Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Petronius, Philo and Stoic Rhetoric

Uploaded by

meregutuiCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Petronius, Philo and Stoic Rhetoric

Uploaded by

meregutuiCopyright:

Available Formats

Societe d’Etudes Latines de Bruxelles

Petronius, Philo and Stoic Rhetoric

Author(s): E. J. Barnes

Source: Latomus, T. 32, Fasc. 4 (OCTOBRE-DÉCEMBRE 1973), pp. 787-798

Published by: Societe d’Etudes Latines de Bruxelles

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41529524 .

Accessed: 18/06/2014 12:48

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Societe d’Etudes Latines de Bruxelles is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Latomus.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 62.122.76.45 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 12:49:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Petronius, Philo and Stoic Rhetoric

In 1932, A. D. Nock firstdrewattentionto a possible relationshipbet-

ween Sat. 1-2 and Philo. In a reviewof the Colson-Whittaker editionof

Philo's De Plantationehe wrote,"De plantatione156 occursin an excursus

whichbears unmistakeablesigns of havingbeen copied fromsome Greek

source of a more or less popular philosophicaltype ... Both [Philo and

Petronius]are using a commonplace,knownto us also fromPseudo-Lon-

ginus, Seneca Ep. 114, and Persius 1. This use of an earliersource", he

goes on, "explains whyPetroniusspeaks of the infectionof Athensby the

Asiaticstyle,a reproachhardlyto the pointafterthe timeof Augustus,for

theAsiaticstyleis hardlyheardof later.It shouldfurther be remarkedthat

Petronius is not wholly serious( 0. Rhetorical absurditiesand moral

theories of degenerationare equally a matterof amusementto him.

Agamemnon'sremark,sermonemhabes non publici saporis, and the un-

dignifiedendingof thescene,and the returnto thethemein 8*8(again with

a bad reception),indicatethat here,as in the tiradeon luxuryin 55, we

have a caricatureof the serious and philosophicpoint of view. Perhaps

Petroniushad Seneca in mind(2)'' With regardto this last suggestion,he

pointsout the use of adflaturin Ep. 114. 3 and PetroniusSat. 2. 7 (3).

The pertinent passage in Philo is foundin a contextconcerningopinions

on why wise men get drunk; there is regretfor the Good Old Days.

Longinus(44) cites "a recentphilosopher",who says thingsare not what

(1) Cf.G.Bagnani, ArbiterofElegance {Phoenix

suppl. vol.2 ; Toronto 1954)4,n.8 : "Asalutary

warningthatonemust nottake anystatement ofPetroniustooseriously hadbeenissued byA.D. Nock

etc".However,commentators still

ignore theprincipleinthiscontext : E. Cizek, Autourdela datedu

dePétrone

Satyricon inStudii clasice7 (1966)203; P. Veyne, Le 'je' dansleSatiricon inREL42

(1964)308,n.6 ; J.P.Sullivan, TheSatyricon ofPetronius: ALiterary Study (London 1968)171;

notso P. George, andCharacter

Style intheSatyricon inArion 5 (1966)351-356.

(2) CR46 (1932)173.

(3) Seneca: ingenium

... ilio(sc.animo hocquoque

) uitiato, adflatur. Petronius: nuperuentosa

istaec

etenormis ...ánimos

loquacitas iuuenum admagna surgentes ...adflauit. (Itshouldbenotedthat

at thebeginning ofhisletterSeneca hadalready written utaliquando inflataexplicatio

uigeret.)

's metaphor

Petronius ismore vividbecause ofhisuseofuentosa, which may byitself

betheexplanation

ofadflauit

, ratherthananyremembrance ofSeneca,though thelatter cannot bedenied Nock

outright

finishes

bycomparing Sat.55 with Epist.114.9 ; heapparently is referringtothepoemwhich

Trimalchioseems tobeaccrediting toPublilius Syrus.

This content downloaded from 62.122.76.45 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 12:49:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

788 E. J. BARNES

theywere.Seneca (114. 11) also offersan explanationforthecontemporary

degeneracyof eloquenceand morals.In his firstpoem, Persiuslamentsthe

death of a great language: over its grave he mocks(39-40) thatyou can

almost hear the violets growing.

I shall begin by illustratingNock's opinion througha word-for-word

comparisonof passages fromPhilo and Petronius; instructive parallelsfrom

Longinus,Seneca, and otherswill be includedin footnotesalong theway. It

will thenbe possible to evaluateNock's suggestionwithsome awarenessof

fact,and to attempta more definitiveanswer to what we may call "the

Philo question".

The readermay be astonishedto learn that it is possible to isolate no

fewerthan six themes by which the two authors develop theirsimilar

viewpoint.Each themewill firstbe named; thena parallelverticalpairing

of quotationswill be givenin illustration,

Philo on theleftand Petroniuson

the right.

Theme One : Currentdisregardfor the past, includingthe experienceand

methodof the older writers,who are regardedas "better" yet slighted(4).

... (bç ókíyovçeivai navxánaaivéxa- - Nam nisi dixerint

quae

тégoiç, ëçyoïç те xal Xóyoiç

, à g- adul esce ntul i probe nt, ut ait

Хаю xçónov ÇrjXáioecoí ê- 0cew so/j/„scolls re/inquentur (3.

Q&VT<iç(158). 2)(6)

("With the resultthatthereare very - Nunc ... quod turpiusest, quod

few indeed who eitherin deeds or quisque <puer> perperamdidicit,in

in writing,take delight in those senectuteconfitennon uult (4. 4).

things of which men of old were

fond") (5)

(4) PlatoLaws700-701 173c; G.M.A.Grube,

; cf.Theaetetus Plato'sThought (1935,repr. 1958)

200.CiceroDeOrat. 1. 12.52; ProCaelio17.40and41; Brutus 81.280.Longinus 44.l*ooavrr¡

Xáymv xoGfiixrjrtçèjié%ei ròvßiovòtpogía ("Aworld-wide ofutterance

sterility hascome upon

ourlife");44.2r¡Òrjjuoxgatia tôjvjLieyáÀow àyadr) Ttdrjvóç, fff*6vy ox&àòv xal awr¡xfiaaav

oi negtÀóyovç ôeivolxal owcméQavovC Democracy isa goodfoster-mother ofgreatness -.great

speakers when

flourished sheflourishedanddiedwith her"); onthedateofLonginus andhispossible

place inAugustan seeG.P.Goold,

letters AGreek ProfessorialCircleatRome inТАРА 92( 1961) 168-

178,189-192. SenecaControversiae 1 Prooem. 1; ibid.6 ; Hid.8 ; 10Prooem. 6 ; ibid.7. Seneca

Epist. 114.1; 10; 12(although Seneca'sEpist.97seems totake theopposite view tothatofthelast-

named passage:today is noworse thanyesterday). Persius 1. 61-62;69-71.

(5) CiceroTusc. Disp.5.47qualis autem homo ipseesset,talem eiusesseorationem; oration

i autem

facta similia,

factisuitam ("Asa manhimself is,so is hisstyleofspeech : moreover deedsresemble

speech, andliferesembles deeds").So SenecaEpist. 114.2 quemadmodum autem uniuscuiusque actio

dicentisimilis

est,sicgenus dicendialiquandoimitaturpúblicosmores ("Why, inthemanner hisactions

aresimilartohiswords inthecaseofevery human being,soatthepublic level tooattimes thestyle of

speech betraysthecharacter").

(6) Becauseoflackoffeethey would : cf.Sat.14.2quidfaciant

starve leges, ubisolapecunia regnati

("What may rulesavailwhere money aloneisqueen?") andPropertius 3. 7 ergo tucausa,

sollicitae

This content downloaded from 62.122.76.45 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 12:49:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PHILO,ANDSTOICRHETORIC

PETRONIUS, 789

Theme Two : Substitutionof new mannersthat can only be describedas

shallow noveltiesor fads, whose origin is simply the scramblingafter

newness,oddity,mutual indulgence,point(7).

... ttogdqriow olôova, jC xa- - ••• et rerum tumore et

X^Síaç áyayávreç xal хоф <pv- uanissitno Strepitìi(1. 2).

ri

otf/ta fiárov ¿яа/povreç - ... orationon est ...

(157).("They turgida (2.

debase language into a bloated 6).

misgrowth of disease to which they - ... uentosa istaec et enormis

give a seemingloftinessand gran- loquacitas ... ánimos iuuenum ...

deur by empty puffing and adflauit (2.7).

blowing".) - crudaadhuc studia inforumim-

pellunt (4. 2) (8).

ThemeThree: Throughthisnovelty,thefeedingof a lasciviouspassion for

; the vigourof mendeteriorated

extravagance intoeffeminatesimpering(9).

tdç éí яQáÇeiçènmvêoecaç xal <ntov-effecistis Ut corpus orationis

eneruaretur (2. 2). (Cf. uses of

ôijç ctfíaçxal avzáç (âç ínoç ebceïv)

âqqevaç ¿SedtfXvvav aia• neruUS in PetroniuS to mean

XQàç dvríxaX&v ¿çyaÇópevoi(158).membrum Uirile: 129. 8; 131.

("Deeds deservingpraise and en- [6; 134. 1.)

pecunia, uitaeM ... / tuuitiishominum crudeIia pabulapraebes; I ... I ancora teteneat,quem non

tenuere penatesi ("Soareyou, Cash,thereason fora harriedlife!Itisyou, through thevicesofmen,

whooffer them bitter sops.Cananyweight holdyoudown whom moral opinion cannotrestrain?").

Throughout theSatyricon penuryisdreaded bythepoor, andwealth criticizedbythewell-to-do. Here is

a socialfoible laughed at byPetroniusthrough caricature.

(7) ISOCRATES Against 2-8; Antidosis

theSophists 261; thepositive sideofthis negative

approach is

given inNicocles 5-9; Antidosis254; Panegyricus 8. PlatoLaws657; 660.CiceroBrutus 11.42;

Orator 9. 32. Demetrius OnStyle38; 245; 186(on affectation or"préciosité", xaxó£r¡Áov).

Longinus 44.3 ; 44. 11; alsovery pointedbutnotin44 are: "Writers slipinto puerility

through a

desire tobe unusual, elaborate,and,aboveall,pleasing. Theyrunaground ontawdriness andaf-

fectation" (3) and"Thedesire fornovelconceits,thechief maniaofourtime" (5); cf.alsoS. F. Bon-

ner,Roman Declamation intheLateRepublicandEarly Empire (Liverpool 1949)33ff. SenecaControv. 1

Prooem. 8 ; 10Prooem. 6. SenecaEpist.114.2 ; 10; 18; 21.Persius 1.38-40; 48-49.HoraceA.P.

416-418.

(8) Cf.Tacitus Dialogus 26negue enimoratorius immo

iste, hercule neuirilis quidem cultusest,quo

plerique temporum nostrorum actores

itautuntur,utlasciuiauerborum etleuitate sententiarumetlicentia

compositionis histrionalesmodos exprimant("Noristhis fellowanorator atheart, oreven a man for that

matter, whom attimes theperformersofourdaysousethat they produce a dramatist'sstylethrough

theirseductiveness ofdiction, their ofthought,

frivolity andtheir abandonment ofform").

(9) Isocrates Helen1-13 ; heconsidered anavoidance ofserious themes as a declaration

ofone's

ownweakness; in PlatoSymp. 177bthere is sucha dissertation on thetheme "Salt",while in

Aristotle Rhet. 2.24.2 wefind oneonthetheme "Mice". PlatoLaws 655.Pacuvius (inWar-

Niptra

mington Remains II, page266,number 269)lenitudo mollitudo

orationis, corporis("Agentleness of

speech anda softness ofbody" : Ulysses'

nursedescribing him?).CiceroDeOrat.. 1.54.231; Orator

This content downloaded from 62.122.76.45 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 12:49:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

790 E. J. BARNES

thusiasm and even, so to speak,

masculinethey have effeminized to

make shamefulby performing them

against what is noble")

ToiyaQovvел' exeivmv noir¡- - leuibus enim

atque inanibus

ral xal koyoygáyoi xal öooi лeoi rà рли;1) /f ... . ,

^ : еолоуоа^ор

*93 ¡Aovoixrjç

алЛа ; ,* f. * o sortis ludibria quaedam exci -

rjvOovv,

où ràç àxoàç ôià r f¡ç è v tando, effecistisut corpusetc. (2.

Qv 0 /ло ï ç <pO)vf¡ç âq>rjô v v o v- 2).

réç те xal в q v л t o vt e ç(I59). - omniaquasi eodem cibo

pasta

("In those times ... non potueruntusque ad senectutem

[they] did not weaken and unsex canescere (2. 8).

men's ears throughthe rhythmsof - piscator earn

imposuerit

language") hamis escam quam scierit

appetituros esse pisciculos(3. 4).

Theme Four : Metaphor: a disease of the body thatoughtto be surgically

treated( 10).

- Primi omnium eloquentiam

Tovçfjièv yàgÁóyovç vyiaívovr aç

xai êQQœpévovç elç ла- perdidistis ... effecistisut corpus

doç âvtfxeorov xai tpBogàv orationiseneruaretur et caderet

ледиууауогàvri a(pQiyéarjç (2 2)

xai âOÂriTixfíç óvtcoç e v - - grandis ,. .

et ... pudica orationon

,

e çř i a ç ovöev «

.je' on v -

/ut) vo a o v v

xaraaxeváoarreç xai r òv nX^Qt, est maculosa (pimply) ПвС

xal vaoróv ...tn" eêrovíaç turgida (obese, bloated), sed

ßyxov eiçnaqà q/vatv oi&oéarjç naturali pulchritudine exsurgit

Xa X££ta ç àyayóvreç xal x e vф (2. 6).

yvottiaxi póvov ênaÍQovreç,ô -„uper uentosa istaec et

ÒCevôeiavтпд ovvevovoric ôvvaueœç , ...

e normis loquacitas ... ánimos

19.65: Tuse. Disp.2. 1.3. Demetrius OnStyle 189oneffeminacy theextreme ofpréciosité, languid

andtrivial

"likethemen whointhelegend arechanged intowomen" ; also287.HoraceA.P.60-72,

butonly totransfer

Philo's towords

figure themselves

ascreationsoroffspring ofman : they willhave

their

natural anddemise.

maturity ButPhilo'sideaofdecay oftheartseems nottohaveoccurred to

Horaceatall.CiceroDe Inventione 1. 1. 1; De Orat.1.4. 14; 8. 30; 9. 38; 2. 8. 33; Orator 41.

142; Tacitus Dialogus40; Quintilian2. 16.Iff.Aristotlehadbelieved toothat(forensic) eloquence

was"theoffspringnurturedbywell-established

political

harmony". Longinus 44.6 ; 44.7 ; cf.alsoad-

ditional

references

innote 7,above.SenecaControv. 1Prooem. 1.Seneca Epist.114.2 ; 3 ; 8 ; 11; 25.

Persius 1. 32-35;36; 63-65;103-104.

(10) Aristotle Rhet.3. 7, useofthemedical term axoc,"remedies" ofthemeans whereby

ina work

exaggerations aretoberemoved. CiceroDe Opt.Gen.Oral3. 8 ; Brutus 9. 36; 13.51;

Orator23.76.Demetrius OnStyle likeAristotle,using medicalterminology todescribe faults ina

work.Longinus 44.2 ; 44.6 ; he-

hadalready setthis

upforusin3.4 : "Asinthebody, soinwriting,

hollowandartificial

swellingsarebadandsomehow turnintotheir

opposite, as,theysay,nothing isdrier

thandropsy". SenecaControv. 10Prooem. 6. SenecaEpist.114.1; ibid.3; 4; 7; 11.

This content downloaded from 62.122.76.45 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 12:49:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PHILO,ANDSTOICRHETORIC

PETRONIUS, 791

õrav pákiara nsQnadfj, iuuenum ... ueluti pestilenti

étfyvvт ai (157). (disease-portending)quodam sidere

("Language once healthyand virile adflauit (2. 7).

- а с ne carmen quidem sani

theyhave turnedto a disease ... a

vital and athletichabit has become coloris enituit (2. 8).

sick ... a fulland massivebody has - doctores... necesse habentcum

been made unnaturally swollen and insanientibus furere (3. 2) ("to

misgrownwith hollow puffing... act insane amid the bedlam of the

whenfullydistended,it burstsasun- parents").

der") (n). j.

i

Theme Five : Metaphor: art has become confectionary,or an in-

toxicant( I2).

' - nihil ... aut audiuntaut uident

¿q> tfpœvôè óipcLQTvrai xa i

o ir о л óv o i xaí Saoi xfjçèv ßa~ sed mellitos uerborum

<pixf¡xai ¡uvgeyHxfj ai negieç- globulos et omnia dicta factaque

zexvïr

yiaç, àel ri xaivòvXQfbfia rj axfj^a et sesamo

quasi papauere

f¡ àt/jiàvfj xvÀòvênireixtÇov-

Te ç г aï ç alodifjaeaiv, Ôncoç sparsa (1. 3).

xòvfiyefAÓva - qui interhaec nutriuntur, non

noQdrjoœoi vovv

(159). i magis sapere possunt (have no

(contrastedwith "the poets and more sense of taste) quam bene

chroniclers of a bygoneage" : cooks olere qui in culina habitant (2.

and confectioners of our own day ... 1).

- omniaquasi eodem cibo pasta

I (2. 8).

! - piscator earn imposuerithamis

j escam (3. 4).

(11) HoraceA.P. 412-413 quistudet

optatamcursu metam

contingere ...sudauit

etalsit("Whoever

strivestograspinhisracetheyearned-forgoalhassweatedandshivered") 10.1.4 uerum

; Quintilian

nos...quomodo ...athleta,

...dicimus

sitinstituendus ...quogenere

quiperdidicerit adcer-

exercitationis

tamina praeparandus ofthenature

sit.("Because wecallhim

ofhisteaching, anathlete,

becausehehas

learned bywhat type hehastobetrained

ofdrill for ; notonly

thefray") doboth comparethewriter

to

anathlete, butalsodo they developa metaphor aroundtheimage.

( 12) PlatoGórgias 46a: asa corollary

tohistheory ofthefour

(anditsillustration) true and

sciences

four corresponding :

counterfeits

physical culture - cosmetic ) forthebody

medicine - cookery )

law-making - sophistry ) forthesoul

correctivejustice - rhetoric )

therhetor

weseethat istothe asthecookistothephysician.

judge Agamemnonusesthis

notion

tocon-

coct

a rather

weakdefence : they

ofteachers havetopleasetheir orthey

students, wouldnotearn

a living.

3. 25. 100.SenecaEpist.114.4 ; ibid.22; 25.

CiceroDe Orat.

This content downloaded from 62.122.76.45 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 12:49:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

792 E. J. BARNES

besiege the senses so as to sack the - dent epulas et bella (5. 19)

mindO3). ("Tales of battles too shall feast

your ears").

Theme Six : Metaphor: degenerateart a militaryassault on the senses and

intellect( l4).

àeí Tl Haivòv

xeâpa x.zX ¿л ir st- - sicut fìcti adula tores cum

XiÇovTtç т ais aladeas- cenas diuitum captant ... nisi

,nsidi° * m"bus

(3. 3).

- sic

eloquentiae magister, nisi

tanquam piscator earn imposuerit

hamis escam quam scierit ap-

petiturosesse pisciculos, sine spe

praedae etc. (3. 4).

Afterthis extensivecompilationof similaritiesboth in idea and in dic-

tion, therecan be no doubt that Nock is accurate in his essentialpoint,

whichis thatPetroniusand Philo are drawingfromthesame tradition.How

could this have occurred?

It would hardlyseem probablethatPetroniusread Philo, thoughbecause

of the chance of personalcontactduringPhilo's embassyto Caligula the

remote possibilityof their actually having met cannot be ruled out

altogether(,5). On theotherhand,Seneca, thatinsomniacphilosopher,may

well have read Philo ; but Longinusmay have lived too earlyto have done

so(16) At any rate, it would seem that Petroniushas these ideas in mind

moreconcretelythanSeneca does, so thatI shouldsuggestoff-handthatin

this instanceSeneca is not the creditor.In fact,it is clear fromour foot-

notesalone thatthe elementsof our tropewerequite commonpossessions

under the early Empire. I agree with Nock that we have here at least a

(13) Philo's

entire onstyle

excursus isplacedinthemidstofanessay 14Off.,

neol/аевг/д inwhich

theviceofdrunkennessisdiscussed

fromnumerouspointsofview: weakness

ofthemind,andtherefore

ofitsproducts, from

is theconsideration which heentersintooratory.

(14) Longinus 44. 6. SenecaControv.10Prooem. 7.

(15) Orhemay have met anearly

Philoduring toSyria

trip ofBagnani,

(с/theconjectures Arbiter

57-58; theyear

would have been

39),when,asBagnani elsewhere (Phoenix

suggests 8[1954]80andn.

28),"hewillcertainly

have runafter

been oftheAlexandrian

bytheleaders Jews": cf.Josephus

Antig.

lud.18.8.

(16) СУsupra, note4, Goold.

This content downloaded from 62.122.76.45 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 12:49:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PHILO,ANDSTOICRHETORIC

PETRONIUS, 793

tradition; perhaps(ironyof ironies)it was even one of thecountlesscom-

monplace themes debated in the rhetoricalcurricula of the Roman

academies! Essentiallywe are dealing with the Those-Were-the-Good-

Old-Days Syndrome,promptedby some counter-revolutionary chemistry

withinthe blood of most of us.

But is the remainderof Nock's suggestionjustifiable?Philo's passage is

an obvious set-pieceand may well representcopying"from some Greek

source of a more or less popular philosophicaltype"; but I doubt that

Petroniusis copyingfromthe same source.There is no harmonyof order,

no glimpse of a lurkingstereotype,in the mannerby which these two

authors, under comparison,present the various themes. For example,

remarkhow variouslyscatteredthe quotationsare througheach passage

consulted.In fact,in the fifthcategorygiven above, the inebriationfigure

does not occur in Petronius.Either Longinus or Seneca would be more

likelythan would Petroniusto be using Philo's supposedsource,but their

treatment is just as individualas is Petronius's.I suggestthatthesewriters

"

followa commoncriticaltradition, but nota singleidentifiablesource",as

Nock believed.

*

* *

The questionwhich nextarises is this: fromwhat othersources,con-

cerningthemselvesas much with literarystyleas with philosophy,could

Philo and Petroniushave been drawing?Ratherthan extendthe limitsof

thisstudyexcessivelyin an attemptto be exhaustive,I shall brieflysketch

what to me is a reasonablesuccessionin the handing-downof our several

themes.

Isocrates was concerned with constructinga Rhetoric,not with its

dissolutionPD ; but it was for him a culturalstudyto providethe good

citizenwithpracticaland necessarytools. To him art forart's sake was an

imposture.Avoidanceof seriousand pertinentthemeswas a declarationof

weakness.Eloquence was a source of blessings.But even in his day, the

(17) Hebelieved that

only intreating

ofgreat

issues

wasgreatutterance : J.W.H.Atkins,

possible

Criticism

Literary inAntiquity

I (London1952)125.Sophistic

hadlostitself

ina mazeoftricksand

devices.

(Itisofinterest inPlato'sMeno

that, 90ff., thesonofa self-made

Anytus, man, infury

declares

thathenever hashadanything todowith : Trimalchio

a sophist wastosayalmostthesame and

thing,

boastabout it,onhistomb.Sat: 71. 12).Mechanical

methodsweredeemed tohaveaninfallible

ef-

ficacy;themes were (barren

trifling mythological

disputation,

pettylegalpleading).

This content downloaded from 62.122.76.45 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 12:49:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

794 E. J. BARNES

doctrinethatcivilizationis nourishedby eloquencewas a commonplace.We

can in his worksdiscern ideas consonantwith our themes2 and 3 (18).

Plato provides material,throughouthis works and not gatheredin one

place, thatwouldfitour themes1, 2, 3 and 5. He does not use thefigureof

disease in connectionwithliterature as he did formoralfaults,presumably

because he feltone could alwaysban undesirableartand banishundesirable

artists: one would notbotherto curethem( 19).Aristotlethroughout is con-

cernedwithobservingdistinctpieces of art,and carriesno briefforart in

the abstractor for possible infirmities. However,in Rhetoric3. 7 we do

meetthemedicalterm"remedies"used of themeanswherebyexaggerations

in a work are to be removed; this fits our theme 4(20).

Cicero is the firstwriterin whose worksat large we findregularuse of

the variousthemes(21). Demetriusin his treatiseOn Style gives us several

uses of themes2, 3 and 4 (the last, similarto the methodof Aristotle,

above) (22). Horace comes veryclose on a few occasions to theme3. He

assumes that the classical way is the way in which thingswill be done,

even if he does feel it necessaryto repeathis admonitionto the Pisones to

be a creditto theirfather(23). This omissionof Horace's is odd, because

Naevius had asked the question: Cedo : qui uestramrempublicamtantam

amisistis tarn cito? and had answered himself(among other things):

Proueniebantoratoresnoui, stulti adulescentuli(as reportedby Cicero De

Senectute6. 20). ElsewhereCicero had put it theotherway around,but the

componentswere the same ( Brutus 12. 45).

The elderSeneca employsthe firstfourthemesas well as number6, but

theyare workedskilfullyintoset-piecesforthe introduction to Book 1 and

Book 10 only(24). Longinus and the younger Seneca have been dealt with

in the footnotes.Persius,a contemporary of Petronius,uses only themes1,

2 and 3; this is perhaps importanti25).

It is clear, then,thatCicero may hold a clue to our dilemma.His use of

our variousthemes,whilegenerous,is scattered: he omitsto organizethem

into a comprehensivescheme as had Philo and Petronius.But there is

anotherconnectionbetweenCicero and Philo, and it is a man we have not

notes

(18) C/1supra, 7 and9

227-228

(19) Sophist : onekind ofevilinthesoul(wickedness

; theother iscompared

isignorance)

with

diseaseinthebody:itmust becured orcutout,i.e.,punished. 4, 7, 9, 12.

notes

Cf.supra,

notes

(20) Cf.supra, 9 and10.

notes

(21) Cf.supra, 4, 7, 9, 10,12.

notes

(22) Cf supra, 7, 9, 10.

notes

(23) Cf.supra, 7, 9, 11.

4, 7, 9, 10,14.

notes

(24) Cf.supra,

4, 7, 9.

notes

(25) Cf.supra,

This content downloaded from 62.122.76.45 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 12:49:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PHILO,ANDSTOICRHETORIC

PETRONIUS, 795

yetmentioned.Cicero,along withotheryoungRomansof good family,had

studiedin Rhodes with the philosopherPosidonius,who died a veryold

man in 51 B.C. (26). Their trainingmust have been largelyrhetoricaland

academic: notjust whatto talkabout butalso how; forPosidoniuswas in-

terestedenoughin styleto writeneçi Xétjeœçsiaay<oyr¡ (Diogenes Laertius

7. 60), was a supporterof the principleof nçénov (the Xé£iç oixsía г ф

nqáyfiaxi),and believedthat rhetoricwas a servantto philosophy,that it

had a moralvalue. Posidoniuswas an eclecticscholar,forhe blendedStoic,

Platonic,and Aristotelian doctrines.But he was also quite conversant(even

involved)withthe rhetoricalideals sharedby the Scipionic circle; during

his youthin Athenshe studiedunderPanaetius,theStoic (Cicero De Off 3.

7-8) along withScipio and Laelius,who tookback to Rome (to suchfriends

as Lucilius) the ideals theyhad absorbed.It is reasonableto assume that

mensuch as Cicero learnedearlythe device of applyingmoralideas to the

studyof rhetoric.Certainlyin Cicero's case thestudyof theuses of rhetoric

was a centralconsideration, as it would have been in certainof Posidonius's

texts(not only neqi XéÇeœç,I should imagine,but even his booksneqi

xadrjxovroçand neqi àqerœv). It is not farfetchedto suppose that

Posidonius was responsible,to greateror lesser degree,for drillinghis

pupilsat timesin theapplicationof all thethemeswe have isolatedforthis

study.But theiruse would,to Romans,have been as rhetoricalcolores; to

Rhodians as well, no doubt.

Now Philo too, thoughlivinga coupleof generationsafterCicero,yetin-

volvedas he was in the learningof his time,was largelyinfluencedin his

methodby Posidonius.What Posidoniushad taught,or at least written,at

Rhodeswould be knownto Philo at Alexandria.It has been suggested,for

example,that Posidoniuswas a seminal influencein the compositionof

Tusc. Disp. 1 and in the moral attitudesof Galen (27), and Cicero's own

workson philosophyand rhetoricshow repeatedglimpsesof thegreatstoic.

"

It is inconceivablethat the scholar Philo, indisputably"indebted to

Posidoniusas a philosophicalmentor(28), shouldhave remainedignorantof

Posidonius'sneqi XéÇecoçor uninfluenced by it. Any rhetoricaluse in his

(26)ThearticleonPosidonius inRE22'(1953)coll.558-826, givesdepth towhat wearetoldby

Cicerohimselfinhisessays: Tusc.Disp.2. 61; Nat.deorum1.6 ; 2. 88(hedescribes Posidonius

as

familiaris

noster;Posidonius

livedwithCicero duringhisvisit

toRome lateinlife)

; De Diu.1.6 {cf.

esp.Columns 567,570,575,772,773; alsoref. toanarticle

inCQ43[1949] 82ff.); a complete

listing

ofPosidoniuss knownwritingsisalsoprovided,with oftheir

descriptions natureasfaras itispossible

totell.

AddCiceroOrator 25,wherein hementions that

theRhodian school ofrhetoric never

approved

therichandunctuous styleoftheAsianschools.

(27) RE (supra,

n. 26) 575.

(28) OCD684(Treves).

This content downloaded from 62.122.76.45 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 12:49:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

796 E. J. BARNES

textsPosidoniushad made of our variousthemeswould have been familiar

to Philo ; therefore

it is suitablethatPhilo uses themin a rhetoricalcontext

insidea muchlargerfabricthatis purelymoral in purpose.It is as though

he paused to digressintoa familiarschool-boydeclamatiothatseemedper-

tinentin a peripheralway. Is it not fittingto revertto youthfulthoughts

whendiscussingthe Good Old Days? Things weredifferent when I was a

boy ...

What has all this to do with Petronius?I feel certainthat,if the syn-

drome of six themes which we have discoveredto be common to the

youngerSeneca, Philo, Longinus,and Petroniushad been in currentuse as

one comprehensiveidea in Cicero's day, then surely,somewherein all

Cicero's writingson spoken prose, he would have foundthe figuresuseful

to develop in our now-familiar pattern; yetwe findthat,in reality,he has

scatteredthem almost at random over the corpus of his treatises.Fur-

thermoreit is clear to thiswriterthat,in Cicero, thesethemesare less fully

realizedthaneven in theelderSeneca, who also did not use themas one in-

ter-complementary familyof themes.It would seem inescapableto conclude

that,since the themesare common individuallyto all these writers,then

probably,givenimpetusby theexampleof Posidonius,theywereamongthe

tools of discussionemployedin therhetoricalschools of thefirstcentury(if

not, in fact,of Cicero's day, as I could also believe). Yet once we get past

the elderSeneca, all the themessuddenlyappear in the writingsof several

"

authorsas a complete matched- set" of criticalimplements.And at the

same instantthereappears Persius,a Stoic, a contemporary of the younger

Seneca and of Petronius,certainlya well-readand eagercriticof thewriters

of his day, who has resistedpushingthe manifestations of our six-partsyn-

drometo the limit.The reason could surelybe thattherewas in his time

(sc. in Petronius'sand Philo's time)no one canonicalsourcefromwhichit

could be derived.Persiustook themesas he chose them,like everyoneelse,

and recognizedno debt to a "popular philosophicalsource". The themes

were treatedsynopticallyat this time by membersof Nero's coterie: but

Persius kept outside this group, as his mockeryof Nero shows.

The farther we go, the less we seem to have to do withsome philosophic

handbookor singlesource,forit would be an incrediblecoincidenceto find

all thesewritersso indebtedto anyone whose workis not available to us.

Yet we have also seen that thereis no apparentinter-dependencebetween

thefourauthorsmentionedby Nock : to all appearanceseach is developing

his selectionof the six themesin his own personalmannerexceptforwhat

maybe sharingof the conceitswithinNero's court-circle. The factthatan

involvedcontemporary like Persiusand an influentialpredecessorlike the

elder Seneca (not to mentionCicero) handle the themesin an even less

This content downloaded from 62.122.76.45 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 12:49:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PHILO,ANDSTOICRHETORIC

PETRONIUS, 797

organizedmanneris to be kept in mind. I put forwardthe opinion that

Philo,Seneca, Longinus,and Petronius,and Persiusand theotherstoo, are

drawingupon a broadlybased repertoire of generalcommonplacesthathad

been part of the arsenal of academic debate frombeforeeven the timeof

Plato,and whichby theearlyEmpirehad come to formtheautomaticcon-

textof any argumenthavingto do withthe past vs. thepresent,fluctuation

in moralcustoms,evils of education,Demon Rum,and Progress,The Most

ImportantProduct.

Quid ad nos ? CertainlyifPetroniushad come in contactwiththesecriti-

cal notionsin theeast at an earlierstage in his career,he could conceivably

have done so by means of sources available as well to Philo. However,

thereseems no reason to see him as an antiquaryin this fashion.The

notionswere currentrightin Rome throughouthis life; and the way in

whichtheyare presentedby otherwitnessessuggeststhattheywerepartof

theundercurrent of criticalthought.This suggests,morethananythingelse,

the academiesof rhetoric.We mustnot jump to the conclusionthathe is

parodyingSeneca, forwe have seen thatPetronius'smethodof handlingthe

themesis unique and connectshim withnone of the otherwriterswho use

the same themes.Likewise we have no righton this account to see in

Agamemnona caricatureof Seneca or of anyoneelse. Agamemnonis sim-

plybehavingin character.He is a rhetorsayingwhatrhetorsusuallysaid ;

Encolpius is a productof the rhetoricalsystem,sayingwhat it had taught

him to say. The internaldramaticmotiveis the reasonwhy Petroniushas

introducedinto his workat this pointa criticalsyndromeevidentin other

writersas well; but his use of the themeshas been entirelyartistic,not

critical; dramatic,not parodie.

The internaldramaticmotiveis, of course, to amuse the reader.Our

point of departurehere must be Nock's statementthat Petroniusis not

whollyserious.Commonsense and theaestheticsof prosecompositionUrge

the beliefthathe will have approvedof muchthatEncolpius says. On the

otherside it must be admittedhe would probablyagree with much in

Agamemnon'sarguments.He is outlininga typicaldeclamatio, paintingthe

characteristic colours vividlyenough that the species can be recognized

easily; but the implicationfollowsthat he kepthis own impartiality. The

transparent rhetorical tricks used by both debaters, and the effectof ab-

surditythat results,indicatethat Petroniusdoes not involvehimselfas a

partisanon one side or the other.Consequentlyit is irrelevant to ask, with

whomdoes Petroniusagree? We can, however,suggestthathe holds up to

ridicule the methods of scholastics who (1) would use the same old

argumentsto condemneducationwithoutapplyingremedies,or (2) would,

in an attemptto cure the creature,apply the same remediesthatkilledit.

This content downloaded from 62.122.76.45 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 12:49:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

798 E. J. BARNES

Petroniusstaysout of theargumentpresumablybecause he recognizedthat

it had neverbroughtabout the reformsnecessary; and besides he is not

writinga treatiseof reform.He encouragesus to laugh at those persons

fromwhom reformshould be expectedto originatebut who insteadhave

remainedblindto thereal problems.BothAgamemnonand Encolpiuscause

us amusementas they reenact an absurd contemporaryphenomenon.

Petroniuswas probablycontentto let the matterrest there.

E. J. Barnes

This content downloaded from 62.122.76.45 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 12:49:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Arthur Leslie Wheeler - Erotic Teaching in Roman Elegy and The Greek Sources. Part IIDocument23 pagesArthur Leslie Wheeler - Erotic Teaching in Roman Elegy and The Greek Sources. Part IImeregutuiNo ratings yet

- Encolpius Critiques Rhetorical Declamation at Roman SchoolDocument9 pagesEncolpius Critiques Rhetorical Declamation at Roman SchoolmeregutuiNo ratings yet

- Latin DeclensionsDocument1 pageLatin DeclensionsMarcelo AugustoNo ratings yet

- Horace, Person and PoetDocument10 pagesHorace, Person and PoetmeregutuiNo ratings yet

- Fay, Edwin W - Greek and Latin Word StudiesDocument19 pagesFay, Edwin W - Greek and Latin Word StudiesmeregutuiNo ratings yet

- W.H. Stevenson - A Poem Ascribed To AugustusDocument3 pagesW.H. Stevenson - A Poem Ascribed To AugustusmeregutuiNo ratings yet

- Air-Imprints or EidolaDocument14 pagesAir-Imprints or EidolameregutuiNo ratings yet

- Muraki, Masatake - Discourse PresuppositionDocument23 pagesMuraki, Masatake - Discourse PresuppositionmeregutuiNo ratings yet

- The Fates, The Gods, and The Freedom of Man's Will in The AeneidDocument17 pagesThe Fates, The Gods, and The Freedom of Man's Will in The AeneidmeregutuiNo ratings yet

- Proclus, Brian Duvick - On Plato's Cratylus - Cornell University Press (2007)Document88 pagesProclus, Brian Duvick - On Plato's Cratylus - Cornell University Press (2007)TheaethetusNo ratings yet

- John Grier Hibben - The Relation of Ethics To JurisprudenceDocument29 pagesJohn Grier Hibben - The Relation of Ethics To JurisprudencemeregutuiNo ratings yet

- Alfred W. Benn - The Ethical Value of HellenismDocument29 pagesAlfred W. Benn - The Ethical Value of HellenismmeregutuiNo ratings yet

- Bonaventura's Romantic AgonyDocument31 pagesBonaventura's Romantic AgonymeregutuiNo ratings yet

- V. M. Pashkova - Hannah Arendt Phenomenology of Thinking and ThoughtlessnessDocument3 pagesV. M. Pashkova - Hannah Arendt Phenomenology of Thinking and ThoughtlessnessmeregutuiNo ratings yet

- Hans-Georg Gadamer - Plato As PortraitistDocument30 pagesHans-Georg Gadamer - Plato As PortraitistmeregutuiNo ratings yet

- Meister Eckhart - Sermon 57Document3 pagesMeister Eckhart - Sermon 57meregutuiNo ratings yet

- Earl Taylor - Lebenswelt and Lebensformen - Husserl and Wittgenstein On The Goal and Method of PhilosophyDocument17 pagesEarl Taylor - Lebenswelt and Lebensformen - Husserl and Wittgenstein On The Goal and Method of PhilosophymeregutuiNo ratings yet

- Ellen Darwin - The Religious Training of Children by AgnosticsDocument12 pagesEllen Darwin - The Religious Training of Children by AgnosticsmeregutuiNo ratings yet

- John Grier Hibben - The Relation of Ethics To JurisprudenceDocument29 pagesJohn Grier Hibben - The Relation of Ethics To JurisprudencemeregutuiNo ratings yet

- Hastings Rashdall - The Ethics of ForgivenessDocument15 pagesHastings Rashdall - The Ethics of ForgivenessmeregutuiNo ratings yet

- Alfred Fouillee - The Hegemony of Science and PhilosophyDocument29 pagesAlfred Fouillee - The Hegemony of Science and PhilosophymeregutuiNo ratings yet

- Henry Sturt - DutyDocument13 pagesHenry Sturt - DutymeregutuiNo ratings yet

- Josiah Royce - The Knowledge of Good and EvilDocument34 pagesJosiah Royce - The Knowledge of Good and EvilmeregutuiNo ratings yet

- J. S. Mackenzie - Self-Assertion and Self-DenialDocument24 pagesJ. S. Mackenzie - Self-Assertion and Self-DenialmeregutuiNo ratings yet

- H. Rashdall - The Limits of CasuistryDocument23 pagesH. Rashdall - The Limits of CasuistrymeregutuiNo ratings yet

- Bernard Bosanquet - Xenophon's Memorabilia of SocratesDocument13 pagesBernard Bosanquet - Xenophon's Memorabilia of SocratesmeregutuiNo ratings yet

- J. S. Mackenzie - Reply To Some CriticismsDocument6 pagesJ. S. Mackenzie - Reply To Some CriticismsmeregutuiNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Filipinos and Their Revolution: Events, Discourse, and HistoriographyDocument5 pagesFilipinos and Their Revolution: Events, Discourse, and HistoriographyCendy GammadNo ratings yet

- Understanding the Enemy in Postcolonial Georgian LiteratureDocument26 pagesUnderstanding the Enemy in Postcolonial Georgian LiteratureNino Didberuashvili100% (1)

- How Bonsai Poem Scales Down LoveDocument3 pagesHow Bonsai Poem Scales Down LoveLariza GallegoNo ratings yet

- Harry Potter and The Half-Blood Prince Battle of The Astronomy TowerDocument2 pagesHarry Potter and The Half-Blood Prince Battle of The Astronomy TowersinemaNo ratings yet

- About Carlos BulosanDocument4 pagesAbout Carlos BulosanReymark Albuera AnglitaNo ratings yet

- Oscar Wilde Style AnalysisDocument16 pagesOscar Wilde Style AnalysisCracker Jack429No ratings yet

- 8th Grade ELA The Story of Prometheus and Pandora S Box 1Document7 pages8th Grade ELA The Story of Prometheus and Pandora S Box 16800486No ratings yet

- Sacred Hope Poems of Agostinho Neto CompressDocument128 pagesSacred Hope Poems of Agostinho Neto CompressAlternative Archivist100% (1)

- English Poem Comprehension Friday 5th JuneDocument5 pagesEnglish Poem Comprehension Friday 5th JuneYo NmNo ratings yet

- The Killers by Ernest HemingwayDocument6 pagesThe Killers by Ernest HemingwayMalikNo ratings yet

- Ib English HL CourseworkDocument4 pagesIb English HL Courseworkfhtjmdifg100% (2)

- Writing and Deconstruction of Classical TalesDocument4 pagesWriting and Deconstruction of Classical TalesEcho MartinezNo ratings yet

- White Slaves, African Masters: Paul BaeplerDocument22 pagesWhite Slaves, African Masters: Paul Baeplerjoãoandre arturNo ratings yet

- Rapunzel - Audiobook - Text - The Fable CottageDocument13 pagesRapunzel - Audiobook - Text - The Fable CottageФрея КантіNo ratings yet

- NickDocument3 pagesNickimsarah.hadi100% (1)

- Shar (F) GoluboyDocument4 pagesShar (F) GoluboyAlfred KalteneckerNo ratings yet

- An Unexpected Visitor - SophiaDocument2 pagesAn Unexpected Visitor - SophiaSophia CheongNo ratings yet

- 06 - Chapter 1Document35 pages06 - Chapter 1Vedansh Shrivastava100% (1)

- Angelov - The-moral-pieces-by-Theodoros-II - Laskaris PDFDocument34 pagesAngelov - The-moral-pieces-by-Theodoros-II - Laskaris PDFOrsolyaHegyiNo ratings yet

- Watching "100 Tula Para kay StellaDocument4 pagesWatching "100 Tula Para kay StellaLyka Mendoza GuicoNo ratings yet

- 21 STDocument18 pages21 STgilmardhensuarezNo ratings yet

- 1 Memgr-3-Simple-Future-Truly-Madly-Deeply-Savage-Garden PDFDocument2 pages1 Memgr-3-Simple-Future-Truly-Madly-Deeply-Savage-Garden PDFKety Rosa MendozaNo ratings yet

- Alasna Quranic Homeschool: Level 2: Circle The The Letter AlifDocument10 pagesAlasna Quranic Homeschool: Level 2: Circle The The Letter AlifAnas RafieeNo ratings yet

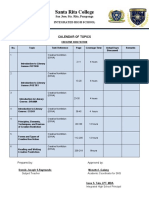

- Santa Rita College: San Jose, Sta. Rita, Pampanga Integrated High SchoolDocument2 pagesSanta Rita College: San Jose, Sta. Rita, Pampanga Integrated High SchoolricoliwanagNo ratings yet

- Medieval England 1066-1485Document21 pagesMedieval England 1066-1485Zarah Joyce SegoviaNo ratings yet

- Nov15TakeHomeSheet DavidandMephibosheth 1Document3 pagesNov15TakeHomeSheet DavidandMephibosheth 1CotedivoireFreedomNo ratings yet

- C1 File Test 3Document4 pagesC1 File Test 3Brenda Agostina BertoldiNo ratings yet

- (Éé'Âö É (Éöºiéeò-ºéúséò, +méºiéDocument4 pages(Éé'Âö É (Éöºiéeò-ºéúséò, +méºiéVijayKumar LokanadamNo ratings yet

- Literature Review SynonymDocument5 pagesLiterature Review Synonymc5ha8c7g100% (1)

- Franz Kafka's A Hunger Artist: Analysis of Plot, Characters, ThemesDocument21 pagesFranz Kafka's A Hunger Artist: Analysis of Plot, Characters, ThemessaimaNo ratings yet