Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chimpanzees Are Rational Maximizers in An Ultimatum Game

Chimpanzees Are Rational Maximizers in An Ultimatum Game

Uploaded by

Leonardo SimonciniOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Chimpanzees Are Rational Maximizers in An Ultimatum Game

Chimpanzees Are Rational Maximizers in An Ultimatum Game

Uploaded by

Leonardo SimonciniCopyright:

Available Formats

REPORTS

sensitive to unfairness and punish proposers who

Chimpanzees Are Rational Maximizers make inequitable offers by rejecting those offers

at a cost to themselves, and knowing this, pro-

in an Ultimatum Game posers make strategic offers that are less likely

to be refused.

Keith Jensen,* Josep Call, Michael Tomasello The ultimatum game has been used in

dozens, possibly hundreds of studies, including

Traditional models of economic decision-making assume that people are self-interested rational various human cultures (11) and children (12).

maximizers. Empirical research has demonstrated, however, that people will take into account Testing the ultimatum game on other species

the interests of others and are sensitive to norms of cooperation and fairness. In one of the most would be an important contribution to the de-

robust tests of this finding, the ultimatum game, individuals will reject a proposed division of a bate on the evolution and possible uniqueness of

monetary windfall, at a cost to themselves, if they perceive it as unfair. Here we show that in an human cooperation (6). Chimpanzees are our

ultimatum game, humans’ closest living relatives, chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), are rational closest extant relatives and engage in cooperative

maximizers and are not sensitive to fairness. These results support the hypothesis that other- behavior such as group hunting, coalitionary

regarding preferences and aversion to inequitable outcomes, which play key roles in human social aggression, and territorial patrols (13). Further-

organization, distinguish us from our closest living relatives. more, in experiments they have been shown to

coordinate their behavior (14) and to provide

help (15, 16). However, there is ongoing debate

umans are able to live in very large some degree, have concern for outcomes and about whether chimpanzees are sensitive to, and

H groups and to cooperate with unrelated

individuals whom they expect never to

behaviors affecting others (other-regarding pref-

erences) (4) as well as a general concern for

tolerant of, unfairness (17) or whether they

simply attend to their own expectations with no

Downloaded from http://science.sciencemag.org/ on October 6, 2020

encounter again, conditions that make the stan- norms of fairness (7, 8). regard for what others receive (18). Additionally,

dard mechanisms for cooperation unlikely (1), The benchmark test for examining sensitivity experiments have failed to reveal other-regarding

namely kin selection (2) and reciprocal altruism to fairness and other-regarding preferences is the preferences when food was involved (19, 20)

(3). Nevertheless, people help others, sometimes ultimatum game (9). In the standard version of other than to punish direct theft (21). Having

at great personal cost. But people are not ob- the game, two anonymous individuals are as- chimpanzees play the ultimatum game would

ligate altruists; they do not tolerate abuse of their signed the roles of proposer and responder. The address these conflicting findings on fairness and

generosity. Not only will they punish or shun proposer is offered a sum of money and can negative reciprocity and allow direct compar-

individuals who free-ride or exploit them, they decide whether to divide this windfall with the isons to humans.

will do so even if they themselves do not bene- responder. The crucial feature of the ultimatum In the current study, we tested chimpanzees

fit from correcting the behavior of norm viola- game is that the responder can accept or reject in a mini-ultimatum game. The mini-ultimatum

tors (4). The willingness both to cooperate and the proposer’s offer. If the responder accepts it, game is a reduced form of the ultimatum game

to punish noncooperators has been termed strong both players receive the proposed division; if the in which proposers are given a choice between

reciprocity (5) and has been claimed to be responder rejects it, both get nothing. The ca- making one of two pre-set offers which the

uniquely human (6). To cooperate in these ways, nonical economic model of pure self-interest responder can then accept or reject (22). In one

humans must be more than self-regarding ratio- predicts that the proposer will offer the smallest such study (23), there were four different games.

nal decision-makers; they must also, at least to share possible and that the responder will accept In all games, the proposer had as one option an

any nonzero offer. This is not what happens. amount that would typically be rejected by a

Although the specifics vary across culture and human responder as unfair, namely 80% for the

Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Deutscher setting, the basic finding is that proposers proposer and 20% for the responder (8/2 offer;

Platz 6, D-04103, Leipzig, Germany. typically make offers of 40 to 50% and the proposer received the amount to the left of

*To whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: responders routinely reject offers under 20% the slash and the responder received the amount

jensen@eva.mpg.de (10). These findings suggest that responders are to the right). In the 5/5 (fair) game, the proposer

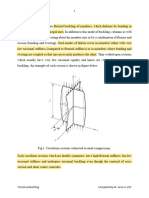

A B C

food dish divider

tray

rope ends

Proposer rods

Responder

Fig. 1. Illustration of the testing environment. The proposer, who makes the the proposer draws one of the baited trays halfway toward the two subjects.

first choice, sits to the responder’s left. The apparatus, which has two sliding (B) The responder can then pull the attached rod, now within reach, to bring

trays connected by a single rope, is outside of the cages. (A) By first sliding a the proposed food tray to the cage mesh so that (C) both subjects can eat

Plexiglas panel (not shown) to access one rope end and by then pulling it, from their respective food dishes (clearly separated by a translucent divider).

www.sciencemag.org SCIENCE VOL 318 5 OCTOBER 2007 107

REPORTS

was faced with the choice of 8/2 versus 5/5. The cage in an L-shaped arrangement. The test ap- low rates (from 5 to 14% of the time). There

other games were 8/2 versus 2/8 (unfair versus paratus, which was outside of the cages, had was a trend toward different rejection rates of

hyperfair), 8/2 versus 8/2 (no choice), and 8/2 two sliding trays. On each tray were two dishes 8/2 offers across the four games (Friedman’s c23

versus 10/0 (unfair versus hyperunfair). Human with raisins, separated by translucent dividers: test = 6.643, P = 0.069). However, all paired

responders rejected the 8/2 offer most when the one for the proposer and the other for the comparisons were nonsignificant, indicating that,

alternative was fair (5/5 game), less when the responder (Fig. 1). Proposers would first choose crucially, chimpanzees rejected 8/2 offers equally

alternative was hyperfair (2/8 game), even less one of the two trays by pulling it halfway to the often regardless of the alternatives available to

when there was no alternative (8/2 game), and cages (as far as it would go); responders could the proposers (27). Moreover, this trend toward

hardly at all when the alternative was for the accept the offer by pulling the proposed tray the rejections was in the opposite direction of the

proposer to be even more selfish (10/0 game) remaining distance (via the rod which came into finding for humans (23). When proposers offered

(23). The differential rejection of unfair out- reach only as a result of the proposer’s pull) or non-8/2 alternatives (available in all but the 8/2

comes across the games suggests that people are could reject it by not pulling at all within 1 min. game), responders accepted them differentially

not sensitive solely to unfair distributions (7) nor The responder’s acceptance led to both subjects across the games (Friedman’s c22 test = 10.00,

solely to unfair intent (24) but to a combination being able to reach the food in their respective P = 0.012). In line with the principle of self-

of both (8). If chimpanzees are sensitive to un- dishes. Rejection led to both getting nothing, interest to accept any nonzero offer, responders

fairness and are negatively reciprocal, they would because the experimenter would remove all rejected 10/0 offers (in which the responder

behave like Homo reciprocans (25), whereas if food dishes after the trial ended. There were receives nothing) more often than 5/5 offers

they accept any nonzero offer regardless of four games (as in the study described above), all [Wilcoxon T+ test = 28.00, n = 8 (1 tie), P =

alternatives for the proposer, they will be more played within a single session: 2/8, 5/5, 8/2, and 0.016] and marginally more often than 2/8 offers

like the hypothetical Homo economicus (26). 10/0—each versus 8/2. The order of games was [Wilcoxon T+ test = 15.00, n = 7 (2 ties), P =

Subjects were 11 chimpanzees from a group- counterbalanced across subjects. 0.063]. Indeed, the only offers rejected by re-

Downloaded from http://science.sciencemag.org/ on October 6, 2020

housed colony at the Wolfgang Köhler Primate The most important finding is that respond- sponders more than 0% of the time were 10/0

Research Center (27). The proposer sat to the ers tended to accept any offer. As can be seen in offers (one-sample t test t9 = 4.735, P = 0.001). In

left of the responder, who was in an adjacent Fig. 2, responders rejected 8/2 offers at overall short, responders did not reject unfair offers when

the proposer had the option of making a fair offer;

Fig. 2. Offers made by Proposer Payoffs Responder they accepted almost all nonzero offers; and they

proposers and rejections Game Offers Proposer Responder Rejections reliably rejected only offers of zero. As can be

by responders in the four seen in Fig. 3, these results contrast strongly with

games. In each game, the 8 2 those of adult humans, who reject 8/2 offers most

39 (75%) 2 (5%) often when a fair (5/5) option is available for the

proposer could choose

between two payoff op- 5/5 5 5 proposer and least often when the alternative for

tions: 8/2 (8 raisins for 13 (25%) 0 (0%) the responder is even more selfish than the 8/2

the proposer and 2 for option (10/0) (23). Furthermore, unlike human

the responder) and an responders, who report being angry when

alternate [2/8 (2 for the 8 2 confronted with unfair offers (28), chimpanzee

45 (87%) 3 (7%)

proposer and 8 for the 2/8 responders showed signs of arousal [displays and

responder), 5/5 (5 for 2 8 tantrums (13, 29)] in less than 2% of the test trials

the proposer and 5 for 7 (13%) 0 (0%)

(all occurrences were by one individual in all

the responder), 8/2 (8 trials of a single session), whereas in a previous

for the proposer and 2 study in which the subjects had food taken away

for the responder), and 8 2

from them, these same individuals exhibited

10/0 (10 for the proposer 8/2 53 (100%) 6 (11%) tantrums or displays 40% of the time (21).

and 0 for the respond- 8 2

Consistent with previous studies on chim-

er)]. Results on the left

show the total number panzees (19, 20), proposers did not appear to

and corresponding per- take outcomes affecting the responder into

centage of offers for each 8 2 account. When given the opportunity, proposers

29 (54%) 4 (14%)

option made by propos- 10/0 did not make fair offers (Fig. 2) [see also (27),

ers in each game. (Trials 10 0 and fig. S1]. Given the propensity of responders

25 (46%) 11 (44%)

in which the proposer did to accept any nonzero offer, it is not surprising

not participate are not included, therefore the total number of offers varies across the games; percentages that chimpanzee proposers acted according to

are therefore based on the total number of offers for each option out of the total number of trials played for traditional economic models of self-interest.

each game.) Results on the right indicate the total number of each offer rejected and the corresponding However, it is perhaps surprising that proposers

percentage of rejections out of the total number of offers for each game. made zero offers to the responders, given that

these offers were rejected at the highest rate

(Fig. 2); chimpanzees are certainly capable of

Fig. 3. Rejection rates (% of 50

distinguishing two pieces of food from zero

trials) of 8/2 offers in the four

Rejection Rate (%)

games for chimpanzees in this

40 when choosing for themselves (30).

study (black bars) and for human To rule out more trivial interpretations of our

30

participants (white bars) [data are results, it was necessary to demonstrate that re-

from (23)]. 20 sponders and proposers understood the critical

features of the task. To this end, we conducted

10 familiarization and probe trials as well as a

0 follow-up study. First, sensitivity to fairness in

5/5 2/8 8/2 10/0 the ultimatum game requires that responders and

Game proposers each know what the other gains. We

108 5 OCTOBER 2007 VOL 318 SCIENCE www.sciencemag.org

REPORTS

therefore ran follow-up probe trials to determine We gave chimpanzees the most widely recog- 18. J. Bräuer, J. Call, M. Tomasello, Proc. R. Soc. London Ser.

whether the chimpanzees were capable of at- nized test for a sensitivity to fairness, the ultimatum B 273, 3123 (2006).

19. J. B. Silk et al., Nature 437, 1357 (2005).

tending to the amount of food available to the game, and found that they did not systematically 20. K. Jensen, B. Hare, J. Call, M. Tomasello, Proc. R. Soc.

partner. Subjects were tested alone, and they had make fair offers to conspecifics, nor did they sys- London Ser. B 273, 1013 (2006).

to look into the distal food dishes to correctly tematically refuse to accept unfair offers from 21. K. Jensen, J. Call, M. Tomasello, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.

choose the tray that would yield the largest conspecifics even though they could discriminate U.S.A. 104, 13046 (2007).

22. G. E. Bolton, R. Zwick, Games Econ. Behav. 10, 95

payoff from the partner’s position before going between the quantities available to themselves (1995).

through the open door to the adjacent cage to and their partners. It thus would seem that in 23. A. Falk, E. Fehr, U. Fischbacher, Econ. Inq. 41, 20

get it. They chose correctly at greater than chance this context, one of humans’ closest living rela- (2003).

levels, demonstrating that they would have been tives behaves according to traditional economic 24. M. Rabin, Am. Econ. Rev. 83, 1281 (1993).

25. E. Fehr, S. Gächter, Eur. Econ. Rev. 42, 845 (1998).

capable of seeing payoffs to the partner (27). models of self-interest, unlike humans, and that 26. R. H. Frank, Am. Econ. Rev. 77, 593 (1987).

Second, in inhibition probe trials, we found that this species does not share the human sensitivity 27. Additional details on the methods and results can be

subjects could inhibit pulling the rod when it led to fairness. found in the supporting material on Science Online.

to no food gain about 64% of the time, about the 28. M. Pillutla, J. Murnighan, Organ. Behav. Hum. Decision

Processes 68, 208 (1996).

same rate of pulling as in the 10/0 condition, References and Notes 29. T. Nishida, T. Kano, J. Goodall, W. C. McGrew,

suggesting that some of the failure to reject zero 1. R. Boyd, P. J. Richerson, J. Theor. Biol. 132, 337 (1988). M. Nakamura, Anthropol. Sci. 107, 141 (1999).

offers was due, at least some of the time, to an 2. W. D. Hamilton, J. Theor. Biol. 7, 1 (1964). 30. S. T. Boysen, G. G. Berntson, J. Comp. Psych. 103, 23

inability to inhibit a natural tendency to pull. 3. R. Trivers, Q. Rev. Biol. 46, 35 (1971). (1989).

4. R. Boyd, H. Gintis, S. Bowles, P. J. Richerson, Proc. Natl. 31. However, the same subjects could discriminate 10 from

Third, in discrimination probe trials, responders Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 3531 (2003). 8 in a previous study (35), and chimpanzees can reliably

could distinguish between all offers available to 5. H. Gintis, J. Theor. Biol. 206, 169 (2000). discriminate 0 from 2 (30), which they would have done

them (fig. S2), and proposers could do so for all 6. E. Fehr, U. Fischbacher, Nature 425, 785 (2003). had they attended to responder outcomes.

Downloaded from http://science.sciencemag.org/ on October 6, 2020

but 10/0 versus 8/2 (fig. S1) (31), demonstrating 7. E. Fehr, K. M. Schmidt, Q. J. Econ. 114, 817 (1999). 32. M. Shinada, T. Yamagishi, Y. Ohmura, Evol. Hum. Behav.

8. A. Falk, U. Fischbacher, Games Econ. Behav. 54, 293 25, 379 (2004).

that subjects were able to make maximizing (2006). 33. K. J. Haley, D. M. T. Fessler, Evol. Hum. Behav. 26, 245

choices. 9. W. Güth, R. Schmittberger, B. Schwarze, J. Econ. Behav. (2005).

Our subjects were from a single social group, Organ. 3, 367 (1982). 34. J. Stevens, D. Stephens, Behav. Ecol. 13, 393 (2002).

they did not interact anonymously, and they 10. C. F. Camerer, Behavioral Game Theory—Experiments in 35. D. Hanus, J. Call, J. Comp. Psych. 121, 241 (2007).

Strategic Interaction (Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton, 36. We thank the keepers of the Leipzig zoo, notably

played both roles in the game. However, anon-

NJ, 2003). S. Leideritz, D. Geissler, N. Schenk, and “Mozart”

ymous one-shot games are used in experiments 11. J. Henrich et al., Science 312, 1767 (2006). Herrmann for their help; G. Sandler for reliability coding;

with humans to decrease the likelihood of mak- 12. J. K. Murnighan, M. S. Saxon, J. Econ. Psych. 19, 415 R. Mundry for statistical advice; and two anonymous

ing fair offers or accepting unfair offers (32, 33), (1998). reviewers for helpful comments.

and so if anything, our experimental design 13. J. Goodall, The Chimpanzees of Gombe (Harvard Univ.

Press, Cambridge, MA, 1986).

Supporting Online Material

should have been skewed in favor of finding 14. A. P. Melis, B. Hare, M. Tomasello, Anim. Behav. 72, 275

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/318/5847/107/DC1

fairness sensitivity. The fact that chimpanzees in Materials and Methods

(2006).

SOM Text

this study did not punish other individuals for 15. F. Warneken, M. Tomasello, Science 311, 1301

Figs. S1 and S2

making unfair offers may be in part a reflection of (2006).

References

16. F. Warneken, B. Hare, A. P. Melis, D. Hanus,

the fact that active food sharing is rare in this M. Tomasello, PLoS Biol. 5, e184 (2007).

Movies S1 and S2

species (34) and may also be because they were 17. S. F. Brosnan, H. C. Schiff, F. B. M. de Waal, Proc. R. Soc. 30 May 2007; accepted 16 August 2007

unwilling to pay a cost to punish. London Ser. B 272, 253 (2005). 10.1126/science.1145850

Widespread Role for the Flowering-Time DICER-LIKE3 (DCL3), ARGONAUTE4 (AGO4),

and the two RNA polymerase IV isoforms, Pol

IVa and b (2–9).

Regulators FCA and FPA in To identify further components required for

siRNA-mediated chromatin silencing, we used

RNA-Mediated Chromatin Silencing a reporter system in which the Arabidopsis

phytoene desaturase (PDS) gene is silenced in

response to a homologous inverted repeat (SUC-

Isabel Bäurle,1* Lisa Smith,2† David C. Baulcombe,2‡ Caroline Dean1* PDS) (10). Two mutants that partially suppressed

the silencing of PDS (Fig. 1, A, B, C, and E)

The RRM-domain proteins FCA and FPA have previously been characterized as flowering-time showed late flowering that was reversible by

regulators in Arabidopsis. We show that they are required for RNA-mediated chromatin silencing of vernalization. The silencing and flowering pheno-

a range of loci in the genome. At some target loci, FCA and FPA promote asymmetric DNA types cosegregated, and the mutations mapped

methylation, whereas at others they function in parallel to DNA methylation. Female gametophytic to chromosomes 2 and 4. The flowering pheno-

development and early embryonic development are particularly susceptible to malfunctions in FCA type suggested involvement of FPA and FCA,

and FPA. We propose that FCA and FPA regulate chromatin silencing of single and low-copy genes two members of the autonomous pathway (11),

and interact in a locus-dependent manner with the canonical small interfering RNA–directed DNA mapping to those genomic regions. Sequencing

methylation pathway to regulate common targets. revealed a premature termination codon in FPA

(Trp98*, G to A, fpa-8) and FCA (Gln537*, C to

eterochromatin in many organisms is C, or T) sequence contexts. In Arabidopsis, small

H

T, fca-11). The flowering defect was confirmed

characterized by extensive DNA meth- interfering RNAs (siRNAs) are involved in by complementation analysis with previously

ylation and histone modifications (1). localizing and maintaining these chromatin known flowering mutants (fca-9, fpa-7, and

Plants display cytosine methylation in CG, modifications in processes requiring RNA- fve-3; Fig. 1F), which also showed PDS silenc-

CNG (N = any nucleotide), and CHH (H = A, DEPENDENT RNA POLYMERASE2 (RDR2), ing (fig. S1). Thus, FCA and FPA are required

www.sciencemag.org SCIENCE VOL 318 5 OCTOBER 2007 109

Chimpanzees Are Rational Maximizers in an Ultimatum Game

Keith Jensen, Josep Call and Michael Tomasello

Science 318 (5847), 107-109.

DOI: 10.1126/science.1145850

Downloaded from http://science.sciencemag.org/ on October 6, 2020

ARTICLE TOOLS http://science.sciencemag.org/content/318/5847/107

SUPPLEMENTARY http://science.sciencemag.org/content/suppl/2007/10/04/318.5847.107.DC1

MATERIALS

RELATED http://science.sciencemag.org/content/sci/319/5861/282.2.full

CONTENT

REFERENCES This article cites 31 articles, 4 of which you can access for free

http://science.sciencemag.org/content/318/5847/107#BIBL

PERMISSIONS http://www.sciencemag.org/help/reprints-and-permissions

Use of this article is subject to the Terms of Service

Science (print ISSN 0036-8075; online ISSN 1095-9203) is published by the American Association for the Advancement of

Science, 1200 New York Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20005. The title Science is a registered trademark of AAAS.

American Association for the Advancement of Science

You might also like

- RBJ DWX HMUa X4Document371 pagesRBJ DWX HMUa X4Delia Dascalu0% (1)

- Prisoner's DilemmaDocument13 pagesPrisoner's DilemmaVaibhav JainNo ratings yet

- Fehr, E., & Gächter, S. (2000) - Fairness and Retaliation - The Economics of Reciprocity.Document55 pagesFehr, E., & Gächter, S. (2000) - Fairness and Retaliation - The Economics of Reciprocity.Anonymous WFjMFHQNo ratings yet

- Dls 212 - Selected Topics in General Physics: University of Northern PhilippinesDocument56 pagesDls 212 - Selected Topics in General Physics: University of Northern PhilippinesKennedy Fieldad Vagay100% (5)

- The Emergence of Cooperation Among EgoistsDocument13 pagesThe Emergence of Cooperation Among EgoistsIgor DemićNo ratings yet

- Review of Ostrom's Governing The CommonsDocument11 pagesReview of Ostrom's Governing The CommonsMei Mei ChanNo ratings yet

- 1521748667rocky Article Breakage ModellingDocument6 pages1521748667rocky Article Breakage ModellingEruaro Guerra CarvajalNo ratings yet

- Decent Work Employment and Transcultural Nursing NCM 120: Ma. Esperanza E. Reavon, Man, RNDocument64 pagesDecent Work Employment and Transcultural Nursing NCM 120: Ma. Esperanza E. Reavon, Man, RNMa. Esperanza C. Eijansantos-Reavon100% (1)

- FEDERALISM Handbook of Fiscal FederalismDocument585 pagesFEDERALISM Handbook of Fiscal FederalismLeonardo SimonciniNo ratings yet

- Modelthinking 10.01 Nowak and SygmundDocument10 pagesModelthinking 10.01 Nowak and SygmundAtiquzzamanNo ratings yet

- Anomalies CooperationDocument30 pagesAnomalies CooperationDiogo MarquesNo ratings yet

- Ecologies of EnvyDocument43 pagesEcologies of EnvyAnonymous kHjswl6No ratings yet

- Diminishing Reciprocal Fairness by Disrupting The Right Prefrontal CortexDocument4 pagesDiminishing Reciprocal Fairness by Disrupting The Right Prefrontal Cortexkapa_69No ratings yet

- Journal of Research in Personality: Patrick Mussel, Anja S. Göritz, Johannes HewigDocument4 pagesJournal of Research in Personality: Patrick Mussel, Anja S. Göritz, Johannes HewigusernnammeNo ratings yet

- Experiment 3.1Document3 pagesExperiment 3.1WendyNo ratings yet

- Prisoner's Dilemma: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument18 pagesPrisoner's Dilemma: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaKong Tzeh FungNo ratings yet

- Henrich 2015 Culture and Social BehaviorDocument6 pagesHenrich 2015 Culture and Social BehaviorIrene BrionesNo ratings yet

- Yamagishi Impunity Game PDFDocument4 pagesYamagishi Impunity Game PDFLeonardo SimonciniNo ratings yet

- Dictator and Ultimatum GamesDocument7 pagesDictator and Ultimatum GamesJanice YangNo ratings yet

- GAME Theory by (M.A.K. Pathan)Document12 pagesGAME Theory by (M.A.K. Pathan)M.A.K. S. PathanNo ratings yet

- Xiao HouserDocument4 pagesXiao HouserJeremy LarnerNo ratings yet

- Rich and Poor (Selfishness)Document47 pagesRich and Poor (Selfishness)JaneNo ratings yet

- Theory of Elinor OstromDocument5 pagesTheory of Elinor OstromSanjana KrishnakumarNo ratings yet

- Tullock, Adam Smith and The Prisoner's DilemmaDocument10 pagesTullock, Adam Smith and The Prisoner's DilemmaFutureTara GanapathyNo ratings yet

- Journal of Public Economics: Drew Fudenberg, Parag A. PathakDocument9 pagesJournal of Public Economics: Drew Fudenberg, Parag A. PathakAndré Luíz FerreiraNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 0303264795015485 MainDocument27 pages1 s2.0 0303264795015485 Maincello.kabobNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of Cooperation : Robert AxelrodDocument9 pagesThe Evolution of Cooperation : Robert AxelrodSallivanNo ratings yet

- Workshop in Political Theory: & Policy AnalysisDocument21 pagesWorkshop in Political Theory: & Policy AnalysisLuis Felipe BicalhoNo ratings yet

- Elements of Reciprocity and Social Value OrientationDocument9 pagesElements of Reciprocity and Social Value OrientationArlenNo ratings yet

- A016 - Microeconomics Assignment Word DocumentDocument9 pagesA016 - Microeconomics Assignment Word DocumentAayushi JogiNo ratings yet

- Strong Reciprocity Human Cooperation and Enforcement of Social NormsDocument32 pagesStrong Reciprocity Human Cooperation and Enforcement of Social NormsanthropomneNo ratings yet

- Is Homo Economicus A Five Year Old?Document8 pagesIs Homo Economicus A Five Year Old?el.rothNo ratings yet

- Articulo Dixit en PBSDocument4 pagesArticulo Dixit en PBSJoseeeeNo ratings yet

- Real World Solutions To Prisoners' Dilemmas: AboutDocument36 pagesReal World Solutions To Prisoners' Dilemmas: AboutMuhammad DaudNo ratings yet

- Tullock 1985Document10 pagesTullock 1985Jorge VásquezNo ratings yet

- The Further Evolution of CooperationDocument6 pagesThe Further Evolution of CooperationIgor DemićNo ratings yet

- Elinor Ostrom vs. Malthus and Hardin "How Inxorable Is The 'Tragedy of The Commons'?Document52 pagesElinor Ostrom vs. Malthus and Hardin "How Inxorable Is The 'Tragedy of The Commons'?mwhitakerNo ratings yet

- Axelrod 1981Document14 pagesAxelrod 1981maricartiNo ratings yet

- 5.engineering Altruism A Theoretical and Experimental Investigation of Anonymity and Gift GivingDocument12 pages5.engineering Altruism A Theoretical and Experimental Investigation of Anonymity and Gift GivingBlayel FelihtNo ratings yet

- Cooperation Nowak Science06Document12 pagesCooperation Nowak Science06Sofia BatalhaNo ratings yet

- A Neural Basis For Social Coooperation Rilling 2002Document11 pagesA Neural Basis For Social Coooperation Rilling 2002TeddyBear20No ratings yet

- Letters: Parochial Altruism in HumansDocument4 pagesLetters: Parochial Altruism in HumansScott KennedyNo ratings yet

- The Territorial Foundations of Human Property, in "Evolution and Human Behaviour" 2011Document8 pagesThe Territorial Foundations of Human Property, in "Evolution and Human Behaviour" 2011fcrevatinNo ratings yet

- Abbink - 2005 - Laboratory Experiments On CorruptionDocument17 pagesAbbink - 2005 - Laboratory Experiments On CorruptionAndres DuitamaNo ratings yet

- 2009 Hauser Et Al Evolving Reciprocity and SpiteDocument12 pages2009 Hauser Et Al Evolving Reciprocity and SpiteBlasNo ratings yet

- Power and CorruptionDocument13 pagesPower and CorruptionC.A. V.N.No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0022519319304102 MainDocument13 pages1 s2.0 S0022519319304102 Maincello.kabobNo ratings yet

- Commons&Anti CommonsDilemmasDocument20 pagesCommons&Anti CommonsDilemmasrmtlawNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id1592456Document37 pagesSSRN Id1592456lkasuga1801No ratings yet

- Bargaining, Reputation and Equilibrium Selection in Repeated GamesDocument26 pagesBargaining, Reputation and Equilibrium Selection in Repeated GamesAnonymous a6UCbaJNo ratings yet

- Social Interactions: Economic Theory 1A Week 4Document44 pagesSocial Interactions: Economic Theory 1A Week 4Anqi LiuNo ratings yet

- SpatialgameDocument19 pagesSpatialgameGeorgeLauNo ratings yet

- Andreoni Miller ECTA 2002Document18 pagesAndreoni Miller ECTA 2002William F. UrregoNo ratings yet

- Evolution and Human Behavior: Kyle A. Thomas, Peter Descioli, Steven PinkerDocument12 pagesEvolution and Human Behavior: Kyle A. Thomas, Peter Descioli, Steven PinkerDoris AngelNo ratings yet

- Regulating The Undead in A Liberal World Order: Free-Rider Problem, As The Payoff Structure inDocument10 pagesRegulating The Undead in A Liberal World Order: Free-Rider Problem, As The Payoff Structure inMadalin PufuNo ratings yet

- Prisoners' Dilemma: Search Site Search Card Catalog Search A BookDocument4 pagesPrisoners' Dilemma: Search Site Search Card Catalog Search A Bookdeepak_darshan_1No ratings yet

- Attribution and Reciprocity in An Experimental Labor MarketDocument41 pagesAttribution and Reciprocity in An Experimental Labor MarketJorge RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Game TheoryDocument26 pagesGame Theorynoelia gNo ratings yet

- An Wolkenten, M., Brosnan, S. F., & de Waal, F. B. M. (2007) - Inequity Responses of Monkeys Modified by Effort.Document6 pagesAn Wolkenten, M., Brosnan, S. F., & de Waal, F. B. M. (2007) - Inequity Responses of Monkeys Modified by Effort.Gabriel Fernandes Camargo RosaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0167268118302968 MainDocument20 pages1 s2.0 S0167268118302968 Mainleo GalileoNo ratings yet

- CorruptionDocument2 pagesCorruptionsari alwayszikrullahNo ratings yet

- 2016 Hypothesisy Blows HypothesisX EvolutionaryEconDocument1 page2016 Hypothesisy Blows HypothesisX EvolutionaryEconHellen RuthesNo ratings yet

- Five Rules For The Evolution of Cooperation: C C C C C C C C C C C C C CDocument5 pagesFive Rules For The Evolution of Cooperation: C C C C C C C C C C C C C CCuloNo ratings yet

- Impunidade Estudo PublicadoDocument3 pagesImpunidade Estudo PublicadovesgaogarotaoNo ratings yet

- Proto Rustichini Sofianos (2018) Intelligence PT RGDocument149 pagesProto Rustichini Sofianos (2018) Intelligence PT RGLeonardo SimonciniNo ratings yet

- Class Notes Final VersionDocument76 pagesClass Notes Final VersionLeonardo SimonciniNo ratings yet

- Camerer Cognitive Hierarchy ModelDocument38 pagesCamerer Cognitive Hierarchy ModelLeonardo SimonciniNo ratings yet

- Chapter Appendix Prospect Theory Fox2014Document35 pagesChapter Appendix Prospect Theory Fox2014Leonardo SimonciniNo ratings yet

- Second Generation PatentsDocument355 pagesSecond Generation PatentsLeonardo SimonciniNo ratings yet

- Optimize, Satisfice, or Choose Without Deliberation? A Simple Minimax-Regret AssessmentDocument19 pagesOptimize, Satisfice, or Choose Without Deliberation? A Simple Minimax-Regret AssessmentLeonardo SimonciniNo ratings yet

- Stanovich Dual Process' CritiqueDocument19 pagesStanovich Dual Process' CritiqueLeonardo SimonciniNo ratings yet

- Rationality in Economics: Constructivist and Ecological FormsDocument5 pagesRationality in Economics: Constructivist and Ecological FormsLeonardo SimonciniNo ratings yet

- Baker1993 Expectations of SpousesDocument12 pagesBaker1993 Expectations of SpousesLeonardo SimonciniNo ratings yet

- Firearms Ban Are Effective Meta AnalysisDocument23 pagesFirearms Ban Are Effective Meta AnalysisLeonardo SimonciniNo ratings yet

- Why We Should Reject Nudge': Research and AnalysisDocument8 pagesWhy We Should Reject Nudge': Research and AnalysisLeonardo SimonciniNo ratings yet

- Symbolizing Crime Control: Reflections On Zero ToleranceDocument23 pagesSymbolizing Crime Control: Reflections On Zero ToleranceLeonardo SimonciniNo ratings yet

- Can Policing Disorder Reduce Crime? A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument22 pagesCan Policing Disorder Reduce Crime? A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisLeonardo SimonciniNo ratings yet

- DiTommasoCristian RiskAndUncertainty IndividualRiskPerceptionDocument9 pagesDiTommasoCristian RiskAndUncertainty IndividualRiskPerceptionLeonardo SimonciniNo ratings yet

- Do Predictive Power of Fibonacci RetraceDocument6 pagesDo Predictive Power of Fibonacci RetraceLeonardo SimonciniNo ratings yet

- Antony Braga Deterrence Effect CrimesDocument36 pagesAntony Braga Deterrence Effect CrimesLeonardo SimonciniNo ratings yet

- Ashenfelter Predicting Quality Boudeux WineDocument14 pagesAshenfelter Predicting Quality Boudeux WineLeonardo SimonciniNo ratings yet

- Costa Gomes Behaviour in GamesDocument43 pagesCosta Gomes Behaviour in GamesLeonardo SimonciniNo ratings yet

- Haggeretal.2010.Egodepletionandthestrengthmodelofself Control - Ameta AnalysisDocument31 pagesHaggeretal.2010.Egodepletionandthestrengthmodelofself Control - Ameta AnalysisLeonardo SimonciniNo ratings yet

- Eye Tracking A Comprehensive Guide To Methods andDocument22 pagesEye Tracking A Comprehensive Guide To Methods andLeonardo SimonciniNo ratings yet

- Intelligence, Personality, and Gains From Cooperation in Repeated InteractionsDocument40 pagesIntelligence, Personality, and Gains From Cooperation in Repeated InteractionsLeonardo SimonciniNo ratings yet

- Eye Tracking A Comprehensive Guide To Methods andDocument22 pagesEye Tracking A Comprehensive Guide To Methods andLeonardo SimonciniNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Cooperation Pietro Dal BoDocument20 pagesEvolution of Cooperation Pietro Dal BoLeonardo SimonciniNo ratings yet

- Laser Machine ManualDocument9 pagesLaser Machine ManualJoao Stuard Herrera QuerevalúNo ratings yet

- Digitalcommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Digitalcommons@University of Nebraska - LincolnDocument14 pagesDigitalcommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Digitalcommons@University of Nebraska - LincolnAmiibahNo ratings yet

- Khao Sat THPT - Ks PGD - 172Document3 pagesKhao Sat THPT - Ks PGD - 172Hạc DavidNo ratings yet

- MQC Screw ThreadsDocument22 pagesMQC Screw ThreadsNayemNo ratings yet

- Clinical Skills Coordinator Job DescriptionDocument6 pagesClinical Skills Coordinator Job DescriptionYee Han KwongNo ratings yet

- Design SSHEDocument7 pagesDesign SSHEAndres MarinNo ratings yet

- AP Literature EssayDocument2 pagesAP Literature EssayAkshat TirumalaiNo ratings yet

- Unit 8: Lesson ADocument5 pagesUnit 8: Lesson Aمحمد ٦No ratings yet

- Climate Change Impacts of Climate ChangeDocument22 pagesClimate Change Impacts of Climate ChangeLomyna MorreNo ratings yet

- Torsional and Lateral Torsional BucklingDocument52 pagesTorsional and Lateral Torsional BucklingJithin KannanNo ratings yet

- Of Plymouth Plantation - William BradfordDocument10 pagesOf Plymouth Plantation - William BradfordRania AbunijailaNo ratings yet

- CEBEX112Document2 pagesCEBEX112reshmitapallaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1.3 Drawing - LetteringDocument9 pagesChapter 1.3 Drawing - LetteringfikremaryamNo ratings yet

- Assignment No. 1Document4 pagesAssignment No. 1Peng GuinNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - Nature of SelfDocument6 pagesChapter 1 - Nature of SelfSharmaine Gatchalian BonifacioNo ratings yet

- Acitivity Sheet TemplateDocument2 pagesAcitivity Sheet TemplateDexter AsprecNo ratings yet

- Perhitungan Struktur KlinikDocument66 pagesPerhitungan Struktur Klinikdenysuryawan79No ratings yet

- 105-0021 4200B Nov2018Document4 pages105-0021 4200B Nov2018devendra bansalNo ratings yet

- Vit B12 LiteratureDocument42 pagesVit B12 Literaturenav90100% (1)

- A10 Unit Review - Fundamental Industrial Communication SkillsDocument7 pagesA10 Unit Review - Fundamental Industrial Communication SkillsviksursNo ratings yet

- Maizir 2019 IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 615 012105Document9 pagesMaizir 2019 IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 615 012105Green MyanmarNo ratings yet

- Nejmoa2026116 PDFDocument11 pagesNejmoa2026116 PDFMusdaliva Tri Riskiani AlminNo ratings yet

- 7.1 Moments-Cie Ial Physics-Theory QPDocument11 pages7.1 Moments-Cie Ial Physics-Theory QPAhmed HunainNo ratings yet

- University of Galway v13Document113 pagesUniversity of Galway v13IsaCoboNo ratings yet

- Computer Skills: MS Office Application (MS Word, MS Excel, MS Power Point, MS Access), E-Mail &Document2 pagesComputer Skills: MS Office Application (MS Word, MS Excel, MS Power Point, MS Access), E-Mail &NADIM MAHAMUD RABBINo ratings yet

- Example Paired Ttest PDFDocument2 pagesExample Paired Ttest PDFmary joy quintosNo ratings yet