Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Behaviourism: B.F. Skinner Operant Conditioning Laboratory

Uploaded by

İffet DemirciOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Behaviourism: B.F. Skinner Operant Conditioning Laboratory

Uploaded by

İffet DemirciCopyright:

Available Formats

Behaviourism

Beginning in the 1930s, behaviourism flourished in the United

States, with B.F. Skinner leading the way in demonstrating the

power of operant conditioning through reinforcement. Behaviourists

in university settings conducted experiments on the conditions

controlling learning and “shaping” behaviour through

reinforcement, usually working with laboratory animals such as rats

and pigeons. Skinner and his followers explicitly excluded mental

life, viewing the human mind as an impenetrable “black box,” open

only to conjecture and speculative fictions. Their work showed that

social behaviour is readily influenced by manipulating

specific contingencies and by changing the consequences or

reinforcement (rewards) to which behaviour leads in different

situations. Changes in those consequences can modify behaviour in

predictable stimulus-response (S-R) patterns. Likewise, a wide

range of emotions, both positive and negative, may be acquired

through processes of conditioning and can be modified by applying

the same principles.

Freud And His Followers

Concurrently, in a curious juxtaposition, the psychoanalytic theories

and therapeutic practices developed by the Vienna-trained

physician Sigmund Freud and his many disciples—beginning early

in the 20th century and enduring for many decades—were

undermining the traditional view of human nature as essentially

rational. Freudian theory made reason secondary: for Freud,

the unconscious and its often socially unacceptable irrational

motives and desires, particularly the sexual and aggressive, were the

driving force underlying much of human behaviour and mental

illness. Making the unconscious conscious became the therapeutic

goal of clinicians working within this framework.

Freud proposed that much of what humans feel, think, and do is

outside awareness, self-defensive in its motivations, and

unconsciously determined. Much of it also reflects conflicts

grounded in early childhood that play out in complex patterns of

seemingly paradoxical behaviours and symptoms. His followers,

the ego psychologists, emphasized the importance of the higher-

order functions and cognitive processes (e.g.,

competence motivation, self-regulatory abilities) as well as the

individual’s psychological defense mechanisms. They also shifted

their focus to the roles of interpersonal relations and of secure

attachment in mental health and adaptive functioning, and they

pioneered the analysis of these processes in the clinical setting.

The learning theory dominant in the first half of the 20th Century was

behaviourism. Throughout the 1950s and 60s behaviourism remained influential,

although since that time new theories have begun to make substantial inroads in

general acceptance. Behaviourism is an approach to psychology and learning that

emphasizes observable measurable behaviour. The behaviourist theory of animal

and human learning focuses only on objectively observable behaviours and

discounts mental activities. Behaviour theorists define learning as a more or less

permanent change in behaviour. In behaviourism, the learner is viewed as

passively adapting to their environment. Two of the most famous experiments upon

which proof of learning is based are the "Dog Salivation Experiment" by Ivan

Petrovich Pavlov and the " Skinner Box" experiment with pigeons by B.F. Skinner.

"Give me a dozen healthy infants, well informed, and my own specified world to

bring them up in and I'll guarantee to take anyone at random and train him to

become any type of specialist I might select--doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief;

and yes, even beggar-man and thief, regardless of his talents, penchants,

tendencies, abilities, vocations, and race of his ancestors." John Watson

Behaviourism is derived from the belief that free will is an illusion. According

to a pure behaviourist, human beings are shaped entirely by their external

environment. Alter a person's environment, and you will alter his or her thoughts,

feelings, and behaviour. Provide positive reinforcement whenever students perform

a desired behaviour, and soon they will learn to perform the behaviour on their

own.

The behaviourists tried to explain learning without referring to mental processes.

The focus was on observable behaviour and how an organism adapts to the

environment. The famous "Dog-Salivation-Experiment" by Ivan Petrovich Pavlov

where he makes dogs salivate at the sound of a bell and later experiments

by Burhus Frederic Skinner (Refere nce date; 25th of April 1998) with pigeons in

the so called "Skinner Box" are very famous examples of behaviouristic learning

experiments. Despite these very "low-level" learning experiments focusing largely

on reflexes, the behaviouristic theories have been generalized to many higher level

functions as well.

The behaviorist movement began in 1913 when John Watson wrote an article entitled

'Psychology as the behaviorist views it,' which set out a number of underlying assumptions

regarding methodology and behavioral analysis:

All behavior is learned from the environment:

Behaviorism emphasizes the role of environmental factors in influencing behavior, to

the near exclusion of innate or inherited factors. This amounts essentially to a focus

on learning.

We learn new behavior through classical or operant conditioning (collectively known

as 'learning theory').

Therefore, when born our mind is 'tabula rasa' (a blank slate

Psychology should be seen as a science:

Theories need to be supported by empirical data obtained through careful and

controlled observation and measurement of behavior. Watson (1913) stated that:

'Psychology as a behaviorist views it is a purely objective experimental branch of

natural science. Its theoretical goal is … prediction and control.' (p. 158).

The components of a theory should be as simple as possible. Behaviorists propose

the use of operational definitions (defining variables in terms of observable,

measurable events).

Behaviorism is primarily concerned with observable

behavior, as opposed to internal events like thinking and

emotion:

While behaviorists often accept the existence of cognitions and emotions, they prefer

not to study them as only observable (i.e., external) behavior can be objectively and

scientifically measured.

Therefore, internal events, such as thinking should be explained through behavioral

terms (or eliminated altogether).

Psychology should be seen as a science, to be studied in a scientific manner.

Behaviorism is primarily concerned with observable behavior, as opposed to internal

events like thinking.

Behavior is the result of stimulus–response (i.e., all behavior, no matter how

complex, can be reduced to a simple stimulus – response features).

Behavior is determined by the environment (e.g., conditioning, nurture).

Ignores mediational processes

Ignores biology (e.g., testosterone)

Too deterministic (little free-will)

Experiments – low ecological validity

Humanism – can’t compare animals to humans

Reductionist

Behaviorism has experimental support: Pavlov showed that classical conditioning

leads to learning by association. Watson and Rayner showed that phobias can be

learnt through classical conditioning in the “little Albert” experiment.

An obvious advantage of behaviorism is its ability to define behavior clearly and to

measure changes in behavior. According to the law of parsimony, the fewer

assumptions a theory makes, the better and the more credible it is. Behaviorism,

therefore, looks for simple explanations of human behavior from a very scientific

standpoint.

However, behaviorism only provides a partial account of human behavior, that which

can be objectively viewed. Important factors like emotions, expectations, higher-level

motivation are not considered or explained. Accepting a behaviorist explanation

could prevent further research from other perspective that could uncover important

factors.

Many of the experiments carried out were done on animals; we are different

cognitively and physiologically, humans have different social norms and moral values

these mediate the effects of the environment therefore we might behave differently

from animals so the laws and principles derived from these experiments might apply

more to animals than to humans.

In addition, humanism (e.g., Carl Rogers) rejects the scientific method of using

experiments to measure and control variables because it creates an artificial

environment and has low ecological validity.

Humanistic psychology also assumes that humans have free will (personal agency)

to make their own decisions in life and do not follow the deterministic laws of science.

Humanism also rejects the nomothetic approach of behaviorism as they view

humans as being unique and believe humans cannot be compared with animals (who

aren’t susceptible to demand characteristics). This is known as an idiographic

approach.

The psychodynamic approach (Freud) criticizes behaviorism as it does not take into

account the unconscious mind’s influence on behavior, and instead focuses on

externally observable behavior. Freud also rejects the idea that people are born a

blank slate (tabula rasa) and states that people are born with instincts (e.g., eros and

thanatos).

Biological psychology states that all behavior has a physical/organic cause. They emphasize

the role of nature over nurture. For example, chromosomes and hormones (testosterone)

influence our behavior too, in addition to the environment.

Cognitive psychology states that mediational processes occur between stimulus and

response, such as memory, thinking, problem-solving, etc.

Despite these criticisms, behaviorism has made significant contributions to

psychology. These include insights into learning, language development, and moral

and gender development, which have all been explained in terms of conditioning.

The contribution of behaviorism can be seen in some of its practical

applications. Behavior therapy and behavior modification represent one of the major

approaches to the treatment of abnormal behavior and are readily used in clinical

psychology.

You might also like

- Summary Of "Psychology 1850-1950" By Michel Foucault: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESFrom EverandSummary Of "Psychology 1850-1950" By Michel Foucault: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESNo ratings yet

- BehaviorismDocument13 pagesBehaviorismKavya tripathiNo ratings yet

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Behavioral Phenomena Associated with Instrumental/Operational ConditioningFrom EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Behavioral Phenomena Associated with Instrumental/Operational ConditioningNo ratings yet

- Behaviorism Approach ExplainedDocument5 pagesBehaviorism Approach ExplainedMegumi Diana Inukai CotaNo ratings yet

- Behaviorial Psychology Study Material Part 2Document10 pagesBehaviorial Psychology Study Material Part 2Anushka Ridhi HiraNo ratings yet

- BehaviorismDocument6 pagesBehaviorismamsaldi kristian100% (2)

- Behaviorist ApproachDocument7 pagesBehaviorist Approachapple macNo ratings yet

- 4440 1602118453Document12 pages4440 1602118453Chasalle Joie GDNo ratings yet

- Behaviorist ApproachDocument3 pagesBehaviorist ApproachZarghonaNo ratings yet

- BehaviorismDocument21 pagesBehaviorismnigel989No ratings yet

- Basic Assumptions: Comparative PsychologyDocument6 pagesBasic Assumptions: Comparative PsychologyMark Anthony RaymundoNo ratings yet

- Ulman, JD - Behaviorology - The - Natural - Science - of - Behavior PDFDocument11 pagesUlman, JD - Behaviorology - The - Natural - Science - of - Behavior PDFAraliIbethReymundoGarciaNo ratings yet

- Behavior TheoryDocument22 pagesBehavior TheorySharifahBaizuraSyedBakarNo ratings yet

- BehaviourismDocument3 pagesBehaviourismSabrina AdanNo ratings yet

- 1) History of BehaviorismDocument9 pages1) History of BehaviorismPriti PratikshyaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Psychology - KarolDocument50 pagesIntroduction To Psychology - KarolAgyekum PaulNo ratings yet

- Behaviorism Psychology (1)Document7 pagesBehaviorism Psychology (1)A PluswritersNo ratings yet

- Learning TheoryDocument23 pagesLearning TheorySabrina ZulaikhaNo ratings yet

- BehaviorismDocument8 pagesBehaviorismjal67No ratings yet

- BehaviorismDocument5 pagesBehaviorismytsotetsi67No ratings yet

- BehaviorismDocument9 pagesBehaviorismJie FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Course Code 8615 Assignment No. 2 Q.1 Explain Behavioral Systems Analysis (BSA) and Its Role To Improve Individual and System PerformanceDocument15 pagesCourse Code 8615 Assignment No. 2 Q.1 Explain Behavioral Systems Analysis (BSA) and Its Role To Improve Individual and System PerformanceAneel Hussain 715-FBAS/MSMA/F20No ratings yet

- Behaviorism (Also Called Learning Perspective) Is A Philosophy ofDocument20 pagesBehaviorism (Also Called Learning Perspective) Is A Philosophy ofARNOLDNo ratings yet

- Behavioral PsychologyDocument2 pagesBehavioral PsychologyGerick Dave Monencillo VenderNo ratings yet

- BehaviorismDocument10 pagesBehaviorismAbindra Raj Dangol100% (2)

- What is BehaviorismDocument3 pagesWhat is BehaviorismMc ReshNo ratings yet

- Behaviorism Explained Through Key Theorists and ConceptsDocument11 pagesBehaviorism Explained Through Key Theorists and ConceptsYuriatson JubhariNo ratings yet

- Behaviorist Learning Theory ExplainedDocument7 pagesBehaviorist Learning Theory ExplainedDawn NahNo ratings yet

- History of PsychologyDocument5 pagesHistory of PsychologyNesa Quirino LongakitNo ratings yet

- Assignment 6501Document35 pagesAssignment 6501Hafiz NasrullahNo ratings yet

- Psychological Foundations of Education-WrittenDocument9 pagesPsychological Foundations of Education-WrittenQuincy Mae MontereyNo ratings yet

- Schools of PsychologyDocument6 pagesSchools of PsychologyMadhavi Gundabattula100% (1)

- Understanding PsychologyDocument49 pagesUnderstanding Psychologyfarhan badshahNo ratings yet

- Major Fields of PsychologyDocument4 pagesMajor Fields of PsychologyKailashNo ratings yet

- Behaviorism Overview ExplainedDocument1 pageBehaviorism Overview ExplainedAvel ObligadoNo ratings yet

- Industrial and Organizational PsychologyDocument5 pagesIndustrial and Organizational PsychologyMohit JainNo ratings yet

- Behavioral Approach-1Document34 pagesBehavioral Approach-1Yusuf ÇalışmazNo ratings yet

- Behaviorism - Simply Psychology PDFDocument4 pagesBehaviorism - Simply Psychology PDFChlouie Jean PasionNo ratings yet

- Psychology PerspectivesDocument19 pagesPsychology PerspectivesMarion Nicole Dela VegaNo ratings yet

- Behaviorism (Foundations and Nature of Guidance)Document28 pagesBehaviorism (Foundations and Nature of Guidance)Joseph Alvin Peña100% (1)

- Research On BehaviorismDocument4 pagesResearch On BehaviorismEnzoe's GreatfindsNo ratings yet

- Q. 1 Explain The Term Psychology. Critically Discuss The History of Psychology. AnswerDocument13 pagesQ. 1 Explain The Term Psychology. Critically Discuss The History of Psychology. AnswerahsanNo ratings yet

- A. Introduction To PsychologyDocument13 pagesA. Introduction To PsychologyTatiana Jewel Dela RosaNo ratings yet

- Theoritical Frame WorkDocument3 pagesTheoritical Frame WorkZainal Abd AzizNo ratings yet

- Behaviorism TheoryDocument30 pagesBehaviorism TheoryAthena Villanueva100% (2)

- The Perspectives of Watson, Skinner and Tolman FinalDocument9 pagesThe Perspectives of Watson, Skinner and Tolman Finalmotivated165No ratings yet

- Chapter 2: Behaviorist Approach: Learning and Teaching: Theories, Approaches and ModelsDocument12 pagesChapter 2: Behaviorist Approach: Learning and Teaching: Theories, Approaches and ModelspilotiraniNo ratings yet

- Behaviorist ApproachDocument2 pagesBehaviorist ApproachFritzie Denila-VeracityNo ratings yet

- Psychology Homework 16 Marker - AMDocument2 pagesPsychology Homework 16 Marker - AMAmna MohamadNo ratings yet

- Behaviorism: Operant Conditioning (B.F. Skinner) OverviewDocument3 pagesBehaviorism: Operant Conditioning (B.F. Skinner) OverviewMichelle Sajonia RafananNo ratings yet

- Psychology As A ScienceDocument8 pagesPsychology As A Sciencebahrian09No ratings yet

- Structuralism Grew Out of The Work of James, Wundt, and Their Associates. TheseDocument4 pagesStructuralism Grew Out of The Work of James, Wundt, and Their Associates. TheseMarie LopezNo ratings yet

- LEARNING PSYCHOLOGYDocument7 pagesLEARNING PSYCHOLOGYOwolabi PetersNo ratings yet

- Learning, Learning Theories: What Is Theory?Document7 pagesLearning, Learning Theories: What Is Theory?anon-568442No ratings yet

- Learning Theories of PersonalityDocument13 pagesLearning Theories of Personalitypavitra_madhusudanNo ratings yet

- Behaviorsm MooreDocument17 pagesBehaviorsm MooreErwin Agustin RamilNo ratings yet

- Psychology Notes: Introduction and HistoryDocument266 pagesPsychology Notes: Introduction and HistoryTanay SinghNo ratings yet

- Psych-Unit-1-Targets - Google DriveDocument11 pagesPsych-Unit-1-Targets - Google Driveapi-246075985No ratings yet

- Psychology As A ScienceDocument4 pagesPsychology As A ScienceElijah HansonNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Learning TheoriesDocument3 pagesIntroduction to Learning TheoriesAfricano Kyla100% (1)

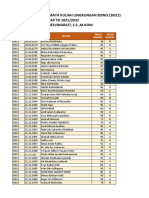

- 10 C Ikinci SınavDocument3 pages10 C Ikinci Sınavİffet DemirciNo ratings yet

- English ExercisesDocument3 pagesEnglish Exercisesİffet DemirciNo ratings yet

- BağlaçlarDocument15 pagesBağlaçlarİffet DemirciNo ratings yet

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- PRESENT tENSEDocument1 pagePRESENT tENSEİffet DemirciNo ratings yet

- All Summer in A Day" by Ray Bradbury: I Think The Sun Is A Flower, That Blooms For Just One HourDocument3 pagesAll Summer in A Day" by Ray Bradbury: I Think The Sun Is A Flower, That Blooms For Just One Hourİffet DemirciNo ratings yet

- Simple Past Vs Present PerfectDocument3 pagesSimple Past Vs Present Perfectjulyanamci100% (1)

- Past Continuous Tenseaffirmative Sentences With Grammar Key BWDocument5 pagesPast Continuous Tenseaffirmative Sentences With Grammar Key BWJose Angel Dusantoy0% (1)

- A) Change The Following Affirmative Sentences Into Negative - Aşağıdaki Cümleleri Olumsuz YapDocument2 pagesA) Change The Following Affirmative Sentences Into Negative - Aşağıdaki Cümleleri Olumsuz Yapİffet DemirciNo ratings yet

- Grammar exercises with questions and negativesDocument2 pagesGrammar exercises with questions and negativesİffet DemirciNo ratings yet

- Yds Sorulari 1995 2005 CompressDocument467 pagesYds Sorulari 1995 2005 Compressİffet DemirciNo ratings yet

- Yds Sorulari 1995 2005 CompressDocument467 pagesYds Sorulari 1995 2005 Compressİffet DemirciNo ratings yet

- TheWorldofCrossStitching 20201030 Christmas2020 UserUpload Net PDFDocument100 pagesTheWorldofCrossStitching 20201030 Christmas2020 UserUpload Net PDFİffet Demirci100% (7)

- A) Change The Following Affirmative Sentences Into Negative - Aşağıdaki Cümleleri Olumsuz YapDocument2 pagesA) Change The Following Affirmative Sentences Into Negative - Aşağıdaki Cümleleri Olumsuz Yapİffet DemirciNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary Test 2 1) As A Director, He Added An Element of - and Mystery To His Films - That's Why His Films Are Top-GrossingDocument1 pageVocabulary Test 2 1) As A Director, He Added An Element of - and Mystery To His Films - That's Why His Films Are Top-Grossingİffet DemirciNo ratings yet

- Soils: Colloids Are Small Soil Particles. Their Properties and Influences On Soil AreDocument2 pagesSoils: Colloids Are Small Soil Particles. Their Properties and Influences On Soil Areİffet DemirciNo ratings yet

- Learn Present Continuous TenseDocument3 pagesLearn Present Continuous TenseAnn SchwartzNo ratings yet

- Soils: Colloids Are Small Soil Particles. Their Properties and Influences On Soil AreDocument2 pagesSoils: Colloids Are Small Soil Particles. Their Properties and Influences On Soil Areİffet DemirciNo ratings yet

- Family, Descriptions and To Be GrammarDocument9 pagesFamily, Descriptions and To Be Grammarİffet DemirciNo ratings yet

- Pretty in Pink!: Great Gift IdeasDocument92 pagesPretty in Pink!: Great Gift Ideasİffet DemirciNo ratings yet

- 1-2. Ve 3. Halleri PDFDocument2 pages1-2. Ve 3. Halleri PDFMehmet DemirNo ratings yet

- Fill in The Gaps With The Past Perfect of The Verbs Given. 1Document1 pageFill in The Gaps With The Past Perfect of The Verbs Given. 1Karen CamargoNo ratings yet

- Test Present-Simple PDFDocument2 pagesTest Present-Simple PDFdetroitdoggNo ratings yet

- Simple Past Vs Present PerfectDocument3 pagesSimple Past Vs Present Perfectjulyanamci100% (1)

- What Is Psychology?: The Beginnings of Psychology As A DisciplineDocument5 pagesWhat Is Psychology?: The Beginnings of Psychology As A Disciplineİffet DemirciNo ratings yet

- B Dialogues Everyday Conversations English LODocument72 pagesB Dialogues Everyday Conversations English LOluxiphe7No ratings yet

- Past Simple Irregular Verbs Error Correction and Scaffolding Techniques Tips A - 13985Document2 pagesPast Simple Irregular Verbs Error Correction and Scaffolding Techniques Tips A - 13985İffet DemirciNo ratings yet

- Events Affirmative: Past Perfect Past SimpleDocument1 pageEvents Affirmative: Past Perfect Past Simpleİffet DemirciNo ratings yet

- Present Simple Tense Fun Activities Games Grammar Drills Grammar Guides - 12655Document3 pagesPresent Simple Tense Fun Activities Games Grammar Drills Grammar Guides - 12655Ochi Mochi WhiteNo ratings yet

- 01EC6218 Soft Computing Module-I: Fuzzy Logic: Dr. Pradeep R. Associate Professor GEC, Bartonhill Pradeep@cet - Ac.inDocument103 pages01EC6218 Soft Computing Module-I: Fuzzy Logic: Dr. Pradeep R. Associate Professor GEC, Bartonhill Pradeep@cet - Ac.inayshNo ratings yet

- Hawk Roosting Analysis: How the Poem Conveys the Hawk's God-like PowerDocument12 pagesHawk Roosting Analysis: How the Poem Conveys the Hawk's God-like PowermindlessarienNo ratings yet

- Balance Scorecard Approach To Project Management LeadershipDocument11 pagesBalance Scorecard Approach To Project Management LeadershipOsama JamranNo ratings yet

- SI012 NILAI LINGKUNGAN BISNIS GENAP NETCI 2021 2022 SI012 (Daak)Document4 pagesSI012 NILAI LINGKUNGAN BISNIS GENAP NETCI 2021 2022 SI012 (Daak)Evan RaihanNo ratings yet

- Types of CultureDocument3 pagesTypes of CultureTony StarkNo ratings yet

- DevetakR InternationalRelationsMeets CriticalTheory PDFDocument36 pagesDevetakR InternationalRelationsMeets CriticalTheory PDFRafael Piñeros AyalaNo ratings yet

- Artikel Anton Banjar S2Document26 pagesArtikel Anton Banjar S2mutiara abadiNo ratings yet

- First Language Acquisition InsightsDocument19 pagesFirst Language Acquisition InsightsStiven AvilaNo ratings yet

- A Faith That Helps Me Filter What I Say: Message NotesDocument3 pagesA Faith That Helps Me Filter What I Say: Message NotesmesunoScribdNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To The Higher Triad Meditation Practice PDFDocument11 pagesAn Introduction To The Higher Triad Meditation Practice PDFThigpen FockspaceNo ratings yet

- What Is StorytellingDocument8 pagesWhat Is Storytellingmasmuhul100% (1)

- MGMT3004 Wk4 230313Document39 pagesMGMT3004 Wk4 230313LeeNo ratings yet

- Research Methodology in Social SciencesDocument30 pagesResearch Methodology in Social SciencesNabiha FatimaNo ratings yet

- AIDA Model Explained: Attracting Attention, Building Interest and Driving Desire in Personal SellingDocument6 pagesAIDA Model Explained: Attracting Attention, Building Interest and Driving Desire in Personal SellingAnas KamranNo ratings yet

- RPH Written ReportDocument6 pagesRPH Written ReportAndrei Louie LugtuNo ratings yet

- Philosophical & Sociological Foundation - 301Document6 pagesPhilosophical & Sociological Foundation - 301Tirtharaj DhunganaNo ratings yet

- Humanistic Geography With NotesDocument20 pagesHumanistic Geography With NotesSean Sheehe100% (1)

- How to use backshift in reported speechDocument3 pagesHow to use backshift in reported speechNiuz Ax100% (1)

- Negative Online Reviews of Popular Products: Understanding The Effects of Review Proportion and Quality On Consumers' Attitude and Intention To BuyDocument29 pagesNegative Online Reviews of Popular Products: Understanding The Effects of Review Proportion and Quality On Consumers' Attitude and Intention To BuyJihan KhazimahNo ratings yet

- Virginia Woolf's characters exploredDocument2 pagesVirginia Woolf's characters exploredTijana RadisavljevicNo ratings yet

- Planes of AnalysisDocument3 pagesPlanes of AnalysisSHIELANo ratings yet

- V20 Lore of The Bloodlines (11056187) PDFDocument103 pagesV20 Lore of The Bloodlines (11056187) PDFMichael Lennon de Moura98% (48)

- Lust IfDocument8 pagesLust Iferic gabNo ratings yet

- Courtship, adjustments, goals, religion in marriageDocument2 pagesCourtship, adjustments, goals, religion in marriageNyl NylNo ratings yet

- Ardichvili Manderscheid 2008 Emerging Practices in Leadership Development An IntroductionDocument13 pagesArdichvili Manderscheid 2008 Emerging Practices in Leadership Development An Introductionraki090No ratings yet

- 95 HW 2 S19 - 2 PDFDocument5 pages95 HW 2 S19 - 2 PDFJoshua MacaldoNo ratings yet

- Third Quarter English 6: Encircle The Meaning of The Underlined WordDocument5 pagesThird Quarter English 6: Encircle The Meaning of The Underlined WordShiera Mae Labial LangeNo ratings yet

- Epicureanism Stoicism and Neo PlatonismDocument17 pagesEpicureanism Stoicism and Neo PlatonismJor GarciaNo ratings yet

- Fantasy Addiction - SLAADocument6 pagesFantasy Addiction - SLAAabdirahmana62No ratings yet

- Maths 6.1 PDFDocument3 pagesMaths 6.1 PDFSuki LeungNo ratings yet

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionFrom EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (402)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (78)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeNo ratings yet

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityFrom EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsFrom EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo ratings yet

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsFrom EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (169)

- How to Talk to Anyone: Learn the Secrets of Good Communication and the Little Tricks for Big Success in RelationshipFrom EverandHow to Talk to Anyone: Learn the Secrets of Good Communication and the Little Tricks for Big Success in RelationshipRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1135)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsFrom EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- The Bridesmaid: The addictive psychological thriller that everyone is talking aboutFrom EverandThe Bridesmaid: The addictive psychological thriller that everyone is talking aboutRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (130)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaFrom EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Briefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndFrom EverandBriefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndNo ratings yet

- Summary of The Art of Seduction by Robert GreeneFrom EverandSummary of The Art of Seduction by Robert GreeneRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (46)

- How to Walk into a Room: The Art of Knowing When to Stay and When to Walk AwayFrom EverandHow to Walk into a Room: The Art of Knowing When to Stay and When to Walk AwayRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessFrom EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (328)

- Summary: I'm Glad My Mom Died: by Jennette McCurdy: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: I'm Glad My Mom Died: by Jennette McCurdy: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Techniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementFrom EverandTechniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (40)

- The Ultimate Guide To Memory Improvement TechniquesFrom EverandThe Ultimate Guide To Memory Improvement TechniquesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (34)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryFrom EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (44)

- The Waitress: The gripping, edge-of-your-seat psychological thriller from the bestselling author of The BridesmaidFrom EverandThe Waitress: The gripping, edge-of-your-seat psychological thriller from the bestselling author of The BridesmaidRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (65)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.From EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (110)

- The Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsFrom EverandThe Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsNo ratings yet

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)