Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Branski2002 PDF

Uploaded by

lakjdlkaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Branski2002 PDF

Uploaded by

lakjdlkaCopyright:

Available Formats

The Laryngoscope

Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc., Philadelphia

© 2002 The American Laryngological,

Rhinological and Otological Society, Inc.

The Reliability of the Assessment of

Endoscopic Laryngeal Findings Associated

With Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Disease

Ryan C. Branski, MA; Neil Bhattacharyya, MD; Jo Shapiro, MD

Objective: To determine the reliability of the as- highly subjective. Key Words: Gastroesophageal re-

sessment of laryngoscopic findings potentially associ- flux disease, chronic laryngitis, reliability.

ated with laryngopharyngeal reflux disease (LPRD). Laryngoscope, 112:1019 –1024, 2002

Study Design: Prospective randomized blinded study.

Methods: One hundred twenty video segments of rigid INTRODUCTION

fiberoptic laryngeal examinations were prospectively The deleterious effects of gastric material on the lar-

analyzed by five otolaryngologists blinded to patient ynx have been well documented. Early research by

information and were scored according to several Delahunty and Cherry1 found that inflammation, ulcer-

variables potentially associated with LPRD. Separate ation, and the formation of granulation tissue on the vocal

assessments of the degree of erythema and degree of

fold mucosa followed extended exposure to gastric mate-

edema were scored on a five-point scale for the ante-

rial. More recent research has suggested that patients

rior commissure, membranous vocal fold, and inter-

with chronic reflux present with increased interarytenoid

arytenoid region. Similarly, interarytenoid pachyder-

mia, likelihood of LPRD involvement, and severity of or posterior glottic inflammation or erythema (or a com-

LPRD findings were assessed. For each of these bination of these), hypertrophy of the posterior commis-

scored physical findings, inter-rater and intrarater sure (cobblestoning), and granulation tissue formation in

reliabilities were determined. Results: The inter-rater severe cases.2 Koufman et al.3 recently suggested that

reliabilities of the laryngoscopic findings associated laryngeal edema (not erythema) is the most common la-

with LPRD were poor. Intraclass correlation coeffi- ryngeal finding associated with reflux. However, there are

cients were 0.161 and 0.461 for edema of the aryte- relatively few studies correlating abnormal pH monitoring

noids and membranous vocal folds, respectively (P with laryngeal signs of reflux, and the overall sensitivity

<.001). Intraclass correlation coefficients were 0.181 and specificity of various findings corresponding to LPRD

and 0.369 for erythema of the arytenoids and membra- have not yet been determined.

nous vocal folds, respectively (P <.001). Raters dem- Double-barrel pH monitoring is currently considered

onstrated poor agreement as to the severity of LPRD by many authorities to be the gold standard for the diag-

findings (intraclass correlation coefficient, 0.265) and nosis and quantification of supraesophageal reflux.4 How-

the likelihood of an LPRD component for dysphonia ever, pH monitoring has not realized widespread use in

(intraclass correlation coefficient, 0.248). Similarly, the everyday clinical diagnosis and management of laryn-

intrarater reliability was extremely variable for the gopharyngeal reflux disease (LPRD). Several practical is-

various physical findings, with Kendall correlation sues limit the use of pH monitoring outside the research

coefficients ranging from ⴚ0.121 to 0.837. Conclu- realm.5 Many patients resist undergoing pH monitoring

sions: Accurate clinical assessment of laryngeal in-

because of the inconvenience and discomfort associated

volvement with LPRD is likely to be difficult because

with probe placement. In addition, insurance coverage for

laryngeal physical findings cannot be reliably deter-

the evaluation may be problematic. Sasaki and Toohill6

mined from clinician to clinician. Such variability

makes the precise laryngoscopic diagnosis of LPRD reported a general consensus among otolaryngologists

that when appropriate symptoms and laryngoscopic find-

ings are present, patients may be placed on a trial of acid

suppression therapy as both a diagnostic and a therapeu-

From the Division of Otolaryngology (R.C.B., N.B., J.S.), Brigham and

Women’s Hospital, and the Department of Otology and Laryngology (N.B., tic maneuver. Therefore, visual examination of the larynx

J.S.), Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.A. and pharynx are crucial to the initial diagnosis and sub-

Editor’s Note: This Manuscript was accepted for publication Febru- sequent treatment of patients with dysphonia or other

ary 13, 2002.

complaints consistent with LPRD.

Send Correspondence to Neil Bhattacharyya, MD, Division of Oto-

laryngology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 333 Longwood Avenue, Bos- Among studies proposing the possible and probable

ton, MA 02115, U.S.A. E-mail: neiloy@massmed.org laryngeal manifestations of reflux, there appears to be

Laryngoscope 112: June 2002 Branski et al.: Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Disease

1019

vast discrepancy in the visual criteria used by clinicians to be viewed twice by each rater to determine intrarater reliability.

diagnose LPRD.2 Even if accurate, consistent laryngeal All five of the raters viewed and rated the 120 video segments

findings that correlate with LPRD were identified, vari- separately under identical conditions without information about

ability among clinicians in terms of what constitutes these the diagnosis, demographic information, or treatment history of

individual patients. Their responses were kept confidential.

abnormal findings might exist. For example, one clini-

For each video segment, the raters were asked to rate the

cian’s “erythema” may be another’s “pallor.” The current presence of laryngeal features potentially associated with reflux,

study was designed to determine the level of general as described previously in the literature, using a five-point scale

agreement or disagreement among otolaryngologists with (Fig. 1). We asked raters to include visual findings consistent

respect to the presence of and degree of severity of laryn- with hyperemia or hypervascularity as part of the erythema

goscopic findings thought to be clinically consistent with score. In addition, they were asked to rate the overall severity of

LPRD. Unless consistency in the identification and quan- gastroesophageal reflux (GER) findings, the likelihood that GER

tification of visual laryngeal findings can be demon- was a component in the patients’ complaints of dysphonia, and

strated, an accurate diagnosis of LPRD based primarily on whether or not they would prescribe antireflux medication based

laryngoscopic findings is likely to be fraught with variabil- solely on the video laryngoscopic examination. The raters were

kept blind to medical history of individual patients, including the

ity from clinician to clinician and therefore from study to

presence of any reflux-related symptoms. The raters were aware

study. that each patient was being evaluated for voice-related

complaints.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Data Analysis

Patients

The evaluation data were imported into SPSS version 10.0

The study population consisted of 100 consecutive patients

software (Chicago, IL) for subsequent statistical analysis. Stan-

presenting to the voice division of an urban academic otolaryn-

dard demographic and descriptive summary data were computed

gology practice with a primary complaint of dysphonia during a

for each otolaryngologist-rater. Inter-rater reliability was deter-

6-month period. Each of these patients (68 female and 32 male

mined using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) as de-

patients) underwent transoral rigid endoscopy and stroboscopy

scribed by Shrout and Fleiss7 for a two-way random effects model.

with digital video recording as a component of their complete

This model assesses absolute agreement among several raters for

vocal function evaluation. Patients were asked whether they ex-

scale data. The threshold for statistical significance was set at P

perienced any classic symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux dis-

⬍.05. Intrarater reliability was determined for each rater based

ease (GERD), such has heartburn or excessive belching, as well as

on the interpretations of the 20 repeated patient recordings.

symptoms of extraesophageal reflux, such as halitosis, a burning

Kendall bivariate correlation coefficients were computed for each

sensation in the back of the throat, or excessive throat clearing. In

rater for each of the measured variables to assess intrarater

addition, current use of antireflux medications including both

reliability.

prescription and over-the-counter medicines was noted. Of the

100 patients, 38 reported at least occasional reflux-related symp-

toms. Of those 38 patients, 18 were currently taking antireflux RESULTS

medications (most commonly, omeprazole or lansoprazole). Of the Each rater evaluated each videostroboscopic record-

remaining 62 patients who denied any reflux symptoms, 13 were ing for a total of 600 scored patient evaluations (5 ⫻ 120).

currently taking prescription antireflux medication. One patients Means and standard deviations for each of the rated vari-

who denied having any reflux symptoms had recently undergone ables for each otolaryngologist across all patients are pre-

a Nissen fundoplication. Of the 100 patients, 47 presented with sented in Table I. Overall, 185 video studies (30.8%) were

lesions of the vocal folds, 24 were diagnosed with functional voice

disorders, 11 presented with a neurological source of dysphonia, 8

presented with a diagnosis of acute laryngitis, 7 had lesions of

either the false vocal fold(s) or subglottis, and 3 presented with

vocal fold atrophy. We chose to include patients with identifiable

lesions (e.g., vocal fold granulomas) because reflux may coexist

with or exacerbate these conditions.

Endoscopic views were collected using the Digital Strobos-

copy System (model 9200, Kay Elemetrics, Lincoln Park, NJ). A

rigid 70° endoscope (model SFT-I, Nagashima, Tokyo, Japan) was

coupled to a Stryker three-chip camera (model 782, Stryker, San

Jose, CA). Five-second segments of complete or near-complete

visualizations of the larynx from the anterior commissure to the

posterior pharyngeal wall were selected and edited using the Kay

Digital Stroboscopy Editor software package (Kay Elemetrics).

Raters

Five board-certified otolaryngologists with diverse clinical

interests served as raters. All of the rating otolaryngologists see

patients with dysphonia as part of their routine clinical practice.

The raters were full-time academic faculty members of Harvard

Medical School, Boston, and their time after residency ranged

from 3 to 19 years (mean period, 9.2 y). One hundred video

laryngoscopy segments were placed in random order and com-

bined with 20 video segments, which were randomly selected to Fig. 1. Laryngeal appearance rating form.

Laryngoscope 112: June 2002 Branski et al.: Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Disease

1020

TABLE I.

Summary of Individual Rater Data for Each Measured Descriptive Variable.

Rater 1 Rater 2 Rater 3 Rater 4 Rater 5

Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD

Edema

Anterior 0.2 0.6 1.2 0.9 0.7 0.7 0.7 0.7 0.4 0.9

Membranous folds 1.0 0.9 1.4 1.0 1.4 0.6 1.5 1.0 0.8 1.0

Arytenoids 1.1 1.0 0.2 0.5 1.9 0.7 1.9 0.9 0.7 1.0

Erythema

Anterior 0.2 0.6 1.3 1.0 1.1 0.6 0.9 0.7 0.3 0.9

Membranous folds 0.6 0.8 1.3 1.0 1.4 0.7 1.0 0.8 0.4 0.9

Arytenoids 1.1 1.0 0.2 0.6 1.9 0.7 1.8 0.9 0.8 1.0

Pachydermia 1.3 1.0 0.5 0.8 1.6 0.7 1.1 0.8 0.6 0.9

Severity of GER 1.2 1.0 0.5 0.8 1.8 0.7 1.7 0.8 0.7 1.0

Likelihood GER component 1.4 1.2 0.5 0.8 1.7 0.7 1.6 0.8 0.6 1.0

*All scores may range from 1–5.

SD ⫽ standard deviation; GER ⫽ gastroesophageal reflux.

interpreted as “normal,” with no evidence for GER find- GER was contributing to the dysphonia. According to es-

ings. The distribution of normal versus abnormal findings tablished criteria, all coefficients for single-measure reli-

for the aggregate 600 evaluations according to each ana- ability were poor, except for edema of the musculomem-

tomical subsite are displayed in Table II. branous folds, which exhibited only fair reliability.8

Inter-rater Reliability Intrarater Reliability

The single-measure and average-measure intraclass The intrarater reliabilities for each variable as mea-

correlation coefficients for measured variables are dis- sured by the Kendall bivariate correlation coefficient are

played in Table III, along with respective statistical sig- presented in Table IV. Only one of the raters (Rater 2) was

nificances. Both the single-measure and average-measure able to demonstrate consistent intrarater reliability for

intraclass correlation coefficients were found to be statis- multiple scale variables, with fair to excellent reliability

tically significant, but the overall magnitude of the coeffi- coefficients. However, even when the coefficients of reli-

cient (and therefore measured reliability) was poor. The ability reached statistical significance, the overall magni-

single-measure intraclass correlation coefficient corre- tudes of the correlations for the various raters was weak.

sponded to the inter-rater reliability from otolaryngologist Again, edema of the musculomembranous vocal folds ex-

to otolaryngologist for any given rated variable. The hibited the greatest intrarater reliability across each of

average-measure intraclass correlation indicates the pre- the raters. Comparisons were conducted for each rater to

cision that could be obtained by using multiple raters, as determine whether the rater was consistent in recom-

in the present study, and then determining an average mending GER treatment. Table V presents mean GER

score for each variable. The coefficients obtained indicate severity ratings for each rater based on patient groups for

that, when averaging the rating among several otolaryn- which the rater would recommend and would not recom-

gologists, reliability increases significantly. With respect mend GER treatment. Each rater was able to consistently

to both edema and erythema of the glottis, raters were segregate patients into treatment groups based on sever-

most likely to agree on the degree of involvement of the ity of GER findings.

musculomembranous vocal folds and least likely to agree

on the degree of arytenoid abnormality. Relatively poor DISCUSSION

agreement was noted for the degree of pachydermia, the In the late 1960s, Delahunty and Cherry1 described

overall severity of GER findings, and the likelihood that patterns of injury to the larynx caused by gastric material.

TABLE II.

Distribution of Normal and Abnormal Scores for Anatomic Subsites (n ⫽ 600).

Edema Erythema

Score AC MMF ARY AC MMF ARY Pachydermia

0 (Normal) 255 142 219 231 235 208 168

1–4 (Abnormal) 210 445 361 229 353 367 342

Unscored 135 13 20 140 12 25 90

AC ⫽ anterior commissure; MMF ⫽ musculo-membranous folds; ARY ⫽ arytenoids.

Laryngoscope 112: June 2002 Branski et al.: Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Disease

1021

TABLE III.

Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC) for Reliability of Examination Findings Between Raters.

Single measure Average measure

r P r P

Edema

Anterior 0.363 ⬍.001 0.740 ⬍.001

Membranous folds 0.461 ⬍.001 0.810 ⬍.001

Arytenoids 0.161 ⬍.001 0.490 ⬍.001

Erythema

Anterior 0.293 ⬍.001 0.675 ⬍.001

Membranous folds 0.369 ⬍.001 0.745 ⬍.001

Arytenoids 0.181 ⬍.001 0.525 ⬍.001

Pachydermia 0.351 ⬍.001 0.730 ⬍.001

Severity of GERD 0.265 ⬍.001 0.644 ⬍.001

Likelihood GERD component 0.248 ⬍.001 0.623 ⬍.001

*Interpretation of ICC: ⬍0.40 ⫽ poor; 0.40 – 0.59 ⫽ fair; 0.60 – 0.74 ⫽ good; ⬎0.74 ⫽ excellent.

GERD ⫽ gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Since that time, awareness of the potential impact of nience and, to some degree, its unavailability have pre-

LPRD on the larynx has steadily increased. Chronic vented it from becoming widely used as a diagnostic mo-

hoarseness, globus pharyngeus, and muscle tension dys- dality in chronic laryngitis. More often, otolaryngologists

phonia have long been purportedly associated with base the diagnosis of LPRD on the patient’s dysphonic

LPRD.9 Recently, evidence for a relationship between manifestations and associated reflux symptomatology, as

LPRD and mass lesions of the larynx including glottic well as the office-based laryngeal examination. However,

carcinoma has emerged.10,11 Given the prevalence of la- because classic symptoms of GERD are absent in 57% to

ryngeal complaints among patients seeking otolaryngo- 80% of patients with significant clinical manifestations of

logic care, LPRD is often entertained as the potential LPRD, otolaryngologists often rely heavily on their endo-

underlying diagnosis for many of these symptoms. Al- scopic assessment of the larynx in determining the pres-

though double-lumen pH monitoring is considered the ence of LPRD.2

gold standard for the diagnosis of both esophageal and Reflux-related injury to the larynx has also been

laryngeal reflux disease, cost factors, patient inconve- termed acid laryngitis, acid posterior laryngitis, peptic

TABLE IV.

Intrarater Reliabilities for Laryngoscopic Physical Findings Associated With GER.

Rater 1 Rater 2 Rater 3 Rater 4 Rater 5

Coefficient Significance Coefficient Significance Coefficient Significance Coefficient Significance Coefficient Significance

Edema

Anterior 0.594 0.010 0.702 0.001 0.000 1.000 0.445 0.054 0.509 0.051

Membranous 0.669 0.001 0.507 0.016 0.336 0.139 0.575 0.005 0.617 0.002

folds

Arytenoids 0.413 0.037 0.813 0.000 0.350 0.112 0.661 0.001 0.594 0.006

Erythema

Anterior ⫺0.121 0.608 0.834 0.000 0.047 0.870 0.289 0.196 0.681 0.011

Membranous 0.584 0.005 0.778 0.000 0.256 0.247 0.451 0.029 0.750 0.001

folds

Arytenoids 0.304 0.125 0.837 0.000 0.331 0.193 0.586 0.004 0.553 0.008

Pachydermia 0.401 0.049 0.678 0.002 0.494 0.038 0.540 0.012 0.265 0.241

Severity of 0.342 0.085 0.778 0.000 0.589 0.011 0.504 0.015 0.979 0.000

GERD

Likelihood GERD 0.275 0.156 0.778 0.000 0.364 0.112 0.552 0.008 0.846 0.000

component

Recommend 0.492 0.032 0.793 0.001 0.329 0.175 0.390 0.089 0.192 0.402

GER treatment

*P values ⬍.05 are marked as bold italic.

†Coefficients represent Kendall’s bivariate correlation coefficient.

GER ⫽ gastroesophageal reflux; GERD ⫽ gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Laryngoscope 112: June 2002 Branski et al.: Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Disease

1022

TABLE V.

impact that GER has on patients’ symptoms given a set of

Mean Severity Scores for GER Findings According to Intent physical findings.

to Treat. We were somewhat surprised that the otolaryngolo-

Recommend No GER

gists were unable to demonstrate good intrarater reliabil-

Treatment Group Treatment Group P value ity (Table IV). It is apparent from the statistical analysis

that individual otolaryngologists may have difficulty in

Rater 1 1.83 0.40 ⬍.001

consistently identifying and rating physical findings in

Rater 2 1.71 0.16 ⬍.001

their endoscopic assessments of the larynx. However,

Rater 3 2.19 1.12 ⬍.001

posthoc analysis of intrarater consistency found that the

Rater 4 2.07 0.94 ⬍.001 otolaryngologist-raters were able to separate patients into

Rater 5 2.00 0.22 ⬍.001 what they thought were treatment-appropriate and

GER ⫽ gastroesophageal reflux. treatment-inappropriate groups (Table V), which were

consistent with their mean severity scores for LPRD find-

ings. Furthermore, Table V does provide affirmative data

laryngitis, reflux laryngitis, and LPRD.2 Various laryn- to suggest that there can be consistency in the evaluation

geal findings have been associated with the diagnosis of of LPRD. The intent-to-treat data indicate that, overall,

LPRD. These include erythema or edema of the posterior the otolaryngologists each individually used a consistent

one-third of the glottis, hyperemia of the posterior larynx, method or methods to determine whether or not to recom-

cobblestoning, and “heaping up” or thickening of the in- mend treatment for presumed LPRD. Therefore, it is pos-

terarytenoid mucosa (pachydermia laryngis).12 The wide sible that despite inter-rater and intrarater variability for

array of nonspecific laryngeal findings and vague diagnos- the individual laryngeal findings associated with LPRD,

tic terminology all suggest that the true pathophysiology some overall consistency may be expected in the diagnosis

of LPRD is poorly understood. If otolaryngologists are to based on physical findings. This important fact implies

be successful in making a diagnosis of LPRD based on that other factors in the examination may be important in

clinical assessment without pH probe data, two criteria suggesting LPRD. These factors may include other fea-

must be satisfied. First, sensitivities and specificities tures such as subcordal edema, hypervascularity, or other

should be determined for various laryngoscopic findings in features not yet determined.

the diagnosis of LPRD. Second, otolaryngologists must be The average-measure intraclass correlation coeffi-

able to demonstrate reliability in identifying these physi- cients were reasonably high. This indicates that when

cal findings to make accurate diagnoses. If the laryngeal multiple raters are used to evaluate these physical exam-

findings cannot be reliably determined among different ination variables, reasonable reliability can be expected

otolaryngologists, even with knowledge of the sensitivities from the average of their ratings. This indicates that in

and specificities for the various physical findings, accurate future studies attempting to correlate physical findings

clinical diagnosis of LPRD will be difficult. Therefore, we with pH monitoring results or other tests for LPRD, mul-

sought to determine the reliability among otolaryngolo- tiple raters should be used for each patient examination

gists for the identification and quantification of various because the reliability of the average measure among

laryngeal physical findings potentially associated with those raters is acceptable. However, the lowest values for

LPRD. the average-measure intraclass correlation coefficients

Our data indicate that otolaryngologists vary signif- were noted for both edema and erythema of the aryte-

icantly in their ratings of the various laryngoscopic phys- noids. The posterior larynx, which has traditionally been

ical findings that could be associated with LPRD. We thought to be the primary site affected by LPRD, is the

found relatively poor inter-rater reliability for all of the most difficult area to rate and assess consistently. It is

visually assessed variables. This indicates that, even if the likely that this stems from the fact that the musculomem-

most sensitive or specific physical examination findings branous folds are sharply demarcated anatomic entities

among these variables were known for the diagnosis of and are generally white and lustrous. Therefore, edema

LPRD, different otolaryngologists might be unable to ac- and erythema, when present, are relatively easily dis-

curately diagnose LPRD based solely on such findings. We cerned. The same does not hold true for the arytenoid

were not entirely surprised that such variability among region, which has an exceedingly variable natural archi-

the otolaryngologist-raters was encountered because all of tecture from patient to patient.

these clinical variables are subjective in interpretation. Notably, this study used an idealized form of laryn-

Otolaryngologists are not alone in their difficulties with geal assessment for comparisons. In clinical practice, oto-

rating mucosal disease potentially attributable to GER. laryngologists may use indirect laryngoscopy or flexible

Studies in the gastroenterology literature have docu- fiberoptic laryngoscopy to visualize the larynx. Also, pa-

mented poor correlation coefficients ranging from 0.15 to tients may be examined at different times of the day or

0.40 for the assessment and grading of reflux esophagitis after different dietary challenges the night before their

among different endoscopists.13 Furthermore, the poor re- evaluation. Thus, additional variability may be introduced

liability of the ratings for the “severity of GER” and “like- into the examination process, which could lead to further

lihood GER component” variables suggests additional in- unreliability in assessment of the laryngeal findings in

consistency. Because these correlation coefficients were LPRD. It is possible that otolaryngologists who “subspe-

lower than those of the physical finding variables, otolar- cialize” in the management of voice disorders would ex-

yngologists are also likely to disagree on the degree of hibit better inter-rater and intrarater reliabilities for

Laryngoscope 112: June 2002 Branski et al.: Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Disease

1023

these clinical variables. However, because the vast major- BIBLIOGRAPHY

ity of patients with dysphonia are not initially treated by 1. Delahunty JE, Cherry J. Experimentally produced vocal cord

subspecialty laryngologists, establishing reliable laryn- granulomas. Laryngoscope 1968;78:1941–1947.

2. Ulualp SO, Toohill RJ. Laryngopharyngeal reflux: state of the

geal features among a wide array of otolaryngologists is

art diagnosis and treatment. Otolaryngol Clin North Am

important. Several additional laryngeal findings that 2000;33:785– 802.

could be attributed to LPRD were not assessed in the 3. Koufman JA, Amin MR, Panetti M. Prevalence of reflux in

current study. These include sulcus vocalis and subcordal 113 consecutive patients with laryngeal and voice disor-

ders. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000;123:385–388.

edema. Both of these findings can be difficult to assess and 4. Little JP, Matthews BL, Glock MS, et al. Extraesophageal pediat-

often require deeper placement of the scope. In our video ric reflux: 24-hour double-probe pH monitoring of 222 children.

segments the three-dimensional view is limited, so we did Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl 1997;169:1–16.

not think it appropriate to assess for these findings. Hy- 5. Hanson DG, Conley D, Jiang J, Kahrilas P. Role of esopha-

geal pH recording in management of chronic laryngitis: an

pervascularity of the interarytenoid region has also been overview. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl 2000;184:4 –9.

associated with LPRD, and we asked our raters to include 6. Sasaki CT, Toohill RJ. Introduction: 24-hour ambulatory pH mon-

hyperemia in consideration of “erythema,” to include this itoring for patients with suspected extraesophageal complica-

potential finding. tions of gastroesophageal reflux: indications and interpreta-

tions. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl 2000;184:2–3.

One potential solution to the problem of the unre- 7. Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assess-

liability of the laryngeal examination findings is to ing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 1979;86:420 – 428.

“train” otolaryngologists with a set of standardized ex- 8. Cicchetti DV, Sparrow SS. Developing criteria for establish-

ing interrater reliability of specific items in a given inven-

aminations, to foster consistency among the otolaryn- tory. Am J Ment Deficiency 1981;86:127–137.

gologists for scoring these variables. This would be sim- 9. Koufman JA. The otolaryngologic manifestations of gastro-

ilar to creating “trained listeners” who evaluate patient esophageal reflux disease. Laryngoscope 1991;101(Suppl

voices for dysphonia rating scales and so forth. Once 53):1–78.

10. Harrill WC, Stasney CR, Donovan DT. Laryngopharyngeal

reliability can be established for various laryngeal find- reflux: a possible risk factor in laryngeal and hypopharyn-

ings, further work can be conducted to determine which geal carcinoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999;120:

findings are sensitive and specific for LPRD. This would 598 – 601.

allow otolaryngologists to make the best evidence-based 11. Koufman JA, Burke AJ. The etiology and pathogenesis of

laryngeal carcinoma. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1997;30:

treatment decisions for patients with dysphonia poten- 1–19.

tially attributable to LPRD. Awareness of the laryngeal 12. Gaynor EB. Laryngeal complications of GERD. J Clin Gas-

manifestations of GER continues to grow, and the accu- troenterol 2000;30(Suppl):31–34.

13. Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, et al. Endoscopic assessment

rate diagnosis of LPRD may allow otolaryngologists to

of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and fur-

identify and treat the significant fraction of patients ther validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut 1999;

with LPRD-related dysphonia. 45:172–180.

Laryngoscope 112: June 2002 Branski et al.: Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Disease

1024

You might also like

- Reflux and LaryngitisDocument7 pagesReflux and LaryngitisyannecaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0196070920301198 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S0196070920301198 MainMeutia LaksaniNo ratings yet

- Lechien2018 Laryngopharyngeal Reflux TreatmentDocument14 pagesLechien2018 Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Treatmentveronikakryshtal97No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0022347614004491 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S0022347614004491 MainCindy Julia AmandaNo ratings yet

- A Nomenclature Paradigm For Benign Midmembranous Vocal Fold LesionsDocument7 pagesA Nomenclature Paradigm For Benign Midmembranous Vocal Fold Lesionsnatalia.gallinoNo ratings yet

- Laryngopharyngeal Reflux and Voice DisordersDocument20 pagesLaryngopharyngeal Reflux and Voice DisordersDiana RodriguezNo ratings yet

- 26 Jurnal LPRDocument5 pages26 Jurnal LPRaulia sufarnapNo ratings yet

- Changing Trends of Color of Different Laryngeal Regions in Laryngopharyngeal Reflux DiseaseDocument5 pagesChanging Trends of Color of Different Laryngeal Regions in Laryngopharyngeal Reflux DiseaseNoviTrianaNo ratings yet

- The Laryngoscope - 2019 - Weitzendorfer - Pepsin and Oropharyngeal PH Monitoring To Diagnose Patients WithDocument7 pagesThe Laryngoscope - 2019 - Weitzendorfer - Pepsin and Oropharyngeal PH Monitoring To Diagnose Patients WithfelitaNo ratings yet

- Mod2 06 Perceptual and Acoustic Characteristics VoiceDocument9 pagesMod2 06 Perceptual and Acoustic Characteristics VoiceEstefany HormazabalNo ratings yet

- 38.park2006 Diagnosis of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux AmongDocument5 pages38.park2006 Diagnosis of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux AmongWahyu JuliandaNo ratings yet

- Upper GI Surgery for Laryngopharyngeal RefluxDocument4 pagesUpper GI Surgery for Laryngopharyngeal Refluxaulia sufarnapNo ratings yet

- Erge LyonDocument12 pagesErge LyonLanNo ratings yet

- 1 IiomainDocument6 pages1 IiomainyandaputriNo ratings yet

- Correlation Between Laryngeal Sensitivity and Penetration/ Aspiration After StrokeDocument6 pagesCorrelation Between Laryngeal Sensitivity and Penetration/ Aspiration After StrokeRodrigo Felipe Toro MellaNo ratings yet

- Murray Secretion Scale and Fiberoptic Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing FEESDocument7 pagesMurray Secretion Scale and Fiberoptic Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing FEESjmunozsilvaNo ratings yet

- Del Gaudio 2005Document12 pagesDel Gaudio 2005Rodrigo Felipe Toro MellaNo ratings yet

- LkjkusteiDocument8 pagesLkjkusteiPeriyasami GovindasamyNo ratings yet

- Original Articles: Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy For Chronic Laryngo-Pharyngitis: A Randomized Placebo-Control TrialDocument9 pagesOriginal Articles: Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy For Chronic Laryngo-Pharyngitis: A Randomized Placebo-Control TrialAnonymous iM2totBrNo ratings yet

- Role of Rhinitis in Laryngitis: Another Dimension of The Unified AirwayDocument6 pagesRole of Rhinitis in Laryngitis: Another Dimension of The Unified AirwayPutri Rizky AmaliaNo ratings yet

- JurnalDocument7 pagesJurnalDaniel BudiNo ratings yet

- Gerd ConsensusDocument12 pagesGerd ConsensusRafael Monte Blanco FornerNo ratings yet

- Laryngeal DysplasiaDocument7 pagesLaryngeal DysplasiakarimahihdaNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Gastroesophageal Reflux DiseaseDocument5 pagesPediatric Gastroesophageal Reflux Diseasegemala wahabNo ratings yet

- ErgeDocument12 pagesErgess501No ratings yet

- 10.1002@lary.28626 EngDocument7 pages10.1002@lary.28626 EngRima Fairuuz PutriNo ratings yet

- Modern Diagnosis of GERD: The Lyon Consensus: Recent Advances in Clinical PracticeDocument12 pagesModern Diagnosis of GERD: The Lyon Consensus: Recent Advances in Clinical PracticeAgustín Lescano YacilaNo ratings yet

- Passive Smoke Exposure in Chronic Rhinosinusitis As Assessed by Hair NicotineDocument5 pagesPassive Smoke Exposure in Chronic Rhinosinusitis As Assessed by Hair NicotineAnonymous dkEBxwVJONo ratings yet

- Disfuncion de Cuedas VocalesDocument6 pagesDisfuncion de Cuedas VocalesJan SaldañaNo ratings yet

- Reflux Laryngitis: An Update, 2009-2012: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Ylancaster, CaliforniaDocument9 pagesReflux Laryngitis: An Update, 2009-2012: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Ylancaster, CaliforniaJaime Crisosto AlarcónNo ratings yet

- Laryngopharyngeal Reflux An Overview On The Disease and Diagnostic ApproachDocument6 pagesLaryngopharyngeal Reflux An Overview On The Disease and Diagnostic ApproachfrizkapfNo ratings yet

- 161120se-Bvsspa Sod 14008554 PDFDocument4 pages161120se-Bvsspa Sod 14008554 PDF06trahosNo ratings yet

- Evidence Based Assessment of Diagnostic Tests For Ventilator Associated PneumoniaDocument17 pagesEvidence Based Assessment of Diagnostic Tests For Ventilator Associated PneumoniaRoger HerreraNo ratings yet

- Vaezi LPR More Questions Than Answers CC 2010Document8 pagesVaezi LPR More Questions Than Answers CC 2010Phoespha MayangSarieNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Laryngopharyngeal Reflux, Perceptual, Acoustic, and Laryngeal T FindingsDocument5 pagesPediatric Laryngopharyngeal Reflux, Perceptual, Acoustic, and Laryngeal T Findingsarif sudianto100% (1)

- Preoperative Characteristics of Over 1,300 Functional Septorhinoplasty PatientsDocument7 pagesPreoperative Characteristics of Over 1,300 Functional Septorhinoplasty PatientsPablo Segales BautistaNo ratings yet

- Best of Best in ENTDocument34 pagesBest of Best in ENTNagaraj ShettyNo ratings yet

- The Associations of Floppy Eyelid Syndrome: A Case Control StudyDocument8 pagesThe Associations of Floppy Eyelid Syndrome: A Case Control StudyGiurgica MariusNo ratings yet

- X-Rays in The Evaluation of Adenoid Hypertrophy: It'S Role in The Endoscopic EraDocument3 pagesX-Rays in The Evaluation of Adenoid Hypertrophy: It'S Role in The Endoscopic EraDr.M.H. PatelNo ratings yet

- Children 10 00583Document15 pagesChildren 10 00583Cindy Julia AmandaNo ratings yet

- Abnormal Endoscopic Pharyngeal and LaryngealDocument7 pagesAbnormal Endoscopic Pharyngeal and LaryngealLilia ScutelnicNo ratings yet

- MRSA Chronic Bacterial Laryngitis: A Growing Problem: Patrick S. Carpenter, MD Katherine A. Kendall, MDDocument5 pagesMRSA Chronic Bacterial Laryngitis: A Growing Problem: Patrick S. Carpenter, MD Katherine A. Kendall, MDIntan Nur HijrinaNo ratings yet

- The Utility of Pitch Elevation in the Evaluation of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia- Preliminary FindingsDocument8 pagesThe Utility of Pitch Elevation in the Evaluation of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia- Preliminary FindingsESTEFANIA GEOVANNA MEJIA MACASNo ratings yet

- Reflux Evaluation and Management of Laryngopharyngeal: Charles N. FordDocument8 pagesReflux Evaluation and Management of Laryngopharyngeal: Charles N. Forddanny wiryaNo ratings yet

- Lechien Saussez Karkos Curr Opin 2018Document12 pagesLechien Saussez Karkos Curr Opin 2018alivanabilafarinisaNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Performance of Adenosine Deaminase Activity in Pleural Fluid a Single-centerDocument5 pagesDiagnostic Performance of Adenosine Deaminase Activity in Pleural Fluid a Single-centerq8xx75sjnyNo ratings yet

- RSI Score of 19 Best Predicts LPR in Allergy PatientsDocument8 pagesRSI Score of 19 Best Predicts LPR in Allergy PatientsSaid WibisanaNo ratings yet

- PAPER (ENG) - Swallowing Disturbance Questionnaire For Detecting DysphagiaDocument5 pagesPAPER (ENG) - Swallowing Disturbance Questionnaire For Detecting DysphagiaAldo Hip NaranjoNo ratings yet

- Evaluación de La Deglución Con Nasofibroscopía en Pacientes HospitalizadosDocument7 pagesEvaluación de La Deglución Con Nasofibroscopía en Pacientes HospitalizadosDANIELA IGNACIA FERNÁNDEZ LEÓNNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2090074016300172 Main PDFDocument4 pages1 s2.0 S2090074016300172 Main PDFnouvalrizkiamandaNo ratings yet

- Validity and Reliability of The Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10) 2003Document6 pagesValidity and Reliability of The Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10) 2003draanalordonezv1991No ratings yet

- Treatment Protocol VPI Jurnal ReadingDocument10 pagesTreatment Protocol VPI Jurnal ReadingWayan Sutresna YasaNo ratings yet

- Videostroboscopy in Laryngopharengeal RefluxDocument5 pagesVideostroboscopy in Laryngopharengeal RefluxLilia ScutelnicNo ratings yet

- Anticholinergic Medication Use Is Associated With Globus Pharyngeus (HAFT 2016)Document5 pagesAnticholinergic Medication Use Is Associated With Globus Pharyngeus (HAFT 2016)DANDYNo ratings yet

- 55.wilson1989pharyngoesophageal DysmotilityDocument5 pages55.wilson1989pharyngoesophageal DysmotilityWahyu JuliandaNo ratings yet

- Reliable Yale Scale Rates Pharyngeal Residue SeverityDocument8 pagesReliable Yale Scale Rates Pharyngeal Residue SeverityGisele DiasNo ratings yet

- Iranjradiol 15645Document5 pagesIranjradiol 15645Putri YingNo ratings yet

- The Vocal Fold Dysfunction QuestionnaireDocument5 pagesThe Vocal Fold Dysfunction Questionnairemajid mirzaeeNo ratings yet

- Raynaud’s Phenomenon: A Guide to Pathogenesis and TreatmentFrom EverandRaynaud’s Phenomenon: A Guide to Pathogenesis and TreatmentFredrick M. WigleyNo ratings yet

- Mr. Diaz Medical English II: WWW - Usat.edu - PeDocument10 pagesMr. Diaz Medical English II: WWW - Usat.edu - PelakjdlkaNo ratings yet

- Frequency Adverbs: Mr. Diaz Medical English IIDocument10 pagesFrequency Adverbs: Mr. Diaz Medical English IIlakjdlkaNo ratings yet

- Vaneerdewegh2002 PDFDocument5 pagesVaneerdewegh2002 PDFlakjdlkaNo ratings yet

- Validación Del DASS en Trabajadores Hospitalarios en China PDFDocument9 pagesValidación Del DASS en Trabajadores Hospitalarios en China PDFlakjdlkaNo ratings yet

- SAS BigData FinalDocument37 pagesSAS BigData FinalDevika RadjkoemarNo ratings yet

- Resting Membrane PotentialDocument42 pagesResting Membrane PotentiallakjdlkaNo ratings yet

- Validación Del DASS en Trabajadores Hospitalarios en China PDFDocument9 pagesValidación Del DASS en Trabajadores Hospitalarios en China PDFlakjdlkaNo ratings yet

- Wealth of Nations - Smith PDFDocument754 pagesWealth of Nations - Smith PDFlakjdlkaNo ratings yet

- Sataloff 2012Document7 pagesSataloff 2012lakjdlkaNo ratings yet

- Validación DASS en Colombia PDFDocument11 pagesValidación DASS en Colombia PDFlakjdlkaNo ratings yet

- Koufman2002 PDFDocument4 pagesKoufman2002 PDFlakjdlkaNo ratings yet

- Caimi 2016Document6 pagesCaimi 2016lakjdlkaNo ratings yet

- Koufman2002 PDFDocument4 pagesKoufman2002 PDFlakjdlkaNo ratings yet

- Validación DASS en Colombia PDFDocument11 pagesValidación DASS en Colombia PDFlakjdlkaNo ratings yet

- Antioxidant Potential of The Blood in Men With Obstructive Sleep Breathing DisordersDocument3 pagesAntioxidant Potential of The Blood in Men With Obstructive Sleep Breathing DisorderslakjdlkaNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Reflux in 113...Document4 pagesPrevalence of Reflux in 113...Ximena Acuña RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Branski2002 PDFDocument6 pagesBranski2002 PDFlakjdlkaNo ratings yet

- Resting Membrane PotentialDocument42 pagesResting Membrane PotentiallakjdlkaNo ratings yet

- Free Radical Oxidation in Sleep Disorders: in Andro-And Menopause (Literature Review)Document11 pagesFree Radical Oxidation in Sleep Disorders: in Andro-And Menopause (Literature Review)lakjdlkaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Manifestations of Parkinson Disease - UpToDateDocument13 pagesClinical Manifestations of Parkinson Disease - UpToDatelakjdlkaNo ratings yet

- Differences in lipid peroxidation and immune biomarkers between depression and bipolar disorderDocument57 pagesDifferences in lipid peroxidation and immune biomarkers between depression and bipolar disorderlakjdlkaNo ratings yet

- Daytime Sleepiness, Snoring, and Obstructive Sleep ApneaDocument7 pagesDaytime Sleepiness, Snoring, and Obstructive Sleep ApnealakjdlkaNo ratings yet

- Assessment of The System "Lipid Peroxidation - Antioxidant Protection"Document6 pagesAssessment of The System "Lipid Peroxidation - Antioxidant Protection"lakjdlkaNo ratings yet

- Normative Values For The Voice Handicap Index-10: Yzpittsburgh, PennsylvaniaDocument4 pagesNormative Values For The Voice Handicap Index-10: Yzpittsburgh, PennsylvanialakjdlkaNo ratings yet

- Free Radicals, Antioxidants, Nuclear Factor E2 Related Factor 2 and Liver DamageDocument18 pagesFree Radicals, Antioxidants, Nuclear Factor E2 Related Factor 2 and Liver DamagelakjdlkaNo ratings yet

- Oxidative Stress Markers and Antioxidant Therapy in Obstructive Sleep ApneaDocument6 pagesOxidative Stress Markers and Antioxidant Therapy in Obstructive Sleep ApnealakjdlkaNo ratings yet

- Oxidative Stress Is Involved in Fatigue Induced by Overnight Deskwork As Assessed by Increase in Plasma Tocopherylhydroqinone and HydroxycholesterolDocument7 pagesOxidative Stress Is Involved in Fatigue Induced by Overnight Deskwork As Assessed by Increase in Plasma Tocopherylhydroqinone and HydroxycholesterollakjdlkaNo ratings yet

- Review Article: Sleep Deprivation and Oxidative Stress in Animal Models: A Systematic ReviewDocument15 pagesReview Article: Sleep Deprivation and Oxidative Stress in Animal Models: A Systematic ReviewlakjdlkaNo ratings yet

- Review Article Reactive Oxygen Species-Induced Lipid Peroxidation in Apoptosis, Autophagy, and FerroptosisDocument14 pagesReview Article Reactive Oxygen Species-Induced Lipid Peroxidation in Apoptosis, Autophagy, and FerroptosislakjdlkaNo ratings yet

- Shwebo District ADocument280 pagesShwebo District AKyaw MaungNo ratings yet

- Karl-Fischer TitrationDocument19 pagesKarl-Fischer TitrationSomnath BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- Disaccharides and PolysaccharidesDocument17 pagesDisaccharides and PolysaccharidesAarthi shreeNo ratings yet

- 3.0MP 4G Smart All Time Color Bullet Cam 8075Document2 pages3.0MP 4G Smart All Time Color Bullet Cam 8075IshakhaNo ratings yet

- DS - 20190709 - E2 - E2 198S-264S Datasheet - V10 - ENDocument13 pagesDS - 20190709 - E2 - E2 198S-264S Datasheet - V10 - ENCristina CorfaNo ratings yet

- Reflection Paper IIDocument1 pageReflection Paper IIHazel Marie Echavez100% (1)

- FS 3 Technology in The Learning EnvironmentDocument24 pagesFS 3 Technology in The Learning EnvironmentJayson Gelera CabrigasNo ratings yet

- Research Methodology: by Asaye Gebrewold (PHD Candidate)Document17 pagesResearch Methodology: by Asaye Gebrewold (PHD Candidate)natnael haileNo ratings yet

- 2021062476 (1)Document8 pages2021062476 (1)Naidu SairajNo ratings yet

- Robert Frost BiographyDocument3 pagesRobert Frost Biographypkali18No ratings yet

- Corporate Governance Committees in India: Key Reports and RecommendationsDocument39 pagesCorporate Governance Committees in India: Key Reports and Recommendationskush mandaliaNo ratings yet

- The Most Efficient and Effective Ways To Address New Literacies FDocument61 pagesThe Most Efficient and Effective Ways To Address New Literacies FAlpha MoontonNo ratings yet

- Cot 1 Detailed Lesson Plan in Science 10Document3 pagesCot 1 Detailed Lesson Plan in Science 10Arlen FuentebellaNo ratings yet

- From Verse Into A Prose, English Translations of Louis Labe (Gerard Sharpling)Document22 pagesFrom Verse Into A Prose, English Translations of Louis Labe (Gerard Sharpling)billypilgrim_sfeNo ratings yet

- SM6 Brochure PDFDocument29 pagesSM6 Brochure PDFkarani ninameNo ratings yet

- R. Paul Wil - Rico ChetDocument7 pagesR. Paul Wil - Rico ChetJason Griffin100% (1)

- PHY3201Document3 pagesPHY3201Ting Woei LuenNo ratings yet

- FisheryDocument2 pagesFisheryKyle GalangueNo ratings yet

- Thermodynamics efficiency calculationsDocument3 pagesThermodynamics efficiency calculationsInemesit EkopNo ratings yet

- iGCSE Anthology English Language A and English LiteratureDocument25 pagesiGCSE Anthology English Language A and English LiteratureBubbleNo ratings yet

- Unit4 Dbms PDFDocument66 pagesUnit4 Dbms PDFRS GamerNo ratings yet

- Appendix A. Second QuantizationDocument24 pagesAppendix A. Second QuantizationAgtc TandayNo ratings yet

- Session 7 Valuation of ITC Using DDMDocument24 pagesSession 7 Valuation of ITC Using DDMSnehil BajpaiNo ratings yet

- Module #5 Formal Post-Lab ReportDocument10 pagesModule #5 Formal Post-Lab Reportaiden dunnNo ratings yet

- BTechSyllabus EC PDFDocument140 pagesBTechSyllabus EC PDFHHNo ratings yet

- Philo Q1module 4Document18 pagesPhilo Q1module 4Abygiel Salas100% (1)

- Macroeconomics: University of Economics Ho Chi Minh CityDocument193 pagesMacroeconomics: University of Economics Ho Chi Minh CityNguyễn Văn GiápNo ratings yet

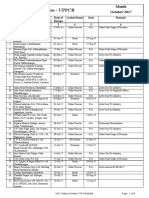

- NOC Status for UPPCB in October 2017Document6 pagesNOC Status for UPPCB in October 2017Jeevan jyoti vnsNo ratings yet

- Business PlanDocument15 pagesBusiness PlanAwel OumerNo ratings yet

- Angle Beam Transducer Dual ElementDocument5 pagesAngle Beam Transducer Dual ElementWilliam Cubillos PulidoNo ratings yet