Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 201.158.189.66 On Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:47:16 UTC

Uploaded by

Jesús TapiaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 201.158.189.66 On Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:47:16 UTC

Uploaded by

Jesús TapiaCopyright:

Available Formats

The Story of ORCH5, or, the Classical Ghost in the Hip-Hop Machine

Author(s): Robert Fink

Source: Popular Music , Oct., 2005, Vol. 24, No. 3, These Magic Moments (Oct., 2005), pp.

339-356

Published by: Cambridge University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3877522

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to Popular Music

This content downloaded from

201.158.189.66 on Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:47:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Popular Music (2005) Volume 24/3. Copyright @ 2005 Cambridge University Press, pp. 339-356

doi:10.1017/S0261143005000553 Printed in the United Kingdom

The story of ORCH5, or, the

classical ghost in the hip-hop

machine

ROBERT FINK

Abstract

Perhaps the first digital sample to become well known within popular music was actually a piece

of Western art music, the fragment of Stravinsky's Firebird captured within the Fairlight

Computer Musical Instrument, the first digital 'sampler', as 'ORCH5'. This loud orchestral

attack was made famous by Bronx DJ Afrika Bambaataa, who incorporated the sound into his

seminal 1982 dance track, 'Planet Rock'. Analysis of Kraftwerk's 'Trans Europe Express', also

sampled for 'Planet Rock', provides an interpretive context for Bambaataa's use of ORCH5, as

well as the hundreds of songs that deliberately sought to copy its sound. Kraftwerk's concerns

about the decadence of European culture and art music were not fully shared by users of ORCH5

in New York City; its sound first became part of an ongoing Afro-futurist musical project, and

by 1985 was fully naturalised within the hip-hop world, no more 'classical' than the sound of

scratching vinyl. To trace the early popular history of ORCH5's distinctive effect, so crucial for

early hip-hop, electro, and Detroit techno, is to begin to tell the post-canonic story of Western art

music.

Germany has a very long classical music tradition.

(Ralf Hiitter of Kraftwerk, 2004)

The DJ plays your favourite blasts,

Takes you back to the past -

Music's magic! (poof)

(Afrika Bambaataa, 'Planet Rock', 1982)

'Tomorrow's Music Today'

(Advertising slogan for the Fairlight Computer Music Instrument, ca. 19831)

Prelude: The Great Liberation, or, is there life after death?

The 'death of (European) classical music' may seem a somewhat tired, even irrelevant

trope with which to start an essay in the present journal - which is, after all, devoted

to the study around the globe of (clearly quite healthy) popular music. Certainly there

is no consensus among critics and scholars as to the survival of the literate, 'cultivated'

tradition of Western music as the twenty-first century advances, and even if there

were, why should anyone doing popular music studies care, other than to register a

small but real sense of satisfaction at avoiding what looks like a losing horse in the

music history championship stakes? It oughtn't to matter much to the study of

popular music whether, as partisans within the classical world indignantly retort,

audiences for the symphony and opera are actually holding steady; whether, as

339

This content downloaded from

201.158.189.66 on Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:47:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

340 Robert Fink

classical record label executives report, the latest crossover hit has t

stabilised their bottom line; whether, as contemporary classical com

hasten to assure us, they really do care if you listen.2

And indeed, these material-cultural issues are of little import for the

that follows. What cannot be ignored is the fundamental epistemological

besets Western music as it heads into what more than one commentator has labelled

its 'post-classical' era (Horowitz 1995).3 I have argued elsewhere that the incipient

collapse of our paradigmatic cultural hierarchy of music, along with its canon of

'classical' masterworks, was easily discernable as European musical culture careened

toward the millennium, ushering in a fundamental (and salutary) 'de-centring' of its

musical world-view. As I pointed out then, under the somewhat whimsical rubric

'Why You Need a Musicologist to Listen to Beck', one of the most disorienting

consequences, ripe for scholarly study, was the collapse of the classical canon's

segregating function, its ability not only to keep the 'low' music out, but to keep the

high-art classical music of the European past safely walled in, where mass culture

could mostly ignore it, occasionally gesturing at it from afar, whether to resist ('Rol

Over, Beethoven'), parody ('Bohemian Rhapsody'), or appropriate ('A Whiter Shade

of Pale') its snob value, along with (at times) its sounds and structures (Fink 1998,

pp. 142-56).

The story of ORCH5 is, accordingly, set within the de-centred world of Western

music during the slow twilight of its classical canon. It will lead us from Diisseldorf to

Detroit, and from avant-garde German modernism to Afro-centric hip-hop. It is a

story of technology, of machines fetishised, appropriated, mistrusted, misused. It also

turns out to be a ghost story, the story of what happens to a particular fragment of

classical music after it stops being classical, when it is not quite dead, but, as Buddhists

might put it, in the bardo realm halfway between death and new life. The classic

description of the bardo appears in what is popularly known as 'The Tibetan Book of

the Dead': the actual title, though, is (roughly) the Book of the Great Liberation, through

Hearing, in the Bardo Realm. This is, accordingly, a story of death - but there will also

be an attempt at post-canonic hearing, and at least some intimation of the great

liberation(s) to come. Reincarnation, what Pythagoras called 'the transmigration of

souls', is not an exotic, foreign concept; it has always been deeply woven into the

European musical consciousness, brought to us by the same mind to which we

mythically attribute the foundational observations of Western music theory. The

story I have to tell is of musical reincarnation, of the transmigration of tones. It is a tale

of the afterlife of 'classical music', transmigrated through digital technology, the

commodity form, and myriad fortunate cultural misreadings of a single famous

chord.

It is the story of the classical ghost in the hip-hop machine.

Kastchei the (Digitised) Immortal

ORCH5 is a low-resolution, eight-bit digital sample, a very early one, perhaps the first

one to become famous. It was digitised around 1979 by David Vorhaus, a computer

programmer and classically trained electronic musician. The file appeared on Disk 17

of the 25-or-so eight-inch floppy disks that made up the sampled sound library

shipped with each very expensive Fairlight Computer Musical Instrument. (In the

United States, the going rate for a Fairlight Model IIx in the early 1980s was over

$25,000; see Holmes 1996-9.) The Fairlight CMI, originally cobbled together in 1979 by

This content downloaded from

201.158.189.66 on Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:47:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The story of ORCH5 341

two Australian inventors out of the ruins of the Quasar, a failed analogue modelling

synthesizer, was the first commercially available electronic musical instrument that,

in addition to generating musical sounds through analogue/digital synthesis, gave its

owner the ability to sample pre-existing sounds into digital memory, process them,

and play them back through a keyboard. It is thus the single evolutionary starting

point for an entire phylum of ubiquitous (and much cheaper) digital samplers,

including the Akai S-series (1984) and the Ensoniq Mirage (1985), so crucial to the rise

of sample-based hip-hop.

Kim Ryrie and Peter Vogel, the inventors of the Fairlight, considered its digital

sampling capability a technical hack, a clever shortcut on the way to their ultimate

audio workstation. Digital conversion allowed them to implement complex tools for

sound synthesis while bypassing processor-intensive tasks too difficult for its parallel

pair of primitive Motorola 8800-series microprocessors. Nobody really took sampling

per se seriously at first: company apocrypha identifies the first sound sampled for

melodic playback as the barking of an employee's dog. But early Fairlight users

singled out the CMI's sampling power as a key differentiator, and soon company

brochures touted the system's ability 'to incorporate literally ANY type of sound - not

only classical and modern instruments but sounds of the world; sounds reflecting the

full spectrum of life, from the subtlety and force of nature to the sounds of civilisation

and synthesis' (Fairlight 1983). This is why Fairlights began shipping with floppy

disks full of sampled sounds. Many of these soon-to-be famous samples had been

somewhat casually appropriated by an adventurous first generation of users.

Vorhaus, an orchestral double-bass player as well as founder, with members of the

BBC Radiophonic workshop, of the British electronic 'pop' group White Noise, was a

typical early adopter of the Fairlight; he brought his classical training very much to

bear as he contributed to what would become the standard set of samples included

with every new CMI.

ORCH5 was just one of a series of ORCH samples that Vorhaus and others culled

from (one assumes) a quick troll through their classical record collections. The

orchestral samples provided with the Fairlight feature short snippets of full-orchestra

chords from the symphonic literature, usually just a single attack, often pitched

(TRIAD), but also percussion-dominated (ORCHFZ1), occasionally looped to pro-

vide a pulsating pattern capable of sustained use (ORCH2). ORCH5, the most famous

of these, is almost certainly sampled from Igor Stravinsky's ballet The Firebird; as I

have verified myself using digital sound processing, the loud chord that opens the

'Infernal Dance of All the Subjects of Kastchei', pitched down a minor sixth (and also

slowed down, since digital technology did not in 1979 yet allow independent manipu-

lation of frequency and sampling rate), can be made to match with tolerable precision

an iteration of ORCH5 on the pitch C4 easily obtainable from several internet websites

devoted to the mysteries of the Fairlight CMI.4 It's not hard to fathom why Vorhaus

picked this spot: the piece is famous, the sound is impressive, and, crucially, in every

one of Stravinsky's three suites from the ballet, this forceful blast is neatly isolated at

the beginning of a movement, framed by complete silence on one side and only a low

pianissimo rumble on the other (see Example 1).

Here, as classical music steps into the bardo realm, is where a musicological ear

is of use; the Russian provenance of ORCH5 gives rise to some quite strikingly ironic

overtones, mostly pitched at frequencies that require at least some music-historical

training to perceive. The sampled chord in question was notated in 1909, quite close

(as Horowitz 2005 argues) to the absolute apogee of classical music culture in the

This content downloaded from

201.158.189.66 on Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:47:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

342 Robert Fink

. . .... ... ............

"xORCH 5"

... .....

.............. .........

TV

. ..... . ....... P

=-ui~rr-n=

......

CAt:

. ...-I..............................

. . ..... ......

. ......

J w c'

Example 1. Stravin

West. It is the

fascinated with t

generations; and

digital sample t

music', happene

before his own

often wished in

he proposed to

The Firebird wa

success simply go

argues, Stravinsk

first, in 1919, t

re-establish cop

critic Olin Dow

composer had b

poser so increas

attempting to e

2000, pp. 230-49

Vorhaus appear

tion, not the 19

This content downloaded from

201.158.189.66 on Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:47:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The story of ORCH5 343

analogue-to-digital conversion process produced a brittle, grainy sample whose

frequency spectrum is shifted noticeably towards the upper registers of the orchestra.5

This has the paradoxical effect of making the sample sound both 'old' (because its

low fidelity cannot capture the full range of the orchestra, as in the pre-LP era), and

'new' (because the sound itself is noticeably devoid of romantic lushness). As it

happens, Stravinsky's successive re-orchestrations of the ORCH5 chord had a similar

bass-filtering (and thus modernising) effect: by 1919, in search of a dryer, lighter

sound, he had replaced two of the harps with the ringing sound of the piano's top

octaves, asked for the bass drum to be struck with a leather mallet, and instructed the

timpanist to use his hardest wooden stick. In the final 1945 version, his remixing went

even further, with a xylophone glissando and a new snare drum roll producing a

distinctively dry, crackling spray of dissonant upper partials. In effect, Stravinsky had

been down-sampling his younger self long before Vorhaus captured the dried-up

digital remains of Kastchei the Immortal on an eight-inch floppy disk.

How much of the original juice could possibly be left?

Stravinsky joins the Zulu Nation

ORCH5 led a quiet life for about two years. Only wealthy or well-connected pop

musicians had access to a Fairlight CMI, and the complexities of programming its

intricate waveform editor and its quirky music sequencing module (the famous 'Page

R'; see Holmes 1996-9) made harnessing Fairlight samples the province of methodical

experimenters with big budgets, lots of time, and notably progressive tastes. When

ORCH5 showed up in their work, the temporal and acoustic distance it encoded, the

grainy, slowed-down, 'half-dead' sound of a classical orchestra taken out of context,

often worked towards a kind of Orientalist exoticism. This is how Kate Bush used the

sample in the title track of her 1982 album The Dreaming: blasts of ORCH5 under heavy

reverb lance through the chanting, didgeridoos, and pounding drums of the song's

fadeout, the whole a spooky musical depiction of Australia's aboriginal 'dreamtime'

under attack by industrial modernity (' "Bang!" goes another kanga/On the bonnet

of the van ...'). Other early Fairlight owners, especially in Europe, used its sam-

pling capability to reactivate the subversive agenda of the 'historical avant-garde'

(Huyssen 1986) within popular dance music. Presumably this is why Anne Dudley

released her essays in Fairlight-enabled sound collage - where ORCH5, jostling for

space with the sound of chainsaws, breaking glass, and motorcycle engines, func-

tions as pure alienation-effect - under the retro-Futurist moniker 'The Art of Noise'.

(Dudley and Trevor Horn, her main collaborator, may well have known first-hand

from Vorhaus whence the sample came; in any case, the final moments of their 1984 hit

single 'Close (to the Edit)' wittily close the loop, mixing ORCH5 back into a congeries

of sampled orchestral blasts from Stravinsky's Rite of Spring.)

But in late 1982, Stravinsky and Vorhaus started hanging with a blacker, funkier

crew; ORCH5 joined the Zulu Nation. 'Planet Rock', an interracial collaboration

between pioneering hip-hop DJ Afrika Bambaataa and dance producer Arthur Baker,

was a massive R&B hit; it remapped the sound and practice of hip-hop, defined

several new musical genres, and spawned hundreds of imitations. Bambaataa himself

immodestly claims at least six genres of dance music were born when 'Planet Rock'

launched the style that he called 'Electro-Funk', and which would be known simply

as 'electro': 'the Miami Bass to the Latin freestyle, Latin hip-hop, to the house

music, hip-house, techno' (Fricke & Ahearn 2002, p. 315). Baker agrees: 'I knew [it was

This content downloaded from

201.158.189.66 on Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:47:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

344 Robert Fink

a historic track] before we even mixed it. I knew before there was even a

went home the night we cut the track and brought the tape home and I said t

at the time, "We've just made musical history"' (Brewster and Brou

pp. 242-3).

Bambaataa and Baker didn't just make hip-hop history; they also made world-

famous a particular orchestration of ORCH5. African-American musicians have been

asking other musicians to 'hit them' for decades; but 'Planet Rock' is the first time that

the hit came down in the form of a digital sample. Baker (1999) claims technical

priority, since Bambaataa knew the beats and breaks he wanted, but 'didn't know

about the studio', and since it was through Baker's industry connections that the

'Planet Rock' sessions took place in a fully-equipped New York recording space - the

kind that had an expensive Fairlight CMI just sitting around ready to transform

African-American popular music.

On one level, 'Planet Rock' was pure serendipity. Bambaataa and Baker had no

idea how to use the machine, no one to show them, nor any time to learn:

It was pretty quick to make because we didn't have much money. We'd get downtime - night

time - sessions. The guy who owned the studio gave us a deal. Maybe it was three all night

sessions. We did all the music in one session and a bit of the rap. Then we did the rap. Then we

mixed it. (Baker 1999)

John Robie, the keyboard player, hacked around until he figured out how to trigger

eight versions of ORCH5 simultaneously, using both hands, on the pitches of a

root-position minor triad. The Fairlight IIx, with its eight independently operating

audio cards - and which in all other respects seemed to Baker and Bambaataa an

un-programmable '$100,000 of useless space thing' - responded beautifully (Baker

1999).6 A hip-hop cliche was born.

But one might ask why the first sampled hit should be so dark, portentous, and

classical-sounding. Why did Robie filter Stravinsky-by-way-of-Vorhaus through that

brooding minor triad? Could it have something to do with the dark synthesizer tune,

full of Germanic Weltschmerz, that he knew he would be asked to play a few moments

later?

Eleganz und Dekadenz, or, Kraftwerk throws classical music from

the train

That tune is, as everyone knows, a quotation from Kraftwerk's 1977 non-hit, 'Trans

Europe Express'. Using Kraftwerk (not to mention 'The Mexican', a transcription by

British prog-rockers Babe Ruth of Ennio Morricone's big tune from For a Few Dollars

More) was an attempt to capture in the studio the unpredictable range of Bambaataa's

live DJ-ing. Bambaataa enjoyed throwing stuff like Kiss, The Monkees, calypso tunes,

bongo breaks, movie soundtracks, even the Pink Panther theme into a funky set;

though the group's appearance reminded him of 'some Nazi type of thing' (Fricke

and Ahearn 2002, pp. 310-11), he particularly liked the electronic sound of Kraftwerk,

an esoteric taste he shared with Baker, and which was partly responsible for getting

the white disco producer and the black hip-hop DJ working together (Baker 1999).

Standard histories of hip-hop credit Kraftwerk's robotic drum machines with kick-

starting electro, and it is clear that the beat of 'Planet Rock' is copied verbatim from the

track 'Numbers' off their futuristic 1981 Computer World album. (Copied, not sampled:

Baker found, for twenty dollars, someone who owned one of the newly released

This content downloaded from

201.158.189.66 on Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:47:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The story of ORCH5 345

Roland TR-808 'drum machines' and who was able to program the Kraftwerk beat

into it.) But Planet Rock's minor-key ORCH5 and dark synthesizer tune also trans-

migrate the resonances of an earlier Kraftwerk project, a darker record whose con-

cerns were more political, more historical, and more narrowly European. Bambaataa

reports that, given the early 1980s absence of listening booths in used record stores, he

picked up vinyl whose cover art and lettering 'looked funky' (Fricke and Ahearn,

p. 46); it's hard to imagine what would have made him pick up Trans Europe Express.

Figure 1 reproduces the US front cover of the Kraftwerk LP; its nostalgic glamour

seems worlds away from beat-boxes and the Bronx. In fact, the German front cover

was a stiff shot of the four members of Kraftwerk in black and white, taking what they

called their 'string quartet' poses. The album's packaging features carefully staged

and colourised pictures that evoke not technological modernity, but ambiguously

pastoral images of the 1930s, as when the four members of the group, dressed in

darkly conservative wool suits, arrange themselves stiffly and formally around a caf6

table draped with a red-and-white checked tablecloth, all in front of a painted

photographer's backdrop of quaint Bavarian landscape. They might indeed be wait-

ing for a local train - or perhaps something a little less volkstiimlich, like a meeting of

the local NSDAP (see Figure 2).7

The nostalgia really cranks up, though, with the album's idiosyncratic table of

contents, which takes up the entire inside sleeve (see Figure 3). Drawn on a back-

ground of music staves, using musical notation, even introducing a hand-drawn

picture of Franz Schubert, the Austro-German composer we can most easily imagine

picnicking with the boys around a Bavarian chequered tablecloth, this guide to the

album sets us up to hear it as an extended meditation on classical music, on German

identity, and - given the psycho-symbolic import of trains and train-trips - on loss.

Thus it is hardly surprising that the entire record is unified both tonally and

motivically - not implausible for a pair of conservatory-trained German musicians

who worked for a time under Karlheinz Stockhausen, but also, here, an expressive

strategy: to use the structural apparatus of European classical music to comment on its

decline and death.

To be fair, this reading of Trans Europe Express is conspicuously unsupported by

definitive statements from Kraftwerk's creative team, composers Ralf Hiitter and

Florian Schneider. Artistic pronouncements emanating from their Kling Klang studio,

of which there have been many over the years, are in general useless for hermeneutic

purposes, since a large part of the group's conceptual aesthetic is based in deadpan

irony and DADA-esque media jamming. Some of the interpretive frames placed by

Hiitter and Schneider around Trans Europe Express are patently silly, even offensive,

like the notion that since Kraftwerk made 'electronic blues', and classic Negro blues

often involve trains, they ought to record a song about the European train network

(Bussy 1993, p. 86). Foolishness aside, Kraftwerk and their fans have seen the group's

paean to high-speed train travel as congruent with their positive embrace of moder-

nity and technology, a fitting sequel to albums themed around the Autobahn (1974)

and Radio-Activity (1975): 'movement fascinates us ... all the dynamism of industrial

life, of modern life' (Hiitter as quoted in Bussy 1993, p. 88). Yet a fundamental

incongruity remains. How to reconcile a briskly unsentimental view of industrial

modernity with faded images of pre-war gemiilichkeit? What do old-fashioned

musical notation and a wan little cartoon of Schubert have to do with the futuristic

embrace of 'musical machines' that eliminate the very possibility of spontaneity or

virtuosity? One possibility, not to be followed up here, is the critique of routinised

This content downloaded from

201.158.189.66 on Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:47:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

346 Robert Fink

Figure 1. Trans Europe Express, United States front cover.

classical music performance that would become explicit as soon as Kraftw

using robotic dummies in 'live' performance: 'The interpreters of classic

Horowitz for example, they are like robots, making a reproduction of the mus

is always the same. It's automatic, and they do it as if it were natural, which is

(Hiitter as quoted in Bussy 1990, p. 161).

Internal music evidence seems to suggest, however, that it is not jus

music's star interpreters who are 'dead'; Trans Europe Express manipulates

material so as to let us hear, if we wish, the death of classical music itself

Example 2d, which transcribes not ORCH5, but the mournful synthesize

Baker, Bambaataa and Robie lifted and made famous in 'Planet Rock'. Its

chromaticism and, as we'll see, its signifying function within the album's m

will justify the slightly portentous label of 'Weltschmerz' theme. (Within a

tive community based in European tonal music, the theme's specific habit

leaps up to the lowered sixth degree of the minor scale will overwhelmingly be

expressive of pain and sorrow.) With its syncopated chuffing, track-rattli

This content downloaded from

201.158.189.66 on Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:47:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The story of ORCH5 347

Figure 2. 'Like extras from the film Cabaret': 1930s imagery recaptured for Trans Europe Express.

and sampled screeches of metal on metal, the song 'Trans Europe Express' is an

onomatopoetic train ride, certainly; but its real expressive significance does not

become clear until we hear it as the dark night-time echo, the negation, of an earlier

trip taken in broad daylight. 'Europe Endless', the first song on the album, is in many

structural ways the expressive double of 'Trans Europe Express': the latter begins in

the gloom of dissonant stacked fourths resolving to E-flat minor (see Example 2c, left),

and then modulates, via Doppler effect, down a third to C minor; while the earlier

track, opening with radiant G major arpeggios, modulates up a third to an even more

sunny B major. A motivic transformation clinches the connection: the same rhythm

and contour that outline soggy C-minor Weltschmerz in 'Trans Europe Express' first

appear at the climactic moment of 'Europe Endless', at the peak of an endless,

rhapsodic prolongation of the dominant and its energy. (The 'painful' appoggiatura

progression from flat sixth scale degree to the fifth accordingly starts off as the more

sanguine use of the natural fourth scale degree to decorate the major third; see

Examples 2a and b.)

This content downloaded from

201.158.189.66 on Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:47:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

348 Robert Fink

-EUROPE ENDLESS 9 A.WRK15 0 1 TRAN-EUROPE EXPRESS=

!il .iiWOD ii :I S ~UTE I ! ! i CNEDRfORIN !:} !..7.. !.!:i. :/: ! ;!!.:i:!SCHNEIDER i:?: !i: "'A :::::q :.{!i:ELECTONKU+ :i ::::::::: :::::-/ / / :::]VOIE :!: iP ;i!!-i::!]. !.!: i!-!!.?i:i:!!! :.i !.;:i!!q-! ! 1# .!:.i:: :: ::il]i !:.:. :.i.ii ; :

! 8:i:!i.i;. i. !.i~i

:::::::: S@i.:!!~ .iZ:

, ! ~E:i::.:::!S.. iNi: :::i

EI['!i:i,;t -::,~i.:::-"i:i i,:..l i;:.;::;i.:

:.i:i.:i::::!;:;!:!i!.!:

:;: :: : :. :....:::

::::. ]:..:

.:: : :::-:

i: }i ] :ii:: i-.::.i .:::!:~;!!]P !!:i:sE!:' ::ii :::&

f,:iii',i:,,::0,B E ~ ~ -i}.i

i , 8 N:i:::ilii:ii i : .i;i.i i! Si-iii

~i] i:i::i,(,:i:::::: ?! : '!!i:'i:!:ii.::ii:i:::.:i :!'i!!;'@

i ! 0i!!:'i:!i 3!i-i:

1:./. :.:.:?.i

,!,:;:ii:i::::i!:!i!

WORS; H T+SCHULT

:iS !!:.i-:! : .:i :#:

:, .i:.3:!:::;::.....

: i : ..........

i:i: iii::ii i:.. :::.:.

~THE HALL OF MRQS _=7'5 METAL ON METAL ?6,52

MSz UT +SHEDRKARL BARTOS EECRNIC PRUSIN MUSIC. NTE

WORDS HUTTER +SCHNEIDER +SCHULT OLFANG LUR ELECTRONICPOEECUSSION

-SHOWROOM DUMMIES?_6.1O FRANZ SCHUBERT= -42

MUSICS HUTTER ENGINEERS TER

WORDS, HOTTER PETER RORUG KEINGKAGS TUDO

... ....TOA

........ ..USCKUKRUSSTDIO1010

......... .. .. .... .. . .. .... . ....... : :MUSIC.HUTTER

: . ENDLESS ENDLESS

+SOIHNR)E

. 45z

ELLI HALVERSON THE RECORD PLANT

? " . : :: :i ii: ;: :. ;::: :: " : :::i :: :: :. :..:/ .:::::..: ::r .:. ::i :::: i :ii. :: ::i::::.: :i.:":::;: :U i.:d :.':!5 i .::: Y Jii::7 :.: i :.:i:: : ..-. .. i:::! :. ::1]] : ]!til :]iil ::i3.ii::iii: !! :i!:}!i!:.ilii::i::i

~EUROPE ENDLES

i~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~~; : : :: : : : : ::::: ;: : :::. .:.:::: !.!::::. ':.. !!::: ::::::::::::: : : '.:: ::: :::: ::: ::::::::::::: ::::::::::: ::: :::::::::::::: ::::::: :.! ::!. ' t:!!::: :/! .:::: 1!.':', .. ,, h? @ /@ i.8 11ii;/ ; //;1;`!;;1/3.; ' ,;.:i!8 ;

:: , . . : :

::".' ...:~: i::iii .:::: -:.:-:]]

.. .......... ~ :????~lp~l

I mW

...... ..... ......... ... ====================jiii :!:: :: :: :::: ::: : :::: : : ;.i -:, ;;; ..: :. .... .. .. . ..S ii~ :]:i ::i:::i .......

:. .... ........... : :];. ..... :: g:::: :,.:.::.:...::: ,:.,.:::::::.: ......

.: :. - : i: : : : : . : : . i :::::: : : :::.]i:ii iii..ii !i::. ]:i:.:::ii i:i ii: .i :::i,.: .:. ......... .: ... ........ .

J o:": :::: : :- : : ::l. :ilj: iiil Illll : :j:;?.-' ?~ii_ '.;:~l-i;: i

:::" :: ::::THE

:::: :":

HNL: ::: ::: ::::

0F,--: : m: ::qR

:: : :: .::::::

FRANZ :::::::: ::::::: ::::~ ............: ? ::?I::: 1

SCHUBERT:::':?

..... :.: .:,:,,:. .. ......:.::i~i:

Figure 3. Trans Europe Express, musical 'table of contents' on staff paper background.

Just before that ascent, Schneider murmurs a verdict -on European culture:

'Eleganz und Dekadenz'. The synthesizer theme that Baker and Bambaataa will later

borrow is made, over the course of Kraftwerk's album, to act out that decay; at the end

of 'Metal on Metal', the track that follows and extends 'Trans Europe Express', it is

buried beneath dissonant fourths and finally crushed under the wheels of technologi-

cal modernity. Bambaataa would have been quite familiar with this process; we know

that one of his early-1980s Zulu Nation tricks was layering the fiery rhythms of

speeches delivered by Malcolm X over the unbroken thirteen minutes of 'Trans

Europe Express' plus 'Metal on Metal' as they followed one another on the B-side of

Trans Europe Express (Brewster and Broughton, p. 243). And, if the album cover's

musical notation and nostalgic imagery are not enough, consider the penultimate

track, 'Franz Schubert', in which the decay of the Europa-Weltschmerz theme is

explicitly linked to the most gemiftlich of German classical composers. Back in the G

major of the album's opening, the basic theme itself decays, contour and pitch

This content downloaded from

201.158.189.66 on Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:47:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The story of ORCH5 349

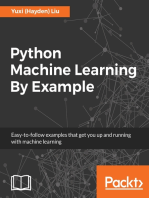

Tr. 1. Europe Endless

[4:02]

___ ?1_______I ___ ,"etc

2a 6

,q[5:03] -3V .3

V7... I V -

[8:05] -P - I

I

2b

Tr. 4. Trans Europe

Express [1:331

Planet Rock

2d d_

Tr. 6. Franz Schubert j

[0:34]

2eI I r

(distant, w/heavy reverb, delay)

Example 2. Motivic relationships in Kraftwerk, Trans Europe Express (1977).

dissolving under massive reverb and delay effects (see Example 2e). It sou

dream ... or a ghost.

Welcome to the bardo realm.

Lost in space: ORCH5 and the retro-futuristic sound of electro-funk

Thus my fundamental hermeneutic leap: if Kraftwerk's Trans Europe Express album

about the collapse of European culture as embodied in the decay of its classical music

and if the appropriation of the Weltschmerz theme by Baker and Bambaataa trans-

ferred some of that anxiety and gloom into African-American music, then John

Robie's ORCH5 blasts capture, perhaps by accident, the sad revenant of European

classical music in a single digital sound. This is how the classical ghost (Stravinsky

standing in here for Schubert, who is standing in for the entire Germanic concer

music tradition) gets trapped in the hip-hop machine.

Or, should we rather say, is liberated by the hip-hop machine? There is an

argument to be made that ORCH5, through a complex transmigration of tones, was

soon able to stand expressively by itself without the entire structure of feeling I have

just outlined, since nobody in the Bronx actually linked it consciously to the death o

European art music, about which, presumably, they couldn't have cared less. Baker's

original idea for 'Planet Rock' was to avoid, for copyright reasons, any direct use o

Kraftwerk's tunes (Baker 1999); you can hear the first version of the track, which h

actually thought was better than the version the label decided it was perfectly safe t

This content downloaded from

201.158.189.66 on Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:47:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

350 Robert Fink

Afrika Bambaataa, "Planet

Rock, " 1982

9 I I I I Q

Jonzun Crew, "Pack Jam (Look Out for the OVC),"

1982-83

3blh YSbin gt s," 98

Twilight 22, "Siberian Nights," 1984

3c

Example 3. Afro-futurism in 1980s electro: the influence of 'Planet Rock'.

release,8 underneath the smooth vocals of his next production, Planet Patrol's 'P

Your Own Risk'. That track uses a different synthesizer tune, while a new and f

clavinet riff gives the groove a more soulful feel; but ORCH5, the signature sou

'Kraftwerk in NYC, ca. 1982', remains, now doing all the signifying work by itse

sonic synecdoche, minor-key ORCH5 began to take on an (after)life of its own:

carried the weight of the decaying European tradition in Diisseldorf or Berlin

taken on quite different, African-American terms in the five boroughs.

The transmigration seems to have proceeded in two phases. In the first, ele

producers troped directly off the science-fiction imagery of Baker and Bambaa

'Planet Rock'; ORCH5 was heard within the matrix of the later, more ove

cybernetic Kraftwerk, the orchestral blasts and doom-laden synthesizer

resonating, after the fact, more with The Empire Strikes Back than with Sch

and Weimar fascism. This played perfectly into an Afro-futurist cultural pro

that Bambaataa consciously took over from Sun Ra and George Clinton, and, as

see below, provides a key imaginative linkage to the house and techno music t

the Zulu Nation pioneer claimed as the logical consequence of his 'electrif

hip-hop.

Science fiction, presumably, is the intended referent of the alla breve minor-key

synthesizer tune that begins its methodical climb, punctuated by brassy orchestral

'explosions', at about 2:50 into 'Planet Rock' (see Example 3a). Although it sounds

dark and serious enough to be from Trans Europe Express, this skeletal scalar ascent

was invented expressly for 'Planet Rock'. The grainy string-like timbre and plodding

tension evoke Kraftwerk's mordant, robotic version of classical music pretty well -

but they also sound a lot like the bombastic pastiches of late-Romanticism that lent

excitement to battle scenes in Reagan-era space and adventure epics like Star Trek and

Raiders of the Lost Ark.

This content downloaded from

201.158.189.66 on Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:47:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The story of ORCH5 351

This Kraftwerk-meets-John-Williams-on-the-synthesizer trope was easy to

imitate, but it demanded appropriate content. The desire to copy that distinctively

stiff keyboard sound forced electro producers to emphasise exotic, futuristic topics -

the ones that would, paradoxically, justify the retrograde sound of dead European

music in their grooves - and they rose to the challenge with rap songs based on

science fiction, computers, video games, and nuclear annihilation. A constellation of

sonic cues assembled itself into the style called 'electro': vocoders applied to the MC

for a cold robotic sound; the rigid bounce of electronic percussion, with static-laden

snares and the distinctive chiming 'cowbell' of the Roland TR-808 well to the fore;

long unison synthesizer tunes in regular, un-syncopated rhythms; and, slicing

through it all, minor-key blasts of ORCH5 providing a dark cinematic edge.

The spread of minor-key ORCH5 was not just a consequence of digital sampling

getting cheaper - it was a precise, deliberate imitation of Bambaataa imitating

Kraftwerk. The original Stravinsky chord sampled by Vorhaus was an orchestration of

the open fifth A-E, and thus had no modality; only the multiple-voiced version in

'Planet Rock' is minor. As Example 3b demonstrates, imitation was often the maxi-

mally sincere form of flattery: Larry Johnson and Maurice Starr of The Jonzun Crew

changed just enough notes in their version of the 'Planet Rock' riff to keep their 'Pack

Jam', a catchy paean to the popular video game Pac Man, from actually infringing

copyright. (Baker himself had set the precedent by releasing 'Play at Your Own Risk'

under the group name Planet Patrol, the title of a popular Atari video game.) 'Siberian

Nights', programmed by a young Fairlight whiz named Gordon Bahary (who had

worked on one of the first Fairlights in America while helping Stevie Wonder get ready

for his Secret Life of Plants tour), used a lowered second scale degree to give its riff a

Soviet Russian accent (see Example 3c); but the combination of high-tech electronic

percussion, classical sounding minor-key organ solos, and meditations on technologi-

cally enabled cultural extinction ('You got nuclear war, atomic rain / And nuclear

winter gonna freeze your brain!') seems, like 'Planet Rock', nicely balanced between

the futurist dystopianism of Kraftwerk and the retro-futurism of George Lucas.

Or should we rather name-check George Clinton? The Jonzun Crew's 1983

album was, appropriately enough, entitled Lost in Space. On it, their project to

continue the psychedelic Afro-futurism of Sun Ra and Parliament-Funkadelic as

reinvigorated by Afrika Bambaataa is made explicit, as 'Pack Jam' rubs shoulders

with freaky tracks like 'Space Cowboy' and 'Space is the Place'. Mark Dery argues that

'if there is an Afrofuturism, it must be sought in unlikely places, constellated from

far-flung points' (Dery 1994, p. 124). His example is the opening of Ralph Ellison's

Invisible Man, in which the 'proto-cyberpunk' narrator's desire to hear Louis

Armstrong on five simultaneously spinning turntables prefigures the cut-and-splice

adventures of Grandmaster Flash and his 'Wheels of Steel'. But what more unlikely

constellation than the one just outlined, where sonic ghosts of Stravinsky and

Schubert battle each other inside a funky evocation of a video arcade, where Kastchei,

the medieval Russian sorcerer, break-dances through the endless Siberian night of

nuclear winter?

A key aspect of the Afro-futurist imagination lies in a complex identification

with the science-fiction Other, with alien-ness, on the part of an Afro-diasporic culture

still dominated by the dark legacy of subjugation to more technologically advanced

colonialism. From this springs a powerful desire for the Mothership Connection, a

desire to appropriate and unleash the power of alien technology - usually imagined

simultaneously as ancient technology - on behalf of the oppressed (Kelley 2002). It

This content downloaded from

201.158.189.66 on Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:47:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

352 Robert Fink

only remains for the post-canonic musicologist to point out that, in the sound

electro-funk, it is European art music that is cast, consciously or not, in

ancient, alien power source. Kastchei is riding the Mothership, and ORCH

talisman, the classical jewel hidden beneath the hip-hop Pyramids. 'Musi

cry the members of the Soulsonic Force, and we know what they mean.

power to fill Stravinsky's Firebird up with rocket fuel.

Techno scratch: ORCH5 takes a break

In the second phase of ORCH5's transmigration, the sample loses even the ve

association with orchestral art music afforded by Bambaataa's 'sci-fi soundtr

trope, and is absorbed completely into the generic musical practice of early-

hip-hop. Other NYC DJs and producers heard Bambaataa's polyphonic orc

'blast from the past', those eight sets of grace notes sliding up to the tonic,

imagined not the laser cannons from Star Wars, but a new and funky kind of digit

turntable scratch.

The precedent had been set by the first generation of hip-hop DJs. Most of the

cutting and scratching of early performers like Grand Wizard Theodore, Kool DJ

Herc, and Grandmaster Flash has been lost to posterity, and if one is familiar only with

recorded output from the period, the connection between hip-hop beat-juggling and

ORCH5 might seem obscure. But a trace here and there allows provisional reconstruc-

tion of how sampling Stravinsky could function like scratching vinyl in the Bronx,

ca. 1982. Consider the track 'Flash Tears the Roof Off', a 2002 recreation of a classic

turntable mix from the early 1980s. In it, Grandmaster Flash (Joseph Sadler) cues up

two copies of a famous break from Funk, Inc.'s 1972 soul-jazz record, 'Kool is Back'.

(This drum break - sampled and played back, probably, on a Fairlight CMI - was

made famous among white folk in 1983 when Trevor Horn used it to spice up his

production of Yes's 'Owner of a Lonely Heart'.) Flash proceeds to execute the classic

manoeuvre of Bronx sound system DJ-ing, which he more-or-less invented, alter-

nately rewinding and releasing the records, looping, stretching and chopping up the

short drum fill into an extended dance break. So far, standard hip-hop practice, and

hardly worth mentioning, except for a strangely familiar sonic intruder, lurking in the

grooves of the record. Unlike the everywhere-sampled breaks in tracks by James

Brown ('Funky Drummer') and The Winstons ('Amen, My Brother'), which start

'clean', the first beat of this drum fill is punctuated by a loud splat from the entire

quintet, cutting loose on a funky added-sixth chord. As voiced and swung in 'Kool is

Back', this 'G-added-sixth' chord sounds enough like ORCH5 that listeners often

mistake one for the other: in both cases, members of the ensemble attack early and

slide up to meet a sharp, staccato downbeat with heavy emphasis on an open fifth,

which then reverberates into recorded space.

I wouldn't insist on the resonance, were it not for what Grandmaster Flash does

with the sound. As he juggles this break, he picks up the 'kool' chord attached to its

first beat and - intentionally or not - juggles it, too. The sharp tutti attack is now the

direct result of a turntable scratch, and it marks the syncopated downbeats of chopped

and sampled breaks. When hip-hop DJs and producers heard ORCH5 in 'Planet

Rock', some of them quickly realised that it could be used in precisely the same

way, and they began dropping it into tracks filled with sampled breakbeats

and digitised techno-scratches to create an up-to-the-minute, 'electro-funky' style

of hip-hop. ORCH5, no longer just the sound of science fiction, but also

This content downloaded from

201.158.189.66 on Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:47:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The story of ORCH5 353

'the hit-before-the-breakbeat-starts', could then be rhythmically activated through

(often faux) scratching and beat juggling.9 Used this way, as in Mantronix's 1985

classic, 'Needle to the Groove', the Firebird chord becomes a purely percussive accent,

stripped not just of dark, minor-key glamour, but of any tonal function at all. This must

be the reason Kurtis Khaleel of Mantronix simply couldn't be bothered to adjust the

pitch level of his ORCH5 sample to that of the surrounding track, triggering it instead

at a consistent and grating half-step below the tonic. The effect is, to musicological ears,

genuinely avant-garde (if probably serendipitous). 'Needle to the Groove' recycles

most of the aural signs of electro: vocoded chanting; mechanical-sounding TR-808

drum beats; and, of course the ubiquitous ORCH5 sample, but now on the off-beats,

syncopated, within an expressive context that betrays no hint of futurism, Afro- or

otherwise. The song's infectious refrain, spinning out of its self-referential title phrase

('We got the needle to the groove/We got the beats that'll make you move'), makes it

clear that classical music, or at least the fragment of it trapped within ORCH5, had

achieved, through systematic musical transmigration, a great liberation.

By the mid-1980s, ORCH5 is thoroughly naturalised within hip-hop, to the point

that one need neither invoke the death of European culture nor the incipient descent

of the Mothership to use it. It doesn't have to sound melodramatic and minor, and you

don't even have to put it on the downbeat. It's just one of the many funky things that

can happen when you put the needle to the groove.

Postlude: Strings of life

At this point it would be possible to follow dozens of tracks towards the present day;

but let us follow the most direct route, the high-speed techno train that runs between

Diisseldorf and Detroit.

Few people in the pop music world of 1982 even knew what a Fairlight

was. After the huge success of 'Planet Rock' and Baker's follow-ups, many urban

musicians casting around for an ORCH5-like sound settled on what one might call the

'techno minor' triad. A staccato minor chord played through a grainy analogue string

patch, with its envelope tweaked to provide both a sharp percussive 'chuff' at the

attack and a pronounced reverb at the release, sounded pretty much like ORCH5, if

you weren't too particular. Techno minor plus beats from a machine was all you

needed to get the sound, as a track with the utilitarian title of '122 B.P.M.', pro-

grammed for a production music house by David Linn, inventor of the Linn drum

machine, demonstrated.

This is the sound of very early Detroit techno, for instance the group Cybotron,

a group of suburban black teenagers who everybody took for 'some white guys from

Germany'. 'Clear', Cybotron's first (and only) hit, features rhythmically syncopated

repetitions of the techno minor triad over a lopsided Computer World-style mechanical

beat. When a pyramid of synthesizer tones dissolves into a melancholy tune right out

of 'Trans Europe Express', it is clear that Juan Atkins, the brains behind Cybotron,

wanted to be taken as white and from Germany, and that 'Clear' is meant as overt

homage to the paradigmatically white German guys who made up Kraftwerk. Its

relation to 'Planet Rock', Afrika Bambaataa and the Zulu Nation was much more

equivocal; 'Clear', and the Detroit techno music that sprung from it, program-

matically eliminated all traces of hip-hop from the sound (no rapping, no inner-city

accents) - which looks, in retrospect, like an attempt to synthesise a futurist electronic

music by filtering out the 'Afro' (i.e. the Bronx) in Afro-futurist hip-hop. As the

This content downloaded from

201.158.189.66 on Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:47:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

354 Robert Fink

Detroit style matured, the techno minor triad was featured in front of m

spiralling keyboard riffs and the rat-a-tatting of the Roland TR-808, as in

track 'Off to Battle', a more sophisticated effort by Atkins, now working

nom-de-microprocessor Model 500. (He took the name from the Roland MC

Composer, one of the first affordable digital sequencers.)

In 1997, Derrick May, another crucial innovator of the Detroit sound,

CD of his early tracks. It was the tenth anniversary of his first major hit, a tr

cited as the single inspiration for the global techno scene. In a short new track

Relic Mix', he reached back and collected some of the sounds of his early c

notably the techno minor triad. For the project, he took out of mothballs

model Ensoniq Mirage, the first eight-bit digital sampler to be priced unde

sounds are relics twice over, because May, famously, took the Mirage to

Orchestra Hall and did some surreptitious sampling during rehearsals, th

some cold and grainy versions of ORCH5 for himself.

Relics of relics; we appear to have looped back to the beginning, an

decaying Europe of dead sounds and music. But May's ghostly relics, his b

the past, whisper of liberation, at least for classical music, in the bardo

years before, May, producing under the no-nonsense moniker Rhythim is

had used orchestral samples to make one of the seminal leaps forward in

techno explosion, an unsentimental masterpiece of irrepressible energy

every dance music historian's list of the most influential tracks of all t

stabbing tones derived from the sound of an orchestral violin section (the

grotesquely exaggerated, so that each keystroke sounds a little like ORCH5

irregular, accelerating drifts over a stuttering, vaguely Latin piano riff.

some of the sound-world of Kraftwerk, but none of its aesthetic: both sam

and sampled violins have a nervous, un-quantised intensity - a swing, on

call it - that is continents away from the ponderous, lacquered decay of K

Studios. The Roland TR-808 and 909 that drive the track forward no longer

machine guns, laser cannons, or dot-matrix printers gone mad; inste

congas, djembes, shakers...

If Kraftwerk trapped the classical ghost in their machines, and Afrika Bam

let it out of his, to break-dance for a little while, then May offers up his mac

ridden, hard, by an electronic Orisha. Rhythim is Rhythim, after all.

There is nothing decadent about this music. It manifests a fierce joy,

starting over. May called it - how unexpected, how perfect - 'Strings of Life'.

if Stravinsky would ... ah, who really cares?)

Endnotes

music' article (as a hard-boiled detective story)

1. Huitter interviewed by Sergey Chernov, St.

in his column at the Village Voice (Gann 1997),

Petersburg Times, 972, 28 May 2004; Fairlight

has titled his web log (and associated radio

slogan as quoted in Holmes 1996-1999; 'Planet

Rock' lyrics as transcribed by the author. station) simply 'Postclassic'. (The web log is

2. The reference here is to Milton Babbitt's infa- hosted by http://www.artsjournal.com, and

mous article in High Fidelity, often anthologised the [highly recommended!] radio station, win-

under his preferred title, 'The composer as ner of a Deems Taylor award, is streamed on

specialist', but which appeared in 1958 with the http:/ /www.live365.com)

more journalistically apropos editorial title,4. Audio samples of the Fairlight's sound library,

'Who cares if you listen?'. For the revisionist including ORCH5 can (as of late 2004) be

soul-searching to which I refer above, see accessed at Holmes 1996-1999. See also the

Ziporyn (1998). larger downloads of sound banks from the

3. Kyle Gann, who once published a wicked and Hollow Sun website (http:/ /www.hollowsun.

witty parody of the perennial 'death of classical com/vintage/fairlight/).

This content downloaded from

201.158.189.66 on Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:47:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The story of ORCH5 355

5. It is not possible for this author to tell exactly to play in real time all the sounds of a jazz or

which recording of Stravinsky's Firebird was rock combo - was extremely difficult. Using the

sampled by Vorhaus. One could, of course, ask machine incorrectly, 'hacking' it, on the other

him, but I refrain as a matter of principle: to ask hand, was easy, and the sounds resulting were

Vorhaus to identify the recording would be to often, as in this case, more interesting than the

open huge swaths of the hip-hop world to the sonic output intended by the machine's crea-

possibility of copyright infringement lawsuits. tors. For details on programming the Fairlight

In the hip-hop world, this is called 'snitching'. CMI, as well as screen shots of its control pages,

Joseph Schloss, in his recent study of hip-hop see Holmes (1996-1999).

producers, refuses for this reason to transcribe 7. This may seem a far-fetched reading - but it

into musical notation any of the chopped and appears to be exactly what Pascal Bussy meant

looped samples he discusses (Schloss 2004, when he saw Kraftwerk in this picture 'almost

pp. 12-15, 120-30). as if posing as cardboard cut-out extras for a

6. A technical note: this eight-voice polyphonic scene in the film Cabaret' (Bussy 1990, p. 85).

mode, in which the same sound is assigned to The reference can only be to the mise-en-scene

each one of the machine's eight audio registers, of the movie's one daytime exterior number,

is the default setting on the Fairlight's Register 'Tomorrow Belongs to Me', with its chorus

& Keyboard Control Page (Page 3). Thus a high of apple-cheeked Brown-shirts giving an

level of computer literacy would be required to impromptu, menacing concert in the sunshine

get the CMI to do anything else but simply play of a suburban Biergarten.

eight iterations of the sample in Register A 8. They were wrong, and he was right to worry.

when eight keys were pressed down. The only Kraftwerk, once they became aware of this

other 'programming' skill one would need to appropriation, responded in a distinctly

produce 'Planet Rock' was the ability to use a un-postmodern way: they immediately sued

light pen on Page 2, Disk Control, to select a file Baker and Bambaataa for plagiarism, furious

like ORCH5 from the contents of the floppy disk that they had not been correctly footnoted: 'If

and load it into the default memory location, you read a book and you copy something out of

which is, of course, Register A. The recording it, you do it like a scientist, you have to quote

engineer could have shown Robie or Baker how where you took it from, what is the source of it'

to accomplish this in less than thirty seconds. As (Kraftwerk percussionist Karl Bartos as quoted

so often in the history of electronic dance music in Bussy 1990, p. 125).

(analogous stories could be told about the 9. There may have been iterations of ORCH5 or

Roland TB-303 bassline generator and the birth ORCH5-like sounds on DJ records, but I have

of acid house), using the machine correctly, to never seen one. One could, of course, have

make conventional music - the Fairlight, for attempted to scratch with 'Planet Rock' itself,

instance, could be laboriously programmed, but that would have been unutterably lame

using register control and keyboard mapping, (Schloss 2004, pp. 114-19).

References

Babbitt, M. 1958. 'Who cares if you listen?', High Fidelity, 8/2 (February), pp. 38-40, 126

Baker, A. 1999. Interview with Bill Brewster and Frank Broughton, 25 January 1999, reproduced in full at

http: //www.djhistory.com

Brewster, B., and Broughton, F. 2000. Last Night a DJ Saved My Life: the History of the Disc Jockey (New York,

Grove Press)

Bussy, P. 1993. Kraftwerk: Man, Machine, and Music (London, SAF Publishing, Ltd)

Crab, S. 1990-2004. '120 years of electronic music (update v3.0)', http://www.obsolete.com/120 years/

Dery, M. 1994. 'Black to the future', in Flame Wars: The Discourse ofCyberculture, ed. M. Dery (Durham, NC,

Duke University Press), pp. 179-222

Fairlight Instruments Pty Ltd. 1983. Brochure for Fairlight Computer Musical Instrument, online at:

http:/ /www.hollowsun.com/vintage / fairlight/brochure.zip

Fink, R. 1998. 'Elvis Everywhere: musicology and popular music studies at the twilight of the canon',

American Music, 16/2, pp. 135-79

Fricke, J., and Ahearn, C. 2002. Yes Yes Y'all: The Experience Music Project Oral History of Hip-Hop's First

Decade (New York, Da Capo)

Gann, K. 1997. 'Who Killed Classical Music? Forget it, Jake - it's uptown', Village Voice, 52/3 (January 21),

p. 60

Holmes, G. 1996-1999. The Holmes Page: Fairlight CMI, at: http://www.ghservices.com/gregh/fairligh/

Horowitz, J. 1995. The Post-Classical Predicament: Essays on Music and Society (Boston, Northeastern

University Press)

2005. Classical Music in America: A History of Its Rise and Fall (New York, Norton)

Huyssen, A. 1986. After the Great Divide: Modernism, Mass culture, Postmodernism (Bloomington, IN, Indiana

University Press)

Kelley, R.D.G. 2002. Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination (Boston, Beacon Press)

This content downloaded from

201.158.189.66 on Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:47:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

356 Robert Fink

Reynolds, S. 1998. Generation Ecstasy: into the World of Techno and Rave Culture (New York,

Schloss, J. 2004. Making Beats: the Art of Sample-Based Hip-Hop (Middletown, CN, Wesley

Press)

Steshko, J. 2000. Stravinsky's Firebird: Genesis, Sources, and the Centrality of the 1919 Suite (Ph.D. thesis,

UCLA)

Ziporyn, E. 1998. 'Who listens if you care?', in Strunk's Source Readings in Music History, ed. L. Treitler (New

York, Norton), pp. 1,311-18

Discography

Afrika Bambaataa & the Soulsonic Force, 'Planet Rock' (1982), Don't Stop ... Planet Rock. Tommy Boy

TBCD 1052. 1992. Written and produced by Arthur Baker and John Robie

Afrika Bambaataa, United DJs of America Presents Afrika Bambaataa: Electro Funk Breakdown (mix CD, 1999).

DMC DM 40012-2. 1999

Art of Noise (Anne Dudley, Trevor Horn), 'Close (to the Edit)', (Who's Afraid of) The Art of N

Universal CD 53194. 1998

Kate Bush, 'The Dreaming', The Dreaming (1982). Capitol CD 46361. 1990

Aaron Carl, 'Down (Electro Mix)' (ca. 1986), Timeless: The Essential Metroplex Classics Mixed by Juan Atki

Metroplex MCD-01. 2003

Cybotron (Juan Atkins), 'Clear' (1983), Clear. Fantasy Records FCD 4537-2. 1990

Funk, Inc., 'Kool is Back' (1972), Funk, Inc. Prestige PRCD 24156-2. 1995

Grandmaster Flash, 'Flash Tears the Roof Off' (turntable mix), The Official Adventures of Grandmaster Fl

Strut CD 011. 2002

Jive Rhythm Trax (David Linn), '122 B.P.M.' (1982), Street Jams: Electric Funk, Vol. 2. Rhino R2 70756. 1992

The Jonzun Crew (Michael Johnson, Maurice Starr), 'Pack Jam (Look Out for the OVC)', originally released

on Lost in Space (Tommy Boy TBP-1001, 1983), reissued on Street Jams: Electric Funk, Vol. 2. Rhino R2

70756. 1992

Knights of the Turntables, 'Techno Scratch' (1984), The Wild Bunch: Story of a Sound System. Strut CD 0

2002

Kraftwerk, 'Numbers', Computer World. Elektra/Asylum 9 3549-2. 1981

Kraftwerk, Trans Europe Express. Capitol CDP 0777. 1977

Mantronix (Kurtis Khaleel), 'Needle to the Groove', Mantronix: The Album. Warlock 8707. 1985

Derrick May, 'A Relic Mix', Derrick May: Innovator. Transmat TMT CD 4. 1997

Model 500 (Juan Atkins), 'Off To Battle' (1987), Timeless: The Essential Metroplex Classics Mixed by Juan

Atkins. Metroplex MCD-01. 2003

Planet Patrol, 'Play At Your Own Risk' (1983), Electro Science Mixed by the Freestylers. Urban Theory

URBCD 03. 2000. Written and produced by Arthur Baker and John Robie.

Rhythim Is Rhythim (Derrick May), 'Strings of Life' (original mix, Transmat MS 4, 1987), Derrick May:

Innovator. Transmat TMT CD 4. 1997

Twilight 22 (Gordon Bahary, Joseph Saulter), 'Siberian Nights', originally released on Twilight

(Vanguard VSD-79452, 1984), reissued on Street Jams: Electric Funk, Vol. 2. Rhino R2 70756. 1992

David Vorhaus et al., 'Fairlight IIx Sample Library, Disc 17', Pro-Rec Audio Sampling CD. 2003

Yes, 'Owner of a Lonely Heart', 90125. Atlantic CD 90125. 1983

This content downloaded from

201.158.189.66 on Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:47:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Kaleidophonic Modernity: Transatlantic Sound, Technology, and LiteratureFrom EverandKaleidophonic Modernity: Transatlantic Sound, Technology, and LiteratureNo ratings yet

- The Story of ORCH5Document18 pagesThe Story of ORCH5RaspeLNo ratings yet

- Sounds of Modern History: Auditory Cultures in 19th- and 20th-Century EuropeFrom EverandSounds of Modern History: Auditory Cultures in 19th- and 20th-Century EuropeDaniel MoratNo ratings yet

- Simon Reynolds - Creel PoneDocument3 pagesSimon Reynolds - Creel PonemfgsrossiNo ratings yet

- Rationalizing Culture: IRCAM, Boulez, and the Institutionalization of the Musical Avant-GardeFrom EverandRationalizing Culture: IRCAM, Boulez, and the Institutionalization of the Musical Avant-GardeRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- The Sonic Aesthetics of Industrial MusicDocument11 pagesThe Sonic Aesthetics of Industrial MusicNicolas Avila RNo ratings yet

- Michel Chion - Sound - An Acoulogical Treatise (2016, Duke University Press)Document313 pagesMichel Chion - Sound - An Acoulogical Treatise (2016, Duke University Press)SGZ100% (7)

- Sound Matters: The Impact of Technology on Music Consumption in the Early Twentieth CenturyFrom EverandSound Matters: The Impact of Technology on Music Consumption in the Early Twentieth CenturyNo ratings yet

- MicahSilver Figures in Air SmallDocument57 pagesMicahSilver Figures in Air SmallBrice JacksonNo ratings yet

- Peter Manning - Electronic and Computer Music - Background To 1945Document14 pagesPeter Manning - Electronic and Computer Music - Background To 1945Gonzalo Lacruz EstebanNo ratings yet

- Der Klang der Familie: Berlin, Techno and the Fall of the WallFrom EverandDer Klang der Familie: Berlin, Techno and the Fall of the WallRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Pinch 2002 PDFDocument23 pagesPinch 2002 PDFAbel CastroNo ratings yet

- Thinking with Sound: A New Program in the Sciences and Humanities around 1900From EverandThinking with Sound: A New Program in the Sciences and Humanities around 1900No ratings yet

- Sound by Michel ChionDocument28 pagesSound by Michel ChionDuke University Press50% (8)

- Technology or Theology? - Music Beyond TechnologyDocument6 pagesTechnology or Theology? - Music Beyond TechnologyFadel MuhamadNo ratings yet

- Contrechamps ArticleDocument26 pagesContrechamps ArticleJoao CardosoNo ratings yet

- Task 2 AssessmentDocument8 pagesTask 2 AssessmentLewisRichardsonNo ratings yet

- Kraftwerk Counterculture PDFDocument110 pagesKraftwerk Counterculture PDFAnonymous cqsIZ4100% (2)

- University of Illinois Press, Society For Ethnomusicology EthnomusicologyDocument15 pagesUniversity of Illinois Press, Society For Ethnomusicology EthnomusicologyJeffrey GreinerNo ratings yet

- Barry Hi Fi Sound As Spectacle and Sublime, 1950-1961Document41 pagesBarry Hi Fi Sound As Spectacle and Sublime, 1950-1961Ellen SchweitzerNo ratings yet

- Regarding Electronic MusicDocument12 pagesRegarding Electronic MusicMNo ratings yet

- CornettDocument14 pagesCornettnoidontwanna100% (3)

- Glitch music genre origins and techniquesDocument5 pagesGlitch music genre origins and techniquesn_massNo ratings yet

- CUT AND PASTE: COLLAGE AND THE ART OF SOUND - Kevin ConcannonDocument26 pagesCUT AND PASTE: COLLAGE AND THE ART OF SOUND - Kevin ConcannonYotam KadoshNo ratings yet

- Of The: Theodor W. Adorno Thomas Y. LevinDocument9 pagesOf The: Theodor W. Adorno Thomas Y. LevinJeremy DavisNo ratings yet

- IASPMReview BrennanKickitDocument4 pagesIASPMReview BrennanKickitJose Daniel FrancoNo ratings yet

- Early History of Amplified Music Transectorial Innovation and Decentralized DevelopmentDocument9 pagesEarly History of Amplified Music Transectorial Innovation and Decentralized DevelopmentJackNo ratings yet

- Experiment of Progressive RockDocument2 pagesExperiment of Progressive RockLody Makara PutraNo ratings yet

- Review of The Art of Record Production A PDFDocument4 pagesReview of The Art of Record Production A PDFTRSMFNo ratings yet

- The Art of Record V 2 PDFDocument225 pagesThe Art of Record V 2 PDFDavid Csizmadia100% (1)

- Musical Borrowings in The English BaroqueDocument14 pagesMusical Borrowings in The English BaroqueFelipe100% (1)

- Instants Video 2013 EngDocument56 pagesInstants Video 2013 EngNeli RuzicNo ratings yet

- Live Electronics in Performance, Cage's Imaginary LandscapeDocument10 pagesLive Electronics in Performance, Cage's Imaginary LandscapeagusxiaolinNo ratings yet

- Artigo PedroDocument11 pagesArtigo Pedroteresa_meireles_3No ratings yet

- How To Wreck A Nice Beach The Vocoder FRDocument5 pagesHow To Wreck A Nice Beach The Vocoder FRMariano BujacichNo ratings yet

- Eric Hobsbawm - The Age of Extremes (Chapter 17)Document12 pagesEric Hobsbawm - The Age of Extremes (Chapter 17)Sebastián Morales GiraldoNo ratings yet

- Edgar Varese PDFDocument16 pagesEdgar Varese PDFGilson BarbozaNo ratings yet

- A Case Study of The Music IndustryDocument8 pagesA Case Study of The Music IndustrylalaNo ratings yet

- Plunderphonics, or Audio Piracy As A Compositional PrerogativeDocument15 pagesPlunderphonics, or Audio Piracy As A Compositional PrerogativeJorge CardielNo ratings yet

- The Aesthetics of Digital FailureDocument4 pagesThe Aesthetics of Digital FailureKantOLoopNo ratings yet

- Zuberi - Is This The Future - Black Music and Technological DiscourseDocument19 pagesZuberi - Is This The Future - Black Music and Technological DiscoursedevilwidgetNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of Music Consumption How We Got HereDocument27 pagesThe Evolution of Music Consumption How We Got HereAchraf ToumiNo ratings yet

- Kaegi Música y Tecnología PDFDocument21 pagesKaegi Música y Tecnología PDFMagda PoloNo ratings yet

- Gyorgy Ligeti and The Aka Pygmies ProjecDocument36 pagesGyorgy Ligeti and The Aka Pygmies ProjecSupernova SimulationsNo ratings yet

- Review Author(s) : Caroline Rae Review By: Caroline Rae Source: Tempo, New Series, No. 216 (Apr., 2001), Pp. 55-58 Published By: Cambridge University Press Accessed: 04-08-2016 07:15 UTCDocument5 pagesReview Author(s) : Caroline Rae Review By: Caroline Rae Source: Tempo, New Series, No. 216 (Apr., 2001), Pp. 55-58 Published By: Cambridge University Press Accessed: 04-08-2016 07:15 UTCFrancesco DominiciNo ratings yet

- Roads Curtis MicrosoundDocument423 pagesRoads Curtis MicrosoundLorenzo ScandaleNo ratings yet

- Cambridge University Press Popular Music: This Content Downloaded From 45.239.211.74 On Thu, 16 Apr 2020 20:14:50 UTCDocument20 pagesCambridge University Press Popular Music: This Content Downloaded From 45.239.211.74 On Thu, 16 Apr 2020 20:14:50 UTCRoberto GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Rothenbuhler e Peters. Defining PhonographyDocument23 pagesRothenbuhler e Peters. Defining PhonographyCauê MartinsNo ratings yet

- Music. Classicism TeoryDocument9 pagesMusic. Classicism Teorymanolowar13No ratings yet

- Digital Discipline Minimalism in House TechnoDocument9 pagesDigital Discipline Minimalism in House TechnoBen HaguesNo ratings yet

- Mathematical Music From Antiquity To Music AIDocument147 pagesMathematical Music From Antiquity To Music AIRodrigo Carvalho100% (1)

- Australian Electronica HistoryDocument21 pagesAustralian Electronica HistoryandersandNo ratings yet

- Rothenbuhler, E.W. and Peters, J.D. (1997) Defining Phonography PDFDocument23 pagesRothenbuhler, E.W. and Peters, J.D. (1997) Defining Phonography PDFpaologranataNo ratings yet

- Mozart's Viennese Copyists ResearchDocument11 pagesMozart's Viennese Copyists Researchfeinster22No ratings yet

- NICHOLSON Unnaturel TrumpetDocument11 pagesNICHOLSON Unnaturel TrumpetHenri FelixNo ratings yet

- Cross Lowell - Electronic Music 1948-1953Document35 pagesCross Lowell - Electronic Music 1948-1953Olimpia CristeaNo ratings yet

- Bijsterweld Diabolic Symphony 2001Document35 pagesBijsterweld Diabolic Symphony 2001SamuelMartínezNo ratings yet

- Bijsterveld Van Dijck 2009Document220 pagesBijsterveld Van Dijck 2009Pedro Félix100% (1)

- Fassbinder and His Friends Author (S) : Daniel Talbot Source: Moma, Winter - Spring, 1997, No. 24 (Winter - Spring, 1997), Pp. 10-13 Published By: The Museum of Modern ArtDocument5 pagesFassbinder and His Friends Author (S) : Daniel Talbot Source: Moma, Winter - Spring, 1997, No. 24 (Winter - Spring, 1997), Pp. 10-13 Published By: The Museum of Modern ArtJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- Fassbinder's Politics of Despair ExploredDocument25 pagesFassbinder's Politics of Despair ExploredJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- J ctt46mt94 4 PDFDocument33 pagesJ ctt46mt94 4 PDFJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 189.202.196.3 On Mon, 11 Jan 2021 07:31:40 UTCDocument9 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 189.202.196.3 On Mon, 11 Jan 2021 07:31:40 UTCJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 189.202.196.3 On Mon, 11 Jan 2021 07:30:02 UTCDocument19 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 189.202.196.3 On Mon, 11 Jan 2021 07:30:02 UTCJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- Fassbinder's Politics of Despair ExploredDocument25 pagesFassbinder's Politics of Despair ExploredJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- J ctt46mt94 5 PDFDocument29 pagesJ ctt46mt94 5 PDFJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 189.202.196.3 On Mon, 11 Jan 2021 07:24:37 UTCDocument6 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 189.202.196.3 On Mon, 11 Jan 2021 07:24:37 UTCJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 189.202.196.3 On Mon, 11 Jan 2021 07:30:02 UTCDocument19 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 189.202.196.3 On Mon, 11 Jan 2021 07:30:02 UTCJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- Fassbinder and His Friends Author (S) : Daniel Talbot Source: Moma, Winter - Spring, 1997, No. 24 (Winter - Spring, 1997), Pp. 10-13 Published By: The Museum of Modern ArtDocument5 pagesFassbinder and His Friends Author (S) : Daniel Talbot Source: Moma, Winter - Spring, 1997, No. 24 (Winter - Spring, 1997), Pp. 10-13 Published By: The Museum of Modern ArtJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 201.158.189.66 On Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:22:23 UTCDocument15 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 201.158.189.66 On Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:22:23 UTCJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 189.202.196.3 On Mon, 11 Jan 2021 07:30:45 UTCDocument8 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 189.202.196.3 On Mon, 11 Jan 2021 07:30:45 UTCJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 189.202.196.3 On Mon, 11 Jan 2021 07:24:48 UTCDocument7 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 189.202.196.3 On Mon, 11 Jan 2021 07:24:48 UTCJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 189.202.196.3 On Mon, 11 Jan 2021 07:24:42 UTCDocument3 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 189.202.196.3 On Mon, 11 Jan 2021 07:24:42 UTCJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- Romanticizing Rock Music Author(s) : Theodore A. Gracyk Source: The Journal of Aesthetic Education, Summer, 1993, Vol. 27, No. 2 (Summer, 1993), Pp. 43-58 Published By: University of Illinois PressDocument17 pagesRomanticizing Rock Music Author(s) : Theodore A. Gracyk Source: The Journal of Aesthetic Education, Summer, 1993, Vol. 27, No. 2 (Summer, 1993), Pp. 43-58 Published By: University of Illinois PressJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 189.202.196.3 On Mon, 11 Jan 2021 07:31:40 UTCDocument9 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 189.202.196.3 On Mon, 11 Jan 2021 07:31:40 UTCJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- The Flying Slaves: An Essay On Tom Waits Author(s) : Stephan Wackwitz and Nina Sonenberg Source: The Threepenny Review, Winter, 1990, No. 40 (Winter, 1990), Pp. 30-32 Published By: Threepenny ReviewDocument4 pagesThe Flying Slaves: An Essay On Tom Waits Author(s) : Stephan Wackwitz and Nina Sonenberg Source: The Threepenny Review, Winter, 1990, No. 40 (Winter, 1990), Pp. 30-32 Published By: Threepenny ReviewJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 201.158.189.66 On Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:46:33 UTCDocument13 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 201.158.189.66 On Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:46:33 UTCJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument26 pagesPDFJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 201.158.189.66 On Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:23:46 UTCDocument6 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 201.158.189.66 On Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:23:46 UTCJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 201.158.189.66 On Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:46:13 UTCDocument19 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 201.158.189.66 On Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:46:13 UTCJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 201.158.189.66 On Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:31:14 UTCDocument18 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 201.158.189.66 On Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:31:14 UTCJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument26 pagesPDFJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 201.158.189.66 On Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:46:13 UTCDocument19 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 201.158.189.66 On Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:46:13 UTCJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 201.158.189.66 On Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:46:33 UTCDocument13 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 201.158.189.66 On Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:46:33 UTCJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 201.158.189.66 On Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:31:14 UTCDocument18 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 201.158.189.66 On Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:31:14 UTCJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 201.158.189.66 On Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:46:13 UTCDocument19 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 201.158.189.66 On Sun, 22 Nov 2020 08:46:13 UTCJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument26 pagesPDFJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- Why 1955? Explaining The Advent of Rock Music Author(s) : Richard A. Peterson Source: Popular Music, Jan., 1990, Vol. 9, No. 1 (Jan., 1990), Pp. 97-116 Published By: Cambridge University PressDocument21 pagesWhy 1955? Explaining The Advent of Rock Music Author(s) : Richard A. Peterson Source: Popular Music, Jan., 1990, Vol. 9, No. 1 (Jan., 1990), Pp. 97-116 Published By: Cambridge University PressJesús TapiaNo ratings yet

- Yamaha Motif6 Motif7 Motif8Document147 pagesYamaha Motif6 Motif7 Motif8thienhungcapheNo ratings yet

- Drumasonic Quick Start GuideDocument2 pagesDrumasonic Quick Start GuideidscribdgmailNo ratings yet

- In Vitro Blood Gas Analyzers: × 3.0 × 2.85 Inches/22.4 Ounces × 3.4 × 8.5 Inches/ 1.5 Pounds × 12 × 12 Inches/29.5 PoundsDocument8 pagesIn Vitro Blood Gas Analyzers: × 3.0 × 2.85 Inches/22.4 Ounces × 3.4 × 8.5 Inches/ 1.5 Pounds × 12 × 12 Inches/29.5 PoundsMSKNo ratings yet

- D 4557 - 85 (1995) PDFDocument2 pagesD 4557 - 85 (1995) PDFAl7amdlellahNo ratings yet

- Pa3x KORG Service ManualDocument125 pagesPa3x KORG Service Manualiraklitosp100% (1)

- 1.1 - Sampling HandbookDocument28 pages1.1 - Sampling HandbookAndrés Castillo NavarroNo ratings yet

- Lexicon 300 Vers.3 Quick Reference GuideDocument2 pagesLexicon 300 Vers.3 Quick Reference GuideStanleyNo ratings yet

- Making The Beat - Brazilian DrumsDocument20 pagesMaking The Beat - Brazilian DrumsNickNo ratings yet

- JuzisoundDocument55 pagesJuzisoundbata976No ratings yet

- E-Mu Emulator 4k Manual PDFDocument382 pagesE-Mu Emulator 4k Manual PDFthared33No ratings yet