Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Thinking Spatial Networks Today:: The Vastu Shastra' Way

Uploaded by

SuvithaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Thinking Spatial Networks Today:: The Vastu Shastra' Way

Uploaded by

SuvithaCopyright:

Available Formats

SSS10 Proceedings of the 10th International Space Syntax Symposium

046

Thinking spatial networks today:

The ‘Vastu Shastra’ way

Priyambada Das

Space Syntax, London

priyambada.archi@gmail.com

Prachi Rampuria

Paul Davis & Partners, London

rampuria.prachi@gmail.com

Abstract

This paper is based on the conjecture that, often successful, well-functioning cities or urban areas are

the outcome of a heuristic approach to design - an accumulation of trial and error of spatial networks

over centuries. Such has been the case of traditional Indian cities like Madurai, one of the oldest

continuously inhabited cities in the world; and Jaipur, which was built in the beginning of eighteenth

century.

A common denominator for the inception of these cities has been the principles of Vastu Shastra, the

ancient Indian science of town planning and architecture, aimed at achieving a balance among

functionality, bioclimatic design, religious and cultural beliefs (Ananth, 1998). These Vastu principles

having survived centuries of socio-economic, political and cultural changes, in the form of these

cities, embed within themselves the essential DNA of an efficient and robust structure for

settlements. However, instead of learning from such cities, planning practitioners and academics in

the discipline have been incurious about the reasons of overwhelming resilience of

these cities. Decoding this DNA could potentially give us a deeper understanding to the design of

effective and resilient spatial network.

Therefore, taking Jaipur and Madurai as empirical case studies, this paper aims to

decipher their DNA, compare and contrast them in form of a framework of principles that have

contributed to the resilience of their spatial networks, over centuries. This is done using various

syntactic techniques, which allows us to objectively analyse spatial networks. Understanding the

commonalities and differences between spatial structures, in comparison to the current best practice,

the paper concludes its transferability in current urban context.

Keywords

Spatial network, decoding DNA, Vastu Shastra, resilience, space syntax.

1. Introduction

Vastu Shastra is one of the oldest Indian ideology based sciences, which has been established for six

thousand years. The overriding theme of Vastu is a connection between functionality,

auspiciousness and nature wherein one keeps the other alive (Ananth, 1998). The merits of its

P Das & P Rampuria 46:1

Thinking spatial networks today: The ‘Vastu Shastra’ way

SSS10 Proceedings of the 10th International Space Syntax Symposium

counter parts like Feng Shui and Geomancy are already well known to the western world 1. It is hard

to capture Vastu Shastra in a simple definition, as people have approached it in many different ways:

‘‘Vastu is the art of living in harmony with the land, such that one derives the greatest benefits and

prosperity from being in perfect equilibrium with Nature ’’(Acharya, 1981, p.14).

“Vastu Shastra is a highly refined method of creating a living space which is a miniature replica of the

cosmos as perceived by the Vedas 2. It is about emulating the attributes of the cosmic space, about

bringing the divine sentinels of cosmic directions into our homes, about creating harmony by

creating a living environment where the forces of nature are balanced and at peace with each

other”(Gupta, 1995, p.20).

The metaphysical and philosophical nature of Vastu Shastra was rooted since the ancient times and

had a significant importance in the Indian way of living. For centuries, Indian people relied on Vastu

Shastra to design cities and settlements, builds homes, temples, and palaces. Historically, it has had

great contribution towards the environmental design and town planning of many cities that still

flourish even today. Having survived centuries of socio-economic, political and cultural changes,

these cities embed within themselves the essential DNA of an efficient and robust structure for

settlements.

However, most of the planning practitioners and academicians in India are incurious about the

overwhelming resilience of cities designed according to Vastu. Presently, Vastu is largely regarded as

a pseudo-science, as its theories are based on a complex system of philosophy, astrology, intuition

and superstition. They can only be partly explained by modern scientific principles. But we feel this

is a rather pessimistic view towards the whole subject, and this ancient science might deserve more

positive attention than merely calling it backward, ancient and superstitious.

2. Research aims and objectives

Therefore, our research aim is to analyse the structure of cities designed according to Vastu, using

the syntactic methods of space syntax. This would allow us to objectively decipher the spatial

structure built on the tenets of this ancient ideology based science, and consequently understand its

relevance in the current urban context.

To achieve our aim, therefore, the first objective of this research is to understand the ideologies and

concepts of Vastu in relation to urban design and way of life. Furthermore, their spatial implications

on design of selected case examples are studied.

The second objective is then to empirically assess the spatial structure of selected case examples

using space syntax techniques. This would help us decipher the genetic code of spatial structures

based on Vastu that have evolved and expanded ever since.

Finally, the third objective is to study the evolution of the selected case examples over time to

understand the notion of resilience that was embedded in their very spatial network.

3. Methodology

Based on the objectives, the methodology and contents of the research is divided into three parts.

The first part introduces Vastu Shastra, its ideologies, origins, and the fundamental principles in

relation with urban design. As mainly two schools of Vastu Shastra flourished in ancient time, this

research includes, as case examples; the of Madurai, based on Dravidian (south Indian) school of

Vastu Shastra and Jaipur, which was designed according to the Nagara (north Indian) school of Vastu

Shastra. Having survived centuries of socio-economic, political and cultural changes these cities bear

testimony of resilience and adaptability of spatial structure over time. Madurai is one of the world’s

1As per ancient scriptures, Chinese monks carried Vedic knowledge with them, which gradually evolved as

FengShui

2Oldest scripture of Hinduism

P Das & P Rampuria 46:2

Thinking spatial networks today: The ‘Vastu Shastra’ way

SSS10 Proceedings of the 10th International Space Syntax Symposium

oldest continuously inhabited cities and Jaipur being built in the 18th century still continues to thrive

and expand.

Having gained an understanding of the application of Vastu rules on the spatial structures for both

cities, the second part uses syntactic methods such as spatial accessibility analysis, multi-scale

analysis, block size analysis and intelligibility study to empirically assess their spatial structures.

Spatial accessibility analysis helps to find out the most chosen or integrated routes within a system,

whereas multi scale analysis gives understanding of movement across scales. Block size analysis

examines the permeability of urban system and intelligibility study shows legibility of the urban form.

It should be noted, with British invasion, the Vastu schools gradually dissolved and after a point in

time, these cities were no longer designed according to Vastu principles. Therefore, the spatial

extent of the case examples studied in this section is limited to the physical extent of the cities that

was designed as per Vastu.

The third part of the research tries to find out how these historic cores perform in present urban

context. It uses spatial model of the entire city and examines importance of the historic core by

looking at its integration and choice measures. The above-mentioned steps will help us to gain a

better understanding of the very first conjecture regarding heuristic approach to design.

4. Ideologies and principles of Vastu Shastra

In Vastu Shastra, the under structure of any design concept emerged out from a philosophic frame of

the phenomena of Existence, Space and Time. The phenomenon of Existence is underpinned by the

philosophy that all things and their existence are inter-connected. So, the existence of one affects

the other. The phenomenon of Space is conceptualized as a dynamic element made of energy

particles, wherein the main aim is to create an environment that is in harmony with this subtle

energy; and lastly, the ‘notion of Time with regard to cosmos and human life have been explained to

coalesce all processes and movements of the universe’(Parikh, 2008, p.28). Based on these

ideologies, the built form was designed to be in harmony with the forces of the universe.

According to Parikh and Danielou, Hindu philosophy, its origin, has always maintained that the

interpretation of all three phenomenon in continuum leads to an intrinsically dynamic worldview

and that they are absolutely essential in order to understand the Indian view of the universe and the

forces that affect human life. Any aspect of the manifest world exists in space, the terminologies

being mutually definitive. Time is a dimension of space and therefore inseparable from it. ‘Space and

Time together form a continuum that regulates each form of existence’ (Parikh, 2008, p.35).

Therefore, it can be said that these are not independent phenomenon, but part of a greater

continuity, where a seamless cycle of one transforming the other goes on eternally. This makes the

continuum of Existence, Space and Time the philosophical frame of Vastu Shastra that finds direct

manifestation in the art of urban design and architecture.

The interaction between the three basic phenomena of Existence, Space and Time were also

considered to be deeply rooted in the way of life and moral values of the Indian people. According to

Parikh (2008, p.47) ‘every action of the people reveals their response to the Hindu philosophy based

on the interaction of these basic phenomena’. This makes it clear that the spatial organizational

principles of Vastu Shastra ensured that the design of physical spaces responded to the cultural

values and way of life of the people. Through literature and experts, it can be gathered that, these

spatial organizational principles, based on the interaction of the three phenomena, can be expressed

through four key concepts; that informed layout and consequently, the structure of cities (Parikh,

2008; Danielou, 1964; Radhakrishnan, 1951; Vatsyayan, 1991):

1. Co-existence of systems and relative wholeness: Stemming from

the individual identity of the underlying ideologies and their seamless continuity, Vastu believes

that the components of the physical environment also needs to be complete entities in their

context; creating individual centres in continuum wherein each centre is defined by several

other sub-centres. This again contains smaller sub-centres, each connected to one another in

order to reflect the order of the cosmos. Thus, connectivity and relative wholeness become one

P Das & P Rampuria 46:3

Thinking spatial networks today: The ‘Vastu Shastra’ way

SSS10 Proceedings of the 10th International Space Syntax Symposium

of its organizational principles and was applied by the use of Vastu Purusha Mandala 3 (Figure

1a). In Hindu literature where the relationship between the Mandala and urban planning is

explored, it is suggested that the sacred geometry of the Mandala is essential to establish a

secure claim within an active landscape.

2. Individuality within a group: As much as all forms of existence and

space can be understood in terms of a system of concentric wholes, centres and sub-centres,

each of them have a degree of centeredness; implying independent identities. ‘They have their

own regulating systems and specific characteristics that are different from others and make an

individual statement’ (Parikh, 2008, p.55). But, no matter how distinct, each element forms a

part of each other. The underlying meaning in terms of Vastu Shastra therefore implies how

individual buildings or parts of a larger city, even though having an independent identity, need

to coexist harmoniously in order to contribute to the overall greater identity of the town or city;

making it another of its key organizational principles.

3. Coexistence of extremes and celebration of junctures: All

conceptions of Space and Existence are based on the principle of bipolar manifestation,

wherein the extremes are considered to be merely different aspects of the same phenomenon,

working in a intercommunicative unity and forming a continuum over Time. One is dependent

on the other for its existence and effectiveness. Maintaining a balance between the extremes

was considered crucial for all aspects of life, including built form. Since Space was believed to

be made of energy, this coexistence related to the five kinds of energies namely, ether, air fire,

water and earth - the ‘Panchbhootas’. The perfect environment according to Vastu is one

where there is a balance of all the energies enhancing mutual existence. This unification of

relationships between extremes in the built environment automatically puts a lot of

importance to the design of transitions, junctures and thresholds.

4. Timelessness of space: As per the experts, Vastu believes in the

concept of multi-layering of Time reflected in the Space as changes within a spatial frame,

where the ‘resultant space evolves its independent identity though carrying the shadows of the

original one’ (Parikh, 2008, p.67). This concludes adaptability of space with layering of time as

one of the organizational principles. This principle works in conjunction with the Vastu belief of

being sensitive to the natural context and using the resources of the area sustainably in order

to be in tune with the space time continuum.

The application of the above in shaping of the urban form and structure of the cities of Jaipur and

Madurai is explained briefly as below.

5. Application of Vastu principles in Madurai

The actual chronology of Madurai’s early existence is impossible to construct for lack of direct

evidence. However, its roots can be traced back to the 1st millennia B.C and is associated with the

Pandyan dynasty. Simply put, the city’s urban form is a series of concentric streets about a central

temple complex (Figure 1d). ‘Nowhere visible as a whole, the organization is experienced only

gradually over time’ (Smith, 1969, p.11). According to Smith (1969), ‘what is striking is the use of a

fairly simple underlying geometry to express important attitudes towards collective dwelling’. But in

Vastu terms this would have needed to be the adaptation of the ‘Vastu-Mandala’ and by extension

the ideologies of the Hindu philosophy.

In terms of urban layout, the strict geometry of the mandala does not necessarily translate into a

literal ground plan. As per the experts, the Vastu Mandala diagram is meant to explain rather than

represent. Madurai is not a city having a rigid grid pattern as its urban form; the basic pattern ‘here

is distorted’ (Smith, 1969, p.15). This distortion was the response to the natural landscape and

topographical features suggested in the Tiruvilaiyadal Purana’s 4 description of Madurai’s early

fortifications. Its interpretation by Venkatarama Ayyar suggests that the walls of the fort were

3A symbolic diagram representing model of the Universe

4Ancient Hindu script

P Das & P Rampuria 46:4

Thinking spatial networks today: The ‘Vastu Shastra’ way

SSS10 Proceedings of the 10th International Space Syntax Symposium

constructed, as the natural topography of the land would permit. ‘With the river on one side,

mechanical symmetry of the layout for the walls would have to be purchased at a very high price’

(Smith, 1969, p.26). The plan thus included several deflections and zigzag shape.

Figure 1a-d: (a) Vastu Purusha Mandala– Brahman (Hindu God) in the form of a Purusha (cosmic man or person)

inside the model of the Mandala, a square representing the universe (Source: Murugan et al., 2007); (b)

Mandala being used for various configurations and layout illustrating Brahman as the nucleus of Mandala

(Source: Gupta, 1995); (c) Various town plans following the notion of Mandala (Source: Acharya, 1980); (d)

Historic city of Madurai (Source: Smith, 1969)

However, as per Smith, topologically significant interrelationships of parts were kept intact. The

intricate network of connected pathways within the larger divisions of the city have many places

where the narrow streets open up and small neighbourhood centres exist, much quieter than the

bustle of the main arteries. This quality of connectivity and relative wholeness is also expressed in

the festival processions, which take place in the concentric streets and thus delineate the Mandala

over the course of the year. Symbolic of its identity, it ‘reconfirms the underlying form and its use as

a principle reference for the community’s sense of itself in space and time’ (ibid).

According to Smith and Ayyar, the predominant central core, maintains an unusual quality of

presenting itself as a ‘single integrated phenomenon’. Yet, Madurai has a rich diversity within it for

local interventions and distortions. ‘The direct involvement with a place at human scale is critical to

the understanding of how the principle of ‘individuality within a group’ was reflected through the

urban form. The residential enclaves retain an almost village like character. This process of city

buildings as village aggregation became a method of combining disparate groups each retaining its

local identity within the larger whole. Just as the Mandala is locked in place by specific deity

allocations, so Madurai exhibits the analogous distribution of trade groups, giving a ‘cross-grain

identity’ to the pattern and enhancing the sense of both individuality and orientation within the

urban form.

The larger streets, the main corridors of the city, have their own character. Their gentle meandering

softens the momentum of movement along them. This relaxation occurs especially at the corners of

the large concentric avenue, which are demarcated for special events or rendered of a special

character using physical elements such as a tree to create a distinct sheltered environment. This can

be directly related to the principle of sensitive treatment of transitions, nodes and junctures as part

of the city building process.

P Das & P Rampuria 46:5

Thinking spatial networks today: The ‘Vastu Shastra’ way

SSS10 Proceedings of the 10th International Space Syntax Symposium

Having a brief understanding of the adaptation of the principles and ideologies of Vastu on the urban

form of Madurai, we now move to the city of Jaipur.

6. Application of Vastu principles in Jaipur

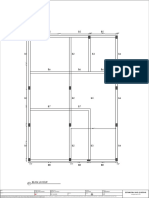

The principles of being sensitive to the natural context and its natural resources to guide the urban

form can be seen in the city of Jaipur as well (Figure 2a). As per the experts, the land being flat, the

layout of the streets is fairly regular and their orientation is in accordance to the ‘prevalent winds

and light of the sun and moon’ to ensure the ‘purity of streets’ (Acharya, 1981, p.45). The

dimensions and form of the Mandala can also be seen to have been affected by the presence of

natural features like hills, woodlands and lakes within the site.

Figure 2a-c: (a) The site for Jaipur with its natural features, ascertaining of the cardinal direction, overlaying of

Mandala and modification of Mandala to accommodate the natural features; (b) Individual wards or Chawkris of

Jaipur given a specific name akin to their identity and streets given specific names according to their functions

(Source: Sachdev, 2002); (c) City of Jaipur, where the superimposed Mandala is divided and subdivided by the

street layout to form a hierarchy of wards, neighbourhoods, blocks, and individual buildings, each being a whole

yet part of a larger whole. (Source: Parikh, 2008)

A structure of relative wholeness is observed in the planning of the city of Jaipur. Jaipur was divided

into nine squares (Paramasiya Mandala) by streets, creating large city wards (Sachdev, 2002). These

were then divided into neighbourhoods made up of cluster of houses that led to individual houses.

The buildings were designed as a set of rooms around a courtyard, which was the centre of all

activities. Thus the whole city was designed in terms of ‘cells within a set of cells’ (ibid). All individual

units were whole yet linked to the larger whole by the network of streets and open spaces. This

connected spatial network was in response to the Vastu principle that it is essential to maintain

‘satatya’ or continuum in the ‘anukram’ or hierarchy of streets and open spaces in accordance to

how the supreme creator has made the universe where all things are connected to one another.

According to Vastu expert Arun Naik, just as each individual God is given their own identity and

recognition in the Mandala; Jaipur’s urban form considers the distribution of landmark elements like

the temple, palace, and city gateways to ensure individuality in the overall city fabric. They not only

served as landmark in themselves but also gave a distinctive character to the areas around. Most of

them were overlaid with religious and spiritual meaning to ensure that they were respected by the

generations. The same was done in the city of Madurai through the use of Gopurams 5. Individual

5monumental tower at the entrances of Meenakshi Amman Temple

P Das & P Rampuria 46:6

Thinking spatial networks today: The ‘Vastu Shastra’ way

SSS10 Proceedings of the 10th International Space Syntax Symposium

wards or ‘chawkris’ were given specific names akin to their identity. Similar to the city of Madurai,

often they were named suggestive of the kind of activity that the street or open space was

associated with, and by extension in relation to the occupation or trade that the community was

associated with within a particular part of the city. It should be noted the Vastu principles were

applicable at all scales ranging from the city’s spatial network to the detailed design of streetscape,

buildings and architecture. However, for the purposes of this paper we are more concerned with the

application of Vastu on shaping of the city’s overall spatial network.

7. Analysing spatial structure of Jaipur and Madurai

Previous section shows how sacred ethos of Vastu led to certain geometry or spatial order in

Madurai and Jaipur. It will be interesting to understand beyond cosmological connotation how these

cities were experienced and used by the inhabitants. Therefore, this part of paper reflects on spatial

structure of the cities that resulted from specific ordering of space. This research attempts to decode

the DNA of these two cities by answering the following questions. How people used to navigate in

the spatial system? How land use or distribution of activities was influenced by such movement

pattern? How parts and whole correspond to each other? As design of cities often mirrors how a

society works, by analysing the spatial structure this research also aims to gain some insight into the

former social system. It tries to find out how social hierarchy was manifested in the spatial structure.

And how positioning of important urban elements within the spatial network reflect the then social

system?

Spatial accessibility analysis of Madurai (Figure 3) shows, though Meenakshi Amman Temple is

located at the core of concentric streets, it is not the most integrated 6space in the system. Instead

South Masi Street gets highlighted as the most integrated space in the city. South Veli Street also

possesses high integration value.

Figure 3: Spatial accessibility _ normalised integration, Madurai (Source: Author)

Multi scale analysis of NACh_n and NACh_R800 (Figure 4) illustrates among four concentric streets

Masi Street is the most often chosen 7 route for both local and global movement. The outermost Veli

Street is mostly preferred at global scale, though East and South part of Veli Street show high choice

6‘Integrationis a normalized measure of distance from any space of origin to all others in a system’. It shows

how close the space is to all other spaces.(source: http://otp.spacesyntax.net/term/integration/)

7Choice represents ‘how likely it is to be passed through - on all shortest routes from all spaces to all other

spaces in the system.’ (source: http://otp.spacesyntax.net/term/choice/)

P Das & P Rampuria 46:7

Thinking spatial networks today: The ‘Vastu Shastra’ way

SSS10 Proceedings of the 10th International Space Syntax Symposium

value even at local scale. Also, East Chitrai Street adjacent to Pudhu Madapam (old market) and

West Avani Moola Street are well chosen for global movement. The most interesting finding of this

analysis is the correlation between choice value and commercial activity. Overlapping of highly

chosen routes (NACh value greater than 1.2) on current land use plan shows, majority of the city’s

commercial activity has flourished along these routes. One can also argue that scale of movement

has some influence on the character of trade that developed along the streets. Clustering of trade

groups along specific streets, such as cloth merchants in South and East Chitrai Streets, paper

merchants in East Avani Moola Street, goldsmith and jewellers in South Avani Moola Street and grain

merchants in East Masi Street supports this fact (Smith, 1969). Such distribution not only reflects the

notion of ‘individuality within a group’ but also portrays how caste system 8was manifested in the

spatial layout.

Figure 4: Multi-scale analysis, Madurai (Source: Author)

Presence of Gopuram or monumental tower at the entrances of Meenakshi Amman Temple provides

a good sense of orientation in the city. The question remains, whether spatial layout also contributes

in legibility of the city. Or how intelligible the city form is? Figure 5a shows Madurai has an

intelligibility 9 value of 0.159 which implies it is not very easy to interpret the whole system from its

parts. In other words, if we ignore the presence of ‘Gopuram’, the city layout does not give enough

clues for orientation. Smith’s narrative (1969, p.65-66) makes this argument even stronger, ‘...major

streets and axes are not acknowledged with uniform facades or controlled vistas.....There is nowhere

within the public realm that one gets an overall view of the city’s layout....The bends in the streets

hide their extent; small streets radiating from the gopurams twist and turn...Madurai unfolds its

secrets only through moving rather than stationary encounter. It is true experiential space in Choay’s

terms...the city diagram is not itself an object of attention....’

8The caste system refers to classification of people into different hierarchy according to their occupation

9‘Intelligibility

is calculated by correlating connectivity with integration at the infinite radius...’ (source:

http://otp.spacesyntax.net/term/intelligibility/)

P Das & P Rampuria 46:8

Thinking spatial networks today: The ‘Vastu Shastra’ way

SSS10 Proceedings of the 10th International Space Syntax Symposium

Figure 5a-b: (a) Scatter plot of integration and connectivity, Madurai (Source: Author); (b) Scatter plot of

integration and connectivity, Jaipur (Source: Author)

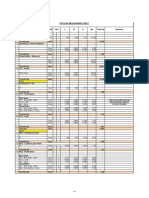

Cities designed according to Vastu principles followed certain measuring system as prescribed in the

ancient script of Manasara. ‘Danda’ and ‘Hasta’ 10 were the units of measurement for town planning

in India (Funo et. al., 2002). It will be interesting to find out which type of urban grain resulted from

such measuring system. Block size analysis of Madurai’s historic city (Figure 6a) illustrates majority of

blocks have perimeters ranging from 200m to 400m. The next most common range of perimeter lies

within 400m to 600m. And this indicates the system is fairly permeable (possible to cover in 5-6

minutes) and therefore convenient for pedestrian movement.

Figure 6a-b: (a) block size analysis, Madurai (Source: Author); (b) block size analysis, Jaipur (Source: Author)

However, when important city elements were superimposed on spatial model of the city, some

degree of randomness were observed in their syntactic values 11. In contrast to Karimi’s study (2012,

p.46) which shows correlation between importance of city elements and their respective position in

the spatial structure; example of Madurai illustrates syntactic value of the elements do not

necessarily reflect their importance in society. And the probable reason behind such deviation is,

both Iranian and English old cities have evolved organically with time, whereas, Madurai emerged

from the unique form of Mandala, which contains metaphysical meaning. As the city depicts

macrocosmic notion of ‘space time and existence’ through its physical form, location of many city

elements was predetermined.

City Elements Name NAInt_n

Temple Madanagopalasami Temple 1.4

Kings Palace Tirumala Nayak Palace 1.39

Market/Entrance hall to temple Pudu Mandapam 1.37

Temple Perumal Temple 1.36

10One Danda = 4 Hasta = 6 Feet (approximately)

11‘…calculated

by averaging the values of the lines that are parts of these elements or adjacent to them’ (Karimi,

2012, p .45)

P Das & P Rampuria 46:9

Thinking spatial networks today: The ‘Vastu Shastra’ way

SSS10 Proceedings of the 10th International Space Syntax Symposium

Temple Meenakshi Sundaresvarar Temple 1.31

Market Central Market 1.21

Water tank Perumal Temple Teppakulam 1.11

The above table shows though Meenakshi Sudaresvara Temple is the most significant city element it

is not located at the most integrated part of the system. Whereas Kings Palace, which can be

regarded as subordinate to the temple, both according to caste hierarchy and its influence on the

society; is located in a position with higher integration value. Similarly, Madanagopalasmi Temple

and Perumal Temple though less important than Meenakshi Sundaresvara Temple, have better

integrated position within the system. Pudu Mandapam, the old market place which is also

associated with some important religious ceremony, is thus located in the vicinity of the temple,

instead of at the most integrated part of the system.

Deciphering spatial structure of Jaipur, which was built in a later stage than Madurai, will give us

better understanding of Vastu principles. Comparison between the spatial structures of these two

cities will also demonstrate how Vastu principles were applied or modified over time.

Spatial accessibility analysis of Jaipur (Figure 7) shows the busiest street in the city which connects

Chandpole Darwazaa (gate) on the West to Surajpole Darwazaa on the East has the highest

integration value. Along this street, which was a long established route from ancient times, many

markets such as Chandpole Bazar, Tripolia Bazar, Ramganj Bazar, Surajpole Bazar have flourished. As

expected, multi scale analysis of NACh_n and NACh_R400 (Figure 8) reveals this street has high

choice value both at local and global scale. Roads perpendicular to this main street also get

highlighted in this analysis. For example Kisanpole Bazaar road, Johari Bazar road and Gangauri

bazaar road are highly chosen for both global and local movement, GhatDarwaza Bazar road is

chosen for local scale movement.

Figure 7a-b: (a) Spatial accessibility _normalised Integration, Jaipur (Source: Author); (b) Different wards of

Jaipur (Source: Author)

P Das & P Rampuria 46:10

Thinking spatial networks today: The ‘Vastu Shastra’ way

SSS10 Proceedings of the 10th International Space Syntax Symposium

Figure 8: Multi scale analysis, Jaipur (Source: Author)

Similar to Madurai, clustering of same trade groups can also be found in Jaipur and often the name

of the streets reflects a specific trade. Gheewalo 12karasta (road), Haldiyon 13karasta, Jhalaniyon 14

karasta are few examples which get highlighted in the multi scale analysis as they have high choice

value in both local and global scale. It should be noted, as public access was limited to the ‘walled

city’ or the palace complex of Jaipur, this area has not been included in the spatial model of historic

city core.

Though grid iron pattern of streets in Jaipur is quite different from Madurai’s concentric

arrangement of street, both the cities perform similarly in terms of intelligibility. Scatter plot of

connectivity and integration (Figure 5b) shows Jaipur has intelligibility value of 0.148, which is lower

than Madurai. However, unlike Madurai major streets in Jaipur has quite unique facade treatment,

which helps a person to orient himself within the system. Architectural features such as strong

horizontal lines of chhajjas (sunshades), projecting vertical blocks on brackets, modular system of

arches filled with latticed screens, use of pink sandstone 15 as building material give strong identity

and cohesiveness to the major streets. As described by Mehrotra, (1990, p.23)

‘Starting from the city wall, as one traverses the city along the main avenues or bazaars, the overall

structure and cohesiveness of the city becomes evident ...Yet, when you enter a mohalla 16, the

informality (the break from the pink colour) is startlingly wonderful – irregular streets, wayside

shrines, hawkers – the entire microcosm of chaotic urban India.’

The block size analysis (Figure 6b) shows similar to Madurai, the predominant block size in the oldest

part of Jaipur that includes Purani Basti, Topkhanadesh, Modikhana, Visheshvarjivaries from 200m to

600m. It indicates easy walkability of the city core.But as one moves through Ghat Darwaja,

Ramchandra Colony and Topkhanahazuri, (Figure 7a) which are believed to be later addition, the

urban grain changes to a great extent. These areas become less permeable as one can find big and

irregular blocks.

Overlay of important city elements on the spatial model of Jaipur reveals they are mostly located in

the integrated part of the system.It can be argued; though both the cities were based on Vastu

12people involved in the trade of clarified butter

13people involved in the trade of turmeric

14people involved in the trade of ground spices

15Jaipur is also known as pink city

16Residential neighbourhood

P Das & P Rampuria 46:11

Thinking spatial networks today: The ‘Vastu Shastra’ way

SSS10 Proceedings of the 10th International Space Syntax Symposium

principles, design of Madurai gave more importance to the metaphysical aspects, whereas Jaipur

shows a more rational approach while applying Vastu principles. This in turn supports our initial

hypothesis of heuristic approach to design. It can be conjectured trial and error over centuries,

learning from Madurai led to a more logical and improvised version of Vastu application in Jaipur.

The similar opinion is found in Smith’s writing, (1969, p.84)

‘The pattern of Madurai seems a less obvious but more interesting interpretation of the tradition

represented by the Shastras. The later date of city’s 17 layout and the existence there of a celebrated

astronomical observatory, perhaps suggest an emerging new world order, with its own

interpretation of the cosmos.’

City elements Name NAInt_n

Temple Laxmi Narayan Temple 2.08

Public open space ChotiChaupar 18

1.88

Public open space Badi Chaupar 1.85

Palace of the Winds 19 Hawa Mahal 1.63

Entrance gate to city palace complex Sireh Deori Gate 1.63

8. Relevance of historic cores in present urban context

Spatial model of present day Madurai (Figure 9a) shows the historic city core is still an integral part

of the whole system. It gets highlighted as the most integrated part of the spatial structure. Spatial

accessibility analysis (Figure 9b) illustrates South and East Masi Street are well chosen for global

movement. Veli Street also has high choice value. Both the factors help to thrive the commercial

activities along these streets while keeping heavy traffic flow away from the main temple precinct.

Figure 9: Spatial accessibility analysis, present day Madurai (Source: Author)

17Reference of Jaipur

18Chowk, used for public gathering

19Five storey high structure from where royal women used to watch day to day events or royal processions

happening on the street

P Das & P Rampuria 46:12

Thinking spatial networks today: The ‘Vastu Shastra’ way

SSS10 Proceedings of the 10th International Space Syntax Symposium

Figure 10: Spatial accessibility analysis, present day Jaipur (Source: Author)

Similarly, historic part of Jaipur still acts as the spatial and functional core of the whole city. Figure

10a affirms the fact that it is the most integrated part of the system. Spatial accessibility analysis

(Figure 10b) also shows the old market streets still possess high choice value which allows these

areas to remain busy even today.

Unlike many historic towns in the world, both Madurai and Jaipur are functioning well in present

urban context. Without losing importance; these spatial structures have sustained many cultural,

social and economic changes. And this proves the robustness and resilience of these age-old systems.

8. Conclusion

In conclusion, we would like to revert back to the aim of this research paper to understand the

relevance of Vastu in the current urban context. To do so, we compare them with current western

urban design best practise.

If we put aside religious overtone of Vastu and focus on its heuristic approach to design, we can find

some parallels with western urban design principles. For example, multi scale analysis shows in both

the cities market grew along the streets that possess high choice value at both global and local scale.

This finding reemphasizes the fact that, spatial configuration and multi scale accessibility play key

roles in developing and sustaining retail activities.

Urban block size analysis illustrates, majority of urban blocks in the historic core of Madurai and

Jaipur have perimeters ranging from 200m to 600m. Similar dimensions can also be found in western

urban design standard which suggests blocks of 60-90m X 90-120m provide the optimum dimensions

to support good pedestrian accessibility (Yeang, 2007, p.65).

The study also reveals, in both the cities land use, caste, professions were organised and distributed

along streets that provided the best affordance for it. It is evident, streets played important role in

building a sense of community and creating unique identity of a place. Even architecture and

townscape of key streets was given special importance such as in the case of Jaipur, to develop a

coherent image of the city. Similar approach can be found in current western urban design thinking,

as explained by Porta & Romice (2010, p.15)

“Planning strategies, especially those related with coding, should acknowledge....that the unit of

analysis and coding is the STREET FRONT, rather than the BLOCK.”

P Das & P Rampuria 46:13

Thinking spatial networks today: The ‘Vastu Shastra’ way

SSS10 Proceedings of the 10th International Space Syntax Symposium

The research shows both Madurai (0.159) and Jaipur (0.148) possess less intelligible spatial structure.

If we compare these values with Bill’s research, (2001, p.4) which discusses intelligibility of different

cities around the world, we find Madurai and Jaipur are comparable to Arabic cities (0.160) from

intelligibility point of view. Further research is needed to find whether low intelligibility only relates

to cities designed as per Vastu or is it a common feature of historic cities in general. It is also a

question of understanding how can one embed the quality of legibility even though the spatial

structure does not strongly contribute to it, like Madurai had its gopurams to give an overall sense of

orientation, corresponding to the European church spires? Effectiveness of legibility as a scalar

quality in design? Such questions can be food for further thought.

The above findings point towards the compatibility of Eastern belief with Western approach. We

believe that these findings are valuable to the development of both Vastu Shastra and Western

Urban Design principles. It reinforces that this Indian philosophy is not just mere superstition, since

parallels can be drawn with the rational Western Urban Design principles. This makes it a powerful

piece of evidence against the way urban development is happening today in most countries under

the influence of globalisation and modernism.

Although Vastu Shastra and Western Urban Design principles seem to be fundamentally compatible,

with the core values of both approaches largely overlapping; yet each have its own sanctity,

establishing the fact that each and everything do not find their exact equivalent in the other.

Therefore, it is probably for the best that they should be left to operate in their own spheres due to

consideration of the cultural aspects. It might be more advantageous to apply Vastu in an eastern

country due to the acceptance of the subject and its appreciation in the local culture. Similarly, it

might be more convincing to apply rational Western Urban Design principles in a western country,

without having to understand the symbolic implications of Vastu Shastra.

Coming now more specifically to the Indian context; apart from quantitatively analysing the

structure of Madurai and Jaipur, this research also opened up possibilities for further researches.

Not many studies have been done to determine the benchmark for walkable urban environment in

India. The block size analysis of Madurai and Jaipur could be a good starting point to review and

compare existing standards with historic city cores that are performing well even today. It will also

be interesting to find out how other Indian cities perform in terms of intelligibility, to better

understand Indian cities and its spatial structure from a legibility point of view. Multi-scale analysis

of Jaipur and Madurai, shed light on the need to understand the distribution and correlation of land

use with the spatial structure from both a design and planning perspective, that could significantly

guide future developments.

Keeping in mind the present scenario of Indian cities characterised by unprecedented urban growth

under the influence of globalisation and modernism, where there is absence of proper guidelines for

design and growth of cities; this research attempts to review the applicability and relevance of Vastu

principles. By using space syntax, this study is an endeavour to show its relevance in a scientific and

evidence based way. The paper does not encourage application of Vastu principles without

questioning them; it only tries to ensure that we do not ignore the ancient knowledge, as it has been

enriched by trial and errors over ages.

P Das & P Rampuria 46:14

Thinking spatial networks today: The ‘Vastu Shastra’ way

SSS10 Proceedings of the 10th International Space Syntax Symposium

References

Acharya, P. K. (1981), Indian architecture According to Manasara—Silpashastra, Manasara series, New Delhi:

Oriental Books

Ananth, S. (1998), Vastu: the classical Indian science of Architecture and Design, New Delhi: Penguin books.

Bafna, S. (2000), On the Idea of the Mandala as a governing device in Indian Architectural Tradition; Journal of

the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 59 (1), p. 26- 49

Bhargava, D. S. (2003), Environmental Considerations in Vastu Culture for Residential Building Orientation

[Online]; Available at: http://www.ieindia.org/publish/ar/0404/apr04ar1.pdf [Accessed 2nd June 2010]

Bowmik, A. (1991), Puranic texts on Architecture with special reference to Matsyapurana, unpublished Ph.D

Dissertation, Jadavpur University

Danielou, A. (1964), Hindu polytheism; London: Routledge& K. Paul

Funo, S., Yamamoto, N., and Pant, M. (2002); Space Formation of Jaipur City, Rajastan, India An Analysis on City

Maps (1925-28) made by Survey of India. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, p.261-

269.

Gupta, S. (1995), Vastu Shilpa Shastra: the ancient Indian bio-climatically and socially responsive science of

building; [Online], Available at: http://resume.smitagupta.com/publications/solar99.pdf [accessed 23rd

April 2010]

Hillier, B. (2001), A Theory of the City as Object Or, how spatial laws mediate the social construction of urban

space. 3rd International Space Syntax Symposium. Atlanta: Space Syntax, p.1-28

Jacobs, J. (2004), Architectural Theory of Manasara; Montreal: McGill University, unpublished PhD Dissertation

Jain, N. (2001), Connection between Spirituality and Sustainable Development, M.A. Thesis, University of

Calgary, Alberta

Karimi, K. (2012), A reflection on 'Order and structure in urban design'. In Journal of Space Syntax, p. 38-48

Malville, J. M. and Gujral, L. M. (2000), Ancient cities, Sacred skies Cosmic Geometries and City Planning in

Ancient India, Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for Arts & Aryan books International.

Mehrotra, R. J. (1990), Making Legible City Form, a case for Urban Design. Architecture and Design, p.18-25.

Miester, M. (1979), Mandala and practise in Nagara architecture in North India; Journal of the American

Oriental Society, Vol. 99(2), p. 204- 219.

Murugan et al. (2007), Reinforcing traditional Indian construction with modern structures [Online]; Available at:

http://nopr.niscair.res.in/bitstream/123456789/6287/1/IJTK%208(4)%20633-637.pdf [Accessed 25th

May 2010]

Naik, A. (2008), Vastu Shastra: the divine school of architecture; [Online]; Available at:

http://vastusindhu.com/Vastushastra%20-%20The%20Divine%20School%20ofArchitecture.pdf

[Accessed 27th May 2010]

Parikh, P. (2008), Hindu Notions of Space Making, Ahemdabad: SID Research Cell.

Porta, S., and Romice, O. (2010), Plot-Based Urbanism: Towards Time-Consciousness in Place-Making.

Strathclyde: UDSU – Urban Design Studies Unit, University of Strathclyde, Dept. of Architecture.

Radhakrishnan S. (1951), Indian Philosophy, New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Rampuria, P. (2010), Thinking Urban Design Today - The Vastu Shashtra Way, Revisiting 6000 years of tradition,

M.A. Thesis, Oxford Brookes University.

Roy, A. K. (1978), History of the Jaipur city, New Delhi, Manohar publications

Sachdev, V. et al. (2002), Building Jaipur: the making of an Indian city; London : Reaktion

Smith, J. (1969), Madurai, India: The Architecture of a City, M.A. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Space Syntax (2015), Online Training Platform; Available at: http://otp.spacesyntax.net/ [Accessed 2nd Feb

2015]

Sugirtharajah, S. what makes a ‘Good City’: A Hindu Perspective [Online]; Available at:

http://www.faithsforthecity.org.uk/Papers/Hinduism.pdf [Accessed 21st May 2010]

Ter Mors, A (2007), Vastu Shastra: Architecture in resonance with life [Online]; Available at:

http://www.arcplusonline.com/papers/7010.pdf [Accessed 20th May 2010]

Yeang, L. D. (2007), Urban Design Compendium, UK, Homes and communities agency, p.65

Vatsyayan, K. (1991), Concept of space: Ancient and Modern, New Delhi, IGNCA

P Das & P Rampuria 46:15

Thinking spatial networks today: The ‘Vastu Shastra’ way

You might also like

- Applying Vastu Principles to Smart CitiesDocument21 pagesApplying Vastu Principles to Smart CitiesSneha MajiNo ratings yet

- Between Notion and Reality DoshiDocument6 pagesBetween Notion and Reality DoshiAbraham Panakal100% (1)

- Cultural Heritage Tourism in PunjabDocument26 pagesCultural Heritage Tourism in PunjabDEEPTHI RAJASHEKARNo ratings yet

- Final CDP VaranasiDocument425 pagesFinal CDP VaranasiSudhir SinghNo ratings yet

- Relevance of Ceremonial Practices on Madurai's Urban MorphologyDocument39 pagesRelevance of Ceremonial Practices on Madurai's Urban MorphologyGuru Prasath ANo ratings yet

- Jalandhar CityDocument12 pagesJalandhar CityAnwesha BaruahNo ratings yet

- Ujjain City Development Plan for JNNURM SchemeDocument408 pagesUjjain City Development Plan for JNNURM Schemepriyaa2688100% (2)

- MQ Paper Focuses on Urban DesignDocument2 pagesMQ Paper Focuses on Urban DesignArchana M NairNo ratings yet

- Rural - Urban Interaction A Study of Burdwan Town and Surrounding Rural AreasDocument306 pagesRural - Urban Interaction A Study of Burdwan Town and Surrounding Rural AreasAbhirup Da BadguyNo ratings yet

- BanarasDocument30 pagesBanarasAnurag BagadeNo ratings yet

- Townscape - Gordon Cullen - Module 3Document2 pagesTownscape - Gordon Cullen - Module 3Nymisa RavuriNo ratings yet

- DissertationDocument78 pagesDissertationgowthamithra monishaNo ratings yet

- Urban Design ReportDocument23 pagesUrban Design ReportLakshwanth ArchieNo ratings yet

- Hdre 2014Document397 pagesHdre 2014Basavaraj MtNo ratings yet

- HistoryDocument46 pagesHistoryAdrish NaskarNo ratings yet

- Hriday Reflections - 02Document170 pagesHriday Reflections - 02Ar Afreen FatimaNo ratings yet

- Chennai Urban DevelopmentDocument63 pagesChennai Urban DevelopmentSwati KulashriNo ratings yet

- UD AMS - Harini - Unit 3Document55 pagesUD AMS - Harini - Unit 3Divya PurushothamanNo ratings yet

- New Towns in India - 1Document54 pagesNew Towns in India - 1Piyush GaliyawalaNo ratings yet

- City Profile AhmedabadDocument74 pagesCity Profile AhmedabadHussain BasuNo ratings yet

- Urban Sprawl Pattern MaduraiDocument10 pagesUrban Sprawl Pattern MaduraiShaaya ShanmugaNo ratings yet

- Land Use and Land Cover Mapping - Madurai District, Tamilnadu, IndiaDocument10 pagesLand Use and Land Cover Mapping - Madurai District, Tamilnadu, IndiatsathieshkumarNo ratings yet

- Greater Noida Draft Master Plan 2021Document88 pagesGreater Noida Draft Master Plan 2021Deepankar Juneja100% (1)

- Slum Clearance MaduraiDocument153 pagesSlum Clearance Maduraisurya prakash pkNo ratings yet

- Maratha TanjoreDocument4 pagesMaratha Tanjoreapsrm_raNo ratings yet

- Master Thesis Topics: Urban Planning Projects 2016-2017Document14 pagesMaster Thesis Topics: Urban Planning Projects 2016-2017AlyNo ratings yet

- Urban Planning Students Report On Sustainable Development Plan For Tsunami Affected Cuddlore, Tamil Nadu, IndiaDocument83 pagesUrban Planning Students Report On Sustainable Development Plan For Tsunami Affected Cuddlore, Tamil Nadu, Indiaravi shankarNo ratings yet

- Indian Temple Towns: Group - 4Document25 pagesIndian Temple Towns: Group - 4Hisana MalahNo ratings yet

- SEO Vaastushastra GuideDocument7 pagesSEO Vaastushastra Guidefalguni reddyNo ratings yet

- Seminar On Temple ArchitectureDocument82 pagesSeminar On Temple Architecturecrazy_2010No ratings yet

- Anagha Koenigsberger 130625125800 Phpapp01Document15 pagesAnagha Koenigsberger 130625125800 Phpapp01ASHFAQNo ratings yet

- 416 13 Singh Rana P B 2013 Indian CultuDocument26 pages416 13 Singh Rana P B 2013 Indian CultuCTSNo ratings yet

- OdishaDocument68 pagesOdishaSrividhya KNo ratings yet

- History of Gardening in IndiaDocument2 pagesHistory of Gardening in IndiaDanish S Mehta100% (2)

- CITY DEVELOPMENT PLAN AMRITSAR 2025Document158 pagesCITY DEVELOPMENT PLAN AMRITSAR 2025Nikita PurohitNo ratings yet

- Books Preparation For GateDocument1 pageBooks Preparation For GateRUSHALI SRIVASTAVANo ratings yet

- B.Shyam Sunder-Biography Synopsis and BooksDocument5 pagesB.Shyam Sunder-Biography Synopsis and BooksH.ShreyeskerNo ratings yet

- Review of The Concise Townscape by Gordon CullenDocument3 pagesReview of The Concise Townscape by Gordon CullenDevyani TotlaNo ratings yet

- City Profile of Ujjain Highlights Religious, Cultural and Historical SignificanceDocument10 pagesCity Profile of Ujjain Highlights Religious, Cultural and Historical SignificanceVidyotma SinghNo ratings yet

- Basic Concepts of Vastu For Town PlanningDocument5 pagesBasic Concepts of Vastu For Town PlanningRimjhim SwamiNo ratings yet

- Varanasi Heritage ZoneDocument40 pagesVaranasi Heritage ZoneneeltodownNo ratings yet

- Working Paper - Tracing Modern Heritage in Panjim Landmarks - ChinmaySomanDocument14 pagesWorking Paper - Tracing Modern Heritage in Panjim Landmarks - ChinmaySomanChinmay SomanNo ratings yet

- UD AMS - Harini - UNIT 1Document83 pagesUD AMS - Harini - UNIT 1Divya PurushothamanNo ratings yet

- Creating A Habitat For The Tibetan Migrants in India: A Colony at Dharamshala, Himachal PradeshDocument14 pagesCreating A Habitat For The Tibetan Migrants in India: A Colony at Dharamshala, Himachal PradeshMaulik Ravi HajarnisNo ratings yet

- Strategies For Development of Peri Urban Areas in A Developing Country A Case Study of BhubaneswarDocument6 pagesStrategies For Development of Peri Urban Areas in A Developing Country A Case Study of BhubaneswarEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- James PrinsepDocument13 pagesJames Prinsepgayathrimr68No ratings yet

- Urban Design Lec01 090912Document26 pagesUrban Design Lec01 090912whatever530No ratings yet

- Development Plan for Bhubaneswar CityDocument56 pagesDevelopment Plan for Bhubaneswar CityDnyaneshwar GawaiNo ratings yet

- UjjainDocument201 pagesUjjainjkkar12100% (1)

- Varanasi City ProfileDocument4 pagesVaranasi City ProfileJohn Nunez100% (1)

- Revitalizing Mullassery Canal in KochiDocument2 pagesRevitalizing Mullassery Canal in KochiVigneshwaran AchariNo ratings yet

- Pedestrian Oriented Cities in India Shreeparna SahooDocument11 pagesPedestrian Oriented Cities in India Shreeparna SahooShreeparna SahooNo ratings yet

- 15bar12 - Himanshu - The City of Tommorow and Its PlanningDocument3 pages15bar12 - Himanshu - The City of Tommorow and Its PlanningHimanshu AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Leveling Principles and TechniquesDocument24 pagesLeveling Principles and TechniquesRamkishor SahuNo ratings yet

- The Great Stupa Architecture and SymbolismDocument17 pagesThe Great Stupa Architecture and SymbolismnikitaNo ratings yet

- 1-2 Regionalism and Identity PDFDocument36 pages1-2 Regionalism and Identity PDFOmar BadrNo ratings yet

- Dhola ViraDocument6 pagesDhola ViraayandasmtsNo ratings yet

- KhidrapurDocument3 pagesKhidrapuranup v kadam100% (2)

- Architecture and Heritage of Mysore CityDocument5 pagesArchitecture and Heritage of Mysore Cityroshni H.RNo ratings yet

- PLINTH AREA-1768.00 SQ FTDocument1 pagePLINTH AREA-1768.00 SQ FTSuvithaNo ratings yet

- ROAD - : Open TerraceDocument1 pageROAD - : Open TerraceSuvithaNo ratings yet

- Alan Sir - Master Qty3Document4 pagesAlan Sir - Master Qty3SuvithaNo ratings yet

- For Execution Assignment - 03 Beam Layout NTS 09-10-2020 16RBAR067 SuvithaDocument1 pageFor Execution Assignment - 03 Beam Layout NTS 09-10-2020 16RBAR067 SuvithaSuvithaNo ratings yet

- ROAD - : Living 15"0"X23'6"Document1 pageROAD - : Living 15"0"X23'6"SuvithaNo ratings yet

- Alan Sir - Master Qty1Document206 pagesAlan Sir - Master Qty1SuvithaNo ratings yet

- Improving HeritageManagement in IndiaDocument248 pagesImproving HeritageManagement in IndiaArnav DasaurNo ratings yet

- Study Material-1Document17 pagesStudy Material-1SuvithaNo ratings yet

- BOQ AS PER DOCUMENTDocument5 pagesBOQ AS PER DOCUMENTSuvithaNo ratings yet

- Planning of Madurai and Jaipur cities under 40 charactersDocument12 pagesPlanning of Madurai and Jaipur cities under 40 charactersSuvithaNo ratings yet

- Understanding Heritage Through HistoryDocument9 pagesUnderstanding Heritage Through HistorySuvitha100% (1)

- Alan Sir - Master Qty1Document1 pageAlan Sir - Master Qty1SuvithaNo ratings yet

- Sharma Basicsofdesign DesignED2015Document17 pagesSharma Basicsofdesign DesignED2015Naman JainNo ratings yet

- Neufert 4th EditionDocument608 pagesNeufert 4th EditionAndrej Šetka92% (60)

- Ajanta & ElloraDocument150 pagesAjanta & ElloraSuvithaNo ratings yet

- Ajanta & ElloraDocument150 pagesAjanta & ElloraSuvithaNo ratings yet

- Tourism Tirunelveli PDFDocument70 pagesTourism Tirunelveli PDFArjun BSNo ratings yet

- 4-M.arch Azra Zainab Synopsis PDFDocument5 pages4-M.arch Azra Zainab Synopsis PDFSuvithaNo ratings yet

- Case Study On SrirangamDocument66 pagesCase Study On SrirangamManjula60% (5)

- Sustainability 08 00047 PDFDocument19 pagesSustainability 08 00047 PDFSanjana CholkeNo ratings yet

- LanduseDocument51 pagesLanduseSuvithaNo ratings yet

- Winery SynopsisDocument8 pagesWinery SynopsisSteve Richard0% (1)

- LA VILLE RADIUSE(RADIANT CITY)- city for 3 millionDocument3 pagesLA VILLE RADIUSE(RADIANT CITY)- city for 3 millionSuvithaNo ratings yet

- Stand Points PDFDocument1 pageStand Points PDFSuvithaNo ratings yet

- 3-M.arch Synopsis SakthiDocument6 pages3-M.arch Synopsis SakthiSuvithaNo ratings yet

- 4-M.arch Azra Zainab Synopsis PDFDocument5 pages4-M.arch Azra Zainab Synopsis PDFSuvithaNo ratings yet

- THE CITY OF ROME - AbstractDocument1 pageTHE CITY OF ROME - AbstractSuvithaNo ratings yet

- +4'0" LVL +0'0" LVL: Ground Floor PlanDocument1 page+4'0" LVL +0'0" LVL: Ground Floor PlanSuvithaNo ratings yet

- Toilet 5'1"X9'0" Dress 5'7"X9'0" TREAD - 0'10" RISER - 0'6": 4" SunkDocument1 pageToilet 5'1"X9'0" Dress 5'7"X9'0" TREAD - 0'10" RISER - 0'6": 4" SunkSuvithaNo ratings yet

- Is 5312 1 2004Document13 pagesIs 5312 1 2004kprasad_56900No ratings yet

- Russell Vs Vestil 304 SCRA 738Document2 pagesRussell Vs Vestil 304 SCRA 738Joshua L. De JesusNo ratings yet

- MalayoDocument39 pagesMalayoRoxanne Datuin UsonNo ratings yet

- Case AnalysisDocument4 pagesCase AnalysisAirel Eve CanoyNo ratings yet

- Bachelor of Agricultural Technology Second Semester Horticulture 1 Pre-TestDocument4 pagesBachelor of Agricultural Technology Second Semester Horticulture 1 Pre-TestBaby G Aldiano Idk100% (1)

- Language Learning Enhanced by Music and SongDocument7 pagesLanguage Learning Enhanced by Music and SongNina Hudson100% (2)

- Architecture Research ThesisDocument10 pagesArchitecture Research Thesisapi-457320762No ratings yet

- BS 07579-1992 (1999) Iso 2194-1991Document10 pagesBS 07579-1992 (1999) Iso 2194-1991matteo_1234No ratings yet

- Is College For Everyone - RevisedDocument5 pagesIs College For Everyone - Revisedapi-295480043No ratings yet

- Indexed Journals of Pakistan - Medline and EmbaseDocument48 pagesIndexed Journals of Pakistan - Medline and EmbaseFaisal RoohiNo ratings yet

- Access 2013 Beginner Level 1 Adc PDFDocument99 pagesAccess 2013 Beginner Level 1 Adc PDFsanjanNo ratings yet

- Activity Sheets in Science VIDocument24 pagesActivity Sheets in Science VIFrauddiggerNo ratings yet

- Consumer BehaviourDocument30 pagesConsumer BehaviourManoj BaghelNo ratings yet

- German Modern Architecture Adn The Modern WomanDocument24 pagesGerman Modern Architecture Adn The Modern WomanUrsula ColemanNo ratings yet

- Awards and Honors 2018Document79 pagesAwards and Honors 2018rajinder345No ratings yet

- CatalogueDocument36 pagesCataloguehgwlin100% (1)

- The Complete Motown CatalogueDocument10 pagesThe Complete Motown Cataloguehermeto0% (1)

- Document PDFDocument16 pagesDocument PDFnelson_herreraNo ratings yet

- TULIP ChartDocument1 pageTULIP ChartMiguel DavillaNo ratings yet

- Transiting North Node On Natal Houses - Recognizing Your True SelfDocument9 pagesTransiting North Node On Natal Houses - Recognizing Your True SelfNyanginjaNo ratings yet

- LK 2 - Lembar Kerja Refleksi Modul 4 UnimDocument2 pagesLK 2 - Lembar Kerja Refleksi Modul 4 UnimRikhatul UnimNo ratings yet

- Grade 9: International Junior Math OlympiadDocument13 pagesGrade 9: International Junior Math OlympiadLong Văn Trần100% (1)

- 527880193-Interchange-2-Teacher-s-Book 2-331Document1 page527880193-Interchange-2-Teacher-s-Book 2-331Luis Fabián Vera NarváezNo ratings yet

- Hubspot Architecture Practicum Workbook: ObjectiveDocument4 pagesHubspot Architecture Practicum Workbook: Objectivecamilo.salazarNo ratings yet

- Ritangle 2018 QuestionsDocument25 pagesRitangle 2018 QuestionsStormzy 67No ratings yet

- HG532s V100R001C01B016 version notesDocument3 pagesHG532s V100R001C01B016 version notesKhaled AounallahNo ratings yet

- Antianginal Student222Document69 pagesAntianginal Student222MoonAIRNo ratings yet

- Nelson Olmos introduces himself and familyDocument4 pagesNelson Olmos introduces himself and familyNelson Olmos QuimbayoNo ratings yet

- Advertising ContractDocument3 pagesAdvertising Contractamber_harthartNo ratings yet

- Teacher Professional Reflections 2024 1Document2 pagesTeacher Professional Reflections 2024 1Roberto LaurenteNo ratings yet

- Beginning AutoCAD® 2020 Exercise WorkbookFrom EverandBeginning AutoCAD® 2020 Exercise WorkbookRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (3)

- FreeCAD | Step by Step: Learn how to easily create 3D objects, assemblies, and technical drawingsFrom EverandFreeCAD | Step by Step: Learn how to easily create 3D objects, assemblies, and technical drawingsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Certified Solidworks Professional Advanced Weldments Exam PreparationFrom EverandCertified Solidworks Professional Advanced Weldments Exam PreparationRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- CATIA V5-6R2015 Basics - Part I : Getting Started and Sketcher WorkbenchFrom EverandCATIA V5-6R2015 Basics - Part I : Getting Started and Sketcher WorkbenchRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (10)

- SketchUp Success for Woodworkers: Four Simple Rules to Create 3D Drawings Quickly and AccuratelyFrom EverandSketchUp Success for Woodworkers: Four Simple Rules to Create 3D Drawings Quickly and AccuratelyRating: 1.5 out of 5 stars1.5/5 (2)

- Design Research Through Practice: From the Lab, Field, and ShowroomFrom EverandDesign Research Through Practice: From the Lab, Field, and ShowroomRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (7)

- From Vision to Version - Step by step guide for crafting and aligning your product vision, strategy and roadmap: Strategy Framework for Digital Product Management RockstarsFrom EverandFrom Vision to Version - Step by step guide for crafting and aligning your product vision, strategy and roadmap: Strategy Framework for Digital Product Management RockstarsNo ratings yet

- Fusion 360 | Step by Step: CAD Design, FEM Simulation & CAM for Beginners.From EverandFusion 360 | Step by Step: CAD Design, FEM Simulation & CAM for Beginners.No ratings yet

- FreeCAD | Design Projects: Design advanced CAD models step by stepFrom EverandFreeCAD | Design Projects: Design advanced CAD models step by stepRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Certified Solidworks Professional Advanced Surface Modeling Exam PreparationFrom EverandCertified Solidworks Professional Advanced Surface Modeling Exam PreparationRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Autodesk Fusion 360: A Power Guide for Beginners and Intermediate Users (3rd Edition)From EverandAutodesk Fusion 360: A Power Guide for Beginners and Intermediate Users (3rd Edition)Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Contactless Vital Signs MonitoringFrom EverandContactless Vital Signs MonitoringWenjin WangNo ratings yet