Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Articles

Uploaded by

Eula Angelica OcoCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Articles

Uploaded by

Eula Angelica OcoCopyright:

Available Formats

Introduction

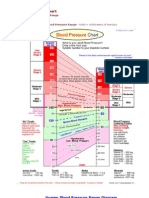

Hypertension is a highly prevalent disorder in older people. Hypertension, especially

isolated systolic hypertension, is commonly found in older which is about 60–79 years of

age and elderly that ages ≥80 people. Hypertension, defined as a blood pressure of

140/90 mmHg or more or being on antihypertensive medications. Antihypertensive drug

therapy should be considered in all aging hypertensive patients, as treatment greatly

reduces cardiovascular events. Most classes of antihypertensive medications may be

used as first-line treatment with the possible exception of α- and β-blockers. An initial

blood pressure treatment goal is less than 140/90 mmHg in all older patients and less

than 150/80 mmHg in the non-frail elderly. The current paradigm of delaying therapeutic

interventions until people are at moderate or high cardiovascular risk, a universal

feature of hypertensive patients over 60 years of age, leads to vascular injury or disease

that is only partially reversible with treatment.

The aim of this article is to summarize current knowledge about hypertension in aging

individuals. In this article, older people aged 60–79 years are considered separately

from the very old or elderly, defined as 80 years of age or more.

Blood Pressure with Aging

Blood pressure, particularly systolic blood pressure, rises with age, although the

diastolic component of blood pressure begins to plateau around the age of 50 years and

slowly declines thereafter. These temporal changes in blood pressure increase pulse

pressure and are associated with a dramatic rise in the prevalence from the beginning

of isolated systolic hypertension. In a community-based prospective cohort study, more

than 90% of normotensive adults in midlife develop hypertension in their lifetime. The

discrepant trends in systolic and diastolic blood pressure provides an explanation for the

change in the relative proportion of different forms of hypertension with age. In the

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey less than 20% of hypertensive

individuals older than 60 years of age had an elevated diastolic blood pressure, and the

proportion declined steadily from the sixth decade onward

Epidemiology of Hypertension with Aging

Major overviews of observational studies have shown a continuous and positive

relationship between cardiovascular events and usual blood pressure above a baseline

level of approximately 115/75 mmHg at all ages and in both sexes. Although the

strength of the association weakens with age, the absolute difference in cardiovascular

risk between the highest and lowest usual blood pressure levels is much greater in older

subjects. Thus, the burden of disease that is potentially avoidable by blood pressure-

lowering treatment would be expected to be greater in older individuals.

In general, these population-based cohort studies were conducted in adults with no

previous vascular disease. Thus, the results may not necessarily be applicable to

subjects with significant comorbid diseases. Furthermore, in hypertensive patients

whose initial blood pressure was in the range considered to be uncontrolled, survival

was not significantly reduced for each 10 mmHg increase in systolic blood pressure or

diastolic blood pressure. The term 'reverse epidemiology' has been used to describe the

pattern of increased survival associated with higher blood pressure, and the

phenomenon likely reflects the confounding effects of other comorbid conditions.

Pathophysiology of Age-related Hypertension

The aorta and its major branches act as distensible tubes that promote the conversion

of the pulsatile output of the heart into a steady stream in the peripheral circulation. With

aging, there is a progressive loss of the visco-elastic properties of conduit vessels,

increased atherosclerotic arterial disease, and hypertrophy and sclerosis of muscular

arteries and arterioles. These vascular changes lead to a loss of the cushioning function

of the conduit vessels and stiffening of the arterial vasculature overall, which promote

the early return of reflected waves from the peripheral arterial circulation. Early wave

reflection amplifies the systolic pressure wave generated with each heartbeat, leading to

an increase in systolic pressure and a fall in diastolic pressure.

Diagnosis of Hypertension & Cardiovascular Risk Assessment

The diagnosis of hypertension has traditionally relied upon repeated office or clinic

blood pressure measurements taken by a healthcare professional using a mercury

sphygmomanometer. Increasingly, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring is being used

to expedite the diagnosis of hypertension and categorize it into different types.

Currently, it is only approved for reimbursement to diagnose white coat or isolated office

hypertension (elevated office or clinic readings and normal daytime blood pressure from

ambulatory recording). Isolated office hypertension is more common at older ages and

in females, and is often mistaken for uncontrolled hypertension, which may lead to

overtreatment. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring is also useful to identify

individuals with masked hypertension, most commonly defined as normal office blood

pressure of less than 140/90 mmHg and high diurnal ambulatory blood pressure of

135/85 mmHg or more. While age does not seem to affect its prevalence, nonetheless it

is a common finding, particularly among treated hypertensive patients, and is

associated with increased risk of cardiovascular events. Finally, ambulatory blood

pressure monitoring provides important information on the pattern of nocturnal blood

pressure (nocturnal hypertension, nocturnal hypotension, dipping status and autonomic

dysfunction). Several studies have shown that nocturnal hypertension and nondipping of

blood pressure during sleep are important harbingers of poor cardiovascular prognosis

and that night-time pressures more accurately predict the occurrence of death and

cardiovascular events than daytime pressures, independent of other confounders. The

prevalence of nondippers among hypertensive men and women increases progressively

with age, reaching more than 40% in subjects aged 70 years or older.

Status of Hypertension in the Philippines

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the Philippines

and elevated BP is identified to be one of the major risk factors. The prevalence of HTN

in the country has been increasing. Several cross-sectional studies have shown that the

numbers are steadily increasing; from 11% in 1992 to 25% in 2008. The National

Nutrition and Health Survey (NNHES) of the Food and Nutrition Research Institute

conducted in 2012 indicated a small decline in the prevalence of individuals with HTN,

about 22.3%. Unfortunately, the survey is based on a single visit BP measurement

alone. The same survey also showed that the highest prevalence of HTN is found in the

70 years old and above age group, males have a higher rate of elevated BP, patients

who live in the rural areas, and those who have high economic status.

In a prospective, multistage, stratified, two-phase, nationwide survey published in 2007,

the prevalence of HTN in 3901 participants was 21%. HTN prevalence would increase

by 50% in individuals more than 50 years old. It is more common in the urban areas,

particularly in Metro Manila, and is more common in the middle economic stature.

Similar to the other countries in Southeast Asia, awareness and control are very low.

Only 16% of those surveyed are aware of having elevated BP. Treatment control was

seen in only 20% of the hypertensive. In the survey, Filipino patients were prescribed

more with a beta-blocker, but compliance rate is higher if they are on an angiotensin

receptor blocker.

The island nation of the Philippines has 7101 islands and the geography has

caused difficulty in the delivery of healthcare in the country. Government programs are

being implemented to include treatment of non-communicable diseases. Recently, the

Universal Health Care Act has been passed which guarantees equitable access to

quality and affordable health-care services for all Filipinos.

Treatment

Lifestyle Modification

Lifestyle modification is widely considered to be a good starting point in treating

hypertensive patients of all ages. With regard to nonpharmacological interventions for

lowering BP, although benefits have been shown in younger populations, there is little

evidence from controlled studies in hypertensive patients aged 60 plus. Some of the

proposed lifestyle changes, including weight reduction, Dietary Approaches to Stop

Hypertension/Mediterranean diet, dietary sodium reduction, physical activity, and

moderate alcohol consumption may, however, not be appropriate or relevant and may

even be detrimental. Thus, a weight reduction in patients >80 years easily induces a

loss of muscle mass (sarcopenia) and can even cause cachexia, unless an intensive

physical training program and adequate protein supplementation are concomitantly

applied.

Equally, an excessive salt reduction might induce hyponatremia, malnutrition,

and orthostatic hypotension with increased risk of falls. Physical activity adapted to the

functional capacities of the older person and to his or her preferences is of major

importance, even if not meeting the amount recommended by current guidelines, which

is similar for older and younger adult subjects. Finally, excessive alcohol intake should

be discouraged, not only because of its pressor effect but also mainly because of

increased risk of falls and confusion

Antihypertensive Medications

The relative and absolute benefits and the safety of antihypertensive drug

treatment in older hypertensive patients have been summarized in several systematic

reviews. In trials that only included isolated systolic hypertensive patients, systolic blood

pressure had to be 160 mmHg or more with diastolic blood pressure less than 95

mmHg. The lower boundary for old age was set at 60 years without an upper limit. In

trials including patients with both isolated systolic hypertension and systolic–diastolic

hypertension, the systolic blood pressure for inclusion ranged from 160 mmHg to more

than 200 mmHg with a wide range of threshold values for diastolic blood pressure. In

most instances, the first-line antihypertensive treatment was a thiazide diuretic (±

potassium-sparing agent), dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker or β-blocker. Active

treatment reduced total mortality by 13%, cardiovascular mortality by 18%, all

cardiovascular complications by 26%, stroke by 30% and coronary events by

23%.Based on such findings, guidelines recommend treating all hypertensive patients in

their seventh and eighth decade with antihypertensive medications from most classes of

agents although some authoritative bodies do not recommend α- or β-blockers as first-

line agents in the absence of specific indications for their use.

An important caveat in making treatment recommendations for older hypertensive

patients is the paucity of trial evidence on the advantages and possible harm associated with

blood pressure lowering in patients at low or even moderate risk for cardiovascular disease with

systolic blood pressure in the range of 140–159 mmHg. On the other hand, there are a large

number of clinical trials studying the effects of antihypertensive agents in patients at high risk for

a cardiovascular event. A substantial number of participants in the trials had treated or

untreated hypertension and were 60 years of age and older. In general, the experimental

treatment lowered systolic blood pressure more than that observed in the group receiving the

comparator intervention.

Conclusions

Hypertension is a highly prevalent disorder in older and elderly patients and is an

important contributor to their high absolute cardiovascular risk. Isolated systolic

hypertension is the dominant form, attributed to progressive arterial stiffening and

increasing atherosclerotic burden of conduit vessels with age and hypertrophy and

sclerosis of the muscular arteries and arterioles. Antihypertensive drug therapy should

now be considered in all hypertensive patients, regardless of age. Recent evidence

suggests antihypertensive medications from most classes of agents may be used to

control blood pressure, although some authoritative bodies do not recommend α- or β-

blockers as first-line agents in the absence of specific indications for their use. Future

studies will likely focus on determining the treatment strategy that will provide optimal

protection against developing cardiovascular disease. Finally, better physician

management has improved outcomes overall, but challenges continue to exist for

patients at high cardiovascular risk.

Bibiliography

http://www.hypertensionjournal.in/eJournals/ShowText.aspx?

ID=56&Type=FREE&TYP=TOP&IN=&IID=6&isPDF=NO

https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/734880_3

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313236

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- O L O G C: UR ADY F Uadalupe OllegesDocument2 pagesO L O G C: UR ADY F Uadalupe OllegesEula Angelica OcoNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- System Findings Interpretation and Analysis: ReferenceDocument2 pagesSystem Findings Interpretation and Analysis: ReferenceEula Angelica OcoNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Oco SWK7Document2 pagesOco SWK7Eula Angelica OcoNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Oco (Seatwork 2)Document3 pagesOco (Seatwork 2)Eula Angelica OcoNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Assessment Normal Findings Deviations From Normal HypoactiveDocument2 pagesAssessment Normal Findings Deviations From Normal HypoactiveEula Angelica OcoNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Quetiapine Drug StudyDocument3 pagesQuetiapine Drug StudyEula Angelica Oco100% (1)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Diagnostic Test PrefaceDocument9 pagesDiagnostic Test PrefaceEula Angelica OcoNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Alternative FeedingDocument36 pagesAlternative FeedingEula Angelica OcoNo ratings yet

- GBS IntroDocument2 pagesGBS IntroEula Angelica OcoNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Mental Retardation: Costes - Doqueza - Mendiola - Oco - TapasDocument28 pagesMental Retardation: Costes - Doqueza - Mendiola - Oco - TapasEula Angelica OcoNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Conduct Disorder: Ahmad, Nurhadda Cadenas, Miche Delos Santos, Mary Ann Pabillore, Jocel Papa, DevelynDocument34 pagesConduct Disorder: Ahmad, Nurhadda Cadenas, Miche Delos Santos, Mary Ann Pabillore, Jocel Papa, DevelynEula Angelica OcoNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Nutrients Functions Sources Protein and Amino Acids That Make Up ProteinDocument2 pagesNutrients Functions Sources Protein and Amino Acids That Make Up ProteinEula Angelica OcoNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Mechanical Aids For Ambulation Include: Canes Walkers CrutchesDocument17 pagesMechanical Aids For Ambulation Include: Canes Walkers CrutchesEula Angelica OcoNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Level of Anxiety - g5Document39 pagesLevel of Anxiety - g5Eula Angelica OcoNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Doh ProgramDocument39 pagesDoh ProgramEula Angelica Oco100% (1)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Generalized Anxiety DisorderDocument24 pagesGeneralized Anxiety DisorderEula Angelica OcoNo ratings yet

- Virtual Quiz Bee Objectives:: Team AbdellaDocument2 pagesVirtual Quiz Bee Objectives:: Team AbdellaEula Angelica OcoNo ratings yet

- Application of OMAHA System of Community DiagnosisDocument5 pagesApplication of OMAHA System of Community DiagnosisEula Angelica OcoNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Ways To Promote Wound HealingDocument3 pagesWays To Promote Wound HealingEula Angelica OcoNo ratings yet

- Reproductive System AgentsDocument56 pagesReproductive System AgentsEula Angelica OcoNo ratings yet

- How Can I Prevent High Blood Pressure?: Eat A Healthy Diet. EatingDocument3 pagesHow Can I Prevent High Blood Pressure?: Eat A Healthy Diet. EatingEula Angelica OcoNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Implementation of Dress Code Is Really Important Among Professional NursesDocument1 pageImplementation of Dress Code Is Really Important Among Professional NursesEula Angelica OcoNo ratings yet

- Adult Immediate Post Cardiac Arrest Care Algorithm 2015 UpdateDocument1 pageAdult Immediate Post Cardiac Arrest Care Algorithm 2015 UpdateRyggie Comelon0% (1)

- HFA Position Papers 2019Document264 pagesHFA Position Papers 2019Irina Cabac-PogoreviciNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For The Assessment, Diagnosis and Management of Peripheral Arterial DiseaseDocument60 pagesGuidelines For The Assessment, Diagnosis and Management of Peripheral Arterial DiseaseMourad LAKHOUADRANo ratings yet

- Basis of ECG and Intro To ECG InterpretationDocument10 pagesBasis of ECG and Intro To ECG InterpretationKristin SmithNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- TBPI Information PDFDocument8 pagesTBPI Information PDFxtraqrkyNo ratings yet

- Distal AnDocument99 pagesDistal AnMeycha Da FhonsaNo ratings yet

- Tachicardia A QRS LarghiDocument16 pagesTachicardia A QRS LarghiAlberto MichielonNo ratings yet

- Introducere in Cardiologie: Prof. Maria DOROBANTUDocument33 pagesIntroducere in Cardiologie: Prof. Maria DOROBANTUSolomon VioletaNo ratings yet

- Flashcards - Topic 8 The Circulatory System - Edexcel Biology GCSEDocument63 pagesFlashcards - Topic 8 The Circulatory System - Edexcel Biology GCSEPraise Kinkin Princess GanaNo ratings yet

- Cardiac Cycle Lab-1Document6 pagesCardiac Cycle Lab-1Matthew SANo ratings yet

- Ecg Ospe QuizDocument26 pagesEcg Ospe Quizsivakamasundari pichaipillaiNo ratings yet

- Interpretasi EKGDocument81 pagesInterpretasi EKGGyna MarsianaNo ratings yet

- Blood Supply of Upper LimbDocument36 pagesBlood Supply of Upper Limbteklay100% (2)

- Atherosclerosis and Coronary Artery Disease AtherosclerosisDocument8 pagesAtherosclerosis and Coronary Artery Disease Atherosclerosiskarim mohamedNo ratings yet

- Lab 11 AntianginalDocument4 pagesLab 11 AntianginalanaNo ratings yet

- Bls - Acls: Roli Joseph Z. Monta, RN BLS, Acls, Trauma, Hazmat CertifiedDocument72 pagesBls - Acls: Roli Joseph Z. Monta, RN BLS, Acls, Trauma, Hazmat CertifiedEkoy TheRealNo ratings yet

- Kami Export - Cardiovascular System Lecture Outline 1st PeriodDocument16 pagesKami Export - Cardiovascular System Lecture Outline 1st PeriodJada NovakNo ratings yet

- Venema E, Et Al. 2018Document6 pagesVenema E, Et Al. 2018widyadariNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hypertension CaseDocument3 pagesHypertension CaseArnold Christian QuilonNo ratings yet

- PV, HF, PpokDocument14 pagesPV, HF, PpokRizki AmeliaNo ratings yet

- Heart, Circulation, and Blood Unit Test: Biology 11 April 3, 2014Document8 pagesHeart, Circulation, and Blood Unit Test: Biology 11 April 3, 2014api-279500653No ratings yet

- Cardiovascular System (Anatomy and Physiology)Document93 pagesCardiovascular System (Anatomy and Physiology)Butch Dumdum86% (7)

- CHAPTER Respiration and CirculationDocument5 pagesCHAPTER Respiration and CirculationlatasabarikNo ratings yet

- Unenhanced MR Angiography: Martin Backens and Bernd SchmitzDocument20 pagesUnenhanced MR Angiography: Martin Backens and Bernd SchmitzEka Setyorini .A.No ratings yet

- Cardiomyopathy: Mrs. D. Melba Sahaya Sweety M.SC Nursing GimsarDocument55 pagesCardiomyopathy: Mrs. D. Melba Sahaya Sweety M.SC Nursing GimsarD. Melba S.S ChinnaNo ratings yet

- ECGDocument41 pagesECGmiguel mendezNo ratings yet

- Blood Pressure ChartDocument5 pagesBlood Pressure Chartmahajan1963100% (1)

- Peran Perawat Pada Pemeriksaan Penunjang IVUS, OCT (Imaging)Document31 pagesPeran Perawat Pada Pemeriksaan Penunjang IVUS, OCT (Imaging)Miftahul HudaNo ratings yet

- Nursing DiagnosisDocument3 pagesNursing DiagnosisKat Napoleon75% (4)

- Report-Ecg Ctscan G3 Friday PDFDocument25 pagesReport-Ecg Ctscan G3 Friday PDFTrí Tạ MinhNo ratings yet

- Love Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)From EverandLove Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDFrom EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (29)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionFrom EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (404)