Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Giant Invasive Spinal Schwannomas: Definition and Surgical Management

Uploaded by

Ingrid AykeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Giant Invasive Spinal Schwannomas: Definition and Surgical Management

Uploaded by

Ingrid AykeCopyright:

Available Formats

J Neurosurg (Spine 2) 94:210–215, 2001

Giant invasive spinal schwannomas: definition

and surgical management

K. SRIDHAR, D.N.B. (NEUROSURG), RAVI RAMAMURTHI, M.S, F.R.C.S.ED. (SN),

M. C. VASUDEVAN, M.D., D.N.B. (NEUROSURG), AND B. RAMAMURTHI, M.S., F.R.C.S. ED.

Dr. A. Lakshmipathi Neurosurgical Centre, V.H.S. Medical Centre, Madras, India

Object. Confusion exists regarding the term giant spinal schwannoma. There are a variety of nerve sheath tumors that,

because of their size and extent, justify the label “giant schwannoma.” The authors propose a classification system for

spinal schwannomas as a means to define these giant lesions. The classification is confined to tumors that are essentially

intraspinal, with or without extraspinal components. Lesions that erode the vertebral bodies (VBs) and extend posteriorly

and laterally into the myofascial planes are classified as giant “invasive” spinal schwannomas.

Methods. The records of patients with giant invasive spinal schwannoma were analyzed. The radiological features, oper-

ative approaches, and intraoperative findings were noted.

Ten patients with giant invasive tumors were surgically treated over the last 8 years. Six patients were male. Erosion of

the posterior surface of the VBs was the diagnostic finding demonstrated on plain x-ray films. Magnetic resonance imag-

ing delineated the extent of the tumors and helped in preoperative planning. Radical excision of the tumors in multiple

stages was possible in eight of the 10 patients. Dural reconstruction was required in four patients. All patients required

fusion, and an additional stabilization procedure was undertaken in three patients.

Conclusions. The authors conclude that giant invasive schwannomas are uncommon lesions and propose a new classi-

fication system. Because of their locally “invasive” nature and extension in all directions, careful preoperative planning of

the surgical approach is very important. Although radical excision is possible and promises good results, recurrences may

occur and multiple surgical procedures may be required.

KEY WORDS • giant schwannoma • spine • surgical approach • reconstructive surgery •

classification system

PINAL schwannomas comprise approximately 25% of were analyzed retrospectively. The lesions were diag-

S all spinal tumors.2,5 They are most commonly seen in

the thoracic region and are then most commonly

found, with almost equal frequency, in the cervical and the

nosed by radiography, myelography, and/or MR imaging.

Classification of Spinal Schwannomas

lumbar regions. Until this report, no attempt had been made Based on the radiological findings, the authors have de-

to classify these lesions on the basis of their location and vised a classification system of spinal schwannomas (Table

extent. This has resulted in confusion in the use of the term 1 and Fig. 1). Giant spinal schwannomas are defined as

giant spinal schwannoma. By convention, the term refers those that extend over more than two vertebral levels (Type

only to lumbosacral and sacral tumors eroding the VBs and II), those that have an extraspinal extension of more than

extending into the paraspinal tissues. There are, however, 2.5 cm (giant dumbbell Type IVb), and those lesions that

other categories of tumors, that, due to their size and extent, erode the VBs and extend posteriorly and laterally into the

justify the designator giant schwannoma. The authors myofascial planes (giant invasive tumors, Type V). In the

propose a classification system of spinal schwannomas, in present study we focus on patients with the giant invasive,

which a giant tumor is defined and discuss the surgical man- or Type V, spinal schwannomas.

agement of patients with giant invasive spinal schwannomas.

Results

Clinical Material and Methods Ten patients underwent resection of their giant invasive

The case records of patients with spinal schwannomas schwannomas in the last 8 years (Table 2). They formed

surgically treated at our center between 1990 and 1999 10.9% of the cases of spinal neuromas surgically treated at

our center during the same period. Six of the 10 patients

were male. The youngest patient was 13 years of age and

Abbreviations used in this paper: MR = magnetic resonance; the oldest was 60 years of age (mean age 33.8 years). Only

VB = vertebral body. one of the patients had neurofibromatosis.

210 J. Neurosurg: Spine / Volume 94 / April, 2001

Giant invasive spinal schwannomas

TABLE 1

Classification of benign nerve sheath tumors

Classification

Type I intraspinal tumor, ⬍ 2 vertebral segments in length; a:

intradural; b: extradural.

Type II intraspinal tumor ⬎ 2 vertebral segments in length

(giant tumor)

Type III intraspinal tumor w/ extension into nerve root foramen

Type IV intraspinal tumor w/ extraspinal extension (dumbbell

tumors); a: extraspinal component ⬍ 2.5 cm;

b: extraspinal component ⬎ 2.5 cm (giant tumor)

Type V tumor w/ erosion into the VBs (giant invasive tumor),

lat & posterior extentions into myofascial planes

Findings on plain radiographs included a widened inter-

pedicular distance, erosion of the pedicle, enlargement of

the intervertebral foramen, and erosion of the posterior

surface of the VBs to a variable extent. The latter finding

was diagnostic of a giant invasive schwannoma. In two

patients a total block of the contrast column demonstrat-

ed on myelography was the definitive indicator of giant

schwannoma. On MR imaging the lesions appeared isoin-

tense or of varying intensity on T1-weighted images, and

the entire extent of the lesion, including the extraspinal

extensions and erosion of the VBs, was delineated.

Five of the lesions were located in the lumbar region,

two each in the thoracic and lumbosacral regions, and one

in the cervical region. Three or more operations were per-

formed in three patients, two in four patients, and one in

three patients.

Radical microscopic excision of the tumor was achieved

in eight patients, and dural reconstruction was necessary in

four patients. Fusion in which we used autologous bone

was performed in all patients. Three patients required an

additional stabilization procedure, as it was believed that FIG. 1. Diagrammatic representation of the proposed classifica-

tion of spinal schwannomas Types I to V. Type II (not shown) is

the spine was unstable. Bed rest for 3 months was ordered an intraspinal schwannoma extending for more than two vertebral

for one patient after which mobilization was allowed after segments. See Table 1 for definitions.

application of an external brace. One patient developed a

postoperative cerebrospinal fluid leak through the wound,

which subsided following repeated lumbar punctures. Fol- extradural schwannoma was accomplished. She regained

low-up periods ranged from 6 months to 4 years (mean 20 normal power and sensation within 8 months of surgery.

months). One patient with a lumbar tumor developed an At the age of 19 years she was admitted with a progres-

asymptomatic recurrence after 3 years and has been ad- sively increasing swelling in the neck. The lesion was

vised to undergo repeated surgery. approached anterolaterally, and a near-total excision of the

extraspinal schwannoma was achieved. A remnant of the

Illustrative Cases tumor was left at the region of the nerve root foramen.

Two patients who presented with problems requiring Examination. Plain radiography performed at the present

different approaches and management are described in admission demonstrated the C3–7 laminectomy, as well as

detail. a swan-neck deformity of the cervical spine with localized

porosis of the C-6 VB (Fig. 2 upper left). Magnetic reso-

Case 5 nance imaging of the cervical spine revealed a lobulated

lesion isointense in relation to the spinal cord on T1-weight-

This 25-year-old woman presented with a 5-month his- ed images and of a mixed intensity on T2-weighted images,

tory of progressive quadriparesis. extending from the lower border of the C-4 VB to the mid-

History. She had undergone two previous surgeries— dle of the C-7 VB. The lesion had eroded the C-6 VB and

one at age 16 years and one at age 19 years—for similar was extending through the left intervertebral foramen into

complaints. A myelogram obtained prior to the first oper- the neck with a large extraspinal component. The swan-

ation had demonstrated a total block at the lower border of neck deformity was causing pressure on the cord contralat-

the C-6 VB. A C3–7 laminectomy had been performed, eral to the upper border of C-4, at a level where there was

and radical excision of the intraspinal portion of an intra/ no tumor (Fig. 2 upper right and lower left).

J. Neurosurg: Spine / Volume 94 / April, 2001 211

K. Sridhar, et al.

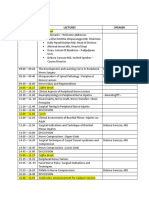

TABLE 2 (Fig. 3 center). The lesion extended through the laminec-

Characteristics of patients with a giant tomy up to the subcutaneous plane. A pseudomeningo-

spinal neurofibroma/schwannoma coele was observed posterior to the lesion.

Case Age (yrs), No. of Stabilization

Operation. The tumor was exposed via a posterolateral

No. Sex Region Ops Required approach on the left side where it was exiting from the

spinal canal. In addition, the facet joint at that level was

1 55, M lumbar 3 yes also removed. The dura was deficient over most of the

2 25, M lumbosacral 5 no lesion, and the tumor was in direct contact with the mus-

3 55, M thoracic 2 no

4 60, M lumbar 2 yes cles. Normal dura was exposed at the superior and inferi-

5 25, F cervical 4 yes or ends of the lesion as well as the superior and inferior

6 15, F lumbar 2 no poles of the tumor. Using the operating microscope, the

7 30, F thoracic 1 no tumor was debulked and space was created to dissect the

8 19, M lumbar 1 no lesion radically. It was found that the cauda equina was

9* 40, F lumbosacral 2 no pushed posteriorly and to the right by the lesion. There

10 13, M lumbar 1 no

was no difficulty in dissecting the tumor from the nerve

* This patient had neurofibromatosis. roots, and the tumor was excised radically (Fig. 3 right).

The tumor had eroded the VBs up to the anterior vertebral

margin, leaving behind a thin shell of bone and intact

Operation. A posterior approach to the tumor was un- intervertebral discs. Autologous bone chips were packed

dertaken as the first step. The previous laminectomy wound into the defect in the VBs. The edges of the normal dura

was reopened only on the left side where the tumor was were identified, and using a fascia lata graft, reconstruc-

exiting from the spinal canal. The bone removal was ex- tion of the dural tube was performed.

tended laterally to include the facet joints at C-5 and C-6 to Follow-Up Course. The patient’s neurological condition

facilitate removal of the extraspinal part of the tumor. improved in the postoperative period, and by the end of 2

Radical excision of the intra- and extraspinal portions of weeks normal power and lower-limb sensation and nor-

the tumor was performed, leaving only tags of lesion in the mal bladder function had returned. The patient was mobi-

eroded C-6 VB. A rib graft was used for fusion across the lized after 3 months, and she wore a lumbar brace. As of

operated levels. The patient was placed in traction postop- the 18-month follow up, she was mobile and experiencing

eratively for 4 days, after which the anterior approach was a minimal residual neurological deficit.

used, and a three-level corpectomy (C4–6) was performed

to correct the swan-neck deformity and to remove the tumor Discussion

remnants in the C-6 VB. An anterior C3–7 plate was placed Spinal nerve sheath tumors are most often single, small,

to stabilize the spine (Fig. 2 lower right). benign lesions that are relatively simple to remove and are

Follow-Up Course. The patient made excellent progress associated with a good postoperative result. Giant schwan-

in the postoperative period and was mobilized wearing a nomas are uncommon. The majority of giant spinal

cervical collar on the 3rd postoperative day. At the last fol- schwannomas are dumbbell shaped, which poses difficulty

low-up visit, 30 months after surgery, the patient was mainly in the radical removal of the extraspinal part of the

asymptomatic and neurologically normal. An x-ray film lesion. Various approaches have been conducted to help

demonstrated good fusion and implant position. remove these tumors totally.3,4,6

Giant invasive (Type V) schwannomas differ from the

Case 6 other giant schwannomas in that they erode the posterior

surface of the VBs, infiltrate through the posterior dura,

History. This 15-year-old girl had undergone surgery at

and invade the myofascial planes while still remaining his-

another center 1 year prior to presentation to us for back tologically benign. They are reported most often as case

pain, symptoms and signs of a conus medullaris–cauda reports, and in many large series of spinal schwannomas

equina lesion, and urinary retention. The lesion was a the authors make no mention of these lesions. Rao8 and

giant schwannoma of the lumbar spine. An L2–5 laminec- Levy, et al.,5 while reporting on 80 and 66 spinal schwan-

tomy had been performed, but the surgery was abandoned nomas, respectively, do not refer to these giant tumors.

following decompression of the tumor because the sur- Giant invasive tumors have been described almost exclu-

geon had believed that the lesion engulfed the nerve roots. sively in the lumbosacral spine and as intrasacral lesions.1,2,7

Presentation. The patient presented to us with an in- There have been no reports in the literature of a giant inva-

creasing lower-limb weakness and had received an in- sive nerve sheath tumor in the thoracic or cervical spine.

dwelling catheter. Giant invasive (Type V) schwannomas make surgery

Examination. Plain radiography of the lumbosacral difficult because of their growth in all directions. They

spine demonstrated the L2–5 laminectomy, posterior scal- extend 1) commonly over more than three vertebral levels;

loping of the L-3 and L-4 VBs of greater than 60% of the 2) anterolaterally into the extraspinal space via the fora-

body, and a scoliotic curve of the lumbar spine. Magnetic men, which they erode and widen; 3) posteriorly, thinning

resonance imaging demonstrated the multilobulated lesion and attenuating the dura and the posterior elements and,

extending from the upper border of the L-2 VB to the occasionally, extending into the posterior myofascial

lower border of L-5 (Fig. 3 left). The tumor was shown on planes; and 4) anteriorly, eroding the VBs to varying ex-

MR imaging to be eroding the L-3 and L-4 VBs and tents. These extensions cause problems for the surgeon in

extending to the extraspinal tissues on the left side only terms of approach, resectability, and stability of the spine.

212 J. Neurosurg: Spine / Volume 94 / April, 2001

Giant invasive spinal schwannomas

FIG. 2. Case 5. Imaging studies. Upper Left: Lateral x-ray film of the cervical spine demonstrating evidence of a pre-

vious laminectomy, a kyphotic deformity of the spine, and a localized porosis of the C-6 VB. Upper Right: Sagittal T1-

weighted MR image revealing an intraspinal tumor opposite the C-5 and C-6 VBs and extending anteriorly into the C-6

VB. The kyphotic deformity is causing spinal cord compression opposite the C-4 VB. Lower Left: Axial T2-weighted

MR image demonstrating the hyperintense tumor extending into and eroding the C-6 VB and extending extraspinally

through the left intervertebral foramen. Lower Right: Postoperative lateral x-ray film obtained following radical excision

of the tumor via both the posterior and anterior approaches. Correction of the kyphotic deformity was achieved as well as

total excision of the tumor with a median corpectomy from C-3 to C-6. An anterior plate was placed from C-2 to C-7.

Approach and Resectability reveal clearly the bone destruction and are required to

evaluate the stability of the spine.

Magnetic resonance imaging has made the preoperative Radical excision is difficult because these tumors lack a

planning of giant tumors easier than when myelography capsule that would help in dissecting them from the sur-

was the most commonly used neurodiagnostic tool. The rounding structures. It has been the observation of some

entire extent of the lesion is seen in all three planes, and authors, however, that these tumors often engulf the nerve

the relationship of the tumor to the neural elements, vas- roots of the cauda equina.2

cular structures, and other organs is clearly delineated. We have found that the relationship between the tumor

Plain radiographs and/or computerized tomography scans and the neural structures is constant. Depending on the

J. Neurosurg: Spine / Volume 94 / April, 2001 213

K. Sridhar, et al.

FIG. 3. Case 6. Magnetic resonance imaging studies. Left: Sagittal T1-weighted image demonstrating a mixed-inten-

sity lesion occupying the entire spinal canal from L-2 to L-5 and eroding and extending into the L-3 and L-4 VBs.

Center: Axial T2-weighted image demonstrating the tumor extending from the spinal canal into the VB, as well as later-

al extraspinal extension though the left intervertebral foramen, and posteriorly into the myofascial planes. The tumor is

capped posteriorly by a small pseudomeningocele related to previous surgery. Right: Axial T2-weighted image reveal-

ing total excision of the lesion. There is a meningocele extending laterally through the foramen. The reconstructed dura

is seen as a thin line.

side of origin of the tumor, the cord/nerve roots are pushed ally. Occasionally, the paraspinal muscles may have to be

and/or splayed to the opposite direction. On MR imaging divided to reach the far end of the extraspinal lesion. It is

it is seen that the tumors extend laterally most often on- possible to excise even large extraspinal extensions when

ly on one side and that the cord and/or cauda equina is using a high-magnification operating microscope and con-

pushed to the opposite side. This relationship is more stantly tipping the operating table.

clearly observed on the axial cuts obtained at either pole However, even with all these maneuvers, because of the

of the lesion. large size, extensive nature, and invasiveness of these tu-

It is, therefore, possible to perform a radical excision mors, it may not be possible to be certain at surgery that

of the tumor without causing neurological damage. By the tumor has been totally removed. The surgeon, there-

approaching the lesion in the midline, the surgeon may fore, must be aware of the prospect of having to reoperate

encounter the splayed nerve roots first and it may appear a number of times.

as though the nerves are engulfed by the lesion. Using a

posterolateral approach on the side of the tumor, initial Reconstruction and Stabilization

debulking can be performed to reduce the size, create It is important to plan for reconstruction once tumor

more space, and then allow the tumor to be separated from removal has been achieved. Deficient dura has to be

the neural elements. We have been able to separate the repaired using fascia lata if necessary. Erosion of the VB

tumor from the cord and/or nerve roots without any diffi- coupled with removal of the posterior elements with the

culty when using this approach. facet joint at more than one level is likely to leave the

Dissecting the tumors from the surrounding soft tissue spine unstable. Because the VB will slowly reconstitute

may be difficult when the tumors do not have a firm cap- itself, some surgeons have preferred not to fuse or stabi-

sule and are vascular. The anatomy of the region is con- lize the spine.7 However, if the lesion is in the cervical or

fusing when an essentially intradural tumor is seen at the upper-lumbar spine, early mobilization may be hazardous

muscle plane without the dural layer to delineate it. In if the spinal column has not been stabilized. Erosion of

such cases it is always preferable to take the exposure to more than 25% of the VB, in our opinion, requires some

the normal dura above and below both poles of the tumor form of reconstructive procedure. The use of implants,

and to start the dissection there so that the anatomy of the however, is not free of problems, the most important of

lesion is understood before the excision is begun. them being the difficulty of imaging studies during the

The tumor may erode into the VBs and may even pre- follow-up period. The surgeon, therefore, has to decide on

sent as a presacral or retroperitoneal mass.1,2,7,9–11 The tumor the use of hardware depending on whether the tumor re-

should be followed into the bone and removed. Extraspinal moval has been radical or not.

extensions of these tumors are usually multilobulated. Al- Results of radical excision of these large tumors have

though there is no firm capsule, the surrounding tissues of- been encouraging, and most patients do well. Recurrences

ten form a pseudocapsule around the lesion. The bone can be managed with repeat surgeries, and at each attempt

removal should be extended well lateral into the facet joint an aggressive effort should be made to excise the lesion

and lateral cuts made in the dura to follow the lesion later- radically.

214 J. Neurosurg: Spine / Volume 94 / April, 2001

Giant invasive spinal schwannomas

Conclusions 5. Levy WJ, Latchaw J, Hahn JF, et al: Spinal neurofibromas: a re-

port of 66 cases and a comparison with meningiomas. Neu-

Giant invasive spinal schwannomas are uncommon le- rosurgery 18:331–334, 1986

sions distinct from other giant spinal schwannomas. Be- 6. Lot G, George B: Cervical neuromas with extradural compo-

cause of their locally invasive nature and extensions in all nents: surgical management in a series of 57 patients. Neuro-

directions, careful preoperative planning of the surgical surgery 41:813–820, 1997

approach is very important. Although radical excision of 7. Piera JB, Durand J, Pannier S, et al: [10 cases of giant lumbo-

these extensive lesions is possible with good results, they sacral neurinoma.] Ann Med Interne (Paris) 126:316–330,1975

have a tendency to recur, necessitating repeated surgeries. (Fr)

8. Rao SB: Spinal neurinoma. A study of 80 operated cases. Neu-

rol India 23:1–12, 1975

Acknowledgment 9. Rengachary S, O’Boynick P, Batnitzky S, et al: Giant intrasa-

The authors thank Mr. Srinivasan for his help in preparing the cral Schwannoma: case report. Neurosurgery 9:573–577,

figures and illustrations. 1981

10. Turk PS, Peters N, Libbey NP, et al: Diagnosis and manage-

ment of giant intrasacral schwannoma. Cancer 70:2650–2657,

References 1992

1. Abernathey CD, Onofrio BM, Scheithauer B, et al: Surgical 11. Wu WQ: Management of two giant neurilemomas of the cauda

management of giant sacral schwannomas. J Neurosurgery equina. South Med J 73:386–388, 1980

65:286–295, 1986

2. Bhatia S, Khosla A, Dhir R, et al: Giant lumbosacral nerve

sheath tumors. Surg Neurol 37:118–122, 1992

3. Hakuba A, Komiyama M, Tsujimoto T, et al: Transuncodiscal Manuscript received May 8, 2000.

approach to dumbbell tumors of the cervical spinal canal. J Accepted in final form October 31, 2000.

Neurosurg 61:1100–1106, 1984 Address reprint requests to: K. Sridhar, D.N.B. (Neurosurg.), Dr.

4. McCormick PC: Surgical management of dumbbell tumors of A. Lakshmipathi Neurosurgical Centre, V.H.S. Medical Centre,

the cervical spine. Neurosurgery 38:294–300, 1996 Madras 600 113, India. email: ksree@md2.vsnl.net.in.

J. Neurosurg: Spine / Volume 94 / April, 2001 215

You might also like

- Vezina 2009Document5 pagesVezina 2009Ingrid AykeNo ratings yet

- Feng 2008Document3 pagesFeng 2008Ingrid AykeNo ratings yet

- Natural History of Chronic Subdural Haematoma: K.-S.LEEDocument8 pagesNatural History of Chronic Subdural Haematoma: K.-S.LEEAngelSosaNo ratings yet

- Vezina 2009Document5 pagesVezina 2009Ingrid AykeNo ratings yet

- Feng 2008Document3 pagesFeng 2008Ingrid AykeNo ratings yet

- Natural History of Chronic Subdural Haematoma: K.-S.LEEDocument8 pagesNatural History of Chronic Subdural Haematoma: K.-S.LEEAngelSosaNo ratings yet

- Cerebral Infarction Following Traumatic Carotid Cavernous Fistula in Adolescent Male A Case ReportDocument5 pagesCerebral Infarction Following Traumatic Carotid Cavernous Fistula in Adolescent Male A Case ReportIngrid AykeNo ratings yet

- Algattas 2020Document13 pagesAlgattas 2020Ingrid AykeNo ratings yet

- Giant Invasive Spinal Schwannomas: Definition and Surgical ManagementDocument6 pagesGiant Invasive Spinal Schwannomas: Definition and Surgical ManagementIngrid AykeNo ratings yet

- Algattas 2020Document13 pagesAlgattas 2020Ingrid AykeNo ratings yet

- Asha 2020Document8 pagesAsha 2020Ingrid AykeNo ratings yet

- Virtual Memorial James T. Goodrich FB-1Document1 pageVirtual Memorial James T. Goodrich FB-1Ingrid AykeNo ratings yet

- Asha 2020Document8 pagesAsha 2020Ingrid AykeNo ratings yet

- Ijss Oct Oa27 - 2018 PDFDocument6 pagesIjss Oct Oa27 - 2018 PDFIngrid AykeNo ratings yet

- 5 6149941315837624367 PDFDocument4 pages5 6149941315837624367 PDFIde Bagoes InsaniNo ratings yet

- Strokeaha 110 591008 PDFDocument4 pagesStrokeaha 110 591008 PDFIngrid AykeNo ratings yet

- Cerebral Infarction Following Traumatic Carotid Cavernous Fistula in Adolescent Male A Case ReportDocument5 pagesCerebral Infarction Following Traumatic Carotid Cavernous Fistula in Adolescent Male A Case ReportIngrid AykeNo ratings yet

- Neurosurgical Review 2020 PDFDocument538 pagesNeurosurgical Review 2020 PDFIngrid AykeNo ratings yet

- Neurosurgical Review 2020 PDFDocument10 pagesNeurosurgical Review 2020 PDFIngrid AykeNo ratings yet

- GCS PDFDocument1 pageGCS PDFFrincia100% (1)

- ACNSDocument1 pageACNSIngrid AykeNo ratings yet

- Lesions of The Corpus Callosum: ResidentsDocument16 pagesLesions of The Corpus Callosum: ResidentsIngrid AykeNo ratings yet

- Peripheral Nerve Schedule PDFDocument3 pagesPeripheral Nerve Schedule PDFIngrid AykeNo ratings yet

- EU - WEST - 1 Prod s3 Ucmdata Evise C - O6293533 - 3249515Document16 pagesEU - WEST - 1 Prod s3 Ucmdata Evise C - O6293533 - 3249515Ingrid AykeNo ratings yet

- Craniometrics and Ventricular Access PDFDocument9 pagesCraniometrics and Ventricular Access PDFIngrid AykeNo ratings yet

- COVID 19 Pediatric Neurosurgery GuidelinesDocument1 pageCOVID 19 Pediatric Neurosurgery GuidelinesIngrid AykeNo ratings yet

- Furoshiki: Back in The Age ofDocument2 pagesFuroshiki: Back in The Age ofIngrid AykeNo ratings yet

- Ijss Oct Oa27 - 2018Document6 pagesIjss Oct Oa27 - 2018Ingrid AykeNo ratings yet

- Management of Multiply Injured Pediatric Trauma Patients in The Emergency Department Trauma CME Calculators PDFDocument5 pagesManagement of Multiply Injured Pediatric Trauma Patients in The Emergency Department Trauma CME Calculators PDFIngrid AykeNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Meningitis Ein 3Document42 pagesMeningitis Ein 3Rifqi FuadiNo ratings yet

- Essentials of Athletic Injury Management 10th EditionDocument61 pagesEssentials of Athletic Injury Management 10th Editionalla.adams464100% (46)

- Abdominal Exercises: A Review Study For Training PrescriptionDocument4 pagesAbdominal Exercises: A Review Study For Training PrescriptioninventionjournalsNo ratings yet

- F1582 1479757-1Document3 pagesF1582 1479757-1Thaweekarn ChangthongNo ratings yet

- Medical Surgical Nursing PinoyDocument67 pagesMedical Surgical Nursing Pinoyalfred31191% (23)

- Phylogeny Poison Dart Frog 2005 Grant DissertationDocument549 pagesPhylogeny Poison Dart Frog 2005 Grant DissertationLuis Javier Mendoza Estrada100% (1)

- Accordion Sign-Appearance (C. Difficile)Document41 pagesAccordion Sign-Appearance (C. Difficile)Andra HijratulNo ratings yet

- Comparative Animal AnatomyDocument324 pagesComparative Animal AnatomyMohammed Anuz80% (5)

- EmbryologyDocument26 pagesEmbryologyMeer BabanNo ratings yet

- Principles and Components of Spinal OrthosesDocument33 pagesPrinciples and Components of Spinal OrthosesZ .TNo ratings yet

- ANPH Midterm NotesDocument44 pagesANPH Midterm NotesClaudine Jo B. TalabocNo ratings yet

- Orthopaedic Cast and BracesDocument21 pagesOrthopaedic Cast and BracesAlvin L. RozierNo ratings yet

- S1.2 Spinal Trauma, Orthopaedic Management - DR Ahmad RamdanDocument47 pagesS1.2 Spinal Trauma, Orthopaedic Management - DR Ahmad RamdanParadita MulyaNo ratings yet

- Hartman 1966 Polychaeta Sedentaria Antarctica LiteDocument166 pagesHartman 1966 Polychaeta Sedentaria Antarctica LiteValentina Sandoval ParraNo ratings yet

- Optimal Pillow Conditions For High Quality SleepDocument6 pagesOptimal Pillow Conditions For High Quality SleepFebwin VillaceranNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2, Unit 2, Human Anatomy and Physiology 1, B Pharmacy 1st Sem, Carewell PharmaDocument17 pagesChapter 2, Unit 2, Human Anatomy and Physiology 1, B Pharmacy 1st Sem, Carewell Pharmatambreen18No ratings yet

- Postural CorrectionDocument234 pagesPostural CorrectionSerge Baumann96% (52)

- 9 Palace QigongDocument19 pages9 Palace QigongTest4D100% (1)

- Synopsis Neuroscience Part1Document38 pagesSynopsis Neuroscience Part1Jong PetchinNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Problems: Article 3/3 Problems Introductory ProblemsDocument55 pagesChapter 3 Problems: Article 3/3 Problems Introductory ProblemsM100% (1)

- Football Injury: Literature: A ReviewDocument11 pagesFootball Injury: Literature: A Reviewaldo123456789No ratings yet

- Spine TraumaDocument96 pagesSpine TraumaSherlockHolmesSezNo ratings yet

- Skeletal and Vertebral Age - A Literature ReviewDocument17 pagesSkeletal and Vertebral Age - A Literature ReviewSergio Polizio Terçarolli100% (3)

- Animal Science 121 Principles To Animal Science Compiled by Dr. Erwin L. IcallaDocument19 pagesAnimal Science 121 Principles To Animal Science Compiled by Dr. Erwin L. IcallaJamielyne Rizza AtienzaNo ratings yet

- All About Skull PDFDocument28 pagesAll About Skull PDFJoel SeradNo ratings yet

- chap05.ppt-FLEXIBILITY AND LOW-BACK HEALTHDocument27 pageschap05.ppt-FLEXIBILITY AND LOW-BACK HEALTHJeremy Bio FangonNo ratings yet

- Skeleton of The SharkDocument12 pagesSkeleton of The SharkJoachimNo ratings yet

- Biomechanics Important QuestionsDocument11 pagesBiomechanics Important QuestionsHarshiya ChintuNo ratings yet

- Spine Flex v3 Plus Massage Bed User ManualDocument41 pagesSpine Flex v3 Plus Massage Bed User ManualAbhayDagaNo ratings yet