Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ten Arguments For Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now by Jaron Lanier - Review

Uploaded by

Fabián Barba0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

43 views4 pagesredes sociales

Original Title

TEN ARGUMENTS FOR DELETING YOUR SOCIAL MEDIA ACCOUNTS RIGHT NOW BY JARON LANIER – REVIEW

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentredes sociales

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

43 views4 pagesTen Arguments For Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now by Jaron Lanier - Review

Uploaded by

Fabián Barbaredes sociales

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

Book of the day

Science and nature books

TEN ARGUMENTS FOR DELETING

YOUR SOCIAL MEDIA ACCOUNTS

RIGHT NOW BY JARON LANIER –

REVIEW

Lanier was there for the creation of the internet

and is convinced that social media is toxic,

making us sadder, angrier and more isolated

Zoe Williams

Wed 30 May 2018

‘Sometimes, out of nowhere, I would get into a fight with

someone …’

Many of the ideas in Jaron Lanier’s new book start off pretty

familiar – at least, if you are active on social media. Yet in

every chapter there is a principle so elegant, so neat,

sometimes even so beautiful, that what is billed as straight

polemic becomes something much more profound.

The concept of random reinforcement, for example: addiction

fed not by reward but by never knowing whether or when the

reward will come, is well known. But Lanier puts it like

this: “The algorithm is trying to capture the perfect parameters

for manipulating a brain, while the brain, in order to seek out

deeper meaning, is changing in response to the algorithm’s

experiments … Because the stimuli from the algorithm doesn’t

mean anything, because they genuinely are random, the brain

isn’t responding to anything real, but to a fiction. That process

– of becoming hooked on an elusive mirage – isaddiction.”

The restless scrolling, the clammy self-reproach afterwards …

we could recognise that as addiction quite easily, but the

mathematical mechanism for having created it makes horrible

sense (Lanier isn’t that interested in culprits, though he finds all

of Silicon Valley pretty callow).

He wears his tech credentials lightly, as he can afford to,

having been there for the creation of the internet; he was chief

scientist of the engineering office of Internet2 and there in the

very first chat-rooms, whence he draws the conclusion that

I found the least convincing: even at its incipience, online

communication tended towards the hostile. “Sometimes, out of

nowhere, I would get into a fight with someone … It was so

weird. We’d start insulting each other, trying to score points.”

Since this all predated algorithmic manipulation, and cannot be

blamed on Facebook, he concludes that we have pack

behaviours and solitary behaviours: in a pack, we become

locked in internecine competition; on our own “we’re more free.

We’re cautious, but also more capable of joy.”

This flattens out some vital distinctions: there’s a difference

between getting together to talk to strangers about why your

celibacy is a woman’s fault, and mustering online to start the

Arab spring. Silicon Valley has a distinctive way of looking at

things: have big idea; iterate; fix; iterate again. It works well in

software design, but it’s possible that to apply to very complex

systems (like human beings), the big idea has to be refined a

little more before it’s tested.

Jaron Lanier, photographed in 1990.

Lanier explicitly addresses this in chapter eight, Social Media

Doesn’t Want You to Have Economic Dignity, as he describes

how our modern reality was seeded by that mindset, those

peculiar yes/no certainties of the web’s earliest creators. The

internet was built with no way to make or get payments, no

way to find other people you might like. “Everyone knew these

functions … would be needed. We figured it would be wiser to

let entrepreneurs fill in the blanks than to leave that task to

government … We foolishly laid the foundations for global

monopolies.”

Given the network effect – that Uber only works if everyone is

on it – a thousand flowers were never going to bloom. There’s

only room for one and it’s a Venus fly trap. The same

libertarian spirit also instituted the peculiar economics of the

internet: software had to be free, because only that way would

it be open (“everyone knew that software would eventually

become more important than law, so the prospect of a world

running on hidden code was dark and creepy”). Yet that meant

programmers wouldn’t be paid: they would create free code

and make money by solving problems later.

And so the gig economy was born, this highly skilled field

spreading its insecurity to low-skilled ones, food delivery, retail.

Neo-Marxians would have something to say about capital in all

this but Lanier emphatically doesn’t claim to have all the

answers. “Please take what you can use from me. I know I

don’t know everything,” he says in a winsome footnote.

His most dispiriting observations are those about what social

media does to politics – biased, “not towards the left or right,

but downwards”. If triggering emotions is the highest prize, and

negative emotions are easier to trigger, how could social media

not make you sad? If your consumption of content is tailored by

near limitless observations harvested about people like you,

how could your universe not collapse into the partial depiction

of reality that people like you also enjoy? How could empathy

and respect for difference thrive in this environment? Where’s

the incentive to stamp out fake accounts, fake news, paid troll

armies, dyspeptic bots?

I finished this stark but exuberant account not fearing for the

future so much as amazed the world wasn’t already even

worse.

• Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right

Now is published by Bodley Head. To order a copy for £8.49

(RRP £9.99) go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333

6846. Free UK p&p over £10, online orders only. Phone orders

min p&p of £1.99.

You might also like

- How To BreatheDocument11 pagesHow To BreatheFabián BarbaNo ratings yet

- Adam Gopnik - The Troubling Genius of G. K. ChestertonDocument20 pagesAdam Gopnik - The Troubling Genius of G. K. ChestertonFabián BarbaNo ratings yet

- Francis Fukuyama On The End of American HegemonyDocument5 pagesFrancis Fukuyama On The End of American HegemonyFabián BarbaNo ratings yet

- Alain de Botton - PHILOSOPHY IN 40 IDEAS Lessons For LifeDocument79 pagesAlain de Botton - PHILOSOPHY IN 40 IDEAS Lessons For LifeFabián BarbaNo ratings yet

- The Best Books On Philosophy and Everyday Living - Five Books Expert RecommendationsDocument19 pagesThe Best Books On Philosophy and Everyday Living - Five Books Expert RecommendationsFabián BarbaNo ratings yet

- Alain de Botton - On AnxietyDocument69 pagesAlain de Botton - On AnxietyFabián Barba100% (1)

- 'They Have Become The New Religion' - Esther Perel Says We Expect Too Much From RelationshipsDocument8 pages'They Have Become The New Religion' - Esther Perel Says We Expect Too Much From RelationshipsFabián BarbaNo ratings yet

- Naturalization Test QuestionsDocument15 pagesNaturalization Test QuestionsFabián BarbaNo ratings yet

- Alain de Bototn - Pygmalion and Your Love LifeDocument10 pagesAlain de Bototn - Pygmalion and Your Love LifeFabián BarbaNo ratings yet

- The Queen's Gambit'Document41 pagesThe Queen's Gambit'Fabián Barba100% (1)

- Alain de Botton - 22 QUESTIONS TO REIGNITE LOVEDocument14 pagesAlain de Botton - 22 QUESTIONS TO REIGNITE LOVEFabián BarbaNo ratings yet

- Robin Robertson on Books that Made Him, Influenced His WritingDocument4 pagesRobin Robertson on Books that Made Him, Influenced His WritingFabián BarbaNo ratings yet

- Alain de Botton - ON ARGUINGDocument3 pagesAlain de Botton - ON ARGUINGFabián BarbaNo ratings yet

- Alain de Botton - PHILOSOPHY IN 40 IDEAS Lessons For LifeDocument79 pagesAlain de Botton - PHILOSOPHY IN 40 IDEAS Lessons For LifeFabián BarbaNo ratings yet

- Alain de Botton - A NON-TRAGIC VIEW OF BREAKING UPDocument4 pagesAlain de Botton - A NON-TRAGIC VIEW OF BREAKING UPFabián Barba100% (1)

- The Confidence Gap For Girls - 5 Tips For Parents of Tween and Teen GirlsDocument6 pagesThe Confidence Gap For Girls - 5 Tips For Parents of Tween and Teen GirlsFabián BarbaNo ratings yet

- Alain de Botton - On Arguing More NakedlyDocument5 pagesAlain de Botton - On Arguing More NakedlyFabián BarbaNo ratings yet

- Michael Shermer - HAVE ARCHETYPE - WILL TRAVEL : THE JORDAN PETERSON PHENOMENONDocument16 pagesMichael Shermer - HAVE ARCHETYPE - WILL TRAVEL : THE JORDAN PETERSON PHENOMENONFabián Barba100% (1)

- 2008-2012 Shaye Cohn Videos CatalogueDocument5 pages2008-2012 Shaye Cohn Videos CatalogueFabián BarbaNo ratings yet

- 9 Reasons Why "Annihilation" Is One of The Best Sci-Fi Films of The 21ST CenturyDocument15 pages9 Reasons Why "Annihilation" Is One of The Best Sci-Fi Films of The 21ST CenturyFabián BarbaNo ratings yet

- The 10 Best Movie Kissing Scenes of All TimeDocument12 pagesThe 10 Best Movie Kissing Scenes of All TimeFabián BarbaNo ratings yet

- Faulkner Fables Reviews Iconic NovelsDocument13 pagesFaulkner Fables Reviews Iconic NovelsFabián BarbaNo ratings yet

- America Ferrera on Books That Inspire and EnlightenDocument5 pagesAmerica Ferrera on Books That Inspire and EnlightenFabián BarbaNo ratings yet

- 9 Reasons Why "Annihilation" Is One of The Best Sci-Fi Films of The 21ST CenturyDocument15 pages9 Reasons Why "Annihilation" Is One of The Best Sci-Fi Films of The 21ST CenturyFabián BarbaNo ratings yet

- Five Books - The Best Books On SinDocument15 pagesFive Books - The Best Books On SinFabián BarbaNo ratings yet

- Is Sugar Really Bad For You?Document13 pagesIs Sugar Really Bad For You?Fabián BarbaNo ratings yet

- 10 Movie Masterpieces You've Probably Never SeenDocument13 pages10 Movie Masterpieces You've Probably Never SeenFabián BarbaNo ratings yet

- The 10 Best Structured Movies of All TimeDocument16 pagesThe 10 Best Structured Movies of All TimeFabián BarbaNo ratings yet

- The 20 Most Beautiful Movie Scenes of All TimeDocument23 pagesThe 20 Most Beautiful Movie Scenes of All TimeFabián BarbaNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- F2022C00010Document152 pagesF2022C00010CNo ratings yet

- UI 2230SE C HQ - Rev - 3Document3 pagesUI 2230SE C HQ - Rev - 3jhvghvghjvgjhNo ratings yet

- AtardecerDocument6 pagesAtardecerfranklinNo ratings yet

- Properties of Recurisve and Recursively Enumerable Languages PDFDocument2 pagesProperties of Recurisve and Recursively Enumerable Languages PDFBelex ManNo ratings yet

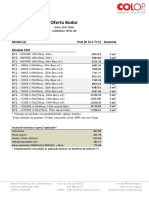

- Oferta Bodor: Model (E) Pret ( Fara TVA) Garantie Modele CO2Document3 pagesOferta Bodor: Model (E) Pret ( Fara TVA) Garantie Modele CO2Librarie PapetarieNo ratings yet

- Modern Player Telecaster® Plus (0241102Xxx) : Parts LayoutDocument4 pagesModern Player Telecaster® Plus (0241102Xxx) : Parts Layoutyongjiang luNo ratings yet

- CIO Insights Special - Medical TechnologyDocument17 pagesCIO Insights Special - Medical TechnologyCarlos Alberto Chavez Aznaran IINo ratings yet

- RQ2203056Document1 pageRQ2203056suryaNo ratings yet

- Stiffness by Definition and Direct Stiffness MethodsDocument56 pagesStiffness by Definition and Direct Stiffness MethodsSmartEngineerNo ratings yet

- .625 DIA & HEX: Outline/Installation Drawing, MODEL 3100D24Document2 pages.625 DIA & HEX: Outline/Installation Drawing, MODEL 3100D24info5280No ratings yet

- Industrial Metal Detector: Operator ManualDocument40 pagesIndustrial Metal Detector: Operator ManualINMETRO SACNo ratings yet

- How To Write An Engineering Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesHow To Write An Engineering Literature Reviewcigyofxgf100% (1)

- Share PricesDocument186 pagesShare PricesHarshul BhatiaNo ratings yet

- Lab ReportDocument3 pagesLab ReportasdadadNo ratings yet

- Snorkel TB80 1997-05Document304 pagesSnorkel TB80 1997-05Lucho AlencastroNo ratings yet

- Merge PDF Files Online. Free Service To Merge PDF - IlovepdfDocument3 pagesMerge PDF Files Online. Free Service To Merge PDF - IlovepdfAMIR RAZANo ratings yet

- Release Mode Bundle ErrorDocument11 pagesRelease Mode Bundle ErrorRaman deepNo ratings yet

- Bibler Tempest SetupDocument3 pagesBibler Tempest SetupmriffaiNo ratings yet

- Mathematical Modeling Performance Evaluation of Electro Hydraulic Servo ActuatorsDocument24 pagesMathematical Modeling Performance Evaluation of Electro Hydraulic Servo ActuatorsZyad KaramNo ratings yet

- Module 7 Polymorphism and AbstractionDocument55 pagesModule 7 Polymorphism and AbstractionJoshua Miguel NaongNo ratings yet

- QuotesDocument2 pagesQuotesKaal MaleNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2 SMN3043 A211Document4 pagesAssignment 2 SMN3043 A211ChimChim UrkNo ratings yet

- ME HoneywellVideoSystems PDFDocument157 pagesME HoneywellVideoSystems PDFSteven HungNo ratings yet

- Lectura de InglesDocument3 pagesLectura de InglesMarcelo HuatatocaNo ratings yet

- Installation and Operation Instruction: Flowcon Green 15-40 MM (1/2"-1 1/2")Document2 pagesInstallation and Operation Instruction: Flowcon Green 15-40 MM (1/2"-1 1/2")Gabriel Arriagada UsachNo ratings yet

- CC Unit4Document8 pagesCC Unit4Harsh RajputNo ratings yet

- How+to+Cobiax+ +SL+ (Slim+Line) FINALDocument4 pagesHow+to+Cobiax+ +SL+ (Slim+Line) FINALmohamed turkiNo ratings yet

- Computer Terms GlossaryDocument28 pagesComputer Terms GlossaryAngélica AlzateNo ratings yet

- Manual de Partes ZL30GDocument166 pagesManual de Partes ZL30GLeonardo Rodriguez0% (1)

- Quantitative Aptitude by SARVESH VERMADocument809 pagesQuantitative Aptitude by SARVESH VERMARajiv Ranjan0% (1)