Berber back into a set of smaller pockets

- In Africa, Mauritania in the west, and Chad and Sudan in the east; here Arabic spread

later through trade contacts, and would have replaced some Chadic and Cushitic

languages

- In all these regions where Arabic became the dominant language, a characteristic state of

what is called diglossia (explanation below) has set in, with a single classical form of

Arabic used as an elite dialect, but different local varieties- no more mutually

understandable than the Romance languages of Europe, established in everyday

speech.

- Classical Arabic is close to, but not quite identical with, the language of the Qur'an

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 26

Diglossia

- A situation in which two languages (or two varieties of the same language) are used in

different contexts within a community, often by the same speakers. The term is usually

applied to languages with distinct ‘high’ (formal, classical) and ‘low’ (colloquial) varieties,

such as Arabic

- The Arabist William Marçais used the term in 1930 to describe the linguistic situation in

Arabic-speaking countries

The Arabic Language:

- Arabic is a West Semitic language

- West Semitic was traditionally divided into two groups, namely the Canaanite and the

Aramaic, with Hebrew and Syriac as the main literary languages

- The earliest attestations of Arabic are a number of proper names borne by leaders of

Arab tribes mentioned in Neo-Assyrian texts (see next slide)

- Various North Arabian populations have to be distinguished, differing by their

language and their script, and above all by their way of life

- While populations of merchants and farmers were settled in towns and oases, semi-

nomadic breeders of sheep and goats were living in precarious shelters in the vicinity of

sedentary settlements, and true nomads, dromedary breeders and caravaneers, were

moving over great distances and living in tents. Different forms of speech have been

distinguished, both urban and Bedouin.

Pre Islamic North and Eastern Arabic:

- A variant of the South Arabian monumental script, that had developed from the common

Semitic alphabet

- Lihyānite--the local dialect of the oasis of al-'Ulā, ancient Dedān, that had its own

king in the 6th/5th century B.C.

- Nabataean Arabic--represented by a few inscriptions in Aramaic script

- Thamūdic--graffiti are named after Thamūd, one of several Arabian tribes

mentioned in the Assyrian annals (Tamudi)

- Safaitic--inscriptions that date from the 1st century B.C. through the 4th century A.D.

They are so called because they belong to a type of graffiti first discovered in 1857 in

the basaltic desert of Safa, southeast of Damascus

- Hasaean-- the name given to the language of the inscriptions written in a variety of

the South Arabian script and found mainly in the great oasis of al-Hāsa', in the east

of Saudi Arabia

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 27

Pre-Classical Arabic:

- Both urban and Bedouin, are described to a certain extent by early Arab philologists which

have preserved some data on the forms of speech in the Arab peninsula around the 7th-8

th centuries A.D.

Classical Arabic

- Classical Arabic is the language of Pre-Islamic poetry, probably based on an archaic

form of the dialects of Nadjd, in Central Arabia, shaped further to satisfy the needs of

poetical diction and metre, and standardised in the Abbasid empire, in the schools of al-

Kūfa and Basra'. Already before Islam, perhaps as early as ca. 500 A.D., this language was

employed by poets whose vernacular may have differed strongly from the archaic Nadjdi

dialects, thus testifying to the emergence of an Arabic diglossia (more later), at the

latest in the 6th century A.D

Neo-Arabic or Middle Arabic

- Neo-Arabic or Middle Arabic is the urban language of the Arab Empire from the 8th

century A.D. on, emerged from the Pre-Classical Arabic dialects

Modern Arabic

- Modern Arabic dialects, spoken by hundreds of millions, are not descendants of Classical

Arabic but rather its contemporaries throughout history, and they are closely related to

Neo-Arabic

*Owens (2006, pp. 77-78) notes:

- After over 150 years of research on the topic, there is no meaningful comparative

linguistic history of Arabic

- The distinction Old-Arabic-Neo-Arabic was postulated on the basis of a logical matrix, not

one grounded in comparative linguistic theory

- Arabic is better conceptualized not as a simple linear dichotomous development (the

Old vs New split), but rather as a multiple branching bush, whose stem represents the

language 1,300 years ago. Parts of the bush maintain a structure barely distinguishable

from its source (in linguistic terms, parts in which the Old-New dichotomization is

irrelevant)

- Other parts of the bush are marked by striking differences, differences which

distinguish them as much from other parts of the appendages as from the stem

- It is a complex organism which resists a simple description in terms of a dichotomous

structure

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 28

Arabic-Speaking Populations:

Arabic Varieties:

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 29

Language Shift:

- Throughout history, linguistic communities the world over often have made decisions,

consciously and unconsciously, to what extent they will continue using a certain linguistic

variety or whether to replace it with another variety

- Language shift describes a situation when a community replaces (i.e. shifts) their

use of a linguistic variety in favour of another linguistic variety

- Language death is sometimes associated with language shift (i.e. total language

shift)

- Much research done on language shift in the 1980’s, especially in immigrant communities in

Australia and the US, to understand the processes by which immigrants to Australia

and in the US shifted from their home languages, to English

- Language shift is often studied together with language maintenance

- Many studies were conducted on immigrant communities and how they shifted to English in

the US and Australia.

Factors assisting quicker shift include (see Paulston, 1994):

- Family/community generation is a factor, with shift speeding up after successive

generations, once the process starts

- Easy access to target language and language policies promoting/prescribing use of the

target language

- Easier to shift to linguistic ‘neighbours’ (languages in same language family)

- Persecution (based on religious or ethnic associations)

- Language attitudes play a role (linguistic ‘loyalty’, identification of a language as a part of

the cultural heritage of a community etc)

Questions:

- From the brief story of Arabic presented in your lecture, what conclusion can be drawn

about how and why Arabic can be considered a world language? Can you add one more

reason (besides ‘large population of speakers’, ‘territorial expanse’, etc) to what helps make

a world language a world language, based on the story of Arabic?

- What is language shift? Explain using your own examples.

- Usefulness, language policies

Classical Variety vs Vernacular Variety:

- Classical Arabic is the variety that is spread together with Islam.

- Diglossia is prevalent in the Arab world.

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 30

Week 6: Chinese as a global language

Chinese Language:

- Mandarin, Cantonise, Hakka, Teochew, etc

- Linguistic Varieties or ‘dialects’

- Shared culture, shared writing system

- Mutual intelligibility or non-mutual intelligibility

- Chinese/Sinitic languages

- Pronunciation

- Vocabulary

- Grammar

Chinese around the world:

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 31

- Mandarin is the official language of Greater China (including the Republic of China,

Taiwan

- Mandarin is one of the official languages of Singapore as well as one of six official

languages of the United Nations

- Cantonese and Mandarin both the official spoken varieties of Hong Kong and Macau

- Sizeable Overseas Chinese communities in the US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand,

Cambodia, Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Philippines, Mauritius, Brazil, Peru and

Venezuela—although language variants differ in these communities

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 32

Chinese as an official language

- Chinese has an official status in the following territories:

- Mainland China

- Hong Kong SAR

- Macau SAR

- Wa State (unrecognized state in Myanmar)

- Singapore

- Taiwan

- Despite the large number of Chinese speakers in greater China, there are relatively few

speakers outside of China, and the language has almost no official status outside of

the greater China region

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 33

Is Chinese a world language?

Ostler (2005: 116-117) notes:

- Egyptian and Chinese are both vehicles of single cultural traditions of immense

prestige. For each, the role as universal language was uncontested in their homeland.

By the dawn of their recorded histories they were already established over the central zone

of the lands where they were to be spoken.

- Each maintained this position of solitary and basically unchanging dominance for an

awesome period of over three thousand years, or more than 120 generations.

- Yet, in each case, despite the fame and prestige of the culture among neighbours,

who were often dominated politically by these powers, the languages never assumed any

role as lingua franca beyond the territory that they considered their homeland.

- Chinese, for all the political reverses and atrocities its people have suffered at the

hands of heartless foreigners in the last two centuries, has never been stronger than it is

today.

- Its speakers make up one sixth of the world's population, and it has three native

speakers for every one of English.

- Nevertheless, over 99 percent of them live in China, so it cannot be considered a

world language-unless China is your world. Those who speak it often call it ‘zhong guo

hua’, 'centre realm speech': in that at least Chinese ethnocentrism is undiminished.

- There is still time to consider those forces that have kept the Chinese realm so firmly, and

compactly, centred on its traditional homeland: will they still prevail in the modem

world?

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 34

Week 9: English as The World Language

The status of English in the world language system:

- The number of L2 speakers denote possible usage as a Lingua Franca.

The foreign language learning market:

Coulmas (2017, p. 19) notes:

- (1) Languages spoken by many speakers are attractive for learners and literary producers

(authors as well as publishers);

- 2) Choices of foreign languages to study are not entirely determined by economic

considerations, but to a very large extent;

- (3) Traditional curricula, cultural attractiveness, and emotional motives play subsidiary roles

which, however, can also be assessed as values that have a bearing on language

competition;

- (4) Foreign language learning is thus the component of the world language system that is

most susceptible to market forces and, therefore, most amenable to economic modelling of

supply and demand and agents making choices.

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 35

Coulmas (2017, p. 20) offers a list of competing forces in the world language system:

- demographic strength;

- international standing;

- official status;

- market as foreign language;

- standardization and literary development;

- ideological support structure

Official status of English:

- English has an official status in some 64 countries

From English to Englishes:

- ‘World Englishes’ broadly refers to localized forms and varieties of English found across the

globe (so-called ‘nativized’ varieties of English)

- The global spread and use of localized varieties of English has usually been discussed in

terms of three (or four) distinct groups of users:

- (1) Native language users (English as a Native Language, or ENL users);

- (2) Second language users (English as a Second Language, or ESL users);

- (3) Foreign language users (English as a Foreign Language, or EFL users);

- (4) as well as users of English as an International Language (or EIL)

- Usage and Status impact the group of users

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 36

World Englishes:

World Englishes as a field of study includes:

- (1) New literatures in English (e.g. the work of Wole Soyinka; Arundhati Roy; and Salman

Rushdie, to name a few);

- (2) The ‘narrower’ or ‘pluricentric’ approaches highlighting the ‘sociolinguistic realities’ as

well as ‘bilingual creativity’ of so-called Outer Circle societies in Kachruvian studies (cf.

model of concentric circles in Kachru 1988);

- (3) The ‘wider’ application of the term that subsumes ‘varieties-based’ approaches, the

study of discourse, corpus linguistics, the sociology of language, studies in language

contact (creole and pidgin studies), critical linguistics, and futurological approaches.

Kachru’s ‘Three Circles of English’ (1985):

- The circles represent “the type of spread, the patterns of acquisition and the functional

domains in which English is used across cultures and languages” (Kachru, 1985, p.12).

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 37

A brief history of the English language:

- Old English (500-1100)

- Middle English (1100-1500)

- Early Modern English (1500-1800)

- Late Modern English (1800 – now)

- Romance languages are offspring of Latin—genetically related

- Early forms of English and German had proto-Germanic as ancestor

- Latin and proto-Germanic are ancestors of Indo-European – Thus, Germanic languages are

genetically related to the Romance languages

- These languages were all regional dialects once

- How do we prove they were related? One clue is the sound correspondences, as in /f/-/p/

between many Romance languages and English:

The Great Vowel Shift:

- A major change in English resulted in new phonemic representations of words and

morphemes (1400-1600)

- The seven long, or tense, vowels of Middle English underwent the following change

- The high vowels [i:] and [u:] became the diphthongs [aj] and [aw], while the long vowels

underwent an increase in tongue height, as if to fill in the space vacated by the high vowels.

[a:] was also fronted to become [e:].

- The effect of the Great Vowel Shift is the reason for the many inconsistencies in English

spelling today, as many spellings reflect how words used to be pronounced before the

Great Vowel Shift.

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 38

Major changes in the English language:

1) Phonological Rules and the Great Vowel Shift

2) Morphological changes (e.g. Old English case system)

3) Syntactic changes (Subject Verb Object —Subject Object Verb + SVO in Old English)

4) Lexical changes (borrowings, loss of words etc.)

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 39

British and American English: two powerful varieties:

- What is the standard variety of English in the UK called, and what is the standard English in

America called?

- Who speaks standard British English and standard American English?

- What do you think has been the impact of English English and standard American English

on the global spread of English?

Standard Southern British (where 'Standard' should not be taken as implying a value judgment of

'correctness') is the modern equivalent of what has been called 'Received Pronunciation' ('RP'). It

is an accent of the south east of England which operates as a prestige norm there and (to varying

degrees) in other parts of the British Isles and beyond (IPA 1999)

British and American spelling around the world:

Pronunciation: Vowels and diphthongs

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 40

Changing American ‘standards’:

- Standard American has changed from one dialect to another, at one point Northeastern

accent was popular (Bette Davis—”peetah”— Franklin Roosevelt’s “Fee-ah itself”

speech…) and all actors had to learn it

- After WW2 the Midwestern accent became popular (e.g. Walter Cronkite)—nobody wanted

to sound ‘uppity’ anymore

- 1940’s radio and television presenters were trained in this accent and popularised this

accent

- American English is actually a convenient cover for a bundle of accents

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 41

Week 10: English as the World Language II

English in Southeast Asia:

Substrate:

A substrate is a language that influences an intrusive language that supplants it. The term is

also used of substrate interference; i.e. the influence the substratum language exerts on the

replacing language (e.g. The influence of Chinese on English in Singapore).

- Typically, a Language A occupies a given territory and another Language B arrives in

the same territory (brought, for example, with migrations of population).

- Language B then begins to supplant language A: the speakers of Language A abandon

their own language in favor of the other language, generally because they believe that it

will help them achieve certain goals within government, the workplace, and in social

settings.

- During the language shift, however, the receding language A still influences language B

(for example, through the transfer of loanwords, place names, or grammatical

patterns from A to B).

Southeast Asia:

Lim (2014, p. 2) notes that SEA is characterized by diversity on a number of fronts:

- In terms of settlement type, a number of countries are either former colonies of Britain

(Malaysia and Singapore, with Brunei a British protectorate) or of America after earlier

Spanish colonization (the Philippines), and the remainder had other European colonizers

or, in one case (Thailand), none at all;

- This means that just one-quarter of the SEA countries would be categorized as Outer

Circle countries in Kachru’s (1992) classification, and the rest would be considered

in the Expanding Circle;

- Outer Circle territories include Malaysia, the Philippines, and Singapore

- All other SEA countries can be considered Expanding Circle territories

- The main reason for this rests on the historical background of English (British and

American colonialism), along with the status of English (official language policies in

these regions);

- With the Outer Circle countries, differences in language and education policies established

after Independence, including resources for English education and proportion of population

having access to the language, also had consequences for the status and spread of English

and for how the variety has nativized;

- Geopolitical factors, such as size of country, urban‒rural divide, economic growth, and so

forth, have also affected the spread, penetration, and development of English;

- The substrates are many, and are for the most part genetically unrelated to

English, with typologically different grammars from diverse language families

such as Austronesian, Dravidian, and Sinitic;

- The ecologies of emerging Englishes are always dynamic. What is perhaps notable for

Asian (and African) Englishes is how rapidly their situations have changed and continue to

do so, in some cases within a matter of decades. Post- Independence policies in the late

twentieth century in SEA have had significant and swift impact on the ecologies, and

consequently on the structure, of SEA Englishes.

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 42

Malaysia:

- At Malaysia’s Independence in 1957, English was given the status of an ‘alternate

official language’ alongside Malay as sole national language, which, renamed Bahasa

Malaysia (‘Malaysian language’) in 1963, was established by the National Language Act

as the sole official language in 1967.

- With the Malay First policy in schools adopted between 1969 and 1983, all English-

medium schools were converted to fully Malay-medium schools, starting from 1971.

By 1983 Malay was the medium of instruction in all schools.

- In 1971 the Education Act was also revised to extend the shift to tertiary education. In the

national schools, although English was retained as a compulsory school subject, it was no

longer a requirement to obtain a pass in English in order to get a grade one in the school

leaving exam. All in all, these policies resulted in a decline in the proficiency and use of

English.

- In 2003, English was readopted as the medium of instruction for science and

mathematics, in order to keep abreast of scientific and technological developments

- In 2009, the Ministry of Education announced a switch back to Malay as a medium of

instruction for mathematics and science, identifying the poor success rate of the

implementation of English for this

- As a consequence of these largely anti-English and inconsistently implemented language

policies since Independence, English has not taken a real foothold in the country, with

the exception of the small minority of urban, upper-class, Englisheducated

Malaysians.

- The proportion of the population having a working knowledge of English is

relatively low for a former British colony, approximately 20% of the population

of over 22 million (McArthur 2003, p. 335), and of these a small minority of some

400,000 would be first language speakers (largely from the middle and upper

classes), and the remainder second-language users (Hickey 2004: 563)

Philippines:

- The Philippines, at Independence in 1946, chose to represent in their choice of official

languages both English and Filipino.

- Their bilingual education programme (BEP) was introduced in 1974, with English as the

medium of instruction in the teaching of science and mathematics, and Filipino in the

teaching of all other subjects.

- The 1987 Constitution established Filipino as the official language of the country and

acknowledged the spread of Filipino as the de facto lingua franca amongst ethnolinguistic

regional groups in the country.

- English use has not diminished in education and society (Tupas 2009, p. 26), being

dominant in many domains of public discourse and the print media (Gonzalez 1982, 1991)

(though television, radio and films are heavily Filipino).

- The Philippines is considered an English-speaking country, with 65% of the population of

over 80 million able to understand spoken and written English, 48% able to write English,

and 32% able to speak it (Social Weather Stations 2006).

- It has recently been said to be the third largest English-speaking nation.

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 43

Singapore:

- By 1952, 43% of school enrolment was English-medium, with the numbers registering for it

overtaking those for Chinese-medium education by the end of that decade (Doraisamy

1969).

- Since 1965, English was also made one of the official languages of the country, with three

‘local’ languages identified as official languages to represent the three official races—

namely, Malay (also the national language) for the Malay ethnic group, Mandarin for the

Chinese, and Tamil for the Indians.

- English was retained for pragmatic reasons, as Singapore’s leaders inherited not only a

system of government that relied heavily on the use of English and the population viewed

the language as an important resource for socioeconomic mobility (Lim et al. 2010, p. 3).

- English remains the primary working language, the language of law and administration.

Moreover, English became the medium of instruction in all schools by 1987 (Lim 2010, p.

29–30), as well as in all institutes of higher education.

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 44

Common Characteristics of Southeast Asian English:

Of 11 L2 Asian English varieties, the following features were identified in around 75% of these

varieties (Adapted from: Kortmann 2010, p. 408-9):

- (Adapted from: Kortmann 2010, p. 408-9resumptive/shadow pronouns (This is the wall

which I claimed it yesterday)

- zero past tense forms of regular verbs (I talk for I talked)

- invariant non-concord tags (innit/in’t it/isn’t as in They had them for breakfast, innit?)

- invariant don’t for all persons in the present tense (She don’t like him)

- lack of inversion in main clause yes/no questions (You understand me?)

- irregular use of articles (I have the headache, They have a three rooms)

- wider range of uses of the progressive (What does she wanting?)

- never as preverbal past tense negator (He never say (=He never said))

- Inverted word order in indirect questions (I’m thinking what are you going to say)

- lack of inversion/lack of auxiliaries in wh-questions (What you saying?)

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 45

English in Singapore:

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 46

Five key articles on Singapore English:

- Platt (1977), ‘The sub-varieties of Singapore English: Their sociolectal and functional

status’: A lectal model

- Acrolect: Distinctive stress patterns, vowel length and vowel quality, reduction of

consonant clusters.

- Mesolect: The above features plus lack of final stops, glottal stops, variable plural

marking, 3rd person, copula, definite and indefinite articles.

- Basilect: A higher percentage of the above-mentioned features, plus use to as

aspect marker, got as locative verb, have as existential verb.

- Gupta (1989), ‘Singapore Colloquial English and Standard English’: A diglossic model

- Standard English: ‘To be regarded as a proficient English-user by this community, an

adult has to be able to speak and write Singapore Standard English.’ (Gupta 1989, p.

34)

- For Gupta, ‘Standard English’ here is defined by a mastery of such features as:

- Aux + Subj in questions;

- Past tense and participle marking, 3rd person singular marking;

- Plural and possessive marking;

- The use of certain complex verbal structures

- [M]y work ... has made me conclude that ... there [are] two grammatically distinct

varieties of English in Singapore, both of which are used by proficient speakers of

English. There are, of course, at the same time differing levels of proficiency in

English – but I would like to distinguish the scale of proficiency from this use of two

different varieties by the same speaker. Proficient adult speakers of English in

Singapore use two sharply different kinds of English depending on the

circumstances: I refer to these two varieties as (a) Singapore Colloquial English

(SCE) and (b) Standard English (StdE). The pattern of usage ... can be referred to

as diglossic

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 47

- Pakir (1991), ‘The range and depth of English-knowing bilinguals in Singapore’: The

expanding triangles model:

- Alsagoff (2010), ‘Hybridity in ways of speaking: The glocalization of English in Singapore’:

Globalist and localist features

- The Cultural Orientation Model:

- The variation of English in Singapore is clearly shaped by forces intricately

bound with negotiations in identity formation and presentation. [...] The focus

on features such as pragmatic particles, or bare verbs or nouns is common in

the Singapore English research literature. However, the argument that

language and culture are inextricably linked suggests that global-local

cultural orientations may also be linguistically realized in a multitude of

ways, and not restricted to discrete phonological, grammatical or lexical

features. (p. 125)

- Glocalization [...] presents language and identity as intertwined, and as

fluid – just as language is used to present, re-present and construct and re-

construct identity, it, in turn, is similarly constructed by its speakers in the

service of identity and cultural representations, communication and

interactions. Glocalization has presented variation within Singapore

English as styleshifting, suggesting a fluidity of movement within a

dynamic multidimensional space, rather than as diglossic code-switching

between two well-bounded varieties. (p. 126)

- Leimgruber (2012), ‘Singapore English: An indexical approach: Data transcription

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 48

What is Singapore English (and what is ‘Singlish’)?:

1. What is Singapore English from a world Englishes perspective?

- ‘Singapore English’ is an established variety of Asian English, which has been

described and analysed in a large body of research and publications.

- What makes a variety of English? (Butler, 1997):

- A standard and recognizable pattern of pronunciation (accent).

- Particular words and phrases … regarded as peculiar to the variety

(vocabulary).

- The history of the language community (history).

- A literature written in that variety of English (creative literature).

- Dictionaries and style guides (reference works).

- [Also, in many other studies, patterns of grammatical variation]

2. What is ‘Singlish’/Singapore English in ideological terms?

- A simple definition of ‘ideology’ refers to a ‘set of beliefs characteristic of a social

group or individual’. In the case of language ideologies, these are often very powerful

beliefs that often exert covert influences on language policies and language

management.

- What ideologies influence the discussion and understanding of ‘Singlish’ in

contemporary society?

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 49

3. What is Colloquial Singapore English (or ‘Singlish’) in linguistic terms?

- Varieties of English are typically described with reference to distinctive features at

the major levels of linguistic analysis:

- Phonetics/phonology (accent, pronunciation)

- Lexis (vocabulary)

- Morphology and syntax (grammar)

- Semantics and pragmatics (meaning)

- Orthography (writing system, spelling and punctuation)

- Is there only one form of ‘Singlish’ or are there multiple forms? If so, this may involve

multiple linguistic descriptions.

- How do people in Singapore actually speak?

-

- What is their ‘vernacular’ (in the Labovian sense)? How can we access and describe

vernacular language use?

Is English a world language?

1. Does English have a large population of speakers?

2. Is it associated with linguistic prestige (usually wealth)?

3. Does English have a substantial number of non - native speakers (and the language

functions as a lingua franca)?

4. Does it have an official status in several countries?

5. Is English used across several regions in the world?

6. Is it directly associated with a world/big religion?

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 50

Week 11: Language, Globalisation, and the Asian region

There are no clear connections between the role of globalisation and what makes a World

Language.

Globalisation and modernity:

Globalisation is generally perceived as international integration in terms of economics, politics, and

cultural exchange; However, publications on the topic tend to be oversimplified; Scholte (2005: 84)

defines globalisation as:

- A respatialization of social life [which] opens up new knowledge and engages key policy

challenges of current history in a constructively critical manner. Notions of ‘globality’ and

‘globalisation’ can capture, as no other vocabulary, the present on-going large-scale growth

of transplanetary – and often supraterritorial – connectivity.

- Views at times overlap with ‘internationalization’, ‘liberalization’, ‘universalization’, and

‘westernization’, though this does not imply equivalence

There is a need to interpret the dynamic nature of language contact situations within a

globalisation framework, as iconic and indexical dimensions of signs are part of the context in

which signs function (Blommaert 2006)

Arjun Appadurai—Modernity at Large (1996):

1) Appadurai provides a framework for the cultural study of globalisation, especially in terms

of mass migration and electronic mediation patterns;

2) He also considers the ways in which images – through popular culture and self-

representation – are circulated globally (e.g. through the media) and then borrowed to take

on new local meanings and interpretations.

3) Appadurai applies Anderson’s (1983) concept of ‘imagined communities’, whereby mass

media and its interconnectedness with mass migration affects and influences

peoples’ imaginations, and in turn (re)defines notions such as neighbourhood, nation,

and nationhood;

- He points out that: [the] new global cultural economy has to be seen as a complex,

overlapping, disjunctive order that cannot any longer be understood in terms of

existing center-periphery models, [and nor] is it susceptible to simple models

of push and pull (in terms of migration theory), or of surpluses and deficits (as

in traditional models of balance of trade), or of consumers and producers (as

in most neo-Marxist theories of development). (Appadurai, 1996, p. 32)

4) Appadurai postulates a current (or modern) notion of globalisation which compels a

thinking of culture without space;

5) Some studies of English as a global language have addressed the problem highlighted by

Appadurai above. As Blommaert (2010, p. 28) states:

- When we address globalisation, however, we address translocal, mobile markets

whose boundaries are flexible and changeable. And this is the theoretical challenge

now: to imagine ways of capturing mobile resources, mobile speakers and

mobile markets. A sociolinguistics of globalisation is perforce a sociolinguistics of

mobility, and the new marketplace we must seek to understand is,

consequently, a less clear and transparent and a messier one.

6) World languages (especially English), occupy a multifaceted complexity often as

transplanted languages;

HG8005 Global Languages, Local Culture | Course Notes Compilation | 51

7) Pennycook (2007, p. 19) points out:

- English colludes with multiple domains [of globalisation], from popular culture to

unpopular politics, from international capital to local transaction, from ostensible

diplomacy to purported peacekeeping, from religious proselytizing to secular

resistance.

8) The spread, flow, and use of English, for example, requires important considerations

regarding the dynamic nature of language and globalisation (Graddol and Saville,

2012);

9) Language flow can be understood as a metaphor describing the constant and continuous

movement of people and languages and language varieties across particular spaces;

10) As groups migrate and regroup in new regions or territories, new histories are

constructed and cultural reproductions are created;

11) There is difficulty in adequately researching communities that are in constant flux.

The sociolinguistics of globalisation and English:

1) Blommaert (2010) argues that with different varieties of English, producers (and

consumers) of these varieties often orientate themselves toward a status hierarchy,

in which English occupies the top of this hierarchy;

2) Blommaert (2010, p. 189) also points out explicitly that [this] is an orientation to a

transnational, global hierarchy, reinforced by the state’s ambivalent and meandering stance

on English’.