Professional Documents

Culture Documents

V Reterritorialization: V The Myth of Nature 93

Uploaded by

sergiocobosOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

V Reterritorialization: V The Myth of Nature 93

Uploaded by

sergiocobosCopyright:

Available Formats

All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright

v reterritorialization

The Myth of Nature

Substance is eternal.

— Lucretius, De rerum natura

But these are all landsmen; of weekdays pent up in lath

and plaster—tied to counters, nailed to benches, clinched

to desks. How then is this? Are the green fields gone?

What do they here?

— Herman Melville, Moby Dick

Mythologized nature is now architecture’s most precious commodity,

canonized and invested with messianic powers. As a code of conduct,

allegiance to the myth of nature has permeated every crevice of media

culture, overtaken the sanctions of practice, and addressed itself to

the alleviation of our collective guilt. At the same time, the illusion

that emerging technologies will recalibrate our relationship with

nature, and that architecture can be their handmaiden, holds us in

thrall. Yet much like the object and subject myths discussed in previ-

ous chapters, these current guises of nature mask a set of practices

Copyright @ 2012. The MIT Press.

and products that defer to the hegemony of capital, and continue to

support our highly stratified, postindustrial economy.

Historically, nature has been cast as an enigmatic “other.” But

primordial nature as that which preceded (and precedes) civilization

law.

v the myth of nature 93

EBSCO : eBook Academic Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 2/22/2019 10:10 PM via

UNIVERSIDAD DE CASTILLA-LA MANCHA

AN: 439526 ; Stoner, Jill.; Toward A Minor Architecture

9304.indb 93 1/31/12 1:49 PM

Account: s6088100.main.eds

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright

and culture is necessarily mythic; it disappeared at the very moment

that it became so explicitly defined. Positioned in opposition to cul-

ture, the concept of nature is itself a cultural invention—constructed

around the vicissitudes of human history alternately as antagonist or

ally, as a subject of fear or of pathos, cast into exile or placed in pro-

tective custody.1 Nature’s place in the discipline of architecture is par-

ticularly striking: it is both celebrated and excluded. The acanthus

leaves of a Corinthian column and Peter Zumthor’s wet stone walls

celebrate nature; caulking applied to windows and levees constructed

around delta cities are intended to exclude nature’s most powerful

forces. The floods of Hurricane Katrina forced a massive exodus from

New Orleans, a deterritorialization accompanied by a reterritorializa-

tion by the flood waters themselves. “Yea, foolish mortals,” Melville

cautioned, “Noah’s flood is not yet subsided,”2 and years after the

storm the question persists: do we reclaim New Orleans from the

Gulf waters once again, or retreat to higher ground? In anticipation

of ongoing climate change and the inevitability of rising water, one of

the great debates is whether to include or to exclude—to periodically

recalibrate our plans for harbor cities as the ice caps continue to melt,

or to preempt the effects of the flood with engineered barriers against

rising tides.

“Yet this great flux is made of all such things as you have

known or might have known. This vast irregular sheet

of water, which rushes by without respite, rolls all colors

toward nothingness. See how dim it all is.”

Copyright @ 2012. The MIT Press.

—Paul Valéry, “Eupalinos, or the Architect”

These are the waters of the mythic river Ilissus. Here Valéry places

Socrates and Phaedrus, their dialogue adhering to strict Platonic

form, but their ephemeral selves transported by literary license to the

law.

94

EBSCO : eBook Academic Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 2/22/2019 10:10 PM via

UNIVERSIDAD DE CASTILLA-LA MANCHA

AN: 439526 ; Stoner, Jill.; Toward A Minor Architecture

9304.indb 94 1/31/12 1:49 PM

Account: s6088100.main.eds

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright

afterworld of the early twentieth century.3 Mere shades in death, and

with all eternity before them, they meet in that dim landscape where

“nothing is clear.” Phaedrus introduces the subject of architecture

through his remembrances of an architect named Eupalinos,4 whose

precepts become the provocation for an extended debate on the dis-

tinctions between constructing and knowing. We soon discover that

Socrates’ fascination with these questions is not merely academic. In

that realm where ideas flow freely without the support of substance,

he expresses some regret for his mortal life of pure thought, and won-

ders how he might have contributed as an architect.5

At the close of the dialogue, Socrates delivers a tour de force

soliloquy in which he casts himself as “the Anti-Socrates” and imag-

ines himself in the role of “the Constructor.” He begins by describing

the circumstances before God intervened:

Note, Phaedrus, that when the Demiurge set about making

the world, he grappled with the confusion of Chaos. All

formlessness spread before him. Nor could he find a single

handful of matter, in all this waste, that was not infinitely

impure and composed of an infinity of substances.

Here is the quintessence of Deleuzian smoothness. Socrates continues:

He valiantly came to grips with this frightful mixture of dry

and wet, of hard and soft, of light and gloom that made up

this chaos, whose disorder penetrated into its smallest parts.

He disentangled that faintly luminous mud, of which not a

single particle was pure, and wherein all energies were

Copyright @ 2012. The MIT Press.

diluted, so that the past and the future, accident and

substance, the lasting and the fleeting, propinquity and

remoteness, motion and rest, the light and the heavy were as

completely mingled as wine with water, when poured into

one cup. The Great Shaper was the enemy of similitudes

law.

v the myth of nature 95

EBSCO : eBook Academic Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 2/22/2019 10:10 PM via

UNIVERSIDAD DE CASTILLA-LA MANCHA

AN: 439526 ; Stoner, Jill.; Toward A Minor Architecture

9304.indb 95 1/31/12 1:49 PM

Account: s6088100.main.eds

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright

and of those hidden identities that we delight to come

upon. He organized inequality. . . . He divided the hot from

the cold and the evening from the morning; He squeezed

out from the mud the sparkling seas and pure waters, lifting

the mountains out of the waves, and portioning out in fair

islands whatever concreteness remained.

The world is organized, stratified. That original “nature” created by

the demiurge is defined by its segmented quality—materials and

binary attributes separated and in opposition. Socrates describes an

orderly yard of building materials, ready and desiring to be set in

motion again. He has set the stage for the art of architecture to begin:

But the Constructor whom I am now bringing to the fore

finds before him, as his chaos and primitive matter, precisely

that world order which the Demiurge wrung from the

disorder of the beginning. Nature is formed, and the

elements are separated; but something enjoins him to

consider this work as unfinished. . . . He takes as his starting

point of this act, the very point where the god had left off.

—In the beginning, he says to himself, there was what is:

the mountains and forests; the deposits and veins; red clay,

yellow sand, and the white stone which will give us lime.6

Architecture has evolved as the art of putting things together, of

collage and montage and of making assemblages. In the beginning it

was stone upon stone, primitive assemblages of a single material.

Eventually, ornament and color were applied to tell stories that

Copyright @ 2012. The MIT Press.

brought elements of nature into a deliberate, cultural narrative.

Builders still worked this reciprocity between nature and culture at

the time that Valéry wrote his dialogue. But as we have continued to

build more (and more) buildings, more (and more) separate products

have been brought into play. With each advance in product

law.

96

EBSCO : eBook Academic Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 2/22/2019 10:10 PM via

UNIVERSIDAD DE CASTILLA-LA MANCHA

AN: 439526 ; Stoner, Jill.; Toward A Minor Architecture

9304.indb 96 1/31/12 1:49 PM

Account: s6088100.main.eds

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright

development (also thoroughly profit-driven), architectural details

have involved greater numbers of materials and things. Within every

building, proliferating layers of construction employ their separate

syntaxes. This language has become heavy with modifiers and clauses,

overwrought with the implications of competing aesthetic and func-

tional decisions. These complex grammars are the thinly veiled rela-

tions of a competitive marketplace.

Our challenge is to deterritorialize and reterritorialize, to engage

the minor mode within these complicated, oversaturated assem-

blages, and to approach that point where “language stops being rep-

resentative in order to move toward its extremities or its limits.”7 In

order for us to do this, a complicated building must be made to reveal

its simple, “natural” form.

There are peregrine falcons uptown, downtown and

midtown. They zoom through the canyons of Wall Street

and perch on the gargoyles of Riverside Church.

—New York Times, June 15, 1995

In 1972, only a few peregrine falcons existed east of the Mississippi

River, and none in the west.8 Our pervasive use of DDT had caused

the chemical to seep into the birds’ habitats and hence into their food

supply, causing eggshells to thin and crack before hatching. When

wildlife biologists proposed transplanting the few remaining birds to

high-rise buildings in urban centers, where the food supply (mostly

pigeons) would be free of pesticides, their plan was greeted with skep-

Copyright @ 2012. The MIT Press.

ticism. Yet over the course of the next two decades, more than fifty

cities in the United States and Canada eventually participated in the

program, depositing pairs of birds (the falcon mates for life) on such

clifflike promontories as the Brooklyn Bridge in New York, Toronto’s

Sheraton Hotel, and the Fisher Building in Detroit. In 1992, with

law.

v the myth of nature 97

EBSCO : eBook Academic Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 2/22/2019 10:10 PM via

UNIVERSIDAD DE CASTILLA-LA MANCHA

AN: 439526 ; Stoner, Jill.; Toward A Minor Architecture

9304.indb 97 1/31/12 1:49 PM

Account: s6088100.main.eds

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright

over nine hundred pairs counted, the peregrine falcon was removed

from the national endangered species list.

If we did not know better, we might think that the falcons had

appropriated our colloquialisms of urban canyon and urban jungle

for their own purpose. But the falcon’s reading of this urban land-

scape is literal, not metaphorical. World cities of commerce are

formed by clusters of tall and densely packed buildings, built topog-

raphies that echo the natural cliffs, canyons, and plateaus that form

the falcons’ indigenous habitats, where they can dive at speeds of up

to 200 miles per hour for their prey. These raptors responded with-

out prejudice or preconceptions to the physical conditions of vertical

distance and craggy footholds; they perceived the simple forms.

Their responsiveness to what all assumed would be an alien landscape

has much to teach us about how to redefine “nature” in the context

of the contemporary metropolis.

Copyright @ 2012. The MIT Press.

The falcon introduces porosity into the city—not the shadowy

porosity of Benjamin’s Naples, but instead a city shot through with

wildness, a city reducing its mass by introducing small pockets of

decidedly nonhuman use. Animals operate according to their own

time frame, and the nesting box on the roof of the PG&E building

law.

98

EBSCO : eBook Academic Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 2/22/2019 10:10 PM via

UNIVERSIDAD DE CASTILLA-LA MANCHA

AN: 439526 ; Stoner, Jill.; Toward A Minor Architecture

9304.indb 98 1/31/12 1:49 PM

Account: s6088100.main.eds

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright

in San Francisco sat empty for seventeen seasons before being discov-

ered and claimed by a falcon pair in 2003. Since then, a web cam has

entertained us with the daily urban life of falcon parents George and

Gracie and their yearly offspring.9

Driven from their habitat, driven to the brink of extinction, the

falcons’ transplantation to the city is a reterritorialization of the first

order.10 Reterritorialization erases property lines and other abstract

geometries; it introduces mobility and blurs urban segments into

newly integrated ecologies. And remarkably, neither falcons nor

humans need deterritorialize one another. For us as for the falcon, the

constructed city can take on a palpable and primal existence, empty

of symbols, meaning, history, and memory. To engage the practice of

minor architecture is to reterritorialize by first partly forgetting those

values firmly affixed to provenance (history) and to preservation

(materiality). In the case of the falcons, the anthropomorphic and

anthropocentric interests that have historically defined the function

of the city itself are partly relaxed; the intellect of urbanism as a dis-

cipline embraces its sensual, better half.

In a story by Anita Desai,11 a sick man named Basu is suffering

from the stifling heat of his apartment bedroom. He asks his wife to

bring his mattress up onto the roof of their building. The bedroom is

deterritorialized, the roof reterritorialized. Under the stars, he gets his

first good sleep in weeks. As day begins to break, he delights in the

view of pigeons silhouetted against the morning light. Basu leaves his

stuffy bedroom; the falcon leaves the contaminated mountains.

Though they approach from opposite directions, each finds a certain

wild territory on an urban rooftop. In both cases, reterritorialization

Copyright @ 2012. The MIT Press.

is an exit to the outside.

law.

v the myth of nature 99

EBSCO : eBook Academic Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 2/22/2019 10:10 PM via

UNIVERSIDAD DE CASTILLA-LA MANCHA

AN: 439526 ; Stoner, Jill.; Toward A Minor Architecture

9304.indb 99 1/31/12 1:49 PM

Account: s6088100.main.eds

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright

Architecture is a collection of ruins that closes at six o’clock.

—Jennifer Bloomer and Robert Segrest, “Without

Architecture”

Ruins are the evidence of things become obsolete, projects halted,

capital exhausted. It is no longer simply the collapse of a building

that makes it a ruin; it is the collapse of a symbolic order. How sad

that architecture (the “useful” art) becomes the physical, visible man-

ifestation of that which is no longer useful.

In the second half of the twentieth century, the abandoned

buildings of obsolete industries, tough high-ceilinged spaces once the

sites of blue-collar work, were quite suddenly romanced and coveted

as living spaces for an urban gentry. More recently, unfinished high-

rise towers in Bangkok, Shanghai, and Caracas have attracted the

attention of bloggers and photographers as vivid “follies” of globaliza-

tion. The more banal (and completed) buildings of the neoliberal

economy have yet to receive much similar attention; but in 2003 the

pathos of dead and dying malls attracted the interest of a group in

Los Angeles, who sponsored a national competition inviting archi-

tects to speculate on the malls’ physical and cultural futures.12 Even

more recently, the six thousand Circuit City retail stores that were

closed in 2009 became the site for a collaborative thesis project in

the Department of Architecture at the University of California,

Berkeley.13

These are but a few of many possible contexts for minor archi-

tectures, settings not so much for salvage operations as for nearly

authorless insurgencies. As an archaeology without artifacts, the pro-

cess of spatial reclamation is more low-tech than high, and privileges

Copyright @ 2012. The MIT Press.

the passions of labor over the physics of materials. At the same time,

other forces may be brought into play—forces of weather, systems

of drainage, even migration patterns of birds. These may yield

new concepts for workplaces not so “pent up in lath and plaster,”

more open to outside air and with more connections between

law.

100

EBSCO : eBook Academic Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 2/22/2019 10:10 PM via

UNIVERSIDAD DE CASTILLA-LA MANCHA

AN: 439526 ; Stoner, Jill.; Toward A Minor Architecture

9304.indb 100 1/31/12 1:49 PM

Account: s6088100.main.eds

You might also like

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- 100 IC CircuitsDocument34 pages100 IC CircuitselektrorwbNo ratings yet

- A. A. Allen The Price of Gods Miracle Working PowerDocument52 pagesA. A. Allen The Price of Gods Miracle Working Powerprijiv86% (7)

- Heat Sink Capacity Mesurment in Inservice PipelineDocument13 pagesHeat Sink Capacity Mesurment in Inservice PipelineSomeshNo ratings yet

- A History of Architecture - Critical RegionalismDocument38 pagesA History of Architecture - Critical Regionalismsarath sarathNo ratings yet

- DOGMA - Obstruction A Grammar For The CityDocument7 pagesDOGMA - Obstruction A Grammar For The CityEmma Vidal EscalanteNo ratings yet

- Din332 PDFDocument4 pagesDin332 PDFmateo100% (2)

- Polynesian MigrationsDocument2 pagesPolynesian Migrationskinneyjeffrey100% (1)

- CardiomyopathyDocument1 pageCardiomyopathyTrisha VergaraNo ratings yet

- Topos January 2018Document116 pagesTopos January 2018Kurt Wagner100% (1)

- METRO Otherscape PlaytestDocument101 pagesMETRO Otherscape PlaytestDave Satterthwaite100% (1)

- Architecture Without Nature: Timothy MortonDocument3 pagesArchitecture Without Nature: Timothy Mortonmarcelo grosmanNo ratings yet

- Vdocuments - MX - t02 Essay Parasitic Architecture PDFDocument11 pagesVdocuments - MX - t02 Essay Parasitic Architecture PDFΦοίβηΑσημακοπούλουNo ratings yet

- The Man-Environment Paradigm and Its Paradoxes: January 1973Document6 pagesThe Man-Environment Paradigm and Its Paradoxes: January 1973Maria AretNo ratings yet

- El Pan Mental n2 ADocument2 pagesEl Pan Mental n2 Aapi-233189745No ratings yet

- Planet of The Monsters - TANK - Crosman / Di LeoneDocument5 pagesPlanet of The Monsters - TANK - Crosman / Di LeonechuazinhaNo ratings yet

- An Interview With Julia Watson by ChrisDocument6 pagesAn Interview With Julia Watson by ChrisLaura VelandiaNo ratings yet

- The Unreal Estate Guide To Detroit: Properties In/of/for Crisis by Andrew HerscherDocument2 pagesThe Unreal Estate Guide To Detroit: Properties In/of/for Crisis by Andrew HerscherHarsh SawhneyNo ratings yet

- Perspecta 38 - After Forms - Lebbeus Woods - 2006Document9 pagesPerspecta 38 - After Forms - Lebbeus Woods - 2006Tarek ZeidanNo ratings yet

- RV 2021 Tech Trends ReportDocument35 pagesRV 2021 Tech Trends ReportAyi CkNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 08 Feb 2021Document11 pagesAdobe Scan 08 Feb 2021Dakshita DubeyNo ratings yet

- TechnologyAsWayofRevealing STS13Document3 pagesTechnologyAsWayofRevealing STS13Josiel CaseresNo ratings yet

- RogerHopkinsBur 2019 20CulturalCriminology AnIntroductionToCrimiDocument26 pagesRogerHopkinsBur 2019 20CulturalCriminology AnIntroductionToCrimimarshaheijdenNo ratings yet

- Fashion Forecasting - 1Document8 pagesFashion Forecasting - 1Isha SharmaNo ratings yet

- Chemistry in Daily LifeDocument12 pagesChemistry in Daily LifeOBIJOENo ratings yet

- Jean Nouvel Doctrines and Uncertainties Questions For Contemporary Architecture Lectures at The CentreDocument13 pagesJean Nouvel Doctrines and Uncertainties Questions For Contemporary Architecture Lectures at The CentreRoberto da MattaNo ratings yet

- FST Essential November2021 ENDocument39 pagesFST Essential November2021 ENSaravanan K.No ratings yet

- CATHOLIC SOCIAL-WPS OfficeDocument3 pagesCATHOLIC SOCIAL-WPS OfficeDan Dan DanNo ratings yet

- Selling Wine Without BottlesDocument20 pagesSelling Wine Without BottlesKjellaNo ratings yet

- Biometry and Antibodies Modernizing Animationanimating Modernity Edwin CarelsDocument10 pagesBiometry and Antibodies Modernizing Animationanimating Modernity Edwin CarelsMatthew PostNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Course NotesDocument5 pagesChapter 1 Course NoteskrainajackaNo ratings yet

- On MicroperformativityDocument8 pagesOn MicroperformativitychakalsextapeNo ratings yet

- Towards Contemporariness of Local Architecture LesDocument9 pagesTowards Contemporariness of Local Architecture LesVaishnavi PatilNo ratings yet

- Dark FallDocument51 pagesDark FallAlok nrNo ratings yet

- Quiz On Myth Vs FolkloreDocument2 pagesQuiz On Myth Vs FolkloreEdwin CuajaoNo ratings yet

- Mini-Peta Health Ibanez Infographic PDFDocument5 pagesMini-Peta Health Ibanez Infographic PDFBanjo IbañezNo ratings yet

- Environments (Out) of Control: Notes On Architecture's Cybernetic EntanglementsDocument18 pagesEnvironments (Out) of Control: Notes On Architecture's Cybernetic EntanglementsLVNo ratings yet

- The of Public Problems: CultureDocument18 pagesThe of Public Problems: CultureSantiago AlzugarayNo ratings yet

- Classicus and Vernaculus - Leon KrierDocument7 pagesClassicus and Vernaculus - Leon KrierWilly FoxNo ratings yet

- pp12 174 6Document1 pagepp12 174 6api-311321957No ratings yet

- Ratti, C. - Network SpecifismDocument3 pagesRatti, C. - Network Specifismarq torresNo ratings yet

- Ancient LawDocument5 pagesAncient LawLudmila MachadoNo ratings yet

- Mimesis and The Death of Differences in Graphic ArtDocument13 pagesMimesis and The Death of Differences in Graphic ArtZiyuan TaoNo ratings yet

- Walter Pichler Author(s) : Diane Lewis Source: BOMB, No. 77 (Fall, 2001), Pp. 52-53 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 21/06/2014 18:19Document3 pagesWalter Pichler Author(s) : Diane Lewis Source: BOMB, No. 77 (Fall, 2001), Pp. 52-53 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 21/06/2014 18:19Roberto da MattaNo ratings yet

- 4 MayDocument1 page4 Mayapi-463413853No ratings yet

- Maryamilyas: Khaplu-CityDocument6 pagesMaryamilyas: Khaplu-CityMaryam IlyasNo ratings yet

- STS Mod 3Document2 pagesSTS Mod 3KARYLLE JELAINE DAVIDNo ratings yet

- Mimicry BhabhaDocument10 pagesMimicry BhabhaPanji HandokoNo ratings yet

- Philosophy in The Wild: Listening To Things' in Baltimore: Recipient of Action. Wondering at TrashDocument2 pagesPhilosophy in The Wild: Listening To Things' in Baltimore: Recipient of Action. Wondering at TrashaliNo ratings yet

- GPPC M2 Explore Fi AsDocument2 pagesGPPC M2 Explore Fi AsAudrey AngeliqueNo ratings yet

- Foundation of MoralityDocument7 pagesFoundation of MoralityDannie Vic TorresNo ratings yet

- Key Assumptions: of Roy A. Rappaport, As Well As A Special Issue ofDocument3 pagesKey Assumptions: of Roy A. Rappaport, As Well As A Special Issue ofriccilou molinaNo ratings yet

- Urban Pleasures and The Moral GoodDocument9 pagesUrban Pleasures and The Moral GoodDafne WyrmNo ratings yet

- Modernity Modernization: Civilization SolidarityDocument2 pagesModernity Modernization: Civilization SolidarityNguyen Thanh PhuongNo ratings yet

- Frontier: The Underground Is No Longer Simply TheDocument7 pagesFrontier: The Underground Is No Longer Simply Thedr_ardenNo ratings yet

- Mania, Aesthetics, and Musical MeaningDocument12 pagesMania, Aesthetics, and Musical MeaningaslıNo ratings yet

- Swarm TectonicsDocument18 pagesSwarm TectonicspisksNo ratings yet

- Prosthetic Theory Disciplining of Architecture - WigleyDocument25 pagesProsthetic Theory Disciplining of Architecture - WigleyJillian SproulNo ratings yet

- Recursion InterruptedDocument9 pagesRecursion InterruptedNila HernandezNo ratings yet

- Narrative Myth and Urban DesignDocument14 pagesNarrative Myth and Urban DesignAndrea ČekoNo ratings yet

- The Economics Book (DK) - 22-23Document2 pagesThe Economics Book (DK) - 22-23manolocolombiaNo ratings yet

- Wong Et Al 2023 On The Roles of Function and Selection in Evolving SystemsDocument11 pagesWong Et Al 2023 On The Roles of Function and Selection in Evolving Systemsfer137No ratings yet

- Magazine 12 2011 Future of PublishingDocument3 pagesMagazine 12 2011 Future of PublishingExtremixNo ratings yet

- AD ExuberanceDocument5 pagesAD ExuberanceCarlos CaminoNo ratings yet

- Oikos and Domus On Constructive Co Habitation With Other CreaturesDocument19 pagesOikos and Domus On Constructive Co Habitation With Other CreaturesMafalda CarvalhoNo ratings yet

- Oppression and Responsibility: A Wittgensteinian Approach to Social Practices and Moral TheoryFrom EverandOppression and Responsibility: A Wittgensteinian Approach to Social Practices and Moral TheoryRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- OASE 91 - 53 Orchestrating Architecture PDFDocument6 pagesOASE 91 - 53 Orchestrating Architecture PDFsergiocobosNo ratings yet

- OASE 91 - 93 Encoutering Atmospheres PDFDocument8 pagesOASE 91 - 93 Encoutering Atmospheres PDFsergiocobosNo ratings yet

- OASE 91 - 83 Form Formless PDFDocument10 pagesOASE 91 - 83 Form Formless PDFsergiocobosNo ratings yet

- VOGLER The House As A ProductDocument196 pagesVOGLER The House As A ProductsergiocobosNo ratings yet

- 8000series Tech Datasheet 2018Document3 pages8000series Tech Datasheet 2018lucky414No ratings yet

- Proline Table-Top Machines Z005 Up To Z100: Product InformationDocument2 pagesProline Table-Top Machines Z005 Up To Z100: Product InformationErika Mae EnticoNo ratings yet

- Mechanics of Solids - (Riveted and Welded Joints)Document37 pagesMechanics of Solids - (Riveted and Welded Joints)TusherNo ratings yet

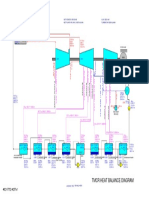

- 01 TMCR Heat Balance DiagramDocument1 page01 TMCR Heat Balance DiagramPrescila PalacioNo ratings yet

- Optoelectronics Circuit CollectionDocument18 pagesOptoelectronics Circuit CollectionSergiu CristianNo ratings yet

- Metal Roof Roll Forming MachineDocument6 pagesMetal Roof Roll Forming MachineDarío Fernando LemaNo ratings yet

- Compteur 7757 - A PDFDocument16 pagesCompteur 7757 - A PDFbromartNo ratings yet

- Roberto Del RosarioDocument19 pagesRoberto Del RosarioCarl llamasNo ratings yet

- Business, Government & Society: Pawan Kumar N K 12301005Document8 pagesBusiness, Government & Society: Pawan Kumar N K 12301005Pawan NkNo ratings yet

- Biomedical Uses and Applications of Inorganic Chemistry. An OverviewDocument4 pagesBiomedical Uses and Applications of Inorganic Chemistry. An OverviewHiram CruzNo ratings yet

- Jammer Final Report Mod PDFDocument41 pagesJammer Final Report Mod PDFNourhanGamalNo ratings yet

- Idioms & PhrasesDocument4 pagesIdioms & PhrasesHimadri Prosad RoyNo ratings yet

- GFB V2 - VNT Boost Controller: (Part # 3009)Document2 pagesGFB V2 - VNT Boost Controller: (Part # 3009)blumng100% (1)

- DSP Lab RecordDocument97 pagesDSP Lab RecordLikhita UttamNo ratings yet

- FAB-3021117-01-M01-ER-001 - Rev-0 SK-01 & 02Document91 pagesFAB-3021117-01-M01-ER-001 - Rev-0 SK-01 & 02juuzousama1No ratings yet

- 5754 Aluminum CircleDocument2 pages5754 Aluminum Circlewei huaNo ratings yet

- 2005 Removing Aland RegeneratingDocument6 pages2005 Removing Aland RegeneratingHebron DawitNo ratings yet

- The Mind of A MnemonistDocument4 pagesThe Mind of A MnemonistboobeeaaaNo ratings yet

- Car Frontal ImpactDocument25 pagesCar Frontal Impactapi-3762972100% (1)

- BCB NO1) Bearing CatalogDocument17 pagesBCB NO1) Bearing CatalogGabriela TorresNo ratings yet

- Soal DescriptiveDocument4 pagesSoal DescriptiveLuh SetiawatiNo ratings yet

- Hemiplegia Case 18.12.21Document5 pagesHemiplegia Case 18.12.21Beedhan KandelNo ratings yet

- Numerical WindingDocument12 pagesNumerical Windingsujal jhaNo ratings yet

- DS-7204HI-VS Net DVR - V2.0 (080909)Document88 pagesDS-7204HI-VS Net DVR - V2.0 (080909)ANTONIO PEREZNo ratings yet