Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Association of Urbanicity With Psychosis in Low-And Middle-Income Countries

Uploaded by

奚浩然Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Association of Urbanicity With Psychosis in Low-And Middle-Income Countries

Uploaded by

奚浩然Copyright:

Available Formats

Research

JAMA Psychiatry | Original Investigation

Association of Urbanicity With Psychosis

in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

Jordan E. DeVylder, PhD; Ian Kelleher, MD, PhD; Monique Lalane, MSW; Hans Oh, PhD;

Bruce G. Link, PhD; Ai Koyanagi, MD, MSc, PhD

Invited Commentary

IMPORTANCE Urban residence is one of the most well-established risk factors for psychotic Supplemental content

disorder, but most evidence comes from a small group of high-income countries.

OBJECTIVE To determine whether urban living is associated with greater odds for psychosis in

low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS This international population-based study used

cross-sectional survey data collected as part of the World Health Organization (WHO) World

Health Survey from May 2, 2002, through December 31, 2004. Participants included

nationally representative general population probability samples of adults (ⱖ18 years)

residing in 42 LMICs (N = 215 682). Data were analyzed from November 20 through

December 5, 2017.

EXPOSURES Urban vs nonurban residence, determined by the WHO based on national data.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES Psychotic experiences, assessed using the WHO Composite

International Diagnostic Interview psychosis screen, and self-reported lifetime history of a

diagnosis of a psychotic disorder.

RESULTS Among the 215 682 participants (50.8% women and 49.2% men; mean [SD] age,

37.9 [15.7] years), urban residence was not associated with psychotic experiences (odds ratio

[OR], 0.99; 95% CI, 0.89-1.11) or psychotic disorder (OR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.76-1.06). Results of

all pooled analyses and meta-analyses of within-country effects approached a null effect,

with an overall OR of 0.97 (95% CI, 0.87-1.07), OR for low-income countries of 0.98 (95% CI,

0.82-1.15), and OR for middle-income countries of 0.96 (95% CI, 0.84-1.09) for psychotic

experiences and an overall OR of 0.92 (95% CI, 0.73-1.16), OR for low-income countries of

0.92 (95% CI, 0.66-1.27), and OR for middle-income countries of 0.92 (95% CI, 0.67-1.27) for

psychotic disorder.

Author Affiliations: Graduate School

of Social Service, Fordham University,

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE Our results provide evidence that urbanicity, a New York, New York (DeVylder,

well-established risk factor for psychosis, may not be associated with elevated odds for Lalane); Department of Psychiatry,

Royal College of Surgeons, Dublin,

psychosis in developing countries. This finding may provide better understanding of the Ireland (Kelleher); School of Social

mechanisms by which urban living may contribute to psychosis risk in high-income countries, Work, University of Southern

because urban-rural patterns of cannabis use, racial discrimination, and socioeconomic California, Los Angeles (Oh);

Department of Sociology, University

disparities may vary between developing and developed nations.

of California, Riverside (Link);

Department of Public Policy,

University of California, Riverside

(Link); Research and Development

Unit, Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu,

Universitat de Barcelona, Fundació

Sant Joan de Déu,

Sant Boi de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain

(Koyanagi); Instituto de Salud Carlos

III, Centro de Investigación Biomédica

en Red de Salud Mental, Madrid,

Spain (Koyanagi).

Corresponding Author: Jordan E.

DeVylder, PhD, Graduate School of

Social Service, Fordham University,

JAMA Psychiatry. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0577 113 W 60th St, New York, NY 10023

Published online May 16, 2018. (jdevylder@forhdam.edu).

(Reprinted) E1

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: by a University of Toledo Libraries User on 05/22/2018

Research Original Investigation Association of Urbanicity With Psychosis in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

U

rbanicity is among the most well-established environ-

mental risk factors for psychotic disorders, with nearly Key Points

8 decades of research reporting a positive association

Question Is urban living associated with elevated odds for

across various sampling approaches and definitions of urban psychotic experiences or psychotic disorder in low- and

exposure, time of exposure, onset of symptoms, and defini- middle-income countries?

tion of illness.1-3 Meta-analysis4 has shown that the risk of de-

Findings In this cross-sectional epidemiological study of 42

veloping schizophrenia is approximately 2.37 times greater in

countries and 215 682 participants, urban residence was not

urban compared with rural settings and is associated with the associated with increased odds of psychotic experiences or

level of density of the urban environment and population den- psychotic disorders.

sity in a dose-response fashion that suggests the possibility of

Meaning The association between urban living and psychosis,

a causal effect. Potential mechanisms that have been hypoth-

widely replicated in high-income countries, may not generalize to

esized include ethnic minority status, stress of urban living, low- and middle-income countries, where 80% of the world’s

greater urban prevalence of substance use, and toxic expo- population resides.

sures that may be related to city dwelling.5 Although these

mechanisms are plausible, studies have found that the asso-

ciation between urbanicity and psychosis is broadly robust to rationale are given in eTable 1 in the Supplement). A total of

adjustment for these factors.6,7 42 countries were included in the final sample of 215 682 re-

Despite these well-replicated findings, most studies of ur- spondents. According to the World Bank classification in 2003

banicity and psychosis have been conducted in high-income (at the time of the survey), these countries corresponded to

countries in Europe or North America or in Australia.4,6,8 The 17 low-income countries (86 437 respondents) and 25 middle-

association between urbanicity and psychosis is understud- income countries (129 245 respondents). Ethical boards at each

ied in low- and middle- income countries (LMICs), although study site (listed in eTable 2 in the Supplement) approved the

LMICs are home to greater than 80% of the world’s popula- study with written informed consent being obtained from all

tion. Some factors that characterize urban-rural differences in participants after the nature of the procedure has been fully

high-income countries may not generalize to many LMICs, explained. Secondary analyses of these publicly available de-

where urban living may indicate greater access to resources identified data were determined to be exempt from institu-

rather than greater exposure to social adversity.9,10 As such, tional ethical review (Office for Human Research Protections

the literature on urbanicity and psychosis has been less category 4 exemption), determined through consultation

consistent in LMICs, finding significant associations in some between us and the institutional review board of Fordham

countries (eg, Uganda11,12 and Nigeria13) but not others (eg, University.

Mozambique14,15 and India16-18).

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) World Health Sur- Variables

vey (WHS)19 presented a unique opportunity to examine the Exposure: Urban Residence

association between urbanicity and psychosis in LMICs in a Urban residence was defined as a dichotomous variable based

large sample (N = 215 682). Using data from 42 LMICs, we tested on the respondent’s place of residence at the time of the sur-

whether urban environments in these countries were associated vey. Each country defined the categories of rural and urban and

with elevated odds for (1) subthreshold psychotic experiences provided the definitions to the WHO to allow for stratified sam-

and (2) self-reported diagnoses of psychotic disorder. pling and analytic comparison between countries. Although

the specific criteria used by each country to define urban vs

rural areas were not publicly released, the estimates of urba-

nicity for each country are consistent with contemporaneous

Methods (2003) urbanicity data used by the World Bank that are based

World Health Survey on the United Nations world urbanization prospects report

The WHS was a cross-sectional survey conducted in 70 coun- (eTable 3 in the Supplement).20 Six countries varied notably

tries from May 2, 2002, through December 31, 2004. Survey (>10%) from World Bank estimates of urbanicity, but study re-

details are available from the WHO.19 All countries included sults were not meaningfully changed when these countries

in our analyses used multistage, random cluster sampling, were excluded from analyses. To further validate the WHS mea-

stratified by sex, age, and residential area (rural or urban). All sure of urbanicity, we examined whether WHS-defined ur-

adults 18 years or older with a valid home address were as- ban areas had higher rates of known transnational indicators

signed a nonzero chance of inclusion. Standard translation pro- of urban living (eg, percentage of jobs in agriculture, house-

cedures were followed to ensure comparability across coun- hold television ownership, and household electricity), con-

tries. Face-to-face and telephone interviews were conducted firming that households identified as urban in the WHS con-

by trained interviewers. Individual level response rates were formed to common validated characteristics of urban areas

greater than 82%. Poststratification corrections were made to (eTables 4 and 5 in the Supplement).21

sampling weights to adjust for nonresponse and the popula-

tion distribution reported by the United Nations Statistical Di- Outcomes: Psychotic Experiences and Psychotic Disorder

vision. Data from 69 countries were publicly available. Twenty- All participants were asked questions about psychotic symp-

seven countries were excluded from analysis (the list and toms that came from the WHO Composite International Diag-

E2 JAMA Psychiatry Published online May 16, 2018 (Reprinted) jamapsychiatry.com

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: by a University of Toledo Libraries User on 05/22/2018

Association of Urbanicity With Psychosis in Low- and Middle-Income Countries Original Investigation Research

nostic Interview (CIDI), version 3.0.22 The psychosis module duce biased estimates when used with complex study designs.30

of the CIDI has been reported to be highly consistent with The analytic approach of conducting meta-analyses with ran-

clinician ratings in a clinical sample.23 Specifically, respon- dom effects based on countrywise estimates has been used

dents were asked the following questions with answer in previous WHS publications.24,31 The percentage of missing

options of yes or no: During the last 12 months, have you values for each variable used in the analysis were 6.1% for psy-

experienced (1) a feeling something strange and unexplain- chotic disorder, 12.3% for psychotic experiences, 3.5% for age,

able was going on that other people would find hard to 3.5% for sex, and 0.7% for urban residence. Cases with miss-

believe? (delusional mood); (2) a feeling that people were ing values were excluded in our complete case analysis of the

too interested in you or there was a plot to harm you? (delu- data.

sions of reference and persecution); (3) a feeling that your The sample weighting and the complex study design were

thoughts were being directly interfered or controlled by taken into account in all analyses. Data on the clusters and

another person or your mind was being taken over by strata in addition to the sampling weight were provided in the

strange forces? (delusions of control); or (4) an experience of data set, and incorporation of these 3 elements with the Tay-

seeing visions or hearing voices that others could not see or lor linearization methods allowed for calculation of nation-

hear when you were not half asleep, dreaming, or under the ally representative estimates. Results from the logistic re-

influence of alcohol or drugs? (hallucinations). Individuals gression models are presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95%

who endorsed at least 1 of these 4 symptoms were consid- CIs. The level of statistical significance was set at P < .05. Based

ered to have psychotic experiences.24 on our a priori power analysis, we calculated a 99% chance

The secondary outcome of this study was a self- (1 − β≥0.99) of detecting small effects (OR, ≥1.06 for psy-

reported lifetime history of a psychotic disorder. Partici- chotic experiences and 1.20 for psychotic disorder) in our

pants were asked whether they had ever received a diagno- 2-tailed logistic regression analyses (α = .05). We did not ad-

sis of schizophrenia or psychotic disorder with yes and no just the P value for multiple comparisons to avoid type II er-

answer options. Hereafter, we refer to this condition as psy- rors. Thus, significant countrywise estimates should be inter-

chotic disorder for brevity. preted with caution because some may have occurred by

chance.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed from November 20 through December 5,

2017. The statistical analysis was accomplished in Stata soft-

ware (release 14.1; StataCorp, LP).25 A descriptive analysis was

Results

conducted using unweighted numbers and weighted propor- The analytical sample consisted of 215 682 individuals with a

tions. Countrywise age- and sex-adjusted prevalence esti- mean (SD) age of 37.9 (15.7) years (50.8% women and 49.2%

mates for psychotic experiences and psychotic disorder (over- men). Overall, 46.2% were urban residents, but this propor-

all and by urban residence) were calculated using the United tion was higher in middle-income countries than in low-

Nations population pyramids for the year 2010 as the stan- income countries (67.6% vs 28.7%). The prevalence of psy-

dard population.26 For analyses on psychotic experiences, in- chotic experiences was 13.0% (low-income countries, 10.2%;

dividuals with psychotic disorder (n = 1996) were excluded be- middle-income countries, 16.6%); of psychotic disorder, 0.9%

cause psychotic experiences, by definition, do not reach the (low-income countries, 1.0%; middle-income countries, 0.9%).

clinical threshold for a psychosis diagnosis. Countrywise mul- The countrywise age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of psy-

tivariable logistic regression models adjusted for age (continu- chotic experience and psychotic disorder (and by urban-rural

ous variable) and sex were constructed to assess the associa- residence) is shown in the Table. The countrywise associa-

tion between urban residence (exposure) and psychotic tions between urban residence and psychotic experiences by

experiences or psychotic disorder (outcomes). Separate logis- country income level estimated by multivariable logistic re-

tic regression models were used for each outcome, rather than gression are shown in Figure 1. At an individual country level,

multinomial regression, to avoid potentially inflating effect we found a significant positive association between urban resi-

sizes for respondents with psychotic disorder by excluding re- dence and psychotic experiences in Laos (OR, 1.59; 95%

spondents with psychotic experiences from the control group. CI, 1.09-2.33), Mali (OR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.09-2.12), Estonia (OR,

The estimates for each country were combined into a random- 2.11; 95% CI, 1.20-3.72), Mexico (OR, 1,26; 95% CI, 1.03-1.54),

effects meta-analysis. We calculated Higgins I2 statistics to and Morocco (OR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.13-2.17) and a significant nega-

assess the level of between-country heterogeneity that is not tive association between urban residence and psychotic

explained by sampling error. Heterogeneity of less than 40% experiences in Nepal (OR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.62-0.92), Vietnam

is conventionally regarded as negligible.27 (OR, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.07-0.98), Hungary (OR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.41-

Analyses using the overall sample and by country income 0.97), and South Africa (OR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.27-0.70). Over-

level were conducted. Exploratory analyses tested associa- all, no significant association of urban residence with psy-

tions between urbanicity and psychotic experiences sepa- chotic experiences was found in low-income countries (pooled

rately between younger adults (ages 18-29 years) and the re- OR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.86-1.23) and middle-income countries

mainder of the sample (ages ≥30 years), given the particular (pooled OR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.84-1.12). A moderate level of

significance of young adulthood in the etiology of psychosis.28,29 heterogeneity between countries was indicated (I2 = 61%; 95%

We did not use multilevel models because such analyses can pro- CI, 45%-72%). The pooled OR for the association between ur-

jamapsychiatry.com (Reprinted) JAMA Psychiatry Published online May 16, 2018 E3

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: by a University of Toledo Libraries User on 05/22/2018

Research Original Investigation Association of Urbanicity With Psychosis in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

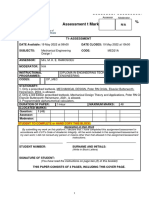

Table. Age- and Sex-Adjusted Prevalence of Psychotic Disorder and Psychotic Experience

Age- and Sex-Adjusted Weighted Prevalence, % (SE)a

Psychotic Disorder Psychotic Experience

Unweighted No.

Countries of Respondents Overall Urban Residence Rural Residence Overall Urban Residence Rural Residence

Low-income countries

Bangladesh 5942 0.7 (0.2) 1.0 (0.3) 0.7 (0.2) 13.1 (1.2) 12.6 (1.7) 13.2 (1.5)

Burkina Faso 4948 1.3 (0.3) 1.0 (0.5) 1.3 (0.3) 23.3 (1.9) 26.9 (2.3) 22.5 (2.3)

Chad 4870 3.1 (0.4) 3.4 (0.9) 3.0 (0.4) 16.3 (1.6) 18.7 (2.6) 15.4 (1.9)

Ethiopia 5089 1.5 (0.2) 2.3 (0.7) 1.3 (0.2) 16.6 (0.8) 14.8 (2.7) 16.9 (0.8)

Ghana 4165 0.7 (0.1) 0.9 (0.3) 0.5 (0.1) 4.9 (0.5) 4.1 (0.6) 5.5 (0.6)

Kenya 4640 0.8 (0.2) 0.9 (0.5) 0.7 (0.2) 17.9 (1.4) 11.9 (2.8) 19.9 (1.0)

Laos 4988 0.4 (0.1) 0.7 (0.3) 0.3 (0.1) 5.7 (0.5) 7.7 (1.1) 5.2 (0.5)

Malawi 5551 1.2 (0.2) 0.8 (0.5) 1.3 (0.2) 4.7 (0.6) 5.0 (1.2) 4.8 (0.6)

Mali 4886 2.2 (0.4) 1.2 (0.5) 2.7 (0.5) 14.1 (0.9) 17.3 (2.2) 12.5 (0.9)

Mauritania 3902 2.6 (0.5) 2.5 (0.7) 3.0 (0.7) 9.6 (1.2) 11.3 (1.6) 7.1 (1.9)

Myanmar 6045 0.3 (0.1) 0.4 (0.2) 0.3 (0.2) 2.6 (0.6) 2.0 (1.1) 2.9 (0.7)

Nepal 8820 2.6 (0.2) 1.9 (0.5) 2.7 (0.2) 45.1 (0.8) 39.1 (2.6) 46.2 (0.8)

Pakistan 6501 1.1 (0.2) 1.0 (0.3) 1.1 (0.2) 2.0 (0.3) 2.9 (0.7) 1.5 (0.3)

Senegal 3461 1.4 (0.3) 0.7 (0.2) 2.0 (0.6) 18.7 (1.4) 19.9 (1.9) 17.8 (2.0)

Vietnam 4174 0.1 (0.03) 0 (0) 0.1 (0.04) 0.7 (0.2) 0.3 (0.2) 0.8 (0.3)

Zambia 4165 0.6 (0.1) 0.9 (0.4) 0.6 (0.1) 10.6 (0.8) 9.3 (1.3) 11.4 (1.0)

Zimbabwe 4290 1.1 (0.2) 0.7 (0.4) 1.3 (0.3) 8.5 (0.8) 8.3 (1.2) 8.7 (1.1)

Middle-income

countries

Bosnia and 1031 0.1 (0.1) 0.1 (0.1) 0.1 (0.1) 1.8 (0.5) 2.4 (0.9) 1.2 (0.5)

Herzegovina

Brazil 5000 1.7 (0.2) 1.7 (0.2) 1.6 (0.5) 31.6 (0.9) 31.7 (1.0) 30.9 (2.6)

Croatia 993 2.0 (0.5) 1.7 (0.6) 2.5 (1.1) 7.3 (1.1) 6.6 (1.4) 9.2 (1.9)

Czech Republic 949 0.4 (0.2) 0.5 (0.3) 0.1 (0.1) 9.0 (1.5) 7.1 (1.3) 13.8 (3.6)

Dominican Republic 5027 1.0 (0.2) 0.7 (0.2) 1.4 (0.5) 21.5 (1.3) 21.3 (1.7) 22.1 (2.6)

Ecuador 5675 0.9 (0.2) 1.0 (0.3) 0.9 (0.3) 8.9 (1.0) 9.1 (1.2) 8.5 (1.7)

Estonia 1020 1.5 (0.5) 2.0 (0.6) 0.2 (0.2) 11.8 (1.2) 14 (1.7) 6.6 (1.6)

Georgia 2950 0.5 (0.2) 0.5 (0.3) 0.5 (0.2) 1.8 (0.5) 1.5 (0.7) 1.8 (0.5)

Hungary 1419 2.4 (0.5) 2.1 (0.7) 3.1 (0.7) 6.7 (0.7) 5.6 (0.9) 8.7 (1.2)

Kazakhstan 4499 0.5 (0.1) 0.3 (0.1) 0.8 (0.3) 3.0 (0.6) 1.9 (0.6) 4.5 (1.3)

Latvia 929 0.8 (0.4) 0.8 (0.5) 0.7 (0.7) 13.7 (1.7) 12.8 (2.1) 15.5 (2.9)

Malaysia 6145 0.2 (0.1) 0.2 (0.1) 0.1 (0.1) 7.1 (0.5) 6.6 (0.6) 7.8 (0.8)

Mauritius 3968 0.6 (0.1) 0.4 (0.1) 0.8 (0.2) 7.7 (1.0) 6.3 (1.4) 9.1 (1.5)

Mexico 38 746 0.4 (0.04) 0.4 (0.1) 0.3 (0.1) 8.7 (0.3) 9.1 (0.4) 7.5 (0.6)

Morocco 5000 0.7 (0.2) 0.7 (0.3) 0.5 (0.2) 17.6 (1.2) 19.6 (1.8) 14.5 (1.3)

Namibia 4379 3.0 (0.4) 3.3 (1.1) 3.0 (0.5) 10.9 (0.8) 12.2 (1.4) 10.1 (0.9)

Paraguay 5288 0.5 (0.1) 0.4 (0.1) 0.5 (0.2) 9.0 (0.5) 9.6 (0.8) 8.2 (0.6)

Philippines 10 083 0.4 (0.1) 0.3 (0.1) 0.6 (0.1) 8.9 (0.7) 8.8 (0.9) 9.1 (1.0)

Slovakia 2535 0.3 (0.1) 0.4 (0.2) 0 (0) 9.6 (1.7) 10.4 (1.5) 8.4 (3.3)

South Africa 2629 1.2 (0.3) 0.9 (0.3) 1.6 (0.5) 14.9 (1.6) 10.4 (1.4) 21.1 (3.2)

Sri Lanka 6805 0.6 (0.2) 0.8 (0.7) 0.6 (0.1) 2.2 (0.3) 3.3 (0.8) 1.9 (0.4)

Swaziland 3117 6.2 (0.9) 6.4 (1.2) 6.4 (1.1) 17.8 (1.3) 17.1 (2.0) 18.0 (1.5)

Tunisia 5202 1.9 (0.3) 1.7 (0.3) 2.2 (0.5) 14.7 (1.2) 13.2 (1.6) 17.4 (1.7)

Ukraine 2860 0.6 (0.1) 0.6 (0.2) 0.5 (0.3) 7.1 (0.9) 6.7 (1.0) 7.9 (1.9)

Uruguay 2996 0.7 (0.1) 0.8 (0.1) 0.6 (0.4) 5.5 (1.1) 5.6 (1.2) 4.2 (1.4)

a

All age- and sex-adjusted weighted estimates were calculated using the United Nations population pyramids for 2010.26

banicity and psychotic experiences for all LMICs was 0.99 (95% logistic regression analysis pooling all countries and adjust-

CI, 0.89-1.11). Associations between urbanicity and psychotic ing for age, sex, and country yielded a similar result of an over-

experiences were nonsignificant when examined separately all OR of 0.97 (95% CI, 0.87-1.07), OR for low-income coun-

between younger adults (aged 18-29 years) and those 30 years tries of 0.98 (95% CI, 0.82-1.15), and OR for middle-income

or older (eFigures 1 and 2 in the Supplement). Multivariable countries of 0.96 (95% CI, 0.84-1.09).

E4 JAMA Psychiatry Published online May 16, 2018 (Reprinted) jamapsychiatry.com

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: by a University of Toledo Libraries User on 05/22/2018

Association of Urbanicity With Psychosis in Low- and Middle-Income Countries Original Investigation Research

Figure 1. Countrywise Association Between Urban Residence (Exposure) and Psychotic Experience (Outcome)

by Country Income Level

A Low-income countries

No. of Favors No Psychotic Favors Psychotic Weight,

Country Respondents OR (95% CI) Experience Experience %

Bangladesh 5942 0.95 (0.63-1.42) 6.67

Burkina Faso 4948 1.40 (0.98-2.00) 7.30

Chad 4870 1.37 (0.87-2.16) 6.16

Ethiopia 5089 1.00 (0.64-1.57) 6.25

Ghana 4165 0.74 (0.49-1.12) 6.58

Kenya 4640 0.60 (0.34-1.04) 5.13

Laos 4988 1.59 (1.09-2.33) 7.01

Malawi 5551 0.80 (0.48-1.32) 5.65

Mali 4886 1.52 (1.09-2.12) 7.58

Mauritania 3902 1.71 (0.89-3.28) 4.30

Myanmar 6045 0.71 (0.21-2.47) 1.68

Nepal 8820 0.76 (0.62-0.92) 9.14

Pakistan 6501 1.89 (0.98-3.62) 4.29

Senegal 3461 1.16 (0.81-1.65) 7.33

Vietnam 4174 0.26 (0.07-0.98) 1.47

Zambia 4165 0.79 (0.56-1.11) 7.47

Zimbabwe 4290 0.89 (0.55-1.42) 5.99

Overall heterogeneity: 86 437 1.03 (0.86-1.23) 100.00

I 2 = 63.6%, P <.001

0.06 1.0 15.1

OR (95% CI)

B Middle-income countries

No. of Favors No Psychotic Favors Psychotic Weight,

Country Respondents OR (95% CI) Experience Experience %

Bosnia and Herzegovina 1031 1.70 (0.54-5.38) 1.26

Brazil 5000 1.08 (0.83-1.40) 6.24

Croatia 993 0.73 (0.38-1.39) 2.98

Czech Republic 949 0.48 (0.24-0.97) 2.64

Dominican Republic 5027 0.95 (0.64-1.42) 4.82

Ecuador 5675 1.11 (0.67-1.85) 3.89

Estonia 1020 2.11 (1.20-3.72) 3.47

Georgia 2950 0.76 (0.24-2.42) 1.24

Hungary 1419 0.63 (0.41-0.97) 4.57

Kazakhstan 4499 0.42 (0.17-1.03) 1.89

Latvia 929 0.77 (0.44-1.37) 3.44

Malaysia 6145 0.86 (0.64-1.14) 5.97

Mauritius 3968 0.68 (0.37-1.26) 3.16

Mexico 38 746 1.26 (1.03-1.54) 6.83

Morocco 5000 1.56 (1.13-2.17) 5.57

Namibia 4379 1.25 (0.91-1.72) 5.64

Paraguay 5288 1.24 (0.96-1.59) 6.34

Philippines 10 083 0.95 (0.68-1.34) 5.46

Slovakia 2535 1.21 (0.45-3.25) 1.61

South Africa 2629 0.43 (0.27-0.70) 4.11

Sri Lanka 6805 1.77 (0.91-3.43) 2.87

Swaziland 3117 0.90 (0.62-1.31) 5.11

Tunisia 5202 0.75 (0.53-1.07) 5.29

Ukraine 2860 0.86 (0.48-1.53) 3.36

Associations are estimated with

Uruguay 2996 1.28 (0.58-2.82) 2.26

multivariable logistic regression

Overall heterogeneity: 129 245 0.97 (0.84-1.12) 100.00

adjusting for age and sex. The overall

I 2 = 59.8%, P <.001

estimate and weights were calculated

0.06 1.0 15.1 by random-effects meta-analysis. OR

OR (95% CI) indicates odds ratio; diamond,

heterogeneity.

The countrywise associations between urban residence residents had significantly higher odds for psychotic disorder

and psychotic disorder by country income level estimated by only in Estonia (OR, 12.17; 95% CI, 1.53-97.03), whereas sig-

multivariable logistic regression are shown in Figure 2. Urban nificantly lower odds was observed in Mali (OR, 0.42; 95% CI,

jamapsychiatry.com (Reprinted) JAMA Psychiatry Published online May 16, 2018 E5

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: by a University of Toledo Libraries User on 05/22/2018

Research Original Investigation Association of Urbanicity With Psychosis in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

Figure 2. Countrywise Association Between Urban Residence (Exposure) and Psychotic Disorder (Outcome)

by Country Income Level

A Low-income countries

No. of Favors No Psychotic Favors Psychotic Weight,

Country Respondents OR (95% CI) Disorder Disorder %

Bangladesh 5942 1.67 (0.73-3.80) 6.81

Burkina Faso 4948 0.88 (0.38-2.06) 6.58

Chad 4870 1.10 (0.64-1.89) 10.90

Ethiopia 5089 1.53 (0.83-2.83) 9.67

Ghana 4165 1.81 (0.76-4.30) 6.39

Kenya 4640 1.19 (0.33-4.36) 3.45

Laos 4988 2.23 (0.67-7.49) 3.85

Malawi 5551 0.70 (0.17-2.84) 3.03

Mali 4886 0.42 (0.18-0.98) 6.62

Mauritania 3902 0.81 (0.37-1.79) 7.25

Myanmar 6045 1.15 (0.28-4.67) 3.02

Nepal 8820 0.71 (0.39-1.30) 9.81

Pakistan 6501 0.72 (0.35-1.47) 8.10

Senegal 3461 0.28 (0.11-0.70) 5.88

Zambia 4165 0.93 (0.28-3.07) 3.92

Zimbabwe 4290 0.50 (0.17-1.44) 4.74

Overall heterogeneity: 82 263 0.91 (0.70-1.18) 100.00

I 2 = 32.4%, P =.10

0.01 1.0 97.0

OR (95% CI)

B Middle-income countries

No. of Favors No Psychotic Favors Psychotic Weight,

Country Respondents OR (95% CI) Disorder Disorder %

Bosnia and Herzegovina 1031 1.90 (0.14-26.47) 0.67

Brazil 5000 0.99 (0.47-2.11) 6.17

Croatia 993 0.90 (0.31-2.61) 3.58

Czech Republic 949 4.83 (0.46-50.12) 0.84

Dominican Republic 5027 0.54 (0.23-1.24) 5.22

Ecuador 5675 1.12 (0.42-3.02) 4.02

Estonia 1020 12.17 (1.53-97.03) 1.06

Georgia 2950 0.98 (0.27-3.52) 2.60

Hungary 1419 0.62 (0.30-1.28) 6.40

Kazakhstan 4499 0.34 (0.11-1.08) 3.06

Latvia 929 1.05 (0.11-10.31) 0.88

Malaysia 6145 1.70 (0.43-6.78) 2.26

Mauritius 3968 0.53 (0.20-1.42) 4.07

Mexico 38 746 1.56 (0.87-2.78) 8.79

Morocco 5000 1.93 (0.62-6.00) 3.18

Namibia 4379 0.86 (0.43-1.69) 7.07

Paraguay 5288 0.73 (0.30-1.80) 4.73

Philippines 10 083 0.41 (0.19-0.89) 5.86

South Africa 2629 0.50 (0.19-1.30) 4.27

Sri Lanka 6805 1.41 (0.28-7.19) 1.67 Associations are estimated with

Swaziland 3117 0.86 (0.51-1.47) 9.69 multivariable logistic regression

Tunisia 5202 0.76 (0.43-1.34) 9.03 adjusting for age and sex. Estimates

2.93

for Vietnam and Slovakia could not be

Ukraine 2860 1.74 (0.53-5.73)

obtained because no individuals were

Uruguay 2996 1.26 (0.28-5.60) 1.95

found with psychotic disorder in one

Overall heterogeneity: 126 710 0.88 (0.71-1.10) 100.00

of the settings (ie, rural or urban). The

I 2 = 19.5%, P =.20

overall estimate and weights were

0.01 1.0 97.0 calculated by random-effects

OR (95% CI) meta-analysis. OR indicates odds

ratio; diamond, heterogeneity.

0.18-0.98), Senegal (OR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.11-0.70), and the Phil- 1.06). Multivariable logistic regression analysis pooling all coun-

ippines (OR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.19-0.89). A low level of hetero- tries and adjusting for age, sex, and country yielded similar

geneity was indicated among countries (I2 = 23%; 95% CI, 0%- results with an overall OR of 0.92 (95% CI, 0.73-1.16), OR for

48%). The pooled OR for the association between urbanicity low-income countries of 0.92 (95% CI, 0.66-1.27), and OR for

and psychotic disorder for all LMICs was 0.89 (95% CI, 0.76- middle-income countries of 0.92 (95% CI, 0.67-1.27).

E6 JAMA Psychiatry Published online May 16, 2018 (Reprinted) jamapsychiatry.com

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: by a University of Toledo Libraries User on 05/22/2018

Association of Urbanicity With Psychosis in Low- and Middle-Income Countries Original Investigation Research

tion within a country and within areas with the same major-

Discussion ity ethnic group carries similar mental health risks39; how-

ever, this has not specifically been examined in relation to

Main Findings psychosis, to our knowledge. Furthermore, LMICs are known

The primary finding of this study was that urban living was not to host most of the world’s refugees,40 particularly in urban

associated with subthreshold psychotic experiences or self- areas, and these individuals may be at greater risk for

reported psychotic disorder in a large sample of adults from psychosis.41

42 LMICs. This finding was true for low-income countries and Another factor is that cannabis use is more common in cit-

middle-income countries. In contrast, research to date, pri- ies compared with rural areas in high-income countries but is

marily in Western high-income countries,2-4 links urban liv- less prevalent overall in most LMICs.10 However, this differ-

ing with psychosis. The large sample and limited adjust- ence may be offset by the availability of other potentially psy-

ments in our analysis (age and sex only) indicate that our null chotogenic substances such as khat42; untangling these asso-

findings are not attributable to a lack of statistical power or ciations will require greater understanding of the urban-rural

overspecification of our models because we had sufficient distribution of substances in LMICs as well as more conclu-

power to detect even small effects (power of 0.99 to detect an sive data regarding which substances may be causally related

OR≥1.06 for psychotic experiences and OR≥1.20 for psy- to psychosis onset. Other possible factors include genetic se-

chotic disorder). Furthermore, the high response rate of the lection effects, because individuals at genetic risk for schizo-

WHS and our inclusion of only countries that used nationally phrenia have a greater tendency to cluster and remain in the

representative probability samples reduces the likelihood that same place in urban settings in some high-income countries

our null findings can be better explained by sampling error or (ie, the Netherlands, Dutch Belgium, and Sweden,43-45 but not

other methodologic biases. consistently across age groups in Denmark46), although why

a similar effect would not be present in LMICs is not clear.

Potential Mechanisms and Their Variance Between Urban-rural differences in stress reactivity and trauma expo-

High-income Countries and LMICs sure may also underlie the urbanicity effect, 47 although

Combining the findings of this large study with the existing evidence from cardiovascular risk research suggests that

body of literature, which consists of mainly high-income coun- urban-rural differences in stress level appear to also general-

try samples, suggests that the association between urban liv- ize to LMICs.48 Finally, various other biological mechanisms

ing and psychosis may be exclusive to high-income coun- have been proposed to explain the urban-rural difference in

tries. Furthermore, a recent review of the literature in China high-income countries, including greater ownership of cats in

(a middle-income country)32 showed a shift from having no enclosed spaces, which can lead to toxoplasmosis infection,49

association to a significant association between urbanicity and greater air pollution exposure (although this tends to be more

schizophrenia as the country underwent rapid urbanization rather than less pronounced in LMICs50), and less sun expo-

in 2 decades. This discrepancy in findings between high- sure and more vitamin D deficiency in high-income countries,51

income countries and LMICs has important implications about all of which warrant further exploration in future studies.

urbanicity as a risk factor for psychosis, because understand-

ing how urban-rural settings differ in high-income countries Strengths and Limitations

but not in LMICs can give us clues as to what urbanicity may Strengths of the present study include a large multinational

be a proxy for in those settings. Speculatively, urban-rural dis- sample that allowed sufficient statistical power to draw con-

parities in economic deprivation and social isolation in high- clusions from null results. The null result was replicated across

income countries may not be present or may be less evident psychotic disorders and psychotic experiences, as well as across

in LMICs. Affluent members of society tend to populate sub- low-income countries and middle-income countries, with each

urban areas in high-income countries, which differs from de- replication consisting of a meta-analysis of data across 42

veloping countries.3 Furthermore, familial and social cohe- countries and thousands of individuals and yielding similar fi-

sion may remain stronger in urban areas of developing nal effect sizes, all of which approached an OR of 1.00 (ie, a

countries.33 A recent English study,34 for example, demon- null effect). The inclusion of 42 LMICs allowed comparison of

strated that the risk for psychosis is also elevated in nonur- statistical effects across nations without publication bias, as

ban areas with low social cohesion and high poverty (which may be present when comparing results across single-

are typically features of urban environments). In addition, high- country studies.

income countries typically have relatively large immigrant and A limitation of this study is that we could not directly com-

ethnic minority populations compared with LMICs (which may pare LMICs with a globally representative range of high-

have more within-country migration), and these individuals income countries in the same data set. The association

typically reside in urban areas.35,36 This idea is consistent with between urbanicity and psychosis may not be as consistent across

past findings from high-income countries that show a re- all high-income countries, given that a large proportion of stud-

duced association between urbanicity and psychosis among ies published to date have come from a few high-income

racial/ethnic minorities who reside in areas of high within- countries.2-4 Of note, recent data from the multinational Euro-

group ethnic density.37,38 However, immigration factors and pean Network of National Schizophrenia Networks Studying

race/ethnicity may not explain discrepancies in urban effects Gene-Environment Interactions52 found no urbanicity effect in

between high-income countries and LMICs, because migra- data pooled across 9 high-income European countries and

jamapsychiatry.com (Reprinted) JAMA Psychiatry Published online May 16, 2018 E7

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: by a University of Toledo Libraries User on 05/22/2018

Research Original Investigation Association of Urbanicity With Psychosis in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

Brazil and found in their within-country analysis that urban liv- The use of a single self-report item to identify cases of psy-

ing was only associated with greater incidence of psychosis in chotic disorder was also a limitation although is consistent with

England and the Netherlands. prior psychiatric epidemiologic work. The overall prevalence

Because the data are cross-sectional, we were not able to of psychotic disorders in the countries included in the study

differentially explore the effect of living in an urban environ- was 0.9%, which is similar to previously reported figures in

ment at different life stages. The literature on urbanicity and the general population.55 Furthermore, the results were con-

psychosis from high-income countries benefits from greater sistent across diagnoses of psychotic disorder and psychotic

availability of longitudinal data,4 and the discrepancy of find- experiences.

ings may in part be explained by our use of psychosis preva-

lence rather than incidence data to study urbanicity as a risk

factor. However, no data set exists, to our knowledge, that com-

bines the broad LMIC representativeness of the WHS with a

Conclusions

longitudinal survey design. In the largest study to date, to our knowledge, of the associa-

Psychotic experiences were assessed using the WHO CIDI tion between urbanicity and psychosis in LMICs, we found that

screen, which does not attempt to exclude experiences that urban living was not associated with psychotic experiences or

may be culturally appropriate. However, past studies24,31,53,54 psychotic disorder. These findings contrast with the existing

have shown that psychotic experiences assessed using this body of literature on this subject, which has been conducted

measure are associated with clinical indicators across the en- primarily in high-income countries. This divergence suggests

tire range of LMICs included in this data set (eg, medical prob- that the association between urbanicity and psychosis, rather

lems, sleep disturbances, and stress sensitivity), suggesting that than being a universal phenomenon, may be a feature of in-

they are indexing phenomena that are clinically meaningful dustrialized countries only. Further research is needed to clarify

(on average) and are not entirely driven by misclassification the causative factors underlying this differential relationship

of culturally appropriate experiences. between LMICs and high-income countries.

ARTICLE INFORMATION 2. March D, Hatch SL, Morgan C, et al. Psychosis 12. Lundberg P, Cantor-Graae E, Rukundo G,

Accepted for Publication: February 21, 2018. and place. Epidemiol Rev. 2008;30(1):84-100. Ashaba S, Ostergren PO. Urbanicity of place of birth

3. Padhy SK, Sarkar S, Davuluri T, Patra BN. Urban and symptoms of psychosis, depression and

Published Online: May 16, 2018. anxiety in Uganda. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(2):

doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0577 living and psychosis—an overview. Asian J Psychiatr.

2014;12:17-22. 156-162.

Author Contributions: Drs DeVylder and Koyanagi 13. Gureje O, Olowosegun O, Adebayo K, Stein DJ.

had full access to all the data in the study and take 4. Vassos E, Pedersen CB, Murray RM, Collier DA,

Lewis CM. Meta-analysis of the association of The prevalence and profile of non-affective

responsibility for the integrity of the data and the psychosis in the Nigerian Survey of Mental Health

accuracy of the data analysis. urbanicity with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2012;

38(6):1118-1123. and Wellbeing. World Psychiatry. 2010;9(1):50-55.

Study concept and design: DeVylder, Oh, Link,

Koyanagi. 5. McGrath J, Scott J. Urban birth and risk of 14. Patel V, Simbine AP, Soares IC, Weiss HA,

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: schizophrenia: a worrying example of epidemiology Wheeler E. Prevalence of severe mental and

DeVylder, Kelleher, Lalane, Link, Koyanagi. where the data are stronger than the hypotheses. neurological disorders in Mozambique:

Drafting of the manuscript: DeVylder, Lalane, Oh, Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2006;15(4):243-246. a population-based survey. Lancet. 2007;370

Koyanagi. (9592):1055-1060.

6. Kelly BD, O’Callaghan E, Waddington JL, et al.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important Schizophrenia and the city: a review of literature 15. Mlambo K. Does mental health matter?

intellectual content: All authors. and prospective study of psychosis and urbanicity commentary on the provision of mental health

Statistical analysis: DeVylder, Koyanagi. in Ireland. Schizophr Res. 2010;116(1):75-89. services in Mozambique. Int Psychiatry. 2012;9(2):

Administrative, technical, or material support: 36-38.

Kelleher, Lalane. 7. van Os J, Kenis G, Rutten BPF. The environment

and schizophrenia. Nature. 2010;468(7321):203-212. 16. Ganguli HC. Epidemiological findings on

Study supervision: DeVylder. prevalence of mental disorders in India. Indian J

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported. 8. Scott J, Chant D, Andrews G, McGrath J. Psychiatry. 2000;42(1):14-20.

Psychotic-like experiences in the general

Funding/Support: This study is supported by the community: the correlates of CIDI psychosis screen 17. Thara R, Padmavati R, Srinivasan TN. Focus on

Miguel Servet contract financed by the CP13/00150 items in an Australian sample. Psychol Med. 2006; psychiatry in India. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:366-

and PI15/00862 projects, integrated into the 36(2):231-238. 373.

National R + D + I and funded by the Instituto de 18. Jiloha RC, Kukreti P. Caregivers as the fulcrum

Salud Carlos III–General Branch Evaluation and 9. Boonstra N, Sterk B, Wunderink L, Sytema S,

De Haan L, Wiersma D. Association of treatment of care for mentally ill in the community: the urban

Promotion of Health Research and the European rural divide among caregivers and care giving

Regional Development Fund (Dr Koyanagi). delay, migration and urbanicity in psychosis. Eur

Psychiatry. 2012;27(7):500-505. facilities. Indian J Soc Psychiatry. 2016;32:35-39.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The sponsor had no 19. World Health Organization. WHO World Health

role in the design and conduct of the study; 10. Whiteford HA, Ferrari AJ, Degenhardt L, Feigin

V, Vos T. The global burden of mental, neurological Survey. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/en/.

collection, management, analysis, and Updated February 11, 2016. Accessed December 8,

interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or and substance use disorders: an analysis from the

Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. PLoS One. 2017.

approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit

the manuscript for publication. 2015;10(2):e0116820. doi:10.1371/journal.pone 20. United Nations Department of Economic and

.0116820 Social Affairs. World Urbanization Prospects, the

REFERENCES 11. Lundberg P, Cantor-Graae E, Kabakyenga J, 2014 Revision. https://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/.

Rukundo G, Ostergren PO. Prevalence of delusional Updated January 2, 2018. Accessed February 12,

1. Faris REL, Dunham HW. Mental Disorders in 2018.

Urban Areas: An Ecological Study of Schizophrenia ideation in a district in southwestern Uganda.

And Other Psychoses. Oxford, England: University of Schizophr Res. 2004;71(1):27-34.

Chicago Press; 1939.

E8 JAMA Psychiatry Published online May 16, 2018 (Reprinted) jamapsychiatry.com

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: by a University of Toledo Libraries User on 05/22/2018

Association of Urbanicity With Psychosis in Low- and Middle-Income Countries Original Investigation Research

21. Novak NL, Allender S, Scarborough P, West D. risk of developing psychotic disorders in rural 46. Paksarian D, Trabjerg BB, Merikangas KR, et al.

The development and validation of an urbanicity populations: findings from the social epidemiology The role of genetic liability in the association of

scale in a multi-country study. BMC Public Health. of psychoses in East Anglia study. JAMA. 2018;75(1): urbanicity at birth and during upbringing with

2012;12:530. 75-83. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3582 schizophrenia in Denmark. Psychol Med. 2018;48

22. Kessler RC, Ustün TB. The World Mental Health 35. Card D. How immigration affects US cities. In: (2):305-314.

(WMH) Survey Initiative version of the World Inman RP, ed. Making Cities Work: Prospects and 47. Steinheuser V, Ackermann K, Schönfeld P,

Health Organization (WHO) Composite Policies for Urban America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Schwabe L. Stress and the city: impact of urban

International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Int J University Press; 2009:158-200. upbringing on the (re)activity of the

Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(2):93-121. 36. World Bank. Net migration. https://data hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis. Psychosom Med.

23. Cooper L, Peters L, Andrews G. Validity of the .worldbank.org/indicator/SM.POP.NETM. Accessed 2014;76(9):678-685.

Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) March 11, 2017. 48. Hernández AV, Pasupuleti V, Deshpande A,

psychosis module in a psychiatric setting. 37. Schofield P, Ashworth M, Jones R. Ethnic Bernabé-Ortiz A, Miranda JJ. Effect of

J Psychiatr Res. 1998;32(6):361-368. isolation and psychosis: re-examining the ethnic rural-to-urban within-country migration on

24. DeVylder JE, Koyanagi A, Unick J, Oh H, Nam B, density effect. Psychol Med. 2011;41(6):1263-1269. cardiovascular risk factors in low- and

Stickley A. Stress sensitivity and psychotic middle-income countries: a systematic review. Heart.

38. Das-Munshi J, Bécares L, Boydell JE, et al. 2012;98(3):185-194.

experiences in 39 low- and middle-income Ethnic density as a buffer for psychotic experiences:

countries. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42(6):1353-1362. findings from a national survey (EMPIRIC). 49. Torrey EF, Yolken RH. The urban risk and

25. StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;201(4):282-290. migration risk factors for schizophrenia: are cats the

College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2015. answer? Schizophr Res. 2014;159(2-3):299-302.

39. Siriwardhana C, Stewart R. Forced migration

26. United Nations DESA/Population Division. and mental health: prolonged internal 50. Gordon SB, Bruce NG, Grigg J, et al.

Population pyramid 2010. https://esa.un.org/wpp displacement, return migration and resilience. Int Respiratory risks from household air pollution in

/Excel-Data/population.htm. Updated January 2, Health. 2013;5(1):19-23. low and middle income countries. Lancet Respir Med.

2018. Accessed December 8, 2017. 2014;2(10):823-860.

40. UN Refugee Agency. Mid-year trends 2016.

27. Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying http://www.unhcr.org/statistics/unhcrstats 51. Belvederi Murri M, Respino M, Masotti M, et al.

heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002; /58aa8f247/mid-year-trends-june-2016.html. 2016. Vitamin D and psychosis: mini meta-analysis.

21(11):1539-1558. Accessed January 17, 2018. Schizophr Res. 2013;150(1):235-239.

28. McGrath JJ, Saha S, Al-Hamzawi AO, et al. Age 41. Anderson KK, Cheng J, Susser E, McKenzie KJ, 52. Jongsma HE, Gayer-Anderson C, Lasalvia A,

of onset and lifetime projected risk of psychotic Kurdyak P. Incidence of psychotic disorders among et al; European Network of National Schizophrenia

experiences: cross-national data from the World first-generation immigrants and refugees in Networks Studying Gene-Environment Interactions

Mental Health Survey. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42(4): Ontario. CMAJ. 2015;187(9):E279-E286. Work Package 2 (EU-GEI WP2) Group. Treated

933-941. incidence of psychotic disorders in the

42. Adorjan K, Odenwald M, Widmann M, et al. multinational EU-GEI study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;

29. Thompson JL, Pogue-Geile MF, Grace AA. Khat use and occurrence of psychotic symptoms in 75(1):36-46.

Developmental pathology, dopamine, and stress: the general male population in Southwestern

a model for the age of onset of schizophrenia Ethiopia: evidence for sensitization by traumatic 53. Moreno C, Nuevo R, Chatterji S, Verdes E,

symptoms. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30(4):875-900. experiences. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):323. Arango C, Ayuso-Mateos JL. Psychotic symptoms

are associated with physical health problems

30. Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A. Multilevel 43. Grech A, van Os J; GROUP Investigators. independently of a mental disorder diagnosis:

modelling of complex survey data. J R Stat Soc. Evidence that the urban environment moderates results from the WHO World Health Survey. World

2006;169:805-827. the level of familial clustering of positive psychotic Psychiatry. 2013;12(3):251-257.

31. Koyanagi A, Stickley A, Haro JM. Psychotic symptoms. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43(2):325-331.

54. Nuevo R, Chatterji S, Verdes E, Naidoo N,

symptoms and smoking in 44 countries. Acta 44. Sariaslan A, Fazel S, D’Onofrio BM, et al. Arango C, Ayuso-Mateos JL. The continuum of

Psychiatr Scand. 2016;133(6):497-505. Schizophrenia and subsequent neighborhood psychotic symptoms in the general population:

32. Chan KY, Zhao FF, Meng S, et al. Urbanization deprivation: revisiting the social drift hypothesis a cross-national study. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38(3):

and the prevalence of schizophrenia in China using population, twin and molecular genetic data. 475-485.

between 1990 and 2010. World Psychiatry. 2015;14 Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6:e796.

55. McGrath J, Saha S, Chant D, Welham J.

(2):251-252. 45. Sariaslan A, Larsson H, D’Onofrio B, Långström Schizophrenia: a concise overview of incidence,

33. Avasthi A. Preserve and strengthen family to N, Fazel S, Lichtenstein P. Does population density prevalence, and mortality. Epidemiol Rev. 2008;30:

promote mental health. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010; and neighborhood deprivation predict 67-76.

52(2):113-126. schizophrenia? a nationwide Swedish family-based

study of 2.4 million individuals. Schizophr Bull. 2015;

34. Richardson L, Hameed Y, Perez J, Jones PB, 41(2):494-502.

Kirkbride JB. Association of environment with the

jamapsychiatry.com (Reprinted) JAMA Psychiatry Published online May 16, 2018 E9

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: by a University of Toledo Libraries User on 05/22/2018

You might also like

- (Solved) QUESTION ONE Brick by Brick (BBB) Is A BuildingDocument6 pages(Solved) QUESTION ONE Brick by Brick (BBB) Is A BuildingBELONG TO VIRGIN MARYNo ratings yet

- SUMMATIVE TEST IN SCIENCE 6 (Fourth Quarter)Document3 pagesSUMMATIVE TEST IN SCIENCE 6 (Fourth Quarter)Cindy Mae Macamay100% (2)

- 1 s2.0 S1697260022000102 Main PDFDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S1697260022000102 Main PDFLauraLoaizaNo ratings yet

- 2023 - Fares Otero - Association Between Childhood Maltreatment and Social Functioning inDocument23 pages2023 - Fares Otero - Association Between Childhood Maltreatment and Social Functioning inxfxjose14No ratings yet

- Cópia de Cortisol em Esquiz. e TABDocument13 pagesCópia de Cortisol em Esquiz. e TABLuciana OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Smartphone-based Interventions in Bipolar Disorder- Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses of Efficacy. a Position Paper From the International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) Big Data Task Force_2022Document35 pagesSmartphone-based Interventions in Bipolar Disorder- Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses of Efficacy. a Position Paper From the International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) Big Data Task Force_2022cesia leivaNo ratings yet

- Fonseca-Pedrero - Network - Fron - PsychiDocument10 pagesFonseca-Pedrero - Network - Fron - PsychiifclarinNo ratings yet

- Workstructureofpsychotic LikeexperiencesinDocument12 pagesWorkstructureofpsychotic LikeexperiencesinifclarinNo ratings yet

- UC San Diego Previously Published WorksDocument12 pagesUC San Diego Previously Published WorkszahoNo ratings yet

- Conectividad Modo Predeterminado Depresion 2022Document9 pagesConectividad Modo Predeterminado Depresion 2022Sofía Flórez CastilloNo ratings yet

- Inflexibility Processes As Predictors of Social Functioning in Chronic PsychosisDocument12 pagesInflexibility Processes As Predictors of Social Functioning in Chronic PsychosisifclarinNo ratings yet

- Nieto, 2022Document10 pagesNieto, 2022Hector GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Protocolo Transdiagnostico AdolescentesDocument20 pagesProtocolo Transdiagnostico AdolescentesAdriana Barrera100% (1)

- Candidate Risks Indicators For Bipolar Disorder Early Intervention Opportunities in High-Risk YouthDocument37 pagesCandidate Risks Indicators For Bipolar Disorder Early Intervention Opportunities in High-Risk YouthThierry BernyNo ratings yet

- Dejong e 2016Document23 pagesDejong e 2016SATRIO BAGAS SURYONEGORONo ratings yet

- Jamapsychiatry Bansal 2021 Oi 210069 1643689382.76996Document9 pagesJamapsychiatry Bansal 2021 Oi 210069 1643689382.76996hye soo kimNo ratings yet

- Ni Hms 902154Document26 pagesNi Hms 902154Zeynep ÖzmeydanNo ratings yet

- 2021 - Investigacion - Publicaciones - Detectaweb DistressDocument14 pages2021 - Investigacion - Publicaciones - Detectaweb DistressJose Antonio Piqueras RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Boada2020 Article SocialCognitionInAutismAndSchiDocument14 pagesBoada2020 Article SocialCognitionInAutismAndSchiSara BenitoNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0149763417307583 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S0149763417307583 MainjackNo ratings yet

- The Mental Health of Children Facing Collective Adversity: Poverty, Homelessness, War and DisplacementDocument35 pagesThe Mental Health of Children Facing Collective Adversity: Poverty, Homelessness, War and DisplacementPtrc Lbr LpNo ratings yet

- DCI Distanciamiento Compartimentalizacion Validacion PeronaDocument10 pagesDCI Distanciamiento Compartimentalizacion Validacion Peronashekina1982No ratings yet

- Associations Between Early Life Adversity, Reproduction-Oriented Life Strategy, and Borderline Personality DisorderDocument9 pagesAssociations Between Early Life Adversity, Reproduction-Oriented Life Strategy, and Borderline Personality DisorderAndrade GuiNo ratings yet

- A Systematic Review and Qualitative Evidence Synthesis.: ArticleDocument20 pagesA Systematic Review and Qualitative Evidence Synthesis.: ArticlePOLA KATALINA GARCÍANo ratings yet

- Finales Art15 Acta 26 (2) 4609 Experiential+Avoidance+and+HyperreflexivityDocument13 pagesFinales Art15 Acta 26 (2) 4609 Experiential+Avoidance+and+HyperreflexivityJaime AguilarNo ratings yet

- Recovery-Focused Metacognitive Interpersonal Therapy (MIT) For AdolescentsDocument10 pagesRecovery-Focused Metacognitive Interpersonal Therapy (MIT) For AdolescentsCesar BermudezNo ratings yet

- Neurobiology Eld. SuicideDocument48 pagesNeurobiology Eld. SuicideAldo GuascoNo ratings yet

- Ribeiro 2017Document9 pagesRibeiro 2017Havadi KrisztaNo ratings yet

- J Nerv Ment Dis (Fucntional Impairment in Older Adults With Bipolar DiosrderDocument5 pagesJ Nerv Ment Dis (Fucntional Impairment in Older Adults With Bipolar DiosrderPaula Vergara MenesesNo ratings yet

- Personal View: Daniel Vigo, Graham Thornicroft, Rifat AtunDocument8 pagesPersonal View: Daniel Vigo, Graham Thornicroft, Rifat AtunRodrigo SilvaNo ratings yet

- Environmental Risk Factors and Biomarkers For Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Umbrella Review of The EvidenceDocument11 pagesEnvironmental Risk Factors and Biomarkers For Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Umbrella Review of The EvidenceLaurenLuodiYuNo ratings yet

- Issn: IssnDocument12 pagesIssn: IssnMailen RepettoNo ratings yet

- Perceived Stress and Mild Cognitive Impairment Among 32,715 Community-Dwelling Older Adults Across Six Low-And Middle-Income CountriesDocument9 pagesPerceived Stress and Mild Cognitive Impairment Among 32,715 Community-Dwelling Older Adults Across Six Low-And Middle-Income CountriesIshani SharmaNo ratings yet

- Attitudes and Intended Behaviour To Mental Disorders and Associated Factors in Catalan Population, Spain: Cross-Sectional Population-Based SurveyDocument12 pagesAttitudes and Intended Behaviour To Mental Disorders and Associated Factors in Catalan Population, Spain: Cross-Sectional Population-Based SurveyyeyesNo ratings yet

- Bautista Et Al. 2023 Padres Niños CáncerDocument13 pagesBautista Et Al. 2023 Padres Niños CáncerDiazAlejoPhierinaNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Scog 2019 01 001Document7 pages10 1016@j Scog 2019 01 001yohana ncNo ratings yet

- Association of Psychiatric Disorders With Mortality Among Patients With COVID-19Document7 pagesAssociation of Psychiatric Disorders With Mortality Among Patients With COVID-19DavidNo ratings yet

- Quantitative Methods in Development Research (DEVQUAN)Document23 pagesQuantitative Methods in Development Research (DEVQUAN)Cyan ValderramaNo ratings yet

- Anterior Insula Volume and Guilt Neurobehavioral Markers of RecurrenceDocument11 pagesAnterior Insula Volume and Guilt Neurobehavioral Markers of RecurrencehimeNo ratings yet

- Mental Disorders Among College Students in The World Health Organization World Mental Health SurveysDocument16 pagesMental Disorders Among College Students in The World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveyspaula cardenasNo ratings yet

- Attendance and Mental Health ProblemsDocument9 pagesAttendance and Mental Health ProblemsgabrielionitamitranNo ratings yet

- Levels of Distress Tolerance in Schizophrenia Appear Equivalent To Those Found in Borderline Personality Disorder.Document9 pagesLevels of Distress Tolerance in Schizophrenia Appear Equivalent To Those Found in Borderline Personality Disorder.danielaNo ratings yet

- Heliyon: A.D. Domínguez-Gonz Alez, G. Guzm An-Valdivia, F.S. Angeles-T Ellez, M.A. Manjarrez-Angeles, R. Secín-DiepDocument5 pagesHeliyon: A.D. Domínguez-Gonz Alez, G. Guzm An-Valdivia, F.S. Angeles-T Ellez, M.A. Manjarrez-Angeles, R. Secín-DiepAlejandro MartinezNo ratings yet

- Kessler 2007Document6 pagesKessler 2007Marmox Lab.No ratings yet

- Evaluation of Depression and Coping Skill Among HIV-Positive People in Kolkata, IndiaDocument6 pagesEvaluation of Depression and Coping Skill Among HIV-Positive People in Kolkata, IndiaAFINA AZIZAHNo ratings yet

- Determination of Emotional Endophenotypes: A Validation of The Affective Neuroscience Personality Scales and Further PerspectivesDocument12 pagesDetermination of Emotional Endophenotypes: A Validation of The Affective Neuroscience Personality Scales and Further PerspectivesGiaNo ratings yet

- 2022 03 23 22272776 FullDocument21 pages2022 03 23 22272776 Fullsg.gis279No ratings yet

- Genomics and The Classification of Mental Illness: Focus On Broader CategoriesDocument4 pagesGenomics and The Classification of Mental Illness: Focus On Broader CategoriesSusi RutmalemNo ratings yet

- Jamapsychiatry Nemani 2021 Oi 200083 1616513405.12248Document7 pagesJamapsychiatry Nemani 2021 Oi 200083 1616513405.12248Mareesol Chan-TiopiancoNo ratings yet

- Positive Traits in The Bipolar Spectrum: The Space Between Madness and GeniusDocument15 pagesPositive Traits in The Bipolar Spectrum: The Space Between Madness and GeniusVinícius BranquinhoNo ratings yet

- Suicide Prevention Strategies Revisited 10-Year SystematicDocument14 pagesSuicide Prevention Strategies Revisited 10-Year Systematicmary morelliNo ratings yet

- DownloadDocument7 pagesDownloadDr. Nivas SaminathanNo ratings yet

- Suicidio 2Document25 pagesSuicidio 2csmc vida sanaNo ratings yet

- Anxious and Non Anxious Major Depression WorldwideDocument28 pagesAnxious and Non Anxious Major Depression WorldwideMariaAn DominguezNo ratings yet

- 2020 - Association of Early-Life Social and Digital Media Experiences With Development of Autism Spectrum Disorder-Like SymptomsDocument7 pages2020 - Association of Early-Life Social and Digital Media Experiences With Development of Autism Spectrum Disorder-Like SymptomsEl Tal RuleiroNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Mental Disorders Among Middle School Students in Shaoxing, China. 2023 Pei.Document9 pagesPrevalence of Mental Disorders Among Middle School Students in Shaoxing, China. 2023 Pei.udecapNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2215036623001992Document13 pages1 s2.0 S2215036623001992Jorge SalazarNo ratings yet

- Characterisation of Social Media Users To Understand Their HealthDocument10 pagesCharacterisation of Social Media Users To Understand Their HealthleeresvivirNo ratings yet

- Bondoy, Allysa Laine C. Malano, Jessa Mae R. Nolasco, Joshua Vince N. Ranario, Daniel Joseph A. Rodiño, Christine Hazel GDocument25 pagesBondoy, Allysa Laine C. Malano, Jessa Mae R. Nolasco, Joshua Vince N. Ranario, Daniel Joseph A. Rodiño, Christine Hazel GJoshua NolascoNo ratings yet

- Fpsyt 12 605676Document13 pagesFpsyt 12 605676Kevin EsquivelNo ratings yet

- Ijerph 17 02871Document10 pagesIjerph 17 02871pemulihanmasNo ratings yet

- Hearing Voices: Qualitative Inquiry in Early PsychosisFrom EverandHearing Voices: Qualitative Inquiry in Early PsychosisNo ratings yet

- Handed in Signed Internship Contract?: Clinical & ResearchDocument1 pageHanded in Signed Internship Contract?: Clinical & Research奚浩然No ratings yet

- Differential Diagnosis of Bipolar II Disorder and Borderline Personality DisorderDocument11 pagesDifferential Diagnosis of Bipolar II Disorder and Borderline Personality DisorderManu Cortes OsorioNo ratings yet

- All The World 'S A (Clinical) Stage: Rethinking Bipolar Disorder From A Longitudinal PerspectiveDocument9 pagesAll The World 'S A (Clinical) Stage: Rethinking Bipolar Disorder From A Longitudinal Perspective奚浩然No ratings yet

- Integrated Neurobiology of Bipolar Disorder: PsychiatryDocument24 pagesIntegrated Neurobiology of Bipolar Disorder: Psychiatry奚浩然No ratings yet

- Executive Board: Your Reference Our Reference Direct Line MaastrichtDocument4 pagesExecutive Board: Your Reference Our Reference Direct Line Maastricht奚浩然No ratings yet

- Real-Time Mobile Monitoring of Bipolar Disorder: A Review of Evidence and Future DirectionsDocument12 pagesReal-Time Mobile Monitoring of Bipolar Disorder: A Review of Evidence and Future Directions奚浩然No ratings yet

- Zimmerman 2017Document7 pagesZimmerman 2017奚浩然No ratings yet

- Boissonnault2021 Article BrainStimulationInAttentionDefDocument9 pagesBoissonnault2021 Article BrainStimulationInAttentionDef奚浩然No ratings yet

- Association of Urbanicity With Psychosis in Low-And Middle-Income CountriesDocument9 pagesAssociation of Urbanicity With Psychosis in Low-And Middle-Income Countries奚浩然No ratings yet

- A Transdiagnostic Review of Negative Symptom Phenomenology and EtiologyDocument18 pagesA Transdiagnostic Review of Negative Symptom Phenomenology and Etiology奚浩然No ratings yet

- Boissonnault2021 Article BrainStimulationInAttentionDefDocument9 pagesBoissonnault2021 Article BrainStimulationInAttentionDef奚浩然No ratings yet

- Goal Representations and Motivational Drive in Schizophrenia: The Role of Prefrontal-Striatal InteractionsDocument16 pagesGoal Representations and Motivational Drive in Schizophrenia: The Role of Prefrontal-Striatal Interactions奚浩然No ratings yet

- The Latent Structure of Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia: JAMA PsychiatryDocument9 pagesThe Latent Structure of Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia: JAMA Psychiatry奚浩然No ratings yet

- Vanos 2010Document11 pagesVanos 2010奚浩然No ratings yet

- Social Disadvantage, Linguistic Distance, Ethnic Minority Status and First-Episode Psychosis: Results From The EU-GEI Case - Control StudyDocument13 pagesSocial Disadvantage, Linguistic Distance, Ethnic Minority Status and First-Episode Psychosis: Results From The EU-GEI Case - Control Study奚浩然No ratings yet

- Can Cognitive Deficits Explain Differential Sensitivity To Life Events in Psychosis?Document7 pagesCan Cognitive Deficits Explain Differential Sensitivity To Life Events in Psychosis?奚浩然No ratings yet

- Vanos 2010Document11 pagesVanos 2010奚浩然No ratings yet

- PP2021 SocialEpi LitDocument2 pagesPP2021 SocialEpi Lit奚浩然No ratings yet

- Valmaggia 2015Document7 pagesValmaggia 2015奚浩然No ratings yet

- Einstein, 'Parachor' and Molecular Volume: Some History and A SuggestionDocument10 pagesEinstein, 'Parachor' and Molecular Volume: Some History and A SuggestionVIGHNESH BALKRISHNA LOKARENo ratings yet

- Sponge ColoringDocument3 pagesSponge ColoringMavel Madih KumchuNo ratings yet

- Daylight Factor - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument2 pagesDaylight Factor - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediadasaNo ratings yet

- Data Sheet 65hdDocument3 pagesData Sheet 65hdoniferNo ratings yet

- Introduction To LogicDocument4 pagesIntroduction To LogicLykwhat UwantNo ratings yet

- Practical Research 2: Quarter 1 - Module 2: Importance of Quantitative Research Across FieldsDocument16 pagesPractical Research 2: Quarter 1 - Module 2: Importance of Quantitative Research Across FieldsDivina Grace Rodriguez - LibreaNo ratings yet

- Zamak-3 XometryDocument1 pageZamak-3 XometryFrancisco BocanegraNo ratings yet

- Bs - Civil Engineering 2023 24Document1 pageBs - Civil Engineering 2023 24DawnNo ratings yet

- Script For HostingDocument2 pagesScript For HostingNes DuranNo ratings yet

- Transformers: 3.1 What Is Magnetic Material and Give Difference Between Magnetic and Non Magnetic MaterialDocument24 pagesTransformers: 3.1 What Is Magnetic Material and Give Difference Between Magnetic and Non Magnetic Materialkrishnareddy_chintalaNo ratings yet

- Earthquake Lateral Force Analysis: by by Dr. Jagadish. G. KoriDocument41 pagesEarthquake Lateral Force Analysis: by by Dr. Jagadish. G. Koripmali2No ratings yet

- 362100deff40258 Exde03 35Document44 pages362100deff40258 Exde03 35Daniel SdNo ratings yet

- Rainbow Water Stacking Influenced by Sugar Density and Principle of Flotation ExperimentDocument11 pagesRainbow Water Stacking Influenced by Sugar Density and Principle of Flotation ExperimentDan Luigi TipactipacNo ratings yet

- Abaqus Automatic Stabilization When and How To Use ItDocument8 pagesAbaqus Automatic Stabilization When and How To Use ItBingkuai bigNo ratings yet

- Year 3 Spring Block 1 Multiplcation and DivisionDocument32 pagesYear 3 Spring Block 1 Multiplcation and DivisionCeciNo ratings yet

- TIS - Chapter 4 - Global TIS - Preclass HandoutsDocument22 pagesTIS - Chapter 4 - Global TIS - Preclass HandoutsK59 Huynh Kim NganNo ratings yet

- Smart Sensors For Real-Time Water Quality Monitoring: Subhas Chandra Mukhopadhyay Alex Mason EditorsDocument291 pagesSmart Sensors For Real-Time Water Quality Monitoring: Subhas Chandra Mukhopadhyay Alex Mason EditorsmikeNo ratings yet

- Shadows of Esteren Universe PDFDocument293 pagesShadows of Esteren Universe PDFThibault Mlt EricsonNo ratings yet

- FIELD 01 2023 AxCmpDocument1 pageFIELD 01 2023 AxCmpAwadhiNo ratings yet

- Rational Equations 200516061645Document12 pagesRational Equations 200516061645Shikha AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Lines of Latitude and Longitude WorksheetDocument9 pagesLines of Latitude and Longitude Worksheetrenegade 1No ratings yet

- PCS EpgDocument7 pagesPCS EpgStore ZunnieNo ratings yet

- Reformation of Moral Philosophy and Its Foundation in Seerah of The Prophet MuhammadDocument15 pagesReformation of Moral Philosophy and Its Foundation in Seerah of The Prophet MuhammadMuhammad Idrees LashariNo ratings yet

- Bozic Niksa 2018 Chardak Ni Na Zemlji Ni Na Nebu PrikazDocument1 pageBozic Niksa 2018 Chardak Ni Na Zemlji Ni Na Nebu PrikazSanja LoncarNo ratings yet

- Declaration of Interdependence Steele 1976 2pgs GOV POLDocument2 pagesDeclaration of Interdependence Steele 1976 2pgs GOV POLsonof libertyNo ratings yet

- 2022 01 MED21A T1-Assessment QestionPaperDocument4 pages2022 01 MED21A T1-Assessment QestionPaperIshmael MvunyiswaNo ratings yet

- Bonding Process PDFDocument29 pagesBonding Process PDFglezglez1No ratings yet

- Las Math 8 Q1-W1 2021-2022Document3 pagesLas Math 8 Q1-W1 2021-2022Angela Camille PaynanteNo ratings yet