Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The 21st Century Model Prison: Simon Henley

Uploaded by

vaidehi vakilOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The 21st Century Model Prison: Simon Henley

Uploaded by

vaidehi vakilCopyright:

Available Formats

The 21st century model prison

Simon Henley

Architect, UK.

03

By 2002 there were more than 70,000 prisoners in Britain. The number of prisoners 03.1

exceeded the number of available prison places. This paper records the development simon.henley@buschowhenley.co.uk

of a model prison building designed to compliment a new regime founded on the

principle of learning. The director of the Do Tank Hilary Cottam commissioned the

research. Buschow Henley developed the design over a two-month period in Spring

2002 in conjunction with the Do Tank and the Home Office Prison Service. Prior to,

and during the design process visits were made to HMYOI Reading, HMP Wormwood

Scrubs, HMP Wandsworth and HMP Grendon.

It is now a year since the design was developed, and “Learning Works: The

21st Century Prison” was published. This paper represents the model design, drawing

comparisons with a number of historic examples and current conventions. Given

that this is in essence a design exercise, whilst logical, it cannot

claim to be absolutely rigorous. This may at times be evident.

The 21st Century Model Prison seeks to define a new prison

typology organised to achieve freedom of activity and inhabitation

for the prisoner. The prisoner is enabled to engage in a range of

activities inside and outside the building, supported by a circulation

and management system that brings the human expertise to the

prisoner environment. The design inverts the logic of Bentham’s

Panopticon ‘inspection house’ (1791) and subsequent radial prison

models (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Panopticon

The model evolved to enable learning to be integrated in to all aspects of (source: Bentham, 1791)

prison life and to be integrated into every space, the objective being to enable prisoners

to resettle into society with a significantly reduced incidence of recidivism. The

Proceedings . 4th International Space Syntax Symposium London 2003

building enables both staff and prisoner time to be redirected towards the new learning

regime. It helps in the management of the prisoner, freeing up staff time for learning

initiatives and better management. It mitigates the intense and wasteful aspects of

managed movement and security through the organisation of prisoners into viable

groups, housed in simple spaces, ostensibly learning environments adjacent to freely

accessible discrete external space. As a result staff and prisoners are enabled by the

architecture to focus on activity.

A prison population of 400 was chosen , this being the upper limit advocated

by the Woolf Report (Woolf and Tumim, 1991) following the HMP Manchester

(Strangeways) riots. The size also ensures that prisons can be sited locally in towns

and cities close to the prisoners’ families and to the courts. The need to free up

capital assets within the prison service to reinvest in the new model imposed a further

03.2 physical restriction on the prison. It was agreed that the footprint must be smaller

than a typical Victorian inner-city prison releasing land for commercial

development. The model is site non-specific (Figure 2).

British prisons are categorised from high security Category A

to open prisons Category D. This reflects the category of prisoner

housed in the prison. In this new regime the model prison would

accommodate all the current prisoner categories A to D.

Our starting point was the brief. For our purposes we will define

the brief as a list of activities, which give rise to a list of places or

parts, which in turn are ascribed a size and are aggregated. In a prison

the activities include work, education, cooking, eating, exercise,

administration and management, time in the open air and movement,

Figure 2: The 21st Century Model and the parts include the cell, wing, education, association, resettlement

Prison (photograph by Andrew Putler, 2002)

accommodation, visitor provision and the deployment of outside space. We found

spaces to be inappropriate for their use, and their relative position unsuitable. This

functional analysis of the brief led us to a new prison typology, which is defined by

a radical strategy of restricted and efficient movement. The result is a building,

which is the converse of the Panopticon and the radial prison-type. This paper presents

our model within a limited historic context.

In the Panopticon and radial prison (e. g. HMP Pentonville, 1842) we find a

building type designed to separate and “warehouse” people (Figure 3). Long linear

wings of cells (140-260 cells over three landings per wing at HMP Wandsworth) are

laid out for the most efficient surveillance. Although the radial prisons have

subsequently had to adapt to accommodate a contemporary non-separated regime,

The 21st century model prison

their original arrangement was conceived to accommodate a regime focused on

prisoner reflection and purposelessness. Today the prisoners remains largely confined

to their cells, otherwise exposed by the plan to the total prison population-the crowd.

Each is an anonymous inmate. At best, each will conform but not commit

psychologically to prison society. Each is confined deep within the prison, a

freestanding building, and pavilion in a landscape.

By contrast, the new model is founded on the principle of learning and training,

where the prisoner lives in a semi-autonomous unit, or house, adjacent to a

“roundabout” of efficient circulation, which feeds directly to each of the spatial

components of the prison. Within the house the prisoner is a member of an accountable

group, living close to external space, defined and controlled by a chequerboard array

of buildings and external courtyard gardens.

03.3

Figure 3: Pentoville Prison, aerial

view (source: Toy et al., 1994)

Currently, the role of the prison officer is to manage the prison population

and maintain security. Much of their time is spent moving prisoners between wings,

and shuttling them to and from workshops, education, library and association spaces,

back and forth from reception, and across to healthcare, counselling and sports

facilities. This entails numerous security checks, employs many staff and consumes

much of the day, resulting in a regime which leaves little useful time. In the event of

a delay a prisoner will be forced to forego the activity. When there are staff shortages

prisoners are restricted to the wing and may be locked in their cells for up to 23

hours a day.

The key to our research was to question the efficiency of the prison, and to

recognise that time is a constraint on the prison regime. The logic of the 21st century

prison lies in its morphology, and in the extent to which prisoners physically move

about within the building. It is evident that a conventional prison is a complex place,

with a complex morphology. It comprises many parts, each linked to the others in

numerous ways. This is borne out in a variety of buildings developed to accommodate

large organisations, its purpose being to centralise services and hardware in order to

Proceedings . 4th International Space Syntax Symposium London 2003

achieve economies of scale. The dispersed population moves to and from centralised

activities when required. This is a tried and tested model for efficiency for many

organisations and their buildings, ranging from the factory, hospital and supermarket,

to the university and prison, each governed by the same principles of economy and

apparent efficiency. However, this assumes that there is freedom of movement for

the dispersed population to the centralised activity, and that moving the majority to

the serving minority (people) or hardware is the cheapest option. In the case of the

prison this assumption does not seem to apply.

In a simple study (where a node (n) represents a dispersed activity, a point on

a map, or a place in a building, and L the number of possible connecting lines or

routes.), we have shown that with an increase in the number of nodes there is a

multiplying effect on the number of links or possible connections between those

03.4 nodes. For example, when an organisation consists of one node there are no links,

for two there is one, for three there are three, for four there are six, for five there are

ten, for six there are fifteen and so on. Where there are 100 nodes there are 4950

connecting lines. This observation is formalised in the arithmetic series L= n (n-1)/

2 where n is the number of nodes and L the number of links (Figure 4). Each link

will employ staff time and eat into the regime. With increased complexity this equates

to a multiplying increase in time and cost. Our model seeks to simplify the prison

and can be seen as a direct response to this arithmetic formula.

Figure 4: The Arithmetic Series

L= n (n-1)/ 2. The effect on circu-

lation of increasing numbers of

location-based activities

(source: Buschow Henley, 2002)

Given the implications of this arithmetic formula it is evident that the

deployment of space and activities within a prison is wrong, and that prisoner and

staff time would be better used if movement was minimised. This is achieved by

creating a series of autonomous physical units (or Houses), in which groups of

prisoners may live, work and learn. In this scenario centralised functions are kept to

the minimum and specialist people move to the prisoner group. Because the specialists

are entrusted to move themselves this is, in this instance, more economic. The

Model seeks to simplify the prison, literally to uncomplicate it. It is important to

The 21st century model prison

stress that the adoption of a house model, in place of linear wings is not radical.

HMYOI & RC Feltham, which opened in 1983, was modelled on the ‘New

Generation’ American prisons, which proposed houses in a campus layout. This

was subsequently formalised in the UK Prison Design Briefing System (PDBS,

1989) and the Woolf Report (1991) advocating the construction of wings for small

groups of 50-70 inmates, and put into practice in triangular houses at HMP Woodhill

(Milton Keynes, 1991), Doncaster and Lancaster Farms. PDBS guidelines currently

indicate paired rectangular house blocks accommodating 50-70 inmates. There are

five logical developments that distinguish our House model from previous house

models, which do little more than reshape and downsize the Victorian prison wing:

1. The house could be semi-autonomous, not just a dormitory, mitigating

prisoner movement

2. The group size suggests an accountable prisoner group

3. Houses are integrated into a compact and efficient circulation system 03.5

4. Houses are arranged on a chequerboard (not as pavilions) thus not

contributing to the controlled use of outside space

5. The house offers an immediate link to outside space, mitigating the

time and cost associated with achieving time in the open air

What follows is a more detailed explanation of these five steps of logic.

A Semi-Autonomous Unit—The House

How appropriate is it to restrict the movement of a prisoner,

and confine them to an autonomous live-learn-work unit

i.e. a house? Employing space-time geography to test

acceptability we mapped a working adult's day to illustrate

how much time people spend at work, leisure or at home

(Figure 5). If a prisoner day was to conform to the same

space-time geography they would normally be expected in

the new regime to spend 50-90% of the day in the House,

and 10-50% in centralised communal spaces. We may also

benchmark this for acceptability against the current rise in

home-based live work enabled by technology.

An Accountable Prisoner Group Figure 5: Breakdown of activities

as a percentage of an average day

UK PDBS guidelines concur with a similar policy in USA and Europe in advising a (source: Buschow Henley, 2002)

group size of 50-70, yet there is no evidence available to ratify this group size.

Instead comparative institutions and organisations use a group size of 30-40, where

each individual in the group is known and trusted by the community. School class

sizes and the armed forces would suggest a group size of about 30. Models for

Proceedings . 4th International Space Syntax Symposium London 2003

residential care for the elderly use a group size of 30-40 . We understand that the

latter strikes a balance between anthropological and economic benefit. Key both for

staff management and reformative benefit is the opportunity for the prisoner to

become personally accountable to their community (the House) for their actions,

mitigating problems of drugs, bullying and the resulting need for Vulnerable Prisoner

Units and Segregation (cells). They become part of an identifiable group within a

larger community. Uniquely HMYOI Feltham employs smaller houses with 32

inmates.

“Roundabout” of controlled, compact and efficient circulation

Whilst the model disperses activity to the autonomous house there remains a

significant element of centralised Communal facilities. Historic and contemporary

models for prison circulation are complex. The segregating effect of circulation

03.6 between wings and centralised activities itself forms a barrier to prisoners trying to

access centralised services i.e. to partake in activity. Our model proposes a single

ring of circulation, in effect a “roundabout” from which there is direct dual-level

access to the Houses and Communal facilities. To arrive at this arrangement we

developed two distinct diagrams: a linear one and a centripetal version. The first

describes a line of circulation with Houses (and gardens) to one side and Communal

facilities to the other (Figure 6). The second, the centripetal diagram, envisages a

cluster of Communal facilities at the heart of the organisation, with a circular array

of Houses on the outside (Figure 7). The 21st Century Prison combines the two

(Figure 8). The Communal facilities are clustered and into this, a ring or “roundabout”

of circulation is embedded, in effect a linear arrangement. Above a ‘table’ of Houses,

have direct access to the ground floor circulation.

Figure 6: A linear relationship

between Houses and central-

ised communal spaces

(source: Buschow Henley, 2002)

Figure 7: A centripetal relation-

ship between Houses and

centralised communal spaces

(source: Buschow Henley, 2002)

The 21st century model prison

Figure 8: The 21st Century

Model Prison relationship

between Houses and central-

ised communal spaces

(source: Buschow Henley, 2002)

A Chequerboard replaces pavilions in a Landscape

Historically prisons have been designed with little regard to the shape of external

space. Like pavilions in a landscape, the prison buildings float in a sea of external

space bounded by a secure perimeter (Figure 9). The fluid and continuous nature of

these spaces means that once outside a prisoner can move to any point inside the

perimeter. This has a detrimental effect on access to and the use of this external 03.7

space. It also has security implications. External space is extremely hard to control

and use without intensive management. In our model we use the buildings to enclose

a series of discrete external spaces in a chequerboard array (Figure 10).

d) a)

c) b)

Figure 9: The existing distribution of prison buildings within their sites (clockwise

from top right):

a) HM Maidstone. Site 20.9 ha. Roll 544 prisoners. Density: 383m2 per prisoner

b) HMYOI Feltham. Site 15.5 ha. Roll 894 prisoners. Density: 173m2 per prisoner

c) HM Pentonville. Site 6.2 ha. Roll 1112 prisoners. Density: 56m2 per prisoner

d) HM Blundeston. Site 18.5 ha. Roll 424 prisoners. Density: 435m2 per prisoner

(source: Buschow Henley, 2002)

Proceedings . 4th International Space Syntax Symposium London 2003

Figure 10: The Chequerboard

One Hectare Prison. The Houses

rest above the communal facili-

ties. The voids in the upper layer

of the prison allow light to reach

the external spaces on the

ground floor. One hectare can

house up to 396 prisoners

(source: Buschow Henley, 2002)

Depth gives way to Immediacy

03.8 Traditionally, cells are located deep within the building, far from the exterior,

exacerbating the management of access from cell to exterior. In our model the

relationship between the interior, exterior and circulation is radically different. The

“roundabout” is internal, intelligible and controlled, and therefore efficient. Access

between each House and the Communal facilities is controlled, but critically there is

free access to a specific associated enclosed courtyard from each House and

Communal facility, requiring only the minimum of surveillance (Figure 11). This

enables the prison service to provide time in the open air at any time throughout the

day when the prisoner is not locked in their cell (Figure 12). Accessible, external

space is provided close to the cell, the learning environment and the place of

vocational learning/ employment. This immediacy completes a strict spatial logic

for the prison. Each House garden and Communal courtyard is framed by the walls

of surrounding buildings, which eases the management of external space.

Figure 11: Model for efficient cir-

culation and accessible external

space. External space is freely

and immediately accessible while

access between Houses and

communal spaces is controlled

and intelligible

(source: Buschow Henley, 2002)

Figure 12: House and garden. An

immediate connection

(source: Buschow Henley, 2002)

The 21st century model prison

Analysis of the ground floor plan of

the model carried out by Mavridou highlights

the extent to which the spatial components

of the prison are integrated by the

“roundabout” of circulation. The PESH study

illustrates that this is a control model (Figure

13). This relieves the prisoner from the

pressure of supervision. This is the exact

opposite of the Panopticon, which being an

open system is a surveillance model.

What follows is a brief description of

the architecture. The prison has been designed

throughout to provide good natural ventilation

Figure 13: PESH analysis of the ground floor of the 21st

03.9

and daylight levels. Materials and construction Century Model prison (source: Mavridou, 2003)

were considered. In looking at the cell, the

House and the prison as a whole the text refers only to function and morphology.

The Cell

The Panopticon locates each individual prisoner in a cell. The prisoner inhabits a

space between the governor, at the heart of the centric plan, and the light (perimeter

windows). Being continuously visible, the prisoner enters a self-conscious state.

One cannot experience a cell as Bentham conceived it. However the conventional

position of the door, in the centre of the short inside wall, on axis with the window

in the short outside wall, in a typically tall, narrow and long room places the prisoner

on an axis between the light and the prison officer’s gaze.

Within the cell accommodates a lavatory, basin, bed, desk, chair & cupboard.

Its proportions are most like that of the domestic lavatory - not a good association

for a person to make with their living space. The result is a room that looks and

smells like a lavatory. A cell is also laid out like a badly planned bathroom; the bed

runs parallel to the long wall, as the bath might in a bathroom, which leaves no

useable floor space. In to this we place the prisoner whom we seek to normalise

(Figure 14).

Figure 14: The Cell

(source: Buschow Henley, 2002)

Proceedings . 4th International Space Syntax Symposium London 2003

Our 8m2 cell is instead planned to be as useful as possible, in particular for

learning. The strength of modern-day construction materials has enabled us to locate

the bed on the outside wall, at high level, not unlike the top bunk of a bunk bed,

visible from the door. The bed is constructed as a monolithic slab, mitigating the

risk of hanging. The table, pictured in front of the window, can be moved. Here a

networked keyboard and screen provide the necessary tools for study and

communication via an intranet/ prison cable TV network. The remaining space

within the cell is open to use and furnish in a variety of ways. Each cell is paired

with a neighbouring one – a buddying cell linked by a pair of sliding doors controlled

by the individual prisoners, but overridden by staff in case of an emergency such as

an attempted suicide. This mitigates the risk of inmate self-harm (Figure 15).

The research findings of Erving Goffman and Peter Townsend into the idea

03.10 of the ‘total institution’ and institutionalisation through ‘structured dependency’,

conclude by emphasising the importance of choice within an institution . Here the

prisoner’s ability to choose reduces their dependency, and their institutionalisation,

directly improving their life skills and their likelihood of successful resettlement .

The capacity to share space and rearrange furniture enables neighbouring prisoners

to take the opportunity to enrich their personal accommodation, and in turn their

day-to-day lives. The act of choosing becomes a potent antidote to institutionalisation.

Choice extends throughout the prison and activity-focused prison regime. Each cell

is provided with an adjoining room (included within the 8m2) accommodating a

WC, basin and shower to further simplify the building and reduce pressure on prison

staff to manage hygiene and ablutions. Storage is built in beside the table and bed.

The cell interior is exposed concrete. Perhaps decoration or mural painting by the

prisoner should be encouraged, giving further scope for choice for the purpose of

reform (Figure 16).

Figure 15: The 21st Century Model Figure 16: Plan of two cells, showing the lower

Prison Cell level on the left and the upper level on the right

(source: Buschow Henley, 2002) (source: Buschow Henley, 2002)

The 21st century model prison

The House

Each House accommodates a number of cells (here 36 in pairs, 12 per floor over 3

floors) describing a U-shape around a central atrium (Figure 17). Below, the lowest

floor of the House is laid out around a central space designed for House meetings,

leisure and dining. This opens up directly onto a walled garden to the south, and is

lit by a large south-facing window and skylight. Cellular space around the perimeter

includes a House office, classroom and Subject Room (providing group learning

facilities for 2/3 of the House at any time), kitchen and gym as well as staff and

prisoner WCs. The kitchen is staffed by House prisoners who provide three meals a

day at set times. Supplies are stored centrally within the communal accommodation.

The upper floors also accommodate four rooms for One-to-One

mentoring, two multipurpose rooms (treatment/ consulting rooms)

and a staff room (Figure 18). Access to and from the House is

controlled via a stair and hall with direct access to the “roundabout” 03.11

(circulation) on the ground floor. This is a key control point within

the prison. There are eleven Houses, each 288m2, accommodating

a total of 396 people within the prison walls. The garden, a mix of

hard and soft landscaping, can be used for casual games, sport and

as a kitchen garden to grow fruit and vegetables for the House.

Figure 17: Sectional perspective of a House Figure 18: Plans of the House

and garden built above the centralised com- –(source: Buschow Henley, 2002)

munal facilities and courtyards

(source: Buschow Henley, 2002)

Communal Activities

Below the table of Houses the ground floor accommodates Reception, three central

workshops providing space for half the prison population to work simultaneously,

stores, a shop, a health centre, sports hall, 20m indoor swimming pool, a multi-faith

centre, an administration block, visiting area and central library stacks holding up to

Proceedings . 4th International Space Syntax Symposium London 2003

20,000 books distributed to the houses in a mobile unit. Each location-based activity

is paired with a directly accessible outside space appropriate to the function (Figure

19). In the southwest corner there is a 5-a-side football pitch with spectator facilities

from the controlled space of the Visiting area. The total footprint of the buildings

including the courtyards and gardens on the upper and lower levels is one hectare. A

6m wide zone between the building perimeter and the internal fence doubles as a

road (for deliveries) and a 400m running track. Between the fence and the 5.2m high

outside wall there is a 6m wide sterile area. On a larger site, in a rural setting the

prison buildings may be extended to accommodate larger workshops and learning

facilities (Figure 20).

03.12

Figure 19: Plan of centralised communal facilities Figure 20: Sectional perspective of the 21st Cen-

on the ground floor (source: Buschow Henley, 2002) tury Model Prison (source: Buschow Henley, 2002)

Beyond the Wall

Two further Houses are located on the outside of the wall. At ground floor level one

accommodates security, the pedestrian entry point and a covered holding area for

incoming and outgoing vehicles. The other, a Visitors centre, provides a waiting

room, refreshments and counselling facilities for family and friends. Above, the two

Houses accommodate prisoners on resettlement programmes, becoming in effect a

Category D open prison. These prisoners would be employed during the day in the

community, but return to their cells in the evening. In a third scenario, the House is

replicated deep in the community as a halfway house, which would be run by the

probation service. Key here is the recurring presence of the House, the group and

the communities within the wall, outside the wall and beyond (Figure 21). Whilst

the Model does not envisage space standards changing, the specification of materials

and finishes would not be so robust on the outside. Internal layouts of the houses

located outside the walls could be replanned to provide family accommodation.

The 21st century model prison

Figure 21: The 21st Century Model Prison within

society. Houses are located within the prison walls,

outside the prison walls and in the community

(source: Buschow Henley, 2002)

Conclusion

The 21st Century Prison proposes a new typology in which time-based efficiency

liberates the prisoner to focus on activity within the cell, the house (a semi-

autonomous unit) and the centralised communal facilities. The building strictly

separates functional space from a shallow “roundabout” of movement. All primary 03.13

internal spaces have an immediate accessible connection to the outside, and the

chequerboard architecture of the buildings controls this outside space (Figure 22).

Here the prisoner becomes a member of an accountable group.

Figure 22: The 21st Century Model Prison

(photograph by Andrew Putler, 2002)

Whilst the prison appears to be liberal, the arrangement of spaces both inside

and outside is strictly controlling. It is for this reason, however, that activity within

clearly defined spaces is free. In this environment the prisoner is not judged by their

conformity but by their varied activity and achievement. In the one-hectare prison

an invisible pedagogy is at work.

The architecture fulfils both a social and psychological role, through the

creation of humane, secure but not repressive environments, and an economic role,

crucially by releasing staff time to conduct the new regime. The design is a blueprint

for both palpable quality and managerial efficiency.

Proceedings . 4th International Space Syntax Symposium London 2003

References

Cottam, H. et al., 2002, Learning Works: The 21st Century Prison, London, The Do Tank

Fairweather, L., 1992, “Prisons”, The Architects Journal, 9, Volume 196, pp. 28-38

Foucault, M., 1975, Discipline and Punish, London, Routledge

Goffmann, E., 1968, Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates,

Hanmondsworth, Middlesex, Penguin

Hagerstrand, T., 1975, “Space, Time and Human Conditions”, in A. Karlquist, Dynamic Allocation of

Urban Space, Farnborough, Saxon House

Haggart, G., 1999, Behind Bars. The Hidden Architecture of England’s Prisons, Swindon, English Heritage

Henley, S., 2002, “The Learning Building”, in H. Cottam, Learning Works: The 21st Century Prison,

London, The Do Tank

HM Prison Service, 1999, Prisoners’ Information Book. Male Prisoners and Young Offenders, London,

Prison Reform Trust

HM Prison Service, 2001, Safer Prison Building Requirements

Koolhaas, R., 1997, S, M, L, XL, Koln, Benedikt Taschen Verlag GmbH

Markus, T., 1993, Buildings and Power. Freedom and Control in the Origin of Modern Building Types,

London, Routledge

Mavridou, M., 2003, Prisons: Rules or Walls?

03.14 Torrington, J., 1996, Care Homes for Older People: a Briefing and Design Guide, London, SPON

Townsend, P., 1964, The Last Refuge, London, Routledge and Kegan Paul

Toy, M. et al., 1994, Architecture of Incarceration, London, Academy Editions

Tumim, S., 1997, The Future of Crime and Punishment, London, Phoenix

Woolf, 1991, Prison Disturbances April 1990- Report of the Inquiry, London, HMSO

The 21st century model prison

You might also like

- Compass 5000.1.12 157605HDocument360 pagesCompass 5000.1.12 157605HApurbajyoti Bora100% (2)

- 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of SleepFrom Everand24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of SleepRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (25)

- Introduction to Idiomaterial Life PhysicsDocument12 pagesIntroduction to Idiomaterial Life PhysicsKate Israel AHADJINo ratings yet

- Dental Pulp TissueDocument77 pagesDental Pulp TissueJyoti RahejaNo ratings yet

- Toyota's Marketing StrategyDocument14 pagesToyota's Marketing StrategyLavin Gurnani0% (1)

- Pune Historical MonumentsDocument13 pagesPune Historical Monumentsvaidehi vakilNo ratings yet

- Prison Architecture Reflects SocietyDocument8 pagesPrison Architecture Reflects SocietyVlade PsykovskyNo ratings yet

- Quiz Chapter 1 Business Combinations Part 1Document6 pagesQuiz Chapter 1 Business Combinations Part 1Kaye L. Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Flexible Architecture-1Document10 pagesFlexible Architecture-1vrajeshNo ratings yet

- Gen - Biology 2 Module 2Document12 pagesGen - Biology 2 Module 2Camille Castrence CaranayNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument32 pagesCase StudyHemantikaNo ratings yet

- Operational Readiness Guide - 2017Document36 pagesOperational Readiness Guide - 2017albertocm18100% (2)

- How prison architecture shapes human behaviorDocument8 pagesHow prison architecture shapes human behaviorEnrico MichelettiNo ratings yet

- Design 2 Town JailDocument5 pagesDesign 2 Town JailGlennson BalacanaoNo ratings yet

- Background of The Study A. HistoryDocument38 pagesBackground of The Study A. HistorynetflixNo ratings yet

- Clouds Clocks and The Study of Politics AlmondDocument35 pagesClouds Clocks and The Study of Politics AlmondAlexandre LindembergNo ratings yet

- Building Economics For Architecture PPT (F)Document54 pagesBuilding Economics For Architecture PPT (F)vaidehi vakil100% (2)

- Building Economics For Architecture PPT (F)Document54 pagesBuilding Economics For Architecture PPT (F)vaidehi vakil100% (2)

- LiteratureDocument28 pagesLiteratureLeelaprasad ChigurupalliNo ratings yet

- Redefining the Prison Milieu Through Therapeutic Community DesignDocument122 pagesRedefining the Prison Milieu Through Therapeutic Community DesignAmartya ChandranNo ratings yet

- Modular Prison: June 2016Document44 pagesModular Prison: June 2016Isabel Valentina Linares PonceNo ratings yet

- Chapter 19 - 22Document94 pagesChapter 19 - 22aisha232323chowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Climate Consensus A Multilevel Study Testing Assump - 2020 - Journal of CriminaDocument13 pagesClimate Consensus A Multilevel Study Testing Assump - 2020 - Journal of CriminaMike Angelo Vellesco CabsabaNo ratings yet

- Jail Architecture ThesisDocument8 pagesJail Architecture Thesisalisoncariassiouxfalls67% (3)

- open-prisonDocument7 pagesopen-prisonmanjunathraviheggadeNo ratings yet

- Jail Design ThesisDocument6 pagesJail Design ThesisBuySchoolPapersLasVegas100% (2)

- Bentham Deleuze and Beyond An Overview of SurveillDocument30 pagesBentham Deleuze and Beyond An Overview of SurveillnutbihariNo ratings yet

- 1939 Evolution English Prison System RadzinowiczDocument16 pages1939 Evolution English Prison System RadzinowiczJNo ratings yet

- COMBESSIE - Marking The Carceral Boundary Penal Stigma in The Long Shadow of The PrisonDocument22 pagesCOMBESSIE - Marking The Carceral Boundary Penal Stigma in The Long Shadow of The PrisonDiletta MamzelleNo ratings yet

- A Social Building? Prison Architecture and Staff-Prisoner RelationshipsDocument28 pagesA Social Building? Prison Architecture and Staff-Prisoner RelationshipsYusuf AbasNo ratings yet

- How leisure activities shape movement within prison landscapesDocument22 pagesHow leisure activities shape movement within prison landscapesAshmin BhattaraiNo ratings yet

- Architectures of Incarceration The Spatial Pains of Imprisonment Hancock2011Document19 pagesArchitectures of Incarceration The Spatial Pains of Imprisonment Hancock2011MatheNo ratings yet

- Thesis PinakafinalDocument41 pagesThesis PinakafinalJhomar Bentillo0% (1)

- Keamanan Vs PembinaanDocument24 pagesKeamanan Vs PembinaanedgaralfariziNo ratings yet

- Law Objects Spaces Others (2000)Document13 pagesLaw Objects Spaces Others (2000)perlaNo ratings yet

- Supermax prisons: Controversial facilities for highest-risk inmatesDocument22 pagesSupermax prisons: Controversial facilities for highest-risk inmatesoffyNo ratings yet

- 18 25 Ijpr - 32269Document9 pages18 25 Ijpr - 32269kontakt.mfiedorowiczNo ratings yet

- Fourth Generation PrisonDocument15 pagesFourth Generation PrisonZeeshan_Raza_37300% (1)

- The Contemporary Model of Prison Architecture Spatial Response To The Re-Socialization Programme (A.Fikfak Et Al., 2015)Document9 pagesThe Contemporary Model of Prison Architecture Spatial Response To The Re-Socialization Programme (A.Fikfak Et Al., 2015)Razi MahriNo ratings yet

- Galič2017 Article BenthamDeleuzeAndBeyondAnOvervDocument29 pagesGalič2017 Article BenthamDeleuzeAndBeyondAnOvervAlina RiosNo ratings yet

- 18.2e Spr07rapoport SMLDocument16 pages18.2e Spr07rapoport SMLAndreea Ecaterina PavelNo ratings yet

- Case Study DormitoriesDocument15 pagesCase Study DormitoriesyamadacodmNo ratings yet

- Living Precariously - Property Guardianship and The Flexible City (NeethuM)Document33 pagesLiving Precariously - Property Guardianship and The Flexible City (NeethuM)Mathew NeethuNo ratings yet

- MPP and IPT Reserach Paper FinalDocument32 pagesMPP and IPT Reserach Paper FinalInduNo ratings yet

- Canepa 2017 IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 245 052006Document11 pagesCanepa 2017 IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 245 052006Mabe CalvoNo ratings yet

- UAMERICA-.03.014Document9 pagesUAMERICA-.03.014Rimy Cruz GambaNo ratings yet

- Polipers 15 3 0067Document18 pagesPolipers 15 3 0067Parhi Likhi JahilNo ratings yet

- 001 2019 4 B PDFDocument44 pages001 2019 4 B PDFMaboya Nzuzo JackNo ratings yet

- World Archaeology: Publication Details, Including Instructions For Authors and Subscription InformationDocument16 pagesWorld Archaeology: Publication Details, Including Instructions For Authors and Subscription InformationgvavouranakisNo ratings yet

- A Robot Swarm Assisting A Human Fire-Fighter: Published VersionDocument25 pagesA Robot Swarm Assisting A Human Fire-Fighter: Published VersionFdhdFfgfsSgfsNo ratings yet

- The Prison As A Reinventive Institution Ben CreweDocument22 pagesThe Prison As A Reinventive Institution Ben CreweMatheNo ratings yet

- Annexure 2 - Common Mistakes in Prison Design (UNOPS, 2016)Document3 pagesAnnexure 2 - Common Mistakes in Prison Design (UNOPS, 2016)Razi MahriNo ratings yet

- Correctional Case StudyDocument36 pagesCorrectional Case StudyRaachel Anne CastroNo ratings yet

- The Optimal Time Window of Visual-Auditory Integration: A Reaction Time AnalysisDocument8 pagesThe Optimal Time Window of Visual-Auditory Integration: A Reaction Time Analysisaranchac21No ratings yet

- How To Build A Grill CellDocument11 pagesHow To Build A Grill CellamandaNo ratings yet

- Thomas Kuhn's Paradigm Theory and Scientific RevolutionsDocument2 pagesThomas Kuhn's Paradigm Theory and Scientific RevolutionssnejohnNo ratings yet

- The Prison Don't Talk To You About Getting Out of Prison': On Why Prisons in England and Wales Fail To Rehabilitate PrisonersDocument17 pagesThe Prison Don't Talk To You About Getting Out of Prison': On Why Prisons in England and Wales Fail To Rehabilitate PrisonersNeanderthalNo ratings yet

- 96 101 ISrael NagoreDocument6 pages96 101 ISrael NagoreDavid Mesa CedilloNo ratings yet

- Open Prison RehabilitationDocument17 pagesOpen Prison RehabilitationDeepsy Faldessai100% (1)

- Prison Design ThesisDocument8 pagesPrison Design Thesismeganespinozadallas100% (1)

- 3citation PDFDocument19 pages3citation PDFMinalu BeyeneNo ratings yet

- Prison ArchitectureDocument5 pagesPrison ArchitecturebernardoNo ratings yet

- Overview of Sense-Making Research Concepts, Methods and ResultsDocument22 pagesOverview of Sense-Making Research Concepts, Methods and ResultsGleise BrandãoNo ratings yet

- Alford (2000) - Discipline and Punish After Twenty YearsDocument23 pagesAlford (2000) - Discipline and Punish After Twenty YearsAnotherIDNo ratings yet

- Are Schools PanopticDocument11 pagesAre Schools PanopticMatea GrgurinovicNo ratings yet

- The Wild Indoors: Room-Spaces of Scientific InquiryDocument32 pagesThe Wild Indoors: Room-Spaces of Scientific InquiryEmiliano CalabazaNo ratings yet

- Challenges and Reforms in The Nigerian Prisons System PDFDocument16 pagesChallenges and Reforms in The Nigerian Prisons System PDFOlawumi OluseyeNo ratings yet

- Intergalactic SpreadingDocument35 pagesIntergalactic SpreadingDevon RoellNo ratings yet

- 4 6 Conference20 2013 IAC 3 OungrinisDocument12 pages4 6 Conference20 2013 IAC 3 OungriniskanenassssssNo ratings yet

- Reference - Page Numbers+text Matter + Image ReferencingDocument168 pagesReference - Page Numbers+text Matter + Image Referencingvaidehi vakilNo ratings yet

- Booklet - Energy Eff BuildingsDocument22 pagesBooklet - Energy Eff Buildingsarchkiranjith100% (3)

- The Little PrinceDocument2 pagesThe Little Princevaidehi vakilNo ratings yet

- The Little PrinceDocument2 pagesThe Little Princevaidehi vakilNo ratings yet

- The Little PrinceDocument2 pagesThe Little Princevaidehi vakilNo ratings yet

- Green Industry Campus Site PlanDocument6 pagesGreen Industry Campus Site Planvaidehi vakilNo ratings yet

- Reference - Page Numbers+text Matter + Image ReferencingDocument168 pagesReference - Page Numbers+text Matter + Image Referencingvaidehi vakilNo ratings yet

- Reference - Page Numbers+text Matter + Image ReferencingDocument168 pagesReference - Page Numbers+text Matter + Image Referencingvaidehi vakilNo ratings yet

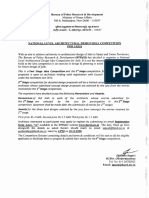

- National Level Architectural Design Idea Competition For Jails PDFDocument4 pagesNational Level Architectural Design Idea Competition For Jails PDFvaidehi vakilNo ratings yet

- Reference - Page Numbers+text Matter + Image ReferencingDocument168 pagesReference - Page Numbers+text Matter + Image Referencingvaidehi vakilNo ratings yet

- Green Industry Campus Site PlanningDocument3 pagesGreen Industry Campus Site Planningvaidehi vakilNo ratings yet

- Green Industry Campus Site PlanningDocument3 pagesGreen Industry Campus Site Planningvaidehi vakilNo ratings yet

- 0bed PDFDocument137 pages0bed PDFvaidehi vakilNo ratings yet

- Green Industry Campus Site PlanDocument6 pagesGreen Industry Campus Site Planvaidehi vakilNo ratings yet

- MUKTANGANDocument1 pageMUKTANGANvaidehi vakilNo ratings yet

- The Psychological Impact of Architectural DesignDocument44 pagesThe Psychological Impact of Architectural DesignmaygracedigolNo ratings yet

- HistoryDocument2 pagesHistoryvaidehi vakilNo ratings yet

- Architecture Thesis FormatDocument9 pagesArchitecture Thesis Formatvaidehi vakilNo ratings yet

- Theory of AnomieDocument7 pagesTheory of Anomievaidehi vakilNo ratings yet

- Book 1Document1 pageBook 1vaidehi vakilNo ratings yet

- TPJ V2 I1 VessellaDocument22 pagesTPJ V2 I1 VessellapopmirceaNo ratings yet

- Town HallDocument2 pagesTown Hallvaidehi vakilNo ratings yet

- FirmDocument19 pagesFirmvaidehi vakilNo ratings yet

- Case Study Sheets Thesis NiftDocument15 pagesCase Study Sheets Thesis NiftPrisha SinghNo ratings yet

- THESIS OrientationDocument1 pageTHESIS Orientationvaidehi vakilNo ratings yet

- SwitchesDocument8 pagesSwitchesvaidehi vakilNo ratings yet

- SAC SINGLAS Accreditation Schedule 15 Apr 10Document5 pagesSAC SINGLAS Accreditation Schedule 15 Apr 10clintjtuckerNo ratings yet

- Rguhs Dissertation PharmacyDocument6 pagesRguhs Dissertation PharmacyWhatAreTheBestPaperWritingServicesSingapore100% (1)

- Business English 2, (ML, PI, U6, C3)Document2 pagesBusiness English 2, (ML, PI, U6, C3)Ben RhysNo ratings yet

- SDRRM Earthquake Drill TemplateDocument3 pagesSDRRM Earthquake Drill TemplateChristian Bonne MarimlaNo ratings yet

- CopyofCopyofMaldeepSingh Jawanda ResumeDocument2 pagesCopyofCopyofMaldeepSingh Jawanda Resumebob nioNo ratings yet

- Dbms PracticalDocument31 pagesDbms Practicalgautamchauhan566No ratings yet

- Active and Passive Voice Chart PDFDocument1 pageActive and Passive Voice Chart PDFcastillo ceciliaNo ratings yet

- Wind Hydro 2Document6 pagesWind Hydro 2Vani TiwariNo ratings yet

- Marine Ecotourism BenefitsDocument10 pagesMarine Ecotourism Benefitsimanuel wabangNo ratings yet

- Steady State Modeling and Simulation of The Oleflex Process For Isobutane Dehydrogenation Considering Reaction NetworkDocument9 pagesSteady State Modeling and Simulation of The Oleflex Process For Isobutane Dehydrogenation Considering Reaction NetworkZangNo ratings yet

- Gorsey Bank Primary School: Mission Statement Mission StatementDocument17 pagesGorsey Bank Primary School: Mission Statement Mission StatementCreative BlogsNo ratings yet

- A Review of High School Economics Textbooks: February 2003Document27 pagesA Review of High School Economics Textbooks: February 2003Adam NowickiNo ratings yet

- 00001Document20 pages00001Maggie ZhuNo ratings yet

- Teams Training GuideDocument12 pagesTeams Training GuideImran HasanNo ratings yet

- Project On Honda Two WheelersDocument46 pagesProject On Honda Two WheelersC SHIVASANKARNo ratings yet

- (Drago) That Time I Got Reincarnated As A Slime Vol 06 (Sub Indo)Document408 pages(Drago) That Time I Got Reincarnated As A Slime Vol 06 (Sub Indo)PeppermintNo ratings yet

- Workbook. Unit 3. Exercises 5 To 9. RESPUESTASDocument3 pagesWorkbook. Unit 3. Exercises 5 To 9. RESPUESTASRosani GeraldoNo ratings yet

- NIJ Sawmark Analysis Manual for Criminal MutilationDocument49 pagesNIJ Sawmark Analysis Manual for Criminal MutilationAntonio jose Garrido carvajalinoNo ratings yet

- Gender Support Plan PDFDocument4 pagesGender Support Plan PDFGender SpectrumNo ratings yet

- Fruit-Gathering by Tagore, Rabindranath, 1861-1941Document46 pagesFruit-Gathering by Tagore, Rabindranath, 1861-1941Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Infrastructure Finance Project Design and Appraisal: Professor Robert B.H. Hauswald Kogod School of Business, AUDocument2 pagesInfrastructure Finance Project Design and Appraisal: Professor Robert B.H. Hauswald Kogod School of Business, AUAida0% (1)

- Project Report On Stock ExchangeDocument11 pagesProject Report On Stock Exchangebhawna33% (3)

- Samsung (UH5003-SEA) BN68-06750E-01ENG-0812Document2 pagesSamsung (UH5003-SEA) BN68-06750E-01ENG-0812asohas77No ratings yet

- CS Sample Paper 1Document10 pagesCS Sample Paper 1SpreadSheetsNo ratings yet