Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Germanic Languages in Europe

Uploaded by

Maximos Maniatis0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

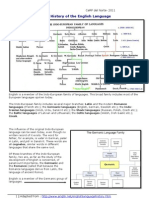

16 views3 pagesThis document discusses the classification and history of the German language. It begins by classifying German as a West Germanic language and describing the branches of the Germanic language family. It then discusses the development of standard German from High German dialects and its relationship to other Germanic languages. The history section describes the Old High German, Middle High German, and early modern German periods, noting important linguistic changes and early texts in each period. Key events included the High German consonant shift, expansion of German territories, and increasing standardization of written German.

Original Description:

Original Title

German Language

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document discusses the classification and history of the German language. It begins by classifying German as a West Germanic language and describing the branches of the Germanic language family. It then discusses the development of standard German from High German dialects and its relationship to other Germanic languages. The history section describes the Old High German, Middle High German, and early modern German periods, noting important linguistic changes and early texts in each period. Key events included the High German consonant shift, expansion of German territories, and increasing standardization of written German.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

16 views3 pagesThe Germanic Languages in Europe

Uploaded by

Maximos ManiatisThis document discusses the classification and history of the German language. It begins by classifying German as a West Germanic language and describing the branches of the Germanic language family. It then discusses the development of standard German from High German dialects and its relationship to other Germanic languages. The history section describes the Old High German, Middle High German, and early modern German periods, noting important linguistic changes and early texts in each period. Key events included the High German consonant shift, expansion of German territories, and increasing standardization of written German.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

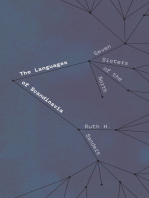

Classification[edit]

The Germanic languages in Europe

Modern Standard German is a West Germanic language in the Germanic branch of the Indo-

European languages. The Germanic languages are traditionally subdivided into three

branches, North Germanic, East Germanic, and West Germanic. The first of these branches

survives in modern Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Faroese, and Icelandic, all of which are descended

from Old Norse. The East Germanic languages are now extinct, and Gothic is the only language in

this branch which survives in written texts. The West Germanic languages, however, have

undergone extensive dialectal subdivision and are now represented in modern languages such as

English, German, Dutch, Yiddish, Afrikaans, and others.[6]

Within the West Germanic language dialect continuum, the Benrath and Uerdingen lines (running

through Düsseldorf-Benrath and Krefeld-Uerdingen, respectively) serve to distinguish the Germanic

dialects that were affected by the High German consonant shift (south of Benrath) from those that

were not (north of Uerdingen). The various regional dialects spoken south of these lines are grouped

as High German dialects, while those spoken to the north comprise the Low German/Low Saxon

and Low Franconian dialects. As members of the West Germanic language family, High German,

Low German, and Low Franconian have been proposed to be further distinguished historically

as Irminonic, Ingvaeonic, and Istvaeonic, respectively. This classification indicates their historical

descent from dialects spoken by the Irminones (also known as the Elbe group), Ingvaeones (or

North Sea Germanic group), and Istvaeones (or Weser-Rhine group).[6]

Standard German is based on a combination of Thuringian-Upper Saxon and Upper Franconian

dialects, which are Central German and Upper German dialects belonging to the High

German dialect group. German is therefore closely related to the other languages based on High

German dialects, such as Luxembourgish (based on Central Franconian dialects) and Yiddish. Also

closely related to Standard German are the Upper German dialects spoken in the southern German-

speaking countries, such as Swiss German (Alemannic dialects) and the various Germanic dialects

spoken in the French region of Grand Est, such as Alsatian (mainly Alemannic, but also Central-

and Upper Franconian dialects) and Lorraine Franconian (Central Franconian).

After these High German dialects, standard German is less closely related to languages based on

Low Franconian dialects (e.g. Dutch and Afrikaans), Low German or Low Saxon dialects (spoken in

northern Germany and southern Denmark), neither of which underwent the High German consonant

shift. As has been noted, the former of these dialect types is Istvaeonic and the latter Ingvaeonic,

whereas the High German dialects are all Irminonic; the differences between these languages and

standard German are therefore considerable. Also related to German are the Frisian languages—

North Frisian (spoken in Nordfriesland), Saterland Frisian (spoken in Saterland), and West

Frisian (spoken in Friesland)—as well as the Anglic languages of English and Scots. These Anglo-

Frisian dialects did not take part in the High German consonant shift.

History[edit]

Main article: History of German

Old High German[edit]

Main article: Old High German

The history of the German language begins with the High German consonant shift during

the migration period, which separated Old High German dialects from Old Saxon. This sound

shift involved a drastic change in the pronunciation of both voiced and voiceless stop

consonants (b, d, g, and p, t, k, respectively). The primary effects of the shift were the following

below.

Voiceless stops became long (geminated) voiceless fricatives following a vowel;

Voiceless stops became affricates in word-initial position, or following certain

consonants;

Voiced stops became voiceless in certain phonetic settings.[7]

Voiceless stop

Word-initial

following a Voiced stop

voiceless stop

vowel

/p/→/ff/ /p/→/pf/ /b/→/p/

/t/→/ss/ /t/→/ts/ /d/→/t/

/k/→/xx/ /k/→/kx/ /g/→/k/

While there is written evidence of the Old High German language in several Elder

Futhark inscriptions from as early as the sixth century AD (such as the Pforzen buckle), the Old High

German period is generally seen as beginning with the Abrogans (written c. 765–775), a Latin-

German glossary supplying over 3,000 Old High German words with their Latin equivalents. After

the Abrogans, the first coherent works written in Old High German appear in the ninth century, chief

among them being the Muspilli, the Merseburg Charms, and the Hildebrandslied, and other religious

texts (the Georgslied, the Ludwigslied, the Evangelienbuch, and translated hymns and prayers).[7]

[8]

The Muspilli is a Christian poem written in a Bavarian dialect offering an account of the soul after

the Last Judgment, and the Merseburg Charms are transcriptions of spells and charms from

the pagan Germanic tradition. Of particular interest to scholars, however, has been

the Hildebrandslied, a secular epic poem telling the tale of an estranged father and son unknowingly

meeting each other in battle. Linguistically this text is highly interesting due to the mixed use of Old

Saxon and Old High German dialects in its composition. The written works of this period stem mainly

from the Alamanni, Bavarian, and Thuringian groups, all belonging to the Elbe Germanic group

(Irminones), which had settled in what is now southern-central Germany and Austria between the

second and sixth centuries during the great migration.[7]

In general, the surviving texts of OHG show a wide range of dialectal diversity with very little written

uniformity. The early written tradition of OHG survived mostly through monasteries and scriptoria as

local translations of Latin originals; as a result, the surviving texts are written in highly disparate

regional dialects and exhibit significant Latin influence, particularly in vocabulary.[7] At this point

monasteries, where most written works were produced, were dominated by Latin, and German saw

only occasional use in official and ecclesiastical writing.

The German language through the OHG period was still predominantly a spoken language, with a

wide range of dialects and a much more extensive oral tradition than a written one. Having just

emerged from the High German consonant shift, OHG was also a relatively new and volatile

language still undergoing a number of phonetic, phonological, morphological, and syntactic changes.

The scarcity of written work, instability of the language, and widespread illiteracy of the time explain

the lack of standardization up to the end of the OHG period in 1050.

Middle High German[edit]

Main article: Middle High German

While there is no complete agreement over the dates of the Middle High German (MHG) period, it is

generally seen as lasting from 1050 to 1350.[9] This was a period of significant expansion of the

geographical territory occupied by Germanic tribes, and consequently of the number of German

speakers. Whereas during the Old High German period the Germanic tribes extended only as far

east as the Elbe and Saale rivers, the MHG period saw a number of these tribes expanding beyond

this eastern boundary into Slavic territory (known as the Ostsiedlung). With the increasing wealth

and geographic spread of the Germanic groups came greater use of German in the courts of nobles

as the standard language of official proceedings and literature.[9] A clear example of this is

the mittelhochdeutsche Dichtersprache employed in the Hohenstaufen court in Swabia as a

standardized supra-dialectal written language. While these efforts were still regionally bound,

German began to be used in place of Latin for certain official purposes, leading to a greater need for

regularity in written conventions.

While the major changes of the MHG period were socio-cultural, German was still undergoing

significant linguistic changes in syntax, phonetics, and morphology as well (e.g. diphthongization of

certain vowel sounds: hus (OHG "house")→haus (MHG), and weakening of unstressed short vowels

to schwa [ə]: taga (OHG "days")→tage (MHG)).[10]

A great wealth of texts survives from the MHG period. Significantly, these texts include a number of

impressive secular works, such as the Nibelungenlied, an epic poem telling the story of the dragon-

slayer Siegfried (c. thirteenth century), and the Iwein, an Arthurian verse poem by Hartmann von

Aue (c. 1203), lyric poems, and courtly romances such as Parzival and Tristan. Also noteworthy is

the Sachsenspiegel, the first book of laws written in Middle Low German (c. 1220). The abundance

and especially the secular character of the literature of the MHG period demonstrate the beginnings

of a standardized written form of German, as well as the desire of poets and authors to be

understood by individuals on supra-dialectal terms.

The Middle High German period is generally seen as ending when the 1346–53 Black

Death decimated Europe's population.[11]

You might also like

- Pennsylvania Dutch: A Dialect of South German With an Infusion of EnglishFrom EverandPennsylvania Dutch: A Dialect of South German With an Infusion of EnglishNo ratings yet

- Outline of the history of the English language and literatureFrom EverandOutline of the history of the English language and literatureNo ratings yet

- Classification: Germanic LanguagesDocument3 pagesClassification: Germanic LanguagesMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- XXXXXXXXXX 4444444444Document10 pagesXXXXXXXXXX 4444444444kiszkaNo ratings yet

- The Origins and History of the German LanguageDocument25 pagesThe Origins and History of the German LanguageGirish NarayananNo ratings yet

- German Language History in the 1911 Encyclopædia BritannicaDocument14 pagesGerman Language History in the 1911 Encyclopædia BritannicaFlavio FerreiraNo ratings yet

- German Dialect RegionsDocument5 pagesGerman Dialect RegionsRoibu Andrei ClaudiuNo ratings yet

- Germanic LanguagesDocument7 pagesGermanic LanguagesCaca LioniesaNo ratings yet

- History of German - Wikipedia 2020Document4 pagesHistory of German - Wikipedia 2020krenari68No ratings yet

- Overview of the German language and its history and classificationDocument2 pagesOverview of the German language and its history and classificationDivyam ChawdaNo ratings yet

- Modern Standard German Language OriginsDocument1 pageModern Standard German Language OriginsblodessimeNo ratings yet

- Early New High German: OstsiedlungDocument4 pagesEarly New High German: OstsiedlungblodessimeNo ratings yet

- Early New High German: OstsiedlungDocument4 pagesEarly New High German: OstsiedlungblodessimeNo ratings yet

- 2 История Англ.яз.Document46 pages2 История Англ.яз.Дарья БелоножкинаNo ratings yet

- Germanic Languages: Old English and its RelativesDocument82 pagesGermanic Languages: Old English and its RelativesRandy GasalaoNo ratings yet

- XXXXXXXXXX 444444444Document40 pagesXXXXXXXXXX 444444444kiszkaNo ratings yet

- Presenting German Culture in EnglishDocument4 pagesPresenting German Culture in Englishanon_875667918No ratings yet

- Early New High German: Nibelungenlied Iwein Parzival Tristan SachsenspiegelDocument4 pagesEarly New High German: Nibelungenlied Iwein Parzival Tristan SachsenspiegelblodessimeNo ratings yet

- Variation in German by S BarbourDocument8 pagesVariation in German by S BarbourNandini1008No ratings yet

- Dutch LanguageDocument25 pagesDutch LanguageAndrei ZvoNo ratings yet

- The Old Frankish LanguageDocument7 pagesThe Old Frankish Languagemorenojuanky3671No ratings yet

- German LanguageDocument41 pagesGerman Languagecristina7dunaNo ratings yet

- PG (AutoRecovered)Document14 pagesPG (AutoRecovered)anaNo ratings yet

- Dutch LanguageDocument26 pagesDutch LanguageFederico Damonte100% (1)

- English 2Document2 pagesEnglish 2EINSTEINNo ratings yet

- German Is Tic ReportDocument21 pagesGerman Is Tic ReportVeronica GrosuNo ratings yet

- Luther's Bible Helped Establish Modern GermanDocument4 pagesLuther's Bible Helped Establish Modern GermanblodessimeNo ratings yet

- Variation in German by S BarbourDocument8 pagesVariation in German by S BarbourNandini1008No ratings yet

- A History of The English Language-1Document63 pagesA History of The English Language-1Valentin Alexandru100% (2)

- Early New High German: Main ArticleDocument3 pagesEarly New High German: Main ArticleblodessimeNo ratings yet

- Low Franconian LanguagesDocument7 pagesLow Franconian Languagesmorenojuanky3671No ratings yet

- English LanguageDocument5 pagesEnglish LanguagemarkNo ratings yet

- West Germanic Languages PDFDocument6 pagesWest Germanic Languages PDFNico RobertNo ratings yet

- Theme 4. A Brief History of The Germanic TribesDocument3 pagesTheme 4. A Brief History of The Germanic TribesМарьяна ГарагедянNo ratings yet

- Foundations of Germanic Philology Final ExamDocument18 pagesFoundations of Germanic Philology Final ExamGiorgiNo ratings yet

- Modern Germanic Languages and Their Distribution in Various Parts of The WorldDocument6 pagesModern Germanic Languages and Their Distribution in Various Parts of The WorldДаша ФісунNo ratings yet

- H. of English Sum UpDocument5 pagesH. of English Sum UpLeonardo QuecoNo ratings yet

- Languages of EuropeDocument37 pagesLanguages of EuropeHasan JamiNo ratings yet

- Why is German Language Known as Pluricentric Language-.DocxDocument2 pagesWhy is German Language Known as Pluricentric Language-.Docxtrax.rahmanNo ratings yet

- Old High German: Old High German (OHG, German: Althochdeutsch, German Abbr. Ahd.) Is The Earliest Stage ofDocument10 pagesOld High German: Old High German (OHG, German: Althochdeutsch, German Abbr. Ahd.) Is The Earliest Stage ofBattuguldur BatuNo ratings yet

- Basics of The Germanic Philology FInal ExamDocument7 pagesBasics of The Germanic Philology FInal Examiamnotcat 00No ratings yet

- Old Dutch Origins and EvolutionDocument12 pagesOld Dutch Origins and Evolutionmorenojuanky3671No ratings yet

- методичка по історії мовиDocument158 pagesметодичка по історії мовиІрина МиськівNo ratings yet

- Classification: Anglic LanguagesDocument5 pagesClassification: Anglic Languagesnina.khechikashviliNo ratings yet

- ДокументDocument1 pageДокументБота ТурлыбековаNo ratings yet

- Phases of The English Language Development-TASKDocument8 pagesPhases of The English Language Development-TASKDercio Mainato100% (1)

- Hogg 1992 The Cambridge History of The English Language VOL 1 (Przeciągnięte)Document41 pagesHogg 1992 The Cambridge History of The English Language VOL 1 (Przeciągnięte)Julia JabłońskaNo ratings yet

- Regional Dialects Printing Press Luther's Vernacular Translation of The Bible Chancery Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I Electorate of Saxony Duchy of Saxe-WittenbergDocument3 pagesRegional Dialects Printing Press Luther's Vernacular Translation of The Bible Chancery Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I Electorate of Saxony Duchy of Saxe-WittenbergblodessimeNo ratings yet

- Course Paper ThemeDocument25 pagesCourse Paper Themewolfolf0909No ratings yet

- Classification: English Is ADocument5 pagesClassification: English Is Anina.khechikashviliNo ratings yet

- A Brief History of the English LanguageDocument2 pagesA Brief History of the English LanguageDiego Castro FameaNo ratings yet

- Old Norse Language HistoryDocument3 pagesOld Norse Language HistoryAbo TalebNo ratings yet

- Comparison Between Old High German and Old EnglishDocument19 pagesComparison Between Old High German and Old EnglishJorge Godah100% (1)

- Old English Seminar 1 1. The Origin and Position of EnglishDocument5 pagesOld English Seminar 1 1. The Origin and Position of EnglishElenaNo ratings yet

- The Germanic Group 1Document29 pagesThe Germanic Group 1Misttica TiendaNo ratings yet

- The Germanic Languages: Origins and Early Dialectal InterrelationsFrom EverandThe Germanic Languages: Origins and Early Dialectal InterrelationsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (3)

- LuxembourgDocument16 pagesLuxembourgMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- LuxembourgDocument16 pagesLuxembourgMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- Nickelback Song Review - "How You Remind MeDocument1 pageNickelback Song Review - "How You Remind MeMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- ViennDocument15 pagesViennMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- AustriaDocument15 pagesAustriaMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- College Students Save Money Through Cooking, Shared Housing & Free ActivitiesDocument1 pageCollege Students Save Money Through Cooking, Shared Housing & Free ActivitiesMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- Place ReviewDocument1 pagePlace ReviewMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- Until He Got Into The CarDocument3 pagesUntil He Got Into The CarMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- Morbid AttachmentDocument707 pagesMorbid AttachmentMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- UnfortunatelyDocument3 pagesUnfortunatelyMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- The CarrotDocument5 pagesThe CarrotMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- Morbid AttachmentDocument4 pagesMorbid AttachmentMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- ReportDocument1 pageReportMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- Qi Boyan Had A Special Decoration On His BodyDocument4 pagesQi Boyan Had A Special Decoration On His BodyMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- A LeafDocument4 pagesA LeafMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- Carrot Cultivars Can Be Grouped Into Two Broad ClassesDocument7 pagesCarrot Cultivars Can Be Grouped Into Two Broad ClassesMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- The Sound of HorsesDocument3 pagesThe Sound of HorsesMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- Leaves Can Also Store Food and WaterDocument5 pagesLeaves Can Also Store Food and WaterMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- Gulf of PariaDocument6 pagesGulf of PariaMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- VeinsDocument5 pagesVeinsMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- People's National MovementDocument10 pagesPeople's National MovementMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- Nicki MinajDocument4 pagesNicki MinajMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- Saint James, Trinidad and TobagoDocument5 pagesSaint James, Trinidad and TobagoMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- Charli XCXDocument4 pagesCharli XCXMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- Madonna: Queen of PopDocument5 pagesMadonna: Queen of PopMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- Christina AguileraDocument3 pagesChristina AguileraMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- Port of SpainDocument8 pagesPort of SpainMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- Twenty One PilotsDocument4 pagesTwenty One PilotsMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- Enjoy the hottest season with summer activitiesDocument7 pagesEnjoy the hottest season with summer activitiesMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- Kanye WestDocument5 pagesKanye WestMaximos ManiatisNo ratings yet

- Old English Vs Modern GermanDocument12 pagesOld English Vs Modern GermanfonsecapeNo ratings yet

- Modul Translation 1Document16 pagesModul Translation 1alfianNo ratings yet

- Learn To Speak German PDFDocument3 pagesLearn To Speak German PDFVilmosné SzternácsikNo ratings yet

- The German Language: Historical DictionariesDocument9 pagesThe German Language: Historical DictionariesVinay RaoNo ratings yet

- Prefixes & Sufixes Dictionary PDFDocument62 pagesPrefixes & Sufixes Dictionary PDFKamalaNo ratings yet

- Farsi Dictionary PDFDocument2 pagesFarsi Dictionary PDFStephanie0% (2)

- Compendious German GrammarDocument504 pagesCompendious German Grammarpomegranate246100% (2)

- 7 Facts About in German 12Document2 pages7 Facts About in German 12art123artNo ratings yet

- Din en 309-2005Document6 pagesDin en 309-2005engenhariadesoldagemNo ratings yet

- Complete Grammar of German by WormanDocument598 pagesComplete Grammar of German by WormanAyan AcademyNo ratings yet

- SurnamesDocument6 pagesSurnamesPraveen ChowdharyNo ratings yet

- A Performance Guide To Select A Cappella Works of Jean Sibelius I PDFDocument150 pagesA Performance Guide To Select A Cappella Works of Jean Sibelius I PDFAlexandraNo ratings yet

- Latvian Grammar 2021Document561 pagesLatvian Grammar 2021Alef Bet100% (2)

- Sergey Mezenin Life of Language A History of EnglishDocument123 pagesSergey Mezenin Life of Language A History of EnglishraqgasparNo ratings yet

- Comparison of English, German and Czech Animal IdiomsDocument52 pagesComparison of English, German and Czech Animal IdiomsAS ASNo ratings yet

- The World of The English LanguageDocument92 pagesThe World of The English LanguageInsaf AliNo ratings yet

- Earworm's Rapid GermanDocument20 pagesEarworm's Rapid GermanSo Ma YYeh Krm100% (5)

- History of Loan Words in English SourcesDocument6 pagesHistory of Loan Words in English SourcesGlennette AlmoraNo ratings yet

- LidijaDocument1 pageLidijamilance93100% (2)

- Cu31924021601962 DjvuDocument164 pagesCu31924021601962 Djvugaud28No ratings yet

- GermanDocument202 pagesGermanAnouar Kacem100% (5)

- Old EnglishDocument3 pagesOld EnglishAbtahee HazzazNo ratings yet

- Resources for German language learningDocument4 pagesResources for German language learningGuang Chen0% (1)

- Ich Komme Von Zu Hause.Document5 pagesIch Komme Von Zu Hause.Muhammad TahirNo ratings yet

- Nations and Nationalities Activities Promoting Classroom Dynamics Group Form - 43962Document2 pagesNations and Nationalities Activities Promoting Classroom Dynamics Group Form - 43962Dražen Glavendekić Viktorija GrgasNo ratings yet

- The Lovers TongueDocument238 pagesThe Lovers TongueRazvan100% (2)

- Multilingual DictionariesDocument82 pagesMultilingual DictionariesScheherezade SuriàNo ratings yet

- German Separable Verbs: When Grammar Splits Your VerbsDocument20 pagesGerman Separable Verbs: When Grammar Splits Your VerbsUbovic Milos100% (4)

- German Through PicturesDocument273 pagesGerman Through Picturesjose messias moraes100% (2)

- BGK 3012 Week 3 - How To Recognize Gender in German LanguageDocument3 pagesBGK 3012 Week 3 - How To Recognize Gender in German LanguageWanie AmeeraNo ratings yet