Professional Documents

Culture Documents

13 Heat20Stroke20NEJM206 02

Uploaded by

Vianah Eve EscobidoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

13 Heat20Stroke20NEJM206 02

Uploaded by

Vianah Eve EscobidoCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/11300013

Heat Stroke

Article in New England Journal of Medicine · July 2002

DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra011089 · Source: PubMed

CITATIONS READS

1,398 10,498

2 authors, including:

Abderrezak Bouchama

King Abdullah International Medical Research Center

93 PUBLICATIONS 6,025 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Mechanisms of heatstroke in primates View project

Heatstroke and heatstrss View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Abderrezak Bouchama on 02 June 2014.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

The Ne w E n g l a nd Jo u r n a l o f Me d ic i ne

Review Article

Medical Progress

TABLE 1. GLOSSARY OF TERMS.

CONDITION DEFINITION

H EAT S TROKE

Heat wave Three or more consecutive days during which

the air temperature is >32.2°C

ABDERREZAK BOUCHAMA, M.D., Heat stress Perceived discomfort and physiological strain

AND JAMES P. KNOCHEL, M.D. associated with exposure to a hot environ-

ment, especially during physical work

Heat stroke Severe illness characterized by a core temper-

H

ature >40°C and central nervous system

EAT stroke is a life-threatening illness charac- abnormalities such as delirium, convulsions,

terized by an elevated core body temperature or coma resulting from exposure to environ-

that rises above 40°C and central nervous mental heat (classic heat stroke) or strenuous

physical exercise (exertional heat stroke)

system dysfunction that results in delirium, convul- Heat exhaustion Mild-to-moderate illness due to water or salt

sions, or coma.1 Despite adequate lowering of the body depletion that results from exposure to high

temperature and aggressive treatment, heat stroke is environmental heat or strenuous physical

exercise; signs and symptoms include intense

often fatal, and those who do survive may sustain per- thirst, weakness, discomfort, anxiety, dizzi-

manent neurologic damage.1,2 Data from the Centers ness, fainting, and headache; core temper-

for Disease Control and Prevention show that from ature may be normal, below normal, or

slightly elevated (>37°C but <40°C)

1979 to 1997, 7000 deaths in the United States were Hyperthermia A rise in body temperature above the hypotha-

attributable to excessive heat.3 The incidence of such lamic set point when heat-dissipating mech-

deaths may increase with global warming and the pre- anisms are impaired (by drugs or disease) or

overwhelmed by external (environmental

dicted worldwide increase in the frequency and inten- or induced) or internal (metabolic) heat

sity of heat waves.4-8 Multiorgan-dysfunction Continuum of changes that occur in more than

Research performed during the past decade has syndrome one organ system after an insult such as trau-

shown that heat stroke results from thermoregulatory ma, sepsis, or heat stroke 24

failure coupled with an exaggerated acute-phase re-

sponse and possibly with altered expression of heat-

shock proteins.9-23 The ensuing multiorgan injury re-

sults from a complex interplay among the cytotoxic

effect of the heat and the inflammatory and coagula-

tion responses of the host.9-21 In this article, we sum-

marize the pathogenesis of heat stroke as it is currently or nonexertional, heat stroke) or from strenuous ex-

understood and explore the potential therapeutic and ercise (in which case it is called exertional heat stroke).1

preventive strategies. Key terms used in this discussion On the basis of our understanding of the pathophys-

are defined in Table 1. iology of heat stroke, we propose an alternative def-

DEFINITION AND INCIDENCE inition of this condition: it is a form of hyperthermia

associated with a systemic inflammatory response lead-

Heat stroke is defined clinically as a core body tem- ing to a syndrome of multiorgan dysfunction in which

perature that rises above 40°C and that is accompa- encephalopathy predominates.

nied by hot, dry skin and central nervous system ab- Data on the incidence of heat stroke are imprecise

normalities such as delirium, convulsions, or coma. because this illness is underdiagnosed and because the

Heat stroke results from exposure to a high environ- definition of heat-related death varies.25,26 In an ep-

mental temperature (in which case it is called classic, idemiologic study during heat waves in urban areas

in the United States, the incidence of heat stroke varied

from 17.6 to 26.5 cases per 100,000 population.26

From the Medical and Surgical Intensive Care Unit and Comparative

Medicine Department, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Cen-

Most people affected by classic heat stroke are very

ter, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (A.B.); and the Department of Internal Medicine, young or elderly, poor, and socially isolated and do not

Presbyterian Hospital of Dallas, Dallas (J.P.K.). Address reprint requests to have access to air conditioning.25,27 In Saudi Arabia,

Dr. Knochel at the Department of Internal Medicine, Presbyterian Hospital

of Dallas, 8198 Walnut Hill Ln., Dallas, TX 75231, or at jamesknochel@ the incidence varies seasonally, from 22 to 250 cases

texashealth.org. per 100,000 population.28 The crude mortality rate

1978 · N Engl J Med, Vol. 346, No. 25 · June 20, 2002 · www.nejm.org

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on November 20, 2003.

Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

MEDICAL PROGRESS

associated with heat stroke in Saudi Arabia is estimat- eventually allow a person to work safely at levels of

ed at 50 percent.28 heat that were previously intolerable or life-threaten-

The incidence of heat exhaustion in Saudi Arabia, ing.1 The process of acclimatization to heat takes sev-

in contrast, ranges from 450 to more than 1800 cases eral weeks and involves enhancement of cardiovascular

per 100,000 population. Why a mild illness develops performance, activation of the renin–angiotensin–

in response to heat (as in heat exhaustion) in some aldosterone axis, salt conservation by the sweat glands

people, whereas in others the condition progresses to and kidneys, an increase in the capacity to secrete

heat stroke, is unknown. Genetic factors may deter- sweat, expansion of plasma volume, an increase in the

mine the susceptibility to heat stroke; candidate sus- glomerular filtration rate, and an increase in the abil-

ceptibility genes include those that encode cytokines, ity to resist exertional rhabdomyolysis.35

coagulation proteins, and heat-shock proteins involved

in the adaptation to heat stress.13-23 Acute-Phase Response

The acute-phase response to heat stress is a coordi-

PATHOGENESIS

nated reaction that involves endothelial cells, leuko-

To understand the pathogenesis of heat stroke, the cytes, and epithelial cells and that protects against tis-

systemic and cellular responses to heat stress must be sue injury and promotes repair.36 Interleukin-1 was the

appreciated. These responses include thermoregula- first known mediator of the systemic inflammation in-

tion (with acclimatization), an acute-phase response, duced by strenuous exercise.37 A variety of cytokines

and a response that involves the production of heat- are now known to be produced in response to endog-

shock proteins. enous or environmental heat (Table 2).22,38-43,46-51 Cy-

Thermoregulation tokines mediate fever, leukocytosis, increased synthesis

Body heat is gained from the environment and is of acute-phase proteins, muscle catabolism, stimulation

produced by metabolism. This overall heat load must of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, and ac-

be dissipated to maintain a body temperature of 37°C, tivation of leukocytes and endothelial cells.22,51-53 The

interleukin-6 produced during heat stress modulates

a process called thermoregulation.1 A rise in the tem-

perature of the blood by less than 1°C activates pe- local and systemic acute inflammatory responses by

ripheral and hypothalamic heat receptors that signal controlling the levels of inflammatory cytokines 22,51,54;

interleukin-6 also stimulates hepatic production of an-

the hypothalamic thermoregulatory center,29 and the

efferent response from this center increases the deliv- tiinflammatory acute-phase proteins, which inhibit the

ery of heated blood to the surface of the body. Active production of reactive oxygen species and the release

sympathetic cutaneous vasodilation then increases of proteolytic enzymes from activated leukocytes.36,51,54

Other acute-phase proteins stimulate endothelial-cell

blood flow in the skin by up to 8 liters per minute.30

An increase in the blood temperature also initiates adhesion, proliferation, and angiogenesis, thus con-

thermal sweating.31,32 If the air surrounding the sur- tributing to repair and healing.36 The increased expres-

sion of the gene encoding interleukin-6 in human

face of the body is not saturated with water, sweat

muscle cells, but not in blood monocytes, during the

will vaporize and cool the body surface. The evapo-

acute-phase response to exercise suggests that the on-

ration of 1.7 ml of sweat will consume 1 kcal of heat

energy.32 At maximal efficiency in a dry environment, set of inflammation is local.22,41,42 The systemic pro-

gression of the inflammatory response is secondary

sweating can dissipate about 600 kcal per hour.31-33

The thermal gradient established by the evaporation and involves other cells, such as monocytes.41 A sim-

ilar sequence of events has been shown to occur in

of sweat is critical for the transfer of heat from the

sepsis.55

body to the environment. An elevated blood temper-

ature also causes tachycardia, increases cardiac output, Heat-Shock Response

and increases minute ventilation.1,30-33 As blood is

shunted from the central circulation to the muscles Nearly all cells respond to sudden heating by pro-

and skin to facilitate heat dissipation, visceral perfu- ducing heat-shock proteins or stress proteins.56,57 Ex-

sion is reduced, particularly in the intestines and kid- pression of heat-shock proteins is controlled primarily

neys.30 Losses of salt and water by sweating, which at the level of gene transcription. During heat stress,

may amount to 2 liters or more per hour, must be one or more heat-shock transcription factors bind to

balanced by generous salt supplementation to facili- the heat-shock element, resulting in an increased rate

tate thermoregulation.33,34 Dehydration and salt de- of transcription of heat-shock proteins.56,57 Increased

pletion impair thermoregulation.34 levels of heat-shock proteins in a cell induce a tran-

sient state of tolerance to a second, otherwise lethal,

Acclimatization stage of heat stress, allowing the cell to survive.23,56,57

Successive increments in the level of work per- Blocking the synthesis of heat-shock proteins either

formed in a hot environment result in adaptations that at the gene-transcription level or by specific antibodies

N Engl J Med, Vol. 346, No. 25 · June 20, 2002 · www.nejm.org · 1979

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on November 20, 2003.

Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The Ne w E n g l a nd Jo u r n a l o f Me d ic i ne

TABLE 2. EFFECT OF HEAT STRESS AND HEAT STROKE ON CIRCULATING CYTOKINES,

CYTOKINE RECEPTORS, GROWTH FACTORS, AND CHEMOKINES.*

CYTOKINE OR FACTOR HEAT STRESS HEAT STROKE REFERENCE

EXERCISE- ENVIRON- THERA-

INDUCED MENTAL PEUTIC† CLASSIC EXERTIONAL

Tumor necrosis Increased or Unchanged Increased or Increased or Increased Bouchama et al.,11 Espersen et al.,38

factor a unchanged unchanged unchanged Robins et al.,39 Camus et al.,40

Ostrowski et al.,41 Moldoveanu

et al.,42 Suzuki et al.,43 Chang44

Interleukin-1b Increased or NA Increased Increased or Increased Cannon and Kluger,37 Robins et al.,39

unchanged unchanged Ostrowski et al.,41 Moldoveanu

et al.,42 Chang,44 Bouchama et al.45

Interleukin-2 Decreased or NA Unchanged NA NA Espersen et al.,38 Robins et al.39

unchanged

Interleukin-6 Increased Increased Increased Increased Increased Robins et al.,39 Moldoveanu et al.,42

Suzuki et al.,43 Chang,44 Bouchama

et al.,45 Hammami et al.46

Interleukin-8 Increased NA Increased NA NA Pedersen and Hoffman-Goetz,22

Robins et al.,39 Suzuki et al.43

Interleukin-10 Increased Increased Increased Increased NA Pedersen and Hoffman-Goetz,22

Robins et al.,39 Suzuki et al.,43

Bouchama et al.47

Interleukin-12 Increased or NA Unchanged NA NA Pedersen and Hoffman-Goetz,22

unchanged Robins et al.,39 Suzuki et al.,43

Akimoto et al.48

Interleukin-1–receptor Increased NA NA NA NA Pedersen and Hoffman-Goetz,22

antagonist Ostrowski et al.,41 Suzuki et al.43

Soluble interleukin-2 Increased NA NA Increased NA Pedersen and Hoffman-Goetz,22

receptor Suzuki et al.,43 Hammami et al.46

Soluble interleukin-6 NA Increased NA Decreased NA Hammami et al.49

receptor

Soluble tumor necrosis Increased Increased or Increased Increased NA Pedersen and Hoffman-Goetz,22

factor receptors unchanged Hammami et al.49

(p55 and p75)

Interferon-g Increased or NA Unchanged Increased NA Pedersen and Hoffman-Goetz,22

unchanged Robins et al.,39 Suzuki et al.,43

Bouchama et al.45

Interferon-a Increased or NA Unchanged NA NA Suzuki et al.,43 Viti et al.50

unchanged

Granulocyte colony- Increased NA Increased NA NA Pedersen and Hoffman-Goetz,22

stimulating factor Robins et al.,39 Suzuki et al.43

Macrophage-inhibitor Increased NA Unchanged NA NA Pedersen and Hoffman-Goetz,22

proteins Robins et al.39

*Data are from studies in human subjects. NA denotes data not available.

†Whole-body hyperthermia may be induced in cancer therapy.

renders the cells extremely sensitive to a minor de- the baroreceptor-reflex response during severe heat

gree of heat stress.16,58 In vivo, cellular tolerance pro- stress, abating hypotension and bradycardia and con-

tects laboratory animals against hyperthermia, arterial ferring cardiovascular protection.16

hypotension, and cerebral ischemia.15,16 The protec-

tion conferred against heat-stroke injury correlates Progression from Heat Stress to Heat Stroke

with the level of heat-shock protein 72, which accu- Thermoregulatory failure, exaggeration of the acute-

mulates in the brain after the priming heat-shock treat- phase response, and alteration in the expression of

ment.15,16 The mechanism by which heat-shock pro- heat-shock proteins may contribute to the progression

teins protect cells may relate to their function as from heat stress to heat stroke.

molecular chaperones that bind to partially folded or

Thermoregulatory Failure

misfolded proteins, thus preventing their irreversible

denaturation.56 Another possible mechanism involves The normal cardiovascular adaptation to severe heat

heat-shock proteins that act as central regulators of stress is an increase in cardiac output by up to 20 liters

1980 · N Engl J Med, Vol. 346, No. 25 · June 20, 2002 · www.nejm.org

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on November 20, 2003.

Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

MEDICAL PROGRESS

per minute and a shift of heated blood from the core Alteration of Heat-Shock Response

circulation to the peripheral circulation.30 An inability Increased levels of heat-shock proteins protect cells

to increase cardiac output because of salt and water from damage by heat, ischemia, hypoxia, endotoxin,

depletion, cardiovascular disease, or a medication that and inflammatory cytokines.23,56,57 In persons who are

interferes with cardiac function can impair heat tol- subjected to heat stress, examination of muscle tissue,

erance and result in increased susceptibility to heat blood monocytes, and serum reveals that such a heat-

stroke.1 shock response occurs in vivo.17,65-67 Attenuation of the

Exaggeration of the Acute-Phase Response

heat-shock response during heat stroke suggests that

this adaptative response is protective.17,23 Conditions

It is possible that the gastrointestinal tract fuels the associated with a low level of expression of heat-

inflammatory response.12,40,59-63 During strenuous ex- shock proteins — for instance, aging, lack of acclima-

ercise or hyperthermia, blood shifts from the mesen- tization to heat, and certain genetic polymorphisms

teric circulation to the working muscles and the skin, — may favor the progression from heat stress to heat

leading to ischemia of the gut and intestinal hyper- stroke.17,23,68

permeability.12,30,59-63 There is abundant evidence of

hyperpermeability during heat stress in animal mod- PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

els but much less evidence of this phenomenon in Heat stroke and its progression to multiorgan-dys-

humans.9,10,12,59-63 In rats, heat stress leads to increased function syndrome are due to a complex interplay

metabolic demand and reduced splanchnic blood flow, among the acute physiological alterations associated

which in turn induce intestinal and hepatocellular with hyperthermia (e.g., circulatory failure, hypoxia,

hypoxia; the hypoxia results in the generation of high- and increased metabolic demand), the direct cytotox-

ly reactive oxygen and nitrogen species that acceler- icity of heat, and the inflammatory and coagulation

ate mucosal injury.12,59 responses of the host.11-15,18-21,44,45,69-72 This constella-

Intestinal mucosal permeability to iodine-125– tion of events leads to alterations in blood flow in the

labeled endotoxin increases in heat-stressed rats that microcirculation and results in injury to the vascular

have a core temperature of 45°C.60 In heat-stressed endothelium and tissues (Fig. 2).18,19,73-76

primates, endotoxin from the gut enters the circulation

at a core temperature of 40°C, and its concentration Heat

increases as the core temperature rises.9,10 Endotox- Studies in cell lines and animal models suggest that

emia may then cause hemodynamic instability and heat directly induces tissue injury.69,70 The severity of

death. Administration of antiendotoxin antibodies be- the injury depends on the critical thermal maximum,

fore heat stress occurs attenuates hemodynamic insta- a term that attempts to quantify the level and dura-

bility and improves outcome, suggesting that endotox- tion of heating that will initiate tissue injury.69-71 A

in is involved in the progression from heat stress to critical thermal maximum beyond which near-lethal

heat stroke.10 In humans, high concentrations of en- or lethal injury occurs has been determined in various

dotoxin, inflammatory cytokines, and acute-phase pro- mammalian species.71 Observations in selected groups,

teins are found in the blood after strenuous exer- including marathon runners, normal volunteers, and

cise.22,40,61,62 Increased intestinal permeability occurs patients with cancer who are treated with whole-body

in athletes exercising at 80 percent or more of max- hyperthermia, suggest that the critical thermal max-

imal oxygen consumption.61 imum in humans is a body temperature of 41.6°C to

In summary, in the model of heat stroke based on 42°C for 45 minutes to 8 hours.71 At extreme tem-

experiments in animals and observations in humans peratures (49°C to 50°C), all cellular structures are

(Fig. 1), local and systemic insults associated with heat destroyed and cellular necrosis occurs in less than five

stress, such as splanchnic hypoperfusion, alter the im- minutes.69 At lower temperatures, cell death is largely

munologic and barrier functions of the intestines.12,59-63 due to apoptosis.70 Although the pathways of heat-

This alteration allows leakage of endotoxins, increased induced apoptosis have not been identified, the in-

production of inflammatory cytokines that induce duction of heat-shock proteins is protective.57

endothelial-cell activation, and release of endothelial

vasoactive factors such as nitric oxide and endothe- Cytokines

lins.9,10,12,63,64 Both pyrogenic cytokines and endothe- The plasma levels of inflammatory cytokines (tumor

lium-derived factors can interfere with normal ther- necrosis factor a [TNF-a], interleukin-1b, and inter-

moregulation by raising the set point at which feron-g) and antiinflammatory cytokines (interleukin-

sweating is activated and by altering vascular tone, 6, soluble TNF receptors p55 and p75, and interleu-

particularly in the splanchnic circulation, thereby kin-10) are elevated in persons with heat stroke; cool-

precipitating hypotension, hyperthermia, and heat ing of the body to a normal temperature does not re-

stroke.9,10,12,63 sult in the suppression of these factors.11,44,45,47,49 The

N Engl J Med, Vol. 346, No. 25 · June 20, 2002 · www.nejm.org · 1981

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on November 20, 2003.

Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The Ne w E n g l a nd Jo u r n a l o f Me d ic i ne

Exercise or

heat exposure

Heat stress

Acute-phase Thermoregulatory Heat-shock

response response response

Cutaneous Splanchnic

vasodilatation vasoconstriction

Exaggerated Altered

acute-phase heat-shock

response response

Release of Production of

nitric oxide reactive oxygen

and nitrogen species

Increased intestinal

permeability

Endotoxemia

Thermoregulatory

failure, circulatory

shock, and

heat stroke

Figure 1. The Sequence of Events in the Progression of Heat Stress to Heat Stroke.

Heat stress induces thermoregulatory, acute-phase, and heat-shock responses. Thermoregulatory failure, exaggeration

of the acute-phase response, and alteration in the expression of heat-shock proteins, individually or collectively, may

contribute to the development of heat stroke. Active cutaneous vasodilatation and splanchnic vasoconstriction permit

the shift of heated blood from the central organs to the periphery, from which heat is then dissipated to the environ-

ment. This change may also lead to splanchnic hypoperfusion and ischemia, resulting in increased production of reac-

tive oxygen and nitrogen species, which may in turn induce intestinal mucosal injury and hyperpermeability. Endotox-

ins may then leak into the circulation and enhance the acute-phase response, leading to increased production of

pyrogenic cytokines and nitric oxide. Both cytokines and nitric oxide can interfere with thermoregulation and precipitate

hyperthermia, hypotension, and heat stroke. The solid arrows indicate pathways for which there is clinical or experi-

mental evidence, and the broken arrows indicate putative pathways.

1982 · N Engl J Med, Vol. 346, No. 25 · June 20, 2002 · www.nejm.org

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on November 20, 2003.

Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

MEDICAL PROGRESS

Inflammatory Response Coagulation Response

to Heat Stroke to Heat Stroke

Muscle

L-selectin

Decrease in

ICAM-1 protein C,

Interleukin-1, protein S,

interleukin-6 b2 integrin antithrombin III

Tissue factor

Monocyte Thrombin

Fibrin monomers Monocyte

Increase in TNF-a, Neutrophil

interleukin-1, Inhibition of

interleukin-6, fibrinolysis

interleukin-10

Increase in

von Willebrand Clot

Increase in

Endotoxin factor antigen E-selectin

Increase in

thrombomodulin

Intestine

Figure 2. Possible Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Heat Stroke.

Hyperthermia due to passive heat exposure or to exercise may facilitate the leakage of endotoxin from the intestine to the systemic

circulation as well as the movement of interleukin-1 or interleukin-6 proteins from the muscles to the systemic circulation. The result

is excessive activation of leukocytes and endothelial cells, manifested by the release of proinflammatory and antiinflammatory cy-

tokines (e.g., tumor necrosis factor a [TNF-a], interleukin-1, interleukin-6, and interleukin-10), up-regulation of cell-surface adhesion

molecules, and shedding of soluble cell-surface adhesion molecules (e.g., E-selectin, L-selectin, and intercellular adhesion molecule

1 [ICAM-1]) as well as activation of coagulation (with decreased levels of proteins C and S and antithrombin III) and inhibition of

fibrinolysis. The inflammatory and coagulation responses to heat stroke, together with direct cytotoxic effects of heat, result in in-

jury to the vascular endothelium and microthrombosis. The solid arrows indicate pathways for which there is clinical or experimen-

tal evidence, and the broken arrows indicate putative pathways.

N Engl J Med, Vol. 346, No. 25 · June 20, 2002 · www.nejm.org · 1983

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on November 20, 2003.

Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The Ne w E n g l a nd Jo u r n a l o f Me d ic i ne

levels of interleukin-6 and TNF receptors correlate stroke.18,19,53,64,79 Modulation of the expression of b 2-

with severity of heat stroke.45,49 integrins, characterized by up-regulation of CD11b

An imbalance between inflammatory and antiin- and down-regulation of CD11a on the surface of cir-

flammatory cytokines may result in either inflamma- culating lymphocytes, has been reported in patients

tion-associated injury or refractory immunosup- with heat stroke, suggesting that there is an active

pression. Although dynamic studies of the cytokine endothelial cell–leukocyte interaction in vivo.53

response in patients with heat stroke have not yet

been performed, both of these mechanisms may be CLINICAL AND METABOLIC

important. In patients with heat stroke, the incidence MANIFESTATIONS

of infection is high.2 Studies in rats and rabbits have Two findings — hyperthermia and central nervous

shown that heat stroke induces systemic and local system dysfunction — must be present for a diagno-

(central nervous system) production of TNF-a and sis of heat stroke (Table 3).1,86 The core temperature

interleukin-1.13,72 The increase in the levels of these may range from 40°C to 47°C.1 Brain dysfunction

inflammatory cytokines is associated with high intra- is usually severe but may be subtle, manifesting only

cranial pressure, decreased cerebral blood flow, and as inappropriate behavior or impaired judgment; more

severe neuronal injury. Interleukin-1–receptor antag- often, however, patients have delirium or frank co-

onists or corticosteroids given to animals before heat ma.1,86 Seizures may occur, especially during cooling.1

stroke attenuate neurologic injury, prevent arterial All patients have tachycardia and hyperventilation. In

hypotension, and improve survival.13,14 Although such either classic or exertional heat stroke, the arterial car-

studies support the possibility that cytokines have a bon dioxide tension is often less than 20 mm Hg.1

pathogenic role, studies of neutralizing antibodies or Twenty-five percent of patients have hypotension.86

genetically modified mice are needed to determine Patients with nonexertional heat stroke usually have

both the pattern and the role of these factors in heat respiratory alkalosis.1 In contrast, those with exertional

stroke. heat stroke nearly always have both respiratory alka-

losis and lactic acidosis.1 Hypophosphatemia and hy-

Coagulation Disorders and Endothelial-Cell Injury pokalemia are common at the time of admission.

Endothelial-cell injury and diffuse microvascular Hypoglycemia is rare. Hypercalcemia and hyperpro-

thrombosis are prominent features of heat stroke. teinemia, reflecting hemoconcentration, may also

Therefore, disseminated intravascular coagulation and occur. In patients with exertional heat stroke, rhabdo-

alterations in the vascular endothelium may be impor- myolysis, hyperphosphatemia, hypocalcemia, and hy-

tant pathologic mechanisms in heat stroke.18-21,73-76 perkalemia may be important events after complete

Studies involving the use of molecular markers of cooling.

coagulation and fibrinolysis have delineated the early The most serious complications of heat stroke are

steps of coagulation abnormalities.20,21 The onset of those falling within the category of multiorgan-dys-

heat stroke coincides with the activation of coagula- function syndrome. They include encephalopathy,

tion, as assessed by the appearance of thrombin–anti- rhabdomyolysis, acute renal failure, acute respiratory

thrombin III complexes and soluble fibrin monomers distress syndrome, myocardial injury, hepatocellular

and below-normal levels of protein C, protein S, and injury, intestinal ischemia or infarction, pancreatic in-

antithrombin III. Fibrinolysis is also highly activated, jury, and hemorrhagic complications, especially dis-

as shown by increased levels of plasmin–a2-antiplas- seminated intravascular coagulation, with pronounced

min complexes and D-dimers and decreased levels of thrombocytopenia.1,21

plasminogen. Normalization of the core temperature

inhibits fibrinolysis but not the activation of coagu- TREATMENT

lation, which continues; this pattern resembles that Immediate cooling and support of organ-system

seen in sepsis.20 function are the two main therapeutic objectives in

The endothelium controls vascular tone and per- patients with heat stroke (Table 3).1,2,80-87

meability, regulates leukocyte movement, and main-

tains a balance between procoagulant and anticoag- Cooling

ulant substances. Hyperthermia in vitro promotes a Effective heat dissipation depends on the rapid

prothrombotic state, enhances vascular permeability, transfer of heat from the core to the skin and from

and increases the cell-surface expression of adhesion the skin to the external environment.80-82 In persons

molecules and the shedding of their soluble form.77,78 with hyperthermia, transfer of heat from the core to

Circulating levels of von Willebrand factor antigen, the skin is facilitated by active cutaneous vasodilata-

thrombomodulin, endothelin, metabolites of nitric tion.30,81,82 Therapeutic cooling techniques are there-

oxide, soluble E-selectin, and intercellular adhesion fore aimed at accelerating the transfer of heat from

molecule 1 are elevated in patients with heat the skin to the environment without compromising

1984 · N Engl J Med, Vol. 346, No. 25 · June 20, 2002 · www.nejm.org

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on November 20, 2003.

Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

MEDICAL PROGRESS

TABLE 3. MANAGEMENT OF HEAT STROKE.*

CONDITION INTERVENTION GOAL

Out of hospital

Heat stress (due to heat wave, summer Measure the patient’s core temperature (with a rectal probe) Diagnose heat stroke†

heat, or strenuous exercise), with If the core temperature is >40°C, move the patient to a cool- Lower the core temperature to <39.4°C, pro-

changes in mental status (anxiety, er place, remove his or her clothing, and initiate external mote cooling by conduction, and promote

delirium, seizures, or coma) cooling‡: cold packs on the neck, axillae, and groin; con- cooling by evaporation

tinuous fanning (or opening of the ambulance windows);

and spraying of the skin with water at 25°C to 30°C

Position an unconscious patient on his or her side and clear Minimize the risk of aspiration

the airway

Administer oxygen at 4 liters/min Increase arterial oxygen saturation to >90%

Give isotonic crystalloid (normal saline) Provide volume expansion

Rapidly transfer the patient to an emergency department

In hospital

Cooling period Confirm diagnosis with thermometer calibrated to measure

high temperatures (40°C to 47°C)

Hyperthermia Monitor the rectal and skin temperatures; continue cooling Keep rectal temperature <39.4°C§ and skin

temperature 30°C–33°C

Seizures Give benzodiazepines Control seizures

Respiratory failure Consider elective intubation (for impaired gag and cough re- Protect airway and augment oxygenation (arte-

flexes or deterioration of respiratory function) rial oxygen saturation >90%)

Hypotension¶ Administer fluids for volume expansion, consider vasopres- Increase mean arterial pressure to >60 mm Hg

sors, and consider monitoring central venous pressure and restore organ perfusion and tissue oxy-

genation

Rhabdomyolysis Expand volume with normal saline and administer intrave- Prevent myoglobin-induced renal injury: pro-

nous furosemide, mannitol, and sodium bicarbonate mote renal blood flow, diuresis, and alkaliza-

tion of urine

Monitor serum potassium and calcium levels and treat hyper- Prevent life-threatening cardiac arrhythmia

kalemia

After cooling Supportive therapy Recovery of organ function

Multiorgan dysfunction

*Data are from Knochel and Reed,1 Graham et al.,80 Wyndham et al.,81 Weiner and Khogali,82 Al-Aska et al.,83 White et al.,84,85 and Bouchama et al.86

†Heat stroke should be suspected in any patient with changes in mental status during heat stress, even if his or her core temperature is <40°C.

‡There is no evidence that one cooling technique is superior to another. Noninvasive techniques that are easy to apply, well tolerated, and not likely to

cause cutaneous vasoconstriction are preferred.

§There is no evidence to support a specific temperature end point at which cooling should be halted. However, a rectal temperature of 39.4°C has been

used in large series and has proved to be safe.86

¶Hypotension usually responds to volume expansion and cooling. Vasodilatory shock and primary myocardial dysfunction may underlie sustained hypo-

tension that is refractory to volume expansion. Therapy should be individualized and guided by the patient’s clinical response.

the flow of blood to the skin.80-85 This is accomplished paring the effects of these various cooling techniques

by increasing the temperature gradient between the on cooling times and outcome in patients with heat

skin and the environment (for cooling by conduction) stroke.

or by increasing the gradient of water-vapor pressure No pharmacologic agents that accelerate cooling

between the skin and the environment (for cooling are helpful in the treatment of heat stroke. Although

by evaporation), as well as by increasing the velocity the use of dantrolene sodium has been considered, this

of air adjacent to the skin (for cooling by convection). agent was found ineffective in a double-blind, random-

In practice, cold water or ice is applied to the skin, ized study.86 The role of antipyretic agents in heat

which is also fanned (Table 4). Most such methods stroke has not been evaluated, despite findings that

lower the skin temperature to below 30°C, trigger- pyrogenic cytokines are implicated in heat stress.

ing cutaneous vasoconstriction and shivering. To over- Recovery of central nervous system function during

come this response, the patient may be vigorously cooling is a favorable prognostic sign and should be

massaged, sprayed with tepid water (40°C), or exposed expected in the majority of patients who receive

to hot moving air (45°C), either at the same time as prompt and aggressive treatment. Residual brain dam-

cooling methods are applied or in an alternating fash- age occurs in about 20 percent of the patients and is

ion.80-83 There have been no controlled studies com- associated with high mortality.1,2

N Engl J Med, Vol. 346, No. 25 · June 20, 2002 · www.nejm.org · 1985

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on November 20, 2003.

Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The Ne w E n g l a nd Jo u r n a l o f Me d ic i ne

sible air-conditioned shelters, and reduce energy costs

TABLE 4. METHODS OF COOLING. during extreme weather so that air conditioning is af-

fordable may decrease morbidity and mortality during

Techniques based on conductive cooling

heat waves.88-90 In football players, modification of

External*

Cold-water immersion practice schedules and avoidance of dehydration and

Application of cold packs or ice slush over part of the body or the whole salt depletion have been found to be effective means

body of preventing heat stroke.91

Use of cooling blankets

Internal†

Iced gastric lavage Emerging Concepts

Iced peritoneal lavage

After the onset of heat stroke, normalizing the

Techniques based on evaporative or convective cooling body temperature may not prevent inflammation,

Fanning the undressed patient at room temperature (20°C to 22°C)

Wetting of the body surface during continuous fanning‡

coagulation, and progression to multiorgan dysfunc-

Use of a body-cooling unit§ tion.2,11,18,20,45,49,53 For this reason, new approaches to

modulation of the inflammatory response are being

*Because external cooling results in cutaneous vasoconstriction, vigo-

rous massaging of the skin is recommended.81,82

studied in animals. Immunomodulators such as in-

†Internal cooling, which has been investigated in animals, is infrequently

terleukin-1–receptor antagonists, antibodies to endo-

used in humans.84,85 Gastric or peritoneal lavage with ice water may cause toxin, and corticosteroids improve survival in animals

water intoxication. but have not yet been studied in humans.10,13,14 It is

‡The skin is covered with a fine gauze sheet that has been soaked in wa- uncertain whether anticytokine and anti-endotoxin

ter at 20°C while the patient is fanned. The fanning is reduced or stopped

if the skin temperature drops to <30°C.83 strategies will be more successful in heat stroke than

§A body-cooling unit is a special bed that sprays atomized water at 15°C they have been in sepsis. New therapeutic interven-

and warm air at 45°C over the whole body surface to keep the temperature tions aimed at limiting the activity of nuclear factor-

of the wet skin between 32°C and 33°C.82 kB, a critical transcription factor in the regulation of

acute inflammation, may prove more successful: in a

model of inflammation-associated injury (mice with

sepsis), inhibition of nuclear factor-kB activity has

been found to improve survival, but it also appears

Prevention to promote apoptosis of hepatocytes.92,93

Heat stroke is a preventable illness, and thorough Coagulation and fibrinolysis are frequently activated

knowledge of the disorder can help to reduce mor- during heat stroke and may lead to disseminated in-

tality and morbidity.1,3 Although classic heat stroke travascular coagulation.20,21 Replacement therapy with

is predominant in very young or elderly persons and in recombinant activated protein C, which attenuates

those who have no access to air conditioning,1-3,25-27 it both the coagulation and the inflammation, reduces

is also relatively common among persons with chron- mortality in patients with severe sepsis and may be

ic mental disorders or cardiopulmonary disease and useful in those with heat stroke as well.20,94 Elucida-

those receiving medications that interfere with salt and tion of the molecular mechanisms that trigger the ac-

water balance, such as diuretics, anticholinergic agents, tivation of coagulation may lead to more specific ther-

and tranquilizers that impair sweating.1-3,25-27 Exertion- apy, such as tissue-factor pathway inhibitors.

al heat stroke may be seen in manual laborers, military More important are potential therapeutic applica-

personnel, football players, long-distance runners, and tions based on knowledge of the stress-response pro-

those who ingest an overdose of cocaine or amphet- teins.15,16 A logical goal for the next generation of

amines.1 To prevent both types of heat stroke, people immunomodulators is selective pharmacologic induc-

can acclimatize themselves to heat, schedule outdoor tion of the expression of heat-shock proteins. Salicylate

activities during cooler times of the day, reduce their and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs activate heat-

level of physical activity, drink additional water, con- shock transcription factors and induce the transcrip-

sume salty foods, and increase the amount of time they tion and translation of heat-shock proteins in mam-

spend in air-conditioned environments.1,3 Automobiles malian cells.57 This response enhances tolerance of heat

should be locked, and children should never be left and cellular protection against heat stress. Although

unattended in an automobile during hot weather. excessive expression of the heat-shock proteins blocks

Despite accumulated knowledge and experience, essential cellular processes, partial up-regulation of

deaths during heat waves are still common88-90 and have these proteins may prove beneficial, particularly as a

been associated largely with social isolation in vulner- preventive measure during a heat wave. Further stud-

able populations, lack of air conditioning, and increas- ies are required to define the degree to which inflam-

es in heat during large gatherings for cultural or re- matory and stress responses can be modulated in hu-

ligious purposes.25-28,88-90 A plan to improve weather mans without interfering with essential immunologic

forecasting, alert those at risk, provide readily acces- mechanisms.

1986 · N Engl J Med, Vol. 346, No. 25 · June 20, 2002 · www.nejm.org

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on November 20, 2003.

Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

MEDICAL PROGRESS

CONCLUSIONS 18. Bouchama A, Hammami MM, Haq A, Jackson J, al-Sedairy S. Evi-

dence for endothelial cell activation/injury in heatstroke. Crit Care Med

The threat of heat stroke is increasing. Global warm- 1996;24:1173-8.

ing is already causing heat waves in temperate cli- 19. Shieh SD, Shiang JC, Lin YF, Shiao WY, Wang JY. Circulating angio-

tensin-converting enzyme, von Willebrand factor antigen and thrombo-

mates.4-8 The recognition that thermoregulatory fail- modulin in exertional heat stroke. Clin Sci (Lond) 1995;89:261-5.

ure and impaired regulation of inflammatory and 20. Bouchama A, Bridey F, Hammami MM, et al. Activation of coagula-

tion and fibrinolysis in heatstroke. Thromb Haemost 1996;76:909-15.

stress responses facilitate the progression from heat 21. al Mashhadani SA, Gader AG, al Harthi SS, Kangav D, Shaheen FA,

stress to heat stroke and contribute to the severity of Bogus F. The coagulopathy of heatstroke: alterations in coagulation and

tissue injury should make research in this direction fibrinolysis in heatstroke patients during the pilgrimage (Haj) to Makkah.

Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 1994;5:731-6.

a priority. Greater knowledge of the cellular and mo- 22. Pedersen BK, Hoffman-Goetz L. Exercise and the immune system:

lecular responses to heat stress will help point to novel regulation, integration, and adaptation. Physiol Rev 2000;80:1055-81.

preventive measures and a new paradigm of immuno- 23. Moseley PL. Heat shock proteins and heat adaptation of the whole

organism. J Appl Physiol 1997;83:1413-7.

modulation. In this way, the multiorgan injury caused 24. Beal AL, Cerra FB. Multiple organ failure syndrome in the 1990s:

by heat stroke might be minimized in many patients. systemic inflammatory response and organ dysfunction. JAMA 1994;271:

226-33.

25. Semenza JC, Rubin CH, Falter KH, et al. Heat-related deaths during

the July 1995 heat wave in Chicago. N Engl J Med 1996;335:84-90.

We are indebted to Yvonne Lock and Vickie Anderson for assist- 26. Jones TS, Liang AP, Kilbourne EM, et al. Morbidity and mortality as-

ance in the preparation of the manuscript. sociated with the July 1980 heat wave in St. Louis and Kansas City, Mo.

JAMA 1982;247:3327-31.

27. Kilbourne EM, Choi K, Jones TS, Thacker SB. Risk factors for heat-

REFERENCES stroke: a case-control study. JAMA 1982;247:3332-6.

28. Ghaznawi HI, Ibrahim MA. Heat stroke and heat exhaustion in pil-

1. Knochel JP, Reed G. Disorders of heat regulation. In: Narins RG, ed. grims performing the Haj (annual pilgrimage) in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi

Maxwell & Kleeman’s clinical disorders of fluid and electrolyte metabolism. Med 1987;7:323-6.

5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994:1549-90. 29. Mackowiak PA, ed. Fever: basic mechanisms and management. 2nd ed.

2. Dematte JE, O’Mara K, Buescher J, et al. Near-fatal heat stroke during Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1997:35-40.

the 1995 heat wave in Chicago. Ann Intern Med 1998;129:173-81. 30. Rowell LB. Cardiovascular aspects of human thermoregulation. Circ

3. Heat-related illnesses, deaths, and risk factors — Cincinnati and Dayton, Res 1983;52:367-79.

Ohio, 1999, and United States, 1979–1997. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly 31. Buono MJ, Sjoholm NT. Effect of physical training on peripheral sweat

Rep 2000;49:470-3. production. J Appl Physiol 1988;65:811-4.

4. Easterling DR , Meehl GA, Parmesan C, Changnon SA, Karl TR , 32. Nelson N, Eichna LW, Horvath SM, Shelley WB, Hatch TF. Thermal

Mearns LO. Climate extremes: observations, modeling, and impacts. Sci- exchanges of man at high temperatures. Am J Physiol 1947;151:626-52.

ence 2000;298:2068-74. 33. Adams WC, Fox RH, Fry AJ, MacDonald IC. Thermoregulation dur-

5. Rooney C, McMichael AJ, Kovats RS, Coleman MP. Excess mortality ing marathon running in cool, moderate, and hot environments. J Appl

in England and Wales, and in Greater London, during the 1995 heatwave. Physiol 1975;38:1030-7.

J Epidemiol Community Health 1998;52:482-6. 34. Deschamps A, Levy RD, Cosio MG, Marliss EB, Magder S. Effect of

6. Sartor F, Snacken R , Demuth C, Walckiers D. Temperature, ambient saline infusion on body temperature and endurance during heavy exercise.

ozone levels, and mortality during summer 1994, in Belgium. Environ Res J Appl Physiol 1989;66:2799-804.

1995;70:105-13. 35. Knochel JP. Catastrophic medical events with exhaustive exercise:

7. Katsouyanni K, Trichopoulos D, Zavitsanos X, Touloumi G. The 1987 “white collar rhabdomyolysis.” Kidney Int 1990;38:709-19.

Athens heatwave. Lancet 1988;2:573. 36. Gabay C, Kushner I. Acute-phase proteins and other systemic respons-

8. Nakai S, Itoh T, Morimoto T. Deaths from heat stroke in Japan: 1968- es to inflammation. N Engl J Med 1999;340:448-54. [Erratum, N Engl J

1994. Int J Biometeorol 1999;43:124-7. Med 1999;340:1376.]

9. Gathiram P, Wells MT, Raidoo D, Brock-Utne JG, Gaffin SL. Portal and 37. Cannon JG, Kluger MJ. Endogenous pyrogen activity in human plas-

systemic plasma lipopolysaccharide concentrations in heat-stressed pri- ma after exercise. Science 1983;220:617-9.

mates. Circ Shock 1988;25:223-30. 38. Espersen GT, Elbaek A, Ernst E, et al. Effect of physical exercise on

10. Gathiram P, Wells MT, Brock-Utne JG, Gaffin SL. Antilipopolysaccha- cytokines and lymphocyte subpopulations in human peripheral blood.

ride improves survival in primates subjected to heat stroke. Circ Shock APMIS 1990;98:395-400.

1987;23:157-64. 39. Robins HI, Kutz M, Wiedemann GJ, et al. Cytokine induction in hu-

11. Bouchama A, Parhar RS, el-Yazigi A, Sheth K, al-Sedairy S. Endotox- mans by 41.8 degrees C whole body hyperthermia. Cancer Lett 1995;97:

emia and release of tumor necrosis factor and interleukin 1 alpha in acute 195-201.

heatstroke. J Appl Physiol 1991;70:2640-4. 40. Camus G, Nys M, Poortmans JR, et al. Endotoxaemia, production of

12. Hall DM, Buettner GR, Oberley LW, Xu L, Matthes RD, Gisolfi CV. tumour necrosis factor alpha and polymorphonuclear neutrophil activation

Mechanisms of circulatory and intestinal barrier dysfunction during whole following strenuous exercise in humans. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol

body hyperthermia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2001;280:H509- 1998;79:62-8.

H521. 41. Ostrowski K, Rohde T, Zacho M, Asp S, Pedersen BK. Evidence that

13. Lin MT, Liu HH, Yang YL. Involvement of interleukin-1 receptor interleukin-6 is produced in human skeletal muscle during prolonged run-

mechanisms in development of arterial hypotension in rat heatstroke. Am ning. J Physiol 1998;508:949-53.

J Physiol 1997;273:H2072-H2077. 42. Moldoveanu AI, Shephard RJ, Shek PN. Exercise elevates plasma levels

14. Liu CC, Chien CH, Lin MT. Glucocorticoids reduce interleukin-1 but not gene expression of IL-1beta, IL-6 and TNF-alpha in blood mono-

concentration and result in neuroprotective effects in rat heatstroke. J Phys- nuclear cells. J Appl Physiol 2000;89:1499-504.

iol 2000;27:333-43. 43. Suzuki K, Yamada M, Kurakake S, et al. Circulating cytokines and hor-

15. Yang YL, Lin MT. Heat shock protein expression protects against cer- mones with immunosuppressive but neutrophil-priming potentials rise af-

ebral ischemia and monoamine overload in rat heatstroke. Am J Physiol ter endurance exercise in humans. Eur J Appl Physiol 2000;81:281-7.

1999;276:H1961-H1967. 44. Chang DM. The role of cytokines in heatstroke. Immunol Invest

16. Li PL, Chao YM, Chan SH, Chan JY. Potentiation of baroreceptor re- 1993;22:553-61.

flex response by heat shock protein 70 in nucleus tractus solitarii confers 45. Bouchama A, al-Sedairy S, Siddiqui S, Shail E, Rezeig M. Elevated py-

cardiovascular protection during heatstroke. Circulation 2001;103:2114- rogenic cytokines in heatstroke. Chest 1993;104:1498-502.

19. 46. Hammami MM, Bouchama A, Shail E, al-Sedairy S. Elevated serum

17. Wang ZZ, Wang CL, Wu TC, Pan HN, Wang SK, Jiang JD. Autoan- level of soluble interleukin-2 receptor in heatstroke. Intensive Care Med

tibody response to heat shock protein 70 in patients with heatstroke. Am 1998;24:988.

J Med 2001;111:654-7. 47. Bouchama A, Hammami MM, Al Shail E, De Vol E. Differential ef-

N Engl J Med, Vol. 346, No. 25 · June 20, 2002 · www.nejm.org · 1987

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on November 20, 2003.

Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The Ne w E n g l a nd Jo u r n a l o f Me d ic i ne

fects of in vitro and in vivo hyperthermia on the production of interleukin- normal tissues induced by whole body hyperthermia in rats. Cancer Res

10. Intensive Care Med 2000;26:1646-51. 1995;55:5459-64.

48. Akimoto T, Akama T, Tatsuno M, Saito M, Kono I. Effect of brief 71. Bynum GD, Pandolf KB, Schuette WH, et al. Induced hyperthermia

maximal exercise on circulating levels of interleukin-12. Eur J Appl Physiol in sedated humans and the concept of critical thermal maximum. Am J

2000;81:510-2. Physiol 1978;235:R228-R236.

49. Hammami MM, Bouchama A, Al-Sedairy S, Shail E, AlOhaly Y, Mo- 72. Lin MT, Kao TY, Su CF, Hsu SS. Interleukin-1 beta production dur-

hamed GE. Concentrations of soluble tumor necrosis factor and interleu- ing the onset of heat stroke in rabbits. Neurosci Lett 1994;174:17-20.

kin-6 receptors in heatstroke and heatstress. Crit Care Med 1997;25:1314- 73. Malamud N, Haymaker W, Custer RP. Heat stroke: a clinico-patholog-

9. ic study of 125 fatal cases. Mil Surg 1946;99:397-449.

50. Viti A, Muscettola M, Paulesu L, Bocci V, Almi A. Effect of exercise 74. Sohal RS, Sun SC, Colcolough HL, Burch GE. Heatstroke: an elec-

on plasma interferon levels. J Appl Physiol 1985;59:426-8. tron microscopic study of endothelial cell damage and disseminated intra-

51. Cannon JG. Inflammatory cytokines in nonpathological states. News vascular coagulation. Arch Intern Med 1968;122:43-7.

Physiol Sci 2000;15:298-303. 75. Chao TC, Sinniah R, Pakiam JE. Acute heat stroke deaths. Pathology

52. Hietala J, Nurmi T, Uhari M, Pakarinen A, Kouvalainen K. Acute 1981;13:145-56.

phase proteins, humoral and cell mediated immunity in environmentally- 76. el-Kassimi FA, Al-Mashhadani S, Abdullah AK, Akhtar J. Adult respi-

induced hyperthermia in man. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1982;49: ratory distress syndrome and disseminated intravascular coagulation com-

271-6. plicating heat stroke. Chest 1986;90:571-4.

53. Hammami MM, Bouchama A, Shail E, Aboul-Enein HY, Al-Sedairy 77. Ang C, Dawes J. The effects of hyperthermia on human endothelial

S. Lymphocyte subsets and adhesion molecules expression in heatstroke monolayers: modulation of thrombotic potential and permeability. Blood

and heat stress. J Apply Physiol 1998;84:1615-21. Coagul Fibrinolysis 1994;5:193-9.

54. Xing Z, Gauldie J, Cox G, et al. IL-6 is an antiinflammatory cytokine 78. Lefor AT, Foster CE III, Sartor W, Engbrecht B, Fabian DF, Silverman

required for controlling local or systemic acute inflammatory responses. D. Hyperthermia increases intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression

J Clin Invest 1998;101:311-20. and lymphocyte adhesion to endothelial cells. Surgery 1994;116:214-21.

55. Kurahashi K, Kajikawa O, Sawa T, et al. Pathogenesis of septic shock 79. Alzeer AH, Al-Arifi A, Warsy AS, Ansari Z, Zhang H, Vincent JL.

in Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. J Clin Invest 1999;104:743-50. Nitric oxide production is enhanced in patients with heat stroke. Intensive

56. Welch WJ. Mammalian stress response: cell physiology, structure/ Care Med 1999;25:58-62.

function of stress proteins, and implications for medicine and disease. Phys- 80. Graham BS, Lichtenstein MJ, Hinson JM, Theil GB. Nonexertional

iol Rev 1992;72:1063-81. heatstroke: physiologic management and cooling in 14 patients. Arch In-

57. Polla BS, Bachelet M, Elia G, Santoro MG. Stress proteins in inflam- tern Med 1986;146:87-90.

mation. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1998;851:75-85. 81. Wyndham CH, Strydom NB, Cooke HM, et al. Methods of cooling

58. Riabowol KT, Mizzen LA, Welch WJ. Heat shock is lethal to fibro- subjects with hyperpyrexia. J Appl Physiol 1959;14:771-6.

blasts microinjected with antibodies against hsp70. Science 1988;242:433- 82. Weiner JS, Khogali M. A physiological body-cooling unit for treat-

6. ment of heat stroke. Lancet 1980;1:507-9.

59. Hall DM, Baumgardner KR, Oberley TD, Gisolfi CV. Splanchnic tis- 83. Al-Aska AK, Abu-Aisha H, Yaqub B, Al-Harthi SS, Sallam A. Simpli-

sues undergo hypoxic stress during whole body hyperthermia. Am J Phys- fied cooling bed for heatstroke. Lancet 1987;1:381.

iol 1999;276:G1195-G1203. 84. White JD, Riccobene E, Nucci R , Johnson C, Butterfield AB, Kamath

60. Shapiro Y, Alkan M, Epstein Y, Newman F, Magazanik A. Increase in R. Evaporation versus iced gastric lavage treatment of heatstroke: compar-

rat intestinal permeability to endotoxin during hyperthermia. Eur J Appl ative efficacy in a canine model. Crit Care Med 1987;15:748-50.

Physiol Occup Physiol 1986;55:410-2. 85. White JD, Kamath R , Nucci R , Johnson C, Shepherd S. Evaporation

61. Pals KL, Chang RT, Ryan AJ, Gisolfi CV. Effect of running intensity versus iced peritoneal lavage treatment of heatstroke: comparative efficacy

on intestinal permeability. J Appl Physiol 1997;82:571-6. in a canine model. Am J Emerg Med 1993;11:1-3.

62. Bosenberg AT, Brock-Utne JG, Gaffin SL, Wells MT, Blake GT. Stren- 86. Bouchama A, Cafege A, Devol EB, Labdi O, el-Assil K, Seraj M. In-

uous exercise causes systemic endotoxemia. J Appl Physiol 1988;65:106-8. effectiveness of dantrolene sodium in the treatment of heatstroke. Crit Care

63. Sakurada S, Hales JR. A role for gastrointestinal endotoxins in en- Med 1991;19:176-80.

hancement of heat tolerance by physical fitness. J Appl Physiol 1998;84: 87. Knochel JP. Pigment nephropathy. In: Greenberg A, Cheung AK, eds.

207-14. Primer on kidney diseases. 2nd ed. San Diego, Calif.: Academic Press,

64. Bouchama A, Hammami MM. Endothelin-1 in heatstroke. J Appl 1998:273-6.

Physiol 1995;79:1391. 88. Changnon SA, Easterling DR. Disaster management: U.S. policies

65. Ryan AJ, Gisolfi CV, Moseley PL. Synthesis of 70K stress protein by pertaining to weather and climate extremes. Science 2000;289:2053-5.

human leukocytes: effect of exercise in the heat. J Appl Physiol 1991;70: 89. Kalkstein LS. Saving lives during extreme weather in summer. BMJ

466-71. 2000;321:650-1.

66. Febbraio MA, Koukoulas I. HSP72 gene expression progressively in- 90. Kellerman AL, Todd KH. Killing heat. N Engl J Med 1996;335:126-7.

creases in human skeletal muscle during prolonged, exhaustive exercise. 91. Knochel JP. Dog days and siriasis: how to kill a football player. JAMA

J Appl Physiol 2000;89:1055-60. 1975;233:513-5.

67. Fehrenbach E, Niess AM, Scholtz E, Passek F, Dickhuth HH, 92. Tak PP, Firestein GS. NF-kB: a key role in inflammatory diseases.

Northoff H. Transcriptional and translational regulation of heat shock J Clin Invest 2001;107:7-11.

proteins in leukocytes of endurance runners. J Appl Physiol 2000;89:704- 93. Bohrer H, Qiu F, Zimmerman T, et al. Role of NF-kB in the mortality

10. of sepsis. J Clin Invest 1997;100:972-85.

68. Milner CM, Campbell RD. Polymorphic analysis of the three MHC- 94. Bernard GR, Vincent J-L, Laterre P-F, et al. Efficacy and safety of re-

linked HSP70 genes. Immunogenetics 1992;36:357-62. combinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N Engl J Med

69. Buckley IK. A light and electron microscopic study of thermally in- 2001;344:699-709.

jured cultured cells. Lab Invest 1972;26:201-9.

70. Sakaguchi Y, Stephens LC, Makino M, et al. Apoptosis in tumors and Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society.

1988 · N Engl J Med, Vol. 346, No. 25 · June 20, 2002 · www.nejm.org

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on November 20, 2003.

Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

View publication stats

You might also like

- Philippine Blood Coordinating Council TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT in Blood Service FacilitiesDocument11 pagesPhilippine Blood Coordinating Council TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT in Blood Service FacilitiesDiane GaliNo ratings yet

- Family Medical History GenoGramDocument1 pageFamily Medical History GenoGramChristine Alvarez100% (1)

- Transport in Humans: Test Yourself 8.1 (Page 140)Document3 pagesTransport in Humans: Test Yourself 8.1 (Page 140)lee100% (3)

- Emergency Manajement and EffectDocument8 pagesEmergency Manajement and EffectTitik ErawatiNo ratings yet

- Heat SrokeDocument8 pagesHeat SrokeChristy BradyNo ratings yet

- Heat Stroke ArticleDocument29 pagesHeat Stroke ArticleIurascu GeaninaNo ratings yet

- Heat Illnes Ped Rev 2019Document13 pagesHeat Illnes Ped Rev 2019Sandra A. Sánchez GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Pathogenesis of Fever: Mohammad M. Sajadi - Philip A. MackowiakDocument7 pagesPathogenesis of Fever: Mohammad M. Sajadi - Philip A. MackowiakRyanNo ratings yet

- Epstein 2011Document7 pagesEpstein 2011lolNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of Heatstroke: I Gede Yasa AsmaraDocument8 pagesDiagnosis and Management of Heatstroke: I Gede Yasa AsmaraputryaNo ratings yet

- HyperthermiaDocument20 pagesHyperthermiaShereen AlobinayNo ratings yet

- The Evaluation and Management of Heat Injuries inDocument5 pagesThe Evaluation and Management of Heat Injuries inDasa HotNo ratings yet

- 4 9 Heat Stroke PDFDocument6 pages4 9 Heat Stroke PDFmia nurjanahNo ratings yet

- Altered Body Temperature: Presented By: Navjeet Kaur M.SC (NSG) 1 YRDocument68 pagesAltered Body Temperature: Presented By: Navjeet Kaur M.SC (NSG) 1 YRNithu NithuNo ratings yet

- Heat Stroke in Dogs Literature ReviewDocument11 pagesHeat Stroke in Dogs Literature ReviewGuillermo MuzasNo ratings yet

- Fever - Pathogenesis, Pathophysiology, and PurposeDocument10 pagesFever - Pathogenesis, Pathophysiology, and PurposeTiago RiosNo ratings yet

- Presented By:: Lisa Chadha M.SC (NSG) 1 YR BvconDocument69 pagesPresented By:: Lisa Chadha M.SC (NSG) 1 YR BvconHardeep KaurNo ratings yet

- 2013-143 Heat StressDocument4 pages2013-143 Heat StressArun PrakashNo ratings yet

- Fever in The Neurointensive Care UnitDocument9 pagesFever in The Neurointensive Care UnitDiayanti TentiNo ratings yet

- Exertional Heatstroke, Asesmen Cepat Dan Penatalaksanaan Tepat: Laporan KasusDocument18 pagesExertional Heatstroke, Asesmen Cepat Dan Penatalaksanaan Tepat: Laporan KasusGreen HanauNo ratings yet

- Group 4 - Bacani - 220000002117Document3 pagesGroup 4 - Bacani - 220000002117Ana Paula Bacani-SacloloNo ratings yet

- 1.TBL 1 - Acute FeverDocument8 pages1.TBL 1 - Acute FeverJeffrey FNo ratings yet

- Exertional Heatstroke, Asesmen Cepat Dan Penatalaksanaan:: Laporan KasusDocument17 pagesExertional Heatstroke, Asesmen Cepat Dan Penatalaksanaan:: Laporan KasusAndhika RcmNo ratings yet

- Inflam 2Document7 pagesInflam 2Abraham TheodoreNo ratings yet

- Heat Stroke: Early Recognition and Cooling TechniquesDocument13 pagesHeat Stroke: Early Recognition and Cooling TechniquesAniNo ratings yet

- Review Mechanism of FeverDocument8 pagesReview Mechanism of FeverYanna RizkiaNo ratings yet

- Historical Perspectives On Medical Care For Heat Stroke, Part 1: Ancient Times Through The Nineteenth CenturyDocument7 pagesHistorical Perspectives On Medical Care For Heat Stroke, Part 1: Ancient Times Through The Nineteenth CenturyAhmad Yar SukheraNo ratings yet

- Fev Mech PDFDocument7 pagesFev Mech PDFMitzu AlparisNo ratings yet

- Chapter 49 Heat InjuriesDocument8 pagesChapter 49 Heat Injuriessmith.kevin1420344No ratings yet

- Heatstroke.4Document7 pagesHeatstroke.4Ester DuwitNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 - Fever: Pathogenesis and Treatment: Normal Body TemperatureDocument5 pagesChapter 5 - Fever: Pathogenesis and Treatment: Normal Body TemperatureGio MirandaNo ratings yet

- E-Therapeutics+ - Minor Ailments - Therapeutics - Central Nervous System Conditions - Heat-Related DisordersDocument7 pagesE-Therapeutics+ - Minor Ailments - Therapeutics - Central Nervous System Conditions - Heat-Related DisordersSamMansuriNo ratings yet

- Fever During AnesthesiaDocument19 pagesFever During AnesthesiaWindy SuryaNo ratings yet

- Term o RegulationDocument10 pagesTerm o Regulationfinna kartikaNo ratings yet

- Treatment and Prevention of Heat-Related Illness1Document10 pagesTreatment and Prevention of Heat-Related Illness1Karyn AlbaNo ratings yet

- Golpe de Calor NEJMDocument11 pagesGolpe de Calor NEJMJair Alexander Quintero PanucoNo ratings yet

- Becker 2010 FeverDocument10 pagesBecker 2010 Fever211097salNo ratings yet

- 20230923-21444-50guzkDocument6 pages20230923-21444-50guzkEster DuwitNo ratings yet

- Enfermedades Relacionadas Al CalorDocument12 pagesEnfermedades Relacionadas Al CalorJennifer Gonzalez NajeraNo ratings yet

- Thermoregulation Disorders of Central Origin - How To Diagnose and TreatDocument8 pagesThermoregulation Disorders of Central Origin - How To Diagnose and TreatCatalina GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Recent Advances in ThermoregulationDocument11 pagesRecent Advances in ThermoregulationlutfianaNo ratings yet

- Fiebre Patofisiologia WordDocument9 pagesFiebre Patofisiologia WordMatt Mathy Chang PariapazaNo ratings yet

- Ch11 HumanPhysiologicalResponsestoColdStressandHypotDocument32 pagesCh11 HumanPhysiologicalResponsestoColdStressandHypotLee SmithNo ratings yet

- Physiology of ThermoregulationDocument18 pagesPhysiology of Thermoregulationsanti sidabalokNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Heat: Climate Change and HealthDocument2 pagesThe Effects of Heat: Climate Change and HealthChantelle De GraciaNo ratings yet

- Fever TransliteDocument23 pagesFever TransliteeenNo ratings yet

- Heat StrokeDocument15 pagesHeat Strokevague_darklordNo ratings yet

- Environmental Emergencies ParamedicDocument90 pagesEnvironmental Emergencies ParamedicPaulhotvw67100% (2)

- FeverDocument5 pagesFeverdonalpampamNo ratings yet

- Stroke and Heat StrokeDocument12 pagesStroke and Heat StrokeAkinsoun MotunrayoNo ratings yet

- Thermal Regulation: Mary Frances D. PateDocument17 pagesThermal Regulation: Mary Frances D. PateWinny Shiru MachiraNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis of Pyrexia of Unknown Origin - in PracticeDocument10 pagesDiagnosis of Pyrexia of Unknown Origin - in PracticeVioletNo ratings yet

- Heat Stroke NejmDocument11 pagesHeat Stroke NejmYovita LimiawanNo ratings yet

- Temperature Regulation and Monitoring-Samar TahaDocument57 pagesTemperature Regulation and Monitoring-Samar TahapaulaNo ratings yet

- Fever of Unknown OriginDocument33 pagesFever of Unknown OriginRanjit Kumar ShahNo ratings yet

- Hyperthermia Case StudyDocument28 pagesHyperthermia Case StudyJanelle GimenezNo ratings yet

- Fever: in Children: ShouldDocument4 pagesFever: in Children: ShouldTran Trang AnhNo ratings yet

- Acut FeverDocument11 pagesAcut FeverAndreas Adrianto HandokoNo ratings yet

- Garispanduan Pengurusan Kes-Kes Yang Berkaitan Dengan Cuaca PanasDocument21 pagesGarispanduan Pengurusan Kes-Kes Yang Berkaitan Dengan Cuaca PanasHong Wei LungNo ratings yet

- Targeted Temperature Management in Brain Injured  Patients PDFDocument23 pagesTargeted Temperature Management in Brain Injured  Patients PDFCamilo Benavides BurbanoNo ratings yet

- The Healing Power of Fever: Your Body's Natural Defense against DiseaseFrom EverandThe Healing Power of Fever: Your Body's Natural Defense against DiseaseNo ratings yet

- The Ice Bath Path To Enhanced Sperm Health And Fertility - Based On The Teachings Of Dr. Andrew Huberman: Ice Baths And Male Reproductive HealthFrom EverandThe Ice Bath Path To Enhanced Sperm Health And Fertility - Based On The Teachings Of Dr. Andrew Huberman: Ice Baths And Male Reproductive HealthNo ratings yet

- Anatomy and Physiology NCSDocument2 pagesAnatomy and Physiology NCSVianah Eve EscobidoNo ratings yet

- FtytytDocument1 pageFtytytVianah Eve EscobidoNo ratings yet

- UuyyuyDocument3 pagesUuyyuyVianah Eve EscobidoNo ratings yet

- Emergency NursingDocument1 pageEmergency NursingVianah Eve EscobidoNo ratings yet

- XFRGFXGDocument1 pageXFRGFXGVianah Eve EscobidoNo ratings yet

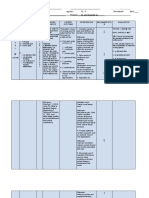

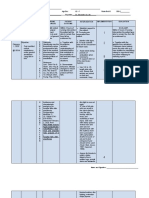

- Date/ Time Cues Need Nursing Diagnosis Patient Outcome Planning of Interventions Imple Ment Ation EvaluationDocument4 pagesDate/ Time Cues Need Nursing Diagnosis Patient Outcome Planning of Interventions Imple Ment Ation EvaluationVianah Eve EscobidoNo ratings yet

- Drug Study Diazepam and ValiumDocument4 pagesDrug Study Diazepam and ValiumVianah Eve EscobidoNo ratings yet

- Simon SaysDocument1 pageSimon SaysVianah Eve EscobidoNo ratings yet

- Acute PainDocument9 pagesAcute PainVianah Eve EscobidoNo ratings yet

- Anti MalarialDocument6 pagesAnti MalariallablikwenNo ratings yet

- Impaired Skin IntegrityDocument4 pagesImpaired Skin IntegrityVianah Eve EscobidoNo ratings yet

- Risk For InfectionDocument5 pagesRisk For InfectionVianah Eve EscobidoNo ratings yet

- Breast Mass Patient Nursing InterventionsDocument8 pagesBreast Mass Patient Nursing InterventionsVianah Eve EscobidoNo ratings yet

- Readiness For Enhance CopingDocument6 pagesReadiness For Enhance CopingVianah Eve EscobidoNo ratings yet

- Impaired Physical MobilityDocument7 pagesImpaired Physical MobilityVianah Eve EscobidoNo ratings yet

- Ineffective Tissue Perfusion - NCPDocument7 pagesIneffective Tissue Perfusion - NCPVianah Eve EscobidoNo ratings yet

- Ineffective Tissue Perfusion - NCPDocument7 pagesIneffective Tissue Perfusion - NCPVianah Eve EscobidoNo ratings yet

- Cervical Cancer - Second-Most Common Cancer Among Women - BusinessMirrorDocument4 pagesCervical Cancer - Second-Most Common Cancer Among Women - BusinessMirrorVianah Eve EscobidoNo ratings yet

- Cervical Cancer - Second-Most Common Cancer Among Women - BusinessMirrorDocument4 pagesCervical Cancer - Second-Most Common Cancer Among Women - BusinessMirrorVianah Eve EscobidoNo ratings yet

- Letters Bsn2i ObgyneDocument4 pagesLetters Bsn2i ObgyneVianah Eve EscobidoNo ratings yet

- Antihpn 2Document23 pagesAntihpn 2Vianah Eve EscobidoNo ratings yet

- Biography ST Therese of Lisieux - Biography OnlineDocument3 pagesBiography ST Therese of Lisieux - Biography OnlineVianah Eve EscobidoNo ratings yet

- Apostle Peter Biography - Timeline, Life, and DeathDocument16 pagesApostle Peter Biography - Timeline, Life, and DeathVianah Eve EscobidoNo ratings yet

- Final Research Proposal 2017 FullDocument52 pagesFinal Research Proposal 2017 FullVianah Eve EscobidoNo ratings yet

- Pregnancy Loss Can Lead To Posttraumatic StressDocument2 pagesPregnancy Loss Can Lead To Posttraumatic StressVianah Eve EscobidoNo ratings yet

- Final Research Proposal 2017Document39 pagesFinal Research Proposal 2017Vianah Eve EscobidoNo ratings yet

- Short StoryDocument6 pagesShort StoryVianah Eve EscobidoNo ratings yet

- Timeline of The Life of St. Dominic - Dominican Friars Province of St. JosephDocument10 pagesTimeline of The Life of St. Dominic - Dominican Friars Province of St. JosephVianah Eve EscobidoNo ratings yet

- Paper Transcription & Translation: Proteins: MlelrlvqgsllkkvleairDocument5 pagesPaper Transcription & Translation: Proteins: MlelrlvqgsllkkvleairXimena QuenguanNo ratings yet

- HEMOLYTIC DISEASE OF THE NEWBORN - Docx PrintDocument6 pagesHEMOLYTIC DISEASE OF THE NEWBORN - Docx PrintJudy HandlyNo ratings yet

- MeaslesDocument14 pagesMeaslesCHALIE MEQUNo ratings yet

- M.F.SC & PHD Programs in - Syllabus: Fish BiotechnologyDocument24 pagesM.F.SC & PHD Programs in - Syllabus: Fish BiotechnologyRinku AroraNo ratings yet

- Bacterial spectrum and antibiotic sensitivity patterns in bile culturesDocument127 pagesBacterial spectrum and antibiotic sensitivity patterns in bile culturesChawki MokademNo ratings yet

- DR Sangeeta T. Amladi: Professor of Dermatology G.S.M.C.& K.E.M. H, Parel, MumbaiDocument24 pagesDR Sangeeta T. Amladi: Professor of Dermatology G.S.M.C.& K.E.M. H, Parel, MumbaidoeneckeNo ratings yet

- TETANUSDocument41 pagesTETANUSruchikakaushal1910No ratings yet

- Histology SlidesDocument47 pagesHistology SlidesHaJoRaNo ratings yet

- Acute Erythroid Leukemia: Review ArticleDocument10 pagesAcute Erythroid Leukemia: Review Articlemita potabugaNo ratings yet

- Skema Modul Skor A+ Bab 5Document8 pagesSkema Modul Skor A+ Bab 5Siti MuslihahNo ratings yet

- Quality Assurance of Selective Culture Media. Método Ecometrico Mossel Et Al 1983Document15 pagesQuality Assurance of Selective Culture Media. Método Ecometrico Mossel Et Al 1983catabacteymicrobioloNo ratings yet

- Emergencia Del Virus Ebola en El Zaire y GuineaDocument8 pagesEmergencia Del Virus Ebola en El Zaire y GuineaColombiologo CaquetensisNo ratings yet

- Anti-MUM1 Antibody Ab104803: 1 Abreviews 2 ImagesDocument3 pagesAnti-MUM1 Antibody Ab104803: 1 Abreviews 2 Imageshorace35No ratings yet

- Activity No. 5 - I Scream For Ice CreamDocument5 pagesActivity No. 5 - I Scream For Ice CreamReynalyn AbaoNo ratings yet

- Whooping CoughDocument22 pagesWhooping CoughAqeel AhmadNo ratings yet

- AP Biology Unit 6 Student NotesDocument57 pagesAP Biology Unit 6 Student Notesmohammadi2No ratings yet

- Case Report: Rapport de CasDocument3 pagesCase Report: Rapport de CasfadillahidsyamNo ratings yet

- Antibacterial Activity of Medicinal Plants Against ESKAPE An Up - 2021 - HeliyoDocument12 pagesAntibacterial Activity of Medicinal Plants Against ESKAPE An Up - 2021 - HeliyoTONY VILCHEZ YARIHUAMANNo ratings yet

- Microbes Worksheet GuideDocument11 pagesMicrobes Worksheet GuideAsma MerchantNo ratings yet

- Notice: Agency Information Collection Activities Proposals, Submissions, and ApprovalsDocument2 pagesNotice: Agency Information Collection Activities Proposals, Submissions, and ApprovalsJustia.comNo ratings yet

- Description of Prototype Modes-of-Action Related To Repeated Dose ToxicityDocument49 pagesDescription of Prototype Modes-of-Action Related To Repeated Dose ToxicityRoy MarechaNo ratings yet

- Hematology I Intensive Rationale - Louise MDocument20 pagesHematology I Intensive Rationale - Louise MKai YoungNo ratings yet

- Core CH 27 Molecular GeneticsDocument6 pagesCore CH 27 Molecular GeneticsTSZ YAN CHEUNGNo ratings yet

- Concept of Gene and Protein SynthesisDocument39 pagesConcept of Gene and Protein SynthesisTabada NickyNo ratings yet

- Antibiotic Use in Food Animals Worldwide, With A Focus On Africa - Pluses and MinusesDocument8 pagesAntibiotic Use in Food Animals Worldwide, With A Focus On Africa - Pluses and MinusesxubicctNo ratings yet

- Jason Call's Letter To ParentsDocument2 pagesJason Call's Letter To Parentsaingram@morningjournalNo ratings yet

- 1.3 - Defense MechanismsDocument7 pages1.3 - Defense MechanismsJEMIMA RUTH MARANo ratings yet

- Understanding MicroorganismsDocument6 pagesUnderstanding MicroorganismsDanica CervantesNo ratings yet