Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chettinad House

Uploaded by

AtshayaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Chettinad House

Uploaded by

AtshayaCopyright:

Available Formats

American Journal of Sustainable Cities and Society Issue 3, Vol.

1 January 2014

Available online on http://www.rspublication.com/ajscs/ajsas.html ISSN 2319 – 7277

Eco Friendly materials used in traditional buildings of

Chettinadu in Tamil Nadu, India

S. Radhakrishnan, R. Shanthi Priya

Assistant Professor, Department of Architecture

Thiagarajar College of Engineering, Madurai

Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to study the eco friendly materials used in some traditional

buildings of Chettinadu. Building materials used in some traditional buildings are

investigated by a field study in the selected area. This study is designed to cover the

traditional buildings located at the rural area of province Aathangudi. This study researches

the ecological properties of building materials used in some traditional buildings. In the rural

areas where population increase rates are not so high, these materials provide an alternative

to the contemporary building materials and reduces energy consumption inside the buildings.

A widespread use of these materials will prevent the environmental problems that arise out of

buildings.

Key words; Ecological, traditional buildings, environment, Energy Efficiency

Introduction

In 20th century, the construction and building industry was plagued with many harmful

materials that not only poses many risks for home owners and workers, but for the

environment. Living in the 21st century, we are in the midst of moving towards a green

paradigm, away from health damaging materials. Quest for durable building materials is an

ongoing phenomenon ever since man started construction activity. Brick burning represents

one of the earliest examples of using energy to manufacture durable building materials from

the soil/earth. Firewood was the main source of energy for burning bricks. Use of metal

products represents the next energy consuming, manufactured material for the construction,

after bricks (1).

Environment and sustainability have taken the center stage in present times, as all governments

and citizens have started realizing the importance of sustaining the ecological balance, and

ensuring that life is made comfortable on this planet. The construction uses up to three million

tones of raw materials in a year and generates 20% of the solid waste. This clearly indicates the

amount of energy and materials that we spend to sustain the buildings and keep them in a good

state(2).

In response to the voices that have started getting stronger, urging builders to use natural

resources against artificial raw materials, the building community has started more usage of

such eco-friendly raw materials. It is not that these were never used before. Earlier generations

had used these materials to build strong eco-friendly homes that have lasted quite long. But the

advent of easier products, which gave the builder better profits, tilted them in favor of using

R S. Publication, rspublicationhouse@gmail.com Page 335

American Journal of Sustainable Cities and Society Issue 3, Vol. 1 January 2014

Available online on http://www.rspublication.com/ajscs/ajsas.html ISSN 2319 – 7277

such products. Rampant use of these products have resulted in creation of millions of tones of

hazardous waste, something that are non bio-degradable and are lingering on the planet,

making life difficult for the present and future generations (3).

Construction with eco-friendly building materials is becoming more popular as people try to

lessen their impact on the earth and the environment. Green building material is available in

many types and forms, and ecofriendly buildings are being seen much more often. This type of

building is very important to the future because much of the resources around the world are

being used up, and a significant amount of land is populated currently. As the world population

grows these problems will only get worse, so using eco-friendly building materials is crucial.

Staying earth friendly does not have to mean very limited choices either, because the amount

and variety of green building material has resulted in exquisite ecofriendly buildings which are

sought after. Eco-friendly building materials include products which do not harm the

environment and use a minimum of energy to produce. Some very common sustainable

materials that have started finding favor with builders, even in the urban areas are clay, sand,

rock, bamboo, straw, concrete and even wood. Use of these sustainable materials have resulted

in creation of eco-friendly homes, which not only are very healthy to live in but also are very

energy friendly and help the citizen reduce energy consumption. For example, homes insulated

with clay are very cool inside and require lesser air-conditioning (4).

In the search for sustainability, Chettinadu has been looking at modern and new materials and

technologies as much as at the indigenous practices. Despite having possessed a resourceful

repository of traditional technologies and practices, their reinventions, however, have remained

somewhat unrecognized. This stems partly from the absence of focused research as well as

sponsored or recognized programs to promote and experiment with the new possibilities of

their applications in modern building (5).

Chettinadu traditional architecture has been extensively studied, and there exists much

literature on the art and construction of the buildings. However, a greater focus has been on

recording the variety of their spatial patterns together with the architectural compositions and

appearances of buildings and their architectural details. This paper provides a general

introduction to the traditional materials of Chettinadu and examines in detail how earth

architecture has been revitalized as a sustainable approach to building. Chettinadu, the land of

wealthy Chettiars, in the South of Tamil Nadu, is known for its art, architecture and food

connoisseurs. It has nurtured, preserved and exported its local craft and culinary skills to the

world. Manufacturing exclusive colorful tile designs is a thriving industry in Aathangudi. This

study researches the ecological properties of building materials used in some traditional This

paper provides a general introduction to the traditional materials of Sri Lanka and examines in

detail how earth architecture has been revitalized as a sustainable approach to buildings of

Chettinadu in Tamil Nadu (6).

Materials used in Chettinadu Houses

The Architectural designs and the use of Eco friendly Building materials keeps the Interior

cool even when the exterior is hot. Aathangudi a small village in Sivaganga district of Tamil

Nadu continues to produce colorful hand made tiles which is a tradition started by their fore

fathers more than 100 years.

R S. Publication, rspublicationhouse@gmail.com Page 336

American Journal of Sustainable Cities and Society Issue 3, Vol. 1 January 2014

Available online on http://www.rspublication.com/ajscs/ajsas.html ISSN 2319 – 7277

Athangudi tiles, named after the place in Chettinad, Tamil Nadu, where they are manufactured,

come in myriad colors and patterns and are made by a unique process, using local soil. These

tiles are testimony to the rich cultural heritage of the Chettiars, who traded extensively in the

days of yore, especially with Burma. The Chettiars effectively adapted many an influence, to

their own brand of local craftsmanship. The designs and colors used in Athangudi tiles are still

those of a bygone era, with minimal contemporisation.

The material for each space differs in these residences. The chettiars want the best in

everything. They did trade in whole of the Southeast Asia and thus the western influence is

well predominantly seen in these palaces. Some influences are Burmese teak, Italian marble,

English steel, Japanese tiles, German lamps.

Aathangudi Flooring tiles

The flooring tiles are testimony to the rich Architectural Heritage of the old trading community

of chettiars who traveled across the seas on business. They effectively adopted many of their

foreign influences to their own brand of local craftsmanship. In aathangudi village, artisans

turn locally available sand in to colorful flowery patterned tiles. Aathangudi tiles are one such

popular handmade decorative cement floor tiles, originating from a village called Athangudi in

the Chettinad region of Tamil Nadu, the land of Chettiars. Traditionally adorning Chettinad

houses, Athangudi tiles made of sand, cement and baby jelly, are prepared through a

fascinating process with just bare hands, a clean glass and a mould. No special machines are

used and certain designs do not even need the mould. Different parts of India have their own

flooring traditions, dependent only on the available raw material, craftsmanship and the extent

of use of cultural symbols.

The mould of a design is placed on a piece of glass. This simple technique make the surface of

these tiles extremely polished. Colors, synthetic or natural, are poured into different

compartments of the mould and spread evenly.A dry mix of sand and cement is then sprinkled

on it, topped by a wet mixture of sand and cement. Once the tile is evenly laid, it is eased out

of the mould and allowed to dry overnight. The next day, it is transferred to a water tank for

curing. After two days, it is laid to dry. It is then burnt and glazed.

The making of a single Athangudi tile takes about seven to ten days, necessitating a planning

of a couple of months lead time for their procurement. A play of base colors, typically red and

yellow, with conventional flora and line-drawing designs mark the conventional style of

Athangudi tiles. The flooring generally consists of the brick bats surface and over that is the

lime mortar and the various tiles flooring ranging from aanaiadi kal, athagudi tiles to Italian

marble. Laying aathangudi tiles is as important as its production the beauty and perfection can

be achieved only with precision in masons trained in art of laying. The mixture (lime mortor or

cement mortor) up to 1.5” thickness is uniformly spread for the tiles to sit properly and the tiles

are properly packed and leveled with hand. These tiles are quite heavy and 3/4 inch thick.

Machine polish is not needed for these tiles manufactured in earthy tones and configurations.

Initially cleaned with the help of husk, the tiles can later be mopped daily with a few drops of

oil to retain the sheen. In comparison to the newer designs in the market, Aathangudi tiles are

cost effective too. The tiles come in geometric and floral designs. The tiles are generally used

only for flooring. Dark, earthy hues and black and white assemblage for borders are the

Chettinadu-tile specialties.

R S. Publication, rspublicationhouse@gmail.com Page 337

American Journal of Sustainable Cities and Society Issue 3, Vol. 1 January 2014

Available online on http://www.rspublication.com/ajscs/ajsas.html ISSN 2319 – 7277

Aathangudi complements the ethnic look beautifully, so if you have a lot of earthy hues in

your interiors, these tiles are your perfect choice.The tiles are a heritage product mostly known

and restricted to the people of Chettinadu. Aathangudi tiles are best suited for courtyards and

drawing rooms. Apart from being eco-friendly and completely natural, Aathangudi is also a

great bet if you live in hotter climes. Terracotta tiles make the room cooler in comparison to

other kinds of flooring, and their sheen gets better with usage “The tiles give an intrinsic

cooling effect. The composition of the ingredients does the trick. The tiles are best suited to

giver your house an ethnic look and they are also energy efficient,” The special features of

Aathangudi tiles are Eco – friendly and they do not reflect, radiate or conduct heat. These types

of tiles do not need machine polishing(7).

The setting hardens after a while and stays for ages. The tiles in traditional Chettinadu homes

have stayed for over 80 years without the need for any repair. These tiles do not lose their

lustre despite their age.

Fig. 1keeping the mould above the

glass plate

Fig: 2 Coloring oxides

R S. Publication, rspublicationhouse@gmail.com Page 338

American Journal of Sustainable Cities and Society Issue 3, Vol. 1 January 2014

Available online on http://www.rspublication.com/ajscs/ajsas.html ISSN 2319 – 7277

Fig: 3 Pouring coloring agents to

Create hand made designs

Fig. 4 dry mix of cement and mortar is

sprayed over the coloring oxides

Fig: 5 Wet mix of cement and lime is

sprayed over the dry mix

R S. Publication, rspublicationhouse@gmail.com Page 339

American Journal of Sustainable Cities and Society Issue 3, Vol. 1 January 2014

Available online on http://www.rspublication.com/ajscs/ajsas.html ISSN 2319 – 7277

Fig. : 6 Aathangudi tiles different

handmade designs

Fig: 7 Tiles transferred to a water tank

after curing

Wall Plastering

The wall construction is generally with the country burnt bricks. The brick size is –

8 ‟‟x3‟‟x2‟‟. Thickness of the wall – outer wall - 1 3/4‟ to 2‟, inner wall – 16‟‟ The wall

thickness is to reduce heat maintain temperature also acts as storage space. The wall plaster is

unique to chettinadu architecture. The walls of Chettinadu nagarathars‟ buildings are

embellished with „Chettinadu plaster‟ whose other names are White–„Vellai poochchu‟, Egg

plastering and Muthu Poochchu‟. Such walls were coated with several layers comprising

mixture of lime base, ground white seashells, liquid egg white, etc It consists of lime, sanghu

powder (sea shell powder)-fineness, egg white-smoothness, karupatti (a traditional sugar

jaggerry) -for friction, kadukkai( a seed of a plant) as a bonding agent. Vegetable dyes (paints

done with waste vegetables) are also used for painting pictures and murals. The plaster

involves the application of the finely ground mixture of powdered shell, lime, jaggery and

spices, including gallnut (myrobalan), to walls. This technique keeps the interior of the house

cool during the hot and humid Indian summers and lasts a lifetime. The ceiling has artistic

patterns in vegetable dye over roofing plates made of copper soldered with a special variety of

aluminum. The walls are made 1.5 ft to 3 ft wide to keep the interiors cool without the use of

any electronic equipment like the air conditioners (8). The no cementing agent was used in the

construction and the bricks are bound together with a paste of egg white, the extract of an

R S. Publication, rspublicationhouse@gmail.com Page 340

American Journal of Sustainable Cities and Society Issue 3, Vol. 1 January 2014

Available online on http://www.rspublication.com/ajscs/ajsas.html ISSN 2319 – 7277

unripe medicinal fruit found in the hills of kadukkai and lime grind. The inside walls of houses

were plastered using a combination of shell, jaggery and limestone and polished using egg

white. It gave the walls a wonderful glossy finish that no paint can replicate. “Egg plastering

was a onetime job, once it was done; there was no need to do it again. Soap and water to keep

the walls clean.

Fig: 8 Kadukkai Fig: 9 Jaggerry

Fig: 10 Gallnut

Fig: 11 Sanghu powder

R S. Publication, rspublicationhouse@gmail.com Page 341

American Journal of Sustainable Cities and Society Issue 3, Vol. 1 January 2014

Available online on http://www.rspublication.com/ajscs/ajsas.html ISSN 2319 – 7277

Fig.:12 Grinding shells

Fig.: 13 Egg plastering

Terracotta tiles in the roof

Chettiar mansions have a Gemini-like quality; they combine an eye-popping grandeur with a

very rural, earthy charm. Some of the ancient homes still have the old, handmade terracotta

roofs tiles, which are distinctively different from the new ones. The old tiles were stacked one

above the other, about eight lines thick and are small curved pieces; about one-third the breadth

of the new ones. “The tiles got their curve because tile-makers made them by shaping each one

out on their thighs,” Since the tiles for any particular roof had to be of exactly the same

measure, so that they could be laid out uniformly, it had to be produced by one man. “The roof

tiles and the egg plastering were laborious and time-consuming unfortunately, these beautiful,

unique tiles are no longer produced and the old roofs, prowled by monkeys, are beginning to

wear an unkempt look(9).

Roof

The roof is generally of the madras terrace concept. The machu concept was followed for the

courtyard roofs. Machu concept –below the roofing there is a loft of ht.3‟ to 4‟ which acts as

store and below this is the wooden beams that run through. This reduces the heat transfer

within the building.The roof tiles and the egg plasterings were laborious and time-consuming.

The combination of egg plastering, terracotta roof and floor tiles kept homes cool.

A Chettiar house took seven to ten years to build,” These materials were the best in each place.

They constructed the houses in 3 phases and so the materials also changed for every space. The

wall foundation was of hard stones called karungkal. The soil is filled up to 4ft height and left

for 3yrs in sun and rain for the soil to get set. The karungkal is raised up to the plinth(10).

4. CONCLUSION

Compared to contemporary building materials with high embodied energy, the energy

required to produce Aathangudi tiles is minimal. In addition to their energy efficient behavior

during use, these materials are completely bio-degradable. They are also more appropriate and

R S. Publication, rspublicationhouse@gmail.com Page 342

American Journal of Sustainable Cities and Society Issue 3, Vol. 1 January 2014

Available online on http://www.rspublication.com/ajscs/ajsas.html ISSN 2319 – 7277

affordable; although there is a large and growing body of empirical evidence that indigenous

building materials prove to be more advantageous, there are very few scientific studies to

support this claim. Tests on full wall assemblies will prove to be more valuable in this regard

rather than those related to the properties of single blocks/units. To summarize, traditional

building materials play an important role in contemporary architecture, first and foremost in

family homes, and to a lesser extent in public buildings. The extent to which they are used can

be explained by people's demands for high-quality materials. Traditional materials of

chettinadu reflect a deep understanding of and response to local environment and climate. The

traditional hoses of Chettinadu suited in the climate with its various type of local materials and

which create a effective environment for living of human being. There is no doubt that young

generation can take lots of good knowledgeable solution from traditional house to create a

good sustainable architecture for Chettinadu.

REFERENCES

1. Cooper, Liay & Dawson, Barry, (1998), Traditional Buildings in Architecture, Thames &

Hudson, London.Girhe , K.M (2004),

2. Architecture of Bhosalas of Nagpur- Vol.I , Bharatiya Kala Prakashan, New Delhi, India p39

3. Jain, K.B and Meenakshi (2000) Architecture of the Indian desert, AADI Centre,

Ahmedabad

4.India Kale,Yadav madav, (1924), Varhadcha itihas.Lang jon, Desai Madhavi and desai

mikki(1997),

5. Architecture and Independence, The search for Identity – India 1880 – 1980 – Oxford

University press,delhi.

6. Desai, madhavi. Traditional Architecture: House form of the Islamic community of bohras

in Gujarat, NIASA publication

7. Meir, I, A, Pearlmutter & Etzion (1995). on the microclimate behavior of two semi enclosed

attached courtyards in a hot dry region, Building and Environment,Vol. 30, 4 1995,

8. Muhaisen A.S (2006), Shading simulation of the courtyard form in different climatic

regions, Building and Environment Vol. 41 2006 pp

9. Oliver Paul (1997) – Encyclopedia of Architecture of the World, Cambridge.

10. Cooper, Liay & Dawson, Barry, (1998), Traditional Buildings in Architecture, Thames &

Hudson, London.

11. Girhe , K.M (2004), Architecture of Bhosalas of Nagpur-Vol. I, Bharatiya Kala Prakashan,

NewDelhi, India p39

R S. Publication, rspublicationhouse@gmail.com Page 343

American Journal of Sustainable Cities and Society Issue 3, Vol. 1 January 2014

Available online on http://www.rspublication.com/ajscs/ajsas.html ISSN 2319 – 7277

12. Jain, K.B and Meenakshi (2000) Architecture of theIndian desert, AADI Centre,

Ahmedabad , India Kale,Yadav madav, (1924),

13. Varhadcha itihas.Lang jon, Desai Madhavi and desai ikki(1997),Architecture and

Independence, The search for Identity – India 1880 – 1980 – oxford university press,delhi.

14.Desai, madhavi. Traditional Architecture: House form of the Islamic community of bohras

in Gujarat, NIASA publication

15.Meir, I, A, Pearlmutter & Etzion (1995). On the microclimate behavior of two semi

enclosed attached courtyards in a hot dry region, Building and Environment, Vol. 30, 4 1995,

16.Muhaisen A.S (2006), Shading simulation of the courtyard form in different climatic

regions, Building and Environment Vol. 41 2006 pp

17. Oliver Paul (1997) – Encyclopedia of Architecture of the World, Cambridge.

Caroline Paradise- Vernacular as a model for sustainable design-23rd Conference on

18. Passive and Low Energy Architecture, Geneva, Switzer Changing Vernacular Houses

around Varanasi, UP- Dr. Ravi, S. Singh

19. Mousa ahmed alhaddad and zhou tie june , A comparative study of the thermal comfort of

different building materials in sana‟a, American journal of engineering and applied sciences, 6

(1): 20-24, 2013

20.

http://www.cghearth.com/modules/newsletter/pdffiles/2677Earth_Calling_Jan_Feb_2009.pdf

21. http://www.chettinadartefacts.com/architecture.html

22. aina.wikidot.com/documentation: chettinad-egg-plaster

23.www.srmuniv.ac.in/downloads/chetinad.pdf,

24. unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0018/001887/188788e.pdf

R S. Publication, rspublicationhouse@gmail.com Page 344

You might also like

- Vernacular Architecture Ludiya Village Gujarat IndiaDocument10 pagesVernacular Architecture Ludiya Village Gujarat IndiaGeetika Agarwal100% (1)

- Vernacular Int 2 Answer KeyDocument4 pagesVernacular Int 2 Answer KeyBehemothNo ratings yet

- Chettinad HousesDocument1 pageChettinad HousesShradha AroraNo ratings yet

- Climatice Responsve Architecture-1Document10 pagesClimatice Responsve Architecture-1sparkyrubyNo ratings yet

- South India's Vernacular Architecture and Chettinad RegionDocument111 pagesSouth India's Vernacular Architecture and Chettinad RegionSachin JeevaNo ratings yet

- HGJDocument30 pagesHGJManish Bokdia0% (1)

- Chettinad Houses: Ajith Kumar M M S3 B.Arch Roll:4Document23 pagesChettinad Houses: Ajith Kumar M M S3 B.Arch Roll:4Reshma MuktharNo ratings yet

- Traditional Art &architecture OF ChettinadDocument40 pagesTraditional Art &architecture OF Chettinadnavin jolly100% (1)

- Case Study On Manpad South IndiaDocument5 pagesCase Study On Manpad South IndiaHeetarth SompuraNo ratings yet

- Vernacular Architecture 2Document23 pagesVernacular Architecture 2ChandniNo ratings yet

- Vernacular Architecture of South IndiaDocument21 pagesVernacular Architecture of South IndiaAmuthenNo ratings yet

- Rejuvenating The Vernacular Architecture of South India As The Representative of Sustainable Architecture A Case Study of Hubli KarnatakaDocument5 pagesRejuvenating The Vernacular Architecture of South India As The Representative of Sustainable Architecture A Case Study of Hubli KarnatakaVignesh MNo ratings yet

- SHARANAM Final-MergedDocument6 pagesSHARANAM Final-MergedIrene Ann TomiNo ratings yet

- East and West Vernacular-2Document16 pagesEast and West Vernacular-2goyal salesNo ratings yet

- Vernacular Architecture of TripuraDocument26 pagesVernacular Architecture of TripuraAjjit SinglaNo ratings yet

- COSTFORDDocument26 pagesCOSTFORDprabhas kar100% (1)

- Chetty 1465914035603Document38 pagesChetty 1465914035603Gokul SusindranNo ratings yet

- African Vernacular ArchitectureDocument26 pagesAfrican Vernacular ArchitectureAmit Kumar YadavNo ratings yet

- Western Influences on Indian ArchitectureDocument14 pagesWestern Influences on Indian ArchitectureSachin JeevaNo ratings yet

- ChetinadDocument14 pagesChetinadNidz Reddy100% (1)

- Kutch ArchitectureDocument16 pagesKutch ArchitectureNehaKharbNo ratings yet

- Vernacular ArchitectureDocument16 pagesVernacular ArchitectureHasita KrovvidiNo ratings yet

- Vernacular Architecture of KarnatakaDocument4 pagesVernacular Architecture of KarnatakaPinky Yadav50% (2)

- North - Arch. of KashmirDocument22 pagesNorth - Arch. of KashmirV.K.Jeevan KumarNo ratings yet

- Vernacular Architecture of Kullu: Submitted By: Jagriti 13622Document25 pagesVernacular Architecture of Kullu: Submitted By: Jagriti 13622Shefali GoswamiNo ratings yet

- Analyzing Values in Built Heritage of Chettinadu RegionDocument12 pagesAnalyzing Values in Built Heritage of Chettinadu RegionAtshayaNo ratings yet

- Dajji Dewari Kashmir Final 1Document7 pagesDajji Dewari Kashmir Final 1Mehar Saran KaurNo ratings yet

- West India Vernacular ArchitectureDocument42 pagesWest India Vernacular ArchitectureMahima ChawlaNo ratings yet

- Vernacular Architecture Ar 8002 Unit I and IiDocument44 pagesVernacular Architecture Ar 8002 Unit I and IiJennifer PaulNo ratings yet

- Kath-khuni Architecture as Sustainable Humane HabitatDocument18 pagesKath-khuni Architecture as Sustainable Humane HabitatGarimaNo ratings yet

- Patwa HaveliDocument8 pagesPatwa HaveliPalak Bajaj100% (1)

- An Out Line of Vernacular Architecture oDocument12 pagesAn Out Line of Vernacular Architecture oAtchaya subramanianNo ratings yet

- Bhunga HousesDocument16 pagesBhunga HousesVidhi Kothari100% (1)

- Finl Vernaculr KirtiDocument23 pagesFinl Vernaculr KirtiKirti PandeyNo ratings yet

- Flood Resistant Structures: AssamDocument12 pagesFlood Resistant Structures: AssamPOOJA P 17BARC042100% (1)

- Unit 4 TamilnaduDocument12 pagesUnit 4 TamilnaduBhuvana100% (1)

- Culture's Influence on the Evolution of Pol Houses in AhmedabadDocument16 pagesCulture's Influence on the Evolution of Pol Houses in AhmedabadSajalSaketNo ratings yet

- Dokras Wada Part IIIDocument17 pagesDokras Wada Part IIIUday DokrasNo ratings yet

- Keralaarchitecture 151005035817 Lva1 App6891Document42 pagesKeralaarchitecture 151005035817 Lva1 App6891atif ali khan100% (2)

- Padmanabhampurampalace 100211074034 Phpapp01Document13 pagesPadmanabhampurampalace 100211074034 Phpapp01surekaNo ratings yet

- Non - Conventional Architecture - Chettinad HouseDocument16 pagesNon - Conventional Architecture - Chettinad HouseGayathri kalkiNo ratings yet

- Architecture of Marikal PDFDocument14 pagesArchitecture of Marikal PDFKoushali BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- Vernacular ArchitectureDocument25 pagesVernacular ArchitectureWaDan AbDullah KHanNo ratings yet

- Hill Architecture of Kashmir ValleyDocument20 pagesHill Architecture of Kashmir ValleyNishant Sharma100% (1)

- Unit 3Document39 pagesUnit 3SivaRaman100% (1)

- Nari GandhiDocument16 pagesNari GandhiSanjana BhandiwadNo ratings yet

- Chettinad HousesDocument20 pagesChettinad HousesManish Bokdia100% (2)

- Jaipur Heritage-PreservationDocument54 pagesJaipur Heritage-Preservationtabbybatra1331No ratings yet

- Indigenous architecture of hot-dry desert climateDocument3 pagesIndigenous architecture of hot-dry desert climateNagpal ChetanNo ratings yet

- Pristine Settlements of Toda at Nilgiris, South India: Design GuidelinesDocument5 pagesPristine Settlements of Toda at Nilgiris, South India: Design GuidelinesVarunNo ratings yet

- An Assessment of Flood in KuttanaduDocument8 pagesAn Assessment of Flood in KuttanaduSreelakshmiNo ratings yet

- CHETTINAD HERITAGE CONSERVATIONDocument5 pagesCHETTINAD HERITAGE CONSERVATIONras rasikNo ratings yet

- Dissertation: Traditional Construction Material Used in RajasthanDocument56 pagesDissertation: Traditional Construction Material Used in Rajasthankomal sharmaNo ratings yet

- CHETTIARSDocument27 pagesCHETTIARSRahul RoyNo ratings yet

- Endangered Chettinad Cultural HeritageDocument3 pagesEndangered Chettinad Cultural HeritageManish BokdiaNo ratings yet

- Laurie Baker WorksDocument8 pagesLaurie Baker WorksPreethi NandagopalNo ratings yet

- The Vernacular Architecture of RajasthanDocument8 pagesThe Vernacular Architecture of RajasthanGaurav PatilNo ratings yet

- Mud Architecture: I J I R S E TDocument6 pagesMud Architecture: I J I R S E TJazzNo ratings yet

- Identification of Local & Sustainable Building Methods For Residences in KeralaDocument9 pagesIdentification of Local & Sustainable Building Methods For Residences in KeralaathulyaNo ratings yet

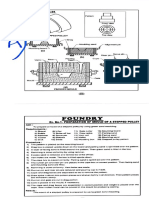

- Foundry: Ex. Mo.1. Preparation of Mould of A Stepped PulleyDocument4 pagesFoundry: Ex. Mo.1. Preparation of Mould of A Stepped PulleyAtshayaNo ratings yet

- Evolutionary Algorithms: Presented by Muhannad HarrimDocument44 pagesEvolutionary Algorithms: Presented by Muhannad Harrimjaved765No ratings yet

- Ecomimicry Inspired Innovations from NatureDocument35 pagesEcomimicry Inspired Innovations from NatureAtshayaNo ratings yet

- Evolutionary Algorithm GuideDocument33 pagesEvolutionary Algorithm GuideArka ChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- Evolutionary Algorithm GuideDocument33 pagesEvolutionary Algorithm GuideArka ChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- Evolutionary Algorithms: Presented by Muhannad HarrimDocument44 pagesEvolutionary Algorithms: Presented by Muhannad Harrimjaved765No ratings yet

- Kanchan - 1Document5 pagesKanchan - 1AtshayaNo ratings yet

- Foundry: Ex. Mo.1. Preparation of Mould of A Stepped PulleyDocument4 pagesFoundry: Ex. Mo.1. Preparation of Mould of A Stepped PulleyAtshayaNo ratings yet

- Dr. T Presents : Evolutionary ComputingDocument169 pagesDr. T Presents : Evolutionary ComputingAtshayaNo ratings yet

- Interactive ground floor plan for Ocean EngineeringDocument1 pageInteractive ground floor plan for Ocean EngineeringAtshayaNo ratings yet

- M.Arch Online ScheduleDocument1 pageM.Arch Online ScheduleAtshayaNo ratings yet

- Bio Tech - SF PDFDocument1 pageBio Tech - SF PDFAtshayaNo ratings yet

- Sustainability and The Architectural HistoryDocument12 pagesSustainability and The Architectural HistoryAtshayaNo ratings yet

- M.Arch PDFDocument25 pagesM.Arch PDFPraba KuttyNo ratings yet

- Ocean Eng - FF PDFDocument1 pageOcean Eng - FF PDFAtshayaNo ratings yet

- Ocean Eng - SFDocument1 pageOcean Eng - SFAtshayaNo ratings yet

- M ARCH Services in High Rise Buildings - Model Exam-2 PDFDocument1 pageM ARCH Services in High Rise Buildings - Model Exam-2 PDFAtshayaNo ratings yet

- Everything You Need to Know About Building Management Systems (BMSDocument1 pageEverything You Need to Know About Building Management Systems (BMSAtshayaNo ratings yet

- UNIT IINTRODUCTION PDF Sub PDFDocument13 pagesUNIT IINTRODUCTION PDF Sub PDFAtshayaNo ratings yet

- Bio Tech - FFDocument1 pageBio Tech - FFAtshayaNo ratings yet

- Bio Tech - GFDocument1 pageBio Tech - GFAtshayaNo ratings yet

- Plumbing System in High Rise BuildingDocument7 pagesPlumbing System in High Rise BuildingAtshayaNo ratings yet

- BMS-Automation & Energy ManagementDocument7 pagesBMS-Automation & Energy ManagementAtshayaNo ratings yet

- UNIT II Sub Pres PDFDocument13 pagesUNIT II Sub Pres PDFAtshayaNo ratings yet

- UNIT IINTRODUCTION PDF Sub PDFDocument13 pagesUNIT IINTRODUCTION PDF Sub PDFAtshayaNo ratings yet

- Embodied Energy of Building MaterialsDocument11 pagesEmbodied Energy of Building MaterialsAtshayaNo ratings yet

- UNIT V Sub Pres PDFDocument7 pagesUNIT V Sub Pres PDFAtshayaNo ratings yet

- Embodied Energy of Building MaterialsDocument11 pagesEmbodied Energy of Building MaterialsAtshayaNo ratings yet

- UNIT II Sub Pres PDFDocument13 pagesUNIT II Sub Pres PDFAtshayaNo ratings yet

- UNIT V Sub Pres PDFDocument7 pagesUNIT V Sub Pres PDFAtshayaNo ratings yet

- Supplementary Manual To The WSAA Sewerage Pumping Station Code (WSA 04-2005:2.1)Document57 pagesSupplementary Manual To The WSAA Sewerage Pumping Station Code (WSA 04-2005:2.1)jituplanojrNo ratings yet

- En 10139Document1 pageEn 10139Alex LacerdaNo ratings yet

- EXHAUST System - LEBW4970-06 PDFDocument42 pagesEXHAUST System - LEBW4970-06 PDFdimaomarNo ratings yet

- 7856.n1.40703.03-Ofgi 4070Document2 pages7856.n1.40703.03-Ofgi 4070Claudio Valencia MarínNo ratings yet

- Rigid Pavement Design: 29.1.1 Modulus of Sub-Grade ReactionDocument9 pagesRigid Pavement Design: 29.1.1 Modulus of Sub-Grade Reactionnageshkumarcs100% (1)

- Method Statement For Cement Wall Plastering-1Document8 pagesMethod Statement For Cement Wall Plastering-1md_rehan_2No ratings yet

- Optimum Design-1Document11 pagesOptimum Design-1056 Sania AnjumNo ratings yet

- 1 d4 Off ScribbleDocument47 pages1 d4 Off ScribbleTarun rathodNo ratings yet

- r0 Design and Gad Submission Dhoot Builders - 20.03.2024Document26 pagesr0 Design and Gad Submission Dhoot Builders - 20.03.2024sujit naikwadiNo ratings yet

- CASE STUDY - BIHAR MUSEUM (National)Document9 pagesCASE STUDY - BIHAR MUSEUM (National)sakshi meher75% (4)

- MG HG ReplacementDocument16 pagesMG HG ReplacementChrisBeller45No ratings yet

- Sydney PDFDocument8 pagesSydney PDFMouy PhonThornNo ratings yet

- Es 9-54 Fastener Installation and Torque ValuesDocument33 pagesEs 9-54 Fastener Installation and Torque ValuesCarlosFernandoMondragonDominguezNo ratings yet

- Services PPT Dupont Plaza Hotel and CasinoDocument20 pagesServices PPT Dupont Plaza Hotel and CasinoShivangi Shankar100% (1)

- Production Service HookupDocument40 pagesProduction Service Hookupray mojicaNo ratings yet

- Detail 2006 10Document28 pagesDetail 2006 10filipgavrilNo ratings yet

- Oil-Fuel SeparatorDocument24 pagesOil-Fuel SeparatorSiva SubramaniyanNo ratings yet

- A380 WING RIB Feet CrackingDocument9 pagesA380 WING RIB Feet CrackinggygjhkjnlNo ratings yet

- Failure AnalysisDocument29 pagesFailure AnalysisreddyNo ratings yet

- Plastic Vessel Pressure DesignDocument12 pagesPlastic Vessel Pressure Designr1p2100% (1)

- Catalogo CH 570Document848 pagesCatalogo CH 570norman100% (6)

- Chapter 9 Foundation Spread FootingsDocument41 pagesChapter 9 Foundation Spread FootingsYsabelle TagarumaNo ratings yet

- SP 2269Document31 pagesSP 2269Vijayakumar AllimuthuNo ratings yet

- CHEERS Project Profile & AnalysisDocument32 pagesCHEERS Project Profile & AnalysisMr. ManaloNo ratings yet

- 132-33 KV Substation SpecificationDocument280 pages132-33 KV Substation SpecificationMohsin ElgondiNo ratings yet

- Article For Review-Safety ManagementDocument11 pagesArticle For Review-Safety ManagementKarl Anne DomingoNo ratings yet

- 16mo3 - EN NOOODocument2 pages16mo3 - EN NOOOM Refaat FathNo ratings yet

- Materials Engineer Test ReviewerDocument37 pagesMaterials Engineer Test ReviewerRam Gacot100% (3)

- The 1988 UbcDocument951 pagesThe 1988 UbcChristian SesoNo ratings yet

- ScrutinyDocument11 pagesScrutinySanjay NautiyalNo ratings yet

- David Baldacci Best Reading Order Book List With Summaries: Best Reading OrderFrom EverandDavid Baldacci Best Reading Order Book List With Summaries: Best Reading OrderNo ratings yet

- Christian Apologetics: An Anthology of Primary SourcesFrom EverandChristian Apologetics: An Anthology of Primary SourcesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- 71 Ways to Practice English Writing: Tips for ESL/EFL LearnersFrom Everand71 Ways to Practice English Writing: Tips for ESL/EFL LearnersRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Great Short Books: A Year of Reading—BrieflyFrom EverandGreat Short Books: A Year of Reading—BrieflyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (10)

- English Vocabulary Masterclass for TOEFL, TOEIC, IELTS and CELPIP: Master 1000+ Essential Words, Phrases, Idioms & MoreFrom EverandEnglish Vocabulary Masterclass for TOEFL, TOEIC, IELTS and CELPIP: Master 1000+ Essential Words, Phrases, Idioms & MoreRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Colleen Hoover The Best Romance Books Complete Romance Read ListFrom EverandColleen Hoover The Best Romance Books Complete Romance Read ListNo ratings yet

- Jack Reacher Reading Order: The Complete Lee Child’s Reading List Of Jack Reacher SeriesFrom EverandJack Reacher Reading Order: The Complete Lee Child’s Reading List Of Jack Reacher SeriesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- Great Short Books: A Year of Reading—BrieflyFrom EverandGreat Short Books: A Year of Reading—BrieflyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Help! I'm In Treble! A Child's Introduction to Music - Music Book for Beginners | Children's Musical Instruction & StudyFrom EverandHelp! I'm In Treble! A Child's Introduction to Music - Music Book for Beginners | Children's Musical Instruction & StudyNo ratings yet

- 71 Ways to Practice Speaking English: Tips for ESL/EFL LearnersFrom Everand71 Ways to Practice Speaking English: Tips for ESL/EFL LearnersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Bibliography on the Fatigue of Materials, Components and Structures: Volume 4From EverandBibliography on the Fatigue of Materials, Components and Structures: Volume 4No ratings yet

- Seeds! Watching a Seed Grow Into a Plants, Botany for Kids - Children's Agriculture BooksFrom EverandSeeds! Watching a Seed Grow Into a Plants, Botany for Kids - Children's Agriculture BooksNo ratings yet

- Memory of the World: The treasures that record our history from 1700 BC to the present dayFrom EverandMemory of the World: The treasures that record our history from 1700 BC to the present dayRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Chronology for Kids - Understanding Time and Timelines | Timelines for Kids | 3rd Grade Social StudiesFrom EverandChronology for Kids - Understanding Time and Timelines | Timelines for Kids | 3rd Grade Social StudiesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Seven Steps to Great LeadershipFrom EverandSeven Steps to Great LeadershipRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Patricia Cornwell Reading Order: Kay Scarpetta In Order, the complete Kay Scarpetta Series In Order Book GuideFrom EverandPatricia Cornwell Reading Order: Kay Scarpetta In Order, the complete Kay Scarpetta Series In Order Book GuideRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- My Mini Concert - Musical Instruments for Kids - Music Book for Beginners | Children's Musical InstrumentsFrom EverandMy Mini Concert - Musical Instruments for Kids - Music Book for Beginners | Children's Musical InstrumentsNo ratings yet

- Sources of Classical Literature: Briefly presenting over 1000 worksFrom EverandSources of Classical Literature: Briefly presenting over 1000 worksNo ratings yet

- Myanmar (Burma) since the 1988 Uprising: A Select Bibliography, 4th editionFrom EverandMyanmar (Burma) since the 1988 Uprising: A Select Bibliography, 4th editionNo ratings yet

- The Pianist's Bookshelf, Second Edition: A Practical Guide to Books, Videos, and Other ResourcesFrom EverandThe Pianist's Bookshelf, Second Edition: A Practical Guide to Books, Videos, and Other ResourcesNo ratings yet