Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bescobar - Progress in History 20-22

Uploaded by

Andres Rey0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views3 pagesSin descripción

Original Title

bescobar_Progress in History 20-22

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentSin descripción

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views3 pagesBescobar - Progress in History 20-22

Uploaded by

Andres ReySin descripción

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

rogress in History·

(Fronl the tirst lecture to King

Ma.xi111ilian

. l[ of Bavaria, ''On the

Epo~hs of Moden1 History'', 1854)

I. How tlu~com.-ept '"progress.. is to be understood in history

t r ,w ,, ere w nssumc, in comnHHl with nrnny u philosopher, Lhat ali of rnankind is

d~vdnping frc,m a giwn original stntc ll' a positivc goal. we could conceive lhis

phx:css in twl, wuys. Eithcr u general guiding will promotes the development of

the hunrnn rnce frnm urn.· point to another or therc is in mank.ind a vestige of

spirituul nutun.: whic.'h or nt·t·essity drives things toward a certain goal. I would not

,:l,llsidcr thl'SC two views 10 be either philosophically tenable or historically

dcmonstrahh.:.

\Ve cunnot consider these views philosophically acceptable because the former

cuse u.oes so far as to do uway with human freedom and makes men into too\s

witho~t a will of their own; and because in the lauer case men would have to be

God or nothing at ali.

But histori..:n.lly too. these views are not provable. For first of ali. the greater

pan of mankind is still in its original state. at the very point of departure . And then

the question arises: what is progress? Where is the progress of mankind noticeable')

Elt::ments of the greal historical development have been incorporated in the Latin

nnLI Gl'mrnnic pcoples. Hen!, to be sure. a spirilual power exists which develops

st~p by step. lndecd, the hislorical power of the human spirit in ali of history is

unmistaknhle. a movement started in primeva] times which continues with a

ccrtain s1eadjness. TI1ere is. however, but one system of populations arnong

mankind which cakes part in this general historical movernent. while others ure

excludcd from i1. But in general we can also view the nat.ionalities engaged in the

historical movemenr as not progressing steadily. For instance, if we turn our

utLent1o n to Asio, we see that culture originated there and that the continent had

sl!vem l cultuml epoch.s. But there the movement has on the whole t,eeo

n-lrogre~si, e: for lhe oldest epoch of Asian culture was the rnost flourishing: tlte

second and third epochs , in which lhe Greek and Rornan elernents dominated.

were no longer as signi ficant, and with the invasion of the barbarians - rhe

• F'rom ··ut>er dte Eí>OChen der neueren G , hi h .. . ,., p 1-9.

tmn~lated by \\'ilma A. lggers. ese e le m Weltgesc/Jiclire, Theil IX. Abt -· P ·

Thc Jdealistic Theon of 1-Jisroringrapliy 21

g,,ls - culture in Asia disappe~ d complelely. In view of this fot·t the thcs1!>

~~t:;.. _,graph.K progn!ssion has been offered. l must. howevcr, from thc ~taii

,)! ~~..~ 11 nn

J~ 1 .... ~

empty ussernon lo nss ume. as did for instance Peter the Grcat that

· · th d f h ·

., lturt' was makrng e_roun s O t e globe: that It had come from the East' and

,u curning thcre agarn.

"as ~ . be .

secondly. another error 15 _10 avoid~d herc, namely, the assurnption that the

rNzre.ssive de,·elopment of the centunes encompasses at the same lime ali

~;cheS of hun~an nature an~ skill. To stress only one example, history shows us

81:

ch:tl in modero tunes flounshed most in the fifteenth and in the first half of the

SLxteenth century. ?ul m. the seventeenth and in the first three quarters of the

ei!lbtt:.enth cenmry it declmed the most. The same is true of poetry: there are also

0 ;1 vbrief periods when this art is really outstanding, but there is no evidence that

it ri·ses to a higher level in the course of the centuries.

If we thus exclude a geographic law of developmem and if we furtherrnore have

10 assume, as history teaches us, that peoples can perish arnong whom the

development that has begun <loes not steadily encompass everything, we shall bener

recognize the real substance of the continuous movement of mankind. It is based on

lhe fact that the great spiritual tendencies which govern mankind sometimes go

separate ways and at other times are closely related. In these tendencies there is,

bowever, always a certain particular direction which predominates and causes the

omers to recede. So, for exarnple, in the second half of the sixteenth century the

religious element predominated so much that the literary receded in the face of it. In

tbe eighteenth century, on the other hand, the striving for utility gained so much

ground that art and related activities had to yield before it.

Thus, in every epoch of mankind a certain great tendency manifests itself; and

progress rests on the fact that a certain movement of the human spirit reveals itself

in every epoch, which stresses sometimes the one and sometimes the other

tendency, manifesting itself there in a characteristic fashion.

If in contradiction to the view expressed here, however, one were to assume

that this progress consisted in the fact that the life of mankind reaches a higher

potential in every epoch - that is, that every generation surpasses the previous one

completely and that therefore the last epoch is always the preferred, the epocbs

preceding it being only stepping stones to ones that follow - this would be an

injustice on the part of the deity. Such a generation which, as it were, had become

a means would not have any significance for and in itself. It would only have

rneaning as a stepping stone for the following generation and would not bave an

immediate relation to the divine. But I assert: every epoch is immediate to God,

and its wortb is not at ali based on what derives from it but rests in its own

ex.istence, in its own self. In this way the contemplation of history, that is to say

of individual life in history, acquires its own particular attraction, since now every

epoch must be seen as somelhing valid in itself and appears highly worthy of

consideration.

The historian thus has to pay particular attention first of all to how people in.a

certain period thougbt and lived. Toen he will find that, apart from ce~n

unchangeable eternal main ideas, for instance those of morality, every epoch has lls

. ,,... - 4 iW ~ !'..!". R J :t o

11w11 pm l k t1l11r lé nd rnLY 1111d ltn nw11

id, ul IJ11t 11ltl11,11¡,l1 ,·v•JI"~ r t).4 " • 1J 1H, ') 11

1w,t1l ll: 11lh 10 111111 llt.1 w111 l h 111 1111d hy ll~ d l.

c,11 0 ,¡1111 11111·11 nut , ,vn look wlH.it , &t f 11

h11 tli h11111 11 , 'l'lw h1•, ltt1 11111 11111•,I 1tin d1.1t1 t ~

', n,T otully , 1)(· r1 r1 v1· 11,,·~ dil l ••H.. 11, '

,1:1 w u o n 1he 111111 vld1111 I cpt1d 111, 111 1111 h:1

te, 11 l 'll!I ve 1111; 1111w1 11n ,~;i,,I, y , ,1 1 '

lsl'q lll' I\CL' ' (

)lit ' ¡; 111111111 111 ¡1111 rl'l ' 111111 ¡/A' n

n : 11JI111 pt11a11·M 114"11). u 111 1 w, ,u Id 11 <, VI'$) ( 1

lo s11y 1hul lltl,; pw gte •,u 11111vc<> In u Mll'Ul~h 1 h}

l 11111.l , hui 1111,rl' llk c u 11vi;1 whi<t lll 1t'

• 1

ow n wn y dotc rn1111c " 1t •11.: nU l'MC, lf 111111y d111c 1

111 nw kc 1111 11 11; 11 ml' k, 1 p1 c,1t111: 11t.,• ( 1l lt.1

- ti lll1.: 1.• n,1 tl111l· He :. 1,of11rc 11 "

11•1 i.u1 v1•y111 g 11II ol 111~11111~ 111

:ink ind i11 1111 1ou,1,,

In ~ 11url'. 1111111c 11,1n ij Lru c rn 1,~.y •IU1d

1

. tn>J ,t cv c, yw hcr c ol cqu n 1 vn 1uc . ,1·1,i:n.: m, 1

11\l

\ 1 '

•

1 1 1

ln i lho t·1.hu; nl ion ol de~

11111nkiml. hui t.ct'orc ( lod ull Kc ncr

1111C ,1111 11I inc n up pca r cnd,,w .

w11h 1)qu ul ri ght s , und thi Mis ho w 1hc h1-.11>1 iun

mu ,;t v1c w 11tult.cfll . c,J

ln'-11ftu· os wc c un lol low lw,' 111ry, um:omlitiu11u,l prol KrC 'i'i, 11 nu ,,,tt dc f in11 c upw,tlUI

t

movc111c11l, 1!, 10 he uss u1m:d 1n tlu.: rcul111 ol 0111 o

11.:n u int crc~.1!1 m w 11c h rclro.o,r-·""\•. >n ) j(

wi ll hw·t.lly he posi.lhlc unh:ss thc ro oi.:c,un ,

un 11nmi:n1,c up hcu vul. In rcgard 111

moruli~y. h1.1wcvcr, prngrc -.s cun no l he truc~J . Mo

rul uJca1, .cu~1, LO be i,urc, prllgrt ~•,

cx tcn s,v cly ; und :,u om: cun uls o us~crl 1n.

cu ltu ral (,<e t.ff/ J<f ') 111u1tcr•, lh;it' f,,,

cx mn plc , thc grc111 w11rks wh ich _11rt uod lltc

,m tur c hu vc p~oduc c<l un.: cnjoycd

tot.lay by lar gc r nu mb crs 1hun prov1ou:..ly. Bu

t 11 wo uld he nd 1cu lou '> lo Wllnt UJ ~.

n grc ntc r wr itc r of cpi cs thun Hon1cr or u grc utc

r wr itc r of trugcdic:.. tha n So phl)(.l t:.

You might also like

- Sissel Tolaas Ocean SmellscapeDocument1 pageSissel Tolaas Ocean Smellscapez4cwym4sdjNo ratings yet

- 1877 - Three Worlds and The Harvest of This World (Portada)Document198 pages1877 - Three Worlds and The Harvest of This World (Portada)aleferrizNo ratings yet

- Ebook The Three WorldsDocument197 pagesEbook The Three WorldsAl Fool Cohen100% (1)

- The Rosicrucian Society Quarterly RecordDocument14 pagesThe Rosicrucian Society Quarterly Recordfabi o santannaNo ratings yet

- Gonda Hymns Not Employed Ritual PDFDocument140 pagesGonda Hymns Not Employed Ritual PDFSaurabh100% (1)

- Friendship's Ethic: Exploring the Meaning and Significance of Non-Heterosexual FriendshipsDocument26 pagesFriendship's Ethic: Exploring the Meaning and Significance of Non-Heterosexual FriendshipsMarcelo CamargoNo ratings yet

- Storr Our GrotesqueDocument21 pagesStorr Our GrotesqueAndreia MiguelNo ratings yet

- Watchtower: 1941 Convention Report - St. Louis, MissouriDocument75 pagesWatchtower: 1941 Convention Report - St. Louis, MissourisirjsslutNo ratings yet

- LigzgkDocument10 pagesLigzgkHardik JindalNo ratings yet

- Life's Borderland and BeyondDocument311 pagesLife's Borderland and BeyondNicholas ShumateNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 PDFDocument24 pagesChapter 10 PDFSalmanNo ratings yet

- January 2021 (Last Imed Rotation)Document13 pagesJanuary 2021 (Last Imed Rotation)Kekelwa Mutumwenu SnrNo ratings yet

- History NoteDocument22 pagesHistory NoteAdityaNo ratings yet

- N Ead S. E: MNND MDocument1 pageN Ead S. E: MNND MSritama KhanraNo ratings yet

- Economic Institutions and Development: A Global PerspectiveDocument9 pagesEconomic Institutions and Development: A Global PerspectivePragyan NibeditaNo ratings yet

- Second World War-1Document4 pagesSecond World War-1KEVIN BINOYNo ratings yet

- Mapping Equipotential LinesDocument4 pagesMapping Equipotential LinesMartin MuleiNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 01-Aug-2021Document2 pagesAdobe Scan 01-Aug-2021Prahallad SunaNo ratings yet

- Philippe Descola-The Making of ImagesDocument10 pagesPhilippe Descola-The Making of ImagesCara TomlinsonNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 12 Oct 2023Document5 pagesAdobe Scan 12 Oct 2023Alina SaraswatNo ratings yet

- DEBARAY, Regis. A Modest ContributionDocument20 pagesDEBARAY, Regis. A Modest ContributionVictor BtzaNo ratings yet

- Causes, Effects and Control Measures: TypesDocument19 pagesCauses, Effects and Control Measures: TypesAyush ChoudhuryNo ratings yet

- Present Truth by J. Wendell, 1873Document18 pagesPresent Truth by J. Wendell, 1873sirjsslutNo ratings yet

- Balochistan Sea Fisheries (Amendment) Act 1986Document3 pagesBalochistan Sea Fisheries (Amendment) Act 1986Rabia MustafaNo ratings yet

- God's covenant promises conditional blessingsDocument1 pageGod's covenant promises conditional blessingsCyrille MBOUDOUNo ratings yet

- Ped CHP 05 YogaDocument19 pagesPed CHP 05 YogaPriti UpadhyayNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan Jul 07, 2023Document9 pagesAdobe Scan Jul 07, 2023MartinNo ratings yet

- Politics and The Other Scene: Etienne 13alibarDocument15 pagesPolitics and The Other Scene: Etienne 13alibargerman pallaresNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 05 Mar 2022Document4 pagesAdobe Scan 05 Mar 2022Farhaniqbalahme dNo ratings yet

- The Bhagavad Gita: An Introduction to Hindu ThoughtDocument17 pagesThe Bhagavad Gita: An Introduction to Hindu Thoughtsyminkov8016No ratings yet

- Adobe Scan Sep 27, 2023Document2 pagesAdobe Scan Sep 27, 2023Léxí MwáléNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan Jan 02, 2021Document9 pagesAdobe Scan Jan 02, 2021graddleNo ratings yet

- Romanic Review - Examining Heretical ThoughtDocument282 pagesRomanic Review - Examining Heretical ThoughtsespinoaNo ratings yet

- Deanna Petherbridge: Primacy of DrawingDocument516 pagesDeanna Petherbridge: Primacy of DrawingGabriel CoelhoNo ratings yet

- Atharva Veda Samhita I PDFDocument634 pagesAtharva Veda Samhita I PDFiNo ratings yet

- RegulationsDocument25 pagesRegulationsTyploshion TKNo ratings yet

- Can't Fear Your Own World IiiDocument289 pagesCan't Fear Your Own World IiiFabián León100% (3)

- .I C C r:1 S, e R I S S S o e S H E: Wanl MiseDocument1 page.I C C r:1 S, e R I S S S o e S H E: Wanl MiseSritama KhanraNo ratings yet

- Fifth of JulyDocument59 pagesFifth of JulyVíctor Gamboa0% (1)

- Workbook Units 9 & 10Document13 pagesWorkbook Units 9 & 10csi553006No ratings yet

- Kant Socio PDFDocument3 pagesKant Socio PDFYashvi BhartiNo ratings yet

- The origins of history as a scientific discipline: classical historicismDocument8 pagesThe origins of history as a scientific discipline: classical historicismAntonela30No ratings yet

- Models of Instruction TableDocument3 pagesModels of Instruction Tableapi-316153308No ratings yet

- Levy PDFDocument61 pagesLevy PDFAvery MinionNo ratings yet

- Chem Papaer PDFDocument2 pagesChem Papaer PDFpruthvi rajNo ratings yet

- Mark Meaney, Capital As Organic Unity PDFDocument100 pagesMark Meaney, Capital As Organic Unity PDFGriffin BurNo ratings yet

- Godman To TycoonDocument246 pagesGodman To TycoonRamdev100% (4)

- Adobe Scan 11-Jan-2023Document8 pagesAdobe Scan 11-Jan-2023divyanshi guptaNo ratings yet

- Jaspers & Falkner 2013Document16 pagesJaspers & Falkner 2013JYJB WangNo ratings yet

- Cano of Judo Text PDFDocument249 pagesCano of Judo Text PDFDemetrius Thomas Nosb100% (1)

- Student Work FeedbackDocument12 pagesStudent Work Feedbackapi-364224560No ratings yet

- Macn-R000130701a - Affidavit of Allodial Record of Live BearthDocument1 pageMacn-R000130701a - Affidavit of Allodial Record of Live Bearththeodore moses antoine beyNo ratings yet

- Drawing PampletDocument4 pagesDrawing PampletPranav BharakhadaNo ratings yet

- Nurrnte,: The ./ TT - Sts. Hills Anti Throuj.!IiDocument3 pagesNurrnte,: The ./ TT - Sts. Hills Anti Throuj.!IiElizabeth MsNo ratings yet

- Scan Jan 11, 2020Document1 pageScan Jan 11, 2020Michael Francis DanzilNo ratings yet

- Ge 1Document4 pagesGe 1Reymond GuevarraNo ratings yet

- A Mission To Gelele - King of Dahome PDFDocument418 pagesA Mission To Gelele - King of Dahome PDFduduNo ratings yet

- Courtcase For Cleansing Your Generational Bloodline 2019 PDFDocument5 pagesCourtcase For Cleansing Your Generational Bloodline 2019 PDFEduan Narib100% (2)

- SCP Gecc101Document132 pagesSCP Gecc101Kristine Razo100% (1)

- Major architectural styles that shaped IndonesiaDocument5 pagesMajor architectural styles that shaped IndonesiaFigo Catur PalusaNo ratings yet

- The - Rebel - OshoDocument544 pagesThe - Rebel - Oshoveronicat100% (2)

- Studies in Hadith Composition Literature PDFDocument575 pagesStudies in Hadith Composition Literature PDFBajunaid MalacoNo ratings yet

- From Middle Eastern Literature and Its Times: The Epic of GilgameshDocument11 pagesFrom Middle Eastern Literature and Its Times: The Epic of GilgameshIJNo ratings yet

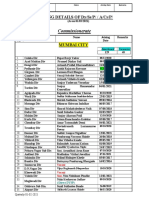

- Commissionerate: Posting Details of Dy/Ss/P/ / A/Cs/PDocument55 pagesCommissionerate: Posting Details of Dy/Ss/P/ / A/Cs/PSandipRanvirNo ratings yet

- Mythology and Folklore (Reading Materials)Document12 pagesMythology and Folklore (Reading Materials)George Kevin TomasNo ratings yet

- Development of States in EuropeDocument2 pagesDevelopment of States in EuropeRommel Roy RomanillosNo ratings yet

- Araling Panlipunan: Quarter 3 - Module 1 Paglakas NG EuropeDocument23 pagesAraling Panlipunan: Quarter 3 - Module 1 Paglakas NG EuropeMuhammad PandanNo ratings yet

- A Short Hindu Wedding CeremonyDocument4 pagesA Short Hindu Wedding CeremonyCH'NG KIA CHUANNo ratings yet

- Can Parsis Celebrate ChristmasDocument3 pagesCan Parsis Celebrate ChristmasBurjor DabooNo ratings yet

- Is There A Judeo - Christian Tradition PDFDocument296 pagesIs There A Judeo - Christian Tradition PDFBreno BenjaminNo ratings yet

- Mahabharata Adi Parva - by Hridayananda GoswamiDocument366 pagesMahabharata Adi Parva - by Hridayananda Goswamishaurya108100% (3)

- The Hail, Holy Queen:: Additional PrayersDocument5 pagesThe Hail, Holy Queen:: Additional PrayersLea Foy-os CapiliNo ratings yet

- Religious and Non-Religious FestivalsDocument7 pagesReligious and Non-Religious FestivalsivonneNo ratings yet

- Rizal Noli Me TangereDocument35 pagesRizal Noli Me TangereKristine Cantilero100% (2)

- GSW AssignmentDocument8 pagesGSW AssignmentMinenhle KumaloNo ratings yet

- Gods Love FinalDocument25 pagesGods Love FinalJustine CerialesNo ratings yet

- An Interview With David Myatt, Summer 2022Document8 pagesAn Interview With David Myatt, Summer 2022ThormyndNo ratings yet

- Divine Personality and Personification: KernosDocument11 pagesDivine Personality and Personification: KernosAnant IssarNo ratings yet

- Bibliografija CompletaDocument34 pagesBibliografija CompletaFr Jesmond MicallefNo ratings yet

- Generational Perspective Ministering To Builders Boomers Busters and BridgesDocument5 pagesGenerational Perspective Ministering To Builders Boomers Busters and BridgesAbegail ReyesNo ratings yet

- List of Names from Timestamped DocumentDocument10 pagesList of Names from Timestamped DocumentArim ff8No ratings yet

- Who Is JesusDocument36 pagesWho Is JesusMercyJatindro100% (1)

- (Eleni Sideri, Lydia Efthymia Roupakia (Eds.) ) Rel (B-Ok - Xyz) PDFDocument210 pages(Eleni Sideri, Lydia Efthymia Roupakia (Eds.) ) Rel (B-Ok - Xyz) PDFOceanNo ratings yet

- The Family Is A Social Setting Where The Child First Experiences LoveDocument3 pagesThe Family Is A Social Setting Where The Child First Experiences LoveDe Vera, Jenny Vhe F.No ratings yet

- Cba Scheme of WorkDocument5 pagesCba Scheme of Workapi-543391912No ratings yet

- Electronics 09 00177 PDFDocument34 pagesElectronics 09 00177 PDFDiana AnghelacheNo ratings yet

- The Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsFrom EverandThe Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (8)

- The Three Waves of Volunteers & The New EarthFrom EverandThe Three Waves of Volunteers & The New EarthRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (179)

- Summary: How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen By David Brooks: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen By David Brooks: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Stoicism: How to Use Stoic Philosophy to Find Inner Peace and HappinessFrom EverandStoicism: How to Use Stoic Philosophy to Find Inner Peace and HappinessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (84)

- The Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismFrom EverandThe Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Summary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (30)

- Stoicism The Art of Happiness: How the Stoic Philosophy Works, Living a Good Life, Finding Calm and Managing Your Emotions in a Turbulent World. New VersionFrom EverandStoicism The Art of Happiness: How the Stoic Philosophy Works, Living a Good Life, Finding Calm and Managing Your Emotions in a Turbulent World. New VersionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (51)

- 12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosFrom Everand12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (207)

- The Secret Teachings Of All Ages: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC OUTLINE OF MASONIC, HERMETIC, QABBALISTIC AND ROSICRUCIAN SYMBOLICAL PHILOSOPHYFrom EverandThe Secret Teachings Of All Ages: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC OUTLINE OF MASONIC, HERMETIC, QABBALISTIC AND ROSICRUCIAN SYMBOLICAL PHILOSOPHYRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- How to Destroy America in Three Easy StepsFrom EverandHow to Destroy America in Three Easy StepsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (21)

- Summary of Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor E. FranklFrom EverandSummary of Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor E. FranklRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (101)

- The Authoritarian Moment: How the Left Weaponized America's Institutions Against DissentFrom EverandThe Authoritarian Moment: How the Left Weaponized America's Institutions Against DissentRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- How to Be Perfect: The Correct Answer to Every Moral QuestionFrom EverandHow to Be Perfect: The Correct Answer to Every Moral QuestionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (194)

- The Courage to Be Happy: Discover the Power of Positive Psychology and Choose Happiness Every DayFrom EverandThe Courage to Be Happy: Discover the Power of Positive Psychology and Choose Happiness Every DayRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (215)

- Meditations, On the Shortness of Life, The Enchiridion of Epictetus: The Ultimate Stoicism CollectionFrom EverandMeditations, On the Shortness of Life, The Enchiridion of Epictetus: The Ultimate Stoicism CollectionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (15)

- There Is a God: How the World's Most Notorious Atheist Changed His MindFrom EverandThere Is a God: How the World's Most Notorious Atheist Changed His MindRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (71)

- The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass MovementsFrom EverandThe True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass MovementsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- How States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyFrom EverandHow States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (7)

- The Courage to Be Disliked: How to Free Yourself, Change Your Life, and Achieve Real HappinessFrom EverandThe Courage to Be Disliked: How to Free Yourself, Change Your Life, and Achieve Real HappinessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1595)

- Jungian Archetypes, Audio CourseFrom EverandJungian Archetypes, Audio CourseRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (124)