Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Zero 1

Zero 1

Uploaded by

GTOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Zero 1

Zero 1

Uploaded by

GTCopyright:

Available Formats

The history of thermodynamics as a scientific discipline generally begins with Otto von

Guericke who, in 1650, built and designed the world's first vacuum pump and demonstrated

a vacuum using his Magdeburg hemispheres. Guericke was driven to make a vacuum in order to

disprove Aristotle's long-held supposition that 'nature abhors a vacuum'. Shortly after Guericke,

the Anglo-Irish physicist and chemist Robert Boyle had learned of Guericke's designs and, in

1656, in coordination with English scientist Robert Hooke, built an air pump.[17] Using this pump,

Boyle and Hooke noticed a correlation between pressure, temperature, and volume. In

time, Boyle's Law was formulated, which states that pressure and volume are inversely

proportional. Then, in 1679, based on these concepts, an associate of Boyle's named Denis

Papin built a steam digester, which was a closed vessel with a tightly fitting lid that confined

steam until a high pressure was generated.

Later designs implemented a steam release valve that kept the machine from exploding. By

watching the valve rhythmically move up and down, Papin conceived of the idea of a piston and

a cylinder engine. He did not, however, follow through with his design. Nevertheless, in 1697,

based on Papin's designs, engineer Thomas Savery built the first engine, followed by Thomas

Newcomen in 1712. Although these early engines were crude and inefficient, they attracted the

attention of the leading scientists of the time.

The fundamental concepts of heat capacity and latent heat, which were necessary for the

development of thermodynamics, were developed by Professor Joseph Black at the University of

Glasgow, where James Watt was employed as an instrument maker. Black and Watt performed

experiments together, but it was Watt who conceived the idea of the external condenser which

resulted in a large increase in steam engine efficiency.[18] Drawing on all the previous work

led Sadi Carnot, the "father of thermodynamics", to publish Reflections on the Motive Power of

Fire (1824), a discourse on heat, power, energy and engine efficiency. The book outlined the

basic energetic relations between the Carnot engine, the Carnot cycle, and motive power. It

marked the start of thermodynamics as a modern science.[10]

The first thermodynamic textbook was written in 1859 by William Rankine, originally trained as a

physicist and a civil and mechanical engineering professor at the University of Glasgow.[19] The

first and second laws of thermodynamics emerged simultaneously in the 1850s, primarily out of

the works of William Rankine, Rudolf Clausius, and William Thomson (Lord Kelvin).[20]

The foundations of statistical thermodynamics were set out by physicists such as James Clerk

Maxwell, Ludwig Boltzmann, Max Planck, Rudolf Clausius and J. Willard Gibbs.

During the years 1873–76 the American mathematical physicist Josiah Willard Gibbs published a

series of three papers, the most famous being On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous

Substances,[3] in which he showed how thermodynamic processes, including chemical reactions,

could be graphically analyzed, by studying

the energy, entropy, volume, temperature and pressure of the thermodynamic system in such a

manner, one can determine if a process would occur spontaneously.[21] Also Pierre Duhem in the

19th century wrote about chemical thermodynamics.[4] During the early 20th century, chemists

such as Gilbert N. Lewis, Merle Randall,[5] and E. A. Guggenheim[6][7] applied the mathematical

methods of Gibbs to the analysis of chemical processes.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5814)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Interview For CadetsDocument8 pagesInterview For CadetsGlenn Sentorias0% (1)

- Instruction: Se RviceDocument3 pagesInstruction: Se RvicecarlNo ratings yet

- Biology Is The Natural Science That Involves The Study of Life and Living Organisms, IncludingDocument1 pageBiology Is The Natural Science That Involves The Study of Life and Living Organisms, IncludingJejeNo ratings yet

- Seed Flowering Plants Ovary Flowering Seeds Symbiotic Relationship Seed Dispersal Nutrition Agricultural Apple PomegranateDocument1 pageSeed Flowering Plants Ovary Flowering Seeds Symbiotic Relationship Seed Dispersal Nutrition Agricultural Apple PomegranateJejeNo ratings yet

- Parts of Bodies, and The Relation of Heat To Electrical Agency."Document1 pageParts of Bodies, and The Relation of Heat To Electrical Agency."JejeNo ratings yet

- Cell Theory States That The Cell Is The Fundamental Unit of Life, That All Living Things Are Composed ofDocument1 pageCell Theory States That The Cell Is The Fundamental Unit of Life, That All Living Things Are Composed ofJejeNo ratings yet

- Income Taxes Asset Capital Taxes Financial Transaction Sales TaxesDocument1 pageIncome Taxes Asset Capital Taxes Financial Transaction Sales TaxesJejeNo ratings yet

- RightsDocument1 pageRightsJejeNo ratings yet

- Non FoodDocument1 pageNon FoodJejeNo ratings yet

- RytDocument1 pageRytJejeNo ratings yet

- Latin Legal Entity Direct Indirect TaxesDocument1 pageLatin Legal Entity Direct Indirect TaxesJejeNo ratings yet

- European Union Multilateral Agreement On Information Exchange Local Taxation Tax EvasionDocument1 pageEuropean Union Multilateral Agreement On Information Exchange Local Taxation Tax EvasionJejeNo ratings yet

- RightsDocument1 pageRightsJejeNo ratings yet

- Legal Ethical Principles Freedom Entitlement Normative Law Ethics Justice Deontology Civilization Society Culture Social Conflicts Governments Laws MoralityDocument1 pageLegal Ethical Principles Freedom Entitlement Normative Law Ethics Justice Deontology Civilization Society Culture Social Conflicts Governments Laws MoralityJejeNo ratings yet

- Design 1Document21 pagesDesign 1JejeNo ratings yet

- PD Sources in LiteratureDocument3 pagesPD Sources in LiteratureJejeNo ratings yet

- Please Print Name: - Student #Document2 pagesPlease Print Name: - Student #JejeNo ratings yet

- Solutions Notetaking GuideDocument9 pagesSolutions Notetaking GuideJejeNo ratings yet

- Design and Development of Wheel Balancing Machine Experimental Setup IJERTV8IS060197Document5 pagesDesign and Development of Wheel Balancing Machine Experimental Setup IJERTV8IS060197Abdul KurniadiNo ratings yet

- Camshaft Bearings - Remove and Install (SENR5547-04)Document2 pagesCamshaft Bearings - Remove and Install (SENR5547-04)Muhammad Danang MadhribieNo ratings yet

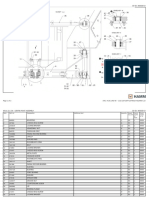

- FIG FIG F4300W32.051 F4300W32.051 FIG Fig No. NO. F4350-51A0 F4350-51A0 TRANSMISSION Transmission Transmission Transmission Case CaseDocument2 pagesFIG FIG F4300W32.051 F4300W32.051 FIG Fig No. NO. F4350-51A0 F4350-51A0 TRANSMISSION Transmission Transmission Transmission Case CaseIvan PalominoNo ratings yet

- 005 PT - SICILSALDO S.P.A. - Parallel To The North - Bulgaria (ORAT - BULTEST) - Rev.03Document10 pages005 PT - SICILSALDO S.P.A. - Parallel To The North - Bulgaria (ORAT - BULTEST) - Rev.03irfanNo ratings yet

- EC - I MCQ Question Bank On Unit 5 & 6-1Document12 pagesEC - I MCQ Question Bank On Unit 5 & 6-1Harshad jambhaleNo ratings yet

- Level Measurement Level MeasurementDocument6 pagesLevel Measurement Level MeasurementMourougapragash SubramanianNo ratings yet

- IENCSEPRO0007-2 - General Leak Test Procedure PDFDocument9 pagesIENCSEPRO0007-2 - General Leak Test Procedure PDFCatalinNo ratings yet

- Reinforcement DataDocument40 pagesReinforcement DataerattakoyaNo ratings yet

- 05 Selection of Tightening ToolsDocument8 pages05 Selection of Tightening ToolsAniigiselaNo ratings yet

- Life Cycle Support: VariableDocument10 pagesLife Cycle Support: VariableJitendra JhaNo ratings yet

- Piping Q & ADocument8 pagesPiping Q & AvenkateshNo ratings yet

- 01 Rolamento REF.1234986Document3 pages01 Rolamento REF.1234986Ivan ArenaNo ratings yet

- Unit - Iv Design of Energy Storing Elements: Prepared by R. Sendil KumarDocument61 pagesUnit - Iv Design of Energy Storing Elements: Prepared by R. Sendil KumarTalha AbbasiNo ratings yet

- Millingmixing EnglishDocument14 pagesMillingmixing Englishhicham boutoucheNo ratings yet

- Daewoo S225LCV Hydraulic ExcavatorDocument3 pagesDaewoo S225LCV Hydraulic Excavatordidikhartadi100% (1)

- Daikin VRV SheetDocument6 pagesDaikin VRV SheetSridhar ReddyNo ratings yet

- ECDocument12 pagesECanggieNo ratings yet

- 2010 KyronDocument312 pages2010 KyronAlex VianaNo ratings yet

- F-Rock Mass ClassificationDocument9 pagesF-Rock Mass ClassificationAbdur RaoufNo ratings yet

- Vector Solved PDFDocument27 pagesVector Solved PDFtopherskiNo ratings yet

- Qa - 4 Component Installation Sheet - HD785-7Document4 pagesQa - 4 Component Installation Sheet - HD785-7Fajar SuryaNo ratings yet

- Design of Steel StructuresDocument48 pagesDesign of Steel Structuressudhakarummadi87% (15)

- Foundations DesignDocument43 pagesFoundations DesignNaresh NarineNo ratings yet

- Separation III: Chapter 2: DryingDocument98 pagesSeparation III: Chapter 2: DryingSaranya DeviNo ratings yet

- Plumbing Board Examination ReviewerDocument23 pagesPlumbing Board Examination ReviewerAllen EspeletaNo ratings yet

- Karcher K2400HH Pressure WasherDocument12 pagesKarcher K2400HH Pressure Washeralgae737No ratings yet

- Руководство по ремонту АКПП 5HP19Document40 pagesРуководство по ремонту АКПП 5HP19mor3danNo ratings yet

- Welding ElectrodesDocument7 pagesWelding ElectrodesBalakumar0% (1)